Abstract

Background

The incidental finding of a pericardial effusion (PE) poses a challenge in clinical care. PE is associated with malignant conditions or severe cardiac disease but may also be observed in healthy individuals. This study explored the prevalence, determinants, course, and prognostic relevance of PE in a population‐based cohort.

Methods and Results

The STAAB (Characteristics and Course of Heart Failure Stages A/B and Determinants of Progression) cohort study recruited a representative sample of the population of Würzburg, aged 30 to 79 years. Participants underwent quality‐controlled transthoracic echocardiography including the dedicated evaluation of the pericardial space. Of 4965 individuals included at baseline (mean age, 55±12 years; 52% women), 134 (2.7%) exhibited an incidentally diagnosed PE (median diameter, 2.7 mm; quartiles, 2.0–4.1 mm). In multivariable logistic regression, lower body mass index and higher NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide) levels were associated with PE at baseline, whereas inflammation, malignancy, and rheumatoid disease were not. Among the 3901 participants attending the follow‐up examination after a median time of 34 (30–41) months, PE was found in 60 individuals (1.5%; n=18 new PE, n=42 persistent PE). Within the follow‐up period, 37 participants died and 93 participants reported a newly diagnosed malignancy. The presence of PE did not predict all‐cause death or the development of new malignancy.

Conclusions

Incidental PE was detected in about 3% of individuals, with the vast majority measuring <10 mm and completely resolving. PE was not associated with inflammation markers, death, incident heart failure, or malignancy. Our findings corroborate the view of current guidelines that a small PE in asymptomatic individuals can be considered an innocent phenomenon and does not require extensive short‐term monitoring.

Keywords: incidental finding, pericardial effusion, population‐based cohort, prognostic relevance

Subject Categories: Pericardial Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ESC

European Society of Cardiology

- PE

pericardial effusion

- STAAB

Characteristics and Course of Heart Failure Stages A/B and Determinants of Progression

- TTE

transthoracic echocardiography

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

A small and asymptomatic pericardial effusion was detected in nearly 3% of participants from a population‐based sample free from heart failure.

Over the course of a median of 34 months, pericardial effusion was not associated with death, incident heart failure or malignancy, or inflammation.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our data provide reassuring evidence that a small, asymptomatic pericardial effusion coincidentally detected in an individual from the general population is not an unfavorable sign.

Consequently, our results support a more conservative approach to the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of such individuals, particularly when encountering incidental findings.

Pericardial effusion (PE) is defined as an accumulation of fluid within the pericardial cavity. 1 Virtually any process that affects the pericardium can lead to an effusion. 1 , 2 PE often occurs as an epiphenomenon in patients with pericardial, malignant, or inflammatory disease. 3 However, PE can also occur in healthy individuals. 4 Most PEs are not hemodynamically relevant and remain asymptomatic. 5 The incidental finding of PE, hence, challenges the treating physicians as they have to deal with the dilemma of ordering advanced diagnostics to avoid missing a potentially relevant diagnosis but also with uncertainty and discomfort for the patient, as well as additional costs for the health care system. 6

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American Society of Echocardiography guidelines recommend 2‐dimensional transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) as the reference imaging modality for any suspected pericardial disease or effusion (Class of Level of Evidence, lC). 1 , 7 TTE is a cost‐effective, widely available, and safe method that allows for a comprehensive assessment of the size, location, and hemodynamic relevance of PE. 1 , 7 , 8 In TTE, PE appears as an echo‐free space between the 2 layers of the pericardium that persists throughout the cardiac cycle. 6 It can be classified on the basis of various factors, including size, distribution, composition, hemodynamic impact, and time of onset. The size of PE can be categorized semiquantitatively by echocardiography into small (<10 mm), moderate (10–20 mm), or large (>20 mm). 1 , 6 , 7 Clinically, the spectrum ranges from small asymptomatic PE to life‐threatening emergencies (eg, cardiac tamponade). 6

To date, 2 primary pathophysiological mechanisms have been identified that are responsible for the accumulation of pericardial fluid: fluid exudation resulting from pericardial inflammation and transudation caused by hemodynamic abnormalities or reduced osmotic pressure (eg, in congestive heart failure or pulmonary hypertension). 1 , 3 , 8

Data regarding the prevalence and relevance of PE in the general population are scarce, and recommendations how to deal with an incidentally identified PE are based on expert opinion. 9 To enhance evidence in this field, the current study aimed to determine the prevalence, investigate the determinants, explore the clinical course, and assess the prognostic yield of PE in a population‐based cohort.

Methods

Population

The STAAB (Characteristics and Course of Heart Failure Stages A/B and Determinants of Progression) cohort study aimed to recruit and comprehensively characterize a representative sample of the general population of the City of Würzburg, aged 30 to 79 years, stratified by age decade and sex, with no medical history of heart failure (HF) at the time of enrollment. 10 , 11 , 12 The STAAB study investigates the prevalence and course of the precursor stages of HF. 10 , 11 Its detailed study design has been previously published. 10 The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Würzburg (vote 98/13), as well as by the data protection officer (J‐117.605‐09/13), and is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before undergoing the study examinations. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Baseline and Follow‐Up Examination

Study visits were conducted at the Joint Survey Unit run by the Comprehensive Heart Failure Center and the Institute of Clinical Epidemiology and Biometry. Participants were comprehensively phenotyped, including medical history, current medical treatment, and physical examination performed by a study physician. Anthropometric measurements and vital signs were obtained by trained staff according to standard operating procedures. 10 , 13 Laboratory analyses were performed at the Central Laboratory of the University Hospital Würzburg. NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide) and high‐sensitivity cardiac troponin I were measured from stored serum samples (Cobas E411/Cobas Integra Roche). 11

Echocardiography, Quality Assurance, and Assessment of Pericardial Effusion

All patients underwent standardized transthoracic echocardiography using Vivid S6 (M4S Sector Array Transducer operating at 1.5 to 4.3 MHz; GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway) and a Vivid E95 (M5Sc‐D Transducer operating at 1.5–4.6 MHz; GE Healthcare) ultrasound scanner. Three cardiac cycles were recorded and digitally stored. Image acquisition was performed by trained and certified sonographers following a consistent set of predefined images including a dedicated evaluation of the presence or absence of PE. 10 Quality assurance measures regarding image acquisition and interpretation have been published previously. 13 The dimensions and function of the cardiac chambers were measured according to current guidelines. 14

The presence or absence of PE was assessed using the subcostal view. Participants were in a supine position and asked to take a deep breath and hold it, thus bringing the heart closer to the probe. 15 , 16 , 17 The image was optimized in width and depth to visualize the entire heart and vicinity. We focused on the space between the right heart and the liver, ensuring avoidance of overestimation of a potential PE by misangulation of the probe. PE was defined as an echo‐free space located between the pericardium and epicardium that was present throughout the cardiac cycle. The diagnosis of epicardial fat (and not PE) was based on the finding of an inhomogeneous appearance of the pericardial space featuring higher echogenicity and sparkled texture, 17 shifting in synchrony with the heart during the cardiac cycle. 1 , 7 , 8 , 18

PE was assessed from stored images by 2 experienced sonographers from the Academic Core Lab Ultrasound‐Based Cardiovascular Imaging (M.B. and C.H.) blinded to any clinical information. PE size was determined in an end‐diastolic frame just apical of the level of the tricuspid valve. In accordance with the guidelines of the ESC and American Society of Echocardiography, 1 , 7 we classified PE as small (<10 mm), moderate (10–20 mm), and large (>20 mm).

Assessment of Outcomes

The confirmation of end points, including death from any cause, relied on information from the municipal registry of the city of Würzburg. New‐onset HF was verified through the adjudication of discharge letters obtained from hospitals or cardiologists, with 2 cardiologists reviewing and consenting to the information using the Framingham criteria. 19 Occurrence of incident malignancy was assessed using questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and presented as frequency (percentage), mean (SD), or median (quartile), as appropriate. Groups were compared using the χ2 test, t test, or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Determinants for the presence of PE were sought using logistic regression with PE as the binary dependent variable. Variables demonstrating P<0.05 in univariable regression were subsequently included in a multivariable model. NT‐proBNP was transformed using the natural logarithm before entering the model. The association of PE with outcomes (death of any cause, new‐onset HF) or incident malignancy was explored using Cox proportional hazards regression or logistic regression, as appropriate, and hazard ratios or odds ratios with 95% CIs were reported.

Results

Baseline Assessment

For the present analysis, we assessed data from 4965 participants who had been consecutively enrolled in the STAAB study between December 2013 and October 2017 (Tables 1 and 2). Their mean age was 55±12 years, and 52% were women. PE was detected in 134 individuals (2.7%), with a mean age of 54±11 years, of whom 66% were women. The median size of PE was 2.7 (quartiles 2.0–4.1) mm, and the maximum size was 12.5 mm. Individuals with PE were asymptomatic, and in 99% of those, the effusion was classified as small, while only 1 female participant (0.7%) exhibited a moderate PE (12.5 mm). When compared with individuals without PE, those with PE had a lower body mass index (BMI), higher levels of NT‐proBNP (Table 1), and a higher prevalence of hypertension, while the prevalence of other comorbidities, including rheumatoid disease, malignancy, and atherosclerotic disease, was similar (Table 1). There were also no significant differences between groups in terms of age, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein level, leukocyte count, high‐sensitivity troponin I level, and kidney function (Table 1). Furthermore, echocardiographic parameters of systolic and diastolic function, such as left ventricular ejection fraction, global longitudinal strain, and E/e′, were similar between the groups, with minor differences observed in left ventricular size and wall thickness (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of STAAB Participants With and Without PE

| Total sample (n=4965) | Participants with PE (n=134) | Participants without PE (n=4831) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 55±12 | 54±11 | 55±12 |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 2604 (52) | 88 (66) | 2516 (52) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27±5 | 24±4 | 27±5 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 68±11 | 67±9 | 68±11 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 131±18 | 126±16 | 131±18 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 78±12 | 76±10 | 78±12 |

| High sensitivity C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) | 0.8 (0.5, 2.2) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) |

| Leukocyte count, 109/L | 6.0±3.7 | 5.8±1.9 | 6.0±3.7 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.3±1.3 | 4.8±1.3 | 5.3±1.3 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.0±1.2 | 13.7±1.1 | 14.0±1.2 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 121±35 | 122±34 | 121±35 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.732 | 86±18 | 85±14 | 86±18 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.89±0.18 | 0.86±0.15 | 0.89±0.18 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.6±0.3 | 4.6±0.3 | 4.6±0.3 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.5±0.6 | 5. 4±0.6 | 5.5±0.6 |

| High sensitivity troponin I, pg/mL | 2.3 (1.5, 3.7) | 2.2 (1.5, 3.6) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.8) |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 67 (36, 115) | 80 (48, 119) | 66 (36, 115) |

| NT‐proBNP ≥125 pg/mL, n (%) | 1075 (22) | 31 (23) | 1044 (22) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2295 (46) | 44 (33) | 2251 (47) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 461 (9.3) | 6 (4) | 455 (9) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 94 (2) | … | 94 (2) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 195 (4) | 1 (1) | 194 (4) |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 80 (2) | 2 (1) | 78 (2) |

| Rheumatologic disease, n (%) | 181 (4) | 3 (2) | 178 (4) |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 445 (9) | 9 (7) | 436 (9) |

| COPD, n (%) | 160 (3) | 5 (4) | 155 (3) |

| Antihypertensive treatment, n (%) | 1481 (30) | 25 (19) | 1456 (30) |

| ACEi or AT1, n (%) | 1103 (23) | 20 (15) | 1083 (23) |

| β Blocker | 677 (14) | 11 (8) | 666 (14) |

| Antidiabetic treatment | 238 (5) | 4 (3) | 234 (5) |

| Lipid‐lowering treatment | 475 (10) | 8 (6) | 467 (10) |

Data are n (%), mean±SD, median (quartiles). ACEi indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; AT1, angiotensin II receptor type 1; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PE, pericardial effusion; and STAAB, Characteristics and Course of Heart Failure Stages A/B and Determinants of Progression.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic Characteristics of STAAB Individuals With and Without PE (at Baseline)

| Total sample (n=4965) | Participants with PE (n=134) | Participants without PE (n=4831) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVSd, mm | 9±2 | 8±1 | 9±2 |

| LVPWd, mm | 8±1 | 7±1 | 8±1 |

| LVEDD, mm | 48±5 | 48±4 | 49±5 |

| TAPSE, mm | 25±4 | 25±3 | 25±4 |

| sPAP, mm Hg, n=3182 | 24±6 | 25±6 | 24±6 |

| E/e′ | 7.7±2.7 | 7.6±2.2 | 7.7±2.8 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 23±7 | 22±6 | 23±7 |

| LVEDVi, mL/m2 | 53±12 | 51±10 | 53±12 |

| LVMi, g/m2 | 73±18 | 69±13 | 73±18 |

| LVEF, % | 60±5 | 60±5 | 60±5 |

| GLS, −%,* n=1929 | 21±3 | 21±2 | 21±3 |

Data are mean±SD. GLS indicates global longitudinal strain, IVSd, interventricular septum diameter measured at end‐diastole; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEDD, left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter; LVEDVi, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; LVPWd, left ventricular posterior wall diameter measured at end‐diastole; PE, pericardial effusion; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; STAAB, Characteristics and Course of Heart Failure Stages A/B and Determinants of Progression; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Was measured only in the first interim analysis.

In univariable logistic regression analysis considering the baseline characteristics, the following factors predicted the presence of PE (ordered by decreasing strength of association): sex, BMI, NT‐proBNP, and hypertension (Table 3). When these variables were included in a multivariable regression model, only BMI and NT‐proBNP remained as independent predictors for the presence of PE (Table 3).

Table 3.

Determinants of PE in the General Population (at Baseline)

| Variable | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, per 5‐y increment | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) | 0.835 | … | |

| Female sex | 1.77 (1.23–2.53) | 0.002 | … | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.87 (0.83–0.91) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.85–0.93) | <0.001 |

| High‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 0.03 (0.95–1.04) | 0.714 | … | |

| Natural log transformed NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 1.25 (1.05–1.50) | 0.015 | 1.27 (1.03–1.56) | 0.024 |

| High‐sensitivity troponin I, pg/mL | 0.98 (0.95–1.03) | 0.430 | … | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.42 (0.15–1.21) | 0.107 | … | |

| Hypertension, yes vs no | 0.56 (0.39–0.81) | 0.002 | … | |

| Diabetes, yes vs no | 0.45 (0.19–1.03) | 0.058 | … | |

| Malignancy, yes vs no | 0.73 (0.37–1.44) | 0.356 | … | |

| Rheumatoid disease, yes vs no | 0.60 (0.19–1.90) | 0.385 | … | |

Logistic regression analysis with pericardial effusion as the binary dependent variable. Variables demonstrating P<0.05 in univariable regression were subsequently included in a multivariable model. PE indicates pericardial effusion; and NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Follow‐Up Examination

The follow‐up examination was performed between December 2017 and August 2021 and included a COVID‐19–induced break. The median time between baseline examination and follow‐up was 34 months (quartiles, 30–41). A total of 3901 participants, that is, 79% of the initial cohort, responded positively, provided informed consent, and could be included in the follow‐up analysis (Table 4). The mean age of the follow‐up sample was 58 (11) years, and 52% were women.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Individuals With Persistent Versus Nonpersistent Versus Incident PE at the Follow‐Up Examination

| Total sample (n=3901) | Participants with PE (n=60) | Participants without PE (n=3841) | Participants with persistent PE (n=42) | Participants with incident PE (n=18) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 58±11 | 57±11 | 58±11 | 57±11 | 56±11 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 2032 (52) | 42 (68) | 1991 (52) | 27 (64) | 14 (78) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27±5 | 24±5 | 27±5 | 23±4 | 24±5 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 65±10 | 64±10 | 65±10 | 65±10 | 62±8 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 128±17 | 123±15 | 128±17 | 124±16 | 121±15 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 76±10 | 74±10 | 76±10 | 75±10 | 72±9 |

| High‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 0.9 (0.4–2.4) | 1.1 (0.4–3.5) |

| Leukocyte count, 109/L | 6.2±2.8 | 6.0±1.8 | 6.2±2.8 | 6.0±1.6 | 5.9±2.2 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14±1 | 14±1 | 14±1 | 14±1 | 14±1 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 117±34 | 117±31 | 117±34 | 118±32 | 116±32 |

| eGFR, mL/min/ 1.73 m2 | 81±15 | 81±15 | 81±15 | 81±15 | 81±13 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.92±0.23 | 0.89±0.13 | 0.92±0.23 | 0.89±0.14 | 0.87±0.10 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.6±0.3 | 4.5±0.2 | 4.6±0.4 | 4.5±0.3 | 4.5±0.2 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.5±0.6 | 5.5±0.4 | 5.6±0.6 | 5.5±0.4 | 5.5±0.5 |

| High‐sensitivity troponin I, pg/mL | 6 (5–9) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–9) | 6 (5–9) | 6 (5–8) |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 64 (36, 112) | 72 (44, 115) | 63 (36, 112) | 79 (45, 120) | 55 (33, 103) |

| TAPSE, mm | 24±4 | 24±3 | 24±4 | 24±3 | 24±3 |

| E/e′ | 7.8±2.3 | 7.8±2.5 | 7.8±3.3 | 7.7±2.6 | 8.1±2.3 |

| LVEDVi, mL/m2 | 48±10 | 49±10 | 48±10 | 51±9 | 44±8 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 74±18 | 70±20 | 74±18 | 73±20 | 63±19 |

| LVEF, % | 59±5 | 61±6 | 59±5 | 62±5 | 59±6 |

| GLS, −% | 18.8±3.6 | 19.8±3.0 | 18.8±3.6 | 19.9±3.0 | 19.3±3.2 |

Data are n (%), mean±SD, or median (quartiles). BMI indicates body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVEDVi, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PE, pericardial effusion; SBP, systolic blood pressure; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

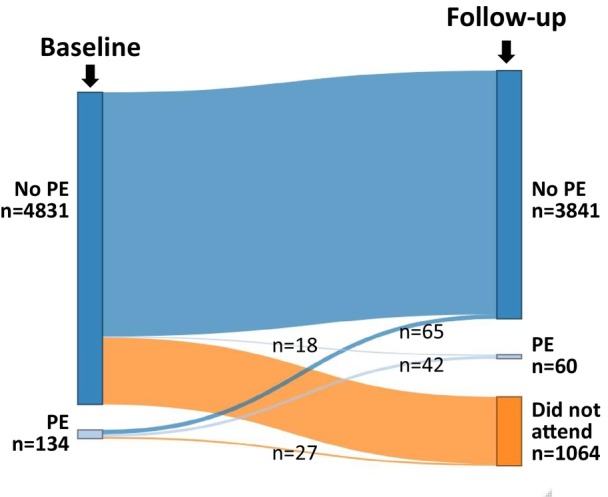

Among the 134 individuals with PE at baseline, 27 (20%) did not attend the follow‐up. There were no significant differences in age, sex, and BMI between those who attended the follow‐up and those who did not. Among the remaining individuals (n=107), 65 (61%) experienced a resolution of PE at the repeat echocardiography done at follow‐up, whereas 42 (39%) had a persistent PE (Figure).

Figure 1. The course of PE during a median follow‐up of 34 months. PE indicates pericardial effusion.

At follow‐up, a total of 60 individuals (2% of the follow‐up sample) exhibited PE: 42 participants with persistent PE and 18 with new PE. The median size of PE was 2.8 mm (1.8–4.1) and the maximum size measured was 14.5 mm (with only 2 female participants showing a moderate PE). The demographic, laboratory, and echocardiographic characteristics of the study population at follow‐up as the respective characteristics of individuals with PE both at baseline and follow‐up are provided in Table 4. In univariable logistic regression, significant factors associated with the presence of incident PE were female sex, BMI, and systolic blood pressure or hypertension (Table 5). Subsequently, these variables were included in a multivariable regression model, where BMI remained as the sole independent predictor of PE detected at follow‐up.

Table 5.

Determinants of PE in the General Population (at 3‐Year Follow‐Up)

| Variable | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, 5‐y increment | 0.95 (0.85–1.06) | 0.381 | … | |

| Female sex | 2.00 (1.16–3.47) | 0.013 | … | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.83 (0.78–0.90) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) | <0.001 |

| High‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, mg/L | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 0.521 | … | |

| Natural log transformed NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 1.13 (0.86–1.49) | 0.392 | … | |

| High‐sensitivity troponin I, pg/mL | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | 0.135 | … | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.36 (0.08–1.70) | 0.196 | … | |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.018 | … | |

Logistic regression analysis (for detailed description of the methods see Table 3). CI indicates confidence interval; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; and PE, pericardial effusion.

Prognostic Yield of PE

Within the follow‐up period, 37 participants died, corresponding to a death rate of 0.94%. Because only 1 of those 37 participants had exhibited PE at baseline. PE at baseline was not predictive of all‐cause death. Furthermore, 93 participants developed a newly diagnosed malignancy, corresponding to 2.4%. In univariable logistic regression, PE at baseline was not predictive of the development of new malignancy (odds ratio, 0.789 [95% CI, 0.192–3.238]; P=0.742).

Further, 6 participants developed symptomatic HF in the follow‐up period. However, none of these participants had exhibited PE at baseline.

Discussion

The current analysis was based on a carefully phenotyped population‐based sample stratified for age and sex. The following key findings emerged: (1) PE was observed in almost 3% of participants but resolved in 61% of participants during the follow‐up period; (2) the presence of PE was associated with lower values of BMI and higher values for NT‐proBNP but not with markers of inflammation, atherosclerotic disease, or parameters of systolic and diastolic left ventricular function; and (3) PE at baseline did not predict death, incident symptomatic HF, or incident malignancy. Our results thus support the view expressed in current guidelines that the incidental finding of a small PE in asymptomatic individuals can be considered an innocent phenomenon and does not require more intensive short‐term monitoring.

Prevalence and Determinants

Current guidelines on pericardial disease 1 still lack precise estimates of PE prevalence in the general population. In 1983, the Framingham population‐based study reported a prevalence of 6.5% for PE defined by a posterior extra echocardiographic space. 4 This study also found that the incidence of PE increased with age, reaching a plateau in 15% of patients aged ≥80 years. 4

In patients, the prevalence of PE is markedly higher and known to depend on the characteristics of the clinical presentation, etiology, acuity, dynamics, and the setting where PE is diagnosed. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 In the emergency department, for example, the prevalence of PE was reported to be up to 40%. 20 , 21 A meta‐analysis including >17 000 patients with various diseases reported a pooled PE prevalence of 19.5%. Another study from Veterans Affairs hospitals in the United States that included >10 000 consecutive in‐ and outpatients referred for echocardiography (95% men) reported the presence of a small PE in 5.7%. 25 There, patients referred for the evaluation of pericardial disease or after cardiac surgery had been excluded. In an Italian referral center for pericardial diseases, the mean annual prevalence of PE observed in the echocardiography laboratory ranged between 3% and 9% during 6 consecutive years. 6 We carefully investigated a representative sample of the general population and found a consistent prevalence of PE of 2% to 3% both at baseline and at follow‐up. Of note, the vast majority of individuals (99%) exhibited a small PE.

The prevalence of PE in our cohort not only was lower than the prevalence reported from patient samples but also lower than in the Framingham study population. There, a less specific category labeled “posterior extrapericardial space” was reported, which likely included both pericardial fat and fluid. 4 Today, the significant advancements in imaging methodology allows for better differentiation between pericardial structures, which likely contributed to the lower prevalence found in our study. Additionally, potential variations in PE prevalence by region of origin could contribute to the observed differences. 16 In developing countries, PE is commonly associated with tuberculosis, while viral infections and complications following surgery or medical interventions are more frequently observed in high‐income countries. 1 , 7 , 26 In most cases, PE lacks a definitive cause and is termed idiopathic (up to 50% of all cases), with small‐sized effusions generally considered benign. 1 , 6 , 7 An evidence‐based approach on how to manage these cases is lacking. 6 , 27

There are only a few studies investigating risk factors associated with PE in the general population. In our study, similar to the Framingham study, we observed a higher occurrence of PE among women and a lower prevalence of hypertension in individuals with PE. 4 Although PE was more prevalent in women and sex had a significant effect in univariate analysis, associations vanished after adjusting for other factors in a multivariable regression model. This observation may be linked to the association of sex with BMI.

Recruitment into our study was based on strict age and sex stratification to ensure an even distribution of both sexes into the 5 age decades between 30 and 79 years. Nonetheless, unlike the Framingham study, we did not detect any relation of PE prevalence with age, either in the total population with PE or in the respective groups with persistent or incident PE (Table 4). Additionally, we did not observe relevant associations between the presence of PE and parameters related to inflammation, malignancy, atherosclerotic disease, or systolic and diastolic left ventricular function. Likewise, we did not identify any disparities in glycated hemoglobin or cholesterol levels between individuals with and without PE, respectively. However, we identified an inverse association of PE with BMI. Further, individuals with PE exhibited higher levels of NT‐proBNP, suggesting potential myocardial involvement and increased stress for the left ventricle. However, the exact underlying mechanism related to the occurrence of pericardial effusion in participants with lower BMI remains still unclear.

Time Course, Prognostic Utility, and Clinical Considerations

The current ESC and American Society of Echocardiography recommendations regarding the course of PE are based on small study numbers and expert opinion. 9 As the course and prognosis of PE depend on the underlying cause, the relevance of PE in idiopathic PE or chronic asymptomatic PE is particularly difficult to assess. 28 No calculators or scoring systems are available assisting in the prediction of the time course or outcome of PE. Current guidelines recommend monitoring of PE on the basis of its echocardiographic extent and clinical presentation. 1 , 7 , 25 For patients with moderate to large effusion (ie, exceeding 10 mm), studies reported a very wide range of prognostic outcomes, largely dependent on the underlying cause of PE. 25 , 29 Moderate to large effusions are thought to carry a higher likelihood of deterioration compared with small PE (ESC guideline). 7 Therefore, the guidelines stress the importance of follow‐up assessments at 3‐ to 6‐month intervals. In addition, guidelines emphasize the strong influence of the pathogenetic factors on the prognosis of PE. 1 Biomarkers such as C‐reactive protein, troponin, or NT‐proBNP may offer insights into the progression of PE in individual cases. 6 , 25 One study in patients referred for echocardiography, including patients hospitalized for HF, explored the course of PE over a mean follow‐up period of 1.5 years. 25 There, ≈64% of patients with PE experienced spontaneous resolution, while 30% showed no change, and only 6% exhibited progression, although not resulting in large PEs or lethal complications. 25

In addition to etiology, guidelines emphasize the correlation between the size of PE and prognosis. 1 Typically, small idiopathic PEs are associated with a favorable prognosis, and current guidelines from ESC and American Society of Echocardiography do not mandate specific monitoring in such cases. 1 , 5 , 7 However, a large study including consecutive patients referred for echocardiography demonstrated that even small, asymptomatic PEs, when compared with age‐ and sex‐matched controls, exhibited an increased 12‐month mortality risk, suggesting a negative impact of PE on overall survival. 25 The same applies to patients with chronic HF. 30

Our study, covering a longer follow‐up time (median, 34 months), and including a population without clinical indication for an echocardiography examination, showed that PE resolved in the majority of participants during follow‐up, similarly to hospitalized patients. 25 Further, we found no prognostic implication of PE in the general population. This is most probably due to cohort differences, including the recruitment strategy and population demographics (ie, age difference up to 13 years). Unlike earlier studies that included significantly more men and patients with more comorbidities, including hospitalized individuals (up to 58% of the study population), our study featured an age‐ and sex‐adjusted distribution and individuals without overt HF.

Our data provide reassuring evidence that a small asymptomatic PE coincidentally detected in an individual of the general population is not an unfavorable sign. Consequently, our results lend support to a more conservative approach to the diagnosis, treatment, and further monitoring of such individuals, particularly when incidental findings are encountered. Nevertheless, our results require confirmation in other cohorts.

One limitation of our study is the reliance on TTE as a technique that requires a good acoustic window and has limitations in imaging the entire pericardium. 8 Thus, with TTE, we cannot determine with absolute certainty whether the observed substance is fluid, fat, or debris. In such cases, cardiac magnetic resonance would be the preferred method. However, cardiac magnetic resonance is not typically indicated for use in the general population; rather, it is considered a specialized diagnostic tool. Furthermore, our data set lacks sufficient information to offer further insights regarding moderate to large effusions. The fact that 21% of the study participants did not attend the follow‐up examination might have introduced attrition bias. However, nonparticipation in the follow‐up examination was not associated with PE. Further, the resolution of PE from baseline to follow‐up was nearly 3.5 times more frequent than the incidence of new cases. In a population without intervention, like ours, one would expect a steady state. This represents a typical situation where the measurement in a system (participants were told the results) inadvertently alters the system, even if unintended. Thus, the change in prevalence between time points is not epidemiologically interpretable. Another limitation of this work is the low number of events accrued during the observation period, thus reducing the statistical power of prognostic analyses. On the other hand, a strength of our study is that it was not restricted to individuals referred for echocardiography due to specific clinical concerns. Instead, it included a sample from the general population, encompassing relatively healthy individuals. This broader inclusion allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the PE as a phenomenon under investigation.

Conclusions

In a population‐based sample free from HF, we detected a small and asymptomatic PE in nearly 3% of participants. In the majority of individuals, PE had resolved in the course of 3 years. The prevalence of PE was higher in individuals with lower BMI and higher NT‐proBNP levels, yet PE was not associated with death, incident HF, or malignancy inflammation. Hence, small PEs in asymptomatic individuals might be considered an innocent phenomenon, not requiring further investigation.

Appendix

STAAB Consortium

Stefan Frantz (Department of Medicine I, Division of Cardiology, University Hospital Würzburg); Christoph Maack (Comprehensive Heart Failure Center, University Hospital and the University of Würzburg); Georg Ertl (University Hospital Würzburg); Martin Fassnacht (Department of Medicine I, Division of Endocrinology, University Hospital Würzburg); Christoph Wanner (Department of Medicine I, Division of Nephrology, University Hospital Würzburg); Rainer Leyh (Department of Cardiac & Thoracic Surgery, University Hospital Würzburg); Jens Volkmann (Department of Neurology, University Hospital Würzburg); Jürgen Deckert (Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy, Center of Mental Health, University Hospital Würzburg); Hermann Faller (Department of Medical Psychology, University of Würzburg); Roland Jahns (Interdisciplinary Bank of Biomaterials and Data Würzburg, University Hospital Würzburg).

Sources of Funding

The study is supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research within the Comprehensive Heart Failure Center, Würzburg (BMBF 01EO1004 and 01EO1504). There is no relationship with the industry.

Disclosures

Dr Kerwagen reports travel support from Novartis and Lilly, and research support from the German Research Council (DFG, Project No. 413657723), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Project No. 16SV8877), Novartis, and Bayer. Dr Heuschmann is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the STAAB Study. He also received institutional research grants from the German Ministry of Research and Education, the European Union, the German Parkinson Society, University Hospital Würzburg German Heart Foundation, Federal Joint Committee within the Innovation fond, German Research Foundation, Bavarian State, German Cancer Aid, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin (within Mondafis; supported by an unrestricted research grant to the Charité from Bayer), University Göttingen (within FIND‐AF randomized; supported by an unrestricted research grant to the University Göttingen from Boehringer‐Ingelheim), University Hospital Heidelberg (within RASUNOA‐prime; supported by an unrestricted research grant to the University Hospital Heidelberg from Bayer, BMS, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo). Participation in DSMB in publicly funded studies (by German Research Foundation, German Ministry of Research, Foundations). Dr Störk is supported by the Comprehensive Heart Failure Center Würzburg and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. He has received consultancy or lecture fees or reimbursement of travel costs from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Pharmacosmos, and Servier. Dr Morbach reports research cooperation with the University of Würzburg and Tomtec Imaging Systems funded by a research grant from the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy, Germany; advisory and speaker's honoraria as well as travel grants from Tomtec, Alnylam, Sobi, Alexion, Janssen, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, and EBR Systems; and principal investigator in trials sponsored by Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and Bayer. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the time and willingness of all STAAB participants to provide data for the study. The authors express their gratitude to the entire study team, including the study nurses, especially M. Bauer and C. Hahn, for the data analysis; technicians; data managers; and students, for their efforts in the STAAB study. The authors also thank M. Ertl, G. Fette, and F. Puppe from the Comprehensive Heart Failure Center DataWarehouse, Institute of Informatics VI, University of Wurzburg, as well as T. Ludwig, ICE‐B, for diligent data management.

Dr Sahiti: literature search, figures, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing; Dr Cejka: data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation; L. Schmidbauer: data collection and data interpretation; Dr Albert: data collection and data interpretation; Dr Kerwagen: data collection and data interpretation; Dr Frantz: obtained funding, study design, and data interpretation; Dr Gelbrich: study design, data analysis, and data interpretation; Dr Heuschmann: obtained funding, study design, and data interpretation; Dr Störk: obtained funding, study design, and data interpretation; Dr Morbach: literature search, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing.

This manuscript was sent to Erik B. Schelbert, MD, MS, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

Contributor Information

Caroline Morbach, Email: morbach_c@ukw.de.

of the STAAB consortium:

Christoph Maack, Georg Ertl, Christoph Wanner, Rainer Leyh, Jens Volkmann, Jürgen Deckert, Hermann Faller, and Roland Jahns

References

- 1. Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Baron‐Esquivias G, Bogaert J, Brucato A, Gueret P, Klingel K, Lionis C, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the task force for the diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2921–2964. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azarbal A, LeWinter MM. Pericardial effusion. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:515–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sugiura T, Kumon Y, Kataoka H, Matsumura Y, Takeuchi H, Doi Y. Asymptomatic pericardial effusion in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cardiology. 2008;110:87–91. doi: 10.1159/000110485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Brand F, Anderson SJ, Castelli WP, Kannel WB, Feinleib M. Prevalence and correlates of posterior extra echocardiographic spaces in a free‐living population based sample (the Framingham study). Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90370-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Filippo O, Gatti P, Rettegno S, Iannaccone M, D'Ascenzo F, Lazaros G, Brucato A, Tousoulis D, Adler Y, Imazio M. Is pericardial effusion a negative prognostic marker? Meta‐analysis of outcomes of pericardial effusion. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2019;20:39–45. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Imazio M, Mayosi BM, Brucato A, Markel G, Trinchero R, Spodick DH, Adler Y. Triage and management of pericardial effusion. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010;11:928–935. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32833e5788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klein AL, Abbara S, Agler DA, Appleton CP, Asher CR, Hoit B, Hung J, Garcia MJ, Kronzon I, Oh JK, et al. American Society of Echocardiography clinical recommendations for multimodality cardiovascular imaging of patients with pericardial disease: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Society of cardiovascular computed tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:965–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cosyns B, Plein S, Nihoyanopoulos P, Smiseth O, Achenbach S, Andrade MJ, Pepi M, Ristic A, Imazio M, Paelinck B, et al. European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) position paper: multimodality imaging in pericardial disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:12–31. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lazaros G, Imazio M, Tsioufis P, Lazarou E, Vlachopoulos C, Tsioufis C. Chronic pericardial effusion: causes and management. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2023.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagner M, Tiffe T, Morbach C, Gelbrich G, Stork S, Heuschmann PU; Consortium S . Characteristics and course of heart failure stages A‐B and determinants of progression—design and rationale of the STAAB cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:468–479. doi: 10.1177/2047487316680693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morbach C, Gelbrich G, Tiffe T, Eichner FA, Christa M, Mattern R, Breunig M, Cejka V, Wagner M, Heuschmann PU, et al. Prevalence and determinants of the precursor stages of heart failure: results from the population‐based STAAB cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28:924–934. doi: 10.1177/2047487320922636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sahiti F, Morbach C, Cejka V, Tiffe T, Wagner M, Eichner FA, Gelbrich G, Heuschmann PU, Stork S. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors on myocardial work‐insights from the STAAB cohort study. J Hum Hypertens. 2021;36:235–245. doi: 10.1038/s41371-021-00509-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morbach C, Gelbrich G, Breunig M, Tiffe T, Wagner M, Heuschmann PU, Stork S. Impact of acquisition and interpretation on total inter‐observer variability in echocardiography: results from the quality assurance program of the STAAB cohort study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34:1057–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10554-018-1315-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:233–270. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kennedy Hall M, Coffey EC, Herbst M, Liu R, Pare JR, Andrew Taylor R, Thomas S, Moore CL. The “5Es” of emergency physician‐performed focused cardiac ultrasound: a protocol for rapid identification of effusion, ejection, equality, exit, and entrance. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:583–593. doi: 10.1111/acem.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perez‐Casares A, Cesar S, Brunet‐Garcia L, Sanchez‐de‐Toledo J. Echocardiographic evaluation of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:79. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vakamudi S, Ho N, Cremer PC. Pericardial effusions: causes, diagnosis, and management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;59:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamani N, Abbasi A, Almas T, Mookadam F, Unzek S. Diagnosis, treatment, and management of pericardial effusion‐review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;80:104142. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arntfield RT, Millington SJ. Point of care cardiac ultrasound applications in the emergency department and intensive care unit–a review. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012;8:98–108. doi: 10.2174/157340312801784952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tayal VS, Kline JA. Emergency echocardiography to detect pericardial effusion in patients in PEA and near‐PEA states. Resuscitation. 2003;59:315–318. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00245-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang J, Patel M, Xiao M, Xu Z, Jiang S, Sun X, Xu L, Wang H. Incidence and predictors of asymptomatic pericardial effusion after transcatheter closure of atrial septal defect. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:e250–e256. doi: 10.4244/EIJV12I2A39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reddy P, Kane GC, Oh JK, Luis SA. The evolving etiologic and epidemiologic portrait of pericardial disease. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2023.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghantous E, Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Levi E, Taieb P, Banai A, Sapir O, Granot Y, Lupu L, Hochstadt A, et al. Pericardial involvement in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19: prevalence, associates, and clinical implications. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e024363. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mitiku TY, Heidenreich PA. A small pericardial effusion is a marker of increased mortality. Am Heart J. 2011;161:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ntsekhe M. Pericardial disease in the developing world. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39:1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2023.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guindo J. Comments on the 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. A report by the Spanish Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee Working Group. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2015;68:1068–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Conte E, Agalbato C, Lauri G, Mushtaq S, Carollo C, Bonomi A, Zanotto L, Melotti E, Dalla Cia A, Guglielmo M, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of pericardial effusion in patients affected by pectus excavatum: a case‐control study. Int J Cardiol. 2021;344:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Outcomes of clinically significant idiopathic pericardial effusion requiring intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:704–707. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03408-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frohlich GM, Keller P, Schmid F, Wolfrum M, Osranek M, Falk C, Noll G, Enseleit F, Reinthaler M, Meier P, et al. Haemodynamically irrelevant pericardial effusion is associated with increased mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1414–1423. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]