Abstract

Objectives:

This study examined the theoretically grounded conceptual model of a multi-level intervention, Family Health = Family Wealth (FH=FW), by examining FH=FW’s effect on intermediate outcomes among couples in rural Uganda. FH=FW is grounded in the social ecological model and the social psychological theory of transformative communication.

Design:

A pilot quasi-experimental controlled trial.

Methods:

Two matched clusters (communities) were randomly allocated to receive the FH=FW intervention or an attention/time-matched water, sanitation, and hygiene intervention (N=140, 35 couples per arm). Quantitative outcomes were collected through interviewer-administered questionnaires at baseline, 7-months, and 10-months follow-up. Focus group discussions (n=51) and semi-structured interviews (n=27) were conducted with subsets of FH=FW participants after data collection. Generalized estimated equations tested intervention effects on quantitative outcomes, and qualitative data were analyzed through thematic analysis – these data were mixed and are presented by level of the social ecological model.

Results:

The findings demonstrated an intervention effect on family planning determinants across social ecological levels. Improved individual-level family planning knowledge, attitudes, and intentions, and reduced inequitable gender attitudes, were observed in intervention vs. comparator, corroborated by the qualitative findings. Interpersonal-level changes included improved communication, shared-decision-making, and equitable relationship dynamics. At the community-level, FH=FW increased perceived acceptance of family planning among others (norms), and the qualitative findings highlighted how FH=FW’s transformative communication approach reshaped definitions of a successful family to better align with family planning.

Conclusions:

This mixed methods pilot evaluation supports FH=FW’s theoretically-grounded conceptual model and ability to affect multi-level drivers of a high unmet need for family planning.

Keywords: Family planning, contraception, intervention, theory, Uganda

Introduction

Family planning is among the most important global health interventions. Family planning’s health benefits include reductions in maternal and infant mortality, as well as improved health outcomes for children, as planning the spacing and timing of pregnancies allows families to invest more in the health of each child (1). Family planning also improves girls’ and women’s educational and economic opportunities, and on a societal-level enhances progress towards health, economic, gender equity, and other development goals (2). Despite these benefits and ongoing efforts to expand its access, significant gaps remain in low and middle income countries (LMICs) (3).

Uganda has the seventh highest fertility rate globally (5.45 children per woman in 2021) (4) and 29.7% of married women would like to delay or stop future pregnancies, but are not using a modern contraceptive method (i.e., they have an unmet need for modern contraceptives) (5). To increase contraceptive use in Uganda and similar settings, interventions that address the known multi-level barriers that affect family planning are needed. These factors span the levels of the social ecological model, a framework commonly used to understand determinants of health across the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels (6–8). At the individual-level, low knowledge of contraceptives, and fears/myths about side effects are prevalent (9–11). At the interpersonal-level, male partner disapproval paired with poor communication and inequitable decision-making between partners impede women’s autonomy in contraceptive uptake (11–14). These dynamics are shaped by broader community-level gender and religious norms reinforcing gender inequity, traditional gender roles, and large family size (11, 14, 15). Such demand-side barriers exist alongside supply-side barriers in LMICs, such as long wait times at facilities, contraceptive method stock outs and limited contraceptive mix, poor treatment from providers, limits in providers’ capacity to provide all types of methods and to align methods/service delivery with user preferences (16–20). In rural areas, long distance and travel time to facilities, as well as the cost of transportation, are additional barriers to accessing family planning services (21).

As a result, there have been multiple calls for multi-level family planning interventions to address these barriers, but few interventions have incorporated this approach (22). Global health organizations have commonly used community dialogues for sexual and reproductive health service demand generation, which follow a defined process to identify local drivers of sexual and reproductive health with community groups (23), and engage the community in problem-solving towards a common issue through community-based participatory methodologies (24). Dialogues are often theoretically grounded in Campbell and Cornish’s social psychological theory of transformative communication (25), which emphasizes the role of conversations in safe social spaces in the development of social norms (26). Therefore, they may be a promising approach for transforming inequitable gender norms and norms about family size that impede contraceptive. Evidence supports their positive effects on improving equitable relationships, community gender norms, and community ownership of a problem (24, 27–34). However, there is a gap of rigorous evaluations of the effect of community dialogues on behavioral and health outcomes (35). Moreover, given the wide array of barriers that impede contraceptive use, community dialogues may need to be enhanced to address other multi-level barriers, such as integrating strategies to effectively engage men and to reduce barriers to accessing family planning services at the health system-level.

This study team developed the Family Health = Family Wealth (FH=FW) intervention to address these gaps in the literature using a theory-grounded, multi-level, community-based intervention to increase contraceptive use among couples with an unmet need for family planning in rural Uganda. FH=FW consisted of health system strengthening activities alongside four facilitated group dialogues grounded in Campbell and Cornish’s social psychological theory of transformative communication (25), the primary mechanism of action theorized to affect change across the social ecological levels of individual, interpersonal, and community levels, specifically through change in individual knowledge, attitudes and intentions, relationship dynamics, and the perception of community norms related to family planning acceptance and gender equity. FH=FW’s feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects on increased contraceptive use and reduced fertility desires through approximately 10 months follow-up among couples with an unmet need for family planning in rural Uganda was supported (findings reported in a separate paper). The current study aims to shed light on the mechanisms of action that may have contributed to behavior change by examining the intervention’s preliminary effects on the hypothesized intermediate outcomes in the theoretically grounded conceptual model. Organized by social ecological level, these quantitatively measured outcomes include those at the individual-level (contraceptive knowledge, family planning attitudes, family planning intentions, gender inequitable attitudes), interpersonal-level (family planning spousal communication, joint spousal decision-making, spousal fertility concordance), and community-level (perceived family planning norms). Using a mixed methods embedded experimental design (36), qualitative data collected from participants is used to confirm and expand on these quantitative findings, and to explore the preliminary effects that the transformative communication approach had on prevalent community beliefs that are counter to family planning acceptance. As a Stage 1b Pilot Trial (pilot testing of new behavioral interventions), these aims to examine the intervention’s potential effects are exploratory and meant to support progression to a future, fully powered efficacy trial (37).

Methods

This study employed a QUAN (+qual) mixed methods embedded experimental design, following Creswell & Plano-Clark (36). This design included a quasi-experimental controlled pilot trial to explore the intervention’s preliminary effects on quantitative outcomes measured at baseline, 7- and 10-months follow-up. Embedded in the experimental design was a qualitative assessment (focus groups or in-depth interviews) after the 10-month quantitative assessment. The QUAN (+qual) embedded design included the secondary qualitative strand within the larger quantitative experiment to help interpret and expand on the quantitative results on preliminary intervention effects (36). The quasi-experimental controlled trial was conducted from May 2021 to May 2022, comparing two matched clusters (communities) randomly allotted to receive the FH=FW intervention or an attention/time-matched comparator intervention. The overall aim of the trial was to examine feasibility, acceptability, and the preliminary effects of the intervention on contraceptive use and related outcomes, following recommendations for Stage 1b pilot studies (37). The institutional review boards at the University of Texas at San Antonio in the United States and Makerere University School of Public Health in Uganda approved the study. The Uganda National Council for Science and Technology also granted study approval and entry into the communities was permitted by the district leadership. The study’s protocol has been published (38) and the trial was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04262882) on February 10, 2020.

The study took place in selected communities in a district in central Uganda. The area is semi-rural with a population of approximately 110,000 in an area of approximately 270 mi2. The government public health facilities provide family planning services for free in the district, integrated into general outpatient services. Limited methods can also be accessed locally through private not-for-profits and local private shops for purchase. All villages are served by a cadre of community health workers known as the Village Health Team (VHT), which support community family planning efforts by providing community education about family planning and distributing short-term methods directly in the community in addition to other community health roles. In addition, an international nongovernmental organization provides quarterly community family planning service outreach in selected villages.

Inclusion Criteria

Study participants were eligible for participation under the following criteria developed to ensure we included couples with reproductive capability and in need of family planning: 1) women aged 18 (or emancipated minors defined as those under 18 who are married, have children, or are pregnant) to 40 and men aged 18 (or emancipated minors) to 50; 2) married or considers themselves married and living together most of the time; 3) residing in communities selected for inclusion in the study; 4) Luganda speaking; 5) sexually active with spouse within the past 3 months or planning to resume sex within the next 3 months if more than 1 month postpartum; 6) not currently pregnant; 7) have an unmet need for family planning, i.e., couples of reproductive age in which at least one person in the couple reports not wanting to become pregnant within the next year but are not using any contraceptive methods or are using only low-efficacy methods (condoms less than 100% of the time, lactational amenorrhea, fertility-awareness based methods e.g., counting method, withdrawal method). Couples were excluded if: 1) at least one person in the couple did not expect to be available for all four sessions; 2) the woman was pregnant (verified through pregnancy test); 3) both the woman/man reported wanting to get pregnant within the next year; 4) the couple reported currently using an effective method of contraception (IUD, injection, oral pill, implant, vasectomy, tubal ligation, condoms 100% of the time); 5) the woman or man had a known medical reason that would prevent a pregnancy (i.e., as told by a doctor); 6) postpartum within 1 month of birth.

Sampling and randomization

The two communities were selected in partnership with an Intervention Steering Committee, which was convened to provide local expertise on intervention development and implementation. It was comprised of district political and health leaders, local family planning providers, and other family planning stakeholders. Two village clusters (which we refer to as communities) were roughly matched on the following criteria: population size (~2,000), distance to the general hospital and a health center III (a midsize governmental health center offering short and long-term methods), no ongoing/recent health education interventions, religion, and trade, and being at least 10 km from each other and not located along the same road to avoid potential contamination. One community was randomly assigned to receive the intervention and one as the comparator through coin toss.

Recruitment procedures

After randomization, the VHT in each community visited homes to gain permission to return with the research assistant (RA). The VHT was masked to the study aims and inclusion criteria. After introductions, the VHT returned with the RA, introduced them, and left. Snowball sampling was also used; enrolled couples could refer other couples who lived in the area and of similar age to the RA or VHT. Both arms received the same recruitment script and consent form to mask participants and the RAs to the study’s purpose. Participants were told they could receive content on a range of “family wellness” topics chosen through random selection (health, healthy relationships, water, sanitation, and hygiene [WASH], family planning, economic wellness). RAs assessed eligibility with a screening tool and obtained written informed consent from both individuals in the couple. After enrollment, negative pregnancy status was confirmed via Human Chorionic Gonadotropin rapid pregnancy tests; if found pregnant, couples would be withdrawn and referred to the local health facility.

Sample size

As a Stage 1b Pilot Trial (pilot testing of new behavioral interventions) (37), the main aim of this trial was to examine feasibility and acceptability of the intervention content and trial procedures (reported elsewhere) (39), while exploring the intervention’s preliminary effects on our outcomes. Thus, we based our sample size for our quasi-experimental controlled trial on guidelines for Stage 1b studies, which suggest 15–30 participants per cell, choosing 35 couples per condition (n=70 individuals per condition) (37). Even assuming moderate attrition (20%), we would have 28 couples per condition, which is still within the guidelines for pilot studies. For illustrative purposes, a priori, pswe explored our study’s power to detect changes in contraceptive use among couples (our main outcome, reported elsewhere) (39). We estimated that a sample of 35 couples per condition would provide 70% power to detect a moderate effect size (d=0.3) assuming an ICC of .30 and a 2-tailed alpha of .05. For the qualitative portion of the study, the aim was to engage the entire intervention arm’s sample in a follow-up assessment.

Comparator intervention

Participants in the comparison village received an intervention focused on water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). The content was time/attention-matched to the intervention, including directive education, open dialogue, and group/couple problem solving using an existing curriculum developed for community health workers in Ethiopia with support from USAID and the Water and Sanitation Program (40). The content was adapted for the local context in consultation with a local VHT and health worker. Following the structure of our family planning intervention, comparator sessions included two gender-segregated and two gender-mixed sessions delivered to groups of couples.

Family Health = Family Wealth Intervention (FH=FW)

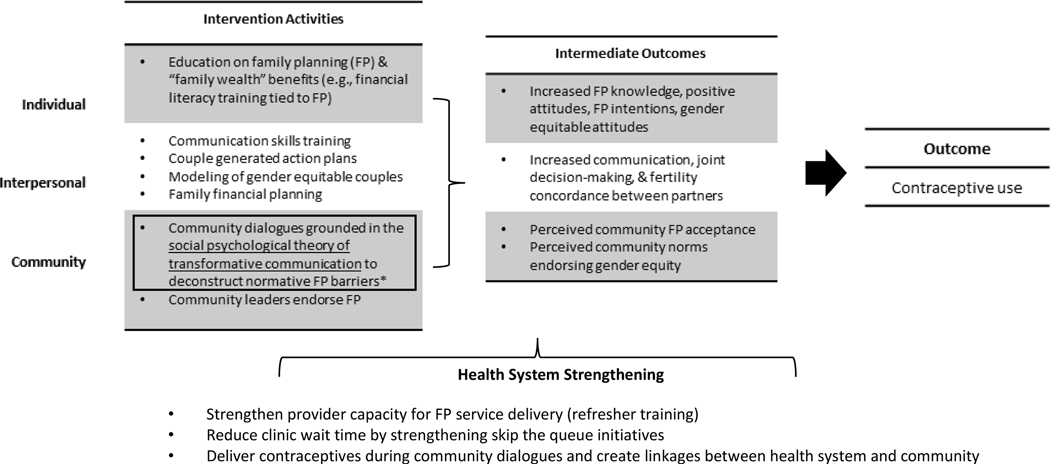

The intervention arm community was randomized to receive the multilevel, community-based FH=FW intervention, which has been described in detail elsewhere (38). The core intervention components and their hypothesized effect on intermediate and primary outcomes are detailed in Figure 1, along with a visual depiction of the theorized interactions between the intervention’s synergistic theoretical frameworks.

Figure 1.

Intervention Activities and their Hypothesized Effect on Contraceptive Use by Level of the Social Ecological Model

Notes: The primary mechanism of action theorized to affect change across the individual, interpersonal, and community-levels is community dialogues grounded in Campbell & Cornish’s social psychological theory of transformative communication

The intervention consisted of four facilitated group sessions with couples (two gender segregated, two gender mixed). Each of the four sessions included facilitated discussions adapted from a community dialogue approach, grounded in Campbell and Cornish’s social psychological theory of transformative communication (25). The group dialogues aimed to reshape community norms around gender roles, equity, and family size, and critically analyze the social and community influences of “family-wealth” and poverty with the overall goal of reconstructing individual attitudes and group norms on paths to/definitions of a “successful family” inclusive of family planning. Dialogues were theorized as the primary mechanism of action to affect change across the individual, interpersonal, and community levels, specifically through change in individual knowledge, attitudes and intentions, interpersonal communication and joint decision-making, and the perception of community norms related to family planning acceptance and personal endorsement of prevalent gender norms.

Guided by the social ecological model (6–8) and the formative research phase (11–13) the dialogues were enhanced to target individual, interpersonal, and community drivers of contraceptive use through the inclusion of individual and couple-based education, skill building, and goal-setting activities (family health/planning, relationship, and economic goals), and community leader involvement focused on family planning’s benefits to relationship “family health and wealth” (physical, relationship, economic health) (outlined in Figure 1). A transport refund of 5,000 UGX (~1.50 USD) per person was provided for each session attended following local customs for community meetings.

Data collection procedures and measures

Quantitative

Participants completed a computerized structured interview immediately following enrollment, and at approximately 7- and 10-months follow-up, in a private setting within the participant’s home, another agreed upon location, or over the phone for follow-ups only, if necessary. The structured interview tool was pre-tested through mock interviews conducted at a nearby village with characteristics similar to the study population. The aim was to ensure participant comprehension, cultural equivalence, and assess the tool’s length. Participants received 15,000 UGX (~4 USD) for each interview. The baseline questionnaire assessed socio-demographics and family planning history (e.g., age, religion, prior use of contraceptives), and all timepoints included measures to examine change in the intervention’s hypothesized intermediate outcomes, detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study measures, Family Health = Family Wealth intervention pilot trial, Uganda, 2021–22

| Outcome | Measurement | Scale range Cronbach’s α at baseline |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of contraceptive methods | The mean of 9 items from the Uganda DHS measures is calculated on participants’ awareness of different contraceptive methods (38), including effective methods available locally (female sterilization, male sterilization, IUD, injectables, implants, oral pill, emergency contraception, male condom, female condom). Participants indicated if they had ever heard of these methods (yes/no). Higher scores indicate more knowledge. | 0.00–1.00 α = 0.84 |

| Family planning attitudes | Feelings about family planning were measured at all time points through a scale developed for use in Uganda and found reliable and predictive of contraceptive use in Uganda (13). The mean of 6 items measuring self and perceived partner attitudes were calculated (e.g., how would you feel about receiving couples counseling about family planning with your partner). The five-point response scale ranged from “Very bad” to “Very good.” Higher scores indicate more positive family planning attitudes. | 0.00–4.00 α = 0.94 |

| Family planning intentions | Intentions to discuss family planning with one’s partner, seek couple services, and use family planning in the future were measured at all time points from the mean of 3 items based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (13). The five-point response scale ranges from “Very unlikely” to “Very likely.” Higher scores indicate greater family planning intentions. | 0.00–4.00 α = 0.93 |

| Inequitable gender attitudes | The mean of the 24-item Gender Equitable Men scale measured endorsement of traditional gender norms and attitudes on gender inequity, validated in Tanzania and Ghana (39)(40), with good reliability in African settings (40–43). Domains include violence, sexual relationships, reproductive health and disease prevention, and domestic chores and daily life items. Higher scores indicate more inequitable gender attitudes. | 0.00–3.00 α = 0.80 |

| Partner communication about family planning | The mean of two items on the frequency of communication with one’s partner about family planning found predictive of family planning in Uganda (12, 13). Participants were asked, in the last 12 months, “How often have you discussed the number of children you want with your partner?” and “How often have you discussed the spacing or timing of your/your partner’s pregnancies with your partner.” The four-point response options ranged from “Never” to “Regularly.” At the two follow-up time points, the same questions were asked with the timeframe, “since the last interview.” Higher scores indicate more communication. | 0.00–3.00 N/A |

| Joint household decision-making | Joint household decision-making was measured with four items from the Uganda DHS that ask respondents who primarily decides on: 1) how the money they earn is used; 2) how their spouses’ earnings are used; 3) decisions about healthcare for yourself; and 4) decisions about major household purchases (38). Response options were recoded as self and partner jointly (1) vs. all other (0). A mean score was calculated for each time point with greater scores indicating more joint decision-making (). | 0.00–1.00 α = 0.73 |

| Any fertility discordance (couple variable) | An item from the Uganda DHS on the participants’ desired number of children, “How many more children do you want to have?” was used to calculate the couple variable fertility discordance by subtracting men and women’s responses within couples (38). This was dichotomized for analysis; for couples where the product was zero, they were classified as having no discordance (0) and for couples where the produce was anything other than zero, they were classified as having discordance (1). | N/A |

| Perceived family planning norms | The Family Planning Approval Index, originally developed with couples in rural Kenya, were used at all time points to assess the perceived acceptance of family planning and contraceptive use among one’s partner, family, peers, and broader community (44). For example, “Do you think that most of your friends in this community would approve or disapprove of couples using family planning to avoid or delay a pregnancy?” Response options include: “Disapprove,” “Approve,” and “Don’t know.” Each item was scored so that don’t know/disapprove were collapsed (0) vs approve (1), and the mean score was calculated. Higher scores indicate greater perceived family planning approval among others. | 0.00–1.00 α = 0.65 |

Qualitative

After final follow-up quantitative data collection was completed, all participants in the intervention arm were invited to participate in a final qualitative assessment. Using the 7- and 10-month quantitative questionnaire data, participants who started using contraceptive methods at any point during the study were invited to participate in a one of five focus group discussions (2 with women, 3 with men) (N=51). A trained and experienced facilitator moderated approximately 90-minute sessions in the local language following a structured interview protocol that elicited participants’ experience with the intervention and its potential positive, negative, and null effects on family planning, relationship, and other relevant outcomes. A research assistant took detailed notes. After the first focus groups with men and women, the audio was transcribed and reviewed by the investigative team, discussed with the moderators, and revisions made to the tools to improve comprehension, cultural equivalence, flow, and participant engagement before continuing other focus groups or interviews.

Participants that did not report any contraceptive uptake during the study period were invited to participate in a one-on-one semi-structured, in-depth interview (N=27). Conducting individual interviews for those who did not start using contraceptives was done to separately explore reasons for use vs. non-use and differential intervention experiences and perceptions between these groups. A trained qualitative interviewer conducted the interview at the participants’ home or a place of their choosing or over the phone (approximately 20-minutes in duration). The individual interview guide was similar to the focus group protocol, with additional questions to examine reasons why participants did not start using contraception. Focus groups and individual interviews were audio-recorded, translated, and transcribed.

Data analysis approach

In SPSS v. 28, Generalized Estimating Equation models (GEE) were used for the main analyses (linear for continuous outcomes and logistic for binary outcomes), with time and gender specified as within-subject effects. GEE accounts for dependence in repeated measures and dyadic data. An analysis for baseline equivalence was previously conducted and reported elsewhere; baseline differences were found between treatment arms in religion, and age was identified as an important covariate; therefore, all models control for religion and age. The time by arm interaction is reported and the time by intervention by gender effect was tested, but only remained in the models if statistically significant (p < 0.05). Unstandardized betas (b) and standard errors (SE) are reported for continuous outcomes and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for binary outcomes. Since the number of outcomes/tests conducted increases the risk of type I error, we report intervention effects at p < 0.05, but also note in the results tables whether they are statistically significant with a more conservative p value (0.006), derived by dividing 0.05 by 8, the total number of tests/outcomes.

Qualitative

Data were analyzed thematically (41). The project directors (KS, CM, SK) developed a coding guide through an iterative review of the transcripts. To explore the specific question of the intervention’s potential effects or null effects on individual and couple outcomes, the coding guide included a coding structure that focused on family planning effects, relationship effects, and economic effects (following the intervention’s three focal areas of health). Two trained research assistants (BE, SM) used an iterative process to apply codes to transcripts. Coders met weekly with KS to discuss new codes and potential themes, and to resolve discrepancies through discussion and consensus. New codes were drawn inductively from the data at this stage, including sub-codes related to family planning, relationship, and economic health outcomes that align with the hypothesized conceptual model and quantitative outcomes (e.g., family planning knowledge, partner communication). To ensure validity of the qualitative data, including the data collected through different approaches (focus groups vs. interviews), methods were triangulated by ensuring codes were built off of data from different individuals and from both data sources (36). KS, CM, and SK reviewed data for similarities and differences between the two sources to validate the data, while seeking to identify if there were thematic differences between focus groups and in-depth interviews (but none emerged). KS reviewed all excerpts after data were fully coded for consensus or re-coding. Codes that represented thematic elements were collated and themes with representative quotations were summarized by KS, with final themes identified through review, discussion, and consensus between KS, CM, and SK.

Mixed methods

Following the QUAN (+qual) design, quantitative data was analyzed first, followed by the qualitative analysis. The findings of qualitative data were compared to the quantitative, and the qualitative findings were mixed with the quantitative intervention effect results at the point of the presentation and interpretation of results (and are presented in the results narrative together). The qualitative data was used to confirm and expand on FH=FW’s observed effects on intermediate outcomes, explore potential interactive intervention effects across social ecological levels (e.g., changes in individual knowledge/attitudes affecting relationship factors), and provide insight into specific elements of the intervention that had an effect or provide possible explanations of null effects. The comparison of qualitative results against quantitative results also served to triangulate and validate the qualitative themes identified.

Results

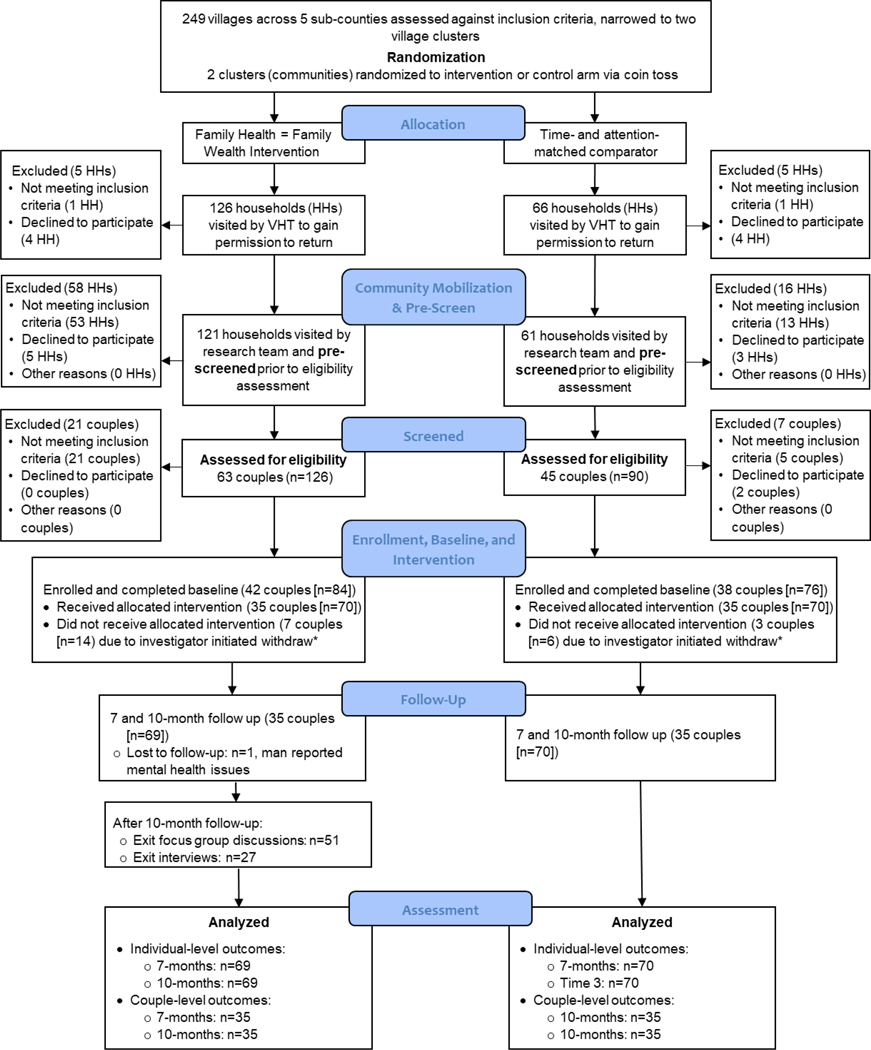

Figure 2 displays the CONSORT study diagram. The final sample included in analysis includes 70 couples (35 per treatment condition). In the intervention, data is missing at times 2 and 3 for one man who was lost-to-follow-up (wife was retained). Participants in the final sample attended 99% of intervention sessions.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram

Notes: *Couples where one or more person did not attend intervention session 1 were withdrawn after session

Characteristics of the study sample are detailed in Table 2 by total sample, study arm, and gender. Participants were 29.8 years (SD = 7.59) on average and mainly of the Baganda tribe (87.9%, n = 123). Only 37.9% (n = 53) of participants reported ever using effective contraceptives in their lifetime.

Table 2.

Demographics at baseline by study arm and gender, Family Health = Family Wealth intervention pilot trial, Uganda, 2021–22

| Full sample (N=140) | FH=FW Intervention | Comparator WASH Intervention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/SD or n (%) | Min-Max | Total (n=70) | Women (n=35) | Men (n=35) | Total (n=70) | Women (n=35) | Men (n=35) | |

| Age | 29.89 (7.59) | 19–50 | 29.01 (6.79) | 26.51 (5.70) | 31.51 (6.93) | 30.77 (8.27) | 27.83 (6.56) | 33.71 (8.82) |

| Wealth index sum | 2.39 (1.16) | 0.00–4.00 | 2.29 (0.95) | 2.26 (1.01) | 2.26 (1.01) | 2.49 (1.34) | 2.46 (1.42) | 2.51 (1.27) |

| In a polygamous marriage | 22 (15.7%) | - | 9 (12.9%) | 4 (11.4%) | 5 (14.3%) | 13 (18.6%) | 6 (17.1%) | 7 (20.0%) |

| Tribe | ||||||||

| All other | 17 (12.1%) | - | 9 (12.9%) | 6 (17.1%) | 3 (8.6%) | 8 (11.4%) | 5 (14.3%) | 3 (8.6%) |

| Baganda (reference) | 123 (87.9%) | - | 61 (87.1%) | 29 (82.9%) | 32 (91.4%) | 62 (88.6%) | 30 (85.7%) | 32 (91.4%) |

| Religion | ||||||||

| Catholic, Protestant, and Other | 58 (41.4%) | - | 36 (51.4%) | 17 (48.6%) | 19 (54.3%) | 22 (31.4%) | 11 (31.4%) | 11 (31.4%) |

| Muslim (ref) | 82 (58.6%) | - | 34 (48.6%) | 18 (51.4%) | 16 (45.7%) | 48 (68.6%) | 24 (68.6%) | 24 (68.6%) |

| Education | ||||||||

| Secondary or more | 68 (48.6%) | - | 38 (54.3%) | 14 (40.0%) | 24 (68.6%) | 30 (42.9%) | 19 (54.3%) | 11 (31.4%) |

| Primary or less (ref) | 72 (51.4%) | - | 32 (45.7%) | 21 (60.0%) | 11 (31.4%) | 40 (57.1%) | 16 (45.7%) | 24 (68.6%) |

| Number of children | 2.69 (2.04) | 0.00–8.00 | 2.46 (2.02) | - | - | 2.91 (2.06) | - | - |

| Ever used effective contraceptives | ||||||||

| Yes | 53 (37.9%) | - | 30 (42.9%) | 20 (57.1%) | 10 (28.6%) | 23 (32.9%) | 17 (48.6%) | 6 (17.1%) |

| No (ref) | 87 (62.1%) | 40 (57.1%) | 15 (42.9%) | 25 (71.4%) | 47 (67.1%) | 18 (51.4%) | 29 (82.9%) | |

Abbreviations: M=mean, SD=standard deviation, b=unstandardized beta, SE=standard error, OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval; FH=FW=Family Health = Family Wealth Intervention; WASH=water, sanitation, and hygiene

Notes: Number of children is measured at the couple level (N=70)

Intervention Effects by Level of the Social Ecological Model

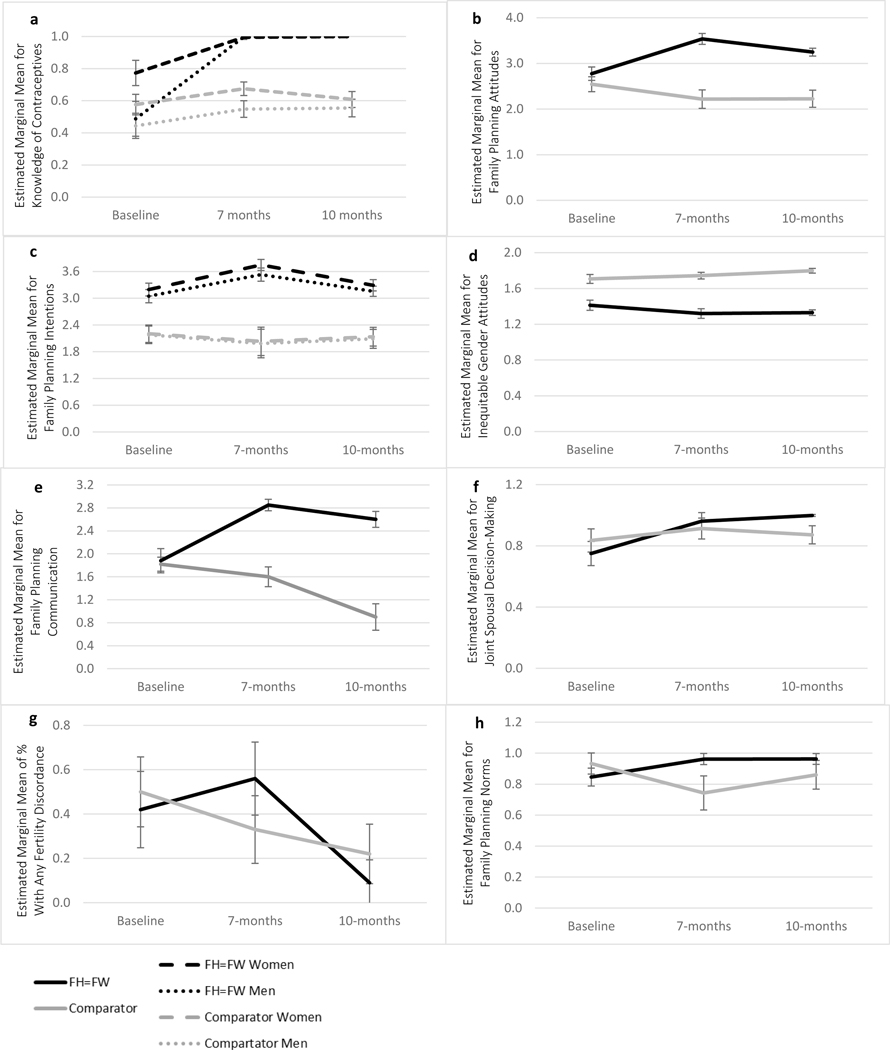

Table 3 displays the results of the GEE models testing the intervention’s effect on each outcome, as well as the descriptive statistics for each outcome at all time points, which are described in detail below and depicted in Figure 3. The qualitative findings are presented alongside the quantitative findings below, and outlined with illustrative quotations in Table 4.

Table 3.

Intervention effect on hypothesized intermediate outcomes by level of the social ecological model, Family Health = Family Wealth intervention pilot trial, Uganda, 2021–22

| FH=FW Intervention (35 couples, n=69) | Comparator WASH Intervention (35 couples, n=70) | Intervention Effect by Time Point Arm*Time | Overall Intervention Effect Arm*Time | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=69) | Women (n=35) | Men (n=34) | Total (n=70) | Women (n=35) | Men (n=35) | b (SE) / AOR (95% CI) | p | Wald | p | |

| Individual level | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Knowledge of contraceptives | 35.20 | <0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.59 (0.16) | 0.61 (0.15) | 0.57 (0.17) | 0.40 (0.07) | <0.001 * | ||

| 7-months | 0.99 (0.26) | 0.99 (0.03) | 0.99 (0.02) | 0.62 (0.15) | 0.68 (0.12) | 0.56 (0.15) | 0.41 (0.07) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline (ref) | 0.63 (0.32) | 0.77 (0.24) | 0.49 (0.34) | 0.52 (0.22) | 0.58 (0.20) | 0.45 (0.23) | ||||

| Family planning attitudes | 64.53 | <0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 3.27 (0.32) | 3.25 (0.30) | 3.29 (0.34) | 2.22 (0.57) | 2.22 (0.59) | 2.21 (0.56) | 0.79 (0.14) | <0.001 * | ||

| 7-months | 3.56 (0.39) | 3.60 (0.37) | 3.51 (0.41) | 2.23 (0.62) | 2.19 (0.65) | 2.27 (0.59) | 1.08 (0.14) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline (ref) | 2.76 (0.51) | 2.76 (0.49) | 2.76 (0.54) | 2.58 (0.55) | 2.58 (0.56) | 2.58 (0.56) | ||||

| Family planning intentions | 48.26 | <0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 3.22 (0.36) | 3.29 (0.38) | 3.16 (0.34) | 2.12 (0.63) | 2.14 (0.64) | 2.10 (0.63) | 0.20 (0.10) | 0.04 | ||

| 7-months | 3.65 (0.42) | 3.74 (0.38) | 3.54 (0.44) | 2.02 (0.97) | 2.04 (0.97) | 2.00 (0.97) | 0.68 (0.12) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline | 3.14 (0.43) | 3.19 (0.44) | 3.08 (0.42) | 2.20 (0.59) | 2.21 (0.59) | 2.20 (0.59) | ||||

| Gender inequitable attitudes | 19.46 | <0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 1.33 (0.12) | 1.29 (0.10) | 1.37 (0.12) | 1.80 (0.09) | 1.81 (0.09) | 1.79 (0.09) | −0.17 (0.04) | <0.001 * | ||

| 7-months | 1.32 (0.18) | 1.28 (0.14) | 1.36 (0.20) | 1.74 (0.12) | 1.74 (0.10) | 1.74 (0.14) | −0.13 (0.05) | 0.008 * | ||

| Baseline (ref) | 1.41 (0.24) | 1.38 (0.21) | 1.44 (0.27) | 1.70 (0.20) | 1.69 (0.22) | 1.72 (0.18) | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Interpersonal level | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Partner communication about family planning | 78.81 | 0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 2.61 (0.48) | 2.61 (0.49) | 2.60 (0.49) | 0.91 (0.70) | 1.75 (1.04) | 0.91 (0.70) | 1.65 (0.19) | 0.001 * | ||

| 7-months | 2.84 (0.34) | 2.86 (0.31) | 2.82 (0.37) | 1.61 (0.54) | 2.22 (0.76) | 1.59 (0.54) | 1.19 (0.18) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline (ref) | 1.89 (0.73) | 1.83 (0.74) | 1.94 (0.73) | 1.82 (0.46) | 1.85 (0.61) | 1.79 (0.47) | ||||

| Shared household decision-making | 13.40 | 0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.87 (0.19) | 0.87 (0.19) | 0.87 (0.20) | 0.21 (0.06) | <0.001 * | ||

| 7-months | 0.97 (0.17) | 0.97 (0.17) | 0.97 (0.17) | 0.91 (0.23) | 0.91 (0.23) | 0.91 (0.23) | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.07 | ||

| Baseline (ref) | 0.75 (0.29) | 0.78 (0.30) | 0.72 (0.28) | 0.84 (0.26) | 0.83 (0.27) | 0.85 (0.25) | ||||

| Any fertility discordance between partners | 10.42 | 0.005 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | ||||||||||

| Yes | 3 (8.6%) | 27 (77.1%) | 0.96 (0.75–1.22) | 0.71 | ||||||

| No (ref) | 31 (88.6%) | 8 (22.9%) | ||||||||

| 7-months | ||||||||||

| Yes | 19 (54.3%) | 12 (34.3%) | 1.36 (0.99–1.85) | 0.05 | ||||||

| No (ref) | 15 (42.9%) | 23 (65.7%) | ||||||||

| Baseline | ||||||||||

| Yes | 15 (42.9%) | 18 (51.4%) | ||||||||

| No (ref) | 20 (57.1%) | 17 (48.6%) | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Community level | ||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Perceived family planning norms | 23.89 | <0.001 * | ||||||||

| 10-months | 0.95 (0.13) | 0.96 (0.11) | 0.94 (0.15) | 0.87 (0.28) | 0.86 (0.29) | 0.88 (0.29) | 0.19 (0.05) | <0.001 * | ||

| 7-months | 0.96 (0.12) | 0.95 (0.13) | 0.98 (0.09) | 0.75 (0.36) | 0.78 (0.35) | 0.72 (0.38) | 0.31 (0.06) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline (ref) | 0.86 (0.21) | 0.88 (0.15) | 0.84 (0.25) | 0.93 (0.21) | 0.94 (0.20) | 0.92 (0.23) | ||||

Abbreviations M=mean, SD=standard deviation, b=unstandardized beta, SE=standard error, AOR=adjusted odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, bold indicates p < 0.05,

indicates p < 0.006 (more conservative cut-off chosen by dividing 0.05 by the number of tests conducted)

Notes: Models control for age and religion. Time*Intervention*Gender effects are reported in text for outcomes for which there was a statistically significant gender interaction. Any fertility discordance between partners is measured at the couple level (N=70).

Figure 3.

a-h. Graphic Depictions the Intervention by Time Effect comparing FH=FW and a Comparator Intervention. Notes: Models control for age and religion. Time*Intervention*Gender effects are displayed for outcomes for which there was a statistically significant gender interaction. Error bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Table 4.

Overview of major themes on the intervention’s effects on hypothesized intermediate outcomes, with select representative quotations, by level of the social ecological model with interactions across levels highlighted

| Individual |

|

Improved knowledge of modern contraceptives included its positive influence on relationship, economic, and physical health and reduced misinformation about side effects, resulting in more positive attitudes towards and intentions to use family planning. Individual-level change positively interacted with relationship strengthening content to influence relationship-level change (e.g., communication with partner). • “I got to understand that when you produce so many children, your income is affected and developing yourself may not be easy. It is good to give birth to the children whom we can plan for and educate well. I learned that, with many children, your relationship at home is negatively affected” (Interview, Man). • “Many of us were scared of family planning. We thought it causes cancer, loss of sexual appetite, and so many other things. When the doctor and midwife told us the truth about family planning, this also made it easy for us to discuss with our spouses. The fear of using family planning went away” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). |

|

Changes in personal endorsement of gender inequitable attitudes was apparent through qualitative narratives and resulted in changed relationship dynamics (see interpersonal-level) • “Before the program, I didn’t know that a man can also listen to a woman’s decisions. I had this saying in me: ‘Omukazi tansalirawo’ [translation: a woman cannot make a decision for me]” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). Shifts in rigid gender roles allowed for more acceptance of men’s involvement in learning about and participating in sexual and reproductive health care and family planning, moving men away from the idea that family planning is for women only. • “We men would feel shy to escort a woman to the hospital. We would find it awkward that you go together for family planning. But after being taught, I personally found it necessary to go together since this issue concerns both of us and it is for our wellbeing” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). |

| Interpersonal |

|

The effect of reduced gender inequitable attitudes was evident in relationship dynamics, with positive changes spanning communication, shared decision-making, more equitable division of labor, reduced intimate partner violence, and less reproductive coercion (women being forced to stop contraceptive use), having positive effects on men and women’s communication about family planning and shared decision-making. • Equitable communication and decision-making: “I want to talk about our culture. There is a saying in our language of the Baganda [tribe], ‘Omusajja tadibwaamu’ [translation: When a man is rebuking you, a woman, you are supposed to only submit and don’t dare to answer back]. But after the program, our men learned with us about good communication skills that help us to achieve a successful family. [Our husbands] now allow us to talk back and even listen to us. My husband these day listens to me, which was not the case before” (Women’s Focus Group Discussion). • Division of labor/gender roles: “I used to struggle with whom to leave my baby, whenever I was to go distribute the evening foods and teas at our trading center. Yet, it would earn us some money. Sometimes I would fail to go, because there was no one to leave my baby with. After the study, I now see a change. Whenever my husband is free, he takes care of our baby. It worked for us” (Women’s Focus Group Discussion). • Division of labor/gender roles: “Before the program came, I never wanted my wife to work. I listened carefully to the program’s teachings, and realized that, single-handedly, I cannot manage to sustain my family. I got some money, and got a place for my wife to sell charcoal and she is doing well. It helped me to improve the well-being of my home. Sometimes, I even borrow money from her business, when things are not working very well in my business and, later, I return it” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). • Violence: “I never used to mind about what or how my wife feels. If she is pregnant, I could not escort her to the health center. If she is not interested in having sex, that is not my problem; she has to do it. But the midwife pointed out some of these issues are the source of violence in homes. When there is violence in a home, family planning [broad program definition of planning for one’s future] is hindered since there is no agreement and no good communication” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). Beyond the relationship effects achieved through changed gender attitudes, the intervention had direct effects on improved communication skills overall and the ability to make joint-decisions on family planning together, attributed to communication skill building content and the “Family Action Plan” (couple goal setting). • “The fact that [my spouse and I] sit and dialogue together, I no longer dictate to her and even we decide together. This is to say that the good communication we have provides a conducive atmosphere for any discussion, even inclusive of family planning” (Interview, Man). • “You taught us how to set our goals with our spouses. We had to agree on the number of children to have, but also to know, which intervals we are to have them” (Women’s Focus Group Discussion). |

| Community |

|

The group dialogues aimed to reshape specific community norms that reinforce large family size and gender inequity, and were counter to using family planning. The following excerpt shows select examples of community beliefs that were the subject of community dialogues (beliefs underlined) that were reshaped through dialogues to align with the program’s definition of family success. This particular excerpt demonstrates the effectiveness of examining these norms in the broader context of poverty and changing economic conditions. • “Participant: I come from an extended family, where my ancestors and immediate relatives believe in big family size. All those things you talked about in our culture are still being valued and practiced. About men being decision makers on everything, men looked at to have as many wives and as many children as their fathers, a man with many children considered to be with honor, and that, the more children you have, the more the chances of getting some of them with special blessings. My mind set was also in sync with those beliefs, before the sessions on community norms. Moderator: So how effective or ineffective was the discussion on this aspect? Participant: After the sessions on it, I did not remain the same. We are living in another era, where so many things, as you taught us, have changed. The land is smaller, the resources are limited, the cost of living has gone up, and I noticed that I don’t have the capacity any more to afford a large family size. I noticed that I cannot afford to fulfill what religion demands” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). The group dialogues also aimed to redefine definitions of a “successful family” to be one that includes planning for the future, inclusive of family planning. • “Before this program came, for me I had decided to have as many children as I wished, but when they taught us about family planning and its benefits, I realized that, that’s not the best way to manage the family” (Men’s Focus Group Discussion). |

Individual

There was a statistically significant time by intervention effect on all individual-level variables, including knowledge of contraceptive methods favoring the intervention overall (Wald χ2 = 35.20, p < 0.001) and at both time points (7-months: b = 0.41, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 10-months: b = 0.40, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001); this effect was stronger for men in the intervention, whose knowledge was lower than women’s at baseline, as depicted in Figure 3a and indicated by the intervention*time*gender interaction (baseline: b = 0.15, SE = 0.07, p = 0.04; 7-months: − b = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p<0.001; 10-months: b = − 0.13, SE = 0.04, p = 0.001). Positive family planning attitudes increased more in the intervention compared to the comparator at all time points (Wald χ2 = 64.53, p < 0.001; 7-months: b = 1.08, SE = 0.14; p<0.001); 10-months: b = 0.79, SE = 0.14, p < 0.001) (Figure 3b). Participants in the intervention had a greater increase in intentions to use family planning overall (Wald χ2 = 48.26, p < 0.001) and at 7-months (b = 0.68, SE = 0.12, p<0.001) and 10-months (b = 0.20, SE = 0.10, p = 0.04), with a significant gender interaction at 7-months for the intervention arm (b = 0.19, SE = 0.09, p = 0.04) due to a slightly greater increase among women compared to men (Figure 3c).

The intervention’s positive impact on both women and men’s contraceptive knowledge, family planning attitudes, and intentions to use family planning was apparent in the qualitative narratives. Participants displayed increased awareness of the importance of family planning on family health and development, spanning physical, relationship, and economic health, which positively influenced their attitudes and intentions towards family planning (see quote in Table 4). Participants also demonstrated increased knowledge of effective methods and reduced contraceptive myths and fear of side effects, which they attributed to FH=FW’s family planning education. The excerpt from one of the men’s focus group discussions in Table 4 showcases how these individual-level changes had positive effects on the interpersonal-level, with increased knowledge of methods and men’s resulting acceptance of family planning making it possible for couples to engage in family planning discussions.

Despite these positive changes, side effect fears were still a concern among some participants. The intervention had provided two sessions of family planning education to women (one with women only, and one with women and men together), and thus only one session to men. Women provided feedback that it would be beneficial to include a men’s only family planning education session as well, and men expressed interest in more time being dedicating to learning about family planning methods.

In addition, a statistically significant time by intervention effect was observed on inequitable gender attitudes, which reduced in the intervention compared to control (Wald χ2 = 19.46, p < 0.001; 7-months: b = −0.13, SE = 0.05, p=0.008; 10-months: b = −0.17, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001) (Figure 3d). Changes in men and women’s endorsement of traditional gender norms and roles were evident in qualitative narratives. Many men stated that the program helped them understand the importance of gender equity, healthy communication, and shared decision-making to family health and development. As demonstrated by the quotation in Table 4, these changes were counter to prevailing norms about men and women’s roles and relationships. There were also demonstrated shifts in attitudes around rigid gender role fulfillment, with increased acceptance of women working and engaging in financial matters, and men helping with tasks traditionally for women, like childrearing, household chores, and engaging in sexual and reproductive health including family planning, typically viewed as a women’s domain. Table 4 includes a representative quotation that highlights changed attitudes towards men’s role in family planning. Table 4 quotations under interpersonal-level also demonstrate changed gender attitudes, which were necessary to change in order to positively effect equitable relationship dynamics (discussed next).

Interpersonal

At the interpersonal-level, partner communication about family planning increased more in the intervention compared to the comparator overall (Wald χ2 = 78.81, p < 0.001) and at all time points 7-months: b = 1.19, SE = 0.18, p < 0.001; 10-months: b = 1.65, SE = 0.19, p = 0.001) (Figure 3e). There was an overall statistically significant intervention*time effect on increased shared household decision-making (Wald χ2 = 13.40, p = 0.001), which was trending towards significance at 7-months (b = 0.13, SE = 0.07, p = 0.07) and statistically significant at 10-months (b = 0.21, SE = 0.06, p<0.001) (Figure 3f). The qualitative data corroborated these findings by revealing interpersonal-level changes in couple dynamics that resulted, at least in part, from decreased gender inequitable attitudes (as discussed previously). While some participants stated that they still had relationship challenges, many shared examples of more equitable relationship dynamics in communication, shared decision-making, a more equitable division of labor and gender role reversal, and reduced intimate partner violence (see Table 4 for illustrative examples).

Both men and women felt the program increased their skills in communicating with their partner, and that the “Family Action Plan,” where couples set physical, relationship, and economic health goals together, also facilitated shared decision-making, including decisions specific to fertility desires, pregnancy timing/spacing, and contraceptive use (see Table 4 quotes). These skills, paired with more equitable relationship dynamics, seemed to lead to shared decision-making about family planning. Evidence of the intervention’s effects on communication and shared decision-making translating to family planning outcomes was also observed through the quantitative measure of fertility discordance; the time*intervention effect on fertility discordance between partners, measured at the dyad-level (one per couple), was overall statistically significant (Wald χ2 = 10.42, p = 0.005), trending towards significance at 7-months and not significant at 10-months (7-months: AOR = 1.36, 95% CI = 0.99–1.85, p = 0.05; 10-months: AOR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.75–1.22, p = 0.71) (Figure 3g).

Community

At the community-level, perceived acceptance of family planning (norms) increased in the intervention compared to the comparator group overall (Wald χ2 = 23.89, p < 0.001) and at both time points (7-months: b = 0.31, SE = 0.06, p<0.001; 10-months: b = 0.19, SE = 0.05, p<0.001) (Figure 3h). In addition to changing the perception of community acceptance of family planning, the intervention included facilitated discussions (i.e., dialogues) aimed to reshape prevalent community norms that reinforce large family size expectations. Although endorsement of some of traditional beliefs were still apparent in focus group and individual interview narratives, the qualitative data demonstrated overall success in reshaping the beliefs targeted by the program. Table 4‘s excerpt showcases select community beliefs that were the subject of the dialogues with a quotation that signifies a participant’s change in their personal endorsement of these beliefs. Overall, participants shared how the intervention helped them to rethink traditional expectations about family size in relation to their larger goals for family health and development, especially in the broader context of poverty and changing economic conditions, and include family planning as part of the definition of a successful family, as exemplified by the final quotations in Table 4.

Discussion

We aimed to examine the preliminary effects of a community-based, multi-level family planning intervention on theoretically-grounded intermediate family planning outcomes through a mixed methods embedded experimental design, mixing qualitative data with quantitative data collected through a quasi-experimental controlled trial. This evaluation provides initial support for the FH=FW intervention’s positive effects on multi-level family planning determinants among couples in rural Uganda, through observed changes in individual, interpersonal, and community-level factors through 10-months follow-up. While these findings are only preliminary, given the pilot trial’s sample size, nearly all hypothesized intervention effects were statistically significant; while some effects were tempered by 10-months, most were maintained. These findings were supported and expanded on with qualitative data, which highlighted the intervention’s effects across, and interactions between, social ecological levels, as well as the effect of dialogues grounded in the social psychological theory of transformative communication (25) on reshaping definitions of a successful family and on reducing endorsement of specific community norms that are counter to family planning acceptance in this setting.

FH=FW was designed to address multi-level barriers to family planning previously identified in this rural setting in Uganda (11–13) and common in low-income settings with a high unmet need for family planning (42). At the individual-level, the intervention was successful at increasing knowledge of effective contraceptives, positive attitudes towards family planning, and participants’ intentions to use family planning in the future relative to comparator intervention participants. The intervention included directive family planning education provided from an intervention facilitator and a local health worker covering all modern methods available locally, including their efficacy, side effects, proper use, advantages and disadvantages, and where they can be accessed locally. Dispelling misinformation and common myths about side effects likely contributed to the observed increase in positive attitudes towards family planning in the FH=FW vs. comparator arm. These findings are an important contribution to the literature, as high levels of misinformation about contraceptives are reported in sub-Saharan Africa where the unmet need for family planning is high (43–45). Other studies have similarly found engaging women and men in family planning education and diffusing information through social networks may be acceptable approaches in other African settings to dispel family planning misinformation (46–48).

In our intervention, more education content was given to women than men, as our preliminary work suggested that too much family planning education might make men lose interest in the program. In contrast, men expressed interest in learning more about family planning, and participants recommended men receive the same amount of time dedicated to family planning education as women. The common narrative that men are not interested in family planning may reflect the fact that family planning programs are seldom tailored to men’s reproductive needs (49). Moreover, men who oppose family planning may be the least informed about it (50). FH=FW engaged both men and women’s reproductive needs and included content designed to emphasize family planning’s positive impacts on physical health, relationship health, and economic health to engage both of their interests. We employed numerous approaches to engaging men that have similarly been supported by prior research in the region. Specific strategies with support (and thus used in our approach) include tailoring messaging to men’s interests (e.g., family planning’s economic benefits, male reproductive health) (51, 52), improving partner communication (53, 54) and gender equity (29, 46, 55, 56), mobilizing via religious/community leaders, community health workers, and other men (47, 51, 57–60), and bringing services to communities (61). Future research should continue to examine these approaches; the use of study designs that can differentiate between the effects of these approaches would fill a gap in the literature.

The study’s qualitative data revealed that increasing male acceptance and knowledge of family planning also positively influenced the interpersonal-level family planning determinants, by increasing couples’ ability to discuss family planning together. FH=FW included content aimed to improve couple’s communication skills and their ability and willingness to make important family decisions together. The success of these strategies is demonstrated by FH=FW participants’ increased communication about family planning and shared household decision-making with their spouse at both follow-ups relative to the comparator participants. These observed interpersonal-level changes were likely also the product of the FH=FW intervention’s gender transformative intervention content aimed to reshape community norms specific to gender norms and roles that underpin inequitable dynamics between men and women.

Strategies used by FH=FW including transformative community dialogues, gender equitable role modeling through vignettes, couples-focused activities to improve gender equitable communication and decision-making, and endorsement of the importance of spousal harmony and equity through community leaders. There was evidence of a potential intervention effect on reduced gender inequitable attitudes among both men and women among FH=FW participants relative to the comparator, and the qualitative data made clear that increasing participants’ understanding of the value of gender equitable relationships was necessary to improve spousal communication and decision-making. These findings add to a growing body of literature that demonstrates gender transformative approaches with couples and communities can improve individual gender attitudes, couple dynamics and reduced partner violence, and have subsequent positive effects on sexual and reproductive health outcomes (62, 63).

Given the pilot nature of the study, we are not able to examine true community-level changes on community norms. However, we did find a significant preliminary intervention effect on perceived community norms about family planning (i.e., perceived acceptance of family planning among others) among FH=FW participants relative to comparator participants. As a proxy for community-level change, we also qualitatively examined change in individual endorsement of the community norms targeted for change by our facilitated group dialogues. The study’s qualitative findings supported the intervention’s success in using dialogues grounded in transformative communication (25) to reshape endorsement of common community norms and beliefs that reduce family planning acceptance, while reshaping definitions of a successful family to focus on planning for one’s future, inclusive of planning the number and timing of children. These preliminary findings provide support that, if scaled-up, this approach could go beyond the individual-level to more broadly impact community norms that impede contraceptive use. Recent pilots support the feasibility and acceptability of using the approach to promote family planning in sub-Saharan Africa (64–66). Two studies in Kenya examined the effect of dialogues on family planning outcomes: one study reported more facility-level uptake of family planning post-intervention and another found 1.78 times higher odds of contraceptive use post-intervention for women, but was not effective for men (46, 67). However, neither study had a comparator group, highlighting the need for more rigorous trials to establish the effects of community dialogues on relevant family planning outcomes.

Limitations

This quasi-experimental controlled pilot trial was powered following guidelines for Stage 1b Pilot Trials (37), which are focused on gathering evidence for feasibility and acceptability of intervention and trial procedures, and trends towards change (feasibility, acceptability, and effects on contraceptive use have been reported in a separate manuscript) (39). Thus, it is limited in its small sample size not powered to fully detect change in our outcomes and its randomization of only two communities (increasing risk of confounding). This analysis is therefore not a full empirical test of the intervention’s conceptual model, which would require a larger sample size to support path analysis to test mediators of the intervention’s effect on contraceptive use. In addition, recall and social desirability bias may have influenced participants’ responses on measures, which were self-reported. It is also difficult to fully mask participants and research staff to the purpose of community-based interventions and the allocation of the two communities to treatment arm. Observed changes in the comparator group on some outcomes could be explained by measurement reactivity, external factors affecting district-level change, or positive comparator intervention effects. Despite these limitations, the results provide preliminary support for the study’s conceptual model by demonstrating change or trends towards change on the hypothesized intermediate determinants of contraceptive uptake. However, these findings need to be replicated and expanded upon in a future community efficacy trial that is fully powered to detect change in our outcomes.

Conclusions

While there are significant multi-level barriers to contraceptive use in Uganda and other LMICs, there are few theory-driven family planning interventions that take a multi-level approach to targeting change across the social ecological model (22). This mixed methods pilot evaluation of the theory-driven, multi-level FH=FW intervention provides strong preliminary support for the intervention’s theoretically-grounded conceptual model and ability to affect change across individual, interpersonal, and community-level drivers of a high unmet need for family planning. Future studies should consider exploring combined couples- and community-focused approaches to target knowledge gaps, relationship equity, and broader community and gender norms that interact to impede autonomous contraceptive use in settings like Uganda. If found efficacious in a future, fully powered trial, this intervention could have significant public health benefits if brought to scale.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD098523 (PIs: Sileo & Kiene). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the couples who participated in this study for their time and feedback. We thank the group facilitators, Rose Byaruhanga and Susan Mutesi, as well as the research assistants, Olivia Mulumba and Rachel Akoberwa, for their hard work and dedication to this study. The study received continuous support from the District Health Team, as well as the In-Charges and staff at the health facilities in each participating village. We are grateful for the feedback and guidance provided by the members of the Intervention Steering Committee created for this study. Finally, we thank the family planning stakeholders and community members that helped in mobilizing the community and co-facilitating sessions, including midwives, VHTs, local business experts, and religious and elected leaders.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts to declare.

Data availability statement:

The quantitative data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article. The qualitative data reported in this paper will not be shared due to ethical concerns regarding the privacy of the participants.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Family Planning/Contraception: Fact Sheet. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starbird E, Norton M, Marcus R. Investing in family planning: Key to achieving the sustainable development goals. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2016;4(2):191–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations DoEaSAPD. Family Planning and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Data Booklet. United Nations. Retreived from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/familyPlanning_DataBooklet_2019.pdf (Access date: 10 Nov 2022). 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. Country Comparison: Total Fertility Rate (est 2022). Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/about/archives/2021/field/total-fertility-rate/country-comparison. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Family Planning 2030. Track 20: Uganda: Family Plannng 2030; 2022 [Available from: http://www.track20.org/Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brofenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(513–531). [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLeroy KR BD, Steckler A, Glanz KA. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokols D Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol. 1992;47(1):6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thummalachetty N, Mathur S, Mullinax M, DeCosta K, Nakyanjo N, Lutalo T, et al. Contraceptive knowledge, perceptions, and concerns among men in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kibira SP, Muhumuza C, Bukenya JN, Atuyambe LM. “I Spent a Full Month Bleeding, I Thought I Was Going to Die...” A Qualitative Study of Experiences of Women Using Modern Contraception in Wakiso District, Uganda. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sileo KM, Wanyenze RK, Lule H, & Kiene SM (2015). Determinants of family planning service uptake and use of contraceptives among postpartum women in rural Uganda. International Journal of Public Health, 60(8), 987–997. https://doi-org.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/10.1007/s00038-015-0683-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sileo KM, Wanyenze RK, Lule H, & Kiene SM (2016). “That would be good but most men are afraid of coming to the clinic”: Men and women’s perspectives on strategies to increase male involvement in women’s reproductive health services in rural Uganda. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(12), 1552–1562. https://doi-org.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/10.1177/1359105316630297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiene SM, Hopwood S, Lule H, & Wanyenze RK (2013). An empirical test of the theory of planned behaviour applied to contraceptive use in rural Uganda. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(12), 1564–1575. https://doi-org.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/10.1177/1359105313495906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kriel Y, Milford C, Cordero J, Suleman F, Beksinska M, Steyn P, et al. Male partner influence on family planning and contraceptive use: perspectives from community members and healthcare providers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Namasivayam A, Schluter PJ, Namutamba S, Lovell S. Understanding the contextual and cultural influences on women’s modern contraceptive use in East Uganda: A qualitative study. PLOS Global Public Health. 2022;2(8):e0000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silumbwe A, Nkole T, Munakampe MN, Milford C, Cordero JP, Kriel Y, et al. Community and health systems barriers and enablers to family planning and contraceptive services provision and use in Kabwe District, Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper C. A guide for planning and implementing social and behavior change communication activities for postpartum family planning. Jhpiego Corporation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Tumwesigye NM, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Constraints and prospects for contraceptive service provision to young people in Uganda: providers’ perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nalwadda G, Tumwesigye NM, Faxelid E, Byamugisha J, Mirembe F. Quality of Care in Contraceptive Services Provided to Young People in Two Ugandan Districts: A Simulated Client Study. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutaremwa G, Wandera SO, Jhamba T, Akiror E, Kiconco A. Determinants of maternal health services utilization in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elewonibi B, Sato R, Manongi R, Msuya S, Shah I, Canning D. The distance-quality trade-off in women’s choice of family planning provider in North Eastern Tanzania. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(2):e002149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholmerich VL, Kawachi I. Translating the Social-Ecological Perspective Into Multilevel Interventions for Family Planning: How Far Are We? Health Educ Behav. 2016;43(3):246–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIPs). Community Group Engagement: Changing Norms to Improve Sexual and Reproductive Health. Washington, DC: USAID; 2016. Oct. Available from: https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CommunityGroupEngagement.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNDP. Upscaling Community Conversations in Ethiopia: Unleashing Capacities of Communities for the HIV/AIDS Response. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: UNDP; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell C, Cornish F. How can community health programmes build enabling environments for transformative communication? Experiences from India and South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):847–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dialogue Vaughan C., critical consciousness and praxis. In: D .Hook BF, Bauer M. editor. Social psychology of communication Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2010. p. 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underwood C, Brown J, Sherard D, Tushabe B, Abdur-Rahman A. Reconstructing gender norms through ritual communication: a study of African transformation. J Comm. 2011;61(2):197–218. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueroa ME, Poppe P, Carrasco M, Pinho MD, Massingue F, Tanque M, et al. Effectiveness of Community Dialogue in Changing Gender and Sexual Norms for HIV Prevention: Evaluation of the Tchova Tchova Program in Mozambique. Journal of Health Communication. 2016;21(5):554–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuler SR, Nanda G, Ramirez LF, Chen M. Interactive workshops to promote gender equity and family planning in rural Guatemalan Communities: Results of a community randomized trial. J Biosoc Sci. 2015;47(5):667–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tesfaye AM. Using community conversation in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Journal of Development and Communication Studies. 2013;2(2–3). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell C, Scott K, Nhamo M, Nyamukapa C, Madanhire C, Skovdal M, et al. Social capital and HIV Competent Communities: The role of community groups in managing HIV/AIDS in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2013;25(sup1):S114–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S, Sibiya Z. Supporting people with AIDS and their carers in rural South Africa: possibilities and challenges. Health Place. 2008;14(3):507–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutale W, Masoso C, Mwanza B, Chirwa C, Mwaba L, Siwale Z, et al. Exploring community participation in project design: application of the community conversation approach to improve maternal and newborn health in Zambia. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UN Women M. Advancing Gender Equality: Promising Practices, Case Studes from the Millennium Development Goals Achievementt Fund. Application of the Community Conversation Enhancement Methodology for Gender Equality in Namibia. New York: UN Women; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell C, Nhamo M, Scott K, Madanhire C, Nyamukapa C, Skovdal M, et al. The role of community conversations in facilitating local HIV competence: case study from rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creswell J, Plano Clark V. Designing and Conduction Mixed Methods Research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(133–142). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sileo KM, Muhumuza C, Sekamatte, Lule H, Wanyenze R. Kershaw K, Kiene TS, S. M. (2022). The “Family Health = Family Wealth” intervention: Study protocol for a pilot quasi-experimental controlled trial of a multi-level, community-based family planning intervention for couples in rural Uganda. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 8(1). https://doi-org.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/10.1186/s40814-022-01226-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sileo KM, Muhumuza C, Wanyenze RK, Kershaw TS, Sekamatte S, Lule H, & Kiene SM (2023). A pilot quasi-experimental controlled trial of a community-based, multilevel family planning intervention for couples in rural Uganda: Evidence of feasibility, acceptability, and effect on contraceptive uptake among those with an unmet need for family planning. Contraception, 125, 110096. https://doi-org.libweb.lib.utsa.edu/10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amhara National Regional Sate Health Bureau. Training Manual on Hygiene and Sanitation Promotion and Community Mobilization for Volunteer Communtity Health Promotors (VCHP_. Amhara Regional Health Bureau, Bahir-Dar, Ethiopia: USAID, Water and Sanitation Program (WSP); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wulifan JK, Brenner S, Jahn A, De Allegri M. A scoping review on determinants of unmet need for family planning among women of reproductive age in low and middle income countries. BMC Women’s Health. 2016;16(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sedlander E, Bingenheimer JB, Thiongo M, Gichangi P, Rimal RN, Edberg M, et al. “They Destroy the Reproductive System”: Exploring the Belief that Modern Contraceptive Use Causes Infertility. Studies in Family Planning. 2018;49(4):345–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz J, Dumbaugh M, Bapolisi W, Ndorere MS, Mwamini MC, Bisimwa G, et al. “So that’s why I’m scared of these methods”: Locating contraceptive side effects in embodied life circumstances in Burundi and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Soc Sci Med. 2019;220:264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sedlander E, Bingenheimer JB, Lahiri S, Thiongo M, Gichangi P, Munar W, et al. Does the Belief That Contraceptive Use Causes Infertility Actually Affect Use? Findings from a Social Network Study in Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 2021;52(3):343–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wegs C, Creanga AA, Galavotti C, Wamalwa E. Community dialogue to shift social norms and enable family planning: an evaluation of the family planning results initiative in Kenya. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0153907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim TY, Igras S, Barker KM, Diakité M, Lundgren RI. The power of women’s and men’s Social Networks to catalyse normative and behavioural change: evaluation of an intervention addressing Unmet need for Family Planning in Benin. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrington EK, McCoy EE, Drake AL, Matemo D, John-Stewart G, Kinuthia J, et al. Engaging men in an mHealth approach to support postpartum family planning among couples in Kenya: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hardee K, Croce-Galis M, Gay J. Are men well served by family planning programs? Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]