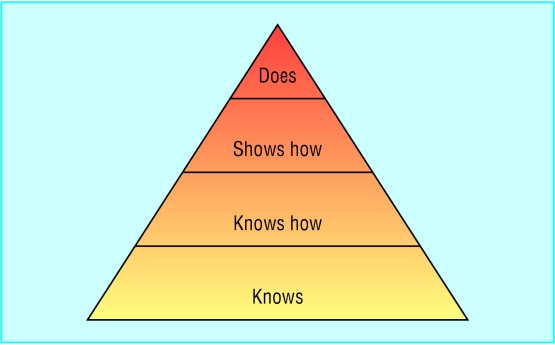

In 1990 psychologist George Miller proposed a framework for assessing clinical competence. At the lowest level of the pyramid is knowledge (knows), followed by competence (knows how), performance (shows how), and action (does). In this framework, Miller distinguished between “action” and the lower levels. “Action” focuses on what occurs in practice rather than what happens in an artificial testing situation. Work based methods of assessment target this highest level of the pyramid and collect information about doctors' performance in their normal practice. Other common methods of assessment, such as multiple choice questions, simulation tests, and objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) target the lower levels of the pyramid. Underlying this distinction is the sensible but still unproved assumption that assessments of actual practice are a much better reflection of routine performance than assessments done under test conditions.

This article explains what is meant by work based assessment and presents a classification scheme for current methods

Methods

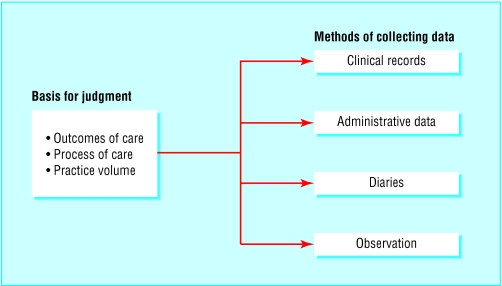

Although the focus of this article is on practising doctors, work based assessment methods apply to medical students and trainees as well. These methods can be classified in many ways, but this article classifies them in two dimensions. The first dimension describes the basis for making judgments about the quality of performance. The second dimension is concerned with how data are collected.

Basis for judgment

Outcomes

In judgments about the outcomes of their patients, the quality of a cardiologist, for example, might be judged by the mortality of his or her patients within 30 days of acute myocardial infarction. Historically, outcomes have been limited to mortality and morbidity, but in recent years the number of clinical end points has been expanded. Patients' satisfaction, functional status, cost effectiveness, and intermediate outcomes—for example, HbA1c and lipid concentrations for diabetic patients—have gained acceptance.

Three aspects of doctors' performance can be assessed—patients' outcomes, process of care, and volume of practice

Patients' outcomes are the best measures of the quality of doctors for the public, the patients, and doctors themselves. For the public, outcomes assessment is a measure of accountability that provides reassurance that the doctor is performing well in practice. For individual patients, it supplies a basis for deciding which doctor to see. For doctors, it offers reassurance that their assessment is tailored to their unique practice and based on real work performance.

Despite the fact that an assessment of outcomes is highly desirable, at least four substantial problems remain. These are attribution, complexity, case mix, and numbers.

Firstly, for a good judgment to be made about a doctor's performance, the patients' outcomes must be attributable solely to that doctor's actions. This is not realistic when care is delivered within systems and teams. Secondly, patients with the same condition will vary in complexity depending on the severity of their illness, the existence of comorbid conditions, and their ability to comply with the doctor's recommendations. Although statistical adjustments may tackle these problems, they are not completely effective. So differences in complexity directly influence outcomes and make it difficult to compare doctors or set standards for their performance. Thirdly, unevenness exists in the case mix of different doctors, again making it difficult to compare performance or to set standards. Finally, to estimate well a doctor's routine performance, a sizeable number of patients are needed. This limits outcomes assessment to the most frequently occurring conditions.

Process of care

In judgments about the process of care that doctors provide, a general practitioner, for example, might be assessed on the basis of how many of his or her patients aged over 50 years have been screened for colorectal cancer. General process measures include screening, preventive services, diagnosis, management, prescribing, education of patients, and counselling. In addition, condition specific processes might also serve as the basis for making judgments about doctors—for example, whether diabetic patients have their HbA1c monitored regularly and receive routine foot examinations.

Measures of process of care have substantial advantages over outcomes. Firstly, the process of care is more directly in the control of the doctor, so problems of attribution are greatly reduced. Secondly, the measures are less influenced by the complexity of patients' problems—for example, doctors continue to monitor HbA1c regardless of the severity of the diabetes. Thirdly, some of the process measures, such as immunisation, should be offered to all patients of a particular type, reducing the problems of case mix.

The major disadvantage of process measures is that simply doing the right thing does not ensure the best outcomes for patients. That a physician regularly monitors HbA1c, for example, does not guarantee that he or she will make the necessary changes in management. Furthermore, although process measures are less susceptible to the difficulties of attribution, complexity, and case mix, these factors still have an adverse influence.

For a sound assessment of an individual doctor's process of care, a sizeable number of patients need to be included

Volume

Judgments about the number of times that doctors have engaged in a particular activity might include, for example, the number of times a surgeon performed a certain surgical procedure. The premise for this type of assessment is the large body of research showing that quality of care is associated with higher volume.

Advantages of volume based assessment over assessment of outcomes and process

Problems of attribution are reduced substantially

Complexity is eliminated

Case mix is not relevant

However, such assessment alone offers no assurance that the activity was conducted properly

Data collection

Clinical practice records

One of the best sources of information about outcomes, process, and volume is the clinical practice record. The external audit of these records is a valid and credible source of data. Two major problems exist, however, with clinical practice records.

Firstly, judgment can be made only on what is recorded —this may not be an accurate assessment of what was actually done in practice.

Secondly, abstracting records is expensive and time consuming and is made cumbersome by the fact that they are often incomplete or illegible.

Widespread adoption of the electronic medical record may be the ultimate solution, although this is some years away. Meanwhile, some groups rely on doctors to abstract their own records and submit them for evaluation. Coupled with an external audit of a sample of the participating doctors, this is a credible and feasible alternative.

Administrative databases

In some healthcare systems large computerised databases are often developed as part of the process of administering and reimbursing for health care. Data from these sources are accessible, inexpensive, and widely available. They can be used in the evaluation of some aspects of practice performance—such as cost effectiveness—and of medical errors. However, the lack of clinical information and the fact that the data are often collected for invoicing purposes makes them unsuitable as the only source of information.

Databases for clinical audit are becoming more available and may provide more useful information relating to clinical practice

Peer evaluation rating forms

Below are the aspects of competence assessed with the peer rating form developed by Ramsey and colleagues.* The form, given to 10 peers, provides reliable estimates of two overall dimensions of performance: cognitive and clinical skills, and professionalism.

| Cognitive and clinical skills | Professionalism |

| • Medical knowledge | • Respect |

| • Ambulatory care | • Integrity |

| • Management of complex problems | • Psychosocial aspects |

| • Management of hospital inpatients | of illness |

| • Problem solving | • Compassion |

| • Overall clinical competence | • Responsibility |

*Ramsey PG et al. Use of peer ratings to evaluate physician performance. JAMA 1993;269:1655-60

Diaries

Doctors, especially trainees, may use diaries or logs to record the procedures they perform. Depending on the purpose of the diary, entries can be accompanied by a description of the doctor's role, the name of an observer, an indication of whether it was done properly, and a list of complications. This is a reasonable way to collect data on volume and an acceptable alternative to the abstraction of clinical practice records until medical records are kept electronically.

Observation

Data can be collected in many ways through practice observation, but to be consistent with Miller's definition of work based assessment, the observations need to be routine or covert to avoid an artificial test situation. They can be made in any number of ways and by any number of different observers. The most common forms of observation based assessment are ratings by supervisors, peers, and patients. Other examples of observation include visits by standardised patients (lay people trained to present patient problems realistically) to doctors in their surgeries and audiotapes or videotapes of consultations such as those used by the General Medical Council.

Patient rating form*

The form is given to 25 patients and gives a reliable estimate of a doctor's communication skills. Scores are on a five point scale—poor to excellent—and are related to validity measures. The patients must be balanced in terms of age, sex, and health status. Typical questions are:

• Tells you everything?

Greets you warmly?

Treats you as if you're on the same level?

Lets you tell your story?

Shows interest in you as a person?

Warns you what is coming during the physical examination?

Discusses options?

Explains what you need to know?

Uses words you can understand?

*Webster GD. Final report of the patient satisfaction questionnaire study. American Board of Internal Medicine, 1989

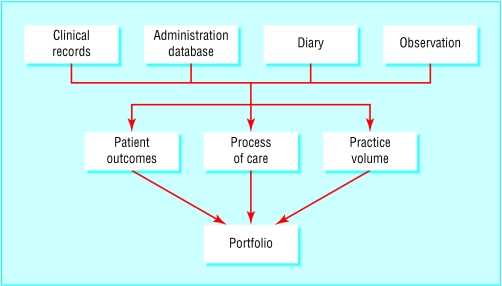

Portfolios

Doctors typically collect from various sources the practice data they think pertinent to their evaluation. A doctor's portfolio might contain data on outcomes, process, or volume, collected through clinical record audit, diaries, or assessments by patients and peers. It is important to specify what to include in portfolios as doctors will naturally present their best work, and the evaluation of it will not be useful for continuing quality improvement or quality assurance. In addition, if there is a desire to compare doctors or to provide them with feedback about their relative performance, then all portfolios must contain the same data collected in a similar fashion. Otherwise, there is no basis for legitimate comparison or benchmarking.

Further reading

McKinley RK, Fraser RC, Baker R. Model for directly assessing and improving competence and performance in revalidation of clinicians. BMJ 2001;322:712-5

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990:S63-7.

Norcini JJ. Recertification in the United States. BMJ 1999;319:1183-5

Cunningham JPW, Hanna E, Turnbull J, Kaigas T, Norman GR. Defensible assessment of the competency of the practicing physician. Acad Med 1997;72:9-12

Figure.

Miller's pyramid for assessing clinical competence

Figure.

Classification for work based assessment methods

Figure.

Care is delivered in teams, so judging a doctor's performance through outcomes is not realistic

Figure.

Unevenness in case mix can reduce usefulness of using patients' outcomes as a measure of doctors' competence

Figure.

Judgments on process of care might include foot examinations for diabetic patients

Figure.

Traditional medical records may give way to widespread use of electronic records, making data collection easier and quicker

Figure.

How portfolios are compiled

Acknowledgments

The photograph of a surgical team is from Philippe Plailly/Eurelios/SPL; the photographs illustrating case mix are from Photofusion, by David Tothill (left) and Pete Addis (right); the photograph of the foot is from Ray Clarke (FRPS) and Mervyn Goff (FRPS/SPL); and the medical records photograph is from Michael Donne/SPL.

Footnotes

John J Norcini is president and chief executive officer of the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The ABC of learning and teaching in medicine is edited by Peter Cantillon, senior lecturer in medical informatics and medical education, National University of Ireland, Galway, Republic of Ireland; Linda Hutchinson, director of education and workforce development and consultant paediatrician, University Hospital Lewisham; and Diana F Wood, deputy dean for education and consultant endocrinologist, Barts and the London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London. The series will be published as a book in late spring.