Abstract

Background and Objectives

The purpose of this study was to investigate individuals residing in senior living communities (SLCs) amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. One reason those living in SLCs often choose these communities is to have a readily available social network. Necessary social distancing disrupted this socialization, thus, possibly increasing perceptions of loneliness in residents of SLCs. This study examined relationships among loneliness, perceived provider communication about the pandemic and related restrictions, as well as individual characteristics.

Research Design and Methods

In December 2020, a survey was administered to older adults residing in a network of SLCs in Nebraska. Utilizing data from 657 residents aged 60 and older, ordinary least squares regression models were used to examine associations between 2 distinct measures of perceived provider communication and feelings of loneliness during the pandemic. The analysis also considered whether these associations varied as a function of education.

Results

The respondents were, on average, 84 years of age, primarily female (72%), and living independently (87%) in the SLC. The linear regression results revealed that 53% of respondents were very lonely during the pandemic. However, provider communication that was rated as helpful to residents’ understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with lower perceived loneliness. There was not a similar association for provider communication regarding services and amenities, and the association was not present for those with the highest level of education.

Discussion and Implications

Provider communication in times of disruption from normal activities, such as with the COVID-19 pandemic, is important to perceptions of loneliness among those living in SLCs, particularly for those with lower educational attainment. SLCs are communities that individuals select to reside in, and through communication, providers may have the opportunity to positively affect resident experiences, especially in times of stress.

Keywords: Education, Global pandemic, Senior housing

Translational Significance: Although senior living communities (SLCs) offer residents opportunities for engagement and other social interaction, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to major disruptions in normal activities. This research investigated the association between perceived SLC communication and residents’ loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings indicate that favorable perceptions of SLC communication during the pandemic were associated with lower levels of loneliness, particularly among less-educated residents. This research suggests a protective role of perceived communication and encourages providers to prioritize their communication efforts.

The psychosocial effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have been frequently investigated among community-dwelling residents (Birditt et al., 2021; Ernst et al., 2022; Scott et al., 2021), and to a lesser extent, among persons living in nursing home settings (Verbiest et al., 2022). By contrast, there is scant research on congregate spaces like senior living communities (SLCs). The COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity to examine the effects of sheltering in place among persons who live in a SLC environment that is, by design, intended to reduce social isolation and have a protective effect on loneliness.

For people choosing to live in a SLC, there are several reasons why they make this their home. For some, it is a matter of convenience and access to comforts, whereas for others it is about having the opportunity to form and develop relationships with those of similar ages (Chaulagain et al., 2021). In addition, declining health and readily available services also act as motivating factors for many older adults (Ewen & Chahal, 2013). Indeed, SLCs offer residents a variety of options, including independent living (for those not needing help with the basics of living) and assisted living (for persons in need of assistance with medication management and other activities of daily living), in addition to units for those requiring memory care or support (Koss & Ekerdt, 2017). Regardless of the level of care, people move out of their nonage segregated homes in the community to a more restricted environment that has oversight over their well-being. In this role, the SLC can impose restrictions on residents during times of crisis to ensure their safety and welfare, especially during a global pandemic like COVID-19.

The expectations of sheltering in place (i.e., remaining in one’s apartment and limiting time in shared spaces), and quarantining for a period of days when leaving the community, along with the consequences of exposure to persons with COVID-19, present a similar scenario to that of the nursing home setting during the pandemic. Like their more infirm counterparts, persons living in SLCs in the United States may be subjected to the same restrictions as persons living in more medically oriented facilities such as nursing homes and extended stay facilities (Zimmerman et al., 2020). Thus, the effects of the pandemic and how it affects the lives of persons electing to move into a SLC for companionship warrant further exploration, particularly as it relates to feelings of loneliness.

Background

Loneliness is a threat to the health and well-being of people, especially as they age. Some studies suggest loneliness can be as impactful on health as excessive drinking and smoking (Berg-Weger & Morley, 2020). In combination with social isolation, the effects of loneliness on the mental and physical health of older adults are well represented in the literature, with a focus on aging adults living in the community (Donovan & Blazer, 2020). For those living in more age-segregated communities, however, the prevalence and impact of loneliness have been less studied, although there is some evidence to suggest that loneliness is higher among female residents of SLCs compared to their community-dwelling counterparts (Lahti et al., 2021).

One notable exception to this is a pre-COVID-19 study of three senior housing complexes. Taylor et al. (2018) found that loneliness was evident in 69% of the sample, with 26% of residents classified as “severely lonely.” Although social isolation was less prevalent, respondents were still lonely despite being with others. In another prepandemic study, Paredes et al. (2021) conducted a qualitative study with 30 residents of a large independent living community. Loneliness was evident in this group as well, with 63% of participants described as “moderate,”—and another 22% as “high”—on loneliness (Paredes et al., 2021). More recent research suggests that loneliness increased among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (Krendl & Perry, 2021); however, only a small handful of studies have examined loneliness in the context of congregate living spaces during the pandemic (Baek et al., 2024; Weeks et al., 2023). Although on the surface SLCs may be viewed as an antidote to loneliness, moving to a SLC may not be a cure-all to loneliness.

Beyond the threat of loneliness, older adults may also be isolated from information that can contribute to their overall health and well-being (Walkner et al., 2018). The role of professionals in disseminating information about current issues is an important part of the communication process for those living in the community (Walkner et al., 2018) as well as in more restricted settings (Lagacé et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2018). For instance, in a qualitative study of aging adults who transitioned from a hospital setting to a senior residence in Canada, limited communication from health care providers contributed to greater worries among older adults (Lagacé et al., 2021). In an effort to promote improved well-being, Lagacé et al. (2021) emphasized the need for better communication between older adults and their providers. Other researchers have found similar benefits to communication, including during stressful times such as returning home from an acute care setting (Mitchell et al., 2018).

In the midst of a global pandemic, receiving supportive communication is similarly important to the well-being of older adults (Finset et al., 2020). In the context of the present study, the perceived support of SLCs may be associated with less loneliness among senior living residents. Prior research on loneliness experienced during the pandemic has found evidence of a protective effect of social support, albeit among community-dwelling older adults (Bu et al., 2020; Lara et al., 2023). Similar to the benefits of perceived community support to loneliness (Teater et al., 2021), residents’ perceptions of communication in their SLC may act as a resource. For instance, providers not only had the opportunity to share information on more practical matters during the pandemic, but more broadly, pandemic-related communication may have contributed to a greater sense of togetherness (Luchetti et al., 2020).

Drawing on Ross and Mirowsky’s (2006) resource substitution theory, however, the benefits of perceived SLC communication may not be equally distributed. The theory posits that one resource may be used in place of another; thus, when individuals are low on one resource, another available resource gains greater importance (Ross & Mirowsky, 2006). In examining the association between perceived SLC communication and loneliness, residents with less education may have benefited from SLC communication to a greater extent. We focus on education as a moderator, as past studies have shown education to be protective against loneliness (e.g., Hutten et al., 2022; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2001). Moreover, education is a resource obtained early in the life course. In later life, it is not sensitive to fluctuations, including those brought on by the pandemic, and can be drawn upon at any time (Elo, 2009).

Education may also have played a distinct role amid the pandemic. For instance, higher education is associated with internet use, including the adoption of new technologies during the pandemic, which provides additional avenues for information and social connection (Chang, 2015; Li et al., 2021). Those with higher levels of education are also found to have larger social networks (Hawkley et al., 2008). Taken together, this may have necessitated less reliance on SLCs for support during the pandemic. The pandemic also led SLCs to enact new safety precautions, including visitor restrictions, intended to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Less understanding of these restrictions and the reasons for them could serve to exacerbate the loneliness brought on by the pandemic. Thus, when education is low, individuals may rely more on SLC communication, and the association between perceived provider communication and loneliness may be stronger. In this sense, perceptions of provider communication may effectively serve to level the playing field and compensate for lower levels of education during a global pandemic.

The purpose of this study was to examine the lives of older adults residing in SLCs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing on data from a network of SLCs in the state of Nebraska, we posed the following research questions: (1) Is perceived provider communication during the COVID-19 pandemic associated with feelings of loneliness among senior living residents? (2) What is the role of education in this association? In addressing these questions, we utilized two distinct measures of SLC-resident communication—one related to residents’ perceptions of the extent to which the SLC contributed to their understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic and another focused on more practical matters related to accessing services and amenities during the pandemic. Whereas prior aging research has predominately focused on loneliness among community-dwelling adults, this research aims to increase understanding of loneliness in SLCs as well as contribute to accumulating research on the psychosocial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data and Methods

Sample

This study draws on data collected from a self-administered survey of older adults residing in a network of SLCs in the state of Nebraska. The purpose of the survey was to increase understanding of the experiences of older adults living in SLCs during the COVID-19 pandemic and included topics related to perceived life changes due to the pandemic, psychosocial well-being, health care utilization, and technology. In December 2020, prior to the availability of the COVID-19 vaccine, we distributed surveys to all individuals currently living on-site in either independent living or assisted living at each of the SLCs; those residing in memory care units were excluded from the study. We obtained 733 completed surveys for an estimated response rate of 60%. We omitted one respondent who reported being younger than 60 years of age due to the age eligibility requirement of the SLCs. The analytic sample was further limited to those with valid information on all study variables, resulting in a final sample of 657 respondents.

Measurement

Loneliness

The dependent variable is based on the three-item loneliness scale (Hughes et al., 2004). The three-item scale is a validated measure of loneliness and has been used in prior studies of senior housing (see Taylor et al., 2018). Specifically, the residents were asked to respond to the following three questions: (1) “How often do you feel that you lack companionship?,” (2) “How often do you feel left out?,” and (3) “How often do you feel isolated from others?” Each item included response categories ranging from 1 “hardly ever or never” to 3 “often.” We created an index of loneliness by taking the row mean of the three items (α = 0.79).

Perceived SLC communication

We used two separate measures to capture perceived provider communication in SLCs during the pandemic. Developed in collaboration with the SLC leadership team, we asked the extent to which respondents agreed or disagreed with the following two statements: (1) “[SLC] has been helpful to my understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic” and (2) “[SLC] has clearly communicated the phasing of services and amenities during the COVID-19 pandemic.” For each item, response categories ranged from 1 “strongly disagree” to 6 “strongly agree.”

Personal and housing characteristics

We also considered additional personal and housing characteristics. We measured age in chronological years. Female is a binary variable coded 1 for female (0 = male). Live alone is a binary variable coded 1 for an affirmative response and 0, otherwise. Independent living is a binary variable coded 1 for independent living and 0 for assisted living. Education is an ordinal variable coded into the following four categories: (1) high school diploma or less, (2) some college, (3) 4-year college degree, and (4) postgraduate degree. We combined less than high school and high school/GED due to the small number of respondents with less than a high school education (n = 16); however, conclusions were robust to alternative coding strategies. We measured affordable housing using a binary variable coded 1 for those living in subsidized senior housing and 0, otherwise. Financial strain is an ordinal variable derived from the question, “Which of the following best describes your ability to get along on your income?” The response categories ranged from 1 “always have money left over” to 4 “can’t make ends meet.” We also draw on a global measure of perceived health, with categories ranging from 1 “poor” to 5 “excellent.”

Analytic Plan

To investigate the association between perceived provider communication and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the potential moderating effect of education, Table 2 presents results from ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models. Based on prior research, our models adjust for documented predictors of loneliness, including confounders that may be associated with both perceived provider communication and loneliness. In particular, we account for age, female, living alone, independent living, education, affordable housing, financial strain, and self-rated health. Model 1 includes these personal and housing characteristics. Model 2 adds two measures of perceived SLC communication during the pandemic—(1) perceptions of help in understanding the pandemic and (2) perceived communication related to the phasing of services and amenities—to examine the extent to which perceived SLC communication is associated with loneliness after accounting for personal and housing characteristics. The final two models incorporate interaction terms between each of the SLC communication measures and education to test the potential moderating influence of education on the association between SLC communication and loneliness. Model 3 includes the interaction term for perceived help in understanding the pandemic and education, whereas Model 4 provides a separate test of the interaction between perceived communication related to services and amenities and education.

Table 2.

OLS Regression of Loneliness on Perceived SLC Communication During the COVID-19 Pandemic (N = 657)

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding the pandemic | −0.077** | −0.164*** | −0.076** | |

| (0.025) | (0.047) | (0.025) | ||

| Access to services and amenities | 0.034 | 0.034 | −0.038 | |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.050) | ||

| Understanding the pandemic × Education | 0.034* | |||

| (0.016) | ||||

| Access to services and amenities × Education | 0.028 | |||

| (0.017) | ||||

| Age | −0.008* | −0.008** | −0.008** | −0.008** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Female | 0.058 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| (0.051) | (0.051) | (0.051) | (0.051) | |

| Live alone | 0.337*** | 0.335*** | 0.330*** | 0.331*** |

| (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.050) | |

| Independent living | −0.103 | −0.104 | −0.097 | −0.102 |

| (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | |

| Education | −0.024 | −0.030 | −0.201* | −0.181* |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.080) | (0.092) | |

| Affordable housing | −0.024 | −0.014 | −0.006 | −0.008 |

| (0.067) | (0.066) | (0.066) | (0.066) | |

| Financial strain | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| Self-rated health | −0.094*** | −0.090*** | −0.091*** | −0.092*** |

| (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| Constant | 2.744*** | 2.956*** | 3.394*** | 3.352*** |

| (0.327) | (0.340) | (0.393) | (0.413) | |

| R 2 | 0.131 | 0.146 | 0.153 | 0.150 |

Notes: Unstandardized regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .05;

** p < .01;

*** p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

There was approximately 10% missing data in total, with less than 5% missing on individual study variables. The highest amount of missing data was found with financial strain (4%). Due to the small amount of item-missing data and results from Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test (Li, 2013), which indicated that the MCAR assumption had not been violated, list-wise deletion was used in the analysis. In sensitivity analyses, we performed multiple imputations with chained equations (imputations = 20) and the conclusions were the same.

Results

Means and standard deviations of the study variables are shown in Table 1. The mean age of respondents was 84, with a range of 60–100 years of age. The majority of the sample was female (72%). Most respondents reported living alone (66%) and in independent living (87%). The average respondent obtained a college education. Few respondents resided in affordable housing (18%) and financial strain was relatively low. In addition, respondents reported being in “good” to “very good” perceived health on average. Loneliness was moderate, with the mean response close to “some of the time.” Using the coding scheme employed by Taylor et al. (2018), we found that the majority of respondents (53%) were very lonely. Only 13% of respondents scored low on loneliness, while another 34% of respondents were moderately lonely. The average respondent had a generally favorable opinion of their provider’s communication during the pandemic, with the mean score on helpfulness in understanding the pandemic equal to 4.956 or between “slightly agree” and “somewhat agree.” Similarly, respondents somewhat to strongly agreed that their provider had clearly explained the phasing of services and amenities during the pandemic (mean = 5.311).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables (N = 657)

| Variables | Range | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||

| Loneliness | 1–3 | 1.874 | 0.576 |

| Independent variables | |||

| Perceived SLC communication | |||

| Understanding the pandemic | 1–6 | 4.956 | 1.279 |

| Access to services and amenities | 1–6 | 5.311 | 1.215 |

| Personal and housing characteristics | |||

| Age | 60–100 | 84.143 | 7.222 |

| Female | 0,1 | 0.721 | |

| Live alone | 0,1 | 0.658 | |

| Independent living | 0,1 | 0.866 | |

| Education | 1–4 | 2.438 | 1.117 |

| Affordable housing | 0,1 | 0.177 | |

| Financial strain | 1–4 | 1.753 | 0.767 |

| Self-rated health | 1–5 | 3.260 | 0.859 |

Note: SLC = Senior living communities.

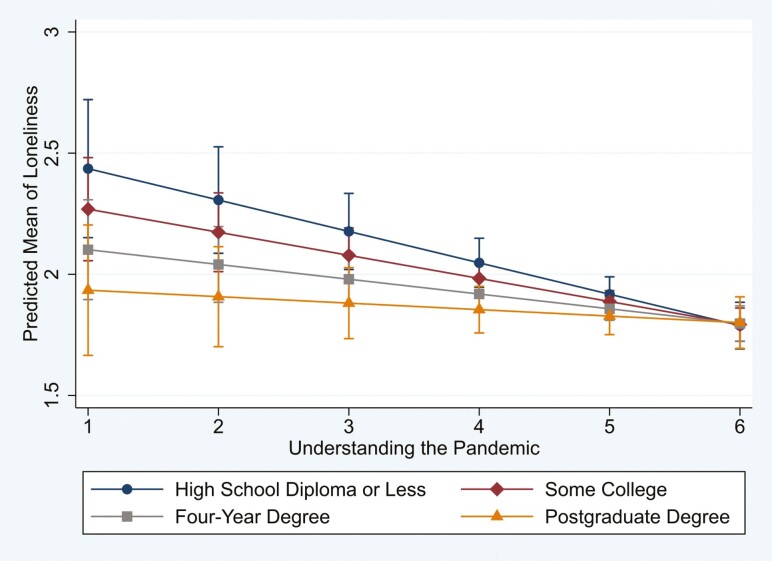

Table 2 shows unstandardized regression coefficients from four OLS regression models. Model 1 includes all personal and housing characteristics. The results reveal that older age and higher perceived health were both associated with lower scores on loneliness, whereas living alone was positively associated with loneliness. Model 2 adds variables for SLC communication and examines the association between perceptions of the provider’s pandemic-related communication and feelings of loneliness. Older adults who perceived that their SLC had been helpful to their understanding of the pandemic were significantly less lonely; however, communication related to the phasing of services and amenities was not significantly related to loneliness. Models 3 and 4 further add interaction terms and investigate the potential moderating effect of education on the linkage between perceived SLC communication and loneliness during the pandemic. The results from Model 3 indicate that less-educated older adults derived the greatest benefit from more favorable perceived communication about the pandemic. Specifically, those with lower levels of education reported feeling lonelier if they did not perceive that their SLC communicated in a way that helped them better understand the pandemic; there was no such association for those with the highest level of education. Notably, in Model 4, there was no similar moderating effect for SLC communication related to the phasing of services and amenities.

Figure 1 shows an illustration of the moderating effect of education on the SLC communication-loneliness association. As can be gleaned from the figure, older adults with high educational attainment reported relatively low levels of loneliness regardless of how they perceived their SLC’s helpfulness in understanding the pandemic. By contrast, those with low levels of education reported feeling less lonely with increasingly favorable ratings of their SLC’s helpfulness in understanding the pandemic. Moreover, those with the highest ratings of SLC communication were predicted to have similar scores on loneliness regardless of their level of education.

Figure 1.

Predictions of loneliness by perceived provider communication (understanding the pandemic) and education. Based on results from Model 3 in Table 2. 95% confidence intervals are displayed.

In supplementary analyses, we adjusted for race/ethnicity and marital status, but the conclusions were unchanged. Both covariates were omitted from results presented as the sample was predominately non-Hispanic White (97%) and being married was strongly correlated with living alone (Spearman’s ρ = –0.89).

Discussion

This study focused on the lives of older adults residing in SLCs, a setting designed to support people as they age, during the COVID-19 pandemic. It also investigated the relationship between perceived provider communication and feelings of loneliness among SLC residents. The results highlight the importance of perceptions of provider communication for loneliness during the pandemic and further reveal the role of education as a moderator. Specifically, provider communication that residents perceived as helpful to their understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with less loneliness, whereas communication focused on more practical matters related to accessing services and amenities had no significant association with loneliness. In addition, amid the uncertainty of the pandemic, the association between the perceived helpfulness of SLCs in understanding the pandemic and loneliness was stronger among residents with less education. This is consistent with resource substitution theory as well as previous research on the perceived benefits of communication during times of transition (Lagacé et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2018).

The findings from this study also shed light on the prevalence of loneliness in senior housing. We found that 53% of residents scored high on loneliness during the pandemic, whereas a prepandemic study of senior housing residents found this figure to be closer to 26% (Taylor et al., 2018). Unlike Taylor et al. (2018), our sample was not limited to subsidized housing and included residents in assisted living who experience more health problems, a risk factor for loneliness (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003). However, despite this difference, loneliness was relatively high in our sample even among those in independent living, with 51% of older adults in independent living rating their loneliness as high, compared to 65% of those in assisted living. This reflects some prior research, which has shown an increase in loneliness among older adults during the pandemic (Krendl & Perry, 2021).

In addition, it is notable that living alone, although in a community-dwelling, resulted in a positive association with loneliness. One possible reason for relocating to the SLC in the first place was to connect with others. The pandemic, however, changed older adults’ interactions with others, leading to confinement in their own apartments—thus, possibly exacerbating the potential for experiencing loneliness. In contrast, those who were older in age and rated their health as better were less likely to be lonely, on average, than their counterparts.

The potential benefits of communal living were seemingly lost during the pandemic, as the decision to shelter in place was based on a concern for the potential and quick spread of COVID-19 among residents. As Pirrie and Agarwal (2021) suggest, senior housing can be likened to a “vertical cruise ship” where the potential for mortality can be high due to the close proximity of living quarters. For this sample of older adults and the SLCs in which they resided, perceived SLC communication was found to be important, particularly for the less educated, as a more positive perception of provider communication was associated with less loneliness. The efforts of this group of SLCs may serve as a model for other providers serving older adults residing in independent and assisted living communities.

There are three limitations worth noting. First, respondents in this study were predominately White and residing in the state of Nebraska, thus constraining the generalizability of the results. Future research should examine a more diverse and representative sample. Second, the data were collected in December 2020. The close proximity to the holiday season, coupled with the directive to stay in one’s home, may have artificially inflated feelings of loneliness. Data collected at another point in time may have yielded different results. Last, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, we are unable to isolate the impact of the pandemic on feelings of loneliness. It is possible that many of these older adults were lonely prior to the onset of the pandemic. Still, this research paints a portrait of loneliness in an understudied population of SLC residents.

Concluding Remarks

Senior living communities (SLCs) remain a viable and attractive living option for older adults for the foreseeable future, particularly for those who live alone in the community and are seeking companionship in a SLC. Supporting older adults living in these communities, especially those with fewer resources, during times of stress is an important and strategic priority for providers. In their role as a surrogate system of support, the SLC provider has the opportunity to support people in the aging process.

Acknowledgments

We thank the residents and leadership team of the network of senior living communities for their participation in the survey.

Contributor Information

Lindsay R Wilkinson, Department of Gerontology, University of Nebraska at Omaha, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Julie L Masters, Department of Gerontology, University of Nebraska at Omaha, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Julie Blaskewicz Boron, Department of Gerontology, University of Nebraska at Omaha, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the BIG Ideas Pilot Grant Program through the University of Nebraska at Omaha and the Terry Haney Chair of Gerontology funding.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Data Availability

The study has not been preregistered. To maintain the confidentiality of the participating senior living communities, the data are not publicly available.

References

- Baek, J., Kim, B., Park, S., & Ryu, B. (2024). Loneliness among low-income older immigrants living in subsidized senior housing: Does perceived social cohesion matter? Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 67(1), 80–95. 10.1080/01634372.2023.2216741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Weger, M., & Morley, J. E. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for gerontological social work. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 24(5), 456–458. 10.1007/s12603-020-1366-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S., Turkelson, A., Fingerman, K. L., Polenick, C. A., & Oya, A. (2021). Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 205–216. 10.1093/geront/gnaa204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu, F., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113521. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J., McAllister, C., & McCaslin, R. (2015). Correlates of, and barriers to, internet use among older adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 58(1), 66–85. 10.1080/01634372.2014.913754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaulagain, S., Pizam, A., Wang, Y., Severt, D., & Oetjen, R. (2021). Factors affecting seniors’ decision to relocate to senior living communities. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102920. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, N. J., & Blazer, D. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a national academies report. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(12), 1233–1244. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo, I. T. (2009). Social class differentials in health and mortality: Patterns and explanations in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 553–572. 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, M., Niederer, D., Werner, A. M., Czaja, S. J., Mikton, C., Ong, A. D., Rosen, T., Brähler, E., & Beutel, M. E. (2022). Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 77(5), 660–677. 10.1037/amp0001005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewen, H. H., & Chahal, J. (2013). Influence of late life stressors on the decisions of older women to relocate into congregate senior housing. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 27(4), 392–408. 10.1080/02763893.2013.813428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finset, A., Bosworth, H., Butow, P., Gulbrandsen, P., Hulsman, R. L., Pieterse, A. H., Street, R., Tschoetschel, R., & van Weert, J. (2020). Effective health communication–A key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(5), 873–876. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), S375–S384. 10.1093/geronb/63.6.s375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutten, E., Jongen, E. M. M., Hajema, K., Ruiter, R. A. C., Hamers, F., & Bos, A. E. R. (2022). Risk factors of loneliness across the life span. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(5), 1482–1507. 10.1177/02654075211059193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss, C., & Ekerdt, D. J. (2017). Residential reasoning and the tug of the fourth age. The Gerontologist, 57(5), 921–929. 10.1093/geront/gnw010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krendl, A. C., & Perry, B. L. (2021). The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults’ social and mental well-being. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), e53–e58. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagacé, M., Fraser, S., Ranger, M.-C., Moorjani-Houle, D., & Ali, N. (2021). About me but without me? Older adult’s perspectives on interpersonal communication during care transitions from hospital to seniors’ residence. Journal of Aging Studies, 57, 100914. 10.1016/j.jaging.2021.100914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti, A.-M., Mikkola, T. M., Salonen, M., Wasenius, N., Sarvimäki, A., Eriksson, J. G., & von Bonsdorff, M. B. (2021). Mental, physical and social functioning in independently living senior house residents and community-dwelling older adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12299. 10.3390/ijerph182312299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara, E., Matovic, S., Vasiliadis, H.-M., Grenier, S., Berbiche, D., de la Torre-Luque, A., & Gouin, J.-P. (2023). Correlates and trajectories of loneliness among community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Canadian longitudinal study. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 115, 105133. 10.1016/j.archger.2023.105133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. (2013). Little’s test of missing completely at random. Stata Journal, 13(4), 795–809. 10.1177/1536867x1301300407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Ornstein, K. A., Li, Y., & Liu, B. (2021). Barriers to learning a new technology to go online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(11), 3051–3057. 10.1111/jgs.17433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti, M., Lee, J. H., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A., Strickhouser, J. E., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist, 75(7), 897–908. 10.1037/amp0000690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S. E., Laurens, V., Weigel, G. M., Hirschman, K. B., Scott, A. M., Nguyen, H. Q., Howard, J. M., Laird, L., Levine, C., Davis, T. C., Gass, B., Shaid, E., Li, J., Williams, M. V., & Jack, B. W. (2018). Care transitions from patient and caregiver perspectives. Annals of Family Medicine, 16(3), 225–231. 10.1370/afm.2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, A. M., Lee, E. E., Chik, L., Gupta, S., Palmer, B. W., Palinkas, L. A., Kim, H.-C., & Jeste, D. V. (2021). Qualitative study of loneliness in a senior housing community: The importance of wisdom and other coping strategies. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 559–566. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1699022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. 10.1207/s15324834basp2304_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Risk factors for loneliness in adulthood and old age—A meta-analysis. In Shohov S. P. (Ed.), Advances in Psychology Research (pp. 111–143). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Pirrie, M., & Agarwal, G. (2021). Older adults living in social housing in Canada: The next COVID-19 hotspot? Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112(1), 4–7. 10.17269/s41997-020-00462-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (2006). Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Social Science & Medicine, 63(5), 1400–1413. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. M., Yun, S. W., & Qualls, S. H. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and distress of community-dwelling older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 42(5), 998–1005. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H. O., Wang, Y., & Morrow-Howell, N. (2018). Loneliness in senior housing communities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(6), 623–639. 10.1080/01634372.2018.1478352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teater, B., Chonody, J. M., & Davis, N. (2021). Risk and protective factors of loneliness among older adults: The significance of social isolation and quality and type of contact. Social Work in Public Health, 36(2), 128–141. 10.1080/19371918.2020.1866140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbiest, M. E. A., Stoop, A., Scheffelaar, A., Janssen, M. M., van Boekel, L. C., & Luijkx, K. G. (2022). Health impact of the first and second wave of COVID-19 and related restrictive measures among nursing homes residents: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 921. 10.1186/s12913-022-08186-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkner, T. J., Weare, A. M., & Tully, M. (2018). “You get old. You get invisible”: Social isolation and the challenge of communicating with aging women. Journal of Women & Aging, 30(5), 399–416. 10.1080/08952841.2017.1304785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, L. E., Bigonnesse, C., Rupasinghe, V., Haché-Chiasson, A., Dupuis-Blanchard, S., Harman, K., McInnis-Perry, G., Paris, M., Puplampu, V., & Critchlow, M. (2023). The best place to be? Experiences of older adults living in Canadian cohousing communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Aging and Environment, 37(4), 421–441. 10.1080/26892618.2022.2106528 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, S., Sloane, P. D., Katz, P. R., Kunze, M., O’Neil, K., & Resnick, B. (2020). The need to include assisted living in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(5), 572–575. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study has not been preregistered. To maintain the confidentiality of the participating senior living communities, the data are not publicly available.