Abstract

Background

Acute mesenteric ischemia is rare, and few large‐scale trials have evaluated endovascular therapy (EVT) and open surgical revascularization (OS). This study aimed to assess clinical outcomes after EVT or OS for acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion and identify predictors of mortality and bowel resection.

Methods and Results

Data from the Japanese Registry of All Cardiac and Vascular Diseases‐Diagnosis Procedure Combination (JROAD‐DPC) database from April 2012 to March 2020 were retrospectively analyzed. Overall, 746 patients with acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion who underwent revascularization were classified into 2 groups: EVT (n=475) or OS (n=271). The primary clinical outcome was in‐hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes were bowel resection, bleeding complications (transfusion or endoscopic hemostasis), major adverse cardiovascular events, hospitalization duration, and cost. The in‐hospital death or bowel resection rate was ≈30%. In‐hospital mortality (22.5% versus 21.4%, P=0.72), bowel resection (8.2% versus 8.5%, P=0.90), and major adverse cardiovascular events (11.6% versus 9.2%, P=0.32) were comparable between the EVT and OS groups. Hospitalization duration in the EVT group was 6 days shorter than that in the OS group, and total hospitalization cost was 0.88 million yen lower. Interaction analyses revealed that EVT and OS had no significant difference in terms of in‐hospital death in patients with thromboembolic and atherothrombotic characteristics. Advanced age, decreased activities of daily living, chronic kidney disease, and old myocardial infarction were significant predictive factors for in‐hospital mortality. Diabetes was a predictor of bowel resection after revascularization.

Conclusions

EVT was comparable to OS in terms of clinical outcomes in patients with acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Some predictive factors for mortality or bowel resection were obtained.

Registration

URL: www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/; Unique Identifier: UMIN000045240.

Keywords: acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion, bowel resection, endovascular therapy, in‐hospital mortality, open surgical revascularization

Subject Categories: Quality and Outcomes, Vascular Disease, Revascularization

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AMI

acute mesenteric ischemia

- EVT

endovascular therapy

- JROAD‐DPC

Japanese Registry of All Cardiac and Vascular Diseases‐Diagnosis Procedure Combination

- OS

open surgical revascularization

- SMA

superior mesenteric artery

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Endovascular therapy was not significantly associated with in‐hospital death compared with open surgical revascularization, not only in patients with atherothrombotic characteristics but also in those with thromboembolic characteristics.

Prognostic predictors for in‐hospital mortality were advanced age, low activities of daily living, chronic kidney disease, and old myocardial infarction.

Diabetes was a predictor of bowel resection after revascularization.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Endovascular therapy may be a feasible alternative to open surgical revascularization, potentially impacting clinical practice as a less invasive option for managing patients with acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion.

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) causes acute intestinal ischemia due to atherothrombosis or thromboembolism, resulting in high mortality rates and necessitating bowel resection. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 The primary symptom of AMI is severe abdominal pain, which, if left untreated, can progress to intestinal necrosis and peritonitis within a few days. 1 Acute thromboembolic occlusion of the mesenteric arteries most commonly affects the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). 5 Symptomatic acute occlusions of the celiac artery and inferior mesenteric artery are rare and seldom induce intestinal infarction. 6 , 7 Revascularization and resection of necrotic intestines are important treatments for intestinal ischemia, with endovascular therapy (EVT) and open surgery (open SMA embolectomy, thromboendarterectomy with patch angioplasty, or bypass surgery) being common revascularization methods. Several studies have shown that revascularization significantly improves 30‐day mortality. Additionally, EVT is reported to be superior to open surgery in terms of 30‐day mortality and bowel resection rates. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Recent guidelines recommend EVT as a primary revascularization for patients with AMI, and EVT became widespread in clinical practice. 5 AMI has an annual incidence of <0.1% 8 and is a rare disease. 9 , 10 Few large‐scale prospective trials have compared EVT and open surgical revascularization (OS). 11 , 12 However, whether EVT is a feasible treatment for patients with atherothrombotic or thromboembolic characteristics is still controversial. Furthermore, predictive factors for clinical outcomes after revascularization have not been adequately reported.

This study aimed to investigate a trend of primary treatment for patients with acute SMA occlusion (SMAO) and compare clinical outcomes of those who underwent EVT or OS. Additionally, we sought to assess predictive factors associated with mortality or bowel resection after revascularization.

Methods

Data Source

All data analyzed during this study were provided by the Japanese Circulation Society under license/by permission; the corresponding author will share this data set upon reasonable request and with permission from the Japanese Circulation Society. This retrospective observational study utilized data from the Japanese Registry of All Cardiac and Vascular Diseases‐Diagnosis Procedure Combination (JROAD‐DPC) database. The JROAD study included a nationwide survey assessing the contemporary landscape of cardiovascular practice, excluding cerebral vascular disease. This survey, initiated in 2004, was conducted collaboratively by the Japanese Circulation Society and National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center Hospital at Japanese Circulation Society‐certified cardiovascular specialist training facilities and related institutions. The JROAD‐DPC database complements the JROAD study using DPC data from the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination/Per‐Diem Payment System, which has been previously used for various studies. 13 , 14 , 15 In addition, it includes patient information on age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, primary diagnoses, comorbidities, drugs, complications, treatment procedures, length of stay, and admission and discharge statuses, categorized according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) codes.

Study Design

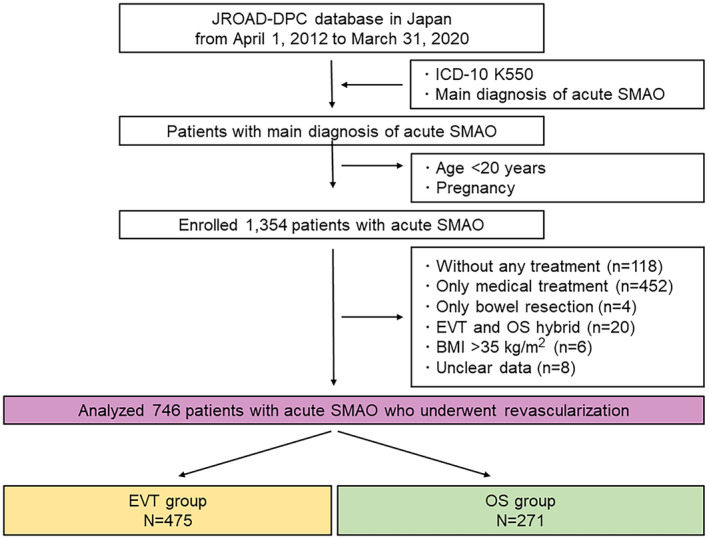

Figure 1 depicts the patient enrollment flowchart. We extracted the data of patients with code ICD‐10 K550 and a main diagnosis of acute SMAO from the JROAD database, 16 which enrolled patients between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2020. Patients aged <20 years and those who were pregnant were excluded. Overall, 1354 patients with a main diagnosis of SMAO were enrolled. We excluded 608 patients according to exclusion criteria and finally analyzed 746 patients with acute SMAO who underwent EVT or OS. We divided these patients into EVT and OS groups. EVT included percutaneous transcatheter thrombectomy, balloon dilatation, or stenting. Patients with operation codes for percutaneous embolectomy (K6082, K616‐5) or angioplasty using a balloon or stent (K616) were categorized as having undergone EVT; those with operation codes for open SMA embolectomy (K6081), thromboendarterectomy with patch angioplasty (K6103, K6105), or bypass surgery (K6143) were categorized as having undergone OS; and those with operation codes K716, K716‐21, K719, K7192, K7322, or K7401 were categorized as having undergone bowel resection.

Figure 1. Patient flowchart.

BMI indicates body mass index; EVT, endovascular therapy; ICD‐10, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; JROAD‐DPC, Japanese Registry of All Cardiac and Vascular Diseases‐Diagnosis Procedure Combination; OS, open surgical revascularization; and SMAO, superior mesenteric artery occlusion.

At first, we investigated each treatment's contemporary trends and clinical outcomes for patients with acute SMAO and compared the EVT and OS groups using unadjusted and multivariable analyses. Next, we evaluated the predictive factors for in‐hospital mortality or bowel resection after revascularization.

Definitions

Patients' background information included age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, facility scale, comorbidities, cognitive function, and activities of daily living (ADL) at admission. Patients with comorbid dementia (ICD‐10 codes F00–F03) were defined as having cognitive decline. Patients who scored a full 20 points on the Barthel Index at admission were categorized as having independent ADL, 17 whereas all other patients were classified as having ADL impairment. Hospitals with 20 to 100, 100 to 450, and 450 to 1600 beds were classified as small, medium, and large facilities, respectively. Patients with a Brinkman Index score of 0 were categorized as “never smokers,” whereas all others were categorized as “smokers.” Patients with unusually high Brinkman Index scores (≥9999) were defined as missing values. 18

Outcomes

The primary clinical outcome encompassed in‐hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes encompassed bowel resection, bleeding complications (transfusion and endoscopic hemostasis), and major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, coronary intervention, heart failure, stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage), and hospitalization duration and total hospitalization cost.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol adhered to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (approval number ERB‐C‐2184‐2), and was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (Identification: UMIN000045240). All relevant information was disclosed, and participants were allowed to opt out.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were assessed for normality distribution using the Anderson‐Darling test. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as the mean±SD. Non‐normally distributed continuous variables are presented as the median with the interquartile range. Categorical variables are presented as count and percentage. The χ2 test was used to compare the proportions of nominal variables, whereas the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was used to compare continuous variables between groups. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables related to clinical outcomes: the results are presented as odds ratio and 95% CI. Multivariable regression analysis, using a univariate screening, was performed with EVT and covariates to evaluate the significant predictors associated with clinical outcomes of revascularization. The threshold for inclusion and exclusion in the model was P=0.30.

Multivariable regression analysis was used to determine the interaction effect between revascularization and covariates. We excluded all patients with missing data in the analysis of variables and described their value in each table. Statistical significance was defined as P <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP pro16 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Annual Trend in Primary Treatment Strategies for Acute SMAO

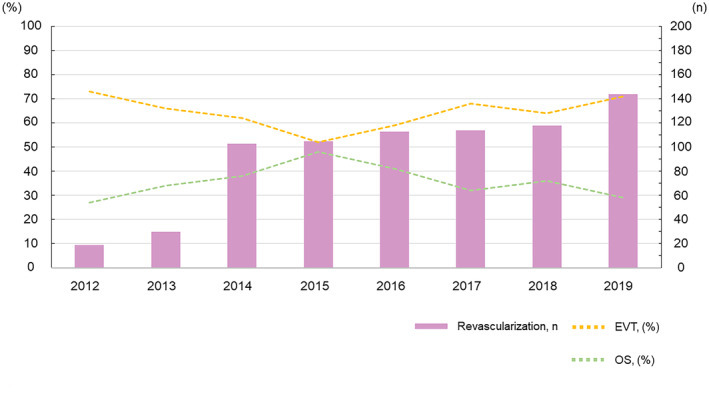

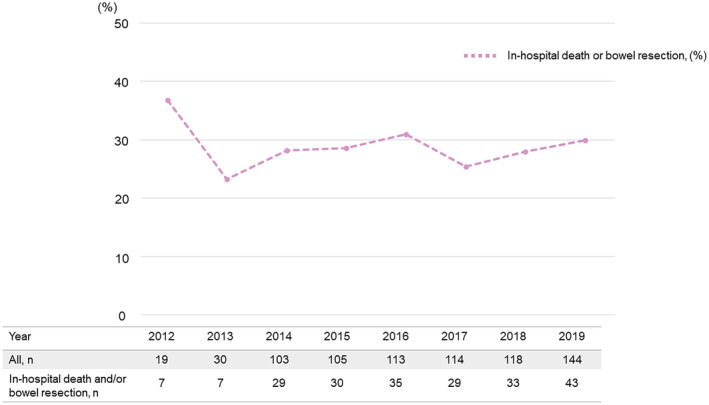

The EVT and OS groups comprised 475 and 271 patients, respectively (Figure 1). The EVT group underwent procedures such as percutaneous embolectomy (n=268) or angioplasty using a balloon or stent (n=218). The OS group underwent procedures such as open SMA embolectomy (n=212), thromboendarterectomy with patch angioplasty (n=36), or bypass surgery (n=25). Figure 2 illustrates the trends in revascularization strategies for patients with acute SMAO. Revascularization has steadily increased as the primary treatment for acute SMAO since 2012 in Japan; EVT accounted for >70% of revascularization cases. Figure 3 shows the annual trend of the in‐hospital death or bowel resection rate (≈30%), which has not significantly fluctuated since 2012.

Figure 2. Revascularization trend for patients with acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion.

EVT indicates endovascular therapy; and OS, open surgical revascularization.

Figure 3. Trend in in‐hospital mortality or bowel resection rate in the revascularization group.

The straight line shows the annual in‐hospital death or bowel resection rate.

Comparison Between the EVT and OS Groups

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the EVT and OS groups. Details of the malignancies in both groups are shown in Table S1. Regarding the use of intraoperative and postoperative medications, no significant differences in oral anticoagulation (warfarin or direct oral anticoagulant), oral antiplatelet, and intravenous anticoagulation (heparin or argatroban) therapies were observed between the 2 groups. However, thrombolytic therapy (urokinase) was more common among patients in the EVT group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Postoperative Medical Treatment in the EVT and OS Groups

| Revascularization (n=746) | EVT (n=475) | OS (n=271) | Missing values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 77 (69–84) | 76 (69–84) | 77 (69–85) | – |

| Male, n (%) | 447 (59.9) | 286 (60.2) | 161 (59.4) | – |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.4 (20.1–25.2) | 22.5 (20.1–25.5) | 22.0 (20.2–24.4) | 73 (9.8) |

| ADL full, n (%) | 539 (74.7) | 352 (76.2) | 187 (71.9) | 24 (3.2) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 131 (19.7) | 81 (19.2) | 50 (20.6) | 80 (10.7) |

| Past history | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 265 (35.5) | 158 (33.3) | 107 (39.5) | – |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 121 (16.2) | 74 (15.6) | 47 (17.3) | – |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 74 (9.9) | 49 (10.3) | 25 (9.2) | – |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 59 (7.9) | 37 (7.8) | 22 (8.1) | – |

| Hemodialysis, n (%) | 33 (4.4) | 20 (4.2) | 13 (4.8) | – |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 22 (2.9) | 16 (3.4) | 6 (2.2) | – |

| Old myocardial infarction, n (%) | 33 (4.4) | 22 (4.6) | 11 (4.1) | – |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 79 (10.6) | 53 (11.2) | 26 (9.6) | – |

| Atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, n (%) | 345 (46.3) | 214 (45.1) | 131 (48.3) | – |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism/deep vein thrombosis, n (%) | 9 (1.2) | 6 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | – |

| Malignancies,* n (%) | 44 (5.9) | 23 (4.8) | 21 (7.8) | – |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 7 (0.9) | 4 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | – |

| Smoking, n (%) | 370 (49.6) | 231 (48.6) | 139 (51.3) | – |

| Intraoperative and postoperative medical therapy | ||||

| Oral anticoagulant therapy, n (%) | 513 (68.8) | 323 (68.0) | 190 (70.1) | – |

| Oral antiplatelet therapy, n (%) | 201 (26.9) | 133 (28.0) | 68 (25.1) | – |

| Intravenous anticoagulant therapy, n (%) | 743 (99.6) | 472 (99.4) | 271 (100) | – |

| Thrombolytic therapy, n (%) | 329 (44.1) | 298 (62.7) | 31 (11.4) | – |

Age and BMI are presented as median (interquartile range). ADL indicates activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; EVT, endovascular therapy; and OS, open surgical revascularization.

Details of malignant organs in both groups are shown in Table S1.

No significant differences in the rates of in‐hospital mortality, bowel resection, major adverse cardiovascular events, and endoscopic hemostasis were observed between the 2 groups. However, patients in the EVT group required significantly fewer transfusions after revascularization than those in the OS group. Additionally, hospitalization duration in the EVT group was 6 days shorter than that in the OS group. Total hospitalization cost was 0.88 million yen lower (Table 2).

Table 2.

In‐Hospital Clinical Outcomes of Patients in the EVT and OS Groups

| Revascularization (n=746) | EVT (n=475) | OS (n=271) | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause in‐hospital mortality, n (%) | 165 (22.1) | 107 (22.5) | 58 (21.4) | 0.72 | 1.07 | 0.74–1.53 |

| Bowel resection, n (%) | 62 (8.2) | 39 (8.2) | 23 (8.5) | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.53–1.65 |

| Bleeding complications, n (%) | ||||||

| Transfusion | 200 (26.8) | 95 (20.0) | 105 (38.8) | <0.0001 | 0.40 | 0.28–0.55 |

| Endoscopic hemostasis | 7 (0.9) | 3 (0.6) | 4 (1.5) | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.09–1.91 |

| MACEs, n (%) | 80 (10.7) | 55 (11.6) | 25 (9.2) | 0.32 | 1.29 | 0.78–2.12 |

| Myocardial infarction | 8 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.23–4.01 |

| Coronary intervention | 16 (2.1) | 11 (2.3) | 5 (1.9) | 0.67 | 1.26 | 0.43–3.67 |

| Heart failure | 35 (4.7) | 24 (5.1) | 11 (4.1) | 0.54 | 1.26 | 0.61–2.61 |

| Stroke | 23 (3.1) | 17 (3.6) | 6 (2.2) | 0.30 | 1.64 | 0.64–4.21 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.08–4.06 |

| Hospitalization duration (d) | 20 (11–36) | 18 (10–31) | 24 (14–46) | <0.0001 | ||

| Total cost (×106, yen) | 1.93 (1.21–3.35) | 1.62 (1.07–2.92) | 2.50 (1.71–3.95) | <0.0001 | ||

Total cost during hospitalization is presented as median (interquartile range). EVT indicates endovascular therapy; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; OR, odds ratio; and OS, open surgical revascularization.

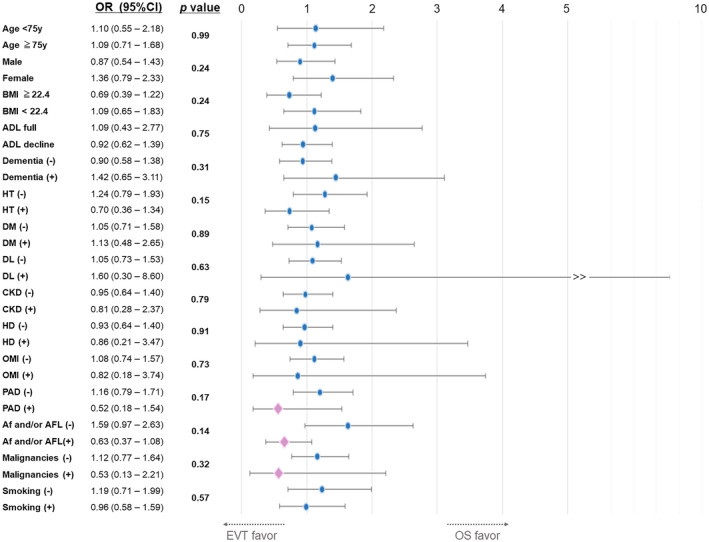

Figure 4 shows the interaction effect of revascularization and covariates on in‐hospital mortality. No significant interaction was observed between the EVT and OS groups. This result demonstrated that EVT was not significantly associated with in‐hospital mortality not only in patients with atherothrombotic factors such as peripheral arterial disease (PAD), hemodialysis, or diabetes, but also in those with thromboembolic factors such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or malignancies.

Figure 4. Interaction effect test for mortality between revascularization and covariates.

The P values of the interaction test for CVD and PE/DVT were 0.24 and 0.55, respectively. ADL indicates activities of daily living; Af, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; DL, dyslipidemia; EVT, endovascular therapy; HD, hemodialysis; HT, hypertension; OMI, old myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; OS, open surgical revascularization; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; and PE/DVT, pulmonary thromboembolism/deep vein thrombosis.

Table 3 presents the univariate logistic regression analysis results of in‐hospital mortality and bowel resection in the revascularization group. Multivariable regression analysis revealed that EVT was not a significant predictor of in‐hospital mortality and bowel resection. Conversely, advanced age, low ADL, chronic kidney disease, and old myocardial infarction were significant predictors of in‐hospital mortality, whereas diabetes was a significant predictor of bowel resection (Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariable Regression Analysis of Variables Associated With In‐Hospital Mortality After Revascularization

| In‐hospital mortality | Univariate | Multivariable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | P value | Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (per 10 y) | −5.40 | 1.70 | 1.41–2.04 | <0.0001 | 0.47 | 1.60 | 1.24–2.07 | 0.0004 |

| Male | −0.97 | 0.60 | 0.43–0.85 | 0.005 | −0.16 | 0.85 | 0.53–1.36 | 0.51 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.14 | 0.93 | 0.89–0.98 | 0.009 | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 | 0.43 |

| Decline in ADL | −2.04 | 2.60 | 1.59–4.27 | 0.0001 | 0.60 | 1.82 | 1.04–3.20 | 0.04 |

| Dementia | −1.32 | 1.64 | 1.07–2.51 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.71–2.02 | 0.49 |

| Hypertension | −1.09 | 0.59 | 0.40–0.87 | 0.008 | −0.18 | 0.83 | 0.52–1.34 | 0.45 |

| Diabetes | −1.29 | 1.20 | 0.76–1.89 | 0.44 | ‐ | – | – | – |

| Dyslipidemia | −1.29 | 0.40 | 0.19–0.85 | 0.02 | −0.85 | 0.43 | 0.17–1.10 | 0.08 |

| Chronic kidney disease | −1.37 | 3.11 | 1.80–5.37 | <0.0001 | 1.16 | 3.18 | 1.43–7.04 | 0.0045 |

| Hemodialysis | −1.33 | 3.56 | 1.76–7.22 | 0.0006 | 0.49 | 1.63 | 0.57–4.62 | 0.36 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | −1.25 | 0.78 | 0.26–2.33 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | 1.23 | 0.33–4.55 | 0.76 |

| Old myocardial infarction | −1.29 | 1.81 | 0.86–3.82 | 0.12 | 1.19 | 3.30 | 1.29–8.41 | 0.01 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | −1.26 | 1.04 | 0.60–1.82 | 0.88 | – | – | – | – |

| Atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter | −1.12 | 0.72 | 0.51–1.03 | 0.07 | −0.36 | 0.69 | 0.44–1.09 | 0.11 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism/deep vein thrombosis | −1.26 | 1.01 | 0.21–4.89 | 0.99 | – | – | – | – |

| Malignancies | −1.26 | 1.04 | 0.50–2.15 | 0.92 | – | – | – | – |

| Chemotherapy | −1.26 | 1.41 | 0.27–7.35 | 0.68 | – | – | – | – |

| Smoking | −1.25 | 0.97 | 0.69–1.38 | 0.88 | – | – | – | – |

| EVT | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.74–1.53 | 0.94 | – | – | – | – |

ADL indicates activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; EVT, endovascular therapy; and OR, odds ratio.

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariable Regression Analysis of Variables Associated With Bowel Resection After Revascularization

| Bowel resection | Univariate | Multivariable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | P value | Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (per 10 y) | −2.33 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.24 | 0.93 | – | – | – | – |

| Male | −2.35 | 0.92 | 0.54–1.56 | 0.76 | – | – | – | – |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | −0.82 | 0.93 | 0.87–1.00 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.87–1.00 | 0.06 |

| Decline in ADL | −2.35 | 0.93 | 0.51–1.69 | 0.81 | – | – | – | – |

| Dementia | −2.41 | 0.92 | 0.45–1.88 | 0.82 | – | – | – | – |

| Hypertension | −2.30 | 0.72 | 0.41–1.28 | 0.27 | −0.20 | 0.82 | 0.45–1.48 | 0.50 |

| Diabetes | −2.58 | 2.31 | 1.28–4.15 | 0.008 | 0.83 | 2.29 | 1.24–4.22 | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia | −2.40 | 0.97 | 0.40–2.34 | 0.95 | – | – | – | – |

| Chronic kidney disease | −2.42 | 1.28 | 0.53–3.10 | 0.59 | – | – | – | – |

| Hemodialysis | −2.42 | 1.56 | 0.53–4.58 | 0.42 | – | – | – | – |

| Cerebrovascular disease | −2.39 | 0.52 | 0.07–3.91 | 0.52 | – | – | – | – |

| Old myocardial infarction | −2.42 | 1.56 | 0.53–4.58 | 0.42 | – | – | – | – |

| Peripheral arterial disease | −2.41 | 1.08 | 0.47–2.47 | 0.85 | – | – | – | – |

| Atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter | −2.20 | 0.61 | 0.36–1.06 | 0.08 | −0.39 | 0.68 | 0.38–1.20 | 0.18 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism/deep vein thrombosis | −2.41 | 1.39 | 0.17–11.3 | 0.76 | – | – | – | – |

| Malignancies | −2.41 | 1.11 | 0.38–3.21 | 0.85 | – | – | – | – |

| Chemotherapy | −2.41 | 1.85 | 0.22–15.6 | 0.57 | – | – | – | – |

| Smoking | −2.56 | 1.35 | 0.80–2.28 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 1.32 | 0.76–2.28 | 0.32 |

| EVT | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.56–1.65 | 0.90 | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.65–2.02 | 0.63 |

ADL indicates activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index; EVT, endovascular therapy; and OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This retrospective study demonstrated that EVT had clinical outcomes comparable to those of OS in patients with acute SMAO and was advantageous in the hospitalization duration and cost. EVT had no significant difference in in‐hospital death compared with OS in patients with atherothrombotic or thromboembolic characteristics. In addition, prognostic predictors of in‐hospital mortality were advanced age, low ADL, chronic kidney disease, and old myocardial infarction. Notably, diabetes was a predictor of bowel resection after revascularization.

The mortality rate for AMI ranges from 50% to 70%. 19 , 20 When appropriately revascularized, the 30‐day mortality was 16% to 39% with EVT and 39% to 50% with surgical revascularization. 2 , 3 , 21 , 22 , 23 Additionally, the bowel resection rate for AMI is reportedly 14.4% to 33.4%. 4 , 24 In particular, intestinal survival within 12 hours of onset in all patients has been reported. 25 , 26 In the present study, many patients did not undergo primary revascularization and received no or only medical treatment. We speculated that they could not, or did not wish to, undergo revascularization because of critical conditions or serious health history. Acute SMAO is still associated with a high mortality rate in Japan; nonetheless, we suggested that the mortality or bowel resection rate in patients who underwent primary revascularization was similar or lower compared with that previously reported. 2 , 3 , 4 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 It has been reported that atherothrombosis had a worse prognosis than embolism overall, 9 , 27 , 28 and embolism was more often the pathogenesis of SMAO than atherothrombosis in Asian patients. 29 Recent guidelines have recommended EVT or OS for patients with acute SMAO; therefore, the number of revascularization cases has increased, 5 and revascularization techniques have recently improved with the development of devices. Furthermore, in Japan, early diagnosis using computed tomography angiography (CTA) and revascularization are available 24 hours in most institutions. Because patients with acute SMAO in nonspecialized facilities were not included in the JROAD‐DPC database, it is possible that some critical patients who required bowel resection were not reflected in this study, which may have contributed to the low bowel resection rate. We speculate that these reasons may have contributed to the good clinical prognosis such as in‐hospital mortality or bowel resection in patients with acute SMAO in this study. Furthermore, we believe that the clinical prognosis for patients with acute SMAO who can undergo appropriate revascularization may be becoming more favorable.

In previous studies, the OS group had higher mortality and bowel resection rates than the EVT group. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 21 , 24 However, because these studies were not randomized trials, demonstration of the superiority of both revascularization strategies was limited. In addition, it is suggested that the OS group might have a more severely affected patient population owing to patient selection bias. 1 In the present study, although it was a retrospective trial, there were no significant differences between the EVT and OS groups in patient characteristics, including age, ADL, and cognition, and in other factors associated with the severity of acute SMAO. Multivariable regression analysis also showed no prognostic difference in in‐hospital mortality or bowel resection rate between the EVT and OS groups. Furthermore, EVT demonstrated significantly lower hospitalization duration and cost, underscoring its usefulness. In Japan, the number of EVT cases has increased compared with OS cases, and EVT has become possible to perform for critical patients with acute SMAO owing to its technical improvement and devices. Therefore, we speculated that the in‐hospital mortality and bowel resection rate in the EVT group were similar to those in the OS group, because the patient population in the EVT group might include a more severely ill population compared with previous studies.

The results of the interaction between revascularization and covariates suggested that EVT might be feasible for patients with peripheral artery disease, hemodialysis, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, malignancies, pulmonary thromboembolism, or deep vein thrombosis. Studies have shown that the prognostic values of EVT and surgical revascularization are equivalent in patients with embolism, 3 , 4 whereas EVT is more advantageous in those with atherothrombosis. Atherothrombosis causes more extensive intestinal necrosis 9 , 27 , 28 and has a worse prognosis than embolism. Atherothrombotic cases are more likely to occlude proximally, and those with hemodialysis, diabetes, or peripheral artery disease are more likely to present infarction in multiple segments. Generally, atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter or malignancies are associated with arteriovenous embolisms, and the culprit lesion often exhibits a high thrombus volume. Nevertheless, advancements in EVT technology, including the availability of large‐diameter thrombectomy devices and stents, may make EVT more effective for treating embolic patients with high thrombus volumes.

The current study identified the factors contributing to poor prognosis of in‐hospital mortality: advanced age, low ADL, and chronic kidney disease. Older patients and those with low ADL are considered to have a worse prognosis because of their poor general condition or nutritional condition. Furthermore, we speculate that impaired kidney function following reperfusion injury after revascularization may be associated with in‐hospital death in patients with chronic kidney disease. In addition, patients with old myocardial infarction may be more prone to cardiogenic complications, such as cardiogenic shock or heart failure, during hospitalization because of low cardiac function. We found that diabetes was a predictive factor for bowel resection after revascularization. Diabetes is often accompanied by microcirculatory disturbances; therefore, we speculate that patients with diabetes may be more prone to microvascular ischemia from microvasculature atherosclerotic lesions and to more extensive intestinal necrosis. Furthermore, revascularization after acute SMAO often leads to further blood flow reduction relative to the initial condition, which may contribute to intestinal ischemia in addition to pre‐existing microcirculatory disturbances.

Although the long‐term survival rate after EVT was higher than that after surgical revascularization in patients with acute SMAO, survival rates in both groups were <50%. Studies 2 , 23 have shown that advanced age, bowel resection, and short bowel syndrome are associated factors for long‐term outcomes. Aggressive revascularization that avoids bowel resection may improve the prognosis. Before EVT was available, AMI could only be reliably diagnosed through laparotomy. Treatment initially focused on removing the necrotic intestine as part of damage control, followed by subsequent surgical revascularization. 24 , 30 Early diagnosis contributes to improved prognosis, 31 , 32 , 33 and CTA's high sensitivity and specificity for SMAO 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 enable early diagnosis. Furthermore, the evolution of CTA and the availability of 24‐hour imaging facilitate SMAO diagnosis. 40 The importance of CTA has increased, and contrast angiography is associated with improved life expectancy, even with poor renal function. 41 Therefore, it was recommended to initially restore blood flow after diagnosis by CTA and then assess intestinal viability and perform resection of the necrotic intestine. 42 Hence, we believe that accurate diagnosis by CTA, lesion nature and morphology evaluation, or successful revascularization for intestinal ischemia improves intestinal salvage or survival rate for patients with acute SMAO.

Overall, we believe that primary revascularization may improve clinical outcomes in patients with acute SMAO with an indication for revascularization. Therefore, in addition to surgical treatment options, treatment at a facility with an adequate knowledge of EVT is preferable.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis was based on the JROAD‐DPC database, and no detailed data of laboratory examinations, imaging findings, duration from onset, clinical symptoms on admission, procedure, and devices of EVT and OS were available. Thus, we could not evaluate the association of these factors with clinical outcomes such as death, bowel resection, bleeding complications, or major adverse cardiovascular events. Second, although the exploratory laparotomy was recommended in a recent guideline, 5 the timing of that could not be identified from the JROAD‐DPC database. Therefore, it was difficult to define a second‐look surgery and perform an accurate analysis. These limitations are future issues for the JROAD‐DPC study. It is hoped that these limitations can be solved and further evidence of this study can be established. Third, the reasons for opting for only medication treatment over revascularization and the factors influencing the choice between EVT and surgical revascularization are unknown. This lack of information could have introduced bias in treatment selection. In the future, prospective randomized comparative trials involving patients with SMAO are warranted. Fourth, although DPC data must be verified by physicians and are highly credible, they may contain errors. Fifth, the JROAD study utilized a national database, reflecting real‐world outcomes in our country; however, it may not accurately represent conditions at nonspecialized facilities.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that clinical outcomes of EVT are comparable to those of OS in patients with acute SMAO, and EVT proved advantageous in terms of hospitalization cost and duration. EVT may be feasible for those with atherothrombotic or thromboembolic characteristics. Advanced age, low ADL, CKD, and old myocardial infarction are predictors of in‐hospital death, and diabetes is a predictor of bowel resection after revascularization.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude for the invaluable assistance and support received from all project members, as well as the dedicated staff at the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center Hospital and participating institutions in the JROAD.

This manuscript was sent to John S. Ikonomidis, MD, PhD, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.124.035017

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schermerhorn ML, Giles KA, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, Pomposelli FB. Mesenteric revascularization: management and outcomes in the United States, 1988–2006. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:341–348.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Block TA, Acosta S, Björck M. Endovascular and open surgery for acute occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arthurs ZM, Titus J, Bannazadeh M, Eagleton MJ, Srivastava S, Sarac TP, Clair DG. A comparison of endovascular revascularization with traditional therapy for the treatment of acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:698–704; discussion 704–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beaulieu RJ, Arnaoutakis KD, Abularrage CJ, Efron DT, Schneider E, Black JH. Comparison of open and endovascular treatment of acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.06.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Björck M, Koelemay M, Acosta S, Bastos Goncalves F, Kölbel T, Kolkman JJ, Lees T, Lefevre JH, Menyhei G, Oderich G, et al. Editor's choice—management of the diseases of mesenteric arteries and veins: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:460–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Acosta S, Ogren M, Sternby NH, Bergqvist D, Bjorck M. Fatal nonocclusive mesenteric ischaemia: population‐based incidence and risk factors. J Intern Med. 2006;259:305–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Acosta S, Ogren M, Sternby NH, Bergqvist D, Björck M. Clinical implications for the management of acute thromboembolic occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery: autopsy findings in 213 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:516–522. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154269.52294.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kärkkäinen JM, Lehtimäki TT, Manninen H, Paajanen H. Acute mesenteric ischemia is a more common cause than expected of acute abdomen in the elderly. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1407–1414. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2830-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schoots IG, Koffeman GI, Legemate DA, Levi M, van Gulik TM. Systematic review of survival after acute mesenteric ischaemia according to disease Aetiology. Br J Surg. 2004;91:17–27. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stoney RJ, Cunningham CG. Acute mesenteric ischemia. Surgery. 1993;114:489–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li W, Cao S, Zhang Z, Zhu R, Chen X, Liu B, Feng H. Outcome comparison of endovascular and open surgery for the treatment of acute superior mesenteric artery embolism: a retrospective study. Front Surg. 2022;9:833464. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.833464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atkins MD, Kwolek CJ, LaMuraglia GM, Brewster DC, Chung TK, Cambria RP. Surgical revascularization versus endovascular therapy for chronic mesenteric ischemia: a comparative experience. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1162–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishii M, Seki T, Kaikita K, Sakamoto K, Nakai M, Sumita Y, Nishimura K, Miyamoto Y, Noguchi T, Yasuda S, et al. Association of short‐term exposure to air pollution with myocardial infarction with and without obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28:1435–1444. doi: 10.1177/2047487320904641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakano H, Hamatani Y, Nagai T, Nakai M, Nishimura K, Sumita Y, Ogawa H, Anzai T. Current practice and effects of intravenous anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized acute heart failure patients with sinus rhythm. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1202. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79700-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matoba T, Sakamoto K, Nakai M, Ichimura K, Mohri M, Tsujita Y, Yamasaki M, Ueki Y, Tanaka N, Hokama Y, et al. Institutional characteristics and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock in Japan ‐ analysis from the JROAD/JROAD‐DPC database. Circ J. 2021;85:1797–1805. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sindall ME, Davenport DL, Wallace P, Bernard AC. Validation of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grading system for acute mesenteric ischemia‐more than anatomic severity is needed to determine risk of mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:671–676. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Maryland State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brinkman GL, Coates EO Jr. The effect of bronchitis, smoking, and occupation on ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1963;87:684–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cho JS, Carr JA, Jacobsen G, Shepard AD, Nypaver TJ, Reddy DJ. Long‐term outcome after mesenteric artery reconstruction: a 37‐year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:453–460. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.118593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Acute LG, Ischaemia I. Best practice and research clinical. Gastroenterology. 2001;15:83–98. doi: 10.1053/bega.2000.0157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ryer EJ, Kalra M, Oderich GS, Duncan AA, Gloviczki P, Cha S, Bower TC. Revascularization for acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1682–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kougias P, Lau D, El Sayed HF, Zhou W, Huynh TT, Lin PH. Determinants of mortality and treatment outcome following surgical interventions for Acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park WM, Gloviczki P, Cherry KJ, Hallett JW, Bower TC, Panneton JM, Schleck C, Ilstrup D, Harmsen WS, Noel AA. Contemporary management of acute mesenteric ischemia: factors associated with survival. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:445–452. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.120373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roussel A, Castier Y, Nuzzo A, Pellenc Q, Sibert A, Panis Y, Bouhnik Y, Corcos O. Revascularization of acute mesenteric ischemia after creation of a dedicated multidisciplinary center. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:1251–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.06.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lobo Martínez E, Meroño Carvajosa E, Sacco O, Martínez ME. Embolectomy in mesenteric ischemia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1993;83:351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wadman M, Syk I, Elmståhl S. Survival after operations for ischaemic bowel disease. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:872–877. doi: 10.1080/110241500447263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Björck M, Acosta S, Lindberg F, Troëng T, Bergqvist D. Revascularization of the superior mesenteric artery after acute thromboembolic occlusion. Br J Surg. 2002;89:923–927. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wadman M, Block T, Ekberg O, Syk I, Elmståhl S, Acosta S. Impact of MDCT with intravenous contrast on the survival in patients with acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s10140-009-0828-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Z, Wang D, Li G, Wang X, Wang Y, Li G, Jiang T. Endovascular treatment for acute thromboembolic occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery and the outcome comparison between endovascular and open surgical treatments: a retrospective study. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1964765. doi: 10.1155/2017/1964765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Person B, Dorfman T, Bahouth H, Osman A, Assalia A, Kluger Y. Abbreviated emergency laparotomy in the non‐trauma setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2009;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-4-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yun WS, Lee KK, Cho J, Kim HK, Huh S. Treatment outcome in patients with acute superior mesenteric artery embolism. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2012.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boley SJ, Feinstein FR, Sammartano R, Brandt LJ, Sprayregen S. New concepts in the management of emboli of the superior mesenteric artery. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;153:561–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Inderbitzi R, Wagner HE, Seiler C, Stirnemann P, Gertsch P. Acute mesenteric ischaemia. Eur J Surg. 1992;158:123–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Akyildiz H, Akcan A, Oztürk A, Sozuer E, Kucuk C, Karahan I. The correlation of the D‐dimer test and biphasic computed tomography with mesenteric computed tomography angiography in the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia. Am J Surg. 2009;197:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barmase M, Kang M, Wig J, Kochhar R, Gupta R, Khandelwal N. Role of multidetector CT angiography in the evaluation of suspected mesenteric ischemia. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:e582–e587. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aschoff AJ, Stuber G, Becker BW, Hoffmann MH, Schmitz BL, Schelzig H, Jaeckle T. Evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia: accuracy of biphasic mesenteric multi‐detector CT angiography. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:345–357. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9392-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kirkpatrick ID, Kroeker MA, Greenberg HM. Biphasic CT with mesenteric CT angiography in the evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia: initial experience. Radiology. 2003;229:91–98. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291020991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ofer A, Abadi S, Nitecki S, Karram T, Kogan I, Leiderman M, Shmulevsky P, Israelit S, Engel A. Multidetector CT angiography in the evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yikilmaz A, Karahan OI, Senol S, Tuna IS, Akyildiz HY. Value of multislice computed tomography in the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Menke J. Diagnostic accuracy of multidetector CT in acute mesenteric ischemia: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Radiology. 2010;256:93–101. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Acosta S, Björnsson S, Ekberg O, Resch T. CT angiography followed by endovascular intervention for acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion does not increase risk of contrast‐induced renal failure. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Acosta S, Björck M. Modern treatment of acute mesenteric ischaemia. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e100–e108. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1