Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcriptional regulator Tat increases the efficiency of elongation, and complexes containing the cellular kinase CDK9 have been implicated in this process. CDK9 is part of the Tat-associated kinase TAK and of the elongation factor P-TEFb (positive transcription elongation factor-b), which consists minimally of CDK9 and cyclin T. TAK and P-TEFb are both able to phosphorylate the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II, but their relationships to one another and to the stimulation of elongation by Tat are not well characterized. Here we demonstrate that human cyclin T1 (but not cyclin T2) interacts with the activation domain of Tat and is a component of TAK as well as of P-TEFb. Rodent (mouse and Chinese hamster) cyclin T1 is defective in Tat binding and transactivation, but hamster CDK9 interacts with human cyclin T1 to give active TAK in hybrid cells containing human chromosome 12. Although TAK is phosphorylated on both serine and threonine residues, it specifically phosphorylates serine 5 in the CTD heptamer. TAK is found in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of human cells as a large complex (∼950 kDa). Magnesium or zinc ions are required for the association of Tat with the kinase. We suggest a model in which Tat first interacts with P-TEFb to form the TAK complex that engages with TAR RNA and the elongating transcription complex, resulting in hyperphosphorylation of the CTD on serine 5 residues.

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) regulatory protein Tat, the transactivator of transcription, dramatically increases the production of viral RNA (for a review, see reference 26). This effect is dependent on the transactivation response element (TAR) located downstream of the promoter in the HIV long terminal repeat (LTR). TAR is an RNA element, and TAR RNA binds directly to Tat (17, 72). Although Tat may also exert a stimulatory effect on transcriptional initiation, its predominant effect in vivo appears to be at the level of transcriptional elongation (42, 46, 47). In one model, Tat serves to promote the formation of highly processive RNA polymerase complexes at the HIV LTR. In the absence of Tat, HIV-directed transcripts tend to terminate prematurely at apparently random sites (45). This model is supported by experiments conducted with cell-free transcription systems (28, 44, 50, 51). A unique feature of the stimulation of HIV-directed transcription in vitro is the observation that it is preferentially inhibited by 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB), an adenosine analogue that targets RNA polymerase II (pol II)-mediated elongation in vitro and in vivo (5, 51).

Efforts to uncover the mechanism of Tat action have included extensive searches for cellular components that interact with Tat in vivo and in vitro. This approach disclosed structural and functional interactions with several general transcription factors as well as other proteins with as-yet-unknown roles in transcription (8, 23, 38, 41, 43). Outstanding among these Tat-interacting proteins is a novel Tat-associated protein kinase, TAK, found by Herrmann and Rice (35, 36). This kinase is able to phosphorylate the carboxy-terminal repeat domain (CTD) of pol II and is highly sensitive to DRB.

The mammalian CTD consists of a series of 52 heptad repeats, YSPTSPS, located on the large subunit of pol II. It participates in gene expression at several levels and appears to coordinate the machinery of transcription and posttranscriptional RNA processing (37, 55, 57). The CTD can be extensively phosphorylated at multiple sites, predominantly on serine but also on threonine and tyrosine residues (11). Its phosphorylation plays a dominant role in transcription regulation: the hyperphosphorylated form of the large subunit (IIo) is associated with transcription elongation complexes, while only the hypomodified form (IIa) can assemble into the preinitiation complex (60). During the transition from initiation to elongation, or soon after, IIa is converted to IIo (10). The role of the CTD in transcription is not entirely understood, however, and it is possible that more than one round of phosphorylation is required, perhaps with intervening dephosphorylation. The CTD is essential for cell viability in yeast and for transcription from TATA-less promoters in vitro but is nonessential for TATA-containing promoters in vitro (1, 48, 59, 70). It is required for Tat transactivation (7, 61, 75).

At least 10 kinases which can phosphorylate the CTD in vitro are known, and 3 of them have an established connection with the transcription machinery. These are CDK7/cyclin H, subunits of the CDK-activating kinase (CAK) complex, which is a subassembly of transcription factor TFIIH; CDK8/cyclin C, a component of the pol II holoenzyme; and CDK9/cyclin T, now identified as components of the positive transcription elongation factor P-TEFb. P-TEFb was first recognized in Drosophila Kc cell extract as an activity needed to overcome abortive elongation and allow formation of long transcripts (53). P-TEFb is distinguished from other transcription factors by its sensitivity to very low doses of DRB (52). It differs from TFIIH, which exhibits less sensitivity to DRB, in that TFIIH functions in initiation and promoter clearance while P-TEFb has the attributes of an elongation factor (18, 53, 54, 62).

The possibility that TAK corresponds to human P-TEFb was suggested by the functional similarity between the stimulation of elongation by Tat and the shift to productive elongation by P-TEFb. Circumstantial support for this inference was provided by the observations that both P-TEFb and TAK are CTD kinases and that low concentrations of DRB inhibit P-TEFb, TAK, and the Tat effect (35, 51–53). Conclusive evidence came when Zhu et al. (80) cloned the catalytic subunit of Drosophila P-TEFb and showed that its human homologue (PITALRE) is identical to the kinase subunit of TAK. PITALRE, now called CDK9 (67, 73), was first cloned by Graña et al. (29) as a CDC2-related kinase of unknown function.

Most of the kinases in this family have cyclin-regulating subunits, and the cyclin partners of human and Drosophila CDK9 were recently cloned and studied (66). The human cyclins T1, T2a, and T2b were all identified as functional partners of CDK9, and almost all of the CDK9 in HeLa nuclear extracts is associated with either cyclin T1 or T2 (67). Cyclin T1 can also bind directly to the activation domain of Tat (73). Several additional proteins are also associated with CDK9 in immunocomplexes (24, 78, 80), suggesting that human P-TEFb is a multiprotein complex or that there are other CDK9-containing complexes in addition to P-TEFb. It is also likely that Tat binds other factors in addition to CDK9/cyclin T (79). The gene for human cyclin T1 maps to chromosome 12, and this chromosome is necessary for a strong Tat effect on transcription from the HIV LTR in mouse and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (73). Transfection of CHO and mouse cells with the cyclin T1 gene overcomes the poor Tat response that was previously noticed in these cells (73). The species specificity of the Tat response is also partially complemented in mouse cells harboring human chromosome 6, but the factor(s) responsible is unknown.

Our study addresses the interaction of CDK9/cyclin T1 with Tat and its CTD substrate. We demonstrate that human Tat-associated P-TEFb contains cyclin T1 and that rodent P-TEFb is deficient in binding to Tat. Human cyclin T1 as part of the P-TEFb complex in CHO cells complements this deficiency and thus contributes to HIV-1 species specificity. We also show that human TAK is part of a large complex that phosphorylates serine 5 in the CTD heptad and is itself phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues. Our data suggest that TAK and CAK differentially phosphorylate the CTD substrate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Nucleoside triphosphates were purchased from Pharmacia-LKB. [γ-32P]ATP was obtained from ICN Pharmaceuticals Inc. Thin-layer cellulose plates were purchased from EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J. Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was from Millipore. CTD3 peptides were synthesized at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey Molecular Resource Facility with an ABI 433A synthesizer and were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography on a C18 column. Affinity-purified anti-CDK9 immunoglobulin G (IgG) (anti-PITALRE-CT) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Drosophila RNA pol II and cyclin T1 and T2 antisera were gifts from D. Price (67, 80).

Cells, plasmids, and viruses.

Rodent-human hybrid cell lines and the parental human lymphoblast cell line (GM07890) were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories, Camden, N.J. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Tat constructs (68) were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institutes of Health, and from the laboratory of K. Jones (GST-Tat–1K41A). Baculoviruses harboring recombinant CDK7, cyclin H, and MAT-1 were gifts from D. Morgan (20, 21).

Preparation of cell extracts.

Cell extracts were prepared essentially as described by Harlow and Lane (31). Cell monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed for 30 min with occasional rocking by using prechilled EBCD buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) containing 4 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 1 μg (each) of aprotinin, pepstatin A, and leupeptin per ml. The lysate was centrifuged for 10 min at 2,500 × g, and the supernatant was collected. Cytoplasmic (S-100) and nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Dignam et al. (15) except that the dialysis step was omitted for the cytoplasmic extract. Glycerol was added to 10%, and the extracts were stored at −80°C. For gel filtration and glycerol gradient experiments, the nuclear extract was clarified by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min in a Beckman SW 50.1 rotor.

Partial purification of TAK.

TAK purification was as described previously (80) with an additional chromatographic step. The peak fractions from the POROS 20 SP column were pooled, and the KCl concentration was adjusted to 100 mM. The pooled fractions were loaded on a Reactive Blue (Sigma) column equilibrated with column buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 4 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors [1 μg {each} of aprotinin, pepstatin A, and leupeptin per ml]) containing 100 mM KCl. The active fractions were eluted in the same buffer containing 0.5 to 1 M KCl.

TAK assay.

The production of GST-Tat fusion proteins and the TAK activity assay were carried out as described by Zhu et al. (80). For nucleotide usage experiments, unlabeled nucleotides were added at various concentrations. The gels were dried, quantified on a Packard Instant Imager, and exposed to X-ray film.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)-kinase assays.

Protein A-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) were washed three times with EBCD buffer and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with anti-CDK9 antibody (0.5 to 1 μg of IgG/10 μl of packed beads). The beads were washed four times with EBCD buffer containing 0.2 mM PMSF, incubated for 1 h with cell extract at 4°C, washed five times with EBCD containing 0.03% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and subjected to a kinase assay as described previously (80).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins from polyacrylamide gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by using the semidry transfer protocol (4). The membranes were blocked for 1 h with blocking buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 2.3% low-fat milk, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.5% NP-40, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated for 4 to 6 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. This was followed by three 10-min washes with TBST (20 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubation for 20 min with blocking buffer. Secondary antibody (Bio-Rad goat anti-rabbit IgG–horseradish peroxidase conjugate) was added to the blocking buffer at a 1:3,000 dilution, and the membranes were incubated for an additional hour. After three 15-min washes with TBST, membranes were reacted with chemiluminescence reagent (NEN Life Science Products) and exposed to Kodak Biomax film.

EDTA-Mg experiments.

EDTA was added to 293 cell S-100 fractions (15 μl [225 μg of protein]) to a final concentration of 5 or 10 mM in a total volume of 100 μl of EBCD buffer containing 0.2 mM PMSF. After incubation at room temperature for 5 to 30 min, MgCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 or 20 mM. The samples were incubated for an additional 5 to 30 min at room temperature, after which they were added to 50 μl of beads containing GST-Tat48Δ in EBCD buffer without magnesium; this was followed by the standard TAK assay. Thus, the final concentrations of MgCl2 and EDTA were two-thirds of those specified.

Phosphoamino acid analysis.

Phosphoamino acid analysis was performed essentially as described by Ausubel et al. (4). Briefly, phosphorylated peptide and CDK9 were transferred from gels to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, hydrolyzed in 6 M HCl, dried in a vacuum, and resuspended in 2 to 5 μl of water. In some experiments, the membranes were treated with alkali before acid hydrolysis. A portion of the digest containing 1,000 to 5,000 cpm was spotted on a cellulose thin-layer chromatography plate, and 1 μl of a solution containing about 1 μg of each unlabeled phosphoamino acid was spotted as a reference. The amino acids were resolved by two-dimensional electrophoresis (HTLE 7000; CBS Scientific). The amino acid standards were visualized by ninhydrin staining, and 32P-labeled amino acids were detected by autoradiography and quantified with a Packard Instant Imager.

Expression of recombinant CDK7 complexes and preparation of Sf9 cell extracts.

Monolayers of Sf9 insect cells (2 × 107 cells) were infected with recombinant baculoviruses harboring the gene for CDK7 or cyclin H or with a mixture of viruses encoding the CAK complex (CDK7, cyclin H, and MAT-1) at a multiplicity of infection of 5 to 10 PFU/cell. Two days after infection, the cells were lysed in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 μg of leupeptin per ml), NaCl was added to a 150 mM final concentration, and the lysates were clarified by centrifugation.

Fractionation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts.

Nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts were diluted into 0.5 ml of HKMEG column running buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 150 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 1 μg [each] of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A per ml) and applied to a 45-ml column of Sephacryl S-300 Superfine (Pharmacia) equilibrated in the same buffer. The void volume was determined by using blue dextran, the column was calibrated by using the high-molecular-mass marker kit from Sigma (MW GF-100), and the molecular masses of complexes were determined by extrapolation. Fractions (0.5 ml) were collected at flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Glycerol gradient ultracentrifugation was carried out in 4 ml of a 20 to 50% glycerol gradient in HKMEG buffer. Nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts (3 mg of protein) were diluted into 0.2 ml of HKMEG and loaded on the gradient. An identical gradient was loaded with high-molecular-weight marker proteins, and both gradients were centrifuged at 45,000 rpm for 18 h in a Beckman SW 50.1 rotor. Fractions (0.1 ml) were collected by pumping from the bottom of each tube.

RESULTS

Association of CTD kinase with HIV-1 Tat.

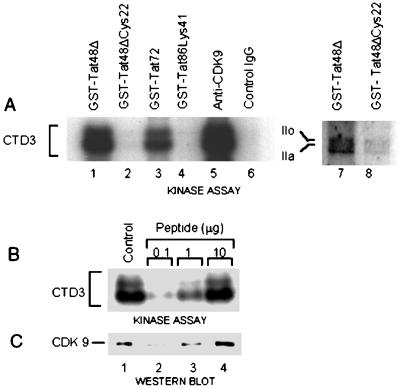

The Tat-associated kinase TAK binds to full-length Tat (Tat86), first-exon Tat (Tat72), or its activation domain (Tat48Δ) and hyperphosphorylates a model substrate, GST-CTD (35). We used the TAK assay, a GST-Tat pull-down kinase assay, to examine the interactions of TAK with its substrates and different GST-Tat fusion proteins. Figure 1A shows that TAK phosphorylates intact pol II (lane 7), as well as a synthetic peptide, CTD3 [ACS(YSPTSPS)3KK], containing three copies of the CTD heptad (lanes 1 and 3). TAK binding requires all three regions of the activation domain and is abolished by mutations in the cysteine-rich region (Tat48ΔCys22) (lanes 2 and 8), the core region (Tat86Lys41) (lane 4), and the N terminus (80).

FIG. 1.

Specificity of CTD phosphorylation by TAK/P-TEFb. (A) Detection of TAK activity with CTD3 and RNA pol II substrates. The indicated GST-Tat or GST-Tat mutant fusion proteins (lanes 1 to 4, 7, and 8) were used to isolate TAK from cytoplasmic fractions of 293 cells by the GST pull-down procedure. For comparison, IP-kinase assays were conducted with immunoprecipitates prepared with anti-CDK9 or control antibodies (lanes 5 and 6, respectively). Kinase reaction mixtures contained 13.5 μg of CTD3 (lanes 1 to 6) or 20 ng of purified Drosophila RNA pol II (lanes 7 and 8) as the substrate. (B) CTD3 phosphorylation by TAK eluted from immunoprecipitated CDK9 complexes. The immunoprecipitates were washed extensively, and complexes were eluted for 18 h with the indicated amounts of CDK9 C-terminal peptide. The eluate was subjected to TAK assay, and the supernatant was examined by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. The control was the standard TAK assay with 293 cell S100 and GST-Tat48Δ. (C) Detection of CDK9 in the eluates after binding to GST-Tat48Δ beads. The proteins bound to the beads in panel B were examined by Western blotting with anti-CDK9 antibody.

We showed recently that CDK9 (PITALRE) binds to GST-Tat48Δ and is the only CTD kinase present in TAK (74, 80). TAK activity can be depleted from cell extracts by treatment with immobilized anti-CDK9 antibody (74, 80) or GST-Tat48Δ. CTD3 is also specifically phosphorylated by CDK9 complexes isolated by immunoprecipitation from HeLa cell nuclear extract (80) or 293 cell cytoplasmic extract (Fig. 1A, lanes 5 and 6). To determine whether these complexes contain all of the components necessary for association with Tat, the immune complexes were eluted with CDK9 C-terminal peptide and assayed for TAK activity. Increasing concentrations of the antigenic peptide released corresponding levels of TAK activity, measured by phosphorylation of CTD3 (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 to 4), and CDK9 protein, revealed by Western blotting of the proteins bound to the GST-Tat48Δ beads (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 to 4). Thus, the immunoprecipitated CDK9-containing complexes possess the ability to bind the Tat activation domain and phosphorylate the CTD heptad.

Species specificity of the interaction between Tat and CDK9/cyclin T-containing complexes.

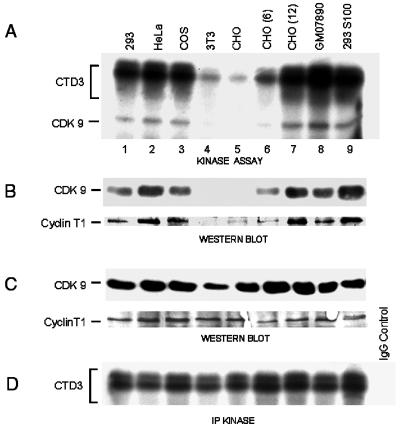

TAK activity is found in human HeLa and 293 cell extracts (36, 80) and Jurkat lymphocyte extracts (our unpublished data) as well as in monkey (COS) cell extracts (36). Since neither hamster nor mouse cells support efficient Tat transactivation (58), we examined CHO and 3T3 cell extracts for TAK activity. Figure 2A shows that extracts prepared from 3T3 and CHO cells (lanes 4 and 5) gave rise to greatly reduced levels of CTD3 phosphorylation compared to 293, HeLa, and COS cell extracts (lanes 1 to 3). Kinase assays demonstrated that the diminished TAK activity of the rodent cell extracts correlated with very poor phosphorylation of CDK9 bound to the GST-Tat48Δ beads (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 5) despite the presence of comparable levels of CDK9 in the extracts, as shown by Western blotting (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 to 5). Mixing experiments, in which increasing amounts of CHO cell extracts were added to 293 cell extracts, ruled out the possibility that the CHO extracts contain an inhibitor of TAK activity (data not shown). Furthermore, CDK9 immunoprecipitated from rodent cell extract phosphorylated CTD3 with an efficiency similar to that of human CDK9 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2D), demonstrating that rodent cells have active CDK9 complexes. Thus, the species specificity must be conferred by another component of these complexes.

FIG. 2.

TAK in CHO-human hybrid cell extracts. (A) CTD3 phosphorylation by TAK pulled down from different cell extracts: human (293, HeLa, and GM07890), monkey (COS), rodent (3T3 and CHO), and the rodent-human hybrids CHO(6) and CHO(12). (B) Western blotting of proteins bound to GST-Tat48Δ beads from the indicated cell extracts by using anti-CDK9 and anti-cyclin T1 antibodies. (C) Western blot analysis of proteins in unfractionated cell extracts with the same antibodies as in panel B. (D) IP-kinase assays conducted with the same cell extracts with CTD3 as the substrate.

Human chromosome 12, and to a lesser extent human chromosome 6, can complement the defect in CHO and mouse cells that precludes efficient Tat transactivation in these cells (58). To determine whether these human chromosomes also restore TAK activity to CHO cell extracts, we assayed cell extracts from the CHO-human cell hybrids CHO(12) and CHO(6), which contain human chromosomes 12 and 6, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2A (lane 7), CTD3 phosphorylation by TAK from CHO(12) cell extract was comparable to TAK activity in human and simian cell extracts (293, HeLa, GM07890, and COS). Correspondingly, the level of CDK9 phosphorylation was dramatically increased in CHO(12) extracts compared to CHO extracts (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 7). Thus, CHO(12) cells contain CDK9 complexes that can bind to Tat.

Since human cyclin T1 resides on chromosome 12 and complements rodent cells for Tat transactivation (73), we next probed GST-Tat-bound complexes for CDK9 and cyclin T1 by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). High levels of both proteins were present in such complexes isolated from CHO(12) cell extract, as from the human and simian cell extracts, but these proteins were detected weakly if at all in GST-Tat complexes from extracts of CHO cells (Fig. 2B). Comparable levels of both proteins were detected in all cell extracts tested (Fig. 2C), indicating that the antibodies recognize the rodent as well as human and simian proteins. Thus, the binding of CDK9 and cyclin T1 to the Tat activation domain correlates with TAK activity and requires a factor(s) encoded on human chromosome 12. These data show that TAK complexes contain cyclin T1 as well as CDK9; furthermore, human cyclin T1 can form an active chimeric complex with Chinese hamster CDK9 that binds efficiently to the Tat activation domain.

In CHO(6) cell extract the level of TAK activity was about threefold higher than that in CHO cell extract but was still considerably less than that observed in CHO(12) cell extract (Fig. 2A), consistent with the Tat transactivation levels observed in these cells (58). Western blotting showed that the binding of CHO CDK9 to the Tat activation domain increased in CHO(6) cell extract relative to CHO cell extract (Fig. 2B), in correspondence with the CTD3 phosphorylation activity, but the level of bound cyclin T1 was similar to that observed with the control CHO cell extract. One possible explanation is that human chromosome 6 supplies cyclin T2 but human cyclin T2-containing complexes fail to bind to GST-Tat beads in our assays (data not shown). Furthermore, we have been unable to detect cyclin T2 in CHO(6) extracts by using antibody to human cyclin T2. Thus, the partial complementation of Tat transactivation in CHO cells by human chromosome 6 could be attributable to an unidentified accessory factor, e.g., one that stabilizes Tat-TAK interactions.

CDK9 exclusively phosphorylates serine residues in CTD3 but is phosphorylated on both serine and threonine.

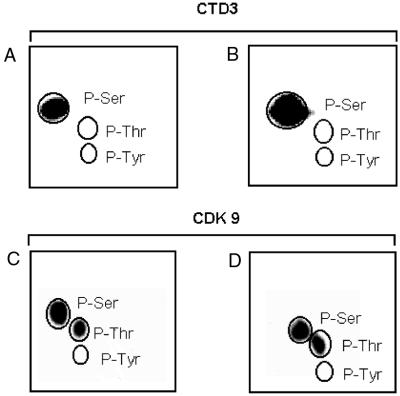

The CTD of RNA pol II is phosphorylated by various CTD kinases on serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues (12, 13). We used CTD3 as a model substrate to identify the CTD residues that are phosphorylated by TAK complexes. CTD3 gives rise to two phosphorylated bands when separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate gels (see, for example, Fig. 1B). Two-dimensional phosphoamino acid analysis of the upper and lower phosphorylated bands revealed phosphorylation of serine residues only (Fig. 3A and B, respectively). Identification of the specific serine residue that is targeted is described below. Contrary to an earlier report (14), CDK9 itself is phosphorylated on both serine and threonine residues when bound to Tat (Fig. 3D) or anti-CDK9 antibody (Fig. 3C). The same result was obtained with chromatographically purified CDK9 (Reactive Blue column fraction; data not shown). Phosphotyrosine was not detected. These findings agree with the conclusion that CDK9 (PITALRE) is a Ser/Thr proline-directed kinase (25), since in the heptad serines but not threonines are followed by prolines (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the detection of phosphorylated threonine in CDK9 is consistent with the prediction, based on its sequence (29), that the kinase contains a typical T loop in which Thr 186 is a potential phosphorylation site.

FIG. 3.

Phosphoamino acid analysis of CTD3 peptide and CDK9. CTD3, phosphorylated in TAK assays, resolved into two bands upon gel electrophoresis. The upper band (A) and lower band (B) were analyzed separately. Positions of phosphoamino acid markers are circled. CDK9 was phosphorylated in IP-kinase assays (C) or TAK assays (D) and examined in the same way.

FIG. 4.

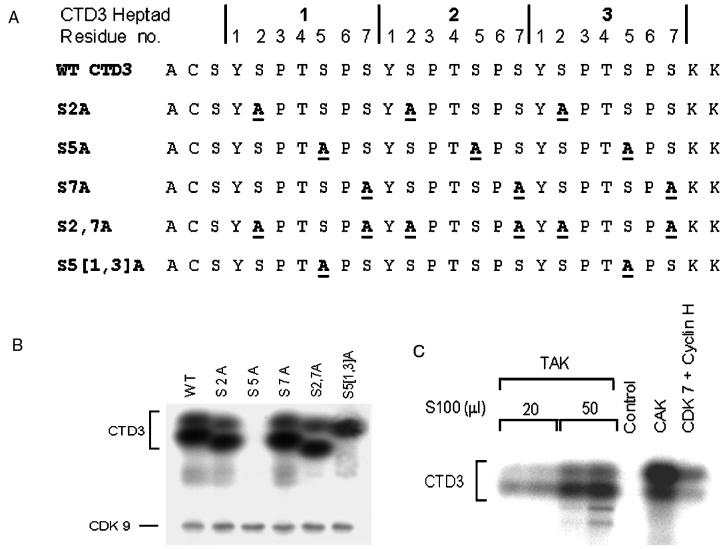

Selectivity of CTD3 phosphorylation by CDK9 and CDK7. (A) Sequence of wild-type (WT) CTD3 and mutant peptides. Substitutions are denoted by the underlined boldface letters. (B) Phosphorylation of the indicated CTD3 peptides in TAK assays. (C) Comparison of CTD3 phosphorylation by CDK9 and CDK7 complexes. CDK9 was monitored in TAK assays conducted with various amounts of 293 cell S100 (15 μg/ml). CDK7 was monitored by using Sf9 cell extracts (∼60 μg) containing either recombinant CAK or recombinant CDK7 and cyclin H. The control was the kinase assay with mock-infected Sf9 cell extract.

Serine 5 in the CTD heptad is essential for phosphorylation by TAK.

The CTD heptad contains three serine residues (Fig. 4A), and human CTD kinases specific for serine 5, serines 2 and 7, or serines 2 and 5 have been characterized (27, 65, 77). To identify the serine residue(s) that is phosphorylated by CDK9, we generated a series of CTD3 mutant peptides in which serines were replaced by alanines (Fig. 4A). In peptides S2A, S5A, and S7A, all three serines at positions 2, 5, and 7, respectively, were changed to alanines. Comparison with wild-type CTD3 shows that serine 5 is essential for heptad phosphorylation by TAK and that the serines at positions 2 and 7 are dispensable (Fig. 4B). Next, we replaced all six serines at positions 2 and 7 in the three heptad repeats; this peptide, S2,7A, was also efficiently phosphorylated by TAK (Fig. 4A and B), implying that serine 5 is the only serine in the heptad that is recognized by TAK.

To confirm this deduction, we synthesized a peptide that contains only one serine 5. Peptide S5[1,3]A retains all six serines at positions 2 and 7 as well as the central serine 5 residue, while both serine 5 residues in the flanking heptads are changed to alanine (Fig. 4A). Figure 4B shows that TAK phosphorylated S5[1,3]A and gave rise to a single band, as expected if serine 5 is the only target for phosphorylation by Tat-bound CDK9/cyclin T.

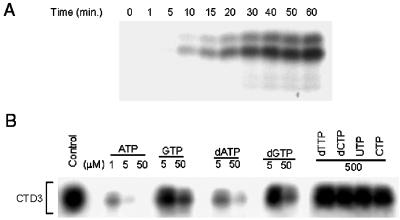

Phosphoamino acid analysis of the phosphorylated mutant peptides confirmed that phosphorylation was directed exclusively to serine residues (data not shown), as in wild-type CTD3 (Fig. 3). For further comparison, we examined the kinetics of CTD3 phosphorylation by TAK. Figure 5A shows a typical 60-min time course of CTD3 phosphorylation. Phosphorylation increased continuously with time up to at least 120 min (not shown). Longer exposures showed that CTD3 was detectably phosphorylated by 1 min, consistent with earlier assays using GST-CTD as a substrate and TAK isolated from nuclear extracts by binding to GST-Tat 2 (35). The same phosphorylation kinetics were obtained with the mutant peptides S2A and S7A (not shown). Thus, we conclude that serine 5 is the target for TAK phosphorylation and that serines 2 and 7 are not important for CTD3 phosphorylation. Despite slight mobility differences among the mutant phosphopeptides, probably due to the serine-to-alanine substitutions, the pattern of phosphorylation was little affected by mutation of all of the serine residues at positions 2 and 7 (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 5.

Kinetics of TAK activity and nucleotide usage by TAK. (A) Time course of CTD3 phosphorylation by TAK from 293 cell S100. Reactions were stopped at the indicated time points. (B) Kinase reaction mixtures containing [γ-32P]ATP were supplemented with the indicated unlabeled nucleotides at the concentrations shown. Control, no unlabeled nucleotides added.

The phosphorylated CTD3 peptides migrate as two bands, the faster of which incorporates two to three times as much radioactive phosphate as the slower band. We used CTD3 as a model substrate to compare TAK with another CTD kinase. CDK9 and CDK7 are both catalytic subunits of CTD kinases that function in transcription, but they play different roles. While CDK9 complexes participate in transcription elongation, CDK7 is a component of CAK and of TFIIH, an initiation factor that is also implicated in promoter clearance (18). CAK was shown to phosphorylate exclusively serine 5 in the CTD heptad (71). Both recombinant CAK (CDK7/cyclin H/MAT-1) and CDK7/cyclin H phosphorylate CTD3, giving rise predominantly to the slower band, whereas TAK predominantly yields the faster band (Fig. 4C). This indicates that the enzymes differ in their target within an array of CTD repeats. One possible interpretation of these data is that CAK prefers to phosphorylate CTD3 at a single site, whereas TAK yields multiply phosphorylated forms of the substrate, consistent with observations that purified TFIIH preferentially hypophosphorylates the full-length CTD while purified P-TEFb prefers to hyperphosphorylate a partially phosphorylated target (52, 64). An alternative interpretation is that TFIIH preferentially phosphorylates CTD3 at one of the serine 5 sites, whereas TAK selectively phosphorylates another serine 5 residue(s) in the substrate. In accordance with this view is the finding that the two serine 5 residues of a CTD diheptad are unequally phosphorylated by TFIIH (71). Although further work is needed to define the phosphorylation specificities of CDK9 and CDK7 in detail, it is clear that their different functions are reflected in different phosphorylation site preferences.

Nucleotide usage by Tat-associated CDK9/cyclin T complex.

Most protein kinases utilize only ATP as a phosphate donor (40). This was shown to be true for purified Drosophila P-TEFb, which contains the CDK9/cyclin T complex (52). For comparison, we tested the nucleotide utilization by human CDK9/cyclin T complexes in competition experiments by adding an excess of unlabeled nucleotides over [γ-32P]ATP and monitoring CTD3 phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 5B, the efficiency of ATP utilization in the TAK assay was at least fivefold higher than that of dATP and at least 50-fold higher than that of GTP and dGTP. The pyrimidine nucleotides CTP, dCTP, UTP, and dTTP were not utilized at 500 μM (Fig. 5B) or even at concentrations of as high as 1 mM (data not shown). These data are very similar to results obtained with purified Drosophila P-TEFb (52), indicating that this elongation factor and Tat-bound human CDK9 complexes have the same phosphate donor specificity. GTP alone (without ATP) can be used as the phosphate donor for both Thr and Ser phosphorylation in CDK9 and for Ser phosphorylation in CTD3 (data not shown). The phosphorylation efficiency with labeled GTP is about 50-fold less than that with labeled ATP, confirming the results obtained in the competition experiments.

Requirement for Mg ions for Tat-TAK interaction.

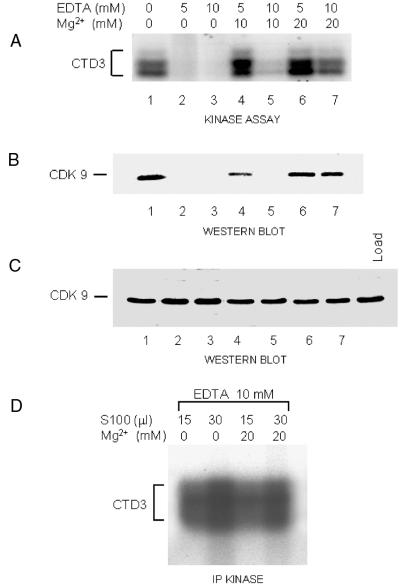

Initially, TAK activity was found in the nuclear fraction, but not the cytoplasmic fraction, of HeLa cells (36). However, we detected high levels of cytoplasmic TAK activity when 293, HeLa, or Jurkat cells were fractionated by the same method (16) except for omission of the last dialysis step. This dialysis was against a buffer lacking Mg2+. We observed that TAK activity was lost when extracts were dialyzed against this magnesium-free buffer (data not shown). To determine whether the presence of magnesium ions is responsible for the differences observed, EDTA was added to the cytoplasmic extract at two concentrations to chelate Mg2+ ions. As shown in Fig. 6A (lanes 2 and 3), this resulted in the loss of TAK activity, and the inhibitory effect of EDTA was reversed by adding back excess MgCl2 (lanes 4 to 7). When the proteins bound to the beads were analyzed by Western blotting and probing with antibody against CDK9, CTD3 phosphorylation correlated perfectly with the binding of CDK9 to the beads (Fig. 6B). Similarly, TAK binding and activity could be restored by adding low concentrations of Zn2+ (up to 2 mM) (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that prolonged incubation in the presence of EDTA caused CDK9 degradation, the cytoplasmic extract was tested for CDK9 after the binding reaction. Western blotting showed that CDK9 was not degraded in the presence of EDTA (Fig. 6C), indicating that CDK9-containing complexes are unable to bind to GST-Tat48Δ in the absence of Mg2+. Two possibilities were considered: divalent cations are necessary for the stability of CDK9/cyclin T complexes or for the binding of such complexes to GST-Tat48Δ. To distinguish between these possibilities, we used anti-CDK9 antibody to immunoprecipitate CDK9/cyclin T-containing complexes from the same extracts. The phosphorylation of CTD3 by the immunoprecipitates was unaffected by the removal of Mg ions (Fig. 6D), indicating that the CDK9/cyclin T complexes are not disrupted by EDTA and suggesting that the binding of TAK to the Tat activation domain is dependent on the presence of divalent cations.

FIG. 6.

Effects of Mg and EDTA on TAK activity. (A) 293 cell S100 fractions were treated with EDTA and MgCl2 at the final concentrations indicated and then subjected to TAK assay. After the kinase assay, the supernatant was examined for CTD3 phosphorylation. (B) Western blot analysis with anti-CDK9 antibody of the proteins bound to GST-Tat48Δ beads in the same experiment as for panel A. (C) Western blot analysis with anti-CDK9 antibody of proteins remaining in the supernatant after binding to GST-Tat48Δ beads in the same experiment as for panels A and B. Load, sample of 293 cell S100. (D) IP-kinase assays conducted with 293 cell S100 (15 mg/ml) subjected to treatment with EDTA and Mg2+ as indicated.

CDK9/cyclin T is present in large complexes.

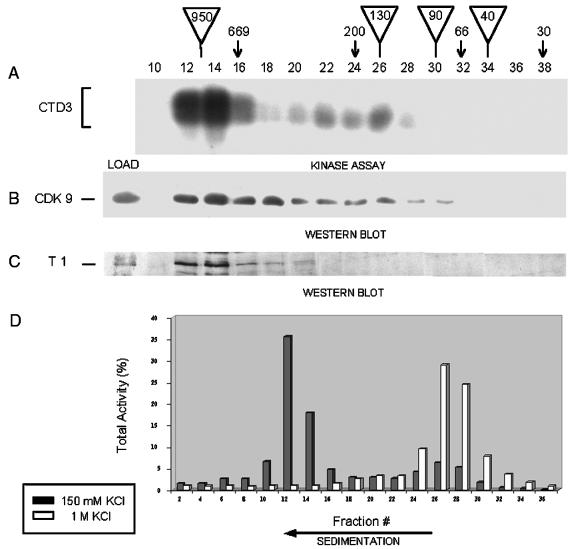

By gel filtration chromatography, Gariga et al. (24) found that CDK9 is present in 293 cell extracts as two multisubunit complexes of 670 and 158 kDa. In keeping with this finding, multiple polypeptides were detected when CDK9 complexes were immunoprecipitated from cell extracts (24, 29, 78, 80). On the other hand, the molecular mass of partially purified TAK has been reported to be ∼110 kDa (75). Since TAK is present in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, we considered the possibility that different TAK-containing complexes exist in these subcellular fractions. We employed both gel filtration chromatography and glycerol gradient sedimentation to examine TAK-containing complexes and estimate their molecular weights. To minimize possible disruption of the complexes, 293 cells were lysed by the method of Dignam et al. (15), which results in a transcriptionally active nuclear extract.

When cytoplasmic extracts of 293 cells were fractionated in a Sephacryl S300 column equilibrated with isotonic buffer, TAK activity was detected predominantly in a large complex with an estimated molecular mass of ∼950 kDa. In the experiment with the results shown in Fig. 7A, this large complex represented 70% of the total TAK activity; 14% of the total TAK activity was present in a second peak with a molecular mass of ∼130 kDa. Similar results were obtained with nuclear extracts of 293 cells (data not shown). As expected, TAK activity coeluted with CDK9 and cyclin T1 (Fig. 7B and C), and CDK9 was detected bound to GST-Tat48Δ beads (by Western blotting) only in fractions with TAK activity (data not shown). The majority of CDK9 was detected in the fractions containing the large complex, with an additional minor peak in the fractions containing the small complex (Fig. 7B). Cyclin T1 was detected in association with the high-molecular-weight complex (Fig. 7C). Its apparent absence from the small complex is probably due to the weakness of the anti-cyclin T1 antibody combined with the smaller amount of this complex.

FIG. 7.

Separation of TAK complexes by gel filtration and sedimentation. (A) CTD3 phosphorylation by TAK pulled down from fractions after resolution of 293 cell S100 in a gel filtration column. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated by arrows. Triangles show the estimated molecular masses of the large complex (950 kDa), CDK9/cyclin T complex (130 kDa), cyclin T (90 kDa), and CDK9 (40 kDa). (B and C) The same fractions were examined by Western blotting with antibodies to CDK9 (B) and cyclin T1 (C). Load, sample of the 293 cell S100 loaded on the column. (D) Cytoplasmic extracts from 293 cells in 150 mM KCl or adjusted to 1 M KCl were fractionated in glycerol gradients. Fractions were subjected to TAK assays, and the phosphorylated CTD3 bands were quantified, normalized, and plotted.

Since the larger complex eluted near the excluded volume of the column, we considered the possibility that the peak of TAK activity contains more than one complex. However, the same two complexes were detected when either nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented through glycerol gradients (Fig. 7D). Treatment of the cytoplasmic extract with 0.8 to 1 M KCl prior to fractionation caused all of the TAK activity to shift to the position of the low-molecular-weight complex (Fig. 7D). This result is consistent with our finding that chromatographically purified TAK (Reactive Blue column fractions) contained only the smaller peak (not shown) and with observations of Yang et al. (75). Treatment with an intermediate concentration of salt prior to fractionation revealed both complexes in approximately the same abundance (not shown).

These results indicate that TAK activity is present in the cell chiefly in a high-molecular-mass complex (∼950 kDa) which can dissociate into a smaller complex (∼130 kDa) apparently consisting of CDK9 and its regulatory subunit cyclin T1. This core complex retains Tat binding and CTD phosphorylation activities. Consistent with the coimmunoprecipitation data of Peng et al. (67), neither CDK9 or cyclin T1 was detected in fractions corresponding to molecular masses of 42 and 87 kDa, implying that they are largely if not exclusively present in complexes.

DISCUSSION

TAK and P-TEFb.

TAK and P-TEFb have a common CTD kinase activity conferred by CDK9 (74, 80). We show here that TAK, like P-TEFb (67), contains CDK9’s cyclin partner, cyclin T1. However it is not clear whether P-TEFb and TAK consist solely of the CDK9/cyclin T heterodimer and whether they are identical in composition and properties. Price and colleagues showed that CDK9-depleted HeLa nuclear extracts have diminished in vitro transcription activity that can be complemented by the addition of purified Drosophila P-TEFb or recombinant human CDK9/cyclin T (67, 80). This complementation suggests that the core complex, CDK9/cyclin T, is sufficient to restore in vitro transcription elongation, although a requirement for additional components that are not efficiently depleted cannot be excluded. In this connection, it is noteworthy that, to date, Tat transactivation has been obtained only with preparations containing several additional polypeptides (49, 78).

Multiple proteins coimmunoprecipitate with CDK9 from nuclear or whole-cell extracts (24, 29, 78, 80). Polypeptides with the mobility of cyclin T are commonly seen, but it is not clear whether the other components of the immunoprecipitates are identical. While they remain to be identified, some of them are probably substrates of CDK9, since their phosphorylation is highly sensitive to DRB (80). Our fractionation experiments suggest that most of the TAK activity in both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts is present in very-high-molecular-mass complexes (∼950 kDa). Similar large complexes were detected by gel filtration and sedimentation analysis, but it remains possible that there is more than one such complex. These complexes, which also contain most of the CDK9 and cyclin T1 in these extracts, can be dissociated by treatment with high salt concentrations to give the core complex CDK9/cyclin T1. Minor complexes of intermediate size are also detected. Conceivably, these different CDK9-containing complexes participate in the regulation of transcription elongation by cellular effectors; alternatively, CDK9/cyclin T may engage in distinct cellular functions executed through phosphorylation of other substrates. By analogy, CDK7/cyclin H is a component of TFIIH as well as of structurally and functionally distinct CAK subassemblies (32, 76).

TAK-Tat interactions.

Both TAK and P-TEFb were initially identified in nuclear extracts (36, 54), while our fractionation experiments detected TAK in cytoplasmic extracts as well as nuclear extracts. The localization of at least a portion of TAK/P-TEFb in the cytoplasm is supported by the properties of transdominant Tat mutations. Such mutant Tat proteins interact with TAK (19) and inhibit wild-type Tat function in a dominant negative fashion. This phenotype is conferred by mutations in the Tat basic region, which also contains the nuclear localization signal (56). A Tat protein carrying a deletion in the basic region localized exclusively to the cytoplasm and was a dominant negative inhibitor. Inclusion of additional mutations in the activation domain eliminated this transdominant activity (63). Taken together with the observation that TAK binding requires an intact Tat activation domain, these findings imply that TAK is squelched in the cytoplasm by the transdominant Tat proteins. Interestingly, Tat interacts with another nuclear and/or cytoplasmic factor(s) which renders Tat capable of transactivating the HIV LTR in vitro without a lag period (30). Thus, as suggested previously (6, 63), it is likely that Tat is assembled with CDK9/cyclin T and perhaps other transcription regulators in the cytoplasm before entering the nucleus.

The binding of Tat to TAK requires divalent cations. Previously published studies had demonstrated the effect of metal ions on Tat structure (22, 69) and the Tat-TAR interaction (39). Similarly, the functional dependence of the Tat-TAK interaction on Mg or Zn ions could be due to stabilization of a Tat conformation necessary for TAK binding, but it is also possible that metal ions take a direct part in stabilizing Tat-TAK interactions.

TAK, CAK, and CTD phosphorylation.

The CTD kinases are a functionally heterogeneous group, including enzymes that phosphorylate serines 5, 2 and 5, or 2 and 7 in the CTD heptad, as well as factors participating in varied cellular functions and subjected to a spectrum of controls. Together with some other serine 5-specific CTD kinases, such as TFIIH and the mitogen-activated protein kinases, CDK9 belongs to the proline-directed protein kinase family (25, 71). Even though TFIIH and mitogen-activated protein kinases show the same detailed specificity for the CTD motif [PX(S/T)P], their recognition sites are not identical (71). Such differences in site recognition may be the characteristic that confers functional distinctions among these CTD kinases.

P-TEFb and TFIIH are both general transcription factors that can phosphorylate the CTD and have been ascribed a function in Tat transactivation. Depletion experiments indicate that they are not present in the same complex (49, 67, 74), and they are catalytically independent (66). Nevertheless, several investigators have reported structural and functional interactions between Tat and TFIIH or CAK (9, 23, 64). Contrary to these findings, but in agreement with data from other laboratories (34, 49, 67, 74), in our assays neither the constituent polypeptides of CAK nor the p62 subunit of TFIIH was pulled down by beads containing GST-Tat fusion proteins. Moreover, TAK was unable to phosphorylate a CAK substrate, CDK2, and was not depleted by antibody to CDK7 (data not shown). Therefore, if there is an interaction between Tat and TFIIH or between TFIIH and P-TEFb, it is too weak or unstable to be detectable under our experimental conditions.

Species specificity and the mechanism of Tat transactivation.

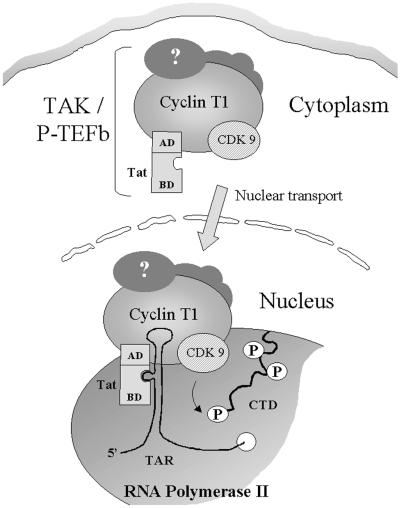

A widely cited model of Tat transactivation views the process in terms of the recruitment of P-TEFb to the elongating transcription complex by TAR-associated Tat. This model is consistent with many studies, but the findings presented here are more compatible with an alternative mode of action. We suggest that Tat first binds to TAK/P-TEFb via cyclin T1; the resultant Tat-TAK/P-TEFb complex then associates with the pol II complex, and this elongation-competent pol II assembly is stabilized, and possibly activated, by binding to both the loop and bulge structures of TAR.

This model, depicted in Fig. 8, retains essential features of earlier models in that it ascribes central importance to the interactions of Tat with TAR and with TAK/P-TEFb, and it also accommodates a number of additional observations. First, cyclin T1 encoded by human chromosome 12 is required for elevated TAK activity (Fig. 2) and HIV-1 expression in human-rodent hybrid cells (33). In CHO cells, Tat transactivates weakly, and this effect requires the TAR bulge but is unaffected by TAR loop mutations (2). In vitro, cyclin T1 binds to the activation domain of Tat and stabilizes Tat-TAR interactions in gel mobility shift assays (73). This interaction is also dependent on the TAR loop. Therefore, interactions with both Tat and TAR are required for the human cyclin T1 to mediate maximal Tat transactivation. Second, P-TEFb binds TAR in the absence of Tat via an 87-kDa protein which is possibly cyclin T1: this interaction was reduced by a loop mutation (78). Tat and human P-TEFb interact with one another in the absence of TAR (74, 80), and these two proteins synergize to bind TAR (78). Chimeric P-TEFb, containing human cyclin T1 complexed with rodent proteins, also binds Tat (Fig. 2). Thus, the Tat–P-TEFb–TAR complex is stabilized by multiple pairwise interactions between its components: TAR bulge with Tat, TAR loop with cyclin T1, and Tat with TAK/P-TEFb (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Schematic representation of Tat delivery to its nuclear transactivation site. The model depicts TAK assembly in the cytoplasm. P-TEFb, composed of CDK9, cyclin T1, and other components, interacts with the activation domain (AD) of Tat. In the nucleus, the TAK complex (P-TEFb–Tat) interacts with the transcription complex via cyclin T1 and the basic domain (BD) of Tat, both of which bind to TAR. Through phosphorylation of the pol II CTD, the elongating complex becomes more processive and Tat transactivation is achieved. (See text for details.)

Disruption of this complex by weakening any of these interactions can result in a decrease or abrogation of Tat transactivation. It is well established that the binding of Tat to TAR, via the Tat basic region and the TAR bulge, is critical for high levels of transactivation. Our data demonstrate that the strength of the interaction between the Tat activation domain and TAK/P-TEFb is greatly attenuated in CHO cells as a result of differences between human and CHO cyclin T. Previous work implied that the interaction of TAR with a cellular factor (now identified as TAK/P-TEFb and probably mediated by cyclin T1 and the TAR loop) is also weak in CHO cells (2). Only when all of these interactions occur does Tat transactivation take place optimally. In support of this view, when Tat was supplied as a fusion protein with the R17 coat protein and TAR was replaced by the coat protein binding site, the level of transactivation in CHO and CHO(12) cells was relatively low, and the presence of human cyclin T1 conferred no advantage. Indeed, the level of transactivation was similar to that elicited by Tat in CHO cells from the wild-type HIV promoter (3).

Finally, our data and that of others show that TAR is not needed for the binding of TAK/P-TEFb to Tat, suggesting that this interaction may precede the Tat-TAR binding. Consistent with this order of interactions, Tat mutants that are unable to bind TAR can act as dominant negative inhibitors. Moreover, such inhibition can occur even when the Tat mutants are restricted to the cytoplasm (where TAK/P-TEFb can also be found). Since the general elongation factor P-TEFb has been shown to interact with elongating pol II complexes in Drosophila nuclear extracts (53), it is likely that Tat is delivered to the vicinity of the elongation complex by P-TEFb and that this complex then docks with TAR. Hence, the species specificity conferred upon P-TEFb/TAK by human cyclin T1 is twofold: it facilitates high-affinity interaction with the Tat activation domain and with the loop structure of TAR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David H. Price for reagents and helpful discussion and Kathy A. Jones and David O. Morgan for reagents. We also thank Robert J. Donnelly of the New Jersey Medical School Molecular Resource Facility for CTD3 peptide synthesis and Adam P. Forman for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant AI 31802.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akoulitchev S, Makela T P, Weinberg R A, Reinberg D. Requirement for TFIIH kinase activity in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature (London) 1995;377:557–560. doi: 10.1038/377557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso A, Cujec T P, Peterlin B M. Effects of human chromosome 12 on interactions between Tat and TAR of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:6505–6513. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6505-6513.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, Derse D, Peterlin B M. Human chromosome 12 is required for optimal interactions between Tat and TAR of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in rodent cells. J Virol. 1992;66:4617–4621. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4617-4621.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braddock M, Thorburn A M, Kingsman A J, Kingsman S M. Blocking of Tat-dependent HIV-1 RNA modification by an inhibitor of RNA polymerase II processivity. Nature (London) 1991;350:439–441. doi: 10.1038/350439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll R, Peterlin B M, Derse D. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat activity by coexpression of heterologous trans activators. J Virol. 1992;66:2000–2007. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2000-2007.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun R F, Jeang K-T. Requirements for RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain for activated transcription of human retroviruses human T-cell lymphotropic virus I and HIV-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27888–27894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cujec T P, Cho H, Maldonado E, Meyer J, Reinberg D, Peterlin B M. The human immunodeficiency virus transactivator Tat interacts with the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1817–1823. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cujec T P, Okamoto H, Fujinaga K, Meyer J, Chamberlin H, Morgan D O, Peterlin B M. The HIV transactivator TAT binds to the CDK-activating kinase and activates the phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2645–2657. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahmus M E. Phosphorylation of mammalian RNA polymerase II. Methods Enzymol. 1996;273:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)73019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahmus M E. Reversible phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19009–19012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahmus M E. The role of multisite phosphorylation in the regulation of RNA polymerase II activity. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1994;48:143–179. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahmus M E, Shilatifard A, Conaway J W, Conaway R C. Phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1261:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)00233-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Luca A, Esposito V, Baldi A, Claudio P P, Fu Y, Caputi M, Pisano M M, Baldi F, Giordano A. CDC2-related kinase PITALRE phosphorylates pRb exclusively on serine and is widely expressed in human tissues. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172:265–273. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199708)172:2<265::AID-JCP13>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dignam J D, Martin P L, Shastry B S, Roeder R G. Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:582–598. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dingwall C, Ernberg I, Gait M J, Green S M, Hearphy S, Karn J, Lowe A D, Singh M, Skinner M A, Valerio R. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 tat protein binds trans-activation-responsive region (TAR) RNA in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6925–6929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dvir A, Tan S, Conaway J W, Conaway R C. Promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. Formation of an escape-competent transcriptional intermediate is a prerequisite for exit of polymerase from the promoter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28175–28178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Echetebu C O, Rhim H, Herrmann C H, Rice A P. Construction and characterization of a potent HIV-2 Tat transdominant mutant protein. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:655–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher R P, Jin P, Chamberlin H M, Morgan D O. Alternative mechanisms of CAK assembly require an assembly factor or an activating kinase. Cell. 1995;83:47–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher R P, Morgan D O. A novel cyclin associates with MO15/CDK7 to form the CDK-activating kinase. Cell. 1994;78:713–724. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankel A D, Bredt D S, Pabo C O. Tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus forms a metal-linked dimer. Science. 1988;240:70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2832944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Martínez L F, Mavankal G, Neveu J M, Lane W S, Ivanov D, Gaynor R B. Purification of a Tat-associated kinase reveals a TFIIH complex that modulates HIV-1 transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:2836–2850. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garriga J, Mayol X, Graña X. The CDC2-related kinase PITALRE is the catalytic subunit of active multimeric protein complexes. Biochem J. 1996;319:293–298. doi: 10.1042/bj3190293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garriga J, Segura E, Mayol X, Grubmeyer C, Graña X. Phosphorylation site specificity of the CDC2-related kinase PITALRE. Biochem J. 1996;320:983–989. doi: 10.1042/bj3200983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaynor R B. Regulation of HIV-1 gene expression by the transactivator protein Tat. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;193:51–77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78929-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebara M M, Sayre M H, Corden J L. Phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal repeat domain in RNA polymerase II by cyclin-dependent kinases is sufficient to inhibit transcription. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:390–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graeble M A, Churcher M J, Lowe A D, Gait M J, Karn J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transactivator protein, tat, stimulates transcriptional read-through of distal terminator sequences in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6184–6188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graña X, DeLuca A, Sang N, Fu Y, Claudio P P, Rosenblatt J, Morgan D O, Giordano A. PITALRE, a nuclear CDC2-related protein kinase that phosphorylates the retinoblastoma protein in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3834–3838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg M E, Ostapenko D A, Mathews M B. Potentiation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat by human cellular proteins. J Virol. 1997;71:7140–7144. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7140-7144.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harper J W, Elledge S J. The role of Cdk7 in CAK function, a retro-retrospective. Genes Dev. 1998;12:285–289. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart C E, Ou C Y, Galphin J C, Moore J, Bacheler L T, Wasmuth J J, Petteway S R, Jr, Schochetman G. Human chromosome 12 is required for elevated HIV-1 expression in human-hamster hybrid cells. Science. 1989;246:488–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2683071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrmann C H, Gold M O, Rice A P. Viral transactivators specifically target distinct cellular protein kinases that phosphorylate the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:501–508. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrmann C H, Rice A P. Lentivirus Tat proteins specifically associate with a cellular protein kinase, TAK, that hyperphosphorylates the carboxyl-terminal domain of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II: candidate for a Tat cofactor. J Virol. 1995;69:1612–1620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1612-1620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herrmann C H, Rice A P. Specific interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus Tat proteins with a cellular protein kinase. Virology. 1993;197:601–608. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirose Y, Manley J L. RNA polymerase II is an essential mRNA polyadenylation factor. Nature (London) 1998;395:93–96. doi: 10.1038/25786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hottiger M O, Nabel G J. Interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat with the transcriptional coactivators p300 and CREB binding protein. J Virol. 1998;72:8252–8256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8252-8256.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ippolito J A, Steitz T A. A 1.3-A resolution crystal structure of the HIV-1 trans-activation response region RNA stem reveals a metal ion-dependent bulge conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9819–9824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jakobi R, Traugh J A. Site-directed mutagenesis and structure/function studies of casein kinase II correlate stimulation of activity by the beta subunit with changes in conformation and ATP/GTP utilization. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:1111–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeang K T, Berkhout B, Dropulic B. Effects of integration and replication on transcription of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24940–24949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kao S Y, Calman A F, Luciw P A, Peterlin B M. Anti-termination of transcription within the long terminal repeat of HIV-1 by tat gene product. Nature (London) 1987;330:489–493. doi: 10.1038/330489a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashanchi F, Pira G, Radonovich M F, Duval J F, Fattaey A, Chian C M, Roeder R G, Brady J N. Direct interaction of human TFIID with the HIV-1 transactivator Tat. Nature (London) 1994;367:295–299. doi: 10.1038/367295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kato H, Sumimoto H, Pognonec P, Chen C-H, Rosen C A, Roeder R G. HIV-1 tat acts as a processivity factor in vitro in conjunction with cellular elongation factors. Genes Dev. 1992;6:655–666. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kessler M, Mathews M B. Premature termination and processing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-promoted transcripts. J Virol. 1992;66:4488–4496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4488-4496.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laspia M F, Rice A P, Mathews M B. HIV-1 Tat protein increases transcriptional initiation and stabilizes elongation. Cell. 1989;59:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laspia M F, Rice A P, Mathews M B. Synergy between HIV-1 Tat and adenovirus E1A is principally due to stabilization of transcriptional elongation. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2397–2408. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Makela T P, Parvin J D, Kim J, Huber L J, Sharp P A, Weinberg R A. A kinase-deficient transcription factor TFIIH is functional in basal and activated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5174–5178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mancebo H S, Lee G, Flygare J, Tomassini J, Luu P, Zhu Y, Peng J, Blau C, Hazuda D, Price D, Flores O. P-TEFb kinase is required for HIV Tat transcriptional activation in vivo and in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2633–2644. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marciniak R A, Calnan B J, Frankel A D, Sharp P A. HIV-1 Tat protein trans-activates transcription in vitro. Cell. 1990;63:791–802. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marciniak R A, Sharp P A. HIV-1 Tat protein promotes formation of more-processive elongation complexes. EMBO J. 1991;10:4189–4196. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marshall N F, Peng J, Xie Z, Price D H. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxl-terminal domain kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27176–27183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall N F, Price D H. Control of formation of two distinct classes of RNA polymerase II elongation complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2078–2090. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marshall N F, Price D H. Purification of P-TEFb, a transcription factor required for the transition into productive elongation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12335–12338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCracken S, Fong N, Yankulov K, Ballantyne S, Pan G, Greenblatt J, Patterson S D, Wickens M, Bentley D L. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature (London) 1997;385:357–361. doi: 10.1038/385357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Modesti N, Garcia J, Debouck C, Peterlin M, Gaynor R. Trans-dominant Tat mutants with alterations in the basic domain inhibit HIV-1 gene expression. New Biol. 1991;3:759–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mortillaro M J, Blencowe B J, Wei X, Nakayasu H, Du L, Warren S L, Sharp P A, Berezney R. A hyperphosphorylated form of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II is associated with splicing complexes and the nuclear matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8253–8257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newstein M, Stanbridge E J, Casey G, Shank P R. Human chromosome 12 encodes a species-specific factor which increases human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-mediated transactivation in rodent cells. J Virol. 1990;64:4565–4567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4565-4567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nonet M, Sweetser D, Young R A. Functional redundancy and structural polymorphism in the large subunit of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1987;50:909–915. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90517-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Brien T, Hardin S, Greenleaf A, Lis J T. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain and transcriptional elongation. Nature (London) 1994;370:75–77. doi: 10.1038/370075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okamoto H, Sheline C T, Corden J L, Jones K A, Peterlin B M. Trans-activation by human immunodeficiency virus Tat protein requires the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11575–11579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orsini M J, Debouck C M. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and type 2 Tat function by transdominant Tat protein localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm. J Virol. 1996;70:8055–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8055-8063.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parada C A, Roeder R G. Enhanced processivity of RNA polymerase II triggered by Tat-induced phosphorylation of its carboxy-terminal domain. Nature (London) 1996;384:375–378. doi: 10.1038/384375a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patturajan M, Schulte R J, Sefton B M, Berezney R, Vincent M, Bensaude O, Warren S L, Corden J L. Growth-related changes in phosphorylation of yeast RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4689–4694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peng J, Marshall N F, Price D H. Identification of a cyclin subunit required for the function of Drosophila P-TEFb. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13855–13860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peng J, Zhu Y, Milton J T, Price D H. Identification of multiple cyclin subunits of human P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 1998;12:755–762. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhim H, Echetebu C O, Herrmann C H, Rice A P. Wild-type and mutant HIV-1 and HIV-2 Tat proteins expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1116–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rice A P, Carlotti F. Structural analysis of wild-type and mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat proteins. J Virol. 1990;64:6018–6026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6018-6026.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Serizawa H, Conaway J W, Conaway R C. Phosphorylation of C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II is not required in basal transcription. Nature (London) 1993;363:371–374. doi: 10.1038/363371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trigon S, Serizawa H, Conaway J W, Conaway R C, Jackson S P, Morange M. Characterization of the residues phosphorylated in vitro by different C-terminal domain kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6769–6775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weeks K M, Ampe C, Schultz S, Steitz T, Crothers D M. Fragments of the HIV-1 Tat protein specifically bind TAR RNA. Science. 1990;249:1281–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.2205002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wei P, Garber M E, Fang S M, Fischer W H, Jones K A. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang X, Gold M O, Tang D N, Lewis D E, Aguilar-Cordova E, Rice A P, Herrmann C H. TAK, an HIV Tat-associated kinase, is a member of the cyclin-dependent family of protein kinases and is induced by activation of peripheral blood lymphocytes and differentiation of promonocytic cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12331–12336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang X, Herrmann C H, Rice A P. The human immunodeficiency virus Tat proteins specifically associate with TAK in vivo and require the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II for function. J Virol. 1996;70:4576–4584. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4576-4584.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yankulov K Y, Bentley D L. Regulation of CDK7 substrate specificity by MAT1 and TFIIH. EMBO J. 1997;16:1638–1646. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang J, Corden J L, Shilatifard A, Conaway J W, Conaway R C. Identification of phosphorylation sites in the repetitive carboxyl-terminal domain of the mouse RNA polymerase II largest subunit. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2290–2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou Q, Chen D, Pierstorff E, Luo K. Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb mediates Tat activation of HIV-1 transcription at multiple stages. EMBO J. 1998;17:3681–3691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou Q, Sharp P A. Tat-SF1: cofactor for stimulation of transcriptional elongation by HIV-1 Tat. Science. 1996;274:605–610. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu Y, Pe’ery T, Peng J, Ramanathan Y, Marshall N, Marshall T, Amendt B, Mathews M B, Price D H. Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is required for HIV-1 tat transactivation in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2622–2632. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]