ABSTRACT

Pathogenicity islands are members of a vast collection of genomic islands that encode important virulence, antibiotic resistance and other accessory functions and have a critical role in bacterial gene transfer. Staphylococcus aureus is host to a large family of such islands, known as SaPIs, which encode super antigen and other virulence determinants, are mobilized by helper phages and transferred at extremely high frequencies. They benefit their host cells by interfering with phage predation and enhancing horizontal gene transfer. This chapter describes their life cycle, the bases of their phage interference mechanisms, their transfer system and their conversion to antibacterial agents for treatment ofstaphylococcal infections.

INTRODUCTION

Once upon a time, bacteria, like other organisms, were considered to have stable genomes with essentially constant overall composition that unequivocally defined each species. The bacterial genome was initially seen to consist of a single very large circular DNA molecule (chromosome) containing all of the organism’s genes (1). In retrospect, the proof that prophages were physically integrated into the chromosomal DNA provided the first inkling that this view was incorrect: discrete, variable, and mobile genetic units could exist within the bacterial chromosome. The profundity of this observation, however, was not immediately realized, since phages were seen as parasitic invaders that had found integration as a way to achieve stable intracellular inheritance. It was soon realized, however, that not only temperate phages but also the F plasmid and, as it was then thought, the ColE1 plasmid could reversibly integrate into the host cell’s chromosome and that there were also short DNA segments (insertion sequences) that could be found in various locations (2). These observations led to the idea of discrete elements of genomic variability superimposed on the overall constancy of the chromosomal genophore; indeed, by 1996 the intergeneric transfer of mobile genetic elements had been documented so widely that David Summers was led to suggest, a bit whimsically, that all bacteria are but a single megaspecies, cohered by a vast marketplace of exchangeable genetic units (3).

Within this overarching firmament of genetic mobility are the genomic islands (GIs)—elements that were first realized to be members of this universe when several reports described DNA segments that carried genes involved in pathogenicity, lacked genes belonging to the core chromosome, and were present in some strains of a species but absent from others (4). Termed “pathogenicity islands,” they launched the concept of the GI, which is now the generic term for all inserted DNA segments in bacteria (5). However, despite the clarity of this concept, it has often been misapplied and therefore deserves a very clear and exclusive definition: “a genomic island (GI) is a discrete segment of DNA with defined ends, that has a limited phylogenetic distribution” (6); because a GI lacks genes belonging to the core chromosome, it is dispensable. Membership in the island family involves acquisition by horizontal transfer; although extant islands may not be or may no longer be mobile, most possess stigmata of their horizontal acquisition, including flanking direct repeats, mobility genes such as int and xis, transfer origins, tra genes, replication-related genes, and transposition genes. It is generally possible to distinguish a GI from an indel by these criteria. Included in the island family are insertion elements and other transposons, integrating conjugative elements, pathogenicity islands, resistance islands, symbiosis islands, integrating plasmids, and prophages (see Table 1). With the exception of symbiosis islands, all of these occur in staphylococci, where they have a major role in the biology of the organism.

TABLE 1.

GIs in staphylococcia

| Island | Size (kb) | Accessory genes | GI stigmata |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insertion sequences | 1–2 | None | Flanking DRs, transposase |

| Transposons | >5 | Ab resistance genes | Flanking DRs, transposase |

| SCC elements | 20–60 | mecA, other Ab resistances | Flanking DRs, ccr genes |

| Prophages | 40–50 | Toxin and other converting genes | Flanking DRs, int/xis, replicon, virion genes, autonomous replication, mobility, etc. |

| SaPIs | 12–27 | Sag genes, other virulence and resistance genes | Flanking DRs, int/xis, replicon, terS, autonomous replication, mobility |

| Integrated plasmids | 4–40 | Ab and heavy metal resistance | Typical plasmid genes, replicon |

| Conjugative transposons | 15–50 | Ab resistance | Flanking DRs, tra genes, oriTs, int/xis, mobility |

| ICE elements | 15–50 | Ab resistance | Flanking DRs, tra genes, oriTs int/xis, mobility |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibiotic (not antibody); DR, direct repeats; ccr, cassette chromosome recombinae; Sag, superantigen; SCC, staphylococcal cassette chromosome; tra, transfer; oriT, transfer origin; ICE, integrative and conjugtive element.

This article focuses on a critically important group of staphylococcal GIs, the Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs). They are a coherent family of phage-inducible, highly mobile GIs of 12 to 18 kb that are widely distributed among S. aureus strains. Although the SaPIs have a modular organization, reminiscent of prophages, and encode several prophage-like functions, they are not defective phages but distinct genetic elements with a characteristic life cycle, novel functions, and unique cargo. They play a significant role in the pathogenesis, evolution, and biology of the organism.

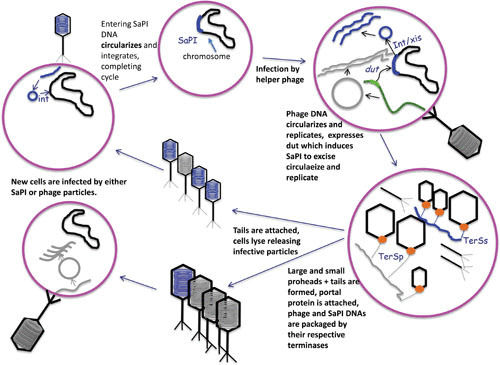

SaPI Encapsulated

Like prophages, the SaPIs reside quiescently in the S. aureus chromosome under the control of a SaPI-coded master repressor (Stl) and replicate along with the chromosomal DNA. However, unlike most prophage repressors, the SaPI repressors are not SOS-inducible but are derepressed by specific (helper) phage-coded proteins. When helper phages infect the cell or undergo induction as prophages, they produce antirepressors that counteract Stl, initiating expression of the overall SaPI genome, which leads to excision and replication. Postreplicative SaPI DNA is packaged in phage-like particles composed of phage virion proteins, which are released by helper phage-induced cellular lysis. SaPI particle titers are commensurate with helper phage titers, resulting in extremely high transfer frequencies. The SaPIs frequently carry and disseminate staphylococcal signature toxin genes and therefore play an important role in pathogenesis. Like pac phages, most SaPIs are capable of mediating generalized transduction (GT) and therefore play a role in the adaptability and evolution of the organism. However, the SaPI’s actual raison d’etre may, ironically, be to protect the staph cell from its most formidable foe, the bacteriophage. Although the SaPIs are derived from and dependent on phages, all SaPIs code multiple mechanisms for interfering with phage reproduction.

A Brief History of SaPIs

Some 20 years ago, the Novick lab cloned tst, the gene for toxic shock toxin-1 (TSST-1) and confirmed that it was a variable gene, present in only about 10% of clinical S. aureus isolates. Strains lacking the gene were also missing about 14 kb of flanking sequences, and when the gene was transferred by GT to a new strain, using an inserted tetracycline resistance gene to enable genetic selection, the flanking 14 kb were also transferred, and the transfer occurred at an extremely high frequency. Examination of different TSS strains revealed that the gene was in more than one location, suggesting that the 15-kb unit was a transposon. Analysis of a tst element in a different location revealed that the flanking sequences were different, ruling out a transposon and prompting us to consider it a pathogenicity island (7). We named the first one SaPI1 and the second, SaPI2. Though it was assumed that pathogenicity islands were mobile, this was the first demonstration. Several others were soon characterized, including one from a bovine isolate (SaPIbov1) (8). Later, when large numbers of S. aureus genome sequences became available, we observed that SaPIs made up a huge family, with an average of one per strain, with those having two, three, or more balanced by those with none. At least two major families were discerned, of which the prototypes are SaPI1 (7) and SaPIbov5 (9) (Fig. 1). Five SaPI attachment (att) sites were identified in S. aureus, in which only SaPIs but no other mobile genetic elements were located, nor were SaPIs found at any other location. These sites are utilized by members of both SaPI subsets.

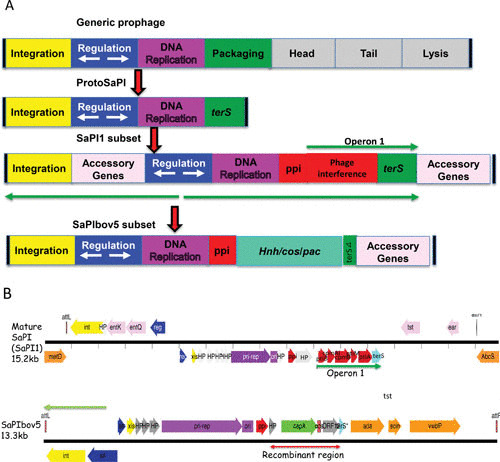

FIGURE 1.

The SaPI genome and its putative origin. (A) Block diagrams. At the top is a typical prophage genome, and below that is the putative SaPI precursor, presumably the result of a major deletion. Next are two extant SaPI genomes. (B) Genetic maps of SaPI1 and SaPIbov5. Colors: red, interference genes; aqua, terS; orange, accessory genes; blue, regulatory genes; yellow, int/xis; gray, hypotheticals; purple, replication.

SaPI-like elements are also found in non-aureus staphylococci, but much less frequently. Although the SaPIs were initially designated pathogenicity islands and are the only known source of TSST-1 (7), many of them do not carry identifiable virulence genes, so the “SaPI” designation is something of a historical accident. Although the term “SaPI” is too well established to consider modifying it, similar elements, with which other Gram-positive cocci are replete and which have yet to be found carrying virulence genes, are called phage-inducible chromosomal islands (PICIs) (10, 11).

The SaPI Genome

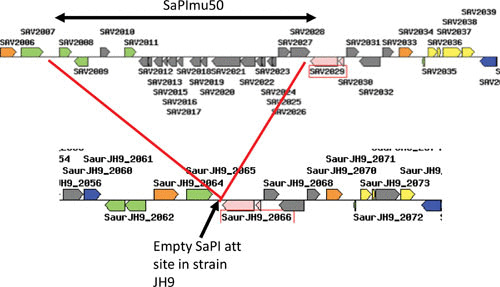

The SaPIs and their relatives in other Gram-positive bacteria were, almost certainly, derived from a bacteriophage or protophage in the very distant past by a deletion eliminating the phage morphogenesis and lysis modules, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The resulting SaPI genome contains three types of genes: life-cycle genes, interference genes, and accessory genes. It has, however, retained its prophage-like modular organization in which the life cycle genes are organized as follows: there is an integrase gene (int) at one end followed by a key site of transcriptional divergence flanked by two key regulatory genes, a c1-like master repressor (stl) and a cro-like activator (str) (see reference 12 for a review). In some SaPIs, the region between int and stl contains accessory genes. The integrase is always accompanied by an xis function; a pri-rep/ori complex defines the SaPI replicon, which is organized similarly to typical prophage replicons in which the replication origin (ori) is directly downstream of the replication initiator (rep) gene; upstream of rep is a primase homolog (pri), which is fused to rep in some SaPIs; the ori consists of two sets of GC-rich short repeats flanking an ∼80-bp AT-rich region. Downstream of the replicon is a prophage packaging inhibitor (ppi), one of the phage interference genes (see below). Although a detailed transcription map is not available, three main transcripts have been defined (the green arrows in Fig. 1). The SaPI genome can be readily identified by genome scanning; for example, a typical SaPI at the groEL (SAV2029) site in mu50, from genes SAV2008(sec3) to SAV2028(int) is shown in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

SaPI genomic pattern. At the top is the groEL region of S. aureus strain mu50, with a classical SaPI inserted at the 3′ end of groEL. The basic SaPI genes are in gray, and accessory genes at the left end are in green. Note the typical transcriptional divergence. Below is shown the corresponding region of strain JH9, in which the SaPI att site at groEL is empty.

The SaPI1 Subset

In this group of SaPIs, ppi is followed by operon 1, which contains several other phage interference genes and ends at terS (Fig. 1). The TerS (terminase small subunit) is highly conserved among these SaPIs and is specific for the packaging of SaPI DNA; unlike in prophages, the pac site is separated from the terS gene, which enables transcomplementation of terS mutants and is a crossover suppressor of heterologous recombination in that region. Unlike the typical prophage pac sites, which are embedded within the terS coding sequence (13), the SaPI pac site is typically separate from and upstream of the SaPI terSS coding sequence (14). Beyond terS is a region occupied by accessory genes.

The SaPIbov5 Subset

Many S. aureus strains of domestic animals harbor variant SaPIs of which the prototype is SaPIbov5 (9, 15). These lack a functional terS but have a C-terminal remnant of a typical SaPI terS gene. They were probably derived from a typical SaPI by recombination with a cos phage. This recombination event replaced most of operon 1 by a prophage DNA segment containing a cos site, an hnh protease gene, and ccm, a gene encoding a homolog of the phage major capsid protein. The terS remnant marks one end of the putative recombinational event. It is possible that this putative recombination event occurred several times, since SaPIs of this type are found in several SaPI att sites (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

| Strain | Size | Orientation | Location | int | tx | tx | tx | stl | str | xis | rep | ppi | pac | cpm | ptiA | ptiB | terS | ccm | HNH | cos | tx | tx | tx | tx | ada | scin | vwbP | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 - classical SaPIs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6850 (MSSA) | 16 | 3 to 5 | groEL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | bcinIII | HP | HP | HP | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RF122 (SaPIbov1) | 15.5 | 5 to 3 | guaA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | tst | bcnIIc | sec | sel | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bovine |

| RF122 (SapI122) | 16.5 | 3 to 5 | groEL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | mdr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bovine |

| BMB9393 | 14.8 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 55/2053 | 12.1 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TCH60 | 12.1 | 3 to 5 | metQ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SA957 (CA-MRSA) | 14.4 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | sek | seq | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | seb | ear | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| n315 (SaPIn1) | 15.2 | 3 to 5 | groEL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | tst | ear | sec | sel | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RN4282 (SaPI1 | 15.2 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | sek | seq | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | tst | ear | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RN3984 (SaPI2) | 15.3 | 3 to 5 | groEL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | tst | eta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| COL (SaPI3) | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | seb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| FDARGOS_5 | 3 to 5 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| MS4 | 15 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | seb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Z172 (MRSA/VISA) | 14.9 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | sek | sel | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TO131/00383 | 10.6 | 5 to 3 | rpsR | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TO131/00870 | 16.1 | 5 to 3 | rnr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | eta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TO131/00934 | 16.4 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TO131/02151 SaPI6D | 6 | 5 to 3 | groEL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TO131/02158 | 12.8 | 3 to 5 | groEL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Group 2 - ccm-cos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| JP5338 (SaPIbov5) | 13.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Bovine | ||

| BA4 (SaPIbov4) | 13.9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Bovine | ||

| UTSW MRSA55 | 11.1 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| JE2 | 12.3 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CZ406 | 12.3 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| M6 | 12 | 5 to 3 | guaA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ? | 1 | Cow? to pig | |

| NX-T55 | 9 | 3 to 5 | guaA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Animal defective? |

| USA300_TCH1516 | 12.9 | 5 to 3 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | ear | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 08BA02176 | 13 | 5 to 3 | guaA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| MW2 | 13.8 | 5 to 3 | rnr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | ear | sec | sel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ST398(MRSA) | 12.3 | 5 to 3 | guaA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Animal strain causing human endocarditis |

| ED133 | 14.1 | 5 to 3 | guaA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | tst | sec | sel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Ovine |

| ED133 | 10.1 | 3 to 5 | groEL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Ovine |

| AR0223 | 11.1 | 3 to 5 | metQ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3′rem | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Abbreviations: MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; CA-MRSA, community-acquired, MSSA; VISA, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus; vWBP, von Willebrand factor binding protein

1, the presence of a gene; 0, the absence of a gene.

THE SaPI LIFE CYCLE (Fig. 3)

FIGURE 3.

The SaPI life cycle.

Regulation

As noted above, SaPI DNA expression is controlled by a c1-like master repressor, Stl, which is countered by helper phage-encoded derepressor proteins, all of which have significant roles in the phage life cycle and are therefore moonlighting proteins (16, 17). The Stl amino acid sequence is highly variable, and different Stls are countered by different derepressors. Thus far, four derepressors have been analyzed in S. aureus and one in Enterococcus faecalis. Table 3 lists the SaPIs that encode these Stls and their respective phage-specified derepressors. Remarkably, 80α encodes four independent and unrelated SaPI derepressors, and there could easily be additional ones that are as yet unrecognized. It is also highly likely that 80α is not unique among temperate staphylococcal phages in its possession of multiple SaPI derepressors.

TABLE 3.

De-repressor proteins and their targets

| Phage | SaPI/PICI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SaPI1 | SaPI2 | SaPIbov1a | SaPIbov2 | SaPIbov5a | PICIef583 | |

| 80α | Sri | Sak | dUTPase3b | gp15 | dUTPase3 | |

| 80/52A | Sak4 | |||||

| ɸ11 | dUTPase3 | dUTPase3 | ||||

| ɸNM1 | dUTPase2 | dUTPase2 | ||||

| ɸSLT | Erf | |||||

| ɸn315 | Redβ | |||||

| ɸ1 | Xis | |||||

SaPIbov1 and SaPIbov5 have identical Stls.

Superscripts 2 and 3 indicate the dimeric and trimeric forms of dUTPase.

The fascinating question arises of how these remarkable relationships could have evolved. Perhaps the SaPIs were derived from a prophage induced by a trans-acting derepressor protein (18) (although in the known cases, the derepressors are SOS induced). Alternatively, the SaPI followed an evolutionary pathway in which a classical SOS-induced repressor evolved to one that is bound and inactivated by an important phage-coded protein. The Stls are remarkably diverse, and the evolutionary forces driving their diversity are far from obvious. Moreover, even those that interact with a given derepressor do not seem to have any common motif that could be identified as a binding target. The most interesting of the derepressor proteins is dUTPase, which is universally conserved among temperate phages and has a significant (but nonessential) role in the phage life cycle. dUTPase is a bifunctional protein whose enzymatic and derepressor activities are genetically separable but functionally linked, in that binding of dUTP causes an allosteric shift which enables the protein to bind the Stl (19). dUTPase occurs in dimeric and trimeric forms, and both have the same derepressor specificity. In other species, the repressor-binding region has an important role in signaling and in immune modulation (20). Among the other known derepressor proteins, Sri inhibits loading of DnaB helicase and thus blocks chromosomal replication (21); Sak is a single-strand DNA binding protein that functions in recombination (22); Xis is the classical excision protein, and gp15 is a small protein of unknown function.

The SaPI-Phage War

As detailed below, all known SaPIs and similar elements from other organisms devote considerable genetic energy to interfering with the reproduction of their helper phages. The biological rationale for this is probably that the SaPIs are engaged in supporting their host cells, and one of their most potent weapons is the blocking of phage predation while at the same time commandeering phage proteins for their own life cycle. This generates a phage versus SaPI war, against which the phage’s defense is for its derepressor to mutate. This idea is supported by a study demonstrating the frequent occurrence of SaPI-resistant mutations in the derepressor genes during passages of helper phages on SaPI-containing strains (23). Although this might seem to win the war for the phages, in actuality it does not. The derepressor proteins have important roles in the phage life cycle, and one of them, Sak, is evidently essential (22). The experimentally observed mutations are always detrimental to the phage and would not persist in the absence of continuous selection by the presence of a SaPI. Nevertheless, genome data suggest that many phages have actually won this war; the derepressor genes all have homologs in nonhelper phages, and these always differ considerably at the amino acid level from their derepressor cousins (23). If these proteins were once derepressors, this suggests that the development of SaPI resistance must have been a slow and arduous process. Not to be thus outdone, the SaPIs have “learned” to utilize related phage proteins as derepressors. A striking example is the utilization by SaPI2’s Stl of distantly related proteins in four different phages as derepressors (22). Remarkably, the SaPI2 Stl appears to have different domains that interact with the different derepressors (22), indicating that the SaPI2 Stl is structurally rather accommodating and not so easily defeated. While this capability does not enable the SaPI to utilize a phage whose derepressor has evolved away from SaPI sensitivity, it means that the range of phages that a given SaPI can utilize as helpers is immeasurably broad and extends trans-specifically and even trans-generically (22, 24).

Integration-Excision

SaPI integrases are of the tyrosine type, with att site cores of 15- to 22-bp direct repeats; the long flanking sequences generally required by tyrosine integrases have not been mapped. Early results suggested that following the entry of SaPI DNA, integration is delayed for more than an hour because the recombination event required for circularization is very slow (25). Integration is inhibited by 10- to 100-fold if the recipient’s att site is occupied by a resident SaPI; this inhibition is not caused by the resident SaPI’s repressor, but rather by the occupation of the att site (26), presumably because the hybrid att sites flanking the resident SaPI are poor substrates for the integrase. Nevertheless, integration eventually occurs at either of these hybrid att sites, generating a tandem double. The tandem double is highly unstable, randomly losing either integrant by excision. Since the excised SaPI cannot replicate, owing to the presence of the SaPI repressor protein, it is immediately lost (26). A SaPI entering a recipient lacking its normal att site integrates with remarkably high efficiency (perhaps as high as 10% of the frequency of its integration into its primary site) into a secondary att site, of which there are at least 25 for SaPI1 (24). These secondary att sites generally match the primary site rather poorly, indicating that the integrases have rather loose site specificity. A remarkable unsolved mystery is that a SaPI in a secondary site is not induced by SOS induction of a resident helper prophage, although it is induced normally following superinfection of a nonlysogen by the same helper phage (24).

Replication

Replication is initiated by the Rep (or pri-rep) protein, which is SaPI specific; specificity is determined by a short C-terminal region of the protein, as shown by an experiment in which this region was switched between SaPIs of different specificities (27). The Rep protein is a helicase which binds to the two sets of flanking repeats that define the ori, causing the intervening AT-rich region to form a loop. Superhelix-driven melting of this loop exposes single-stranded regions which serve as the sites for Rep-initiated bidirectional replication (27). Following initiation, the host DNA polymerization system, modified to accommodate phage replication, takes over, and replication is completed by this system, resulting in concatenated multimers, the substrate for packaging (27).

Capsid Morphogenesis and Packaging

Most SaPIs package their DNA in small capsids commensurate with their small genomes. The precedent for phage satellite capsid modification is the Escherichia coli P2-P4 system, in which P4 modifies the P2 capsid to fit its 12-kb genome (28). This is accomplished by a P4-encoded scaffold protein, Sid, which forms an external shell within which the P2 capsid proteins are assembled to form the small P4 capsids (29). Many SaPIs also direct the helper phage capsid proteins to form small capsids, commensurate with their 15-kb genomes. For members of the SaPI1 subset, SaPI capsid size is determined by SaPI-coded CpmA and CpmB proteins (5), which act rather differently than the P4 Sid protein. CpmA and CpmB are both required for efficient small-capsid production (5), with CpmB modifying the internal scaffold to switch the capsid from T = 7 to T = 4 icosahedral geometry and CpmA ensuring the efficiency of size determination (5). For members of the SaPIbov5 subset, the Ccm protein (a homolog of the major phage capsid protein) is responsible for capsid size determination. In this case, the resulting small capsids have a morphology entirely different from that of the helper phage (30). In either case, deletion of the capsid morphogenesis gene(s) results in packaging of SaPI DNA in full-size phage capsids (30, 31).

Following replication, for members of the SaPI1 subset, headful packaging of SaPI DNA is initiated by a SaPI-coded terminase small subunit (TerSS), which is distinct from the helper phage counterpart (TerSP) and recognizes the SaPI-specific pac site (16, 32). TerSS complexes with the phage TerL to direct the SaPI DNA into preformed capsids composed of phage virion proteins (5, 33, 34). Packaging specificity is determined by TerS recognition specificity and is independent of procapsid size (31). Upon phage-induced lysis, SaPI particles are released in large numbers to infect other cells. Deletion of terSP eliminates phage DNA packaging but does not affect lysis, so that lysates are produced with particles of both sizes containing only SaPI DNA (21). For members of the SaPIbov5 subset, packaging is initiated by the helper phage terminase and occurs by the headful mechanism if the helper phage is a pac phage or by the cos packaging mechanism if the helper phage is a cos phage.

SaPIs of the bov5 type also reside quiescently under the control of a master repressor, which is countered by helper phages. Because they lack a functional terS, they rely on helper phage terminases for packaging, and they use two independent packaging pathways. They can be packaged by a typical helper phage, ɸ11, using the ɸ11 terminase and by a ɸ11pac site (which has not been mapped). Alternatively, they can be packaged by ɸ12, which is not a helper phage for the SaPI1 family, using the ɸ12 terminase/HNH complex and a cos site derived from ɸ12 (or a related cos phage). The putative ɸ12 derepressor has yet to be identified.

Interference Mechanisms

Bacteria have developed a vast array of phage resistance mechanisms; indeed, phage-resistance mutations have been isolated affecting every stage of the phage life cycle. As noted above, a critical and highly evolved feature of SaPI biology is the presence of phage interference systems, which do not resemble known bacterial phage resistance mechanisms and utilize SaPI-specific genes, some of which have no counterparts among the phages or elsewhere. Among the well-characterized SaPIs of the SaPI1 subset, four such systems have been described (25, 35, 36) (see Table 4). The first of these to be identified (25, 35) is the capsid morphogenesis system, which catalyzes small capsid formation. Since SaPI DNA can be packaged equally well in capsids of either size, the selective value for the SaPI of small capsid formation must therefore be attributed to interference with helper phage reproduction, which amounts to over 90% in some cases (25). This system causes interference not only by diverting the phage virion proteins, but also by causing the phage to waste its DNA by packaging in small capsids, which can accommodate only one-third of the phage genome. The second interference mechanism discovered consists of a SaPI-encoded protein, Ppi, that binds to and inhibits the function of the phage small terminase (TerSP) but does not affect the SaPI counterpart (TerSS), sharply reducing the packaging of phage DNA (35). The third interference system involves a protein, PtiA, that blocks transcription of the late phage genes, including the virion protein and lysis modules, by binding to and inhibiting the late gene activator, LtrC (36). Unchecked, PtiA would block SaPI as well as phage particle production and would be suicidal for both; consequently, there is a second component of this inhibition system, PtiM, which binds to and moderates the inhibitory activity of PtiA (36). There is also a second ltrC-blocking protein, PtiB, which thus represents a fourth interference mechanism (36). Three of the phage interference systems are encoded in operon 1; the fourth, ppi, is not. Whether this is biologically significant or is an evolutionary “accident” is unclear. The multiplicity of unrelated interference systems, necessarily the products of convergent evolution, underlines their key role in SaPI biology. Since the interference systems are expressed only following SaPI induction, they were first identified as acting on helper phages; however, they also act with undiminished efficiency on other phages, so long as the SaPI is induced by some other agency.

TABLE 4.

Mechanisms of SaPI-mediated phage interference

| Action | Gene(s) | SaPI1 | SaPI2 | SaPIbov1 | SaPIbov2 | SaPIbov5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diverts phage virion proteins for the formation of small capsids | cpmAB | ++ | +++ | + | – | – |

| Blocks procapsid formation by binding to the phage capsid protein | ccm | – | – | – | – | +++ |

| Binds to and blocks function of phage TerS | ppi | – | +++ | ++ | +++ | ND |

| PtiA binds to LtrC and blocks activation of late phage gene transcription; modulated by PtiM | ptiAM | ++ | ++ | – | ND | Absent |

| Blocks activation of late phage gene transcription by an unknown mechanism | ptiB | ND | ++ | ND | ND | Absent |

+, Relative strength; –, inactive; ND, no data.

As far as is known, the PICIs of other Gram-positive bacteria also interfere with phage reproduction (11). For members of the SaPIbov5 subset, the primary interference mechanism involves Ccm, which interferes with prohead formation by interacting with the major capsid protein (30). Here, the interference mechanism is much more stringent than that seen with members of the SaPI1 subset, resulting in a 106- to 107-fold reduction in phage titer (30). Since the SaPI capsids also utilize the major phage capsid protein (30), this interference necessarily results in lower SaPI titers than those seen with the SaPI1 subset.

There is an interesting contrast between SaPI-mediated phage interference and the powerful clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) antiphage system: the SaPIs not only do not totally block phage reproduction, but they also use their interference systems to aid in their own transfer and that of unlinked bacterial genes, whereas the CRISPR system destroys the phage genome and thus precludes phage-mediated gene transfer. Perhaps the high frequency of SaPIs and the rarity of CRISPRs in S. aureus is related to the effects of both on gene transfer. This is especially noteworthy since phage- and SaPI-mediated gene transfer are by far the most import genetic exchange mechanisms in this species.

SaPI OPERON 1, A FEATURE OF THE SaPI1 SUBSET, AND ITS KEY ROLES IN HOST CELL BIOLOGY

Host Cell Protection by Operon 1

Virtually all naturally occurring S. aureus organisms are lysogenic, many carrying several prophages, most of which are SOS-inducible. Although SOS induction is a stress response which counters DNA damage (37), the presence of an SOS-inducible prophage defeats this because its induction is lethal for the cell. (One must imagine that the SOS response evolved before prophages came on the scene.) SaPIs, however, counter this lethality in a remarkable way through their unique possession of an SOS-inducible operon, operon 1. The discovery of operon 1 and its SOS induction, early in the study of the SaPIs (38), was highly puzzling. Why should this element, which was not itself SOS inducible but required a phage-coded antirepressor instead, contain an SOS-inducible operon? Part of the answer, as noted below, is that SOS induction of operon 1 promotes SaPI-mediated GT. A more important rationale is that operon 1 encodes three of the four known phage interference systems (see below). Thus, DNA damage, resulting in the SOS response, induces operon 1 and is thus predicted to counter the lethal SOS induction of resident prophages, rescuing the cell and enabling the stress response. Perhaps the presence of several different interference mechanisms could be related to differential phage sensitivities. It is perhaps highly relevant in this context that most prophages are not helpers for SaPIs that happen to be coresident; instead, the presence of a SaPI would protect the cell from lethal phage induction during the SOS response. The story is slightly different if an SOS-inducible prophage happens to be a helper for a coresident SaPI. In this case, both SaPI and phage are induced, and the interference dynamics are more complicated; although the induced SaPI interferes with phage reproduction by one or more mechanisms, it blocks phage reproduction only partially because it needs the phage packaging and lysis systems for the production of infectious SaPI particles.

SaPI-Mediated Gene Transfer

In addition to their own high-frequency transfer, SaPIs mediate GT based on TerSS-directed mis-packaging of genomic DNA (39), entirely analogous to phage-mediated GT. In both cases, TerSS and TerSP recognize pseudo-pac sites homologous to the respective SaPI and phage pac sites. Since TerSS is encoded in operon 1, which is SOS-induced independently of the SaPI life cycle, SOS-induced DNA damage promotes SaPI-mediated GT independently of SaPI transfer. This transfer, like phage-mediated GT, occurs with widely varying frequencies, depending on the similarity of the pseudo-pac site to the true SaPI pac site. Interestingly, SaPI-mediated GT has a strong preference for genes involved in iron metabolism and therefore impacts pathogenesis.

ACCESSORY GENES

The third class of SaPI genes is the accessory genes, mostly virulence genes—genes that have important beneficial roles for the host bacteria, aiding in their survival in the animal host, often by directly causing diseases. Unlike converting phages, which rarely carry more than one virulence gene, many SaPIs carry four or more, chiefly superantigens, though resistance genes and other accessory genes are also encountered, some of which have no obvious role in virulence. The accessory genes are located at either of two sites: between int and stl and downstream of terS. They are transcribed by promoters that are not under Stl control and therefore are usually expressed in the quiescent state. It is assumed that these genes were acquired from some foreign source by the intact SaPI. As is generally the case with converting phages, neither the source nor the mechanism of acquisition of most of the accessory genes by the SaPIs is known. An exception is the presence of the immune evasion gene, the staphylococcal complement interference gene, on some members of the SaPIbov5 family, a gene that also occurs on the converting prophage ɸSa3 (40). The observation that tst in SaPI1 and seb in SaPI3 are in the same location but in opposite orientations suggests that nonhomologous end joining may be the mechanism of their acquisition, even though nonhomologous end joining is very hard to demonstrate and is perhaps nonexistent in most bacteria. Indeed, one of the great unsolved mysteries of bacterial genetics is how certain genes have moved between genomes, movements that cannot be accounted for by known mechanisms of recombination.

A SaPI-Carried Determinant of Animal Adaptation

Staphylococci have evolved along with their animal hosts, and particular genotypes have come to be associated with particular animals (see chapter 46), implying that there are animal-specific bacterial genes or homologs. One such gene is carried by many members of the SaPIbov5 subset. This gene encodes a homolog of the von Willebrand factor binding protein, which is a coagulase and occurs in different allelic forms associated with SaPIs carried by staphylococci that are specific for different livestock; each allele specifically coagulates the plasma of the animal with which its SaPI is associated (41), suggesting that it is an animal-specific virulence factor. A nonspecific allele is also encoded by a chromosomal gene in most staphylococcal strains (41). Many of these SaPIs also carry an adenosine deaminase and the phage-derived staphylococcal complement interference protein (42). Others carry superantigen genes including TSST-O, a nontoxic variant of TSST-1, typical of ovine strains (43). An animal ST398 strain causing human endocarditis carried a SaPI of this type and had probably jumped from animal to human. Table 2 lists examples of the two known SaPI subsets.

Virulence Gene Clusters: Pretenders to the GI Throne

S. aureus strains encode several clusters of virulence-related genes: a cluster encoding serine protease-like (spl) proteins, one encoding exotoxin-like (set) proteins, a third encoding enterotoxin-like (egc) proteins, and a fourth encoding lipase-like (lpl) proteins. These sets of gene clusters are widely regarded as pathogenicity islands (40, 44) and are considered an important feature of the staphylococcal pathogenicity mobilome. However, because they are universally conserved among the available S. aureus genomes, they do not satisfy the primary island criterion, limited phylogenetic distribution (6), and moreover, they lack most island stigmata. It is suggested instead that despite their genomic organization and their potential role in pathogenesis, these clusters are not GIs and are not mobile but, rather, are sets of paralogous genes that evolved in situ by successive gene duplications, and though transferrable like other genes, this occurs by GT only.

SaPI EVOLUTION

We have proposed (see Fig. 1) that a proto-SaPI arose from a protoprophage by deletion; this was followed by evolutionary divergence resulting in several critical modifications that led to the currently extant SaPI genome as exemplified by SaPIs 1 and 2. SaPI evolution has resulted in deep divergence of all of the phage-related genes. Although these all retain a low degree of similarity to ancestral phage genes, they are much more closely related to cognate SaPI genes (10). Some of the extant SaPI genes, however, have no counterpart among prophages and are clearly products of the independent evolution of the SaPIs following their original split. The most important of these is operon 1, which is widely conserved and, as noted above, unlike the overall SaPI life cycle, is regulated by the SOS response (38). It contains three sets of genes that are responsible for phage interference and is responsible for gene transfer (39), all unique features of the SaPI life cycle. The similarity among SaPI genes also extends dramatically to genes of unknown function, encoding hypothetical proteins (HPs) that may or may not be translated. Most of these HP genes are well conserved among the SaPIs but have no detectable similarity to phage genes (10); phages have their own HPs that are not related to those of the SaPIs. This suggests that the HPs evolved in situ or were acquired following SaPI-phage divergence. Most important for the SaPI lifestyle is the possession of a master repressor that is counteracted by a phage-coded derepressor (17) rather than by the SOS response.

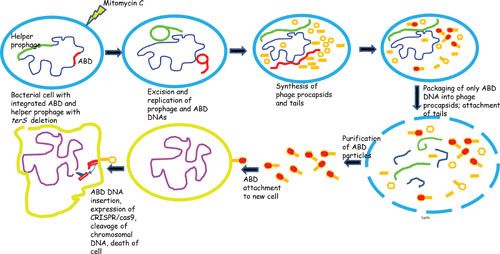

CONVERSION FROM WORKHORSE TO TROJAN HORSE: THE ABD STORY

Many years ago, Hope Ross, a research scientist in the Novick lab, realized that we could exploit the high-frequency transfer and great packaging capability of the SaPIs to create an effective delivery system and that if we added antistaphylococcal cargo to this system, we could convert the SaPIs into therapeutic islands and convert the workhorse into a Trojan horse. Accordingly, the genome of a typical SaPI1 family member, SaPI2, was modified by replacing the superantigen and other virulence and resistance genes with genes that, when expressed within a bacterial cell, would either kill the cell or block its virulence and thus cure an infection (Fig. 4). Several antibacterial cargo modules were added to this backbone vehicle (Fig. 5 and Table 5), including CRISPR-Cas9 with spacers matching either agrA or fnbB, CRISPR-dCas9 with a spacer matching the agr promoter region, and lsp, the gene for lysostaphin. This versatility was achieved by removing the capsid morphogenesis genes, causing the island to be packaged exclusively in full-sized phage particles, providing >30 kb of cloning space. Packaging in full-sized phage particles had no adverse effect on SaPI reproduction and actually increased SaPI transfer frequency (35). The terS gene of the helper prophage was also deleted, resulting in the production of mitomycin C-induced lysates that contained only SaPI particles, typically at titers of ∼1010/ml. These islands, known as antibacterial drones (ABDs), functioned as expected in vitro and cured mice infected subcutaneously or intraperitoneally with virulent staphylococci (45). It is planned to expand this system to other bacteria; it may help to counter the problem of antibiotic resistance.

FIGURE 4.

Induction, maturation, release, and cell killing by a CRISPR/cas9 ABD.

FIGURE 5.

Diagrammatic representation of the ABD backbone.

TABLE 5.

Existing and proposed ABDs based on SaPI2a

| SaPIs and ABDs | Size (kb) | Deletions | Insertions | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing | ||||

| SaPI2 (WT) | 15.7 | |||

| ABD2001 | 12.5 | cpmA&B tst eta | tetM | ABD backbone |

| ABD2002 | 17.6 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/cas9/nontargeting | Generic CRISPR/cas9 |

| ABD2003 | 17.6 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/cas9/agrA | Causes lethal DSB in agrA |

| ABD2004 | 17.6 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/cas9/hly | Causes lethal DSB in hly (listeriolysin O) |

| ABD2005 | 17.6 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/dcas9/nontargeting | Generic CRISPR/dcas9 |

| ABD2006 | 17.6 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/dcas9/agrP2P3 | Blocks virulence by inhibiting expression of agr locus |

| ABD2007 | 18.8 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/cas9/fnbpB | Causes lethal DSB in fnbpB |

| ABD2008 | 18.8 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/cas9/agrA/fnbpB | Causes lethal DSB in agrA and fnbpB |

| ABD2009 | 14.0 | cpmA&B tst eta | Isp | Secretes lysostaphin, lyses ABD-infected and surrounding uninfected cells |

| Proposed | ||||

| ABD2010 | 19.0 | cpmA&B tst eta | CRISPR/cas9/agrA/Isp | Causes lethal DSB in agrA |

| ABD2011 | 14.5 | cpmA&B tst eta | dut | Replicates autonomously |

| ABD2012 | 18.3 | cpmA&B tst eta | dut, hybrid agr-com, anti-spa RNAIII, anti-agrA, anti-secY | Replicates autonomously; blocks agr, spa, PSMs, secY expression |

| ABD2013 | 14.9 | cpmA&B tst eta | dut, rsbW, icaR | Replicates autonomously, clocks biofilm formation |

| ABD2014 | 16.2 | cpmA&B tst eta | pezT, ghoT | Kills ABD-infected staphylococci |

Abbreviations: agrA, agr response regulator; fnbA, fibronectin binding protein A; DSB, double-strand break; dut, dUTPase gene; com, competence; spa, staphylococcal protein A; secY, gene for secretory protein Y; PSM, phenol-soluble modulin; rsbW, inhibitor of sigB activation; icaR, regulatory gene for biofilm-promoting ica operon; pezT and ghoT – toxins of TA systems; WT, wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayes W. 1968. The Genetics of Bacteria and their Viruses, 2nd ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan E, Saedler H, Starlinger P. 1967. Strong-polar mutations in the transferase gene of the glactose operon in E coli. P. Mol Gen Genet 100:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summers DK. 1996. The Biology of Plasmids. Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, UK. 10.1002/9781444313741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum G, Ott M, Lischewski A, Ritter A, Imrich H, Tschäpe H, Hacker J. 1994. Excision of large DNA regions termed pathogenicity islands from tRNA-specific loci in the chromosome of an Escherichia coli wild-type pathogen. Infect Immun 62:606–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damle PK, Wall EA, Spilman MS, Dearborn AD, Ram G, Novick RP, Dokland T, Christie GE. 2012. The roles of SaPI1 proteins gp7 (CpmA) and gp6 (CpmB) in capsid size determination and helper phage interference. Virology 432:277–282 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.026. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernikos GS, Parkhill J. 2008. Resolving the structural features of genomic islands: a machine learning approach. Genome Res 18:331–342 10.1101/gr.7004508. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay JA, Ruzin A, Ross HF, Kurepina N, Novick RP. 1998. The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 29:527–543 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00947.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald JR, Monday SR, Foster TJ, Bohach GA, Hartigan PJ, Meaney WJ, Smyth CJ. 2001. Characterization of a putative pathogenicity island from bovine Staphylococcus aureus encoding multiple superantigens. J Bacteriol 183:63–70 10.1128/JB.183.1.63-70.2001. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quiles-Puchalt N, Carpena N, Alonso JC, Novick RP, Marina A, Penadés JR. 2014. Staphylococcal pathogenicity island DNA packaging system involving cos-site packaging and phage-encoded HNH endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:6016–6021 10.1073/pnas.1320538111. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novick RP, Ram G. 2016. The floating (pathogenicity) island: a genomic dessert. Trends Genet 32:114–126 10.1016/j.tig.2015.11.005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-Rubio R, Quiles-Puchalt N, Martí M, Humphrey S, Ram G, Smyth D, Chen J, Novick RP, Penadés JR. 2017. Phage-inducible islands in the Gram-positive cocci. ISME J 11:1029–1042 10.1038/ismej.2016.163. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick RP, Christie GE, Penadés JR. 2010. The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:541–551 10.1038/nrmicro2393. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu H, Sampson L, Parr R, Casjens S. 2002. The DNA site utilized by bacteriophage P22 for initiation of DNA packaging. Mol Microbiol 45:1631–1646 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03114.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bento JC, Lane KD, Read EK, Cerca N, Christie GE. 2014. Sequence determinants for DNA packaging specificity in the S. aureus pathogenicity island SaPI1. Plasmid 71:8–15 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.12.001. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Carpena N, Quiles-Puchalt N, Ram G, Novick RP, Penadés JR. 2015. Intra- and inter-generic transfer of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence genes by cos phages. ISME J 9:1260–1263 10.1038/ismej.2014.187. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ubeda C, Barry P, Novick RP, Penades JR. 2008. Characterization of mutations defining SaPI functions and enabling autonomous replication in the absence of helper phage. Mol Microbiol 67:493–503 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06027.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tormo-Más MA, Mir I, Shrestha A, Tallent SM, Campoy S, Lasa I, Barbé J, Novick RP, Christie GE, Penadés JR. 2010. Moonlighting bacteriophage proteins derepress staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. Nature 465:779–782 10.1038/nature09065. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemire S, Figueroa-Bossi N, Bossi L. 2011. Bacteriophage crosstalk: coordination of prophage induction by trans-acting antirepressors. PLoS Genet 7:e1002149 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002149. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tormo-Más MA, Donderis J, García-Caballer M, Alt A, Mir-Sanchis I, Marina A, Penadés JR. 2013. Phage dUTPases control transfer of virulence genes by a proto-oncogenic G protein-like mechanism. Mol Cell 49:947–958 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.013. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penadés JR, Donderis J, García-Caballer M, Tormo-Más MA, Marina A. 2013. dUTPases, the unexplored family of signalling molecules. Curr Opin Microbiol 16:163–170 10.1016/j.mib.2013.02.005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christie GE, Dokland T. 2012. Pirates of the Caudovirales. Virology 434:210–221 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.028. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowring J, Neamah MM, Donderis J, Mir-Sanchis I, Alite C, Ciges-Tomas JR, Maiques E, Medmedov I, Marina A, Penadés JR. 2017. Pirating conserved phage mechanisms promotes promiscuous staphylococcal pathogenicity island transfer. eLife 6:e26487 10.7554/eLife.26487. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frígols B, Quiles-Puchalt N, Mir-Sanchis I, Donderis J, Elena SF, Buckling A, Novick RP, Marina A, Penadés JR. 2015. Virus satellites drive viral evolution and ecology. PLoS Genet 11:e1005609 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005609. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Novick RP. 2009. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science 323:139–141 10.1126/science.1164783. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruzin A, Lindsay J, Novick RP. 2001. Molecular genetics of SaPI1: a mobile pathogenicity island in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 41:365–377 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02488.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subedi A, Ubeda C, Adhikari RP, Penadés JR, Novick RP. 2007. Sequence analysis reveals genetic exchanges and intraspecific spread of SaPI2, a pathogenicity island involved in menstrual toxic shock. Microbiology 153:3235–3245 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006932-0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ubeda C, Tormo-Más MA, Penadés JR, Novick RP. 2012. Structure-function analysis of the SaPIbov1 replication origin in Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid 67:183–190 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.01.006. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim KJ, Sunshine MG, Lindqvist BH, Six EW. 2001. Capsid size determination in the P2-P4 bacteriophage system: suppression of sir mutations in P2’s capsid gene N by Supersid mutations in P4’s external scaffold gene sid. Virology 283:49–58 10.1006/viro.2001.0853. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diana C, Dehò G, Geisselsoder J, Tinelli L, Goldstein R. 1978. Viral interference at the level of capsid size determination by satellite phage P4. J Mol Biol 126:433–445 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carpena N, Manning KA, Dokland T, Marina A, Penadés JR. 2016. Convergent evolution of pathogenicity islands in helper cos phage interference. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371:371 10.1098/rstb.2015.0505. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ubeda C, Olivarez NP, Barry P, Wang H, Kong X, Matthews A, Tallent SM, Christie GE, Novick RP. 2009. Specificity of staphylococcal phage and SaPI DNA packaging as revealed by integrase and terminase mutations. Mol Microbiol 72:98–108 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06634.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maiques E, Ubeda C, Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Lasa I, Novick RP, Penadés JR. 2007. Role of staphylococcal phage and SaPI integrase in intra- and interspecies SaPI transfer. J Bacteriol 189:5608–5616 10.1128/JB.00619-07. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poliakov A, Chang JR, Spilman MS, Damle PK, Christie GE, Mobley JA, Dokland T. 2008. Capsid size determination by Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island SaPI1 involves specific incorporation of SaPI1 proteins into procapsids. J Mol Biol 380:465–475 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.065. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Maiques E, Ubeda C, Selva L, Lasa I, Calvete JJ, Novick RP, Penadés JR. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island DNA is packaged in particles composed of phage proteins. J Bacteriol 190:2434–2440 10.1128/JB.01349-07. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ram G, Chen J, Kumar K, Ross HF, Ubeda C, Damle PK, Lane KD, Penadés JR, Christie GE, Novick RP. 2012. Staphylococcal pathogenicity island interference with helper phage reproduction is a paradigm of molecular parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:16300–16305 10.1073/pnas.1204615109. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ram G, Ross HF, Novick RP. 2014. Precisely modulated SaPI interference with late phage gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4536–4541 10.1073/pnas.1406749111. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radman M. 1975. SOS repair hypothesis: phenomenology of an inducible DNA repair which is accompanied by mutagenesis. Basic Life Sci 5A:355–367. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ubeda C, Maiques E, Tormo MA, Campoy S, Lasa I, Barbé J, Novick RP, Penadés JR. 2007. SaPI operon I is required for SaPI packaging and is controlled by LexA. Mol Microbiol 65:41–50 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05758.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Ram G, Penades JR, Brown S, Novick RP. 2014. Pathogenicity island-directed transfer of unlinked chromosomal virulence genes. Mol Cell 57:138–149. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baba T, Takeuchi F, Kuroda M, Yuzawa H, Aoki K, Oguchi A, Nagai Y, Iwama N, Asano K, Naimi T, Kuroda H, Cui L, Yamamoto K, Hiramatsu K. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819–1827 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viana D, Blanco J, Tormo-Más MA, Selva L, Guinane CM, Baselga R, Corpa J, Lasa I, Novick RP, Fitzgerald JR, Penadés JR. 2010. Adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus to ruminant and equine hosts involves SaPI-carried variants of von Willebrand factor-binding protein. Mol Microbiol 77:1583–1594 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07312.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, van Roon J, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, van Wamel WJ. 2006. Early expression of SCIN and CHIPS drives instant immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Microbiol 8:1282–1293 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00709.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray DL, Prasad GS, Earhart CA, Leonard BAB, Kreiswirth BN, Novick RP, Ohlendorf DH, Schlievert PM. 1994. Immunobiologic and biochemical properties of mutants of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. J Immunol 152:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon BY, Park JY, Hwang SY, Robinson DA, Thomas JC, Fitzgerald JR, Park YH, Seo KS. 2015. Phage-mediated horizontal transfer of a Staphylococcus aureus virulence-associated genomic island. Sci Rep 5:9784 10.1038/srep09784. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ram G, Ross HR, Novick RP, Rodriguez-Pagan I, Jiang D. 2018. Conversion of staphylococcal pathogenicity islands into CRISPR-carrying antibacterials. Nat Biotechnol 36:971–976. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]