Abstract

The marketing of heated tobacco products (HTPs), like IQOS, influences consumers’ perceptions. This mixed-methods study analyzed (i) survey data (2021) of 2222 US and Israeli adults comparing perceptions of 7 IQOS attributes (design, technology, colors, customization, flavors, cost and maintenance) and 10 marketing messages (e.g. ‘Go smoke-free…’) across tobacco use subgroups and (ii) qualitative interviews (n = 84) regarding IQOS perceptions. In initial bivariate analyses, those never using HTPs (86.2%) reported the least overall appeal; those currently using HTPs (7.7%) reported the greatest appeal. Notably, almost all (94.8%) currently using HTPs also currently used cigarettes (82.0%) and/or e-cigarettes (64.0%). Thus, multivariable linear regression accounted for current cigarette/e-cigarette use subgroup and HTP use separately; compared to neither cigarette/e-cigarette use (62.8%), cigarette/no e-cigarette use (17.1%) and e-cigarette/no cigarette use (6.5%), those with dual use (13.5%) indicated greater overall IQOS appeal (per composite index score); current HTP use was not associated. Qualitative data indicated varied perceptions regarding advantages (e.g. harm, addiction and complexity) of IQOS versus cigarettes and e-cigarettes, and perceived target markets included young people, those looking for cigarette alternatives and females. Given the perceived target markets and particular appeal to dual cigarette/e-cigarette use groups, IQOS marketing and population impact warrant ongoing monitoring to inform regulation.

Introduction

The global tobacco market has expanded to include new products like heated tobacco products (HTPs) [1, 2]. Philip Morris International’s (PMI’s) IQOS, the global HTP leader [2], has unique histories in Israel and the United States. In Israel, IQOS was introduced without regulation in 2016 and then faced weak regulation from 2017 to 2018 when classified as a tobacco product. In 2019–20, Israel passed progressive tobacco control legislation, including advertising restrictions (2019) and plain packaging requirements (2020) that applied to IQOS [3]. In the United States, IQOS was launched in 2019 [4, 5] and received authorization from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020 to use advertising messages regarding reduced exposure to harmful chemicals, but ‘not’ claims that it is safer or less harmful than other tobacco [6]. IQOS sales ceased in the United States in November 2021 due to a patent-infringement lawsuit [7] but are expected to resume in 2024 [8, 9]. Perhaps due to IQOS’ longstanding history in Israel, 2021 estimates indicated that 16% of Israeli adults had ever used IQOS, with 8% currently using [10], while 3% of US adults had ever used IQOS, with 1% currently using [10].

HTP-related consumer behavior may be influenced by marketing elements like product design, distribution and promotion [10, 11]. Regarding product design and distribution, IQOS is available in different colors and designs, allowing consumers to personalize the device [3], and the devices, heatsticks and accessories (e.g. cleaning sticks) are available via select traditional retailers (e.g. convenience stores), IQOS specialty stores and online [3].

IQOS uses aggressive promotional activities (e.g. social events, membership programs, price promotions, point-of-sale displays, and online promotion via social media) [9, 12–18]. Advertising messages often indicate reduced risk [3, 18, 19], which may appeal to [20–25] and/or mislead consumers [21, 26–31]. For example, consumers misperceive FDA-authorized statements regarding ‘reduced exposure’ claims to mean lower risk [21, 26–30] and may even misinterpret smoking health warnings as endorsements for IQOS [27, 31]. Other advertising messages emphasize IQOS as a clean, chic and pure product, more acceptable to non-smokers, and a satisfactory alternative to cigarettes (despite mixed findings [32–34]) [9, 14, 18, 34].

PMI asserts that IQOS’ target market is current cigarette smokers [35–37]—and ‘not’ young people [35–37]. While research from the United States [38, 39] and other countries (e.g. Israel [10], Italy [40] and Korea [41]) indicates that those using IQOS also more likely smoke cigarettes and/or e-cigarettes, those who never smoked (versus currently smoke) are equally or more likely to have tried or intend to try IQOS [40], and IQOS marketing targets youth and young adults [9, 18, 42], who also show relatively high use and interest in use [38, 43]. Additionally, HTP use is more prevalent among men and racial/ethnic minorities [38, 39, 44].

Given the importance of marketing and its influences on perceptions of HTPs and other newer tobacco products among different consumer subgroups, this mixed-methods study aimed to provide insights regarding perceptions of IQOS and its marketing among US and Israeli adults. Despite these countries’ distinct IQOS regulatory histories and use rates, IQOS has been marketed using similar advertising content and marketing channels in these countries [9, 18, 44–46], and PMI has used IQOS’ US FDA reduced exposure authorization in its Israel-based marketing [44]. We hypothesized that IQOS and its marketing would be perceived more favorably among certain subgroups, including those who currently use other tobacco products (particularly cigarettes and/or e-cigarettes) and those aware of or who have used HTPs (including those in Israel where IQOS has a longer history and higher use rates [10]).

Materials and Methods

We analyzed data from a tobacco-related study among US and Israeli adults, particularly pertaining to HTPs given their distinct histories but similar marketing in the US and Israel [10]. This study used a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design (i.e. quantitative data collection, followed by qualitative data to explain quantitative findings); such designs are strategic when quantitative findings can be better understood through such qualitative approaches [47]. The study received ethical approvals from George Washington University (NCR213416) and Hebrew University (27062021). The current study analyzed (i) cross-sectional survey data (collected in October–December 2021) and (ii) semi-structured interviews (conducted in Spring 2022). This study adhered to STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cross-sectional quantitative research and Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines for qualitative research.

Quantitative data

Participants

Eligibility criteria included respective country citizenship, age 18–45 years (because alternative tobacco product use is most prevalent among those ≤45 years [48–50]) and able to speak English (United States) or Hebrew or Arabic (Israel). In each country, we aimed for sufficient numbers reporting current tobacco use (40–50%) and representing the sexes (∼50% each) and country-specific racial/ethnic targets.

In the United States, racial/ethnic quotas were ∼45% White, ∼25% Black, ∼15% Asian, and ∼15% Hispanic. The US survey was conducted primarily using KnowledgePanel®, a probability-based web panel designed to be representative (recruited via random-digit dialing and address-based sampling), supplemented with off-panel recruitment (via banner ads and web pages) to meet subgroup recruitment targets (i.e. Asian reporting tobacco use). Of 4960 panelists recruited, 2397 (48.3%) completed eligibility screening and 1095 (45.7%) completed the survey; of 353 off-panel individuals screened, 33 (9.3%) were eligible and completed the survey.

The Israeli survey was conducted using opt-in sampling and ethnic targets of ∼85% Jewish and ∼15% Arab. Ipsos recruited the opt-in sample through a blend of sources, primarily by using banner ads, web pages and e-mail invitations. Those who clicked online ads were sent to a study landing page. Ipsos used a pre-screening process to ensure eligibility (age, citizenship and language) and reach subgroup quotas (sex, ethnicity and tobacco use). Of 2970 individuals screened, eligible and allowed to advance to the survey (i.e. target enrollment not yet reached), 1094 (36.8%) completed the survey.

Measures

Supplementary Table S1 provides specific assessments administered.

IQOS product and marketing assessment

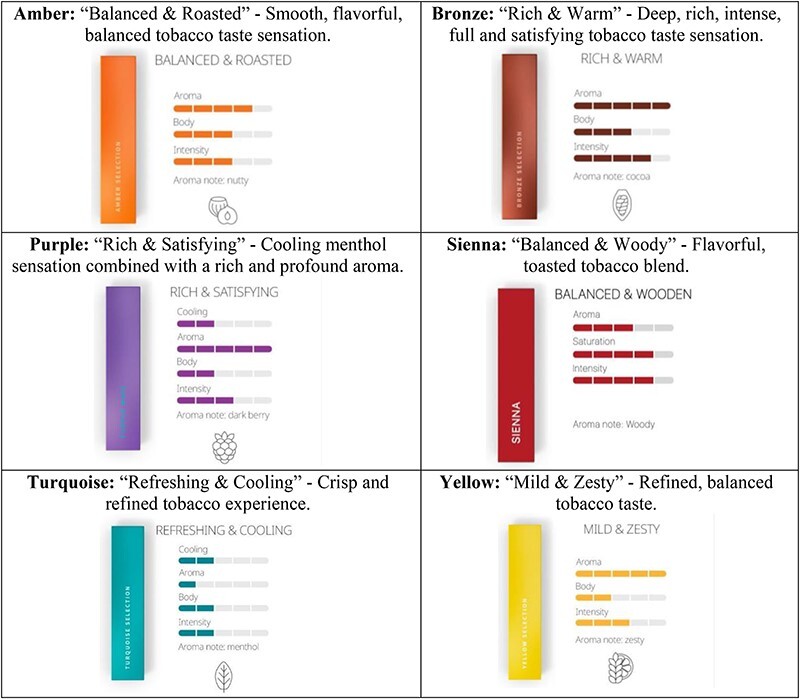

Participants were presented with a photo of IQOS (Fig. 1a) and its description (i.e. ‘…heats but doesn’t burn tobacco and consists of the device, charger, and heatstick’). They were then asked, ‘Before beginning this survey, had you heard of heated tobacco products, like IQOS?’ Then, participants were asked to rate the appeal of its overall design, technology, device colors (Fig. 1b), accessories/customization (Fig. 1b), flavors (e.g. amber, bronze, purple, sienna, turquoise and yellow; see Fig. 2 for flavor descriptions), maintenance and specialty stores (Fig. 1c); response options were 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = neutral/unsure, 4 = somewhat and 5 = very. Participants were also asked to rank in order the three flavors they (i) would be most likely to try and (ii) perceived as least harmful. They were also provided the average cost of the device and heatsticks and assessed cost (1 = much too cheap to 5 = much too expensive). Participants were also asked, ‘For each of the following slogans, indicate the extent to which each might persuade you to try IQOS?’ (see Table II for full list; 1 = not at all to 5 = very). Responses to marketing messages were averaged to create a ‘marketing message persuasiveness index score’ (Cronbach’s α = 0.96). An overall product/marketing ‘appeal index score’ was created by taking an average of each product attribute score (e.g. design, technology and colors) and message persuasiveness score (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Fig. 1.

IQOS product design, colors, accessories and retailers.

Fig. 2.

IQOS flavors.

Table II.

Bivariate comparisons regarding sociodemographics, tobacco use characteristics and appeal of IQOS product and marketing across cigarette and e-cigarette use groups of adults in the United States and Israel

| Variables | Total N = 2222 (100%) |

No cigarette or e-cigarette use n = 1396 (62.8%) |

Cigarette/ no e-cigarette n = 381 (17.1%) |

E-cigarette/ no cigarette n = 145 (6.5%) |

Dual cigarette/ e-cigarette use n = 300 (13.5%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Israel (versus United States) resident, n (%) | 1094 (49.2) | 601 (43.1) | 218 (57.2) | 65 (44.8) | 210 (70.0) | <0.001 |

| Age, M (SD) | 32.19 (7.74) | 32.32 (7.81) | 33.28 (7.46) | 30.04 (7.42) | 31.22 (7.67) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 1118 (50.3) | 743 (53.2) | 176 (46.2) | 64 (44.1) | 135 (45.0) | 0.005 |

| College degree or more, n (%) | 953 (42.9) | 635 (45.5) | 139 (36.5) | 53 (36.6) | 126 (42.0) | 0.005 |

| Married/cohabitating, n (%) | 1186 (53.4) | 732 (52.4) | 176 (53.8) | 72 (49.7) | 177 (59.0) | 0.162 |

| Children <18 years in the home, n (%) | 1125 (50.6) | 701 (50.2) | 185 (48.6) | 66 (45.5) | 173 (57.7) | 0.042 |

| HTP awareness, n (%) | 677 (30.5) | 292 (20.9) | 147 (38.6) | 55 (37.9) | 183 (61.0) | 0.001 |

| Past 30-day use, n (%) | ||||||

| Cigarettes | 681 (30.6) | 0 (0.0) | 381 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 300 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Days of use in those with past 30-day use, M (SD) | 15.85 (11.77) | 0 (0.00) | 17.09 (12.12) | 0 (0.00) | 14.28 (11.13) | 0.002 |

| E-cigarettes | 445 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 145 (100.0) | 300 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Days of use in those with past 30-day use, M (SD) | 10.54 (10.62) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 13.97 (12.45) | 8.89 (9.19) | <0.001 |

| HTPs | 172 (7.7) | 9 (0.6) | 53 (13.9) | 22 (15.2) | 88 (29.3) | <0.001 |

| Days of use in those with past 30-day use, M (SD) | 5.84 (5.52) | 3.11 (3.06) | 5.36 (4.96) | 3.64 (3.13) | 6.95 (6.21) | 0.020 |

| Appeal of IQOS product and marketing, M (SD)a | ||||||

| IQOS design | 2.69 (1.40) | 2.38 (1.35) | 3.00 (1.33) | 3.11 (1.32) | 3.53 (1.25) | <0.001 |

| IQOS technology | 2.57 (1.36) | 2.24 (1.28) | 2.90 (1.34) | 3.08 (1.28) | 3.47 (1.20) | <0.001 |

| IQOS colors | 2.99 (1.49) | 2.73 (1.47) | 3.29 (1.47) | 3.32 (1.40) | 3.66 (1.37) | <0.001 |

| IQOS accessories, customization | 2.91 (1.47) | 2.67 (1.45) | 3.16 (1.45) | 3.26 (1.50) | 3.55 (1.32) | <0.001 |

| IQOS flavors | 2.79 (1.44) | 2.45 (1.38) | 3.17 (1.37) | 3.23 (1.37) | 3.67 (1.24) | <0.001 |

| Likelihood of entering IQOS store | 2.05 (1.32) | 1.60 (1.04) | 2.57 (1.40) | 2.62 (1.34) | 3.19 (1.29) | <0.001 |

| IQOS maintenance reduces appealc | 2.86 (1.33) | 2.77 (1.34) | 2.98 (1.34) | 3.08 (1.34) | 3.03 (1.24) | <0.001 |

| IQOS cost evaluationb, c | 3.89 (1.00) | 3.93 (1.02) | 3.85 (1.01) | 3.89 (0.97) | 3.82 (0.96) | 0.264 |

| Persuasiveness of IQOS marketing messages | ||||||

| Real tobacco meets innovative technology | 2.22 (1.33) | 1.78 (1.13) | 2.73 (1.33) | 2.87 (1.35) | 3.27 (1.20) | <0.001 |

| Go Smoke-free, Go IQOS | 2.26 (1.33) | 1.89 (1.19) | 2.61 (1.29) | 2.85 (1.38) | 3.28 (1.23) | <0.001 |

| True tobacco taste | 2.11 (1.28) | 1.69 (1.05) | 2.59 (1.28) | 2.68 (1.38) | 3.14 (1.27) | <0.001 |

| Meet IQOS: real tobacco, no ash, less odor | 2.39 (1.41) | 1.90 (1.22) | 3.02 (1.33) | 3.07 (1.40) | 3.52 (1.17) | <0.001 |

| Moving beyond smoking | 2.26 (1.37) | 1.88 (1.21) | 2.62 (1.36) | 2.97 (1.42) | 3.22 (1.29) | <0.001 |

| Change to tobacco without smoke and ashes | 2.26 (1.38) | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.75 (1.37) | 2.96 (1.45) | 3.28 (1.24) | <0.001 |

| The future of tobacco has arrived | 2.23 (1.36) | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.59 (1.36) | 3.28 (1.27) | 2.23 (1.36) | <0.001 |

| A cleaner way to use tobacco | 2.43 (1.41) | 1.97 (1.24) | 2.98 (1.36) | 3.24 (1.40) | 3.47 (1.17) | <0.001 |

| This changes everything | 2.22 (1.36) | 1.83 (1.19) | 2.60 (1.37) | 2.94 (1.44) | 3.19 (1.27) | <0.001 |

| Your IQOS, Your way | 2.12 (1.32) | 1.74 (1.12) | 2.51 (1.33) | 2.66 (1.41) | 3.14 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| Message persuasiveness scored | 2.25 (1.14) | 1.83 (0.99) | 2.70 (1.03) | 2.91 (1.10) | 3.27 (0.91) | <0.001 |

| Overall IQOS product and marketing appeal scorec, e | 2.93 (0.81) | 2.68 (0.73) | 3.11 (0.78) | 3.16 (0.75) | 3.47 (0.75) | <0.001 |

| Flavor most likely to use, n (%)f | <0.001 | |||||

| Turquoise | 518 (23.6) | 353 (25.7) | 75 (19.8) | 33 (22.8) | 57 (19.0) | |

| Amber | 472 (21.5) | 296 (21.5) | 95 (25.1) | 27 (18.6) | 54 (18.0) | |

| Purple | 473 (21.5) | 268 (19.5) | 97 (25.6) | 33 (22.8) | 75 (25.0) | |

| Bronze | 306 (13.9) | 174 (12.7) | 55 (18.0) | 19 (13.1) | 58 (19.3) | |

| Yellow | 228 (10.4) | 168 (12.2) | 29 (7.7) | 13 (9.0) | 18 (6.0) | |

| Sienna | 202 (9.2) | 116 (8.4) | 28 (7.4) | 20 (13.8) | 38 (12.7) | |

| Flavor perceived least harmful, n (%)f | <0.001 | |||||

| Turquoise | 852 (38.6) | 557 (40.3) | 144 (38.0) | 56 (38.6) | 95 (31.7) | |

| Amber | 410 (19.0) | 281 (20.3) | 57 (15.0) | 27 (18.6) | 55 (18.3) | |

| Yellow | 328 (14.9) | 212 (15.4) | 63 (16.6) | 24 (16.6) | 29 (9.7) | |

| Bronze | 231 (10.5) | 119 (8.6) | 45 (11.9) | 14 (9.7) | 53 (17.7) | |

| Purple | 211 (9.6) | 128 (9.3) | 41 (10.8) | 12 (8.3) | 30 (10.0) | |

| Sienna | 163 (7.4) | 84 (6.1) | 29 (7.7) | 12 (8.3) | 38 (12.7) |

Notes: Bold indicates P < 0.05. a1 = not at all to 5 = very.

1 = much too cheap to 5 = much too expensive.

Excluded in appeal score due to low Cronbach’s α.

Cronbach’s α = 0.96.

Index score includes design, technology, color, accessories, maintenance, flavors, likelihood to enter store, cost and slogan persuasiveness score. Cronbach’s α = 0.79.

Presents top rank for: ‘Based on how each flavor is described and presented, please rank in order the 3 flavors: (1) you would be most likely to try; and (2) you think are the least harmful to use.’

Tobacco use

We assessed the past 30-day (current) use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes and HTPs (yes/no) [51, 52]. To determine how to operationalize tobacco use variables, exploratory analyses examined current and lifetime use of each and the overlap. Lifetime and current use (respectively) were 54.1% and 30.6% for cigarettes, 37.4% and 20.0% for e-cigarettes, and 13.8% and 7.7% for HTPs. Among those ‘currently’ using HTPs (n = 172), (i) 94.8% (n = 163) also currently used (a) cigarettes but not e-cigarettes (30.8%), (b) e-cigarettes but not cigarettes (12.8%) or (c) both (51.2%) and (ii) only 5.2% (n = 9) currently used only HTPs. Among those reporting ‘lifetime’ HTP use (n = 307), (i) 76.2% (n = 234) also currently used (a) cigarettes but not e-cigarettes (28.3%), (b) e-cigarettes but not cigarettes (11.7%) or (c) both (36.2%) and (ii) 23.8% (n = 73) reported not currently using cigarettes or e-cigarettes. In those reporting ‘lifetime HTP but not current cigarette or e-cigarette use’ (n = 73), (i) 91.8% (n = 67) reported lifetime use of (a) cigarettes but not e-cigarettes (11.0%), (b) e-cigarettes but not cigarettes (24.7%) or (c) both (56.2%) and (ii) only 8.2% (n = 6) ever used HTPs only. Given that we did not assess the extent of HTP use among those with lifetime HTP use or how HTP, cigarette and e-cigarette use levels compared, we categorized participants based on current cigarette and e-cigarette use (i.e. cigarettes/no e-cigarettes, e-cigarettes/no cigarettes and dual/both) and accounted for current HTP use separately. However, supplementary analyses also compared participants reporting never, former (lifetime but not current) and current HTP use. [Note that current use prevalence of hookah, cigars, pipe and smokeless tobacco was low (5–13%) and 80–95% overlapped with current cigarette or e-cigarette use [10]; thus, analyses did not account for these products separately.]

Sociodemographic covariates

We included country, age, sex, education, relationship status and children in the home.

Data analysis

Descriptive and bivariate analyses characterized participants’ sociodemographics, tobacco use characteristics and appeal of IQOS product and marketing factors. Associations between HTP use group and appeal were as expected (i.e. never use related to least appeal and current use related to greatest appeal), and country-specific analyses showed few differences in associations of sociodemographics and tobacco use characteristics to appeal. Thus, primary analyses examined differences in appeal by cigarette/e-cigarette use group—accounting for HTP use separately—with the entire cross-country sample, allowing examination of differences between Israeli and US participants, accounting for other factors.

Then, multivariable linear regression analyses examined sociodemographic covariates, country, HTP awareness, current HTP use and cigarette/e-cigarette use subgroups in relation to the overall product/marketing appeal index score, using the ‘neither cigarette/e-cigarette use’ group as the referent group. Subsequently, a similar regression model was conducted, excluding participants reporting using neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes in order to contrast the three use subgroups with one another (using dual use as the referent group). Country-specific regression analyses were also conducted. Analyses were conducted using SPSS (v27.0) and alpha = 0.05.

Qualitative data

Participants

Participants in both countries were purposively recruited for representation by sex, race/ethnicity and tobacco use. The US participants were recruited from the online survey sample (i.e. called/emailed invitations). In Israel, the opt-in sample for the online survey precluded our ability to re-contact survey participants; instead, we promoted the study via ads on Facebook; individuals who clicked ads were provided study description, consented and screened for eligibility (i.e. ≥18 years, speak Hebrew/Arabic and current or former cigarette use) and to reach subgroup targets (i.e. sex and ethnicity).

Assessment

Each interview was conducted online via Zoom in English (United States) or Hebrew/Arabic (Israel; participant’s choice), audio-recorded, ∼45 min long, and incentivized (USD$25 or 100 New Israeli Shekels). The interview guide first described IQOS using the same description as in the survey and stated, ‘IQOS began being sold in the US in Fall 2019; however, IQOS stopped being sold in the US in November 2021 because of a lawsuit with another tobacco company.’ Participants were asked, ‘Did you: hear about IQOS before today? See IQOS ads? See articles in newspapers, magazines, or online about IQOS? Try/use IQOS?’ Participants without prior use were asked, ‘Would you try IQOS?’ Those who currently or ever used IQOS were asked about their use (i.e. frequency, when, where and why). Then, participants were asked, ‘What do you think about IQOS? What is appealing? What concerns might you have? Who do you think it is meant for? How does it compare to [cigarettes; e-cigarettes]?’

Qualitative analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed. Data were analyzed using deductive-inductive thematic analysis [53]. Preliminary deductive codes were compiled based on the interview guide and preliminary review of US-based transcripts. Then, a subsample of eight US transcripts and eight translated Arabic and Hebrew interviews (n = 4 each) were independently reviewed by two US-based coders and two Israeli-based coders. An iterative process was used to assess inter-rater reliability, reach consensus, inform revisions, yield additional codes based on emergent themes and finalize the codebook [53]. After ensuring sufficient inter-rater reliability (>80%), the remainder of the interviews were coded. Themes were summarized, any differences across countries were noted, and quotes were selected to represent themes and different use profiles. (Note that comparing qualitative responses/themes by distinct tobacco use subgroups was complex and yielded limited insights due to overlap in current and lifetime product use.)

Results

Survey and interview participant characteristics are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Sociodemographics and tobacco use characteristics of survey participants (N = 2222) and interview participants (N = 84)

| Survey participants | Interview participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 2222) |

United States (n = 1128) |

Israel (n = 1094) |

Total (N = 84) |

United States (n = 40) |

Israela (n = 44) |

|

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 32.19 (7.74) | 34.11 (7.23) | 30.21 (7.76) | 32.90 (6.27) | 36.50 (6.25) | 29.35 (6.20) |

| Female, n (%) | 1118 (50.3) | 562 (49.8) | 556 (50.8) | 40 (45.5) | 17 (42.5) | 23 (52.3) |

| US race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 493 (22.2) | 493 (43.7) | 13 (14.8) | 13 (32.5) | – | |

| Black | 284 (12.8) | 284 (25.2) | – | 13 (14.8) | 13 (32.5) | – |

| Asian | 177 (8.0) | 177 (15.7) | – | 5 (5.7) | 5 (12.5) | – |

| Hispanic | 174 (7.8) | 174 (15.4) | – | 9 (10.2) | 9 (22.5) | – |

| Israel ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Jewish | 954 (42.9) | – | 954 (87.2) | 39 (44.3) | – | 39 (88.6) |

| Arab | 140 (6.3) | – | 140 (12.8) | 5 (5.7) | – | 5 (11.4) |

| HTP awareness, n (%) | 677 (30.5) | 244 (21.6) | 433 (39.6) | – | – | — |

| Past 30-day use, n (%) | b | |||||

| Cigarettes | 681 (30.6) | 253 (22.4) | 428 (39.1) | 41 (46.6) | 17 (42.5) | 24 (54.5) |

| E-cigarettes | 445 (20.3) | 170 (15.5) | 275 (25.2) | 18 (21.4) | 18 (45.0) | 1 (2.3) |

| HTPs | 172 (7.8) | 36 (3.2) | 136 (12.5) | 13 (15.5) | 6 (15.0) | 7 (15.9) |

| Past 30-day cigarette/e-cigarette use group, n (%) | c | |||||

| Neither cigarette/e-cigarette use | 1396 (62.8) | 795 (70.5) | 601 (54.9) | – | 12 (30.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cigarette/no e-cigarette | 381 (17.1) | 163 (14.5) | 218 (19.9) | – | 10 (25.0) | 234 (52.3) |

| E-cigarette/no cigarette | 145 (6.5) | 80 (7.1) | 65 (5.9) | – | 11 (27.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dual cigarette/e-cigarette use | 300 (13.5) | 90 (8.0) | 210 (19.2) | – | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.3) |

Notes: aIn Israel, the opt-in sample for the online survey precluded re-contacting survey participants; instead, we promoted the study via ads on Facebook. Potential participants were provided a study description, consented and screened for eligibility (i.e. ≥18 years old, speak Hebrew or Arabic and reported current or former cigarette use); thus, not all measures/sample targets align exactly.

Outside of current use: n = 20 (45.5%) reported former use of cigarettes, n = 38 (86.4%) e-cigarettes and n = 12 (27.3%) HTPs.

Current neither cigarette/e-cigarette use included five reporting current HTP use; current cigarette/no e-cigarette only group included 20 former e-cigarette use (one of which reported current HTP use); one participant reporting current dual cigarette/e-cigarette use reported never HTP use.

Quantitative results

Product attributes reported as most highly appealing were colors (M = 2.99, SD = 1.49), accessories/customization (M = 2.91, SD = 1.47), flavors (M = 2.79, SD = 1.44), design (M = 2.69, SD = 1.40) and technology (M = 2.57, SD = 1.36; Table II). On average, participants were neutral regarding maintenance (M = 2.86, SD = 1.33), perceived IQOS as somewhat expensive (M = 3.89, SD = 1.00) and were a little likely to enter an IQOS store (M = 2.05, SD = 1.32).

Bivariate analyses by cigarette/e-cigarette use subgroup

Across subgroups (62.8% neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes, 17.1% cigarette/no e-cigarette, 6.5% e-cigarette/no cigarette and 13.5% dual cigarette/e-cigarette), IQOS awareness and appeal of product attributes (except cost) differed (P’s < 0.001; Table II). In post hoc analyses, those using neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes (versus others) were less aware and reported less appeal, while those reporting dual (versus cigarette/no e-cigarette and e-cigarette/no cigarette) use reported greater awareness and generally greater appeal (except colors and customization versus e-cigarette/no cigarette).

Elaborating on flavors (Table II), the flavor most likely to be tried was turquoise for the neither cigarette/e-cigarette use group (25.7%) and purple for the cigarette/no e-cigarette (25.6%) and dual use groups (25.0%). The e-cigarette/no cigarette use group reported being equally likely to try turquoise and purple (22.8%). All groups reported least likely trying either sienna (9.2% overall; least likely for non-use and cigarette/no e-cigarette) or yellow (10.4% overall; least likely for e-cigarette/no cigarette and dual use). The flavor perceived as least harmful by each group was turquoise (38.6%);sienna was least often perceived as least harmful (7.4%), followed by purple (9.6%) and bronze (10.5%).

Regarding advertising messages (Table II), all four groups rated the following as most persuasive: ‘A cleaner way to use tobacco’ (M = 2.43, SD = 1.41) and ‘Meet IQOS: real tobacco, no ash, less odor’ (M = 2.39, SD = 1.41). Messages perceived least persuasive were as follows: ‘True tobacco taste’ (M = 2.11, SD = 1.28) and ‘Your IQOS, Your way’ (M = 2.12, SD = 1.32). All messages were perceived as more persuasive among those using neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes (versus others) and less persuasive among those reporting dual versus single-product use and e-cigarette/no cigarette use (except three relative to e-cigarette/no cigarette use: ‘Moving beyond smoking’, ‘A cleaner way to use tobacco’ and ‘This changes everything’). Those reporting e-cigarette/no cigarette versus cigarette/no e-cigarette use perceived three messages as more persuasive (‘Moving beyond smoking’, ‘The future of tobacco has arrived’ and ‘This changes everything’).

Supplementary bivariate analysis by HTP use

Participants never using HTPs reported the least product/marketing appeal; participants currently using HTPs reported the greatest appeal (Supplementary Table S2). Participants reporting former and current HTP use most frequently indicated purple as the flavor they would most likely use (25.6% and 30.8%, respectively); those never using HTPs most frequently indicated turquoise (25.1%). The flavor perceived as least harmful was turquoise for those reporting never and former HTP use (40.2% and 39.3%) and bronze for those currently using HTPs (21.5%).

Multivariable linear regression: overall product/marketing appeal

Compared to those using neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes (Table III, upper panel), those reporting cigarette/no e-cigarette (β = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.49, 0.72), e-cigarette/no cigarette (β = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.58, 0.92) or dual use (β = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.86, 1.13) reported greater overall appeal of IQOS attributes/marketing. In analyses excluding those using neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes (Table III, lower panel), compared to those reporting dual cigarette/e-cigarette use, those reporting cigarette/no e-cigarette (β = −0.14, 95% CI = −0.33, −0.02) or e-cigarette/no cigarette use (β = −0.27, 95% CI = −0.47, −0.07) reported lower overall appeal of IQOS attributes/marketing. Additionally, those who were aware of HTPs, those in Israel (versus United States) and men reported greater overall appeal in both models; current HTP use was not (Table III). Country-specific analyses showed similar trends; however, men reported greater appeal in Israel but not in the United States and HTP use was positively associated with appeal in the United States but not Israel (Supplementary Table S3).

Table III.

Multivariable regression analyses examining correlates of overall appeal of IQOS marketing across cigarette and e-cigarette use groups

| Model including non-use group (N = 2222): referent group: neither cigarette/e-cigarette usea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | 95% CI | P-value |

| Constant | 1.86 | 1.63, 2.10 | <0.001 |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Israel (ref: United States) | 0.36 | 0.27, 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.001 | −0.005, 0.007 | 0.782 |

| Male (ref: female) | 0.11 | 0.03, 0.19 | 0.009 |

| ≥College degree (ref: <) | 0.06 | −0.03, 0.14 | 0.196 |

| Children in the home (ref: no) | −0.02 | −0.10, 0.06 | 0.632 |

| HTP awareness (ref: no) | 0.19 | 0.10, 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Past 30-day HTP use (ref: no) | 0.14 | −0.02, 0.31 | 0.090 |

| Past 30-day cigarette/e-cigarette use (ref: neither cigarette/e-cigarette use) | |||

| Cigarette/no e-cigarette | 0.60 | 0.49, 0.72 | <0.001 |

| E-cigarette/no cigarette | 0.75 | 0.58, 0.92 | <0.001 |

| Dual cigarette/e-cigarette use | 1.00 | 0.86, 1.13 | <0.001 |

| Adjusted R-square = 0.215 | |||

| Model excluding non-use group (N = 826): referent group: dual cigarette/e-cigarette usea | |||

| Variable | B | 95% CI | P-value |

| Constant | 2.43 | 2.12, 2.93 | <0.001 |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Israel (ref: United States) | 0.22 | 0.07, 0.37 | 0.005 |

| Age | 0.003 | −0.007, 0.01 | 0.551 |

| Male (ref: female) | 0.15 | 0.01, 0.29 | 0.035 |

| ≥College degree (ref: <) | 0.09 | −0.06, 0.23 | 0.226 |

| Children in the home (ref: no) | 0.002 | −0.14, 0.14 | 0.978 |

| HTP awareness (ref: no) | 0.23 | 0.08, 0.37 | 0.002 |

| Past 30-day HTP use (ref: no) | 0.13 | −0.05, 0.31 | 0.147 |

| Past 30-day cigarette/e-cigarette use (ref: dual cigarette/e-cigarette use) | |||

| Cigarette/no e-cigarette | −0.14 | −0.33, −0.02 | 0.040 |

| E-cigarette/no cigarette | −0.27 | −0.47, −0.07 | 0.009 |

| Adjusted R-square = 0.078 | |||

Notes: Bold indicates P < 0.05. aAlso represents those with past 30-day HTP use (n = 172): (i) neither cigarette/e-cigarette (i.e. HTP use only, n = 9, 5.2%); (ii) cigarette/no e-cigarette (n = 53, 30.8%); (iii) e-cigarette/no cigarette (n = 22, 12.8%); and (iv) dual cigarette/e-cigarette (n = 88, 51.2%). In models comparing cigarette/no e-cigarette and e-cigarette/no cigarette, no differences were found.

Qualitative results

Qualitative data (Table IV) indicated similar themes across countries.

Table IV.

Qualitative findings regarding IQOS awareness, exposure, perceptions and use among US and Israeli adults, N = 84a

| Representative quotes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Themes | United States | Israel |

| IQOS awareness, exposure and perceived target market | ||

| Awareness |

|

|

| Source of exposure | ||

| Social network |

|

|

| Advertisements (via retailers, online and social media) |

|

|

| Perceived target market | ||

| Young people |

|

|

| People looking for an alternative to cigarettes |

|

|

| Females |

|

|

| IQOS product perceptions | ||

| General perceptions |

|

|

| Comparisons to cigarettes | ||

| Harm to health | ||

| -Less harmful |

|

|

| -Same harm |

|

|

| Addictiveness | ||

| -Same addictiveness |

|

|

| -Less addictive |

|

|

| -More addictive |

|

|

| Technology |

|

|

| Complexity | ||

| -Less complex |

|

|

| -More complex |

|

|

| Cost |

|

|

| Smell |

|

|

| Environmental harms |

|

|

| Comparisons to e-cigarettes | ||

| Harm to health | ||

| -Same harmfulness |

|

|

| -Less harmful |

|

|

| -More harmful |

|

|

| -Uncertain |

|

|

| Addictiveness | ||

| -Same addictiveness |

|

|

| -Less addictive |

|

|

| Technology |

|

|

| Complexity | ||

| -Equal complexity |

|

|

| -Less complex |

|

|

| -More complex |

|

|

| Willingness to try IQOS | ||

| Willing |

|

|

| Conditionally willing |

|

|

| Unwilling |

|

|

Note: aNo current HTP use unless noted. NH = non-Hispanic.

IQOS awareness, exposure and perceived target market

Some participants were aware of IQOS; notably, some were unable to clearly discern IQOS from other electronic tobacco/nicotine products. Across countries, major sources of IQOS exposures were social networks (e.g. friends and colleagues), particularly for those who had tried IQOS, and advertisements at retailers (e.g. convenience stores) or online, particularly social media.

The majority perceived that IQOS targeted young people because of its technology, sleek design, less smell and social acceptability, and some expressed concerns about targeting youth. The majority also identified people seeking cigarette alternatives as a target market, given the potential benefits over cigarettes promoted in IQOS marketing (e.g. secondhand smoke reduction and convenience) as well as some unique attributes like the flavor and technology that distinguish IQOS from cigarettes. Some also perceived IQOS and its marketing as ‘female-driven’ due to its design, colors and flavor descriptions.

Perceptions of IQOS

Participants perceived IQOS to have some appealing attributes, particularly its design (e.g. ‘elegant’ and ‘aesthetically pleasing’), technology, various colors and flavors and potentially less byproduct exposure. However, some commented on IQOS complexity (e.g. ‘looks complicated’), cost and limited retail accessibility (e.g. ‘not available everywhere’), which posed barriers to adopting use.

Relative advantage of IQOS versus cigarettes

About half believed that IQOS and cigarettes were equally harmful and addictive, as they both heat or burn tobacco and contain nicotine. However, about half perceived IQOS use and its byproducts as less harmful (e.g. ‘less smoke’ and ‘dissipates quicker’) and believed that IQOS was less addictive, often suggesting that IQOS was not the ‘real’ or ‘hardcore thing’ but could help reduce cigarette use. Others perceived IQOS as more addictive, commenting that its flavors or underestimating IQOS harms could lead to more frequent use and addiction.

Most perceived that IQOS technology was more advanced than cigarettes. However, perceived complexity was mixed: some perceived IQOS as less complex (e.g. due to the all-in-one nature, chargeability and ability to use discretely) and others as more complex (e.g. charging and distinct components needed). IQOS was often perceived as more expensive than cigarettes but to have environmental benefits over cigarettes (i.e. less potential for litter).

Relative advantage of IQOS versus e-cigarettes

Some participants perceived IQOS and e-cigarettes as equally harmful and addictive, due to similar technology and containing nicotine. Some perceived IQOS as less harmful (e.g. does not involve vapor and related lung damage) and less addictive (e.g. e-cigarette e-liquids with high nicotine concentrations). Others perceived IQOS as more harmful given that its byproducts were similar to smoke. However, many were uncertain (e.g. due to IQOS newness, more research needed).

Participants generally perceived IQOS and e-cigarette technology as similar. Further, many perceived IQOS and e-cigarettes as equally complex, while some perceived IQOS as less complex (e.g. small, no need for e-liquids and all-in-one) or more complex (e.g. too many components).

Willingness to try IQOS

Willingness varied. Those willing to try IQOS commented on its attractive design, technology and flavors. Some mentioned that their willingness depended on cost and ability to try it, for example, its flavors, nicotine content and holding it. Some expressed their unwillingness to try IQOS, due to its complexity or nicotine content.

Discussion

This study aimed to advance the evidence-base informing tobacco regulations by assessing reactions to industry marketing elements, specifically IQOS product characteristics and advertising messages [54, 55]. Notably, 82.0% of participants currently using HTPs also currently used cigarettes, with 62.4% of these also using e-cigarettes; an additional 12.8% of those currently using HTPs used e-cigarettes but not cigarettes. These findings undermine the notion that those who use cigarettes will switch completely to IQOS and reinforce concerns about dual use of IQOS with other tobacco products, particularly cigarettes, and related health effects [56].

Survey participants not using cigarettes/e-cigarettes, versus using either or both, perceived IQOS and its marketing as less appealing; those with dual cigarette/e-cigarette use reported the greatest appeal. Further, interview participants perceived target markets to include those using cigarettes but looking for an alternative. These findings corroborate PMI’s assertion that IQOS targets adults using cigarettes [35–37]. However, those reporting dual cigarette/e-cigarette use or e-cigarette/no cigarette use, who rated IQOS attributes and messaging as most favorable, were among the youngest subgroups; these findings also suggest that dual use groups might be unable or unwilling to entirely switch from cigarettes to another product, and/or IQOS technology might attract those using e-cigarettes. Furthermore, participants perceived IQOS’ target markets include youth and young adults, those not using cigarettes and females, which highlight concerns regarding IQOS’ impact on the nicotine-naïve and potential targeting of these and other groups who might be disproportionately impacted, as corroborated in other IQOS use and marketing surveillance research [9, 18, 35–40, 42–44].

Interview participants noted advertising as an influential source of IQOS exposure, as previously documented [3, 16, 39, 57], and noted the appeal of IQOS design, colors, flavors, technology and potentially less byproduct exposure, also previously shown [3, 19, 34, 39, 58]. Among survey participants, attributes perceived most appealing were colors, followed by accessories/customization, flavors, design and technology. The most persuasive advertising messages focused on cleanliness (i.e. ‘A cleaner way to use tobacco’), while the least persuasive were vague. Furthermore, survey and interview participants indicated key barriers to trial or use, including IQOS expense, complexity and limited retail accessibility.

Interview participants generally perceived IQOS to have lower risks (i.e. harm and addictiveness) compared to cigarettes, as shown previously [20–25]. However, some perceived IQOS and cigarettes to have similar risks and findings regarding IQOS risks relative to e-cigarettes were mixed. Perceived risks were often tied to containing nicotine (relevant to all three products), nicotine concentrations, amount of emissions produced (less from IQOS and e-cigarettes) and the role of flavors in use (relevant to IQOS and e-cigarettes). While participants generally perceived IQOS technology more favorably than cigarettes’, views on its ease of use relative to cigarettes and e-cigarettes diverged. For example, IQOS was perceived as more complex than disposable e-cigarettes but less complex and more discrete than other types of e-cigarettes.

The flavor perceived as least harmful among each tobacco use group was turquoise (described as ‘Refreshing & Cooling’), while sienna was reportedly perceived as more harmful and least likely to be tried. Furthermore, those using neither cigarettes/e-cigarettes were participants reported being most likely to try turquoise in neither cigarette/e-cigarette and e-cigarette/no cigarette use groups and purple (‘Cooling menthol sensation…’) for both single-product use groups and the dual use groups. These findings reflect cigarette-related research indicating that cool colors (i.e. turquoise and purple) and the terms ‘cooling’ and ‘menthol’ may reduce perceived harm and increase appeal, while bold red colors convey greater harms [58–62].

Limitations

Despite study strengths (e.g. cross-country and mixed-methods design), findings have limited generalizability, as this study faced methodological challenges similar to many international studies [51, 52, 63]—differences in available resources (e.g. panels and census data) for sampling across countries. Survey participants were primarily recruited via a panel in the United States and opt-in sampling in Israel, requiring caution in terms of how the data are used. For example, rather than attempting to generate prevalence estimates, this study examined associations between participant characteristics (including those used to determine subgroup quotas) and IQOS perceptions—within the cross-country sample and within the country-specific samples, using multivariable analyses. Additionally, as with all qualitative samples, our interview samples have limited generalizability and were recruited to provide diverse, in-depth perspectives across key sociodemographic and tobacco use groups [64]—albeit using different approaches (i.e. recruited from the survey sample in the United States and via Facebook in Israel) which could have impacted the perspectives portrayed among US versus Israeli participants. Other limitations include the cross-sectional design (limiting causal inferences) and self-reported assessments (i.e. potential recall and social desirability biases).

Conclusions

Participants reporting dual cigarette/e-cigarette use (versus non-use or single-product use) indicated greater overall appeal of IQOS and its marketing; yet, qualitative data indicated mixed perceptions regarding IQOS advantages (e.g. harm, addiction and complexity) compared to cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Participants perceived that IQOS targets those seeking alternatives to cigarettes but also young people, people not using cigarettes and females. Notably, the product attributes rated most appealing were IQOS colors, accessories/customization and flavors—attributes likely targeting younger consumers. Given the perceived target markets, IQOS youth-oriented product attributes and particular appeal to dual cigarette/e-cigarette use groups, ongoing monitoring of IQOS marketing is key to assessing its population impact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Yuxian Cui, Department of Prevention and Community Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, 950 New Hampshire Avenue, Washington, DC 20052, USA.

Yael Bar-Zeev, Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah Medical Center, 7 Ramat Gan, Jerusalem, 9112102, Israel.

Hagai Levine, Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah Medical Center, 7 Ramat Gan, Jerusalem, 9112102, Israel.

Cassidy R LoParco, Department of Prevention and Community Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, 950 New Hampshire Avenue, Washington, DC 20052, USA.

Zongshuan Duan, School of Public Health, Georgia State University, 140 Decatur St. SE, Atlanta, GA 30303, USA.

Yan Wang, GW Cancer Center, George Washington University, 800 22nd Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA.

Lorien C Abroms, GW Cancer Center, George Washington University, 800 22nd Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA.

Amal Khayat, Braun School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah Medical Center, 7 Ramat Gan, Jerusalem, 9112102, Israel.

Carla J Berg, GW Cancer Center, George Washington University, 800 22nd Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at HEAL online.

Author contributions

Yuxian Cui (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Yael Bar-Zeev (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing), Hagai Levine (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing), Cassidy R. LoParco (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing), Zongshuan Duan (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing), Yan Wang (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing), Lorien C. Abroms (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing), Amal Khayat (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing) and Carla J. Berg (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing).

Funding

US National Cancer Institute (R01CA239178, MPIs: Berg, Levine); National Cancer Institute (R01CA215155, PI: Berg; R01CA278229, MPIs: Berg, Kegler; R01CA275066, MPIs: Yang, Berg; R21CA261884, MPIs: Berg, Arem) to C.J.B.; Fogarty International Center (R01TW010664, MPIs: Berg, Kegler; D43TW012456, MPIs: Berg, Paichadze, Petrosyan); National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/Fogarty (D43ES030927, MPIs: Berg, Caudle, Sturua); National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA054751, MPIs: Berg, Cavazos-Rehg).

Conflict of interest statement

H.L. had received fees for lectures from Pfizer Israel Ltd (distributor of a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy in Israel) in 2017. L.C.A. receives royalties for the sale of Text2Quit. No other conflicts of interest are declared. Y.B.-Z. has received fees for lectures from Pfizer, Novartis NCH and GSK Consume Health (distributors of pharmacotherapy in Israel) in the past (2012–July 2019).

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request but are not publicly available for ethical reasons.

References

- 1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. 2018. Report No.: 0309468345.

- 2. World Health Organization . Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI): Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Products Information Sheet. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-HPR-2020.2. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 3. Berg CJ, Bar-Zeev Y, Levine H. Informing iQOS regulations in the United States: a synthesis of what we know. SAGE Open 2020; 10: 2158244019898823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Heated Tobacco Products. 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/heated-tobacco-products/index.html#what-are-htp. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 5. Henderson KC, Van Do V, Wang Y et al. Brief report on IQOS point-of-sale marketing, promotion and pricing in IQOS retail partner stores in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Tob Control 2023; 32: e260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Food and Drug Administration . Exposure Modification Modified Risk Granted Orders, FDA Submission Tracking Numbers (STNs): MR0000059-MR0000061, MR0000133, 2020. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/139797/download. Accessed: 6 Aug 2020.

- 7. Gretler C. Philip Morris IQOS Imports Barred from U.S.; Deadline Passes. 2021. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-29/philip-morris-iqos-imports-barred-from-u-s-as-deadline-passes?leadSource=uverify%20wall. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 8. Gretler C. Philip Morris Plans U.S. IQOS-Stick Production after Import Ban. Bloomberg News; 2022. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-10/philip-morris-plans-u-s-iqos-stick-production-after-import-ban. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 9. Duan Z, Levine H, Romm KF et al. IQOS marketing strategies and expenditures in the United States from market entrance in 2019 to withdrawal in 2021. Nicotine Tob Res 2023; 25: 1798–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levine H, Duan Z, Bar-Zeev Y et al. IQOS use and interest by sociodemographic and tobacco behavior characteristics among adults in the US and Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duan Z, Wysota CN, Romm KF et al. Correlates of perceptions, use, and intention to use heated tobacco products among US young adults in 2020. Nicotine Tob Res 2022; 24: 1968–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mathers A, Schwartz R, O’Connor S et al. Marketing IQOS in a dark market. Tob Control 2019; 28: 237–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halpern-Felsher B. Point-of-sale marketing of heated tobacco products in Israel: cause for concern. Isr J Health Policy Res 2019; 8: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Churchill V, Weaver SR, Spears CA et al. IQOS debut in the USA: Philip Morris International’s heated tobacco device introduced in Atlanta, Georgia. Tob Control 2020; 29: e152–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Khayat A et al. IQOS marketing strategies at point-of-sales: a cross-sectional survey with retailers. Tob Control 2023; 32: e198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abroms LC, Wysota CN, Tosakoon S et al. Industry marketing of tobacco products on social media: case study of Philip Morris International’s IQOS. Tob Control 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackler RK, Li VY, Cardiff RAL et al. Promotion of tobacco products on Facebook: policy versus practice. Tob Control 2019; 28: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berg CJ, Romm KF, Bar-Zeev Y et al. IQOS marketing strategies in the USA before and after US FDA modified risk tobacco product authorisation. Tob Control 2023; 32: 418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization . Heated tobacco products (HTPs) market monitoring information sheet, 2018. Available at: file:///T:/bsheprojs/CJ%20Berg/CJB%20Personal%208%2020%2016/Israel/WHO-NMH-PND-18.7-eng.pdf. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 20. East KA, Tompkins CNE, McNeill A et al. ‘I perceive it to be less harmful, I have no idea if it is or not:’ a qualitative exploration of the harm perceptions of IQOS among adult users. Harm Reduct J 2021; 18: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen-Sankey JC, Kechter A, Barrington-Trimis J et al. Effect of a hypothetical modified risk tobacco product claim on heated tobacco product use intention and perceptions in young adults. Tob Control 2023; 32: 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Havermans A, Pennings JLA, Hegger I et al. Awareness, use and perceptions of cigarillos, heated tobacco products and nicotine pouches: a survey among Dutch adolescents and adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021; 229: 109136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duan Z, Le D, Ciceron AC et al. ‘It’s like if a vape pen and a cigarette had a baby’: a mixed methods study of perceptions and use of IQOS among US young adults. Health Ed Res 2022; 37: 364–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chirila S, Antohe A, Isar C et al. Romanian young adult perceptions on using heated tobacco products following exposure to direct marketing methods. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2023; 33: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wężyk-Caba I, Kaleta D, Zajdel R et al. Do young people perceive e-cigarettes and heated tobacco as less harmful than traditional cigarettes? A survey from Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 14632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. El-Toukhy S, Baig SA, Jeong M et al. Impact of modified risk tobacco product claims on beliefs of US adults and adolescents. Tob Control 2018; 27: s62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berg CJ, Duan Z, Wang Y et al. Impact of different health warning label and reduced exposure messages in IQOS ads on perceptions among US and Israeli adults. Prev Med Rep 2023; 102209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berg CJ, Duan Z, Wang Y et al. Impact of FDA endorsement and modified risk versus exposure messaging in IQOS ads: a randomised factorial experiment among US and Israeli adults. Tob Control 2024; 33: e69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang B, Massey ZB, Popova L. Effects of modified risk tobacco product claims on consumer comprehension and risk perceptions of IQOS. Tob Control 2022; 31: e41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McKelvey K, Baiocchi M, Halpern-Felsher B. PMI’s heated tobacco products marketing claims of reduced risk and reduced exposure may entice youth to try and continue using these products. Tob Control 2020; 29: e18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Kislev S et al. Tobacco legislation reform and industry response in Israel. Tob Control 2021; 30: e62–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tabuchi T, Kiyohara K, Hoshino T et al. Awareness and use of electronic cigarettes and heat-not-burn tobacco products in Japan. Addiction 2016; 111: 706–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caputi TL. Heat-not-burn tobacco products are about to reach their boiling point. Tob Control 2017; 26: 609–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hair EC, Bennett M, Sheen E et al. Examining perceptions about IQOS heated tobacco product: consumer studies in Japan and Switzerland. Tob Control 2018; 27: s70–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Philip Morris International . Philip Morris International Announces U.S. Food and Drug Administration Authorization for Sale of IQOS in the United States. Available at: https://www.pmi.com/media-center/press-releases/press-details/?newsId=15596. Accessed: 16 Oct 2020.

- 36. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA permits sale of IQOS Tobacco Heating System through premarket tobacco product application pathway. 2019.

- 37. US Food and Drug Administration . Marketing Order, FDA Submission Tracking Numbers (STNs): PM0000424-PM0000426, PM0000479, IQOS System Holder and Charger and Marlboro Heatsticks. 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/premarket-tobacco-product-applications/premarket-tobacco-product-marketing-orders. Accessed: 6 Aug 2020.

- 38. Nyman AL, Weaver SR, Popova L et al. Awareness and use of heated tobacco products among US adults, 2016–2017. Tob Control 2018; 27: s55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berg CJ, Romm KF, Patterson B et al. Heated tobacco product awareness, use, and perceptions in a sample of young adults in the U.S. Nicotine Tob Res 2021; 23: 1967–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu X, Lugo A, Spizzichino L et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: concerns from the Italian experience. Tob Control 2019; 28: 113–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim J, Yu H, Lee S et al. Awareness, experience and prevalence of heated tobacco product, IQOS, among young Korean adults. Tob Control 2018; 27: s74–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids . IQOS Marketing Examples: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. 2018. Available at: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/content/press_office/2018/2018_03_28_IQOS_marketing_examples.pdf. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 43. Czoli C, White C, Reid J et al. Awareness and interest in IQOS heated tobacco products among youth in Canada, England and the USA. Tob Control 2020; 29: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Khayat A, Berg CJ, Levine H et al. PMI’s IQOS and cigarette ads in Israeli media: a content analysis across regulatory periods and target population subgroups. Tob Control 2024; 33: e54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bar-Zeev Y, Berg CJ, Abroms LC et al. Assessment of IQOS marketing strategies at points-of-sale in Israel at a time of regulatory transition. Nicotine Tob Res 2022; 24: 100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khayat A, Levine H, Berg CJ et al. IQOS and cigarette advertising across regulatory periods and population groups in Israel: a longitudinal analysis. Tob Control 2024; 33: e3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013; 48: 2134–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Jamal A et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023; 72: 475–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gallus S, Lugo A, Liu X et al. Use and awareness of heated tobacco products in Europe. J Epidemiol 2022; 32: 139–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miller CR, Sutanto E, Smith DM et al. Characterizing heated tobacco product use among adult cigarette smokers and nicotine vaping product users in the 2018 ITC four country smoking & vaping survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2021; 24: 493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project . International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project: 4-Country Smoking & Vaping W3. 2020. Available at: https://itcproject.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/documents/ITC_4CV3_Recontact-Replenishment_web_Eng_16Sep2020_1016.pdf. Accessed: 1 May 2024.

- 52. Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group . Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS): Sample Design Manual. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee YO, Kim AE. ‘Vape shops’ and ‘E-Cigarette lounges’ open across the USA to promote ENDS. Tob Control 2015; 24: 410–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control 2012; 21: 147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Znyk M, Jurewicz J, Kaleta D. Exposure to heated tobacco products and adverse health effects, a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Berg CJ, Abroms LC, Levine H et al. IQOS marketing in the US: the need to study the impact of FDA modified exposure authorization, marketing distribution channels, and potential targeting of consumers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 10551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Popova L, Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Light and mild redux: heated tobacco products’ reduced exposure claims are likely to be misunderstood as reduced risk claims. Tob Control 2018; 27: s87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lempert LK, Glantz S. Packaging colour research by tobacco companies: the pack as a product characteristic. Tob Control 2017; 26: 307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bansal-Travers M, O’Connor R, Fix BV et al. What do cigarette pack colors communicate to smokers in the US? Am J Prev Med 2011; 40: 683–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2011; 20: ii20–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P et al. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the US. Am J Prev Med 2011; 40: 674–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. World Health Organization . STEPwise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance (STEPS). 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/steps. Accessed: 1 Feb 2024.

- 64. Hays DG, McKibben WB. Promoting rigorous research: generalizability and qualitative research. J Counseling Dev 2021; 99: 178–88. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request but are not publicly available for ethical reasons.