Abstract

Background

Patients with 22q11.2 microduplication syndrome exhibit a high degree of phenotypic heterogeneity and incomplete penetrance, making prenatal diagnosis challenging due to phenotypic variability. This report aims to raise awareness among prenatal diagnostic practitioners regarding the variant's complexity, providing a basis for prenatal genetic counseling.

Methods

Family and clinical data of 31 fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplications confirmed by chromosomal microarray between June 2017 and June 2023 were considered.

Results

Primary prenatal ultrasound features of affected fetuses include variable cardiac and cardiovascular anomalies, increased nuchal translucency (≥3 mm), renal abnormalities, and polyhydramnios. More than half of fetuses considered showed no intrauterine manifestations; therefore, prenatal diagnostic indicators were primarily advanced maternal age or high‐risk Down syndrome screening. Most fetuses had microduplications in proximal or central 22q11.2 regions, with only three cases with distal microduplications. Among parents of fetuses considered, 87% (27/31) continued the pregnancy. During follow‐up, 19 cases remained clinically asymptomatic.

Conclusion

Nonspecific 22q11.2 microduplication features in fetuses and its mild postnatal disease presentation highlight the need to cautiously approach prenatal diagnosis and pregnancy decision‐making. Increased clinical efforts should be made regarding providing parents with specialized genetic counseling, long‐term follow‐up, and fetal risk information.

Keywords: 22q11.2 microduplication, chromosomal microarray analysis, prenatal diagnosis, rearrangement

Patients with 22q11.2 microduplication syndrome exhibit a high degree of phenotypic heterogeneity and incomplete penetrance, making prenatal diagnosis challenging due to phenotypic variability. This retrospective study aimed to clarify ultrasound features and maternal characteristics associated with 22q11.2 microduplication in Chinese fetuses. Primary prenatal ultrasound features of affected fetuses include variable cardiac and cardiovascular anomalies, increased nuchal translucency (≥3 mm), renal abnormalities, and polyhydramnios. More than half of fetuses considered showed no intrauterine manifestations; therefore, prenatal diagnostic indicators were primarily advanced maternal age or high‐risk Down syndrome screening. Most fetuses had microduplications in proximal or central 22q11.2 regions, with only three cases with distal microduplications. Among parents of fetuses considered, 87% (27/31) continued the pregnancy. During follow‐up, 19 cases remained clinically asymptomatic. Nonspecific 22q11.2 microduplication features in fetuses and its mild postnatal disease presentation highlight the need to cautiously approach prenatal diagnosis and pregnancy decision‐making.

1. INTRODUCTION

Variants of 22q11.2 microduplications result from non‐allelic homologous recombination mediated by low‐copy repeats (LCRs) on chromosome 22 (Edelmann et al., 1999). The genomic structure of the 22q11.2 region is complex, comprising a total of eight LCRs, denoted as LCRs A‐H (A‐D for proximal and E‐H for distal LCRs) (Shaikh et al., 2000, 2007). Deletion of proximal LCRs in the 22q11.2 region can lead to severe phenotypes including DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) and velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS), with knowledge of possible phenotypes currently expanding (McDonald‐McGinn et al., 2015). In contrast, individuals with 22q11.2 microduplication variants often exhibit milder phenotypes, ranging from mild intellectual or learning disabilities, developmental delay, growth retardation, and hypotonia to multisystem malformations, including congenital heart disease (CHD), urogenital anomalies, and facial dysmorphisms with or without cleft palate (Ou et al., 2008; Pinchefsky et al., 2017; Wentzel et al., 2008). Therefore, 22q11.2 microduplication can result in nonspecific and highly variable clinical presentations, posing diagnostic challenges (Bartik et al., 2022).

Currently, prenatal diagnostic cohort studies related to 22q11.2 microduplication are relatively rare. This is due to the uncertain nature of fetal development and the high variability of disease phenotypes, making 22q11.2 microduplication variants easily overlooked during prenatal diagnosis, thereby limiting the early assessment and clinical management of potential issues (Li et al., 2019, 2020; Wentzel et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2021).

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed intrauterine phenotypes, copy number variation (CNV), prenatal diagnostic indicators, pregnancy outcomes, and postnatal clinical presentations of 31 fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplication. We also report prenatal diagnostic indicators of pregnant mothers. By combining these data with those of previously published cohort studies, we summarize the prenatal clinical characteristics of fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplication. This report aims to raise awareness among prenatal diagnostic practitioners regarding the complexity of this variant and provide information needed to improve prenatal genetic counseling.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study subjects

Basic information on fetuses and parents who underwent prenatal diagnosis at the Medical Genetics Diagnosis and Treatment Center of Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital from June 2017 to June 2023 was collected. All included fetuses had normal karyotype analysis results and showed 22q11.2 microduplication via chromosomal microarray (CMA). Patients with CNVs related to phenotypes were excluded. This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. All pregnant women received genetic counseling and provided informed consent before undergoing invasive diagnostic procedures.

2.2. Prenatal ultrasound examination

A GE Voluson E10 ultrasound diagnostic device with a C29 probe (GE Healthcare Ultrasound Inc, WI, USA) operating at frequencies of 2–9 MHz was used for prenatal ultrasound investigations. Detailed obstetric ultrasound examinations were performed on fetuses with CMA results indicating 22q11.2 microduplication to determine the presence of fetal structural abnormalities and intrauterine phenotypes such as fetal growth restriction.

2.3. Invasive prenatal sampling

Samples were collected under ultrasound guidance, with chorionic villus sampling performed at 10–14 weeks of gestation (Case 20), amniocentesis at 16–28 weeks (the remaining 26 cases), and umbilical cord blood sampling at 26–35 weeks (Cases 1, 2, and 3).

2.4. CMA analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from samples using a MiniKit DNA extraction kit (Qigen Inc, Hilden, Germany). The concentration and purity of extracted DNA were measured using a NanoDrop UV spectrophotometer (Thermofisher Scientific Inc, MA, USA). Subsequently, experiments were conducted using the Affymetrix CytoScan 750K gene chip (Affymetrix Inc, CA, USA) in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Results of CMA testing were analyzed using Chromosome Analysis Suite software. Chromosomal microdeletions and microduplications were determined based on a scatterplot distribution of copy numbers. Comparative analysis of CNVs was performed based on the clinical significance of CNVs larger than 100 kb using established literature and public databases. Databases used included the following: OMIM (https://omim.org/), DECIPHER (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/), ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), and ClinGen Dosage Sensitivity Database (https://dosage.clinicalgenome.org). CNV pathogenicity was assessed according to guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

2.5. Literature review of prenatal cases with 22q11.2 microduplication

A literature review was conducted by searching for English language publications in the PubMed (http://www.nebi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and Europe PMC (https://europepmc.org/) databases using the following keywords: “22q11.2” and “22q11.2 microduplication.” Relevant data related to fetal phenotypes and 22q11.2 microduplication variants in prenatal diagnosis were collected.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General information of pregnant women and prenatal diagnostic indications

Among 29 pregnant women considered, the mean age was 31.2 ± 5.6 years (range: 20–44 years). The mean gestational age at prenatal diagnosis of 31 fetuses was 23.7 ± 4.7 weeks (range: 13–35 weeks). Among these, fetuses 18 and 19 were born to the same mother who conceived naturally and underwent prenatal diagnosis due to advanced maternal age. Ultrasonography revealed a monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy; therefore, both fetuses underwent invasive prenatal sampling. Fetuses 21 and 22 were born to the same mother through in vitro fertilization and the transfer of two fresh embryos. Ultrasonography showed a monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy, with one of the twins having unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney; therefore, both twins underwent invasive prenatal sampling. Other indications for invasive prenatal diagnosis are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

General information and prenatal diagnostic indications of the 29 pregnant women with fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplication.

| Case | Age | GA | Indications for interventional diagnosis | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 y | 26 w | High risk for DS: 1/620; fetal femur length and biparietal diameter smaller than normal | CB |

| 2 | 23 y | 30 w | NT thickening: 3.5 mm; intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, tumor‐like expansion of the intra‐abdominal segment of the umbilical vein; increased cardiothoracic ratio, mild tricuspid valve regurgitation; each measured value was less than expected; thickened placenta; many polyhydramnios | CB |

| 3 | 29 y | 35 w | Irregularly shaped fetal head; double renal pelvis could be seen in the left kidney | CB |

| 4 | 44 y | 18 w | Older pregnant woman; NT thickening: 3.3 mm | AF |

| 5 | 39 y | 20 w | Older pregnant woman | AF |

| 6 | 33 y | 22 w | High risk for DS: 1/56 | AF |

| 7 | 20 y | 20 w | High risk for DS: 1/71, history of children with developmental delays | AF |

| 8 | 27 y | 25 w | The embryo was stopped once | AF |

| 9 | 35 y | 23 w | Older pregnant women | AF |

| 10 | 24 y | 26 w | High risk for DS: 1/76 | AF |

| 11 | 24 y | 22 w | High risk for DS: 1/121 | AF |

| 12 | 37 y | 22 w | Older pregnant woman; embryonic termination once, genetic analysis of abortion product revealed dup(2)(p25.3q37.2) | AF |

| 13 | 31 y | 29 w | NT thickening: 3.3 mm; mild tricuspid valve regurgitation, mild pulmonary valve regurgitation | AF |

| 14 | 31 y | 26 w | High risk for DS: 1/94 | AF |

| 15 | 38 y | 23 w | Older pregnant woman; the fetus had a right arch with a left duct (U‐shaped vascular ring), a thin ductus arteriosus, and a vagus left subclavian artery | AF |

| 16 | 28 y | 30 w | Fetal right subclavian artery vagus | AF |

| 17 | 27 y | 26 w | NT thickening: 3.2 mm | AF |

| 18 | 42 y | 23 w | Older pregnant woman; natural conception, monochorionic diamniotic twins | AF |

| 19 | 42 y | 23 w | Older pregnant woman; natural conception, monochorionic diamniotic twins | AF |

| 20 | 28 y | 13 w | NT thickened to 5.2 mm; polyhydramnios | Villus |

| 21 | 29 y | 25 w | Two fresh embryos were transplanted following IVF‐ET; dichorionic diamniotic twins; polycystic dysplastic kidney on one side of fetus A | AF |

| 22 | 29 y | 25 w | Two fresh embryos were transplanted following IVF‐ET; dichorionic diamniotic twins, and ultrasound of the B fetus showed no abnormalities | AF |

| 23 | 30 y | 26 w | Fetal ventricular septal defect, slightly narrowed aortic valve | AF |

| 24 | 33 y | 21 w | High risk for DS: 1/113 | AF |

| 25 | 37 y | 18 w | Older pregnant women; adverse pregnancy and childbirth history | AF |

| 26 | 36 y | 18 w | Older pregnant women | AF |

| 27 | 30 y | 25 w | NT thickening: 3.2 mm; fast heart rate; mild separation of right renal collecting system; single umbilical artery | AF |

| 28 | 34 y | 19 w | High risk for DS: 1/54 | AF |

| 29 | 27 y | 18 w | Family history of epilepsy | AF |

| 30 | 30 y | 30 w | Fetal right subclavian artery vagus; left ventricular hyperechoic focus | AF |

| 31 | 31 y | 29 w | NT thickened to 3.3 mm; nasal bone missing | AF |

Abbreviations: AF, amniotic fluid; CB, cord blood; DS, Down syndrome; GA, gestational age; IVF‐ET, in vitro fertilization‐embryo transfer; NT, nuchal translucency; w, weeks; y, years.

3.2. Phenotypic information

Among 31 fetuses considered, 17 (54.8%) showed no abnormalities, and 14 exhibited abnormalities (45.2%) on ultrasound (Table 1). Among fetuses with identifiable abnormalities, seven had various degrees of CHD (12.9%, 4/31) and three displayed cardiovascular anomalies (9.7%, 3/31), including ventricular septal defects, mild tricuspid/pulmonary valve regurgitation, right‐sided aortic arch with left ductus arteriosus forming a U‐shaped vascular ring, right/left subclavian artery vagus, and focal hyperechoic spots in the left ventricle. Seven fetuses (22.6%, 7/31) had increased nuchal translucency (NT). Three fetuses (9.7%, 3/31) had renal system abnormalities, including one with bilateral renal pelvis dilation and an irregular head shape, one with a unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney, and one with mild separation of the right renal collecting system. Two fetuses (6.5%, 2/31) had intrauterine growth restriction, and one fetus (3.2%, 1/31) had an absent nasal bone.

3.3. Follow‐up

Among the 29 women carrying the 31 fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplication, four chose to terminate the pregnancy. The remaining 27 fetuses were delivered successfully. The age of children at their last follow‐up ranged from 2 months to 5 years. Growth and development information were assessed via telephone (information was not obtained for two children). These interviews showed that 19 children (76%, 19/25) showed normal growth and development, while six children (24%, 6/25) exhibited varying degrees of developmental abnormalities, including delays in language and psychomotor development, growth retardation, and intellectual disability. Information obtained during clinical follow‐up is summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Pregnancy outcomes and genetic testing results of 31 fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplication.

| Fetus | Outcome (delivery/sex/birth weight) | Follow‐up status | CMA results | Size | LCRs | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C‐section/male/2.73 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,800,471)×3,pat | 3.1 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 2 | Vaginal birth/female/2.8 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,459,713)×3,mat | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 3 | Vaginal birth/female/3.1 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,636,749–21,464,764)×3,dn | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 4 | C‐section/male/3.3 kg | Motor and language development delays | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,800,471)×3,dn | 3.1 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 5 | Vaginal birth/male/3.25 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,919,478–21,800,471)×3,dn | 2.9 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 6 | Vaginal birth/male/3.7 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,916,960–21,461,017)×3 | 2.5 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 7 | Vaginal birth/female/3.2 kg | Growth retardation | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,461,017)×3 | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 8 | Vaginal birth/female/2.28 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,461,017)×3,dn | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 9 | Vaginal birth/female/NA | Lost to follow‐up | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,454,872)×3,pat | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 10 | C‐section/female/2.9 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,916,477–21,915,207)×3,mat | 3.0 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 11 | C‐section/male/3.9 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,800,471)×3,pat | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 12 | Inducing labor | / | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,649,190–21,461,017)×3,dn | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 13 | Inducing labor | / | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,855–21,459,712)×3,dn | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 14 | Vaginal birth/female/3.15 kg | Language delay | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,636,749–21,464,764)×3,mat | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 15 | Inducing labor | / | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,649,189–20,312,661)×3 | 1.66 Mb | A‐B | P |

| 16 | C‐section/female/3.17 kg | Lost to follow‐up | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,856–21,915,207)×3 | 3.3 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 17 | C‐section/male/ | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,648,856–21,461,017)×3 | 2.8 Mb | A‐D | P |

| 18 | C‐section/female/2.4 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,970,562–20,312,661)×3 | 1.34 Mb | A‐B | P |

| 19 | C‐section/female/2.5 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(18,970,562–20,312,661)×3 | 1.34 Mb | A‐B | P |

| 20 | Vaginal birth/male/3.64 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(20,730,143–21,800,471)×3 | 1.0 Mb | B‐D | VUS |

| 21 | C‐section/male/3.08 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(20,730,143–21,800,471)×3 | 1.0 Mb | B‐D | VUS |

| 22 | C‐section/female/2.84 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(20,730,143–21,800,471)×3 | 1.0 Mb | B‐D | VUS |

| 23 | Vaginal birth/female/2.35 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(20,310,410–21,464,764)×3 | 1.15 Mb | B‐D | VUS |

| 24 | Vaginal birth/female/2.7 kg | Unable to stand, require rehabilitation treatment | arr[hg19]22q11.21(21,059,670–21,461,017)×3,mat | 401 kb | C‐D | VUS |

| 25 | Vaginal birth/female/3.1 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(21,059,670–21,800,471)×3 | 741 kb | C‐D | VUS |

| 26 | Vaginal birth/female/3.05 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(21,059,670–21,464,764)×3,mat | 405 kb | C‐D | VUS |

| 27 | C‐section/female/3.77 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(20,716,877_21,464,764)×3,mat | 748 kb | C‐D | VUS |

| 28 | Vaginal birth/male/3.56 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.21(21,029,657–21,464,764)×3,pat | 435 kb | C‐D | VUS |

| 29 | Vaginal birth/male/3.6 kg | Language delay | arr[hg19]22q11.22q11.23(22,997,928–25,080,077)×3 | 2.0 Mb | E‐F | VUS |

| 30 | Vaginal birth/male/3.0 kg | Physical examination showed normal development | arr[hg19]22q11.22q11.23(22,997,928–25,041,592)×3,dn | 2.0 Mb | E‐H | LP |

| 31 | Inducing labor | / | arr[hg19]22q11.22q11.23(22,997,928–25,002,659)×3,dn | 2.0 Mb | E‐H | LP |

3.4. Results of genetic testing

The size of 22q11.2 microduplications among the 31 fetuses considered ranged from 401 kb to 3.3 Mb. Among 22q11.2 variants, 28 microduplications were located in the proximal LCR region, including three in LCRA‐B, four in LCRB‐D, five in LCRC‐D, and 16 in LCRA‐D. The remaining three microduplications were located in the distal LCR region, including one in LCRE‐F and two in LCRE‐H (Figure 1). Fetus 14 had an additional 2.4 Mb deletion in the 11q23.3q24.1 region, which was determined to have been inherited from a phenotypically normal father. Among the 29 couples considered in this study, 19 underwent CMA verification. This assessment revealed that genetic abnormalities were inherited from phenotypically normal fathers in five cases and phenotypically normal mothers in six cases. There were eight cases in which de novo mutations occurred (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Localization and parental origin of the 22q chromosome duplication region in 31 fetal cases. A schematic representation of chromosome 22 (data derived from the UCSC Genome Browser 2009, GRCh37/hg19 assembly [http://www.genome.ucsc.edu]) is shown. The red box indicates the relevant region of the chromosome.

3.5. Literature review

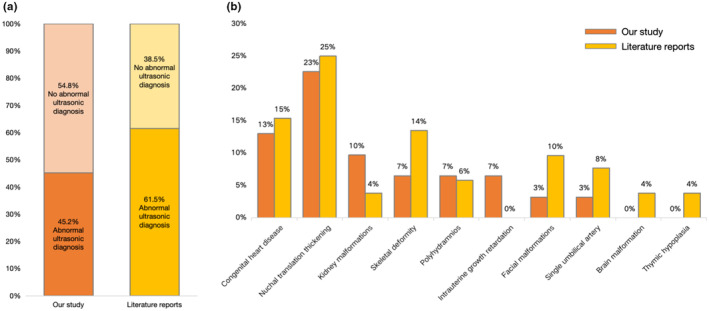

The PubMed database search for English articles reporting prenatal cases with 22q11.2 microduplication revealed four articles that included 52 clinical cases (Li et al., 2019, 2020; Wentzel et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2021). Among fetuses considered, 20 (38.5%, 20/52) showed no ultrasound abnormalities, while 32 (61.5%, 32/52) exhibited various ultrasound abnormalities in a variety of organ systems. Primary ultrasound findings included increased NT (25%, 13/52) and various types of CHD (15.4%, 8/52), including complex CHD, ventricular septal defects, or right‐sided aortic arch. Seven fetuses (13.5%, 7/52) had bone development abnormalities, primarily characterized by the absence of the nasal bone or poor long bone development. Five fetuses (9.6%, 5/52) had facial dysmorphisms, mainly featuring cleft lip and palate, four (7.7%, 4/52) had a single umbilical artery, three (5.8%, 3/52) had polyhydramnios, two (3.8%, 2/52) had brain structural abnormalities, two (3.8%, 2/52) had kidney anomalies, and two (3.8%, 2/52) had thymic hypoplasia. Additionally, one fetus (1.9%, 1/52) had an echogenic bowel (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Combined data from this study and previously published cases. (a) A comparison of non‐ultrasound and ultrasound abnormalities is shown to improve prenatal diagnostic indications for 22q11.2 microduplication and a (b) proportional distribution of abnormal ultrasound features in 22q11.2 microduplication is shown.

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings revealed that approximately 45% of fetuses with microduplications in the 22q11.2 region had observable abnormalities on ultrasound. The types of abnormalities observed tended to be related to growth rate and heart development. All continued pregnancies resulted in successful births, and on follow‐up, 76% of children exhibited normal growth and development. Developmental abnormalities reported in children included delayed development and CHD.

The 22q11.2 region is reportedly a “recombination hotspot” on this chromosome, where unique low‐copy repeats (LCRs) can lead to asymmetric homologous recombination during meiosis, resulting in events such as deletion, duplication, insertion, and translocation of adjacent DNA segments (Edelmann et al., 1999; Shaikh et al., 2000, 2007). This suggests that variations in the 22q11.2 region may occur at a relatively high frequency. The phenotypic differences caused by these deletions are substantial, predominantly manifesting as CHD, facial dysmorphisms, and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders, such as DGS and VCFS (Goldmuntz, 2020; McDonald‐McGinn et al., 2015). However, reports of 22q11.2 microduplications are relatively rare. This may be attributed to their high degree of variability and a lack of uniformity in resulting phenotypes. Clinical manifestations of 22q11.2 microduplications primarily include developmental or language disorders, behavioral issues, mild facial anomalies, hearing loss, and growth delays (Ou et al., 2008; Portnoï, 2009). The low penetrance and variability of fetal phenotypes complicate accurate prenatal diagnosis and genetic counseling.

In this study, 14 of 31 fetuses exhibited ultrasound abnormalities, primarily CHD and increased NT. The proportion of observable abnormalities via ultrasound in this study was similar to those reported previously (Li et al., 2019, 2020; Wentzel et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2021). The 22q11.2 microduplication region includes multiple OMIM genes, including TBX1, CRKL, PI4KA, LZTR1, SMARCB1, and IGLL1. TBX1 (OMIM 60254) is essential for the development of the main pulmonary trunk and the second heart field (SHF) by promoting robust interactions between the extracellular matrix and the cells in the second ventricle, which are crucial for SHF structural integrity and heart morphology (Alfano et al., 2019). In our study, we identified cardiovascular malformations, particularly aortic arch or ventricular septal defects, in seven fetuses, highlighting their significance as prenatal ultrasound indicators of 22q11.2 microduplications.

Beyond the frequently observed ultrasound features of 22q11.2 microduplications (CHD and increased NT), incidences of specific abnormalities vary across studies (Li et al., 2019, 2020; Wentzel et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2021). For example, in our study, we documented renal abnormalities (Cases 3, 21, and 27 showed bilateral renal pelvis, multicystic dysplastic kidney, and mild separation of the right renal collecting system, respectively) in three fetuses (9.7%), which exceeds previously reported incidences (3.8%, 2/52). This variability suggests a potential impact of 22q11.2 duplication on kidney development. Lopez‐Rivera et al. (2017) identified 22q11.2 deletions as significant contributors to congenital kidney defects, with genes such as SNAP29, AIFM3, and CRKL on LCRC‐D playing pivotal roles in kidney phenotypes (Lopez‐Rivera et al., 2017). Notably, all cases of fetal kidney abnormalities in our study involved duplications covering LCRC‐D (LCRA‐D, B‐D, C‐D). Further investigation is required to elucidate the mechanisms by which 22q11.2 microduplications affect kidney development. Additionally, other rare phenotypes such as skeletal abnormalities, facial anomalies, and thymic hypoplasia, although milder, resonate with conditions such as DGS or VCFS, indicating that gene dosage anomalies in the 22q11.2 region are critical determinants of clinical manifestations.

We also observed that over half of the fetuses (approximately 54.8%) with 22q11.2 microduplications exhibited no abnormalities on prenatal ultrasound, corroborating earlier reports that approximately 38% of fetuses appear normal (Li et al., 2019, 2020; Wentzel et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2021). Such findings reflect the low penetrance of fetal phenotypes associated with 22q11.2 microduplications and compound the challenges of prenatal diagnosis. In this study, fetuses without prenatal abnormalities were primarily subjected to prenatal diagnosis owing to advanced maternal age and high‐risk Down syndrome screening results. Additionally, the majority of these fetuses exhibited no postnatal abnormalities.

Among the families studied, 12 declined parental chromosomal verification. Of the remaining 19, eight exhibited de novo mutations (42.1%), five were paternal (26.3%), and six were maternal (31.6%), highlighting a high prevalence of de novo mutations, consistent with the high frequency of chromosomal rearrangements observed in the 22q11.2 region. Data indicate a de novo deletion mutation rate in this region of up to 2.5 per 10,000 in the general population. Therefore, the probability of observing de novo duplication mutations is likely high (Emanuel, 2008). Although a clear relationship between 22q11.2 microduplication genotypes and phenotypes has not been established, the phenotypic normalcy of most carrier parents complicates the elucidation of the pathogenicity of the variant. The relative rarity of reported prenatal diagnoses of 22q11.2 microduplication, combined with the high frequency of de novo mutations and the absence of observable phenotypes in most cases, suggests that the actual occurrence of 22q11.2 microduplication mutations may be underreported (Li et al., 2019, 2020; Wentzel et al., 2008; Xue et al., 2021).

For prenatal diagnosis, timely identification and confirmation of 22q11.2 microduplications are crucial, and effective communication of potential pregnancy risks to expectant mothers is imperative. The data reported here combined with findings from previous research confirm that increased NT and CHD are vital ultrasound markers of fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplications. Other features, such as renal or skeletal abnormalities, vary among studies but offer potential for identifying fetuses with likely 22q11.2 microduplications. Additionally, pregnant women of advanced age (≥35 years) or those identified with risk factors through Down syndrome screening may benefit from CNV screening. We recommended that fetuses identified with 22q11.2 microduplication during early pregnancy verify the origin of the variant. This verification will enhance the foundation for assessing the pathogenicity of the variant. Concurrently, routine prenatal monitoring is imperative to detect any potential structural anomalies, thereby facilitating a decision regarding the continuation of pregnancy.

In summary, through a retrospective study of 31 fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplications and an assessment of previously published cases, we elucidated the prenatal ultrasound features, interventional indicators, pregnancy outcomes, and postnatal clinical manifestations. The primary ultrasound features observed in most fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplications were increased NT and CHD. However, the low penetrance and high heterogeneity of phenotypes render predicting the occurrence and development of these conditions challenging. Although most fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplications exhibited no evident disease manifestations after birth, the possibility that conditions may be overlooked owing to the relatively short follow‐up period is considered. Therefore, caution is required when conducting prenatal diagnoses and providing genetic counseling for parents of fetuses with 22q11.2 microduplications.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Xiali Jiang: Conceptualization, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Bin Liang, Shuqiong He, Xiaoqing Wu, Wantong Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology. Huili Xue, Yan Wang, Na Lin: Investigation. Na Lin, Hailong Huang: Validation. Bin Liang, Liangpu Xu: Resources. Wantong Zhao, Huili Xue, Yan Wang: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Bin Liang, Liangpu Xu: Writing – review & editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was sponsored by the Key Project on Science and Technology Program of Fujian Health Commission (grant no. 2021ZD01002); Key Project on the Integration of Industry, Education and Research Collaborative Innovation of Fujian Province (grant no. 2021YZ034011); Joints Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (grant no. 2021Y9179).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Jiang, X. , Liang, B. , He, S. , Wu, X. , Zhao, W. , Xue, H. , Wang, Y. , Lin, N. , Huang, H. , & Xu, L. (2024). Prenatal diagnosis and genetic study of 22q11.2 microduplication in Chinese fetuses: A series of 31 cases and literature review. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 12, e2498. 10.1002/mgg3.2498

Contributor Information

Bin Liang, Email: fjmuliangbin@163.com.

Liangpu Xu, Email: xiliangpu@fjmu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Alfano, D. , Altomonte, A. , Cortes, C. , Bilio, M. , Kelly, R. G. , & Baldini, A. (2019). Tbx1 regulates extracellular matrix‐cell interactions in the second heart field. Human Molecular Genetics, 28(14), 2295–2308. 10.1093/hmg/ddz058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, L. E. , Hughes, S. S. , Tracy, M. , Feldt, M. M. , Zhang, L. , Arganbright, J. , & Kaye, A. (2022). 22q11.2 duplications: Expanding the clinical presentation. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A, 188(3), 779–787. 10.1002/ajmg.a.62577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann, L. , Pandita, R. K. , Spiteri, E. , Funke, B. , Goldberg, R. , Palanisamy, N. , Chaganti, R. S. , Magenis, E. , Shprintzen, R. J. , & Morrow, B. E. (1999). A common molecular basis for rearrangement disorders on chromosome 22q11. Human Molecular Genetics, 8(7), 1157–1167. 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, B. S. (2008). Molecular mechanisms and diagnosis of chromosome 22q11.2 rearrangements. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 14(1), 11–18. 10.1002/ddrr.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmuntz, E. (2020). 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and congenital heart disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics, 184(1), 64–72. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Han, X. , Ye, M. , Chen, S. , Shen, Y. , Niu, J. , Wang, Y. , & Xu, C. (2019). Prenatal diagnosis of microdeletions or microduplications in the proximal, central, and distal regions of chromosome 22q11.2: Ultrasound findings and pregnancy outcome. Frontiers in Genetics, 10, 813. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Jin, Y. , Yang, J. , Yang, L. , Tang, P. , Zhou, C. , Wu, L. , Dong, J. , Chen, J. , & Shen, H. (2020). Prenatal diagnosis of rearrangements in the fetal 22q11.2 region. Molecular Cytogenetics, 13, 28. 10.1186/s13039-020-00498-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez‐Rivera, E. , Liu, Y. P. , Verbitsky, M. , Anderson, B. R. , Capone, V. P. , Otto, E. A. , Yan, Z. , Mitrotti, A. , Martino, J. , Steers, N. J. , Fasel, D. A. , Vukojevic, K. , Deng, R. , Racedo, S. E. , Liu, Q. , Werth, M. , Westland, R. , Vivante, A. , Makar, G. S. , … Sanna‐Cherchi, S. (2017). Genetic drivers of kidney defects in the DiGeorge syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(8), 742–754. 10.1056/NEJMoa1609009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald‐McGinn, D. M. , Sullivan, K. E. , Marino, B. , Philip, N. , Swillen, A. , Vorstman, J. A. , Zackai, E. H. , Emanuel, B. S. , Vermeesch, J. R. , Morrow, B. E. , Scambler, P. J. , & Bassett, A. S. (2015). 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, 15071. 10.1038/nrdp.2015.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou, Z. , Berg, J. S. , Yonath, H. , Enciso, V. B. , Miller, D. T. , Picker, J. , Lenzi, T. , Keegan, C. E. , Sutton, V. R. , Belmont, J. , Chinault, A. C. , Lupski, J. R. , Cheung, S. W. , Roeder, E. , & Patel, A. (2008). Microduplications of 22q11.2 are frequently inherited and are associated with variable phenotypes. Genetics in Medicine, 10(4), 267–277. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b64c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinchefsky, E. , Laneuville, L. , & Srour, M. (2017). Distal 22q11.2 microduplication: Case report and review of the literature. Child Neurology Open, 4, 2329048X17737651. 10.1177/2329048X17737651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoï, M. F. (2009). Microduplication 22q11.2: A new chromosomal syndrome. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 52(2–3), 88–93. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, T. H. , Kurahashi, H. , Saitta, S. C. , O'Hare, A. M. , Hu, P. , Roe, B. A. , Driscoll, D. A. , McDonald‐McGinn, D. M. , Zackai, E. H. , Budarf, M. L. , & Emanuel, B. S. (2000). Chromosome 22‐specific low copy repeats and the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Genomic organization and deletion endpoint analysis. Human Molecular Genetics, 9(4), 489–501. 10.1093/hmg/9.4.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, T. H. , O'Connor, R. J. , Pierpont, M. E. , McGrath, J. , Hacker, A. M. , Nimmakayalu, M. , Geiger, E. , Emanuel, B. S. , & Saitta, S. C. (2007). Low copy repeats mediate distal chromosome 22q11.2 deletions: Sequence analysis predicts breakpoint mechanisms. Genome Research, 17(4), 482–491. 10.1101/gr.5986507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, C. , Fernström, M. , Ohrner, Y. , Annerén, G. , & Thuresson, A. C. (2008). Clinical variability of the 22q11.2 duplication syndrome. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 51(6), 501–510. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J. , Shen, R. , Xie, M. , Liu, Y. , Zhang, Y. , Gong, L. , & Li, H. (2021). 22q11.2 recurrent copy number variation‐related syndrome: A retrospective analysis of our own microarray cohort and a systematic clinical overview of ClinGen curation. Translational Pediatrics, 10(12), 3273–3281. 10.21037/tp-21-560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.