Abstract

We derive approximate expressions for pre- and post-steady state regimes of the velocity-substrate-inhibitor spaces of the Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetic scheme with fully and partial competitive inhibition. Our refinement over the currently available standard quasi steady state approximation (sQSSA) seems to be valid over wide range of enzyme to substrate and enzyme to inhibitor concentration ratios. Further, we show that the enzyme-inhibitor-substrate system can exhibit temporally well-separated two different steady states with respect to both enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes under certain conditions. We define the ratios fS = vmax/(KMS + e0) and fI = umax/(KMI + e0) as the acceleration factors with respect to the catalytic conversion of substrate and inhibitor into their respective products. Here KMS and KMI are the Michaelis-Menten parameters associated respectively with the binding of substrate and inhibitor with the enzyme, vmax and umax are the respective maximum reaction velocities and e0, s0, and i0 are total enzyme, substrate and inhibitor levels. When (fS/fI) < 1, then enzyme-substrate complex will show multiple steady states and it reaches the full-fledged steady state only after the depletion of enzyme-inhibitor complex. When (fS/fI) > 1, then the enzyme-inhibitor complex will show multiple steady states and it reaches the full-fledged steady state only after the depletion of enzyme-substrate complex. This multi steady-state behavior especially when (fS/fI) ≠ 1 is the root cause of large amount of error in the estimation of various kinetic parameters of fully and partial competitive inhibition schemes using sQSSA. Remarkably, we show that our refined expressions for the reaction velocities over enzyme-substrate-inhibitor space can control this error more significantly than the currently available sQSSA expressions.

1. Introduction

Enzymes catalyze various reactions of biochemical pathways [1–4]. The Michaelis-Menten (MM) kinetics [5,6] is the fundamental mechanistic description of the biological catalysis of enzyme reactions [3,7–9]. In this kinetics scheme, the enzyme reversibly binds its substrate to form the enzyme-substrate complex which subsequently decomposes into free enzyme and product of the substrate. Integral solution to the rate equations associated with the Michaelis-Menten scheme (MMS) is not expressible in terms of elementary functions. Several analytical methods were tried to obtain the approximate solution of MMS in terms of ordinary [10] and singular perturbation series [11–13] and perturbation expansions over slow manifolds [14,15]. In general, the singular perturbation expansions yield a combination of inner and outer solutions which were then combined via proper matching at the boundary layer [11,16–21].

Several steady state approximations were proposed in the light of experimental characterization of a single substrate MM enzyme. The standard quasi steady state approximation (sQSSA) is widely used across several fields of biochemical research to obtain the enzyme kinetic parameters such as vmax and KM from the experimental datasets on reaction velocity versus initial substrate concentrations. This approximation works well when the product formation step is rate-limiting apart from the condition that the substrate concentration is much higher than the enzyme concentration. In general, sQSSA yields expressions which can be directly used by the experimentalists to obtain various enzyme kinetic parameters [22]. Recently, explicit closed form expressions of the integrated rate equation corresponding to sQSSA were obtained in terms of Lambert’s W functions [23–27]. The total QSSA (tQSSA) assumes that the amount of product formed near the steady state is much negligible compared to the total substrate concentration [28,29]. The reverse QSSA (rQSSA) works very well [30,31] when the substrate concentration is much lesser than the enzyme concentration.

Several linearization techniques such as Lineweaver-Burk representation were also proposed [32,33] to obtain the kinetic parameters from the experimental data. Although sQSSA, rQSSA and tQSSA methods work well under in vitro conditions, there are several situations such as single molecule enzyme kinetics [34] and other in vivo experimental conditions where one cannot manipulate the ratio of substrate to enzyme concentrations much. Recent studies on the liver cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme revealed that tQSSA based methods work very well irrespective of the relative values of KM and the total enzyme concentration [35,36]. It seems that one can accurately obtain the enzyme kinetic parameters using tQSSA based equations [37]. Further, successfulness of various QSSAs in accurately obtaining the kinetic parameters is strongly dependent on the timescale separation between the pre- and post-steady state regimes of MMS [38,39]. Particularly, when the timescale separation between pre- and post-steady states of MMS is high enough, then the sQSSA along with stationary reactant assumption where one replaces the unknown steady state substrate concentration with the total substrate concentration [27] can be used to directly obtain the kinetic parameters.

The catalytic properties of an enzyme can be manipulated by an inhibitor. Inhibitors can be competitive or allosteric in nature [2]. Competitive inhibitors (Fig 1) are substrate like molecules which reversibly bind the active site of the same enzyme and hence block further binding of substrate. This in turn deceases the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme over its natural substrate. In a fully competitive inhibition (Scheme A in Fig 1), the inhibitor competes with the substrate to bind the active site of the enzyme and subsequently gets converted into the respective product. In this case, both substrate and inhibitor will be converted into their respective products by the same enzyme. In case of partial competitive inhibition (Scheme B in Fig 1), the reversibly formed enzyme-inhibitor complex will be a dead-end one. Several drugs have been designed to strongly inhibit the pathogenic or metabolic enzymes. Understanding the dynamical behavior of the fully and partial competitive inhibition of MM enzymes is critical to understand the pharmacokinetic and efficiency aspects of such enzyme inhibiting drugs. Variation of vmax and KM of the enzyme with respect to the concentration of an inhibitor decides the efficiency of a given drug molecule in targeting that enzyme. In steady state experiments on the single substrate enzymes, the total substrate concentration will be iterated to obtain the respective substrate conversion velocities. This substrate concentration versus reaction velocity dataset will be then used to obtain the kinetic parameters such as KM and vmax. To obtain the kinetic parameters related to the enzyme inhibition, one needs to conduct a series of velocity versus substrate type steady state experiments at different concentrations of inhibitor. Using this dataset on the steady state substrate, inhibitor versus reaction velocities, one can obtain the kinetic parameters related to the enzyme-substrate-inhibitor system. The enzyme kinetic rate constants can also be directly obtained by non-linear least square fitting of the time dependent progress curve data over the corresponding differential rate equations using the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm. However, the propagated error levels will be high upon the computation of KM and vmax from these individual rate constants obtained from the nonlinear least square fitting procedures [40].

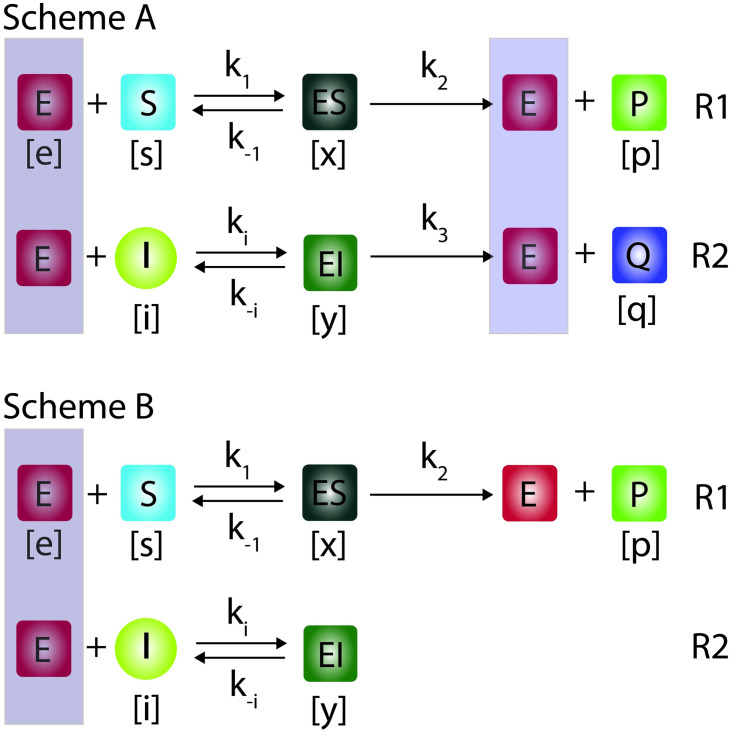

Fig 1. Fully (Scheme A) and partial (Scheme B) competitive inhibition schemes of Michaelis-Menten type enzyme kinetics.

In fully competitive inhibition, both substrate (S) and inhibitor (I) compete for the same active site of enzyme (E) to bind and form reversible complexes (ES, EI) which subsequently get converted into their respective products (P, Q). Whereas, in partial competitive inhibition, the reversibly formed enzyme-inhibitor (EI) is a dead-end complex. Here (e, s, i, x, y, p, q) are respectively the concentrations of enzyme, substrate, inhibitor, enzyme-substrate, enzyme-inhibitor, product of substrate and product of inhibitor. Further, k1 and ki are the respective forward rate constants, k-1 and k-i are the reverse rate constants and, k2 and k3 are the respective product formation rates.

The successfulness of various steady state approximations in obtaining the kinetic parameters of enzymes from the experimental datasets strongly depends on the occurrence of a common steady state with respect to both substrate and inhibitor binding dynamics in both fully and partial competitive inhibition schemes. Mismatch in the steady state timescales can be resolved by setting higher substrate and inhibitor concentrations than the enzyme concentration. This condition drives the steady state reaction velocities as well as the timescales corresponding to the binding of substrate and inhibitor with the same enzyme close to zero. However, under in vivo conditions, one cannot manipulate the relative concentrations of substrate, inhibitor and enzyme much. All the quasi steady state type approximations will fail when the concentration of the enzyme is comparable with that of the substrate and inhibitor which is generally true under in vivo conditions. In this article, we will address this issue in detail and derive accurate expressions for the steady state reaction velocities when the concentrations of enzyme, substrate and inhibitor are comparable with each other.

2. Theory

The competitive inhibition of Michaelis-Menten enzymes can be via fully or partial mode as depicted in Scheme A and B of Fig 1. In fully competitive inhibition given in Scheme A, both the substrate and inhibitor molecules compete for the same active site of the target enzyme for binding and subsequently get converted into their respective products in a parallel manner. In case of partial competitive inhibition, the reversibly formed enzyme-inhibitor complex will not be converted into any product and it will be a dead-end complex. Particularly, several drug molecules are partial competitive inhibitors [41,42]. Fully competitive inhibition plays important roles in the regulation of metabolic reaction pathways. In the following sections we will analyze various kinetic aspects of fully and partial competitive inhibition schemes in detail. We use the equation numbering as the section number followed by the respective equation number within that section e.g., in the notation Eq. x.y.z.k, x.y.z is the section number and k is the equation number in that section.

2.1. Fully competitive inhibition

The fully competitive inhibition of Michaelis-Menten enzymes as depicted in Scheme A of Fig 1 can be quantitatively described by the following set of differential rate equations.

| [2.1.1] |

| [2.1.2] |

| [2.1.3] |

| [2.1.4] |

| [2.1.5] |

Here . In Eqs 2.1.1–2.1.5, (s, i, e, x, y, p, q) are respectively the concentrations (mol/lit, M) of substrate, inhibitor, enzyme, enzyme-substrate complex, enzyme-inhibitor complex, product of substrate and product of inhibitor. Here k1 and ki are the respective forward bimolecular rate constants (1/M/second), k-1 and k-i (1/second) are the respective reverse unimolecular rate constants, u and v (M/second) are the respective reaction velocities and, k2 and k3 (1/second) are the respective unimolecular product formation rate constants along with the mass conservation laws: e = e0 − x − y; s = s0 − x − p; i = i0 − y − q. The initial conditions are (s, i, e, x, y, p, q, v, u) = (s0, i0, e0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0) at t = 0. When t → ∞, then the reaction ends at (s, i, e, x, y, p, q, v, u) = (0, 0, e0, 0, 0, s0, i0, 0, 0). The steady states occur when especially under the condition that t < ∞ since when t → ∞. However, the timescale 0 < tCS < ∞ at which can be different from the timescale 0 < tCI < ∞ at which . When there is a mismatch in the steady state timescales i.e., (tCS ≠ tCI), then one cannot obtain a common steady state solution to Eqs 2.1.1–2.1.5 by simultaneously equating all of them to zero. This means that there exist two different steady states with respect to enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes at two different time points along with four different timescales viz. two different pre-steady state timescales and two different post-steady state timescales. Various definitions and symbols used in the theory section are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of variables and parameters used in the theory section.

| Parameters / Variables | Definition | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| e, s, i, p, q, x, y, v, u | Concentration of enzyme, substrate, inhibitor, product of substrate, product of inhibitor, enzyme-substrate complex, enzyme-inhibitor complex, velocity of substrate-product formation, velocity of inhibitor-product formation. | mol/lit, M |

| e0, s0, i0 | Initial enzyme, substrate and inhibitor concentrations. | M |

| E, S, I, P, Q, X, Y, V, U | are the normalized concentrations of substrate, enzyme, product of substrate, enzyme-inhibitor complex, enzyme-substrate complex, inhibitor and product of inhibitor, velocity of product of substrate formation, and velocity of product of inhibitor formation. | dimensionless |

| EC, SC, IC, PC, QC, XC, YC, VC, UC | Overll steady state values with respect to both X as well as Y. | dimensionless |

| SCP, ICP, PCP, QCP, XCP, YCP, VCP, UCP | Values at the steady state with respect to only X. | dimensionless |

| SCQ, ICQ, PCQ, QCQ, XCQ, YCQ, VCQ, UCQ | Values at the steady state with respect to only Y. | dimensionless |

| k2, k3 | Unimolecular product formation rate constants. | 1/second |

| τ | = k 2 t | dimensionless |

| vmax, umax | vmax = k2 e0, umax = k3 e0 | M/second |

| k1, ki | Bimolecular rate constants associated with the binding of substrate and inhibitor respectively with the same enzyme. | 1 / (M second) |

| k-1, k-i | Dissociation rate constants associated with the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes. | 1/second |

| KRS, KRI | KRS = k2 / k1, KRI = k3 / ki | M |

| KDS, KDI | KDS = k-1 / k1, KDI = k-i / ki | M |

| KMS, KMI | KMS = KRS + KDS, KMI = KRI + KDI | M |

| ηS, ηI | ηS = k2 / k1 s0, ηI = k3 / ki i0 | dimensionless |

| εS, εI, εIS | εS = e0 / s0, εI = e0 / i0, εIS = εI / εS = s0 / i0 | dimensionless |

| κS, κI | κS = k-1 / k1s0, κI = k-i / ki i0 | dimensionless |

| χ I | = k2/kii0 defined for the partial competitive inhibition scheme. | dimensionless |

| ρ | = k3 / k2 = umax / vmax | dimensionless |

| σ | = k1 / ki | dimensionless |

| μS, μI | μS = ηS + κS, μI = ηI + κI | dimensionless |

| ϒ | = k-1 / k-i | dimensionless |

| δ | dimensionless | |

| = εI + κI + ηI = εI + μI | dimensionless | |

| = εS + κS + ηS = εS + μS | dimensionless | |

| = εI + κI | dimensionless | |

| αS | = 1 + εS + κS + ηS | dimensionless |

| αI | = 1 + εI + κI + ηI | dimensionless |

| βI | = 1 + εI + κI | dimensionless |

| ϕ S | = ηSεS | dimensionless |

| ϕ I | = ηIεI | dimensionless |

| τ CS |

, steady state timescale corresponding to the enzyme-substrate complex (fully competitive). , steady state timescale corresponding to the enzyme-substrate complex (partial competitive). |

dimensionless Eq 2.6.1.1. |

| τ CI | , steady state timescale corresponding to the enzyme-inhibitor complex (fully competitive) | dimensionless Eq 2.6.1.1. |

| τ CY | , (pesudo) steady state timescale corresponding to enzyme-inhibitor complex (partial competitive). | Dimensionless Eq 2.9.3.2. |

| fS, fI |

are the reaction acceleration factors associated with the conversion of substrate and inhibitor into their products. δ = fS/fI. |

M/second. |

2.2. Scaling and non-dimensionalization

To simplify the system of Eqs 2.1.1–2.1.5, we introduce the following set of scaling transformations.

| [2.2.1] |

We further define the following parameters.

| [2.2.2] |

| [2.2.3] |

| [2.2.4] |

| [2.2.5] |

| [2.2.6] |

Here (S, I, E, X, Y, P, Q) ∈ [0, 1] are the dimensionless time dependent dynamical variables along with the mass conservation laws: E = 1 − X − Y; S = 1 − εSX − P; I = 1 − εIY − Q. With these scaling transformations, one can reduce Eqs 2.1.1–2.1.5 into the following set of equations.

| [2.2.7] |

| [2.2.8] |

| [2.2.9] |

Upon expanding S and I with their definition in the right-hand side of Eqs 2.2.7 and 2.2.8 and rearranging the linear and nonlinear terms, we arrive at the following form.

| [2.2.10] |

| [2.2.11] |

Here αS and αI are defined as in Eq 2.2.6. The coupled first order nonlinear ODEs given in Eqs 2.2.9–2.2.11 completely characterize the dynamics of fully competitive inhibition scheme over (P, Q, X, Y, τ) space. Here the initial conditions are (S, I, E, X, Y, P, Q, V, U) = (1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0) at τ = 0. When τ → ∞, then the reaction trajectory ends at (S, I, E, X, Y, P, Q, V, U) = (0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0). The steady state with respect to X occurs at 0 < τCS < ∞ where . Since S and P monotonically varying functions of τ one finds that throughout the reaction timescale except at τ → 0 where and at τ → ∞ where , one implicitly finds at the steady state that . Using the same arguments, one can show that at the steady state with respect to Y at 0 < τCI < ∞. Since I and Q are monotonically varying functions of τ one finds that throughout the entire timescale regime except at τ = 0 where and at τ → ∞ where . Here (τCS, τCI) = k2(tCS, tCI). When τCS = τCI = τC, then we represent the common steady state values of the dynamical variables as (SC, IC, EC, XC, YC, PC, QC, VC, UC).

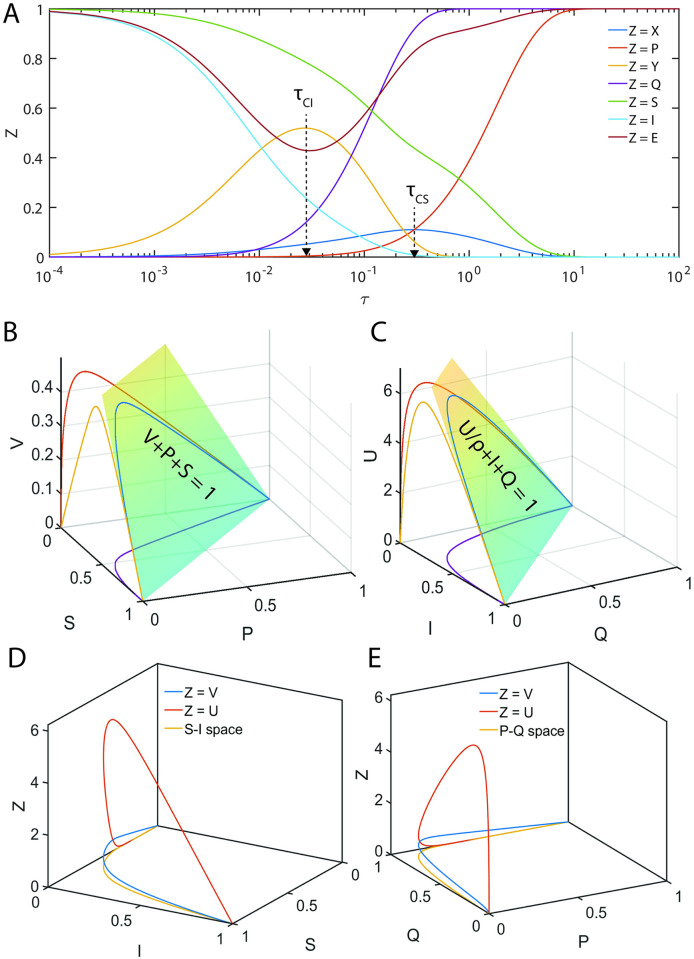

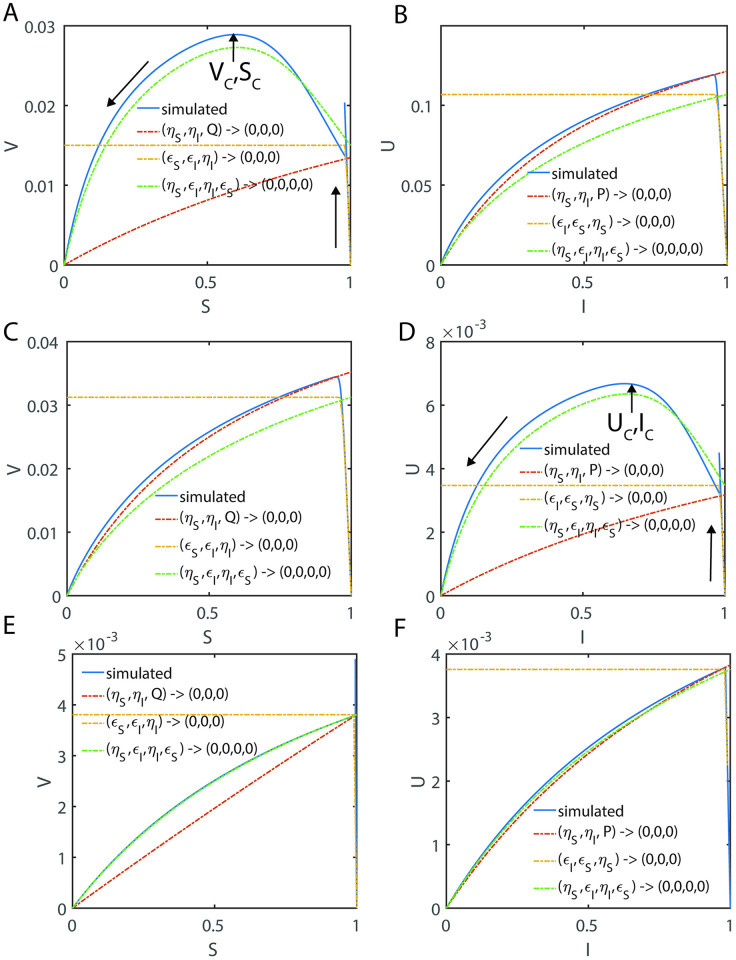

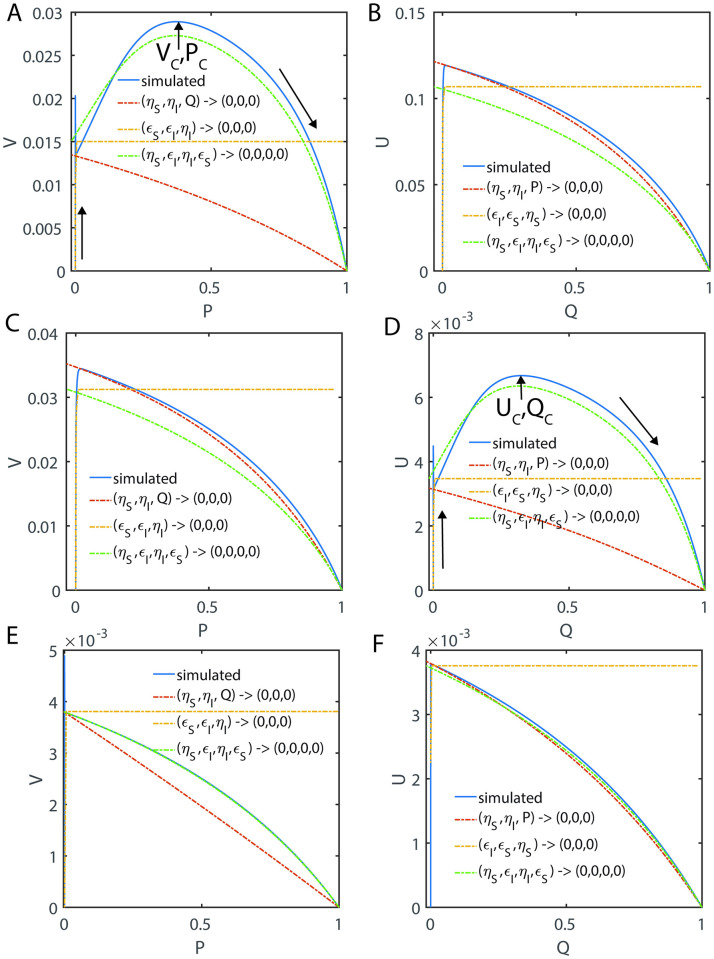

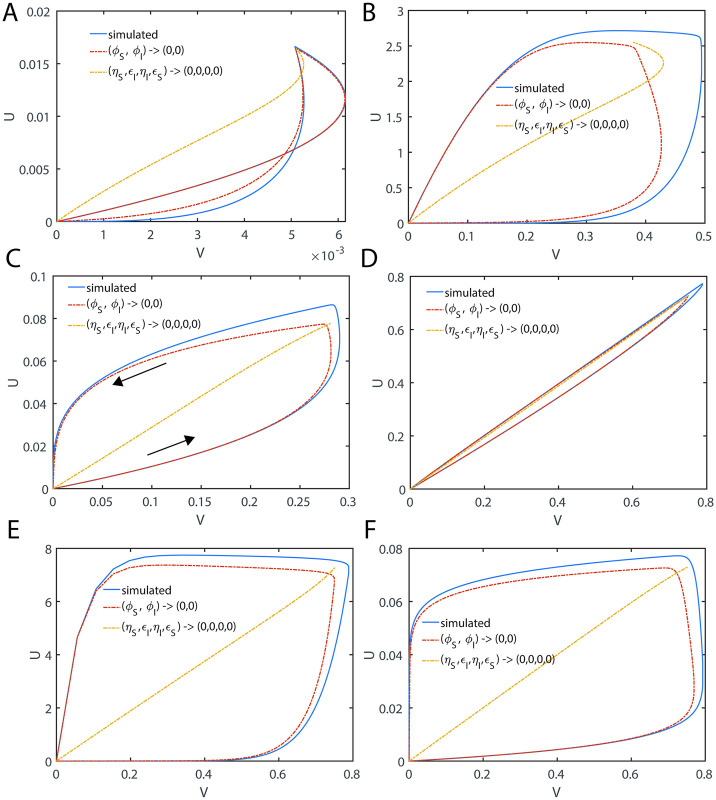

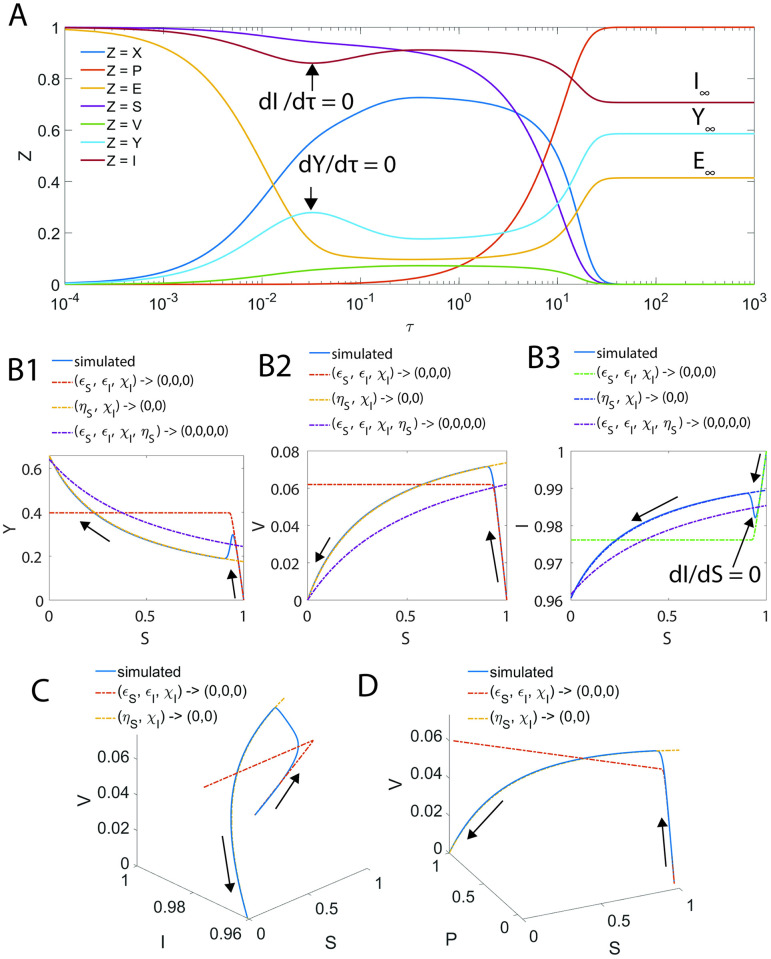

In Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9, V and U are the dimensionless reaction velocities associated with the substrate and inhibitor conversions into their respective products (P, Q) and the mass conservation laws can be rewritten in the dimensionless velocity-substrate-product spaces as . Further, the transformation rules for the reaction velocities (V, U) are and . Numerically integrated sample trajectories of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 are shown in Fig 2A–2E. Clearly, all the reaction trajectories in the (V, P, S) space fall on the plane V + P + S = 1, and all the reaction trajectories in the (U, Q, I) space fall on the plane as demonstrated in Fig 2B and 2C. Parameters associated with the nonlinear system of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 as defined in Eqs 2.2.2–2.2.6 can be grouped into ordinary and singular ones. Here (εS, κS, εI, κI) are the ordinary perturbation parameters. Further, (ηS, ηI, ρ) are the singular perturbation parameters since they multiply or divide the highest derivative terms. Particularly, (ηS, ηI) decide how fast the system of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 attains the steady state, (κS, κI) decide how fast the enzyme-substrate / inhibitor complexes dissociate and (μS, μI) are the dimensionless Michaelis-Menten type constants which describe the summary of the effects of (ηS, κS, ηI, κI). The relative fastness of the conversion of substrate and inhibitor into their respective products as given in Scheme A of Fig 1 can be characterized by the following critical ratios of the reactions rates.

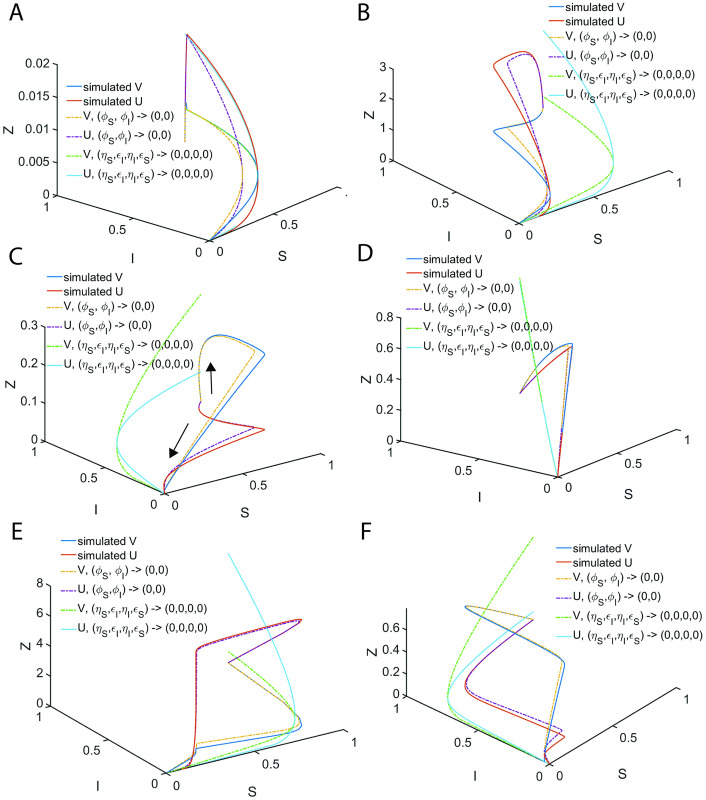

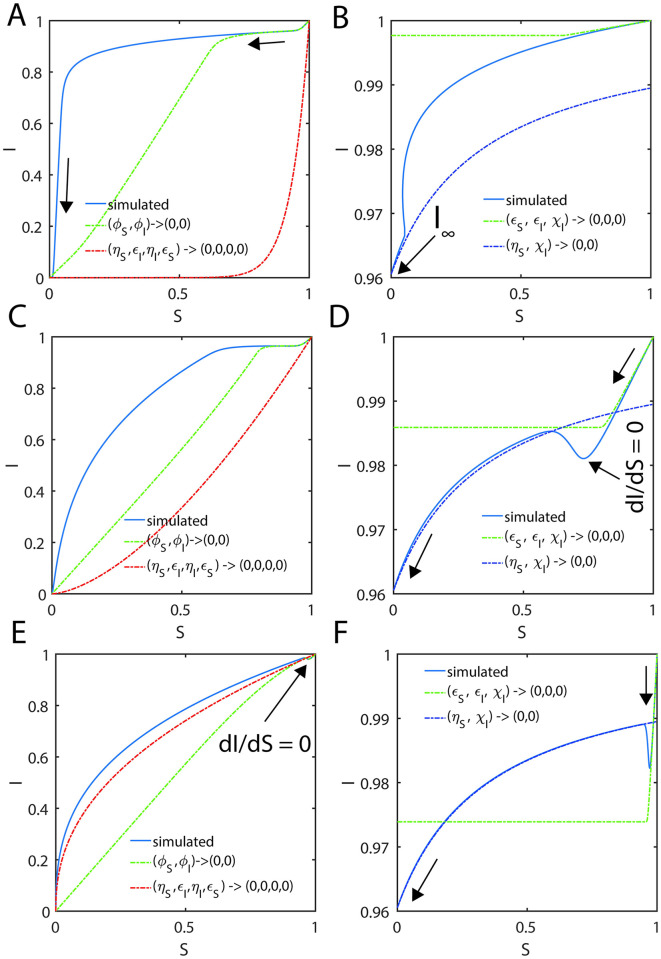

Fig 2. Occurrence of distinct steady state timescales with respect to enzyme-substrate (X) and enzyme-inhibitor (Y) complexes.

Here (S, I, E, X, Y, P, Q) are the dimensionless concentrations of substrate, inhibitor, enzyme, enzyme-substrate, enzyme-inhibitor, product of substrate and product of inhibitor. Trajectories are from numerical integration of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 with the parameters ηS = 0.2, εS = 4.1, κS = 3.1, ρ = 10, ηI = 0.1, εI = 1.2, κI = 0.1 along with the initial conditions (S, I, E, X, Y, P, Q) = (1,1,1,0,0,0,0) at τ = 0. Further, upon fixing ρ, one finds that δ = 0.05, γ = 1.55 and σ = 0.17. Here V = εSX and U = ρεIY are the dimensionless reaction velocities corresponding to the conversion of the substrate and inhibitor into their respective products P and Q. A. The steady states corresponding to the enzyme-inhibitor and enzyme-substrate complexes occur at τCI = 0.03, τCS = 0.31 respectively. We should note that τCI is the time at which and τCS is the time at which . Since τCS ≠ τCI with the current parameter settings, one cannot obtain a common steady state solution to Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9. B. All the trajectories in the velocity-substrate-product (VPS) space fall within the plane V + P + S = 1. C. All the trajectories in the velocity-inhibitor-product (UQI) space fall within the plane U/ρ + Q + I = 1. D. Sample trajectories in the velocities-inhibitor-substrate (VIS, UIS) and velocities-products spaces (U, P, Q) and (V, P, Q).

| [2.2.12] |

When (σ, γ, ρ) = (1,1,1), then the dynamical aspects of the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes will be similar. Here one should note that the parameters (ηS, ηI, εS, εI, ρ, σ) are connected via so that one finds the connection . Similarly, the set of parameters (κS, κI, εS, εI, γ, σ) are connected via so that . In general, the parameters (σ, γ ρ) are connected as follows.

| [2.2.13] |

When the parameters (ηS, ηI, εS, εI, κS, κI) are varied independently, then fixing one parameter in (σ, γ, ρ) eventually fixes the other two parameters. For example, when we fix σ = σf then the corresponding and . The fully competitive enzyme kinetics scheme can exhibit a complex behavior depending on the relative values of the parameters (σ, γ, ρ).

2.3. Variable transformations

Using the substitutions and noting that V = εSX and U = ρεIY, the system of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 can be reduced to the following set of coupled nonlinear second order ODEs in the (P, Q, τ) and first order ODEs in the (V, P, Q) and (U, P, Q) spaces [40].

| [2.3.1] |

| [2.3.2] |

Here the initial conditions are at τ = 0.

| [2.3.3] |

| [2.3.4] |

Here the initial conditions are V = 0; U = 0 at P = 0 and Q = 0. When ρ ≠ 1, ηS ≠ ηI and εS ≠ εI, then the system of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 will have distinct and temporally well separated steady states corresponding to the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes. Under such conditions, the system of equations given in Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 will not have common steady state solutions both in (V, S, I) and (U, S, I) spaces (as demonstrated in Fig 2A) as given by most of the currently proposed standard QSSAs.

2.4. Standard quasi steady state solutions

Case I: When (ηS, ηI) → (0,0) simultaneously on Eqs 2.2.7 and 2.2.8, then upon noting the fact that V = εSX and U = ρεIY one can obtain the following set of well-known quasi steady state velocity equations in (V, S, I) and (U, S, I) spaces.

| [2.4.1] |

Particularly, these equations approximate the post-steady state dynamics of competitive inhibition scheme A in the (V, S, I) and (U, S, I) spaces. When (εS, εI) → (0,0) along with (ηS, ηI) → (0,0), then one finds that (V, U) ≅ (0,0) along with (P, Q) ≅ (0,0) in the pre-steady state regime. This results in the reactants stationary assumption where we set S ≅ 1 and I ≅ 1 in Eq 2.4.1 and the quasi-steady state velocities become as follows.

| [2.4.2] |

We denote the approximations given in Eq 2.4.2 as V1 and U1. In terms of the original velocity variables (v, u), Eq 2.4.2 can be written as follows.

| [2.4.3] |

Eq 2.4.3 are generally used to obtain the enzyme kinetic parameters such as (KMS, KMI, vmax, umax) from the steady state based fully competitive inhibition experiments via reciprocal plotting methods under the assumptions that (εS, εI) → (0,0) and ρ = 1. Similarly, when the conditions (ηS, ηI) → (0,0) applied on Eqs 2.2.10 and 2.2.11, one can arrive at the following quasi steady state velocities in the (V, P, Q) and (U, P, Q) spaces.

| [2.4.4] |

In these equations, R is the appropriate real root of the cubic equation aR3 + bR2 + cR + d = 0 where the coefficients a, b, c and d are defined as follows.

| [2.4.5] |

| [2.4.6] |

| [2.4.7] |

| [2.4.8] |

Case II: (ηS, ηI, Q) → (0,0,0). When only Q ≅ 0 which can be achieved by setting εI → 0 in the pre-steady state regime along with the conditions that (ηS, ηI) → (0,0), then Eqs 2.2.10 and 2.2.11 can be approximated in the (X, P, S) and (Y, P, S) spaces as follows.

| [2.4.9] |

Upon the substitution of P = 1 − εSX − S in this equation one finds that,

| [2.4.10] |

| [2.4.11] |

Eq 2.4.10 can be derived from Eq 2.4.9, by using the conservation relationship V + P + S = 1 where V = εSX. Upon solving Eqs 2.4.10 and 2.4.11 for (X, Y) and then converting X into V using Eq 2.2.9, one finds the following expressions for the post-steady state reaction velocity in the (V, S) space under the conditions that (ηS, ηI, Q) → (0,0,0).

| [2.4.12] |

Noting that V + P + S = 1, one can express P as function of S, using P = 1 –V–S where V is defined as in Eq 2.4.12. These two equations parametrically express the post-steady state dynamics of the fully competitive inhibition scheme in the (V, P, S) space where S ∈ [0, 1] acts as the parameter. When P ≅ 0 in the pre-steady state regime which can be achieved by setting εS → 0 along with the conditions that (ηS, ηI) → (0,0), then Eqs 2.2.7 and 2.2.8 can be approximated in the (X, Q, I) and (Y, Q, I) spaces as follows.

| [2.4.13] |

| [2.4.14] |

Upon the substitution of Q = 1 − εIY − I in this equation one obtains,

| [2.4.15] |

Eq 2.4.15 can be derived from Eq 2.4.14, by using the conservation relationship U/ρ + Q + I = 1 where U = ρεIY. Upon solving Eqs 2.4.13–2.4.15 for (X, Y) and then converting Y into U, one finds the following expressions for the post-steady state reaction velocity in the (U, I) space under the conditions that (ηS, ηI, P) → (0,0,0).

| [2.4.16] |

Noting that U/ρ + Q + I = 1, one can express Q as function of I, using Q = 1 –U/ρ–I where U is defined as in Eq 2.4.16. These two equations parametrically express the post-steady state dynamics in the (U, Q, I) space where I ∈ [0,1] acts as the parameter.

Case III. When (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → 0, then one finds that S ≅ 1 − P, I ≅ 1 − Q and (V, U) ≅ (0,0) in the pre-steady state regime from which one can derive the following refined form of sQSSA approximations from Eqs 2.2.7 and 2.2.8. Firstly, by setting (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → (0,0,0,0) in Eqs 2.2.7 and 2.2.8, one obtains the following set of equations.

| [2.4.17] |

Upon solving this system of equations for (X, Y) and then transforming them into the respective velocities (V, U) using Eq 2.2.9, one obtains the following post-steady state approximations in the (V, P, Q) and (U, P, Q) spaces.

| [2.4.18] |

Similarly, using the substitutions of S ≅ 1 − P and I ≅ 1 − Q, Eq 2.4.18 can be rewritten in the (V, S, I) and (U, S, I) spaces as follows.

| [2.4.19] |

Here and . Eqs 2.4.17–2.4.19 are similar to Eq 2.4.1 where μS and μI are replaced with and . Upon applying the stationary reactant assumptions (S, I) = (1, 1) on Eq 2.4.19 one obtains the refined form of sQSSAs. We will show in the later section that this refined form of sQSSAs can accurately predict the reaction velocities (V, U) over wide range of parameter values. Upon dividing the expression of V by the expression of U in Eqs 2.4.18 and 2.4.19, one can obtain the following differential equation corresponding to the (P, Q) and (S, I) spaces under the conditions that (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → (0,0,0,0).

| [2.4.20] |

In Eq 2.4.20 which are valid only in the post-steady state regimes, the initial condition in the (P, Q) space will be P = 0 at Q = 0. Similarly, the initial condition in the (S, I) space will be S = 1 at I = 1. We define fS = vmax/(KMS + e0) and fI = umax/(KMI + e0) as the acceleration factors with respect to the conversion dynamics of substrate and inhibitor into their respective products (P, Q). Now let us define the critical control parameter δ as follows.

| [2.4.21] |

Upon solving Eq 2.4.20 with the given initial conditions and using the definition of δ, one obtains the following integral solutions in the (S, I) and (P, Q) spaces [43,44].

| [2.4.22] |

Here δ is the critical parameter which measures the relative speed at which the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes attain their steady states. The expression for δ given by Eq 2.4.21 is more refined one compared to those definitions given in Refs. [43,44] and straightforwardly one can show that . The expression for V in Eq 2.4.19 in terms of S and I along with the expression for from Eq 2.4.22 parametrically describe the post steady state dynamics of fully competitive enzyme kinetics in the (V, S, I) space where S ∈ [0,1] acts as the parameter. Similarly, expression for V in terms of P and Q as given in Eq 2.4.18 along with the expression for Q that is given in Eq 2.4.22 parametrically describe the post steady state dynamics in (V, P, Q) space where P ∈ [0,1] acts as the parameter. Upon substituting the expression for Q in terms of P obtained from Eq 2.4.22 into the right-hand side of Eq 2.4.18 and noting that S ≅ (1 − P) and I ≅ (1 − Q) when (εS, εI) → 0, so that and , one can obtain the following approximate differential equations corresponding to the (S, τ) and (I, τ) spaces under the conditions that (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → 0.

| [2.4.23] |

Eqs 2.4.22 and 2.4.23, can describe the fully competitive enzyme kinetics over the post-steady state regime of (V, S, I) and (U, S, I) spaces strictly under the conditions that (ηS, κS, ρ) = (ηI, κI, 1) apart from (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → (0,0,0,0). Further, solutions to the variable separated ODEs given in Eq 2.4.23 for the initial conditions (S, I) = (1, 1) at τ = 0 in the (S, τ) and (I, τ) spaces can be implicitly written as follows.

| [2.4.24] |

| [2.4.25] |

When S < 1, then one finds that and and the nonlinear algebraic equation Eq 2.4.24 can be inverted for S under various limiting conditions of δ as follows.

| [2.4.26] |

| [2.4.27] |

| [2.4.28] |

Here W(Z) is the Lambert W function which is the solution of W exp(W) = Z for W [45–47]. Similarly, when I < 1 then one finds that that limδ→0 Iδ → 1 and limδ→∞ Iδ → 0 and the evolution of inhibitor level with time can be derived from Eq 2.4.25 under various values of δ as follows.

| [2.4.29] |

| [2.4.30] |

When δ → ∞, then I → 1 and one finds the following approximate asymptotic expression.

| [2.4.31] |

Expressions similar to Eqs 2.4.23–2.4.31 were proposed earlier to obtain the kinetic parameters from the substrate depletion curves of the fully competitive inhibition scheme [44]. Eqs 2.4.23–2.4.31 are valid only under the conditions that (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → (0,0,0,0). In such scenarios, the right-hand sides of V and U in Eq 2.4.23 can be expanded around δ ≅ 1 in a Taylor series as follows.

| [2.4.32] |

| [2.4.33] |

Clearly, Eqs 2.4.32 and 2.4.33 reduce to the sQSSA forms given in Eq 2.4.1 only when δ → 1. When δ ≠ 1, then the enzyme-substrate-inhibitor system will exhibit complex dynamics with multiple steady states. This introduces an enormous amount error in sQSSA based parameter estimation from the experimental dataset.

Case IV: When (ηS, ηI, P, Q) → (0,0,0,0) so that S ≅ (1 − εSX) and I ≅ (1 − εIY) in the pre-steady state regime of Eqs 2.2.7 and 2.2.8, then one can arrive at the total QSSA [48,49]. We will derive explicit expressions for tQSSA in the later sections.

2.4.1. Exact steady state solutions

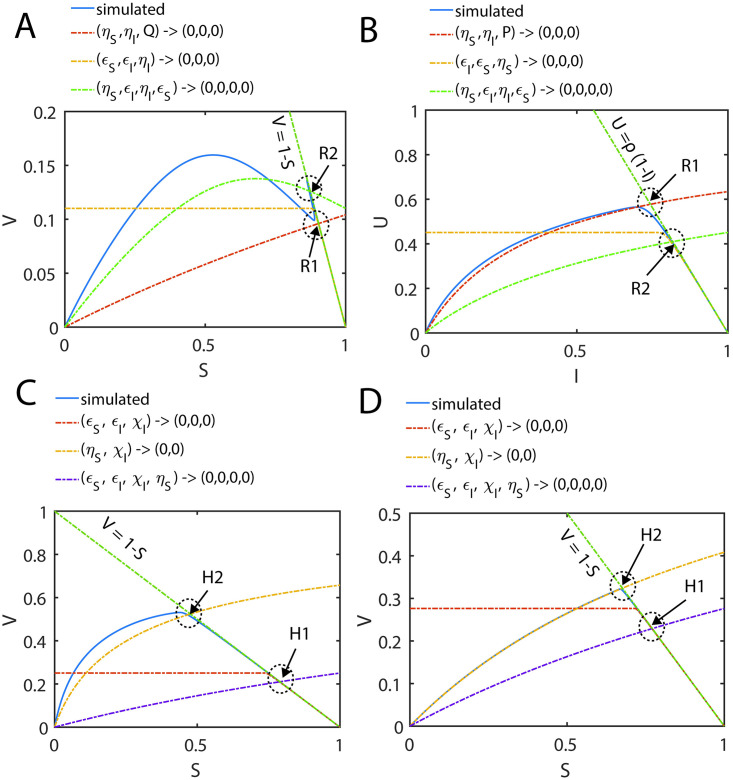

When the steady state timescales associated with the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes are different from each other, then Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 will not have a common steady state solution with respect to both enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes. In such scenarios, one can derive exact steady state velocities as follows. Let us assume that the steady state in the (V, P, S) space occurs at τCP at which (V, S, P, U, I, Q) = (VCP, SCP, PCP, UCP, ICP, QCP) and in the (U, Q, I) space it occurs at τCQ at which (V, S, P, U, I, Q) = (VCQ, SCQ, PCQ, UCQ, ICQ, QCQ). Noting the fact that at τCP, and (Fig 3A and 3B) and one can derive the following expression from Eq 2.3.3 by setting and using the conservation laws.

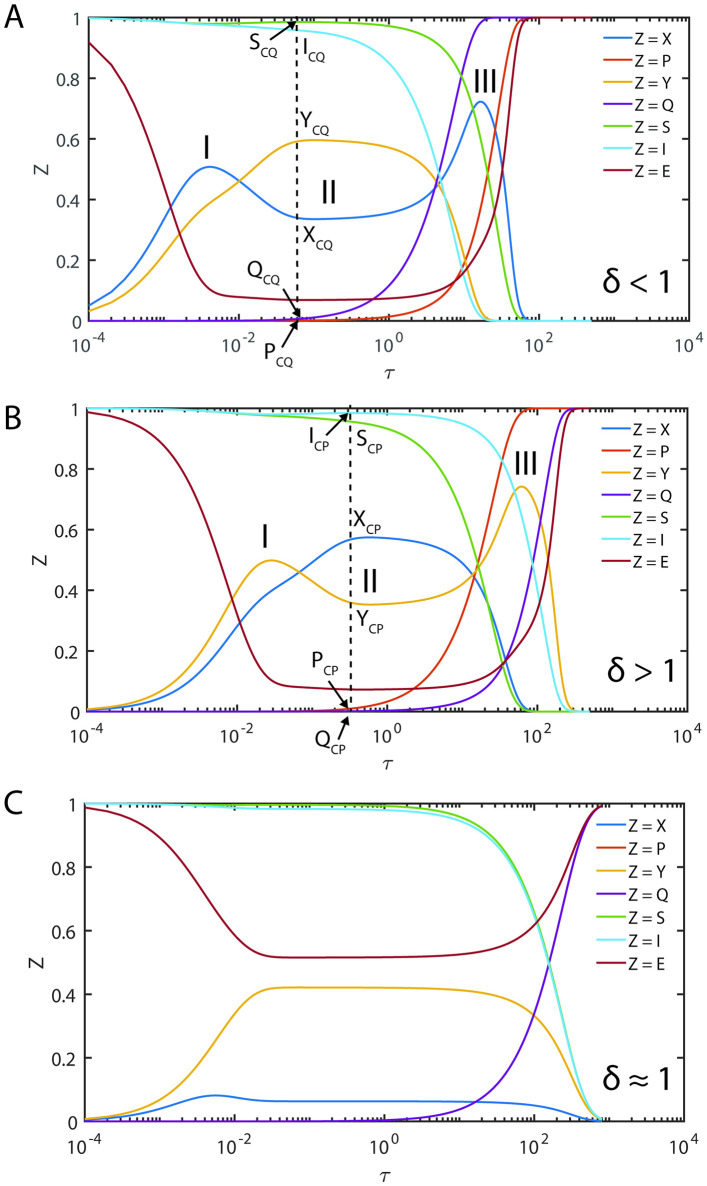

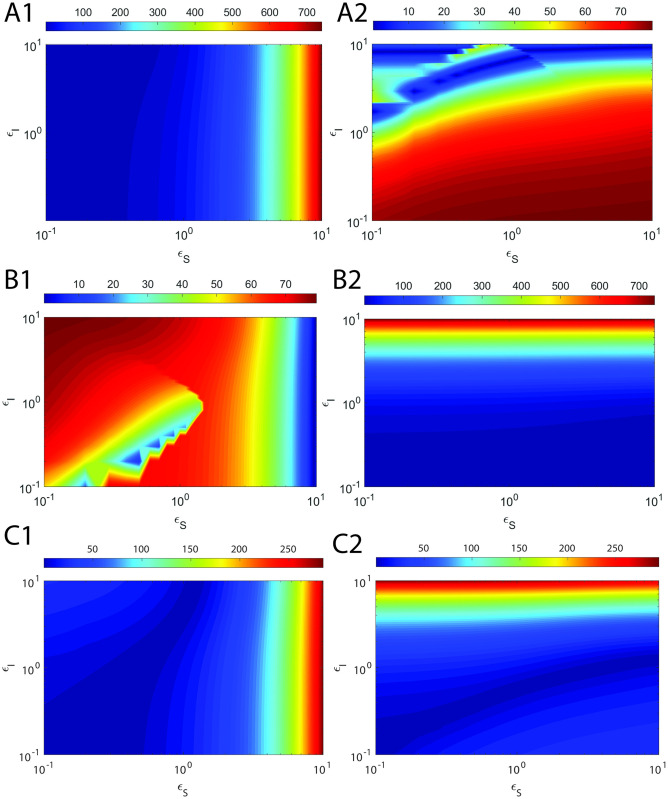

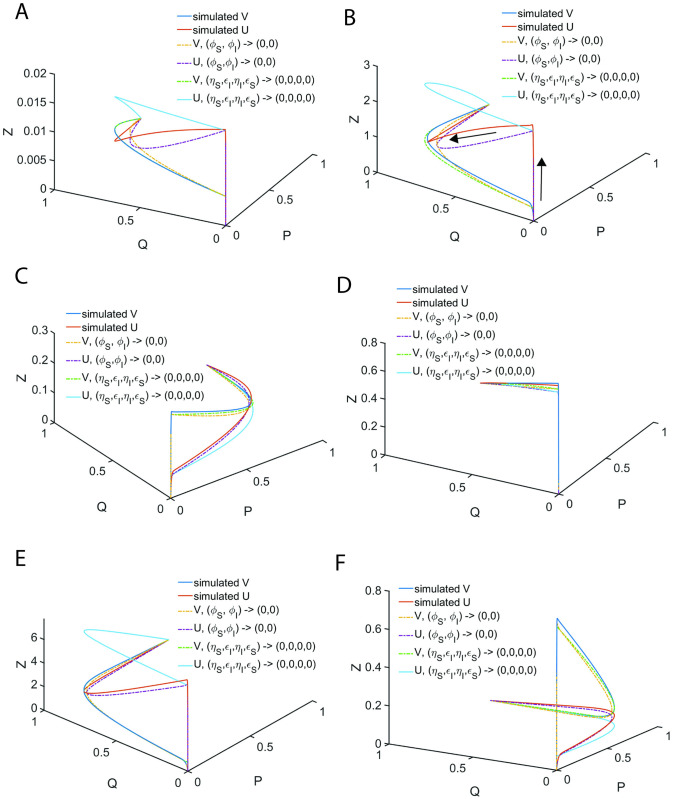

Fig 3. Trajectories of the enzyme kinetics with fully competitive inhibition at different values of δ.

The initial conditions for the simulation of Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 are set as (S, I, E, X, Y, P, Q) = (1,1,1,0,0,0,0) at τ = 0. A. Here the settings are ηS = 0.002, εS = 0.04, κS = 0.2, ηI = 0.01, εI = 0.06, κI = 0.1 and ρ = 3.333, σ = 1, δ = 0.1405, ϒ = 3. When δ < 1 and the steady state timescale of the enzyme-substrate complex is lower than the enzyme-inhibitor complex i.e., τCS < τCI, then the evolution of enzyme-substrate complex shows a bimodal type curve with respect to time. Particularly, when σ = 1 and δ > 1 or δ < 1, the temporal evolution of the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes show a complex behavior with multiple steady states. Single steady state with respect to Y occurs at (YCQ, QCQ, ICQ) and the corresponding non-steady state values in (V, P, S) space are (VCQ, PCQ, SCQ). B. Here the simulation settings are ηS = 0.02, εS = 0.06, κS = 0.1, ηI = 0.003, εI = 0.04, κI = 0.2 and ρ = 0.225, σ = 1, δ = 9, ϒ = 0.33. When δ > 1 and the steady state timescales of enzyme-substrate complex is higher than the enzyme-inhibitor complex i.e. τCS > τCI, then the evolution of enzyme-inhibitor complex shows a bimodal type curve with respect to time. The single steady state with respect to X occurs at (XCP, SCP, PCP) and the corresponding non-steady state values in the (U, I, Q) space are (UCP, ICP, QCP). C. Here the simulation settings are ηS = 0.02, εS = 0.06, κS = 8.1, ηI = 0.003, εI = 0.04, κI = 1.2 and ρ = 0.225, σ = 1, δ = 1.013, ϒ = 4.5.

| [2.4.1.1] |

Upon solving this equation for VCP, one finds the following expression.

| [2.4.1.2] |

Here (VCP, SCP, PCP) are the steady state values in the (V, P, S) space at τCP. In Eq 2.4.1.2, is the standard Michaelis-Menten type velocity term and is the inhibitor dependent modifying factor. The corresponding non-steady state values in the (U, Q, I) space are (UCP, QCP, ICP). Similarly, one obtains the following steady state equation from Eq 2.3.4 by setting and using the conservation laws of (U, Q, I) space for the enzyme-inhibitor complex at the time point τCQ at which and .

| [2.4.1.3] |

Upon solving this equation for UCQ, one finds the following expression.

| [2.4.1.4] |

Here (UCQ, ICQ, QCQ) are the corresponding steady state values in the (U, Q, I) space with respect to the enzyme-inhibitor complex at τCQ and (SCQ, PCQ, VCQ) are the corresponding non-steady state values in the (V, P, S) space. In Eq 2.4.1.4, is the standard Michaelis-Menten type velocity term and is the substrate dependent modifying factor. However, to find VCP and UCQ which are the exact steady state velocities, one needs to know SCP, UCP, ICQ and VCQ. When the steady state timescales corresponding to the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes are the same, then SCP = SCQ, UCP = UCQ, ICQ = ICP and VCQ = VCP as shown in Fig 3C and subsequently Eqs 2.4.1.1–2.4.1.4 reduce to the standard QSSA Eq 2.4.1.

2.4.2. Complexity of the steady states

When δ = 1, then the approximate post-steady state reaction velocities under the conditions that (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → (0,0,0,0) can be given by Eq 2.4.23 which are monotonically increasing (and decreasing) functions of S and I. Approximate steady state velocities (V, U) can be obtained from Eq 2.4.23 by asymptotic extrapolation as (S, I) → (1,1) which is the stationary reactant assumption. When δ ≠ 1, then Eq 2.4.23 will exhibit a turn over type behavior upon increasing (S, I) from (0,0) towards (1,1) with extremum points at which . This dynamical behavior is demonstrated in Fig 3. This means that there are at least two different points at which or within the range (0,0) < (S, I) < (1, 1) depending on the value of δ and sQSSAs given by Eq 2.4.23 are valid only when δ = 1. When δ < 1, then the reaction velocity associated with the enzyme-substrate complex will show two different steady states at which (so that in the (V, S) and (V, P) spaces respectively) as demonstrated in Fig 3A. The velocity expressions given in Eq 2.4.23 corresponding to the stationary reactant assumptions (S, I) → (1,1) approximately represent the first transient steady state in the (V, S) space. The approximate prolonged second steady state corresponding to the enzyme-substrate dynamics can be obtained by solving for S where V is given as in Eq 2.4.23 as follows.

| [2.4.2.1] |

One can obtain PC using the conservation relationship VC + SC + PC = 1. When δ > 1, then the reaction velocity associated with the enzyme-inhibitor complex will show two different steady state regions at which (so that in the (U, I) and (U, Q) spaces respectively) as demonstrated in Fig 3B. The velocity expressions given in Eq 2.4.23 with (S, I) → (1,1) approximately represent the first transient steady state in the (U, I) space. One can obtain the approximate prolonged second steady state velocity corresponding to the enzyme-inhibitor complex UC and the inhibitor concentration IC by solving for I where U is given as in Eq 2.4.23 as follows.

| [2.4.2.2] |

One can obtain QC using the conservation relationship UC/ρ + QC + IC = 1. Here one should note that Eq 2.4.2.1 will not be valid when δ ≥ 1 and Eq 2.4.2.2 will not be valid when δ ≤ 1 since the steady state values can be negative or complex under such conditions. A common steady state can occur only when δ = 1 as demonstrated in Fig 3C and Eq 2.4.23. Remarkably, for the first time in the literature we report this phenomenon and none of the earlier studies on the fully and partial competitive inhibition captured this complex dynamical behavior.

2.5. Solutions under coupled and uncoupled conditions

For the general case, the approximate steady state timescales corresponding to the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes can be obtained as follows. Using the scaling transformations and , Eqs 2.3.1 and 2.3.2 can be rewritten in the following form of Murugan equations [10,40] with appropriate initial conditions.

| [2.5.1] |

| [2.5.2] |

| [2.5.3] |

Here ϕS and ϕI are the ordinary perturbation parameters which multiply the nonlinear terms. Eqs 2.5.1 and 2.5.2 along with the initial conditions given in Eq 2.5.3 completely characterize the dynamical aspects of the fully competitive enzyme inhibition scheme. Eqs 2.5.1–2.5.3 are the central equations of this paper from which we will derive several approximations for the pre- and post-steady state regimes under various set of conditions.

2.5.1. Approximate solutions under coupled conditions

When (ϕS, ϕI) → (0,0), then Eqs 2.5.1 and 2.5.2 become coupled linear system of ordinary differential equations as follows.

| [2.5.1.1] |

| [2.5.1.2] |

Eqs 2.5.1–2.5.3 are derived here for the first time in the literature. We denote Eqs 2.5.1–2.5.3 as Murugan type II equations [40] and the φ-approximations given by Eqs 2.5.1.1 and 2.5.1.2 are exactly solvable. Interestingly, these equations can be rewritten in terms of fourth order uncoupled linear ODEs with constant coefficients both in (M, τ) and (N, τ) spaces as follows (see Appendix A in S1 Appendix for details). In (M, τ) space, one can straightforwardly derive the following results.

| [2.5.1.3] |

| [2.5.1.4] |

Upon obtaining the solution for the (M, τ) space, one can straightforwardly obtain the expression corresponding to the (N, τ) space as follows.

| [2.5.1.5] |

The first two initial conditions corresponding to the fourth order uncoupled ODE given by Eq 2.5.1.3 can be written as follows.

| [2.5.1.6] |

Other two initial conditions directly follow from the initial conditions corresponding to N.

| [2.5.1.7] |

| [2.5.1.8] |

Similar to Eq 2.5.1.3, one can also derive the following solution set corresponding to (N, τ) space.

| [2.5.1.9] |

| [2.5.1.10] |

Upon obtaining the solution for the (N, τ) space, one can directly obtain the expression corresponding to the (M, τ) space as follows.

| [2.5.1.11] |

The initial conditions corresponding to the fourth order uncoupled ODEs given by Eq 2.5.1.9 can be written as follows.

| [2.5.1.12] |

| [2.5.1.13] |

| [2.5.1.14] |

Solution to Eqs 2.5.1.1 and 2.5.1.2 can be obtained either by solving Eqs 2.5.1.3–2.5.1.8 or Eqs 2.5.1.9–2.5.1.14. The detailed expressions for the solution are given in Appendix A in S1 Appendix. Upon obtaining solutions in the (M, τ) and (N, τ) spaces, one can revert back to (P, τ) and (Q, τ) spaces using the scaling transformations (P, Q) = εSηS2(M, N) from which one can obtain the parametric expressions for the trajectories in the (V, P, S), (U, I, Q), (V, I, S), (U, I, S), (V, P, Q), (U, P, Q) and (V, U) spaces using appropriate mass conservation relationships where τ acts as the parameter.

2.5.2. Approximate solutions under uncoupled conditions

When along with the conditions of ϕ-approximations as (ϕS, ϕI) → (0,0), then Eqs 2.5.1 and 2.5.2 can be approximated by the following uncoupled set of ODEs.

| [2.5.2.1] |

| [2.5.2.2] |

The conditions will be true when (k3/k1s0, k2/kii0) → (0,0). Here the initial conditions are at τ = 0. Upon reverting these equations back into the (P, Q, τ) space, one obtains the following set of uncoupled ODEs along with the corresponding initial conditions.

| [2.5.2.3] |

| [2.5.2.4] |

Along with the conditions that , the uncoupled Eqs 2.5.2.3 and 2.5.2.4 are valid only (a) when (ϕS, ϕI) → 0 so that there is no competitive inhibition kinetics or (b) the dissociation rate constants of both the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes are high enough to uncouple the competitive kinetics i.e., (κS, κI) → (∞,∞). Both these conditions will lead to the approximation E = (1 − X − Y) ≅ 1. We will show later that these conditions decrease the mismatch between the steady state timescales of the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes. Upon solving these ODEs with the given initial conditions, we can derive the approximate expressions for the dynamics of the competitive inhibition scheme (P, Q, V, U, S, I) as follows [10,40].

| [2.5.2.5] |

| [2.5.2.6] |

| [2.5.2.7] |

| [2.5.2.8] |

| [2.5.2.9] |

The expressions given in Eqs 2.5.2.5–2.5.2.9 for (V, P, S, τ) space will be valid only when and those expressions given for (Q, U, I, τ) space will be valid only when . Upon solving and for τ in where (V, U) are given as in Eqs 2.5.2.7 and 2.5.2.8, one can obtain the following approximations for the steady state timescales corresponding to substrate and inhibitor conversion dynamics. When , then one finds that,

| [2.5.2.10] |

When , then one finds that,

| [2.5.2.11] |

Here τCS and τCI are the approximate timescales at which the steady states with respect to the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes occur under uncoupled conditions. Upon substituting the expression for τCS into the expressions for (V, P, S) given in Eqs 2.5.2.5–2.5.2.9 one can obtain the corresponding steady state values (VC, PC, SC). In the same way, upon substituting the expression for τCI into the expressions for (U, Q, I) one can obtain the corresponding steady state values (UC, QC, IC). Clearly, the condition τCS ≅ τCI is critical for the occurrence of a common steady state with respect to the reaction dynamics of both the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes. When τCI > τCS, then the substrate depletion with respect to time will show a typical non-monotonic trend since the inhibitor reverses the enzyme-substrate complex formed before time τCI in the pre-steady state regime. In the same way, when τCI < τCS then the inhibitor depletion will show a non-monotonic behavior since the substrate reverses the enzyme-inhibitor complex formed before time τCS in the pre-steady state regime. These phenomena eventually introduce significant amount of error in various QSSAs. Under uncoupled conditions i.e., when , then one can rewrite the uncoupled approximations given in Eqs 2.5.2.3 and 2.5.2.4 over (V, P) and (U, Q) spaces as follows.

| [2.5.2.12] |

Noting that , one can obtain the ODE corresponding to the (V, S) space as follows.

| [2.5.2.13] |

| [2.5.2.14] |

Noting that , one can obtain the ODE corresponding to the (U, I) space as follows.

| [2.5.2.15] |

Upon considering only the linear, uncoupled portions in the (V, P) space as given in Eq 2.5.2.12, one obtains the following approximations for V and S as functions of P.

| [2.5.2.16] |

Using the conservation laws, one finds the following.

| [2.5.2.17] |

Here RP is the solution of the following nonlinear algebraic equation.

| [2.5.2.18] |

In this equation, . These approximate equations parametrically describe the dynamics of the enzyme catalyzed substrate conversion in the entire regime of (V, P, S) space from (V, P, S) = (0, 0, 1) to (V, P, S) = (0, 1, 0) including the steady states (VC, PC, SC) that occurs at . Here P acts as the parameter. Further, upon solving in Eq 2.5.2.16 one obtains the steady state concentration of the product of substrate as follows.

| [2.5.2.19] |

In this equation, . Upon substituting the expression of PC into the expressions of V and S as given in Eqs 2.5.2.16 and 2.5.2.17, one can obtain the steady state expressions for VC and SC. In the same way, upon considering only the linear, uncoupled portions in the (U, Q) space as given in Eq 2.5.2.14, one obtains the following approximations for U and I as functions of Q.

| [2.5.2.20] |

Using the conservation laws, one finds the following.

| [2.5.2.21] |

Here RQ is the solution of the following nonlinear algebraic equation.

| [2.5.2.22] |

In this equation, . These approximate equations parametrically describe the dynamics of the enzyme catalyzed inhibitor conversion in the entire regime of (U, Q, I) space from (U, Q, I) = (0, 0, 1) to (U, Q, I) = (0, 1, 0) including the steady states (UC, QC, IC) that occurs at . Here Q acts as the parameter. Further, upon solving in Eq 2.5.2.20 one obtains the steady state level of the product of inhibitor as follows.

| [2.5.2.23] |

Here the term b is defined as in Eq 2.5.2.22. Upon substituting the expression of QC for Q into the expressions of U and I as given in Eqs 2.5.2.20 and 2.5.2.21, one can obtain the steady state expressions for UC and IC.

2.6. Approximate pre-steady state solutions

Using the scaling transformation P = εSηS2M one can rewrite the set of coupled nonlinear ODEs corresponding to the fully competitive inhibition scheme given in Eqs 2.5.1 and 2.2.11 in the (M, Y, Q, τ) space as follows.

| [2.6.1] |

Noting that , one finds from Eq 2.2.11 that,

| [2.6.2] |

Here the initial conditions are at τ = 0. Using these equations one can derive the pre-steady state expressions associated with the enzyme-substrate complex under various conditions as follows.

Case I: When (εI, ηI, εS) → (0,0,0), then one finds that I = (1 − εIY − Q) ≅ 1 − εIY since Q ≅ 0 in the pre-steady state regime. Under such conditions one can arrive at the approximation for Y from Eq 2.6.2 as . Upon substituting this expression for Y in Eq 2.6.1 and using the variable transformation , one finally arrives at the following approximate ODEs corresponding to the pre-steady state regimes in the (M, τ) and (F, M) spaces.

| [2.6.3] |

| [2.6.4] |

Case II: When (εI, ηI, ϕS) → (0,0,0) in Eqs 2.6.1 and 2.6.2, then following the same arguments as in Eqs 2.6.3 and 2.6.4, one finds the following refined approximations in the (M, τ) and (F, M) spaces.

| [2.6.5] |

| [2.6.6] |

We will discuss the solutions of Eqs 2.6.5 and 2.6.6 in the later section in detail. Eq 2.6.3 is a linear second order ODE with constant coefficients that is exactly solvable. Upon solving the nonlinear ODE given in Eq 2.6.4 along with the initial condition, one arrives at the following approximate integral solution under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → 0 in the (F, M) space.

| [2.6.7] |

Upon solving Eqs 2.6.3 and 2.6.4 with the given initial conditions as in Eq 2.6.7 and then reverting back to (V, P), (V, S) and (V, τ) spaces using the transformations and using the conservation relationships, we arrive at the following approximate solutions under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → (0,0,0). In the (V, τ) space one finds the following result.

| [2.6.8] |

In the (V, P) space the approximate solution becomes as follows.

| [2.6.9] |

Upon solving Eq 2.6.4 implicitly in the (F, M) space and then reverting back to (V, P) space using the transformation and substituting P = 1 –V–S before the inversion of (Appendix B in S1 Appendix) the hitherto obtained implicit expression in terms of Lambert W function, one obtains the following pre-steady state solution in the (V, S) space under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → (0,0,0).

| [2.6.10] |

The parameters a and b in Eq 2.6.10 are defined as follows.

| [2.6.11] |

By expanding Eq 2.6.10 in a Taylor series around S = 1, one finds that V ≅ 1 − S + Ο((S − 1)2) which means that P ≅ 0 in the pre-steady state regime. It is also interesting to note that all the trajectories in the (V, S) space will be confined inside the triangle defined by the lines V ≅ 1 − S, V = 0 and S = 0. When P or τ becomes sufficiently large, then Eqs 2.6.8 and 2.6.9 asymptotically converge to the following limiting value that is close to the steady state reaction velocity under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → (0,0,0). We denote this approximation as V2.

| [2.6.12] |

We will show in the later sections that this approximation works very well in predicting the steady state reaction velocities over wide ranges of parameters. One can also arrive at Eq 2.6.12 under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI, ηS) → (0,0,0,0) similar to the refined sQSSA expression given in Eqs 2.4.19. In terms of original variables, this equation can be written as follows.

| [2.6.13] |

Similar to Eqs 2.6.1 and 2.6.2, using the transformation , one can rewrite Eqs 2.5.2 and 2.2.7 as the following coupled system of ODEs.

| [2.6.14] |

Noting that , one finds from Eq 2.2.10 that,

| [2.6.15] |

Here the initial conditions are ; N = 0; X = 0 at τ = 0. Using these equations one can derive the pre-steady state expressions associated with the enzyme-inhibitor complex under various conditions.

Case III: When (εS, ηS, εI) → (0,0,0), then S = (1 − εS X − P) ≅ 1 − εS X and P ≅ 0 in the pre-steady state regime and one finds from Eq 2.6.15 that . Upon substituting this expression of X into Eq 2.6.14, setting (εS, ηS, εI) → 0 and using the transformation in Eqs 2.6.14 and 2.6.15 one can derive the following approximations in the (N, τ) and (G, N) spaces.

| [2.6.16] |

| [2.6.17] |

Case IV: When (εS, ηS, ϕI) → (0,0,0), then following the same arguments with respect to Eqs 2.6.5 and 2.6.6, one finds the following approximations in the (N, τ) and (G, N) spaces.

| [2.6.18] |

| [2.6.19] |

We will discuss the solutions to Eqs 2.6.18 and 2.6.19 in the later section in detail. Eq 2.6.16 is a second order linear ODE with constant coefficients that is exactly solvable. Upon solving the nonlinear ODE given in Eq 2.6.17 along with the initial condition, one can arrive at the following integral solution in the pre-steady state regime in the (G, N) space.

| [2.6.20] |

Upon solving Eqs 2.6.16 and 2.6.17 with the given initial conditions and then reverting back to the (U, Q), (U, I) and (U, τ) spaces using the transformations one finds the following approximate solutions to Eqs 2.6.16 and 2.6.17 under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → (0,0,0). In (U, τ) space one finds the following result.

| [2.6.21] |

In (U, Q) space the approximate solution becomes as follows.

| [2.6.22] |

Upon solving Eq 2.6.17 implicitly in (G, N) space and then reverting back to (U, Q) space using the transformations and substituting Q = 1 –U/ρ–I before the inversion in terms of Lambert W function, one obtains the following pre-steady state solution in the (U, I) space under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → (0,0,0).

| [2.6.23] |

The terms g and h in Eq 2.6.23 are defined as follows.

| [2.6.24] |

Upon expanding the right-hand side of Eq 2.6.23 in a Taylor series around I = 1, one finds that U ≅ ρ(1 − I) + Ο((I − 1)2) which means that Q ≅ 0 in the pre-steady state regime where Eqs 2.6.20–2.6.24 are valid. When Q or τ becomes sufficiently large, then Eqs 2.6.21 asymptotically converges to the following limiting value that is close to the steady state value of U under the conditions that (εS, ηI, εI) → (0,0,0). We denote this approximation as U2. We will show in the later sections that this approximation works very well over wide ranges of parameter values.

| [2.6.25] |

In terms of original variables, this equation can be written as follows.

| [2.6.26] |

This equation is similar to the refined sQSSA given in Eq 2.4.19 that was derived under the conditions that (εI, ηI, εS, ηS) → (0,0,0,0).

2.6.1. Steady state timescales

From the pre-steady state velocity expressions given in Eqs 2.6.8 and 2.6.21, one can find the following approximate steady state timescales associated with the substrate and inhibitor conversion dynamics under coupled conditions.

| [2.6.1.1] |

In terms of original variables, Eq 2.6.1.1 can be written as follows.

| [2.6.1.2] |

Eq 2.6.1.2 are similar to the equations derived in Ref. [44] (see Eqs 34–35 in this reference) for the steady state timescales. However, the numerator terms were set to unity for ρ = 1 and also e0 was not added with (KMS, KMI) in their expressions. When e0 → ∞, then (tCS, tCI) → (0,0) is a reasonable observation from Eq 2.6.1.2. Further, those approximate expressions suggested in Ref. [44] for tCS and tCI predicted that when (i0, s0) → (∞, ∞), then (tCS, tCI) → (0,0). However, when i0 increases, then the probability of binding of substrate with the enzyme will decrease. As a result, when s0 is fixed, then tCS will increase asymptotically towards a limiting value as i0 → ∞. Similarly, when s0 increases, then the probability of binding of inhibitor with the enzyme will decrease towards a minimum. As a result, when i0 is fixed, then tCI will increase asymptotically towards a limiting value as s0 → ∞. In this context, Eq 2.6.1.2 correctly predict the following limiting behaviors of the steady state timescales.

| [2.6.1.3] |

| [2.6.1.4] |

Here one should note that s0 → 0 or i0 → ∞ will have similar limiting behavior on tCS. This is reasonable since setting i0 → ∞ will eventually decreases the binding probability of substrate with the enzyme to a minimum. Similarly, one also finds the following limiting behaviors of tCI.

| [2.6.1.5] |

| [2.6.1.6] |

Here one should note that i0 → 0 or s0 → ∞ will have similar limiting behavior on tCI since setting i0 → ∞ will eventually decreases the binding probability of inhibitor with the enzyme. Eqs 2.6.1.3–2.6.1.6 should be interpreted only in the asymptotic sense since setting (s0, i0) = (0, 0) will eventually shuts down the respective substrate or inhibitor catalytic channel. Eq 2.6.1.1 clearly suggest that a common steady state between enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes can occur only when αI ηS ≅ αS ηI or explicitly when the ratio . When ηS ≅ ηI, then the condition ψ ≅ 1 can be achieved by simultaneously setting large values for any one of the parameters (εS, κS) in the numerator part and any one of the parameters (εI, κI) from the denominator part so that their ratio ψ tends towards one. For example, one can consider setting (εI, κS) → ∞ or a combination (εS, κI) → ∞ and so on. Under such conditions, the error in the estimation of the kinetic parameters using sQSSAs will be at minimum. In general, the condition for the minimal error in sQSSA can also be derived from ψ ≅ 1 in the following form.

| [2.6.1.7] |

Upon considering the connection between the parameters (ρ, γ, σ) as given in Eq 2.2.13 and noting that (ρ, σ) ≅ (1,1) for most of the substrate-inhibitor pairs, the required conditional Eq 2.6.1.7 can be rewritten upon setting ρσ = 1 as follows.

| [2.6.1.8] |

In terms of original variables this conditional equation Eq 2.6.1.8 can be written as follows.

| [2.6.1.9] |

In most of the in vitro quasi-steady state experiments, one sets larger values for (s0, i0) than (e0, KMS, KMI) so that the left-hand side of Eq 2.6.1.9 tends towards unity which is essential (but not sufficient) condition to minimize the error of such QSSAs as suggested [43,44] by most of the earlier studies in a slightly different form as ρ ≅ 1, σ ≅ 1 and εIS ≅ 1. Further, Eqs 2.6.1.8 and 2.6.1.9 will work only when the condition ρσ = 1 is true.

2.7. Minimization of error in sQSSA

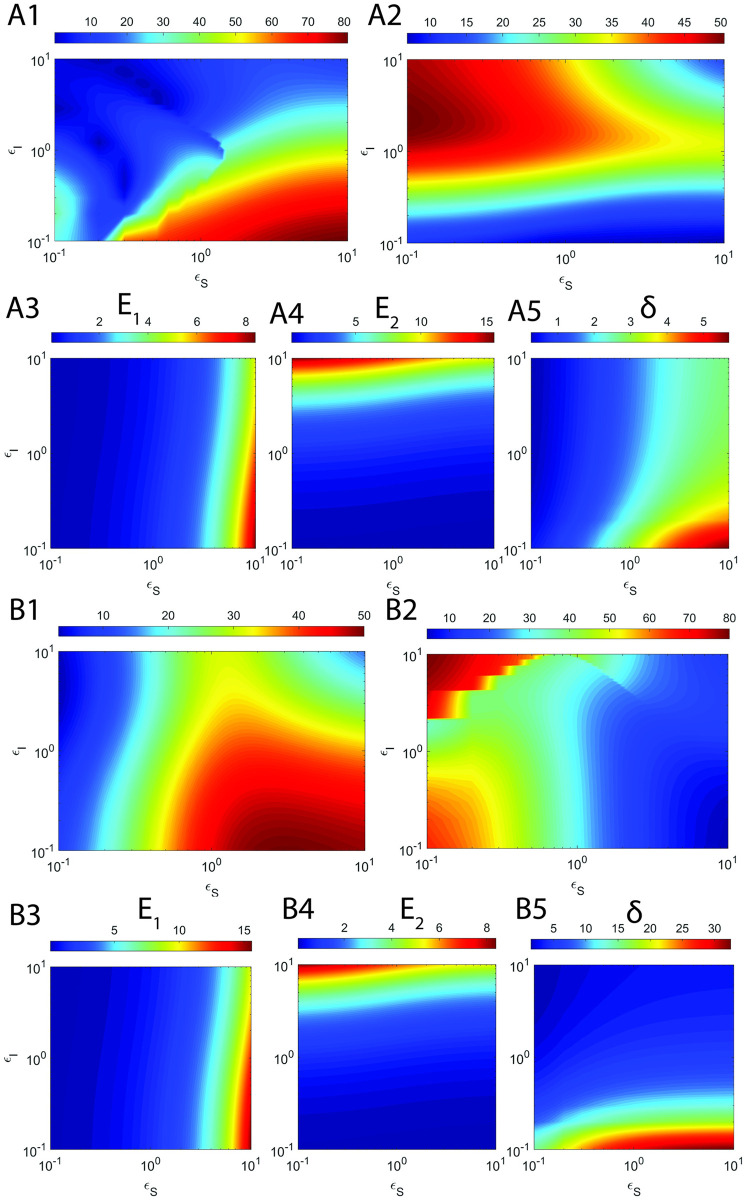

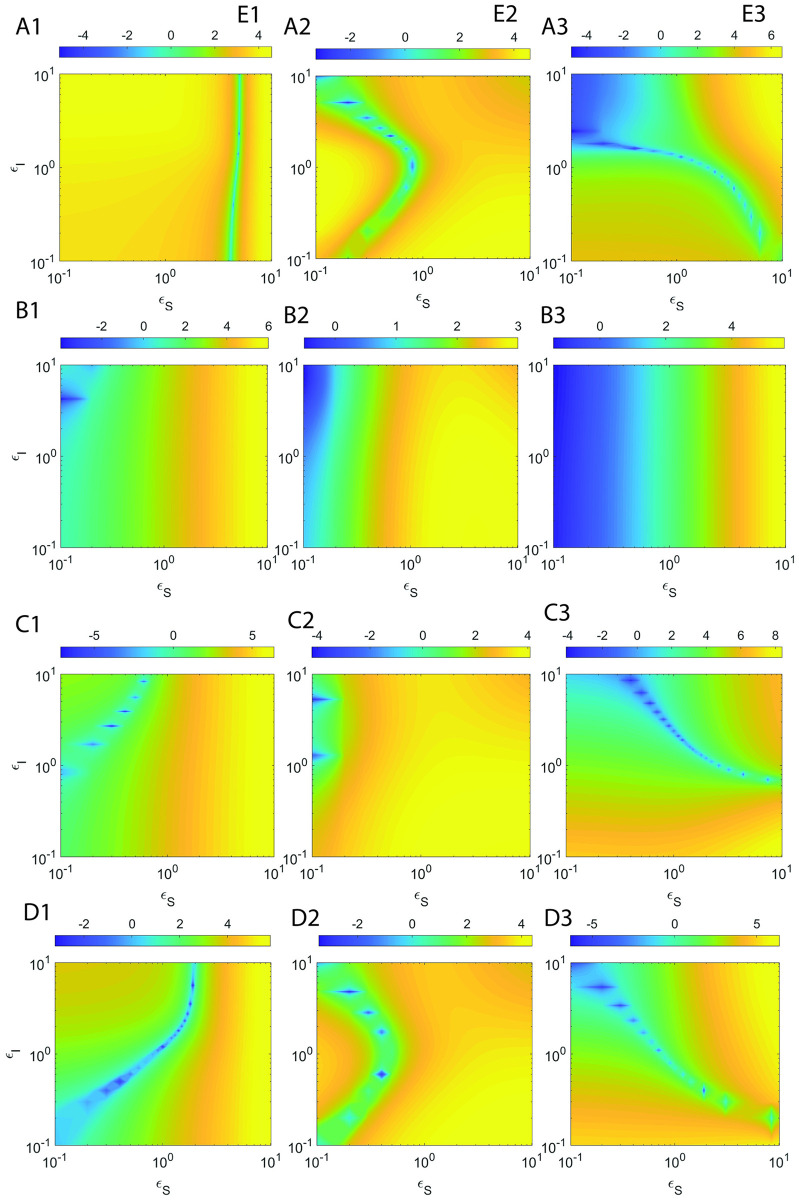

The essential conditions required to minimize the error in various sQSSAs of fully competitive inhibition scheme with stationary reactants assumption can be obtained as follows. The sQSSAs (Eq 2.4.19) describe only the post steady state regime in the (V, S, I) and (U, S, I) spaces and approximate the entire pre-steady state regime with the asymptotic velocities corresponding to (S, I) → (1,1). To extract the enzyme kinetic parameter, one generally uses Eq 2.4.19 with stationary reactant assumptions (S, I) = (1, 1) that does not account for the pre-steady state regime. From the pre-steady state approximations given in Eqs 2.6.8 and 2.6.21 and the refined sQSSAs given in Eq 2.4.19 with (S, I) → (1,1), one can define the overall error associated with the asymptotic approximation of pre-steady state regime by sQSSAs as follows [40].

| [2.7.1] |

| [2.7.2] |

Here τCS and τCI are defined as in Eq 2.6.1.1, HS and HI are the overall errors in the refined sQSSAs on enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes respectively. Upon solving for εS and for εI after substitution of the approximate expressions for τCS and τCI from Eq 2.6.1.1, and expanding the terms αS, αI, and with their original definitions, one obtains the following expressions for εS,max and εI,max at which the errors due to sQSSAs attain maxima.

| [2.7.3] |

| [2.7.4] |

Clearly, the following generalized conditions i.e., εS ≪ εS,max and εI ≪ εI,max are essential to minimize the error in sQSSAs (refined sQSSA given in Eq 2.4.19 with (S, I) → (1,1)) associated with the enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor dynamics since (ηS, ηI, εS, εI) → (0,0,0,0) are the preconditions for the validity of sQSSA. One can write these sufficient conditions (we denote them as E1 and E2) explicitly as follows.

| [2.7.5] |

| [2.7.6] |

Clearly, E1 will be true upon setting εS → 0 and E2 will be true upon setting εI → 0. These conditions eventually drive the pre-steady state timescales towards zero leading to less error in sQSSA based parameter estimation. E1 is essential to minimize the error in substrate conversion velocity and E2 is essential to minimize the error in inhibitor conversion velocity. We will show later that there are strong correlations between Eqs 2.7.5 and 2.7.6 and the corresponding observed overall errors in the estimation of (V, U) using the refined form of sQSSAs.

2.8. Approximate time dependent solutions

From Eqs 2.6.5 and 2.6.6 one can derive the refined expressions for the reaction velocity V and product P under the conditions that (εI, ηI, ϕS) → (0,0,0) as follows.

| [2.8.1] |

| [2.8.2] |

Here the terms a, b and c are defined as follows.

| [2.8.3] |

From Eqs 2.6.18 and 2.6.19 one can derive the refined expressions for the reaction velocity U and product Q under the conditions that (εI, ηS, ϕS) → (0,0,0) as follows.

| [2.8.4] |

| [2.8.5] |

Here the terms r, g and d are defined as follows.

| [2.8.6] |

Clearly, one can conclude from Eqs 2.8.1 and 2.8.4 that there exist four different timescales viz. two in the pre-steady state regime and two in the post steady state regimes corresponding to enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor conversions. We denote them as (τS1, τS2, τI1, τI2). From Eqs 2.8.1 and 2.8.4 one can define these timescales as follows.

| [2.8.7] |

The terms a, b, c, r, g and d are defined as in Eqs 2.8.3 and 2.8.6. Here τS1 and τS2 are the pre-steady state and post-steady state timescales corresponding to enzyme-substrate dynamics and τI1 and τI2 are the pre-steady state and post steady state timescales associated with the enzyme-inhibitor dynamics. The errors in various QSSAs will decrease when the timescale separation ratios tend towards zero.

| [2.8.8] |

Eqs 2.8.1–2.8.7 can approximately describe the dynamics of fully competitive enzyme kinetics scheme over the entire (V, U) space in the parametric form when the conditions associated with Eqs 2.8.1 and 2.8.4 are true.

2.9. Partial competitive inhibition

The differential rate equations corresponding to the Michaelis-Menten type partial competitive inhibition Scheme B can be written as follows.

| [2.9.1] |

| [2.9.2] |

| [2.9.3] |

| [2.9.4] |

Here and the dynamical variables (s, e, x, y, i, p) denote respectively the concentrations (M) of substrate, enzyme, enzyme-substrate complex, enzyme-inhibitor complex and free inhibitor. Further k1 and ki are the respective bimolecular forward rate constants (1/M/s) and k-1 and k-i are the respective reverse rate constants (1/s) and k2 is the product formation rate constant (1/s). Here the initial conditions are (s, e, x, y, i, p) = (s0, e0, 0, 0, i0, 0) at t = 0. The mass conservation laws are e = e0 − x − y; s = s0 − x − p; i = i0 − y. When t → ∞, then the reaction trajectory ends at (s, e, x, y, i, p) = (0, e∞, 0, y∞, i∞, s0) where (e∞, y∞, i∞) are the equilibrium concentrations of free enzyme, enzyme-inhibitor complex and free inhibitor. The steady state of the enzyme-substrate complex occurs at the time point 0 < tCS < ∞ when and the steady state of the enzyme-inhibitor complex occurs at the time point 0 < tCY < ∞ when where one also finds from Eq 2.9.3 that . Similar to the scaling transformations used in Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9, Eqs 2.9.1–2.9.4 can also be reduced to the following set of coupled dimensionless equations.

| [2.9.5] |

| [2.9.6] |

| [2.9.7] |

| [2.9.8] |

Here (S, E, X, Y, I, P) ∈ [0,1]. The mass conservation relations in the dimensionless form can be written as I = (1 − εI Y), E + X + Y = 1 and V + P + S = 1. Other dimensionless parameters are defined similar to the case of fully competitive inhibition scheme as given in Eqs 2.2.2–2.2.6. Here (χI, ηS) are singular perturbation parameters and (εI, εS, κS, κI) are ordinary perturbation parameters. The initial conditions in the dimensionless space are (S, E, X, Y, I, P) = (1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0) at τ = 0. When τ → ∞, then the reaction ends at (S, E, X, Y, I, P) = (0, E∞, 0, E∞, I∞, 1) where the terms (E∞, Y∞, I∞) are the final equilibrium concentrations of the free enzyme, enzyme-inhibitor complex and free inhibitor. When (χI, ηS) → (0,0), then Eqs 2.9.5 and 2.9.6 can be equated to zero and solved for (X, Y). Under these conditions, upon converting X into the velocity using V = εS X as given in Eq 2.5.7 one obtains the following sQSSA results.

| [2.9.9] |

Upon applying the stationary reactants assumptions (S, I) → (1,1) under the condition that (ηS, εS, εI, χI) → (0,0,0,0), one finally obtains the following steady state expressions.

| [2.9.10] |

The reaction velocity V in Eq 2.9.10 can be written in terms of the original variables as follows.

| [2.9.11] |

Eq 2.9.11 is generally used to estimate the kinetic parameters from the experimental datasets obtained from partial competitive inhibition experiments using double reciprocal plotting methods where the observed linearly increases with i0. Upon substituting the conservation law I = (1 − εI Y) in Eq 2.9.9 for Y and subsequently solving the resulting quadratic equation for Y, one obtains the following post-steady state approximations in the (V, S) and (Y, S) spaces under the conditions that (χI, ηS) → (0,0).

| [2.9.12] |

By setting I = (1 − εI Y) (where Y is expressed as a function of S as given in Eq 2.9.12) in the expression of V in Eq 2.9.9, one obtains the post steady state approximation in the (V, S) space. Using the mass conservation laws, one can directly obtain the post-steady state approximation for P from P = 1 − V − S. Post-steady state approximation in the (I, S) space can be expressed in a parametric form where S ∈ [0,1] acts as the parameter. One can obtain the exact equilibrium values I∞ and Y∞ by setting S → 0 in Eq 2.9.12 as follows.

| [2.9.13] |

Here we have defined βI = 1 + εI + κI. In Eq 2.9.13, one finds from the mass conservation law that I∞ = 1 − εI Y∞.

2.9.1. Variable transformations

Using the transformation along with the other scaling transformations given as in Eqs 2.2.7–2.2.9 and 2.9.5–2.9.7 can be reduced to the following set of coupled nonlinear second order ODEs in the (P, Y, τ) space.

| [2.9.1.1] |

| [2.9.1.2] |

Here the initial conditions are ; P = 0; Y = 0 at τ = 0. Eqs 2.9.1.1 and 2.9.1.2 can be transformed into the (V, Y, P) and (V, Y, S) spaces using the substitution and associated mass conservation laws as follows.

| [2.9.1.3] |

Particularly, upon substituting P = 1 − V − S in this equation one finds that,

| [2.9.1.4] |

Upon the substitution of in Eq 2.9.1.2 one finds that,

| [2.9.1.5] |

In this equation is defined as follows.

| [2.9.1.6] |

Here the initial conditions are V = 0; P = 0; Y = 0 at τ = 0. Eqs 2.9.1.1–2.9.1.6 completely characterize the partial competitive inhibition scheme in the (V, Y, P) and (V, Y, S) spaces from which we will derive following approximations under various conditions.

2.9.2. Post-steady state approximations

Case I: When (ηS, χI, εS, εI) → 0, then using X = V/ƐS, Eqs 2.9.1.3–2.9.1.5 can be approximated in the (X, Y, P) space as follows.

| [2.9.2.1] |

Upon solving Eqs 2.9.2.1 for (X, Y) and noting that S ≅ 1 − P, I ≅ 1 in such conditions, we obtain the following results similar to Eq 2.4.1 related to the fully competitive inhibition scheme in the (V, S, I) and (Y, S, I) spaces.

| [2.9.2.2] |

Here we have defined . The expression for V in Eq 2.9.2.2 is similar to the one in Eq 2.9.9 where μS and κI are replaced with and and I = 1 in the definition of Y. The post steady state approximation in the (S, I) space can be expressed in a parametric form using I = 1 − εI Y. Here Y is given in terms of S as in Eq 2.9.2.2 where S ∈ [0,1] acts as the parameter. Upon applying the transformation in Eqs 2.9.1.1 and 2.9.1.2, one finally arrives at the following set of coupled nonlinear second order ODEs in the (M, Y, τ) space.

| [2.9.2.3] |

| [2.9.2.4] |

Here the initial conditions are ; M = 0; Y = 0 at τ = 0. Eqs 2.9.2.3 and 2.9.2.4 are the central equations corresponding to the Michaelis-Menten type enzyme kinetics with partial competitive inhibition. Using Eqs 2.9.2.3 and 2.9.2.4, one can derive several approximations under various limiting conditions as follows.

Case II: When (χI, εI, ϕS) → 0, then from Eq 2.9.2.4 one finds that which results in the approximation . Upon substituting this approximation for Y in Eqs 2.9.2.3, and setting ϕS = ηS εS → 0, one arrives at the following second order linear ODE corresponding to the (M, τ) space.

| [2.9.2.5] |

Upon solving this linear ODE for M with respect to the given initial conditions and then reverting back to the velocity V using the transformation , one can obtain the following expression in the (V, τ) space under the conditions that (εI, χI, ϕS) → (0,0,0).

| [2.9.2.6] |

The terms a, b and c in Eq 2.9.2.6 are defined as follows.

| [2.9.2.7] |

Upon solving dV⁄dτ = 0 for τ in Eq 2.9.2.6, one can obtain the following expression for the steady state timescale associated with the enzyme-substrate complex.

| [2.9.2.8] |

In this equation, b is defined as follows.

| [2.9.2.9] |

2.9.3. Pre-steady state approximations

Case III: When ηS → 0, then one obtains the uncoupled equation in (Y, τ) space from Eq 2.9.2.4 as . The integral solution of this first order nonlinear ODE with the initial condition [Y]τ = 0 = 0 can be written as follows.

| [2.9.3.1] |

In this equation . Eq 2.9.3.1 suggests the following the timescale associated with the enzyme-inhibitor complex to attain the steady state under the conditions that ηS → 0.

| [2.9.3.2] |

Clearly, Eqs 2.9.1.3–2.9.1.5 can have common steady states only when τCY = τCS. We will show in the later sections that when τCY > τCS, then the substrate depletion with respect to time will show a typical non-monotonic trend since the inhibitor reverses the enzyme-substrate complex which is formed before the timescale τCY in the pre-steady state regime with respect to the enzyme-substrate complex. This phenomenon introduces significant amount of error in sQSSA. Using the transformation , Eqs 2.9.2.3 and 2.9.2.4 can be rewritten in the (F, Y, M, τ) space with the initial conditions F = 0 at M = 0 and Y = 0 at τ = 0 as follows.

| [2.9.3.3] |

| [2.9.3.4] |

Case IV: When the conditions (εS, χI, εI) → 0 are true, then one can derive the approximate differential rate equations governing the pre-steady state dynamics in the (F, M) and (F, Y) spaces from Eqs 2.9.3.3 and 2.9.3.4 as follows.

| [2.9.3.5] |

The initial condition corresponding to Eq 2.9.3.5 is F = 0 at M = 0. Upon substituting the expression of Y into the differential equation corresponding to the (F, Y, M) space given in Eq 2.9.3.5, one finally obtains the following approximation.

| [2.9.3.6] |

Upon solving Eq 2.9.3.6 with the given initial condition in the (F, M) space, and then reverting back to (V, P) space using the transformations , one finally obtains the following expression for the pre-steady state regime in the (V, P) space under the conditions that (εS, χI, εI) → 0.

| [2.9.3.7] |

To obtain the expression for the (V, S) space one needs to first solve Eq 2.9.3.6 implicitly in the (V, P) space. Then replace P in this implicit solution with the conservation law P = 1 –V–S leading the implicit solution in the (V, S) space that can be inverted for V as a function of S in terms of Lambert W function (see Appendix B in S1 Appendix) as follows.

| [2.9.3.8] |

In this equation, the terms a and b are defined as,

| [2.9.3.9] |

By expanding the right-hand side of Eq 2.9.3.8 in a Taylor series around S = 1, one finds that V ≅ 1 −S + Ο((S − 1)2) which means that P ≅ 0 in the pre-steady state regime. One can directly translate the (V, S) space approximation given in Eq 2.9.3.8 into the pre-steady state of (Y, S) space under the conditions that (εS, χI, εI) → 0 using Eq 2.9.3.5 that results in . But there is a mismatch in the required initial condition for Y in this expression i.e., Y = 0 at S = 1. Particularly, Eq 2.9.3.5 sets the initial condition for Y as at S = 1 (at which V = 0 and therefore F = 0) that is inconsistent since Y ≠ 0 at τ = 0 or S = 1. Detailed numerical analysis of the (Y, S) space trajectories suggests an approximate expression as for the pre-steady state regime under the conditions that (εS, χI, εI) → (0,0,0). Explicitly, one can write this approximation derived from numerical analysis as follows.

| [2.9.3.10] |

Here a and b are defined as in Eq 2.9.3.9. By expanding Eq 2.9.3.10 in a Taylor series around S = 1, one finds that . Using Eq 2.9.3.10 and the conservation law I = (1 − εI Y), one can express I as a function of S in the pre-steady state regime of (I, S) space under the condition that (εS, χI, εI) → 0. Similarly, in (F, τ) space the differential equation Eq 2.9.3.6 can be written as follows.

| [2.9.3.11] |

Upon solving Eq 2.9.3.11 with the given initial condition and then reverting back to (V, τ) space using the transformation , one obtains the following integral solution corresponding to the reaction velocity in the pre-steady state regime.

| [2.9.3.12] |

This equation at τ → ∞ along with Eq 2.9.3.2 suggest the following expressions for the steady state timescale associated with the enzyme-substrate and enzyme inhibitor complexes under the conditions that (εI, χI, εS) → (0,0,0).

| [2.9.3.13] |

Clearly, common steady states between enzyme-substrate and enzyme-inhibitor complexes can occur only when the ratio in Eq 2.9.3.13 becomes as ξ ≅ 1 at which the error associated with various QSSAs will be at minimum. Upon solving the minimum error condition ξ ≅ 1 for βI, one obtains the following two possible roots.

| [2.9.3.14] |

When ηI → 0, then from Eqs 2.9.3.13 and 2.9.3.14 one finds the following expression for ξ.

| [2.9.3.15] |

When ηS ≅ 2χI, then Eq 2.9.3.15 suggests that the condition ξ ≅ 1 can be achieved by simultaneously settings sufficiently large values for any one of the parameters in the numerator (εI, κI) and any one of the parameters in the denominator (εS, χI, κS). When P, S and τ become sufficiently large, then Eqs 2.9.3.7 and 2.9.3.12 asymptotically converge to the following limiting value that is close to the steady state reaction velocity V associated with the partial competitive enzyme kinetics described in Scheme B of Fig 1 in the limit (εS, χI, κS) → (0,0,0). We denote this approximation as V3. We will show in the later sections that this approximation works very well in predicting the steady state reaction velocity of the partial competitive inhibition Scheme B over wide ranges of parameters.

| [2.9.3.16] |

In terms of original variables, Eq 2.9.3.16 can be written as follows.

| [2.9.3.17] |

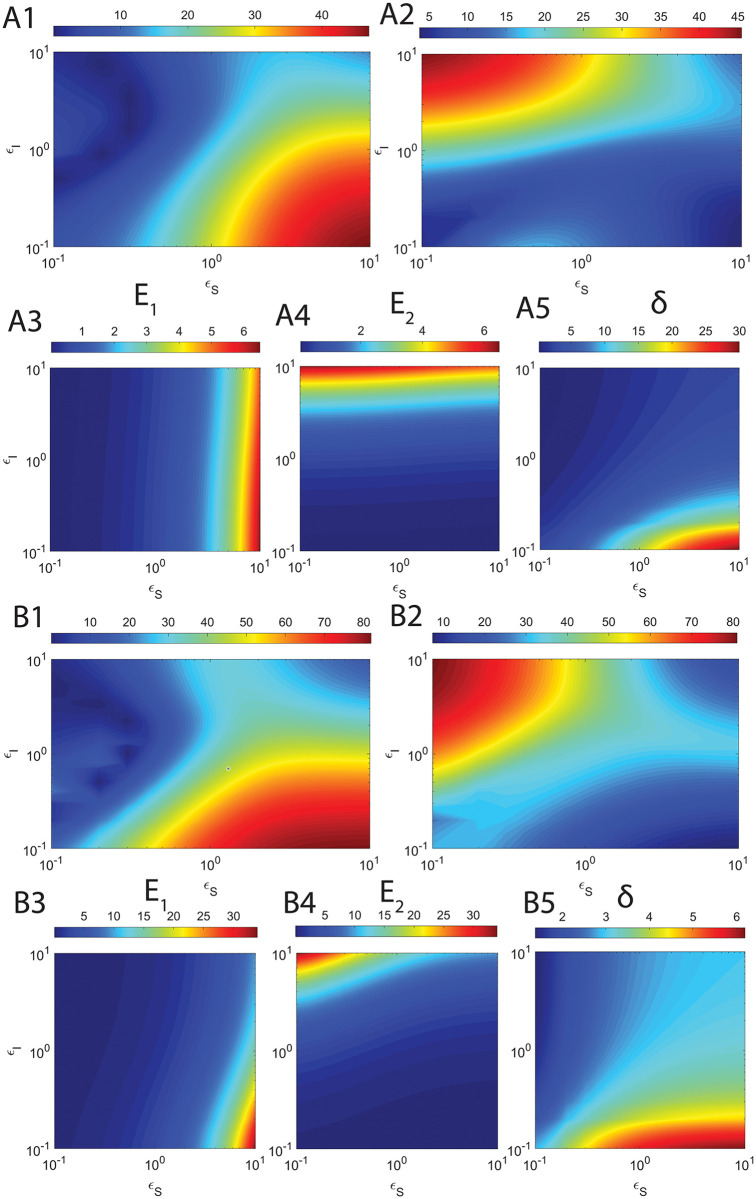

2.9.4. Error in the sQSSA of the partial competitive inhibition scheme

Similar to Eqs 2.7.1 and 2.7.2, the overall error in the refined form of sQSSA with stationary reactant assumption S ≅ 1 that is given in Eq 2.9.2.2 can be computed using the pre-steady state approximation given in Eq 2.9.3.12 as follows [40].

| [2.9.4.1] |

Here τCS is defined as in Eq 2.9.3.13. Upon solving for εS, one obtains the following expression for εS,max at which the error in the standard QSSA attains maximum. This means that the sufficient condition to minimize such error will be given as follows.

| [2.9.4.2] |

Inequality in Eq 2.9.4.2 (we denote this by E3) can be explicitly written in the following form.

| [2.9.4.3] |

Case IV: When (ηS, χI) → 0, then Eqs 2.9.1.3 and 2.9.1.4 reduce to the following form in the (V, Y, P) and (V, Y, S) spaces.

| [2.9.4.4] |

Upon using the mass conservation law P = 1 − V − S in Eq 2.9.4.4, one obtains the following.

| [2.9.4.5] |

| [2.9.4.6] |

Upon solving Eqs 2.9.4.4–2.9.4.6 for (V, Y), we can obtain the following expressions for V, P, Y and I in terms of S under the conditions that (ηS, χI) → (0,0).

| [2.9.4.7] |

In this equation . We will show later that Eq 2.9.4.7 can predict the post-steady state reaction velocity much better than Eq 2.9.2.2 in the (V, S) space. Noting that V + P + S = 1, one can derive the approximate expression for P in terms of S under the conditions that (ηS, χI) → (0,0) as follows.

| [2.9.4.8] |

Eqs 2.9.4.7 and 2.9.4.8 can be used to generate trajectories in the post-steady state of (V, P), (V, P, S) and (P, S) spaces in the parametric form where S ∈ [0,1] acts as the parameter. Upon solving Eqs 2.9.4.4–2.9.4.6 for Y, the post-steady state approximation in the (Y, S) space can be written as follows.

| [2.9.4.9] |

This equation is more refined one than Eq 2.9.12. Noting that I = (1 − εI Y), one can obtain the following approximate expression for the inhibitor concentration in terms of S corresponding to the post-steady state regime in (I, S) space.

| [2.9.4.10] |

In Eqs 2.9.4.8–2.9.4.10, h is defined as in Eq 2.9.4.7. Solutions obtained under the conditions that (ηS, χI) → (0,0) can approximate the original trajectory in the (V, S) space very well only in the post-steady state regime. By setting S → 0 in Eqs 2.9.4.9 and 2.9.4.10 representing τ → ∞, one obtains the exact equilibrium values of (Y, I) similar to Eq 2.9.12 as follows.

| [2.9.4.11] |

In terms of original variables, the steady state velocity approximation corresponding to the stationary reactant assumption S → 1 can be written from Eq 2.9.4.7 as follows.

| [2.9.4.12] |

Upon inserting the experimental values of e0 and i0 into this equation one can directly extract the values of KMS, KDI and vmax from the data on velocity v versus total substrate concentration s0 using non-linear least square fitting methods.

2.9.5. Steady state substrate and inhibitor levels

Similar to earlier studies [40], one can approximate the steady state substrate concentration by finding the intersection point between the pre- and post-steady state approximations in the (V, S) and (U, I) spaces. In case of partial competitive inhibition under the conditions that (ηS, χI, εS, εI) → 0, the steady state substrate level SC can be obtained by finding the intersection point between the pre-steady state approximation given by Eq 2.9.3.8 and the post steady state approximation given by Eq 2.9.2.2 in the (V, S) space as follows.

| [2.9.5.1] |

In this equation, left hand side is the post-steady state approximation and the right-hand side is the pre-steady state approximation, SC is the intersection point that approximates the steady state substrate concentration and, a and b are defined as in Eq 2.9.3.9. Upon expanding the right-hand side of Eq 2.9.5.1 in a Taylor series around SC = 1 and ignoring the second and higher order terms one finds the following equation for the intersection point between pre- and post-steady state solution in the (V, S) space.

| [2.9.5.2] |

Upon solving this quadratic equation for SC one obtains the following approximation for the steady state substrate level.

| [2.9.5.3] |

By substituting this expression of SC into the post-steady state approximation given in Eq 2.9.2.2, one can obtain the following expression for the steady state velocity VC.

| [2.9.5.4] |

Eqs 2.9.5.1–2.9.5.4 are valid only under the conditions that (ηS, χI, εS, εI) → 0. One can also substitute the approximate value of SC obtained from Eq 2.9.5.3, into Eq 2.9.4.7 to obtain a refined steady state velocity as follows.

| [2.9.5.5] |