Abstract

Precision radiotherapy is a critical and indispensable cancer treatment means in the modern clinical workflow with the goal of achieving “quality-up and cost-down” in patient care. The challenge of this therapy lies in developing computerized clinical-assistant solutions with precision, automation, and reproducibility built-in to deliver it at scale. In this work, we provide a comprehensive yet ongoing, incomplete survey of and discussions on the recent progress of utilizing advanced deep learning, semantic organ parsing, multimodal imaging fusion, neural architecture search and medical image analytical techniques to address four corner-stone problems or sub-problems required by all precision radiotherapy workflows, namely, organs at risk (OARs) segmentation, gross tumor volume (GTV) segmentation, metastasized lymph node (LN) detection, and clinical tumor volume (CTV) segmentation. Without loss of generality, we mainly focus on using esophageal and head-and-neck cancers as examples, but the methods can be extrapolated to other types of cancers. High-precision, automated and highly reproducible OAR/GTV/LN/CTV auto-delineation techniques have demonstrated their effectiveness in reducing the inter-practitioner variabilities and the time cost to permit rapid treatment planning and adaptive replanning for the benefit of patients. Through the presentation of the achievements and limitations of these techniques in this review, we hope to encourage more collective multidisciplinary precision radiotherapy workflows to transpire.

Keywords: Organs at risk, Target tumor volume, Radiation therapy

1. Introduction

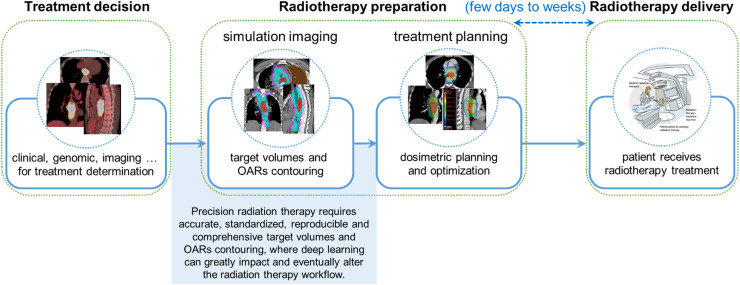

Radiation therapy is one of the vital therapies that 50% of cancer patients are estimated to receive during their treatment courses.1 Precision radiation therapy promising to alleviate the human observer performance variations and the inequality of healthcare delivery across different geographical regions and healthcare systems is in high demand nowadays. Although significant advancements have been made in the modern radiotherapy delivery techniques, one of the major barriers to precision radiotherapy is the lack of accurate, standardized, and automated contouring for the tumor target volumes and the organs at risk (OARs), which is highly correlated with tumor control and radiotherapy toxicities.2, 3, 4, 5 In current clinical practice, the delineation workflow of target volumes and OARs is one of the most essential yet time-consuming tasks that are performed mostly manually by radiation oncologists and/or physicists. It takes an average of at least three hours for them to delineate for a head-and-neck cancer patient.6, 7, 8, 9 This task can be undesirably overwhelming and expensive to healthcare systems on account of the increasing incidence of cancers, high demands for radiotherapy, and shortage of sufficiently trained clinicians.10,11 Moreover, manual contouring is subject to large inter-observer variations, even among board-certified clinical experts (i.e., senior radiation oncologists), leading to substantial differences in the final treatment plans.12,13 Fig. 1 illustrates the steps for target volume and OAR contouring in a typical radiation therapy treatment process.

Fig. 1.

Target volume and OAR contouring in a typical radiation therapy treatment process. The long time spent in the target volume and OAR contouring is often the key factor causing the long waiting time of patients. Images of esophageal cancer are used as examples. OAR, organs at risk.

Automated target volume and OAR segmentation using computerized algorithms have the potential to substantially shorten the contouring time, drive out the inter-observer variabilities, and eventually lead to precise and standardized radiation therapy. It may even permit (online) adaptive radiotherapy planning during the treatment course, which is largely an unmet need. However, early atlas- or registration-based methods failed to provide accurate target volume or OAR segmentation, and the extensive manual revisions required for correction of the segmentation limited its clinical applicability.14,15 With notable successes of deep learning techniques, recent works have demonstrated that deep learning-based target volume and OAR segmentation approaches can achieve performance on par with human experts, while significantly reducing the time and efforts required by manual editing.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Therefore, we are currently standing at the edge of transforming the radiotherapy contouring via deep learning-based auto-contouring tools. In this review, we provide a comprehensive yet ongoing survey of the recent progress in utilizing advanced deep learning, organ parsing, spatial modeling, multimodal imaging fusion, neural architecture auto-search, and medical image analytical techniques to holistically and precisely address the four corner-stone problems impeding the precision radiotherapy workflow. These problems are OAR segmentation, gross tumor volume (GTV) segmentation, clinical tumor volume (CTV) segmentation, and metastasized lymph node (LN) identification. Without loss of generality, we mainly focus on using esophageal and head-and-neck cancers as examples for illustration, but the methods themselves can be extrapolated to other types of cancers straightforwardly. Through the achievements and limitations shown in this review, we hope to encourage more collective multidisciplinary precision radiotherapy work to transpire, and eventually integrate the automated, precise, and reproducible OAR/GTV/CTV/LN auto-segmentation tools into the routine of radiotherapy clinical workflow to greatly benefit clinicians and the outcomes of patients.

2. Organs at risk contouring

In contrast to the target volumes receiving intense radiation energy to kill cancer cells, radiation doses to critical organs adjacent to the tumorous region should be controlled within safe limits to reduce post-treatment complications. This requires accurate OAR contouring on the simulation CT (simCT), so that radiation doses delivered to these critical organs can be correctly calculated. Manual OAR delineation is extremely time-consuming because of the large number of OARs, e.g., it at least takes 2∼3 h for a manual head-and-neck OAR contouring.7,8 To shorten the time expenses, many institutions choose a sometimes overly simplified OAR protocol by contouring only a small subset of OARs. This compromises the analysis of post-treatment side effects.34, 35, 36 Meanwhile, manual delineation also suffers from large inter-observer variations because clinicians often follow specific institutional protocols instead of the standardized delineation guidelines.37 Therefore, automated, accurate, and comprehensive OAR segmentation can significantly relieve the manual burden, guarantee a full-spectrum side effect analysis, and drive out the inter-observer variations, which eventually improves the treatment outcomes of patients.

Early automated OAR segmentation mostly utilized atlas-based approaches, which have limited accuracy and often require substantial manual revisions.38, 39, 40, 41, 42 This is because the image registration process, the core module in atlas-based approaches, cannot sufficiently handle the inter-patient variations, such as the shape and size differences, abnormal tissue growth or normal tissue removal, etc., and sometimes leads to complete failures. In contrast, the deep learning-based approaches have shown of being capable of producing significantly better performance than their atlas-based counterparts.17,43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 For head-and-neck cancers, FocusNet proposed a two-stage deep network workflow with an adversarial shape constraint to specifically focus on segmenting small OARs well among the overall 18 considered OARs.47 A mean Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of 0.73 was reported for 50 patients. In another work, a 3D UNet was trained using 663 CT scans to segment 21 OARs, and a surface DSC metric was introduced to compare the automated and the manual segmentation performances on 24 unseen testing patients.48 Results showed that the deep-learning model performed very close to those of two human observers, with slightly worse surface DSC scores. UaNet was proposed to segment 28 OARs by adopting a segmentation-by-detection strategy to achieve better segmentation accuracy in a testing cohort of 100 patients, where a mean DSC of 0.80 and a mean Hausdorff distance (HD) at 95th percentile of 6.2 mm were reported.17

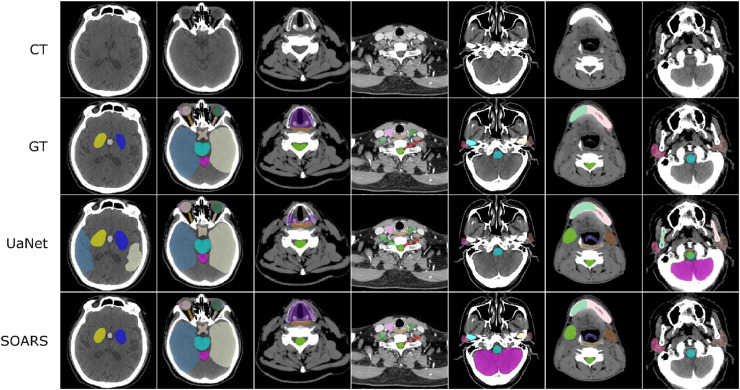

Recently, Guo et al.49 introduced a stratified OAR segmentation (SOARS) method to accurately segment a comprehensive set of 42 head-and-neck OARs as recommended by the delineation consensus guideline.37 When the number of OARs is large (> 40), deep network optimization becomes increasingly difficult. To alleviate this problem and motivated by the insights from clinical practice, SOARS first divided the OARs into three levels based on their appearance and spatial complexity, i.e., anchor, mid-level, and small & hard (S&H). Anchor OARs are high in contrast and can be easily segmented first to provide reliably informative location references for segmenting harder organs. Mid-level OARs are low in contrast but are not inordinately small. Anchor-level predictions are incorporated as additional input to guide the mid-level OAR segmentation. S&H OARs are very small in size or very poor in contrast. Hence, a detection-by-segmentation strategy is specifically exploited to handle the particularly unbalanced distributions of organ categories. While SOARS provides a specialized workflow to better segment each OAR category, it is unlikely that the same deep network architecture suits each stratified category equally. Therefore, SOARS further deployed another stratification by using neural architecture search (NAS) to automatically determine the optimal neural network structure for each OAR category. This is achieved by utilizing the differentiable NAS,50,51 which permits the automatic selection between 2D, 3D or pseudo-3D (P3D) convolutions with kernel sizes of 3 or 5 pixels for each convolutional block in the segmentation network. Cross-validated on 142 patients with 42 annotated OARs, SOARS achieved mean DSC and HD of 0.75 and 7.0 mm, respectively, representing concrete improvements of 5% for DSC and 2.2 mm for HD over the UaNet model.17

More importantly, SOARS also addresses the essential questions regarding the clinical applicability and generality of OAR segmentation for the first time20: (1) Does SOARS generalize well in a large-scale multi-institutional evaluation? (2) How much manual editing effort is required before the predicted OARs can be considered as clinically acceptable under the clinical delineation guideline? and more critically, (3) What are the dosimetric variations brought by OAR contouring differences in the downstream radiotherapy planning stage? To fully answer these questions, 1327 unseen patients from six institutions were enrolled into a multi-institutional testing set, where OAR annotations are examined/edited to ensure compliance with the delineation consensus guideline.37 Results showed that SOARS generalized well to the external multi-institutional testing, with a mean DSC of 0.78 and an average surface distance (ASD) of 1 mm in 25 OARs, consistently outperforming the UaNet17 by 3–5% of absolute DSC and 17–36% of relative ASD in all six institutions (Fig. 2). In a multiuser study consisting of 30 patients, 98% of SOARS-predicted OARs required no revision or very minor revision from radiation oncologists before they were clinically acceptable under the criteria of the guideline,37 and the manual contouring time could be shortened by 90%. In a subsequent dosimetric experiment, while fixing the original dose grid in a clinical intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) plan, the clinical reference OAR contours were replaced by SOARS predicted contours and another human reader's contours, respectively, to analyze the OARs dosimetric accuracy brought by the OAR contouring differences. Dosimetric results demonstrated that SOARS predicted OAR contours led to a maximum dose difference of 3.5% and a mean dose difference of 4.8% when averaged across 13 OARs, which are comparable to or smaller than those brought by the inter-observer contouring variations. Moreover, only 6% of SOARS predicted OAR instances had a mean dose error of larger than 10%. These preliminary dosimetric results indicated that SOARS predicted OAR contours could have a positive impact on downstream dose planning.

Fig. 2.

Qualitative 42 OAR segmentation using SOARS on the unseen multi-institutional validation. Columns show samples from different institutions. The three rows are simulation CT image, simulation CT with manual OAR delineations, simulation CT with UaNet predictions, and simulation CT with SOARS predictions, respectively. CT, computed tomography; OAR, organ at risk; SOARS, stratified OAR segmentation. Figure is modified, with permission, from Ref.20

OAR contouring is sometimes under-emphasized by clinicians in the radiotherapy practice as compared with target volume contouring. In one aspect, high inter-institutional and inter-observer contouring differences exist, because clinicians often follow the institution-specific OAR contouring style even if there exists the delineation consensus guideline. On the other hand, the large number of OARs hinders careful manual contouring due to the overwhelming time cost. Therefore, automated, standardized, and comprehensive OAR segmentation is in tremendous demand. As recent works have demonstrated that the deep learning model can segment a comprehensive set of OARs with high contouring accuracy (within inter-observer contouring variation), and lead to high dosimetric accuracy (within inter-observer variation), we believe that deep learning-based OAR segmentation is ready to be broadly applied to radiotherapy workflows to increase the quality of OAR contouring and subsequently help with the post-treatment complication analysis.

3. GTV contouring

GTV refers to the demonstrable gross tumor region. Accurate GTV contouring has been shown to be able to improve patient prognosis.21 It also serves as the basis for CTV contouring. GTV contouring is mostly performed on the non-contrast simCT. Because of the low contrast between the GTV and surrounding tissues, clinicians often have to use additional guidance for contouring, such as multimodal images [magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), radiology reports, and other relevant clinical information, which is labor-intensive and highly variable depending on clinicians’ experiences. Nevertheless, recent deep learning-based works16,19 have demonstrated that they can achieve high accuracy and consistency of GTV segmentation when using the simCT, simMRI, or fusion of simCT and diagnostic FDG-PET.

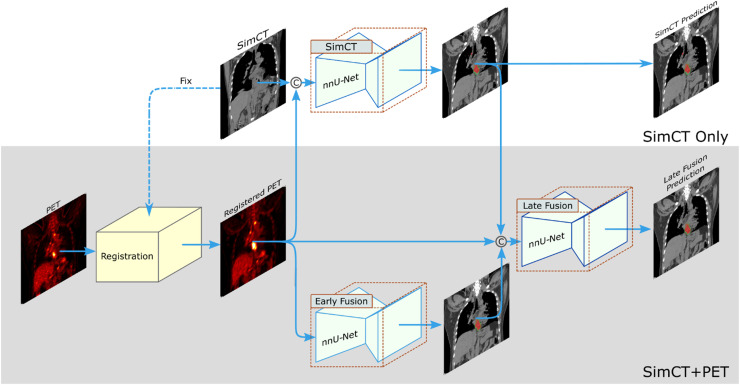

Take the esophageal GTV segmentation as an example. Manual contouring of esophageal GTV on simCT highly relies on the experiences of radiation oncologists, with notable inter-observer variability, especially along the esophagus vertical direction.22,23 Radiation oncologists almost always need to refer to other information, such as panendoscopy report, contrast-enhanced diagnostic CT or FDG-PET/CT, to determine the vertical tumor range along the esophagus. This “virtual fusion” of panendoscopy information, contrast-enhanced CT or FDG-PET into simCT in the minds of oncologists is a nontrivial process. Recent works have developed deep learning models to segment the esophageal GTV.24, 25, 26, 27 Notably, Jin et al.26,27 introduced a two-streamed deep learning framework to segment esophageal GTV, which has the flexibility to segment the GTV using only simCT or combining simCT with diagnostic PET/CT when available (Fig. 3). The simCT stream is trained using the simCT input alone, while the other stream uses an early fusion module of simCT and registered PET input channels, followed by a late fusion module to generate the final GTV segmentation via utilizing the complementary information in CT and PET. A deformable registration with robust lung-guided initialization28,29 is developed to robustly register the simCT and PET/CT. A 3D progressive semantically nested network (PSNN) is utilized as the segmentation network. The two-streamed deep model achieved the leading esophageal GTV segmentation performance when verified by cross-validation using an internal dataset of 148 patients with paired simCT and diagnostic PET/CT scans. Later, Ye et al.19 extended the two-streamed deep model to a multi-institutional evaluation (104 unseen internal patients and 354 external patients from multiple centers) and examined its clinical applicability in their user studies. Quantitative results showed that mean DSC and ASD of 0.81 and 2.7 mm were achieved in the internal testing using the simCT scans and the model generalized well to the external testing, with mean DSC and ASD of 0.80 and 2.8 mm,19 respectively. In the user study, it was shown that 76% auto-segmented GTV contours needed minor or no revision (<10% slice editing), and 24% auto-segmented GTV contours required substantial manual revisions (>30% slice editing). Hence, the manual editing time needed by auto-segmented GTV contours is less than half of the time needed by manual delineation. When further compared against the performances of four radiation oncologists specialized in esophageal cancer treatment in the user study, the deep learning model achieved comparable accuracy in terms of DSC and ASD, while generally reducing the maximum segmentation error in terms of Hausdorff distance. Moreover, assisted by the auto-segmented GTV contours, the contouring accuracy of four radiation oncologists’ was all improved (average DSC: 0.82 vs. 0.84), and the inter-observer variation was substantially reduced by 38% as measured by the volumetric coefficient of variation. They also demonstrated that the simCT + PET stream could further boost the GTV segmentation accuracy. The limitation observed there is that the deep model obtained relatively lower performance for patients of clinical T2 stage disease as compared with those of advanced clinical tumor T stages, which may be due to the small amount of T2 patients (only 24 patients) distributed in the training cohort. Increasing the number of early-stage patients should be able to alleviate this concern.

Fig. 3.

Two-streamed 3D deep learning model for esophageal GTV segmentation using simCT and FDG-PET/CT scans. The simCT stream takes the simCT as input and produces the GTV segmentation prediction. The simCT+PET stream takes both simCT and PET/CT scans as input. It first aligns the PET to simCT by registering the diagnostic CT (accompanying PET scan) to simCT and applying the deformation field to further align PET to simCT. Then, it uses an early fusion module followed by a late fusion module to segment the esophageal GTV using the complementary information in simCT and PET. This workflow can accommodate to the availability of PET scans in different institutions. CT, computed tomography; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; GTV, gross tumor volume; simCT, simulation CT. Figure is modified, with permission, from Ref.19

Another notable example is the automated nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) GTV segmentation.16,30, 31, 32 Since NPC tumors are proximal to many critical organs densely distributed in the head-and-neck region, manual NPC GTV delineation needs to be extremely careful with intensive labor costs. Particularly, using the early fusion of four MRI sequences (T2, unenhanced T1, contrast-enhanced T1, and fat-suppressed T1), a 3D VoxResNet33 deep model was trained using 818 NPC patients, and subsequently tested in another 203 patients of the same institution.16 Median DSC and ASD of 0.79 and 2.0 mm from the testing patients were reported by the AI model, which are comparable to the performances of six experienced radiation oncologists and consistently better than those of two less-experienced radiation oncologists. Furthermore, 89% of deep model segmented contours were believed to be clinically satisfactory, with less than 20% volumetric revision. With the assistance of deep learning contours, the inter-observer variations were reduced by 36% in terms of the coefficient of variation and the contouring time was shortened by 39%. However, it should be noted that the training and testing data in this study came from the same institution, and cross institutional evaluation with the training and testing sets coming from different institutions is a more appropriate settings to validate the “real” performance of these machine learning models. One of the missing parts of recent deep learning based GTV segmentation is to consider the organ motion, which has a large impact on the implementation of radiotherapy. We encourage researchers to investigate in this issue in the future.

In summary, recent works have demonstrated that the reported deep learning models are capable of producing accurate GTV segmentation results (within inter-observer variation) using the non-contrast simCT, simCT with PET, or multisequence MRI. The majority of auto-segmented GTV contours need only minor or no manual revision, substantially reducing the overall manual interaction time. These results indicate that, in the future, well-developed GTV deep segmentation models would be considered to integrate into the current radiotherapy workflow to increase the contouring efficiency, consistency, and reproducibility.

4. Lymph node GTV contouring

Determination of lymph node GTV (GTVLN) is another indispensable component in the precision radiation therapy workflow and it is closely related to the CTV contouring process. Different from the enlarged LNs, short axis > 1 cm) recommended in the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) guideline,52 GTVLN should include any metastasis suspicious LNs, including enlarged LNs as well as other smaller ones, that are associated with a high PET signal or any metastasis signs in CT, such as necrosis.53,54 This is an extremely tedious, objective, and challenging task that requires high-level human expertise to assess LNs’ size/appearance and their spatial relationship and causality with the primary tumor. Because of the difficulties, very few studies have investigated the automated GTVLN identification.55, 56, 57 In contrast, plenty of works have been developed on automated algorithms for the enlarged LN detection, which are more suited for the radiology workflow.58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63

Zhu et al. explored the first deep learning-based approach for the esophageal GTVLN segmentation.56 Clinically, radiation oncologists often condition the analysis of GTVLN based on LNs’ distance/location with respect to the corresponding primary tumor location. For LNs proximal to the tumor, radiation oncologists can more readily identify them as GTVLN in the radiotherapy treatment. However, for LNs distal to the tumor, more strict criteria may be applied to tell if there are clear signs of metastasis, e.g., enlarged sizes, increased PET signals, and/or other CT-based evidence.53 Hence, the distance from the primary tumor plays a key role in clinicians’ decision-making. By simulating the clinical diagnostic process, a distance-based gating strategy have been introduced to divide the underlying GTVLN distributions into “tumor-proximal” and “tumor-distal” categories, and a multi-branch deep network has been proposed to segment the two categories. Moreover, diagnostic PET scans have been concatenated with simCT as inputs into the deep network to capture GTVLN’s intensity, appearance, as well as its metastatic functional activities. Evaluated on 141 esophageal cancer patients with 651 annotated GTVLN, this method achieved a sensitivity of 0.74 with 6 false positives per patient. Later, considering that humans’ lymphatic system is a connected network of LNs, Chao et al. proposed a unified LN appearance (modeled by convolutional neural network) and inter-LN relationship learning (modeled by graph neural network) framework to classify the true GTVLN as a 2nd-stage model.57 The method achieved a sensitivity of 0.69 with 3 false positives per patient.

Although these results are encouraging, there are still performance gaps for fully automated GTVLN identification, which is also the current main roadblock for automated CTV contouring. Future works might need more accurate and consistent GTVLN annotations considering the human bias in the manual GTVLN contouring process. Meanwhile, further technical improvements are required to tackle this challenging problem by designing advanced detection, segmentation, and decision fusion deep learning models, and more precisely modeling the spatial relationship and clinical pathways between GTVLN and the primary tumors.

5. CTV contouring

CTV outlines the area that covers both the gross tumor and microscopic tumorous regions, i.e., sub-clinical diseases.21 Based on a mixture of predefined and judgment-based margins, CTV should spatially encompass the GTV, involved LNs, and sub-clinical disease regions, while restricting radiation to OARs. Even if the uncertainty of involved LNs is not considered, manual CTV delineation is difficult. Since it is not straightforward for humans to infer the accurate distance related margins, especially in 3D space, manual CTV delineation possesses even larger inter-observer variations as compared with the GTV, and its quality/stability/reliability highly depends on a clinician's experience. In this context, automated deep learning methods can play a key role in standardizing the CTV segmentation.

Early deep learning-based CTV segmentation mostly used only simCT as input. For instance, this method tried to predict the CTV margin of breast and rectal cancers by using only the appearance features in CT.44,64 However, this method can be ill-posed for other types of cancers, such as head-and-neck cancer and esophageal cancer, because the spatial configuration of the GTV, LNs, and OARs is essential to infer the CTV margin, which is completely ignored when using only CT as input. To provide the deep network with necessary spatial information, Cardenas et al.65 developed a stacked auto-encoder classification model to classify if a voxel belongs to the high-risk oropharyngeal CTV region based on the pure distance information between the GTV and surrounding anatomic structures, without considering the CT appearance. Using the nested leave-one-out cross-validation on 52 patients, a median DSC of 0.81 was achieved. Later, Cardenas et al. proposed to combine GTV and LN binary masks together as another input channel to additionally feed into a 3D UNet with the simCT for the oropharyngeal CTV segmentation.66 Trained on 210 patients, the deep learning model led to a mean DSC of 0.82. This work demonstrated the effectiveness of incorporating the spatial configurations of GTV and LNs into deep network learning.

Considering that binary GTV and LN masks do not explicitly provide distances to the model and OARs are not considered in Cardenas et al.66, Jin et al. explicitly provide spatial distance information from the GTV, involved LNs and OARs to segment the esophageal CTV.67 Instead of expecting the deep network to learn the distance-based margins from the GTV, LNs, and OARs binary masks, the 3D signed distance transform maps of these structures are directly utilized for the CTV inference. Specifically, the distance maps of GTV, LNs, lung, heart, and spinal canal with the simCT are fed into the network. From a clinical perspective, this allows the trained deep network to emulate a radiation oncologist's manual delineation, which uses the distances of GTV, LNs versus the OARs as key constraints in the determination of the CTV boundaries. Cross-validated on a dataset of 135 esophageal cancer patients, a mean DSC and ASD of 0.84 and 4.2 mm were achieved, representing noticeable improvements of 4% DSC and 2.4 mm ASD, respectively, over the previous leading method.66 Moreover, it was observed that 77% of patients had a Dice score ≥ 0.80, and 45% of patients had a Dice score ≥ 0.85. Considering the large inter-observer variations in CTV delineation tasks, these results may indicate that the automatically segmented CTVs require little to no manual revision for a majority of patients. It has also been demonstrated that appropriate problem formulation is the most important: once the spatial configuration is properly incorporated in the deep learning framework, the choice of baseline deep network structures has little effect on the final performance (UNet,68 PHNN,69 PSNN,67 or nnUNet70).

Another convention of CTV contouring in clinical practice is to include the metastasis-involved lymph node stations (LN station).71,72 This requires the delineation of LN station first, which is often defined according to surrounding key anatomic organs or landmarks, e.g., thoracic LN stations recommended by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC)73 and head & neck LN stations outlined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surger (AAO—HN).74 However, visual assessment with manual delineation of LN stations is a very challenging, expertise-demanding, and time-consuming task, because converting the textbook or guideline definitions of LN stations to precise 3D voxel-wise LN station annotations can be error-prone, which will lead to large intra and inter-user variability.75 In this context, automated LN station segmentation is of high criticalness to the CTV contouring task.76 Very few previous works62,77, 78, 79 have explored the problem of automated LN station segmentation, and limited performances have been reported due to the complexity and ambiguity of the definition of the boundary of LN stations. Notably, Guo et al. proposed DeepStationing,76 which is a deep learning based thoracic LN station segmentation method that explicitly encodes the key anatomical context to segment the LN stations. Specifically, a comprehensive set of 22 chest organs related to the description of thoracic LNs can be segmented first. Then, CT image and referencing organ prediction are combined as different input channels to the LN station segmentation module. Although 22 referencing organs are identified by human experts, the deep network may require a particular set of referencing organs (key organs) that can opt for optimal performance. After automatically searching for the key organs based on differentiable neural search,50 top 6 key organs, i.e., esophagus, aortic arch, ascending aorta, heart, spine, and sternum, are determined to achieve the highest LN station segmentation performance (mean DSC, ASD and HD of 0.81, 0.9 mm and 9.9 mm, respectively). This work indicated the technical feasibility to automate the CTV contouring based on delineating the associated LN stations.

6. Contouring quality assessment

Before deploying automated contouring tools into clinical practice, it is important to evaluate their contouring performance and examine the potential efforts for manual revisions. Meanwhile, it is highly recommended to validate the contouring performance using external datasets, since the generalizability to unseen patients from different institutions is one of the essential factors to successfully deploy the machine learning based tools. In this section, we first describe the necessary quantitative evaluation metrics, then introduce some helpful objective quality assessment criteria, and finally discuss the potential procedure for the quality assessment of deep learning generated contours before deploying them to the clinical workflow.

To comprehensively understand the quantitative segmentation/contouring performance, the following metrics are normally used80, 81, 82: DSC, Jaccard index, ASD, and HD (or HD95). DSC and the Jaccard index are the most frequently used metrics in medical image segmentation, and both characterize the volumetric overlap rate between the predicted region and the ground truth region. The two metrics are positively correlated and can be used equivalently. However, DSC or the Jaccard index alone is not sufficient to systematically evaluate the contouring results because of the volume dependence. For instance, small contouring errors in large targets affect slightly the DSC or Jaccard index, but those in small targets would significantly decrease the DSC or the Jaccard index. Hence, metrics related to distance errors should also be reported, e.g., ASD and HD or HD95. ASD indicates the average distance error from voxels on the boundary of the predicted region with respect to the boundary of the ground truth, and vice versa. HD or HD 95 illustrates the maximum distance error of boundaries between the predicted and the ground truth regions, which can reflect the false positive or false negative segmentation errors. A recent work proposed a surface DSC,48 which provides a measure of the overlap between the 3D surfaces of the predicted and ground truth regions. The motivation of using surface DSC is that the predicted contours would be potentially modified by clinicians, hence, the fraction of the surface that needs to be edited is the primary focus. In this scenario, the volumetric DSC is not well suited. However, organ-specific tolerances (in millimeter) need to be defined as a parameter of surface DSC, which requires appropriate clinical domain knowledge to get meaningful results.

Besides subjective evaluation metrics, recent works have proposed several objective metrics to define contours requiring minor revision or clinically acceptable contours. Objective evaluation metrics are important and useful because they indicate the editing efforts required when the predicted contours are used in real clinical practice. However, different studies tend to use various definitions for the minor revision or clinically acceptable contours. Lin et al.16 proposed to use the percentage of volumetric revision magnitudes to define minor and major revisions for the NPC GTV segmentation. E.g., if 0%−20% of a predicted segmentation volume needs to be edited, it refers to minor revision. Ye et al.19 defined the minor and major revisions using the percentage of slices needed to be edited for the esophageal GTV segmentation. If < 30% slices required editing, it is treated as minor revision. The use of various definitions for the clinically acceptable criterion may be due to the nature of different tumors. E.g., for esophageal cancer, tumors could grow along a large range of z slices in the elongated esophagus, while the nasopharyngeal carcinoma often occupies a limited range of z slice. Hence, the authors of the two works chose different objective metrics. Compared with the revised volume or slice percentage, a general and easily implemented definition of minor revision or clinically acceptable metric might be the percentage of time reduced when editing the auto-contour as compared with time spent on the pure manual delineation. For example, if the editing time of an auto-contour is reduced to less than 20% of manual delineation time, clinicians can refer to this case as minor revision or clinically acceptable.

It is important and beneficial to have a standard procedure for the quality assessment of deep learning generated contours before deploying them to the clinical practice in a given institution. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is still an open question in the field. Based on our experience, we suggest using the following tests and criteria for the quality assessment before the clinical deployment to a given institution. First, collect at least 100–200 testing patients with high-quality manually contoured target volumes or OARs by experienced senior radiation oncologists from the given institution. Then, apply the auto-contouring tools and evaluate the quantitative performance. Next, randomly select 30–50 patients from the testing cohort of the given institution and recruit several oncologists to edit the auto-contours and evaluate the clinically objective assessment metrics, such as the editing time, the revised volume or slices. Finally, for different target volumes and OARs, set their own acceptable criteria and assess if the auto-contouring tools should be used in clinical practice.

7. Conclusions

Significant advances in deep learning technology are at the edge of altering the current radiation therapy workflows. In this paper, we reviewed some of the recent progress of utilizing advanced deep learning, organ parsing, spatial modeling, multimodality imaging fusion, neural architecture auto-search and medical image analysis techniques to address four corner-stone problems in the domain of precision radiation therapy: GTV, CTV, and OAR segmentation and metastasized LN identification. Through all the achievements and limitations described and discussed, we hope to encourage more collective multidisciplinary precision radiotherapy work to transpire and bring fruition in the near future and for the many years to come. Comprehensive large-scale multicenter clinical study designs and continued relentless technical innovations in deep learning, computer vision, object detection, segmentation and parsing, and beyond are essentially intertwined and needed simultaneously. We strongly believe the deep learning-based high fidelity OAR, GTV, LN, and CTV contouring models are capable of significantly improving the accuracy, efficiency, and standardization in precision radiation therapy for better cancer patient treatment outcome and delivery. Another important thread of development that may be considered to be integrated into the radiotherapy is using radiological imaging and patient clinical information to predict patients’ overall survival and optimize different treatment plans.83,84 Yet, details of related works are beyond the scope of this review.

Declaration of competing interest

Dakai Jin, Dazhou Guo, Le Lu are employees of Alibaba Group, Inc. All authors declare that none of them have competing financial or non-financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the discussion to prepare this manuscript from Dr. Tsung-Ying Ho (Department of Nuclear Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital), Dr. Chen-Kan Tseng, and Dr. Chien-Yu Lin (Department of Radiation Oncology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital). We especially appreciate the help for preparing this manuscript from Dr. Tsung-Ying Ho, without whom this work cannot happen.

Author contributions

D.J. initiated the draft of this manuscript, and D.G., J.G. X.Y. and L.L. helped to complete this manuscript. D.J. and D.G. prepared the figures. They all discussed to determine the overall outline of this manuscript and contributed to finalize the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dakai Jin, Email: dakai.jin@alibaba-inc.com.

Xianghua Ye, Email: hye1982@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Delaney G., Jacob S., Featherstone C., et al. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilization from a review of evidence-based clinical guidelines. Cancer. 2005;104(6):1129–1137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters L.J., O'Sullivan B., Giralt J., et al. Critical impact of radiotherapy protocol compliance and quality in the treatment of advanced head and neck cancer: results from TROG 02.02. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):2996–3001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohri N., Shen X., Dicker A.P., et al. Radiotherapy protocol deviations and clinical outcomes: a meta-analysis of cooperative group clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(6):387–393. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker G.V., Awan M., Tao R., et al. Prospective randomized double-blind study of atlas-based organ-at-risk autosegmentation-assisted radiation planning in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;112(3):321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brade A.M., Wenz F., Koppe F., et al. Radiation therapy quality assurance (RTQA) of concurrent chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the PROCLAIM phase 3 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(4):927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong T., Tome W., Chappell R., et al. Variations in target delineation for head and neck IMRT: an international multi-institutional study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(1):S157–S158. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teguh D.N., Levendag P.C., Voet P.W., et al. Clinical validation of atlas-based auto-segmentation of multiple target volumes and normal tissue (swallowing/mastication) structures in the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(4):950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Macchia M., Fellin F., Amichetti M., et al. Systematic evaluation of three different commercial software solutions for automatic segmentation for adaptive therapy in head-and-neck, prostate and pleural cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2012;7(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoang Duc A.K., Eminowicz G., Mendes R., et al. Validation of clinical acceptability of an atlas-based segmentation algorithm for the delineation of organs at risk in head and neck cancer. Med Phys. 2015;42(9):5027–5034. doi: 10.1118/1.4927567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atun R., Jaffray D.A., Barton M.B., et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(10):1153–1186. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmore S.N.C., Prajogi G.B., Rubio J.A.P., et al. The global radiation oncology workforce in 2030: estimating physician training needs and proposing solutions to scale up capacity in low-and middle-income countries. Appl Radiat Oncol. 2019;8:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelms B.E., Tomé W.A., Robinson G., et al. Variations in the contouring of organs at risk: test case from a patient with oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daisne J.F., Blumhofer A. Atlas-based automatic segmentation of head and neck organs at risk and nodal target volumes: a clinical validation. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delpon G., Escande A., Ruef T., et al. Comparison of automated atlas-based segmentation software for postoperative prostate cancer radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2016;6:178. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y., Patwardhan K., Beichel R., et al. Impact of contouring accuracy on expected tumor control probability for head and neck cancer: semiautomated segmentation versus manual contouring. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(2):E545. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin L., Dou Q., Jin Y.M., et al. Deep learning for automated contouring of primary tumor volumes by MRI for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 2019;291(3):677–686. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019182012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang H., Chen X., Liu Y., et al. Clinically applicable deep learning framework for organs at risk delineation in CT images. Nat Mach Intell. 2019;1(10):480–491. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z., Liu X., Guan H., et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for auto-delineation of clinical target volume and organs at risk in cervical cancer radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2020;153:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye X., Guo D., Tseng C.K., et al. Multi-institutional validation of two-streamed deep learning method for automated delineation of esophageal gross tumor volume using planning-CT and FDG-PETCT. Front Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.785788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo D., Ge J., Ye X., et al. Comprehensive and clinically accurate head and neck organs at risk delineation via stratified deep learning: a large-scale multi-institutional study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.01544. 2021.

- 21.Burnet N.G., Thomas S.J., Burton K.E., et al. Defining the tumour and target volumes for radiotherapy. Cancer Imaging. 2004;4(2):153–161. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2004.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vesprini D., Ung Y., Dinniwell R., et al. Improving observer variability in target delineation for gastro-oesophageal cancer—the role of 18Ffluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Clin Oncol. 2008;20(8):631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nowee M.E., Voncken F.E., Kotte A., et al. Gross tumour delineation on computed tomography and positron emission tomography-computed tomography in oesophageal cancer: a nationwide study. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2019;14:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S., Yang H., Fu J., et al. U-net plus: deep semantic segmentation for esophagus and esophageal cancer in computed tomography images. IEEE Access. 2019;7:82867–82877. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yousefi S., Sokooti H., Elmahdy M.S., et al. Esophageal gross tumor volume segmentation using a 3D convolutional neural network. In Frangi A., Schnabel, J., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G. (eds). Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11073. Springer Cham.

- 26.Jin D., Guo D., Ho T.Y., et al. DeepTarget: gross tumor and clinical target volume segmentation in esophageal cancer radiotherapy. Med Image Anal. 2021;68 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin D., Guo D., Ho T.Y., et al. Accurate esophageal gross tumor volume segmentation in PET/CT using two-stream chained 3D deep network fusion. In:, et al. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention –MICCAI 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11765. Springer, Cham.

- 28.Heinrich M.P., Jenkinson M., Brady M., et al. MRF-based deformable registration and ventilation estimation of lung CT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2013;32(7):1239–1248. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2013.2246577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin D., Xu Z., Tang Y., et al. CT-Realistic lung nodule simulation from 3D conditional generative adversarial networks for robust lung segmentation. In: Frangi, A., Schnabel, J., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11071. Springer, Cham.

- 30.Ma Z., Zhou S., Wu X., et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma segmentation based on enhanced convolutional neural networks using multi-modal metric learning. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64(2) doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aaf5da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye Y., Cai Z., Huang B., et al. Fully-automated segmentation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma on dual-sequence MRI using convolutional neural networks. Front Oncol. 2020;10:166. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groendahl A.R., Knudtsen I.S., Huynh B.N., et al. A comparison of methods for fully automatic segmentation of tumors and involved nodes in PET/CT of head and neck cancers. Phys Med Biol. 2021;66(6) doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/abe553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen H., Dou Q., Yu L., et al. VoxResNet: deep voxelwise residual networks for brain segmentation from 3D MR images. Neuroimage. 2018;170:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Machtay M., Moughan J., Trotti A., et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: an RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsiao K.Y., Yeh S.A., Chang C.C., et al. Cognitive function before and after intensity-modulated radiation therapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(3):722–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen-Tan P.F., Zhang Q., Ang K.K., et al. Randomized phase III trial to test accelerated versus standard fractionation in combination with concurrent cisplatin for head and neck carcinomas in the radiation therapy oncology group 0129 trial: long-term report of efficacy and toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3858. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brouwer C.L., Steenbakkers R.J., Bourhis J., et al. CT-based delineation of organs at risk in the head and neck region: DAHANCA, EORTC, GORTEC, HKNPCSG, NCIC CTG, NCRI, NRG Oncology and TROG consensus guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2015;117(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han X., Hoogeman M.S., Levendag P.C., et al. Atlas-based auto-segmentation of head and neck CT images. In: Metaxas, D., Axel, L., Fichtinger, G., Székely, G. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 5242. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- 39.Isambert A., Dhermain F., Bidault F., et al. Evaluation of an atlas-based automatic segmentation software for the delineation of brain organs at risk in a radiation therapy clinical context. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87(1):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sims R., Isambert A., Grégoire V., et al. A pre-clinical assessment of an atlas-based automatic segmentation tool for the head and neck. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93(3):474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voet P.W., Dirkx M.L., Teguh D.N., et al. Does atlas-based autosegmentation of neck levels require subsequent manual contour editing to avoid risk of severe target underdosage? A dosimetric analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2011;98(3):373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schreibmann E., Marcus D.M., Fox T. Multiatlas segmentation of thoracic and abdominal anatomy with level set-based local search. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2014;15(4):22–38. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v15i4.4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kosmin M., Ledsam J., Romera-Paredes B., et al. Rapid advances in auto-segmentation of organs at risk and target volumes in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2019;135:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Men K., Geng H., Cheng C., et al. More accurate and efficient segmentation of organs-at-risk in radiotherapy with convolutional neural networks cascades. Med Phys. 2019;46(1):286–292. doi: 10.1002/mp.13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen W., Li Y., Dyer B.A., et al. Deep learning vs. atlas-based models for fast auto-segmentation of the masticatory muscles on head and neck CT images. Radiat Oncol. 2020;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13014-020-01617-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambert Z., Petitjean C., Dubray B., et al. SegTHOR: segmentation of thoracic organs at risk in CT images. arXiv:1912.05950.

- 47.Gao Y., Huang R., Chen M., et al. FocusNet: imbalanced large and small organ segmentation with an end-to-end deep neural network for head and neck CT images. Med Image Anal. 2021;67 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nikolov S., Blackwell S., Zverovitch A., et al. Clinically applicable segmentation of head and neck anatomy for radiotherapy: deep learning algorithm development and validation study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(7):e26151. doi: 10.2196/26151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo D., Jin D., Zhu Z., et al. Organ at risk segmentation for head and neck cancer using stratified learning and neural architecture search. arXiv:2004.08426.

- 50.Liu H., Simonyan K., Yang Y. Darts: differentiable architecture search. arXiv:1806.09055. 2018;

- 51.Liu C., Chen L.C., Schroff F., et al. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition – CVPR. 2019. Auto-deeplab: hierarchical neural architecture search for semantic image segmentation. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwartz L., Bogaerts J., Ford R., et al. Evaluation of lymph nodes with RECIST 1.1. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scatarige J.C., Fishman E.K., Kuhajda F.P., et al. Low attenuation nodal metastases in testicular carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1983;7(4):682–687. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198308000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vergalasova I., Mowery Y., Yoo D., et al. TU-F-12A-03: using 18F-FDG-PET-CT and deformable registration during head-and-neck cancer (HNC) intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) to predict treatment response. Med Phys. 2014;41(6Part28):480–481. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Z., Yan K., Jin D., et al. Detecting scatteredly-distributed, small, andcritically important objects in 3d oncologyimaging via decision stratification. arXiv:2005.13705. 2020.

- 56.Zhu Z., Jin D., Yan K., et al. Lymph node gross tumor volume detection and segmentation via distance-based gating using 3D CT/PET imaging in radiotherapy. In:, et al. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12267. Springer, Cham.

- 57.Chao C.H., Zhu Z., Guo D., et al. Lymph node gross tumor volume detection in oncology imaging via relationship learning using graph neural network. In:, et al. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention –MICCAI 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12267. Springer, Cham.

- 58.Barbu A., Suehling M., Xu X., et al. Automatic detection and segmentation of lymph nodes from CT data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2011;31(2):240–250. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2168234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feulner J., Zhou S.K., Hammon M., et al. Lymph node detection and segmentation in chest CT data using discriminative learning and a spatial prior. Med Image Anal. 2013;17(2):254–270. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bouget D., Jørgensen A., Kiss G., et al. Semantic segmentation and detection of mediastinal lymph nodes and anatomical structures in CT data for lung cancer staging. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2019;14(6):977–986. doi: 10.1007/s11548-019-01948-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roth H.R., Lu L., Liu J., et al. Improving computer-aided detection using convolutional neural networks and random view aggregation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;35(5):1170–1181. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2482920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J., Hoffman J., Zhao J., et al. Mediastinal lymph node detection and station mapping on chest CT using spatial priors and random forest. Med Phys. 2016;43(7):4362–4374. doi: 10.1118/1.4954009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nogues I., Lu L., Wang X., et al. Automatic lymph node cluster segmentation using holistically-nested neural networks and structured optimization in CT images. In: Ourselin, S., Joskowicz, L., Sabuncu, M., Unal, G., Wells, W. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention –MICCAI 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9901. Springer, Cham.

- 64.Men K., Dai J., Li Y. Automatic segmentation of the clinical target volume and organs at risk in the planning CT for rectal cancer using deep dilated convolutional neural networks. Med Phys. 2017;44(12):6377–6389. doi: 10.1002/mp.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cardenas C.E., McCarroll R.E., Court L.E., et al. Deep learning algorithm for auto-delineation of high-risk oropharyngeal clinical target volumes with built-in dice similarity coefficient parameter optimization function. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(2):468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cardenas C.E., Anderson B.M., Aristophanous M., et al. Auto-delineation of oropharyngeal clinical target volumes using 3D convolutional neural networks. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63(21) doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aae8a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jin D., Guo D., Ho T.Y., et al. Deep esophageal clinical target volume delineation using encoded 3D spatial context of tumors, lymph nodes, and organs at risk. In:, et al. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention –MICCAI 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11769. Springer, Cham.

- 68.Ronneberger O., Fischer P., Brox T. U-Net: convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In: Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W., Frangi, A. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention –MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 9351. Springer, Cham.

- 69.Harrison A.P., Xu Z., George K., et al. Progressive and multi-path holistically nested neural networks for pathological lung segmentation from CT images. In: Descoteaux, M., Maier-Hein, L., Franz, A., Jannin, P., Collins, D., Duchesne, S. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention − MICCAI 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 10435. Springer, Cham.

- 70.Isensee F., Jaeger P.F., Kohl S.A., Petersen J., Maier-Hein K.H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat Methods. 2021;18(2):203–211. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lim K., Small W., Jr, Portelance L., et al. Consensus guidelines for delineation of clinical target volume for intensity-modulated pelvic radiotherapy for the definitive treatment of cervix cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(2):348–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee A.W., Ng W.T., Pan J.J., et al. International guideline for the delineation of the clinical target volumes (CTV) for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2018;126(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rusch V.W., Asamura H., Watanabe H., et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):568–577. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d82e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robbins K.T., Clayman G., Levine P.A., et al. Neck dissection classification update: revisions proposed by the American Head and Neck Society and the American academy of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(7):751–758. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.7.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chapet O., Kong F.M., Quint L.E., et al. CT-based definition of thoracic lymph node stations: an atlas from the University of Michigan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(1):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo D., Ye X., Ge J., et al. DeepStationing: thoracic Lymph Node station parsing in CT scans using anatomical context encoding and key organ auto-search. In: de Bruijne M., Cattin P., Cotin S., et al. (eds.) Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention –MICCAI 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12905. Springer, Cham.

- 77.Feuerstein M., Glocker B., Kitasaka T., et al. Mediastinal atlas creation from 3-D chest computed tomography images: application to automated detection and station mapping of lymph nodes. Med Image Anal. 2012;16(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarrut D., Rit S., Claude L., et al. Learning directional relative positions between mediastinal lymph node stations and organs. Med Phys. 2014;41(6) doi: 10.1118/1.4873677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guo D., Yan K., Ge J., et al. Thoracic lymph node segmentation in CT imaging via lymph node station stratification and size encoding. In: Wang, L., Dou, Q., Fletcher, P.T., Speidel, S., Li, S. (eds) Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13435. Springer, Cham.

- 80.Warfield S., Zou K., Wells W. Simultaneous truth and performance level estimation (STAPLE): an algorithm for the validation of image segmentation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23(7):903–921. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.828354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharp G., Fritscher K.D., Pekar V., et al. Vision 20/20: perspectives on automated image segmentation for radiotherapy. Med Phys. 2014;41(5) doi: 10.1118/1.4871620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taha A., Hanbury A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med Imaging. 2015;15(1):1–28. doi: 10.1186/s12880-015-0068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cheng N.M., Yao J., Cai J., et al. Deep learning for fully automated prediction of overall survival in patients with oropharyngeal cancer using FDG-PET imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(14):3948–3959. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yao J., Cao K., Hou Y., et al. Deep learning for fully automated prediction of overall survival in patients undergoing resection for pancreatic cancer. A retrospective multi-center study. Ann Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005465. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]