Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With an increasing number of people experiencing limitations in functioning during their life course, the need for comprehensive rehabilitation services is high. In 2017, the WHO Rehabilitation 2030 initiative noted that the need for the establishment and expansion of rehabilitation services is paramount in order to obtain well-being for the population and to ensure equal access to quality healthcare for all. The organization of rehabilitation services is however facing challenges especially in low-and middle-income countries with a very small proportion of people who require rehabilitation actually getting them. Various surveys conducted in low-and -middle income countries have revealed existing gaps between the need for rehabilitation services and the actual receipt of these services. This systematic review aimed to determine the barriers and facilitators for increasing accessibility to rehabilitation services in low- and middle-income countries. Recommendations for strengthening rehabilitation service organization are presented based on the available retrieved data.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

In this systematic review, an electronic search through three primary databases, including Medline (PubMed), Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) was conducted to identify original studies reporting on barriers and facilitators for rehabilitation service organization in low-and middle-income countries. Date of search: 25th April 2021 (PubMed), 3rd May 2021 (Scopus and Web of Science). All studies including barriers or/and facilitators for rehabilitation services in low- and middle income countries which were written in English were included in the review. The articles written in other languages and grey literature, were excluded from this review.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

Total of 42 articles were included from year 1989 to 2021. Numerous barriers were identified that related to education, resources, leadership, policy, technology and advanced treatment, community-based rehabilitation (CBR), social support, cultural influences, political issues, registries and standards of care. National health insurance including rehabilitation and funding from government and NGOs are some of the facilitators to strengthen rehabilitation service organization. Availability of CBR programs, academic rehabilitation training programs for allied health professionals, collaboration between Ministry of Heath (MOH) and Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) on telerehabilitation services are amongst other facilitators.

CONCLUSIONS

Recommendations for improving and expanding rehabilitation service organization include funding, training, education, and sharing of resources.

Key words: Health services research, Organizations, Health services accessibility, Rehabilitation, Developing countries

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 2.4 billion people globally are living with a health condition that could benefit from rehabilitation.1 This number is estimated to increase as people are living longer with an increase in non-communicable diseases such as stroke, cancer and diabetes. Rehabilitation is a set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions, in interaction with their environment.2 Access to rehabilitation services by persons with functional impairment at all levels of healthcare without barriers therefore reduces the negative impact of health conditions on the functioning of the individual. The WHO in the second objective of its Global Disability Action Plan aims to ‘Strengthen and extend rehabilitation, habilitation, assistive technology, assistance and support services, and community-based rehabilitation’ while Article 26 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (PWDs) encourages member states to plan and ensure the appropriate organization, strengthening and extension of rehabilitation services and programs within health, education, employment and social services sectors.3, 4

In 2017, the WHO Rehabilitation 2030 initiative noted that the need for the establishment and organization of rehabilitation services is paramount in order to promote well-being and ensure quality as well as equal access to healthcare for all.5 Rehabilitation service organization encompasses the provision of services at the different stages of injury or illness taking into account individual needs, the level of healthcare at which the individual is seeking care and the income level of the country while providing the opportunity for the individual to function optimally.

The organization of rehabilitation services is however facing challenges especially in low-to middle income countries with a very small proportion of people who require rehabilitation actually getting them. Various surveys conducted in low-to -middle income countries have revealed existing gaps between the need for rehabilitation services and the actual receipt of these services. In 2015, for example, Zambia published a national disability survey report which revealed that even though 47.6% of persons with disabilities needed medical rehabilitation, only 17.2% actually received it despite 42.5% that have been aware of such services.6 The 2018 Tonga National Disability survey report also showed that 28.9% of the population indicated that they needed rehabilitation services but only 20.3% received these services. In Afghanistan, 40.4% of persons who needed inpatient rehabilitation due to severe disabilities did not receive it.7, 8

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage on, reports of long term and post-COVID-19 complications with associated rehabilitation needs are numerous. The pandemic in itself has also largely disrupted the organization and provision of rehabilitation services in about 60-70% of countries globally.1

There is a need to identify the facilitators and barriers to rehabilitation service expansion especially in low-to-middle income countries where there are major challenges in order to inform adequate and appropriate strengthening of the health system for rehabilitation.

The International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM) is a non-governmental organization that engages with WHO through its Liaison Committee and its “Rehabilitation capacity building in LMIC” Working Group in a bid to fulfil its task has embarked on this systematic review to identify the facilitators and barriers to rehabilitation service expansion in low to middle income countries.

The aim of this review was to study the barriers which limit the accessibility to rehabilitation services in low-and middle-income countries; to determine the facilitators for increased accessibility to quality rehabilitation services in low-and middle-income countries; to provide recommendations to optimize quality rehabilitation services in low-and middle-income countries (LMIC).

Recommendations for improving and expanding rehabilitation service organization are presented based on the available retrieved data. Project discussions and communications occurred via email and Skype meetings and the group worked to put together the collective data and writing up this article.

Evidence acquisition

Identification and selection of studies

Search strategy

An electronic search was conducted to retrieve a pool of original studies reporting on barriers and facilitators for rehabilitation service expansion in low-and middle-income countries. This involved a systematic search in 3 primary databases, including Medline (PubMed), Scopus Web of Science (WOS) and Cochrane database. All studies including barriers or/and facilitators for rehabilitation services in low- and middle-income countries which were written in English were included in the review. The articles written in other languages and Grey literature were excluded from this review. Two reviewers retrieved the data and 3 reviewers analyzed the selected manuscripts independently.

Summary of the search strategy is presented in Supplementary Digital Material 1, Supplementary Table I.

Evidence synthesis

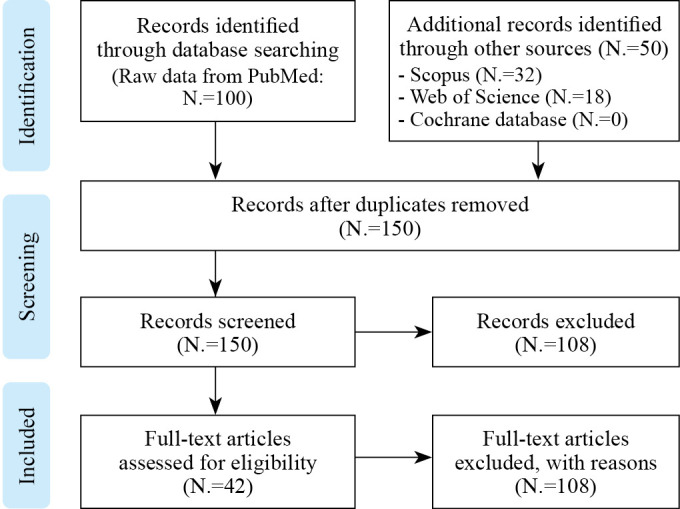

The searches produced 150 papers with full-text reports. The reviewers then selected 42 papers based on relevance and closeness to the objectives.10-51 Papers which did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from the review. The reasons for exclusion were study on general medical conditions such as leprosy, suicidal condition, acute orthopedic related conditions, cost-effectiveness of surgery, global health, psychological and social issues in back pain in low and middle income countries, autism spectrum, musculoskeletal issues and accessibility to surgery etc. (Figure 1).9

Figure 1.

—PRISMA flow chart of the study selection.9 [Adapted from Moher D, et al.].9

The papers discussed about various rehabilitation services organization addressing the type of organization (Government/University/Academia/ Private/Hybrid/NGOs /government-linked association/ Medical & Non-medical Associations/ Foundations), types of hospital (District, primary, secondary, tertiary, non-tertiary, military), type of support/funding received by organization, rehabilitation setting, facilitators and obstacles in provision of rehabilitation services.

Based on Supplementary Digital Material 2, SupplementaryTable II, several issues are highlighted as obstacles and facilitators in terms of rehabilitation service organization in LMIC.10-51

The selected 42 full-text papers consisted of 5 cross-sectional studies,10, 12, 20, 24, 25 10 qualitative studies,10, 13, 15, 18, 22, 42, 44, 47, 51 13 review papers,9, 11-15, 19, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 33, 35, 41, 43, 46, 48, 50of which five were systematic reviews,14, 21, 26, 32, 50 one organizational-based study,19 one consortium-based study,45 one clinical commentary,49 and 12 descriptive papers.27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36-41

The majority of papers looked at various aspects of rehabilitation service organization such as type of rehabilitation services availability, availability of formal discipline specific associations like the physiotherapy and occupational therapy associations, funding, stakeholder involvement and standards for rehabilitation services. Others explored patient experiences, rehabilitation workforce capacity, financial resources, leadership and policy, health insurance schemes, education opportunities as well as social and cultural issues influencing rehabilitation services provision.

Rehabilitation service organization

The studies reported various formal organizations10-26, 28, 36, 42-51 and informal interventions10, 24, 27, 31, 37, 40 through religious bodies and community volunteers involved in rehabilitation services. Whilst most of the institutions were based in government hospitals, a few were part of military hospitals.21, 24 Most did not have a complete team consisting of rehabilitation physicians and allied health personnel. Many of the countries reported that they did not have a regulatory body overseeing the various rehabilitation professions.

Most organizations highlighted the lack of structured healthcare services at the primary, secondary, tertiary hospitals as well as unavailability of core rehabilitation services like physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy services within the healthcare setting. Specialized services such as neurorehabilitation,22 prosthetics and orthotics,17, 18, 28, 42 telehealth services,26, 30 cardiac,38 aural,39 community based speech therapy,40 and assistive technology,34 were also reported. Financial barriers were reported in almost all the papers as a primary obstacle to forming and accessing these services. Supportive policies such as National Health Insurance Schemes (NHIS) and various educational programs have been noted to be helpful in the functioning of the service organizations.

Barriers

Finance

Lack of finance proved to be the single most common factor among most countries when establishing and running rehabilitation services organizations. Specific issues include high cost of services,38, 39, 50some requiring upfront costs,10 high cost of assistive devices,34 financial constraints and poor socioeconomic status,13, 16-19, 33, 37, 38, 42 cost of medications,12 lack of financing for rehabilitation services by government and organizations,11, 23, 24, 27, 44 lack of insurance,14, 25, 32, 43 high cost of home visits,22 local bureaucracy policies,28 high cost for implementation and sustainable telehealth,30 dependence on external sources to carry out activities,36 and poor financial management by organizations/ authorities.41

Facilities/logistics

Facility and logistic-related items have proven to be significant barriers in rehabilitation service organization specifically lack of transport,10, 12, 14, 19, 21-23, 25, 33, 34, 36, 43 distance,14, 21, 28, 33, 50 poor infrastructure and accessibility,11, 13, 19, 21, 24, 25, 31, 32, 36, 38, 48 lack of mobility aids,10 lack of rehab services,10, 15, 22, 48 low density of rehabilitation centers per inhabitant,23 disjointed services,19 long waiting time for prosthesis,28 lack of medical products and insufficient technology,11 including for prosthetic and orthotic fabrications,17, 22, 28 poor employment opportunities for physiotherapists,27 reliance on paper based system,29 and lack of communication and data integration between government agencies, NGO and CBR providers.29

Education

Continuous education is part of organizational development. However, the many barriers faced include lack of specialist education and professional development opportunities,10, 13, 15, 16, 32, 47 limited access to information and lack of research capacities,11, 21 limited education and info about rehabilitation,12, 21, 25, 41, 42 lack of knowledge of disability, related services and attitudinal factors,13, 14, 22, 24 illiteracy barriers to access care,17, 19 language barriers,17, 35 lack of research skills,21, 35, 45 acquisition of further academic qualification plays little or no role in career progression of physiotherapists in Nigerian clinics,20 lack of acceptance of telehealth among stakeholders,26 apprehension related to data privacy in telehealth,26 perception that physiotherapy and physical rehabilitation are not essential,27 lack of awareness for rehabilitation on the part of government, bureaucrats and health professionals,32, 38, 43 poor use of evidence-based practice,41poor knowledge and skills among community health workers,44 lack of discussion among clinicians,46 and no advisory group on disability at the Ministry of Health Level.48

Resources

Lack of resources proved to be amongst the most challenging obstacles faced. They include lack of mobility aids and appliances,10, 22, 32, 39 lack of access to therapy and rehabilitation services,10, 22, 23 low number and standard of skilled health-related professional,11-13, 15, 16, 21, 23, 24, 31, 38-40, 43, 48 difficulty attracting and retaining staff,16, 37 lack of medical facilities and products,11, 13, 21 lack of policies and standards,13, 15, 45 poor support from government health system,16 poor surgical techniques and rehabilitation treatment,17 neglected district hospital,19 lack of information resources,20, 33 low capacity for post treatment follow-up for patients,21, 22 limited service capacity,44, 48, 50 lack of CBR program,22 maldistribution with other PMR professionals mainly in urban regions,25 demoralized workforce,25 inadequate resources for infrastructure and equipments,30, 41, 43 inferior quality of assistive technology products with higher cost of servicing,34 lack of time,35, 36 lack of access to research resources for therapists not in academia,35 fragmented home-rehab services,44 and lack of maintenance services for assistive products.51

Leadership and policy

Good leadership often drives the success of programs, and in our review we noted that problems with leadership and policy include lack of political will,13, 25, 26, 31, 34, 50 lack of government support,10, 32, 41, 42 lack of leadership and governance,11, 26, 32 lack of organizational mandate,20 non availability of state funding for rehabilitation services,23, 38, 39, 43 poor legislation and fragmented healthcare system,24, 40, 45, 47 as well as lack of strategies for improved access to affordable quality care.25, 51 Other factors including unavailability of regulatory bodies to oversee medical and allied health services27 no universal access to health,28 no mechanisms for coordination between government ministries and disability support organizations leading to lack of data integration,29 lack of technical consensus and health systems capacity,30, 41 no participation of PWDs and lack of stakeholder involvement,49 along with lack of political equality of the disabled,17 were among the other challenges.

Technology/advanced treatment

Lack of technological advances in areas of assistive technology, information and communication was noted to be a contributory factor to the challenges in establishing service organizations.11, 16, 45

Community-based rehabilitation

Lack of sufficient community-based rehabilitation (CBR) programs were often due to lack of resources for starting national level or local CBR programs,15, 22, 33, 36, 39, 41-43, 49 as well as failure to robustly investigate feasibility and acceptability when designing and implementing telehealth systems at CBR level.30

Social support

Lack of community or social support including10, 12, 13, 17, 19, 30, 36, 39, 49, 51 discrimination from healthcare providers,14 lack of support to clients and caregivers22 lack of utilization of telehealth in CBR settings,30 demand by some caregivers to be paid to assist their relatives/PWD33, 37 and sometimes lack of awareness on availability of services by disability organizations,48 played a role in clients not receiving optimal services.

Cultural

Common cultural beliefs that proved to be a setback include stigma surrounding disability,10, 19, 30, 32, 34 religious beliefs and practices as barriers to receive medical care,10, 13, 19, 24, 26, 43, 48 as health beliefs and racial prejudice,16 knowledge and culture about rehabilitation,30-32 language barriers30 and personal behavior (lack of interest).35

Political

Political instability and interprofessional disputes proved to be barriers to setting up effective rehabilitation service organizations.17, 32, 33, 36, 39-43, 47

Clinical

Clinical services were hampered by ineffective communication with healthcare providers,12 lack of team collaboration and communication,13 lack of skills,14, 17, 21 poor multidisciplinary collaboration13, 17, 24 inefficient first response protocol,21 and poor coordination between acute and subacute healthcare sectors.24

Registries and standards

The limitations in having registries and standards include lack of disability data, lack of guidelines and accreditation standards,24, 25, 31, 33, 41, 42 physiotherapy lacking an official definition as a discipline among other health services,27 lack of standard definitions and measurement methods on data validation and sharing,29, 40, 41 lack of disaster-related competencies,31 poor documentation of outcomes,36 poor or average compliance of rehabilitation services with global standards,41 difficulties with recognizing rehabilitation professionals in national healthcare centers.41

Facilitators

Finance

Availability of national health insurance policy or scheme (NHIS) albeit with limited or no coverage for rehabilitation,13, 25, 34 funding from government,10-13, 15-17, 21, 22, 25, 26, 38, 39 funding from external charitable organizations/ NGOs,10, 17-19, 28, 41, 42, 51 diversification of income sources and projects to strengthen sustainability,18 Bangladesh moving towards universal healthcare coverage,27 long-term rehabilitation provided under the Ministry of Social Welfare and NGOs,27 disability allowance and medical compensation for government employees in Pakistan,43 funding for purchasing equipment, vehicles, building and paying salaries,49 were some of the financial facilitators for service organization.

Facilities/resources

Availability of CBR programs,15 supportive programs, proximity of hospital and short evacuation time that enables effective treatment of severe vascular injuries in Yemen,21 government-managed general rehabilitation center and physiotherapy clinics for PWD in Chennai22 and NGOs providing healthcare services27, 48, 50 were some of the facilitators identified.

All countries had some form of health information management system which collated population-based information but most had very few indicators on rehabilitation and disability.29 Availability of videoconference/Skype with language translation interface,30 internet facility,30, 35, 40 manual to improve information delivery,30 establishment of training facilities,48 and utilization of locally available materials,49 were among the resources that were noted to facilitate service organization.

Education/clinical

Some countries had various educational programs such as physiotherapy degree10 and vocational training programs.15 Evidence-based practice (EBP) uptake was noted to be higher with higher academic degree.20 Other factors included EBP already incorporated into academic curriculum,20 medical personnel training for emergency trauma cases and handling mass casualties,21 CBR workers’ willingness to learn telehealth system,30 availability of educational resources,32, 35 international exchange program funded by government,32 long-distance education and clinical service placement,32 and training and support by rehabilitation workers (Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, Physiotherapy, Occupational therapy, Speech language pathology).37 Specialized publicly funded program such as cardiac rehabilitation programs,38 management and leadership trainings focused on the user-friendly standards for rehabilitation and their implementation,41 development management and quality assurance capabilities among rehabilitation service providers,41 and strong physiotherapy undergraduate training programs to improve capacity to provide service47 were other notable educational programs.

Discussion

This research project conducted under the auspices of the ISPRM-WHO Working Group for the “Rehabilitation capacity building in LMIC” was undertaken by several dedicated and experienced rehabilitation physicians who contribute to rehabilitation services development in LMIC settings. Only 42 articles were identified from a systematic search that related to the subject of barriers and facilitators for increasing accessibility to Rehabilitation Services in Low-and middle-income countries, including Bangladesh, Cambodia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Iran, Laos, Madagascar, Mongolia, Nepal, Nigeria, Palestine, Pakistan, Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Vietnam.

With rehabilitation services provided in primary, secondary and tertiary care hospitals, most rehabilitation service organizations did not have the required rehabilitation team including rehabilitation physicians and allied health personnel and were lacking regulatory bodies to oversee standards for rehabilitation service provision. Financing related issues were found to be the key barriers for the expansion of rehabilitation services as mentioned in 29 out of the 42 articles reviewed, with majority concerns on high cost of services38, 39, 50 financial constraints and poor socioeconomic status,13, 16-19, 33, 37, 38, 42 lack of financing funding for rehabilitation services by government and organizations,11, 23, 24, 27, 44 and lack of insurance.14, 25, 32, 43 Beside financing issues for rehabilitation services, some major barriers for accessibility to rehabilitation included a lack of rehabilitation health facilities, transport for users and advanced technologies11 for rehabilitation service provision. Other elements contributing to challenges for increased service expansion and accessibility included a lack of communication and data integration between government agencies, NGOs and CBR providers, low awareness among the population about limitations in functioning and rehabilitation needs,13, 14, 22, 24 poor perceived quality of rehabilitation services,27 and a lack of skilled health care workers and high turnover of staff in government facilities.16, 37 A poor support from government to strengthen the health system16 is one of the major concerns, including inadequate regulation and implementation of telemedicine for rehabilitation.30

A few facilitators for increased accessibility to quality rehabilitation services were identified in this review such as a National health insurance plan including rehabilitation, and funding from government and NGOs. Bangladesh27 is moving towards implementation of a universal health coverage program including government and NGO funding of rehabilitation services, whereas in Pakistan43 the government provides a disability allowance and medical compensation for government employees. Availability of CBR in countries such as Yemen21 and Chennai22 was one of the facilitators for increasing access to rehabilitation services. Other facilitators that improve quality of services included an academic degree for allied health,10, 32, 35, 37 EBP for rehabilitation,20 postgraduate training programs,38 and a management and leadership skills training program for facility managers.41

In terms of integration of rehabilitation into the health system, programs set up by NGOs were working towards handing over to local authorities,17 and collaboration with other service providers was key to deliver required interventions.21 A collaboration between acute health care and step-down rehabilitation health facilities or NGOs has been favourable.24 Several successful initiatives for strengthening rehabilitation have been described; the National Telehealth Services Program by the Department of Health in the Philippines has improved awareness for rehabilitation in rural areas,26 faculty support and credential training programs from NGOs have improved quality of care,32, 48 advocacy and outreach work from Leadership Institute (LI) in Rwanda led to increase in physiotherapy referrals,36 training through task-sharing for students and community health workers has enabled the delivery of cardiac rehabilitation,38 the use of clinical practice guidelines has been relevant to assist allied health care providers to address the challenges encountered, use of community healthcare workers has enabled extension of rehabilitation services to the community,44 and higher quality of coordinated care resulted in a quick referral and rehabilitation pathway for landmine victims.42

With regards to policy-making for rehabilitation, Ghana, Nigeria and Bangladesh have made a move towards subscription of a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) including rehabilitation although not covering the majority of the population.12, 25, 37 Policies such as integrating the patient navigation system into national health strategic planning and no refusal policy by NGOs19 have improved approaches to rehabilitation care. Thailand has strong Health Information Systems including rehabilitation and also captures detailed information from other sources such as national citizen registration databases.29 Some countries have adopted legislation toward enabling comprehensive rehabilitation and inclusive health services for people experiencing limitations in functioning through a political commitment to improve care and support for PWDs,32 improving the referral system for rehabilitation,33, 37 offering free medical treatment for government employees with disability and their families,43 and informed decision making and accountability in the provision of rehabilitation services and information.45

Societal support has helped to increase accessibility to rehabilitation care through self-help groups,15 spirit practitioners,18 disabled staff demonstrating potential positive future for other patients,19 family members giving good family support,25, 33 and societal participation from national and international NGOs,31 use of public holidays to educate community and increasing involvement of the participants and community members in education and leadership,36 and incentives to some volunteer work.37

Limitation of the study

Inadequate papers fulfilling objectives.

Conclusions

National policies

Implementation of supportive policies such as National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and various educational programs will play a crucial role in the functioning of the rehabilitation service organization.

Specific allocation of national budgets should be implemented.

All LMIC should pay more attention to optimizing logistics/ transportation facilities, disable-friendly environment and facilities such as provision of satellite rehabilitation centers for remote areas.

Government should implement the policies to promote rehabilitation service facilities and MOU with countries who are willing to assist with technical support and training.

Encourage more NGOs and CBR providers to assist with the countries’ needs.

Education

Continuous education is crucial to develop skillful rehabilitation specialists and allied health professionals.

Multiple rehabilitation CME for health care professionals and public forum will assist in disseminating rehabilitation services facilities and the needs of rehabilitation for PWDs.

Inclusion of rehabilitation sections in most of the conference to educate the health care professionals.

Government/authority of those countries lacking in rehabilitation training should create opportunities for those who are qualified and willing to do further study in rehabilitation and encourage advisory panels at Ministry of Health level.

Policy makers should include rehabilitation service development as a national agenda emphasizing on training, provision of facilities, technologies and CBR programs and collaboration with NGOs.

Government’s support

Government’s support, leadership and governance, organizational mandate, state funding for rehabilitation services, legislation, structured health care system, provision of quality care are key factors to implement an efficient rehabilitation service organization.

It is advisable to have regulatory bodies to oversee medical and allied health services.

Coordination between government ministries and disability support organization for a successful data integration are recommended.

Empowering in technology and advanced treatment should be given priority to improve rehabilitation service delivery.

Policy makers should strategize to implement CBR program for those residing at remote area with limited rehabilitation service facilities.

Consumers

Involvement of PWD and stakeholder’s is highly recommended.

Awareness raising forum to educate patients on available services needs to be encouraged.

Multidisciplinary team care approach and collaboration is mandatory especially in acute and subacute sectors to improve and optimize the patients’ care and clinical services.

National registries and clinical practice guidelines

National registries on disabilities, clinical guideline, accreditation standards for respective specialties such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech language pathology etc. are recommended.

Implementation of clinical practice guidelines for rehabilitation service provision needs to be addressed efficiently.

Supplementary Digital Material 1

Supplementary Table I

Summary of the search strategy.

Supplementary Digital Material 2

Supplementary Table II

Barriers and facilitators for expanding rehabilitation services in low- and middle-income countries – a systematic review.10-51

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

References

- 1.Rehabilitation. In: World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation [cited 2024, Mar 14].

- 2.World Health Organization. Access to rehabilitation in primary health care: an ongoing challenge. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO global disability action plan 2014-2021: Better health for all people with disability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2007. [Internet]. Available from: https:/www.un.org/disabilities/document/convention [cited 2024, Mar 14]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rehabilitation 2030: A call for action, February 6–7 2017, meeting report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/disabilities/care/Rehab2030MeetingReport2.pdf?ua=1 [cited 2024, Mar 14].

- 6.United Nations Children’s Fund. Zambia National Disability Survey. New York: UNICEF; 2015 [Internet]. Available from:https://www.unicef.org/zambia/media/1141/file/Zambia-disability-survey-2015.pdf [cited 2024, Mar 14].

- 7.United Nations Children’s Fund. Tonga Disability Survey Report. New York: UNICEF; 2018. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/pacificislands/media/1491/file/Tonga%20Disability%20Survey%20Report%202018.pdf [cited 2024, Mar 14].

- 8.The Asia Foundation. Model Disability Survey of Afghanistan 2019. San Francisco: The Asia Foundation; 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Model-Disability-Survey-of-Afghanistan-2019.pdf [cited 2024, Mar 14].

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=19621072&dopt=Abstract 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen AP, Bolton WS, Jalloh MB. Barriers to accessing and providing rehabilitation after a lower limb amputation in Sierra Leone - a multidisciplinary patient and service provider perspective. Disabil Rehabil 2022;44:2392–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33261506&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/09638288.2020.1836043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anwar SL, Adistyawan G, Wulaningsih W, Gutenbrunner C, Nugraha B. Rehabilitation for Cancer Survivors: How We Can Reduce the Healthcare Service Inequality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2018;97:764–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29905600&dopt=Abstract 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baatiema L, de-Graft Aikins A, Sav A, Mnatzaganian G, Chan CK, Somerset S. Barriers to evidence-based acute stroke care in Ghana: a qualitative study on the perspectives of stroke care professionals. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015385. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28450468&dopt=Abstract 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baatiema L, Sanuade O, Kuumuori Ganle J, et al. An ecological approach to understanding stroke experience and access to rehabilitation services in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Health Soc Care Community 2021;29:e67–e78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33278317&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/hsc.13243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bright T, Wallace S, Kuper H. A Systematic Review of Access to Rehabilitation for People with Disabilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2165. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30279358&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/ijerph15102165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deepak S. Answering the rehabilitation needs of leprosy-affected persons in integrated setting through primary health care services and community-based rehabilitation. Indian J Lepr 2003;75:127–42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15255400&dopt=Abstract [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ennion L, Johannesson A. A qualitative study of the challenges of providing pre-prosthetic rehabilitation in rural South Africa. Prosthet Orthot Int 2018;42:179–86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28318387&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/0309364617698520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harkins CS, McGarry A, Buis A. Provision of prosthetic and orthotic services in low-income countries: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int 2013;37:353–61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=23295896&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/0309364612470963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain S. Toes that look like toes: cambodian children’s perspectives on prosthetic legs. Qual Health Res 2011;21:1427–40. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=21685313&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/1049732311411058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibbotson JL, Luitel B, Adhikari B, Jagt KR, Bohler E, Riviello R, et al. Overcoming Barriers to Accessing Surgery and Rehabilitation in Low and Middle-Income Countries: An Innovative Model of Patient Navigation in Nepal. World J Surg 2021;45:2347–56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33893524&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00268-021-06035-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibikunle PO, Onwuakagba IU, Maduka EU, Okoye EC, Umunna JO. Perceived barriers to evidence-based practice in stroke management among physiotherapists in a developing country. J Eval Clin Pract 2021;27:291–306. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32424823&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/jep.13414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain RP, Meteke S, Gaffey MF, Kamali M, Munyuzangabo M, Als D, et al. Delivering trauma and rehabilitation interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5(Suppl 1):e001980. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32399262&dopt=Abstract 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamalakannan S, Gudlavalleti Venkata M, Prost A, Natarajan S, Pant H, Chitalurri N, et al. Rehabilitation Needs of Stroke Survivors After Discharge From Hospital in India. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:1526–1532.e9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=26944710&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamenov K, Mills JA, Chatterji S, Cieza A. Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:1227–37. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29303004&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/09638288.2017.1422036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan F, Amatya B, Sayed TM, Butt AW, Jamil K, Iqbal W, et al. World Health Organisation Global Disability Action Plan 2014-2021: challenges and perspectives for physical medicine and rehabilitation in Pakistan. J Rehabil Med 2017;49:10–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28101563&dopt=Abstract 10.2340/16501977-2149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan F, Owolabi MO, Amatya B, Hamzat TK, Ogunniyi A, Oshinowo H, et al. Challenges and barriers for implementation of the World Health Organization Global Disability Action Plan in low- and middle- income countries. J Rehabil Med 2018;50:367–76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28980008&dopt=Abstract 10.2340/16501977-2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leochico CF, Espiritu AI, Ignacio SD, Mojica JA. Challenges to the Emergence of Telerehabilitation in a Developing Country: A Systematic Review. Front Neurol 2020;11:1007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33013666&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fneur.2020.01007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mamin FA, Hayes R. Physiotherapy in Bangladesh: Inequality Begets Inequality. Front Public Health 2018;6:80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29629365&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsen SL. A closer look at amputees in Vietnam: a field survey of Vietnamese using prostheses. Prosthet Orthot Int 1999;23:93–101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10493135&dopt=Abstract 10.3109/03093649909071619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McPherson A, Durham J, Richards N, Gouda H, Rampatige R, Whittaker M. Strengthening health information systems for disability-related rehabilitation in LMICs. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:384–94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=27935799&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell-Gillespie B, Hashim H, Griffin M, AlHeresh R. Sustainable support solutions for community-based rehabilitation workers in refugee camps: piloting telehealth acceptability and implementation. Global Health 2020;16:82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32933537&dopt=Abstract 10.1186/s12992-020-00614-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mousavi G, Khorasani-Zavareh D, Ardalan A, Khankeh H, Ostadtaghizadeh A, Kamali M, et al. Continuous post-disaster physical rehabilitation: a qualitative study on barriers and opportunities in Iran. J Inj Violence Res 2019;11:35–44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30635998&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naicker AS, Htwe O, Tannor AY, De Groote W, Yuliawiratman BS, Naicker MS. Facilitators and Barriers to the Rehabilitation Workforce Capacity Building in Low- to Middle-Income Countries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2019;30:867–77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31563176&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.pmr.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naidoo U, Ennion L. Barriers and facilitators to utilisation of rehabilitation services amongst persons with lower-limb amputations in a rural community in South Africa. Prosthet Orthot Int 2019;43:95–103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30044179&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/0309364618789457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osam JA, Opoku MP, Dogbe JA, Nketsia W, Hammond C. The use of assistive technologies among children with disabilities: the perception of parents of children with disabilities in Ghana. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2021;16:301–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31603354&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/17483107.2019.1673836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paci M, Faedda G, Ugolini A, Pellicciari L. Barriers to evidence-based practice implementation in physiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Qual Health Care 2021;33:mzab093. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34110410&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/intqhc/mzab093 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Pascal MR, Mann M, Dunleavy K, Chevan J, Kirenga L, Nuhu A. Leadership Development of Rehabilitation Professionals in a Low-Resource Country: A Transformational Leadership, Project-Based Model. Front Public Health 2017;5:143. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28691003&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Periquet AO. Community-based rehabilitation in the Philippines. Int Disabil Stud 1989;11:95–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=2534311&dopt=Abstract 10.3109/03790798909166400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pesah E, Turk-Adawi K, Supervia M, Lopez-Jimenez F, Britto R, Ding R, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation delivery in low/middle-income countries. Heart 2019;105:1806–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31253695&dopt=Abstract 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pienaar E, Stearn N, Swanepoel W. Self-reported outcomes of aural rehabilitation for adult hearing aid users in a South African context. S Afr J Commun Disord 2010;57:4, 6, 8 passim. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=21329261&dopt=Abstract 10.4102/sajcd.v57i1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prathaneel B, Makarabhirom K, Jaiyong P, Pradubwong S. Khon Kaen: a community-based speech therapy model for an area lacking in speech services for clefts. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2014;45:1182–95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=25417522&dopt=Abstract [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pryor W, Newar P, Retis C, Urseau I. Compliance with standards of practice for health-related rehabilitation in low and middle-income settings: development and implementation of a novel scoring method. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:2264–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29663840&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/09638288.2018.1462409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramstrand N, Maddock A, Johansson M, Felixon L. The lived experience of people who require prostheses or orthoses in the Kingdom of Cambodia: A qualitative study. Disabil Health J 2021;14:101071. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33583726&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rathore FA, New PW, Iftikhar A. A report on disability and rehabilitation medicine in Pakistan: past, present, and future directions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:161–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=21187218&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheffler E, Mash R. Figuring it out by yourself: perceptions of home-based care of stroke survivors, family caregivers and community health workers in a low-resourced setting, South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2020;12:e1–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33054273&dopt=Abstract 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skempes D, Stucki G, Bickenbach J. Health-related rehabilitation and human rights: analyzing states’ obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:163–73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=25130185&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuckey R, Draganovic P, Ullah MM, Fossey E, Dillon MP. Barriers and facilitators to work participation for persons with lower limb amputations in Bangladesh following prosthetic rehabilitation. Prosthet Orthot Int 2020;44:279–89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32686604&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/0309364620934322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tawiah AK, Borthwick A, Woodhouse L. Advanced Physiotherapy Practice: A qualitative study on the potential challenges and barriers to implementation in Ghana. Physiother Theory Pract 2020;36:307–15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29897312&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/09593985.2018.1484535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tinney MJ, Chiodo A, Haig A, Wiredu E. Medical rehabilitation in Ghana. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:921–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17577726&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/09638280701240482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turmusani M, Vreede A, Wirz SL. Some ethical issues in community-based rehabilitation initiatives in developing countries. Disabil Rehabil 2002;24:558–64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12171646&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/09638280110113449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urimubenshi G, Cadilhac DA, Kagwiza JN, Wu O, Langhorne P. Stroke care in Africa: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Stroke 2018;13:797–805. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29664359&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/1747493018772747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao DP, Inoue K, Sy MP, Bontje P, Suyama N, Yatsu C, et al. Experience of Filipinos with Spinal Cord Injury in the Use of Assistive Technology: An Occupational Justice Perspective. Occup Ther Int 2020;2020:6696296. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33304205&dopt=Abstract 10.1155/2020/6696296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table I

Summary of the search strategy.

Supplementary Table II

Barriers and facilitators for expanding rehabilitation services in low- and middle-income countries – a systematic review.10-51