Abstract

Human genetics and preclinical studies have identified key contributions of TREM2 to several neurodegenerative conditions, inspiring efforts to modulate TREM2 therapeutically. Here, we characterize the activities of three TREM2 agonist antibodies in multiple mixed-sex mouse models of Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology and remyelination. Receptor activation and downstream signaling are explored in vitro, and active dose ranges are determined in vivo based on pharmacodynamic responses from microglia. For mice bearing amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology (PS2APP) or combined Aβ and tau pathology (TauPS2APP), chronic TREM2 agonist antibody treatment had limited impact on microglia engagement with pathology, overall pathology burden, or downstream neuronal damage. For mice with demyelinating injuries triggered acutely with lysolecithin, TREM2 agonist antibodies unexpectedly disrupted injury resolution. Likewise, TREM2 agonist antibodies limited myelin recovery for mice experiencing chronic demyelination from cuprizone. We highlight the contributions of dose timing and frequency across models. These results introduce important considerations for future TREM2-targeting approaches.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, antibody, microglia, multiple sclerosis, myelin repair, TREM2

Significance Statement

Multiple TREM2 agonist antibodies are investigated in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease and multiple sclerosis. Despite agonism in culture models and after acute dosing in mice, antibodies do not show benefit in overall AD pathology and worsen recovery after demyelination.

Introduction

A breadth of studies encompassing human genetics, microglia cell biology, and preclinical disease models have identified a major role for TREM2 in several neurodegenerative diseases. TREM2 variants such as TREM2R47H can lead to early-onset neurodegeneration (Nasu–Hakola disease) in homozygous carriers or greatly elevate the risk of late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD) in heterozygous carriers (Bohlen et al., 2019; Deczkowska et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2022). TREM2 is expressed by a subset of myeloid cells including microglia, the predominant tissue-resident macrophages of the brain (Bohlen et al., 2019; Andrews et al., 2023). Other genetic variants influencing the risk of Alzheimer's disease also show enriched expression by microglia relative to other brain cells, reinforcing the importance of myeloid cells in these diseases (Bohlen et al., 2019). In preclinical models of AD, Trem2 deletion greatly exacerbates pathology accumulation and neurodegeneration in mice bearing amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology (Wang et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2016; Ulland et al., 2017; Meilandt et al., 2020) or combined Aβ and tau pathology (Leyns et al., 2019; Delizannis et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021), with mixed effects reported in tau-only models (Bemiller et al., 2017; Leyns et al., 2017; Sayed et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2021; Vautheny et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022; Lee-Gosselin et al., 2023). Additionally, Trem2 knock-out delays debris clearance and recovery after demyelinating injuries, suggesting contributions to multiple sclerosis (Cantoni et al., 2015; Cignarella et al., 2020; Gouna et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). Thus, augmentation of TREM2 signaling is of interest for multiple neurodegenerative indications.

TREM2 is a surface transmembrane protein that binds to Aβ (Lessard et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2018) or lipid-rich ligands (Atagi et al., 2015; Bailey et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Yeh et al., 2016) and signals in complex with DAP12 and DAP10 (Bouchon et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2022). DAP12 recruits and facilitates phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase SYK (Peng et al., 2010), whereas DAP10 recruits PI3K and Grb2 complexes (Lanier, 2009). Similar to TREM2, variants in the gene encoding DAP12 cause Nasu–Hakola disease (Paloneva et al., 2002). TREM2 or DAP12 loss of function is associated with cellular deficiencies in trophic signaling (Otero et al., 2009), metabolism (Ulland et al., 2017), lipid degradation (Nugent et al., 2020), phagocytosis (Kleinberger et al., 2014), and chemotaxis (Mazaheri et al., 2017). In net, the combination of these altered functions undermines microglial attenuation of disease risk and progression (Bohlen et al., 2019; Deczkowska et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2022).

Given the impact of TREM2 loss of function variants in AD, Nasu–Hakola disease, and diverse disease models, several groups have explored overexpression, stabilization, or agonism of TREM2 as a means to augment beneficial microglia functions. Agonistic antibodies have been reported to facilitate microglial encapsulation of amyloid plaques (Price et al., 2020; Schlepckow et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b; Fassler et al., 2021), deter tau pathology (Fassler et al., 2023), correct lipid handling and accelerate remyelination after lysolecithin-mediated demyelination (Bosch-Queralt et al., 2021), and facilitate debris clearance and remyelination after cuprizone (CPZ)-mediated demyelination (Cignarella et al., 2020). Furthermore, agonistic antibodies engineered to engage the transferrin receptor were found to correct metabolic changes in microglia (van Lengerich et al., 2023), and antibodies engineered to act as tetravalent ligands were reported to greatly enhance microglia engagement with Aβ plaques (Zhao et al., 2022b,c). However, other studies have identified a loss of responsiveness with repeated agonist treatment (Ellwanger et al., 2021) and an increase in tau pathology and neuritic dystrophy after chronic TREM2 agonist treatment in mice with combined tau and Aβ pathology (Jain et al., 2023). As with agonistic antibodies, genetic engineering to enhance TREM2 signaling has led to mixed outcomes in AD models, with benefit from overexpression or detriment from surface stabilization accompanied by shedding reduction and strong differences with disease stage (Lee et al., 2018; Ruganzu et al., 2021; Dhandapani et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2022a; Peng et al., 2023). Surface-stabilizing TREM2 mutations extended inflammatory responses and partially improved myelination levels after cuprizone injury in mice (Beckmann et al., 2023).

We previously applied parallel lineage repertoire mining to identify a TREM2 agonist antibody, Para.09 (Hsiao et al., under review). Para.09 binds to the stalk region of TREM2 with high affinity, resulting in downstream signaling activation in reporter cells and reduced soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) shedding. Notably, Para.09 binds to the extracellular domain of TREM2 without binding to the cleaved sTREM2 fragment, as the epitope encompasses residues both upstream and downstream of the ADAM protease cleavage site. Here, we find that Para.09 evokes SYK phosphorylation and trophic signaling from a human induced pluripotent stem cell (IPSC)–derived microglia and other TREM2-expressing macrophages. We test Para.09 in multiple AD models (PS2APP and TauPS2APP mice) and in multiple remyelination paradigms (lysolecithin and cuprizone injury models). Although evidence of TREM2 target engagement and TREM2-dependent responses were observed in the dose range tested, no change was detected in AD-related pathology, nor was any improvement in recovery from demyelinating injury observed. Instead, Para.09 slowed debris clearance and deterred recovery after demyelinating lesions. Contrary to prior reports, we found that two additional TREM2 agonistic antibodies exhibited similar effects as Para.09 in AD and remyelination models. These findings illuminate undesirable consequences of TREM2 agonism in disease models and highlight important considerations for achieving TREM2 enhancement therapeutically.

Materials and Methods

Test material

Antibodies were stored at 4°C in 20 mM histidine acetate and 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.5, at concentrations of 5–20 mg/ml. Antibodies were diluted into assay buffer for in vitro assays or saline for in vivo dosing just prior to administration.

Isolation and culture of human monocyte–derived macrophages

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from consenting healthy donor buffy coats using Ficoll Paque Plus (Sigma-Aldrich). Next, CD14+C16− monocytes were isolated from PBMCs using the classical monocyte isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) per kit instructions. Purified monocytes were collected and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min and then resuspended in the growth medium. Cells were diluted to a final concentration of 10% DMSO, frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen for future use. For each experiment, aliquots from multiple donors were thawed, and human monocyte–derived macrophages (hMDMs) were differentiated in culture for 5–7 d in the growth medium [high-glucose DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated serum and 50 ng/ml recombinant human M-CSF (PeproTech)] with partial media changes every other day.

CRISPR editing of hMDMs

To form guide RNA duplexes, Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 nontargeting control crRNA or crRNA targeting TREM2 of sequences TTGTAGATTCCGCAGCGTAA, AATGGTGAGAGTGCCACCCA, or TACCAGTGCCAGAGCCTCCA (Integrated DNA Technologies) was dissolved to 100 µM in duplex buffer (Integrated DNA Technologies) and mixed at a 1:1 molar ratio with Alt-R tracrRNA dissolved at 100 µM in duplex buffer. The crRNA and tracrRNA mixtures were hybridized by incubation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 15 min incubation at room temperature and storage at −20°C. Ribonucleoprotein complexes were formed by mixing crRNA/tracrRNA duplexes with 5 µg Alt-RS.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 (Integrated DNA Technologies) at a 3:1 molar ratio and incubated at room temperature for at least 15 min. The three ribonucleoprotein complexes for the three separate guide RNA sequences targeting TREM2 were combined at an equimolar ratio, and all three guide RNA complexes were transfected together into hMDMs. RNPs with nontargeting control guide RNA were formed in the same way.

To generate TREM2-deficient cell pools, hMDMs were collected 16–24 h after thawing, centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min, and resuspended in P3 primary nucleofection solution (Lonza) to a concentration of 2–4 × 106 cells per 20 µl reaction. Each 20 µl reaction was mixed with a total of 10 µg of Cas9 complexed with the three TREM2-targeting guide RNAs and immediately transferred to supplied nucleofector cassette strips (Lonza). The strip was loaded into the Lonza 4D-Nucleofector (4D-Nucleofector Core Unit, Lonza, AAF-1002B; 4D-Nucleofector X Unit, AAF-1002X) and electroporated using the CM-137 pulse program. Cells were recovered, diluted into the growth medium to 106 cells per ml, and plated for 5–7 d. Efficient knock-out (>90%) was confirmed by TIDE analysis and FACS.

hMDM SYK phosphorylation measurements

hMDMs were plated in 96-well plates for 5–7 d and then exchanged into a medium of low-glucose DMEM (1 g/L glucose) without M-CSF and serum. Cells were returned to the incubator for 24 h prior to antibody treatment. Antibodies were applied for 20 min (Fig. 1) or 10 min (Fig. 8) at 37°C. Following antibody stimulation, culture media were removed, and cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing cOmplete mini protease inhibitor (Roche) and phosSTOP (Roche) phosphatase inhibitors. Total SYK and phosphorylated SYK (pSYK) were measured using the respective AlphaLISA SureFire Ultra assays (PerkinElmer) per kit instructions. Briefly, protein lysates were incubated with acceptor beads for 1 h followed by a subsequent 1 h incubation with streptavidin-coated donor beads in the dark. Plates were then imaged using the compatible Synergy Neo2 plate reader (BioTek). Phosphorylated SYK levels were normalized to total SYK in each sample.

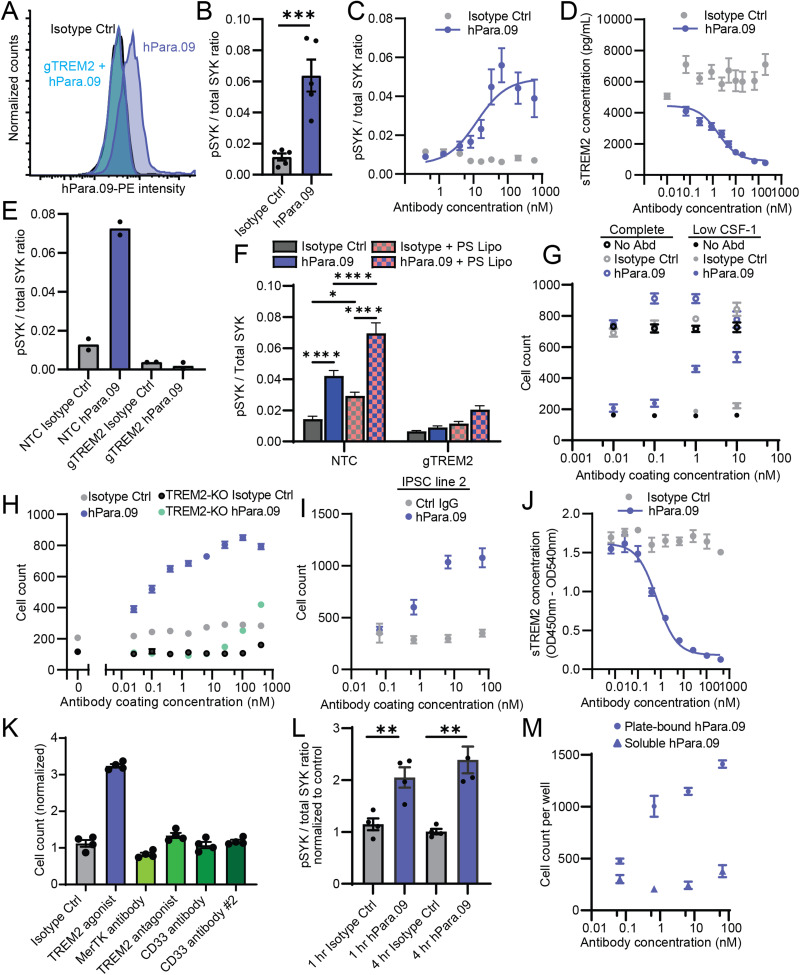

Figure 1.

In vitro signaling and survival activity of TREM2 agonist antibody hPara.09. A, Flow cytometry histograms showing surface staining of hMDMs with PE-conjugated Para.09 or isotype control (hIgG1.N297G) antibody. Cells were treated with Cas9 and TREM2-targeting guide RNA (gTREM2, aqua trace) or control guide RNA. B, SYK phosphorylation in hMDM lysate 20 min after soluble antibody treatment (15 nM). C, hMDM pSYK dose–response. D, sTREM2 in hMDM supernatant 48 h after soluble antibody treatment. E, hMDM SYK phosphorylation from antibody treatment in cells treated with Cas9 and TREM2-targeting guide RNA (gTREM2) or nontargeting control guide RNA (NTC). F, hMDM SYK phosphorylation in response to soluble antibody, phosphatidylserine-containing liposomes, or their combination. Cells were treated with Cas9 and nontargeting control guide RNA (NTC) or TREM2-targeting guide RNA (gTREM2). G, IPSC-MG survival 72 h after plating onto antibody-coated plates in complete medium (open circles) or growth factor–restricted medium (closed circles) comparing antibody treatment conditions. H, IPSC-MG survival 72 h after plating onto antibody-coated plates in growth factor–restricted medium comparing WT IPSC-MG to IPSC-MG lacking TREM2 (TREM2-KO). I, Same as in H using microglia derived from a separate IPSC line (WC30). J, IPSC-MG sTREM2 in supernatant 48 h after soluble antibody treatment. K, IPSC-MG survival 72 h after plating onto TREM2 agonist, TREM2 antagonist, or other surface receptor antibodies. L, IPSC-MG SYK phosphorylation at 1 or 4 h after plating onto antibody-coated plates. Responses are normalized to the isotype control average at each time point. M, IPSC-MG survival 72 h after plating onto hPara.09-coated plates (circles) or treatment with soluble hPara.09 (triangles) in growth factor–restricted medium. Points represent mean ± SEM. In B–E, 2–6 biological replicates (2–6 separate donors) with each point reporting the average of 2–3 technical replicates per donor and combined from at least two independent experiments. In F–M, four technical replicates are representative of at least two independent experiments.*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 unpaired t test in B and L, or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's test in F. The lines in C, D, and J indicate Hill equation fits with the slope fixed at 1.

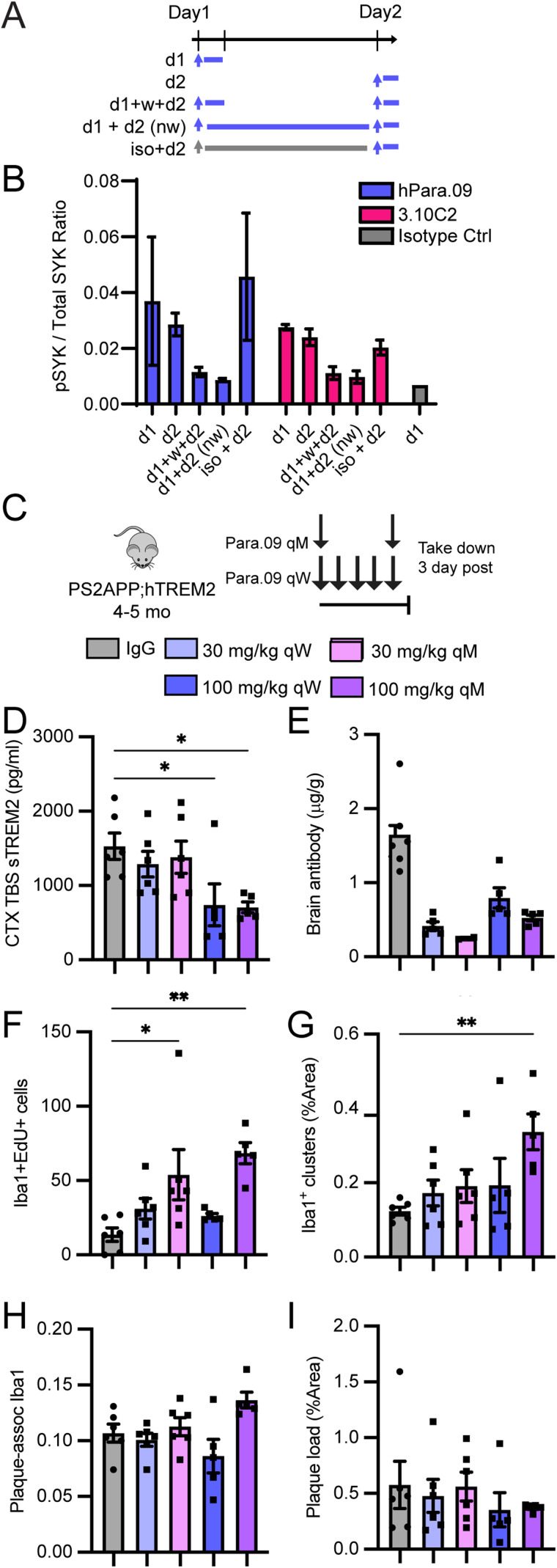

Figure 8.

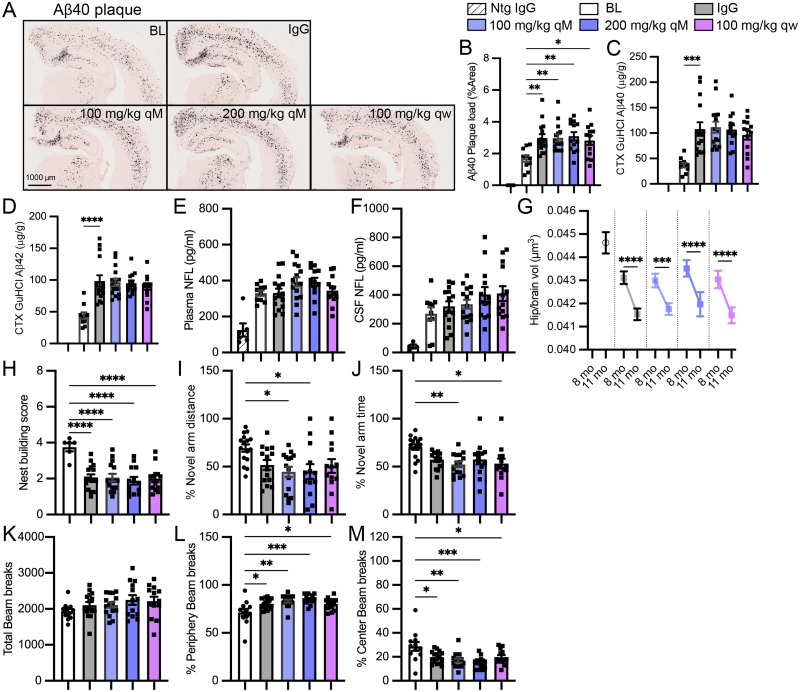

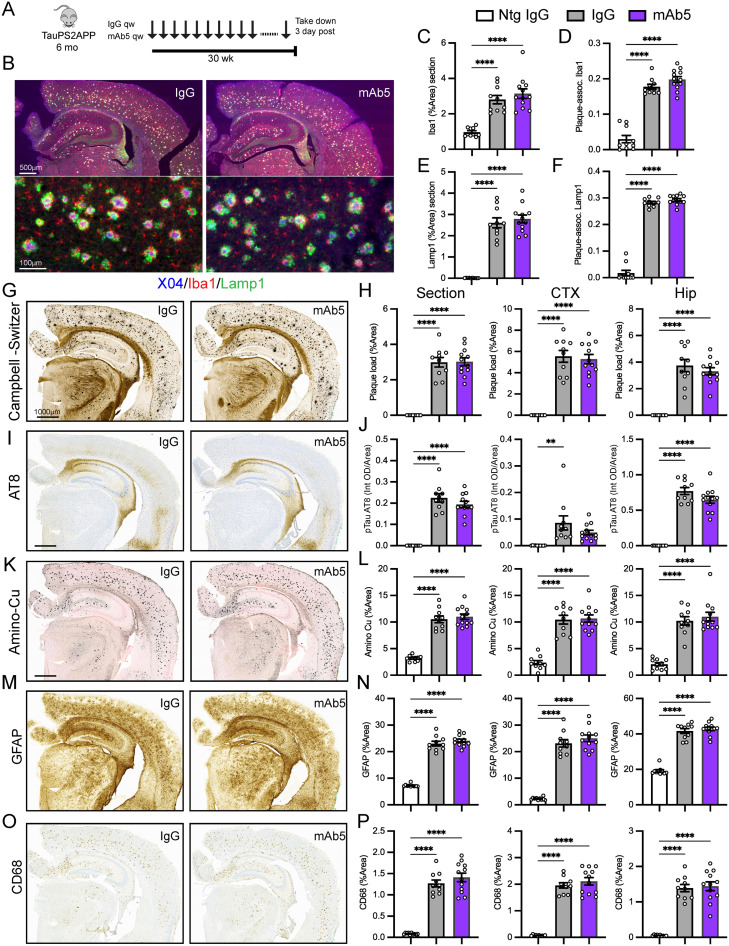

Cellular responses to continuous versus intermittent antibody stimulation. A, Schematic describing treatment groups for in vitro stimulation of hMDMs with single or repeated exposure to antibody. Cell lysates were collected 20 min after the last antibody treatment pulse (either 20 min after Day 1 stimulation for the d1 group or 20 min after Day 2 stimulation for other groups). B, hMDM SYK phosphorylation responses to hPara.09 (blue) or related agonistic antibody 3.10.C2 (red) after single or repeated exposure to the antibody. Isotype control single-treatment effects are shown in gray for comparison. C, Schematic illustrating monthly versus weekly dosing paradigms at 30 or 100 mg/kg. IgG denotes an inactive isotype control antibody. D, sTREM2 concentration in brain homogenate soluble fraction. E, Dose antibody concentration in brain homogenate normalized to tissue weight. F, Counts of proliferating microglia per tissue section measured histologically by overlapping EdU+ Iba1+ cells. G, %Area of full coronal tissue sections occupied by clusters of microglia. H, %Area around X-04 plaques occupied by microglia (Iba1 staining). I, %Area of full coronal tissue sections occupied by methoxy-X04 amyloid plaques. Bars represent mean ± SEM. In A, three technical replicates are representative of two independent experiments. In F–I, the points are individual animal means from three sections per animal. ANOVA followed by Tukey's t test versus IgG-negative control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

hMDM sTREM2 shedding measurements

Thawed human monocytes were seeded at 100,000 cells per well in 96-well tissue culture plates and differentiated in the presence of human M-CSF for 5–7 d in culture. Afterward, the medium was aspirated and replaced with 100 μl of growth medium without M-CSF, with appropriate concentrations of anti-TREM2 (RO7535836) or isotype control antibody. Cells were returned to the 37°C incubator for 48 h, at which point supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C. sTREM2 concentrations were measured from hMDM supernatants using a human TREM2 (hTREM2) Simple Plex assay (ProteinSimple) and an automated immunoassay system (Ella, ProteinSimple) following the manufacturer's protocols.

IPSC-derived microglia medium composition, cell thawing, seeding, and culture

Basal microglia medium consisted of BrainPhys basal media without phenol red (catalog #05791; STEMCELL Technologies) containing Invitrogen B-27 Supplement (catalog #17504044; Thermo Fisher Scientific), Invitrogen N-2 Supplement (catalog #17502001; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mM creatine (catalog #C3630; Sigma-Aldrich), 200 nM ʟ-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium (catalog #A8960-5G; Sigma-Aldrich), 20 ng/ml recombinant brain-derived neurotrophic factor (catalog #450-02; PeproTech), 20 ng/ml recombinant human glial cell–derived neurotrophic factor (catalog #450-05; PeproTech), 1 µg/ml Invitrogen laminin mouse protein (catalog #23017015; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5 mM Invitrogen GlutaMAX Supplement (catalog #35050061; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 50 U/ml Invitrogen penicillin-streptomycin (catalog #15140122; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.1 mg/ml Normocin (catalog #ant-nr-1; InvivoGen), 5 ng/ml recombinant human transforming growth factor β1 (HEK293-derived; catalog #100-21; PeproTech), 1.5 ng/ml ovine wool cholesterol (catalog #700000P; Avanti Polar Lipids), 0.1 ng/ml oleic acid (catalog #90260; Cayman Chemical), 0.001 ng/ml 11(Z)-eicosenoic acid (catalog #33186; Cayman Chemical), 460 µM 1-thioglycerol (catalog #M1753; Sigma-Aldrich), Invitrogen insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS-G; catalog #41400045; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 5.4 µg/ml human insulin solution (catalog #12585014; Sigma-Aldrich). To obtain a complete microglia culture medium, the basal medium was supplemented with 100 ng/ml recombinant human interleukin (IL)-34 (catalog #200-34; PeproTech) and 25 ng/ml recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; catalog #300-25; PeproTech).

Human wild-type induced pluripotent stem cell–derived microglia (IPSC-MG; iCell Microglia; catalog #01279; Fujifilm Cellular Dynamics) were thawed in a complete microglia culture medium. A second IPSC line, WC-30, was obtained from BrainXell and differentiated into IPSC-MG using the STEMdiff Microglia Differentiation Kit (catalog #100-0019, STEMCELL Technologies). After differentiation, WC-30 IPSC-MG were frozen in media with 10% DMSO. Cells were thawed for each assay, counted, centrifuged, and resuspended in a complete microglia culture medium. Cells were seeded on plates and briefly centrifuged before culturing at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity.

IPSC-MG cytokine measurements

Cells were seeded in each antibody-coated well at 4,000 cells per well (WC-30 line) or 8,000 cells per well (FCDI line). Cells were incubated for 24 h, after which supernatants were carefully collected using a pipetting robot (Assist Plus; Integra Biosciences) and stored at −80°C prior to assays. Each sample was tested using human cytokine Luminex assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Only the subset of analytes that were within the dynamic range of the assay for all samples were included in the downstream analysis.

Samples were also tested using a separate method based on homogenous time-resolve fluorescence (HTRF). Supernatants were generated for Luminex panel assays, and TNF concentrations were measured using a human TNF-α HTRF kit (catalog #62HTNFAPET, Cisbio). Baseline (BL) subtraction was conducted using standards diluted in a complete microglia culture medium.

IPSC-MG sTREM2 shedding measurements

For sTREM2 shedding experiments, cells were plated on fibronectin-coated plates and stimulated with soluble antibodies. Greiner µClear 96-well tissue culture plates were coated with 50 µl of 20 µg/ml of fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, diluted in PBS solution) overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. The coating solution was removed before plating IPSC-MG at 50,000 cells per well in a complete microglia culture medium. Anti-TREM2 (RO7535836) or isotype control antibody was then added to each well. Cells were placed in a 37°C incubator for 48 h, at which point supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C. sTREM2 concentrations were measured from hMDM supernatants using a human TREM2 DuoSet ELISA (R&D Systems). Cell viability was confirmed visually in all wells via microscopy.

IPSC-MG SYK phosphorylation measurements

To measure SYK phosphorylation, IPSC-MG were cultured on antibody-coated 48-well plates in a minimal microglia culture medium. Cells were plated for 1, 4, or 24 h, the culture medium was removed, and 100 µl of freshly prepared 1× lysis buffer (lysis buffer ultra, PerkinElmer) was added to each well. Plates were agitated on a plate shaker (350 rpm) for 10 min at room temperature and transferred to a 96-well deep well plate (Greiner Bio-One) for storage at –80°C. SYK phosphorylation and total SYK levels were analyzed using the respective AlphaLISA SureFire Ultra assays (PerkinElmer) per kit instructions. Measured phosphorylated SYK levels were normalized to total SYK in each sample.

Plate-bound antibody stimulation of IPSC-MG

IPSC-MG were stimulated with plate-bound antibodies. Four antibodies were tested: an inactive negative control antibody on a reduced-effector backbone (gD.hIgG1.N297G), RO7535836, an inactive antibody on a full-effector hIgG1 backbone (gD.hIgG1), and an antibody with the same TREM2-binding variable region as RO7535836 but with a full-effector hIgG1 backbone (Para.09.hIgG1).

Prior to plating cells, 384-well PhenoPlate microplates (catalog #6057302; PerkinElmer) were coated with antibody solutions using a pipetting robot (Assist Plus; Integra Biosciences) equipped with an automatic multichannel pipette (125 µl Voyager; Integra Biosciences). Coating solutions of 10 µg/ml of RO7535836 or comparator antibodies were prepared in cold DMEM/F12 (catalog #11554546; Invitrogen) before addition to plates. Plates were incubated with antibody solutions at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity overnight. Antibody solutions were removed via aspiration prior to seeding cells.

IPSC-MG survival assays

For survival assays, cells were seeded in antibody-coated 384-well plates (CellCarrier Ultra, PerkinElmer) at 8,000 cells/well in 50 µl of minimal microglia culture medium. After 3 d of culture, supernatants of cells were removed by a pipetting robot (Assist Plus, Integra Biosciences) equipped with an automatic multichannel pipette (125 µl Voyager, Integra Biosciences). Aspiration speed was set to 2 µl/s, and pipetting height was kept at 1–1.2 mm above the plate bottom to avoid disturbance of the cell layer. In addition, 30 µl/well was transferred to a 384-well microplate (Greiner Bio-One). Right after supernatant collection, cells were fixed in 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and 4% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature. After fixation, cells were washed twice with DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cells were counted by immunostaining and imaging. For immunostaining, cells were incubated with a blocking buffer containing 2% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch), 1% BSA (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary rabbit anti-Iba1 polyclonal antibody (1:500, Wako) was diluted in blocking solution and incubated for 1 h at room temperature, and cells were washed three times with blocking buffer. Secondary Cy3 donkey anti-rabbit (1:600, Jackson ImmunoResearch), Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (1:1,000, Invitrogen), and Hoechst 33342 (1:10,000, Invitrogen) were prepared in blocking buffer and incubated for another hour at room temperature. After secondary staining, cells were washed six times by repeat addition and aspiration of DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored in the dark until imaging.

Stained IPSC-MG were imaged on an automated high-content imager (Opera Phenix High-Content Screening System, PerkinElmer) equipped with a 20× water immersion objective. Tile scans (3 × 3 tiles) of all wells were acquired in spinning disk confocal mode (image size, 1,080 × 1,080 pixels; pixel size, 0.598 µm), resulting in an effective FOV of 2.88 mm2 (∼27% of each well). Each position was imaged in three fluorescent channels. Excitation of nuclear dye Hoechst 33342 was performed at 405 nm, and the main emitted signal was detected at 456 nm. Actin was detected at 522 nm by excitation of Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin at 488 nm. Iba1 was visualized by excitation of Cy3 at 561 nm, mainly emitting at 599 nm.

IPSC-MG amyloid-β plaque formation assays

IPSC-MG were cultured on a plate-bound antibody in minimal microglia culture medium for survival assays, except in the presence of amyloid-β oligomers. Aβ oligomers were generated by incubating reconstituted Aβ monomer (1–42; AnaSpec) to 100 µM in BrainPhys basal media at 4°C for 24 h. Aβ oligomers were applied to cells right after plating at a final concentration of 2.5 µM. Cells were incubated for 2 d and then fixed and stained for Aβ, methoxy-X04 (amyloid plaque dye), and Iba1. Microplates containing stained microglia were imaged on an automated high-content imager (In Cell Analyzer 6000, GE HealthCare) equipped with a 20× air objective. Tile scans (3 × 3 tiles) of all wells were acquired. Each position was imaged in four fluorescent channels. Excitation of Aβ plaque binding dye methoxy-X04 was performed at 405 nm, and the main emitted signal was detected at 456 nm. Actin was detected at 522 nm by excitation of Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin at 488 nm. Iba1 was visualized by excitation of Cy3 at 561 nm, mainly emitting at 599 nm. Aβ was visualized by an anti-6E10 antibody using an excitation wavelength of 647 nm.

Mice

All animal care and handling procedures were reviewed and approved by the Genentech IACUC and were conducted in full compliance with regulatory statutes, IACUC policies, and NIH guidelines. Animals were housed in SPF (specific pathogen-free) conditions with 12 h light/dark cycle and maintained on regular chow diets unless otherwise specified. The TauPS2APP model was generated as described (Grueninger et al., 2010), by crossing PS2APP mice (Ozmen et al., 2009) with the pR5-183 line expressing the human tau P301L mutant (Gotz et al., 2001), with animals maintained as PS2APP-homozygous and P301L-hemizygous transgenes. Human TREM2 (hTREM2) bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) cassette was inserted in a Trem2 knock-out mouse background to generate hTREM2 transgenic animals and then crossed with PS2APP;Trem2ko or TauPS2APP;Trem2ko mice to generate PS2APP;hTREM2 and TauPS2APP;hTREM2 mice. Trem2 knock-out mice used for the BAC transgenic line retained a neomycin cassette, which leads to the aberrant overexpression of the neighboring gene, Treml1 (Kang et al., 2018). The neomycin cassette was deleted for TauPS2APP experiments but was retained in mice used in PS2APP, cuprizone, and lysolecithin experiments.

Mouse dosing and tissue collection

Mice were dosed with antibodies by intraperitoneal administration. Antibodies dosed in mice comprised an mIgG2a LALAPG backbone (to ensure lack of Fc effector function in mice as stated above) unless otherwise specified.

At experiment completion, mice were anesthetized with 2.5% tribromoethanol (0.5 ml/25 g body weight), CSF was collected from the cisterna magna using a 26 gauge needle, and blood (0.3–0.5 ml) was collected by cardiac puncture into the K2EDTA tubes. Plasma tubes were placed on ice, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 2 min. Mice were perfused with cold PBS, and then brains were removed and split down the midline. One hemibrain was drop-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h at 4°C, transferred to PBS to wash, transferred into PBS with 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection, and stored at 4°C.

The unfixed hemisphere was dissected into the hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum, quickly frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until tissues were lysed. Cerebellum tissues were homogenized in 1% NP40 in PBS and used for antibody concentration measurements. Ten volumes of TBS (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog #4693159001; Roche) and PhosSTOP (catalog #4906837001; Roche) were added to cortical tissue (1 ml for every 100 mg tissue). Subsequently, one 3 mm stainless steel bead (Qiagen) was added into each tube, and samples were homogenized with the Qiagen TissueLyser II at 30 Hz for 3 min at 4°C. The homogenized samples were then cleared by centrifugation at 20,000× g for 20 min at 4°C. Supernatants were transferred to new tubes and stored at −80°C as soluble TBS fractions. To the remaining pellet, 10 volumes of 5 M guanidine HCL were added, homogenized in Qiagen TissueLyser II at 30 Hz for 30 s at 4°C, and rotated at room temperature for 3 h. Cortical samples were then diluted at 1:10 in a 1% casein buffer in PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog #4693159001; Roche), PhosSTOP (catalog #4906837001; Roche), leupeptin (10 µg/ml), and aprotinin (20 µg/ml).

Isolation of microglia, neurons, and astrocytes by FACS

Animals were transcardially perfused with 30 ml of ice-cold PBS, and the cortex from a hemibrain was dissected. Cell suspensions were prepared from dissociated tissues, and cells were stained as described previously (Srinivasan et al., 2016; Meilandt et al., 2020). All steps were performed on ice or at 4°C to prevent artifactual microglial activation. At least one animal from each group was processed together from perfusion through sorting. The BD FACSAria Fusion Flow Cytometer was used for sorting.

After perfusion, tissue was minced into smaller pieces using a fresh chilled razor blade and transferred to a round-bottom 2 ml Eppendorf tube containing 1.6 ml of Accutase (SCR005, MilliporeSigma). The tissue was rotated at 4°C for 20 min and spun at 1,000 × g for 2 min in a refrigerated centrifuge. The supernatant was discarded and 1.5 ml of Hibernate A Low-Fluorescence medium (BrainBits) was added to the tissue. The tissue was manually and carefully triturated using a 1 ml tip seven or eight times. The cell suspension was kept on ice for 10–15 s to allow for the larger tissue to settle. The top cloudy 1 ml of cell suspension was removed and passed through a 70 µm prewetted filter. A fresh 1 ml of Hibernate A was then added to the cell suspension, and the trituration was repeated until a total of 5–6 ml of cell suspension was obtained. Cells were centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 4 min and resuspended in 1 ml of Hibernate A.

For live microglia sorting, mouse Fc block (Miltenyi Biotec 130-092-575) and the following antibodies were added to the cell suspension and incubated for 30 min at 4°C on a rotator: APC-conjugated anti-CD11b (BD Biosciences, 561690, 1:200), PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-CD45 (BD Biosciences, 552848, 1:500), PE-conjugated anti-Ly6g (Tonbo Biosciences, 35-5931, 1:200), PE-conjugated anti-Ccr2 (R&D Systems, FAB5538P, 1:200), and PE-conjugated Lyve-1 (NB100-725PE). Samples were briefly washed and stained with Sytox Blue (S34857) before FACS sorting. Myeloid cells were selected by gating live (Sytox Blue-negative) cells for CD11b and medium CD45 immunoreactivity. To avoid the presence of peripheral myeloid cells in the flow analysis and FACS collections, we excluded the Ccr2-positive cells (peripheral monocytes/macrophages), Ly6g+ cells (neutrophils), and perivascular macrophages (Lyve-1 positive). Microglia cells were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 8 min, and RNA was extracted from cell pellets using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen 80204).

For sorting different cell types, 1 ml of ice-cold 100% ethanol was added drop by drop while gently swirling the falcon tube containing cells on ice to uniformly and gently fix the cells and allow for intracellular staining. After the cells were mixed to a final concentration of 50% ethanol, the falcon tube was kept on ice for 15 min. The fixed cells were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 5 min, and the resulting supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was resuspended gently in 2 ml of ice-cold Hibernate A to wash with residual ethanol, centrifugation was repeated, and cells were finally resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold Hibernate A and aliquoted for immunostaining. Cells were incubated with Fc block and the following cell-type marker antibodies: APC-Cd11b (561690, BD Biosciences) 488-NeuN (MAB377X, MilliporeSigma), and PE-GFAP (561483, BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C on a rotator. Samples were briefly washed and stained with Sytox Blue (S34857) before FACS sorting. After removing debris and selecting Sytox Blue-positive single cells, Cd11b+ NeuN− GFAP−; NeuN+ Cd11b− GFAP−; GFAP+ Cd11b− NeuN− cells were gated. Cells were centrifuged at 2,600 × g for 7 min (neurons) or 5,000 × g for 8 min (other cell types). RNA was extracted from cell pellets using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen 80204).

Following staining, cells were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 min in a refrigerated centrifuge followed by two brief washes in 1 ml of Hibernate A. Cells were resuspended in 2 ml of Hibernate A, and Sytox Blue (S34857) was added to all the tubes and passed through a 40 µm filter before sorting. Cells were sorted into protein LoBind tubes (022431081, Eppendorf) containing 100 µl of Hibernate A medium and centrifuged at 2,600 × g for 7 min (neurons) or 5,000 × g for 8 min (other cell types). Cell pellets were resuspended in 350 µl of buffer RLT, and RNA was extracted using RNeasy Micro kits (Qiagen)

RNA isolation and gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from four to five fixed 35-µm-thick brain sections (like those used for IHC) per animal using RNeasy FFPE kit (catalog #73504; Qiagen) or from FACS-sorted cells using RNeasy Micro kits (Qiagen).

The concentration of RNA samples was determined using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix), and the integrity of RNA was determined by 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Approximately 1–5 ng of total RNA was used as an input material for the library generation using SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA kit (Takara Bio). The size of the libraries was confirmed using 4200 TapeStation and High Sensitivity D1K screen tape (Agilent Technologies), and their concentration was determined by a qPCR-based method using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit. The libraries were multiplexed and then sequenced on HiSeq 4000 (Illumina) to generate 30 M of single-end 50 bp reads.

Bulk RNA-seq data were analyzed as previously described (Srinivasan et al., 2020). Reads were aligned to the GRCm38 genome with HTSeqGenie as previously described (Friedman et al., 2018), and reads overlapping each gene were quantified. Counts per million (CPM) were computed in a manner that preserves the relative scaling due to normalization factors as described in edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010) with prior.count set to 3. Differential expression was performed using voom and limma (Law et al., 2014). Log2-transformed values were centered and scaled to give z scores; for a given gene/sample combination, the z score represents the distance of logCPM value in SDs from the mean value for that gene across all samples within a dataset. Columns (samples) were organized by treatment.

The gene set scores for each gene set were calculated by computing the average logCPM value across all the genes in a given gene set for each sample.

Fluidigm qPCR from sorted cells

RNA from sorted cells was reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4368814, Applied Biosystems). Standard TaqMan FAM-MGB probes were ordered from Applied Biosystems for all qPCR assays. For preamplification, up to 100 qPCR assays (primer/probe sets in 20× stock concentration) were pooled and diluted to a 0.2× concentration. Five microlitres of pooled assays were combined with 2.5 µl of sample cDNA, 10 µl of 2× TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (1410056, Applied Biosystems), and 2.5 µl of TE buffer and preamplified for 14 cycles using the cycling conditions recommended by Applied Biosystems, in a 96-well plate (N8010560, Applied Biosystems) sealed tightly with a MicroAmp clear adhesive film (4306311, Applied Biosystems).

Fluidigm reactions were performed using the 96 × 96 or 48 × 48 chips and included 2–3 technical replicates for each combination of sample and assay. For sample mixtures, 2.5 µl preamplification product from sorted cell samples was combined with 20× GE Sample Loading Reagent (85000735, Fluidigm), 2× PCR master mix (58003365-01, Applied Biosystems), and TE buffer in a 10 µl volume, of which 5 µl was loaded into sample wells. For assay mixtures, equal volumes of TaqMan assay (or custom assay for splicing analyses) and 2× Assay Loading Reagent (85000736, Fluidigm) were combined, and 5 µl of the resulting mixture was loaded into multiple assay wells for technical replicates. The Ct values for each gene target were normalized to Ct values for housekeeping genes (Gapdh, Actb). Multiple cell-type markers were used to check for enrichment/depletion of expected markers for each cell-type sort: microglia (Cx3cr1, Itgam, Aif1, Apoe, Tmem119), neurons (Grin1, Grin2a, Rbfox3, Cx3cl1), and astrocytes (Gfap, Aldh1/1, Aqp4, Clu, Slc1a3). For Trem2 expression analysis, five different probes were used for human and mouse Trem2, and the best set used for the final analysis was Hs01010722 and Mm04209422.

Microglia myelin phagocytosis

For primary microglia cultures, P0–P2 pups were decapitated, and their brains were removed. Brain tissue was triturated with a 5 ml serological pipette and a long Pasteur glass pipette, and then homogenate was spun at 300 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended with a 1 ml pipette and filtered through a 40 µm filter. Two brains were cultured per 225 cm2 flask in 40 ml of high-glucose DMEM plus 10% FBS. Flasks were rinsed with PBS, and new media were added after 24 h. Astrocytes were allowed to proliferate and create a feeder layer at which point microglia began to proliferate. Cultures were grown for an additional 10–15 d before microglia were shaken off the astrocyte feeder layer on a rocking platform for 1 h. Cells were collected into 50 ml falcon tubes precoated with 10% FBS to prevent microglia attachment. In addition, 80 K microglia were seeded per well on a 96-well plate and cultured for at least 24 h before use in experiments. Myelin [prepared as previously described (Larocca and Norton, 2007)] labeled with pHrodo (Invitrogen pHrodo Red Microscale Labeling Kit, catalog #P35363) was added to the microglia (10 µg/ml) and incubated for 3 h. After incubation, cells were dislodged using enzyme-free PBS-based cell dissociation buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), washed and resuspended in a flow cytometry buffer (1× PBS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.05% sodium azide), and kept on ice. Sytox Blue staining was used to identify live cells. Flow cytometry was performed using LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences), and the mean PE fluorescence (myelin–pHrodo uptake) was calculated.

Antibody concentration determination in the plasma and brain

The blood collected by cardiac puncture was collected into tubes containing EDTA. Blood was allowed to sit on wet ice for up to 30 min before centrifugation at 14,000 RPM for 2 min. Plasma was harvested and placed on dry ice and then stored at −80°C. The antibody concentration of Para.09 and isotype control antibody was determined for both plasma and clarified cerebellum TBS plus NP40 homogenates by a generic mIgG2a Allotype A ELISA. The assay limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 0.00003125 µg/ml.

Human soluble TREM2 assay

The human TREM2 ELISA assay by R&D Systems (catalog #DY1828-05) was used to test for sTREM2 in plasma and brain homogenate. The human sTREM2 capture antibody (AF1828) that was provided in the assay kit was diluted in PBS and immobilized in 96-well plates. After blocking and washing the plate, diluted sample and standards were added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the human sTREM2 detection antibody was diluted and incubated for another 2 h. The plate was once again washed and incubated with streptavidin-HRP for 20 min followed by a substrate solution incubation of 20 min at room temperature. After stopping the reaction, the plate was read using two filters, 450 nm for detection and 570 nm for background. Concentrations were determined on a standard curve obtained by plotting optical density versus concentration. The lack of competition between Para.09 and detection/capture antibodies was confirmed by testing the effect of Para.09 addition into test samples of plasma or brain homogenate (Fig. 4A).

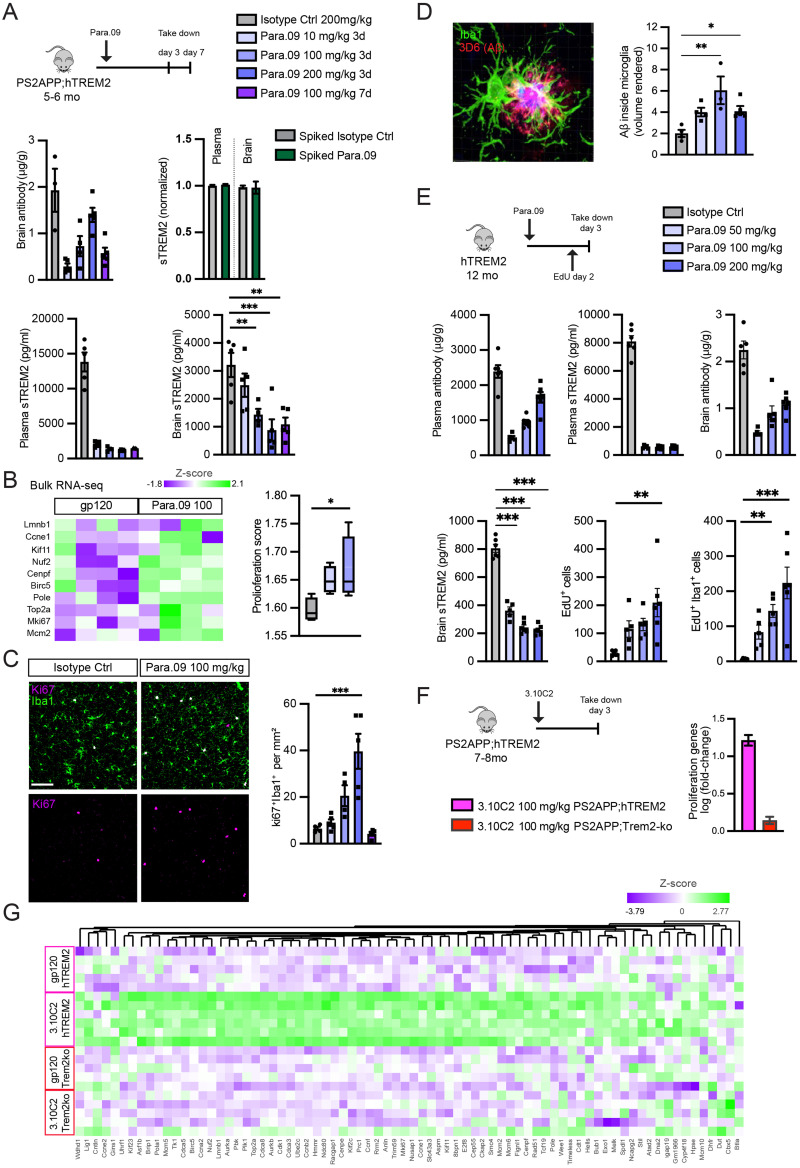

Figure 4.

In vivo responses to a single dose of Para.09. A, Response of PS2APP;hTREM2 mice 3 d after a single dose of Para.09 (10, 100, or 200 mg/kg) versus isotype control antibody (200 mg/kg) or 7 d after Para.09 (100 mg/kg). Concentration of dosed antibodies in brain homogenate (cerebellum), sTREM2 in plasma, and sTREM2 in brain homogenate (cortex) soluble fraction. Para.09 did not interfere with the sTREM2 detection assay, as spiking Para.09 into plasma or brain homogenate before measurement did not change values. B, Upregulation of proliferation markers after Para.09 dosing by bulk brain (hippocampus) RNA-seq. Expression of individual genes (left) or averaged expression score across the set of proliferation-associated markers (right). C, Representative images (left) and quantification (right) of microglial proliferation scored as Ki67 nuclear stain overlap with Iba1 (cortex). D, Representative image (left) and quantification (right) of microglia (Iba1) and Aβ (3D6) double-positive volume from confocal z-stacked images. E, Single-dose study in hTREM2 mice lacking AD pathology. EdU was dosed 18 h prior to takedown (50 mg/kg). Plasma antibody or sTREM2 concentrations, brain antibody (cerebellum), brain sTREM2 (cortex), brain EdU-positive proliferating cell counts, and brain EdU-positive proliferating microglia counts (Iba1/EdU colocalization) were all altered by Para.09 at expected concentrations. F, Averaged log2(fold change) of genes in the proliferation module between 3.10C2 and isotype control groups within PS2APP;hTREM2 mice (pink) or PS2APP;Trem2ko mice (red), showing hTREM2 dependence of antibody responses. G, Heatmap illustrating differential expression of all proliferation genes in the module after treatment with a Para.09 precursor TREM2 agonist antibody, 3.10C2. Bars represent mean ± SEM except in B, where they represent median, 25–75% (boxes), and minimum/maximum (bars). N = 4–6 biological replicates (separate mice) per plot. ANOVA followed by Tukey's test compared with Isotype Ctrl *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Tissue staining

For chromogenic Iba1, CD68, GFAP, AT8, Campbell–Switzer, Ab-40, and aminocupric silver, dMBP, and solochrome stains, fixed hemibrains were embedded up to 40 per block in a solid matrix and coronally sectioned into sheets of 35 µm thickness [MultiBrain processing by NeuroScience Associates (NSA)] as in our previous study (Meilandt et al., 2020). Sheets of sections were stored in a cryoprotectant (30% glycerol, 30% ethylene glycol in PBS) at –20°C until use. Sections were stained as described on the NSA website and as described previously (https://www.neuroscienceassociates.com/technologies/staining/; Lee et al., 2021).

For uninjured or AD model fluorescent Iba1, Lamp1, methoxy-X04, and 3D6 staining, unstained sheets prepared as above were washed in PBS. Sections were then washed in PBST (PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100) and then blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100. Microglia were labeled with rabbit anti-Iba1 (Wako 019-19741, 1:1,000), dystrophic neurites with rat anti-Lamp1 (Abcam ab25245, 1:2,000), and Aβ with 3D6 (1:6,000) in 1% BSA, 1% NGS, and PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 overnight at 4°C. Sheets of sections were washed 3 × 10 min in PBST, followed by incubation for 2 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies (donkey anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-rat IgG–conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 or Alexa Fluor 647, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:500). Sheets of sections were mounted onto slides with 0.1% gelatin in PBS and allowed to dry and adhere to the slide at room temperature. To label plaques, slides were incubated in 10 µM Methoxy-X04 in 40% ethanol in PBS for 10 min, washed briefly in PBS, differentiated in 0.2% NaOH in 80% ethanol for 2 min, washed, and allowed to dry. Slides were coverslipped with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Molecular Probes) and dried.

For Ki67 staining, the same procedure was followed as for other fluorescent stains above except that prior to blocking, sections were additionally incubated in antigen retrieval solution (Dako; Part No. S169984-2) at 90°C for 13 min and washed in PBS. Ki67 (1:500) primary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific MA5-47446) was used.

For EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) labeling, mice were injected 16–18 h prior to takedown (A10044 Thermo Fisher Scientific, 50 mg/kg) with the thymidine analog EdU, which gets incorporated specifically into dividing cells. Sections were processed for EdU staining using the Click-iT kit (C10337 Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer's instructions

For lysolecithin experiments, animals were perfused with 4% PFA instead of PBS to improve sensitivity for specific oligodendrocyte markers. Brains were postfixed in 4% PFA overnight, submerged into 30% sucrose, and then sectioned at 30 µm thickness using a microtome. Tissue sections were blocked with 20% NGS in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 2 h at room temperature. Sections containing the splenium of the corpus callosum were inspected for the presence of a lesion under a light microscope, and sections central to the lesion were transferred to slides for staining and imaging. Incubation with primary antibodies in blocking solutions occurred overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488, 555, or 647 from Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cy3 or Alexa Fluor 647 from Jackson ImmunoResearch) were incubated in 20% NGS in PBS at room temperature for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI Fluoromount (SouthernBiotech). The following primary antibodies were used: guinea pig anti-Iba1 (234004, Synaptic Systems, 1:800), rabbit anti-PU.1 (2266, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:333), rat anti-GFAP (13-0300, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:500), rabbit anti-Olig2 (AB9610, EMD Millipore, 1:500), mouse anti-CC1 (OP80, EMD Millipore, 1:500), mouse anti-GSTpi (610718, BD Biosciences, 1:500), mouse anti-dMBP (MAB8817, Abnova, 1:1,000), and rabbit anti-dMBP (AB5864, EMD Millipore, 1:1,000).

For cuprizone experiments, mice were given isoflurane until reaching a surgical plane of anesthesia and then were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% PFA. Brains were then extracted, postfixed in 4% PFA overnight, and sectioned by NSA as described above. Sections containing the splenium of the corpus callosum (planes −0.9 to −1.9 mm from the bregma) were selected for staining. For PU.1 and Olig2 staining, sections were blocked with 5% NDS in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Incubation with primary antibodies in blocking solutions occurred overnight at 4°C. Secondary donkey antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 or 647) were incubated in PBS at room temperature for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI Fluoromount (SouthernBiotech). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-PU.1 (2266, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:150) and goat anti-Olig2 (AF2418, R&D Systems, 1:500).

Tissue imaging

All images were collected, processed, and measured blinded to the treatment group.

IHC and silver stains were imaged on the Leica SCN400 whole-slide scanning system (Leica Microsystems) at 200× magnification. MATLAB (MathWorks) running on a high-performance computing cluster was used for all whole-slide image analysis, performed in a blinded manner. Quantification of CD68 or Iba1 staining and enlarged dark cluster areas (which coincided with the presence of amyloid plaques) was performed using morphometric-based methods as previously described (Le Pichon et al., 2013; Kallop et al., 2014). Analysis of aminocupric silver staining was performed using color thresholds and morphological operations. The plaque area was analyzed from slides stained using the Campbell–Switzer method with plaques appearing with a black or amber hue. Multiple color classifiers spanning narrow ranges in RGB and HSV space were created for positive and negative features. Plaques were segmented using these classifiers and applying adaptive thresholding, Euclidean distance transform, morphological operations, and reconstruction. The percentage plaque load, aminocupric degenerative, Iba1, CD68, or GFAP positivity for the entire section was calculated by normalizing the positive pixel area to the tissue section area and averaged from eight to eleven sections/animal. All images, segmentation overlays, and data were reviewed by a pathologist. ROIs containing the hippocampus were manually drawn.

Immunofluorescent slides costained for plaque, microglia, and Ki67 were imaged at 200× magnification using the NanoZoomer S60 or XR (Hamamatsu Photonics) digital whole-slide scanner or a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 with Zen software. Ideal exposure for each channel was determined based on samples with the brightest intensity and set for the whole set of slides to run as a batch. The total tissue area was detected by thresholding on the Iba1 signal and merging and processing the binary masks by morphological operations. Methoxy-X04 and Iba1 staining was analyzed using a top-hat filter and local threshold followed by morphological opening and closing. In addition, a minimum size of 34 µm2 was applied to exclude small areas of staining. The detected plaques were used as markers in a marker-controlled watershed segmentation to create watershed lines of separation. The plaque mask was then dilated by 17 µm but constrained to be within watershed lines to prevent the merging of plaques in close proximity during dilation. Total Iba1-positive staining was normalized to the whole tissue area. Plaque-associated Iba1 staining was constrained to be within the mask of the dilated area around the plaque and was normalized to the same area. Data were averaged from eight to nine sections per animal.

For Aβ engulfment stains, images were collected from three to four sections per animal, with four to five ROIs within each section, using a confocal laser scanning microscope LSM 780 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) using Zen 2.3 SP1 software (Carl Zeiss). Approximately 42 z-stack images at 0.5 mm intervals were collected with Plan Apochromat 63× objective. The ROI was selected based on the methoxy-X04 signal to image around amyloid plaques from the cortex (Layer 5). Each animal had 16–20 methoxy-X04–positive amyloid plaques with microglial surrounding them. Images were collected and processed blind to treatment. Image analysis was performed using the Imaris software. Volume rendering was done and thresholded at the same value. After processing, colocalization was used to measure the amount of Aβ (3D6 positive) present in the Iba1-positive microglia. A colocalized channel was established where A was Iba1 and B was Aβ.

LPC fluorescent stains were imaged using a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 with Zen software. Images were collected from three to four sections per animal. For Iba1, PU.1, GFAP, and dMBP, sections were imaged at 5×, capturing one or two images per section (sufficient to cover the majority or entire lesion). Olig2, CC1, and GSTpi were imaged at 20×, with two to three images taken per section. Image analysis was conducted using the ImageJ software. Lesion border ROIs were defined based on DAPI nucleus staining. Olig2-, CC1-, and GSTpi-positive cells within the lesion were manually counted using the ImageJ cell counter. For Iba1, PU.1, GFAP, and dMBP, a consistent threshold was applied to each channel in each experimental batch. The area fraction above the threshold within the ROI was then recorded.

LPC injection into the corpus callosum

Twelve-month-old female WT mice were used for the mAb5 LPC study. For Para.09 studies, young adult (3 months old) female WT and hTREM2 mice were used for therapeutic dosing regimen groups, and male hTREM2 mice were used for preventative dosing regimen groups. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and received slow-release meloxicam before being positioned in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting). To locate the bregma, we made a midline incision of the skin between the occiput and forehead. A small hole was drilled at 1.2 mm posterior and 0.5 mm lateral to the bregma to allow for a unilateral injection into the right hemisphere. For the injections, a 10 µl Hamilton syringe attached with a glass micropipette (MBB-BP-L-0, Origio), containing a 1% lysolecithin [L-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) from egg yolk, Sigma-Aldrich] solution, was carefully inserted 1.4 mm deep into the brain. The lysolecithin solution was slowly infused into the corpus callosum at a rate of 0.35 µl/min. The glass micropipette was left in place for an additional 3 min prior to retraction. Finally, the incision was closed with surgical adhesive. The animals were allowed to recover on a heating blanket and returned to the cage once completely awake and recovered.

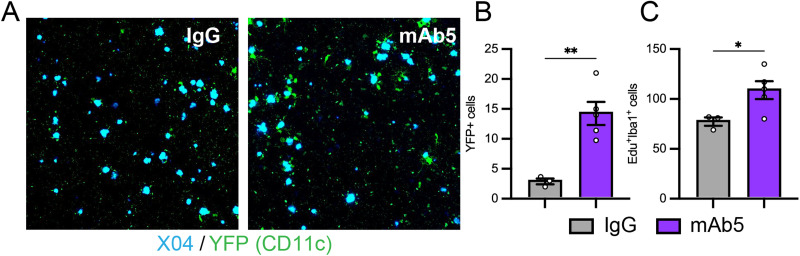

Two-photon microscopy

Following the dosing of mAb5 or control antibody, the somatosensory cortex of PS2APP mice was imaged ex vivo via two-photon microscopy. Twenty-four hours before brain harvesting, animals were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg/kg methoxy-X04 to visualize individual plaques (Klunk et al., 2002). Animals were killed and transcardially perfused with PBS, and brains were harvested, which were incubated for 48 h in 4% PFA and then washed and embedded in agarose for imaging. Amyloid plaque and activated microglia in the somatosensory cortex were imaged via a two-photon laser scanning microscope (Ultima In Vivo Multiphoton Microscopy System; Bruker) using Ti:sapphire lasers (Mai Tai DeepSee; Spectra-Physics) tuned to 840 and 900 nm for detection of amyloid and activated microglia, respectively. In addition, 250-µm-depth image stacks were collected using a 20× objective (Olympus) across a 1,024 × 1,024 pixel FOV using 2× zoom and 1.0 µm steps.

The resulting image stacks were preprocessed in Fiji (v1.53t) to spectrally unmix the YFP and methoxy-X04 signal using the Spectral Unmixing plugin (v1.3, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/plugins/spectral-unmixing.html). Subsequently, histogram matching was performed along the z-axis of the image stack to equilibrate intensity histograms axially. The image stacks were then loaded into the Imaris software (Oxford Instruments, v 10.0.1), and the surfaces were segmented for both YFP-positive microglia and methoxy-X04–positive plaques with local contrast thresholding and size filters. The Imaris object statistics were imported into MATLAB (MathWorks) for collation and plotting.

Volumetric and T2 MRI

For MRI acquisition, mice were imaged at either 7 T or 9.4 T with a four-channel receive-only cryogen-cooled surface coil and a volume transmit coil (Bruker). Mice were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane and placed on a 3D-printed custom-built in vivo animal holder (Stratasys and Formlabs printers) to position and secure the animal for imaging. A rectal probe was inserted, and the temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1°CC using a feedback system with warm air (S A Instruments). During imaging, anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% isoflurane. A T2 map covering the whole brain was generated using a multislice multiecho sequence with the following parameters: TR, 5.2 s; TE 1/spacing/TE12, 6.5/6.5/78 ms; matrix, 256 × 128 × 56; resolution, 75 × 150 × 300 µm; and acquisition time, 11 m 6 s.

Brain MRIs were processed and registered to the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas Common Coordinate Framework v3 (CCFv3; Wang et al., 2020a), using the ANTx2 processing pipeline as reported previously (Koch et al., 2019) and briefly described below. The multiecho image stacks were first averaged to maximize contrast-to-noise ratio and then corrected for field inhomogeneities. Next, images were segmented into tissue compartments using a modified SPMMouse framework. The images were then registered to CCFv3 using Elastix with a 12-parameter affine transformation followed by nonlinear warping. For the TauPS2APP mice, hippocampal region volumes were extracted and normalized to whole brain volumes to assess the hippocampal volume changes. For the cuprizone mice, the lesion T2 hyperintensities can impact the registration pipeline, so if baseline scans were acquired, postcuprizone images were registered to baseline using a rigid body transformation before registration to CCFv3. ROIs were drawn over the lesions in the splenium of the corpus callosum and genu of the corpus callosum in the registered CCFv3 space and used for assessing lesion severity.

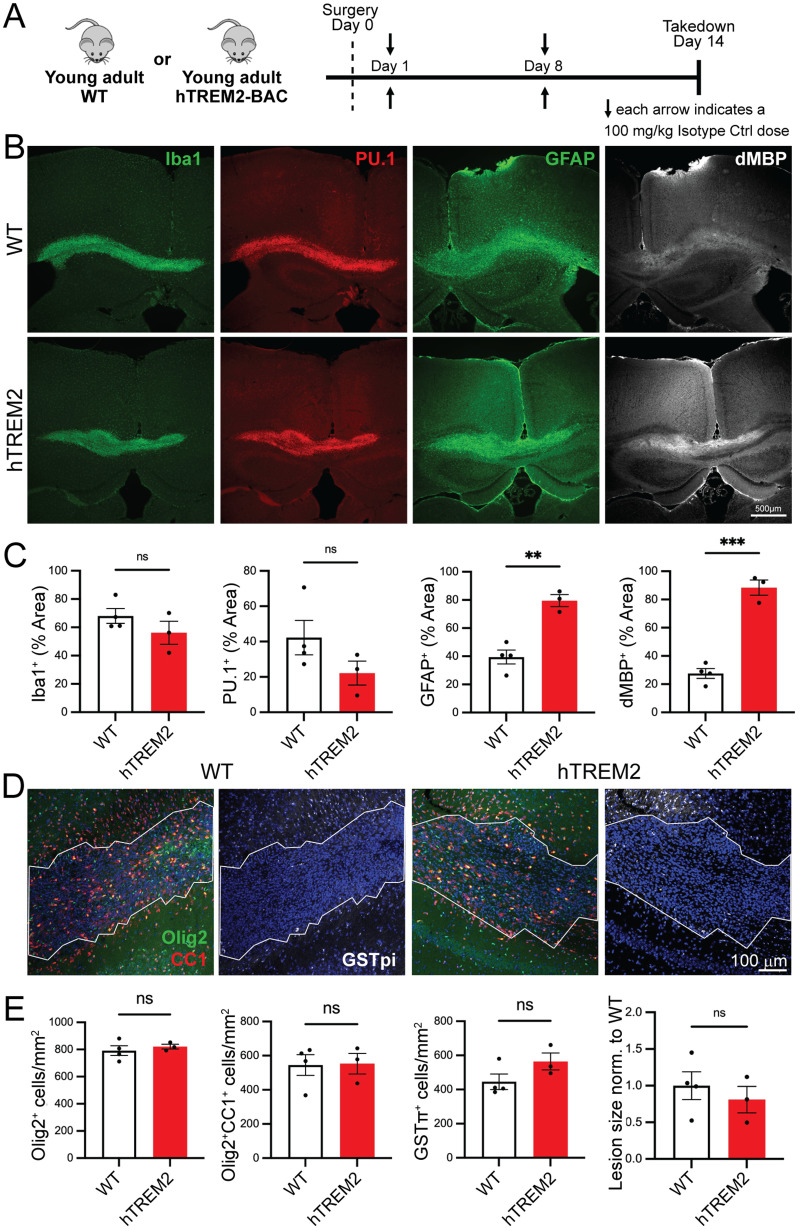

Chronic 12-week cuprizone study

A 0.25% cuprizone diet (Research Diets) was custom formulated using bis(cyclohexanone) oxalyldihydrazone purchased from TCI America (catalog #B0476) and was vacuum sealed and stored at 4°C until the start of the study. A total of 46 hTREM2 mice (male n = 20, female n = 26; 7–8 months old) and 9 mTREM2 mice (mTREM2WT/WT n = 4, mTREM2KO/KO n = 5; 4–6 months old) were randomly divided into five groups: (1) control diet mice were fed a normal diet (Research Diets) for the 12-week study duration and intraperitoneally injected with 100 mg/kg isotype control antibody weekly from Weeks 4 to 12. Mice in the cuprizone groups were placed on a 0.25% cuprizone diet (Research Diets) for 12 weeks and (2) intraperitoneally injected weekly from Weeks 4 to 12 with 100 mg/kg isotype control or (3) Para.09 antibody (total of nine doses). (4) The mTREM2WT/WT and (5) mTREM2KO/KO mice were placed on a 0.25% cuprizone diet (Research Diets) for 12 weeks and were not injected with an antibody to serve as benchmarking controls. All animals were killed 3 d after the last dose. All mice were monitored, and their weights were recorded weekly. In vivo T2-weighted MRI scanning (Bruker 7 T) was performed on hTREM2 groups at Week 3 to balance the demyelination signatures across the dose groups, and again at Week 11. T2 intensity measurements were performed in each ROI (genu and splenium of the corpus callosum).

Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine/acepromazine combination and perfused with ice-cold PBS. The anterior forebrain (including olfactory bulbs) was harvested and frozen on dry ice and then stored at −80°C for pharmacokinetic (PK) measurement. The intermediate forebrain (including the genu region of the corpus callosum) was harvested and frozen on dry ice and then stored at −80°C for lipidomics. All brain tissues (≤100 mg) were stored in 2 ml reinforced tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Lipidomic analysis: the mouse brain was homogenized in dichloromethane (DCM):methanol (1:1, v/v). After centrifugation, 10 mg tissue homogenate was transferred into a v-bottom glass tube. Next, 1 ml of water, 0.75 ml of DCM, and 1.85 ml of methanol were added to the supernatant to form a single phase. After 30 min, isotope-labeled standards with known concentrations were added to the mixture, followed by 0.9 ml of DCM and 1 ml of water. The mixture was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 20 min. Phase separation was achieved after centrifugation. The bottom layer was then collected into a clean glass tube, and the upper layer was re-extracted by adding 1.8 ml of DCM. The bottom layer was combined and dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted in 300 µl of DCM:methanol (1:1), 10 mM ammonium acetate for Lipidyzer platform direct infusion analysis (Cao et al., 2020) on AB Sciex 6500+ LC-MS/MS. The flow rate is set at 7 µl/min with a 50 µl injection volume. The autosampler temperature was kept at 15°C. Buffers A and B are the same as the reconstitution buffer [DCM:methanol (1:1), 10 mM ammonium acetate].

The lipid molecular species were measured using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode and positive/negative switching. The positive-ion mode detected lipid classes, such as sphingomyelin (SM), diacylglycerol (DAG), cholesterol ester (CE), ceramide (CER), dihydroceramide (DCER), hexosylceramide (HCER), lactosylceramide (LCER), and triacylglycerol (TAG). The negative-ion mode detected lipid classes, such as lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), phosphatidylcholine (PC), and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Samples were quantitated using the Lipidomics Workflow Manager (LWM) software accompanying the hardware. Lipid species concentrations were calculated using spiked isotope-labeled standards according to the formula: analyte intensity / standard intensity × spike standard concentration in samples. The differential analyses between the groups were performed in Limma v3.50.0 (Ritchie et al., 2015). Limma estimated the log2(fold change) and the standard error by a linear model including groups as variables for each lipid species. The inference procedure was adjusted by applying an empirical Bayes shrinkage. To test the two-sided null hypothesis of no changes in concentration, the model-based test statistics were compared with the Student’s t test distribution with degrees of freedom appropriate for each lipid species.

Behavioral assessments

All behavioral tests used mice that were naive to each behavioral assay, and the experimenters were blinded to the treatment group. Experiments were conducted during the light phase for the animals. Tests were performed during Weeks 15 and 16 of dosing with no more than one test occurring in a single day.

Locomotor activity

Mice were acclimated to the testing room in their home cages for at least 60 min prior to testing. Transparent thermoplastic cages [40.5 (W) × 40.5 (L) × 38 (H) cm, San Diego Instruments] fitted with infrared (IR) beams (3 cm above the floor) were used to record the horizontal beam break activity and rearing. A total of 15 min of locomotor activity beginning with the placement of the animals into the locomotor chambers was analyzed. Testing was conducted with bright lights on.

Y-maze

Mice were acclimated to the testing room in their home cages for at least 60 min prior to testing. The testing procedure was adapted from Redrobe et al. (2009) and Bristow et al. (2016) using a Y-maze made out of a gray thermoplastic material. The width and height of all arms were 10 and 29 cm, respectively. The length of the start arm was 20 cm, and that of each of the two remaining (nonstart) arms was 40 cm. All arms had removable doors that were positioned close to the center of the maze, 2.5 cm from the center-facing end of the respective arms. There were interchangeable thermoplastic inlays that covered the entire 10 × 30 cm headwall of the end of the nonstart arms. The inlays consisted either of five vertical black lines (1 cm wide) or five arrays of vertically aligned columns of black circles (1 cm wide) on a white background. The presence of the distinct inlays together with the relatively large height of the walls maximized the salience of intramaze cues while minimizing the salience of extramaze cues. The pattern of inlay and location of the familiar or novel arm (left vs right) was counterbalanced between mice. A two-trial procedure was used. During the first trial, the mouse was allowed to explore the start arm and one nonstart arm for 6 min. The mouse was then removed from the maze and placed in a holding cage while the maze was fully cleaned with ethanol wipes (∼3 min). During the second trial, the mouse was allowed to explore all arms for 3 min, including the previously closed arm (i.e., the “novel arm”) containing an inlay that was distinct from the one in the familiar arm. The movement of the mouse was tracked by a ceiling-mounted camera, and data were analyzed using the CleverSys software. The time spent and distance covered in the novel versus the familiar arm were quantified, and a percent preference score for the novel arm was calculated by normalizing the time or distance measures from the mouse in the novel arm by that from the novel plus the familiar arm.

Nest building

We have developed a two-part nest scoring system that measures nest quality and gathering of nesting materials. This system adapts Deacon's system (2006) and Roof's system (2010) for the paper roll nesting material included in the standard Enrich-o’Cob bedding used in-house. The experiment was conducted in the regular mouse holding room. Animals were singly housed in cages with water and food available ad libitum and standard bedding material. The nest quality was scored at 24 and 72 thereafter using a five-graded scale consisting of the following scores: (1) absence of any apparent nest with paper rolls randomly distributed across the cage floor; (2) a loosely packed, flat nest; (3) a close-packed, flat nest; (4) a close-packed, cratered nest with visible walls on approximately 50% of the perimeter of the nest; and (5) a close-packed, cratered nest entirely enclosed by visible walls.

Results

Unless otherwise specified, the experiments described in this work were conducted with Para.09 or a humanized variant, hPara.09, on antibody backbones with reduced effector function [Para.09 on murine IgG2a with LALAPG substitutions (Lo et al., 2017) and hPara.09 on a human IgG1 with the N297G substitution (Jacobsen et al., 2017)].

Primary human macrophage responses to hPara.09

To model TREM2 signaling in an accessible human cell type, the hPara.09 effects were studied in cultured human monocyte–derived macrophages (hMDMs). Fluorophore-conjugated hPara.09 bound to the surface of hMDMs (Fig. 1A), and application of hPara.09 elevated SYK phosphorylation levels, indicating the activation of downstream signaling with a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of 13 nM (Fig. 1B,C). To confirm SYK phosphorylation results from TREM2 activation, the TREM2 gene was disrupted by transfection of CRISPR ribonucleoprotein loaded with guide RNA targeting TREM2 (gTREM2). Relative to a nontargeting control guide RNA (NTC), CRISPR editing reduced hPara.09 surface staining (Fig. 1A) and eliminated SYK phosphorylation responses to hPara.09 (Fig. 1E). Consistent with the overlap of the hPara.09 epitope and the ADAM protease cleavage site (Hsiao et al., under review), hPara.09 greatly reduced sTREM2 shedding over 48 h with higher potency (IC50 = 1.7 nM) compared with the shorter-duration SYK phosphorylation assay (Fig. 1D). Responsiveness to hPara.09 was compared with another TREM2 agonist, phosphatidylserine-containing liposomes (PS liposomes). hPara.09 and PS liposomes each evoked comparable SYK phosphorylation and, in combination, produced greater responses than either ligand alone (Fig. 1F). All responses were largely abrogated by CRISPR-mediated TREM2 disruption (Fig. 1F); small remnant signals may result from low levels of nonedited cells. These results indicate that hPara.09 engages TREM2 in macrophages without competing with native ligands.

IPSC-derived microglia responses to hPara.09

Next, we tested hPara.09 activity against human IPSC–derived microglia (IPSC-MG). TREM2 signaling facilitates macrophage and microglia survival under stress, thereby enhancing microglial persistence at sites of pathology (Otero et al., 2009; Ulland et al., 2017). As such, we investigated whether hPara.09 augmented survival of IPSC-MG under low growth factor conditions. We tested responses to plate-bound antibody to facilitate clustering at cell contact points with the plate and maximize signaling responses. IPSC-MG rely on exogenous growth factors CSF-1 and/or IL-34, and reduced growth factor supplementation led to decreased IPSC-MG survival (Fig. 1G). Although hPara.09 did not alter cell counts in complete medium, plate-bound hPara.09 rescued the survival under growth factor restriction in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, IPSC-MG derived from TREM2 knock-out IPSCs exhibited greatly reduced responses to hPara.09 (Fig. 1H). Testing of other plate-bound antibodies recognizing microglia surface antigens other than TREM2 was also ineffective (Fig. 1K). Plate-bound hPara.09 elevated SYK phosphorylation at earlier time points (Fig. 1L) and enhanced survival in a separate parental IPSC line in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2I). Although soluble hPara.09 reduced sTREM2 release from IPSC-MG (IC50 = 0.69 nM) in a comparable manner as for hMDMs (Fig. 1J), soluble antibody application did not promote IPSC-MG survival (Fig. 1M). Proliferative responses to soluble antibodies were subsequently observed in vivo (see below), suggesting that the need for plate-bound stimulation in vitro may reflect altered TREM2 levels, TREM2 cellular distribution, or TREM2 pathway regulation in culture models.

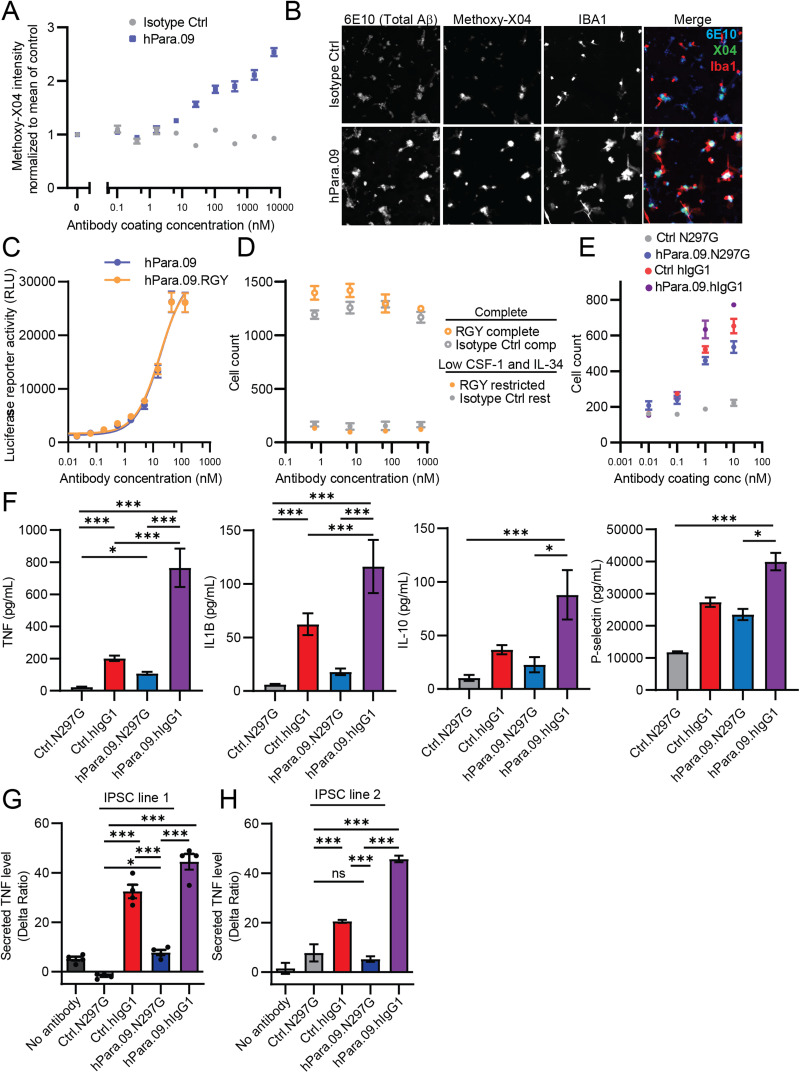

Figure 2.

In vitro plaque and cytokine activity of TREM2 agonist antibody hPara.09. A, IPSC-MG compaction of Aβ oligomers 48 h after plating onto antibody-coated plates in growth factor–restricted medium, quantified using methoxy-X04 staining intensity. Total methoxy-X04 intensity was normalized to a no antibody control. B, Representative images of IPSC-MG (Iba1) relationship with total Aβ (6E10 antibody stain) or compact Aβ (methoxy-X04 stain). C, Jurkat cell NFAT luciferase responses to soluble hPara.09 or hexamerization-promoting variant hPara.09.RGY. D, IPSC-MG survival 72 h after treatment with soluble antibody in complete medium (open circles) or growth factor–restricted medium (closed circles) comparing hPara.09.hIgG1.RGY (RGY) to gp120.hIgG1.RGY (Isotype Ctrl). E–G, IPSC-MG survival at 72 h (E), cytokine release into supernatants at 24 h measured by Luminex (F), or TNF release into supernatants at 24 h measured by HTRF assay (G) after addition to plates coated with full-effector (hIgG1) or reduced-effector (N297G) antibodies. H, IPSC-MG TNF release measured by HTRF assay from an independent IPSC line (WC30). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 one-way ANOVA with Tukey's test. Points represent mean ± SEM. Three to six technical replicates, representative of at least two independent experiments. The line in H indicates Hill equation fit with the slope fixed at 1.

TREM2 activity also leads to altered histological features of amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregates, resulting in axonal protection in plaque-burdened brain tissue and in culture models (Wang et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2016; Meilandt et al., 2020; Bassil et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021). To determine if cells surviving after hPara.09 treatment retain relevant functions, we added Aβ aggregates to IPSC-MG in a low growth factor medium. Coinciding with improved cell survival, hPara.09-treated cells dose-dependently exhibited elevated production of compacted methoxy-X04–positive amyloid structures relative to control cells (Fig. 2A,B).

To test whether increased hPara.09 valency could mimic plate-bound effects, we generated hPara.09 with a modified hIgG1 backbone containing RGY substitutions (Diebolder et al., 2014), leading to hexamerization of the antibody (from 100% monomer for hPara.09 to 41.1% monomer and 58.9% hexamer fit for hPara.09.RGY by size-exclusion chromatography). However, despite high hexamer content, soluble hPara.09.RGY did not enhance activity in reporter cell assays (Fig. 2C) or IPSC-MG survival assays (Fig. 2D), suggesting the hPara.09 juxtamembrane epitope may not be amenable to augmentation with higher valency complexes.

The experiments described above were performed with hPara.09 with a reduced-effector hIgG1.N297G backbone. We next compared hPara.09 TREM2 agonist responses to those elicited by Fcγ receptor stimulation in response to plate-bound antibody. hPara.09 facilitated microglial survival on both full-effector (hIgG1) and reduced-effector (hIgG1.N297G) backbones; in contrast, a control antibody that recognizes an irrelevant viral epitope promoted survival only with the full-effector hIgG1 backbone (Fig. 2E), suggesting that Fcγ receptor activation can elicit prosurvival responses to a similar degree as TREM2 activation. To monitor additional cellular responses, we measured cytokine release into the IPSC-MG culture supernatants in a complete growth medium using a cytokine panel. Several cytokines were elevated specifically in response to the full-effector backbone (hPara.09 or isotype control antibody), but not in response to reduced-effector hPara.09.N297G (Fig. 2F). To corroborate these findings, we measured TNF from two separate IPSC lines using an orthogonal homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) assay. After treatment with hPara.09.N297G, TNF levels were either unchanged or showed a small elevation, whereas plated on full-effector Ctrl.IgG1 or Para.09.IgG1 antibodies showed strong and superadditive elevation of TNF release (Fig. 2G,H). Thus, hPara.09.N297G can elicit prosurvival effects without stimulating the release of proinflammatory cytokines, which have potentially damaging roles in neurodegeneration (DiSabato et al., 2016).

Overall, we find that hPara.09 agonizes TREM2 independently of antibody effector function and facilitates TREM2-mediated microglial survival and disease-relevant interactions with amyloid aggregates.

Acute effects of single-dose Para.09 in hTREM2 mice

Para.09 binds to an epitope that is not conserved between mice and humans, so it is inactive against mouse TREM2 (Hsiao et al., under review). To enable experiments in rodent models, we introduced a single copy of the human TREM2 gene into a murine Trem2 knock-out PS2APP strain as part of a bacterial artificial chromosome (hTREM2 mice). Transcript expression was highly enriched in sorted microglia over sorted astrocytes or neurons (Fig. 3A,B), and histological assessment confirmed hTREM2 protein expression by microglia engaged with amyloid plaques (Fig. 3C). Brains of these mice exhibited human TREM2 transcript expression levels that closely matched murine Trem2 in PS2APP mice (Fig. 3D). A separate founder from the hTREM2 colony showed evidence of multiple integration events, resulting in unnaturally high transcript levels and human sTREM2 concentrations in plasma (Fig. 3D,E). Therefore, experiments were conducted in the single-copy line.

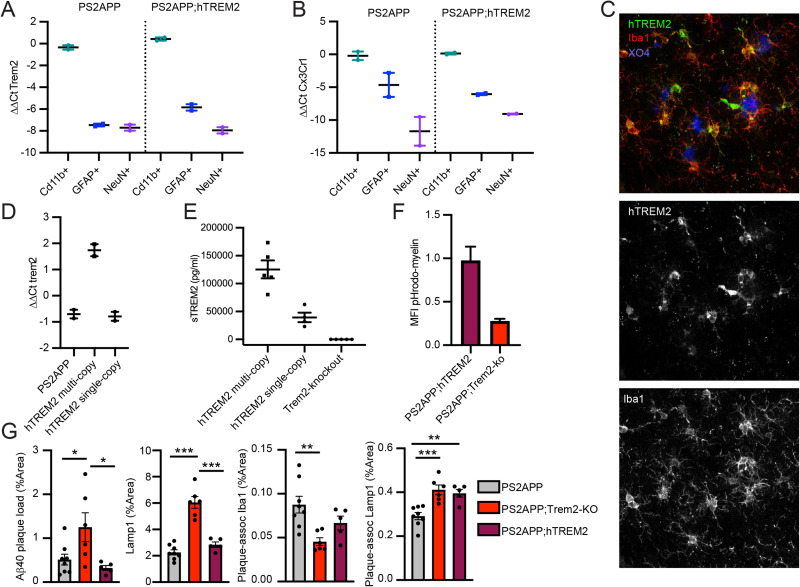

Figure 3.

Characterization of hTREM2 transgenic mice. A, RT-PCR quantification illustrates enrichment of mouse Trem2 (left) or human TREM2 (right) gene expression in Cd11b+ (microglia-enriched) over GFAP+ (astrocyte-enriched) or NeuN+ (neuron-enriched) FACS-sorted fixed cell fractions from PS2APP or PS2APP;hTREM2 mice. B, RT-PCR quantification of a separate microglial marker, Cx3cr1, illustrating relative enrichment across sorted populations. C, Staining of human TREM2 (green) colocalizes with plaque (methoxy-X04)-associated microglia (Iba1; cortex). D, RT-PCR quantification of murine Trem2 or human TREM2 expression in single-copy versus multicopy PS2APP (4–5 months old) BAC transgenic mouse lines from Cd11b+ (microglia) FACS-sorted live cell fraction. Single-copy hTREM2 mice approximate normal mouse TREM2 expression. E, ELISA quantification of plasma sTREM2 illustrating levels in TREM2 knock-out mice and single versus multicopy PS2APP;hTREM2 transgenic lines. F, Phagocytosis assay using primary microglia from PS2APP;hTREM2 mice shows elevated phagocytosis of pHrodo-labeled myelin relative to cells from PS2APP;Trem2 knock-out mice. G, Quantification of percentage area coverage from histological stains across coronal brain sections or within a 15 µm region dilated around the plaque. Plaque load (Aβ40), neuritic dystrophy (Lamp1), plaque-associated microglia (Iba1), or plaque-associated neuritic dystrophy (Lamp1) all show changes with Trem2 knock-out and partial rescue by the introduction of the hTREM2 transgene. Bars represent mean ± SEM; points are individual animals. One-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey's test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We next tested the functional replacement of murine Trem2 in PS2APP;hTREM2 mice. In vitro, primary microglia cultured from hTREM2 mice showed elevated myelin phagocytosis relative to Trem2-KO, indicating at least partial replacement of murine Trem2 (Fig. 3F). In PS2APP mice, hTREM2 incorporation fully rescued plaque load and neuritic dystrophy abnormalities of Trem2-KO mice and partially rescued microglia association with plaques measured by plaque-associated Iba1 staining (Fig. 3G).

Having established at least partial functionality of hTREM2 in transgenic mice, we conducted single-dose experiments to determine a dose–response relationship in vivo. To isolate the effects of TREM2 agonism, a reduced-effector function antibody backbone, Para.09.mIgG2a.LALAPG, was tested. A single Para.09 injection into hTREM2 lacking pathology or PS2APP;hTREM2 mice resulted in dose-dependent antibody brain exposure that is consistent with typical antibody distribution (Shah and Betts, 2013; Fig. 4A,E). All antibody doses produced 75–85% sTREM2 reduction in plasma, and a significant reduction of sTREM2 in the brain was observed for higher dose levels (Fig. 4A,E). sTREM2 plasma and brain measurements were not affected by excess Para.09 incubation ex vivo, indicating that Para.09 does not interfere with our sTREM2 detection assays (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that doses at or above 100 mg/kg exhibit clear target engagement in the brain.

We next performed bulk brain RNA-seq analysis of dosed PS2APP;hTREM2 mice to broadly assess responses 3 d after Para.09 dosing. Consistent with other reports on TREM2 agonist antibodies (Wang et al., 2020b; Ellwanger et al., 2021; van Lengerich et al., 2023), we found induction of a proliferation signature (Fig. 4B). To corroborate the proliferation responses observed transcriptionally, we performed Ki67/Iba1 colabeling. Consistent with sTREM2 changes, doses at 100 mg/kg or higher elicited microglial proliferation in the cortex (Fig. 4C). We confirmed this effect in pathology-free hTREM2 mice using a more sensitive EdU measurement and confirmed responsiveness in a similar dose range (Fig. 4E). However, the proliferation response was transient and resolved within 7 d after dosing (Fig. 4C), despite sustained sTREM2 reduction at Day 7 (Fig. 4A). Proliferation responses were also observed with a related TREM2 agonist antibody, 3.10C2, and these responses were absent from mice lacking the hTREM2 transgene (Fig. 4F,G). These results define a dose–response relationship for Para.09 in vivo and indicate that microglial responses are detected when brain sTREM2 is reduced by ≥50%.

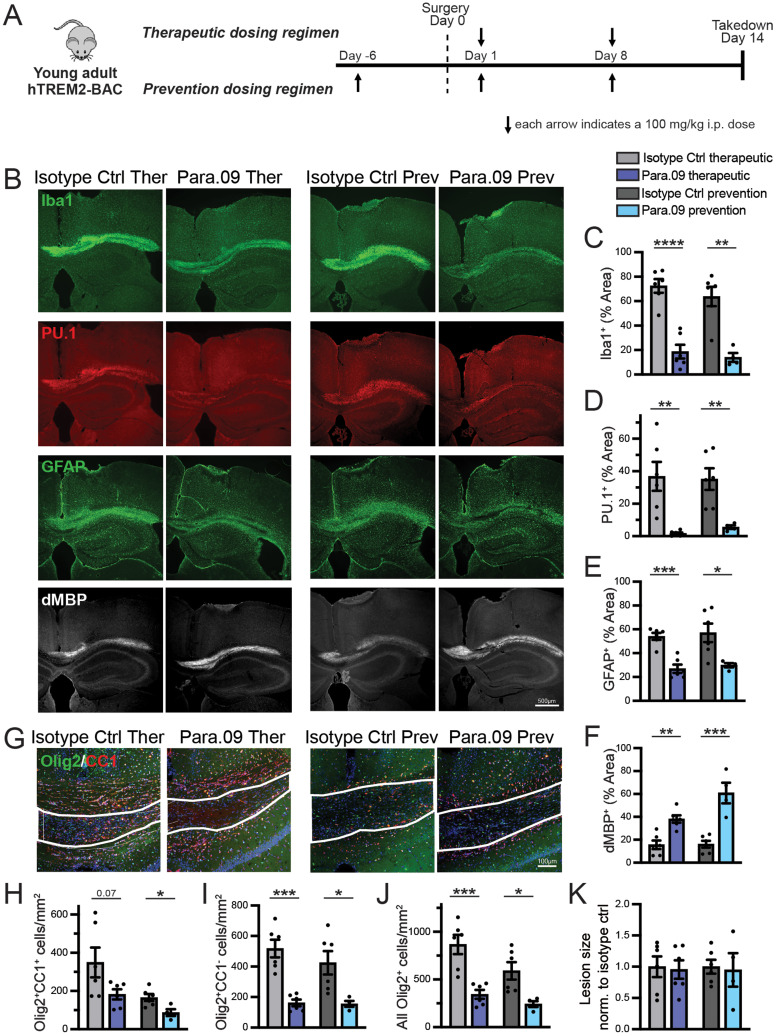

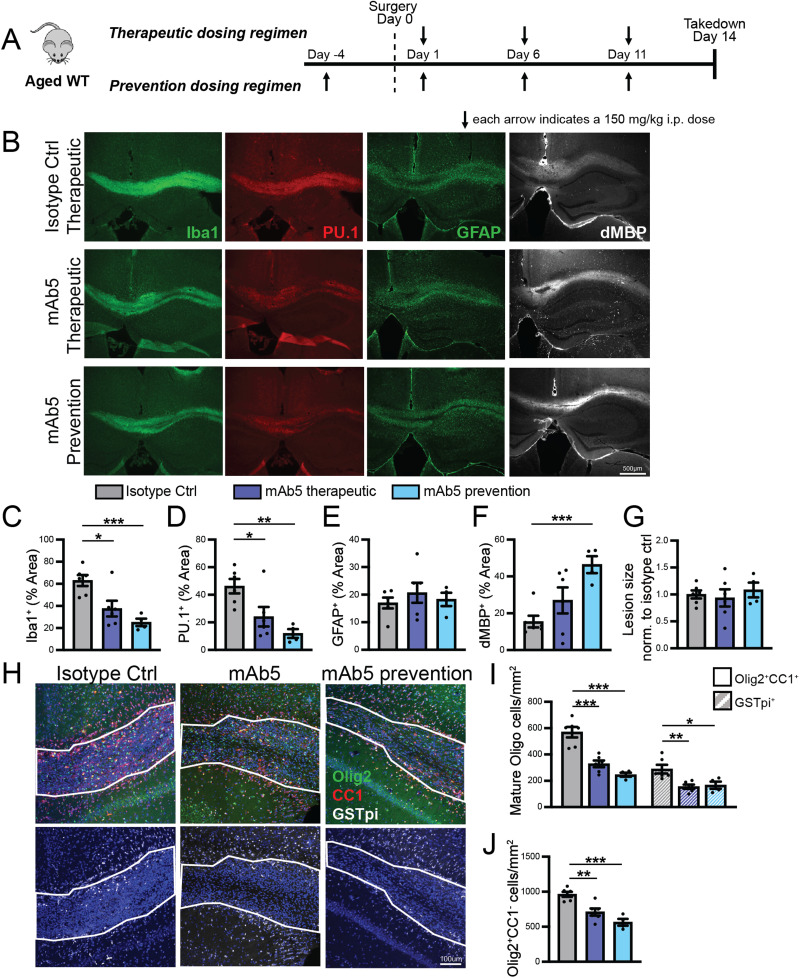

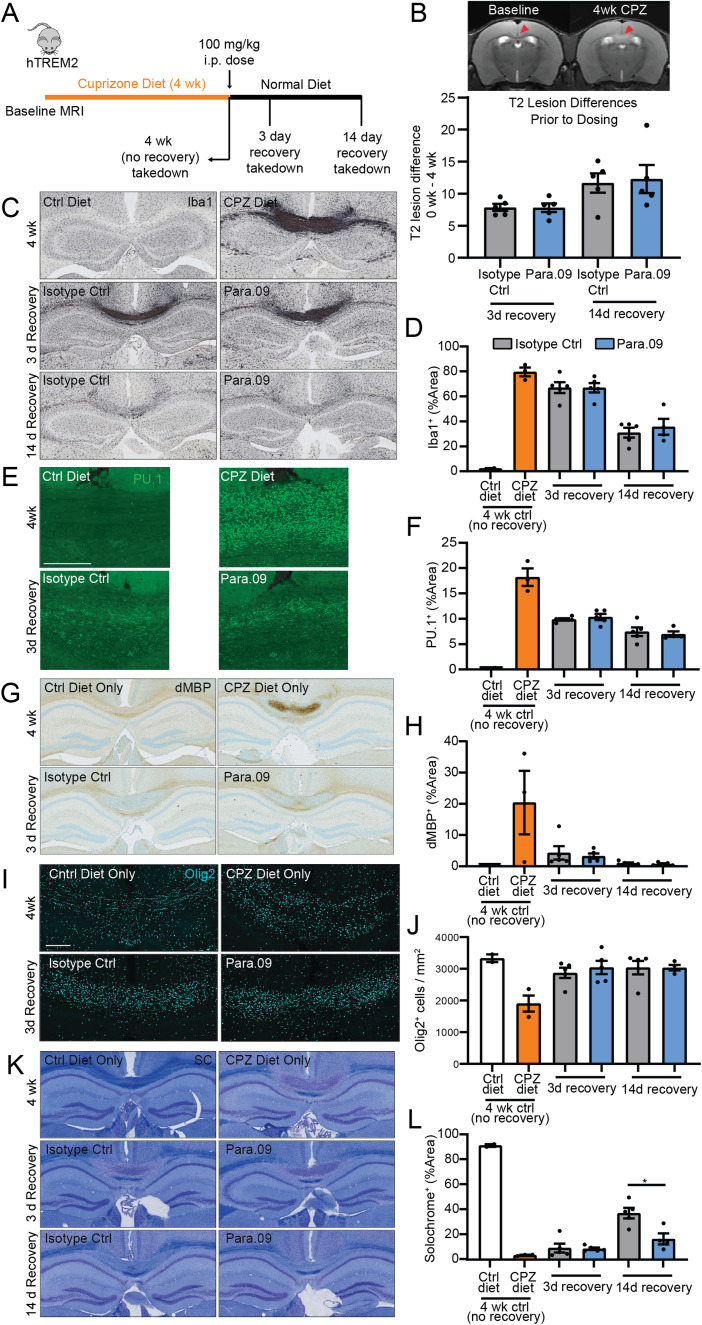

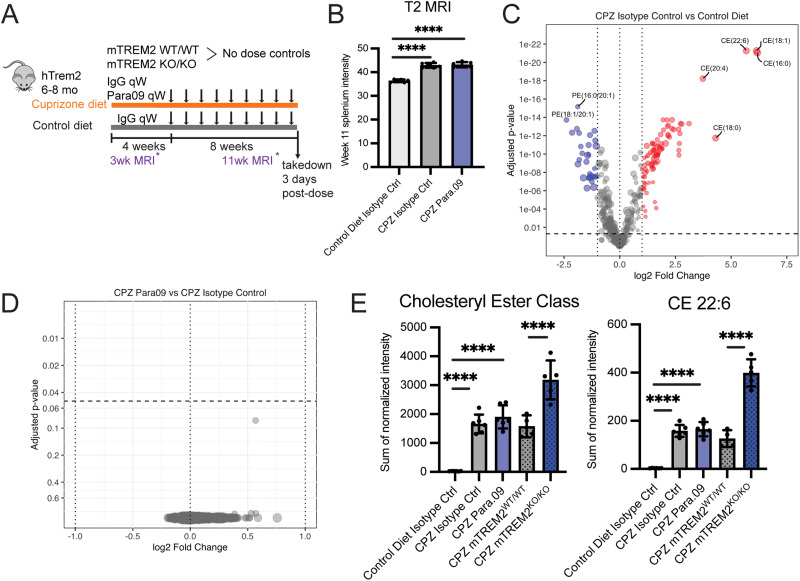

To further investigate the functional consequences of TREM2 agonism by Para.09, microglia near plaques were imaged at high resolution. Three-dimensional volume renderings found that microglia near amyloid-β plaques had elevated amyloid-β colabeling, suggesting potential heightened interactions between microglia and plaques after a single antibody dose (Fig. 4D). These findings identify an active dose range for mouse studies (100–200 mg/kg) that elicits soluble TREM2 reduction, TREM2-dependent microglial proliferation, and altered microglia–plaque interactions.