Abstract

Background

Identifying germline predisposition in CNS malignancies is of increasing clinical importance, as it contributes to diagnosis and prognosis, and determines aspects of treatment. The inclusion of germline testing has historically been limited due to challenges surrounding access to genetic counseling, complexity in acquiring a germline comparator specimen, concerns about the impact of findings, or cost considerations. These limitations were further defined by the breadth and scope of clinical testing to precisely identify complex variants as well as concerns regarding the clinical interpretation of variants including those of uncertain significance.

Methods

In the course of conducting an IRB-approved protocol that performed genomic, transcriptomic and methylation-based characterization of pediatric CNS malignancies, we cataloged germline predisposition to cancer based on paired exome capture sequencing, coupled with computational analyses to identify variants in known cancer predisposition genes and interpret them relative to established clinical guidelines.

Results

In certain cases, these findings refined diagnosis or prognosis or provided important information for treatment planning.

Conclusions

We outline our aggregate findings on cancer predisposition within this cohort which identified 16% of individuals (27 of 168) harboring a variant predicting cancer susceptibility and contextualize the impact of these results in terms of treatment-related aspects of precision oncology.

Keywords: cancer predisposition, genetic susceptibility, hereditary cancer syndrome, molecular profiling

Key Points.

Germline susceptibility contributes to ~16% of pediatric brain cancers.

Comprehensive genomic profiling is required for identifying pathogenic variants.

Germline cancer predisposition is increasingly critical for treatment decision-making.

Importance of the Study.

In the next-generation sequencing era, our ability to expand the scope of inquiry in the setting of germline predisposition to cancer has yielded an improved appreciation of this contributor to cancer development, especially in pediatric CNS malignancies. Increasingly, this knowledge contributes to other aspects of care including precision of diagnosis and the clinical care of our youngest patients. As such, the translational importance of broad genomic testing that can accurately identify and inform clinical reporting of all types of variants contributing to cancer predisposition is obvious and impactful for patients and families. As reported recently, this impact now includes the identification of patients who have underlying mismatch repair deficiencies and an attendant high tumor mutational burden indicative of response to checkpoint blockade therapies.

Large-scale genomic characterization studies of pediatric CNS malignancies in the era of next-generation sequencing (NGS) have identified germline alterations that predispose to cancer onset. The breadth and scope of discovery of these foundational projects have identified both focal (single nucleotide and insertion–deletion) variants as well as copy number and structural alterations in around 400 cancer predisposition loci.1 Clinical sequencing of the germline in concert with tumor mutational profiling has historically been challenging for several reasons. This includes patient access for both the purpose of consent as well as acquisition of a germline specimen. Clinical and laboratory workflows may present challenges in genetic counseling, as well as access to phlebotomy or other germline specimen collection methods, which may be exacerbated if the laboratory primarily tests from archival tumor samples. The cost of assaying the germline sample, including challenges in reimbursement, can serve as an additional barrier. Furthermore, paired germline sequencing may be avoided due to the challenges of interpreting certain variants in the context of cancer risk, and hence the resulting difficulty both in communicating these results to families and patients and in translating variants of uncertain significance into the need for clinical surveillance regimens. Comparing the frequency of germline pathogenic variants across studies is complex, due to disparate cohort selection criteria and distributions of disease histology. For example, an analysis of 1022 medulloblastoma patients identified 6 medulloblastoma predisposition genes on the basis of rare variant burden analysis (APC, BRCA2, PALB2, PTCH1, SUFU, and TP53), and further noted that half of all patients with pathogenic germline variants were not recognized based on family history of cancer; however, the patients included in this study were largely sourced from tertiary referral centers with inherent referral bias.2 In juxtaposition, a population-based study of cancer predisposition in 280 pediatric glioma patients from California identified putatively pathogenic germline variants among 31 patients (11.1%) and had the benefit of eliminating referral bias, but only included individuals who self-reported as Latino or non-Latino white race/ethnicity in order to facilitate comparisons with public whole-exome sequencing control datasets.3 As germline results have become more important clinically and in determining treatment choices (TP53 alterations in the setting of radiation therapy avoidance, for example), there has been a concomitant application of germline testing into the cancer precision oncology profiling rubric.

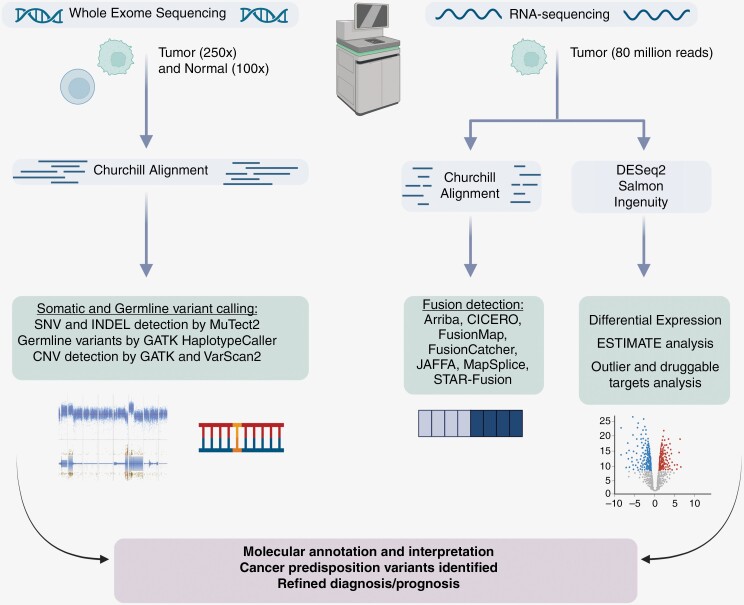

In 2018, we opened an institutional IRB-approved study (IRB17-00206) that pursued molecular profiling of DNA and RNA in the setting of pediatric cancer and hematologic malignancies. In this protocol, patients and families consented to undergo next-generation sequencing (NGS) of all protein-coding genes (the “exome”), in order to compare and identify variants in genomic DNA extracted from tumor and normal samples. RNA extracted from tumor was also sequenced and analyzed to identify the driver or diagnostic fusion genes and outlier gene expression. Due to the World Health Organization (WHO) adding methylation arrays to the clinical standard of diagnosis for CNS malignancies in 2021, we also adopted tumor DNA testing using Illumina methylation microarray technology and the DKFZ classifier4 for methylation-based classification of patients with CNS cancer. The overall workflow is outlined in Figure 1. Multi-platform testing provided precise diagnostic classification and permitted the identification of cancer-associated somatic single nucleotide and insertion–deletion (indel) variants, gene fusions, somatic and germline copy number alterations, and germline variants associated with cancer predisposition. In cases where a pathogenic or known pathogenic variant in any of these categories was identified by expert data evaluation, any variant deemed important for clinical decision-making or diagnosis (by the clinical care team) was subjected to clinical testing in our CAP-accredited and CLIA-certified laboratory, such that clinically confirmed variants could be reported into the patient’s medical record. Genetic counseling and cascade testing were provided to any patients and their families as a part of the IRB protocol when confirmatory clinical testing was obtained for a germline cancer predisposition variant.

Figure 1.

Workflow for Cancer/Germline Exome and Cancer RNA NGS Data Generation and Analysis. This figure illustrates the assays and analytics utilized in the NGS-based molecular characterization of pediatric CNS malignancies by our IRB-approved study.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All patients reported in this manuscript were enrolled on a study approved by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital IRB (IRB17-00206). Patients aged 18 or older were consented in person or by phone. Parental or legal guardian permission was obtained for patients under 18 years of age either in person or by phone. Assent was obtained from minors aged 9–17 years of age by written signature.

Enhanced Exome Sequencing

DNA NGS libraries were prepared using input tumor or normal DNA and NEB Ultra II FS reagents (New England Biolabs). Target enrichment by hybrid capture was performed using the IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v1.0 enhanced or v2.0 with the xGenCNV Backbone and Cancer-Enriched Panels-Tech Access (Integrated DNA Technologies). Paired-end 151-bp reads were generated on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 or NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina Inc.). Data analysis was performed using Churchill.5 Reads were aligned to the human genome reference sequence (build GRCh37 or GRCh38) using BWA (v0.7.15) and refined according to community-accepted guidelines for best practices (https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us). Duplicate sequence reads were removed using samblaster-v.0.1.22, and local realignment was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (v4.1.9).6 Somatic single nucleotide variation (SNV) and indel detection were performed using MuTect2.7 Germline variants were called using GATK’s HaplotypeCaller.8 Copy number variation (CNV) was assessed using a combination of GATK (v4.2.4.1) and VarScan2.9

Variant Evaluation and Interpretation Processes

SNV, indel and copy number variants were identified and prioritized for further evaluation. In relation to cancer predisposition, disease-associated genes were curated from the published literature and genomic databases including those described by Zhang et al.,1 as well as genes with strong (Tier 1) or emerging (Tier 2) evidence of germline or somatic cancer association as documented in the Cancer Gene Census.10 Variants within the curated set of genes were assessed in relation to attributes such as population frequency, impact on the gene product, functional evidence, documentation in a reputable database (eg ClinVar), segregation, and other attributes as described in the standards and guidelines set forth by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology for the interpretation of sequence variants.11 Germline variants were also examined in the tumor sample given that paired data were available to inform on the loss of heterozygosity, copy number alteration, or the presence of somatic variation associated with a second hit within the locus. CNV was evaluated in relation to the aforementioned curated gene lists, along with consideration of the mechanism of action of the involved locus in association with disease. Once published, the technical standard recommendations set forth by the ACMG and Cancer Genomics Consortium for the evaluation of cancer-associated CNV12 were further considered in our assessment. The study team discussed any positive research results indicative of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in germline cancer predisposition genes with the oncologist of record, who then ordered clinical confirmation of the variant to be performed by our CAP/CLIA laboratory. Upon clinical confirmation, the patient and family were apprised of the test result in our Cancer Predisposition Clinic and counseled according to appropriate cascade testing.

Enrolled subjects had the option to consent to the return of secondary findings including medically actionable genetic variants, as well as carrier variants. Medically actionable secondary findings were reported in accordance with the policy statement set forth by the ACMG (v2.0 or 3.0) in the setting of clinical exome and genome sequencing.13,14 An internally curated list of genes with relevance to carrier status (for reproductive counseling) were also analyzed (ASPA, BLM, CFTR, FANCC, G6PD, GBA, HBB, HEXA, IKBKAP, MCOLN1, and SMPD1) to enable the return of pathogenic or likely pathogenic findings.

Results and Discussion

Cohort Findings in Cancer Predisposition Syndromes

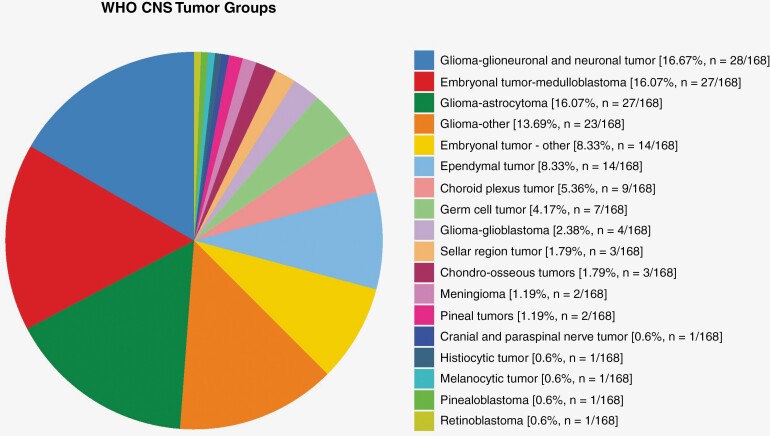

Clinically significant germline alterations were identified in 23.7% (38/168) of patients with CNS malignancies enrolled on this protocol. This includes cancer predisposition in 16% (27/168), carrier alterations in 4.8% (8/168), and medically actionable secondary findings in 2.4% (4/168) of patients. One patient did not undergo germline sequencing due to sample unavailability. The majority of alterations detected were single nucleotide variants-36 SNVs were found in 18 different genes as noted in Table 1. In contrast, only 4 copy number variants were identified, 3 of which were detected in the SMARCB1 gene (Table 2). Germline exome sequencing for our cohort of patients with pediatric CNS malignancies identified cancer predisposition in 16% of cases, which is within the 8–18% range reported by other studies of sporadic pediatric malignancies.1,15–19 Interestingly, by evaluating only the CNS patients in these referenced studies, the percentages of identified germline pathogenic/likely pathogenic alterations in cancer predisposition genes exhibited a wide range, between 4.5% and 31%. This discrepancy emphasizes the importance of methodologic transparency in cohort assembly and in the breadth of genomic inquiry, as biases in individual cohorts or in the amount of the genome being assayed can produce increased variability in estimating germline contributions to pediatric CNS malignancies. Proportions of WHO CNS tumor classification-based diagnoses in our cohort are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Germline Single Nucleotide Variants Identified by Enhanced Exome Sequencing

| Gene | SNV | Cancer Predisposition | Carrier/ Medically Actionable |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CHEK2

(NM_007194.4) |

c.470T > C:p.Ile157Thr c.1100del:p.Thr367MetfsTer15 c.444 + 1G > A:p.? |

✔ ✔ ✔ |

||

|

CFTR

(NM_000492.4) |

c.1521_1523del:p.Phe508del (n = 4) c.1624G > T:p.Gly542Ter |

✔ ✔ |

||

|

GBA

(NM_000157.4) |

c.1192C > T:p.Arg398* | ✔ | ||

|

GLA

(NM_000169.3) |

c.1087C > T p.Arg363Cys | ✔ | ||

|

GPR161

(NM_001375883.1) |

c.972T > A:p.Tyr344Ter | ✔ | ||

|

G6PD

(NM_001360016.2) |

c.844G > C:p.Asp282His | ✔ | ||

|

HBB

(NM_000518.5) |

c.20A > T:p.Glu7Val | ✔ | ||

|

KCNQ1

(NM_000218.3) |

c.1085A > G p.Lys362Arg | ✔ | ||

|

NF1

(NM_001042492.3) |

c.1318C > T:p.Arg440Ter (n = 2) c.4977_4980del: p.Lys1661GlyfsTer36 c.7189G > A:p.Gly2397Arg |

✔ ✔ ✔ |

||

|

NF2

(NM_000268.4) |

c.1198del:p.Gln400ArgfsTer26 | ✔ | ||

|

MSH6

(NM_000179.3) |

c.3939_3957dup:p.Ala1320SerfsTer5 (n = 2) | ✔ | n = 1 (Homozygous); n = 1 (Heterozygous) | |

|

MYO18B

(NM_032608.7) |

c.6768del p.Leu2257SerfsTer16 c.6660_6670del p.Arg2220SerfsTer74 | ✔ ✔ |

Both alterations noted in a single patient | |

|

PALB2

(NM_024675.4) |

c.3170_3175delCTTCAGinsAATCA:p.Val10 | ✔ | ||

|

PMS2

(NM_000535.6) |

c.137G > T:p.Ser46Ile c.1A > G:p.Met1? |

✔ ✔ |

||

|

PTPN11

(NM_002934.5) |

c.179G > C:p.Gly60Ala c.209A > G:p.Lys70Arg c.922A > G:p.Asn308Asp |

✔ ✔ ✔ |

||

|

SDHA

(NM_004168.4) |

c.1579del p.Arg527ValfsTer20 | ✔ | ||

|

SMARCB1

(NM_003073.5) |

c.644del:p.Pro215LeufsTer14 c.771_772dup: p.(Ser258CysfsTer10) |

✔ ✔ |

Mosaic |

|

|

TP53

(NM_000546.6) |

c.743G > A:p.Arg248Gln c.916C > T:p.Arg306Ter c.548C > G:p.Ser183Ter c.722C > G:p.Ser241Cys |

✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ |

Table 2.

Copy Number Germline Variants Identified by Enhanced Exome Sequencing

| Gene | Copy Number Variant | Size and Disease Association |

|---|---|---|

| HNF1B | 17q12 deletion | 1.31 Mb; renal cysts and diabetes syndrome |

| SMARCB1 | 22q11.21-q11.23 loss | 2.68 Mb deletion; ATRT, Distal 22q deletion syndrome |

| SMARCB1 | 22q11.22q11.23 | 1.34 Mb deletion; ATRT |

| SMARCB1 | 22q11.22q11.23 | 1.88 Mb deletion;ATRT |

Figure 2.

CNS diagnosis by WHO classification. This figure shows the proportions and numbers of different WHO classification-based diagnoses for the CNS malignancies characterized by molecular profiling analyses in this cohort.

Genetic cancer predisposition was identified in 27 patients (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1). These diagnoses included rhabdoid tumor predisposition syndrome (RTPS), Li Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), Lynch syndrome, neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2, NS, and tumor predisposition syndrome 4 (TPDS4). RTPS was detected in 5 patients with atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (ATRT); notably, 4 of these individuals presented with synchronous renal rhabdoid tumors.20,21 LFS was detected in 2 patients with choroid plexus carcinoma, as well as in individuals with medulloblastoma and anaplastic pleomorphic xanthroastrocytoma. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) was detected in 4 patients, of which 2 were diagnosed with pilocytic astrocytoma. Noonan syndrome (NS) was identified in 3 patients, all of whom were diagnosed with glioneuronal tumors. CHEK2 alterations associated with TPDS4 were noted in 3 patients with disparate diagnoses: medulloblastoma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, and atypical meningioma. These cases have been previously reported.22 Alterations in DNA repair genes associated with mismatch repair cancer syndrome and Lynch syndrome were identified in 4 cases. Of these, 2 patients diagnosed with glioblastoma were found to have heterozygous germline alterations in PMS2 consistent with Lynch syndrome 4. Germline MSH6 gene alterations were detected in 2 patients with high-grade gliomas, 1 with heterozygous MSH6 (NM_000179.3) p.Ala1320SerfsTer5 consistent with Lynch syndrome 5, and the other with homozygous MSH6 (NM_000179.3) p.Ala1320SerfsTer5, diagnostic for mismatch repair cancer syndrome 3 (also described as constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndrome). Germline alterations in GPR161, NF2, PALB2, and SDHA were identified in single patients.

Table 3.

Cancer Predisposition and CNS Malignancy Diagnoses

| Cancer Predisposition | Age at Cancer Diagnosis (y) | Sex | Germline Alteration | Malignancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familial Breast-Ovarian Cancer 5 | 0.5 | M | NM_024675.4(PALB2):c.3170_3175delCTTCAGinsAATCA:p.Val1059fsTer18 | Pilocytic astrocytoma |

| Li Fraumeni Syndrome | 5 | M | NM_000546.6(TP53):c.548C > G:p.Ser183Ter | Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma |

| Li Fraumeni Syndrome | 4 | M | NM_000546.6(TP53):c.722C > G:p.Ser241Cys | Medulloblastoma, SHH subgroup |

| Li Fraumeni Syndrome | 1.2 | F | NM_000546.6(TP53):c.743G > A:p.Arg248Gln | Choroid plexus carcinoma |

| Li Fraumeni Syndrome | 0.92 | M | NM_000546.6(TP53):c.916C > T:p.Arg306Ter | Choroid plexus carcinoma |

| Lynch Syndrome 4 | 14 | F | NM_000535.6(PMS2):c.1A > G:p.Met1? | Glioblastoma |

| Lynch Syndrome 4 | 13 | M | NM_000535.6(PMS2):c.137G > T:p.Ser46Ile | Glioblastoma |

| Lynch Syndrome 5 | 13 | F | NM_000179.3(MSH6):c.3939_3957dup:p.Ala1320SerfsTer5 | Diffuse midline glioma H3 K27M mutant |

| Medulloblastoma Predisposition Syndrome | 1.5 | M | NM_001375883.1(GPR161):c.972T > A:p.Tyr344Ter | Medulloblastoma, SHH subgroup |

| Mismatch Repair Cancer Syndrome 3 | 8 | F | NM_000179.3(MSH6):c.3939_3957dup:p.Ala1320SerfsTer5 | Adult-type diffuse high-grade glioma, IDH wildtype |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 11 | F | NM_001042492.3(NF1):c.1318C > T:p.Arg440Ter | Anaplastic astrocytoma |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 0.5 | F | NM_001042492.3(NF1):c.1318C > T:p.Arg440Ter | Plexiform neurofibroma |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 4 | M | NM_001042492.3(NF1):c.4977_4980del:p.Lys1661GlyfsTer36 | Pilocytic astrocytoma |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 12 | F | NM_001042492.3(NF1):c.7189G > A:p.Gly2397Arg | Pilocytic astrocytoma |

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | 12 | M | NM_000268.4(NF2):c.1198del:p.Gln400ArgfsTer26 | Meningioma |

| Noonan Syndrome | 9 | F | NM_002834.5(PTPN11):c.209A > G:p.Lys70Arg | Glioneuronal neoplasm with worrisome molecular features, not elsewhere classified |

| Noonan Syndrome | 21 | M | NM_002834.5(PTPN11):c.179G > C:p.Gly60Ala | Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor |

| Noonan Syndrome | 16 | M | NM_002834.5(PTPN11):c.922A > G:p.Asn308Asp | Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor |

| Pheochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Syndrome 5 | 4 | F | NM_004168.4(SDHA):c.1579del p.Arg527ValfsTer20 (carrier) | Yolk sac tumor |

| Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome | 0.83 | F | NM_003073.5(SMARCB1):c.644del:p.Pro215LeufsTer14 | Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor and rhabdoid tumor of the kidney |

| Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome | 13 | M | NM_003073.5(SMARCB1):c.771_772dup: p.Ser258CysfsTer10 (mosaic ~20% variant allele frequency) | Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor |

| Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome/Distal 22q deletion syndrome | 5 | F | 22q11.21-q11.23 loss (including BCR, IGL, MAPK1, SMARCB1) | Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor |

| Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome | 0.17 | F | 1.34 Mb deletion on 22q11.22-q11.23 (including SMARCB1) | Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor and rhabdoid tumor of the kidneya |

| Rhabdoid Tumor Predisposition Syndrome | 0.13 | F | 1.88 Mb deletion of 22q11.22q-11.23 (including SMARCB1) | Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor and rhabdoid tumor of the kidney |

| Tumor Predisposition Syndrome 4 | 6 | M | NM_007194.4(CHEK2):c.470T > C:p.Ile157Thr | Medulloblastoma, Group 4 |

| Tumor Predisposition Syndrome 4 | 9 | M | NM_007194.4(CHEK2):c.1100del:p.Thr367MetfsTer15 | Atypical meningioma |

| Tumor Predisposition Syndrome 4 | 7 | M | NM_007194.4(CHEK2):c.444 + 1G > A:p.? | Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma |

aTumor sequencing for this sample was performed on rhabdoid tumor only.

The incorporation of comprehensive genomic profiling using multiple modalities inclusive of both germline and disease-involved tissue, poised our study well to expand on existing knowledge in this field. Our cohort included syndromic germline variants for which cancer development constitutes a significant morbidity such as LFS (≥70% lifetime risk)23 and CMMRD, a syndrome with cancer often occurring within the first decade of life.24 This is in contrast to that of NS, a collectively common autosomal dominant genetic disorder (1:1000–1:2500),25 which demonstrates an estimated cancer risk of 4% by age 20.26 NS, in addition to the collective RASopathies, has displayed some genotype–phenotype correlations, with certain genes and variants more commonly associated with cancer, particularly in hematologic malignancy.27 Interestingly, 3 patients with CNS malignancies in our cohort also harbored NS-associated germline pathogenic variants. Two of 3 NS diagnoses were made from paired exome sequencing analysis carried out through this translational protocol, thereby allowing refined surveillance, management, and counseling.

Carrier Alterations and Medically Actionable Secondary Findings

Carrier alterations were reported for 8 patients (8/168, 4.8%). Four patients were heterozygous for CFTR (NM_000492.4) p.Phe508del, and 1 patient presented with a CFTR (NM_000492.4) p.Gly542Ter alteration. Heterozygous alterations in G6PD, HBB, and GBA were each found in a single patient. These genes are associated with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, sickle cell disease, and Gaucher disease, respectively.

Medically actionable secondary findings were noted in 4 cases. GLA (NM_000169.3) p.Arg363Cys conferring Fabry disease was identified in a female patient with a low grade glioneuronal tumor and was clinically confirmed. A 17q12 deletion incorporating the HNF1B gene associated with renal cysts and diabetes syndrome was identified, was clinically confirmed, and the patient is followed by nephrology. One patient with ganglioglioma was discovered to have a KCNQ1 (NM_000218.3) p.Lys362Arg alteration that is frequently documented as likely pathogenic (ClinVar Variation ID: 52953) in association with prolonged QT syndrome. Klippel–Feil syndrome was identified in 1 patient found to carry compound heterozygous variants in MYO18B (NM_032608.5, p.Arg2220SerfsTer74 and p.Leu2257SerfsTer16). Both variants were clinically confirmed, and cascade testing led to a similar diagnosis for a sibling in utero.28

Importance of Germline Comparator Data

The inclusion of paired germline exome data demonstrates significant advantages, particularly in the interpretation of tumor-associated variation and disease diagnosis refinement. For example, 1 patient we studied was previously diagnosed with an IDH wildtype adult-type diffuse high-grade glioma by an outside laboratory that performed panel-based tumor somatic profiling of 101 genes. Their clinical results reported a high mutational burden, and listed 15 gene variants, 11 of which were at near-to slightly reduced heterozygous allele frequency, challenging their interpretation as either somatic or germline. This patient carried a clinical diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis 1 due to the observation of numerous cafe au lait spots, inguinal and axillary freckling, and Lisch nodules. However, prior reference laboratory clinical testing of NF1 and SPRED1 through NGS and deletion/duplication testing was negative from blood. Our paired exome analysis identified a homozygous germline MSH6 variant (NM_000179.2(MSH6):c.3939_3957dup:p.Ala1320SerfsTer5) in tandem with a region of homozygosity of 2p, resulting in a diagnosis of CMMRD. This patient was also noted to have 12% of the genome comprised of long-contiguous stretches of homozygosity consistent with a genomic finding of consanguinity. The clinical overlap of CMMRD and NF1 phenotypes has been previously described.29 Notably, the MSH6 germline variant we identified was reported as a somatic variant with a VAF of 37% in the tumor-only panel-based testing at the outside laboratory. This VAF was likely underestimated as the MSH6 variant consists of a 19bp duplication which results in a high percentage of soft clipping in aligned reads and a reduction in overall aligned reads in comparison to SNVs. The numerous other variants with near-to slightly reduced heterozygous VAF were further clarified as being germline or somatic by our paired exome testing, allowing us to accurately identify the etiology of germline susceptibility, and to assign and interpret somatic variation. Achieving an accurate diagnosis enabled appropriate genetic counseling and cancer surveillance to occur for this patient and family. Diagnostic criteria to aid in the identification and definition of CMMRD have been proposed30,31 and increasing evidence suggests that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be impactful in treatment and improved survival amid cancers with high mutational burden in this population.32 While immune checkpoint inhibitors were not implemented for CNS malignancy in this patient, treatment with pembrolizumab was later initiated after a subsequent diagnosis of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma. While this patient, unfortunately, died secondary to infectious complications, the identification and application of targeted treatment were enabled by germline genomic testing. This case illustrates the impact that cancer, as an inherited disease, can have and emphasizes the clear advantage of exome-wide, paired germline studies.

Potentiating Discovery of New Gene-Disease Associations

The paired exome approach also enables the identification of novel cancer predisposition genes and variants or those not previously associated with a given cancer type. The American College of Medical Genetics has established best practices for the report of germline variation for individuals who undergo cancer-related testing.33 Care in clinical interpretation needs to be taken to understand if such variation is a secondary finding, or is potentially contributory to the cancer under study. One such example from our cohort involved a patient diagnosed with a yolk sac tumor who harbored a germline variant in SDHA (NM_004168.4) predicted to encode a premature stop of translation (p.Arg527ValfsTer20). Germline pathogenic variation among succinate dehydrogenase complex genes (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHB) is associated with Hereditary Paraganglioma–Pheochromocytoma Syndrome, which may result in the presentation of a variety of tumors (paraganglioma, pheochromocytoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and pulmonary chondroma).34 The observed SDHA variant was considered pathogenic in ClinVar by multiple clinical laboratories (Variant ID:653810) and demonstrated an enriched variant allele frequency in the tumor (60%) relative to the germline (43%), lending evidence for its potential disease association with the yolk sac tumor. A recent study suggests that the cancer association for SDHA pathogenic germline variation may be broader than previously known, including neuroblastoma, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, colon cancer, and prostate cancer.35 Furthermore, there are rare reports of succinate dehydrogenase gene variation described in germ cell tumors including in mediastinal germ cell tumor and in testicular seminoma, the latter of which demonstrated loss of heterozygosity of a nonsense variant in SDHD.36,37 More recently, co-occurrence of a germline pathogenic SDHA variant with a somatic KIT mutation was reported in a CNS germinoma, with no detected loss of heterozygosity or second hit in SDHA.38 The authors speculated that the SDHA variant might be disease-modifying and contribute to tumor aggressiveness but recognized that further evidence is necessary to establish a relationship between succinate dehydrogenase complex gene variants and germ cell tumors.

In such examples, it is critical to correlate germline and somatic variation along with histopathologic findings, additional molecular studies, and clinical presentation, to best interpret genetic contribution to disease. When disease–gene relationships remain uncertain, the detection of a secondary cancer predisposition variant in an individual with a seemingly unrelated cancer lends value for counseling, the opportunity for cascade testing, and at times may result in altered management or surveillance. As genomic profiling studies increasingly utilize testing of a germline comparator, cumulative evidence will shed additional light on disease–gene relationships, emphasizing the importance of publishing case report findings and sharing data broadly.

Exomes Permit Re-evaluation of Emergent Germline Susceptibility Genes

Another benefit of exome sequencing in this patient population is that emerging gene targets with disease association can be readily evaluated without expanding the gene panel. This was demonstrated by the discovery of a GPR161 (NM_001375883.1) p.Tyr344Ter germline alteration in a patient with medulloblastoma. The association between GPR161 germline alterations and medulloblastoma predisposition syndrome was not described until 2020,39 2 years after our protocol had opened to enrollment. However, with refinement to our variant prioritization strategies, such emerging or expanding disease–gene relationships can be incorporated readily into our variant review workflow.

Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of this translational study is that it was founded on the premise of clinician nomination for individuals with rare or treatment-refractory cancers, rather than on the basis of systematic selection. While this enabled our team to focus on cases of significant clinical interest, it also may have led to selection bias in our cohort. Despite this limitation, our findings support much of the commonly referenced literature surrounding germline cancer predisposition in this population, while highlighting opportunities for further research, improved definition of germline susceptibility loci, and collaboration.

Our findings underscore the importance of paired germline and tumor testing in the pediatric cancer patient population and the potential benefits of exome sequencing in quickly incorporating emerging genes of clinical importance.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Elaine R Mardis, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Samara L Potter, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Kathleen M Schieffer, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pathology, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Elizabeth A Varga, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Mariam T Mathew, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pathology, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Heather M Costello, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Gregory Wheeler, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Benjamin J Kelly, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Katherine E Miller, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Elizabeth A R Garfinkle, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Richard K Wilson, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Catherine E Cottrell, The Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA; Department of Pathology, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the Nationwide Insurance Innovation Fund.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Authorship statement

S.L.P. (REDCap data capture and curation, Writing); E.A.V. (REDCap data capture and curation, Patient consent, Writing); K.M.S. (REDCap data capture and curation, Data analysis, Writing); M.T.M. (REDCap data capture and curation, Data analysis); C.E.C. (REDCap data capture and curation, Data analysis, Writing); H.M.C. (Data analysis); G.W. (Data analysis); B.J.K. (Data analysis); K.E.M. (Data analysis); E.A.R.G. (Data analysis); E.R.M. (Writing).

This paper is being submitted as one of a series focused on the June 2023 meeting report from the Third Wyss Family “Think Tank” on Genetic Predisposition to Primary CNS Cancers in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults.

References

- 1. Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G, et al. Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(24):2336–2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waszak SM, Northcott PA, Buchhalter I, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of genetic predisposition in medulloblastoma: a retrospective genetic study and prospective validation in a clinical trial cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):785–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muskens IS, de Smith AJ, Zhang C, et al. Germline cancer predisposition variants and pediatric glioma: a population-based study in California. Neuro Oncol. 2020;22(6):864–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555(7697):469–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelly BJ, Fitch JR, Hu Y, et al. Churchill: an ultra-fast, deterministic, highly scalable and balanced parallelization strategy for the discovery of human genetic variation in clinical and population-scale genomics. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van der Auwera GA, O’Connor BD.. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22(3):568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sondka Z, Bamford S, Cole CG, et al. The COSMIC cancer gene census: describing genetic dysfunction across all human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(11):696–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mikhail FM, Biegel JA, Cooley LD, et al. Technical laboratory standards for interpretation and reporting of acquired copy-number abnormalities and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity in neoplastic disorders: a joint consensus recommendation from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC). Genet Med. 2019;21(9):1903–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2017;19(2):249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller DT, Lee K, Chung WK, et al. ; ACMG Secondary Findings Working Group. ACMG SF v3.0 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23(8):1381–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gröbner SN, Worst BC, Weischenfeldt J, et al. ; ICGC PedBrain-Seq Project. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature. 2018;555(7696):321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiala EM, Jayakumaran G, Mauguen A, et al. Prospective pan-cancer germline testing using MSK-IMPACT informs clinical translation in 751 patients with pediatric solid tumors. Nat Cancer. 2021;2:357–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byrjalsen A, Hansen TVO, Stoltze UK, et al. Nationwide germline whole genome sequencing of 198 consecutive pediatric cancer patients reveals a high incidence of cancer prone syndromes. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(12):e1009231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parsons DW, Roy A, Yang Y, et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):616–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oberg JA, Glade Bender JL, Sulis ML, et al. Implementation of next generation sequencing into pediatric hematology–oncology practice: moving beyond actionable alterations. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller KE, Wheeler G, LaHaye S, et al. Molecular heterogeneity in pediatric malignant rhabdoid tumors in patients with multi-organ involvement. Front Oncol. 2022;12:932337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ronsley R, Boué DR, Venkata LPR, et al. An unusual case of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor, initially diagnosed as atypical pituitary adenoma in a 13-year-old male patient. Neurooncol. Adv. 2022;4(1):vdac121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abdelghani E, Schieffer KM, Cottrell CE, Audino A, Zajo K, Shah N.. Alterations in pediatric malignancy: a single-institution experience. Cancers. 2023;15(6):1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider K, Zelley K, Nichols KE, Garber J.. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Durno C, Boland CR, Cohen S, et al. Recommendations on surveillance and management of biallelic mismatch repair deficiency (BMMRD) Syndrome: a consensus statement by the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(5):836–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lodi M, Boccuto L, Carai A, et al. Low-grade gliomas in patients with noonan syndrome: case-based review of the literature. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(8):582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Villani A, Greer MLC, Kalish JM, et al. Recommendations for cancer surveillance in individuals with RASopathies and other rare genetic conditions with increased cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(12):e83–e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schieffer KM, Varga E, Miller KE, et al. Expanding the clinical history associated with syndromic Klippel–Feil: a unique case of comorbidity with medulloblastoma. Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62(8):103701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wimmer K, Rosenbaum T, Messiaen L.. Connections between constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome and neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin Genet. 2017;91(4):507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wimmer K, Kratz CP, Vasen HFA, et al. ; EU-Consortium Care for CMMRD (C4CMMRD). Diagnostic criteria for constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome: suggestions of the European consortium “care for CMMRD” (C4CMMRD). J Med Genet. 2014;51(6):355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aronson M, Colas C, Shuen A, et al. Diagnostic criteria for constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD): recommendations from the international consensus working group. J Med Genet. 2022;59(4):318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Das A, Sudhaman S, Morgenstern D, et al. Genomic predictors of response to PD- inhibition in children with germline DNA replication repair deficiency. Nat Med. 2022;28(11):125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li MM, Chao E, Esplin ED, et al. ; ACMG Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee. Points to consider for reporting of germline variation in patients undergoing tumor testing: a statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2020;22(7):1142–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Else T, Greenberg S, Fishbein L.. Hereditary paraganglioma–pheochromocytoma syndromes. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. , eds. GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dubard Gault M, Mandelker D, DeLair D, et al. Germline SDHA mutations in children and adults with cancer. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2018;4(4):a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Filpo G, Cilotti A, Rolli L, et al. SDHx and non-chromaffin tumors: a mediastinal germ cell tumor occurring in a young man with germline SDHB mutation. Medicina. 2020;56(11):561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Galera-Ruiz H, Gonzalez-Campora R, Rey-Barrera M, et al. W43X SDHD mutation in sporadic head and neck paraganglioma. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2008;30(2):119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yue X, Liu B, Han T, et al. A novel germline gene mutation and co-occurring somatic activating mutation in a patient with pediatric central nervous system germ cell tumor: case report. Front Oncol. 2022;12:835220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Begemann M, Waszak SM, Robinson GW, et al. Germline mutations predispose to pediatric medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.