A student might find a particular question threatening and intimidating in one context yet stimulating and challenging in a different context. What makes one learning context unpleasant and another pleasant?

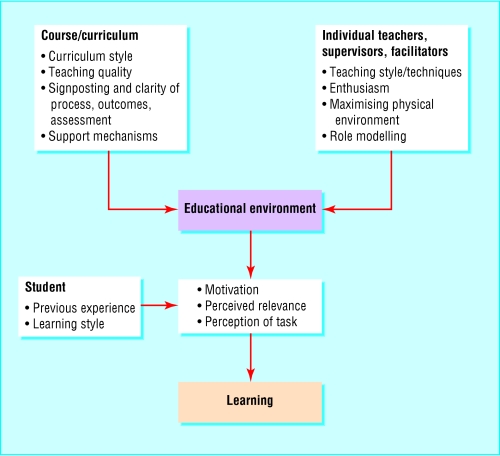

Learning depends on several factors, but a crucial step is the engagement of the learner. This is affected by their motivation and perception of relevance. These, in turn, can be affected by learners' previous experiences and preferred learning styles and by the context and environment in which the learning is taking place. In adult learning theories, teaching is as much about setting the context or climate for learning as it is about imparting knowledge or sharing expertise.

Motivation

Motivation can be intrinsic (from the student) and extrinsic (from external factors). Assessments are usually a strong extrinsic motivator for learners. Individual learners' intrinsic motivation can be affected by previous experiences, by their desire to achieve, and the relevance of the learning to their future.

A teacher's role in motivation should not be underestimated. Enthusiasm for the subject, interest in the students' experiences, and clear direction (among other things) all help to keep students' attention and improve assimilation of information and understanding.

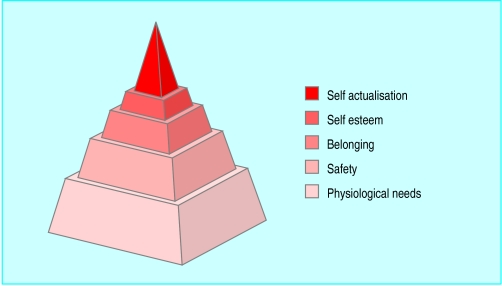

Even with good intrinsic motivation, however, external factors can demotivate and disillusion. Distractions, unhelpful attitudes of teachers, and physical discomfort will prompt learners to disengage. Maslow described a model to illustrate the building blocks of motivation. Each layer needs to be in place before the pinnacle of “self actualisation” is reached.

Physiological needs

Although the need to be fed, watered, and comfortable seems trite, many teachers will have experienced, for example, the difficulties of running sessions in cold or overheated rooms, in long sessions without refreshments, in noisy rooms, in facilities with uncomfortable seating.

Physical factors can make it difficult for learners and teachers to relax and pay attention. Ensuring adequate breaks and being mindful of the physical environment are part of the teacher's role.

Case history: safe environment

Dr Holden claims to use interactive teaching techniques. She introduces the topic then points to a student in the audience and says, “tell me five causes of cyanosis.” Each student will get asked questions in the session, and most spend their time worrying about when it is their turn to be “exposed.”

After a course on teaching skills, she runs the same session. After the introduction, she tells the students to turn to their neighbour and together come up with some possible causes of cyanosis. After a couple of minutes of this “buzz group” activity, she asks for one suggestion from each group until no new suggestions are made. The suggestions are then discussed with reference to the aims of the session.

Safety

A teacher should aim to provide an environment in which learners feel safe to experiment, voice their concerns, identify their lack of knowledge, and stretch their limits. Safety can be compromised, for example, through humiliation, harassment, and threat of forced disclosure of personal details.

Teachers can create an atmosphere of respect by endorsing the learners' level of knowledge and gaps in knowledge as essential triggers to learning rather than reasons for ridicule.

Remembering names and involving the learners in setting ground rules are other examples of building mutual trust. Feedback on performance, a vital part of teaching, should be done constructively and with respect for the learner.

Belonging

Many factors help to give a student a sense of belonging in a group or team—for example, being a respected member, having one's voice heard and attended to, being given a useful role, and having colleagues with similar backgrounds, experiences, and goals.

Case history: sense of belonging

Five medical students arrive at a distant hospital for a four week attachment. They are met by a staff member, shown around the unit, canteen, library, and accommodation. They are given name badges in the style of the existing staff, and after a couple of days are given specific roles on the unit. These roles develop over the weeks. There is little set teaching time, but the students feel free to ask any staff member for more details at quieter times.

After the attachment, they meet up with friends who were placed elsewhere. Their experience was different. No one was expecting them when they arrived, and ward and clinic staff were unhelpful. There was a set teaching programme and an enthusiastic teacher, but the students were relieved that the hospital was near a town centre with good shops and nightlife.

Learners are motivated through inclusion and consultation. Their input to a course's objectives and structure should be sought, valued, and acted on. On clinical placements, staff should help to prevent medical students from feeling ignored, marginalised, or “in the way.” Students should instead be valued as assets to a clinical unit or team.

Self esteem

Several of the points mentioned above feed directly into self esteem through making the learner feel valued. Praise, words of appreciation, and constructive rather than destructive criticism are important. It can take many positive moments to build self esteem, but just one unkind and thoughtless comment to destroy it.

Case history: self esteem

A senior house officer (SHO) is making slow but steady progress. His confidence is growing and the level of supervision he requires is lessening. On one occasion, however, his case management is less than ideal, although the patient is not harmed or inconvenienced. The consultant feels exasperated and tells the SHO that everyone is carrying him and it still isn't working. The SHO subsequently reverts to seeking advice and permission for all decision making.

Doctors are well used to their role in the doctor-patient relationship. Some find it hard to translate the same skills and attitudes to the teacher-student relationship. Their own experience of education or their own distractions, time pressures, and other stresses may be factors.

Self actualisation

If a teacher has attended to the above motivational factors, then they have sought to provide the ideal environment in which a learner can flourish.

An ethos that encourages intrinsic motivation without anxiety is conducive to a “deep” learning approach. However, there may be some who remain unable to respond to the education on offer. Teachers may need to consider whether the course (or that particular piece of study) is suitable for that student.

Relevance

The relevance of learning is closely linked to motivation: relevance for immediate needs, for future work, of getting a certificate or degree regardless of content. Learning for learning's sake is back in vogue in higher education after a move towards vocational or industrial preparation.

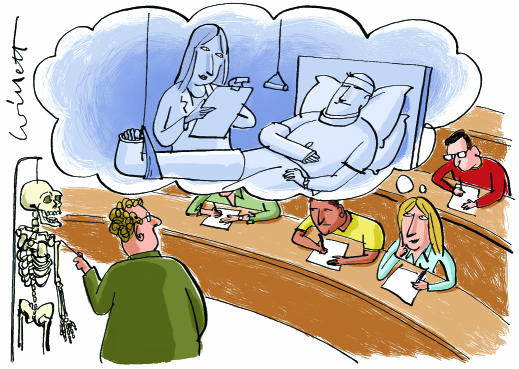

Certain courses in medical degrees have been notoriously poorly received by students. Faculty members need to explain to students why these courses are necessary and how they link to future practice. Allowing them to see for themselves, through early clinical exposure and experience, is likely to be helpful. Similarly, learning the basic medical sciences in the context of clinical situations is the basis for problem based learning.

If a teacher is asked to do a one-off session with learners they don't know, he or she should prepare—both before and at the start of the session—by determining what the learners know, want to know, and expect to learn. This involves and shows respect for the learners and encourages them to invest in the session

Students' perception of the relevance of what they are being taught is a vital motivator for learning

Case history: role models

Dr Jones is a well known “character” in the hospital. Medical students sitting in his clinic hear him talk disparagingly about nurses, patients, and the new fangled political correctness about getting informed consent that wastes doctors' time. Most students are appalled; but a few find him engaging—they view him as a “real” doctor, unlike the ethics or communication skills lecturers.

A challenging problem is the trainee who is in a post because he or she needs to do it for certification, although it is of no perceived value to the trainee's future career direction. A balance needs to be negotiated between respect for the individual's needs and the expectation of a level of professional conduct.

Teacher as role model

The teacher or facilitator is one of the most powerful variables in the educational environment. The teacher's actions, attitudes (as evidenced by tone of voice, comments made), enthusiasm, and interest in the subject will affect learners indirectly. The capacity for subliminal messages is enormous. Inappropriate behaviour or expression by a staff member will be noticed; at worst the learners will want to emulate that behaviour, at best they will have been given tacit permission to do so.

It is easy to “learn” attitudes—including poor attitudes. Attitudes are learnt through observation of those in relative power or seniority. Teachers must therefore be aware of providing good role modelling in the presence of students

Maximising educational environment

Classroom, tutorials, seminars, lectures

Room temperature, comfort of seating, background noise, and visual distractions are all factors of the environment that can affect concentration and motivation. Some are within the teacher's control, others not.

Checklist to ensure good physical environment

Is the room the right size?

Is the temperature comfortable?

Are there distractions (noise, visual distractions inside or outside)?

Is the seating adequate, and how should it be arranged?

Does the audiovisual equipment work?

Respect for the learners and their needs, praise, encouragement of participation can all lead to a positive learning experience. Lack of threat to personal integrity and self esteem is essential, although challenges can be rewarding and enjoyable.

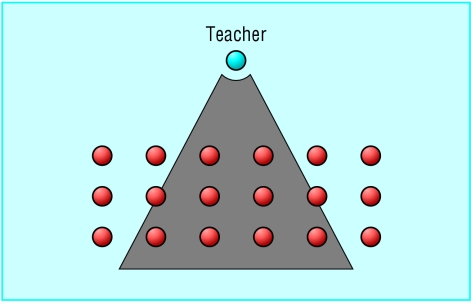

Small group teaching facilitates individual feedback, but the seating arrangement used will have an important effect on student participation. If, for example, students sit in traditional classroom rows, those on the edges will feel excluded. A circular format encourages interaction. It allows the teacher to sit alongside a talkative person, thus keeping them out of eye contact and reducing their input. A quiet student can be placed opposite to encourage participation through non-verbal means. Students can also work in unfacilitated groups on a topic, enabling them to work in teams and share the learning tasks.

Clinical settings

In real life settings, the dual role of teacher and clinician can be complicated. The students will be closely observing the clinician, picking up hidden messages about clinical practice. They need to feel that there is no danger that they will unnecessarily distress or harm patients or their families. They also need to feel safe from humiliation. Making them feel welcomed and of value when they arrive at a new placement or post will aid their learning throughout.

Checklist for teaching in clinical settings

Have patients and families given consent for students to be present?

Do the staff know that teaching is planned and understand what their roles will be?

Is there adequate space for all participants?

How much time is available for teaching?

How may the students be made to feel useful (for example, “pre-clerking” and presenting)?

Course and curriculum design

The designers of short and long courses should consider the relevance of the learning environment to the potential learners. Student representation on curriculum committees is one means of ensuring a more student centred course.

The aims, objectives, and assessments should be signposted well in advance of a course and should be demonstrably fair. The teaching methods should build on learners' experience, creating a collaborative environment. Disseminating the findings of course evaluations, followed by staff training, helps to identify and correct undesirable behaviour among faculty members. Evaluations should also include a means for reviewing the course's aims and objectives with the students.

Further reading

Newble D, Cannon R. A handbook for medical teachers. 3rd ed. London: Kluwer Academic, 1994.

Eraut M. Developing professional knowledge and competence. London: Falmer, 1994.

Welsh I, Swann C. Partners in learning: a guide to support and assessment in nurse education. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 2002.

Norman GR, Schmidt HG. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: a review of the evidence. Acad Med 1992;67:557-65

Dent JA, Harden RM. A practical guide for medical teachers. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

In longer courses, student support systems and informal activities that build collective identity must be considered. Students who are having difficulties need to be identified early and given additional support.

Figure.

Many factors influence learning

Figure.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs for motivating learning. Adapted from Maslow A H. Motivation and Personality, New York: Harper and Row, 1954

Figure.

Traditional teaching can leave some students excluded (that is, outside the “triangle of influence”)

Footnotes

The ABC of learning and teaching in medicine is edited by Peter Cantillon, senior lecturer in medical informatics and medical education, National University of Ireland, Galway, Republic of Ireland; Linda Hutchinson, director of education and workforce development and consultant paediatrician, University Hospital Lewisham; and Diana F Wood, deputy dean for education and consultant endocrinologist, Barts and the London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London. The series will be published as a book in late spring.