Abstract

Development of effective therapeutics to prevent new infections with human immunodeficiency type 1 (HIV-1) is predicated on an understanding of the properties that provide a selective advantage to a transmitted viral population. In contrast to the homogeneous virus population that typifies early HIV-1 infection of men, the viral population in women recently infected with clade A HIV-1 is genetically diverse, based on evaluation of the envelope gene. A longitudinal study of viral envelope evolution in several women suggested that representative envelope variants detected at seroconversion had distinct biological properties that affected viral fitness. To test this hypothesis, a full-length, infectious molecular clone, Q23-17, was obtained from an infected woman 1 year following seroconversion, and chimeric viruses containing envelope genes representative of seroconversion and 27-month-postseroconversion populations were constructed. Dendritic cells (DC) could transfer infection of seroconversion variant Q23ScA, which dominated the viral population in the year following seroconversion, and the closely related 1-year isolate Q23-17 to resting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). In contrast, resting PBMC exposed to DC pulsed with Q23ScB, which was detected infrequently in samples after seroconversion, or the 27-month chimeras were inconsistently infected. Additionally, quiescent PBMC infected with Q23ScA or Q23-17 proliferated more robustly than uninfected cells or cells infected with the other envelope chimeras in response to immobilized anti-CD3. Stimulation with tetanus toxoid led to an increased proportion of CD45RA+ cells and a decreased expression of CD28 on CD45RO+ cells in cultures of Q23-17-infected PBMC. These data demonstrate that variants from the heterogeneous seroconversion clade A HIV-1 population in a Kenyan woman have distinct biological features that may influence viral pathogenesis.

The progression of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) from viral transmission to the onset of clinical disease is temporally variable but can be tracked by molecular and biological changes in the virus. Viral isolates obtained soon after infection typically infect primary monocytes in vitro without cytolysis (56, 59, 68, 76), whereas isolates obtained during the clinical phase of HIV-1 infection may cause syncytium formation and death in T-cell lines (58, 65, 66). Although cell killing is not a common feature of isolates obtained soon after primary infection, immunological defects in asymptomatic individuals have been well documented. Initially, CD4+ T cells from infected, asymptomatic persons fail to proliferate in response to recall antigens, and at later times, T-cell responses to additional stimuli are lost (11, 17, 26, 67). Alterations in immune function could be caused by virus-induced effects on either of the virus target cells, the CD4+ T cell or the antigen-presenting cell (APC). Data demonstrating that T-cell responses to recall antigen could be restored by treating cultures with anti-CD28 suggested that T-cell function was normal and that defects in APC function were the primary effectors of immune system dysfunction early during infection (26). These studies suggest that HIV-1 pathogenesis may also be monitored by studying sequential interaction with, and functional modification of, different immunologic cell lineages.

Sexual contact is a primary mode of transmission of HIV-1, indicating that viral target cells are present in genital mucosa (44). In situ studies of rhesus macaques infected vaginally with one simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) isolate demonstrated that virus-infected cells were present in vaginal epithelium (45) and that SIV localized to draining lymph nodes several days following virus exposure (62). The first cells to physically encounter HIV-1 that has been transmitted by sexual contact may be the most potent of APC for naive T cells, dendritic cells (DC). Langerhans cells within the epidermis represent one of the tissue-associated forms of DC. These cells are situated at epithelial surfaces to sample soluble antigens and then migrate via afferent lymphatics to draining lymph nodes to initiate an immune response (33, 64). Once DC have migrated to regional nodes, they produce chemokines that are specific for naive cells (1) and can cluster and activate naive cells in the absence of specific antigen (28, 50). Naive cells continuously migrate through lymph nodes, where they may be activated and differentiate into effector or memory cells if they encounter their cognate antigen. This circulation pattern for naive cells is in contrast to that of memory cells, which traffic primarily through tissues (2, 39, 40). Lymph nodes are known to be the site of active viral proliferation early in infection with HIV-1 (19, 48). Naive T cells in regional lymph nodes may, therefore, represent the majority of potential targets that a sexually transmitted virus will first encounter.

DC are well suited to enhance HIV-1 transfer to potential target lymphocytes because they express an array of adhesion and activation surface proteins that facilitate prolonged physical contact with T cells (22, 29). The importance of DC-T cell contact to support infection with HIV-1 has been documented in studies using cells derived from skin explants (50). In vitro, blood-derived DC pulsed with HIV-1 can also effectively transfer virus to T cells which have been mitogen stimulated (7, 49). It is unclear whether DC are infected with HIV-1 in vitro (7, 35, 38, 49), although infection of Langerhan cells and DC in situ has been demonstrated (10, 23, 32). Infection of DC is not required for DC-assisted infection of clustered T cells in vitro (7, 49); however, infection of unstimulated CD4+ cells in these assays requires that cultured DC display the appropriate activation phenotype (70). These data suggest that the normal physiological interaction of DC with naive T cells in draining lymph nodes can provide a mechanism to enhance virus replication in a new host and that infectability of DC-clustered T cells may be modulated by T-cell activation state.

The paradigm of early infection dynamics is based on cohorts that typically consist of men infected with clade B HIV-1. In these individuals, infection is most commonly initiated with a single virus (42, 71, 75, 76) which evolves under host-specific selection pressures into a diverse population of viral variants over time (14–16, 72). In contrast, the seroconversion viral population in African women infected with clade A and clade D HIV-1 is heterogeneous in envelope (31, 52). The natural history of clade A virus infection in several women indicated that envelope genes of the variant pool were under positive selection at seroconversion and throughout the approximate 2-year observation period. During this time, viral evolution progressed by sequential replacement of envelope variants in blood and mucosa (53). The longitudinal study on envelope evolution in these clade A-infected women raised several important questions. Do envelope variants that are present in women at seroconversion, which may differ in the envelope gene by up to 5%, have distinct biological properties that influence the course of infection of each variant? If envelope variants that are present at seroconversion do have unique biological features, how are these properties affected by selective pressures on envelope, which favored changes in protein sequence? In this study, we addressed these questions by determining the ability of each virus to infect resting or stimulated T cells in the presence of DC and by examining proliferative responses of infected T cells to different activation signals. Chimeric viruses containing envelope genes representative of viruses found at seroconversion (Q23ScA and Q23ScB), 1 year (Q23-17), and 27 months (Q23LC and Q23LD) of infection in subject Q23 were compared in each assay. Our data indicate that viruses representative of the diverse seroconversion population from one woman do have distinct biological properties which may contribute to the successful establishment of infection by some variants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Antibodies to the following cell surface markers were commercially obtained: CD4, CD25, CD40, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD54, CD86, and antitrinitrophenol (IgG1, κ isotype standard), obtained from PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.), and CD3, CD14, and HLA-DP, -DQ, -DR, obtained from Dako Corp. (Carpenteria, Calif.). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was obtained from Chemicon International, Inc. (Temecula, Calif.), interleukin-4 (IL-4) was from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.), and tetanus toxoid (TT; 2,600 Lf units/ml) was from Connaught Laboratories Ltd., Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Lectin-purified human IL-2 was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim.

Cloning of Q23-17.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from subject Q23 were obtained approximately 1 year following documented seroconversion. Cells were cocultured with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 0.5 μg/ml)-stimulated PBMC and were tested weekly for the presence of p24gag by antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Abbott Laboratories, Santa Clara, Calif.). Cultures were positive for p24gag antigen after 3 weeks, and an aliquot of tissue culture supernatant was used to infect 2 × 107 PHA-stimulated naive cells.

Infected cells were cultured for 12 days and collected by centrifugation, and genomic DNA was prepared by standard methods. Seventy-five micrograms of DNA was cut with HindIII, which cuts the viral genome once in the R region of the long terminal repeat (LTR), and was size fractionated on a 10 to 40% sucrose gradient. Fragments of between 7 and 10 kb were pooled and ligated into a HindIII-cut Lambda Zap vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Five million plaques were screened with 32P-labeled probes that recognized sequences in env and LTR of the Q23 virus, and five plaques reacted with both probes. These five were plaque purified, and the PBK-CMV phagemid was excised by using the ExAssist helper phage (Stratagene) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Two of the clones contained an insert that was 750 bp smaller than the others and were not included in further evaluation.

To reconstitute the LTRs, the viral genome was excised from the PBK-CMV phagemid with HindIII and circularized, and the LTR was amplified with primers binding in the 5′ portion of gag (5′-TCT AGC TCC CTG CTT GCC CAT ACT-3′) and 3′ portion of nef (5′-CAG GTA CCT TTA AGA CCA ATG A-3′). This fragment was blunt-end cloned into pBluescript II KS (pKS) in which the HindIII site had been removed. The pKS-LTR construct was cut with HindIII, and the full-length viral genome was ligated. Plasmids containing full-length virus in the correct orientation were transfected into 293T cells by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Stratagene). Two of the three clones were positive by p24gag antigen ELISA (Abbott) after 42 h.

Supernatant obtained from transient transfection of 293T cells (0.5 ml) with the two full-length clones was used to infect 5 × 106 PHA-stimulated PBMC. One day following infection, cells were harvested, washed once, and replated in RPMI containing 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) and IL-2 (10 U/ml). P24gag antigen was measured by ELISA (Abbott) on days 3 and 5 postinfection. Supernatants were collected after 5 days, titered by endpoint dilution on PHA-stimulated PBMC, aliquoted, and frozen at −70°F. The envelope genes of both clones were sequenced found to be identical; therefore, only one of the clones, Q23-17, was evaluated further.

Chimera construction.

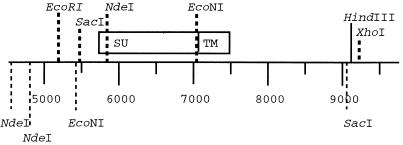

The 1.2-kb envelope fragments derived by nested PCR from PBMC, plasma, or cervical swabs were prepared in the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) as previously described (51). All subsequent Q23-17 subclones were made in pKS, and all plasmids were purified by passage through Qiagen miniprep filters (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). The restriction sites NdeI and EcoNI approximately flank the region encoding the gp120 portion of viral envelope. These sites appear three and two times, respectively, in the viral genome, which necessitated the use of two subcloning steps to incorporate representative gp120-encoding regions into the full-length genome. A 3′ subclone was first prepared by using the EcoRI site, which removed redundant upstream NdeI sites. To remove the redundant EcoNI site, the primary cloning vector was prepared by a partial digestion of the 3′ subclone with SacI to maintain the SacI site at position 9024 and with XhoI, which cut in pKS. The NdeI-EcoNI 1.2-kb fragment was ligated into this vector, and plasmids containing the insert were identified, propagated, and purified. Inserts were excised with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into the 3′ subclone. Inserts were excised from this vector with EcoRI and XhoI and ligated into the EcoRI- and XhoI-digested full-length Q23-17 genome. The position of each of these sites in the 3′ viral subclone is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Restriction site map of the 3′ subclone of Q23-17 used for Q23 envelope chimera construction. Restriction sites used in chimera construction are shown above the scale, and the positions of redundant sites are given below. The HindIII site in the LTR that was used to clone Q23-17 is shown. XhoI is located in the vector. The positions of gp120 (SU) and gp41 (TM) are indicated. The gene encoding gp120 is closely flanked by NdeI and EcoNI sites.

Viral stocks.

The source of each virus used for all experiments described in this report was a single-titered stock that was collected after 5 days of infection of PHA-stimulated PBMC with supernatant collected from transient transfection of 293T cells. Supernatants were collected after a short infection period to avoid adapting the virus to replication in activated lymphocytes. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was 105/ml for viruses Q23ScA, Q23-17, and Q23LC. Q23ScB stocks contained 5 × 104 TCID50/ml. These four chimeras were capable of infecting activated PBMC and producing more than 200 pg of p24gag per ml within 7 days when inoculated at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 (data not shown). Although supernatants from 293T cells transiently transfected with chimera Q23LD contained high levels of viral p24gag, inoculation of PBMC with Q23LD only sporadically resulted in production of infectious virus, and the TCID50 of this virus appeared to be 102. To determine if infection with this chimera had occurred, Q23LD-inoculated cells were lysed after 5 days, and samples corresponding to 10-fold dilutions of cells were evaluated for the presence of the viral gag gene in a nested PCR (30). At least 1 in 500 cells had detectable provirus by PCR when cells were inoculated with an MOI of 0.001. An envelope gene obtained from Q23 PBMC samples that was identical to Q23LD in the V1, V2, and V3 regions was used to generate an alternative chimera, and this virus was replication defective. Q23LD-infected cells were included in all experiments and may serve as a control for nonproductively infected cells. None of the Q23 envelope chimeras produced any in vitro cytopathology in primary lymphocyte cultures, as would be indicated by a decrease in cell numbers or visible signs of cell fusion, fragmentation, or death.

Sequencing and characterization of chimeras and full-length Q23-17.

The region encoding gp120 from each chimera and the entire Q23-17 genome were sequenced with an ABI model 377 sequencer at MacroMolecular Resources, Fort Collins, Colo. Isoelectric points were determined empirically for the SU portion of each chimera as described elsewhere (3, 5). Pairwise distances for predicted amino acid sequences were determined with MEGA (34).

Preparation of DC.

Lymphocytes were obtained from whole blood by gradient separation on lymphocyte separation medium (Organon Teknika Corp., Durham, N.C.). Cells at the interface were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; GIBCO BRL). DC were enriched as described previously (55). Briefly, 100 × 106 to 300 × 106 cells were plated in T75 flasks (Corning, Inc., Corning, N.Y.) in RPMI–5% FCS for 2 h. Nonadherent cells, which constituted the autologous PBMC fraction used in experiments, were recovered by gently washing flasks with PBS, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in RPMI containing 10% FCS with or without IL-2 (10 U/ml). Remaining adherent cells were the source of DC and were fed with RPMI containing 10% FCS, IL-4 (33 ng/ml), and GM-CSF (50 ng/ml). Media were replenished on both enriched DC cultures and adherent cell-depleted PBMC 3 to 4 days following separation. After 1 week in culture with GM-CSF and IL-4, DC had attained a characteristic appearance of nonadherent, large “veiled” cells. These cells had the phenotype CD4+ HLA-DR,DQ,DP+ CD56+ CD86+ CD40+ CD3− CD14− by flow cytometry (FacScan, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) and, in most experiments, constituted greater than 90% of the cell population after 1 week of culture. Contaminating cells were CD3+ and were distinguished from DC by forward and side light scattering profiles.

Pulse inoculation of DC and autologous PBMC.

For virus pulse inoculation experiments, DC were prepared as described above. Autologous PBMC recovered following adherent cell depletion were either maintained in the absence of IL-2 and mitogen (resting) or stimulated with PHA in the presence of IL-2 (10 U/ml) (stimulated), washed twice in PBS after 24 h stimulation to remove PHA, and maintained in RPMI containing 10% FCS with IL-2 (10 U/ml) for 3 to 5 days prior to the experiment. For pulse inoculation, stimulated and resting PBMC and autologous DC were independently incubated with an MOI of 0.001 (MOI of 0.005 in experiment 5) of each virus stock for 1 h at 37°C and then washed twice with PBS. Pulse-inoculated, resting, or stimulated PBMC were plated in 24-well dishes at 5 × 105/well in the absence of DC. Pulse-inoculated DC were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well either alone or with 5 × 105 stimulated or resting PBMC that had not been pulse exposed to virus. Supernatants were evaluated for the presence of p24gag antigen by ELISA (Abbott) on days 3 and 5 postinoculation. The experiment was repeated five times with cells from different donors.

Proliferation of resting PBMC to immobilized anti-CD3.

PHA-stimulated PBMC were infected with an MOI of 0.0005 to 0.001 of each virus for 24 h. Cells were washed twice in PBS and maintained in culture for 3 to 5 days in RPMI containing 10% FCS but no IL-2. Virus infection was confirmed by detection of p24gag antigen by ELISA. Cells were washed, resuspended in fresh RPMI with 10% FCS, and plated in triplicate at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates coated with 500 ng of anti-CD3 or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per well. After 5 days, proliferation was evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (CellTiter 96 AQueous; Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Background levels were determined from the average absorbancy at 490 nm (optical density [OD]) of the triplicate wells containing goat anti-mouse IgG for each infected or uninfected cell culture. A stimulation index (SI; equivalent to ODCD3/ODIgG) was calculated for each experiment. In this colorimetric assay, the maximum SI was 2.7 because the highest readable OD was 1.9 and the average OD for cells plated on IgG was 0.7. All assays were repeated four times with cells from different donors. Results are shown as the mean and standard error of the SI from the four replicate experiments. Statistical differences between the SI of virus-infected cells and uninfected cells were determined by Student’s t test.

Response of infected PBMC to tetanus toxoid.

PBMC were infected with an MOI of 0.0001 of each viral chimera and were maintained for 5 days in the absence of IL-2 as described above. To evaluate response to a recall antigen, TT (50 Lf units/ml) was incubated with 2 × 104 autologous DC for 2 h at room temperature. DC were washed once in PBS and plated in six-well plates with 2 × 106 infected PBMC. After 5 days, cells were harvested and washed. Monoclonal antibodies were added to 106 cells, and cells were incubated on ice for 1 h. Cells were washed twice in PBS and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Phenotype was assessed by one- and two-color flow cytometry. Twenty thousand events were counted. The experiment was repeated three times with cells from different donors.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The Q23-17 sequence is deposited in GenBank with accession no. AF004885.

RESULTS

Evolutionary relationship of Q23 variants.

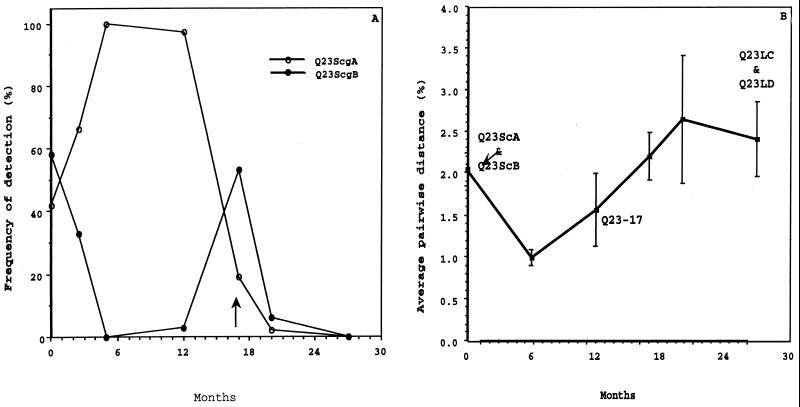

Representative envelope genes used for chimera construction were chosen from among 185 sequences recovered from plasma, PBMC, and cervical swabs over a 27-month period from subject Q23. Phylogenetic relationship based on the sequence of the V1, V2, and V3 regions of envelope of all sampled Q23 viruses suggested that sequences clustered by sample date (53). Based on pairwise distance analysis of the 31 sequences from the seroconversion sample, two dominant genotypes, seroconversion groups A (ScgA) and B (ScgB), were identified. Envelope gene sequences within both ScgA or ScgB differed, on average, by 1.1% (0.85 and 0.74%, respectively, for plasma viral sequences), but the difference between sequences from ScgA and ScgB was, on average, 2.9% (2.7% for plasma viral sequences). The sequence that was chosen as representative of each group of related variants contained the most prevalent amino acid at all positions, determined by comparing all sequences in the group, and are referred to as Q23ScA and Q23ScB. Variants from ScgA and ScgB were present in all tissue compartments near seroconversion, but ScgB variants were more commonly found in proviral DNA from PBMC and cervical samples than in plasma viral RNA (53). The frequency of ScgA and ScgB detection at each sample point throughout the 27-month study is shown in Fig. 2A.

FIG. 2.

Changes in genetic diversity in envelope sequences sampled from subject Q23 during the 27 months following detection of seroconversion. Sequences used in this analysis are described in reference 53. (A) Percentage of Q23ScgA and Q23ScgB sequences detected in the total virus population at each sample point. Time is indicated in months from the seroconversion sample. Nucleotide sequences of variants within each group differed, on average, by 1.1% from other sequences in the group. For the first 17 months, all sequences could be classified as Q23ScgA or Q23ScgB. At 17 months postseroconversion (indicated by the arrow), sequences containing V1 insertions were first noted. After this time point, Q23ScgA or Q23ScgB sequences were infrequently detected. (B) Percent average pairwise distance of all sequences detected at each sample point. Error bars show standard deviations. Time points where envelope sequences were recovered that were used to construct viral chimeras described in this report are indicated.

The full-length proviral clone was obtained from Q23 PBMC sampled approximately 1 year after seroconversion was detected when ScgA variants comprised 29 of the 30 sequences evaluated. The average pairwise distance between the envelope gene of Q23-17 and all other plasma viral envelope gene sequences detected at the 1-year sample point was 1.0% (standard deviation = 0.4), indicating that the envelope gene of the clone was representative of circulating virions from that time point. With one exception, all amino acid differences among plasma viral sequences detected in the sample taken at this time point occurred in V2.

At the last sample point, approximately 27 months postseroconversion, most envelope sequences had evolved by insertions of variable length in V1. Variation in V1 was too extensive to generate a consensus among the 28 sequences evaluated at this time point. Sequences, therefore, were grouped by the length of the V1 insert, and sequences with the longest (Q23LC) and shortest (Q23LD) V1 insert were selected for evaluation in this study. Q23LC and Q23LD contained consensus amino acids at positions in V2 and V3 compared to other sequences in their V1 length groups. The sample from which each viral envelope was recovered, and the average pairwise distance of the V1, V2, and V3 portions of the envelope gene for the entire viral population detected at each time point is shown in Fig. 2B. The distance relationships for the five viruses evaluated in this report, based on amino acid sequence of the gp120 portion of envelope, are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Pairwise distance comparison of Q23 viral chimera envelope sequences

| Virus | % Different sitesa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q23ScA | Q23ScB | Q23-17 | Q23LC | Q23LD | |

| Q23ScA | 3.41 | 2.97 | 8.05 | 6.60 | |

| Q23ScB | 4.70 | 9.49 | 6.83 | ||

| Q23-17 | 8.40 | 6.19 | |||

| Q23LC | 8.47 | ||||

| Q23LD | |||||

Proportion of sites that differed between the predicted amino acid sequence of envelope of each pair of chimeras.

Comparison of envelope biochemical properties.

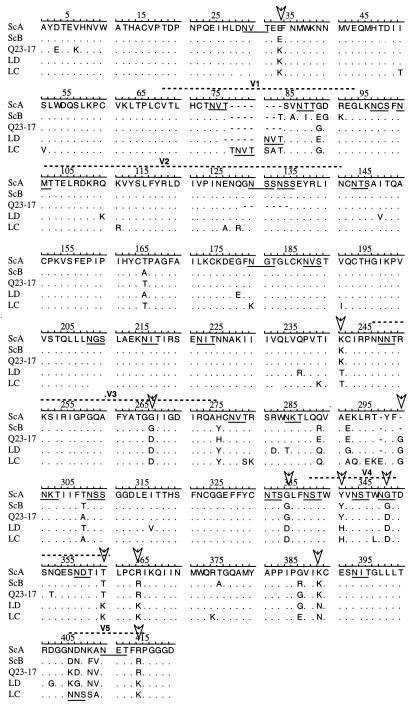

Evolutionary analysis of envelope sequences from Q23 indicated that there was selection for change in protein structure over time (53). Indeed, biochemical characteristics of the five viral envelope sequences suggested that temporal changes in properties of this protein may have occurred. Over time, the predicted isoelectric point of the envelope protein decreased from 8.26 (Q23ScB) or 8.10 (Q23ScA and Q23-17) to 7.88 (Q23LC and Q23LD). There were 56 amino acid positions, excluding insertions and deletions of more than two amino acids, that varied among the five envelope sequences (Fig. 3). At 34 of these positions, four of the five sequences were identical. Eleven of the remaining sites contained an amino acid that was shared between the seroconversion variants and a different amino acid that was common to the late variants. Clone Q23-17, which was isolated at an intermediate time point, was similar to either the seroconversion or 27-month variants at these 11 positions, suggesting that sequential fixation of amino acids occurred at these sites during envelope evolution.

FIG. 3.

Sequence comparison of Q23 envelope chimeric viruses. Sequences for the region of the envelope gene spanning the NdeI and EcoNI sites are shown in single amino acid code. Regions of sequence homology are indicated by dots. At positions where sequences differ, the nonhomologous amino acid is shown. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites are underlined. Arrows indicate positions where the two seroconversion sequences have a common amino acid and the two 27-month sequences share a different amino acid. Clone Q23-17, which was isolated at an intermediate time point, is similar to either seroconversion or 27-month sequences at these positions.

Twenty-three of the twenty-four potential N-linked glycosylation sites were conserved between the two seroconversion variants, Q23ScA and Q23ScB (Fig. 3). Compared to Q23ScA, there were two potential N-linked glycosylation sites (positions 129 to 135) lost in the V2 deletion in Q23-17. Two potential N-linked glycosylation sites were gained (positions 78 to 80 and 405 to 407) and one was lost (positions 180 to 182) in Q23LC relative to Q23ScA. The V1 potential N-linked glycosylation site in Q23LD was moved C terminally to positions 81 to 83, and one site after the V3 loop was lost (positions 284 to 286). Variation in location and number of potential glycosylation sites, a decrease in isoelectric point, and sequential fixation of amino acids at specific positions, therefore, characterized changes that developed in the envelope glycoprotein of Q23 viral populations during the first 27 months of asymptomatic infection in this subject.

Infection of resting lymphocytes via virus-pulsed DC.

It has been suggested that the principal limiting factor for HIV-1 replication is availability of target cells (12). A virus that has been transmitted by sexual contact may have a distinct advantage in establishing infection in a new host because of initial interaction with DC which can bring a new virus into close proximity with numerous susceptible target cells in draining lymph nodes. The ability of each of the Q23 chimeric viruses to infect either resting or mitogen-stimulated T cells following a pulse exposure of virus to autologous DC was determined (Table 2). Resting lymphocytes were infected from DC that had been exposed for 1 h to Q23ScA in four of five experiments, but seroconversion variant Q23ScB was unable to establish infection in quiescent lymphocytes under these conditions. The 1-year clone, Q23-17, was the most efficient in establishing infection in resting lymphocytes via virus-pulsed DC. The 27-month variant with the longest V1 insert, Q23LC, inconsistently infected quiescent lymphocytes exposed to virus-pulsed DC. If lymphocytes were preactivated with mitogen, however, infection of cultures was initiated by DC that were pulsed with Q23LC, as well as with Q23-17 and Q23ScA, in all five replicate experiments. Q23ScB was less efficient (positive in three of five experiments) in infecting activated PBMC that contacted virus-pulsed DC. Q23LD was able to infect only cells from donor 1, and infection was not dependent on lymphocyte activation state. With the exception of PBMC from donor 4, pulse exposure of resting or stimulated PBMC in the absence of DC or of DC alone to Q23 viruses did not result in infection (data not shown). Thus, DC exposed to Q23ScA, but not Q23ScB, were able to transfer infection to quiescent lymphocytes. The isolate recovered at 1 year following seroconversion, Q23-17, also was capable of initiating infection in resting cells via DC, suggesting that this feature was maintained in the virus populations that evolved during the first year of infection.

TABLE 2.

Infection of lymphocytes following pulse exposure of enriched DC to Q23 envelope chimeric virusesa

| Cells | p24gag concnb

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC + PBMC (resting)

|

DC + PBMC (stimulated)

|

|||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Q23ScA | ++ | − | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Q23ScB | − | − | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | − | + |

| Q23-17 | ++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++++ | ++ | ++ |

| Q23LC | ++ | − | − | + | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Q23LD | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

DC and autologous resting or PHA-stimulated PBMC were prepared as described in the text. DC were pulsed with a virus chimera for 1 h, washed, and plated with a 10-fold excess of uninfected resting PBMC or PBMC that had been PHA stimulated 3 days earlier. Infection was monitored by p24gag ELISA 5 days after the virus pulse.

Categorized as 25 to 50 (+), 50 to 100 (++), 100 to 200 (+++), and >200 (++++) pg/ml. Results from each of five replicate experiments are shown.

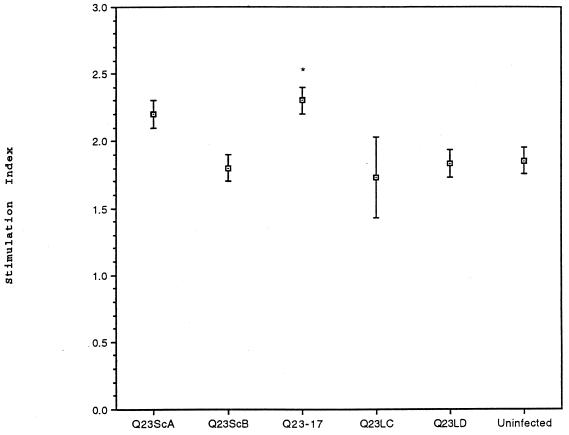

Proliferation of infected, resting PBMC in response to CD3 ligation.

To determine if virus infection affected activation of quiescent T cells, we evaluated the proliferative ability of infected, resting PBMC following ligation of CD3. The four replicate assays were performed in the absence of exogenous IL-2 (Fig. 4). Resting cells infected with Q23-17 proliferated significantly greater in response to CD3 ligation than did uninfected cells. Q23ScA-infected cells tended to proliferate better than uninfected cells, but significant differences in the cumulative SI between these two cultures were not strongly supported (P < 0.09). The difference in proliferation between Q23ScA-infected cells and cells nonproductively infected with Q23LD was, however, significant (P < 0.05). There was no evidence of proliferation enhancement in cells infected with Q23ScB, Q23LC, or Q23LD. Q23LC-infected PBMC demonstrated variable proliferative responses to a CD3-mediated signal in the four experiments, suggesting that host cell factors may have contributed to virus-induced enhanced proliferation. There was no correlation between p24gag concentrations of cells infected with the different viruses and the ability of those cells to proliferate either within an experiment or among the four replicate experiments. Infected cells were also evaluated for proliferation to TT. The response of cells infected with each Q23 virus was similar to the proliferation of uninfected cells (data not shown), although it is possible that the MTT assay was not sensitive enough to detect small differences in cell numbers. Thus, the ability of a Q23 virus to induce proliferation of resting, infected cells following CD3 ligation paralleled the ability to infect resting T cells following pulse exposure to DC.

FIG. 4.

Response of PBMC infected with Q23 envelope chimeric viruses to immobilized CD3 antibody. PBMC were isolated from whole blood, stimulated with PHA, and infected as described in the text. Cells were rested for 3 to 5 days in the absence of IL-2, and 5 × 104 cells were transferred to wells containing immobilized antibody to CD3 or IgG. After 5 days, plates were monitored for cell proliferation by the MTT assay. Results are shown as the mean and standard error of the SI (SI = ODCD3/ODIgG) for each of four replicate experiments. With the colorimetric assay, the maximum SI in these experiments was 2.7 (see Materials and Methods). Statistical significance between virus-infected cells and uninfected cells was determined by Student’s t test and is indicated by ∗ (P < 0.05). Cells infected with Q23ScA proliferated significantly better than did Q23LD-infected cells (P < 0.05), but the proliferative difference between Q23ScA-infected and uninfected cells was not highly significant (P < 0.09).

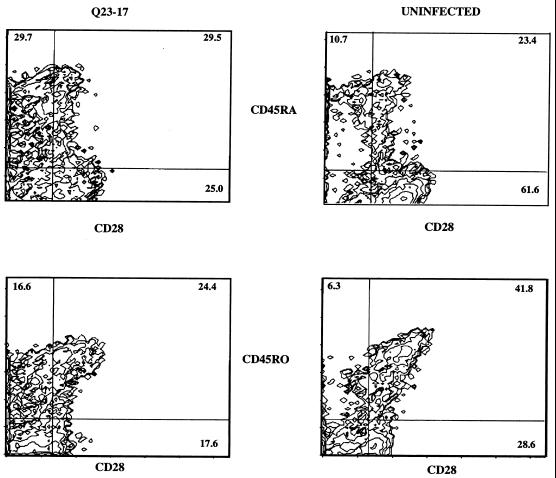

Cell phenotypic analysis of resting, infected cells in response to recall stimulus.

Prior to the onset of clinical disease or decline of CD4+ cells, cells from infected individuals may lose the ability to respond to recall antigens. We therefore explored the response of cells infected with each Q23 virus to stimulation with TT in more detail by monitoring surface phenotype with flow cytometry. In the three replicate experiments, there was on average 52% more CD45RA+ cells in Q23-17-infected cultures stimulated with TT than in uninfected cultures (Table 3). Cells infected with either of the seroconversion variants responded with a moderate expansion of CD45RA+ cells. Typical of observations in the other assays, cultures infected with Q23LC demonstrated a variable range of results. In one experiment, the proportion of CD45RA+ cells from Q23LC-infected cultures was increased 54% compared to uninfected cultures, but in two other experiments, this difference was less than 20%. Q23LD-infected cultures stimulated with TT were similar to uninfected cultures in cell surface phenotype in all experiments.

TABLE 3.

Effect of virus infection on surface expression of CD28 and on CD45 subtype distributiona

| Virus | Mean % differenceb (SD)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45RA | CD45RO | CD28 | CD45RA CD28 | CD45RO CD28 | |

| Q23ScA | 32 (13) | −5 (7) | −12 (9) | 22 (14) | −22 (15) |

| Q23ScB | 33 (11) | −4 (5) | −10 (13) | 16 (15) | −15 (2) |

| Q23-17 | 52 (24) | −16 (5) | −33 (10) | 14 (6) | −39 (8) |

| Q23LC | 32 (22) | −12 (4) | −13 (10) | 16 (20) | −23 (10) |

| Q23LD | 2 (3) | −1 (3) | −3 (8) | 9 (22) | −3 (8) |

Infected, resting PBMC were exposed to TT-pulsed DC, and surface phenotype was determined by flow cytometric analysis 5 days following stimulation.

Percent difference in infected cells compared to the number of uninfected cells expressing each surface marker for three replicate experiments.

Q23-17-infected PBMC also displayed less CD28, an important costimulatory molecule, following exposure to TT than did uninfected cells. The proportion of CD45RA+ CD28+ cells in Q23-17-infected cultures was similar to that found in uninfected cultures; however, the level of CD28 on CD45RO+ cells from Q23-17-infected cultures was decreased, on average, 39% (Table 3; a representative experiment is shown in Fig. 5). Expression of CD25 on CD45RA+ and CD45RO+ cells in all virus-infected cultures was similar to that in uninfected cells (data not shown). Therefore, the response of Q23-17-infected lymphocytes to a recall antigen was qualitatively distinct from the response of uninfected cells, although the number of total proliferating cells did not differ substantially between these cell cultures.

FIG. 5.

Phenotypic changes in cells infected with Q23-17 in response to stimulation with TT. Data shown are representative of the three replicate experiments summarized in Table 3. PBMC were PHA stimulated, infected at an MOI of 0.0001, and rested for 5 days as described in the text. DC were pulsed with TT and added to autologous infected PBMC at a ratio of 1:100. Following an additional 5 days of culture, cells were collected, washed, stained with monoclonal antibodies to CD45RA or CD45RO (phycoerythrin conjugated) and CD28 or CD25 (fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated), and evaluated by flow cytometry. Numbers in the diagrams indicate the proportion of positive cells in each quadrant; the proportion of double-positive cells is indicated in the upper right quadrant.

DISCUSSION

It is important to understand properties that confer fitness on viruses infecting a new host. In women infected with a heterogeneous population of clade A HIV-1, the history of viral evolution provided insight as to the relative fitness of the initial population (53). Diverse envelope genotypes represented by clones Q23ScA and Q23ScB were present at seroconversion in subject Q23, but by 6 months after seroconversion only variants similar to Q23ScA were detected and overall genetic diversity had commensurately decreased. Properties conferred by the envelope gene that might be important in virus colonization could, therefore, be identified by comparing attributes of clones Q23ScA and Q23ScB. DC that were briefly exposed to virus could facilitate infection of resting T cells by Q23ScA but not Q23ScB. In addition, quiescent cells infected with Q23ScA, but not Q23ScB, tended to proliferated more robustly than did uninfected cells following ligation with antibody to CD3.

At 1 year of infection, the genetic diversity of the virus population was increasing from the 6-month postseroconversion selection event and consisted of variants more similar to Q23ScA than to Q23ScB. At each sample point throughout this time, sequences from the PBMC and mucosal proviral population were phylogenetically distinct from sequences obtained at the previous time point (phylogenetic temporal structure) (53). Sequences derived from sequential samples of the plasma viral pool had, however, not developed phylogenetic temporal structure, suggesting that the plasma virus population was well adapted to the host during this time period. Mutations arising in a highly fit population would tend to decrease population fitness and be removed by purifying selection. Consistent with these evolutionary data, the prototype clone, Q23-17, derived a year after seroconversion retained the features of the dominant seroconversion variant, Q23ScA, in DC pulse infection and CD3-induced proliferation experiments.

By 27 months postseroconversion, insertions in V1 were evident in the majority of envelope sequences obtained from all tissues. To determine if insertional events in V1 affected properties that had persisted throughout the first year of virus infection, envelope sequences from this time point that had variable-length V1 insertions were selected for evaluation. Compared to Q23ScA, Q23LC and Q23LD had a seven- and a two-amino-acid insertion in V1, respectively. In general, cells could be infected with Q23LD but did not produce infectious virions. Q23LC could not consistently infect resting lymphocytes from different donors in the DC pulse experiment or cause enhanced proliferation of infected cells following CD3 ligation. Thus, mutations in the envelope gene of the 27-month variants did affect the ability of those viruses to infect and enhance the proliferation of resting cells.

In our assays, Q23ScA and Q23-17 had very similar properties, but data obtained with cells infected with Q23-17 were more consistent and pronounced. Q23-17 may be the result of selection for a highly fit genotype during the first year of infection of subject Q23. This possibility is supported by our evolutionary data that envelope sequences from plasma viral RNA in subject Q23 did not change substantially during the first year of infection (53). It should also be considered, however, that results were more remarkable with this virus because it was not chimeric in the polyprotein encoding the envelope glycoprotein. The evolution of gp120 and the transmembrane glycoprotein, gp41, may occur in concert, and the unnatural association of these two glycoproteins in the chimeric viruses may have influenced the results of our assays. With the exception of Q23LD, however, all of the viruses demonstrated similar replicative abilities in stimulated cells, suggesting that properties described in this report were sensitive to substitutions in gp120 and were not solely derived from an altered interaction of gp120 with gp41.

Our data indicate that variants which dominated the Q23 virus population during the first year of infection could infect resting lymphocytes exposed to virus-pulsed DC and could increase the proliferative capacity of infected cells. Others have reported that efficient infection of PBMC following a DC pulse with HIV-1 is enhanced by cell activation (49, 69, 70). In these studies, however, changes in the cell activation state was due to in vitro manipulation. In fact, most experiments investigating the role of blood-derived DC in transferring HIV-1 infection to lymphocytes have used cell line-adapted viruses and stimulated PBMC. Virus-cell interactions that effect a change in cell activation may be difficult to discern by using viruses adapted to rapidly growing cell lines and if cell lines or mitogen-stimulated primary cells are the susceptible target cell. Additionally, the Q23 chimeric viruses and clone used in these studies may be more characteristic of viruses found in the initial stages of infection because they represent the actual viral envelope genes or virus that were dominant in the host in the 2-year period following seroconversion.

Lymphocyte function abnormalities are some of the first clinical manifestations detected in HIV-infected individuals and are frequently manifest as depressed responses to recall antigen stimulation (11, 26). None of the Q23 viruses inhibited general proliferation of infected cells to CD3 ligation or to TT. In cells infected with Q23-17, however, proliferation in response to this recall antigen occurred primarily in the CD45RA+ lymphocyte subset, and cells bearing the memory phenotypic marker, CD45RO, decreased the expression of the accessory activation surface protein, CD28. This was an unexpected response because in uninfected PBMC, CD45RO+ cells generally proliferate in this assay and have an elevated level of CD28 compared with naive cells (24). In the presence of DC, however, CD45RA+ cells are capable of a vigorous response to soluble antigen in vitro (13) and can preferentially proliferate over CD45RO+ cells in response to a new antigen, such as HIV gp120 (43) or malarial circumsporozoite proteins (20). In addition, the CD45RA+ subset of cells can also respond more vigorously to plate-bound anti-CD3 if costimulation through accessory molecules occurs (18, 54). It is possible, therefore, that the atypical responses that we observed in our assay resulted from virus-induced effects on CD45RA+ cells. Furthermore, our in vitro data with Q23 viruses are mirrored by clinical profiles of some asymptomatic HIV-1-infected individuals who have an increase in the number of CD45RA+ cells (25), although this is not a consistent clinical finding (6, 41). Similarly, an increased incidence of CD28− cells in the CD45RO+ memory subset has been observed in some HIV-1 patients in the absence of clinical disease symptoms (4).

The role that T-cell subsets play in HIV-1 pathogenesis has recently received significant attention. In vivo, HIV-1 replication is augmented after vaccination or exposure to other infectious agents (47, 63). Enhanced viral replication in response to recall antigens is consistent with reports that productive HIV-1 infection in vitro resides in the CD45RO subset (54, 61, 74). Despite being able to mount a vigorous proliferative response, CD45RA+ cells infected in vitro do not support productive HIV infection or support infection at a significantly decreased rate relative to CD45RO+ cells (54, 61, 74). Infected CD45RA+ cells are, however, detected in vivo (57), and CD45RA+ cells derived from asymptomatic individuals do produce virus in response to CD3-mediated activation but not to mitogen stimulation (8). Significantly, neonates who rapidly progress to AIDS have high proviral levels in CD45RA+ cells (60).

Data from cells infected in vivo and in vitro can be difficult to reconcile. Whereas vaccination may enhance HIV-1 replication in vivo, virus production in cells derived from infected individuals is inhibited following stimulation in vitro with immobilized antibodies to CD3 and CD28 (37). Costimulatory signals involving CD28 appear to be a critical determinant in establishing a virus-susceptible or virus-resistant state in infected cells. Stimulation with antibody to CD28 can enhance HIV expression of in vitro-infected cells if CD28 is presented in soluble form (49) or can lead to a virus-resistant state if CD28 is immobilized (37). It appears, therefore, that both CD28 and CD45 subsets may play significant roles in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Because the primary Q23-17 clone differentially affects both CD28 expression and CD45 subset distribution following T-cell stimulation, it may be useful in delineating the mechanism by which these molecules contribute to immune system dysfunction in an HIV-1-infected individual.

Although evolution of retroviruses and other RNA viruses can occur in the absence of an immune response (36, 46), it is clear that the immune system of the host provides a strong selective pressure on retroviruses. We have shown that the two major variants present in the seroconversion sample have different properties, but we cannot determine if fitness differences alone were responsible for the subsequent evolution of the virus population, because we have no data on the host immune response during this time period. Subject Q23 maintained a plasma viral burden which was, on average, 106 particles/ml throughout the 27-month period examined (53). If a cytotoxic cellular immune response occurred to either Q23ScA or Q23ScB variants following viral transmission, it was not adequate to eliminate either prior to seroconversion. We cannot rule out, however, that the decline in Q23ScgB variants after seroconversion resulted from an effective humoral or cellular immune response against that group of variants. Interestingly, Q23ScgB sequences were identified again in plasma 17 months after the seroconversion sample, which correlated with the time that insertional changes in V1 were first detected in the viral population. The reappearance of Q23ScgB variant genotypes in plasma is consistent with the observation that T cells harbor latent virus for prolonged periods and virus expression can occur following appropriate stimulation (21, 73). It is plausible that reexpression of a latent reservoir of Q23ScgB variants at 17 months activated the cellular or humoral arm of the immune system, which influenced subsequent viral evolution. Changes in V1 to include new N-linked sites may have resulted from antibody selection pressure, as has been demonstrated for infections with both SIV and HIV (9, 27). It should be considered, therefore, that viral pathogenesis in women, who, unlike men, may harbor a heterogeneous population of virus at seroconversion, may proceed differently during the first years of virus infection due to the interplay between genetically and biologically distinct viral variants that respond to different selective forces imposed by the host environment. A better understanding of properties that allow colonization of transmitted viruses and of the selective pressures that act on heterogeneous virus populations adapting to a new host will increase the potential to develop regionally and globally effective antiviral therapeutics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gerald Learn and Nordin Zeidner for critical reviews of the manuscript, Eric Finn for assistance with lymphocyte preparation, and Joan Kreiss, Harold Martin, Jr., and collaborators at the Ganjoni Municipal Clinic and Coast Provincial General Hospital, Mombasa, Kenya, for sample collection.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants AI38518 and AI27757 (UW CFAR). M.P. was supported by NIH fellowships AI07140 and AI01290.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adema G J, Hartgers F, Verstraten R, de Vries E, Marland G, Menon S, Foster J, Xu Y, Nooyen P, McClanahan T, Bacon K B, Figdor C G. A dendritic-cell-derived C-C chemokine that preferentially attracts naive T cells. Nature. 1997;387:713–717. doi: 10.1038/42716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ager A. Trafficking. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:421–428. doi: 10.1042/bst0250421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjellqvist B, Hughes G J, Pasquali C, Paquet N, Ravier F, Sanchez J-C, Frutiger S, Hochstrasser D F. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501401163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borthwick N J, Bofill M, Gombert W M, Akbar A N, Medina E, Sagawa K, Lipman M C, Johnson M A, Janossy G. Lymphocyte activation in HIV-1 infection. II. Functional defects of CD 28- T cells. AIDS. 1994;8:431–441. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brendel V, Bucher P, Nourbakhsh I, Blaisdell B E, Karlin S. Methods and algorithms for statistical analysis of protein sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2002–2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruunsgaard H, Pedersen C, Scheibel E, Pedersen B K. Increase in percentage of CD45RO+/CD8+ cells is associated with previous severe primary HIV infection. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:107–114. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199510020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron P U, Freudenthal P S, Barker J M, Gezelter S, Inaba K, Steinman R M. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science. 1992;257:383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.1352913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cayota A, Vuillier F, Scott-Algara D, Feuillie V, Dighiero G. Differential requirements for HIV-1 replication in naive and memory CD4 T cells from asymptomatic HIV-1 seropositive carriers and AIDS patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chackerian B, Rudensey L M, Overbaugh J. Specific N-linked and O-linked glycosylation modifications in the envelope V1 domain of simian immunodeficiency virus variants that evolve in the host alter recognition by neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 1997;71:7719–7727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7719-7727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cimarelli A, Zambruno G, Marconi A, Girolomoni G, Bertazzoni U, Giannetti A. Quantitation by competitive PCR of HIV-1 proviral DNA in epidermal Langerhans cells of HIV-infected patients. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clerici M, Stocks N I, Zajac R A, Boswell R N, Lucey D R, Via C S, Shearer G M. Detection of three distinct patterns of T helper cell dysfunction in asymptomatic, human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1892–1899. doi: 10.1172/JCI114376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffin J M. HIV pathogenesis. Lines drawn in epitope wars. Nature. 1995;375:534–535. doi: 10.1038/375534a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croft M, Duncan D D, Swain S L. Response of naive antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro: characteristics and antigen-presenting cell requirements. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1431–1437. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delwart E L, Pan H, Sheppard H W, Wolpert D, Neumann A U, Mullins J I. Slower evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 quasispecies during progression to AIDS. J Virol. 1997;71:7498–7508. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7498-7508.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delwart E L, Sheppard H W, Walker B D, Goudsmit J, Mullins J I. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution in vivo tracked by DNA heteroduplex mobility assays. J Virol. 1994;68:6672–6683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6672-6683.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delwart E L, Shpaer E G, Louwagie J, McCutchan F E, Grez M, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Mullins J I. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolan M J, Clerici M, Blatt S P, Hendrix C W, Melcher G P, Boswell R N, Reeman T M, Ward W, Hensley R, Shearer G M. In vitro T cell function, delayed-type hypersensitivity skin testing, and CD4+ T cell subset phenotyping independently predict survival time in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:79–87. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubey C, Croft M, Swain S L. Naive and effector CD4 T cells differ in their requirements for T cell receptor versus costimulatory signals. J Immunol. 1996;157:3280–3289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Embretson J, Zupancic M, Ribas J L, Burke A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Haase A T. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes and macrophages by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Nature. 1993;362:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fern J, Good M F. Promiscuous malaria peptide epitope stimulates CD45Ra T cells from blood of nonexposed donors. J Immunol. 1992;148:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth L M, Buck C, Chaisson R E, Quinn T C, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho D D, Richman D D, Siliciano R F. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997;278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flechner E R, Freudenthal P S, Kaplan G, Steinman R M. Antigen-specific T lymphocytes efficiently cluster with dendritic cells in the human primary mixed leukocyte reaction. Cell Immunol. 1988;111:183–195. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankel S S, Wenig B M, Burke A P, Mannan P, Thompson L D R, Abbondanzo S L, Nelson A M, Pope M, Steinman R M. Replication of HIV-1 in dendritic cell-derived syncytia at the mucosal surface of the adenoid. Science. 1996;272:115–117. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gause W C, Mitro V, Via C, Linsley P, Urban J F, Jr, Greenwald R J. Do effector and memory T helper cells also need B7 ligand costimulatory signals? J Immunol. 1997;159:1055–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginaldi L, De Martinis M, D’Ostilio A, Marini L, Profeta V, Quaglino D. Activated naive and memory CD4+ and CD8+ subsets in different stages of HIV infection. Pathobiology. 1997;65:91–99. doi: 10.1159/000164109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groux H, Torpier G, Monté D, Mouton Y, Capron A, Ameisen J C. Activation-induced death by apoptosis in CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected asymptomatic individuals. J Exp Med. 1992;175:331–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen L J, Sandmeyer S B. Characterization of a transpositionally active Ty3 element and identification of the Ty3 integrase protein. J Virol. 1990;64:2599–2607. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2599-2607.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inaba K, Romani N, Steinman R M. An antigen-independent contact mechanism as an early step in T cell-proliferative responses to dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:527–542. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inaba K, Steinman R M. Accessory cell-T lymphocyte interactions: antigen-dependent and -independent clustering. J Exp Med. 1986;163:247–261. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John G C, Nduati R W, Mbori-Ngacha D, Overbaugh J, Welch M, Richardson B A, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Krieger J, Onyango F, Kreiss J K. Genital shedding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA during pregnancy: association with immunosuppression, abnormal cervical or vaginal discharge, and severe vitamin A deficiency. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:57–62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kampinga G A, Simonon A, Van de Perre P, Karita E, Msellati P, Goudsmit J. Primary infections with HIV-1 of women and their offspring in Rwanda: findings of heterogeneity at seroconversion, coinfection, and recombinants of HIV-1 subtypes A and C. Virology. 1997;227:63–76. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanitakis J, Escaich S, Trepo C, Thivolet J. Detection of human immunodeficiency virus-DNA and RNA in the skin of HIV-infected patients using the polymerase chain reaction. J Investig Dermatol. 1991;97:91–96. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12478379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan G, Nusrat A, Witmer M D, Nath I, Cohn Z A. Distribution and turnover of Langerhans cells during delayed immune responses in human skin. J Exp Med. 1987;165:763–776. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langhoff E, Terwilliger E F, Bos H J, Kalland K H, Poznansky M C, Bacon O M, Haseltine W A. Replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in primary dendritic cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7998–8002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leroux C, Issel C J, Montelaro R C. Novel and dynamic evolution of equine infectious anemia virus genomic quasispecies associated with sequential disease cycles in an experimentally infected pony. J Virol. 1997;71:9627–9639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9627-9639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine B L, Mosca J D, Riley J L, Carroll R G, Vahey M T, Jagodzinski L L, Wagner K F, Mayers D L, Burke D S, Weislow O S, St. Louis D C, June C H. Antiviral effect and ex vivo CD4+ T cell proliferation in HIV-positive patients as a result of CD28 costimulation. Science. 1996;272:1939–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macatonia S E, Lau R, Patterson S, Pinching A J, Knight S C. Dendritic cell infection, depletion and dysfunction in HIV-infected individuals. Immunology. 1990;71:38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mackay C R, Marston W, Dudler L. Altered patterns of T cell migration through lymph nodes and skin following antigen challenge. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2205–2210. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mackay C R, Marston W L, Dudler L, Spertini O, Tedder T F, Hein W R. Tissue-specific migration pathways by phenotypically distinct subpopulations of memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:887–895. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahalingam M, Pozniak A, McManus T J, Senaldi G, Vergani D, Peakman M. Abnormalities of CD45 isoform expression in HIV infection. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;81:210–214. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNearney T, Hornickova Z, Markham R, Birdwell A, Arens M, Saah A, Ratner L. Relationship of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 sequence heterogeneity to stage of disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10247–10251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehta D A, Markowicz S, Engleman E G. Generation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell lines from naive precursors. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1206–1211. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller C J, Alexander N J, Sutjipto S, Lackner A A, Gettie A, Hendrickx A G, Lowenstine L J, Jennings M, Marx P A. Genital mucosal transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus: animal model for heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1989;63:4277–4284. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.10.4277-4284.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller C J, Vogel P, Alexander N J, Sutjipto S, Hendrickx A G, Marx P A. Localization of SIV in the genital tract of chronically infected female rhesus macaques. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:655–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novella I S, Duarte E A, Elena S F, Moya A, Domingo E, Holland J J. Exponential increases of RNA virus fitness during large population transmissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5841–5844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ostrowski M A, Stanley S K, Justement J S, Gantt K, Goletti D, Fauci A S. Increased in vitro tetanus-induced production of HIV type 1 following in vivo immunization of HIV type 1-infected individuals with tetanus toxoid. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:473–480. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Demarest J F, Butini L, Montroni M, Fox C H, Orenstein J M, Kotler D P, Fauci A S. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature. 1993;362:355–358. doi: 10.1038/362355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinchuk L M, Polacino P S, Agy M B, Klaus S J, Clark E A. The role of CD40 and CD80 accessory cell molecules in dendritic cell-dependent HIV-1 infection. Immunity. 1994;1:317–325. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pope M, Betjes M G H, Romani N, Hirmand H, Cameron P U, Hoffman L, Gezelter S, Schuler G, Steinman R M. Conjugates of dendritic cells and memory T lymphocytes from skin facilitate productive infection with HIV-1. Cell. 1994;78:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poss M, Gosink J, Thomas E, Kreiss J K, Ndinya-Achola J, Mandaliya K, Bwayo J, Overbaugh J. Phylogenetic evaluation of Kenyan HIV-1 isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:493–499. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poss M, Martin H, Kreiss J, Nyange P, Mandaliya K, Chohan B, Overbaugh J. Diversity in virus populations from genital mucosa and peripheral blood in women recently infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1995;69:8118–8122. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8118-8122.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poss M, Rodrigo A G, Gosink J J, Learn G H, Panteleeff D D, Martin Jr H L, Bwayo J, Kreiss J K, Overbaugh J. Evolution of envelope sequences from the genital tract and peripheral blood of women infected with clade A human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:8240–8251. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8240-8251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roederer M, Raju P A, Mitra D K, Herzenberg L A, Herzenberg L A. HIV does not replicate in naive CD4 T cells stimulated with CD3/CD28. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:1555–1564. doi: 10.1172/JCI119318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romani N, Gruner S, Brang D, Kampgen E, Lenz A, Trockenbacher B, Konwalinka G, Fritsch P O, Steinman R M, Schuler G. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J Exp Med. 1994;180:83–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roos M T, Lange J M, de Goede R E, Coutinho R A, Schellekens P T, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Viral phenotype and immune response in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:427–432. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schnittman S M, Lane H C, Greenhouse J, Justement J S, Baseler M, Fauci A S. Preferential infection of CD4+ memory T cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence for a role in the selective T-cell functional defects observed in infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6058–6062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schuitemaker H, Koot M, Kootstra N A, Dercksen M W, de Goede R E, van Steenwijk R P, Lange J M, Eeftink Schattenkerk J K M, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus population. J Virol. 1992;66:1354–1360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1354-1360.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schuitemaker H, Kootstra N A, de Goudl R E, de Wolf F, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) variants detectable in all stages of HIV-1 infection lack T-cell line tropism and syncytium-inducing ability in primary T-cell culture. J Virol. 1991;65:356–363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.356-363.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sleasman J W, Aleixo L F, Morton A, Skoda-Smith S, Goodenow M M. CD4+ memory T cells are the predominant population of HIV-1-infected lymphocytes in neonates and children. AIDS. 1996;10:1477–1484. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spina C A, Guatelli J C, Richman D D. Establishment of a stable, inducible form of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA in quiescent CD4 lymphocytes in vitro. J Virol. 1995;69:2977–2988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2977-2988.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spira A I, Marx P A, Patterson B K, Mahoney J, Koup R A, Wokinsky S M, Ho D D. Cellular targets of infection and route of viral dissemination after an intravaginal inoculation of simian immunodeficiency virus into rhesus macaques. J Exp Med. 1996;183:215–225. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stanley S K, Ostrowski M A, Justement J S, Gantt K, Hedayati S, Mannix M, Roche K, Schwartzentruber D J, Fox C H, Fauci A S. Effect of immunization with a common recall antigen on viral expression in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1222–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steinman R M. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tersmette M, de Goede R E Y, Al B J M, Winkel I N, Gruters R A, Cuypers H T, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Differential syncytium-inducing capacity of human immunodeficiency virus isolate: frequent detection of syncytium-inducing isolates in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. J Virol. 1988;62:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2026-2032.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tersmette M, Gruters R A, de Wolf F, de Goede R E Y, Lange J M A, Schellekens P T A, Goudsmit J, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Evidence for a role of virulent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the pathogenesis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: studies on sequential HIV isolates. J Virol. 1989;63:2118–2125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2118-2125.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Noesel C J M, Gruters R A, Terpstra F G, Schellekens P T A, van Lier R A W, Miedema F. Functional and phenotypic evidence for a selective loss of memory T cells in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-infected men. J Clin Investig. 1990;86:293–299. doi: 10.1172/JCI114698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van’T Wout A B, Kootstra N A, Mulder-Kampinga G A, Albrecht-van Lent N, Scherpbier H J, Veenstra J, Boer K, Coutinho R A, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H. Macrophage-tropic variants initiate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection after sexual, parenteral and vertical transmission. J Clin Investig. 1994;94:2060–2067. doi: 10.1172/JCI117560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weissman D, Daucher J, Barker T, Adelsberger J, Baseler M, Fauci A S. Cytokine regulation of HIV replication induced by dendritic cell-CD4-positive T cell interactions. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:759–767. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weissman D, Li Y, Orenstein J M, Fauci A S. Both a precursor and a mature population of dendritic cells can bind HIV. J Immunol. 1995;155:4111–4117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolfs T F, Zwart G, Bakker M, Goudsmit J. HIV-1 genomic RNA diversification following sexual and parenteral virus transmission. Virology. 1992;189:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90685-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolinsky S M, Korber B T M, Neumann A U, Daniels M, Kunstman K J, Whetsell A J, Furtado M R, Cao Y, Ho D D, Safrit J T, Koup R A. Adaptive evolution of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 during the natural course of infection. Science. 1996;272:537–542. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wong J K, Hezareh M, Gunthard H F, Havlir D V, Ignacio C C, Spina C A, Richman D D. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Woods T C, Roberts B D, Butera S T, Folks T M. Loss of inducible virus in CD45RA naive cells after human immunodeficiency virus-1 entry accounts for preferential viral replication in CD45RO memory cells. Blood. 1997;89:1635–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang L Q, MacKenzie P, Cleland A, Holmes E C, Leigh Brown A J, Simmonds P. Selection for specific sequences in the external envelope protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 upon primary infection. J Virol. 1993;67:3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3345-3356.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 in patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]