Abstract

This study determined metabolizable energy (ME) and developed ME prediction equations for broilers based on chemical composition of soybean meal (SBM) and rapeseed meal (RSM) using a 2 × 10 factorial arrangement of age (11 to 14 or 25 to 28 d of age) and 10 sources of each ingredient. Each treatment contained 6 replicates of 8 broilers. The ME values were determined by total collection of feces and urine. Principal components analysis (PCA) of the chemical composition clearly revealed distinct differences in SBM and RSM based on a principal components (PC) score plot. The nitrogen-corrected apparent metabolizable energy (AMEn) of SBM was higher in broilers from 25 to 28 than 11 to 14 d of age (P = 0.013). Interactions between broiler age and ingredient source affected apparent metabolizable energy (AME) of SBM and ME of RSM (P < 0.05). The ME of SBM in 11 to 14 and 25 to 28-day-old broilers were estimated by crude protein (CP) content (R2≥ 0.782; SEP ≤ 83 kcal/kg DM; P < 0.001). The AME and AMEn of RSM in 11 to 14-day-old broilers were estimated by ether extract (EE), ash and acid detergent fiber (ADF) (R2 = 0.897, SEP = 106 kcal/kg DM; P = 0.002), and by EE and ash (R2 = 0.885, SEP = 98 kcal/kg DM; P = 0.001), respectively. The AME and AMEn of RSM in 25 to 28-day-old broilers were estimated by ash and ADF (R2 = 0.925, SEP = 104 kcal/kg DM; P < 0.001) and by ash and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) (R2 = 0.921, SEP = 91 kcal/kg DM; P < 0.001), respectively. These results indicate that ME of these 2 plant protein ingredients are affected interactively by chemical composition and age of broilers. This study developed robust, age-specific prediction equations of ME for broilers based on chemical composition for SBM and RSM. Overall, ME values can be predicted from CP content for SBM, or EE, ash, ADF, and NDF for RSM.

Key words: metabolizable energy, chemical composition, prediction, broiler

INTRODUCTION

Accurate metabolizable energy (ME) values of feed ingredients are crucial to diet formulation as energy accounts for approximately 75% the cost of broiler diets (Musigwa et al., 2021). Soybean meal (SBM) and rapeseed meal (RSM) are the byproducts of oil extraction and primary protein ingredients for broilers. The ME values vary depending on chemical composition of each source which relates to the varieties, growing environment, agronomy of oilseeds and oil extraction process (Qin et al., 1998; Baker et al., 2011; Banaszkiewicz, 2011; Khajali and Slominski, 2012; Zhou et al., 2021). Thus, many nutritionists have aimed to establish ME prediction models from chemical composition of SBM and RSM for poultry. Janssen (1989) developed an apparent metabolizable energy (AME) prediction model from crude protein (CP), ether extract (EE), and nitrogen free extract for SBM in adult cockerels. The CVB (2018) recommended ash, CP, EE, and crude fiber (CF) to predict the nitrogen-corrected apparent metabolizable energy (AMEn) of SBM for roosters. Furthermore, Alvarenga et al. (2013) validated that the AMEn of SBM calculated by prediction models resulted in better performance compared to the use of tabulated AME value for broilers. These findings suggest prediction models improved the accuracy of AMEn of SBM for broilers. In the ME prediction models for RSM, Toghyani et al. (2014) observed that the AMEn of RSM for broilers was estimated by acid detergent fiber (ADF), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and ash, and Ding et al. (2019) reported NDF was the best factor to predict the ME of RSM for broilers. These studies commonly indicate that the fiber can predict the ME for SBM and RSM, but the effect of EE, ash, or CP on ME varied across the 2 protein ingredients. However, various ME prediction models for SBM or RSM were developed using different sources, and the selection and contribution of predictors to the ME can depend on the composition of source. In recent years, genetics of oilseed crops and the process of oil extraction has developed rapidly (Hu et al., 2017; So and Duncan, 2021; Rahman et al., 2023), which can alter the chemical composition of SBM and RSM. Additionally, many studies have shown the AME of SBM and RSM depended on age for quick-growing broilers (Shires et al., 1980; Brumano et al., 2006; Bertechini et al., 2019), indicating unique ME prediction models may be warranted for broilers in starter and growing phases. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to investigate the effects of age and source on the ME of SBM and RSM, and to establish AME and AMEn prediction models based on chemical compositions using 10 sources for each ingredient of SBM and RSM sample in China for broilers at 11 to 14 and 25 to 28 d of age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experimental procedures related the use of live broilers were approved by the animal care and welfare committee of the Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China). The code of ethical inspection was IAS 2022-143.

Feed Ingredients and Experimental Diets

A total of 10 SBM and 10 RSM were sampled across China. The chemical compositions were shown in Table 1. A corn-soybean meal basal diet was formulated with a CP of 17.5% to guarantee the CP of experimental diet was less than 25% according to the technical protocol for the determination of ME in feed for Arbor Acre (AA) broilers recommended by Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of P. R. China (2020). Twenty experimental diets were formulated by mixing 20% of each test ingredient sample with 80% of basal diet (Table 2). Corn, SBM, and test ingredients were ground through a 1.5-mm screen, then pelleted with a non-steam granulator (Type: KL200, Laizhou Chengda Machinery Co., LTD.).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of soybean meals and rapeseed meals (dry matter basis).

| Item | GE, Kcal/kg DM | CP, % | EE, % | Ash, % | CF, % | ADF, % | NDF, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBM 1 | 4636 | 49.31 | 1.43 | 6.72 | 10.04 | 11.10 | 19.14 |

| SBM 2 | 4648 | 49.98 | 1.20 | 6.72 | 9.55 | 10.17 | 18.34 |

| SBM 3 | 4738 | 52.54 | 2.00 | 6.77 | 5.39 | 4.81 | 15.29 |

| SBM 4 | 4653 | 50.15 | 1.00 | 6.61 | 7.58 | 8.03 | 15.36 |

| SBM 5 | 4710 | 50.53 | 2.38 | 6.58 | 6.94 | 6.46 | 11.73 |

| SBM 6 | 4676 | 53.31 | 0.88 | 6.85 | 6.23 | 5.92 | 7.99 |

| SBM 7 | 4701 | 54.04 | 1.36 | 6.95 | 5.65 | 6.76 | 11.28 |

| SBM 8 | 4727 | 54.89 | 1.48 | 6.68 | 4.34 | 4.34 | 7.89 |

| SBM 9 | 4704 | 55.14 | 1.26 | 6.89 | 4.04 | 2.40 | 7.98 |

| SBM 10 | 4682 | 53.47 | 0.96 | 6.66 | 5.53 | 5.99 | 9.51 |

| MeanSBM 1-10 | 4688 | 52.34 | 1.39 | 6.74 | 6.53 | 6.60 | 12.45 |

| SDSBM 1-10 | 35 | 2.17 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 2.02 | 2.62 | 4.31 |

| MinimumSBM 1-10 | 4636 | 49.31 | 0.88 | 6.58 | 4.04 | 2.40 | 7.89 |

| MaximumSBM 1-10 | 4738 | 55.14 | 2.38 | 6.95 | 10.04 | 11.10 | 19.14 |

| RSM 1 | 5007 | 37.07 | 8.70 | 6.82 | 18.82 | 27.77 | 32.26 |

| RSM 2 | 4710 | 45.56 | 1.58 | 7.19 | 15.49 | 18.45 | 27.49 |

| RSM 3 | 4714 | 44.63 | 1.50 | 6.93 | 14.83 | 20.32 | 31.29 |

| RSM 4 | 4704 | 44.94 | 2.00 | 7.20 | 14.20 | 19.17 | 27.12 |

| RSM 5 | 4773 | 42.77 | 3.43 | 7.35 | 15.14 | 19.00 | 28.71 |

| RSM 6 | 4746 | 44.35 | 1.14 | 8.46 | 24.77 | 43.65 | 61.70 |

| RSM 7 | 4730 | 44.44 | 2.65 | 8.71 | 16.45 | 24.83 | 38.49 |

| RSM 8 | 4608 | 42.73 | 1.11 | 8.63 | 18.50 | 27.20 | 40.20 |

| RSM 9 | 4728 | 44.01 | 1.50 | 7.37 | 15.93 | 19.76 | 33.49 |

| RSM 10 | 4718 | 43.99 | 1.17 | 7.22 | 15.41 | 19.79 | 32.04 |

| MeanRSM 1-10 | 4744 | 43.45 | 2.48 | 7.59 | 16.95 | 23.99 | 35.28 |

| SDRSM 1-10 | 102 | 2.41 | 2.31 | 0.72 | 3.13 | 7.74 | 10.23 |

| MinimumRSM 1-10 | 4608 | 37.07 | 1.11 | 6.82 | 14.20 | 18.45 | 27.12 |

| MaximumRSM 1-10 | 5007 | 45.56 | 8.70 | 8.71 | 24.77 | 43.65 | 61.70 |

Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; GE, gross energy; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; CF, crude fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

The composition of the basal and test diets (As-received basis, %).

| Items | Basal diet1 | Test diets |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Diets 1 to 10 | Diets 11 to 20 | ||

| Ingredients | |||

| Corn | 67.17 | ||

| SBM (non-experimental) | 26.05 | ||

| Dicalcium phosphate | 1.92 | ||

| Soybean oil | 2.56 | ||

| Limestone | 1.14 | ||

| Premix1 | 0.50 | ||

| Sodium chloride | 0.30 | ||

| L-lysine | 0.15 | ||

| DL-methionine | 0.16 | ||

| L-threonine | 0.05 | ||

| Basal diet | 80.00 | 80.00 | |

| Test ingredient | |||

| SBM, 1 to 10 | 20.00 | ||

| RSM, 1 to 10 | 20.00 | ||

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutrient content, %2 | |||

| DM | 90.87 | 90.50∼91.31 | 90.41∼91.53 |

| GE, Kcal/kg | 4092 | 4111∼4148 | 4113∼4173 |

| CP | 17.71 | 22.80∼25.06 | 21.06∼23.02 |

Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; DM, dry matter; GE, gross energy; CP, crude protein.

Supplied per kilogram of diet: vitamin A, 8,000 IU, vitamin D3 1 000 IU, vitamin E 20 IU, vitamin K3 0.8 mg, vitamin B1 3 mg, vitamin B2 8 mg, vitamin B6 5 mg, vitamin B12 0.02 mg, biotin 0.2 mg, folic acid 0.6 mg, pantothenic acid 10 mg, nicotinic acid 40 mg, Cu (as copper sulfate) 8 mg, Fe (as ferrous sulfate) 100 mg, Mn (as manganese sulfate) 120 mg, Zn (as zinc sulfate) 100 mg, I (as potassium iodide) 0.70 mg, Se (as sodium selenite) 0.30 mg, Choline chloride 1500 mg.

Values were determined values (Air-dry basis).

Experimental Design

The ME of SBM and RSM were determined using 2 batches of broilers. A total of 528 eight-day-old AA male broilers (BW = 208 ± 1 g) were selected from the first batch and randomly divided into 11 groups with 6 replicates of 8 broilers in each. One group was used to determine the ME of basal diet. The remaining 10 groups were used to determine the ME of experimental diets of 10 SBM. Another 528 twenty-two-day-old AA male broilers (BW = 961 ± 15 g) were selected from the first batch and randomly divided into 11 groups. Each group contained 6 replicates of 8 broilers. One group was used to determine the ME of basal diet. The remaining 10 groups were used to determine the ME of experimental diets of 10 SBM. Similar experiment was designed to determine the ME of basal diet and experimental diets of RSM for broilers selected on 8 (BW = 221±1 g, n = 528) and 22 (BW = 1,123 ± 14 g, n = 528) d of age from the second batch. This resulted a 2 × 10 factorial arrangement of age (11 to 14 or 25 to 28 d of age) and 10 sources within each ingredient (SBM and RSM).

AME Bioassay

The AME bioassays were conducted at the experimental base of the State Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition and Feeding, the Institute of Animal Science of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China) in accordance with the technical specifications for white-feather broilers recommended by Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of P. R. China (2020). Two batches of 1,360 one-day-old AA male broilers were obtained from a local hatchery and provided free access to a commercial starter-grower broiler diet (Charoen Pokphand Feed) and water in 3-tier cages when not participating in an energy balance experiment. The energy balance experiments were conducted over 6 d (8–14 and 22–28 d of age). In each period, 528 AA male broilers with similar body weight were transferred to metabolic cages and randomly divided into 11 groups. They were acclimated with experimental diets for 55 h, followed by withdrawal for 17 h, free access to experimental diets for 55 h, and followed by 17 h fasting. Meanwhile excreta were collected for 72 h by the total collection method. The AME was determined by the difference between gross energy (GE) intake and GE output from feces and urine. The AMEn was calculated by AME corrected to zero nitrogen balance according to Hill et al. (1960). During the fasting period, chickens could freely access glucose saline solution (5% of glucose and 0.9% of sodium chloride). Excreta were dried using forced air in a drying oven at 65 ℃.

Chemical Analysis

Dry matter (DM) was determined using AOAC (2005) methods 930.15 and 925.10. The GE was measured according to ISO 9831:1998 using a Parr 6400 automatic adiabatic calorimeter (Parr instrument company, Moline, IL). The nitrogen was determined by AOAC (2005) method 984.13 using a Kjeldahl nitrogen analyzer (model KDY-9820, Shandong Haineng Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Dezhou, China), and the CP content was calculated as nitrogen content × 6.25. The EE content of ingredients was determined according to AOAC (2005) method 954.02 using an automatic fat analyzer (model SOX-406, Shandong Haineng Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Dezhou, Shandong). The ash was determined by AOAC (2005) method 942.05 using a muffle furnace at 550 ℃ for 4 h. The CF and ADF were determined by AOAC (2005) methods 978.10 and 973.18, respectively. The NDF was determined by the methods outlined by Van Soest et al. (1991).

Calculation and Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed on DM basis. The AME and AMEn of the experimental diets were calculated by the following formulas (Wang et al., 2022):

in which FI is the feed intake (kg DM); GEd is the GE content of diet (kcal/kg DM); EO is the output of excreta (kg DM); GEe is the GE content of excreta (kcal/kg DM); RN (retained nitrogen, g) = diet intake (g) × nitrogen content of diet – excreta output (g) × nitrogen content of excreta; and 8.22 kcal/g is the GE of uric acid per gram of nitrogen (Hill and Anderson, 1958).

The AMEn of feed ingredients were calculated according to the formula of Ye et al. (2022):

in which AMEti, AMEtd or AMEbd is the AME of test ingredient, test diet or basal diet; AMEnti, AMEntd or AMEnbd is the AMEn of test ingredient, test diet or basal diet; and Pti is the proportion of DM from the test ingredient in the test diet.

The chemical composition and ME of 20 feed ingredients were summarized using the MEANS procedure of SAS 9.4 (SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC). Principal components analysis (PCA) of chemical characteristics and GE of SBM and RSM samples was performed using JMP Pro 16 (SAS Inst. Inc.). The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the variance matrix and the cumulative variance contribution rate of principal components (PC) were calculated to obtain the load matrix, and the PC values were charted in scatterplots. The GLM procedure (SAS 9.4) was used to analyze the effect of age (d 11–14; d 25–28), ingredient source (10 samples), and interactions on the AME and AMEn of each ingredient. Means were separated by the Tukey honest significant difference. The CORR procedure (SAS 9.4) was performed to calculate correlation coefficients between chemical composition and AME or AMEn of SBM or RSM. The REG procedures (SAS 9.4) were employed to establish prediction equations for AME and AMEn specific for each age and ingredient. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Standard error of prediction (SEP) indicated the quality of prediction equations, and was calculated according to the following equation (Yegani et al., 2013):

where Y and Y’ were the determined and calculated values of AME or AMEn. N is the total numbers of samples.

RESULTS

Principal Component Analysis of Chemical Compositions for Soybean Meal and Rapeseed Meal Samples

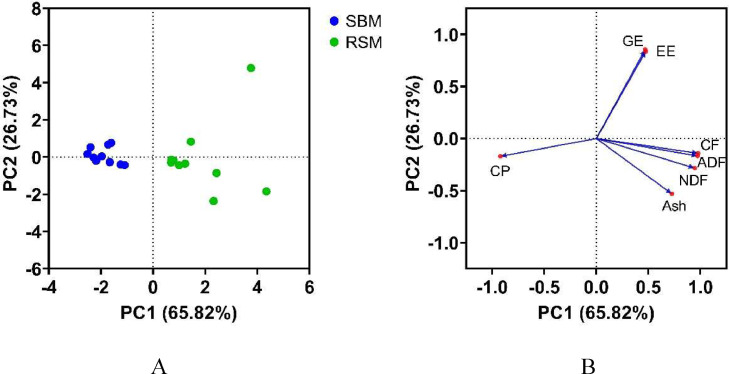

The PCA of the chemical composition of the 2 groups of SBM and RSM sample showed that the first 2 PC together explained 92.55% of the total variation (Table 3). The PC1 was mainly associated with CF, ADF, NDF, CP, and ash, and the PC2 was associated with EE and GE (Figure 1). The PC score plot characterized each sample for their position on PC1 and PC2 and clearly identified the 2 main populations: SBM and RSM. The distribution across sources was apparently more consistent for SBM relative to RSM.

Table 3.

Loading vectors of original variables on principal component as estimated by principal component analysis.

| Original variables | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|

| GE, Kcal/kg | 0.474 | 0.8371 |

| CP, % | −0.9211 | −0.171 |

| EE, % | 0.469 | 0.8541 |

| Ash, % | 0.7251 | −0.5321 |

| CF, % | 0.9771 | −0.141 |

| ADF, % | 0.9711 | −0.168 |

| NDF, % | 0.9441 | −0.284 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.607 | 1.871 |

| Proportion | 65.819 | 26.734 |

| Cumulative | 65.819 | 92.552 |

Abbreviation: GE, gross energy; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; CF, crude fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; PC, principal component.

Variables loaded on extracted components (i.e. loading vectors higher than 0.50).

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis of SBM and RSM: scores and loading plots of PCA model constructed from chemical composition as model variables (N = 20). Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; GE, gross energy; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; CF, crude fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; PC, principal component.

Metabolizable Energy of Soybean Meal and Rapeseed Meal Diets for Broilers From 11 to 14 and 25 to 28 d of age

The effects of broiler age and ingredient source on the AME and AMEn of the experimental diets were shown in Table 4. In SBM diets, there was an interaction between age and source of SBM on AME (P = 0.019) in which there was no effect of source on AME of SBM diet for broilers from 11 to 14 d of age, but the AME differed across sources of SBM diet for broilers aged from 25 to 28 d. There was no similar interaction affecting the AMEn of SBM diet. The age did not affect AMEn of SBM diets (P = 0.224). No statistical differences were observed in AMEn across SBM diets 6 to 10 or SBM diets 1 to 5, but the AMEn of SBM diet 8 was greater than that of SBM diets 1 to 5 (P < 0.05). There were interactions between age and ingredient source affecting the AME and AMEn of RSM diets (P < 0.05). Greater AME was observed in RSM diet 1 compared to RSM diets 3, 4, and 9 in 11 to 14-day-old broilers (P < 0.05), but no statistical differences of AME were observed across these 4 RSM diets in 25 to 28-day-old broilers. There were no statistical differences in AMEn of RSM diets 3, 4, and 8 in 11 to 14-day old broilers, but the AMEn of RSM diet 8 was lower than these of RSM diets 3 and 4 (P < 0.05) in 25 to 28-day old broilers. In addition, greater AMEn was observed in RSM diet 1 compared to RSM diets 3, 4, 9, and 10 in broilers from 11 to 14 d of age (P < 0.05), but there were no statistical differences in AMEn of these 5 RSM diets at 25 to 28 d of age.

Table 4.

The metabolizable energy (kcal/kg DM) of experimental diets (including the basal diet1) for broilers from 11 to 14 and 25 to 28 d of age.

| Item | SBM diet |

RSM diet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sources of sample | AME | AMEn | AME | AMEn |

| D 11 to 14 | 1 | 3244cdef | 3054 | 3288a | 3116a |

| 2 | 3242def | 3062 | 3243abc | 3047abc | |

| 3 | 3259bcdef | 3087 | 3188bcd | 3004cde | |

| 4 | 3261bcdef | 3077 | 3175cde | 3010cde | |

| 5 | 3267bcdef | 3088 | 3234abc | 3057abc | |

| 6 | 3277bcdef | 3089 | 3060fg | 2923f | |

| 7 | 3304abcde | 3130 | 3106ef | 2931f | |

| 8 | 3308abcd | 3122 | 3108ef | 2941ef | |

| 9 | 3285abcde | 3107 | 3208bc | 3021bcd | |

| 10 | 3285abcde | 3095 | 3220abc | 3041bc | |

| D 25 to 28 | 1 | 3229ef | 3058 | 3252ab | 3084ab |

| 2 | 3245cdef | 3075 | 3263ab | 3067abc | |

| 3 | 3279bcdef | 3099 | 3218abc | 3031bc | |

| 4 | 3205f | 3036 | 3216abc | 3048abc | |

| 5 | 3260bcdef | 3079 | 3223abc | 3048abc | |

| 6 | 3297abcde | 3111 | 3023g | 2887f | |

| 7 | 3300abcde | 3110 | 3089fg | 2917f | |

| 8 | 3361a | 3161 | 3122def | 2954def | |

| 9 | 3332ab | 3138 | 3247abc | 3057abc | |

| 10 | 3321abc | 3117 | 3252ab | 3070abc | |

| SEM | 15 | 13 | 15 | 14 | |

| Age | D 11 to 14 | 3273 | 3091 | 3183 | 3009 |

| D 25 to 28 | 3283 | 3098 | 3190 | 3016 | |

| Sources of sample | 1 | 3237 | 3056d | 3270 | 3100 |

| 2 | 3244 | 3068cd | 3253 | 3057 | |

| 3 | 3269 | 3093bcd | 3203 | 3017 | |

| 4 | 3233 | 3056d | 3196 | 3029 | |

| 5 | 3264 | 3083bcd | 3228 | 3053 | |

| 6 | 3287 | 3100abc | 3042 | 2905 | |

| 7 | 3302 | 3120ab | 3097 | 2924 | |

| 8 | 3334 | 3142a | 3115 | 2947 | |

| 9 | 3308 | 3122ab | 3227 | 3039 | |

| 10 | 3303 | 3106abc | 3236 | 3056 | |

| Variance of sources, P-value | |||||

| Age | 0.155 | 0.224 | 0.258 | 0.244 | |

| Sources of sample | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Age × Sources of sample | 0.019 | 0.100 | 0.040 | 0.047 | |

Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; AME, apparent metabolizable energy; AMEn, N-corrected apparent metabolizable energy.

In the ME determination of SBM, the values of basal diet were 3,465 kcal/kg DM for AME and 3,315 kcal/kg DM for AMEn in 11 to 14-day-old broilers, or 3,458 kcal/kg DM for AME and 3,306 kcal/kg DM for AMEn in 25 to 28-day-old broilers. In the ME determination of RSM, the values of basal diet were 3,543 kcal/kg DM for AME and 3,382 kcal/kg DM for AMEn in 11 to 14-day-old broilers, or 3,525 kcal/kg DM for AME and 3,364 kcal/kg DM for AMEn in 25 to 28-day-old broilers.

Metabolizable Energy of Soybean Meal and Rapeseed Meal for Broilers From 11 to 14 and 25 to 28 d of age

The effects of age and ingredient source on the AME and AMEn of SBM or RSM were shown in Table 5. In SBM samples, there was an interaction between age and source of SBM on AME (P = 0.021) in which there was no effect of source on AME of SBM for broilers from 11 to 14 d of age, but the AME differed across sources of SBM for broilers aged from 25 to 28 d. For example, the AME of SBM 8 exceeded that of other SBM samples except SBM 6, 7, 9, and 10 (P < 0.05), and the AME of SBM 9 to 10 were greater than those of SBM 1 and 4 (P < 0.05) for broilers from 25 to 28 d of age. There was no similar interaction affecting the AMEn of SBM. The AMEn of SBM was lower for broilers from 11 to 14 than 25 to 28 d of age (P = 0.013). No statistical differences were observed in AMEn across SBM 6 to 10 or SBM 1 to 5, but the AMEn of SBM 8 exceeded that of SBM 1 to 5 (P < 0.05). There were interactions between age and source affecting the AME and AMEn of RSM (P<0.05). The AME in 11 to 14-day-old broilers was greater for RSM 1 compared to RSM 3, 4, and 9 (P < 0.05), but no statistical differences of AME were observed across these 4 RSM samples in 25 to 28-day-old broilers. There were no differences in AMEn of RSM 3, 4, and 8 in 11 to 14-day old broilers, but the AMEn of RSM 8 was lower than that of RSM 3 and 4 (P < 0.05) in 25 to 28-day old broilers. In addition, the AMEn of RSM 1 exceeded that of RSM 3, 4, 9, and 10 in broilers from 11 to 14 d of age (P < 0.05), but there were no differences in AMEn of these 5 RSM samples at 25 to 28 d of age.

Table 5.

The metabolizable energy (kcal/kg DM) of soybean meals and rapeseed meals for broilers from 11 to 14 and 25 to 28 d of age.

| Item | SBM |

RSM |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sources of sample | AME | AMEn | AME | AMEn |

| D 11 to 14 | 1 | 2374de | 2030 | 2287a | 2072a |

| 2 | 2365de | 2071 | 2061abcd | 1725abcd | |

| 3 | 2451cde | 2199 | 1784cde | 1505def | |

| 4 | 2455cde | 2139 | 1717def | 1536def | |

| 5 | 2495bcde | 2200 | 2034abcd | 1797abcd | |

| 6 | 2548bcde | 2216 | 1192gh | 1147g | |

| 7 | 2662abcd | 2395 | 1375fgh | 1149g | |

| 8 | 2682abcd | 2352 | 1396fgh | 1207fg | |

| 9 | 2581bcde | 2291 | 1869bcde | 1584cde | |

| 10 | 2583bcde | 2238 | 1935abcd | 1685bcde | |

| D 25 to 28 | 1 | 2335de | 2087 | 2181ab | 1982ab |

| 2 | 2415cde | 2169 | 2228ab | 1891abc | |

| 3 | 2581bcde | 2290 | 1999abcd | 1710bcd | |

| 4 | 2218e | 1981 | 1994abcd | 1795abcd | |

| 5 | 2489bcde | 2195 | 2052abcd | 1822abcd | |

| 6 | 2670abcd | 2353 | 1081h | 1037g | |

| 7 | 2673abcd | 2336 | 1363fgh | 1149g | |

| 8 | 2977a | 2588 | 1536efg | 1341efg | |

| 9 | 2840ab | 2483 | 2139abc | 1830abcd | |

| 10 | 2789abc | 2385 | 2163ab | 1900abc | |

| SEM | 74 | 65 | 74 | 69 | |

| Age | D 11 to 14 | 2520 | 2213 | 1765 | 1541 |

| D 25 to 28 | 2599 | 2287 | 1869 | 1643 | |

| Sources of sample | 1 | 2354 | 2058d | 2234 | 2027 |

| 2 | 2390 | 2120cd | 2144 | 1808 | |

| 3 | 2516 | 2244bcd | 1891 | 1608 | |

| 4 | 2337 | 2060d | 1855 | 1665 | |

| 5 | 2492 | 2197bcd | 2043 | 1810 | |

| 6 | 2609 | 2285abc | 1137 | 1092 | |

| 7 | 2668 | 2365ab | 1369 | 1149 | |

| 8 | 2829 | 2470a | 1466 | 1274 | |

| 9 | 2710 | 2387ab | 2004 | 1707 | |

| 10 | 2686 | 2311abc | 2049 | 1793 | |

| Variance of sources, P-value | |||||

| Age | 0.019 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| Sources of sample | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Age×Sources of sample | 0.021 | 0.103 | 0.040 | 0.047 | |

Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; AME, apparent metabolizable energy; AMEn, N-corrected apparent metabolizable energy.

Correlation Between Chemical Compositions and Metabolizable Energy in Soybean Meal and Rapeseed Meal

There were significant correlations amongst chemical compositions and ME of SBM and RSM (Table 6). The GE and CP were positively correlated (r = 0.666, P < 0.05), but there were negative correlations between GE and CF or ADF and between CP and fiber components (CF, ADF, or NDF) (|r|≥ 0.815, P < 0.01) for SBM. The fiber components (CF, ADF, or NDF) of SBM were positively related to each other (r≥0.826, P<0.01). The AME and AMEn of SBM positively correlated with the CP (r ≥ 0.884, P < 0.01) but negatively correlated with the fiber components (CF, ADF, or NDF) (|r|≥0.703, P < 0.05) for 11 to 14-day-old broilers. The AMEn of SBM positively correlated with the GE (r = 0.722, P < 0.05) for 11 to 14-day-old broilers. Similarly, the AME and AMEn of SBM positively correlated with the GE and CP (r ≥ 0.662, P < 0.05) but negatively correlated with the fiber components (CF, ADF, or NDF) (|r|≥0.776, P < 0.01) for 25 to 28-day-old broilers. In the RSM samples, positive correlation was observed between GE and EE (r = 0.933, P < 0.01), ash and NDF (r = 0.695, P < 0.05), and between fiber components (CF, ADF, and NDF; r ≥ 0.930, P < 0.01). However, the CP negatively correlated with the GE and EE (|r|≥ 0.817, P < 0.01) of RSM. Both AME and AMEn of RSM negatively correlated with ash and NDF (|r|≥ 0.659, P < 0.05) and AMEn postively correlated with GE and EE (r ≥ 0.652, P < 0.05) for 11 to 14-day-old broilers. The AME and AMEn of RSM negatively correlated with ash, CF ADF and NDF (|r|≥0.644, P < 0.05) for 25 to 28-day-old broilers.

Table 6.

Pearson correlation coefficients between chemical composition and metabolizable energy in soybean meals and rapeseed meals.

| Item | GE | CP | EE | Ash | CF | ADF | NDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBM | |||||||

| CP | 0.666* | ||||||

| EE | 0.555 | −0.179 | |||||

| Ash | 0.169 | 0.560 | −0.270 | ||||

| CF | −0.823⁎⁎ | −0.924⁎⁎ | −0.046 | −0.337 | |||

| ADF | −0.815⁎⁎ | −0.858⁎⁎ | −0.120 | −0.302 | 0.966⁎⁎ | ||

| NDF | −0.564 | −0.861⁎⁎ | 0.151 | −0.282 | 0.856⁎⁎ | 0.826⁎⁎ | |

| AME d11-14 | 0.599 | 0.884⁎⁎ | −0.122 | 0.363 | −0.836⁎⁎ | −0.703* | −0.875⁎⁎ |

| AMEn d11-14 | 0.722* | 0.886⁎⁎ | 0.024 | 0.460 | −0.872⁎⁎ | −0.753* | −0.806⁎⁎ |

| AME d25-28 | 0.662* | 0.930⁎⁎ | −0.063 | 0.374 | −0.834⁎⁎ | −0.778⁎⁎ | −0.834⁎⁎ |

| AMEn d25-28 | 0.673* | 0.922⁎⁎ | −0.040 | 0.408 | −0.818⁎⁎ | −0.776⁎⁎ | −0.808⁎⁎ |

| RSM | |||||||

| CP | −0.817⁎⁎ | ||||||

| EE | 0.933⁎⁎ | −0.908⁎⁎ | |||||

| Ash | −0.458 | 0.236 | −0.369 | ||||

| CF | 0.185 | −0.241 | 0.076 | 0.527 | |||

| ADF | 0.156 | −0.193 | 0.054 | 0.571 | 0.982⁎⁎ | ||

| NDF | −0.088 | 0.050 | −0.215 | 0.695* | 0.930⁎⁎ | 0.951⁎⁎ | |

| AME d11-14 | 0.579 | −0.454 | 0.570 | −0.878⁎⁎ | −0.517 | −0.609 | −0.757* |

| AMEn d11-14 | 0.677* | −0.552 | 0.652* | −0.870⁎⁎ | −0.389 | −0.477 | −0.659* |

| AME d25-28 | 0.287 | −0.194 | 0.286 | −0.898⁎⁎ | −0.714* | −0.795⁎⁎ | −0.869⁎⁎ |

| AMEn d25-28 | 0.369 | −0.275 | 0.359 | −0.924⁎⁎ | −0.644* | −0.724* | −0.828⁎⁎ |

Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; GE, gross energy; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; CF, crude fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; AME, apparent metabolizable energy; AMEn, N-corrected apparent metabolizable energy.

Means P<0.01

Means 0.01≤P<0.05

Prediction Equations of Metabolizable Energy on Chemical Compositions of Soybean Meal and Rapeseed Meal

Equations to predict the AME and AMEn from chemical composition of SBM and RSM were developed by stepwise regression analysis (Table 7). The AME and AMEn of SBM were estimated by CP content (R2 ≥ 0.782, SEP ≤ 83 kcal/kg DM; P < 0.001) for 11 to 14 and 25 to 28-day-old broilers. The AME of RSM was estimated by EE, ash, and ADF(R2 = 0.897, SEP = 106 kcal/kg DM; P = 0.002), but AMEn was estimated by EE and ash (R2 = 0.885, SEP = 98 kcal/kg DM; P = 0.001) for 11 to 14-day-old broilers. The AME of RSM was estimated by ash and ADF (R2=0.925, SEP=104 kcal/kg DM; P < 0.001), and AMEn were estimated by ash and NDF (R2 = 0.921, SEP = 91 kcal/kg DM; P < 0.001) for 25 to 28-day-old broilers.

Table 7.

Prediction equations of metabolizable energy (kcal/kg DM) on chemical composition (%, DM basis) in soybean meals and rapeseed meals for broilers from 11 to 14 and 25 to 28 d of age.

| Item | Age | Prediction Model | R2 | SEP, kcal/kg DM | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBM | D 11 to 14 | AME = 161 + 45.06×CP | 0.782 | 49 | <0.001 |

| AMEn = -243 + 46.93×CP | 0.785 | 51 | <0.001 | ||

| D 25 to 28 | AME = -2729 + 101.80×CP | 0.864 | 83 | <0.001 | |

| AMEn = -1785 + 77.79×CP | 0.851 | 67 | <0.001 | ||

| RSM | D 11 to 14 | AME = 4016+57.26 × EE-271.49 × Ash-13.89 × ADF | 0.897 | 106 | 0.002 |

| AMEn = 3740 + 50.34×EE-306.24 × Ash | 0.885 | 98 | 0.001 | ||

| D 25 to 28 | AME = 5164-365.15 × Ash-21.67 × ADF | 0.925 | 104 | <0.001 | |

| AMEn = 4481-318.38 × Ash-11.90 × NDF | 0.921 | 91 | <0.001 |

Abbreviation: SBM, soybean meal; RSM, rapeseed meal; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; ADF, acid detergent fiber; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; AME, apparent metabolizable energy; AMEn, N-corrected apparent metabolizable energy.

DISCUSSION

The CP of the SBM used in the current study was higher than RSM, and the SBM had less CF than RSM, but there was considerable variation across sources (CV of CP > 4.1% and CF > 18.4% across sources for each ingredient). In oilseeds, most of the protein is stored in the embryo while fiber components are mostly from seed hulls. Soybean and rapeseed contained 10% and 15% of hull, 40% and 21% of protein, 21% and 40% of oil, respectively (Li et al., 2012; Medic et al., 2014; Kaczmarek et al., 2016). After oil extraction, the proportions of hulls in SBM and RSM concentrate to 11% and 30%, respectively (Kaczmarek et al., 2016). As a result, fiber contents of soybean and rapeseed meals are higher than that of the respective oilseed. The CP of SBM was higher than that of RSM which is in accordance with other researches (Florou-Paneri et al., 2014). To show the overall variation of the chemical composition of SBM and RSM more directly, PCA was used to reduce the dimensionality of data sets, improve interpretation, and preserve variability of the data (Jolliffe and Cadima, 2016). Others have applied PCA to the classify feed ingredients, define forage populations, screen pelleting properties of wheat, or evaluate the availability of agro-industrial by-products (Gallo et al., 2013; Kong et al., 2015; García-Rodríguez et al., 2019). In the current study, PCA explored the variable chemical components of 10 sources each of SBM and RSM. The 7 chemical components were integrated into 2 PC, which reflected 92.6% of the original variable information. The 2-dimensional scatter plot of the 2 PC revealed distinct visual segregation by ingredient: SBM with generally high CP content but low fiber concentration, and RSM with generally high fiber and EE content. This indicates that PCA can effectively distinguish different chemical compositions of SBM and RSM.

Nutritionists generally agree that the ME of feed for broilers is affected by the development of digestive tract (Smulikowska, 1998), because digestive tract weight, intestinal villus surface area, and microbial fermentation of cecal digesta all increase as broilers age (Rehman et al., 2007; Li et al., 2020). Furthermore, trypsin and chymotrypsin activities in broilers at 28 d of age were 49% and 89% higher respectively than those at 14 d of age (Lin et al., 2017). The current study revealed that the AMEn of SBM increased with broilers age, which was in accordance with the reports by Shires et al. (1980) and Bertechini et al., 2019 indicating an age-dependent effect on the ME of SBM for broilers. However, the interactive effects between sample source and age were observed on AME of SBM and AME or AMEn of RSM, indicating inconsistent differences in ME for broilers at 2 growth phases. The AME of SBM 6 to 10 were higher for broilers at 25 to 28 d of age compared to SBM 1 to 5 than 11 to 14 d of age. It is noteworthy that SBM 6 to10 contained higher CP and less fiber content than those of SBM 1 to 5 which likely contributed to the age dependent variation as the older broilers could more effectively digest CP. Pope et al. (2023) summarized that CP concentrations across 5 sources of SBM ranged from 44 to 48% and positively correlated with ME. Previous studies report the CP digestibility of SBM increases with age of broilers (An and Kong, 2022). The inconsistent difference in the AME or AMEn of several RSM at the 2 age phases could relate to high fiber content. Fiber has the ability to escape digestion and absorption in the small intestine and contributes to variable digestibility in broilers (Tejeda and Kim, 2021). Others have shown that nutrient utilization was related to the interaction between fiber components and the age of broilers (Jiménez-Moreno et al., 2009).

Generally, the fiber components (CF, ADF, NDF) and ash negatively correlate with ME (Downey and Bell, 1990; Khajali and Slominski, 2012), but GE and EE positively correlate with ME (Livesey, 1995). Stepwise regression eliminates the multicollinearity between various chemical components and ME (Garg and Tai, 2012). In SBM, CP negatively correlated with fiber components (|r|≥0.858), but ME positively correlated with CP (r ≥ 0.884) and negatively correlated with fiber components (|r|≥0.703). These findings indicate multicollinearity between CP and fiber on ME. Consequently, only CP was determined as a predictor in the ME prediction equation of SBM for broilers regardless of age, in accordance with reports by Jiang et al. (2021). For RSM sources, EE, ash, and fiber components were primarily predictors to estimate ME in the current study. Similar results were observed by Toghyani et al. (2014) who reported the ME could be predicted from NDF, ash, and ADF for RSM with 8.3% fat content (R2 = 0.91), and Chibowska et al. (2000) who reported ME was negatively correlated with CF whereas positively correlated with EE (AMEn = 10.78 - 0.30 (% CF) + 0.20 (% EE)). This indicates although the nutrient profile of RSM is greatly influenced by the variety, seed quality and processing technology, fiber and EE can effectively estimate its ME value.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrated clear difference in the ME value of different sources of samples in each of SBM or RSM that were linked to chemical composition and age indicating their interactive effects on the ME. This study developed robust, age specific prediction equations of ME for broilers based on chemical composition for SBM as well as RSM. Overall, ME values can be predicted from CP content for SBM, or EE, ash, ADF, and NDF content for RSM.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was financially supported by the project of nutritional value evaluation and parameter establishment of feed ingredient of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China (No.16190301) and the Innovation Team of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ASTIP-IAS-08) (Beijing, China).

REFERENCES

- Alvarenga R.R., Rodrigues P.B., Zangeronimo M.G., Makiyama L., Oliveira E.C., Freitas R.T., Lima R.R., Bernardino V.M. Validation of prediction equations to estimate the energy values of feedstuffs for broilers: performance and carcass yield. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013;26:1474–1483. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2013.13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S.H., Kong C. Influence of age and type of feed ingredients on apparent and standardized ileal amino acid digestibility in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022;64:740–751. doi: 10.5187/jast.2022.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . 18th ed. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem.; Gaithersburg, MD: 2005. Official Methods of Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Baker K.M., Utterback P.L., Parsons C.M., Stein H.H. Nutritional value of soybean meal produced from conventional, high-protein, or low-oligosaccharide varieties of soybeans and fed to broiler chicks. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:390–395. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszkiewicz, T. 2011. Nutritional value of soybean meal. Pages 1-20 in Soybean and Nutrition. H.A. EI-Shemy, ed. London, UK.

- Bertechini A.G., Kato R.K., d. Freitas L.F.V.-B., d. C. Castro R.T., Mazzuco H. Metabolizable energy values of soybean meals and soybean oil for broilers at different ages. Acta. Sci. Anim. Sci. 2019;41 [Google Scholar]

- Brumano G., Gomes P.C., Albino L.F.T., Rostagno H.S., Generoso R.A.R., Schmidt M. Chemical composition and metabolizable energy values of protein feedstuffs to broilers at different ages. Rev. Bras. Zootecn. 2006;35:2297–2302. [Google Scholar]

- Chibowska M., Smulikowska S., Pastuszewska B. Metabolisable energy value of rapeseed meal and its fractions for chickens as affected by oil and fibre content. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2000;9:371–378. [Google Scholar]

- CVB . Centraal Veevoeder Bureau; Lelystad, the Netherlands: 2018. Livestock Feed Table (Veevoedertabel): Feed Evaluation Systems for Poultry. [Google Scholar]

- Ding P., Huang X., Song Z., Fan Z., Guo Y., He X. Evaluation and prediction model of metabolic energy of rapeseed meal for broilers. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2019;50:2449–2457. [Google Scholar]

- Downey R., Bell J. In: Pages 37-46 in Canola and Rapeseed. Production, Chemistry, Nutrition and Processing Technology. Shahidi F., editor. Van Nosytand Reinhold; New York, NY: 1990. New developments in canola research. [Google Scholar]

- Florou-Paneri P., Christaki E., Giannenas I., Bonos E., Skoufos I., Tsinas A., Tzora A., Peng J. Alternative protein sources to soybean meal in pig diets. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2014;12:655–660. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo A., Moschini M., Cerioli C., Masoero F. Use of principal component analysis to classify forages and predict their calculated energy content. Animal. 2013;7:930–939. doi: 10.1017/S1751731112002467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Rodríguez J., Ranilla M.J., France J., Alaiz-Moretón H., Carro M.D., López S. Chemical composition, in vitro digestibility and rumen fermentation kinetics of agro-industrial by-products. Animals. 2019;9:861. doi: 10.3390/ani9110861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A., Tai K. 2012 proceedings of international conference on modelling, identification and control. IEEE; 2012. Comparison of regression analysis, artificial neural network and genetic programming in handling the multicollinearity problem; pp. 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hill F.W., Anderson D.L. Comparison of metabolizable energy and productive energy determinations with growing chicks. J. Nutr. 1958;64:587–603. doi: 10.1093/jn/64.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill F.W., Anderson D.L., Renner R., Carew L.B. Studies of the metabolizable energy of grain and grain products for chickens. Poult. Sci. 1960;39:573–579. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q., Hua W., Yin Y., Zhang X., Liu L., Shi J., Zhao Y., Qin L., Chen C., Wang H. Rapeseed research and production in China. Crop J. 2017;5:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen W.M.M.A. 3rd ed. Spelderholt Center for Poultry Research and Information Services; Beekbergen, Netherlands: 1989. European Table of Energy Values for Poultry Feedstuffs. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Wu W., Guo Y., Ban Z., Zhang B. Nutrient levels of soybean meal combinations in different ratios and prediction model establishment of metabolizable energy for broilers. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2021;33:3799–3809. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Moreno E., González-Alvarado J., Lázaro R., Mateos G. Effects of type of cereal, heat processing of the cereal, and fiber inclusion in the diet on gizzard pH and nutrient utilization in broilers at different ages. Poult. Sci. 2009;88:1925–1933. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe I.T., Cadima J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2016;374 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek P., Korniewicz D., Lipiński K., Mazur M. Chemical composition of rapeseed products and their use in pig nutrition. Pol. J. Natur. Sci. 2016;31:545–562. [Google Scholar]

- Khajali F., Slominski B.A. Factors that affect the nutritive value of canola meal for poultry. Poult. Sci. 2012;91:2564–2575. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D., Wang H., Yang J., Chen X., Peng F., Li T. Study on selected pelleting properties of different wheat varieties based on the principal component and cluster analysis. 2015 ASABE Annual International Meeting; Michigan; St. Joseph; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Cheng J., Yuan Y., Luo R., Zhu Z. Age-related intestinal monosaccharides transporters expression and villus surface area increase in broiler and layer chickens. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020;104:144–155. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Qi G., Sun S., Stamm M., Wang D. Physicochemical properties and adhesion performance of canola protein modified with sodium bisulfite. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 2012;89:897–908. [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Jiang S., Hong P., Gou Z., Chen F., Li L., Ding F. Comparison on Gastrointestinal Digestive Enzymes between Ross White Chicken and Yellow-feather Chicken. China Poult. 2017;39:26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Livesey G. Metabolizable energy of macronutrients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995;62:1135S–1142S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.5.1135S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medic J., Atkinson C., Jr C.R.H. Current knowledge in soybean composition. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 2014;91:363–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Technical Regulation of Nutritional Value Evaluation and Establishment of Parameters for Feed Ingredients. Bureau of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Beijing, 2020.

- Musigwa S., Morgan N., Swick R., Cozannet P., Wu S.B., Musigw S., Morgan N., Swick R., Cozannet P., Wu S.B. Optimisation of dietary energy utilisation for poultry-a literature review. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2021;77:5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pope M., Borg B., Boyd R.D., Holzgraefe D., Rush C., Sifri M. Quantifying the value of soybean meal in poultry and swine diets. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023;32 [Google Scholar]

- Qin G.X., Verstegen M.W.A., van der Poel A.F.B. Effect of temperature and time during steam treatment on the protein quality of full-fat soybeans from different origins. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998;77:393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S.U., McCoy E., Raza G., Ali Z., Mansoor S., Amin I. Improvement of soybean; a way forward transition from genetic engineering to new plant breeding technologies. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023;65:162–180. doi: 10.1007/s12033-022-00456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman H.U., Vahjen W., Awad W.A., Zentek J. Indigenous bacteria and bacterial metabolic products in the gastrointestinal tract of broiler chickens. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2007;61:319–335. doi: 10.1080/17450390701556817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shires A., Robblee A., Hardin R., Clandinin D. Effect of the age of chickens on the true metabolizable energy values of feed ingredients. Poult. Sci. 1980;59:396–403. [Google Scholar]

- Smulikowska S. Relationship between the stage of digestive tract development in chicks and the effect of viscosity reducing enzymes on fat digestion. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 1998;7:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- So K.K., Duncan R.W. Breeding canola (Brassica napus L.) for protein in feed and food. Plants. 2021;10:2220. doi: 10.3390/plants10102220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejeda O.J., Kim W.K. Role of dietary fiber in poultry nutrition. Animals. 2021;11:461. doi: 10.3390/ani11020461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toghyani M., Rodgers N., Barekatain M.R., Iji P.A., Swick R.A. Apparent metabolizable energy value of expeller-extracted canola meal subjected to different processing conditions for growing broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:2227–2236. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest P.J., Robertson J.B., Lewis B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wu Y., Mahmood T., Chen J., Yuan J. Age-dependent response to fasting during assessment of metabolizable energy and total tract digestibility in chicken. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Yu Y., Chen J., Zou Y., Liu S., Tan H., Zhao F., Wang Y. Evaluation of lipid sources and emulsifier addition on fat digestion of yellow-feathered broilers. J. Anim. Sci. 2022;100:skac185. doi: 10.1093/jas/skac185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegani M., Swift M.L., Zijlstra R.T., Korver D.R. Prediction of energetic value of wheat and triticale in broiler chicks A chick bioassay and an in vitro digestibility technique. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2013;183:40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Kim S.Y., Lee J.S., Shin B.K., Seo J.A., Kim Y.S., Lee D.Y., Choi H.K. Discrimination of the geographical origin of soybeans using NMR-based metabolomics. Foods. 2021;10:435. doi: 10.3390/foods10020435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]