Cerebral palsy is a physical impairment that affects the development of movement. Impairment can vary considerably and no two people with cerebral palsy are affected in exactly the same way. The problems that children and adults with cerebral palsy face, including discrimination, are often similar

Cerebral palsy is the most common physical disability in childhood. Children with cerebral palsy usually survive into adulthood, and the condition is often poorly understood in adulthood. Recognising and managing cerebral palsy's many important comorbidities is as important as treating the motor disabilities. Recent advances in the understanding of cerebral palsy include new ways of thinking about disability; recognition of causal pathways; and improvements in measurement, classification, and prognostication. Challenges include ensuring the wellbeing of families as well as children; tackling the issues faced lifelong by people with cerebral palsy; and the continuing need for primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of the effects of cerebral palsy on people's lives.

Summary points

Cerebral palsies are neurodevelopmental conditions, are the commonest “physical” disabilities in childhood, and severely affect a child's development

Comorbidities include epilepsy, learning difficulties, behavioural challenges, and sensory impairments and are at least as important as the motor disabilities

Advances in research are increasing our understanding of causal pathways, opportunities for primary prevention, and the value of specific intervention strategies

Cerebral palsy cannot be cured, but a host of interventions can improve functional abilities, participation, and quality of life

These conditions need to be recognised as involving the whole family, and management should always occur in the context of family needs, values, and abilities

The needs of adults with cerebral palsy, who currently are underemployed and face major barriers in the community, must now be tackled

What is cerebral palsy?

Cerebral palsy is “an umbrella term covering a group of non-progressive, but often changing, motor impairment syndromes secondary to lesions or anomalies of the brain arising in the early stages of development.”1 A total of 2-2.5 of every 1000 live born children in the Western world have the condition2; incidence is higher in premature infants and in twin births.3,4 Some causal pathways have been described, which make it possible to prevent, for example, athetoid cerebral palsy due to kernicterus associated with Rh isoimmunisation, and potentially to eliminate cerebral palsy associated with maternal iodine deficiency.2,5 The common perception that perinatal asphyxia is an important cause of cerebral palsy almost certainly overstates the case6; occult infection or inflammation is increasing implicated.7 Often a cause cannot be found in the history of children with clear clinical evidence of cerebral palsy.

Many efforts are under way in the basic and clinical sciences to describe the cascades of pathophysiological events that cause neurological damage, particularly in compromised premature infants.8 As the mechanisms of injury to the developing central nervous system are better understood, neuroprotective agents are likely to play an increasing role in continuing efforts at primary prevention of cerebral palsy.

Clinical presentation

Cerebral palsy, except in its mildest forms, can be seen in the first 12 to 18 months of life. The condition presents when children fail to reach their motor milestones and when they show qualitative differences in motor development, such as asymmetric gross motor function or unusual muscle stiffness or floppiness. Cerebral palsy is usually characterised clinically by the parts of the body affected (box B1), although conventional terminology used to describe cerebral palsy is less precise or reliable than the terms imply. Descriptions of the predominant motor disorder refer to spastic, dystonic, athetotic, and ataxic features (box B2).9 Functional status can be categorised (with respect to gross motor activity) by using the five levels of the gross motor function classification system for cerebral palsy (box B3),10 a reliable and valid system with prognostic importance now available on the CanChild web page (box B4).11,12

Box 1.

Topography of cerebral palsy

- Hemiparesis (hemiplegia)—(predominantly) unilateral impairment of arm and leg on the same side

- Diplegia—motor impairment primarily of the legs (usually with some relatively limited involvement of arms)

- Triplegia—three limb involvement

- Quadriplegia (tetraplegia)—all four limbs, in fact the whole body, are functionally compromised

Box 2.

European classification of (motor impairment in) cerebral palsy9

Box 3.

Severity of cerebral palsy: gross motor function classification system (for children between 6 and 12 years)10

Box 4.

Website resources for parents and doctors

Developmental implications

Cerebral palsy is in many ways the prototype for developmental disabilities. By definition the problems stem from one of many impairments of the developing central nervous system.2 Cerebral palsy affects gross motor function to a varying extent. A child's resulting overall development, specifically in mobility and other aspects of development and learning, is compromised by relative deprivation of experience. Delayed or aberrant motor function affects the development of a child's capacity to explore actively and to learn about space, effort, independence, and the social consequences of moving, touching, and getting into mischief. Limits to a child's functioning can cause parents to perceive their child as damaged, impaired, or disabled (and therefore limited); parents may interact with their child differently than if the child had better function.

People with cerebral palsy are considerably more likely to have functional difficulties unrelated to movement but related to their central nervous system (including sensory, epileptic, learning, behavioural, and related developmental impairments).13 These impairments may begin early in life as difficulties in feeding, irritability, and disordered sleep patterns. These problems, when present, affect day to day life and can cause considerable distress to children, parents, and carers. These problems are not inevitable or intractable, but it is essential to ask about, identify, and intervene before problems become entrenched.

WILL AND DENI MCINTYRE/SPL

Children with chronic functional limitations have considerably more difficulties in the social and behavioural aspects of their lives than typical children.14 Intellectual and behavioural problems in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy reported by teachers in mainstream schools indicate that such children are at high risk of rejection by peers, lack of friends, and victimisation.15 It is essential to recognise the coexistence of physical functional and neurobehavioural disabilities in children with cerebral palsy and to provide integrated services to tackle these manifestations.16

Parents' first questions about cerebral palsy

From the outset parents want to know how “bad” the cerebral palsy is and whether their child will walk. These questions can be difficult to answer, particularly for healthcare professionals with limited experience of children with the condition. The literature on truth disclosure and communication with patients and families calls unequivocally for honesty, openness, communication with both parents together, and sensitivity to the individual needs of each family.17 A reliable and validated functional classification system for cerebral palsy9 that carries prognostic information has made it possible to provide evidence based answers to inform both parents and service providers (fig 1).12 In future this information may also be used to develop intervention programmes appropriate to a child's age and stage.

Figure 1.

Predicted average development of gross motor ability for each category of the gross motor function classification system (level I to level V). Dashed lines show the age in years at which children are expected to achieve 90% of their potential for motor development. A to D on the vertical axis identify four gross motor items, located where children are expected to have a 50% chance of successfully completing that item. A=therapist holds child sitting upright, child lifts head for 3 seconds; B=child maintains sitting, arms free, for 3 seconds; C=child walks forward 10 steps; D=child walks down 4 steps, alternating feet12

Modern goals: treatment and management

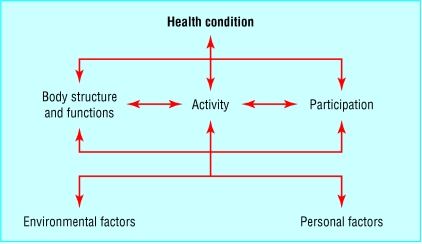

Cerebral palsy cannot be cured. The World Health Organization's model of health and disease focuses on function and is an important framework to guide modern thinking about treatment for children with cerebral palsy (fig 2).18 The goals of management should be to use appropriate combinations of interventions (including developmental, physical, medical, surgical, chemical, and technical modalities) to promote function, to prevent secondary impairments and, above all, to increase a child's developmental capabilities.

Figure 2.

World Health Organization model of the international classification of functioning, disability, and health

Many of the conventional approaches used in developmental treatment more or less target the primary impairments that underlie the functional challenges faced by children with cerebral palsy. With increased emphasis on promoting function, two important issues should be considered. Firstly, there is a need to move beyond efforts to promote normal function in children with cerebral palsy (often an illusory goal) toward the achievement of functional abilities that facilitate independence. Secondly, the liberal use of adaptive equipment—for example, powered mobility or walkers—may support early development of capacities such as independent ability to move about with the important effect of improving overall development.

The common concern that making things too easy for children will inhibit normal function is unfounded; there is strong evidence that, for example, the provision of powered mobility to children with disabilities as young as 36 months can have pervasive impacts on social, language, and play skills as well as increase efforts to try independent movement.19 A similar argument can be made for the early introduction of augmentative communication systems for children with communicative difficulties—for example, sign language, and picture boards—which make communication possible and often help to promote the development of oral language. Parents are often initially reluctant to accept augmentative interventions, preferring to work toward normal function. Introducing new parents to others who have chosen to provide devices to their children can be helpful to let the experienced parents discuss how they made the decisions about the use of equipment and sharing their perceptions about the value (or not) of this special equipment.

The role of the family and how doctors can help

Modern services for child health are increasingly being offered within a framework that espouses family centred service.20 Parents and providers work together in a partnership quite different from the traditional management of a child's rehabilitation programme directed by a doctor. These new relationships are predicated on mutual respect, empowered parents, and appropriate sharing of information with which decisions can be made. Parents' experiences of family centred service and their satisfaction with services, as well as the stress they experience in their dealings with their child's treatment centre, are strongly correlated.21 There is also a measurable link between family centred service and parents' mental health.22

Parental values and goals can form an important component of the management programme that is created for a child. Goal setting should be a joint venture between parents (and older children) and healthcare providers. This approach has recently been shown to lead to more effective outcomes and to be more efficient in terms of the amount of intervention by professionals.23 From a developmental perspective this finding makes sense—parents and especially children are more likely to follow through with recommendations for treatment that tackle their goals and needs. (Some parents may wish professionals to make decisions for them; an active choice by parents to be advised what to do is still a family centred approach to delivering services.)

Cerebral palsy is a long term condition; parents (and people with cerebral palsy) will have questions and issues to resolve throughout their lives. Continuity in the relationship between parents and trusted counsellors is important; professionals such as family doctors and therapists are people who will listen, support, advocate, and be there when challenges arise. Challenges are especially likely at times of transition in the life of the child and family, such as at the time of diagnosis, starting primary or secondary school, leaving school, and when entry to the broader community is being considered. Continuous and consistent service is valued by parents.24

New developments in treatment

The array of biomedical and surgical innovations for the treatment of cerebral palsy is ever expanding, much of it aimed at the reduction of what can at times be disabling spasticity. These include the use of botulinum toxin for temporary relief of spasticity,25 selective dorsal rhizotomy for more permanent relief,26 and intrathecal baclofen as a titratable antispasticity agent.27 Recent work to promote strength training for people with cerebral palsy may provide important new avenues to improve function.28

At the same time as innovative treatments are being developed, complementary treatments have emerged.29 These approaches range from apparently sensible but untested methods of teaching, training, or treating children (such as conductive education based on educational principles, which is as effective as, but not better than, conventional approaches),30 to interventions based on anecdotal evidence and testimonials but usually no credible research. New treatments are greeted with an expectation of impact that rarely happens. One such innovation which has attracted a lot of attention in the past few years is the use of hyperbaric oxygen, an approach that has been clearly shown in a well designed randomised clinical trial to provide no benefit.31 Other essentially untested ideas include subthreshold electrical stimulation of muscles, intensive passive muscle manipulation (patterning), and the use of an astronaut suit to promote independent mobility. In each case the claims about the effectiveness of the treatments are unsupported by solid clinical trial based research.32

Doctors are often called on to advise about treatment approaches with which they are unfamiliar. Specialty organisations such as Scope in the United Kingdom and UCPA in the United States, and research groups such CanChild in Canada have well developed websites (box B4). These websites may provide information on topics that are not available in published literature about complementary treatment (because so little research on these modalities has been undertaken).

The future for research

Considerable research efforts are under way toward the primary prevention of brain injury in infants at high risk who are exposed to perinatal abuse. Although most of this work is still at the development stage, clinical trials will soon be under way to evaluate a host of strategies.

An important and growing concern is the unmet needs of young adults with cerebral palsy. Community services for adults are often ill prepared to understand, let alone to meet, the needs of today's young people with disabilities, who have generally grown up at home and in the community and have been more integrated than children with cerebral palsy in any previous generation.33 The challenge to be addressed by service providers, educators, prospective employers, policy makers, and others is to begin to anticipate and plan appropriately for the full incorporation of adults with cerebral palsy into the life of their community, a goal fully consistent with the World Health Organization's focus on participation. This challenge is one that must be addressed by the whole community, and should involve the imagination and political will of professionals and families from all areas of society. To do less would be to marginalise young people with cerebral palsy and to squander the developmental and functional gains they have made in their developing years.

Acknowledgments

I thank Doreen Bartlett, Robert Palisano, Richard Stevenson, and Martin Bax. I also thank colleagues at CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mutch LW, Alberman E, Hagberg B, Kodama K, Velickovic MV. Cerebral palsy epidemiology: where are we now and where are we going? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley FJ, Blair E, Alberman E. Cerebral palsies: epidemiology and causal pathways. London: Mac Keith; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escobar GJ, Littenberg B, Petitti DB. Outcome among surviving very low birthweight infants: a meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:204–211. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Childhood neurological disorders in twins. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1995;9:135–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1995.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hetzel BS. Iodine and neuropsychological development. J Nutr. 2000;130(suppl 2):S493–S495. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.493S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson KB. What proportion of cerebral palsy is related to birth asphyxia? J Pediatr. 1988;112:572–574. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson KB, Willoughby RE. Infection, inflammation, and the risk of cerebral palsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:133–139. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Plessis AJ, Volpe JJ. Perinatal brain injury in the preterm and term newborn. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:151–157. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cans C. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:816–824. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Russell DJ, Wood EP, Galuppi BE. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood EP, Rosenbaum PL. The gross motor function classification system for cerebral palsy: a study of reliability and stability over time. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:292–296. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum PL, Walter SD, Hanna SE, Palisano RJ, Russell DJ, Raina R, et al. Prognosis for gross motor function in cerebral palsy: creation of motor development curves. JAMA. 2002;288:1357–1363. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.11.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennes J, Rosenbaum P, Hanna SE, Walter S, Russell D, Raina P, et al. Health status of school-aged children with cerebral palsy: information from a population-based sample. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:240–247. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadman D, Boyle M, Szatmari P, Offord DR. Chronic illness, disability, and mental and social well-being: findings of the Ontario child health study. Pediatrics. 1987;79:805–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yude C, Goodman R. Peer problems of 9-11-year-old children with hemiplegia in mainstream school: can these be predicted? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:4–8. doi: 10.1017/s001216229900002x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bax M. Joining the mainstream. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:3. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham CC, Morgan PA, McGucken RB. Down's syndrome: is dissatisfaction with disclosure of diagnosis inevitable? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1984;26:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1984.tb04403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. International classification of impairment, activity, and participation. Geneva: WHO; 2001. . (ICIDH-2.) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler C. Augmentative mobility: why do it? In: KM Jaffe, ed. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 1991;2:801–816. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbaum P, King S, Law M, King G, Evans J. Family-centred services: a conceptual framework and research review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1998;18:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.King S, Rosenbaum P, King G. Parents' perceptions of care-giving: development and validation of a process measure. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1996;38:757–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1996.tb15110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King G, King S, Rosenbaum P, Goffin R. Family-centred caregiving and well-being of parents of children with disabilities: linking process with outcome. J Ped Psychol. 1999;24:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ketelaar M, Vermeer A, Hart H, van Petegem-van Beek E, Helders PJ. Effects of a functional therapy program on motor abilities of children with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1534–1545. doi: 10.1093/ptj/81.9.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breslau N, Mortimer EA. Seeing the same doctor: determinants of satisfaction with specialty care for disabled children. Med Care. 1981;19:741–757. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar TS. Clinical utility of botulinum toxin in the treatment of cerebral palsy: a comprehensive review. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:37–46. doi: 10.1177/088307380101600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaughlin J, Bjornson K, Temkin N, Steinbok P, Wright V, Reiner A, et al. Selective dorsal rhizotomy: meta-analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:17–25. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler C, Campbell S. Evidence of the effects of intrathecal baclofen for spastic and dystonic cerebral palsy. AACPDM treatment outcomes committee review panel. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:634–645. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200001183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodd KJ, Taylor NF, Damiano DL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of strength-training programs for people with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1157–1164. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.34286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenbaum P, Stewart D. Alternative and complementary therapies for children and youth with disabilities. Inf Young Child. 2002;15:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddihough DS, King J, Coleman G, Catanese T. Efficacy of programmes based on conductive education for young children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb12345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collet JP, Vanasse M, Marois P, Amar M, Goldberg J, Lambert J, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for children with cerebral palsy: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2001;357:582–586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04054-x. . (HBO-CP research group.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosenbaum PL. Controversial treatment of spasticity: exploring alternative therapies for motor function in children with cerebral palsy. J Ped Neurol 2003 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Cathels BA, Reddihough DS. The health care of young adults with cerebral palsy. Med J Aust. 1993;159:444–446. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]