Abstract

Background

Chronic sympathetic stimulation drives desensitization and downregulation of β1 adrenergic receptor (β1AR) in heart failure. We aim to explore the differential downregulation subcellular pools of β1AR signaling in the heart.

Methods and Results

We applied chronic infusion of isoproterenol to induced cardiomyopathy in male C57BL/6J mice. We applied confocal and proximity ligation assay to examine β1AR association with L‐type calcium channel, ryanodine receptor 2, and SERCA2a ((Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a) and Förster resonance energy transfer‐based biosensors to probe subcellular β1AR‐PKA (protein kinase A) signaling in ventricular myocytes. Chronic infusion of isoproterenol led to reduced β1AR protein levels, receptor association with L‐type calcium channel and ryanodine receptor 2 measured by proximity ligation (puncta/cell, 29.65 saline versus 14.17 isoproterenol, P<0.05), and receptor‐induced PKA signaling at the plasma membrane (Förster resonance energy transfer, 28.9% saline versus 1.9% isoproterenol, P<0.05) and ryanodine receptor 2 complex (Förster resonance energy transfer, 30.2% saline versus 10.6% isoproterenol, P<0.05). However, the β1AR association with SERCA2a was enhanced (puncta/cell, 51.4 saline versus 87.5 isoproterenol, P<0.05), and the receptor signal was minimally affected. The isoproterenol‐infused hearts displayed decreased PDE4D (phosphodiesterase 4D) and PDE3A and increased PDE2A, PDE4A, and PDE4B protein levels. We observed a reduced role of PDE4 and enhanced roles of PDE2 and PDE3 on the β1AR‐PKA activity at the ryanodine receptor 2 complexes and myocyte shortening. Despite the enhanced β1AR association with SERCA2a, the endogenous norepinephrine‐induced signaling was reduced at the SERCA2a complexes. Inhibiting monoamine oxidase A rescued the norepinephrine‐induced PKA signaling at the SERCA2a and myocyte shortening.

Conclusions

This study reveals distinct mechanisms for the downregulation of subcellular β1AR signaling in the heart under chronic adrenergic stimulation.

Keywords: (Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a, cardiac contractility, Förster resonance energy transfer, phosphodiesterase, protein kinase a, ryanodine receptor, β1 adrenergic receptor

Subject Categories: Cell Signalling/Signal Transduction, Contractile function

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AKAP

A‐kinase anchoring protein

- AKAR

A‐kinase activity reporter

- AVM

adult ventricular myocyte

- β1AR

β1 adrenergic receptor

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- CGP

CGP 20712A

- EHNA

erythro‐9‐(2‐hydroxy‐3‐nonly)adenine

- FKBP

FK506 binding protein 12.6

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- ICI

ICI‐118551

- LTCC

L‐type calcium channel

- MAO‐A

monoamino oxidase A

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PLB

phospholamban

- PM

plasma membrane

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- SERCA2a

(Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

Research Perspective.

What Is New?

Chronic stimulation reduced cardiac β1 adrenergic receptor expression and signaling associated with L‐type calcium channel and ryanodine receptor complexes, which were also controlled by PDE2 (phosphodiesterase 2) and PDE3.

Although norepinephrine‐induced cardiac β1 adrenergic receptor signaling at the SERCA2a ((Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a) complexes is reduced in myocytes from mice after chronic infusion of isoproterenol, inhibiting MAO‐A (monoamino oxidase A) rescues the norepinephrine‐induced β1 adrenergic receptor signaling at the SERCA2a complexes, PKA (protein kinase A) phosphorylation of phospholamban, and excitation‐contraction coupling.

What Question Should Be Addressed Next?

Future studies should address how the subcellular cardiac β1 adrenergic receptor is altered in other cardiac disease models and whether inhibition of MAO‐A is effective in rescuing excitation‐contraction coupling in human heart failure.

Adrenergic signaling is downregulated in various cardiac diseases, a hallmark of heart failure (HF). In classic literature, the primary cardiac β1 adrenergic receptor (β1AR) undergoes desensitization via receptor phosphorylation driven by chronic sympathetic activation, which uncouples the receptor from G proteins and scaffold proteins such as SAP97 (synapse‐associated protein‐97) and AKAP (A‐kinase anchoring protein). 1 , 2 , 3 Interestingly, we have recently identified a novel pool of intracellular β1AR specifically associated with SERCA2a ((Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a), critical for catecholamine stimulation of excitation‐contraction coupling and cardiac contractility. 4 , 5 , 6 Here, we aimed to understand how chronic adrenergic stimulation affects the subcellular pools of β1AR signaling in cardiomyopathy.

Stimulation of β1AR promotes PKA (protein kinase A) phosphorylation and increases the activities of L‐type calcium channel (LTCC), ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2), and SERCA2a, critical ion regulators to enhance cardiac excitation‐contraction coupling during stress response. 7 , 8 RyR2 is closely coupled to LTCC at the tubular membrane and releases calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to the cytoplasm to enhance excitation‐contraction coupling. Conversely, SERCA2a is modulated by a negative regulator, PLB (phospholamban), and is responsible for calcium uptake during cardiac relaxation. Both RyR2 and PLB are regulated by PKA phosphorylation under adrenergic stimulation. Recent studies highlight distinct local signaling based on the distribution of the β1AR, AKAP scaffold proteins, and downstream effectors such as LTCC, RyR2, and SERCA2a. 4 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Whereas the β1AR is associated with LTCC on the plasma membrane (PM), a second pool of β1AR is associated with SERCA2a at the SR. 4 , 5 , 6 PKA is anchored on different AKAPs to promote local phosphorylation of RyR2 and PLB to increase ion channel and pump activities. 7 , 8 Additionally, PDEs (phosphodiesterases) emerge as critical regulators to fine‐tune adrenergic‐induced local cAMP and PKA activity at distinct subcellular compartments. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 RyR2 is associated with PDE4D3 and scaffold proteins such as muscle‐specific AKAP. 17 , 18 In comparison, AKAP18δ, PDE3, and PDE4 are linked to the SERCA2a. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 How the subcellular β1AR‐PKA signaling is remodeled in heart diseases is incompletely understood.

In this study, we aimed to investigate subcellular adrenergic signaling remodeling in cardiomyopathy with a chronic infusion of β‐agonist isoproterenol. We used proximity ligation assay to examine the β1AR association with LTCC, RyR2, and SERCA2a in isolated adult ventricular myocytes (AVMs). We also applied Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensors‐based AKARs (A‐kinase activity reporters) 22 , 23 , 24 to examine PKA activity at the RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes in AVMs. We further assess the impacts of altered β1AR‐PKA signaling on cardiac excitation‐contraction coupling in the cardiomyopathy induced by chronic isoproterenol infusion. Our data highlight distinct mechanisms underlying the downregulation of subcellular β1AR‐PKA signaling in AVMs after chronic adrenergic stress in the heart.

METHODS

Data Availability

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files.

Animals

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (protocol number: 20956 and 20957) of the University of California at Davis according to the National Institutes of Health and Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines. Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA); 10‐ to 12‐week‐old mice (15/group) were used in chronic infusion of isoproterenol to induce cardiomyopathies or saline as control. 25 , 26 Animals were housed in cages in a room with controlled temperature, humidity, and 12‐12‐hour light–dark cycle. Animals developing cardiomyopathy were monitored daily and terminated when reaching human end point. After anesthesia with inhalation of 2.0% isoflurane and oxygen, mice were euthanized to harvest hearts. All studies were randomized and blinded for data analysis. All samples or animals were included in the analysis.

Reagents

All reagents were obtained from Millipore‐Sigma (St. Louis, MO). β‐adrenergic agonist, isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) was applied to cultured mouse myocytes with a β1AR antagonist (CGP 20712A, 300 nmol/L) or a β2AR antagonist (ICI 118551, 100 nmol/L). Forskolin (10 μmol/L) and isobutylmethylxanthine (100 μmol/L) were used to activate cAMP and PKA in myocytes maximally. Inhibitor of PDE4 rolipram (10 μmol/L), PDE2 erythro‐9‐(2‐hydroxy‐3‐nonly)adenine (10 μmol/L), and PDE3 cilostamide (1 μmol/L) were also used as indicated. Calcium indicator fluo‐4 AM (2–5 μmol/L, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to measure calcium transient. All 3 PKA activity biosensors, PM‐AKAR3, SR‐AKAR3, and FKBP (FK506 binding protein)‐AKAR3, have been extensively characterized previously. 22 , 23 , 27 FKBP‐AKAR3 was generated by fusing AKAR3 to the C‐terminus of FKBP12.6. SR‐AKAR3 was generated by fusing AKAR3 to the C‐terminus of monomerized PLB, whereas PM‐AKAR3 was generated by fusing the CAAX membrane targeting sequence KKKKKSKTKCVIM to the C‐terminus of AKAR3 described previously. 22 , 23 , 27 The AKAR3 cDNAs were then subcloned into pshuttle vector to generate recombinant padeasy vector for making adenovirus. Adenoviruses containing the AKAR3 fusion genes were made and further amplified in HEK293 cells. The recombinant was purified with a CsCl gradient. We successfully produced the adenoviruses with a titer of 1010 to 1012 pfu/mL. 22 , 23 , 27

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Animals were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (1%–1.5%) via a nose cone for transthoracic echocardiography. The mice were placed on the platform of the Vevo 2100 imaging system (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) in the supine position. The ECG, body temperature, and respiration rate were measured while maintaining the heart rate at around 450 beats per minute. A 22 to 55 MHz linear probe (MS550D) was used to collect the 2‐dimensional short‐axis projection images. 3 , 25 Systolic heart function parameters were analyzed in at least 3 heartbeats from each image in a blinded fashion.

Adult Ventricular Cardiomyocytes Isolation From Adult Mice

AVMs were isolated as previously described. 3 , 25 , 28 The anesthesia of mice was induced by 2% isoflurane. The isolated heart was cannuled to a Langendorf perfusion system. The heart was perfused with the digestion buffer (NaCl 120 mmol/L, NaH2PO4 1.2 mmol/L, KCl 5.4 mmol/L, MgSO4 1.2 mmol/L, NaHCO3 20 mmol/L, glucose 5.6 mmol/L, taurine 20 mmol/L, 2,3‐butanedione monoxime 10 mmol/L, PH7.4). Subsequently, the heart was perfused with the buffer containing collagenase and protease (predigestion solution: 0.05% type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ), 0.01% type XIV protease (Sigma‐Aldrich), and 0.1% BSA; digestion solution: 0.2% type II collagenase, 0.04% type XIV protease, 50 μmol/L CaCl2, and 0.1% BSA). The isolated myocytes were harvested from digestion buffer. Isolated AVMs were used for Western blotting, calcium transient and sarcomere shortening recording, proximity ligation assays, and FRET assays.

Western Blotting

AVMs from saline and isoproterenol‐induced mice were treated with rolipram (10 μmol/L, Sigma‐Aldrich) for 10 minutes. Alternatively, AVMs were treated with rolipram and isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) stimulation for 10 minutes to detect the effects of rolipram on isoproterenol‐induced phosphorylation of PLB and RyR. The treated AVMs or heart tissues from indicated mice were lysed with RIPA buffer supplement with proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors. Immunoblotting was applied to detect the phospho‐RyR at Ser2808 (ab59225, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), phospho‐RyR at Ser2814 (pRyRS2814, A010‐31AP, Badrilla, Leeds, UK), RyR (MA3‐925, Thermofisher, IL), β1AR (sc‐568, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), PDE4D (ab14613, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), PLB (A010‐14, Badrilla, Leeds, UK), phospho‐PLB at Ser16 (pPLBS16, A010‐12AP, Badrilla, Leeds, UK), phospho‐PLB at Thr17 (pPLBT17, A010‐13AP, Badrilla, Leeds, UK), SERCA2a (MA3‐911, Thermo Fisher Scientific. Waltham, MA), PDE3A (kind gifts from Yan Chen at University of Rochester), PDE4A and PDE4B (kind gifts from Marco Conti at University of California at San Francisco), TnI (troponin I; 4002, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), phospho‐TnI at Ser23/24 (pTnIS23/24, 4004, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and γ‐tubulin (T6557, Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO). The antibodies for β1AR and LTCC have been validated previously. 3 , 29 IRDye 680RD goat anti‐rabbit IgG secondary antibody (926–68 071, LI‐COR, Lincoln, NE) and IRDye 800CW goat anti‐mouse IgG secondary antibody (926–32 210, LI‐COR, Lincoln, NE) were used for multicolor detection. PVDF membranes were scanned on Biorad Chemidoc MP imaging system (Biorad Laboratory, CA). The optical density of the bands was analyzed with National Institutes of Health Image J software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Assay

The FRET assay was carried out following the method reported before. 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 Briefly, AVMs were cultured in serum‐free M1018 media with 6.25 μmol/L blebbistatin (PH 7.35, Sigma‐Aldrich). Cells were infected with adenoviruses expressing PM‐AKAR3, FKBP‐AKAR3, and SR‐AKAR3 22 , 23 biosensors for 36 hours before recording (DMI3000 B, Buffalo Grove, IL). Recombinant adenoviruses were generated with the pAdeasy system (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described. 22 , 23 , 27 , 28 The myocytes were recorded using Metafluor software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). CFP (cyan fluorescent protein) and YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) were imaged (200 milliseconds) with 20‐second interval. AVMs were recorded at the baseline and after treatment with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L), ICI 118551 (ICI, I127, Sigma‐Aldrich), CGP 20712a (CGP, C125, Sigma‐Aldrich), rolipram (Sigma‐Aldrich), isobutylmethylxanthine (HY‐12318, MedChemExpress LLC), and forskolin (F‐9929, LC Laboratories). Fluorescence emission intensity at 545 nmol/L (YFP) and 480 nmol/L (CFP) was subjected to background subtraction. YFP/CFP ratio was analyzed as F/F0, in which F is at time t and F0 is the baseline. An increase in the YFP/CFP indicates the activation of PKA. The numbers of animals and cells were labeled in the figures.

AVMs Sarcomere Shortening and Calcium Transient Detection

As previously reported, 3 , 25 , 30 freshly isolated AVMs were loaded with 5 μmol/L Fluo‐4 AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature and rinsed with PBS without calcium for 10 minutes. AVMs were then placed on a dish and paced at 1 Hz with a SD9 stimulator (Grass Technology, Warwick, RI). Metamorph software was used to image beating cells in a bright field or in 488 nm emission channel before and 5 minutes after drug administration with a Zeiss AX10 inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss AX10, Dublin, CA). Fractional shortening was analyzed in movies acquired in bright field using Metamorph software and calcium transient amplitude and decay time (Tau) were analyzed in movies acquired in 488 nm channel using customized software (GaiLab) as reported. 3 , 25 , 30 The numbers of animals and cells were labeled in the figures.

Proximity Ligation Assay

AVMs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. AVMs were permeabilized (0.2% NP‐40, 2% goat serum in PBS) and incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies against β1AR and LTCC Cav1.2, β1AR and RyR2, β1AR and SERCA2a, or RyR2 and SERCA2a (Table S1). Mouse normal IgG (sc‐2025, Santa Cruz) were used as controls. SERCA2a (MAB2636, Millipore, CA), LTCC Cav1.2 (NeuroMab Clone N263/31), RyR2 (MA3‐925, Thermo fisher, MA), and rabbit polyclonal β1AR (sc‐568, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) antibodies were used to detect the in situ interaction between β1AR and LTCC, SERCA2a, or RyR in AVMs from isoproterenol infusion mice and the controls. After incubation with the primary antibodies, the AVMs were incubated with secondary antibodies against mouse and rabbit primary antibodies labeled with oligonucleotides, which when present within 40 nm undertake rolling circle amplification to generate a specific fluorescent signal after the addition of labeled probes. The samples were subjected to proximity ligation assay based on the manufacturer's protocol (Sigma‐Aldrich). The color images of polymerized DNA were collected on a Leica Falcon SP8 confocal microscope and analyzed double‐blindly on ImageJ. Representative figures/images reflected the average levels of each experiment.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM. The sample size was calculated using power analysis with a power of 0.8 for a value of α=0.05. To achieve statistical significance, the sample size (number) was at least 5. An unpaired, 2‐tailed Student t test was used for 2‐group comparisons and ANOVA with multiple testing correction for 3 or more group comparisons, performed on continuous, normally distributed data assessed in GraphPad Prism 9 with significance at alpha=0.05 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). P≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Chronic Adrenergic Stress Promotes the Downregulation of β1AR and Signaling at the PM and RyR2 Complexes

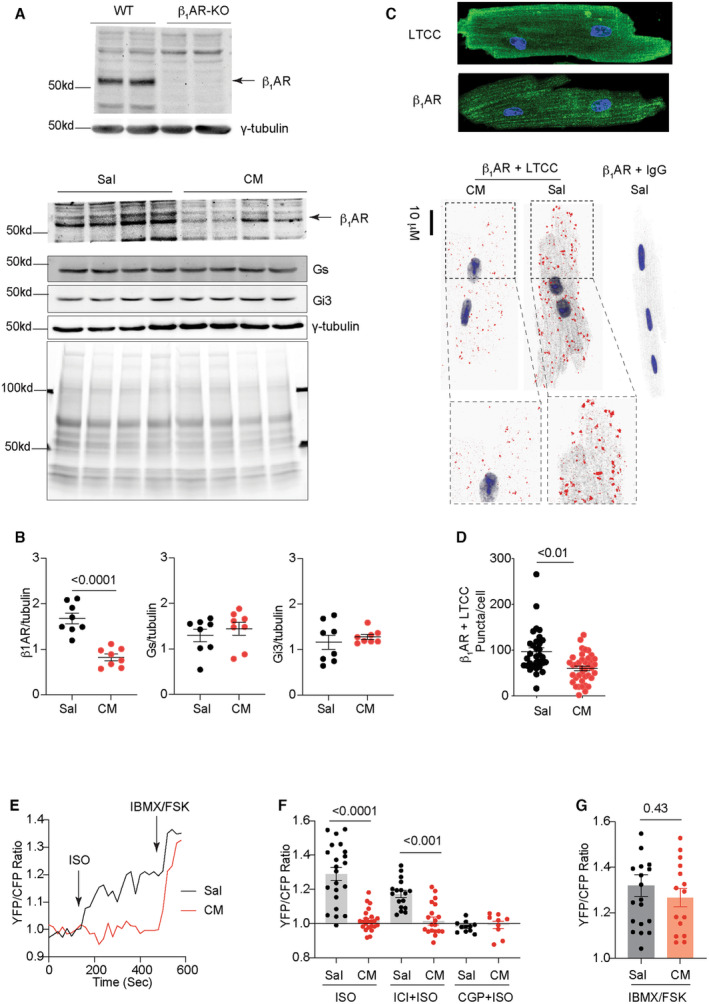

We examined the alteration of adrenergic signaling in cardiomyopathy induced by chronic isoproterenol infusion (60 mg/kg per day, 2 weeks). The isoproterenol infusion‐induced cardiomyopathy was featured with decreased ejection fraction (Table S2). 5 , 31 , 32 After chronic isoproterenol infusion, mouse hearts displayed reduced protein level of the β1AR but not G proteins (Figure 1A and 1B, 33 ). We performed proximity ligation assay between β1AR and LTCC to examine the receptor association with LTCC on the PM of AVMs isolated from mice after saline and isoproterenol infusion. AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused hearts displayed a reduced β1AR association with LTCC compared with saline controls (Figure 1C and 1D). We also applied FRET‐based PKA biosensor AKAR3 anchored on the PM (PM‐AKAR3) to detect PKA activity induced by adrenergic stimulation (Figure 1E). In AVMs from saline‐infused mice, stimulation with isoproterenol induced robust increases in the FRET ratio of PM‐AKAR3 biosensor, indicating increases in PKA activities (Figure 1E). β1AR blocker CGP20712a but not β2AR blocker ICI118551abolished the adrenergic‐induced PKA activities at the PM in AVMs (Figure 1F). However, isoproterenol minimally increased the FRET ratio of PM‐AKAR3 biosensors in AVMs from mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion (Figure 1E and 1F). As a control, isobutylmethylxanthine and forskolin promoted equivalent PKA activities in AVMs from both saline and isoproterenol ‐infused mice (Figure 1E and 1G). These data suggest cardiac β1AR‐PKA signaling is downregulated at the PM in AVMs after chronic adrenergic stress.

Figure 1. Chronic adrenergic stress promotes the downregulation of cardiac β1AR protein and signaling at the plasma membrane.

A and B, Western blots show the specific detection of β1AR in heart lysates from WT and β1AR‐KO mice, and protein levels of β1AR, Gs, and Gi3 in the hearts after chronic infusion with saline and isoproterenol (cardiomyopathy) for 2 weeks. Multiple bands of β1AR detected with antibody may be due to posttranslational modification of the receptor. 33 Coomassie blue staining shows total protein loads. N=8. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. C and D, Immunofluorescence staining of β1AR and LTCC in AVMs. Proximity ligation assay to probe the association between β1AR and LTCC on the plasma membrane in AVMs isolated from mice after chronic infusion with saline or isoproterenol. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of the indicated number of AVMs from 5 mice. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. E and F, Time courses and maximal increases in PM‐AKAR3 YFP/CFP ratio in AVMs after isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) stimulation alone or in the presence of β1AR antagonist CGP20712a (CGP, 300 nmol/L) or β2AR antagonist ICI118551 (ICI, 100 nmol/L). Isobutylmethylxanthine (100 μmol/L) and forskolin (10 μmol/L) were added after isoproterenol stimulation. P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. G, Maximal increases in YFP/CFP ratio of PM‐AKAR3 after stimulation with isoproterenol or isobutylmethylxanthine+forskolin. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of the indicated number of AVMs from 6 mice. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; β1AR, β1 adrenergic receptor; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; CGP, CGP20712a; CM, cardiomyopathy; FSK, forskolin; Gs, stimulatory G protein, Gi3, inhibitory G protein 3; IBMX, isobutylmethylxanthine; ICI, ICI118551; ISO, isoproterenol; KO, knockout; LTCC, L‐type calcium channel; PM‐AKAR3, plasma membrane anchored a kinase activity reporter 3, Sal, saline; WT, wild type; and YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

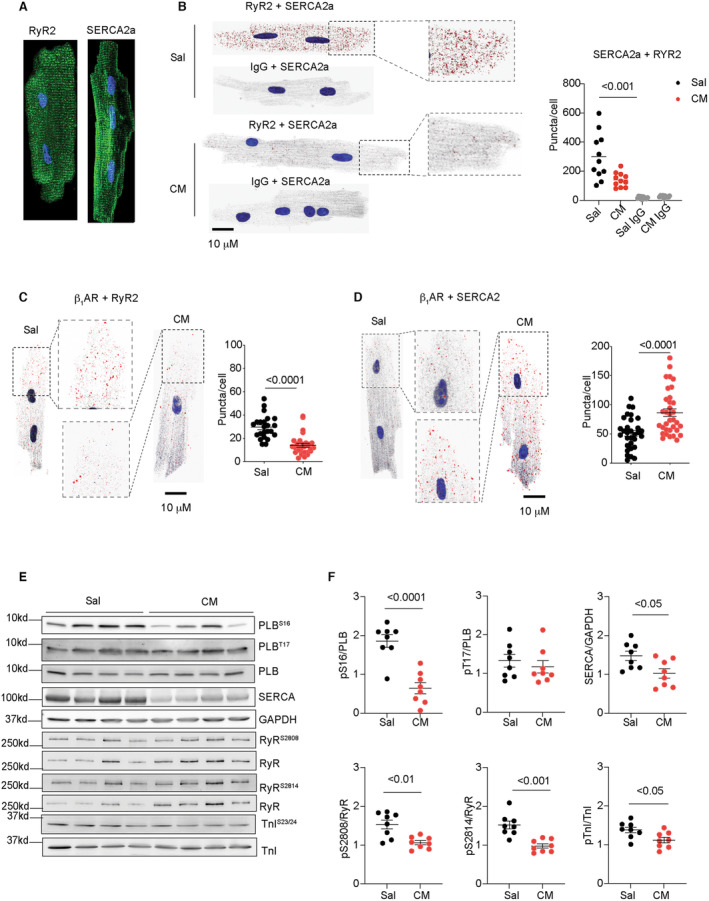

Both SERCA2a and RyR2 are distributed on the SR membrane. SERCA2a and RyR2 also displayed an association in healthy AVMs, which was drastically reduced in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice (Figure 2A and 2B). We have recently shown that an intracellular pool of β1AR selectively forms complexes with SERCA2a, 4 , 5 which draws a contrast to the receptor at the PM. In isolated AVMs, we examined the β1AR association with RyR2 and SERCA2a at the SR. The isoproterenol‐infused mice displayed reduced β1AR association with RyR2 in AVMs (Figure 2C), whereas the association of β1AR with SERCA2a was increased (Figure 2D). Meanwhile, the isoproterenol‐infused hearts displayed reduced phosphorylation of RyR2 at serine 2808 and 2814 relative to saline controls (Figure 2E through 2F). The PKA phosphorylation of PLB at serine 16 was also reduced in the isoproterenol‐infused hearts, together with reduced SERCA2a protein expression (Figure 2E through 2F). Additionally, the hearts displayed minimal changes in phosphorylation of PLB at the Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II site of threonine 17 and phosphorylation of TnI at serine 23/24 after isoproterenol infusion relative to saline groups (Figure 2E through 2F).

Figure 2. Chronic adrenergic stress decreases β1AR association with RyR2 and increases β1AR association with SERCA2a.

A, Immunofluorescence staining of RyR2 and SERCA2a in AVMs. B, Proximity ligation assay to probe the association between RyR2 and SERCA2a in AVMs isolated from mice after chronic infusion with saline or isoproterenol (CM). Dot plots represent mean±SEM of individual AVMs from 5 mice. P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. C and D, Proximity ligation assay to probe the association of β1AR with RyR2 and SERCA2a in AVMs isolated from mice after chronic infusion with saline or isoproterenol. Dot plots represent mean±SEM of individual AVMs from 5 mice. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. E and F, The phosphorylation of PLB at serine 16 and threonine 17, RyR2 at serine 2808 and 2814, TnI at serine 23/24, and the total protein of PLB, SERCA2a, RyR2, and TnI were examined in Western blots and quantified in dot plots. N=8. Dot plots representing mean±SEM. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; β1AR, β1 adrenergic receptor; CM, cardiomyopathy; PLB, phospholamban; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; Sal, saline; SERCA2a, (Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a; and TnI, troponin I.

We then applied PKA biosensor FKBP‐AKAR3 anchored to RyR2 24 and SR‐AKAR3 anchored to SERCA2a 22 , 23 to analyze the subcellular βAR‐PKA signaling in AVMs (Figure 3A). AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice displayed a lower adrenergic‐induced PKA activity at the RyR2 than saline controls (Figure 3B through 3E). The adrenergic‐induced PKA activities at the RyR2 were abolished by β1AR blocker CGP20712a but not β2AR blocker ICI118551 in AVMs from both saline and isoproterenol‐infused hearts (Figure 3C through 3E). In comparison, AVMs from saline and isoproterenol‐infused hearts displayed similar adrenergic‐PKA signaling at the SERCA2a, which was blocked by CGP20712a but not by ICI118551 (Figure 3F through 3I). These data indicate that the isoproterenol‐induced β1AR signaling is selectively desensitized at the RyR2 in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice. Meanwhile, isobutylmethylxanthine and forskolin promoted equivalent PKA activities at RyR2 and SERCA2a between AVMs from saline and isoproterenol‐infused mice, respectively (Figure 3J and 3K). These data suggest distinct remodeling of β1AR‐PKA signaling at the RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes in the hearts after chronic adrenergic stimulation.

Figure 3. Chronic adrenergic stress selectively downregulates the β1AR‐induced PKA activity at the RyR2 but not at the SERCA2a.

A, Cartoon illustrates the FKBP‐AKAR3 and SR‐AKAR3 biosensors to detect local PKA activities at the RyR2‐ and SERCA2a‐associated nanodomains in AVMs. Mice were subjected to chronic infusion with saline or isoproterenol (CM). AVMs were isolated to express FKBP‐AKAR3 or SR‐AKAR3 biosensors. B through D, Time courses of FKBP‐AKAR3 YFP/CFP ratio in AVMs after isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) stimulation and in the presence of β1AR antagonist CGP20712a (CGP, 300 nmol/L) or β2AR antagonist ICI118551 (ICI, 100 nmol/L). After isoproterenol stimulation, Isobutylmethylxanthine (100 μmol/L) and forskolin (10 μmol/L) were added. E, Data show maximal increases in YFP/CFP ratio of FKBP‐AKAR3 after stimulation with isoproterenol alone or in the presence of β1AR antagonist CGP (300 nmol/L) or β2AR antagonist ICI (100 nmol/L). P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. F through H, Time courses of SR‐AKAR3 YFP/CFP ratio in AVMs after stimulation with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) and in the presence of β1AR antagonist CGP or β2AR antagonist ICI. Isobutylmethylxanthine (100 μmol/L) and forskolin (10 μmol/L) were added after isoproterenol stimulation. I, Data show maximal increases in YFP/CFP ratio of SR‐AKAR3 after stimulation with isoproterenol alone or in the presence of β1AR antagonist CGP (300 nmol/L) or β2AR antagonist ICI (100 nmol/L). P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. J and K, Data show maximal increase in YFP/CFP ratio of SR‐AKAR3 and FKBP‐AKAR3 after stimulation with isobutylmethylxanthine and forskolin. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of the indicated number of AVMs from 5 Sal and 8 CM mice. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; β1AR, β1 adrenergic receptor; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; CGP, CGP20712a; CM, cardiomyopathy; FKBP‐AKAR3, FK506 binding protein 12.6 anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; FSK, forskolin; IBMX, isobutylmethylxanthine; ICI, ICI118551; ISO, isoproterenol; PKA, protein kinase A; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; Sal, saline; SERCA2a, (Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a; SR‐AKAR3, sarcoplasmic reticulum anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; and YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

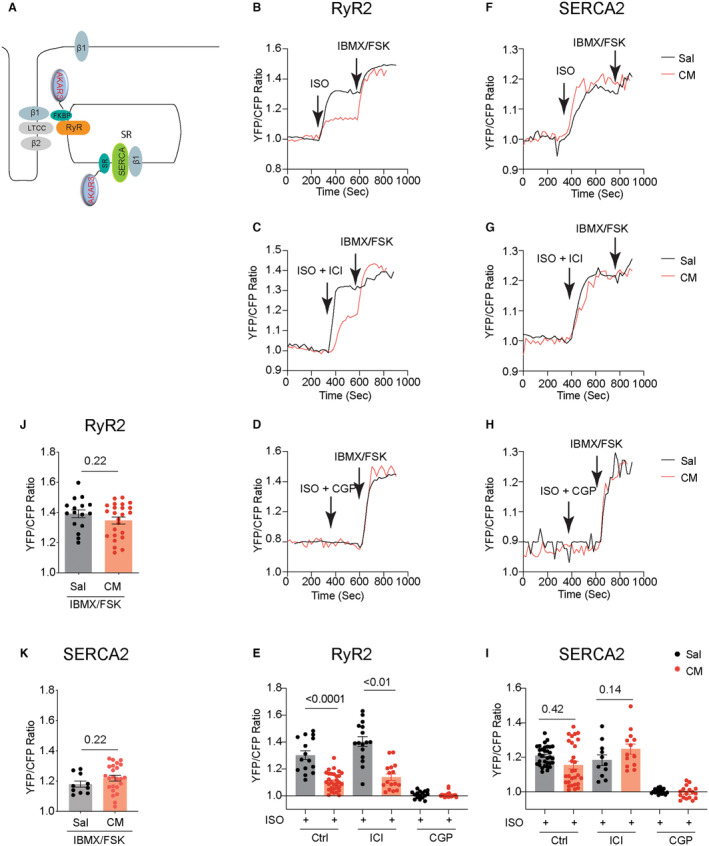

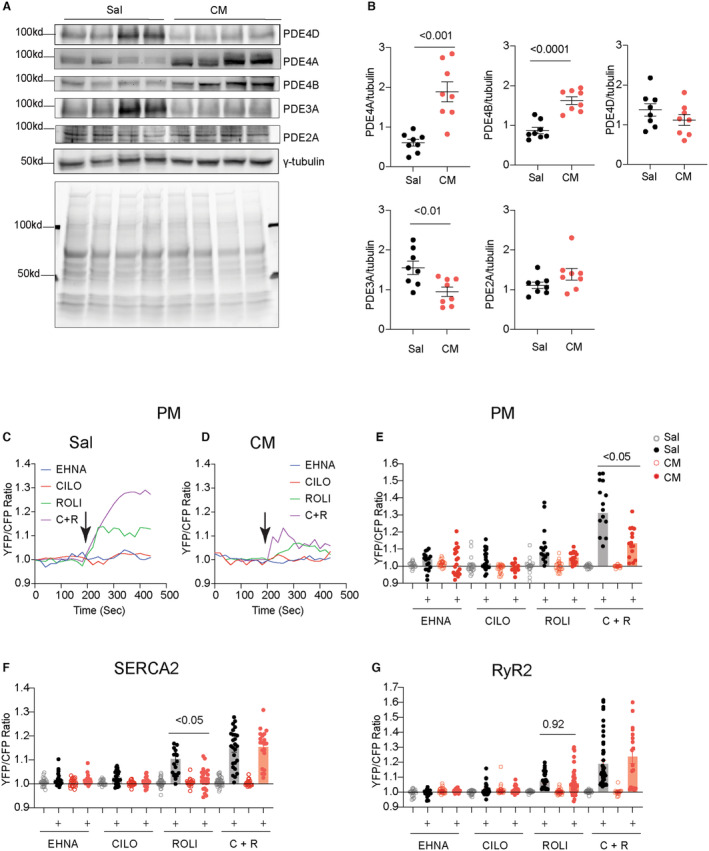

Chronic Adrenergic Stress Alters the Protein Levels of PDE3 and 4 Isoforms to Affect the Local PKA Activity at the RyR2 Complexes

We have previously shown that PDE4D isoforms associate with cardiac β1AR and β2AR and regulate subcellular cAMP‐PKA activity in AVMs. 13 , 14 , 15 Cardiac diseases are associated with altered PDE gene expression in the myocardium. 25 Among the highly expressed cardiac PDEs, we showed that cardiac PDE3A were reduced in the hearts after chronic isoproterenol infusion (Figure 4A and 4B). In comparison, PDE4A and PDE4B displayed increased protein levels in the isoproterenol‐infused hearts (Figure 4A and 4B). We assessed the individual PDE genes in controlling local cAMP‐PKA activities at different subcellular membranes. Inhibiting PDE4, but not PDE2 and PDE3, increased PKA activity at the PM in the control AVMs from saline mice (Figure 4C through 4E). Inhibition of PDE4 and PDE3 also synergistically enhanced PKA activities at the PM in control AVMs (Figure 4C through 4E). In AVMs from the mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion, inhibition of PDE4 alone or PDE3 and PDE4 together yielded smaller increases in PKA activities at the PM than saline controls (Figure 4D and 4E). Meanwhile, inhibition of PDE4 but not PDE2 and PDE3 promoted increases in PKA activities at the RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes in the control AVMs from saline mice (Figure 4F and 4G). Inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 synergistically increased PKA activities at the RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes (Figure 4F and 4G). In AVMs from the mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion, the PDE4 inhibitor‐induced response was attenuated at the SERCA2a but not in the RyR2 complexes (Figure 4F and 4G).

Figure 4. Chronic adrenergic stress changes the protein expression levels of phosphodiesterase isoforms and subcellular PKA activities at the RyR2 and SERCA2a.

A and B, Western blots show the protein levels of PDE2A, PDE3A, PDE4A, PDE4B, and PDE4D in the hearts after chronic infusion of saline or isoproterenol (CM). Coomassie blue staining shows total protein loads. N=8. Data represent mean±SEM of individual mice. P values were obtained using Student's t test. C and D, Time courses show PM‐AKAR3 YFP/CFP ratio after treatment with PDE2 inhibitor EHNA (10 μmol/L), PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (1 μmol/L), PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (10 μmol/L), or the combination of PDE3 and PDE4 inhibitor in AVMs from Sal and isoprotereno‐infused hearts. E through G, The baseline and maximal YFP/CFP ratio of PM‐AKAR3, SR‐AKAR3, and FKBP‐AKAR3 after treatment with PDE inhibitors. Dot plots represent mean±SEM of individual AVMs. P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; C+R, cilostamide+rolipram; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; Cilo, cilostamide; CM, cardiomyopathy; EHNA, erythro‐9‐(2‐hydroxy‐3‐nonly)adenine; FKBP‐AKAR3, FK506 binding protein 12.6 anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; PDE2A, phosphodiesterase 2A; PDE3A, phosphodiesterase 3A; PDE4D, phosphodiesterase 4D; PDE4A, phosphodiesterase 4A; PDE4B, phosphodiesterase 4B; PKA, protein kinase A; PM‐AKAR3, plasma membrane anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; Sal, saline; SERCA2a, (Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a; SR‐AKAR3, sarcoplasmic reticulum anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; Roli, rolipram; and YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

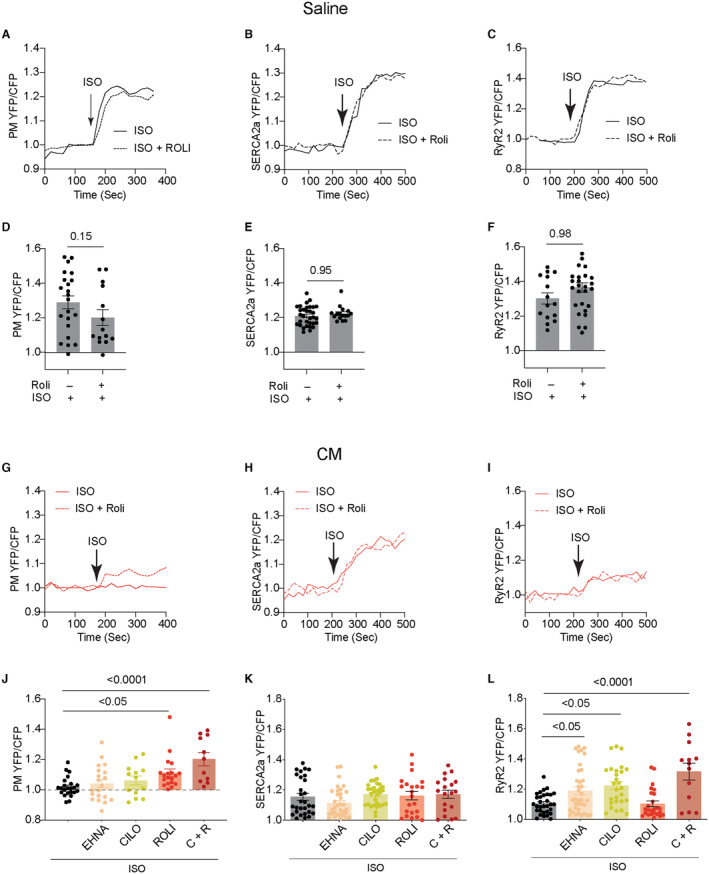

Inhibition of PDE3 and 4 Selectively Modulates the β1AR Signaling at the RyR2 Complexes

PDE4D isoforms are functionally linked to cardiac β1AR and β2AR signaling in AVMs. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 We further assessed the impacts of PDE4 inhibitors on adrenergic stimulation of local PKA activities in AVMs from mice after chronic saline or isoproterenol infusion. Inhibiting PDE4 did not alter the adrenergic stimulation of PKA activity at the PM and SERCA2a and RyR2 complexes in AVMs from saline control mice (Figure 5A through 5F). In AVMs from mice with chronic isoproterenol infusion, inhibiting PDE4 enhanced adrenergic stimulation of PKA activity at the PM but did not change the responses at the SERCA2a and RyR2 complexes (Figure 5G through 5I). Recent studies indicate that PDE2 and PDE3 may have increased roles in regulating cardiac adrenergic signaling in hypertrophic hearts. 28 , 34 Inhibiting either PDE2 or PDE3 enhanced adrenergic stimulation of PKA activities at the RyR2 complexes but not the PM and SERCA2a complexes in the AVMs from isoproterenol‐infused hearts (Figure 5J through 5L). Additionally, dual inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 enhanced the adrenergic stimulation of PKA activities at the PM and RyR2 complexes but not the SERCA2a complexes in the hearts after chronic isoproterenol infusion (Figure 5J through 5L).

Figure 5. Inhibiting PDE affects the isoproterenol‐induced subcellular PKA activities in AVMs from mice after chronic infusion with isoproterenol.

Mice were subjected to chronic infusion with saline or isoproterenol. AVMs were isolated to express PM‐AKAR3, FKBP‐AKAR3, and SR‐AKAR3 biosensors. A through C, AVMs from saline‐infused mice were stimulated with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) alone or together with PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (10 μmol/L). Time courses show PM‐AKAR3, SR‐AKAR3, and FKBP‐AKAR3 YFP/CFP ratio in AVMs after treatment. D through F, Dot plots represent mean±SEM of YFP/CFP ratio in individual AVMs from 5 mice. P values were analyzed using Student's t test. G through I, AVMs from isoproterenol‐infused mice were stimulated with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) alone or together with PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (10 μmol/L). Time courses show PM‐AKAR3, SR‐AKAR3, and FKBP‐AKAR3 YFP/CFP ratio in AVMs after treatment with isoproterenol and rolipram. J through L, AVMs from isoproterenol‐infused mice were stimulated with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) alone or together with PDE2 inhibitor EHNA (10 μmol/L), PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (1 μmol/L), PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (10 μmol/L), or the combination of cilostamide and rolipram. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of YFP/CFP ratio in individual AVMs from 5 mice. P values were analyzed using 1‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; C+R, cilostamide+rolipram; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; Cilo, cilostamide; CM, cardiomyopathy; EHNA, erythro‐9‐(2‐hydroxy‐3‐nonly)adenine; FKBP‐AKAR3, FK506 binding protein 12.6 anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; ISO, isoproterenol; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PKA, protein kinase A; PM‐AKAR3, plasma membrane anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; Roli, rolipram; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; Sal, saline; SERCA2a, (Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a; SR‐AKAR3, sarcoplasmic reticulum anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; and YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

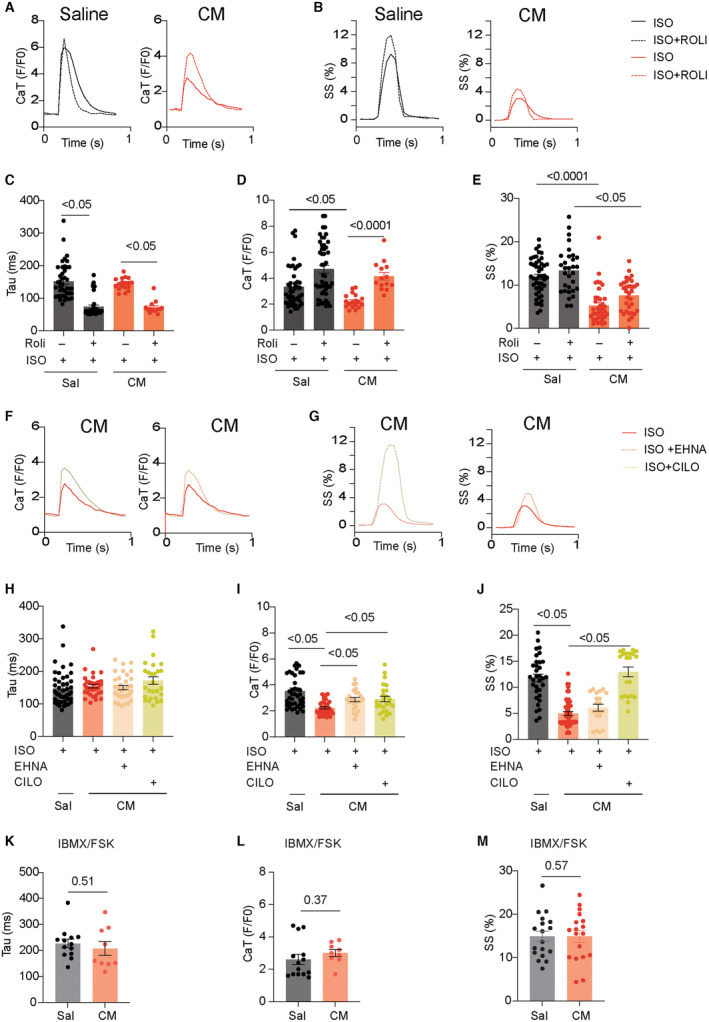

Inhibiting PDE4 also enhanced adrenergic stimulation of calcium transient amplitude and sarcomere contractile shortening in AVMs from saline control mice (Figure 6A through 6E). Although the adrenergic responses were reduced in AVMs from mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion, the effects of the PDE4 inhibitor were detected in calcium transient tau but not amplitude and sarcomere shortening (Figure 6A through 6E). Interestingly, inhibiting PDE3 rescued adrenergic responses in calcium transient amplitude and sarcomere contractile shortening, whereas inhibiting PDE2 only restored the isoproterenol‐induced calcium transient amplitude (Figure 6F through 6J). Addition of isobutylmethylxanthine and forskolin induced similar increases in calcium cycling and sarcomere shortening in AVMs from the saline and isoproterenol‐infused mice (Figure 6K through 6M). These data suggest that inhibition of PDE3 is an effective strategy to restore PKA activity at the RyR2, calcium cycling, and contractile shortening in AVMs from the mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion.

Figure 6. Inhibiting PDE rescues the adrenergic‐induced subcellular PKA activity and E‐C coupling in AVMs from mice after chronic infusion with isoproterenol.

AVMs from saline and isoproterenol (CM)‐infused mice were loaded with fluo‐4 dye and paced at 1 Hz. CaT decay tau and amplitude and SS were recorded in AVMs after stimulation with isoproterenol. A and B, AVMs were stimulated with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) in the presence of PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (10 μmol/L). CaT amplitude decay tau and SS were recorded in AVMs. Representative traces show CaT and SS. C through E, Data show maximal CaT amplitude and decay tau and SS in AVMs after stimulation. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of individual AVMs from 6 mice. P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. F through G, AVMs were stimulated with isoproterenol (100 nmol/L) in the presence of PDE2 inhibitor EHNA (10 μmol/L) or PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (1 μmol/L) as indicated. Representative traces show CaT and SS. H through J, Data show maximal CaT amplitude and decay tau and SS in AVMs after stimulation. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of individual AVMs from 6 mice. P values were analyzed using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. K through M, AVMs were stimulated with isobutylmethylxanthine (100 μmol/L) and forskolin (10 μmol/L). Data show maximal CaT amplitude and decay tau and SS in AVMs after stimulation. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of individual AVMs from 6 mice. P values were analyzed using Student's t‐test. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; CM, cardiomyopathy; CaT, calcium transient; Cilo, cilostamide; E‐C, excitation‐contraction; EHNA, erythro‐9‐(2‐hydroxy‐3‐nonly)adenine; FSK, forskolin; IBMX, isobutylmethylxanthine; ISO, isoproterenol; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PKA, protein kinase A; Roli, rolipram; Sal, saline; SS, sarcomere shortening; and tau, taurine.

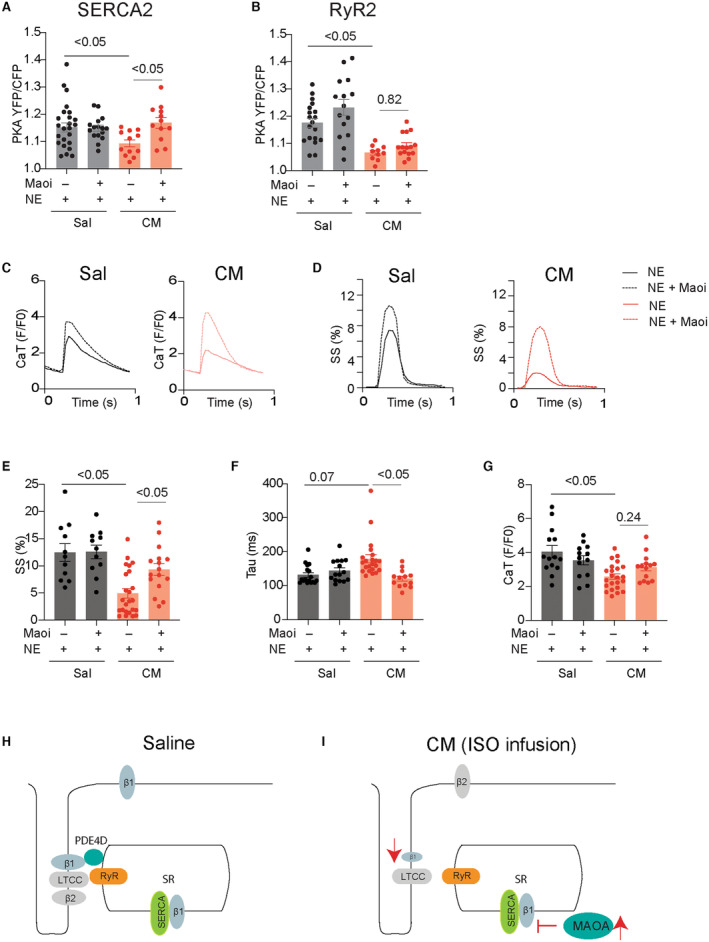

Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidase Rescues the β1AR‐Induced PKA Activity at the SERCA2a Complexes in Cardiomyopathy

Catecholamine‐induced PKA activity at the SERCA2 is subjected to additional regulation by catecholamine transport and metabolism in AVMs. 4 , 5 , 6 MAO‐A (monoamino oxidase A) is upregulated in HF to increase catecholamine metabolism. 35 , 36 We found that the endogenous norepinephrine induced a smaller increase in PKA activity at the SERCA2a and RyR2 in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice relative to saline controls, respectively (Figure 7A and 7B). Inhibition of MAO‐A selectively rescued the norepinephrine‐induced response at the SERCA2a but not the RyR2 (Figure 7A and 7B). Accordingly, norepinephrine induced smaller responses in calcium cycling and sarcomere contractile shortening in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice relative to saline controls (Figure 7C through 7G); inhibiting MAO‐A restored the norepinephrine‐induced calcium cycling and sarcomere contractile shortening (Figure 7C through 7G). These data suggest that the catecholamine‐induced internal β1AR activity at the SERCA2a is suppressed by MAO‐A‐mediated metabolism in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice.

Figure 7. Inhibition of MAO‐A rescues the norepinephrine‐induced PKA activity at the SERCA2a nanodomains and E‐C coupling in AVMs from mice cardiomyopathy.

A and B, FKBP‐AKAR3 and SR‐AKAR3 biosensors were expressed in AVMs isolated from mice after chronic infusion of saline or isoproterenol (CM). Dot plots show the maximal YFP/CFP ratio of FKBP‐AKAR3 and SR‐AKAR3 in AVMs after stimulation with norepinephrine (1 μmol/L) alone or in the presence of monoamine oxidase A inhibitor (MAOi, clorgyline, 5 μmol/L). P values were obtained using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. C through G, AVMs were loaded with fluo‐4 AM dye and paced at 1 Hz. AVMs were then stimulated with norepinephrine (1 μmol/L) alone or in the presence of MAOi (5 μmol/L). CaT decay tau and amplitude and SS were recorded in AVMs after stimulation with norepinephrine. Representative traces show calcium transient and sarcomere shortening. Dot plots show maximal CaT amplitude and decay tau and SS in AVMs after stimulation. Dot plots representing mean±SEM of AVMs from 6 mice. P values were obtained using 2‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. H and I, Working model of the subcellular β1AR signaling desensitization under chronic adrenergic stress. Cardiac β1AR is downregulated at the local RyR2 nanodomains in the mouse cardiomyopathy induced by chronic infusion of isoproterenol. In comparison, MAO‐A‐mediated restriction of the access of catecholamines to the β1AR at the SERCA2a nanodomains leads to impaired local signaling in the mouse cardiomyopathy induced by chronic infusion of isoproterenol. AVM indicates adult ventricular myocyte; β1AR, β1 adrenergic receptor; CaT, calcium transient; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; Cilo, cilostamide; CM, cardiomyopathy; E‐C, excitation‐contraction; EHNA, erythro‐9‐(2‐hydroxy‐3‐nonly)adenine; FKBP‐AKAR3, FK506 binding protein 12.6 anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; FSK, forskolin; IBMX, isobutylmethylxanthine; LTCC, L‐type calcium channel; MAO‐A monoamine oxidase A; MAOi, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NE, norepinephrine; PDE4D, phosphodiesterase 4D; PKA, protein kinase A; Roli, rolipram; RyR2, ryanodine receptor 2; Sal, saline; SERCA2a, (Sarco)endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a; SR‐AKAR3, sarcoplasmic reticulum anchored a kinase activity reporter 3; SS, sarcomere shortening; tau, taurine; and YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized distinct mechanisms for the downregulation of subcellular adrenergic signaling at the PM and RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes in AVMs from the mice after chronic adrenergic stress. The β1AR protein levels and association with LTCC and RyR2 were reduced in hearts after chronic isoproterenol infusion. The β1AR‐PKA signaling and PKA phosphorylation of substrates at these subcellular locations were reduced. Inhibition of PDE3 rescued the adrenergic‐induced PKA activity at the RyR2 complexes and sarcomere contractile shortening in AVMs isolated from the isoproterenol‐infused mice. In comparison, the β1AR association with SERCA2a was increased even though the PKA phosphorylation of phospholamban in the hearts was reduced after chronic isoproterenol infusion. Further studies revealed a reduced endogenous catecholamine (norepinephrine)‐induced PKA activity at the SERCA2a complexes. Inhibition of MAO‐A rescued the norepinephrine‐induced PKA activity at the SERCA2a complexes, calcium cycling, and sarcomere contractile shortening in AVMs from the mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion. Our data uncover distinct mechanisms underlying the downregulation of β1AR signaling at subcellular membranes for cardiac contraction and relaxation and reveal strategies to restore the local PKA activity and cardiac excitation‐contraction coupling in AVMs from the mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion (Figure 7H and 7I).

In AVMs, the RyR2‐ and SERCA2a‐mediated SR calcium release and uptake critically affect myocyte calcium cycling, thus regulating cardiac systolic and diastolic function. 7 , 8 β‐adrenergic signaling increases RyR2 and SERCA2a function by PKA‐dependent phosphorylation of RyR2 and PLB. Despite the elevated sympathetic drive in HF, a reduced PKA phosphorylation of PLB is often observed, leading to impaired SERCA2a function and calcium reuptake to the SR. 6 , 37 , 38 , 39 In comparison, RyR2 usually displays either minimal change or increased activity in HF, leading to increased SR calcium leakage. 31 , 40 , 41 The mechanisms underlying these alterations are not entirely understood. LTCC is tightly coupled to RyR2 at the junctional SR, reflecting the strong interaction between the 2 membranes. 42 Thus, a fraction of RyR2 interacts with LTCC at the junctional SR, forming a local functional unit likely controlled by the β1AR in the vicinity. Previous studies show that cardiac β1AR is not degraded but is redistributed from the PM to intracellular compartments via receptor endocytosis at an early stage of human HF. 43 Similarly, β1AR does not display downregulation at the adaptive stage of HF development in a transverse aortic constriction model. 34 In this study, under chronic infusion with a high concentration of isoproterenol, the reduced β1AR protein level is detected; thus, both the β1AR protein level and distribution could contribute to the reduced receptor association with LTCC and RyR2. Accordingly, we detected reduced PKA activity at the PM and RyR2 complexes, likely in junctional SR. These observations are consistent with the downregulation of β1AR signaling at the PM and RyR2 complexes in rabbit HF models and human HF with reduced ejection fraction. 28 , 34 Whereas others have observed a significant increase in β2AR signaling to the RyR2 complexes in AVMs from a transaortic constriction mouse model and human HF with reduced ejection fraction, 34 we did not observe such changes in the model with chronic isoproterenol infusion. These data indicate that cardiac βAR signaling undergoes dynamic adaptations in a disease model‐ and stage‐dependent manner, likely depending on the activity of the sympathetic drive and other factors such as mechanical stress and disease development. The impaired PKA signaling at the RyR2 complexes likely contributes to impaired ion channel function, calcium cycling, and cardiac contractility.

On the other hand, SERCA2 may be enriched in numerous endoplasmic reticulum/SR membrane domains. Our proximity ligation assay shows an association of SERCA2a with RyR2, which may include the codistribution of both proteins within junctional SR. However, an internal pool of β1AR associates with SERCA2a on the SR but minimally associates with RyR2, 4 indicating that the internal β1AR in association with SERCA2a likely forms a functional unit devoid of RyR2. Moreover, SERCA2a and RyR2 are regulated by different phosphatases and PDEs, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 further supporting the presence of distinct signaling and functional units on the SR. Recent studies show that the SERCA2a‐associated β1AR is critical to regulating PLB phosphorylation, calcium reuptake, and cardiac diastolic relaxation. 4 , 11 Interestingly, we observed an increased association of β1AR with SERCA2a with no reduction of β1AR‐PKA signaling to the SERCA2a complexes in AVMs from mice with chronic isoproterenol infusion. The increased association between β1AR and SERCA2a may be due to altered protein expression and distribution of β1AR in AVMs. For example, the β1AR may be relocated to the SR after endocytosis; alternatively, the newly synthesized β1AR may be functionally retained in the SR to support the local signaling at the SERCA2a nanodomains during the development of HF. 5 The mechanisms underlying the protein expression and distribution of β1AR, RyR2, and SERCA2a remain to be explored in future studies.

Even though the endogenous catecholamines are generally increased, HF still displays a downregulation of SERCA2a function associated with reduced PKA phosphorylation of PLB. The apparent contradictory observations are likely due to the increased expression of MAO‐A in cardiac diseases, 35 , 36 which metabolizes the catecholamines and prevents them from accessing the internal pool of β1AR at the SERCA2a‐associated SR membrane nanodomains. 4 , 5 , 6 We show that inhibition of MAO‐A selectively rescued the norepinephrine‐induced local PKA activity at the SERCA2a but not at the RyR2 complexes. Inhibition of MAO‐A partially rescued calcium cycling and sarcomere contractile shortening in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice. In comparison, isoproterenol is not a perfect MAO‐A substrate, and the isoproterenol responses are not dependent on MAO‐A. These data highlight the alternations of cardiac signaling for impaired cardiac relaxation in isoproterenol infusion‐induced cardiomyopathy.

Among PDE genes expressed in mouse hearts, PDE4 and PDE3 are 2 families linked to the local cAMP and PKA activities at the RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Here, we observed decreases in PDE3A and PDE4D and increases in PDE2A, PDE4A, and PDE4B protein levels. Previous studies also reveal dynamic alteration of PDE isoform activities in different membrane compartments in a rabbit HF model induced by combined aortic insufficiency and stenosis 28 and in a mouse HF model with transaortic constriction. 34 We observed that inhibition of PDE2 and PDE3 but not PDE4 enhanced the isoproterenol‐induced PKA signaling at the RyR2 complexes. Moreover, inhibition of PDE3 also partially rescued calcium cycling and sarcomere shortening in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice, supporting its clinical utility as an inotropic agent. Similarly, in mouse models with transaortic constriction, PDE2, and PDE3 display increased roles in controlling adrenergic signaling at the RyR2 complexes. 34 However, PDE3 inhibitors could potentially promote SR calcium leakage, arrhythmias, and detrimental effects by increasing RyR2 function. 44 Due to unfavorable outcomes of the long‐term usage of these agents in patients, PDE3 inhibitors are limited only to acute human HF therapy. 45 Meanwhile, PDE4 had a diminished role in controlling adrenergic signaling at the RyR2 complexes in AVMs from the isoproterenol‐infused mice, consistent with the reported dissociation between PDE4D3 and RyR2, leading to elevated PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 and calcium leakage in human HF. 17 , 46

The biosensors offer great advantages in probing the dynamic local signaling in AVMs, and our AKAR3 biosensors have been extensively characterized previously. 22 , 23 , 27 However, the biosensor detection has several limitations. One caveat is that they may be mistargeted when overexpressed in AVMs. We should also be more cautious when probing AVMs from mice after chronic isoproterenol infusion, which may have altered membrane structure, such as T‐tubules. 47 We could not rule out the possibility that these biosensors detect minor signals from unintended locations along the secretory pathways. Therefore, FRET data should be corroborated with cellular, biochemical, and functional data. Meanwhile, due to the complexity of the distribution of individual channels and transporters on membrane structures, our study is limited to its biochemical nature and does not address morphological and signaling alterations in individual membrane structures in AVMs.

Conclusion

Nevertheless, in this study, our data collectively support distinct remodeling of adrenergic signaling at the RyR2 and SERCA2a complexes in mouse cardiomyopathy after a chronic infusion of isoproterenol. Our study offers strategies to restore the subcellular cardiac β1AR signaling and contractile function in cardiomyopathy associated with chronic sympathetic stress.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01‐HL147263 and HL162825, Veteran Affair Merit grants IK6BX005753, 01BX002900 and BX005100 (Yang K. Xiang). Ying Wang and Chaoqun Zhu are recipients of American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship. Yang K. Xiang is an established American Heart Association investigator.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Acknowledgments

Bing Xu, Ying Wang, and Yang K. Xiang conceived the idea and designed the experiments; Bing Xu, Ying Wang, Sherif Bahriz, Victoria R. Salemme, Chaoqun Zhu, and Meimi Zhao acquired and analyzed the data, Bing Xu finalized the figures and Yang K. Xiang wrote and revised the article.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.033733

This article was sent to Sakima A. Smith, MD, MPH, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 16.

References

- 1. Rapacciuolo A, Suvarna S, Barki‐Harrington L, Luttrell LM, Cong M, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. Protein kinase a and G protein‐coupled receptor kinase phosphorylation mediates beta‐1 adrenergic receptor endocytosis through different pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35403–35411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305675200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naga Prasad SV, Laporte SA, Chamberlain D, Caron MG, Barak L, Rockman HA. Phosphoinositide 3‐kinase regulates beta2‐adrenergic receptor endocytosis by AP‐2 recruitment to the receptor/beta‐arrestin complex. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:563–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu B, Li M, Wang Y, Zhao M, Morotti S, Shi Q, Wang Q, Barbagallo F, Teoh JP, Reddy GR, et al. GRK5 controls SAP97‐dependent cardiotoxic beta1 adrenergic receptor‐CaMKII signaling in heart failure. Circ Res. 2020;127:796–810. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang Y, Shi Q, Li M, Zhao M, Reddy Gopireddy R, Teoh JP, Xu B, Zhu C, Ireton KE, Srinivasan S, et al. Intracellular beta1‐adrenergic receptors and organic cation transporter 3 mediate phospholamban phosphorylation to enhance cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 2021;128:246–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang Y, Zhao M, Shi Q, Xu B, Zhu C, Li M, Mir V, Bers DM, Xiang YK. Monoamine oxidases desensitize intracellular beta1AR signaling in heart failure. Circ Res. 2021;129:965–967. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Y, Zhao M, Xu B, Bahriz SMF, Zhu C, Jovanovic A, Ni H, Jacobi A, Kaludercic N, Di Lisa F, et al. Monoamine oxidase a and organic cation transporter 3 coordinate intracellular beta1AR signaling to calibrate cardiac contractile function. Basic Res Cardiol. 2022;117:37. doi: 10.1007/s00395-022-00944-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bers DM, Fill M. Coordinated feet and the dance of ryanodine receptors. Science. 1998;281:790–791. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bers DM. Cardiac excitation‐contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zaccolo M, Zerio A, Lobo MJ. Subcellular organization of the cAMP signaling pathway. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73:278–309. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.120.000086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ercu M, Klussmann E. Roles of A‐kinase anchoring proteins and Phosphodiesterases in the cardiovascular system. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2018;5:14. doi: 10.3390/jcdd5010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin TY, Mai QN, Zhang H, Wilson E, Chien HC, Yee SW, Giacomini KM, Olgin JE, Irannejad R. Cardiac contraction and relaxation are regulated by distinct subcellular cAMP pools. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;20:62–73. doi: 10.1038/s41589-023-01381-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nash CA, Wei W, Irannejad R, Smrcka AV. Golgi localized beta1‐adrenergic receptors stimulate Golgi PI4P hydrolysis by PLCepsilon to regulate cardiac hypertrophy. elife. 2019;8:e48167. doi: 10.7554/eLife.48167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richter W, Day P, Agrawal R, Bruss MD, Granier S, Wang YL, Rasmussen SG, Horner K, Wang P, Lei T, et al. Signaling from beta1‐ and beta2‐adrenergic receptors is defined by differential interactions with PDE4. EMBO J. 2008;27:384–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiang Y, Naro F, Zoudilova M, Jin SL, Conti M, Kobilka B. Phosphodiesterase 4D is required for {beta}2 adrenoceptor subtype‐specific signaling in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:909–914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405263102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Arcangelis V, Liu R, Soto D, Xiang Y. Differential association of phosphodiesterase 4D isoforms with beta2‐adrenoceptor in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33824–33832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fu Q, Kim S, Soto D, De Arcangelis V, DiPilato L, Liu S, Xu B, Shi Q, Zhang J, Xiang YK. A long lasting beta1 adrenergic receptor stimulation of cAMP/protein kinase a (PKA) signal in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14771–14781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.542589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lehnart SE, Wehrens XH, Reiken S, Warrier S, Belevych AE, Harvey RD, Richter W, Jin SL, Conti M, Marks AR. Phosphodiesterase 4D deficiency in the ryanodine‐receptor complex promotes heart failure and arrhythmias. Cell. 2005;123:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beca S, Helli PB, Simpson JA, Zhao D, Farman GP, Jones PP, Tian X, Wilson LS, Ahmad F, Chen SR, et al. Phosphodiesterase 4D regulates baseline sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and cardiac contractility, independently of L‐type Ca2+ current. Circ Res. 2011;109:1024–1030. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.250464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Movsesian M, Ahmad F, Hirsch E. Functions of PDE3 isoforms in cardiac muscle. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2018;5:10. doi: 10.3390/jcdd5010010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahmad F, Shen W, Vandeput F, Szabo‐Fresnais N, Krall J, Degerman E, Goetz F, Klussmann E, Movsesian M, Manganiello V. Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2 (SERCA2) activity by phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A) in human myocardium: phosphorylation‐dependent interaction of PDE3A1 with SERCA2. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:6763–6776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.638585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh A, Redden JM, Kapiloff MS, Dodge‐Kafka KL. The large isoforms of A‐kinase anchoring protein 18 mediate the phosphorylation of inhibitor‐1 by protein kinase a and the inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:533–540. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu S, Li Y, Kim S, Fu Q, Parikh D, Sridhar B, Shi Q, Zhang X, Guan Y, Chen X, et al. Phosphodiesterases coordinate cAMP propagation induced by two stimulatory G protein‐coupled receptors in hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6578–6583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117862109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu SB, Zhang J, Xiang YK. FRET‐based direct detection of dynamic protein kinase a activity on the sarcoplasmic reticulum in cardiomyocytes. BBRC. 2010;404:581–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu B, Wang Y, Bahriz SMF, Zhao M, Zhu C, Xiang YK. Probing spatiotemporal PKA activity at the ryanodine receptor and SERCA2a nanodomains in cardomyocytes. Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20:143. doi: 10.1186/s12964-022-00947-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Q, Liu Y, Fu Q, Xu B, Zhang Y, Kim S, Tan R, Barbagallo F, West T, Anderson E, et al. Inhibiting insulin‐mediated beta2‐adrenergic receptor activation prevents diabetes‐associated cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2017;135:73–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang X, Szeto C, Gao E, Tang M, Jin J, Fu Q, Makarewich C, Ai X, Li Y, Tang A, et al. Cardiotoxic and cardioprotective features of chronic beta‐adrenergic signaling. Circ Res. 2013;112:498–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soto D, De Arcangelis V, Zhang J, Xiang Y. Dynamic protein kinase a activities induced by beta‐adrenoceptors dictate signaling propagation for substrate phosphorylation and myocyte contraction. Circ Res. 2009;104:770–779. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barbagallo F, Xu B, Reddy GR, West T, Wang Q, Fu Q, Li M, Shi Q, Ginsburg KS, Ferrier W, et al. Genetically encoded biosensors reveal PKA hyperphosphorylation on the myofilaments in rabbit heart failure. Circ Res. 2016;119:931–943. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buonarati OR, Henderson PB, Murphy GG, Horne MC, Hell JW. Proteolytic processing of the L‐type Ca (2+) channel alpha (1)1.2 subunit in neurons. F1000Res. 2017;6:1166. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11808.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Agrawal V, Fortune N, Yu S, Fuentes J, Shi F, Nichols D, Gleaves L, Poovey E, Wang TJ, Brittain EL, et al. Natriuretic peptide receptor C contributes to disproportionate right ventricular hypertrophy in a rodent model of obesity‐induced heart failure with preserved ejection fraction with pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2019;9:2045894019878599. doi: 10.1177/2045894019895452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang H, Makarewich CA, Kubo H, Wang W, Duran JM, Li Y, Berretta RM, Koch WJ, Chen X, Gao E, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor at serine 2808 is not involved in cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;110:831–840. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xiao H, Li H, Wang JJ, Zhang JS, Shen J, An XB, Zhang CC, Wu JM, Song Y, Wang XY, et al. IL‐18 cleavage triggers cardiac inflammation and fibrosis upon beta‐adrenergic insult. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:60–69. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu J, Steinberg SF. Beta(1)‐adrenergic receptor cleavage and regulation by elastase. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2023;8:976–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2023.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berisha F, Gotz KR, Wegener JW, Brandenburg S, Subramanian H, Molina CE, Ruffer A, Petersen J, Bernhardt A, Girdauskas E, et al. cAMP imaging at ryanodine receptors reveals beta2‐adrenoceptor driven arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2021;129:81–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.318234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaludercic N, Takimoto E, Nagayama T, Feng N, Lai EW, Bedja D, Chen K, Gabrielson KL, Blakely RD, Shih JC, et al. Monoamine oxidase A‐mediated enhanced catabolism of norepinephrine contributes to adverse remodeling and pump failure in hearts with pressure overload. Circ Res. 2010;106:193–202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manni ME, Rigacci S, Borchi E, Bargelli V, Miceli C, Giordano C, Raimondi L, Nediani C. Monoamine oxidase is overactivated in left and right ventricles from ischemic hearts: An intriguing therapeutic target. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4375418. doi: 10.1155/2016/4375418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang B, Wang S, Qin D, Boutjdir M, El‐Sherif N. Diminished basal phosphorylation level of phospholamban in the postinfarction remodeled rat ventricle: role of beta‐adrenergic pathway, G(i) protein, phosphodiesterase, and phosphatases. Circ Res. 1999;85:848–855. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.85.9.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang W, Zhu W, Wang S, Yang D, Crow MT, Xiao RP, Cheng H. Sustained beta1‐adrenergic stimulation modulates cardiac contractility by Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2004;95:798–806. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145361.50017.aa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang T, Guo T, Mishra S, Dalton ND, Kranias EG, Peterson KL, Bers DM, Brown JH. Phospholamban ablation rescues sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) handling but exacerbates cardiac dysfunction in CaMKIIdelta(C) transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2010;106:354–362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005;97:1314–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pereira L, Cheng H, Lao DH, Na L, van Oort RJ, Brown JH, Wehrens XH, Chen J, Bers DM. Epac2 mediates cardiac beta1‐adrenergic‐dependent sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak and arrhythmia. Circulation. 2013;127:913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.12.148619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Williams LT, Jones LR. Specific binding of the calcium antagonist [3H]nitrendipine to subcellular fractions isolated from canine myocardium. Evidence for high affinity binding to ryanodine‐sensitive sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5344–5347. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(20)81893-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perrino C, Naga Prasad SV, Schroder JN, Hata JA, Milano C, Rockman HA. Restoration of beta‐adrenergic receptor signaling and contractile function in heart failure by disruption of the betaARK1/phosphoinositide 3‐kinase complex. Circulation. 2005;111:2579–2587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Toma M, Starling RC. Inotropic therapy for end‐stage heart failure patients. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2010;12:409–419. doi: 10.1007/s11936-010-0090-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maack C, Eschenhagen T, Hamdani N, Heinzel FR, Lyon AR, Manstein DJ, Metzger J, Papp Z, Tocchetti CG, Yilmaz MB, et al. Treatments targeting inotropy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3626–3644. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bellinger AM, Reiken S, Dura M, Murphy PW, Deng SX, Landry DW, Nieman D, Lehnart SE, Samaru M, LaCampagne A, et al. Remodeling of ryanodine receptor complex causes "leaky" channels: a molecular mechanism for decreased exercise capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2198–2202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711074105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guo A, Zhang C, Wei S, Chen B, Song LS. Emerging mechanisms of T‐tubule remodelling in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:204–215. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files.