Abstract

Pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA) variation is the genetic predisposition for high cancer risk affecting mostly breast and ovarian. BRCA variation information is widely used in clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of BRCA-related cancer. The positive selection imposed on human BRCA leads to highly ethnic-specific BRCA variation to adapt different living environment on earth. Most of the human BRCA variants identified so far were from the European descendant populations and used as the standard reference for global human populations, whereas BRCA variation in other ethnic populations remains poorly characterized. This review addresses the origin of ethnic-specific BRCA variation, the importance of ethnic-specific BRCA variation in clinical application, the limitation of current BRCA variation data, and potential solutions to fill the gap.

Keywords: BRCA variation, Pathogenic, Ethnicity, Cancer, Population, Evolution

1. Introduction

A genome is constantly damaged by environmental and metabolic factors. The damaged DNA must be repaired timely and spatially by different repairing mechanisms to avoid pathogenic consequences. The homologous recombination (HR) pathway repairs the double-strand DNA breaks to maintain genome stability. BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA hereafter) are two essential components in the HR pathway.1 Human BRCA is highly variable for better adaptation to different natural environment due to the positive selection imposed on human BRCA.2 However, a part of the BRCA variants is highly deleterious in damaging BRCA function, causing genome instability and increased cancer risk affecting mostly breast and ovarian, and other organs including prostate and pancreas.3 A woman carrying a pathogenic BRCA1 variant will have 55%−72% risk of developing breast cancer and 39%−44% risk of developing ovarian cancer, and a woman carrying a pathogenic BRCA2 variant will have 45%−69% risk of developing breast cancer and 11%−17% risk of developing ovarian cancer by 70–80 years old.4, 5, 6 About 10% of breast cancer are caused by hereditary predispositions in different genes, of which the pathogenic BRCA variation is the most significant one contributing up to 40% of the cases.7, 8, 9 Identification of pathogenic BRCA variants in non-cancer carriers is an effective way to prevent cancer development as it allows taking preventive actions before cancer occurs in the carriers.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In the meantime, identification of pathogenic BRCA variants in cancer patients is also a pre-condition for using the synthetic lethal-based poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPi) to treat breast and ovarian cancer as PARPi only works in the cancer with mutated BRCA .15 In the process, PARPi blocks PARP function of repairing single-strand breaks, causing the formation of double-strand break during DNA replication. The double-strand break can't be repaired through homologous recombination as BRCA is mutated, leading to the death of cancer cells.16 The increased application of the low-cost next generation DNA sequencing technologies has overcome a major obstacle in BRCA study under the high-cost Sanger sequencing platform. It allows collecting BRCA sequences and identifying BRCA variants in either general population or patient cohort by using BRCA-targeted sequencing, cancer gene panel-targeted sequencing, exome sequencing or even whole genome sequencing. BRCA1/BRCA2 are two of the best characterized cancer predisposition genes,17 and BRCA variants are the most used genetic markers in clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

2. Human BRCA is under positive selection

BRCA1 was arisen in animal and plant kingdoms 1.2 billion year ago, and BRCA2 in fungus, plant, and animal kingdoms 1.6 billion year ago.18,19 Extensive evolutionary studies have revealed that BRCA in most of the species is under negative selection, which reflects the importance of BRCA in maintaining genome stability. However, human BRCA is an exception that it is under positive selection.2,20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 As such, it would be expected that human BRCA should have been highly variable with large number of genetic variants. Indeed, nearly 70,000 human BRCA variants have been identified, an unusual phenomenon among all cancer predisposition genes. Strong positive selection on human BRCA implies that human BRCA must gain certain important function besides maintaining genome stability. Indeed, it has been shown that human BRCA is involved in many essential biological functions including infectious immunity,26 gene expression regulation,27 neural development,28 and reproduction.29

As the pathogenic BRCA variants are directly relevant to cancer, we studied evolutionary origin of pathogenic BRCA variation in modern human population.30 By tracing 2,972 pathogenic BRCA1 and 3,652 pathogenic BRCA2 variants in 100 vertebrates across eight clades, we found no evidence for their presence in other species including the primates, therefore, excluded cross-species reservation as the source for human pathogenic BRCA variants. We then performed an archeological analysis by searching the pathogenic variants in 2,792 ancient human genomes and 8 extinct hominins genomes of Neanderthal and Denisovan. While we identified no pathogenic BRCA variants in the hominin's genomes, we did identify 28 BRCA1 and 22 BRCA2 pathogenic variants in 44 ancient human genomes dated between 45,000 and 300 years ago, and most were within the last 5,000 years. We also analyzed the reported timing for the haplotyping-identified BRCA founder variants identified in modern human population. We observed that nearly all BRCA founder variants were arisen within the last 3,000 years. Based on the data, we proposed that human BRCA pathogenic variants were not originated from cross-species conservation but arisen during human evolution after out of Africa migration, mostly after the last glacial period of 10,000 years, particularly in the last 5,000 years following the great expansion of human population. Knowing the origin of BRCA pathogenic variants provides a foundation for understanding the biological basis of BRCA pathogenic variants and designing strategies for their medical applications.

The prevalence of BRCA pathogenic variation in human population reaches to the level of one in a few hundreds of individuals, for example, one in 384 in Japanese,31 one in 265 in Chinese Han and Mexican,32,33 one in 256 in Malaysian,34 one in 189 in American,35 and one in 46 in Ashkenazi Jews,36 In cancer cohorts, the prevalence reaches to about 5% in breast cancer patients and 20% in ovarian cancer patients.37,38 Such high prevalence implies that pathogenic BRCA predisposition is a serious threaten for public health. With the positive selection and continually expansion of human population, it is expected that more pathogenic BRCA variants would arise; and with widely application of new DNA sequencing technologies, more pathogenic BRCA variants would be identified.

3. Importance of BRCA variant reference for clinical application

A challenge in clinical BRCA application is to determine the pathogenicity of the BRCA variants identified in patients. These carrying pathogenic variants require to take active clinical prevention/treatment action, these carrying benign variant are not at increased cancer risk, whereas these carrying variant of uncertain significance (VUS) are at uncertain status for their cancer risk and requires frequent monitoring. Determination of different types of BRCA variant carriers depends heavily on the use of BRCA variant reference databases, e.g., the widely used ClinVar database. These databases contain the BRCA variants derived from the variant carriers with well-documented evidence, and annotate the variants into different classes of pathogenic, likely pathogenic, VUS, likely benign, and benign following the standard guidelines with strict criteria.39 Variants identified from the carriers will be searched in these BRCA variant reference databases. The variants matched in the databases will obtain the class information to decide the clinical actions. Therefore, the quality and quantity of BRCA reference databases play a key role in translating BRCA knowledge into patient care.

4. Ethnic specificity of human BRCA variation

The definition of ethnicity is “of or relating to large groups of people classed according to common racial, national, tribal, religious, linguistic, or cultural origin or background (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ethnic)”. Rich evidences have well revealed that human BRCA variation is highly ethnic-specific.40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 A typical example is the three pathogenic BRCA founder variants (BRCA1 c.68_69del, BRCA1 c.5266dupC, and BRCA2 c.5946delT) in Ashkenazi Jews population.47 Factors contributed to the ethnic specificity of BRCA variation include the positive selection imposed on human BRCA, the adaptation of different ethnic populations to their living environment, and the effects of bottleneck, genetic drift, and founder variation in different ethnic populations. BRCA1 pathogenic variation in European and descendent population is higher than BRCA2 variation, whereas BRCA2 variation in Asian population is higher than BRCA1 variation.48 BRCA variation in different ethnic populations can also cause different types of cancer. In European descendent population, the predominant cancer types caused by BRCA pathogenic variation are breast cancer and ovarian cancer, whereas BRCA2 pathogenic variation is linked with esophageal cancer in the northern Chinese,49 gastric cancer in Russian,50 and biliary tract cancer in Korean.51 In European descendent populations, the cumulative risk for developing ovarian cancer lifetime were 44% for BRCA1 pathogenic variant carriers and 17% for BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers,4 whereas in Chinese population, the risk was 15.3% for BRCA1 pathogenic variant carriers and 5.5% for BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers.52

Determination of ethnic-specificity of BRCA variation is important, as it provides geneticbased evidence to understand the relationship between human evolution and cancer risk, and provides ethnicity-based management to care the variant carriers. While existing evidence showed ethnic-specific human BRCA variation, most of the data were derived from the studies at limited scales. To provide more convincing evidence, we performed a series of population-based studies to address the ethnic-specific issue of human BRCA variation.

4.1. Evidence from worldwide ethnic populations

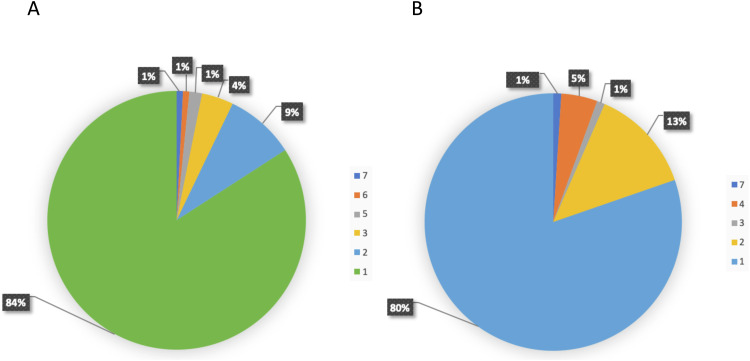

Different ethnic populations have different susceptibility to diseases. This has been proposed to be related with different load of disease predispositions in different populations.53, 54, 55 We investigated the distribution of pathogenic variants in 169 DNA damage repair (DDR) genes including BRCA, which are directly relevant to cancer predispositions, in all 9 DDR pathways. We analyzed 158,612 individuals in 16 different ethnic populations worldwide, including African/African-American, Ashkenazi Jewish, Bulgarian, Chinese, Estonian, European, Finnish, Icelander, Japanese, Korean, Latino/Admixed American, North-Western, Other East Asian, Other non-Finnish European, South Asian, Southern European, and Swedish.56 We identified 1,781 pathogenic variants in 81 DDR genes, in which BRCA2 had the highest number of pathogenic variants (196, 11.0%), and BRCA1 had the third highest ones (126, 7.1%). We observed that 84% of BRCA1 and 80% of BRCA2 pathogenic variants were present only in single populations, and the remaining 16% of BRCA1 and 20% of BRCA2 pathogenic variants were shared within a few ethnic populations with closer geographic or genetic connections (Fig. 1). The results showed that BRCA variation in the worldwide populations is highly ethnic-specific.

Fig. 1.

Ethnic-specific pathogenic BRCA variants in worldwide populations. We identified pathogenic BRCA variants in 158,612 individuals of 16 different ethnic populations of African/African American, Ashkenazi Jewish, Bulgarian, Chinese, Estonian, European, Finnish, Icelander, Japanese, Korean, Latino/Admixed American, North-Western, Other East Asian, Other non-Finnish European, South Asian, Southern European, and Swedish. Of the 322 (126 in BRCA1, 196 in BRCA2) pathogenic variants identified, 84% in BRCA1 and 80% in BRCA2 were present only in single populations.

4.2. Evidence from Asian population

Asian population has highly diversified genetic background. It has a population size of 4.7 billion or 60% of world population (https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/asia-population/), living in over 50 countries and regions under different geographic environment across Asia continent. It would be expected that BRCA variation in Asian population have its unique features.

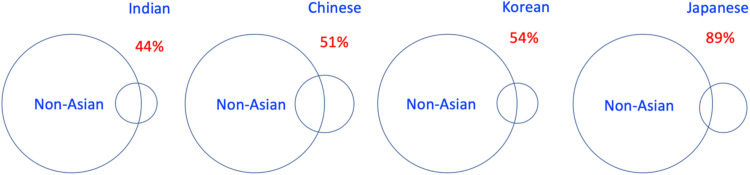

We systematically analyzed BRCA variation in Asian population.57,58 Using big-data approach, we identified 7,587 BRCA variants from nearly 700,000 cancer and non-cancer individuals reported in 40 Asia countries and regions. We observed that only 37 of the 7,589 (0.5%) BRCA variants were shared within Asian populations.58 We compared BRCA variant data between non-Asian population and Asian populations of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese. The results showed that the rate of difference in each Asian population increased following the increased geographic distance between Europe and each Asia country: 44.2%, 51.2%, 54.2%, 88.9% of BRCA variants in Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese were only present in its own population (Fig. 2).57 The results demonstrate that BRCA variation in the Asian populations is highly ethnic-specific.

Fig. 2.

Ethnic-specific BRCA variation in Asian populations. We identified 7,587 BRCA variants from nearly 700,000 cancer and non-cancer individuals in 40 Asia countries and regions. We compared the BRCA variant data between non-Asian population and Asian populations of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese. The rate of difference between non-Asian population and Asia countries of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese were 44.2%, 51.2%, 54.2%, 88.9%.

BRCA study in the Japanese population provides a vivid example for the importance of ethnic specific BRCA variation and its value for clinical applications. BRCA study in Japanese cancer patients was reported soon after BRCA was identified in 1994.59, 60, 61 Despite of the rapid action, it is interesting to note that Japanese BRCA study remained at very low profile in the past two decades since the initial reports.62 A possible explanation is that the early studies used the European descendant populationderived BRCA variant data as the reference, which could have shown low match rate. This could give the impression that the prevalence of BRCA variation in Japanese population may not be higher enough to reach clinical significance, therefore, not worth of putting efforts on the subject. However, the situation changed rapidly in recent years when the NGS-generated BRCA data from Japanese population showed that the prevalence of BRCA variation in Japanese population and cancer patients is at similar level as in other ethnic populations and the spectrum of BRCA variation is highly Japanese-specific (Fig. 2). For example, a study in 7,051 breast cancer cases and 11,241 controls identified 1,781 BRCA variants, of which 244 (15.6%) were pathogenic variants, 356 (20%) benign variants and 1,181 (66.3%) were VUS variants.31 This promoted the rapid response in Japanese scientific and medical community, including the establishment of a nationwide network for BRCA-related cancer, the development of Japanese “Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) Database”,63 and the insurance coverage for clinical BRCA test and treatment for high-risk individuals by Japanese national insurance system.64

4.3. Evidence from African population

Based on the ‘Out of Africa’ theory, African is the origin of modern human population around the world. Our study of human BRCA pathogenic variation revealed that the BRCA pathogenic variants in modern human population were mostly arisen after moving out of Africa.65 Therefore, it would be expected that the BRCA variants in non-African population be very different from these in African population. This is indeed the case. We compared the BRCA pathogenic variants between Asian58 and African populations.66 The results showed that only 41 (21 in BRCA1 and 20 in BRCA2) were shared between the 1,762 BRCA pathogenic variants in Asian population and 173 BRCA pathogenic variants in African population. None of the African BRCA founder variants of BRCA1 c.303T>G, c.1623dupG, c.4122_4123delTG and c.5324T>G were present in Asian population,67 and 44 of the 45 Asian founder variants (31 in BRCA1, 14 in BRCA2) were not present in African population except BRCA2 c.2808_2811del common in Asian population.65

As in most ethnic populations globally, breast cancer is also the most common cancer in Bahamas population with rich African genetic origin. However, there is a distinct feature for the breast cancer in Bahamas women that the carrier rate of BRCA pathogenic variants in Bahamas patients is much higher than in other ethnic populations that up to 23% of the Bahamas breast cancer patients carried BRCA pathogenic variants, mostly in BRCA1,68,69 likely caused by bottleneck effect. We searched the 9 BRCA1 and 3 BRCA2 pathogenic variants identified in Bahamas breast cancer patients in the BRCA pathogenic variants identified in African population,65 and identified c.4611_4612insG, c.4986+6T>C and c.5324T>G sharing between the 2 populations, highlighting the African origin of these BRCA pathogenic variants in Bahamas populations.

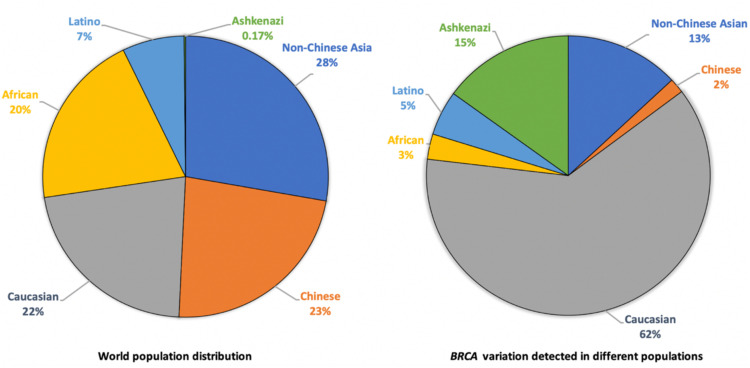

5. Ethnic origins of current BRCA variation data

We analyzed the ethnic origins of BRCA variation data in major BRCA variant databases, including the Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC), BRCA Exchange (BED), BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation (BMD), ClinVar, ENIGMA (Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles), and Leiden Open Variation (LOVD).45 The results showed that 62% of the BRCA variant data in these databases were originated from European descendant populations that constitute 23% of world population, 15% were from Ashkenazi Jewish population that constitutes 0.2% of world population, and the remaining were from non-Chinese Asian (13%), Latino (5%), African (3%), and Chinese (2%) that constitute 77% of world population (Fig. 3). We further analyzed the BRCA variation data collected by CIMBA (Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2) study, which reported the BRCA variant data derived from 49 countries across 6 continents.42 Of the 5,925 BRCA variants with defined ethnicities, 80.2% were from European descendant populations, 2.4% were from Ashkenazi Jews, and the remaining 18% were from other ethnic populations of Asian (10.8%), Hispanic (3.8%), and African American (2.8%). BRCA Exchange database collected 68,825 BRCA variants (https://brcaexchange.org/factsheet, accessed on August 30, 2022), and ClinVar database collected 25,775 annotated human BRCA variants (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/, accessed September 1, 2022). While ethnic information in both databases is not provided for most of their BRCA variation data, it is expected that the ethnic sources for the BRCA variants in these two databases would be the same as in other BRCA databases.

Fig. 3.

Origins of current BRCA variation data. The BRCA variants were collected from multiple BRCA variant databases including the Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC), BRCA Exchange (BED), BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation (BMD), ClinVar, ENIGMA (Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles), and Leiden Open Variation (LOVD). Analyzing the ethnic origins of the variant data showed that 62% were originated from European descendant populations, 15% were from Ashkenazi Jewish population, 13% from non-Chinese Asian population, 5% from Latino population, 3% from African population, and 2% from Chinese population.

Therefore, the 80/20 rule can be used to descript the current human BRCA variation data: 80% of current BRCA variant data were derived from the European descendant populations constituting 20% of world population, whereas 20% of current BRCA variant data were derived from other populations constituting 80% of world population.70,71 For example, only a few hundreds of BRCA variants have been identified in the African population of 1.4 billion.42 In many developing countries around world, BRCA variation have never been reported, e.g., not BRCA variants data have been reported in eight Asia countries.58 BRCA variation data provides an actual example in showing how the human genetic studies is heavily biased to European descendant populations.72 Lack of the ethnic BRCA variation data and open-accessing current BRCA variation databases promote the wide adaption of the European descendant populations-derived BRCA variation data as the BRCA standard references for global human populations. This practice has no scientific basis as it would assume that human BRCA variation be uniformly conserved across ethnic human populations, which is certainly not the case. The current situation of BRCA data origins reflects largely the scientific and economic advantage but not biological differences between European descendant populations and non-European populations.

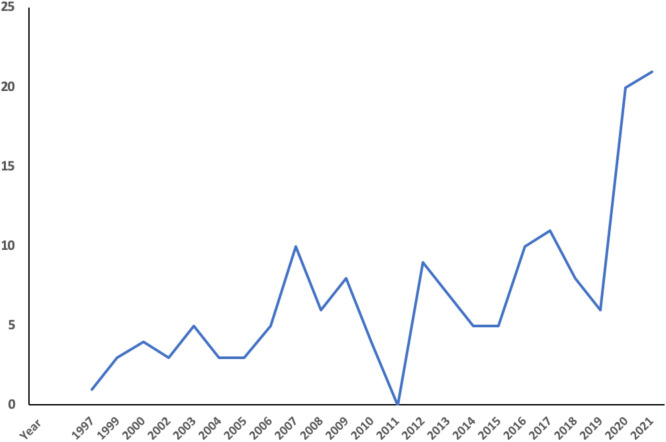

6. Status of BRCA variation study in Chinese population

With its population size of 1.4 billion and annual new breast cancer cases of a quarter million,73 knowledge of BRCA variation in the Chinese population is important. The first Chinese BRCA study was reported in Taiwanese Chinese endometrial carcinoma patients in 1997,74 in Hong Kong Chinese breast cancer patients in 1999,75 in mainland Chinese breast cancer patients in 2000,76 and in Macau Chinese general population in 2021.77 BRCA studies were progress at low profile but increased in recent years due largely to the NGS application. By May 2022, there have been at least 158 publications reporting BRCA variation in Chinese cancer patients (Fig. 4). Several academic laboratories have been actively engaged in BRCA variation study in Chinese cancer patients. For example, Xie Yuntao's group in Peking University Cancer Hospital tested BRCA variation in 8,627 breast cancer patients in northern Chinese;78 and Shao Zimin's group in Shanghai Jiaotong University Cancer Hospital tested thousands of breast cancer patients in Shanghai region.79 Promoted by the clinical value of PARP inhibitors in cancer treatment, commercial BRCA testing industry has been under rapid development in recent years, with hundreds of companies/hospital laboratories offering BRCA test services. However, nearly all services rely on the international BRCA reference databases as the references for their data interpretation. The “Genetic Resources Protection Law” recently established prohibits foreigners and researchers in Macau, Hong Kong and Taiwan to perform unauthorised human genetic study in Chinese population, which certainly includes BRCA study. Currently, there is no open BRCA reference database in China including mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan except a series of cancer gene variation databases in Asian population established in Macau by my laboratory such as the dbBRCA-Chinese (https://genemutation.fhs.um.edu.mo/dbbrca-chinese/, and dbBRCA-Asian (https://genemutation.fhs.um.edu.mo/dbbrca-asian/).

Fig. 4.

Published BRCA study in Chinese population. It shows that BRCA studies were progressed at low profile but increased in recent years due to the increased use of next generation DNA sequencing technologies.

We performed systematic characterization to know BRCA variation in general Chinese population and cancer cohorts by using various means of de novo sequencing, literature survey, and database mining.45,76,80, 81, 82, 83, 84 As of October 2022, we have identified a total of 3,379 BRCA variants (1,469 in BRCA1 and 1,910 in BRCA2), including 1,237 pathogenic variants (628 in BRCA1 and 609 in BRCA2), in Chinese population in mainland, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau.58

To estimate the prevalence of pathogenic BRCA variation in general Chinese population, we tested over 11,000 Chinese Han individuals.33 From the 1,209 BRCA variants detected (452 in BRCA1 and 757 in BRCA2), we identified 34 pathogenic with 43 carriers. Based on the data, we estimated the prevalence of 0.38%, or one in every 265 Chinese individuals, carrying pathogenic BRCA variants, and there could be over 5 million BRCA pathogenic variant carriers among the 1.4 billion Chinese.

European descendant population and Chinese population have similar population size. Referring to the BRCA variant data in BRCA Exchange database that hosts mostly the data derived from European descendant populations, the 3,379 BRCA variants from the Chinese population is equivalent to 4.9% of the 68,825 BRCA variants in BRCA Exchange database. This implies that over 65,446, or 19.3 times more, BRCA variants need to be collected from Chinese population to reach the current level of BRCA variant collection in the European descendant populations. Therefore, BRCA variant identification in Chinese population is still at enfant stage. Substantial efforts need to be made and resources need to be allocated to reach comprehensive coverage of BRCA variation in the Chinese population.

6.1. A case study: BRCA variation in Macau population

Macau is a special administration region of China, with its unique genetic, linguistic, and cultural features. It has a population around 650,000 (2020), 95% are Chinese ethnicity predominantly the Cantonese, and breast cancer is the number one cancer type in Macau female (25%). Using Macau population as a model, we tried to gain first-hand information for BRCA variation in southern Chinese population. We tested 6,314 Macanese Chinese individuals, equivalent to 1% of Macau population.77 We identified 659 BRCA variants (264 in BRCA1 and 395 in BRCA2), including 14 (2.1%) pathogenic variants with 18 carriers, of which 13 were in BRCA2 with 17 carriers but only 1 in BRCA1 with a single carrier, and 148 (22.5%) VUS (Table 1). All pathogenic variant carriers were heterozygotes. A founder mutation c.3109C>T in Southern Chinese85 was identified with 5 carriers, 6 of the 13 pathogenic variants were located in exon 11 of BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are considered as “coldspot” for BRCA pathogenic variants.86 Only two of the 14 Macau pathogenic variants (c.5164_5165delAG, c.9070_9073delAACA) were shared with these in mainland Chinese.33 Based on the presence of 18 pathogenic variant carriers in 6,314 individuals, we estimated the prevalence of 0.29%, or one carrier in every 345 Macauese Chinese individuals. We further estimated the presence of 1,853 BRCA pathogenic variant carriers of 132 in BRCA1 and 1,720 in BRCA2 in the Macau population of 650,000. Power calculation indicated that screening a population size of 6,314 individuals at prevalence of 0.29% should provide a 98.8% of probability to detect all pathogenic variants in this population, ensuring the accuracy of BRCA variation information in Macau population from the study.

Table 1.

Clinical classification of BRCA variants identified in Macau Chinese population.

| BRCA1 (%) | BRCA2 (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic | 1 (0.4) | 9 (2.3) | 10 (1.5) |

| Likely pathogenic | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 4 (0.6) |

| VUS | 53 (20.1) | 95 (24.1) | 148 (22.5) |

| Benign | 48 (18.2) | 64 (16.2) | 112 (17) |

| Likely benign | 51 (19.3) | 74 (18.7) | 125 (20.9) |

| Conflicting interpretations | 33 (12.5) | 45 (11.4) | 78 (11.8) |

| Unclassified | 78 (29.5) | 104 (26.3) | 182 (27.6) |

| Total | 264 | 395 | 659 |

7. Challenge of developing ethnic-based BRCA variation references

The majority of human BRCA variants identified so far remain functionally unknown. For example, of the 68,825 BRCA variants in BRCA exchange database, 89.2% have not been annotated (https://brcaexchange.org/factsheet, accessed December 10, 2022); of the 25,775 BRCA variants annotated in ClinVar database, 37% variants in BRCA1 (509 conflicting interpretations, 3,401 VUS) and 46% variants in BRCA2 (944 conflicting interpretations, 6,182 VUS) remain to be further classified (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/, accessed September 1, 2022); of the 1,209 BRCA variants identified in general Chinese population by our study, 64.3% (299 VUS, 100 conflicting interpretation, 378 unclassified) remain to be classified.33

The options for determining the pathogenicity of unknown genetic variants include experiment-based functional assays, statistics, protein structure, and evolution conservation-based in silico algorithms, and clinical evidence etc. The high-cost and low throughput nature of experiment-based approaches prohibits their widely application to classify the vast quantity of unknown variants;87 the evolution conservation-based in silico methods can't be used to annotate human BRCA variants as human BRCA variation was not originated from cross-species conservation.29 It is more challenge to classify the unknown BRCA variants identified in the non-European descendent populations due to the lack of the reference information, resources, and expertise.

We considered if an unknown variant can cause BRCA structural change, it would be a strong indication for its deleteriousness for BRCA function. We applied Molecular Dynamic simulations (MD simulations) to classify unknown coding-change missense BRCA variants. MD simulations uses a group of programs to measure the trajectories of atoms to determine macroscopic thermodynamics properties of the targeted molecular structure.88, 89, 90,89,90 We used MD simulations to examine the impact of missense variants on BRCA structure, and provided deleterious evidence for 102 of 177 (57.6%) unknown missense variants in BRCA1 BRCT domain and BRCA2 BRC4 domain.83,84 The computational nature of MD simulations allows large-scale characterization of missense variants in BRCA domain with known structure.

8. Conclusions

As the current BRCA variation data are mostly derived from European descendant populations, solely relying on the existing BRCA variant information is not capable of reflecting BRCA variation in global populations and providing precise application instruction. An ideal BRCA reference system needs to consist of two components. One is the current BRCA variation data in reflecting the BRCA variation and current achievement in decoding BRCA variation commonly in human populations, the other is the ethnic population derived BRCA variation data in providing the BRCA variation information in given ethnic populations. The later will be particularly meaningful for the ethnic populations with larger size such as the Chinese population. The combinational usage of the two components should provide an unbiased view of human BRCA variation and comprehensive reference for clinical applications in the era of precising medicine.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

Author's work has been supported by the high-performance computing cluster by Information and Communication Technology Office of the University of Macau and funded by grants from Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (grant numbers: 085/2017/A2, 0077/2019/AMJ, 0032/2022/A1), the University of Macau (grant numbers: SRG2017–00097-FHS, MYRG2019–00018-FHS, MYRG2020–00094-FHS), and the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau (Startup fund ,FHSIG/SW/0007/2020P, FHS Innovation grant, and MoE Frontiers Science Center for Precision Oncology Pilot Grants).

References

- 1.Roy R., Chun J., Powell S.N. BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;12(1):68–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huttley G.A., Easteal S., Southey M.C., et al. Adaptive evolution of the tumour suppressor BRCA1 in humans and chimpanzees. Australian breast cancer family study. Nat Genet. 2000;25(4):410–413. doi: 10.1038/78092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turnbull C., Sud A., Houlston R.S. Cancer genetics, precision prevention and a call to action. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1212–1218. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0202-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuchenbaecker K.B., Hopper J.L., Barnes D.R., et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2402–2416. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniou A., Pharoah P.D., Narod S., et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(5):1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S., Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/jco.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miki Y., Swensen J., Shattuck-Eidens D., et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wooster R., Neuhausen S.L., Mangion J., et al. Localization of a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2, to chromosome 13q12-13. Science. 1994;265(5181):2088–2090. doi: 10.1126/science.8091231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stratton M.R., Rahman N. The emerging landscape of breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40(1):17–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni A., Carley H. Advances in the recognition and management of hereditary cancer. Br Med Bull. 2016;120(1):123–138. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldw046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke W., Daly M., Garber J., et al. Recommendations for follow-up care of individuals with an inherited predisposition to cancer. II. BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer genetics studies consortium. JAMA. 1997;277(12):997–1003. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540360065034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pujade-Lauraine E., Ledermann J.A., Selle F., et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauff N.D., Domchek S.M., Friebel T.M., et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy for the prevention of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast and gynecologic cancer: a multicenter, prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1331–1337. doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.13.9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King M.C., Levy-Lahad E., Lahad A. Population-based screening for BRCA1 and BRCA2:2014 Lasker Award. JAMA. 2014;312(11):1091–1092. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown J.S., O'Carrigan B., Jackson S.P., et al. Targeting DNA Repair in Cancer: beyond PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(1):20–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-16-0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong P.C., Boss D.S., Yap T.A., et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narod S.A., Foulkes W.D. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(9):665–676. doi: 10.1038/nrc1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kojic M., Kostrub C.F., Buchman A.R., et al. BRCA2 homolog required for proficiency in DNA repair, recombination, and genome stability in Ustilago maydis. Mol Cell. 2002;10(3):683–691. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeffer C.M., Ho B.N., Singh A.T.K. The evolution, functions and applications of the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2017;14(5):293–298. doi: 10.21873/cgp.20040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming M.A., Potter J.D., Ramirez C.J., et al. Understanding missense mutations in the BRCA1 gene: an evolutionary approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(3):1151–1156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237285100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abkevich V., Zharkikh A., Deffenbaugh A.M., et al. Analysis of missense variation in human BRCA1 in the context of interspecific sequence variation. J Med Genet. 2004;41(7):492–507. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.015867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pavlicek A., Noskov V.N., Kouprina N., et al. Evolution of the tumor suppressor BRCA1 locus in primates: implications for cancer predisposition. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(22):2737–2751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burk-Herrick A., Scally M., Amrine-Madsen H., et al. Natural selection and mammalian BRCA1 sequences: elucidating functionally important sites relevant to breast cancer susceptibility in humans. Mamm Genome. 2006;17(3):257–270. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connell M.J. Selection and the cell cycle: positive Darwinian selection in a well-known DNA damage response pathway. J Mol Evol. 2010;71(5–6):444–457. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9399-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lou D.I., McBee R.M., Le U.Q., et al. Rapid evolution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in humans and other primates. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Q., Lei J.H., Bao J., et al. BRCA1 deficiency impairs mitophagy and promotes inflammasome activation and mammary tumor metastasis. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020;7(6) doi: 10.1002/advs.201903616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosen E.M., Fan S., Ma Y. BRCA1 regulation of transcription. Cancer Lett. 2006;236(2):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pao G.M., Zhu Q., Perez-Garcia C.G., et al. Role of BRCA1 in brain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(13):E1240–E1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400783111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith K.R., Hanson H.A., Hollingshaus M.S. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and female fertility. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25(3):207–213. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835f1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J., Zhao B., Huang T., et al. Human BRCA pathogenic variants were originated during recent human history. Life Sci Alliance. 2022;5(5) doi: 10.26508/lsa.202101263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Momozawa Y., Iwasaki Y., Parsons M.T., et al. Germline pathogenic variants of 11 breast cancer genes in 7,051 Japanese patients and 11,241 controls. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4083. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06581-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernández-Lopez J.C., Romero-Córdoba S., Rebollar-Vega R., et al. Population and breast cancer patients' analysis reveals the diversity of genomic variation of the BRCA genes in the Mexican population. Hum Genomics. 2019;13(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40246-018-0188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong H., Chandratre K., Qin Y., et al. Prevalence of BRCA1/BRCA2 pathogenic variation in Chinese Han population. J Med Genet. 2021;58(8):565–569. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-106970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wen W.X., Allen J., Lai K.N., et al. Inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in an unselected multiethnic cohort of Asian patients with breast cancer and healthy controls from Malaysia. J Med Genet. 2018;55(2):97–103. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manickam K., Buchanan A.H., Schwartz M.L.B., et al. Exome sequencing-based screening for BRCA1/2 expected pathogenic variants among adult biobank participants. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gabai-Kapara E., Lahad A., Kaufman B., et al. Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(39):14205–14210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415979111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernández J.E., Llacuachaqui M., Palacio G.V., et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in unselected breast cancer patients from medellín, Colombia. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2014;12(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramus S.J., Gayther S.A. The contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol. 2009;3(2):138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J., Fackenthal J.D., Zheng Y., et al. Recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients of African ancestry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):889–894. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villarreal-Garza C., Weitzel J.N., Llacuachaqui M., et al. The prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among young Mexican women with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150(2):389–394. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rebbeck T.R., Friebel T.M., Friedman E., et al. Mutational spectrum in a worldwide study of 29,700 families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(5):593–620. doi: 10.1002/humu.23406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lilyquist J., Ruddy K.J., Vachon C.M., et al. Common genetic variation and breast cancer risk-past, present, and future. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(4):380–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-17-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friebel T.M., Andrulis I.L., Balmaña J., et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic sequence variants in women of African origin or ancestry. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(10):1781–1796. doi: 10.1002/humu.23804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhaskaran S.P., Chandratre K., Gupta H., et al. Germline variation in BRCA1/2 is highly ethnic-specific: evidence from over 30,000 Chinese hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(4):962–973. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ossa Gomez C.A., Achatz M.I., Hurtado M., et al. Germline pathogenic variant prevalence among latin American and US hispanic individuals undergoing testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: a cross-sectional study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2022;8 doi: 10.1200/go.22.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Struewing J.P., Hartge P., Wacholder S., et al. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(20):1401–1408. doi: 10.1056/nejm199705153362001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhaskaran S.P., Huang T., Rajendran B.K., et al. Ethnic-specific BRCA1/2 variation within Asia population: evidence from over 78 000 cancer and 40 000 non-cancer cases of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese populations. J Med Genet. 2021;58(11):752–759. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ko J.M., Ning L., Zhao X.K., et al. BRCA2 loss-of-function germline mutations are associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk in Chinese. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(4):1042–1051. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avanesyan A.A., Sokolenko A.P., Ivantsov A.O., et al. Gastric cancer in BRCA1 germline mutation carriers: results of endoscopic screening and molecular analysis of tumor tissues. Pathobiology. 2020;87(6):367–374. doi: 10.1159/000511323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim H., Kim J.Y., Park K.U. Clinical implications of BRCA mutations in advanced biliary tract cancer. Oncology. 2022 doi: 10.1159/000527525. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36257294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao L., Sun J., Hu L., et al. Ovarian cancer risk of Chinese women with BRCA1/2 germline pathogenic variants. J Hum Genet. 2022;67(11):639–642. doi: 10.1038/s10038-022-01065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kimura M., Maruyama T., Crow J.F. The mutation load in small populations. Genetics. 1963;48(10):1303–1312. doi: 10.1093/genetics/48.10.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lohmueller K.E. The distribution of deleterious genetic variation in human populations. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;29:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henn B.M., Botigué L.R., Bustamante C.D., et al. Estimating the mutation load in human genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16(6):333–343. doi: 10.1038/nrg3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qin Z., Huang T., Guo M., et al. Distinct landscapes of deleterious variants in DNA damage repair system in ethnic human populations. Life Sci Alliance. 2022;5(9) doi: 10.26508/lsa.202101319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhaskaran S.P., Huang T., Rajendran B.K., et al. Ethnic-specific BRCA1/2 variation within Asia population: evidence from over 78 000 cancer and 40 000 non-cancer cases of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese populations. J Med Genet. 2021;58(11):752–759. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qin Z., Li J., Tam B., et al. Ethnic-specificity, evolution origin and deleteriousness of Asian BRCA variation revealed by over 7,500 BRCA variants derived from Asian population. Int J Cancer. 2022 doi: 10.1002/ijc.34359. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36385461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inoue R., Fukutomi T., Ushijima T., et al. Linkage analysis of BRCA1 in Japanese breast cancer families. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85(12):1233–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1994.tb02935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue R., Fukutomi T., Ushijima T., et al. Germline mutation of BRCA1 in Japanese breast cancer families. Cancer Res. 1995;55(16):3521–3524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katagiri T., Emi M., Ito I., et al. Mutations in the BRCA1 gene in Japanese breast cancer patients. Hum Mutat. 1996;7(4):334–339. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1004(1996)7:4<334::aid−humu7>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujisawa F., Tamaki Y., Inoue T., et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Japanese patients with triple-negative breast cancer: a single institute retrospective study. Mol Clin Oncol. 2021;14(5):96. doi: 10.3892/mco.2021.2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arai M. In: Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer: Molecular Mechanism and Clinical Practice. Nakamura S, Aoki D, Miki Y, editors. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2021. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) database in Japan; pp. 243–257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayashi S., Kubo M., Kaneshiro K., et al. Genetic medicine is accelerating in Japan. Breast Cancer. 2022;29(4):659–665. doi: 10.1007/s12282-022-01342-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J., Zhao B., Huang T., et al. Human BRCA pathogenic variants were originated during recent human history. Life Sci Alliance. 2022;5(5) doi: 10.26508/lsa.202101263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Friebel T.M., Andrulis I.L., Balmaña J., et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic sequence variants in women of African origin or ancestry. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(10):1781–1796. doi: 10.1002/humu.23804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang J., Fackenthal J.D., Zheng Y., et al. Recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients of African ancestry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):889–894. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Donenberg T., Lunn J., Curling D., et al. A high prevalence of BRCA1 mutations among breast cancer patients from the Bahamas. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(2):591–596. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.George S.H.L., Donenberg T., Alexis C., et al. Gene sequencing for pathogenic variants among adults with breast and ovarian cancer in the Caribbean. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D862–D868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cline M.S., Liao R.G., Parsons M.T., et al. BRCA challenge: BRCA exchange as a global resource for variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sirugo G., Williams S.M., Tishkoff S.A. The missing diversity in human genetic studies. Cell. 2019;177(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P.D., et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu F.S., Ho E.S., Shih R.T., et al. Mutational analysis of the BRCA1 tumor suppressor gene in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66(3):449–453. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tang N.L., Pang C.P., Yeo W., et al. Prevalence of mutations in the BRCA1 gene among Chinese patients with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(10):882–885. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.10.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ding X., Lang J. BRCA1 gene mutations in early-onset breast cancer. Natl Med J China. 2000;80(2):111–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Qin Z., Kuok C.N., Dong H., et al. Can population BRCA screening be applied in non-Ashkenazi Jewish populations? Experience in Macau population. J Med Genet. 2021;58(9):587–591. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zang F., Ding X., Chen J., et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants in 8627 unselected patients with breast cancer: stratification of age at diagnosis, family history and molecular subtype. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;195(3):431–439. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Song C.G., Hu Z., Yuan W.T., et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations of familial breast cancer from Shanghai in China. Chin J Med Genet. 2006;23(1):27–31. doi: 10.3760/j.issn:1003-9406.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim Y.C., Zhao L., Zhang H., et al. Prevalence and spectrum of BRCA germline variants in mainland Chinese familial breast and ovarian cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(8):9600–9612. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Downs B., Sherman S., Cui J., et al. Common genetic variants contribute to incomplete penetrance: evidence from cancer-free BRCA1 mutation carriers. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chian J., Sinha S., Qin Z., et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 variation in Taiwanese general population and the cancer cohort. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.685174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sinha S., Wang S.M. Classification of VUS and unclassified variants in BRCA1 BRCT repeats by molecular dynamics simulation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:723–736. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sinha S., Qin Z., Tam B., et al. Identification of deleterious variants of uncertain significance in BRCA2 BRC4 repeat through molecular dynamics simulations. Brief Funct Genomics. 2022;21(3):202–215. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elac003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwong A., Ng E.K., Wong C.L., et al. Identification of BRCA1/2 founder mutations in Southern Chinese breast cancer patients using gene sequencing and high resolution DNA melting analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e43994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dines J.N., Shirts B.H., Slavin T.P., et al. Systematic misclassification of missense variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 "coldspots". Genet Med. 2020;22(5):825–830. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0740-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomassen M., Mesman R.L.S., Hansen T.V.O., et al. Clinical, splicing and functional analysis to classify BRCA2 exon 3 variants: application of a points-based ACMG/AMP approach. Hum Mutat. 2022 doi: 10.1002/humu.24449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu X., Tian W., Cheng J., et al. Microsecond molecular dynamics simulations reveal the allosteric regulatory mechanism of p53 R249S mutation in p53-associated liver cancer. Comput Biol Chem. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.107194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salsbury F.R., Jr. Molecular dynamics simulations of protein dynamics and their relevance to drug discovery. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(6):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pantelopulos G.A., Mukherjee S., Voelz V.A. Microsecond simulations of mdm2 and its complex with p53 yield insight into force field accuracy and conformational dynamics. Proteins. 2015;83(9):1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/prot.24852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]