Abstract

T cells are central players in the immune response to infectious disease, with the specificity of their responses controlled by the T-cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex on the cell surface. Impairment of TCR/CD3-directed CD4+ T-cell immune responses is frequently observed in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 (HIV-1 and HIV-2). Virus replication is also regulated by T-cell activation factors, with HIV-1 and HIV-2 responding to different TCR/CD3-directed cellular pathways. We previously demonstrated that HIV-1 infection of the human interleukin-2-dependent CD4+ T-cell line WE17/10 abrogates TCR/CD3 function and surface expression by a specific loss of CD3-γ gene transcripts. In this study, we show that HIV-2 provokes the same molecular defect in CD3-γ gene transcripts, resulting in a similar but delayed progressive loss of TCR/CD3 surface expression after infection.

The principal etiologic agent of AIDS is human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (5, 24), although infection with HIV-2 (16, 38), a related lentivirus found predominantly in West Africa, produces a clinically similar disease. An important pathogenic difference between these viruses is that disease develops much more slowly in HIV-2-seropositive than in HIV-1-seropositive individuals (52). While this difference remains largely unexplained, it is thought that there is a correlation between clinical evolution and viral activities at the cellular level.

Many studies have compared HIV-1 and HIV-2 gene expression and function as well as their genetic diversity in an effort to identify the molecular basis for this variation in viral pathogenesis. HIV-1 and HIV-2 have significant sequence divergence (±40% homology, depending on the variant) (29), although the two viruses are similar in genomic organization, share mechanisms of transactivation, and encode gene products with biologically similar functions (23, 90). Replication of both HIV-1 and HIV-2 is transcriptionally regulated in response to T-cell activation factors; however, each virus has a specific set of transcriptional control elements contained within its LTR (long terminal repeat), with enhancer stimulation mediated by different sets of activation-induced cellular proteins (32, 33, 44, 50, 51, 70). For example, monoclonal antibodies to the T-cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex stimulate production of HIV-2 but not HIV-1 from latently infected T-cell lines, while HIV-2 is less responsive than HIV-1 to stimulation by tumor necrosis factor alpha (32).

Impairment of the TCR/CD3 activation pathway is often observed early in disease progression after HIV-1 infection, with functional loss of receptor-directed immune responses found in T cells from asymptomatic HIV-1-seropositive individuals and patients with AIDS (17, 34, 43, 55, 62, 66). The molecular or cellular processes defining the relationship between viral gene transcription and TCR/CD3-regulated pathways have not yet been identified. However, in vitro studies have described suppression of TCR/CD3-directed activation by the virally encoded proteins gp120 (13, 22, 45, 56, 60, 68), Nef (25, 35, 46, 63), and Tat (54, 66, 77). Recently, CD3 expression was found to be quantitatively reduced with advancing disease stages on both activated and resting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals (27). Other studies found that the TCR/CD3 signaling chain CD3-ζ, but not CD3-ɛ, was significantly decreased in T cells from symptomatic AIDS patients as well as those from individuals in the acute and early asymptomatic stages of HIV-1 infection (64, 71). These studies used flow cytometry to quantify the amount of CD3-ɛ and CD3-ζ protein present but did not examine mRNA transcripts for any of the receptor chains. CD3-ζ has a significant role in TCR/CD3 receptor signal transduction (36, 58, 59), but recent studies show that it is rapidly turned over independent of TCR/CD3 complex formation and surface expression, suggesting that it may not be a critical assembly and transport limiting factor for surface expression (57). Alternatively, many studies have shown that CD3-γ plays a critical role in receptor downregulation after engagement and triggering of the TCR/CD3 complex (8, 10–12, 19–21, 31, 41, 48, 79). We previously demonstrated that productive HIV-1 infection of the interleukin-2 (IL-2)-dependent CD4+ T-cell line WE17/10 abrogates TCR/CD3 surface expression due to a specific defect in CD3-γ gene transcripts (84). Examination of receptor density on the surface of WE17/10 cells revealed that TCR/CD3 complexes (and CD3-γ gene transcripts) are quantitatively reduced early after HIV-1 infection, and receptor function and expression are progressively impaired (83). Thus, the defect in CD3-γ gene transcripts observed in HIV-1-infected WE17/10 cells causes a progressive loss of receptor surface expression and function as the cells transition from TCR/CD3hi to TCR/CD3lo to TCR/CD3−.

We questioned whether the diversity of HIV-1 genotypes and phenotypes or cellular selection pressures generated in vitro was responsible for this progressive decrease in TCR/CD3 surface complexes. We found that interference with CD3-γ gene transcripts was not restricted to infection with a given HIV-1 variant or to changes in HIV-1 quasispecies during in vitro infection (83). Furthermore, the absence of changes in the viability or doubling times of the chronically infected cells, the spontaneous reversion of CD3-γ downmodulation in two HIV-1 infected cell lines, and the consistent appearance of the intermediate TCR/CD3lo phenotype strongly suggest that in vitro selection of a CD3-γ chain mutant subpopulation does not account this defect (83). In our ongoing search for a link between viral and cellular regulatory processes that play a role in these events, we asked whether loss of CD3-γ gene expression was specific for infection with HIV-1 and therefore related to differences in the responsiveness of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 LTRs to T-cell activation factors. Evidence presented in this study shows that HIV-2 infection of WE17/10 cells also provokes a loss of CD3-γ gene transcripts, characterized by progressive diminution of TCR/CD3 surface density, which parallels but is delayed in comparison with that previously reported for HIV-1 (83, 84).

Infection of WE17/10 cells with HIV-1 and HIV-2.

The WE17/10 cell line is a human IL-2-dependent CD4+ T-cell line that was established and characterized as previously described (84). WE17/10 cells were synchronized by IL-2 deprivation and infected with 0.1 infectious unit of HIV-1 or HIV-2 per cell as previously described for HIV-1 (83, 84). Control WE17/10 cells were mock infected and carried in parallel passages for each infection experiment. The HIV-2 variants HIV-2MS (from Phyllis Kanki) and HIV-2MVP-15132 (28) (referred to here as HIV-2MVP; from Lutz Gürler and Friedrich Deinhardt) were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The LAV-1 strain (5) (now known to be HIV-1 strain Lai [78]) was provided by F. Barré-Sinoussi; the molecularly cloned HIV-1 genome, HXB2 (61), was obtained from B. Hahn and G. M. Shaw through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

For the first 3 weeks following infection, fractions of the infected and uninfected cell cultures were removed every 2 to 3 days, counted for viability by trypan blue exclusion, and fixed and stained by indirect immunofluorescence. The cells were labeled with immunoglobulins purified from a pool of HIV-1- or HIV-2-positive human sera followed by fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) and counted to determine the percentage of infected cells. HIV-1/HIV-2 viral antigen (p24/p26) content in the culture supernatant was determined by the Innotest HIV-1/HIV-2 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium).

WE17/10 cells acutely infected with either HIV-1 (WE/HIV-1HXB2 or WE/HIV-1LAI) or HIV-2 (WE/HIV-2MS or WE/HIV-2MVP) exhibited decreased cell viability and a progressive decline in growth rate during the peak of virus production that followed 100% infection. The maximum levels of viral p24/26 antigen at the peak of acute infection were consistently between 180 and 200 ng/ml for cells infected with the HIV-1 isolates and between 160 and 180 ng/ml for cells infected with the HIV-2 isolates. The maximum levels were slightly lower for the HIV-2 isolates than for the HIV-1 isolates, possibly a reflection of subtle differences in the sensitivity of the Innogenetics HIV1/HIV-2 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for each virus. In 10 experimental infections with either HIV-1LAI or HIV-1HXB2, 100% of WE17/10 cells were productively infected after an average of 17 days postinfection (p.i.; range, 11 to 24 days). In eight experimental infections with either HIV-2MS or HIV-2MVP, 100% of WE17/10 cells were productively infected after an average of 15 days p.i. (range, 7 to 25 days). This acute, productive phase of infection generally lasted for 1 to 2 weeks and was followed by a quiescent period during which the cells grew slowly. Normal growth (doubling time, ±24 h) returned within the following 3 weeks, and these chronically infected cell lines could be maintained in culture indefinitely thereafter. The patterns of acute infection were quite similar for all of the WE/HIV-1HXB2, WE/HIV-1LAI, WE/HIV-2MS, and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines. It is important to note that some of the original virus isolates required mycoplasma decontamination before this typical progression of acute infection was observed (data not shown).

TCR/CD3 and CD4 surface expression after HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection of WE17/10 cells.

Kinetic changes in the amount of CD2, CD3, CD4, and CD5 expressed on the surface of the infected WE/HIV-1HXB2, WE/HIV-1LAI, WE/HIV-2MS, and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines, in comparison with the mock-infected WE17/10 cell line, were monitored for 50 to 60 weeks p.i. The murine monoclonal antibodies used included OKT.3 (anti-CD3; Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Beerse, Belgium), OKT.4 (anti-CD4 that recognizes a non-HIV-1 binding epitope; Ortho), Leu-1 (anti-CD5; Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem-Aalst, Belgium; negative control [data not shown]), and Leu5b (anti-CD2; Becton Dickinson). The cells were labeled and analyzed on a FACStar Plus (Becton Dickinson) as previously described (83, 84). The WE17/10, WE/HIV-1, and WE/HIV-2 cell lines all consistently and uniformly expressed CD2 (positive control) on 100% of the cell population after infection. The mean fluorescence values for CD2 on the infected cells were routinely equal to or higher than values for the mock-infected cells, as previously described by others (27).

A significant reduction in CD4 surface expression was detected in all of the productively infected WE/HIV-1HXB2, WE/HIV-1LAI (Table 1), WE/HIV-2MS, and WE/HIV-2MVP (Table 2) cell lines. This decrease was due to a decline in CD4 mean fluorescence, which was characterized by a loss of receptor surface density on 100% of the cells rather than the appearance of a CD4-negative subpopulation (84). In general, CD4 surface expression on the WE/HIV-1HXB2 and WE/HIV-2MS cell lines declined to 10 to 20% of the values for the mock-infected WE17/10 cells after the acute phase of infection. Alternatively, loss of CD4 surface receptor density on the WE/HIV-1LAI and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines was less substantial, with a maximum drop to 30 to 45% of control values. These chronically infected WE/HIV-1 and WE/HIV-2 cell lines all maintained their low CD4 expression levels during the year-long infection experiment. The level of p24/26 antigen detected in the culture supernatant of the chronically infected WE/HIV-1 and WE/HIV-2 cell lines declined over time p.i. in a manner similar to that previously described for HIV-1 (83). However, this decrease was not correlated with alterations in the level of CD4 surface density (data not shown). The lower CD4 surface expression found on cells infected with HIV-1HXB2 and HIV-2MS compared to cells infected with HIV-1LAI and HIV-2MVP may reflect differences in the expression of one or more specific viral gene products. The viral proteins Vpu (85, 86), Env (13), and Nef (1, 2) have all been shown to be independently capable of downmodulating CD4, with Nef active in the early phase of virus infection and Vpu (expressed only in HIV-1) (65) and Env acting in the later stages of infection (14). The combination of all three is more effective than any one or two, with their concerted actions required for maximal downmodulation of CD4. This finding suggests that expression of Env and/or Nef may be lower in the WE/HIV-1LAI and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines than in the WE/HIV-1HXB2 and WE/HIV-2MS cell lines.

TABLE 1.

CD4 expression on HIV-1-infected WE17/10 cell lines postinfection

| Month p.i. | % Positive cellsa (mean fluorescence)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WE17/10 | WE/HIV-1LAI | WE/HIV-1HXB2 | |

| 1 | 100 (1,926) | 97 (1,874) | |

| 100 (780) | 94 (735) | ||

| 2 | 100 (914) | 100 (922) | 21 (194) |

| 4 | 100 (545) | 36 (194) | 11 (61) |

| 5 | 100 (826) | 38 (310) | 16 (136) |

| 6 | 100 (790) | 31 (247) | 17 (134) |

| 7 | 100 (834) | 39 (325) | 16 (134) |

| 8 | 100 (994) | 38 (319) | 18 (175) |

| 9 | 100 (365) | 39 (144) | 22 (80) |

| 10 | 100 (255) | 35 (90) | 32 (81) |

| 11 | 100 (1,397) | 39 (546) | 19 (265) |

| 12 | 100 (1,214) | 37 (454) | 26 (321) |

For the WE/HIV-1-infected cell lines, the percentage was calculated from a ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity (given in parentheses) for the infected cells to that for the mock-infected WE17/10 cells (considered 100%), which were labeled with anti-CD4 in the same experiment.

TABLE 2.

CD4 expression on HIV-2-infected WE17/10 cell lines postinfection

| Month p.i. | % Positive cellsa (mean fluorescence)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WE17/10 | WE/HIV-2MVP | WE/HIV-2MS | |

| 1 | 100 (699) | 39 (275) | |

| 100 (943) | 21 (194) | ||

| 4 | 100 (1,682) | 33 (565) | |

| 100 (967) | 27 (264) | ||

| 5 | 100 (1,682) | 11 (178) | |

| 6 | 100 (703) | 40 (282) | |

| 7 | 100 (686) | 48 (332) | 12 (86) |

| 8 | 100 (881) | 41 (363) | 10 (89) |

| 9 | 100 (1,511) | 45 (678) | 14 (212) |

| 10 | 100 (934) | 38 (354) | 12 (112) |

| 12 | 100 (244) | 40 (97) | 12 (30) |

| 14 | 100 (1,383) | 33 (454) | |

For the WE/HIV-2-infected cell lines, the percentage was calculated from a ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity (given in parentheses) for the infected cells to that for the mock-infected WE17/10 cells (considered 100%), which were labeled with anti-CD4 in the same experiment.

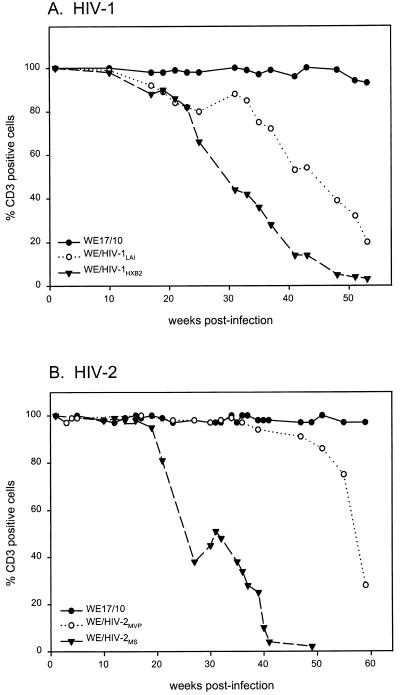

Loss of TCR/CD3 receptor complexes on the surface of both HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected cells follows a pattern that is distinct from that observed for CD4. Immediately following the early acute/cytopathic phase of infection (generally between 3 and 5 weeks p.i.), 99 to 100% of the cells were TCR/CD3+ (comparable to the mock-infected cells). Subsequent, systematic kinetic analysis of the chronically infected cell lines revealed the initial appearance of 5 to 10% TCR/CD3− cells at between 6 and 16 weeks in 10 WE/HIV-1LAI and WE/HIV-1HXB2 cell lines (the kinetics of receptor loss for several WE/HIV-1 cell lines are shown either in Fig. 1A or in previous publications [83, 84]) and after 16 to 34 weeks in eight WE/HIV-2MS and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines (representative experiments are shown in Fig. 1B). TCR/CD3− cells were defined for each experimental time point as those outside the region delineated by the mock-infected control. The kinetics shown in Fig. 1 illustrates that TCR/CD3− cells appear earlier in HIV-1-infected than in HIV-2-infected cells. The relevance of this observation to known differences in the rate of disease development after in vivo infection with HIV-1 or HIV-2 (52) is unknown. Once the cell population drops below 80% TCR/CD3+ cells, a steady decline to the TCR/CD3− phenotype generally ensues; however, the rate of progression to a majority of receptor-negative cells can vary widely between isolates of both HIV-1 and HIV-2. Occasionally, this progressive downregulation of receptor expression was temporarily observed to spontaneously reverse itself in some of the infected cell lines (such as that seen for WE/HIV-2MS and to a lesser extent WE/HIV-1LAI in Fig. 1). Overall, we found that while there was kinetic variation, the sequences of changes in TCR/CD3 surface expression were similar for the HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected cell lines.

FIG. 1.

Evolution of TCR/CD3 surface expression for WE/HIV-1LAI and WE/HIV-1HXB2 cells (A) and WE/HIV-2MVP and WE/HIV-2MS cells (B) in comparison with the mock-infected WE17/10 controls. The TCR/CD3+ cell population is defined as the percentage of anti-CD3 labeled cells that fall within the region defined by the histogram of the uniformly positive mock-infected WE17/10 cells.

Modulation of TCR/CD3 surface density after infection of WE17/10 cells with HIV-1 or HIV-2.

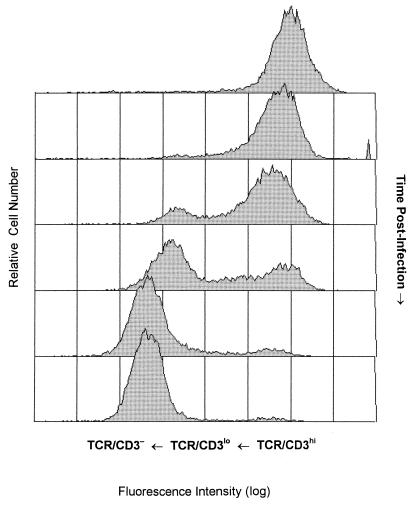

The mean fluorescence values, which reflect receptor surface density, collected sequentially in the kinetic experiments described above, provide an imprecise basis for comparison due to minor variation in the fluorescence intensity between labeling experiments. Therefore, we serially cryopreserved each cell line during the initial year-long infection experiment and determined that when thawed, these cells retained the phenotype that they had on the day that they were frozen. This cell bank enabled us to perform a retrospective, quantitative analysis on a series of sequential samples from each of the infected cell lines. TCR/CD3 surface receptor density was found to progressively decrease p.i. on all of the WE/HIV-2MS (Fig. 2) and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines in a manner similar to that previously described for HIV-1 (83). Initially, following the acute/cytopathic stage of infection, all of the cells are TCR/CD3hi. Shortly thereafter, receptor downregulation from TCR/CD3hi to TCR/CD3lo occurs and is characterized by a decrease in receptor density from 100% to 50% of control values of cells lying outside the region defined by the negative control. The initiation of this decline in receptor surface density was also retarded in the HIV-2-infected cells (15 to 33 weeks p.i.) compared with the HIV-1-infected cells (5 to 15 weeks p.i.), although again variation between isolates of the same virus was observed. Furthermore, the TCR/CD3lo phenotype could be maintained for different lengths of time, with progression to the TCR/CD3− phenotype slower in the WE/HIV-1LAI and WE/HIV-2MVP cell lines than in the WE/HIV-1HXB2 and WE/HIV-2MS cell lines. These kinetic differences in the progressive disruption of TCR/CD3 surface expression found between isolates possibly reflects their relative efficiency at performing specific viral processes, their ability to subvert cellular control mechanisms, or changes in the composition of viral gene products expressed during the course of in vitro infection.

FIG. 2.

Histograms showing the distribution of immunofluorescence from anti-CD3 antibody staining as a function of time p.i. From top to bottom: uninfected WE17/10 cells, and the WE/HIV-2MS cell line at 15, 21, 35, 51, and 60 weeks p.i. TCR/CD3lo cells are identified as cells that fall below the minimum fluorescence intensity defined by the positive control but do not lie within the region defined by the negative control. TCR/CD3hi cells fall within the region defined by mock-infected WE17/10 cells, and TCR/CD3− cells fall within the region designated by the negative control.

TCR/CD3 mRNA expression in HIV-1- and HIV-2-infected cell lines.

RNA was isolated from approximately 5 × 108 cells by the single-step method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (15), followed by oligo(dT)-cellulose selection of poly(A)+ RNA and dotting of 1.0 μg per sample on nitrocellulose membranes. RNA extracted from an ovine kidney cell line (OVK) was used as a negative control. The membranes were hybridized for 16 h under stringent hybridization conditions using the following [α-32P]dCTP-labeled probes (each at 3 × 106 cpm/ml): CD3-γ (pJ; kindly provided by M. J. Crumpton [42]); CD3-δ (pδ; obtained from the American Type Culture Collection [75]); CD3-ζ (kindly provided by A. Weissman [82]); CD3-ɛ (pSRα-ɛ, kindly provided by B. Alcaron [6]); TCR-α and TCR-β (kindly provided by T. Mak [87, 88]); HIV-1 (pBH10 [30]) and HIV-2 (pJSP4-27/H6 [40]), obtained from B. Hahn and G. M. Shaw through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program; and β-actin (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany).

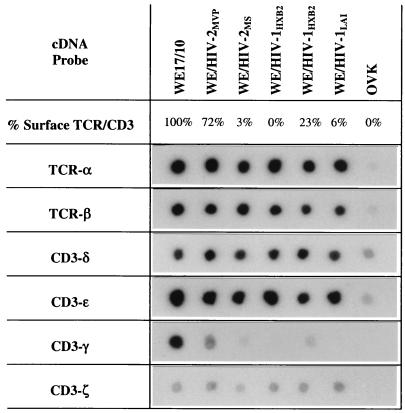

The molecular defect underlying the TCR/CD3− phenotype of HIV-1-infected WE17/10 cells was previously shown, by RNA dot and Northern blot hybridization (84), to result from a specific defect in CD3-γ gene transcripts. In this study, RNA dot blot hybridization was used to verify whether downmodulation of receptor expression on HIV-2-infected WE17/10 cells is also due to the specific loss of CD3-γ gene transcripts. The blots shown in Fig. 3 confirm that the amounts of TCR-α, TCR-β, CD3-δ, CD3-ɛ, and CD3-ζ mRNAs do not change after infection in WE/HIV-1 or WE/HIV-2 cell lines expressing different levels of surface TCR/CD3 complexes. The signals for CD3-γ and CD3-ζ mRNA are weaker than those for the other four chains, reflecting their limiting roles in the expression and signaling of surface complexes (80). However, a consistent signal is detected for CD3-ζ, while the CD3-γ signal progressively decreases in correlation with the percentage of TCR/CD3 surface complexes. Thus, HIV-2 infection is also associated with loss of TCR/CD3 surface expression due to a defect in CD3-γ gene transcripts. Hybridization with a β-actin probe was used to control for the quantity of mRNA in each dot and revealed a slightly lower signal for WE/HIV-2MS (data not shown). The HIV-1 and HIV-2 probes were used to control that each cell line was infected with one of the two viruses only (data not shown). As previously shown for HIV-1-infected cells (83), we demonstrate that TCR/CD3 surface density is progressively decreased in concert with CD3-γ gene transcripts as the HIV-2-infected cell lines transition from TCR/CD3hi to TCR/CD3lo to TCR/CD3−.

FIG. 3.

Expression of messages for TCR-α, TCR-β, CD3-δ, CD3-ɛ, CD3-γ, and CD3-ζ in cells from the mock-infected WE17/10 cell line and the infected WE/HIV-2MVP, WE/HIV-2MS, WE/HIV-1HXB2, and WE/HIV-1LAI cell lines. The filters probed with the TCR-α, TCR-β, CD3-δ, and CD3-ɛ cDNAs were exposed for 5 days; those probed with CD3-γ and CD3-ζ cDNAs were exposed for 14 and 9 days, respectively. The percentage of TCR/CD3+ cells is defined as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

We have provided evidence that HIV-2 infection of the WE17/10 cell line progressively abrogates TCR/CD3 surface expression due to a transcription level defect in the CD3-γ gene similar to that previously described for HIV-1 (83, 84). Subtle changes in TCR/CD3 surface density could explain some of the T-cell-mediated abnormalities observed in HIV-positive individuals, since adequate amounts of functional surface complexes have been shown to be critical for mounting a successful antigen-dependent immune response (73, 74, 76). Impeding CD3-γ gene expression inhibits TCR/CD3 surface expression both in vivo (3, 4, 69) and in vitro (26, 84). In the absence of CD3-γ, tetrameric αβδɛ complexes are formed and only pentameric αβδɛ2 complexes have the conformation required for stable association with CD3-ζ and subsequent processing from the endoplasmic reticulum through the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane (7, 9, 21, 39, 49). Our current knowledge concerning the pivotal roles that both CD3-γ and CD3-ζ play in TCR/CD3 assembly, expression, and function (81) underscores why limiting their expression may potentially be an important mechanism for virus-directed control of the immune response.

Although kinetic differences were observed between isolates of HIV-1 and isolates of HIV-2, in general, the HIV-2 viruses were found to be slower than the HIV-1 viruses to manifest the defect, both during the transition from TCR/CD3hi to TCR/CD3lo and during the transition from TCR/CD3lo to TCR/CD3−. These in vitro data correspond with in vivo data showing that the rate of disease progression is different between these viruses, with disease-free survival time for HIV-2 significantly longer than that for HIV-1 (52). Virus-specific targeting of TCR/CD3 expression has also been observed in human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-infected CD4+ T cells both in vitro (18, 89) and in vivo (53, 67, 72), as well as human herpesvirus 6-infected CD4+ T cells in vitro (47). The basis for the clinical differences between these viruses is unknown and likely depends on both virus and host factors; however, there is increasing evidence that an important mechanism whereby human retroviruses can incapacitate their T-cell host is via specific interference with the TCR/CD3 receptor pathway.

T-cell activation is a critical event in an effective immune response against a pathogen and paradoxically also contributes to the progressive immune dysfunction associated with HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection by inducing factors which these viruses exploit to enhance their own transcription (32, 33, 44, 50, 51, 70). A number of studies have shown that the HIV-1 and HIV-2 LTRs are stimulated by different T-cell activation pathways and therefore have selective controls for virus replication. We asked whether there was a correlation between infection with HIV-1 or HIV-2 and changes in surface expression of the TCR/CD3 complex. We found similar defects in CD3-γ gene transcripts after infection with both viruses, although the rate of receptor loss varied. Thus, our data suggest that the progressive decrease in CD3-γ gene transcripts and surface receptor density after infection of WE17/10 cells results from virus-host cell interactions acting through a mechanism(s) common to HIV-1 and HIV-2.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to P. Kanki, L. Gürler, F. Deinhardt, F. Barré-Sinoussi, B. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, B. Alcaron, M. J. Crumpton, T. Mak, A. Weissman, and the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for efficiently providing various reagents. We thank Renée Martin for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Fonds National de Recherche Scientifique (FNRS; FNRS-SIDA 3.7014.91 and FNRS-Télévie 7.4530.92), the World Health Organization (M8/181/4/5.418), and the Poles for Interuniversity Attraction. R.K. is a Research Director of the FNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson S, Shugars D C, Swanstrom R, Garcia J V. Nef from primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 suppresses surface CD4 expression in human and mouse T cells. J Virol. 1993;67:4923–4931. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4923-4931.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson S J, Lenburg M, Landau N R, Garcia J V. The cytoplasmic domain of CD4 is sufficient for its down-regulation from the cell surface by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef. J Virol. 1994;68:3092–3101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3092-3101.1994. . (Erratum, 68:4705.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaiz-Villena A, Timon M, Corell A, Perez-Aciego P, Martin-Villa J M, Regueiro J R. Brief report: primary immunodeficiency caused by mutations in the gene encoding the CD3-gamma subunit of the T-lymphocyte receptor. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:529–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208203270805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnaiz-Villena A, Timon M, Rodriguez-Gallego C, Iglesias-Casarrubios P, Pacheco A, Regueiro J R. T lymphocyte signalling defects and immunodeficiency due to the lack of CD3 gamma. Immunodeficiency. 1993;4:121–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann J C, Rey F, Nugeyre M T, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, Axler-Blin C, Vezinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, Rozenbaum W, Montagnier L. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumberg R S, Ley S, Sancho J, Lonberg N, Lacy E, McDermott F, Schad V, Greenstein J L, Terhorst C. Structure of the T-cell antigen receptor: evidence for two CD3 epsilon subunits in the T-cell receptor-CD3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7220–7224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonifacino J S, Suzuki C K, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Weissman A M, Klausner R D. Pre-Golgi degradation of newly synthesized T-cell antigen receptor chains: intrinsic sensitivity and the role of subunit assembly. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:73–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer C, Auphan N, Luton F, Malburet J M, Barad M, Bizozzero J P, Reggio H, Schmitt-Verhulst A M. T cell receptor/CD3 complex internalization following activation of a cytolytic T cell clone: evidence for a protein kinase C-independent staurosporine-sensitive step. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1623–1634. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buferne M, Luton F, Letourneur F, Hoeveler A, Couez D, Barad M, Malissen B, Schmitt-Verhulst A M, Boyer C. Role of CD3 delta in surface expression of the TCR/CD3 complex and in activation for killing analyzed with a CD3 delta-negative cytotoxic T lymphocyte variant. J Immunol. 1992;148:657–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantrell D, Davies A A, Londei M, Feldman M, Crumpton M J. Association of phosphorylation of the T3 antigen with immune activation of T lymphocytes. Nature. 1987;325:540–542. doi: 10.1038/325540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantrell D A, Davies A A, Crumpton M J. Activators of protein kinase C down-regulate and phosphorylate the T3/T-cell antigen receptor complex of human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:8158–8162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantrell D A, Friedrich B, Davies A A, Gullberg M, Crumpton M J. Evidence that a kinase distinct from protein kinase C induces CD3 gamma-subunit phosphorylation without a concomitant down-regulation in CD3 antigen expression. J Immunol. 1989;142:1626–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cefai D, Ferrer M, Serpente N, Idziorek T, Dautry-Varsat A, Debre P, Bismuth G. Internalization of HIV glycoprotein gp120 is associated with down-modulation of membrane CD4 and p561ck together with impairment of T cell activation. J Immunol. 1992;149:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen B K, Gandhi R T, Baltimore D. CD4 down-modulation during infection of human T cells with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 involves independent activities of vpu, env, and nef. J Virol. 1996;70:6044–6053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6044-6053.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clavel F, Guetard D, Brun-Vezinet F, Chamaret S, Rey M A, Santos-Ferreira M O, Laurent A G, Dauguet C, Katlama C, Rouzioux C. Isolation of a new human retrovirus from West African patients with AIDS. Science. 1986;233:343–346. doi: 10.1126/science.2425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clerici M, Stocks N I, Zajac R A, Boswell R N, Lucey D R, Via C S, Shearer G M. Detection of three distinct patterns of T helper cell dysfunction in asymptomatic, human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. Independence of CD4+ cell numbers and clinical staging. J Clin Investig. 1989;84:1892–1899. doi: 10.1172/JCI114376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Waal Malefyt R, Yssel H, Spits H, de Vries J E, Sancho J, Terhorst C, Alarcon B. Human T cell leukemia virus type I prevents cell surface expression of the T cell receptor through down-regulation of the CD3-gamma, -delta, -epsilon, and -zeta genes. J Immunol. 1990;145:2297–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich J, Hou X, Wegener A M, Geisler C. CD3 gamma contains a phosphoserine-dependent di-leucine motif involved in down-regulation of the T cell receptor. EMBO J. 1994;13:2156–2166. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich J, Hou X, Wegener A M, Pedersen L O, Odum N, Geisler C. Molecular characterization of the di-leucine-based internalization motif of the T cell receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11441–11448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietrich J, Neisig A, Hou X, Wegener A M, Gajhede M, Geisler C. Role of CD3 gamma in T cell receptor assembly. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:299–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faith A, O’Hehir R E, Malkovsky M, Lamb J R. Analysis of the basis of resistance and susceptibility of CD4+ T cells to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-gp120 induced anergy. Immunology. 1992;76:177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franchini G, Fargnoli K A, Giombini F, Jagodzinski L, De Rossi A, Bosch M, Biberfeld G, Fenyo E M, Albert J, Gallo R C. Molecular and biological characterization of a replication competent human immunodeficiency type 2 (HIV-2) proviral clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2433–2437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallo R C, Sarin P S, Gelmann E P, Robert-Guroff M, Richardson E, Kalyanaraman V S, Mann D, Sidhu G D, Stahl R E, Zolla-Pazner S, Leibowitch J, Popovic M. Isolation of human T-cell leukemia virus in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220:865–867. doi: 10.1126/science.6601823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia J V, Miller A D. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature. 1991;350:508–511. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geisler C. Failure to synthesize the CD3-gamma chain. Consequences for T cell antigen receptor assembly, processing, and expression. J Immunol. 1992;148:2437–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginaldi L, De Martinis M, D’Ostilio A, Di Gennaro A, Marini L, Quaglino D. Altered lymphocyte antigen expressions in HIV infection: a study by quantitative flow cytometry. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:585–592. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/108.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurtler L, Eberle J, Deinhardt F. Abstracts of the Fourth International Conference on AIDS, Stockholm. 1988. Preliminary characterization of an HIV-2 isolate derived from a German virus carrier, abstr. 1662. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guyader M, Emerman M, Sonigo P, Clavel F, Montagnier L, Alizon M. Genome organization and transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Nature. 1987;326:662–669. doi: 10.1038/326662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Arya S K, Popovic M, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Molecular cloning and characterization of the HTLV-III virus associated with AIDS. Nature. 1984;312:166–169. doi: 10.1038/312166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haks M C, Krimpenfort P, Borst J, Kruisbeek A M. The CD3γ chain is essential for development of both the TCRαβ and TCRγδ lineages. EMBO J. 1998;17:1871–1882. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannibal M C, Markovitz D M, Clark N, Nabel G J. Differential activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 transcription by specific T-cell activation signals. J Virol. 1993;67:5035–5040. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5035-5040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannibal M C, Markovitz D M, Nabel G J. Multiple cis-acting elements in the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 enhancer mediate the response to T-cell receptor stimulation by antigen in a T-cell hybridoma line. Blood. 1994;83:1839–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofmann B, Jakobsen K D, Odum N, Dickmeiss E, Platz P, Ryder L P, Pedersen C, Mathiesen L, Bygbjerg I B, Faber V. HIV-induced immunodeficiency. Relatively preserved phytohemagglutinin as opposed to decreased pokeweed mitogen responses may be due to possibly preserved responses via CD2/phytohemagglutinin pathway. J Immunol. 1989;142:1874–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iafrate A J, Bronson S, Skowronski J. Separable functions of Nef disrupt two aspects of T cell receptor machinery: CD4 expression and CD3 signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:673–684. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irving B A, Chan A C, Weiss A. Functional characterization of a signal transducing motif present in the T cell antigen receptor zeta chain. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1093–1103. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanki P, Barin F, Essex M. Abstracts of the Fourth International Conference on AIDS, Stockholm. 1988. Antibody reactivity to multiple HIV-2 isolates, abstr. 1659. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanki P J, Barin F, M’Boup S, Allan J S, Romet-Lemonne J L, Marlink R, McLane M F, Lee T H, Arbeille B, Denis F. New human T-lymphotropic retrovirus related to simian T-lymphotropic virus type III (STLV-IIIAGM) Science. 1986;232:238–243. doi: 10.1126/science.3006256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kearse K P, Roberts J L, Singer A. TCR alpha-CD3 delta epsilon association is the initial step in alpha beta dimer formation in murine T cells and is limiting in immature CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes. Immunity. 1995;2:391–399. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kong L I, Lee S W, Kappes J C, Parkin J S, Decker D, Hoxie J A, Hahn B H, Shaw G M. West African HIV-2-related human retrovirus with attenuated cytopathicity. Science. 1988;240:1525–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.3375832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krangel M S. Endocytosis and recycling of the T3-T cell receptor complex. The role of T3 phosphorylation. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1141–1159. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.4.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krissansen G W, Owen M J, Verbi W, Crumpton M J. Primary structure of the T3 gamma subunit of the T3/T cell antigen receptor complex deduced from cDNA sequences: evolution of the T3 gamma and delta subunits. EMBO J. 1986;5:1799–1808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lane H C, Depper J M, Greene W C, Whalen G, Waldmann T A, Fauci A S. Qualitative analysis of immune function in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Evidence for a selective defect in soluble antigen recognition. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:79–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507113130204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leiden J M, Wang C Y, Petryniak B, Markovitz D M, Nabel G J, Thompson C B. A novel Ets-related transcription factor, Elf-1, binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 2 regulatory elements that are required for inducible trans activation in T cells. J Virol. 1992;66:5890–5897. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.5890-5897.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liegler T J, Stites D P. HIV-1 gp120 and anti-gp120 induce reversible unresponsiveness in peripheral CD4 T lymphocytes. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luria S, Chambers I, Berg P. Expression of the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus Nef protein in T cells prevents antigen receptor-mediated induction of interleukin 2 mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5326–5330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lusso P, Malnati M, De Maria A, Balotta C, DeRocco S E, Markham P D, Gallo R C. Productive infection of CD4+ and CD8+ mature human T cell populations and clones by human herpesvirus 6. Transcriptional down-regulation of CD3. J Immunol. 1991;147:685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luton F, Buferne M, Legendre V, Chauvet E, Boyer C, Schmitt-Verhulst A M. Role of CD3γ and CD3δ cytoplasmic domains in cytolytic T lymphocyte functions and TCR/CD3 down-modulation. J Immunol. 1997;158:4162–4170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manolios N, Kemp O, Li Z G. The T cell antigen receptor alpha and beta chains interact via distinct regions with CD3 chains. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:84–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markovitz D M, Hannibal M, Perez V L, Gauntt C, Folks T M, Nabel G J. Differential regulation of human immunodeficiency viruses (HIVs): a specific regulatory element in HIV-2 responds to stimulation of the T-cell antigen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9098–9102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Markovitz D M, Smith M J, Hilfinger J, Hannibal M C, Petryniak B, Nabel G J. Activation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 enhancer is dependent on purine box and κB regulatory elements. J Virol. 1992;66:5479–5484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5479-5484.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marlink R, Kanki P, Thior I, Travers K, Eisen G, Siby T, Traore I, Hsieh C C, Dia M C, Gueye E H. Reduced rate of disease development after HIV-2 infection as compared to HIV-1. Science. 1994;265:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.7915856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuoka M, Hattori T, Chosa T, Tsuda H, Kuwata S, Yoshida M, Uchiyama T, Takatsuki K. T3 surface molecules on adult T cell leukemia cells are modulated in vivo. Blood. 1986;67:1070–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyaard L, Otto S A, Schuitemaker H, Miedema F. Effects of HIV-1 Tat protein on human T cell proliferation. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2729–2732. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miedema F, Petit A J, Terpstra F G, Schattenkerk J K, De Wolf F, Al B J, Roos M, Lange J M, Danner S A, Goudsmit J. Immunological abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected asymptomatic homosexual men. HIV affects the immune system before CD4+ T helper cell depletion occurs. J Clin Investig. 1988;82:1908–1914. doi: 10.1172/JCI113809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morio T, Chatila T, Geha R S. HIV glycoprotein gp120 inhibits TCR-CD3-mediated activation of fyn and lck. Int Immunol. 1997;9:53–64. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ono S, Ohno H, Saito T. Rapid turnover of the CD3 zeta chain independent of the TCR-CD3 complex in normal T cells. Immunity. 1995;2:639–644. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romeo C, Amiot M, Seed B. Sequence requirements for induction of cytolysis by the T cell antigen/Fc receptor zeta chain. Cell. 1992;68:889–897. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samelson L E, Phillips A F, Luong E T, Klausner R D. Association of the fyn protein-tyrosine kinase with the T-cell antigen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4358–4362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwartz O, Alizon M, Heard J M, Danos O. Impairment of T cell receptor-dependent stimulation in CD4+ lymphocytes after contact with membrane-bound HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Virology. 1994;198:360–365. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaw G M, Hahn B H, Arya S K, Groopman J E, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Molecular characterization of human T-cell leukemia (lymphotropic) virus type III in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Science. 1984;226:1165–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.6095449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shearer G M, Bernstein D C, Tung K S, Via C S, Redfield R, Salahuddin S Z, Gallo R C. A model for the selective loss of major histocompatibility complex self-restricted T cell immune responses during the development of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) J Immunol. 1986;137:2514–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skowronski J, Parks D, Mariani R. Altered T cell activation and development in transgenic mice expressing the HIV-1 nef gene. EMBO J. 1993;12:703–713. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stefanova I, Saville M W, Peters C, Cleghorn F R, Schwartz D, Venzon D J, Weinhold K J, Jack N, Bartholomew C, Blattner W A, Yarchoan R, Bolen J B, Horak I D. HIV infection-induced posttranslational modification of T cell signaling molecules associated with disease progression. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:1290–1297. doi: 10.1172/JCI118915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strebel K, Klimkait T, Martin M A. A novel gene of HIV-1, vpu, and its 16-kilodalton product. Science. 1988;241:1221–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.3261888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Subramanyam M, Gutheil W G, Bachovchin W W, Huber B T. Mechanism of HIV-1 Tat induced inhibition of antigen-specific T cell responsiveness. J Immunol. 1993;150:2544–2553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Suzushima H, Hattori T, Asou N, Wang J X, Nishikawa K, Okubo T, Anderson P, Takatsuki K. Discordant gene and surface expression of the T-cell receptor/CD3 complex in adult T-cell leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6084–6088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tani Y, Tian H, Lane H C, Cohen D I. Normal T cell receptor-mediated signaling in T cell lines stably expressing HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Immunol. 1993;151:7337–7348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Timon M, Arnaiz-Villena A, Rodriguez-Gallego C, Perez-Aciego P, Pacheco A, Regueiro J R. Selective disbalances of peripheral blood T lymphocyte subsets in human CD3 gamma deficiency. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1440–1444. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tong-Starksen S E, Welsh T M, Peterlin B M. Differences in transcriptional enhancers of HIV-1 and HIV-2. Response to T cell activation signals. J Immunol. 1990;145:4348–4354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trimble L A, Lieberman J. Circulating CD8 T lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals have impaired function and downmodulate CD3 zeta, the signaling chain of the T-cell receptor complex. Blood. 1998;91:585–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tsuda H, Takatsuki K. Specific decrease in T3 antigen density in adult T-cell leukaemia cells. I. Flow microfluorometric analysis. Br J Cancer. 1984;50:843–845. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Valitutti S, Muller S, Cella M, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide-MHC complexes. Nature. 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Valitutti S, Muller S, Dessing M, Lanzavecchia A. Different responses are elicited in cytotoxic T lymphocytes by different levels of T cell receptor occupancy. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1917–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van den Elsen P, Shepley B A, Cho M, Terhorst C. Isolation and characterization of a cDNA clone encoding the murine homologue of the human 20K T3/T-cell receptor glycoprotein. Nature. 1985;314:542–544. doi: 10.1038/314542a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Viscidi R P, Mayur K, Lederman H M, Frankel A D. Inhibition of antigen-induced lymphocyte proliferation by Tat protein from HIV-1. Science. 1989;246:1606–1608. doi: 10.1126/science.2556795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian J P, Henry M, Chenciner N, Cheynier R, Delassus S, Martins L P, Sala M, Nugeyre M T, Guetard D. LAV revisited: origins of the early HIV-1 isolates from Institut Pasteur. Science. 1991;252:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.2035026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wegener A M, Hou X, Dietrich J, Geisler C. Distinct domains of the CD3-gamma chain are involved in surface expression and function of the T cell antigen receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4675–4680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wegener A M, Letourneur F, Hoeveler A, Brocker T, Luton F, Malissen B. The T cell receptor/CD3 complex is composed of at least two autonomous transduction modules. Cell. 1992;68:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90208-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weissman A M. The T-cell antigen receptor: a multisubunit signaling complex. Chem Immunol. 1994;59:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weissman A M, Hou D, Orloff D G, Modi W S, Seuanez H, O’Brien S J, Klausner R D. Molecular cloning and chromosomal localization of the human T-cell receptor zeta chain: distinction from the molecular CD3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9709–9713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Willard-Gallo K E, Delmelle-Wibaut C, Segura-Zapata I, Janssens M, Willems L, Kettmann R. Modulation of CD3-gamma gene expression after HIV type 1 infection of the WE17/10 T cell line is progressive and occurs in concert with decreased production of viral p24 antigen. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:715–725. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Willard-Gallo K E, Van de Keere F, Kettmann R. A specific defect in CD3 gamma-chain gene transcription results in loss of T-cell receptor/CD3 expression late after human immunodeficiency virus infection of a CD4+ T-cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6713–6717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Willey R L, Maldarelli F, Martin M A, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein induces rapid degradation of CD4. J Virol. 1992;66:7193–7200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7193-7200.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Willey R L, Maldarelli F, Martin M A, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein regulates the formation of intracellular gp160-CD4 complexes. J Virol. 1992;66:226–234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.226-234.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yanagi Y, Chan A, Chin B, Minden M, Mak T W. Analysis of cDNA clones specific for human T cells and the alpha and beta chains of the T-cell receptor heterodimer from a human T-cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3430–3434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoshikai Y, Anatoniou D, Clark S P, Yanagi Y, Sangster R, Van den Elsen P, Terhorst C, Mak T W. Sequence and expression of transcripts of the human T-cell receptor beta-chain genes. Nature. 1984;312:521–524. doi: 10.1038/312521a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yssel H, de Waal Malefyt R, Duc Dodon M D, Blanchard D, Gazzolo L, de Vries J E, Spits H. Human T cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type I infection of a CD4+ proliferative/cytotoxic T cell clone progresses in at least two distinct phases based on changes in function and phenotype of the infected cells. J Immunol. 1989;142:2279–2289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zagury J F, Franchini G, Reitz M, Collalti E, Starcich B, Hall L, Fargnoli K, Jagodzinski L, Guo H G, Laure F. Genetic variability between isolates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2 is comparable to the variability among HIV type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5941–5945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]