Abstract

Pausing of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) at transcription start sites (TSSs) primes target genes for productive elongation. Coincidentally, DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) enrich at highly transcribed and Pol II–paused genes, although their interplay remains undefined. Using androgen receptor (AR) signaling as a model, we have uncovered AR-interacting protein 4 (ARIP4) helicase as a driver of androgen-dependent transcription induction. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing analysis revealed that ARIP4 preferentially co-occupies TSSs with paused Pol II. Moreover, we found that ARIP4 complexes with topoisomerase II beta and mediates transient DSB formation upon hormone stimulation. Accordingly, ARIP4 deficiency compromised release of paused Pol II and resulted in R-loop accumulation at a panel of highly transcribed AR target genes. Last, we showed that ARIP4 binds and unwinds R-loops in vitro and that its expression positively correlates with prostate cancer progression. We propose that androgen stimulation triggers ARIP4-mediated unwinding of R-loops at TSSs, enforcing Pol II pause release to effectively drive an androgen-dependent expression program.

Transcription coactivator ARIP4 promotes androgen-dependent transcription induction through its R-loop unwinding activity.

INTRODUCTION

Spatial-temporal dynamics of transcription machineries on chromatin underlies timely induction of gene expression programs. One feature of transcription entails the pausing of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) at promoter proximal regions: Pol II begins RNA synthesis for ~30 to 50 base pair (bp), pauses, and awaits activation before entering a productive elongation stage (1, 2). Occupancy of the elongation-competent transcription machinery at transcription start site (TSS) regions also prevents nucleosome reassembly and DNA decondensation (2, 3). Together, this ensures swift and coordinated expression of genes responsive to specific cellular cues.

One example of transcription induction is androgen receptor (AR) signaling. Accordingly, human prostate cancer is driven by the activation of the AR signaling pathway to sustain growth and promote pathogenesis (4). As AR signaling is induced by androgens, prostate cancers are mainly treated with androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate cancers frequently harbor oncogenic gene fusions between the androgen-driven transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and the proto-oncogene ETS-related gene (ERG) (5), chromosomal aberration events that have been proposed to result from misrepair of androgen-induced DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (6). Counterintuitively, although DSBs at active genes may disrupt progression of the transcription machinery, transcription activation has been reported to trigger formation of DSBs at regulatory regions of genes (7). Similarly, estrogen receptor signaling activation by estradiol also led to topoisomerase II beta (TOP2β) accumulation at promoter regions of target genes, where it generates DSBs during its catalytic cycle to stimulate poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) activity that promotes chromatin reorganization events to support transcription activation (7).

Notably, not only has formation of DSBs been observed upon stimulus-induced transcription through hormones (6–9), neurotransmitters (10, 11), heat shock, and serum (12), but DSBs are also evident at promoter proximal regions under steady-state transcription (13, 14). Recently, these DSBs have been attributed to the release of paused Pol II (13). As such, promoter proximal regions appear to be a nexus where Pol II pauses, DSBs form, and cotranscriptional R-loops arise. However, how these processes are related to one another and how they affect transcription output are unclear. Notably, pausing of Pol II is a major source of R-loops, which are formed from the hybridization of the short RNA strand nascently synthesized by the paused Pol II molecule and the DNA template. The nascent RNA is stabilized by the paused transcription machinery, and the negative supercoiling at the nucleosome-depleted region creates a conducive chromatin environment for R-loop formation (15, 16). However, because of the frequency and abundance of promoter proximal R-loops, timely resolution of these R-loops is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity by suppressing replication stress as R-loops can act as roadblocks for the replication machinery (17). Deficiencies in R-loop processing factors leads to accumulation of R-loops at the promoter proximal region, dysregulation of Pol II pause release, and subsequent replication-dependent DNA damage (18–22).

In this study, we show that the AR coactivator AR-interacting protein 4 (ARIP4) (23–26) plays a part in androgen-dependent DSB formation and transcription induction. Originally identified as an SNF2 helicase family of chromatin remodelers, ARIP4 binds and hydrolyses adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the presence of DNA, although the helicase showed no remodeling activity under conditions tested (27). Here, we found that ARIP4 enriches at the TSS of genes with paused Pol II where promoter proximal R-loops are formed. Our findings suggest that ARIP4 enforces androgen-dependent Pol II progression, at least in part, by preventing the accumulation of promoter proximal R-loops of a panel of highly expressed AR target genes.

RESULTS

ARIP4 promotes androgen-dependent induction of AR target genes

Prostate cancers depend on AR signaling for growth and survival. In some cases, however, androgen-deprived prostate cancers develop independence toward androgens, transforming into aggressive castration-resistant prostate cancer (28). These androgen-deprived prostate cancers can restore AR signaling by intratumorally synthesizing androgens and by evolving androgen-independent signaling activation. They can also transform AR itself (amplification/overexpression, gain-of-function mutations, or constitutively active AR variants) and by dysregulating transcription coactivators or corepressors of AR-mediated transcription (29).

As ARIP4 was previously identified as an AR coactivator, we first examined if ARIP4 may contribute to aberrations in AR signaling and prostate cancer malignancies. Tumor microarray (TMA) derived from prostatectomy and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) specimen were stained with anti-ARIP4 antibodies (Fig. 1A). ARIP4 staining intensity was scored qualitatively on a 0 to 3 scale. Consistently, specimen of prostatic adenocarcinoma compared to adjacent normal prostatic tissue showed elevated ARIP4 expression (Fig. 1B). When TMA samples were graded by Gleason scores, ARIP4 expression is significantly up-regulated at later stages of prostate cancer cases (Gleason scores 8 to 10) (Fig. 1C). Together, these observations suggest that not only ARIP4 is up-regulated in tumor tissue but also ARIP4 expression is positively correlated with advanced staging of prostate cancer. Moreover, in the androgen-sensitive, AR-positive prostate cancer cell line LNCaP, ARIP4 promoted cell resistance from ionizing radiation (fig. S1, A to C). As activation of AR signaling underlies prostate cancer survival and advancement, we were prompted to investigate the role of ARIP4 as a putative positive regulator of AR signaling.

Fig. 1. ARIP4 enforces androgen-dependent induction of AR target genes.

(A) Representative images of different ARIP4 expression levels (scored 0 to 3) in normal prostatic tissue and prostate cancer TMA sections. (B) Quantification of ARIP4 staining scores in primary prostate tumor and paired nontumor tissue (n = 100). (C) Quantification of ARIP4 staining scores from prostatectomy and TURP TMA of various Gleason scores (total n = 160) compared to benign prostatic tissue of noncancer patients (n = 19). Data are presented as means ± SD. (D) mRNA expression of ARIP4 in ARIP4-depleted RNA-seq datasets. sgControl indicates cells expressing empty vector control, while sgARIP4-1 and sgARIP4-2 are ARIP4-depleted cells expressing CRISPR-Cas9 and two distinct sgRNAs targeting ARIP4. (E) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes with and without androgen (R1881) (P-adjusted < 0.05) in WT (sgControl) LNCaP cells. (F) Box and whisker plots of fold induction of AR target gene expression upon 1 nM R1881 treatment with and without ARIP4.

While ARIP4 was previously reported to encode an AR coactivator, its role in transcription activation was examined in AR-independent cells that ectopically expressed AR and an AR-responsive reporter cassette (23, 24, 27). To elucidate ARIP4 activity under AR signaling-dependent conditions, we conducted a transcriptome analysis of ARIP4-depleted LNCaP cells (Fig. 1D and fig. S2A). To identify genes that ARIP4 might coactivate, a differential gene expression analysis between R1881 (synthetic androgen) and EtOH (ethanol; vehicle control) was conducted to obtain a list of androgen up-regulated AR target genes (n = 245) (Fig. 1E). We also included a random list of genes (n = 245) that matched AR target genes by expression level at uninduced states in wild-type (WT) cells (sgControl) treated with EtOH (fig. S2, B and C). These expression-matched genes had similar expression levels to uninduced AR gene expression but are not sensitive to R1881 treatment (fig. S2B).

Transcriptome analysis revealed that androgen-dependent stimulation of AR target genes was attenuated in ARIP4-deficient cells when compared to their WT isogenic counterparts (Fig. 1F and fig. S2C), although no statistical significant difference in their expression was observed (fig. S2B). Notably, our observation that the expression matched genes did not rely on ARIP4 (fig. S2C) is supportive of the notion that ARIP4 participates in the AR signaling pathway. Androgen-driven AR target genes include secreted proteins [kallikrein related peptidase 2 (KLK2) and 3 (KLK3); markers for prostate cancer screening and prognosis (30, 31)], proto-oncogenes {TMPRSS2 when fused with ERG (5) and growth factors [insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (32)]}, modulators of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and Notch signaling [FKBP5 (33) and JAG1 (34)], and transcription factors/tumor suppressors [NK3 Homeobox 1 (NKX3.1) (35, 36), ZBTB10 (37), and ZBTB16 (38)]. Together, many AR target genes affected by loss of ARIP4 have been shown to promote prostate cancer growth, survival, and advancement (39, 40), corroborating the important role of ARIP4 in conferring survival advantage (fig. S1, A to C) and in driving progression of prostate cancer (Fig. 1, A to C). To explore a broader role of ARIP4 in transcription regulation, we also performed gene ontology analyses on genes with perturbed expression following ARIP4 inactivation (fig. S2, D and E). Accordingly, we found that loss of ARIP4 appears to compromise diverse biological processes, most notably those involving DNA replication and chromosome segregation, in line with recent studies reporting a role of ARIP4 in preserving genome integrity (41, 42).

ARIP4 is enriched at promoter proximal regions

Our data support the idea that ARIP4 encodes a bona fide coactivator of AR signaling, but exactly how ARIP4 mechanistically promotes androgen-dependent transcriptional induction is unknown. To this end, we sought to determine chromatin occupancy of ARIP4. We generated cells that stably express doxycycline (Dox)-inducible ARIP-Flag (TRE-ARIP4-Flag; fig. S3A) and performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experimentations using monoclonal anti-Flag antibodies. Uninduced cells were used as a negative control. Our analysis revealed that ARIP4 enriched around promoter proximal regions with a strong peak immediately downstream of TSSs (Fig. 2, A to C, and fig. S3, B and C). For instance, ARIP4 peaks are mapped to the TSS regions of AR target genes TMPRSS2 and NKX3.1 (Fig. 2B). Considering that ARIP4 encodes a coactivator of AR signaling, we anticipated an increase in ARIP4 occupancy at TSSs after androgen stimulation. Unexpectedly, ARIP4 appears to occupy TSSs (Fig. 2A) and promoter proximal regions (Fig. 2C) genome-wide regardless of androgen stimulation.

Fig. 2. ARIP4 is enriched at promoter proximal regions.

(A) Heatmap of ARIP4 ChIP-seq peaks from LNCaP cells expressing Dox inducible ARIP4 (TRE-ARIP4-SFB) stimulated with androgens (1 nM R1881 for 5 hours) or ethanol (EtOH) control. Left: ARIP4 enrichment at AR genes (n = 245). Right: ARIP4 enrichment at non-AR genes (n = 12,551). (B) Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) display of ARIP4 ChIP-seq enrichment (in RPKM) at AR target genes TMPRSS2 and NKX3.1. Independent replicates are denoted as T1 to T3. (C) Genome-wide distribution of ARIP4 ChIP-seq peaks relative to TSS at all genes with and without androgen treatment. (D) List of ARIP4 copurifying proteins from tandem affinity purification of ARIP4 protein complexes harvested from HEK293T cells. (E) Representative Western blot showing immunoprecipitation (IP) experiment by streptavidin pull-down of SFB-ARIP4 (with SFB-vector as a negative control) transiently transfected HEK293T cells, immunoblotted (IB) against indicated antibodies. (F) Average enrichment of ARIP4, chromatin features (histone marks and open chromatin regions), and ARIP4-interactors (TOP2A, TOP2B, PARP1, and DYRK1A) relative to TSS. Metaplots were generated from publicly available ChIP-seq data (see table S3 for details).

ARIP4 associates with TOP2β and transcription machinery components

To further explore how ARIP4 regulates transcription induction, we asked if ARIP4 associates with proteins involved in transcriptional processes. To this end, we stably expressed streptavidin-binding peptide–Flag–S protein-tagged (SFB) ARIP4 in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and purified ARIP4 protein complexes. Mass spectrometry analysis of ARIP4 copurifying proteins uncovered TOP2α and TOP2β as top interacting partners (Fig. 2D). DYRK1A, a known and previously validated binding partner of ARIP4 (24), also appeared as a top hit. We first validated that ARIP4 associates with TOP2β and PARP1 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2E). Because ARIP4 resides predominantly around the TSS (Fig. 2, A and F), we asked if its interacting partners may also occupy overlapping regions in the genome. By comparing with publicly available datasets, ARIP4 peaks appear to overlap with those of DYRK1A, PARP1, TOP2α, and TOP2β but not TOP1. ARIP4 peaks overlap with accessible chromatin marks [ATAC, deoxyribonuclease I, and RPB1 (largest subunit of Pol II)] and are flanked by H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 peaks (Fig. 2F), implying that ARIP4 occupies the nucleosome-depleted promoter proximal regions.

Moreover, by analyzing prostate cancer patient samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) database, we found that ARIP4 expression positively correlated with those of AR and TOP2β but not TOP2α (fig. S4A). Prostate cancer samples with TMPRSS2:ERG fusions also tend to have elevated TOP2β and ARIP4 levels (fig. S4, B to D). Collectively, these findings suggest that ARIP4 may promote transcription in association with TOP2β.

ARIP4 promotes transcriptional induction in reporter cells

Seeing that ARIP4 also occupies TSS of non-AR genes (Fig. 2A), we next asked if ARIP4 may also regulate the induction of AR-independent gene expression. To this end, we used a reporter cell line that enables the visualization of nascent transcription upon the addition of Dox. The U2OS DSB-induced silencing in cis (DISC) reporter cells developed by the Greenberg group (43) (Fig. 3A) contains a tetracycline response element (TRE), where, in the presence of Dox, it drives the expression of MS2 transcripts. When yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)–tagged MS2 is expressed, the YFP-MS2 protein binds to the MS2 stem-loop structure, forming a discernible focus (YFP−MS2+). As such, induction of transcription by Dox enables in situ visualization of nascent transcript formation at the chromosomal position of the integrated transgene (Fig. 3B). Hence, this reporter system is a useful tool that enables the direct observation of inducible transcription in single cells. The DISC reporter cassette also contains a LacO array, allowing the expression of mCherry–Lac I to track the position of the transgene (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. ARIP4 enforces transcriptional induction in reporter cells.

(A) Schematic representation of the U2OS DISC reporter system. The U2OS DISC reporter (U2OS 263) cell line stably expresses YFP-tagged MS2 protein. Dox treatment (+Dox) induces the expression of the MS2 mRNA (stem-loop structure), which is recognized by the YFP-MS2 protein (green). The reporter also contains LacO repeats, which are recognized by mCherry–Lac I (red). (B) Representative images of DISC reporter cells. (Left) Without Dox, YFP-MS2 is evenly distributed in the nucleus. mCherry–Lac I (red dot) recognizes the LacO array, denoting the reporter cassette (arrowhead). (Right) Upon Dox addition, nascently transcribed MS2 mRNA is recognized by YFP-MS2, forming a bright green dot at the reporter cassette (arrowhead). (C) Representative time-lapse images of a Dox-induced reporter cell expressing mCherry-ARIP4. Arrowheads indicate the position of the reporter locus. (D) Immunofluorescence images of Dox-induced reporter cells upon depletion of ARIP4. (E) Representative Western blot of ARIP4-depleted DISC reporter cells used in (D). (F) Quantification of nascent transcription marked by YFP-MS2 accumulation (YFP−MS2+) upon ARIP4 depletion of data represented in (D). (G) Immunofluorescence images of ARIP4-depleted Dox-induced reporter cells reconstituted with gRNA-2–resistant WT and helicase-dead (DE462/463AA and K310A) mutants of V5-ARIP4-3XFLAG. (H) Quantification of nascent transcription marked by YFP-MS2 accumulation upon ARIP4 reconstitution shown in (G). (I) Immunofluorescence images of Dox-induced reporter cells treated with TOP2 inhibitors (TOP2i). Cells were pretreated with 25 μM etoposide or 50 μM merbarone for 4 hours before Dox treatment for an additional 4 hours. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. (J) Quantification of nascent transcription marked by YFP-MS2 accumulation upon TOP2i. (K) Immunofluorescence images of Dox-induced reporter cells treated with indicated siRNAs. Cells were harvested at least 48 hours after siRNA treatment and 4 hours after Dox treatment. (L) Quantification of nascent transcription marked by YFP-MS2 accumulation upon indicated siRNA treatment.

When mCherry-ARIP4 is expressed in these reporter cells, we observed robust accumulation of ARIP4 signals at the transgene locus. ARIP4 recruitment appears to precede detectable formation of nascent MS2 transcripts (Fig. 3C), which is in agreement with observations derived from ChIP sequencing (ChIP-seq) experimentations in LNCaP cells (Fig. 2A). We speculate that ARIP4 might act as a priming factor for active genes to enable optimal induction of transcription. ARIP4 inactivation suppressed formation of YFP-MS2 focus in reporter cells, indicating that production of nascent MS2 transcripts is significantly compromised (Fig. 3, D to F). As ARIP4 is a putative helicase, we next asked if the catalytic activity of ARIP4 is involved in its role as a transcription regulator. To this end, we expressed ARIP4 WT and its helicase-inactive mutants (DE462/463AA and K310A) in ARIP4-depleted cells and monitored nascent MS2 transcription. Upon reconstitution of ARIP4-depleted cells with WT ARIP4, MS2 transcription is restored to normal levels (Fig. 3, G and H). On the other hand, helicase-dead mutants of ARIP4 failed to alleviate the defect in transcriptional induction in ARIP4-depleted cells (Fig. 3, G and H). To rule out deficiencies in recruitment to the transgene, we verified that ARIP4 mutants are enriched at the transgene to a similar extent as its WT counterpart (fig. S5, A and B). Together, these results suggest that ARIP4 catalytic activity is crucial in promoting transcriptional induction.

To examine if the DISC reporter cells require TOP2β activity to enforce transcriptional induction, we pretreated cells with small molecules that target TOP2β at different stages of its catalytic cycle, including merbarone, which inhibits TOP2 upstream of the DNA cleavage step, and etoposide, which traps TOP2 on the DNA downstream of the DNA cleavage step (44). When transcription is induced, only the merbarone-treated cells, but not etoposide-treated cells, failed to produce normal levels of nascent transcripts (Fig. 3, I and J), suggesting that induction of transcription is not perturbed by TOP2 inhibition per se but depends on DSB generating activity of TOP2. As merbarone acts on both TOP2α and TOP2β, we depleted TOP2α, TOP2β, and PARP1 to further evaluate their requirement in transcription induction (fig. S6A). Accordingly, transcription is down-regulated upon depletion of TOP2β and PARP1 but not TOP2α (Fig. 3, K and L). Notably, attenuated transcriptional induction in TOP2i- and PARP inhibitor–treated cells is independent of ARIP4 recruitment to transgene as TOP2 and PARP inhibition do not noticeably affect ARIP4 recruitment to the reporter cassette locus (fig. S6, B and C).

ARIP4 is necessary for androgen-inducible breaks at the promoter proximal region

Accumulating evidence has shown that TOP2β is essential for promoting transcription. Upon transcription induction by external stimuli, TOP2β is recruited to target gene promoters to generate transient DSBs, which is essential to support transcription output (6–10, 12). It was proposed that transient formation of DSBs could be a detectable by-product of TOP2β catalytic activity, which involves DSB formation, strand passage, and religation to resolve DNA topological constraints generated upon normal biological processes, e.g., advancement of the transcription machinery (45, 46). Previous studies have also shown that transcription stimulation is also followed by the recruitment of DNA damage factors such as PARP1 (7, 9, 13), DNAPk (7, 12), Ku70/80 (7, 12), ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) (6), and phospho-KAP1 (12). PARP1 has been proposed to promote a permissive chromatin environment for transcription upon TOP2β-induced DSBs (7). However, how the other DNA damage factors participate in repair or chromatin remodeling events to support transcriptional induction is unknown.

Despite the notion that these DSBs are indispensable for transcriptional induction (10, 12) and are believed to be “physiological” or “scheduled,” these DSBs have been demonstrated to be a source of genomic instability. Particularly, upon the addition of androgen, misrepaired DSBs generated by AR-activated TOP2β results in oncogenic fusions between the AR target gene TMPRSS2 and the proto-oncogene ERG (6). Furthermore, TMPRSS2:ERG fusions are extremely frequent in prostate cancers (5) and contribute to androgen independence in advanced prostate cancers (47). Prompted by the possibility that ARIP4 may promote transcription via TOP2β (Fig. 2D and fig. S4), to test if ARIP4 mediates transcriptional induction in a manner that requires DSB induction in LNCaP cells, we used a previously established biotin–deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) break labeling method (7). Briefly, isolated nuclei were incubated in a reaction containing terminal transferase (TdT) enzyme in the presence of biotin-labeled dUTP to label DNA breaks with biotin, which is then processed for ChIP with anti-biotin antibody. We first verified that induction of transcription with hormones resulted in detectable break formation. With 1 nM R1881, breaks are formed at 20 min and are resolved within 30 min at the enhancer, promoter, and TSS regions of AR target genes KLK3 and TMPRSS2 (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4. ARIP4 is necessary for androgen-dependent break formation at promoter proximal regions of AR target genes.

(A) (Top) Schematic of AR target genes KLK3 and TMPRSS2 and target regions used for break labeling ChIP-qPCR amplification. (Bottom) Break labeling assay upon 1 nM R1881 treatment at indicated time points (0 to 30 min). Biotin-dUTP incorporated into breaks formed upon androgen treatment was immunoprecipitated against immunoglobulin G (IgG) (negative control) or anti-biotin antibody. (B) Break labeling assay of ARIP4-depleted LNCaP cells. (C) Break labeling assay upon TOP2i and ARIP4 depletion. LNCaP cells were cultured in charcoal-stripped FBS for at least 48 hours and treated with merbarone (50 μM) for 4 hours prior to R1881 stimulation. (D) Break labeling assay upon flavopiridol (FP) and wash out (FP+wash) treatment as depicted in fig. S7F was conducted at indicated time points after 1 nM R1881 stimulation.

ARIP4 inactivation hampered DSB formation at the tested time points after hormone induction (Fig. 4B and fig. S7A). We speculated that the lack of break formation implies that ARIP4 acts upstream of TOP2β and the break formation event. Inhibition of TOP2 with merbarone with ARIP4 inactivation did not further attenuate androgen-dependent break formation (Fig. 4C and fig. S7B). It is noteworthy to mention that LNCaP cells were cultured in charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS)-supplemented medium prior to R1881 treatment and had negligible TOP2α expression (fig. S7C).

Recently, the scheduled, physiological DSBs have been proposed to be correlated with pausing of RNA Pol II at TSS regions (13, 14). To determine if AR target genes KLK3 and TMPRSS2 are paused genes, we took into account Pol II occupancy at TSS over its corresponding gene body and calculated the pausing index (PI) (fig. S7D). By analyzing publicly available datasets, we confirmed that both KLK3 and TMPRSS2 are paused genes (PI > 2; fig. S7E). To interrogate how Pol II pausing affects DSB formation, we used flavopiridol, a potent but reversible inhibitor of transcription that inactivates P-TEFb and prevents Pol II pause release and subsequent elongation (48). We first confirmed that, by 5-ethynyl uridine (5-EU) incorporation, flavopiridol treatment efficiently suppressed nascent transcription and that specific wash out and recovery conditions allowed restoration of nascent transcription (fig. S7F). Cells that received the above-described drug treatment were then subjected to the break labeling assay. Untreated cells show timely break formation, while breaks were not detected in flavopiridol-treated cells (Fig. 4D). When flavopiridol is washed out and Pol II is allowed to be released and proceed into elongation, breaks were reestablished (Fig. 4D). Together, these observations led us to propose that the Pol II pause release event, and not the pausing of Pol II, generates breaks. In line with previous findings during steady-state transcription (13), we concluded that androgen-dependent break formation also occurs as a consequence of Pol II pause release. As the lack of break formation in ARIP4-depleted cells phenocopies Pol II pause release–suppressed cells, we speculate that ARIP4 could regulate transcriptional induction through events involving release of paused Pol II.

ARIP4 preferentially associates with paused genes

To further corroborate that ARIP4 is important for Pol II pause release, we first verified that ARIP4 physically interacts with Pol II in LNCaP cells (Fig. 5A). As ARIP4 is enriched at TSS regions, we asked if ARIP4 occupancy at TSSs depends on whether or not Pol II is paused. By using publicly available datasets of Pol II occupancy in LNCaP cells (49), genes were separated into three groups: genes with paused Pol II (PI > 2), genes with nonpaused Pol II (PI ≤ 2), and genes with no Pol II occupancy. PIs were calculated as reported by Day et al. (50) (fig. S7D). Consistently, ARIP4 preferentially occupies TSS of paused genes over genes without Pol II and nonpaused genes (Fig. 5B), further supporting the idea that ARIP4 plays a role in transcription induction of paused, DSB-prone genes.

Fig. 5. ARIP4 suppresses R-loop accumulation at promoter proximal regions of a subset of highly expressed AR target genes.

(A) Representative Western blot showing immunoprecipitation experiment by streptavidin pull-down of ARIP4-SFB in LNCaP cells stably expressing TRE-ARIP4-SFB immunoblotted against indicated antibodies. (B) Metaplots of Pol II and ARIP4 at the TSS of paused (PI > 2), nonpaused (PI ≤ 2), and no Pol II genes. (C) IGV display of Pol II ChIP-seq of ARIP4-depleted LNCaP cells at KLK3, KLK2, and ACTB. RPKM values denote the read count TSS ± 500 bp. (D) Distribution of PI values of AR target genes with and without ARIP4 (n = 216). (E) Distribution of TRs of AR target genes upon R1881 treatment with and without ARIP4 (n = 216). TR denotes the fold change in PI upon R1881 treatment. Statistical significance was determined by paired Student’s t test. (F) Metaplots of PRO-seq and R-loops at the TSS of paused, nonpaused, and no Pol III genes. (G) Metaplot of ARIP4 ChIP-seq with respect to S9.6 CUT&Tag peaks. (H) Metaplot of Pol II ChIP-seq and S9.6 CUT&Tag peaks at the TSS of all genes. (I) IGV display of S9.6 CUT&Tag profiles at AR target genes KLK2 and KLK3. RPKM values denote the read count TSS ± 500 bp. (J) Scatterplots of the fold change in R-loop read coverage (TSS ± 500 bp) in ARIP4-depleted versus WT cells (sgARIP4/sgControl). Fold changes > 1 in both sgARIP4-1 and sgARIP4-2 are referred to as genes that are dependent on ARIP4 for R-loop resolution (ARIP4dependent). Genes that do not show consistent increase (fold change < 1) are referred to as ARIP4independent genes. (K) Comparison of PIs of ARIP4dependent versus ARIP4independent AR target genes. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (L) Comparison of gene expression levels of ARIP4dependent versus ARIP4independent AR target genes. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

To experimentally interrogate if ARIP4 modulates Pol II pause release, we conducted ChIP-seq experimentation against the Pol II holoenzyme (anti-RPB1) in control and ARIP4-depleted LNCaP cells (fig. S8A). As we were most interested in androgen-induced transcription, we compared the occupancy of Pol II with and without R1881 treatment and observed notable up-regulation of Pol II occupancy in the gene body of paused AR target genes, including KLK2 and KLK3, after R1881 treatment (Fig. 5C). On the contrary, the non-AR target gene ACTB did not show any Pol II occupancy change before and after R1881 treatment. Moreover, PI values of KLK2 and KLK3 upon androgen stimulation were higher in ARIP4-deficient cells as compared to control, suggesting that ARIP4 may be important in promoting transcription elongation.

As PI values reflect the degree of elongation by quantifying the proportion of Pol II at the TSS compared to the gene body, we sought to quantify androgen-dependent Pol II pause release. To this end, we determined the traveling ratio (TR) of the panel of AR genes in control and ARIP4-deficient cells (fig. S8B). TR was calculated by dividing the PI after R1881 by the PI before R1881 (EtOH) and is reflective of Pol II distribution between its paused state at the promoter proximal region (±500 bp flanking the TSS) and its elongating state in the gene body following androgen stimulation. We first filtered out AR genes that have low-to-negligible signal of Pol II at promoter proximal regions, quantified the PI values of the 216 AR genes across all samples (Fig. 5D), and analyzed their TR values (Fig. 5E). Accordingly, in WT cells (sgControl), the average TR is <1, implying that Pol II reads are more abundant in the gene body after R1881 treatment. On the contrary, both ARIP4-depleted cell lines have significantly higher TRs, indicating more abundant Pol II reads at the promoter proximal region (TSS) after R1881 treatment. These findings imply that the ARIP4 deficiency compromised effective Pol II progression into its productive elongating state.

ARIP4 suppresses R-loop accumulation at promoter proximal regions of a subset of highly expressed AR target genes

We next addressed how the enzymatic activity of ARIP4 may participate in transcription regulation. Given that ARIP4 mainly occupies TSSs, particularly at nucleosome-depleted domains (Figs. 2F and 5B), we considered the possibility that ARIP4 may act on nucleic acid substrates, specifically Pol II pausing–associated R-loops.

Several lines of evidence suggest that most cotranscriptional R-loops detected at TSS regions are consequential to Pol II pausing (16, 51). At the same time, R-loops have been shown to play a role in regulating transcription. It is well established that resolution of R-loops at transcription end sites is necessary for proper transcriptional termination and subsequent normal transcript levels (52–54), and recently, the same notion translates to promoter proximally paused R-loops at TSS regions (55, 56). In vitro, it has been shown that promoter proximal R-loops may also constitute physical barriers for subsequent rounds of transcription (57), implying that R-loop resolution at the promoter proximal region has direct consequences on transcription output.

ARIP4 harbors a DExD/H helicase motif commonly found in many RNA helicases like DExH-Box Helicase 9 (DHX9), and DEAD-box helicases DDX1, DDX5, and DDX21, all of which have previously been characterized as R-loop regulators (53, 58–64). We hypothesize that androgen-responsive genes dependent on ARIP4 for optimal induction would hyperaccumulate pausing-associated R-loops upon ARIP4 inactivation. To this end, we performed CUT&Tag using the S9.6 antibody in ARIP4-depleted LNCaP cells, followed by sequencing according to a recently published method (65). In tandem to S9.6 CUT&Tag, the same samples were also processed for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) for a parallel representation of the transcriptomic landscape in cells used for R-loop profiling. Because of the smaller number of replicates, we singled out 142 AR target genes that were significantly up-regulated upon R1881 treatment and were able to reproducibly document defective androgen-dependent expression in ARIP4-depleted cells (fig. S8C). Consistently, this list of 142 AR genes also showed defective Pol II pause release upon R1881 addition (fig. S8, D and E).

We verified that the R-loop profiles detected in LNCaP cells generated in this study are consistent with published R-loop CUT&Tag profiles in HEK293T cells (fig. S8F) (51). Furthermore, these promoter proximal R-loop signals are preferentially enriched at paused genes (Fig. 5F, S9.6 CUT&Tag), which likely resulted from nascent transcripts found at paused genes (Fig. 5F, PRO-seq). We also verified that ARIP4 occupies R-loop forming promoter proximal regions (Fig. 5G), which likely flanks R-loop hotspot together with Pol II (Fig. 5H).

As we hypothesize that ARIP4 may resolve R-loops, we envisage that depletion of ARIP4 would lead to an accumulation of R-loops, particularly at promoter proximal regions (±500 bp of TSS). While ARIP4 deficiency appears to have negligible effect on pausing-associated R-loops genome-wide (fig. S8G) and across all AR genes (fig. S8H), when assessing individual genes, e.g., AR target genes KLK2 and KLK3, we noted that ARIP4 inactivation resulted in hyperaccumulation of R-loops at promoter proximal regions (Fig. 5I). Hence, we set out to pinpoint the AR genes that are sensitive to ARIP4 loss to identify features these genes have that render them more susceptible to hyperaccumulating pausing-associated R-loops in the absence of ARIP4. We classified genes that have elevated levels of R-loops in the absence of ARIP4 (denoted as ARIP4dependent) and compared them with genes that do not accumulate R-loops in the absence of ARIP4 (denoted as ARIP4independent; Fig. 5J).

Overall, ARIP4 appears to modulate R-loops differentially, not unlike what was observed in DRIP-seq (DNA-RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing) results of TOP1-depleted cells, where genes that accumulate R-loops (not specific to pausing-associated R-loops), in the absence of TOP1, tend to be longer and more highly expressed compared to those that are not (66). Genes classified as ARIP4dependent did not appear to have significantly different lengths (fig. S8I). ARIP4 occupancy at the promoter proximal region per se also did not determine R-loop levels (fig. S8J). We found marked reduction in the PI of ARIP4dependent genes but not that of ARIP4independent genes, following androgen treatment (Fig. 5K), suggesting a link of ARIP4-dependent R-loop resolution to gene expression. Genes that accumulate R-loops in the absence of ARIP4 (ARIP4dependent) appear to be more highly expressed compared to genes that do not rely on ARIP4 for R-loop resolution (ARIP4independent; Fig. 5L). Together, our data point to the idea that ARIP4 suppresses pausing-associated R-loops of a subset of highly expressed AR genes.

To characterize ARIP4dependent genes further, we conducted a gene ontology analysis on the subset of ARIP4dependent and ARIP4independent AR genes (fig. S9, A and B). In terms of biological processes, ARIP4dependent AR genes appear to dominantly play a role in androgen metabolism and biosynthesis. ARIP4independent AR genes appear to participate in processes involved in the skeletal system development, which is not unexpected as AR signaling has previously been implicated in the regulation of male skeletal integrity (67). In terms of molecular function, ARIP4dependent genes mainly bind to nucleotides/nucleosides, while ARIP4independent AR genes bind to enzymes. ARIP4independent genes also participate in PI3K signaling, while ARIP4dependent AR genes act as regulators in c-Jun N-terminal kinase (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling, both of which contribute to the growth and advancement of prostate cancer (29). On the basis of these analyses, ARIP4dependent AR genes are likely involved in the primary response to androgens, while ARIP4independent AR genes partake in the signaling cascade and cellular response to androgen.

To assess if ARIP4dependent genes might contribute to prostate cancer advancement, we compared the expression levels of ARIP4dependent and ARIP4independent AR genes in tumor versus normal cases using TCGA PRAD data (fig. S9C). Consistent with our findings (Fig. 5L), ARIP4dependent AR genes tend to be more highly expressed than ARIP4independent AR genes in both normal prostatic tissue and prostate cancer samples. Furthermore, ARIP4dependent AR genes also tend to be more up-regulated in prostate cancer samples compared to normal tissues.

ARIP4 preferentially binds and unwinds R-loops in vitro

Last, to examine if ARIP4 may possess R-loop unwinding activity, we purified ARIP4 from insect cells using previously established conditions (23) (Fig. 6A). First, we sought to examine if ARIP4 has binding capacity toward a panel of nucleic acid structures. To this end, we conducted in vitro binding assays with single-stranded DNA/RNA (ssDNA/ssRNA), double-stranded DNA/RNA (dsDNA/dsRNA), DNA:RNA hybrids, and triple-stranded D-loops and R-loops.

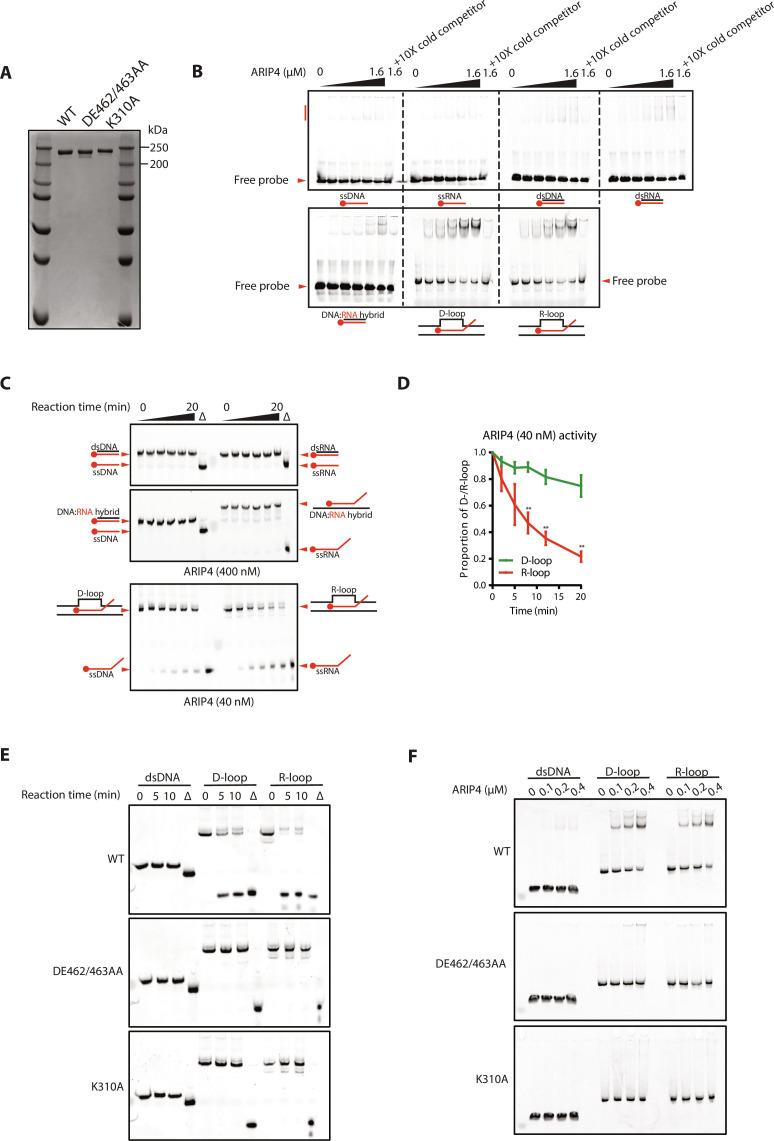

Fig. 6. ARIP4 preferentially binds and unwinds R-loops in vitro.

(A) Purified ARIP4 and ARIP4 helicase mutants used in in vitro assays. (B) In vitro binding assay of increasing concentrations of ARIP4 with indicated nucleic acid structures (30 nM). (C) In vitro unwinding assay of indicated nucleic acid structures (10 nM) in the presence of ARIP4. dsDNA, dsRNA, and DNA:RNA hybrids were incubated with 400 nM ARIP4, while D-loops and R-loops were incubated with 40 nM ARIP4. Δ indicates reactions that were heat denatured as a positive control. (D) Quantification of ARIP4 unwinding activity against D-loops and R-loops by band intensities normalized to band intensity at 0 min. (E) In vitro unwinding assay of indicated nucleic acid structures (10 nM) in the presence of WT or helicase-dead (DE462/463AA and K310A) ARIP4. (F) In vitro binding assay of indicated nucleic acid structures (30 nM) in the presence of WT and helicase-dead (DE462/463AA and K310A) ARIP4.

ARIP4 was previously proposed to be a promiscuous nucleic acid binding protein with little sequence specificity (27). ARIP4 appears to bind to all forms of nucleic acids tested but exhibited preferential binding for substrates with displacement loops, including D-loops and R-loops (Fig. 6B). To investigate which of the substrates ARIP4 may act on, we conducted an in vitro helicase assay with double-stranded DNA/RNA, DNA:RNA hybrids with and without an overhang, and D-loops/R-loops using previously established conditions (27). Even at high concentrations (up to 400 nM), ARIP4 was unable to unwind any of the tested double-stranded nucleic acid structures (Fig. 6C). By contrast, ARIP4 (40 nM) exhibited robust unwinding activity for both D-loops and R-loops, with a preference for the latter (Fig. 6, C and D). The helicase-dead mutants of ARIP4 (DE262/463AA and K310A) that have previously been shown to bind but not hydrolyze ATP (23, 27) were unable to unwind D-loops and R-loops (Fig. 6E) and were also defective in binding to D-loops and R-loops (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, ATP stimulated ARIP4-dependent unwinding of R-loops (fig. S10, A and B) and correspondingly destabilized formation of the ARIP4 and R-loop complexes (fig. S10C).

DISCUSSION

ARIP4 was originally identified as an AR binding partner and coactivator (23), although mechanistically how the helicase drives AR-dependent gene expression has remained undefined. In this study, we uncovered that ARIP4 preferentially binds and unwinds R-loops (Fig. 6), transcription intermediates that have emerging regulatory functions in the chromatin dynamics of the RNA Pol II holoenzyme. Moreover, we show that ARIP4 co-occupies with paused Pol II at promoter proximal nucleosome-depleted regions (Figs. 2F and 5B) and facilitates Pol II pause release and gene transactivation. Together, we propose that ARIP4 resolves R-loops at Pol II pause sites and that Pol II pause release licenses TOP2β-dependent DSB formation to affect transcription (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Working model.

(Top) The promoter proximal region is a nexus where Pol II pauses, R-loops form, DSBs are generated, and ARIP4 is enriched. Androgen-dependent transcriptional induction requires ARIP4 (purple) R-loop unwinding activity at highly transcribed genes. R-loops generated from a paused Pol II (blue) awaiting androgen-dependent signaling can act as physical barriers; hence, R-loop resolution is important in ensuring timely pause release and elongation of subsequent rounds of Pol II (green). (Bottom) Upon pause release cues in the form of androgen signaling activation, progression of the transcriptional machinery distorts the DNA in the form of topological constraints, which are resolved by TOP2β (magenta), where occasional DSBs are formed. This model links R-loop resolution to both Pol II pause release and TOP2β-dependent DSB formation and direct impacts of R-loops on transcriptional output.

Our observations that ARIP4 is endowed with R-loop unwinding activities in vitro (Fig. 6) and that Pol II pausing–associated R-loops at highly transcribed AR target genes were up-regulated in ARIP4-deficient cells (Fig. 5L) are in line with an unprecedented role of ARIP4 in R-loop processing at TSSs in vivo. The notion that unresolved R-loops at promoter proximal regions may constitute physical barriers to the progression of the subsequent units of transcriptional machineries, manifested by attenuated Pol II progression into gene bodies, i.e., elongation state, highlights the ARIP4 helicase as a chromatin-associated activity important for full-blown gene transactivation. Moreover, our findings are highly suggestive that release of paused Pol II is coupled to TOP2β-dependent DSB formation (Fig. 4D and fig. S7A), failing of which hampered androgen-dependent transcriptional induction of AR target genes (Fig. 1F and fig. S8C).

That ARIP4 is enriched at promoter proximal regions of AR target genes prior to androgen stimulation (Fig. 2A) is consistent with our observation in U2OS DISC reporter cells where ARIP4 appears to localize at the transgene before nascent transcription can be detected (Fig. 3C). While it remains to be validated how ARIP4 occupancy at TSSs precedes cellular cues that activate gene transactivation, our data argue against the idea that ARIP4 may be targeted to TSSs via R-loops. While ARIP4 helicase mutants are unable to bind R-loops in vitro, inactivation of ARIP4 helicase activity did not noticeably affect their ability to concentrate at the transgene (fig. S5), indicating that ARIP4 occupancy at its target genes is likely due to protein-protein interaction instead of substrate binding. In support of this idea, Tanner and Linder (68) suggest that DExD/H box RNA helicases typically have low sequence specificity as any sequence specificity will only hinder its unwinding activity. While this working model remains to be definitively tested, given that the ARIP4 interactome consists of various RNA binding proteins (SERBP1, PABPC1, HNRNPM, etc.), components of the 40S/60S ribosomal proteins (RPS2, RPS3, RPL3, RPL4, etc.), and other DExD/H box helicases (e.g., DHX9, DDX1, DDX5, DDX21; see Fig. 2D), we speculate that ARIP4 exists in the transcription machinery macromolecular complex, thus allowing swift and coordinated release of paused Pol II by processing of pausing-associated R-loops.

Our data are indicative that ARIP4 preferentially resolves R-loops at highly transcribed AR target genes (Fig. 5L). As transcription output is a product of many rounds of transcription events, we speculate that strict requirement for R-loop resolution at TSSs may also be highly dependent on the transcription status of specific target genes. Noting that unresolved promoter proximal R-loops have been shown to block subsequent rounds of transcription (57), we believe that highly expressed genes rely more heavily on R-loop resolvers such as ARIP4 to prevent any delay in subsequent rounds of transcription from excessive R-loop formation. It is well known that the presence of R-loops per se is not harmful, but the deregulation of R-loops could pose a threats to genomic integrity (69, 70), highlighting the importance of dynamic homeostatic regulation of R-loop structures (71–73). Together, fine-tuning the levels of pausing-associated R-loops can benefit transcription in different contexts, and exactly how ARIP4 mechanistically supports the presence of R-loops remains to be elucidated.

While ARIP4 inactivation did not lead to global increase in R-loops across AR target genes, our observation is reminiscence to that of the DHX9 helicase. DHX9 deficiency did not alter global levels of R-loops, but on the other hand, it appears to promote the formation of R-loops through resolution of RNA secondary structures under specific cellular context (58). As such, it would be interesting to investigate how ARIP4, as a component of the transcription machinery and alongside other R-loop helicases, e.g., DHX9, is specifically activated to enforce gene transactivation. Moreover, it will also be important to systematically study substrate preferences and specificities of R-loop helicases as ARIP4 appears to be endowed with more robust activity in unwinding certain artificial R-loop structures when compared to DHX9 (fig. S11, A to C), which also does not appear to be important in regulating R-loop levels at ARIP4dependent AR genes (fig. S11, D to F). In summary, our identification and characterization of the ARIP4 helicase as an R-loop resolving activity that enforces gene transactivation by driving Pol II pause release and TOP2β-dependent DSB formation on the local chromatin thus highlight the intricate nature of the dynamic regulation of gene expression. If and how ARIP4 may serve a role as a transcription coactivator beyond AR signaling also warrant further investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient specimens, TMAs, and immunohistochemical staining of ARIP4

Specimens of prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma and adjacent paired normal tissue were obtained from 100 patients who underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy at Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong. Archival dates of the specimen fell between 2005 and 2011. Clinical features of patients were presented in tables below and the Supplementary Materials (table S1 and Tables 1 and 2). All patients were confirmed by clinical and pathological diagnosis. Patient tissue samples with prior hormonal or radiation therapy treatment were excluded. Histological diagnoses were reviewed and graded by pathologist A.H.N.T. using the 2014 version of Gleason grading system (74) and WHO/ISUP (World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology) grade group (75).

Table 1. Tumor Gleason score (2014 update) distribution in patients with prostate cancer.

| Gleason score | Frequency (percentage) |

|---|---|

| 6 | 30 (30%) |

| 7 | 45 (45%) |

| 8 | 10 (10%) |

| 9 | 15 (15%) |

Table 2. Tumor grade group distribution in patients with prostate cancer.

| Grade group | Frequency (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Grade group 1 | 30 (30%) |

| Grade group 2 | 33 (33%) |

| Grade group 3 | 12 (12%) |

| Grade group 4 | 10 (10%) |

| Grade group 5 | 15 (15%) |

Four TMAs were constructed from the 100 specimens. Representative areas (carcinoma and normal tissue) of each specimen were marked by pathologists. Carcinoma component was sampled in triplicate to account for tumor heterogeneity. The study was approved by The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster Institutional Review Board (reference number: UW 20-559). Immunohistochemistry was performed following the product manual and protocol. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed in citrate buffer solution (pH 6) for the paraffin sections (4 μm) from four TMAs. The sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody against ARIP4 (TA349434, Origene) at a 1:100 dilution overnight at 4°C. EnVision+ system–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Dako) was used for visualization according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Staining was revealed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. The staining intensity of ARIP4 was scored by pathologists using the 0 to 3 scale (0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong). The slides were digitalized by the digital slide scanner (NanoZoomer S210, Hamamatsu), and images were captured using the accompanied viewer software (NDP.view2, Hamamatsu). Key characteristics of prostate cancer patient samples are described in table S1.

Cell culture

HEK293T and LNCaP cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. DISC reporter cells (U2OS 263 and 265) were gifted by R. Greenberg (University of Pennsylvania). HEK293T and U2OS 263 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco), while LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI 1640. All cell lines were grown in culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) at 5% CO2 at 37°C. For hormone induction experiments, LNCaP cells are washed with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the medium is replaced with RPMI 1640 containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (Gibco) for at least 48 hours prior to androgen stimulation.

RNA interference

Cells were transfected twice with nontargeting control and target-specific siRNA (Dharmacon) in 24-hour intervals with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were processed further at least 48 hours after the second transfection. Sequences of siRNAs are detailed in table S2.

Genomic editing with CRISPR-Cas9

Gene targeting guide RNAs (gRNAs) were cloned into the lentiCRISPR V2 vector (Addgene, no. 52961) according to standard procedures. Lentiviral packaging was done by transfecting HEK293T cells with lentiCRISPR V2-based gRNA expression plasmid with accompanying helper plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2.G at a ratio of 5:3.75:1.25 with polyethylenimine transfection. At 48 and 72 hours after transfection, lentiviral-containing supernatant was filtered with an Acrodisc 25-mm syringe filter with a 0.45-μm membrane (PALL Life Sciences). To transduce cells, filtered lentiviral supernatant was applied three times to recipient cells in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml) in 24-hour intervals. Transduced cells were then selected in medium containing puromycin (2 μg/ml) for at least 48 hours before verification by Western blotting. Verification of ARIP4 depletion is detected by immunoblotting with anti-ARIP4 antibodies from Bethyl (catalog no. A302-066A). Sequences of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) are detailed in table S2.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blotting

For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, cells were lysed in ice-cold NETN buffer [20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 1 mM EDTA] supplemented with Benzonase nuclease and MgCl2 for 15 min at 4°C with rotation. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at maximum speed at 4°C for 10 min. Streptavidin-conjugated agarose beads was applied into the supernatant and incubated for at least 4 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation. Protein-bound beads were washed three times in NETN buffer before being subjected to Western blotting. For whole cell lysate samples, cells were harvested and lysed on ice for 30 min. Samples were boiled with SDS containing loading buffer and subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Samples were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked with 3% milk in 1X tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 (TBST) for 30 min, and immunoblotted with indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4°C then in HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for at least 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, membranes were incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate and subjected to chemiluminescence imaging. Antibodies used are described in table S2.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells grown on coverslips were subjected to indicated treatments and harvested at indicated time points by fixation in 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 min. Samples were then blocked in 3% milk in 1X TBST for 30 min and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1X TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. Coverslips were washed with 1X PBS to remove excess antibodies and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorophores for 1 hour at room temperature before counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 30 s and mounted onto glass slides with mounting medium (Dako). Samples were visualized, and images were acquired with an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope (UPlanSApo 40×/0.95 objective). U2OS DISC reporter cells were pretreated with indicated inhibitors, and Dox (2 μg/ml) was added to induce nascent transcription for an additional 4 hours. Incidences of nascent transcription was measured by calculating the number of cells with YFP-MS2 “dot” (YFP−MS2+) divided by the total number of cells per treatment in each replicate. Chemicals and antibodies used are described in table S2.

5-EU labeling

Labeling of nascent transcripts was conducted with Click-iT RNA Alexa Fluor 594 Imaging Kit (C10330, Thermo Fisher Scientific). In brief, cells were grown on coverslips and subjected to treatment (if any) and a final concentration of 1 mM 5-EU was added into the culture medium for 1 hour. Cells were then fixed and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then counterstained with DAPI and mounted onto glass slides for visualization.

Live cell imaging

mCherry-tagged ARIP4 was expressed in U2OS 263 (DISC reporter) cells cultured in glass-bottom confocal dishes (SPL Life Sciences). During live cell imaging acquisition, cells were kept in a 37°C temperature-controlled chamber with 5% CO2 supplied. Live imaging was conducted on LSM980 (Carl Zeiss) equipped with an inverted Axio Observer 7 stand and a motorized scanning stage. To observe induction of transcription, cells were treated with Dox (2 μg/ml) and time-lapse images were acquired every 10 min for 4 hours on ZEN 3.0 Blue (Carl Zeiss) software with a Plan Aprochromat 40×/1.4 oil differential interference contrast objective and further processed by ImageJ software.

RNA sequencing

Before sample preparation, LNCaP cells were confirmed as mycoplasma-negative. LNCaP cells grown to 80% confluency were infected twice with viral supernatant containing lentiCRISPRV2 with ARIP4 targeting sgRNAs for 24 hours. Cells were selected in puromycin (2 μg/ml) containing medium for 48 hours and allowed to recover for 24 hours. Before androgen induction, cells were washed twice in 1x PBS and incubated in charcoal-stripped serum-supplemented medium for 48 hours. LNCaP cells were then treated with 1 nM R1881 for 5 hours, washed, and harvested in ice-cold 1x DPBS. RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were then sent for polyA enrichment library construction and high-throughput sequencing. Significance was assessed using the R package DESeq2 (76) using raw read counts generated with Salmon against the hg38 transcription annotation. Significantly changed genes were assessed with an adjusted P value of less than 0.05 and a 1.5-fold gene expression change to determine set of significantly changed genes. Transcripts per million (TPMs) for biological duplicate RNA-seq in each cell line were combined using the average replicates of each condition and then doing a log2(fold change) comparison with a pseudocount of 1 in each condition, i.e., log2[(TPMCOND2 + 1)/(TPMCOND1 + 1)]. AR regulated genes were defined by TPM with log2(fold change) >1.2 in R1881-treated over ethanol-treated LNCaP cells. Matched genes were generated by randomly selecting a gene list with similar expression pattern as AR regulated genes in nontreated LNCaP cells using the MatchIt package in R (77).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Before harvest, LNCaP cells were cultured in charcoal-stripped FBS-supplemented media for at least 48 hours and subjected to 5 hours of ethanol (vehicle) or 1 nM R1881. Briefly, cells were cross-linked in 1% formalin for 10 min and quenched with 1.25 M Tris-Cl (pH 8). After two washes in ice-cold 1X PBS, nuclei were extracted with ChIP lysis buffer [10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and protease inhibitor cocktail]. Chromatin is fragmented by MNase digestion [MNase digestion buffer contains 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 15 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, and 1 mM CaCl2]; the reaction is quenched with a final concentration of 20 mM EDTA, and the nuclei were fully broken by sonication in SDS lysis buffer [1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, and 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8)]. Sonicated samples were then quenched with of 2X Stop/ChIP buffer [100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), 20 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, and 0.2% sodium deoxycholate] and centrifuged at maximum speed at 4°C for 10 min to remove the debris, with 1% reserved as an input, and the remaining chromatin samples were incubated with Protein A/G magnetic beads (Millipore) and indicated antibodies overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. Protein-bound beads were then washed with ice-cold low salt buffer [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), and 150 mM NaCl], high salt buffer [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), and 500 mM NaCl), ice-cold LiCl buffer [0.25 M LiCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8)], and ice-cold TE buffer [10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8) and 1 mM EDTA]. DNA is then eluted and decross-linked with ChIP elution buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS] at 65°C overnight and then incubated with proteinase K for at least 2 hours before DNA is purified by column purification. ChIP enrichment is then measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using SYBR green or submitted for library construction and next-generation sequencing.

Detection of androgen-dependent breaks by biotin-dUTP break labeling assay

Biotin-dUTP break labeling assay was conducted as detailed previously (7), with some minor adjustments. Briefly, hormone-treated cells were first fixed directly on a 60-mm dish with Streck Cell Preservative (Streck) with 10 mM EDTA for 45 min with gentle rocking at room temperature. Cells were then washed with ice-cold 1X TBS. Cells were then incubated with ice-cold buffer A [10 mM Hepes (pH 6.5), 0.25% Triton X-100, and 10 mM EDTA] for 5 min and then washed with ice-cold buffer B [10 mM Hepes (pH 6.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA]. Nuclei were extracted with buffer C [100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, and 50 mM EDTA] for 10 min at 4°C then washed with ice-cold 1X PBS, and DNA breaks were labeled with biotin-11-dUTP (Jena Biosciences) with TdT (NEB) for 1 hour at 37°C. Labeled nuclei were washed with buffer D [100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4) and 150 mM NaCl] before being fixed with 1% formaldehyde and subsequent ChIP procedures with anti-biotin antibody.

R-loop profiling by S9.6 CUT&Tag

R-loop profiles were captured by the S9.6 CUT&Tag method as established previously (51) and using a CUT&Tag kit (Active Motif, 53165) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were harvested and washed twice in ice-cold wash buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM spermidine] supplemented with protease inhibitors. Concanavalin A beads were added into the cell suspension and rotated at room temperature for 10 min. Bead-bound cells were then separated from the supernatant on a magnetic rack, and cells were resuspended in ice-cold antibody buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.05% digitonin, 0.01% NP-40, and 2 mM EDTA] supplemented with protease inhibitors. S9.6 antibody (2 μg) (Kerafast, ENH001) was added into bead-bound cells and rotated at 4°C overnight, with negative control samples supplemented with 10 U ribonuclease (RNase) H (NEB, M0297L). After overnight incubation, the secondary antibody diluted in dig-wash buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.05% digitonin, and 0.01% NP-40] supplemented with protease inhibitors was added and rotated at room temperature for 1 hour. The bead-bound cells were then washed three times in dig-wash buffer. pA-Tn5 transposomes were then diluted in Dig-300 buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM spermidine, and 0.05% digitonin] supplemented with protease inhibitors and incubated with rotation with the bead-bound cells for 1 hour at room temperature. Excess transposomes were removed by washing three times with Dig-300 buffer. Last, samples were tagmented in 125 μl of Tagmentation buffer [10 mM TAPS-NaOH (pH 8.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 10% N,N′-dimethylformamide, and 0.85 mM ATP] at 37°C for 1 hour. To stop the tagmentation reaction, 4.2 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, 1.25 μl of 10% SDS, and 1.1 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) were added and samples were incubated at 55°C for 1 hour to solubilize DNA fragments before column purification. DNA samples were then eluted, and libraries were amplified using a combination of Illumina i7/i5 indexed primers. Library cleanup was performed with a preliminary 1.1x SPRI bead cleanup followed by size selection with 0.5x and 1x Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, A63880). Libraries were then subjected to fragment analysis and Illumina sequencing.

ChIP-seq and S9.6 CUT&Tag data analysis

Paired-end reads from ChIP-seq and S9.6 CUT&Tag samples were mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using Bowtie2. Duplicate reads were removed using sambamba markdup for all downstream analyses. Peaks were called against input reads using MACS2 (78) version 2.2.6 at q = 0.05, and ChIP-seq track densities were generated per million mapped reads using parameters –B –SPMR (parameters: -f BAMPE -g 2862010578 -s 150 --keep-dup all -B --SPMR --nomodel -q 0.05). Log2 enrichment ratios (ChIP/input) of each replicate were calculated using Deeptools software (79). Peaks that overlap with ENCODE blacklisted regions (ENCFF356LFX) were removed. Reproducible peaks from two replicates were calculated by BEDTools using parameters intersect -f 0.50 -r. Heatmaps and profile of peaks identified form ChIP-seq were plotted at TSS, peak centers, or AR binding sites by plotHeatmap from Deeptools. Read coverage across the genome was calculated by bamCoverage and normalized using RPKM with a bin size of 10 bp. Peaks were annotated by ChIPseeker (80). S9.6 CUT&Tag, ARIP4, and Pol II coverage on TSS were calculated by megadepth. First, RPKM was generated from merged replicates of each samples, followed by generating per-base coverage over regions, which are 500-bp flanking TSSs (81). RNA Pol II TR or PI was determined using a reported method with modification (50). Briefly, PI was calculated by subtracting normalized Pol II ChIP signal on TSS flanking region (−50 to +300 bp) against its signal in gene body (+1 to +3000 bp). Transcript isoforms from each gene with strongest PI were extracted and used from downstream analysis. Metaplots in Figs. 2F and 5B and scatterplot in fig. S8F were generated using publicly available data detailed in table S3.

DNA:RNA immunoprecipitation

R-loop detection at specific gene loci were conducted with DRIP coupled with qPCR. DRIP was conducted as previously described (82) with some modifications. Briefly, genomic DNA was harvested by SDS/proteinase K digestion followed by phenol chloroform and ethanol purification. Genomic DNA was then fragmented with a cocktail of restriction enzymes, treated with RNase A by addition of 2X RNase A digestion mix [20 μg/ml RNase A, 1 M NaCl, and 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4)] for 1 hour at 37°C, and subjected to ethanol purification. Fragmented gDNA was then resuspended and incubated with anti-S9.6 antibody and Protein A+G magnetic beads overnight at 4°C with rotation. Beads were washed, and immunoprecipitated gDNA was eluted. Eluates were then subjected to a final round of phenol chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Precipitated gDNA was then resuspended in ultrapure water and analyzed by qPCR. Primers against positive control (R-loop forming; RPL13A) and negative control (non–R-loop forming; EGR1) loci were taken from Sanz and Chédin (82).

Protein purification from insect cells

Full-length and point mutants of ARIP4 were purified from insect cells using the baculovirus system based on an established method by Ti et al. (83). Cells were harvested with a lysis buffer containing [20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM ATP]. 6xHis-TEV-tagged ARIP4 is then captured with nickel affinity chromatography. The 6xHis tag is then cleaved by TEV digestion and dialyzed and then further purified with nickel affinity chromatography and anion exchange chromatography with a Q column to obtain tag-free ARIP4. Last, ARIP4 is further purified by size exclusion chromatography in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-Cl, 2 mM MgCl2, 40 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% glycerol. Aliquots of 40-μl purified ARIP4 is snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in −80°C until ready for use. Expression and purification of DHX9 are as previously described (84).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay and helicase assay

Oligos were constructed based on a previous study (85). Sequences of the oligos and annealing mixtures are described in tables S4 and S5, respectively. Double-stranded oligos were annealed in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA and heated up to 95°C and slowly cooled down to room temperature for at least 2 hours. D-loops and R-loops were annealed with an annealing buffer containing 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 7 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, and freshly added 1 mM DTT. The mix is heated up to 95°C for 5 min, 37°C for 1 hour, and slowly cooled down to room temperature overnight. ARIP4 binding assays and helicase assays were done based on previously established conditions (27). For binding assays, indicated concentrations of ARIP4 is allowed to bind to 30 nM substrate in binding buffer containing 17 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.80, 12 mM Hepes (pH 7.7), 6 mM MgCl2, 15 mM NaCl, 55 mM KCl, 0.3 mM EDTA, 5.5% glycerol, 1.25 mM DTT, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 0.25 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Binding reactions are incubated at 37°C for 30 min before adding 10 times molar excess of sheared salmon sperm DNA as a competitor and terminated at 60 min from the start of the reaction. Samples are applied onto prerun 5% native PAGE gels for 1 hour at 100 V and 4°C, and gels are imaged using Cy3 channel in a BioRad Chemidoc imager. For helicase assays, indicated concentrations of ARIP4 are allowed to bind to 10 nM substrate in helicase buffer containing final concentrations of 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 3.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, BSA (0.1 mg/ml), 5 mM DTT, and 4% (v/v) glycerol. Helicase assays are incubated at 37°C and quenched with loading buffer containing 600 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 60% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 75 mM EDTA, 0.3% SDS, and 10 times molar excess of a competitor strand for the nonfluorescent oligonucleotide strand to prevent reannealing. Samples were applied for native PAGE as stated above.

Replicates and statistical analysis

Unless stated otherwise, all the data presented are expressed as means ± SEM from at least three independent replicates using GraphPad Prism 6. For immunofluorescence experiments, at least three independent replicates were done with at least 50 nuclei quantified per treatment group. Statistical significances were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test unless otherwise stated. Paired t tests were conducted when comparing the same set of specimen/samples/genes across treatments. Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted when data do not follow a normal distribution. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge CPOS (The University of Hong Kong) for technical help with all sequencing and imaging experimentations and thank R. Greenberg and P. Sung for generous sharing of reagents.

Funding: This work was primarily supported by grants from Research Grants Council Hong Kong to M.S.Y.H. (project nos. 1710062, 17100520, and T12-702/20/N) and the STU Scientific Research Initiation Grant to Z.L. (no. NTF23001). R.R.N. is supported by the Hong Kong PhD Fellowship. J.W.C.L. is supported by grants from the NIH (NIGMS: R35GM137798; NCI: R01CA244261) and American Cancer Society (RSG-20-131-01-DMC and TLC-21-164-01-TLC).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: R.R.N., M.S.Y.H., Z.L., J.W.C.L., and A.H.N.T. Data curation: M.S.Y.H., Z.L., and A.H.N.T. Formal analysis: R.R.N., Z.L., J.W.H.W., J.W.C.L., A.H.N.T., and Y.Z. Funding acquisition: M.S.Y.H. and J.W.C.L. Investigation: R.R.N., S.C.T., J.W.C.L., Q.F., A.J., A.H.N.T., and Y.Z. Methodology: R.R.N., M.S.Y.H., Z.L., J.W.H.W., S.C.T., and A.H.N.T. Project administration: M.S.Y.H. Resources: M.S.Y.H., Z.L., S.C.T., J.W.C.L., Q.F., A.H.N.T., and Y.Z. Software: Z.L. Supervision: M.S.Y.H. Validation: R.R.N., M.S.Y.H., Z.L., J.W.C.L., Q.F., and A.H.N.T. Visualization: R.R.N., M.S.Y.H., Z.L., J.W.H.W., J.W.C.L., and A.H.N.T. Writing—original draft: R.R.N., MS.Y.H., Z.L., S.C.T., A.J., and A.H.N.T. Writing—review and editing: R.R.N., M.S.Y.H., Z.L., J.W.C.L., Q.F., and A.H.N.T.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The datasets generated during this study are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (PRJNA1033034). All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S11

Tables S1 to S5

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Core L. J., Waterfall J. J., Lis J. T., Nascent RNA sequencing reveals widespread pausing and divergent initiation at human promoters. Science 322, 1845–1848 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Core L., Adelman K., Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: A nexus of gene regulation. Genes Dev. 33, 960–982 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine M., Paused RNA polymerase II as a developmental checkpoint. Cell 145, 502–511 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huggins C., Hodges C. V., Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. CA Cancer J. Clin. 22, 232–240 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomlins S. A., Rhodes D. R., Perner S., Dhanasekaran S. M., Mehra R., Sun X. W., Varambally S., Cao X., Tchinda J., Kuefer R., Lee C., Montie J. E., Shah R. B., Pienta K. J., Rubin M. A., Chinnaiyan A. M., Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science 310, 644–648 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haffner M. C., Aryee M. J., Toubaji A., Esopi D. M., Albadine R., Gurel B., Isaacs W. B., Bova G. S., Liu W., Xu J., Meeker A. K., Netto G., De Marzo A. M., Nelson W. G., Yegnasubramanian S., Androgen-induced TOP2B-mediated double-strand breaks and prostate cancer gene rearrangements. Nat. Genet. 42, 668–675 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ju B. G., Lunyak V. V., Perissi V., Garcia-Bassets I., Rose D. W., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G., A topoisomerase IIβ-mediated dsDNA break required for regulated transcription. Science 312, 1798–1802 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson L. M., Lees-Miller S. P., Estrogen receptor α-mediated transcription induces cell cycle-dependent DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis 32, 279–285 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trotter K. W., King H. A., Archer T. K., Glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activation via the BRG1-dependent recruitment of TOP2β and Ku70/86. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35, 2799–2817 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madabhushi R., Gao F., Andreas R. P., Pan L., Yamakawa S., Seo J., Rueda R., Phan T. X., Yamakawa H., Pao P.-C., Stott R. T., Gjoneska E., Nott A., Cho S., Kellis M., Tsai L.-H., Activity-induced DNA breaks govern the expression of neuronal early-response genes. Cell 161, 1592–1605 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delint-Ramirez I., Konada L., Heady L., Rueda R., Jacome A. S. V., Marlin E., Marchioni C., Segev A., Kritskiy O., Yamakawa S., Reiter A. H., Tsai L. H., Madabhushi R., Calcineurin dephosphorylates topoisomerase IIβ and regulates the formation of neuronal-activity-induced DNA breaks. Mol. Cell 82, 3794–3809.e8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunch H., Lawney B. P., Lin Y. F., Asaithamby A., Murshid A., Wang Y. E., Chen B. P., Calderwood S. K., Transcriptional elongation requires DNA break-induced signalling. Nat. Commun. 6, 10191 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellino G. I., Palluzzi F., Chiariello A. M., Piccioni R., Bianco S., Furia L., De Conti G., Bouwman B. A. M., Melloni G., Guido D., Giacò L., Luzi L., Cittaro D., Faretta M., Nicodemi M., Crosetto N., Pelicci P. G., Release of paused RNA polymerase II at specific loci favors DNA double-strand-break formation and promotes cancer translocations. Nat. Genet. 51, 1011–1023 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh S., Szlachta K., Manukyan A., Raimer H. M., Dinda M., Bekiranov S., Wang Y.-H., Pausing sites of RNA polymerase II on actively transcribed genes are enriched in DNA double-stranded breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 3990–4000 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niehrs C., Luke B., Regulatory R-loops as facilitators of gene expression and genome stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 167–178 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L., Chen J.-Y., Zhang X., Gu Y., Xiao R., Shao C., Tang P., Qian H., Luo D., Li H., Zhou Y., Zhang D.-E., Fu X.-D., R-ChIP using inactive RNase H reveals dynamic coupling of R-loops with transcriptional pausing at gene promoters. Mol. Cell 68, 745–757.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo-Guzman D., Chédin F., Defining R-loop classes and their contributions to genome instability. DNA Repair (Amst.) 106, 103182 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L., Chen J.-Y., Huang Y.-J., Gu Y., Qiu J., Qian H., Shao C., Zhang X., Hu J., Li H., He S., Zhou Y., Abdel-Wahab O., Zhang D.-E., Fu X.-D., The augmented R-loop is a unifying mechanism for myelodysplastic syndromes induced by high-risk splicing factor mutations. Mol. Cell 69, 412–425.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards D. S., Maganti R., Tanksley J. P., Luo J., Park J. J. H., Balkanska-Sinclair E., Ling J., Floyd S. R., BRD4 prevents R-loop formation and transcription-replication conflicts by ensuring efficient transcription elongation. Cell Rep. 32, 108166 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sridhara S. C., Carvalho S., Grosso A. R., Gallego-Paez L. M., Carmo-Fonseca M., De Almeida S. F., Transcription dynamics prevent RNA-mediated genomic instability through SRPK2-dependent DDX23 phosphorylation. Cell Rep. 18, 334–343 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shivji M. K. K., Renaudin X., Williams Ç. H., Venkitaraman A. R., BRCA2 regulates transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II to prevent R-loop accumulation. Cell Rep. 22, 1031–1039 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X., Chiang H.-C., Wang Y., Zhang C., Smith S., Zhao X., Nair S. J., Michalek J., Jatoi I., Lautner M., Oliver B., Wang H., Petit A., Soler T., Brunet J., Mateo F., Angel Pujana M., Poggi E., Chaldekas K., Isaacs C., Peshkin B. N., Ochoa O., Chedin F., Theoharis C., Sun L.-Z., Curiel T. J., Elledge R., Jin V. X., Hu Y., Li R., Attenuation of RNA polymerase II pausing mitigates BRCA1-associated R-loop accumulation and tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 8, 15908 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rouleau N., Domans'kyi A., Reeben M., Moilanen A. M., Havas K., Kang Z., Owen-Hughes T., Palvimo J. J., Janne O. A., Novel ATPase of SNF2-like protein family interacts with androgen receptor and modulates androgen-dependent transcription. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2106–2119 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sitz J. H., Tigges M., Baumgärtel K., Khaspekov L. G., Lutz B., Dyrk1A potentiates steroid hormone-induced transcription via the chromatin remodeling factor Arip4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5821–5834 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]