Abstract

In the present work, two hybrid series of pyrazole-clubbed pyrimidine and pyrazole-clubbed thiazole compounds 3–21 from 4-acetyl-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-ole 1 were synthesized as novel antimicrobial agents. Their chemical structures were thoroughly elucidated in terms of spectral analyses such as IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and mass spectra. The compounds were in vitro evaluated for their antimicrobial efficiency against various standard pathogen strains, gram -ive bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia), gram + ive bacteria (MRSA, Bacillus subtilis), and Unicellular fungi (Candida albicans) microorganisms. The ZOI results exhibited that most of the tested molecules exhibited inhibition potency from moderate to high. Where compounds 7, 8, 12, 13 and 19 represented the highest inhibition potency against most of the tested pathogenic microbes comparing with the standard drugs. In addition, the MIC results showed that the most potent molecules 7, 8, 12, 13 and 19 showed inhibition effect against most of the tested microbes at low concentration. Moreover, the docking approach of the newly synthesized compounds against DNA gyrase enzyme was performed to go deeper into their molecular mechanism of antimicrobial efficacy. Further, computational investigations to calculate the pharmacokinetics parameters of the compounds were performed. Among them 7, 8, 12, 13 and 19 are the most potent compounds revealed the highest inhibition efficacy against most of the tested pathogenic microbes comparing with the standard drugs.

Keywords: 4-Acetyl-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-5(4H)-ole; Pyrazole; Antibiotic resistance; Antimicrobial activities; DNA gyrase; Molecular docking

1. Introduction

Fleming was the first who admonish about the risk of the global antibiotic resistance [[1], [2], [3]]. The antibiotic resistance was first identified in Shigella, Salmonella and E. Coli [[4], [5], [6]]. Owing to the antibiotic misuse, where these antibiotics are available and used without prescriptions, the bacteria acquired antibiotic resistance against most of the commercially available antibiotics [4,5,7,8]. Consequently, resistance of the antibiotics is considered as a global public health concern by the world health organization (WHO) [9]. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections pose a serious clinical and financial burden to people all over the world. MRSA is turning into a fatal sickness for humans because it is easily transmitted, causes severe skin infections, and resists most recognized antibiotics, including vancomycin. Consequently, identify potential antimicrobial drug candidates to overcome MRSA isolates is urgently required [10].

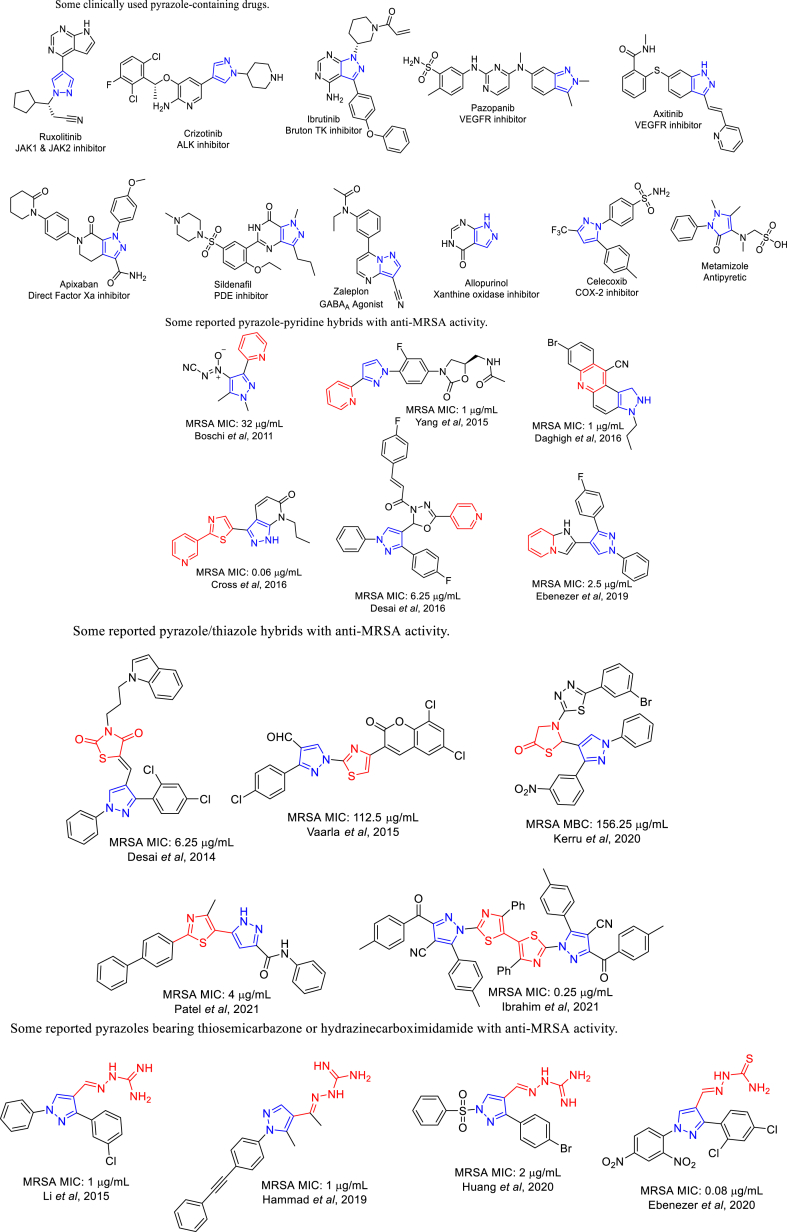

Heterocyclic compounds incorporating pyrazole moiety constitute an essential class of biologically active compounds that are gaining an attention in medicinal bioorganic chemistry [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. Many clinically used drugs contain pyrazole moiety, as shown in Fig. 1. The most important class of pyrazole-containing drugs is tyrosine kinase inhibitors like ruxolitinib (Jakafi®) which is used in myelofibrosis, and polycythemia vera, crizotinib (Xalkori®) which is indicated in treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, ibrutinib (Imbruvica®) which is indicated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and finally axitinib (Inlyta®) and pazopanib (Votrient®) which are indicated in advanced renal cell carcinoma [15]. Vicinal diaryl azoles were utilized as scaffolds for selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition [16]. One of these azoles is a pyrazole which was found in celecoxib (Celebrex®) which is still clinically used till now. Metamizole (Novalgin®) is a sulfonic acid-containing pyrazole derivative which is still used as antipyretic till now despite its several adverse effects. Sildenafil (Viagra®) is a pyrazolopyrimidine phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor which is used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Other pyrazole-containing drugs like anticoagulant, apixaban (Eliquis®), allopurinol (Zyloprim®) and a non-benzodiazepine zaleplon (Sonata®) are used as sedatives, hypnotics and anxiolytics [10].

Fig. 1.

Some clinically used pyrazole-containing drugs, reported pyrazole-pyridine hybrids with anti-MRSA activity, reported pyrazole/thiazole hybrids with anti-MRSA activity and reported pyrazoles bearing thiosemicarbazone or hydrazinecarboximidamide with anti-MRSA activity.

Pyridine was incorporated in plenty of reported antimicrobial derivatives [17]. Several pyrazole-pyridine hybrids were reported to have markable antimicrobial activity especially against MRSA [18], as declared in Fig. 1. Thiazolidine was fused with a β-lactam ring to form a penam ring which is the main pharmacophoric element of penicillin antibiotics as well as β-lactamase inhibitors like sulbactam and tazobactam [19]. Moreover, aminothiazole moiety was incorporated in 3rd and 4th generation cephalosporines like cefotaxime, ceftriaxone and cefepime to improve their activity against gram -ive bacteria. The 5th generation cephalosporine like ceftaroline with thiazole ring is characterized by its antibacterial activity against MRSA [19]. Additionally, molecular hybridization of pyrazole ring with thiazole afforded several hybrids with remarkable antibacterial and antifungal activity [20], as represented in Fig. 1. Thiosemicarbazone and its isostere hydrazinecarboximidamide were reported to be involved in several antimicrobial derivatives especially with pyrazole ring that have a remarkable activity against MRSA [21], as represented in Fig. 1.

DNA gyrase is considered as a crucial target for design and development of effective antibacterial inhibitors due to its ability to induce negative supercoiling of DNA or relieve positive supercoiling [20]. Gyrase is present in prokaryotes and specific eukaryotes, albeit with variations in structure and sequence, resulting in different affinities for diverse derivatives [[22], [23], [24]]. Furthermore, it is an extensively researched objective that is essential for bacterial DNA replication [25]. Consequently, the justification for utilizing DNA gyrase is mainly substantiated by reported pyrazole-containing compounds, which have strong affinity for this protein.

The molecular docking approach is a technique used to discover structures for the active sites of proteins, in addition to identify the potential mechanism of action [[26], [27], [28]].

Viewing the importance of heterocyclic compounds incorporating pyrazole ring in medicinal chemistry field and to highlight the scope of compounds containing pyrazole, pyridine and/or thiazole moiety, herein, synthesis of two hybrid series of pyrazole-clubbed pyrimidine and pyrazole-clubbed thiazole derivatives 3–21 from compound 1 is described. The antimicrobial potency of the newly prepared compounds was estimated against the various standard pathogen strains, gram -ive bacteria (P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia), gram + ive bacteria (MRSA, B. subtilis), and fungi (C. albicans) microorganisms. Further, in silico docking approaches [25,[29], [30], [31]] of the molecules were performed to investigate their binding interactions with DNA gyrase enzyme.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

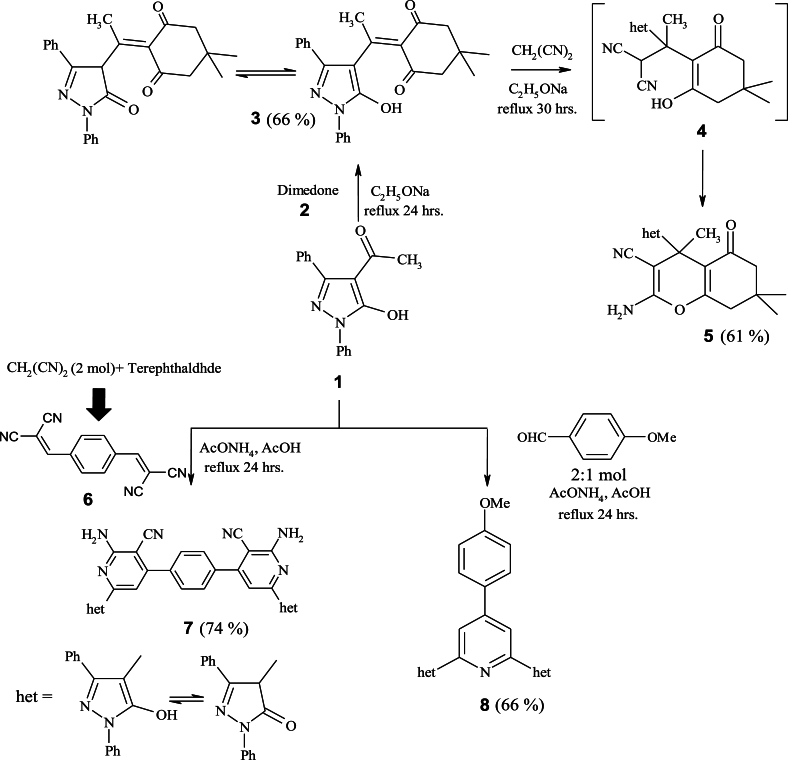

The starting compound 1 was prepared using a well-known process from the literature [32]. It was used as a precursor to prepare a series of novel heterocyclic compounds via one pot multi component reaction (MCR). Thus, condensation reaction of 1 with dimedone's active methylene 2 yielded the arylidene derivative 3, which creates a cyclic intermediate 4 by adding malononitrile to the activated double bond, followed by cyclization to furnish 5,6,7, 8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile 5 [33] (Scheme 1). Through elemental and spectral analyses, the structure of product 5 was verified. IR spectrum exhibited absorption bands at ν 3449, 2198, and 1710 cm−1 for –NH2, –CN and –CO, respectively. Moreover, 1H NMR analysis exhibited the following signals at δ 0.94 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.51 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.62 (s, 2H, CH2), 6.02 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.29–7.83 (m, 10H, Ar–H), 14.49 (s, 1H, OH). However, a parent peak at m/z (%) 466 (M+) is in agreement with the proposed structure.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 3, 5, 7 and 8.

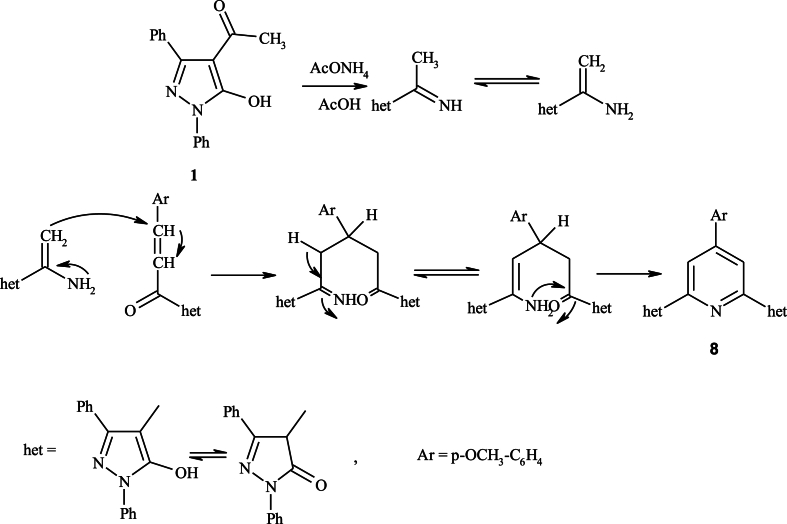

Considerable attention has been devoted to pyrazole-pyridine hybrids as antimicrobial agents [34,35]. By using MCR, our research was expanded to create a novel bipyridine rings clubbed pyrazole moiety 7 via refluxing of 1 with terephthaldehyde, malononitrile, and ammonium acetate in glacial acetic acid. These hypotheses were confirmed by allowing derivative 1 to interact with arylidene malononitrile, which was made by condensing (terephthaldehyde with malononitrile). Spectral and elemental analyses were used to clarify the product's structure [36]. IR spectrum revealed absorption bands at ν 3461–3328, 3058, 2195 cm−1 assigned to (-OH/–NH2), CH-aromatic, and –CN groups, respectively. However, 1H NMR analysis showed one signal at ™ 6.10 ppm for –NH2, along with expected signals for the aryl and hydroxyl protons. Additionally, the molecular ion peak in the mass spectrum is compatible with the suggested structure. On the other hand, reaction of 2 mol of 1 with substituted aromatic aldehyde and ammonium acetate at 160 °C yielded 4,4'-(4-(4-methoxyphenyl)pyridine-2,6-diyl)bis(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol 8 [37]. IR spectrum revealed the existence of OH-specific bands at 3449, CH-aromatic at 3060, CH-aliphatic at ν 2931 cm−1. Its 1H NMR analysis displayed a singlet peak at δ 3.71 ppm assigned to –OCH3 protons, a singlet peak at δ 5.23 ppm attributed to two protons of the pyridine ring, multiplet peaks at ™ 6.87–7.84 ppm corresponding to Ar–H. Further, the –OH group appeared at δ 14.32 ppm. The parent peak at the m/z 653 (M+) indicated by the appropriate molecular formula might be seen in the mass spectrum. The proposed mechanism for formation of compound 8 is presented in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

The suggested mechanism for preparation of product 8.

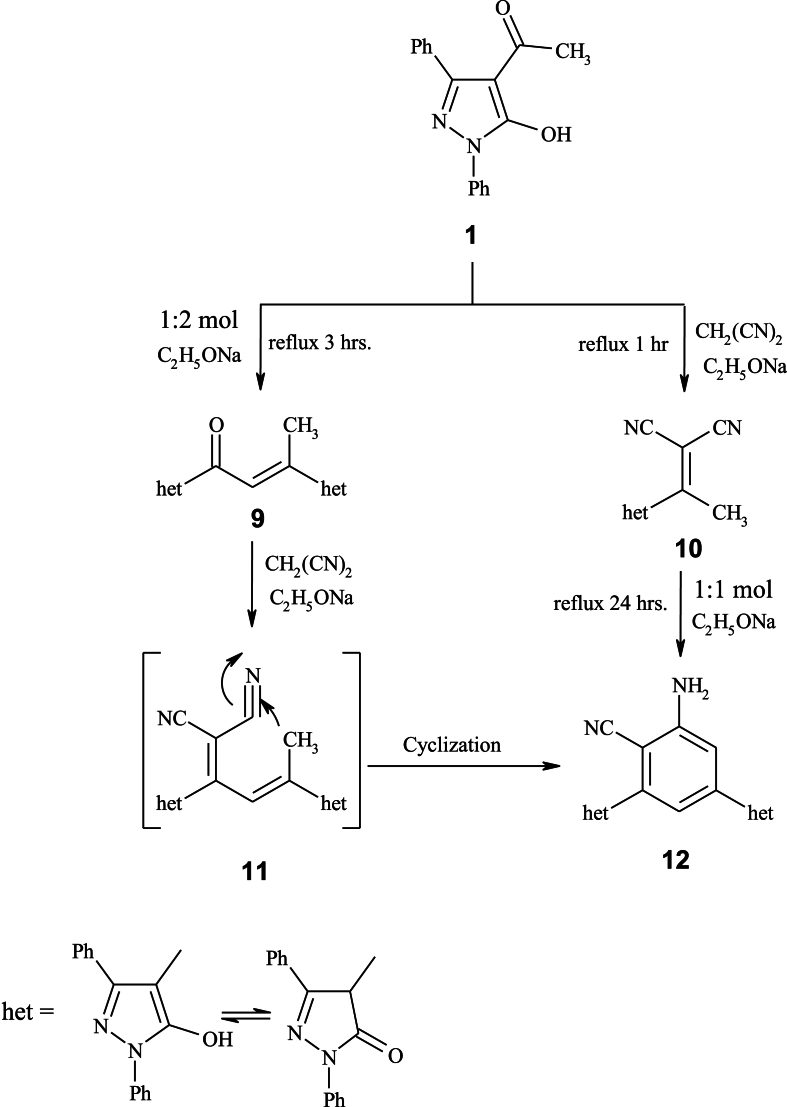

Based on spectral data, product 9 that resulted from the condensation of 2 mol of 4-acetylpyrazole-5-ole 1, was confirmed. Moreover, reaction of 9 with malononitrile furnished 2-amino-4,6-bis(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)benzonitrile 12. The formation of 12 could be explained by condensation of 9 with malononitrile to yield an intermediate 11, which undergoes intermolecular cyclization through the nucleophilic addition of methyl group to one of the carbonitrile function followed by aromatization (Scheme 3). On the other hand, using analytical and spectral data, condensation of 1 with malononitrile in sodium ethoxide (EtONa) produced 2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethylidene)malononitrile 10. Then, by cyclizing compound 10 with 1, the benzonitrile derivative 12 was formed, confirming the chemical composition of 12 [38].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compound 12.

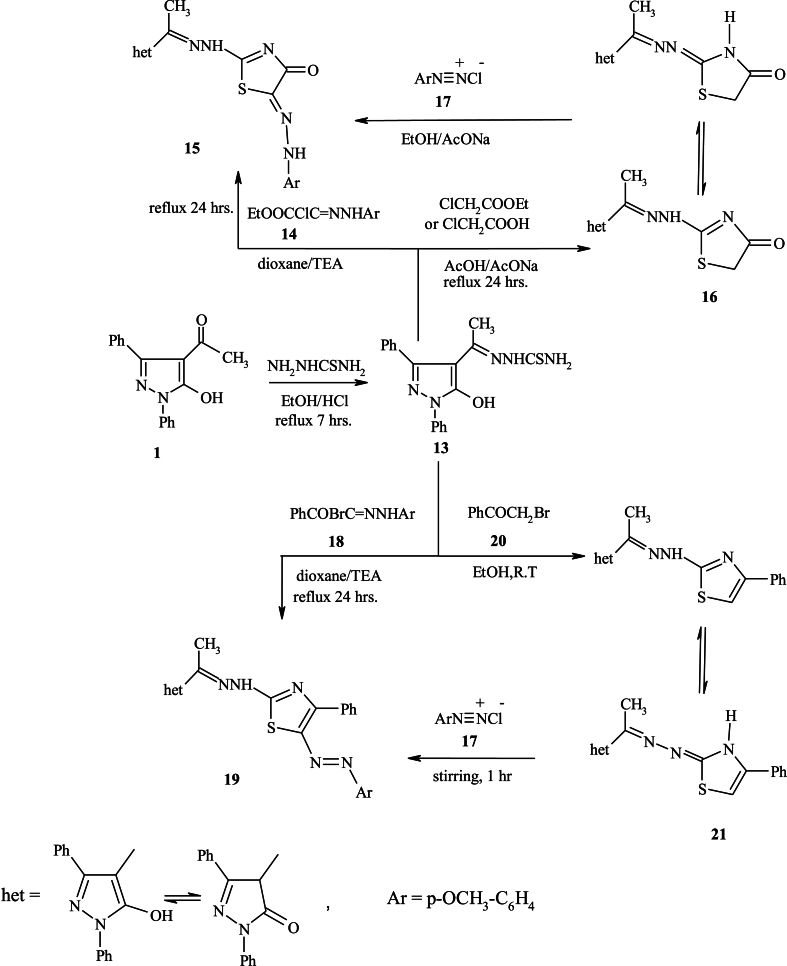

Synthesis of compounds incorporating pyrazole moiety attached to thiazole and/or thiazolidine cores 15, 16, 19 and 21 is of particular interest because of their antimicrobial activities [20]. In this study, we also described a very effective synthetic method for certain thiazole and/or thiazolidine scaffolds attached to pyrazole moiety. The crucial step, 2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-yl)ethylidene) hydrazinecarbothioamide 13, was produced by reacting 1 with thiosemicarbazide in an acidic medium. The latter compound 13 was reacted with ethyl 2-chloro-2-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)hydrazono)acetate 14 to yield thiazole derivative 15. The IR analysis presented absorption bands at ν 3300, 3128, 3028, 2881 and 1685 cm−1 characteristic of (-OH/–NH–), CH-aromatic, CH-aliphatic and –CO groups, respectively. However, 1H NMR spectrum declared characteristic singlet signals in the region ™ 6.02, 6.50 ppm referred to NH protons. The parent peak at 527 (M++2) confirmed the hypothesized structure.

The thiazolidinone 16 was produced via reaction of 13 with ethyl-2-chloroacetate and/or chloroacetic. 1H NMR spectrum represented the existence of a singlet peak at ™ 1.25 ppm referred to –CH3 group, multiple peaks at ™ 7.28–7.86 ppm for Ar–H, along with a singlet peak at ™ 5.02 ppm referred to –CH2 group, a peak of NH proton at ™ 6.06 ppm, and hump one at ™ 11.80 ppm corresponding to –OH group. However, the MS of 16 showed the parent peak at 393 (M++2), assignable to C20H17N5O2S.

Coupling of 16 with aryldiazonium chloride 17 yielded 15 in all respects (m.p., mixed m.p., and spectral data). Similar to this, 4-(-1-(2-(5-(4-methoxyphenyl)diazenyl)-4-phenylthiazol-2-yl) hydrazono)ethyl)-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol 19 was synthesized by reaction of 13 and hydrazonoyl halide 18. Finally, the thiazole derivative 21 was produced in good yield by combining thiosemicarbazone derivative 13 with bromoacetophenone. Upon coupling thiazole derivative 21 with aryldiazonium chloride 17, the compound 19 was obtained [24,39], as declared in Scheme 4. The spectral analyses in (Supplementary Material File) confirmed the chemical structures of the newly prepared molecules.

Scheme 4.

Synthetic methods for compounds 13, 15, 16, 19 and 21.

2.2. In vitro biological activity

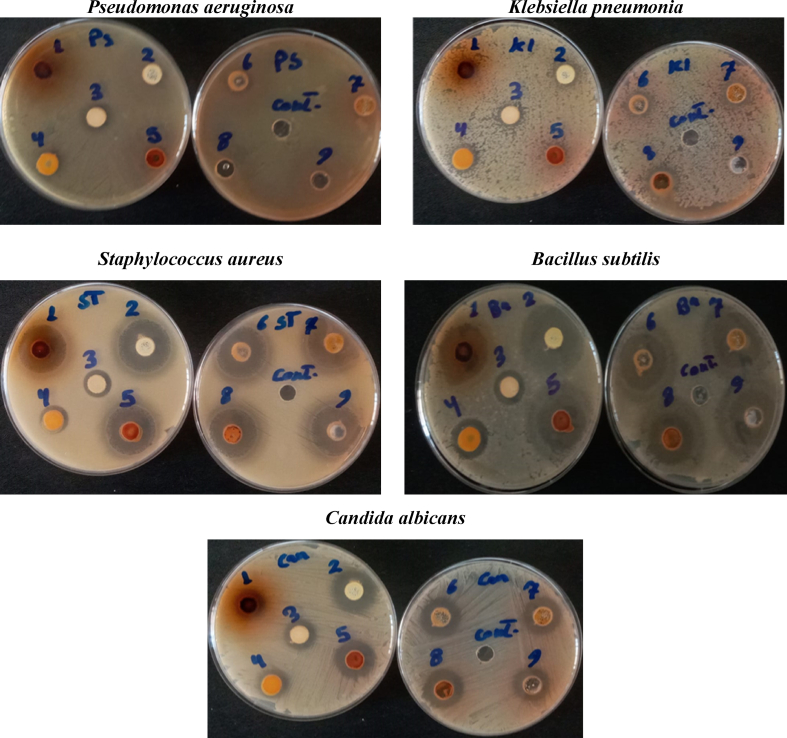

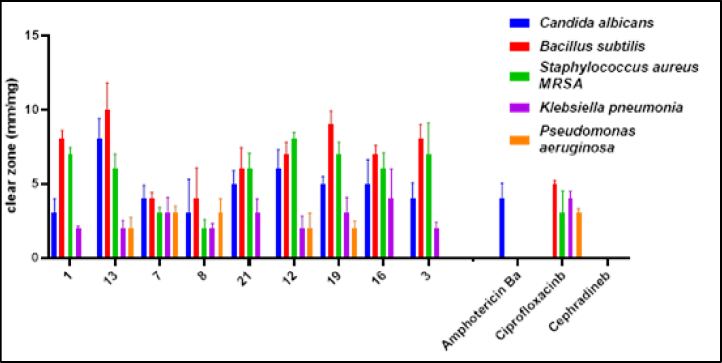

The antimicrobial potency of the tested molecules was estimated against the various standard pathogen strains, gram -ive bacteria (P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia), gram + ive bacteria (MRSA, B. subtilis), and fungi (C. albicans) microorganisms. The inhibition zone diameter was determined using agar-well diffusion and the results were stated below in (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The results showed that most of the tested molecules exhibited moderate to high inhibition efficacy. Where 7, 8, 12, 13 and 19 are the most potent compounds revealed the highest inhibition efficacy comparing to the standard drugs.

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial activities of the prepared molecules using agar-well diffusion.

Fig. 3.

Two-way ANOVA showed a high significance between different samples and type of microbe used in the antimicrobial test. (p-value <0.0001).

The MIC of the most potent molecules 7, 8, 12, 13 and 19 was determined and mentioned in Table 1. The obtained results represented that the most potent molecules exhibited inhibition effect against most of the tested microbes at low concentration. In which compounds 12 and 13 showed strong effect against C. albicans at concentration 5 μg/mL. Compound 8 showed strong efficacy against C. albicans at concentration 10 μg/mL. Compound 8, 12, 13 and 19 exhibited a strong antimicrobial potency against B. subtilis at low concentration 5 μg/mL. Otherwise, compound 12 showed strong efficacy against MRSA at concentration 10 μg/mL.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the potent prepared pyrazole derivatives.

| Compound | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC, μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | B. subtilis | S. aureus MRSA | K. pneumonia | P. aeruginosa | |

| 13 | 0.142 | 0.142 | 0.057 | 0.228 | 0.114 |

| 7 | 0.026 | 0.128 | 0.102 | 0.205 | 0.102 |

| 8 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.245 | 0.490 | 0.061 |

| 12 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.068 | 0.273 |

| 19 | 0.034 | 0.008 | 0.068 | 0.034 | 0.136 |

| Amphotericin Ba | 40 | – | |||

| Ciprofloxacinb | – | 20 | 80 | 40 | 40 |

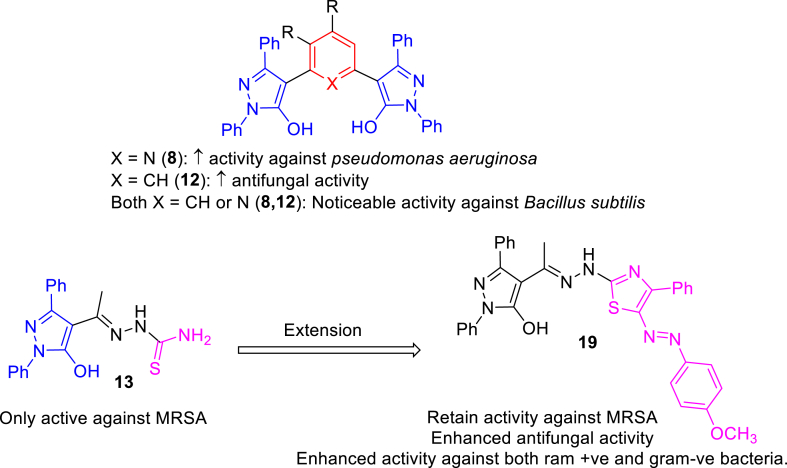

The structure activity relationship (SAR) is represented in Fig. 4. The dipyrazolylbenzene derivative 12 showed the highest antifungal activity (MIC = 8 μM). Compounds that showed the highest antibacterial activity against B. subtilis (MIC = 7–8 μM) were 2,6-dipyrazolylpyridine derivative 8, dipyrazolylbenzene derivative 12, and hydrazinylthiazole derivative 19. Additionally, hydrazinylthiazole derivative 19 was the most potent against K. pneumonia. The dipyrazolylbenzene derivative 12 exhibited the highest antibacterial activity against MRSA. Finally, 2,6-dipyrazolylpyridine derivative 8 was the most potent against P. aeruginosa.

Fig. 4.

The structure activity relationship (SAR) of the molecules.

2.3. In silico approaches

2.3.1. Molecular docking techniques

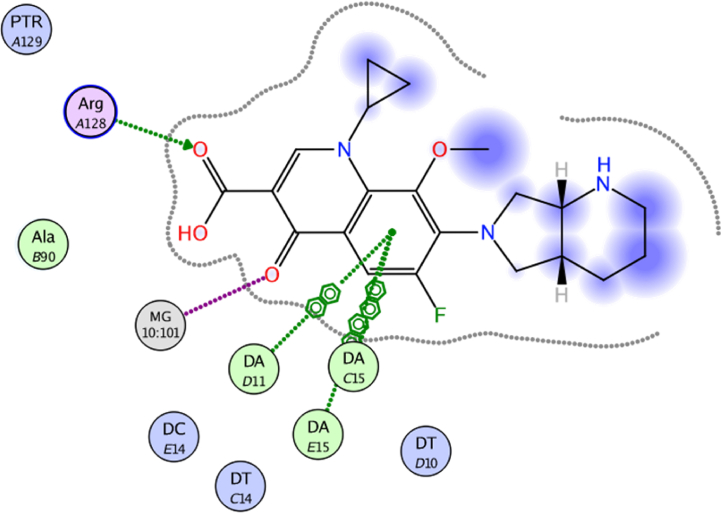

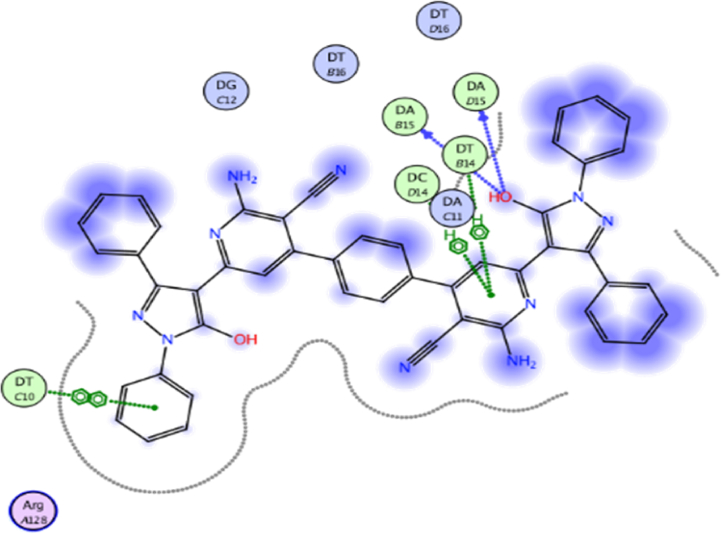

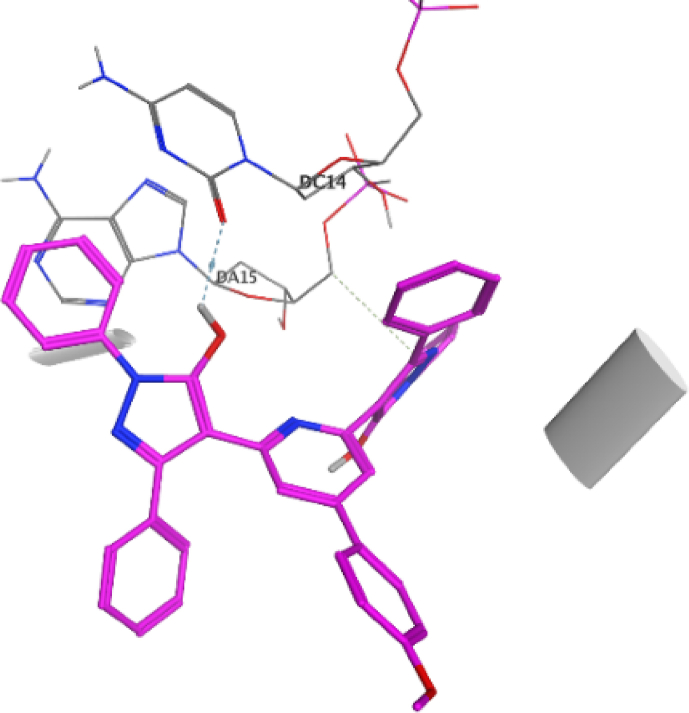

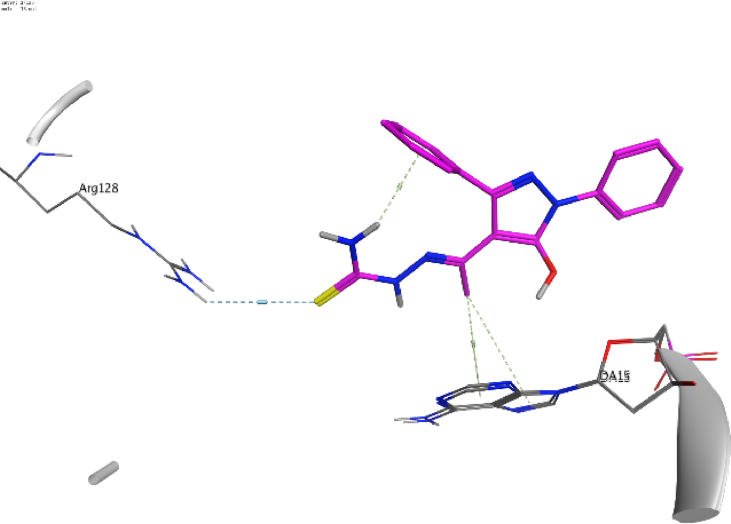

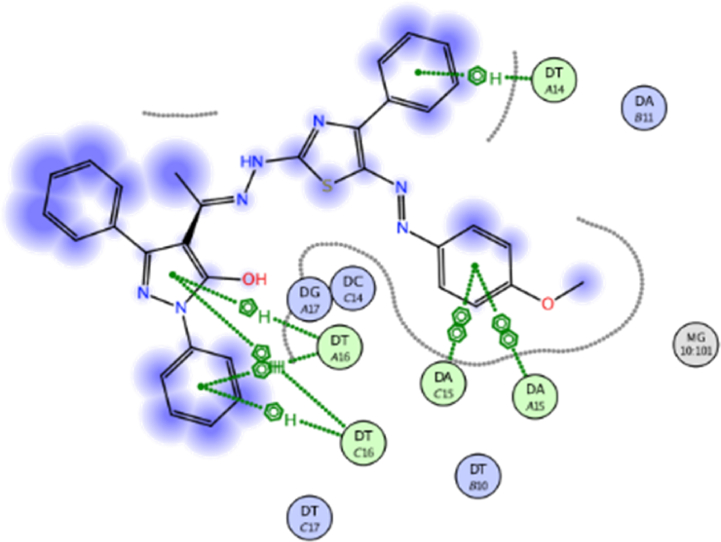

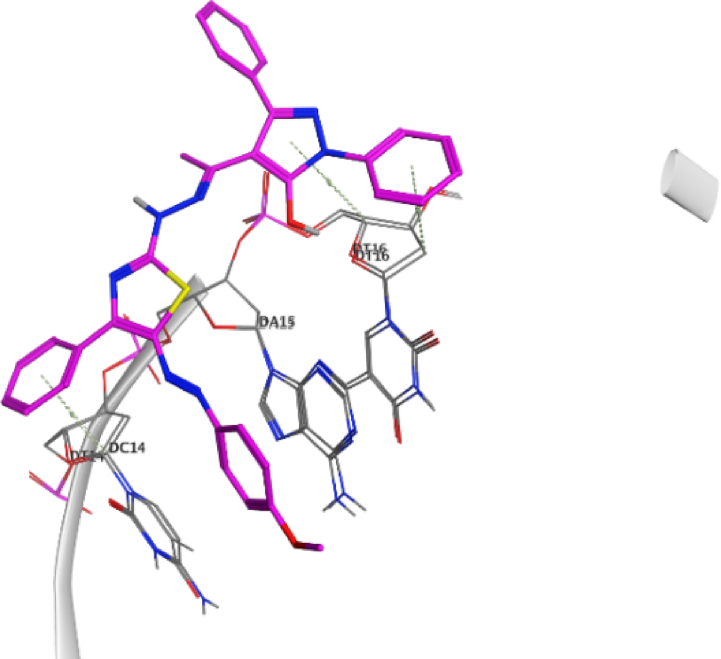

The docking approach is utilized discover structures for the active sites of proteins, in addition to identify the potential mechanism of action [40,41]. In the present work, to go deeper into the suitable binding pose and molecular mechanism of antimicrobial activity of compounds, molecular docking studies [42] were conducted using MOE software. Molecular docking studies revealed good interactions of compounds with DNA gyrase enzyme [43], as shown in Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15. Compared to moxifloxacin (score = −9.54 kcal/mol), Compound 7 (score = −8.29 kcal/mol) formed dual hydrogen bonds (HBs) (2.83 and 3.05 Å) with DA15 via hydroxyl group of pyrazole ring. The pyridine ring of compound 7 formed π-H interactions with DT14 as well as DC14 (4.16 and 4.13 Å, respectively). Additionally, phenyl ring at N1 of distal pyrazole of compound 7 formed π- π (3.89 Å) interaction with DT10 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 5.

2D interaction of moxifloxacin against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 6.

2D interaction of compound 7 against DNA gyrase.

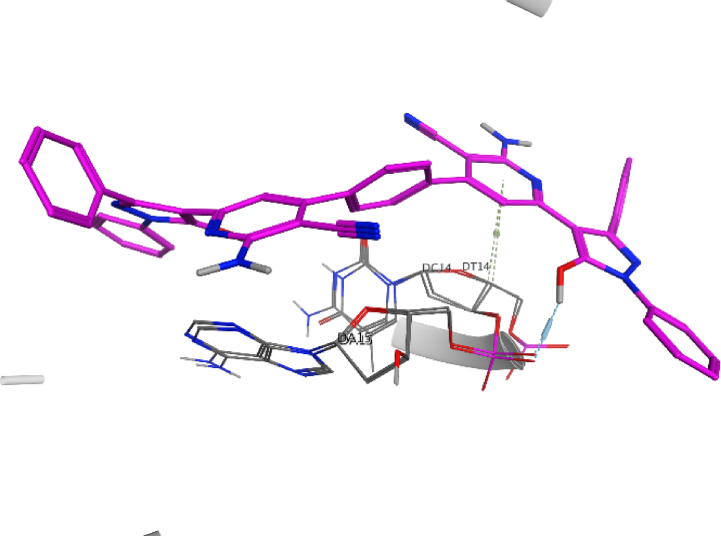

Fig. 7.

3D interaction of compound 7 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 8.

2D interaction of compound 8 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 9.

3D interaction of compound 8 against DNA gyrase.

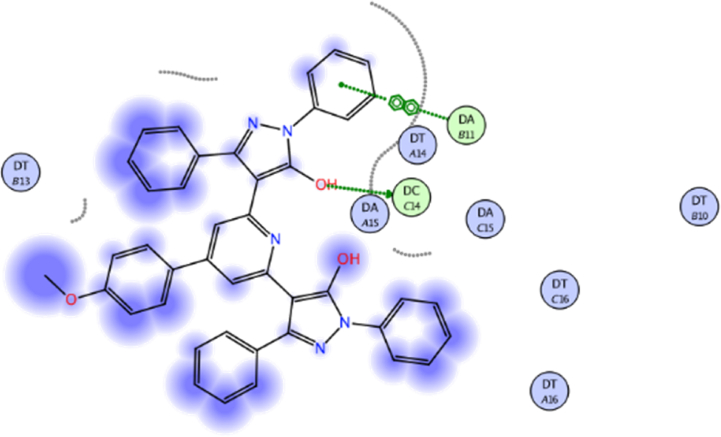

Fig. 10.

2D interaction of compound 12 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 11.

3D interaction of compound 12 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 12.

2D interaction of compound 13 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 13.

3D interaction of compound 13 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 14.

2D interaction of compound 19 against DNA gyrase.

Fig. 15.

3D interaction of compound 19 against DNA gyrase.

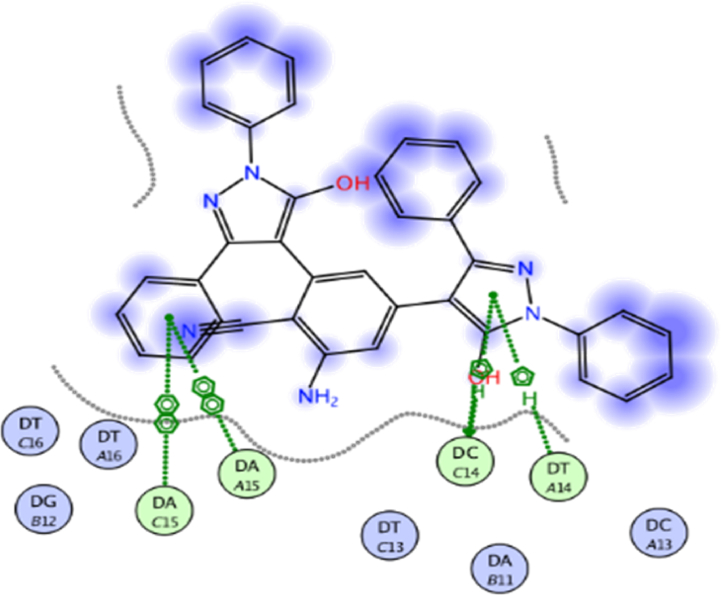

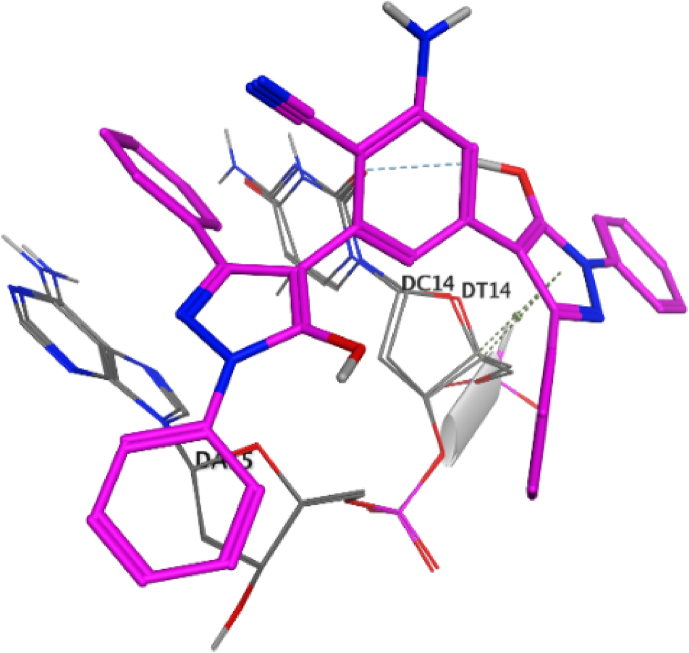

Hydroxyl group of pyrazole ring of compound 8 (score = −10.07 kcal/mol) acted as hydrogen bond donor (HBD) with DC14 (3.07 Å) (Fig. 9). In addition, N1-phenyl of pyrazole of compound 8 formed π- π interaction (3.59 Å) with DA11. Compound 12 (score = −8.06 kcal/mol) formed HB (3.42 Å) with DC14 (Fig. 10). The good affinity of compound 8 toward DNA gyrase enzyme (score = −10.07 kcal/mol) is reflected in its good binding strength against B. subtilis (MIC = 0.007 μg/mL) and P. aeruginosa (MIC = 0.061 μg/mL).

Moreover, pyrazole ring of compound 12 formed two π-H interactions (3.81 and 3.76 Å) with DT14 and DC14, respectively. In addition, the phenyl ring at N1 of distal pyrazole of compound 12 formed two π- π interactions (3.76 and 3.71 Å) with DA15.

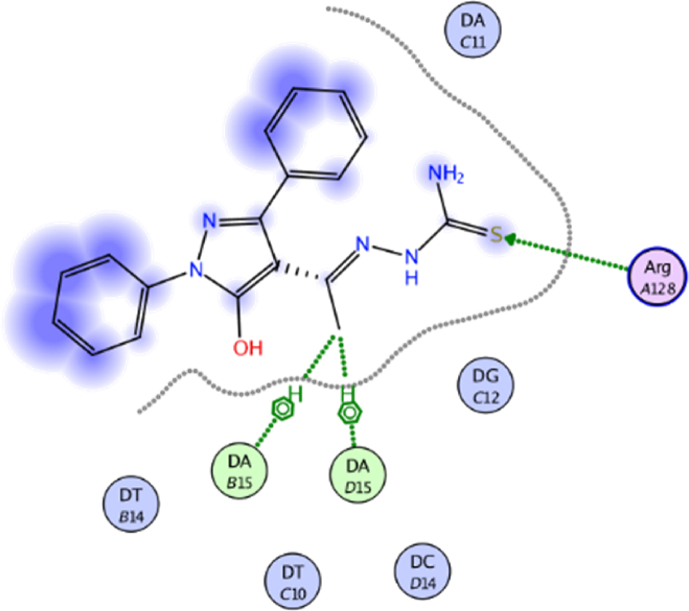

Compound 13 (score = −7.46 kcal/mol) acted as hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) (4.49 Å) via hydrazine carbothioamide moiety (Fig. 11) as well as forming H-π interactions (3.99 and 4.06 Å) with DA15.

Finally, N-phenylpyrazole moiety of compound 19 (score = −12.01 kcal/mol) formed four π-H interactions (4.33, 3.82, 4.37 and 3.85 Å) with DT16 (Fig. 12). Phenyl ring at thiazole C4 of compound 19 formed π-H interactions (3.89 Å) with DT14. Additionally, phenyldiazenyl mioety at thaizole C5 formed two π- π interactions (3.84 and 3.83 Å) with DA15. Out of all synthesized derivatives, compound 19 showed the highest binding score which aligns with its good binding strength against MRSA (MIC = 0.068 μg/mL), B. subtilis (MIC = 0.008 μg/mL) and K. pneumonia (MIC = 0.034 μg/mL).

2.3.2. Pharmacokinetics prediction

Aside from efficacy and safety profiles, several drug candidates have failed to reach clinic due to their poor physicochemical characters and pharmacokinetics [26,27]. SwissADME website was utilized to estimate several physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of molecules (Supplementary Material). None of the compounds was predicted to be P-gp substrate. Compounds were predicted to have a little inhibitory activity on different CYP450 isozymes like 1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6 and 3A4. Consequently, compounds were predicted to have few drug-drug interactions. Compounds 1, 3, 5, 10, 13, 15, 16 and 19 showed high GI absorption while other compounds 7, 8, 9, 11, 12 and 21 showed low GI absorption.

The BOILED-Egg is a sturdy model that precisely predicts both GI absorption and blood brain barrier (BBB) permeability by calculating both the WLOGP (lipophilicity) and TPSA (polarity) (Supplementary Material). Compounds 1, 3, 5, 10, 13 and 16 were predicted to have a high GI absorption while compounds 9, 11, 12, 15 and 21 were predicted to have a low GI absorption. Except compound 1, all compounds were predicted not to pass BBB, indicating their good CNS safety profile.

There are 6 physicochemical characters that were considered in “bioavailability radar” viz, solubility, polarity, lipophilicity, saturation, flexibility, and size, which construct together a hexagon shape (Supplementary Material). The inner pink colored hexagon indicates the optimal values for acceptable bioavailability. The molecular weights of compounds 1, 3, 5, 10, 13, 16 and 21 are below 500 g/mol while compounds 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15 and 19 have molecular weights above 500 g/mol. Consequently, compounds 1, 3, 5, 10, 13, 15, 16, 19 and 21 have satisfied Lipinski rule without any violation. Compounds 1, 3, 4, 10, 13, 15, 16 and 21 have acceptable Fraction Csp3 (>0.03) that improves instauration parameter. All compounds have rotatable bonds within the allowed range (<8 bond) that enhance their flexibility. To conclude, we can say that compounds 1, 3, 4, 10, 13, 15, 16 and 21 are predicted to have acceptable bioavailability.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Chemistry

Kofler Block instrument was utilized to determine the melting points of the prepared compounds. The FTIR 5300 spectrometer (ν, cm−1) was used to record IR spectra. In addition, 1H and 13C NMR spectra were performed by a Varian Gemini spectrometer (400 and 100 MHz, respectively) in DMSO‑d6 as solvents. Tetramethylsilane (TMS), was used as an internal reference, is used to express the chemical changes in parts per million (ppm). 1000 EX mass spectrometer at 70 eV. Using n-hexane and EtOAc, thin layer chromatography (TLC) on aluminum sheets was used to determine the purity of the produced compounds. The elemental analyses were carried out at Microanalytical Research Center, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Egypt.

3.1.1. 2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethylidene)-5,5-dimethylcyclohexane-1,3-dione (3)

Dimedone (0.01 mol) and 1 (0.01 mol) were combined and refluxed for 24 h in EtONa (30 mL), then washed with ice/water, let to cool, and acidified with HCl. The formed solid was collected by filtration, and recrystallized from ethanol to yield (3; 66 %) as yellowish brown crystals, m.p.140–142 °C; IR (KBr) ν cm−1 = 3447 (OH), 3063 (CH-aromatic), 2925–2807 (CH-aliphatic), 1712 (C O); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ = 1.30 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.56 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 3.04 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.34 (s, 2H, CH2), 7.21–7.92 (m, 10H, Ar–H), 11.39 (hump, 1H, OH); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ = 23.20, 28.25, 33.50, 42.82, 85.65, 121.58, 125.56, 126.13, 126.13, 128.33, 129.02, 129.37, 131.02, 133.82, 139.32, 150.08, 154.32, 171.53, 194.40; MS = m/z (%) 401 (M++1). Anal. calcd. for C25H24N2O3 (400): C, 74.98; H, 6.04; N, 7.00; Found: C, 74.12; H, 6.08; N, 7.03 %.

3.1.2. 2-Amino-4-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-4,7,7-trimethyl-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile (5)

In the presence of EtONa (30 mL), malononitrile (0.01 mol) was added to compound 3 (0.01 mol). For 30 h, the reaction mixture was heated under reflux, washed with ice-cold water, then acidified with HCl. The formed solid was collected by filtration, dried, and recrystallized from ethanol to produce (5; 61 %) as yellowish-brown crystals, m.p.110–112 °C; IR = 3449 (OH), 3400 (NH2), 3062 (CH-aromatic), 2956–2926 (CH-aliphatic), 2198 (CN), 1710 (C O); 1H NMR = 0.94 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.51 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.62 (s, 2H, CH2), 6.02 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.29–7.83 (m, 10H, Ar–H), 14.49 (s, 1H, OH); 13C NMR = 19.60, 23.02, 28.25, 28.25, 33.50, 42.62, 54.66, 116.86, 118.83, 121.60, 125.55, 126.16, 128.35, 129.03, 129.38, 129.46, 131.02, 133.76, 139.27, 150.09, 154.44, 162.01, 199.9; MS = m/z (%) 466 (M+). Anal. calcd. for C28H26N4O3 (466): C, 72.09; H, 5.62; N, 12.01; Found: C, 72.14; H, 5.67; N, 12.05 %.

3.1.3. 4,4'-(1,4-phenylene)bis(2-amino-6-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)nicotinonitrile) (7)

Method A: A solution of 1 (0.02 mol), malononitrile (0.02 mol), and terephthaldehyde (0.01 mol) in glacial AcOH (15 mL) and ammonium acetate (2 g). The solution was heated for 24 h at reflux while being stirred. The finished solution was cooled before being poured over crushed ice. The solid formed was filtered off, then recrystallized from dioxane to give (7; 74 %). Method B: A combined solution of 1 (0.02 mol) and 2,2'-(1,4-phenylenebis(methan-1-yl-1-ylidene))dimalononitrilein 6 (0.01 mol). The solution was heated for 24 h while being stirred under reflux. The product obtained was treated with ice-cold water, filtered, dried and recrystallized from dioxane to furnish (7; 74 %) as yellow crystals; m.p. 268–270 °C; IR = 3461 (OH), 3328 (NH2), 3058 (CH-aromatic), 2195 (CN); 1H NMR = 5.24 (s, 2H, 5H-Pyridine), 6.10 (s, 4H, 2NH2), 7.12–7.90 (m, 24, Ar–H), 14.49 (hump, 2H, 2OH); 13C NMR = 98.06, 106.02, 111.01, 121.28, 121.87, 125.55, 126.93, 127.33, 128.67, 129.42, 129.88, 131.33, 132.40, 137.80, 145.61, 146.80, 154.40, 159.16, 160.01; MS: m/z (%) 780 (M+). Anal. calcd. for C48H32N10O2 (780): C, 73.83; H, 4.13; N, 17.94; Found: C, 73.88; H, 4.17; N, 17.99 %.

3.1.4. 4,4'-(4-(4-methoxyphenyl)pyridine-2,6-diyl)bis(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol) (8)

A solution of glacial AcOH (15 mL) containing ammonium acetate (2 g) was mixed with a suspension of 1 (0.02 mol) and p-methoxybenzaldhyde (0.01 mol). The mixture was heated under reflux at 160 °C for 24 h while being stirred, then treated with ice-cold water. The solid product was collected by filtration, and dried then recrystallized from ethanol to furnish (8; 66 %) as yellow powder; m.p.128–130 °C. IR = 3449 (OH), 3060 (CH-aromatic), 2931 (CH-aliphatic); 1H NMR = 3.71 (s, 3H, OCH3), 5.23 (s, 2H, 3-H and 5-H of pyridine ring), 6.87–7.84 (m, 24H, Ar–H), 14.32 (s, 2H, 2OH); 13C NMR = 55.44, 106.96, 114.32, 115.32, 121.79, 126.72, 128.40, 128.58, 129.18, 129.18, 129.46, 133.86, 137.66, 145.80, 149.49, 152.03, 158.17, 165.01; MS: m/z % 653 (M+). Anal. calcd for C42H31N5O3 (653): C, 77.17; H, 4.78; N, 10.71; Found: C, 77.24; H, 5.82; N, 10.73 %.

3.1.5. 1,3-bis(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)but-2-en-1-one (9)

A molar equivalent of 1 (0.02 mol) in 30 mL of EtONa. For 3 h, the mixture was refluxed, then left to cool. The mixture was poured into ice-cold water, and acidified with HCl. The solid formed was collected by filtration, dried and recrystallized from ethanol to give the desired product (9; 49 %) as yellow powder; m.p.130–132 °C; IR = 3450 (OH), 3059 (CH-aromatic), 2955 (CH-aliphatic), 1710 (C O); 1H NMR = 1.90 (s, 3H, CH3), 5.28 (s, 1H, CH-olefinic), 6.89–7.87 (m, 20, Ar–H), 14.38 (hump, 2H, 2 OH); MS = m/z (%) 538 (M+). Anal. calcd. for C34H26N4O3 (538): C, 75.82; H, 4.87; N, 10.40; Found: C, 75.89; H, 4.92; N, 10.42 %.

3.1.6. 2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethylidene)malononitrile (10)

In the presence of EtONa (30 mL), malononitrile (0.01 mol) was added to 1 (0.01 mol). For 1 h, the mixture was refluxed, then left to cool before being treated with crushed ice and acidified with HCl. The solid formed was collected by filtration, and recrystallized from ethanol to yield (10; 66 %) as yellow crystals; m.p.164–166 °C; IR = 3450 (OH), 3063 (CH-aromatic), 2955 (CH-aliphatic), 2192 (CN); 1H NMR = 2.40 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.27–7.84 (m, 10H, Ar–H), 10.50 (s, 1H, OH); MS = m/z (%) 326 (M+). Anal. calcd. For C20H14N4O (326): C, 73.61; H, 4.32; N, 17.17; Found: C, 73.64; H, 4.36; N, 17.23 %.

3.1.7. 2-Amino-4,6-bis(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)benzonitrile (12)

Method A: In the presence of EtONa (30 mL), malononitrile (0.01 mol) was added to 9 (0.01 mol). For 24 h, the solution was refluxed. Once it had stopped, it was treated with ice-cold water then acidified with HCl. The solid formed was collected and recrystallized from ethanol to furnish (12; 66 %). Method B: compounds 1 (0.01 mol) and 10 (0.01 mol) were mixed together in (30 mL) of EtONa. For 24 h, the solution was heated under reflux. After completion the reaction, a cold diluted HCl was added to the reaction mixture, and the solid precipitated was filtered off, and recrystallized from ethanol to produce (12; 68 %) as yellow crystals; m.p.202–204 °C; IR = 3387 (OH), 3302 (NH2), 3059 (CH-aromatic), 2206 (CN); 1H NMR = 6.03 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.27–7.84 (m, 22H, Ar–H), 11.79 (s, 2H, 2OH); 13C NMR = 85.27, 114.90, 116.10, 118.37, 122.51, 125.16, 127.85, 128.54, 128.54, 128.83, 128.89, 133.35, 138.36, 142,00 143.80, 145.63, 149.63, 153.97; MS = m/z (%) 586 (M+). Anal. calcd. for C37H26N6O2 (586): C, 75.75; H, 4.47; N, 14.33; Found: C, 75.78; H, 4.50; N, 14.36 %.

3.1.8. 2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinecarbothioamide (13)

Thiosemicarbazide (0.01 mol) and 1 (0.01 mol) were refluxed for 7 h in (20 mL) absolute ethanol with 2 drops of HCl. After completion the reaction, the solid precipitated was collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol to yield (13; 75 %) as yellowish-white crystals; m.p.170–172 °C. IR = 3449 (OH), 3300 (NH2), 3062 (CH-aromatic), 2833 (CH-aliphatic); 1H NMR = 1.84 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.04 (s, 2H, NH2) 7.22–7.85 (m, 10H, Ar–H), 8.66 (s, 1H, NH), 11.60 (hump, 1H, OH); MS = m/z (%) 353 (M++2). Anal. calcd. for C18H17N5OS (351): C, 61.52; H, 4.88; N, 19.93; Found: C, 61.59; H, 4.92; N, 19.97 %.

3.1.9. 2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl) hydrazono)thiazol-4(5H)-one (15)

Method A: In dioxane (30 mL) containing 3 drops of TEA, a suspension of 13 (0.01 mol) and ethyl 2-chloro-2-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl) hydrazono)acetate 14 (0.01 mol) was refluxed for 24 h. After allowing the solution to stop, a cold diluted HCl was added to the mixture. The solid formed was filtered off, dried, then recrystallized from ethanol to afford (15; 75 %). Method B: Aryldiazonium chloride 17 was added dropwise to a cold solution of 16 (0.01 mol) in ethanol (20 mL) containing excess of sodium acetate (2 gm). After completion the addition, the reaction mixture was allowed to stirrer for further 1 h in ice bath, then left overnight. The solid formed was collected by filtration, and recrystallized from ethanol to yield (15; 82 %) as yellowish brown crystals, m.p.120–122 °C. IR = 3300 (OH), 3128 (NH), 3028 (CH-aromatic), 2881 (CH-aliphatic), 1685 (C O); 1H NMR = 1.24 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.80 (s, 3H, OCH3). 6.02 (s, 1H, NH), 6.50 (s, 1H, NH), 7.25–8.05 (m, 14H, Ar–H), 14.90 (s, 1H, OH); MS = m/z (%) 527 (M++2). Anal. calcd. for C27H23N7O3S (525): C, 61.70; H, 4.41; N, 18.65; Found: C, 61.75; H, 4.46; N, 18.70 %.

3.1.10. 2-(2-(1-(5-hydroxy-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethylidene)hydrazinyl)thiazol-4(5H)-one (16)

In a round flask containing glacial AcOH (10 mL) and sodium acetate (1 g), a suspension of 13 (0.01 mol) and chloroacetic acid and/or ethyl chloroacetate (0.01 mol) was added, and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 24 h. After completion the reaction (monitored by TLC), a cold diluted HCl was added to the mixture. The solid precipitated was collected by filtration, washed with water and crystallized from ethanol (16; 75 %) as yellow crystals, m.p.120–122 °C; IR = 3450 (OH), 3052 (CH-aromatic), 2955 (CH-aliphatic), 1709 (C O); 1H NMR = 1.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 5.02 (s, 2H, CH2), 6.06 (s, 1H, NH), 7.28–7.86 (m, 10H, Ar–H), 11.80 (hump, 1H, OH); 13C NMR = 14.01, 60.21, 85.05, 121.7, 126.12, 127.83, 127.83, 128.91, 129.01, 129.01, 129.07, 129.07, 133.36, 138.87, 153.95, 154.39, 163.02, 167.70, 170.01; MS = m/z (%) 393(M++2). Anal. calcd. for C20H17N5O2S (391): C, 61.37; H, 4.38; N, 17.89; Found: C, 61.40; H, 4.41; N, 17.92 %.

3.1.11. 4-(-1-(5-(4-methoxyphenyl)diazenyl)-4-phenylthiazol-2(3H)-ylidene)hydrazono)ethyl)-1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ol (19)

Method A: A mixture of 13 (0.01 mol) and N'-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2-oxo-2-phenylaceto hydrazonoyl bromide 18 (0.01 mol) in dioxane (20 mL) and 3 drops of TEA was heated under reflux for 24 h. After completion the reaction (monitored by TLC), a cold diluted HCl was added to the mixture. The solid formed was collected by filtration, then recrystallized from ethanol to give (19; 75 %). Method B: A portion of the aryldiazonium chloride 17 solution was added dropwise to a cold solution of 21 (0.01 mol) in ethanol (20 mL) and excess of sodium acetate (2 g). The mixture was allowed to stirrer for 1 h in an ice bath. After completion the addition, the solid precipitated was filtered off, and recrystallized from ethanol to yield (19; 82 %) as yellow crystals, m.p. 240–242 °C. IR = 3392 (OH), 3300 (NH), 3056 (CH-aromatic), 2955 (CH-aliphatic); 1H NMR = 1.20 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.79 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.20 (s, 1H, NH), 7.06–8.19 (m, 19H, Ar–H), 13.86 (hump, 1H, OH); 13C NMR = 20.47, 55.89, 85.34, 93.98, 118.40, 118.40, 121.14, 122.25, 122.25, 126.14, 127.47, 127.47, 127.87, 128.33, 128.33, 128.33, 128.56, 128.56, 128.81, 128.81, 128.9, 128.9, 129.41, 129.41, 132.69, 133.4, 137.67, 144.96, 149.69, 149.98, 154.05, 166.63, 172.70; MS = m/z (%) 587 (M++2). Anal. calcd. for C33H27N7O2S (585): C, 67.67; H, 4.65; N, 16.74; Found: C, 67.70; H, 4.68; N, 16.77 %.

3.1.12. 1,3-Diphenyl-4-(1-(2-(4-phenylthiazol-2-yl)hydrazono)ethyl)-1H-pyrazol-5-ol (21)

A mixture of 13 (0.01 mol) and phenacyl bromide 20 (0.01 mol) was dissolved in absolute ethanol (20 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h before being refluxed for 20 h. After completion the reaction, ice-cold water was added to the mixture. The solid formed was collected by filtration, and recrystallized from ethanol to afford the desired product (21; 75 %) as brown crystals, m.p.100–102 °C. IR = 3450 (OH), 3400 (NH), 3058 (CH-aromatic), 2955 (CH-aliphatic); 1H NMR = 1.10 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.04 (s, 1H, NH), 7.27–7.84 (m, 16H, Ar–H), 14.57 (s, 1H, OH); MS = m/z (%) 453 (M++2). Anal. calcd. for C26H21N5OS (451): C, 68.85; H, 5.11; N, 15.44; Found: C, 68.89; H, 5.15; N, 15.48 %.

3.2. Antimicrobial efficacy of the tested compounds

The ability of the molecules to prevent the microbial growth was investigated against the standard pathogen strains, gram -ive bacteria (P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia), gram + ive bacteria (S. aureus, B. subtilis), and Unicellular fungi (C. albicans). Pre-activation of pathogens were performed by inoculating in the Nutrient broth medium for 24 h at 37 °C for bacterial strains, while fungal pathogen was inoculating in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) medium for 48 h at 28 °C under shaking condition. Screening of the tested material with different concentrations was preliminary occur at a constant concentration of the tested compounds using turbidometry method for each microbial pathogen except for multicellular fungi, which was evaluated by the Colony Forming Unite (CFU). In addition, the evaluation of tested compounds to inhibition the microbial proliferation was assessed using agar well diffusion method in terms of the inhibition zone diameter (mm) [44,45].

3.2.1. Determination of minimum inhibition concentration (MIC)

The MIC of highly potent molecules were performed to estimate the lowest concentration that inhibit the visible microbial growth after 24 h applying microdilution assay technique according to CLSI [46,47]. In the experiment, different concentrations of the tested molecules were investigated in comparison to the classical antimicrobial agents. Briefly, the tested pathogens were cultivated in Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) at 37 °C for 24 h, then the growth was diluted with sterilized bi-distilled water corresponding to 2 × 107 Colony Forming Unit (CFU)/mL, and the prepared cultures were diluted 10-folds in MHB for used as inoculum. The selected molecules were added into 100 μL aliquots into MHB, which were sequentially dispensed into the microdilution (96-well microtiter plate) in order to determine a known concentrations ranging from 5 to 200 μg/ml. A known inoculum of the bacterial cells was then incorporated with 100 μL to each well in triplicate trails. The positive control using three antibacterial agents was adjusted with the same concentrations of the tested samples [24,48]. The MHB mixed with DMSO without and with compounds were also served as the control samples.

3.3. Molecular docking assessment

Modeling simulations that included docking study of the synthesized compounds were achieved. At first, the native ligand, moxifloxacin, was redocked with the active region of target protein (PDB ID: 5BS8) to validate our docking methodology (RMSD = 0.9812) [49]. After that a library of 2D structures of the prepared derivatives and moxifloxacin were sketched using ChemDraw Professional 16.0, then converted to mol format. The energies of compounds and moxifloxacin were minimized and organized. The 3D structure of the target protein was prepared by removing solvent molecules and bound substances (ligands and cofactors). Docking process was conducted by default setting of MOE software [40]. SwissADME website [50] was utilized to estimate several physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of molecules.

4. Conclusion

Two hybrid series of pyrazole-clubbed pyrimidine and pyrazole-clubbed thiazole compounds were prepared and in vitro screened for their antimicrobial activities against various standard pathogen strains. Moreover, the docking approach was achieved for understanding the antimicrobial efficacy in terms of binding affinity and intermolecular interactions with DNA gyrase enzyme. The findings revealed that compounds 7, 8, 12, 13 and 19 are considered as hopeful antimicrobial agents and could be the lead compounds for potential drug candidates.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the Supplementary Material File.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed A.M. Abdel Reheim: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision. Ibrahim S. Abdel Hafiz: Writing – original draft, Supervision. Hala M. Reffat: Writing – original draft, Supervision. Hend S. Abdel Rady: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. Ihsan A. Shehadi: Formal analysis, Data curation. Huda R.M. Rashdan: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. Abdelfattah Hassan: Writing – original draft, Software. Aboubakr H. Abdelmonsef: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33160.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Huttner A., Harbarth S., Carlet J., Cosgrove S., Goossens H., Holmes A., Jarlier V., Voss A., Pittet D. Antimicrobial resistance: a global view from the 2013 world healthcare-associated infections forum. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2013;2:31. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall W., McDonnell A., O'Neill J. Superbugs. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018;6:668. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv2867t5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bin Zaman S., Hussain M.A., Nye R., Mehta V., Mamun K.T., Hossain N. A review on antibiotic resistance: alarm bells are ringing. Cureus. 2017;9 doi: 10.7759/cureus.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isenbarger D.W., Hoge C.W., Srijan A., Pitarangsi C., Vithayasai N., Bodhidatta L., Hickey K.W., Cam P.D. Comparative antibiotic resistance of diarrheal pathogens from Vietnam and Thailand, 1996-1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:175–180. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrar W.E., Eidson M. Antibiotic resistance in Shigella mediated by R factors. J. Infect. Dis. 1971;123:477–484. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mey A.R., Gómez-Garzón C., Payne S.M. Iron transport and metabolism in Escherichia, Shigella, and Salmonella. EcoSal Plus. 2021;9 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0034-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoge C.W., Gambel J.M., Srijan A., Pitarangsi C., Echeverria P. Trends in antibiotic resistance among diarrheal pathogens isolated in Thailand over 15 years. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998;26:341–345. doi: 10.1086/516303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uddin M.S., Rahman M.M., Faruk M.O., Talukder A., Hoq M.I., Das S., Islam K.M.S. Bacterial gastroenteritis in children below five years of age: a cross-sectional study focused on etiology and drug resistance of Escherichia coli O157, Salmonella spp., and Shigella spp. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021;45:138. doi: 10.1186/s42269-021-00597-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laxminarayan R., Duse A., Wattal C., Zaidi A.K.M., Wertheim H.F.L., Sumpradit N., Vlieghe E., Hara G.L., Gould I.M., Goossens H., Greko C., So A.D., Bigdeli M., Tomson G., Woodhouse W., Ombaka E., Peralta A.Q., Qamar F.N., Mir F., Kariuki S., Bhutta Z.A., Coates A., Bergstrom R., Wright G.D., Brown E.D., Cars O. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma R., Verma S.K., Rakesh K.P., Girish Y.R., Ashrafizadeh M., Sharath Kumar K.S., Rangappa K.S. Pyrazole-based analogs as potential antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its SAR elucidation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;212 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelmonsef A.H., Mosallam A.M. Synthesis, in vitro biological evaluation and in silico docking studies of new quinazolin-2,4-dione analogues as possible anticarcinoma agents. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020;57:1637–1654. doi: 10.1002/jhet.3889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Naggar M., Rashdan H.R.M., Abdelmonsef A.H. Cyclization of chalcone derivatives: design, synthesis, in silico docking study, and biological evaluation of new quinazolin-2,4-diones incorporating five-, six-, and seven-membered ring moieties as potent antibacterial inhibitors. ACS Omega. 2023;8:27216–27230. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.3c02478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussein A.H.M., El-Adasy A.-B.A., El-Saghier A.M., Olish M., Abdelmonsef A.H. Synthesis, characterization, in silico molecular docking, and antibacterial activities of some new nitrogen-heterocyclic analogues based on a p- phenolic unit. RSC Adv. 2022;12:12607–12621. doi: 10.1039/d2ra01794f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelmonsef A.H., Omar M., Rashdan H.R.M., Taha M.M., Abobakr A.M. Design, synthetic approach, in silico molecular docking and antibacterial activity of quinazolin-2,4-dione hybrids bearing bioactive scaffolds. RSC Adv. 2022;13:292–308. doi: 10.1039/d2ra06527d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soltan O.M., Shoman M.E., Abdel-aziz S.A., Narumi A., Konno H., Abdel-aziz M. A five-year survey on structures of multiple targeted hybrids of protein kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;225 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abuelhassan A.H., Badran M.M., Hassan H.A., Abdelhamed D., Elnabtity S., Aly O.M. Design, synthesis, anticonvulsant activity, and pharmacophore study of new 1,5-diaryl-1H-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2018;27:928–938. doi: 10.1007/s00044-017-2114-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashdan H.R.M., Shehadi I.A., Abdelmonsef A.H. Synthesis, anticancer evaluation, computer-aided docking studies, and ADMET prediction of 1,2,3-triazolyl-pyridine hybrids as human aurora B kinase inhibitors. ACS Omega. 2021;6:1445–1455. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c05116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai N.C., Kotadiya G.M., Trivedi A.R., Khedkar V.M., Jha P.C. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel fluorinated pyrazole encompassing pyridyl 1,3,4-oxadiazole motifs. Med. Chem. Res. 2016;25:2698–2717. doi: 10.1007/s00044-016-1683-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassan A., Hassan H.A., Abdelhamid D., El‐Din Abu-Rahma G.A. Synthetic approaches toward certain structurally related antimicrobial thiazole derivatives (2010-2020) Heterocycles. 2021;102 doi: 10.3987/REV-21-956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desai N.C., Jadeja K.A., Jadeja D.J., Khedkar V.M., Jha P.C. Design, synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation, and molecular docking study of some 4-thiazolidinone derivatives containing pyridine and quinazoline moiety. Synth. Commun. 2021;51:952–963. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2020.1861302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebenezer O., Awolade P., Koorbanally N., Singh P. New library of pyrazole–imidazo[1,2-α]pyridine molecular conjugates: synthesis, antibacterial activity and molecular docking studies. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2020;95:162–173. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohamed H.A., Ammar Y.A., Elhagali G.A.M., Eyada H.A., Aboul-Magd D.S., Ragab A. Discovery a novel of thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine and pyrazolo[3,4-d]thiazole derivatives as DNA gyrase inhibitors; design, synthesis, antimicrobial activity, and some in-silico ADMET with molecular docking study. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1287 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Saghier A.M., El-Naggar M., Hussein A.H.M., El-Adasy A.B.A., Olish M., Abdelmonsef A.H. Eco-friendly synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico molecular docking approach of some new quinoline derivatives as potential antioxidant and antibacterial agents. Front. Chem. 2021;9:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.679967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashdan H.R.M., Abdelmonsef A.H., Abou-Krisha M.M., Yousef T.A. Synthesis, identification, computer-aided docking studies, and ADMET prediction of novel benzimidazo-1,2,3-triazole based molecules as potential antimicrobial agents. Molecules. 2021;26:7119. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibrahim A.O.A., Hassan A., Mosallam A.M., Khodairy A., Rashdan H.R.M., Abdelmonsef A.H. New quinazolin-2,4-dione derivatives incorporating acylthiourea, pyrazole and/or oxazole moieties as antibacterial agents via DNA gyrase inhibition. RSC Adv. 2024;14:17158–17169. doi: 10.1039/D4RA02960G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaaban S., Al-Faiyz Y.S., Alsulaim G.M., Alaasar M., Amri N., Ba-Ghazal H., Al-Karmalawy A.A., Abdou A. Synthesis of new organoselenium-based succinanilic and maleanilic derivatives and in silico studies as possible SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. INORGA. 2023;11 doi: 10.3390/inorganics11080321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaaban S., Abdou A., Alhamzani A.G., Abou-Krisha M.M., Al-Qudah M.A., Alaasar M., Youssef I., Yousef T.A. Synthesis and in silico investigation of organoselenium-clubbed schiff bases as potential mpro inhibitors for the SARS-CoV-2 replication. Life. 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/life13040912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abd El-Lateef H.M., Khalaf M.M., Kandeel M., Amer A.A., Abdelhamid A.A., Abdou A. Designing, characterization, biological, DFT, and molecular docking analysis for new FeAZD, NiAZD, and CuAZD complexes incorporating 1-(2-hydroxyphenylazo)− 2-naphthol (H2AZD) Comput. Biol. Chem. 2023;105 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2023.107908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abd El-Lateef H.M., Khalaf M.M., Kandeel M., Amer A.A., Abdelhamid A.A., Abdou A. New mixed-ligand thioether-quinoline complexes of nickel(II), cobalt(II), and copper(II): synthesis, structural elucidation, density functional theory, antimicrobial activity, and molecular docking exploration. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2023;37 doi: 10.1002/aoc.7134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abd M., Aleem E., Ali A., Elhady O., Abdou A., Alhashmialameer D., Nady T., Eskander A., Abu-dief A.M. Development of new 2- (Benzothiazol-2-ylimino) -2 , 3-dihydro-1H-imidazole-4-ol complexes as a robust catalysts for synthesis of thiazole 6-carbonitrile derivatives supported by DFT studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1292 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.136188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abu-Dief A.M., El-Khatib R.M., El‐Dabea T., Abdou A., Aljohani F.S., Al-Farraj E.S., Barnawi I.O., El-Remaily M. Fabrication, structural elucidation of some new metal chelates based on N-(1H-Benzoimidazol-2-yl)-guanidine ligand: DNA interaction, pharmaceutical studies and molecular docking approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2023;386 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2023.122353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel Reheim M.A.M., Baker S.M. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro antimicrobial activity of novel fused pyrazolo[3,4-c]pyridazine, pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine, thieno[3,2-c]pyrazole and pyrazolo[3’,4’:4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives. Chem. Cent. J. 2017;11:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13065-017-0339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdelrazek F.M., Gomha S.M., Abdel-aziz H.M., Farghaly M.S., Metz P., Abdel-Shafy A. Efficient synthesis and in Silico study of some novel pyrido[2,3-d][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrimidine derivatives. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020;57:1759–1769. doi: 10.1002/jhet.3901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rashdan H.R.M., Shehadi I.A., Abdelmonsef A.H. Synthesis, anticancer evaluation, computer-aided docking studies, and ADMET prediction of 1,2,3-triazolyl-pyridine hybrids as human aurora B kinase inhibitors. ACS Omega. 2021 doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c05116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra R., Yuan L., Patel H., Karve A.S., Zhu H., White A., Alanazi S., Desai P., Merino E.J., Garrett J.T. Phosphoinositide 3‐kinase (Pi3k) reactive oxygen species (ros)‐activated prodrug in combination with anthracycline impairs pi3k signaling, increases dna damage response and reduces breast cancer cell growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdallah M.A., Gomha S.M., Abbas I.M., Kazem M.S.H., Alterary S.S., Mabkhot Y.N. An efficient synthesis of novel pyrazole-based heterocycles as potential antitumor agents. Appl. Sci. 2017;7 doi: 10.3390/app7080785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenchappa R., Bodke Y.D., Chandrashekar A., Telkar S., Manjunatha K.S., Aruna Sindhe M. Synthesis of some 2, 6-bis (1-coumarin-2-yl)-4-(4-substituted phenyl) pyridine derivatives as potent biological agents. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:S1336–S1344. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohamed H.M., Abd El-Wahab A.H.F., Ahmed K.A., El-Agrody A.M., Bedair A.H., Eid F.A., Khafagy M.M. Synthesis, reactions and antimicrobial activities of 8-ethoxycoumarin derivatives. Molecules. 2012;17:971–988. doi: 10.3390/molecules17010971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomha S.M., Abdelhady H.A., Hassain D.Z., Abdelmonsef A.H., El-Naggar M., Elaasser M.M., Mahmoud H.K. Thiazole-Based thiosemicarbazones: synthesis, cytotoxicity evaluation and molecular docking study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021;15:659–677. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S291579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassan A., Mosallam A.M., Ibrahim A.O.A., Badr M., Abdelmonsef A.H. Novel 3-phenylquinazolin-2,4(1H,3H)-diones as dual VEGFR-2/c-Met-TK inhibitors: design, synthesis, and biological evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2023;13 doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45687-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdelmonsef A.H., El-Saghier A.M., Kadry A.M. Ultrasound-assisted green synthesis of triazole-based azomethine/thiazolidin-4-one hybrid inhibitors for cancer therapy through targeting dysregulation signatures of some Rab proteins. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2023;16 doi: 10.1080/17518253.2022.2150394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latif M.A., Ahmed T., Hossain M.S., Chaki B.M., Abdou A., Kudrat-E-Zahan M. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, DFT calculations, antibacterial activity, and molecular docking analysis of Ni(II), Zn(II), Sb(III), and U(VI) metal complexes derived from a nitrogen-sulfur schiff base. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023;93:389–397. doi: 10.1134/S1070363223020214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohammed H.H.H., Abdelhafez E.-S.M.N., Abbas S.H., Moustafa G.A.I., Hauk G., Berger J.M., Mitarai S., Arai M., Abd El-Baky R.M., Abuo-Rahma G.E.-D.A. Design, synthesis and molecular docking of new N-4-piperazinyl ciprofloxacin-triazole hybrids with potential antimicrobial activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;88 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Hashash M.A., Sherif S.M., Badawy A.A., Rashdan H.R. Synthesis of some new antimicrobial 5, 6, 7, 8-tetrahydro-pyrimido [4, 5-b] quinolone derivatives. Der Pharma Chem. 2014;6:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabt A., Abdelrahman M.T., Abdelraof M., Rashdan H.R.M. Investigation of novel mucorales fungal inhibitors: synthesis, in‐silico study and anti‐fungal potency of novel class of coumarin‐6‐sulfonamides‐thiazole and thiadiazole hybrids. ChemistrySelect. 2022;7 doi: 10.1002/slct.202200691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rashdan H.R.M., Abdel-Aziem A., El-Naggar D.H., Nabil S. Synthesis and biological evaluation of some new pyridines, isoxazoles and isoxazolopyridazines bearing 1,2,3-triazole moiety. Acta Pol. Pharm. - Drug Res. 2019;76:469–482. doi: 10.32383/appdr/103101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rashdana H.R.M., Nasrb S.M., El-Refaia H.A., Abdel-Azizc M.S. A novel approach of potent antioxidant and antimicrobial agents containing coumarin moiety accompanied with cytotoxicity studies on the newly synthesized derivatives. J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;7:186–196. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2017.70727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qader M.M., Hamed A.A., Soldatou S., Abdelraof M., Elawady M.E., Hassane A.S.I., Belbahri L., Ebel R., Rateb M.E. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of the fungal metabolites isolated from the marine endophytes epicoccum nigrum M13 and Alternaria alternata 13A. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:232. doi: 10.3390/md19040232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hassan A., Mubarak F.A.F., Shehadi I.A., Mosallam A.M., Temairk H., Badr M., Abdelmonsef A.H. Design and biological evaluation of 3-substituted quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione derivatives as dual c-Met/VEGFR-2-TK inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023;38 doi: 10.1080/14756366.2023.2189578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guex N., Peitsch M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the Supplementary Material File.