In Barrett's oesophagus the stratified squamous epithelium that normally lines the distal oesophagus is replaced by an abnormal columnar epithelium that has intestinal features.1 The abnormal epithelium (called specialised intestinal metaplasia) usually shows evidence of DNA damage that predisposes to malignancy,2 and most oesophageal adenocarcinomas seem to arise from this metaplastic tissue.3 Barrett's oesophagus affects mainly white men, among whom the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma has more than quadrupled over the past few decades.4 The quandary is to know what to do to prevent Barrett's oesophagus from turning into oesophageal cancer.

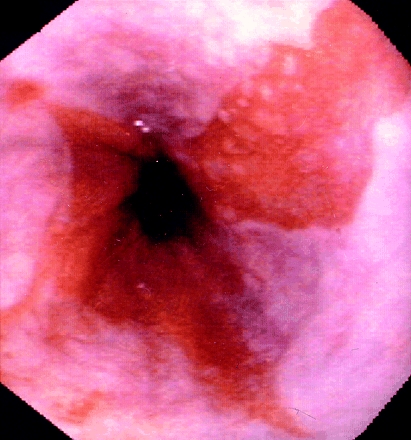

Barrett's oesophagus develops as a consequence of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and is usually discovered during endoscopy performed to evaluate the symptoms of reflux disease. Endoscopists recognise Barrett's oesophagus because the dull red of the metaplastic columnar epithelium contrasts sharply with the pale glossy normal squamous lining (figure).

Barrett's oesophagus is classified as long segment or short segment, depending on whether or not the specialised intestinal metaplasia extends 3 cm or more above the gastro-oesophageal junction.5 Among patients who have endoscopy for symptoms of reflux, long segment Barrett's oesophagus is found in 3-5% and short segment disease in 10-15%.1 Although it is not clear whether long and short segment Barrett's oesophagus have the same pathogenesis and risk for malignancy, the two conditions are managed similarly.

Barrett's oesophagus is a strong risk factor for oesophageal adenocarcinoma, a lethal malignancy; yet several studies have found that survival for patients with Barrett's oesophagus does not differ significantly from that for matched individuals in the general population.6 This seeming paradox may be explained with the low absolute (rather than the high relative) incidence of cancer in Barrett's oesophagus. Modern data indicate that patients with Barrett's oesophagus develop oesophageal adenocarcinomas at the rate of 0.5% per year, a rate that is more than 30-fold higher than that of the general population but low in absolute terms.7 Studies of survival in patients with Barrett's oesophagus have been done predominantly in older men, for whom the risk of death from common lethal disorders (myocardial infarction, stroke) far exceeds their 0.5% annual risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma.8 A long term study of young patients with Barrett's oesophagus might show that the condition shortens life, but no such study has been published.

Several management strategies have been proposed to reduce mortality from cancer in Barrett's oesophagus. These include (a) normalisation (rather than mere reduction) of oesophageal acid exposure with antisecretory drugs, often in doses and combinations beyond those required to heal the symptoms and signs of reflux disease; (b) antireflux surgery; (c) endoscopic ablation of the metaplastic epithelium; (d) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that inhibit cyclo-oxygenase and its effects on cellular proliferation; and (e) regular endoscopic surveillance.1,9,10 Although each strategy has a plausible rationale and some indirect evidence to support it, none has proved to reduce deaths from cancer in Barrett's oesophagus. Furthermore, each entails expense, inconvenience, and variable risk. Among the preventive strategies for cancer, only regular endoscopic surveillance has been recommended for routine clinical use by several medical societies, including the American College of Gastroenterology.1,10

When assessing cancer prevention strategies for Barrett's oesophagus, doctors should consider the implications of the low absolute risk of developing oesophageal cancer. Assume that there is a highly effective treatment for Barrett's oesophagus that will reduce the risk of cancer development by half—from 0.50% to 0.25% per year. This represents an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 0.25%. Thus the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of cancer in one year is 400 (NNT=1/ARR; 1/0.0025=400). Thus, even if there were a highly effective cancer preventive treatment for Barrett's oesophagus, 400 patients would need to be treated to prevent one case of cancer in one year. Such a large number can be acceptable if the treatment is reasonably inexpensive, convenient, and safe.

Regular endoscopic surveillance is recommended for patients with Barrett's oesophagus despite the high cost and inconvenience and the lack of proof that it prolongs survival. A randomised trial to establish the efficacy of surveillance would require dauntingly large numbers of patients and length of follow up, and the results of such a study are unlikely to be available in the near future. Indirect evidence that surveillance is beneficial comes from observational studies, showing that cancers discovered during surveillance are less advanced and associated with longer survivals than those detected during endoscopies performed for evaluating cancer symptoms.11 Such studies are not definitive because they are highly susceptible to biases that can inflate the benefits of surveillance by including biases of selection, healthy volunteers, lead time, and length time.

Computer models too have implied that endoscopic surveillance can be beneficial,12,13 but such models also are not definitive. Models provide a range of possible outcomes that vary with changes in baseline assumptions and with estimates of what a healthcare provider is willing to pay for a good result. In one Markov model that assumed an annual cancer incidence rate of 0.4%, endoscopic surveillance performed every five years was the preferred strategy for patients with Barrett's oesophagus, costing $98 000 (£62 000; €92 000) per quality adjusted life year gained.12

Thus both observational studies and computer models indicate that surveillance can reduce mortality from cancer in Barrett's oesophagus, but at considerable expense. Surveillance is clearly associated with risks, including complications from both endoscopy and the invasive procedures used to treat lesions found by endoscopy, but no study has shown an overall survival disadvantage for patients in surveillance programmes.

In this murky situation, where most of the indirect evidence implies that surveillance is beneficial, I prefer to err by performing unnecessary surveillance rather than missing curable oesophageal neoplasms. Therefore, I support the strategy recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology as follows10:

Patients with Barrett's oesophagus should have regular surveillance endoscopy. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease should be treated before surveillance to minimise confusion caused by inflammation in the interpretation of dysplasia.

Patients who have had two consecutive endoscopies that show no dysplasia should undergo surveillance by endoscopy every three years.

If dysplasia is noted the finding should be verified by consultation with another expert pathologist.

Patients with verified low grade dysplasia after extensive biopsy sampling should have yearly surveillance endoscopy

For patients found to have high grade dysplasia another endoscopy should be performed with extensive biopsy sampling (especially from areas with mucosal irregularity) to look for invasive cancer, and the histology slides should be interpreted by an expert pathologist. If there is verified, multifocal high grade dysplasia, intervention (oesophagectomy) may be considered.

Figure.

Long segment Barrett's oesophagus. The dull red of the metaplastic columnar epithelium contrasts with the pale, glossy appearance of the normal squamous lining

Footnotes

Competing interests: SJS has been reimbursed for speaking at educational programmes sponsored by AstraZeneca, Janssen, and TAP and has received grant support from AstraZeneca and Wyeth-Ayerst.

References

- 1.Spechler SJ. Barrett's esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:836–842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp012118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong DJ, Paulson TG, Prevo LJ, Galipeau PC, Longton G, Blount PL, et al. p16(INK4a) lesions are common, early abnormalities that undergo clonal expansion in Barrett's metaplastic epithelium. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8284–8289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theisen J, Stein HJ, Dittler HJ, Feith M, Kauer WKH, Werner M, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy unmasks underlying Barrett's mucosa in patients with adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:671–673. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiologic trends in esophageal and gastric cancer in the United States. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:235–256. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3207(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P, Morales TG, Sampliner RE. Short segment Barrett's esophagus. The need for standardization of the definition and of endoscopic criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1033–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Bernhard G. Life expectancy and cancer risk in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a prospective controlled investigation. Am J Med. 2001;111:33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, Sandler RS. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett's esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119:333–338. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Welch HG. Risk charts: putting cancer in context. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:799–804. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fennerty MB, Triadafilopoulos G. Barrett's-related esophageal adenocarcinoma: is chemoprevention a potential option? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2302–2305. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampliner RE and The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1888–1895. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corley DA, Levin TR, Habel LA, Weiss NS, Buffler PA. Surveillance and survival in Barrett's adenocarcinomas: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:633–640. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provenzale D, Schmitt C, Wong JB. Barrett's esophagus: a new look at surveillance based on emerging estimates of cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2043–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inadomi JM, Sampliner R, Lagergren J, Lieberman D, Fendrick AM, Vakil N. Screening and surveillance for Barrett esophagus in high-risk groups: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:176–186. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]