Abstract

Redox-inactive metal ions are essential in modulating the reactivity of various oxygen-containing metal complexes and metalloenzymes, including photosystem II (PSII). The heart of this unique membrane–protein complex comprises the Mn4CaO5 cluster, in which the Ca2+ ion acts as a critical cofactor in the splitting of water in PSII. However, there is still a lack of studies involving Ca-based reactive oxygen species (ROS) systems, and the exact nature of the interaction between the Ca2+ center and ROS in PSII still generates intense debate. Here, harnessing a novel Ca-TEMPO complex supported by the β-diketiminate ligand to control the activation of O2, we report the isolation and structural characterization of hitherto elusive Ca peroxides, a homometallic Ca hydroperoxide and a heterometallic Ca/K peroxide. Our studies indicate that the presence of K+ cations is a key factor controlling the outcome of the oxygenation reaction of the model Ca-TEMPO complex. Combining experimental observations with computational investigations, we also propose a mechanistic rationalization for the reaction outcomes. The designed approach demonstrates metal-TEMPO complexes as a versatile platform for O2 activation and advances the understanding of Ca/ROS systems.

Introduction

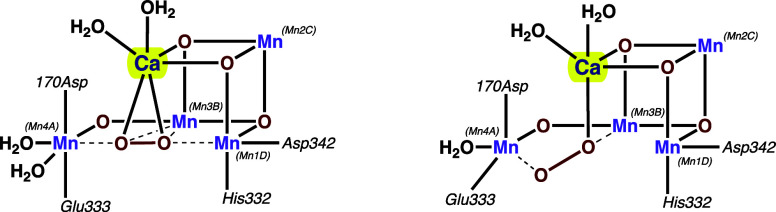

Redox-inactive metal ions, including Ca2+ cations, are essential in modulating the reactivity of various oxygen-containing metal complexes and metalloenzymes, e.g., the reactivity of transition metal-based reactive oxygen species (ROS)1−7 or water oxidation into dioxygen catalyzed by oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) in photosystem II (PSII).8−13 For example, the core of PSII consists of the Mn4CaO5 cluster,14−17 and decades of ongoing experimental and theoretical studies have focused on the factors controlling the chemistry of this unique CaMn4 assembly during splitting water to dioxygen in the catalytic Kok cycle.18−28 The mechanism of O–O bond formation in a short-living S4 state (Scheme 1) of the Kok cycle still generates an intense debate, and the reports that have been published so far suggest that the redox inactive Lewis-acidic Ca ion is essential for reactive intermediate stabilization, but its exact role is yet to be eluded.22,28−34 Undoubtedly, a detailed understanding of how the Ca2+ site facilitates O2 formation requires a clear picture of the interaction between the Ca2+ center and active oxygen species. Using synthetic structural models of the OEC is an efficient way to understand the processes driven by nature, and, generally, two approaches have been used to elucidate the role of Mn and Ca centers:35 (i) the modeling reactivity of predesigned heterometallic Mn/Ca clusters11,12,29,33,36−39 and (ii) various cuboidal MnxOy clusters.40−47 However, despite recent advances in modeling the OEC, there is still a lack of studies on Ca-based ROS systems. Herein, we report a unique reactivity of a model Ca-TEMPO (TEMPO = (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl) complex toward O2, leading to unprecedented Ca-hydroperoxide and heterometallic Ca/K peroxide species. The observed reactivity of Ca/ROS system relates to the postulated S4 transition state in the water splitting process, mediated by the heterometallic Mn4CaO5 cluster in the PSII system (Scheme 1).16,22,28 The isolation of Ca-centered ROS has hitherto eluded the skills of experimentalists, and thus, the presented studies might foster a broader discussion on the role of a Ca2+ site in the OEC.

Scheme 1. O2-Evolving S4 Transition State Models in OEC Proposed by Suga et al. (left)22 and Messinger and co-workers (right).28.

The activation of O2 by the model Ca-TEMPO complex tackles another fundamental issue of the dioxygen activation by various nature-driven systems, the understanding of which is essential in designing biomimetic processes aimed at sustainable development. Dioxygen is a fundamental molecule in life processes and a powerful oxidant in various biological systems involving metalloenzymes.48 To provide a more in-depth view of the O2 activation pathways, numerous transition metal-based synthetic biomimetic model systems have been developed in the last decades.49−55 Conversely, reaction systems based on redox-inactive metal complexes have been paid much less attention and have only started to gain momentum.56−61 For example, structural tracking of the O2 activation by main group organometallics and their organozinc relatives has emphasized the essential role of the Lewis acidity and coordination state of the oxygenated organometallic compounds.62,63 Moreover, systematic studies on the oxygenation of organometallics with redox inactive metal centers laid a foundation for a novel mechanism of the oxygenation process, i.e., the inner sphere electron transfer (ISET) mechanism, which strongly contradicted the textbook radical-chain mechanism.57,64,65 The ISET mechanism assumed that a critical step of the oxygenation reaction involves a single electron transfer (SET) from the M-C bond to the noncovalently activated O2 molecule (Scheme 2, left). Notably, with regard to the textbook radical chain mechanism, the radical character of the oxygenation process has usually been justified by the inhibition of the oxygenation reaction in the presence of nitroxyl radicals.66 However, recent studies demonstrated that the stable nitroxyl radicals smoothly react with organometallics and initiate the liberation of alkyl radicals.67 More importantly, reactions of nitroxyl radicals with organometallics likely involve a SET from the M–C bond to the coordinated nitroxyl radical and hence nicely resembles a key step in the novel ISET mechanism (Scheme 2, right).67,68

Scheme 2. Rationale of the Designed Reaction System for the Activation of O2.

Based on our vast expertise in the oxygenation of organometallics with redox-inactive metal centers56−58,65,64 and the multifaced chemistry of organometallic/TEMPO systems,67,69,70 we envisioned that the marriage of these two fertile landscapes might be a new vista for the O2 activation (Scheme 2). As proof of concept, we present the preparation and structural characterization of the first Ca complex incorporating a TEMPO anion and reveal its reactivity toward O2, leading to unique Ca-hydroperoxide and heterometallic Ca/K peroxide complexes. We also propose a mechanistic rationalization for the reaction outcomes based on combined experimental and theoretical investigations. Our synthetic approach demonstrates the simplicity and elegance of metal-TEMPO complex application in the O2 activation.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of the First Ca-TEMPO Complex

We selected the ubiquitous β-diketiminate ligand framework as a supporting scaffold due to its common successful use in the stabilization of various long-sought intermediates and highly reactive species,71−73 including a vital role in the isolation of elusive calcium complexes.74−84 Initially, a Ca chloride precursor [(dippBDI)CaCl(THF)]n (1) was prepared in situ by reacting equimolar amounts of CaCl2 with a K salt of a β-diketiminate ligand (HC{C(Me)N[C6H3iPr2-2,6]}2, abbreviated herein as dippBDI), in tetrahydrofuran (THF), according to the standard protocol. Next, the addition of a (TEMPO)K salt to the in situ prepared solution of 1 followed by the crystallization at 0 °C afforded the targeted complex [(dippBDI)CaTEMPO(THF)] (2) with essentially quantitative yield (Scheme 3). Compound 2 was fully characterized spectroscopically (Figures S1, S4–S6) and using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 1a). In the solid state, 2 exists as a monomer with a severely distorted tetrahedral geometry of a Ca center. The anionic TEMPO ligand coordinates the Ca center in a κ2(O,N)-mode, in contrast to the Mg analogue comprising the κ1(O)-coordinated TEMPO ligand.85 The Ca coordination environment is completed by a THF molecule.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Compounds 1–4.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of β-diketiminate supported Ca-TEMPO complex 2 (a), Ca hydroperoxide 32 (b), and Ca peroxide 4 (c). Hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity.

Synthesis of Ca Peroxide Complexes

Even though metal-TEMPO complexes have been utilized for different homogeneous oxidation reactions, owing to their unique capabilities for electron exchange,86,87 their controlled reversible reduction in the presence of O2 appears to be an unexplored area of research. We recall at this point that the ISET mechanism for the oxygenation of redox-inactive metal alkyls assumes that a SET from the M-C bond to an O2 molecule is crucial in this process.57 Given that the TEMPO anion readily undergoes 1e̅ oxidation, we wondered if the Ca-TEMPO complex 2 could act as an efficient system for the reductive activation of O2. We hypothesized that the SET from the Ca–OTEMPO bond to O2 with the concomitant evolution of a free TEMPO radical might be a source of Ca-supported reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Scheme 2). Thus, we investigated the reactivity of 2 toward O2. Slow diffusion of predried air in a hexane/THF solution of crystals of 2 for ca. 2 h at 4 °C led to a gradual reddish coloration of the solution, associated with the activation of O2 and the liberation of free TEMPO.85 Crystallization from the concentrated reaction mixture afforded a novel hydroperoxide [(dippBDI)Ca(μ-OOH)(THF)]2 (32) with moderate yield (Scheme 3); strikingly, the analogous reaction in a hexane/d8-THF solution led to a complicated reaction mixture, from which we were not able to isolate or spectroscopically identify the desired product (for a more detailed discussion, vide infra).

Conversely, a dramatically different outcome was observed during the oxygenation of in situ prepared complex 2 in THF. In that case, exposition of the mother liquor to dry air in a hexane/THF mixture for ca. 2 h followed by crystallization at −20 °C yielded a heterometallic Ca/K peroxide [(dippBDI)Ca(μ-OO)K(THF)]2 (4) with a moderate yield (Scheme 3). We would like to emphasize that calcium complexes with alkali metal countercation-specific stability are known;88−91 however, the presence of the potassium ion in 4 appears to be surprising at first glance. To this end, we performed an additional ICP-OES analysis of the filtered mother liquor of 2, revealing a Ca:K molar ratio of 2:1 (for more information, see Table S3). Thus, the presence of potassium cations in 4 might be reasonably explained by forming a contact ion pair between 2 and KCl in a solution; the respective 1H DOSY experiment was less sensitive and did not explain the nature of the postreaction mixture (Figure S7).

Structure Characterization

Compounds 32 and 4 were fully characterized spectroscopically (Figures S2–S6), and their identities were confirmed by the single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Compound 32 exists as a dimer with bridging hydroperoxide units between the Ca centers, which are flanked by dippBDI ligands and solvated by THF molecules (Figure 1b). There is a spread of Ca–O bond distances ranging from 2.342 to 2.383 Å (Table S6), and the O–O distances [1.340(4) and 1.348(5) Å] are within the typical range of distances recorded for hydroperoxide moieties and shorter than those observed for well-defined main group metal alkylperoxides.58,92 Compound 4 is a centrosymmetric dimer possessing two heptacoordinated Ca centers bridged by the peroxide moieties (Figure 1c). Both units in 4 are also seamed by two K+ cations interacting with the peroxide oxygen atoms and the flanked aromatic rings. The Ca–O bond distances fall in a narrow range (2.315–2.328 Å, Table S7), and the O–O bond distance (1.550(3) Å) is longer than that found in compound 32, and the observed differences in the O–O bond lengths likely result from the presence of a potassium ion in 4. DFT frequency calculations were also conducted to simulate the Raman spectra, thus allowing the O–O stretching vibrations of 32 and 4 at 825 and 790 cm–1, respectively, to be assigned (Figure S6). In the case of the Raman spectra of 4, the distinct signal likely corresponds to the vibrations of dippBDI ligands coordinated to K+ ions can also be distinguished (Figure S5). Moreover, the 1H NMR signal at 0.35 ppm attributable to the OO-H proton in 32 was visible (Figure S2).

We note that well-defined metal peroxides obtained from the controlled oxygenation of redox-inactive metal complexes are rather scarce, contrasting to the numerous reports on the isolation of transition metal peroxides. Up to now, only homometallic Mg,93 Zn,94,95 and Ga96 as well as heterometallic {[(Me3Si)2N]4M2Mg2(O2)} (M = K or Li)97 peroxides have been described. Undoubtedly, the isolation and structural authentication of the hitherto elusive homo- and heterometallic Ca peroxides fills the gap in the chemistry of main group metal peroxides and also provides the first model system for tracking ROS transformations in the presence of Ca ions. Moreover, unveiling the complexity of the interaction between Ca ions and ROS can contribute to a better understanding of the role of the Ca2+ site in the OEC, which remains one of the greatest enigmas within the protein-bound heterometallic Mn4CaO5 cluster in PSII.7,29−31

Mechanistic Considerations Supported by Quantum Chemical Calculations

The observed diversity in the reaction outcomes provides a vivid indication that the presence of K+ cations appears to be a key factor controlling the oxygenation chemistry of the Ca-TEMPO system. To understand the impact of the synthetic conditions on the transformations involving complex 2, we proposed the reaction pathways for the oxygenation of 2 as outlined in Scheme 4. In the case of the oxygenation of a pure solution of 2, the process is initiated by an attack of O2 on the Ca center followed by the ET from the Ca–OTEMPO bond to the O2 molecule. This stage nicely resembles the ISET mechanism (vide supra) as the HOMO orbital of 2 has a π*(O–N) character with a substantial contribution at the Ca atom (for details, see Table S8). As a result, a highly reactive Ca superoxide [(dippBDI)Ca(OO)(THF)] species is formed, which subsequently abstracts the hydrogen atom from a THF molecule. The resulting hydroperoxide [(dippBDI)Ca(OOH)(THF)] (3) moiety is stabilized by the formation of a dimer 32. The proposed hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the coordinated THF molecule may not be an obvious reaction pathway, but the observed retardation of this process in the presence of d8-THF (for dramatic kinetic isotope effect in the HAT process from THF and d8-THF, see Tolman et al.)98 with likely simultaneous shifting to side reactions along with our computational analysis (vide infra) supports this view. Moreover, in recent years, there has been a lively discussion on the HAT processes mediated by superoxide complexes with redox-active metal centers, and the number of well-documented examples is constantly growing.99−105

Scheme 4. Proposed Reaction Pathways of the Oxygenation of 2 Leading to 32 (path A) and 4 (path B).

For the Ca-TEMPO/K system, the presence of K+ ions in the reaction systems dramatically affects the reaction pathway. In this case, the first step of the oxygenation likely also involves the SET from the Ca–OTEMPO bond to the attacking O2 molecule with the formation of a Ca superoxide additionally stabilized by a K+ ion (Scheme 4, path B). The ion pair formation likely supports a SET from the second molecule of 2, forming a monomeric Ca peroxide and liberating free TEMPO. Finally, the subsequent association of the heterometallic peroxides leads to the formation of 4. Our suspicions of the hydrogen abstraction from THF were supported by GC–MS analysis of postreaction liquors. In the case of the oxidation of dissolved crystals of 2 in THF (cf. Scheme 4, path A), we found 2-hydroxytetrahydrofuran as a reaction product. In turn, the similar GC–MS measurements after the oxygenation of precrystallized THF solution of 2 (cf. Scheme 4, path B) do not reveal THF oxygenation products. We also kept in mind the well-documented noninnocence of β-diketiminate ligands,73,106 but the GC-MS experiments do not clearly indicate oxidation products of β-diketiminate units.

To substantiate the proposed mechanistic pathways and provide a rationalization of the experimental observation, we carried out a set of quantum chemical calculations. Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were carried out within the density functional theory (DFT) using BP86 functional107 augmented with the D3BJ dispersion correction108 using the def2-SVP basis set109 (TURBOMOLE 7.3).110 These calculations provided us with the zero-point energy (ZPE) correction. Single point energies were recomputed with the r2SCAN-3c composite method of Grimme et al.,111 along with the SMD implicit solvation model112 (THF) as implemented in the ORCA 5.0 program.113 Free K+ ions are represented as [K(THF)4]+, and coordination to any species considered is accompanied by a loss of one THF molecule ([K(THF)4]+ denoted as [K+]). Final reported energies are inclusive of ZPE correction.

In the parent complex 2, both the O and N atoms of the coordinated TEMPO display some sort of bonding toward the Ca center with Mayer’s bond order for the Ca–O and Ca–N bonds being 0.33 and 0.16, respectively (Figure 2a). The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is shared between the O and N atoms and has a π* character. The calculations also support the proposed reaction pathways of the oxygenation of 2. In the case of the reaction system without K+ ions, an interaction of O2 with the Ca center is accompanied by the ET from the HOMO orbital of 2 to O2 and followed by the formation of a superoxide transient species [2][O2·–] (Scheme 4, path A). The formation of [2][O2·–] is exothermic (−13.4 kcal/mol; reaction energies are listed in Table 1), and this transient complex features the end-on bound O2· moiety with the O–O bond length of 1.35 Å (Figure 2b). The results showed that the THF molecule in [2][O2·–] is coordinated in such a way that an H atom transfer to the superoxide moiety is greatly facilitated by a proximity effect and spatial orientation of the respective molecular orbitals (see Figure S12); here, the H atom of the THF is in the plane of the SOMO orbital of O2· so that the proximity effect is accounted for in the structure. Thus, complex [2][O2·–] abstracts a H atom from a THF molecule, which leads to a putative Ca hydroperoxide 3 (Scheme 4, path A); we note that the radical-mediated selective C–H functionalization of THF is a well-established process.68,114 In turn, the presence of K+ ions in the title reaction system significantly influences the oxygenation of 2. Based on the experimental observation, one may expect that K+ ions additionally stabilize the superoxide moiety. Indeed, the O2 binding in such case is more exothermic by about 18 kcal/mol (−24.3 kcal/mol for the formation of [2][K+][O2·–]) as compared to the system without K+ ions (see Figure 2b,c). Hypothetically, directed radical H-abstraction from the coordinated THF ligand for [2][K+][O2·–] with the formation of hydroperoxide is also feasible. The reaction barrier in this system is found to be 24.8 kcal/mol and is slightly reduced to that calculated for [2][O2·–] (27.9 kcal/mol). However, gripped by the observed reaction outcomes, we wondered what was the driving force behind the divergent oxygenation pathways of 2. Remarkably, we found that the presence of K+ ions significantly decreases the energy of the singly occupied molecular orbitals (SOMOs, see Figure 2b,c). Consequently, we anticipate that the [2][K+][O2·–] complex (eSOMO1 = −5.09 eV) will be a better electron acceptor than [2][O2·–] (eSOMO1 = −4.10 eV). The anticipated donor orbital for both reaction systems, HOMO of 2, is well aligned energetically (eHOMO = −4.00 eV, see Figure 2a) so that the expected driving force for SET to [2][K+][O2·–] is larger than for [2][O2·–].

Figure 2.

DFT-optimized structures of 2 (a). DFT-optimized structures of the products of reaction with molecular oxygen in the absence of K+ ions [2][O2·–] (b), and with K+ ions [2][K+][O2·–] (c), with the key interatomic distances marked in black. In panel (a), the selected Mayer bond orders are highlighted in green. For each structure, the isosurfaces (±0.03 au) of the selected frontier molecular orbitals are drawn along with associated energy (HOMO for closed-shell for 2 and QRO SOMOs for other two molecules in the triplet ground state).

Table 1. Reaction Energies in kcal/mol Computed at the r2SCAN-3c Level with SMD Solvation Model (THF) and ZPE Correction.

| reaction | ΔE |

|---|---|

| 2 + O2 → [2][O2·–] | –13.4 |

| [2][K+] + O2 → [2][K+][O2·–] | –24.3 |

| 2 + 2 → [2]2 | –5.6 |

| [2]2 + KCl(THF)4 → [2]2[KCl] + THF | –8.0 |

To further check if the ET process is favored in the case of [2][K+][O2·–] (consistent with Scheme 4, path B), we considered weakly interacting paramagnetic dimeric species [2a][O2·–][2] and [2a][O2·–][KCl][2], where [2a] is used to mark the moiety where free TEMPO was removed. In both systems, the SET process can occur from [2] to [O2·–]. To investigate the nature of the excited states in these systems with presumably charge transfer (CT) nature, we carried out high-level multireference calculations based on the complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF)115 method augmented with n-electron valence state perturbation theory treatment of the dynamic correlation (NEVPT2).116 We found that the S1excited states of [2a][O2·–][2] and [2a][O2·–][KCl][2] have the expected CT character and are located at 4.57 and 3.01 eV, respectively. In the Marcus theory picture, the decreased energy of the first CT state translates almost linearly to the increased driving force of the SET. Therefore, consistently with the one-electron picture (SOMO energies), the presence of KCl enhances the probability of electron transfer for [2][K+][O2·–], as compared to [2][O2·–], and opens an alternative route to the direct H-abstraction. Thus, the observed divergent outcomes of the oxygenation of 2 are dictated by the presence or absence of K+ ions in the reaction system.

Conclusions

In summary, we have recently witnessed a revival of interest in Ca chemistry. However, the activation of O2 by Ca complexes has not been the subject of thorough studies. The reported results demonstrate the multifaceted nature of metal-TEMPO complexes, which allows them to act as versatile platforms for O2 activation. Harnessing the β-diketiminate-supported Ca-TEMPO complex with O2, the successful synthesis of both the Ca hydroperoxide and the heterometallic Ca/K peroxide has been shown for the first time. The experimental results in tandem with theoretical studies broaden the state-of-the-art of interactions between redox-inactive metal complexes and O2,57,58 particularly the interplay of Ca2+ ions and ROS. The novel Ca peroxides also bear a resemblance to the postulated S4 transition state of the Kok catalytic cycle of water splitting and thus might foster a broader discussion on the role of a Ca2+ site in the bimetallic oxygen-evolving complex in PSII and support the design of biomimetic complexes for modeling of oxygen-evolving systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Warsaw University of Technology and the Institute of Physical Chemistry PAS for the generous support. We also acknowledge financial support from the National Science Centre, Poland, grant No. 2022/45/B/ST4/03863 and grant number 2018/30/E/ST4/00004 (A. Kubas). Access to high performance computing resources was provided by the Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and Computational Modelling in Warsaw, Poland, under grant GB79-5.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.4c00906.

Experimental details, synthesis and characterization information, spectroscopic data, crystal data, structure refinement parameters, and DFT calculations (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ A.K., T.P., and K.K. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Devi T.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W.; Fukuzumi S. Metal Ion-Coupled Electron-Transfer Reactions of Metal-Oxygen Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 410, 213219 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaralingam M.; Lee Y.-M.; Pineda-Galvan Y.; Karmalkar D. G.; Seo M. S.; Jeon S. H.; Pushkar Y.; Fukuzumi S.; Nam W. Redox Reactivity of a Mononuclear Manganese-Oxo Complex Binding Calcium Ion and Other Redox-Inactive Metal Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (3), 1324–1336. 10.1021/jacs.8b11492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargo N. P.; Harland J. B.; Musselman B. W.; Lehnert N.; Ertem M. Z.; Robinson J. R. Calcium-Ion Binding Mediates the Reversible Interconversion of Cis and Trans Peroxido Dicopper Cores. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (36), 19836–19842. 10.1002/anie.202105421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmeier A.; Dalle K. E.; D’Amore L.; Schulz R. A.; Dechert S.; Demeshko S.; Swart M.; Meyer F. Modulation of a μ-1,2-Peroxo Dicopper(II) Intermediate by Strong Interaction with Alkali Metal Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (42), 17751–17760. 10.1021/jacs.1c08645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.; Cho D.; Noh H.; Ohta T.; Baik M.-H.; Cho J. Controlled Regulation of the Nitrile Activation of a Peroxocobalt(III) Complex with Redox-Inactive Lewis Acidic Metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (30), 11382–11392. 10.1021/jacs.1c01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H.; Cheng L.; Pan Y.; Mak C.-K.; Lau K.-C.; Lau T.-C. Synergistic Effects of CH3CO2H and Ca2+ on C–H Bond Activation by MnO4–. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13 (39), 11600–11606. 10.1039/D2SC03089F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang S.; Lee Y.-M.; Hong S.; Cho K.-B.; Nishida Y.; Seo M. S.; Sarangi R.; Fukuzumi S.; Nam W. Redox-Inactive Metal Ions Modulate the Reactivity and Oxygen Release of Mononuclear Non-Haem Iron(III)–Peroxo Complexes. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6 (10), 934–940. 10.1038/nchem.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy J. P.; Brudvig G. W. Water-Splitting Chemistry of Photosystem II. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106 (11), 4455–4483. 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A. Missing Pieces in the Puzzle of Biological Water Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2018, 8 (10), 9477–9507. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz W.; Chrysina M.; Cox N. Water Oxidation in Photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 142 (1), 105–125. 10.1007/s11120-019-00648-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui E. Y.; Tran R.; Yano J.; Agapie T. Redox-Inactive Metals Modulate the Reduction Potential in Heterometallic Manganese–Oxido Clusters. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5 (4), 293–299. 10.1038/nchem.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui E. Y.; Agapie T. Reduction Potentials of Heterometallic Manganese–Oxido Cubane Complexes Modulated by Redox-Inactive Metals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (25), 10084–10088. 10.1073/pnas.1302677110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewald V.; Neese F.; Pantazis D. A. Redox Potential Tuning by Redox-Inactive Cations in Nature’s Water Oxidizing Catalyst and Synthetic Analogues. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18 (16), 10739–10750. 10.1039/C5CP07213A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umena Y.; Kawakami K.; Shen J.-R.; Kamiya N. Crystal Structure of Oxygen-Evolving Photosystem II at a Resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature 2011, 473 (7345), 55–60. 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.; Retegan M.; Neese F.; Pantazis D. A.; Boussac A.; Lubitz W. Electronic Structure of the Oxygen-Evolving Complex in Photosystem II Prior to O-O Bond Formation. Science 2014, 345 (6198), 804–808. 10.1126/science.1254910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M.; Akita F.; Hirata K.; Ueno G.; Murakami H.; Nakajima Y.; Shimizu T.; Yamashita K.; Yamamoto M.; Ago H.; Shen J.-R. Native Structure of Photosystem II at 1.95 Å Resolution Viewed by Femtosecond X-Ray Pulses. Nature 2015, 517 (7532), 99–103. 10.1038/nature13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young I. D.; Ibrahim M.; Chatterjee R.; Gul S.; Fuller F. D.; Koroidov S.; Brewster A. S.; Tran R.; Alonso-Mori R.; Kroll T.; Michels-Clark T.; Laksmono H.; Sierra R. G.; Stan C. A.; Hussein R.; Zhang M.; Douthit L.; Kubin M.; De Lichtenberg C.; Vo Pham L.; Nilsson H.; Cheah M. H.; Shevela D.; Saracini C.; Bean M. A.; Seuffert I.; Sokaras D.; Weng T.-C.; Pastor E.; Weninger C.; Fransson T.; Lassalle L.; Bräuer P.; Aller P.; Docker P. T.; Andi B.; Orville A. M.; Glownia J. M.; Nelson S.; Sikorski M.; Zhu D.; Hunter M. S.; Lane T. J.; Aquila A.; Koglin J. E.; Robinson J.; Liang M.; Boutet S.; Lyubimov A. Y.; Uervirojnangkoorn M.; Moriarty N. W.; Liebschner D.; Afonine P. V.; Waterman D. G.; Evans G.; Wernet P.; Dobbek H.; Weis W. I.; Brunger A. T.; Zwart P. H.; Adams P. D.; Zouni A.; Messinger J.; Bergmann U.; Sauter N. K.; Kern J.; Yachandra V. K.; Yano J. Structure of Photosystem II and Substrate Binding at Room Temperature. Nature 2016, 540 (7633), 453–457. 10.1038/nature20161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B.; Forbush B.; McGloin M. Cooperation of Charges in Photosynthetic O2 Evolution–I. A Linear Four Step Mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 1970, 11 (6), 457–475. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M.; Akita F.; Sugahara M.; Kubo M.; Nakajima Y.; Nakane T.; Yamashita K.; Umena Y.; Nakabayashi M.; Yamane T.; Nakano T.; Suzuki M.; Masuda T.; Inoue S.; Kimura T.; Nomura T.; Yonekura S.; Yu L.-J.; Sakamoto T.; Motomura T.; Chen J.-H.; Kato Y.; Noguchi T.; Tono K.; Joti Y.; Kameshima T.; Hatsui T.; Nango E.; Tanaka R.; Naitow H.; Matsuura Y.; Yamashita A.; Yamamoto M.; Nureki O.; Yabashi M.; Ishikawa T.; Iwata S.; Shen J.-R. Light-Induced Structural Changes and the Site of O=O Bond Formation in PSII Caught by XFEL. Nature 2017, 543 (7643), 131–135. 10.1038/nature21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmiller T.; Krewald V.; Sedoud A.; Rutherford A. W.; Neese F.; Lubitz W.; Pantazis D. A.; Cox N. The First State in the Catalytic Cycle of the Water-Oxidizing Enzyme: Identification of a Water-Derived μ-Hydroxo Bridge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (41), 14412. 10.1021/jacs.7b05263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern J.; Chatterjee R.; Young I. D.; Fuller F. D.; Lassalle L.; Ibrahim M.; Gul S.; Fransson T.; Brewster A. S.; Alonso-Mori R.; Hussein R.; Zhang M.; Douthit L.; de Lichtenberg C.; Cheah M. H.; Shevela D.; Wersig J.; Seuffert I.; Sokaras D.; Pastor E.; Weninger C.; Kroll T.; Sierra R. G.; Aller P.; Butryn A.; Orville A. M.; Liang M.; Batyuk A.; Koglin J. E.; Carbajo S.; Boutet S.; Moriarty N. W.; Holton J. M.; Dobbek H.; Adams P. D.; Bergmann U.; Sauter N. K.; Zouni A.; Messinger J.; Yano J.; Yachandra V. K. Structures of the Intermediates of Kok’s Photosynthetic Water Oxidation Clock. Nature 2018, 563 (7731), 421–425. 10.1038/s41586-018-0681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M.; Akita F.; Yamashita K.; Nakajima Y.; Ueno G.; Li H.; Yamane T.; Hirata K.; Umena Y.; Yonekura S.; Yu L.-J.; Murakami H.; Nomura T.; Kimura T.; Kubo M.; Baba S.; Kumasaka T.; Tono K.; Yabashi M.; Isobe H.; Yamaguchi K.; Yamamoto M.; Ago H.; Shen J.-R. An Oxyl/Oxo Mechanism for Oxygen-Oxygen Coupling in PSII Revealed by an X-Ray Free-Electron Laser. Science 2019, 366 (6463), 334–338. 10.1126/science.aax6998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry T. A.; O’Malley P. J. Molecular Identification of a High-Spin Deprotonated Intermediate during the S2 to S3 Transition of Nature’s Water-Oxidizing Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (23), 10240–10243. 10.1021/jacs.0c01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahariou G.; Ioannidis N.; Sanakis Y.; Pantazis D. A. Arrested Substrate Binding Resolves Catalytic Intermediates in Higher-Plant Water Oxidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (6), 3156–3162. 10.1002/anie.202012304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosou M.; Pantazis D. A. Redox Isomerism in the S3 State of the Oxygen-Evolving Complex Resolved by Coupled Cluster Theory. Chem. - Eur. J. 2021, 27 (50), 12815–12825. 10.1002/chem.202101567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick A.; Hussein R.; Bogacz I.; Simon P. S.; Ibrahim M.; Chatterjee R.; Doyle M. D.; Cheah M. H.; Fransson T.; Chernev P.; Kim I.-S.; Makita H.; Dasgupta M.; Kaminsky C. J.; Zhang M.; Gätcke J.; Haupt S.; Nangca I. I.; Keable S. M.; Aydin A. O.; Tono K.; Owada S.; Gee L. B.; Fuller F. D.; Batyuk A.; Alonso-Mori R.; Holton J. M.; Paley D. W.; Moriarty N. W.; Mamedov F.; Adams P. D.; Brewster A. S.; Dobbek H.; Sauter N. K.; Bergmann U.; Zouni A.; Messinger J.; Kern J.; Yano J.; Yachandra V. K. Structural Evidence for Intermediates during O2 Formation in Photosystem II. Nature 2023, 617 (7961), 629–636. 10.1038/s41586-023-06038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greife P.; Schönborn M.; Capone M.; Assunção R.; Narzi D.; Guidoni L.; Dau H. The Electron–Proton Bottleneck of Photosynthetic Oxygen Evolution. Nature 2023, 617 (7961), 623–628. 10.1038/s41586-023-06008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Messinger J.; Kloo L.; Sun L. Alternative Mechanism for O2 Formation in Natural Photosynthesis via Nucleophilic Oxo–Oxo Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (7), 4129–4141. 10.1021/jacs.2c12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanady J. S.; Tsui E. Y.; Day M. W.; Agapie T. A Synthetic Model of the Mn3Ca Subsite of the Oxygen-Evolving Complex in Photosystem II. Science 2011, 333 (6043), 733–736. 10.1126/science.1206036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti D.; Agapie T. How Calcium Affects Oxygen Formation. Nature 2014, 513 (7519), 495–496. 10.1038/nature13753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauthe S.; Fleischer I.; Bernhardt T. M.; Lang S. M.; Barnett R. N.; Landman U. A Gas-Phase CanMn4–nO4+ Cluster Model for the Oxygen-Evolving Complex of Photosystem II. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (25), 8504–8509. 10.1002/anie.201903738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avramov A. P.; Hwang H. J.; Burnap R. L. The Role of Ca2+ and Protein Scaffolding in the Formation of Nature’s Water Oxidizing Complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (45), 28036–28045. 10.1073/pnas.2011315117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R.; Li Y.; Chen Y.; Xu B.; Chen C.; Zhang C. Rare-Earth Elements Can Structurally and Energetically Replace the Calcium in a Synthetic Mn4CaO4-Cluster Mimicking the Oxygen-Evolving Center in Photosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (42), 17360–17365. 10.1021/jacs.1c09085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K.; Miyagawa K.; Shoji M.; Isobe H.; Kawakami T. Elucidation of a Multiple S3 Intermediates Model for Water Oxidation in the Oxygen Evolving Complex of Photosystem II. Calcium-Assisted Concerted O-O Bond Formation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 806, 140042 10.1016/j.cplett.2022.140042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S.; Neese F.; Pantazis D. A. Structural Models of the Biological Oxygen-Evolving Complex: Achievements, Insights, and Challenges for Biomimicry. Green Chem. 2017, 19 (10), 2309–2325. 10.1039/C7GC00425G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanady J. S.; Lin P.-H.; Carsch K. M.; Nielsen R. J.; Takase M. K.; Goddard W. A.; Agapie T. Toward Models for the Full Oxygen-Evolving Complex of Photosystem II by Ligand Coordination To Lower the Symmetry of the Mn3CaO4 Cubane: Demonstration That Electronic Effects Facilitate Binding of a Fifth Metal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (41), 14373–14376. 10.1021/ja508160x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Chen C.; Dong H.; Shen J.-R.; Dau H.; Zhao J. A Synthetic Mn 4 Ca-Cluster Mimicking the Oxygen-Evolving Center of Photosynthesis. Science 2015, 348 (6235), 690–693. 10.1126/science.aaa6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. B.; Shiau A. A.; Marchiori D. A.; Oyala P. H.; Yoo B.; Kaiser J. T.; Rees D. C.; Britt R. D.; Agapie T. CaMn3IVO4 Cubane Models of the Oxygen-Evolving Complex: Spin Ground States S < 9/2 and the Effect of Oxo Protonation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (32), 17671–17679. 10.1002/anie.202105303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau A. A.; Lee H. B.; Oyala P. H.; Agapie T. Coordination Number in High-Spin–Low-Spin Equilibrium in Cluster Models of the S2 State of the Oxygen Evolving Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (27), 14592–14598. 10.1021/jacs.3c04464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruettinger W. F.; Campana C.; Dismukes G. C. Synthesis and Characterization of Mn4O4L6 Complexes with Cubane-like Core Structure: A New Class of Models of the Active Site of the Photosynthetic Water Oxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119 (28), 6670–6671. 10.1021/ja9639022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brimblecombe R.; Swiegers G. F.; Dismukes G. C.; Spiccia L. Sustained Water Oxidation Photocatalysis by a Bioinspired Manganese Cluster. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47 (38), 7335–7338. 10.1002/anie.200801132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimblecombe R.; Koo A.; Dismukes G. C.; Swiegers G. F.; Spiccia L. Solar Driven Water Oxidation by a Bioinspired Manganese Molecular Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (9), 2892–2894. 10.1021/ja910055a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Oweini R.; Sartorel A.; Bassil B. S.; Natali M.; Berardi S.; Scandola F.; Kortz U.; Bonchio M. Photocatalytic Water Oxidation by a Mixed-Valent MnIII3MnIVO3 Manganese Oxo Core That Mimics the Natural Oxygen-Evolving Center. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (42), 11182–11185. 10.1002/anie.201404664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz B.; Forster J.; Goetz M. K.; Yücel D.; Berger C.; Jacob T.; Streb C. Visible-Light-Driven Water Oxidation by a Molecular Manganese Vanadium Oxide Cluster. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (21), 6329–6333. 10.1002/anie.201601799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maayan G.; Gluz N.; Christou G. A Bioinspired Soluble Manganese Cluster as a Water Oxidation Electrocatalyst with Low Overpotential. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1 (1), 48–54. 10.1038/s41929-017-0004-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z.; Horak K. T.; Lee H. B.; Agapie T. Tetranuclear Manganese Models of the OEC Displaying Hydrogen Bonding Interactions: Application to Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation to Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (27), 9108–9111. 10.1021/jacs.7b03044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. B.; Shiau A. A.; Oyala P. H.; Marchiori D. A.; Gul S.; Chatterjee R.; Yano J.; Britt R. D.; Agapie T. Tetranuclear [MnIIIMn3IVO4] Complexes as Spectroscopic Models of the S2 State of the Oxygen Evolving Complex in Photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (49), 17175–17187. 10.1021/jacs.8b09961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam W. Dioxygen Activation by Metalloenzymes and Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40 (7), 465–465. 10.1021/ar700131d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Que L.; Tolman W. B. Biologically Inspired Oxidation Catalysis. Nature 2008, 455 (7211), 333–340. 10.1038/nature07371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nastri F.; Chino M.; Maglio O.; Bhagi-Damodaran A.; Lu Y.; Lombardi A. Design and Engineering of Artificial Oxygen-Activating Metalloenzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45 (18), 5020–5054. 10.1039/C5CS00923E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S.; Goldberg D. P. Activation of Dioxygen by Iron and Manganese Complexes: A Heme and Nonheme Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (36), 11410–11428. 10.1021/jacs.6b05251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasniewski A. J.; Que L. Dioxygen Activation by Nonheme Diiron Enzymes: Diverse Dioxygen Adducts, High-Valent Intermediates, and Related Model Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118 (5), 2554–2592. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M.; Corona T.; Ray K.; Nam W. Heme and Nonheme High-Valent Iron and Manganese Oxo Cores in Biological and Abiological Oxidation Reactions. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5 (1), 13–28. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistella B.; Ray K. O2 and H2O2 Activations at Dinuclear Mn and Fe Active Sites. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 408, 213176 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-P.; Chandra A.; Lee Y.-M.; Cao R.; Ray K.; Nam W. Transition Metal-Mediated O–O Bond Formation and Activation in Chemistry and Biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50 (8), 4804–4811. 10.1039/D0CS01456G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewiński J.; Marciniak W.; Lipkowski J.; Justyniak I. New Insights into the Reaction of Zinc Alkyls with Dioxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (1), 12698–12699. 10.1021/ja036020t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewiński J.; Śliwiński W.; Dranka M.; Justyniak I.; Lipkowski J. Reactions of [ZnR2(L)] Complexes with Dioxygen: A New Look at an Old Problem. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45 (3), 4826–4829. 10.1002/anie.200601001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak T.; Justyniak I.; Kubisiak M.; Bojarski E.; Lewiński J. An In-Depth Look at the Reactivity of Non-Redox-Metal Alkylperoxides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (25), 8526–8530. 10.1002/anie.201904380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S.; Berger R. J. F.; Fröhlich R.; Pape T.; Mitzel N. W. Oxygenation of Simple Zinc Alkyls: Surprising Dependence of Product Distributions on the Alkyl Substituents and the Presence of Water. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46 (10), 4293–4297. 10.1021/ic062438r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth N.; Johnson A. L.; Kingsley A.; Kociok-Köhn G.; Molloy K. C. Structural Study of the Reaction of Methylzinc Amino Alcoholates with Oxygen. Organometallics 2010, 29 (15), 3318–3326. 10.1021/om100449t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. L.; Hollingsworth N.; Kociok-Köhn G.; Molloy K. C.; Kociok-Köhn G.; Molloy K. C. O2 Insertion into a Cadmium-Carbon Bond: Structural Characterization of Organocadmium Peroxides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51 (17), 4108–4111. 10.1002/anie.201200448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewiński J.; Zachara J.; Goś P.; Grabska E.; Kopeć T.; Madura I.; Marciniak W.; Protworow I. Reactivity of Various Four-Coordinate Aluminum Alkyls towards Dioxygen: Evidence for Spatial Requirements in the Insertion of an Oxygen Molecule into the AI-C Bond. Chem.—Eur. J. 2000, 6 (17), 3215–3217. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak T.; Justyniak I.; Park J. V.; Terlecki M.; Kapuśniak Ł.; Lewiński J. Reaching Milestones in the Oxygenation Chemistry of Magnesium Alkyls: Towards Intimate States of O2 Activation and the First Monomeric Well-Defined Magnesium Alkylperoxide. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25 (10), 2503–2510. 10.1002/chem.201805180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak T.; Kubisiak M.; Justyniak I.; Zelga K.; Bojarski E.; Tratkiewicz E.; Ochal Z.; Lewiński J. Oxygenation Chemistry of Magnesium Alkyls Incorporating β-Diketiminate Ligands Revisited. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22 (49), 17776–17783. 10.1002/chem.201603931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak T.; Korzyński M. D.; Justyniak I.; Zelga K.; Kornowicz A.; Ochal Z.; Lewiński J. Unprecedented Variety of Outcomes in the Oxygenation of Dinuclear Alkylzinc Derivatives of an N,N-Coupled Bis(β-Diketimine). Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (33), 7997–8005. 10.1002/chem.201700503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury J.; Feray L.; Bazin S.; Clément J. L.; Marque S. R. A.; Siri D.; Bertrand M. P. Spin-Trapping Evidence for the Formation of Alkyl, Alkoxyl, and Alkylperoxyl Radicals in the Reactions of Dialkylzincs with Oxygen. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17 (5), 1586–1595. 10.1002/chem.201002616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budny-Godlewski K.; Kubicki D.; Justyniak I.; Lewiński J. A New Look at the Reactivity of TEMPO toward Diethylzinc. Organometallics 2014, 33 (19), 5093–5096. 10.1021/om5008117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubisiak M.; Zelga K.; Bury W.; Justyniak I.; Budny-Godlewski K.; Ochal Z.; Lewiński J. Development of Zinc Alkyl/Air Systems as Radical Initiators for Organic Reactions. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6 (5), 3102–3108. 10.1039/C5SC00600G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budny-Godlewski K.; Justyniak I.; Leszczyński M. K.; Lewiński J. Mechanochemical and Slow-Chemistry Radical Transformations: A Case of Diorganozinc Compounds and TEMPO. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (30), 7149–7155. 10.1039/C9SC01396B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Budny-Godlewski K.; Leszczyński M. K.; Tulewicz A.; Justyniak I.; Pinkowicz D.; Sieklucka B.; Kruczała K.; Sojka Z.; Lewiński J. A Case Study on the Desired Selectivity in Solid-State Mechano- and Slow-Chemistry, Melt, and Solution Methodologies. ChemSusChem 2021, 14 (18), 3887–3894. 10.1002/cssc.202101269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Budny-Godlewski K.; Piekarski D. G.; Justyniak I.; Leszczyński M. K.; Nawrocki J.; Kubas A.; Lewiński J. Uncovering Factors Controlling Reactivity of Metal-TEMPO Reaction Systems in the Solid State and Solution. Chem. - Eur. J. 2024, 10.1002/chem.202401968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourget-Merle L.; Lappert M. F.; Severn J. R. The Chemistry of β-Diketiminatometal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102 (9), 3031–3066. 10.1021/cr010424r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y.-C. The Chemistry of Univalent Metal β-Diketiminates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256 (5–8), 722–758. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camp C.; Arnold J. On the Non-Innocence of “Nacnacs”: Ligand-Based Reactivity in β-Diketiminate Supported Coordination Compounds. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45 (37), 14462–14498. 10.1039/C6DT02013E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruspic C.; Nembenna S.; Hofmeister A.; Magull J.; Harder S.; Roesky H. W. A Well-Defined Hydrocarbon-Soluble Calcium Hydroxide: Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (46), 15000–15004. 10.1021/ja065631t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder S. From Limestone to Catalysis: Application of Calcium Compounds as Homogeneous Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110 (7), 3852–3876. 10.1021/cr9003659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker M. D.; Kefalidis C. E.; Yang Y.; Fang J.; Hill M. S.; Mahon M. F.; Maron L. Alkaline Earth-Centered CO Homologation, Reduction, and Amine Carbonylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (29), 10036–10054. 10.1021/jacs.7b04926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. S. S.; Hill M. S.; Mahon M. F.; Dinoi C.; Maron L. Organocalcium-Mediated Nucleophilic Alkylation of Benzene. Science 2017, 358 (6367), 1168–1171. 10.1126/science.aao5923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S.; Elsen H.; Langer J.; Donaubauer W. A.; Hampel F.; Harder S. Facile Benzene Reduction by a Ca2+/AlI Lewis Acid/Base Combination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (43), 14169–14173. 10.1002/anie.201809236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamm R. J.; Coles M. P.; Hill M. S.; Mahon M. F.; McMullin C. L.; Rajabi N. A.; Wilson A. S. S. A Stable Calcium Alumanyl. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (10), 3928–3932. 10.1002/anie.201914986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. S. S.; Dinoi C.; Hill M. S.; Mahon M. F.; Maron L.; Richards E. Calcium Hydride Reduction of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (3), 1232–1237. 10.1002/anie.201913895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rösch B.; Gentner T. X.; Langer J.; Färber C.; Eyselein J.; Zhao L.; Ding C.; Frenking G.; Harder S. Dinitrogen Complexation and Reduction at Low-Valent Calcium. Science 2021, 371 (6534), 1125–1128. 10.1126/science.abf2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce K. G.; Dinoi C.; Hill M. S.; Mahon M. F.; Maron L.; Schwamm R. S.; Wilson A. S. S. Synthesis of Molecular Phenylcalcium Derivatives: Application to the Formation of Biaryls. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61 (18), e202200305 10.1002/anie.202200305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder S.; Langer J. Opportunities with Calcium Grignard Reagents and Other Heavy Alkaline-Earth Organometallics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7 (12), 843–853. 10.1038/s41570-023-00548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai J.; Morasch M.; Jędrzkiewicz D.; Langer J.; Rösch B.; Harder S. Alkaline-Earth Metal Mediated Benzene-to-Biphenyl Coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (3), e202212463 10.1002/anie.202212463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptrot D. J.; Hill P. M. S.; Mahon M. F. Accessing the Single-Electron Manifold: Magnesium-Mediated Hydrogen Release from Silanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (24), 6224–6227. 10.1002/anie.201403208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes G. C.; Kennedy A. R.; Mulvey R. E.; Rodger P. J. A. TEMPO: A Novel Chameleonic Ligand for s-Block Metal Amide Chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1 (15), 1400–1401. 10.1039/b104937m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balloch L.; Drummond A. M.; García-Álvarez P.; Graham D. V.; Kennedy A. R.; Klett J.; Mulvey R. E.; O’Hara C. T.; Rodger P. J. A.; Rushworth I. D. Structural Variations within Group 1 (Li–Cs)+(2,2,6,6-Tetramethyl-1-Piperidinyloxy)− Complexes Made via Metallic Reduction of the Nitroxyl Radical. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48 (14), 6934–6944. 10.1021/ic900609e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns A. M.; Chmely S. C.; Hanusa T. P. Solution Interaction of Potassium and Calcium Bis(Trimethylsilyl)Amides; Preparation of Ca[N(SiMe3)2]2 from Dibenzylcalcium. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48 (4), 1380–1384. 10.1021/ic8012766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhausen M.; Koch A.; Görls H.; Krieck S. Heavy Grignard Reagents: Synthesis, Physical and Structural Properties, Chemical Behavior, and Reactivity. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (7), 1456–1483. 10.1002/chem.201603786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal R.; Yuvaraj K.; Rajeshkumar T.; Maron L.; Jones C. Reductive Activation of N2 Using a Calcium/Potassium Bimetallic System Supported by an Extremely Bulky Diamide Ligand. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (91), 12665–12668. 10.1039/D2CC04841H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai J.; Maurer J.; Langer J.; Harder S. Heterobimetallic Alkaline Earth Metal–Metal Bonding. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3 (3), 368–377. 10.1038/s44160-023-00451-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak T.; Justyniak I.; Zelga K.; Nowak K.; Ochal Z.; Lewiński J. Towards Deeper Understanding of Multifaceted Chemistry of Magnesium Alkylperoxides. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4 (1), 123. 10.1038/s42004-021-00560-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalrempuia R.; Stasch A.; Jones C. The Reductive Disproportionation of CO2 Using a Magnesium(I) Complex: Analogies with Low Valent f-Block Chemistry. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4 (12), 4383. 10.1039/c3sc52242c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl E. W.; Kiernicki J. J.; Zeller M.; Szymczak N. K. Hydrogen Bonds Dictate O2 Capture and Release within a Zinc Tripod. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (32), 10075–10079. 10.1021/jacs.8b04266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mąkolski Ł.; Zelga K.; Petrus R.; Kubicki D.; Zarzycki P.; Sobota P.; Lewiński J. Probing the Role of π Interactions in the Reactivity of Oxygen Species: A Case of Ethylzinc Aryloxides with Different Dispositions of Aromatic Rings toward the Metal Center. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20 (45), 14790–14799. 10.1002/chem.201403851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl W.; Melle S.; Prött M. 1,4-Di(Isopropyl)-1,4-Diazabutadien Als Abfangreagenz Für Monomere Bruchstücke Des Tetragalliumclusters Ga4[C(SiMe3)3]4 - Bildung Eines Ungesättigten GaN2C2-Heterocyclus Und Eines Oxidationsprodukts Mit Ga-O-O-Ga-Gruppe. Z. Für Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2005, 631 (8), 1377–1382. 10.1002/zaac.200400536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A. R.; Mulvey R. E.; Rowlings R. B. Remarkable Reaction of Hetero-S-Block-Metal Amides with Molecular Oxygen: Cationic (NMNMg)2 Ring Products (M = Li or Na) with Anionic Oxo or Peroxo Cores. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37 (22), 3180–3183. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar D.; Tolman W. B. Hydrogen Atom Abstraction from Hydrocarbons by a Copper(III)-Hydroxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (3), 1322–1329. 10.1021/ja512014z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer J.; Peck K. L.; Schmitt J. C.; Neupane K. P. Cysteinate Protonation and Water Hydrogen Bonding at the Active-Site of a Nickel Superoxide Dismutase Metallopeptide-Based Mimic: Implications for the Mechanism of Superoxide Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (45), 16009–16022. 10.1021/ja5079514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirovano P.; Magherusan A. M.; McGlynn C.; Ure A.; Lynes A.; McDonald A. R. Nucleophilic Reactivity of a Copper(II)–Superoxide Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (23), 5946–5950. 10.1002/anie.201311152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcos A. R.; Villanueva O.; Walroth R. C.; Sharma S. K.; Bacsa J.; Lancaster K. M.; MacBeth C. E.; Berry J. F. Oxygen Activation by Co(II) and a Redox Non-Innocent Ligand: Spectroscopic Characterization of a Radical–Co(II)–Superoxide Complex with Divergent Catalytic Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (6), 1796–1799. 10.1021/jacs.5b12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey W. D.; Dhar D.; Cramblitt A. C.; Tolman W. B. Mechanistic Dichotomy in Proton-Coupled Electron-Transfer Reactions of Phenols with a Copper Superoxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (13), 5470–5480. 10.1021/jacs.9b00466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Rogler P. J.; Sharma S. K.; Schaefer A. W.; Solomon E. I.; Karlin K. D. Heme-FeIII Superoxide, Peroxide and Hydroperoxide Thermodynamic Relationships: FeIII-O2•– Complex H-Atom Abstraction Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (6), 3104–3116. 10.1021/jacs.9b12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.-C.; Jiang Y.; Lin Y.-H.; Zhang P.; Wang C.-C.; Ye S.; Lee W.-Z. Hydrogen Atom Transfer Thermodynamics of Homologous Co(III)- and Mn(III)-Superoxo Complexes: The Effect of the Metal Spin State. JACS Au 2022, 2 (8), 1899–1909. 10.1021/jacsau.2c00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gering H. E.; Li X.; Tang H.; Swartz P. D.; Chang W.-C.; Makris T. M. A Ferric-Superoxide Intermediate Initiates P450-Catalyzed Cyclic Dipeptide Dimerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (35), 19256–19264. 10.1021/jacs.3c04542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khusniyarov M. M.; Bill E.; Weyhermüller T.; Bothe E.; Wieghardt K. Hidden Noninnocence: Theoretical and Experimental Evidence for Redox Activity of a β-Diketiminate(1−) Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50 (7), 1652–1655. 10.1002/anie.201005953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-Functional Exchange-Energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38 (6), 3098–3100. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132 (15), 154104 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7 (18), 3297. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TURBOMOLE v.7.6 (University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, 1989–2007).

- Grimme S.; Hansen A.; Ehlert S.; Mewes J.-M. R2SCAN-3c: A “Swiss Army Knife” Composite Electronic-Structure Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154 (6), 064103 10.1063/5.0040021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113 (18), 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12 (5), e1606 10.1002/wcms.1606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.-Y.; Zhang F.-M.; Tu Y.-Q. Direct Sp3 α-C–H Activation and Functionalization of Alcohol and Ether. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40 (4), 1937. 10.1039/c0cs00063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos B. O.; Taylor P. R.; Sigbahn P. E. M. A Complete Active Space SCF Method (CASSCF) Using a Density Matrix Formulated Super-CI Approach. Chem. Phys. 1980, 48 (2), 157–173. 10.1016/0301-0104(80)80045-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angeli C.; Cimiraglia R.; Evangelisti S.; Leininger T.; Malrieu J.-P. Introduction of n-Electron Valence States for Multireference Perturbation Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114 (23), 10252–10264. 10.1063/1.1361246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.