Significance

We describe a recombinant human OC43 coronavirus (CoV) with the natural spike glycoprotein replaced with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike. This virus has been designated a biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) agent due to its high attenuation in cultured cells and animals. rOC43-CoV2 S is an improved proxy virus for measuring virus-neutralizing antibodies than the standard recombinant virus used for this purpose. It is also a live-attenuated COVID mucosal vaccine candidate that elicits vigorous serum and mucosal antibody response in mice and rhesus monkeys.

Keywords: coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, mucosal vaccine, virus-neutralizing antibodies, HCoV-OC43

Abstract

We generated a replication-competent OC43 human seasonal coronavirus (CoV) expressing the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike in place of the native spike (rOC43-CoV2 S). This virus is highly attenuated relative to OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 in cultured cells and animals and is classified as a biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) agent by the NIH biosafety committee. Neutralization of rOC43-CoV2 S and SARS-CoV-2 by S-specific monoclonal antibodies and human sera is highly correlated, unlike recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-CoV2 S. Single-dose immunization with rOC43-CoV2 S generates high levels of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and fully protects human ACE2 transgenic mice from SARS-CoV-2 lethal challenge, despite nondetectable replication in respiratory and nonrespiratory organs. rOC43-CoV2 S induces S-specific serum and airway mucosal immunoglobulin A and IgG responses in rhesus macaques. rOC43-CoV2 S has enormous value as a BSL-2 agent to measure S-specific antibodies in the context of a bona fide CoV and is a candidate live attenuated SARS-CoV-2 mucosal vaccine that preferentially replicates in the upper airway.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is now endemic in humans as the fifth endemic coronavirus. Despite nearly complete herd immunity due to infection and vaccination (1), SARS-CoV-2 remains a dangerous virus with a death rate far higher than influenza and other respiratory viruses. Given the continued rapid antigenic drift in the spike (S) receptor-fusion glycoprotein (2), it is likely that SARS-CoV-2 will remain a significant public health threat for years to come.

Spike is the primary viral target for protective antibodies (Abs). Measuring anti-S Ab responses in functional assays, including virus neutralization (VN) and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity assays, is critical to monitoring ongoing antigenic variation and gauging active and passive vaccine efficacy (3–7). SARS-CoV-2 remains a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) agent, greatly limiting its use in basic, translational, and clinical studies. Consequently, most studies of S function as a viral entry factor utilize S expressed by recombinant or pseudotyped non-CoVs (8–11). However, the geometric features of S distribution on CoV virions confer properties not duplicated using other viral vector systems, each of which has its technical quirks and limitations, including limited reproducibility due to the complexity of creating nonreplicating virus stocks.

To address this problem, we replaced the S gene of the human CoV OC43 with the SARS-CoV-2 S gene to develop a replication-competent recombinant coronavirus (rOC43-CoV2 S) that can be safely used at BSL-2. Due to its low human pathogenicity, OC43 is a BSL-2 agent (12, 13). OC43 S, unlike the ACE2-binding SARS-CoV-2 S, binds terminal 9-O-Ac-sialic acid residues which alters its tissue tropism. Here, we describe our generation of rOC43-CoV2 S GFP expressing reporter virus under BSL-3 containment, document experiments demonstrating its major attenuation relative to either parental virus justifying its designation a BSL-2 agent by the NIH Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) in consultation with the Office of Science Policy (OSP), demonstrate its utility as an improved proxy agent for SARS-CoV-2 in VN assays and show its potential as an attenuated mucosal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine using mouse and nonhuman primate models.

Results

Generating a Replication-Competent Reporter S Replacement OC43 Virus.

We first generated a recombinant OC43 encoding enhanced GFP reporter virus (rOC43-eGFP) using circular polymerase extension reaction (CPER) previously developed for large genome RNA viruses (14). We assembled full-length rOC43 cDNA from six viral DNA fragments and a linker fragment into a circular DNA in a single CPER using high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We inserted a sequence encoding eGFP followed by a Thosea asigna virus 2A (T2A) ribosomal skipping sequence at the 3′ end of the ORF1b gene. We transfected the CPER mix into HEK293-FT cells which we then cocultured with highly OC43 permissive rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells. We amplified recovered rOC43-eGFP viruses in RD cells to generate viral stocks (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). We found similar plaque sizes for human OC43 wild-type (hOC43-WT) and rOC43-eGFP virus in RD cells (Fig. 1B), consistent with near identical growth curves following low multiplicity of infection (MOI) (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Recovery of rOC43-eGFP and rOC43-CoV2 S. (A) Schematic of CoV genomes and strategy for insertion of SARS-CoV-2 S to rOC43-eGFP genome. The hOC43 genome comprises nine main ORFs: ORF1a, ORF1b, ns2 (nonstructural protein 2), HE (hemagglutinin-esterase), S (spike), ns12.9 (nonstructural protein of 12.9 kDa), E (envelope), M (membrane), and N (nucleocapsid). The replicase gene includes both ORF1a and ORF1b. The eGFP gene is inserted in the 3′ of ORF1b followed by T2A sequence. For rOC43-CoV2 S, the codon-optimized full-length S of SARS-CoV-2 WT (hCoV-19/USA_WA1/2020) was amplified by PCR and replaced with S of the rOC43-eGFP. (B) Representative plaque morphologies in crystal violet-stained RD cells infected with hOC43-WT and rOC43-eGFP at 2 dpi. (C) Growth kinetics of hOC43-WT, rOC43 (recombinant hOC43 virus without eGFP), and rOC43-eGFP over a 2-d time course in RD cells infected at a MOI = 0.01, n = 3 independent experiments with three replicates in each. Statistical analysis to compare each time point for each of the recombinant viruses against hOC43-WT or rOC43-eGFP virus was performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Mean values of the three independent experiments ± SD of the mean are shown. (D) Infection of Vero_hTMPRSS2 cells with supernatant from cells transfected with the eGFP reporter rOC43-CoV2 S. Images were acquired 72 hpi using a fluorescence microscope. (E) Detection of SARS-CoV-2 S protein in cells lysate by western blot. SARS-CoV-2 S and S2 was detected using anti-SARS-CoV-2 S2 mAb. Anti-OC43-N antibody was used as a loading control (data are representative of two independent experiments). (F) Maximum intensity projections of laser confocal microscopy z-stack images of infected Vero cells and BHK-21_hACE2 cells with rOC43-CoV2 S, stained live at 24 hpi (MOI = 1). (Scale bar, 20 μm.) Images are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (G) Flow cytometry analyses of Vero CCL81 cells inoculated with rOC43-CoV2 S, rOC43-eGFP, or eGFP-expressing SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 1), stained live at 24 hpi against SARS-CoV-2 S proteins. Representative dot plots of flow cytometry analyses showing double staining of eGFP and surface S, indicating the percentage of the gated cell population for each quadrant of the double staining. Representative histogram of flow cytometry analyses showing staining of surface S proteins, as well as the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) is plotted showed mean ± SEM (n = 3). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, each performed with triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (****P < 0.0001).

At this point, we transferred work from BSL-2 to BSL-3 containment to generate the rOC43 virus with its S gene swapped with the S gene from the SARS-CoV-2 (USA_WA1/2020 strain) (Fig. 1A). All subsequent experiments were performed under BSL-3 conditions until the virus was recharacterized as a BSL-2 agent by the IBC based on the data presented below demonstrating the attenuation of rOC43-CoV2 S relative to OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. SI Appendix, Table S1 documents the biosafety conditions for each experiment reported in this paper.

We established rOC43-CoV2 S recombinant virus recovery by eGFP expression following infection of Vero_hTMPRSS2 cells (Fig. 1D), confirming viral genome sequence by deep sequencing. Using SARS-CoV-2 S-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), immunoblotting of concentrated virions established the presence of S and S2 in rOC43-CoV2 S virions but not parental OC43 S (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Staining live cells with mAbs 24 hours postinfection (hpi) confirmed cell surface expression of OC43 N and SARS-CoV-2 S by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1F) and expression of SARS-CoV-2 S by flow cytometry (Fig. 1G) (15). Deep genome sequencing of the virus passaged seven times in Vero CCL81 cells revealed a deletion encoding 12 amino acids, including the polybasic cleavage motif (RRAR) at the S protein S1/S2 cleavage site, as previously reported with the passage of SARS-CoV-2 in Vero cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D) (16). We also found nucleotide changes generating multiple amino acid substitutions in ORF1a (R317C, A344V, M426I, F572S, A813D, S2488F, N2926S, R3782S) and ORF1b (S1092R, I1416V, D1607A, G1669S). This stock did not demonstrate a change in its rate or magnitude of replication in Vero CCL81 cells relative to the starting stock (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E).

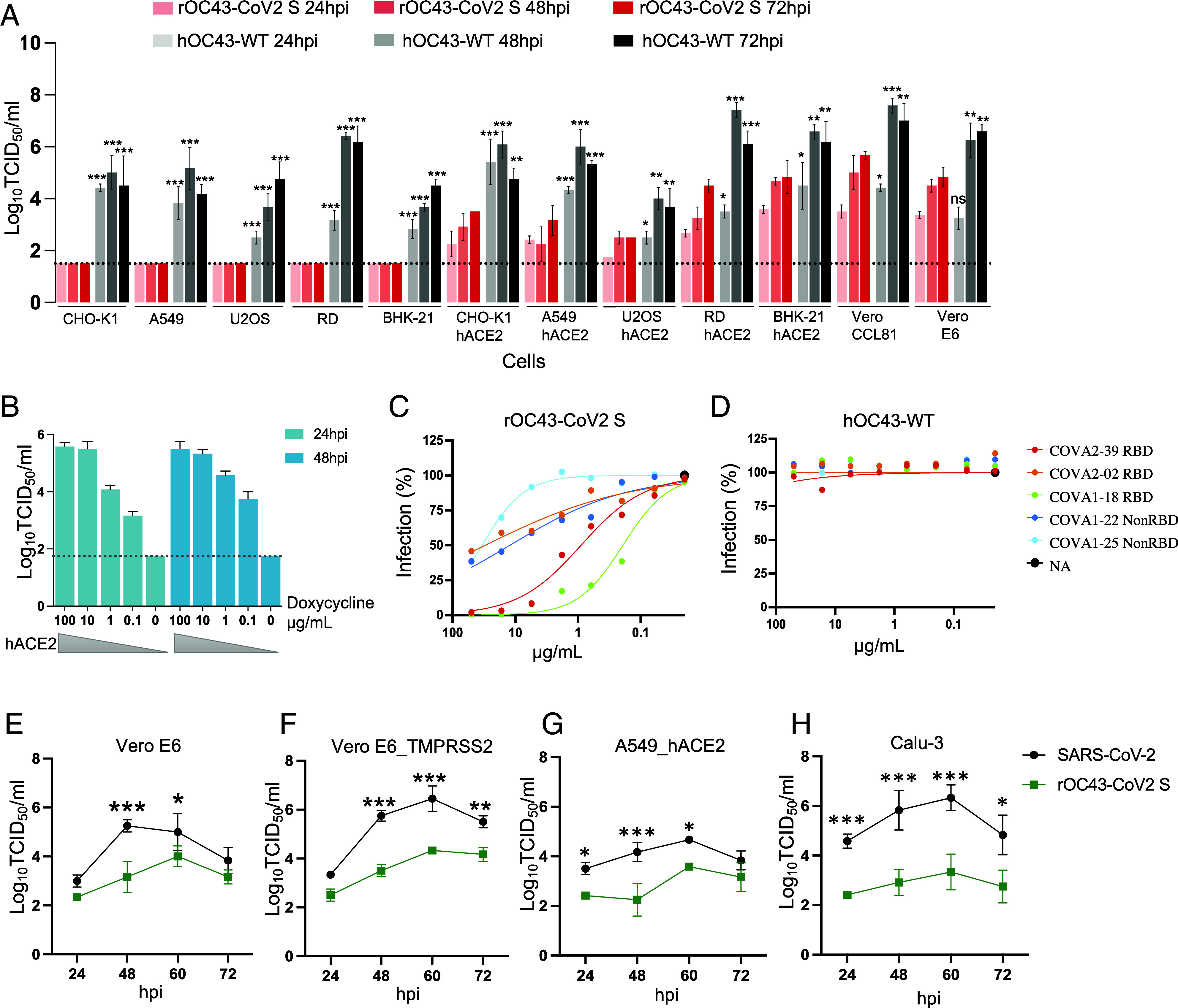

As expected from the diametric difference in receptor specificity, swapping hOC43 S with SARS-CoV-2 S altered viral tropism for cultured cells. Unlike parental hOC43-WT, which infected all cell types tested regardless of human ACE2 (hACE2) expression, hACE2 expression is required for rOC43-CoV2 S infectivity of CHO-K1, A549, U2OS, RD, and HBK-21 cells. Note also that rOC43-CoV2 S replicates more slowly than hOC43-WT in each of the cell lines tested, consistent with attenuation resulting from S replacement, possibly due to compromised interactions between the SARS-CoV-2 S OC43 M and E proteins that optimize CoV virion formation and function (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). We observed a positive correlation between rOC43-CoV2 S titer and hACE2 expression in stable RD cells with inducible hACE2 expression (Fig. 2B). Further, S-specific neutralizing Abs blocked infection with rOC43-CoV2 S (Fig. 2C) but not hOC43-WT (Fig. 2D), demonstrating that SARS-CoV-2 S is essential for infecting ACE2-expressing cells.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of an infectious rOC43-CoV2 S chimera in cells. (A) Growth kinetics of hOC43-WT and rOC43-CoV2 S over 3 d with cells infected at an MOI = 0.1. Three independent experiments with three replicates each. Statistical analysis comparing each time point was performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Mean values of the three independent experiments ± SD of the mean are shown. (B) Stable RD cells with inducible expression of hACE2 induced with the displayed concentration of doxycycline (RD_hACE2_dox) for 48 h, then infected with rOC43-CoV2 S at MOI = 0.01 (in triplicate). The percentage of eGFP-positive cells was quantified by flow cytometry 1 and 2 dpi. (C and D) SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific and NonRBD mAbs were tested for their capacity to neutralize rOC43-CoV2 S (C) or hOC43-WT (D) (n = 2 and 2, respectively). (E–H) Growth kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 (black) and rOC43-CoV2 S (green) over a 3-d time course in Vero E6 (E), Vero E6_TMPRSS2 (F), A549_hACE2 (G), and Calu-3 cells (H) infected at MOI = 0.01, n = 3 independent experiments with three replicates in each, statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA. (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001), the bar graph is shown as mean values ± SD. Grid line, limit of detection.

Extending these results, we generated rOC43 viruses expressing Delta and Omicron variant S. Infecting Vero CCL81, hACE2-expressing RD and BHK-21 cells with either virus resulted in syncytia formation (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), providing further evidence for the ability of hOC43 to fully support SARS-CoV-2 S function, including cell to cell fusion. We also compared the infection efficiency of rOC43-CoV2 S with rOC43-CoV2 Delta-S (B.1.617.2), and rOC43-CoV2 Omicron-S (B1.1.529) in cell culture (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). The rOC43-CoV2 S and rOC43-CoV2 Delta-S spread in Vero CCL81 cells, yielding 34% and 36% infected cells, respectively, at 24 hpi. By contrast, rOC43-CoV2 Omicron-S replicated more slowly, leading to 16% infected cells at 24 hpi. A similar pattern was seen in Vero_TMPRSS2 cells, in which 46% and 49% of cells were positive for WT and Delta-S, respectively, at 24 hpi, as opposed to 34% for Omicron-S.

Importantly, rOC43-CoV2 S replicates at a significantly slower rate than SARS-CoV-2 and reaches lower peak titers in Vero E6 and Vero E6_TMPRSS2 cells (Fig. 2 E and F). Similarly, rOC43-CoV2 S exhibits approximately 100-fold lower replication than SARS-CoV-2 in human lung cell lines (Fig. 2 G and H) and unlike SARS-CoV-2, fails to generate plaques in Vero E6_TMPRSS2 and A549 cells 3 dpi (days postinfection) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Despite SARS-CoV-2 and rOC43-CoV2 S using ACE2 as a common receptor, there are significant differences in their growth kinetics. As reported, rOC43-CoV2 S grows better at 35 °C (closer to the temperature of the human upper respiratory tract) vs. 37 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E), while SARS-CoV-2 grows optimally at 37 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 F and G) (17).

These findings demonstrate that rOC43-CoV2 S is highly attenuated in tissue culture, supporting its designation as a BSL-2 agent.

rOC43-CoV2 S Is Not Pathogenic in Mice.

We next examined the pathogenicity of rOC43-CoV2 S in established mouse models of SARS-CoV-2 and hOC43, using, respectively, transgenic hACE2 mice and WT neonatal C57BL/6 mice (older mice do not support OC43 infection) (18–21). We infected male and female 8-wk-old K18-hACE2 transgenic mice (n = 8 to 10/group) intranasally with 5 × 103 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of SARS-CoV-2 or rOC43-CoV2 S. We observed ruffled fur and significant weight loss in all SARS-CoV-2 infected K18-hACE2 mice over a 14-d infection (necessitating humane killing of 8/10 mice due to 30% weight loss or a pain score of 3). By contrast, rOC43-CoV2 S infected K18-hACE2 mice were indistinguishable from mock-inoculated hACE2 mice with similar weights and no mortality over the entire infection interval (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 3.

Pathogenicity of rOC43-CoV2 S in hACE2 transgenic mice and wild-type mice. (A and B) 8-wk-old K18-hACE2 transgenic mice were challenged intranasally with 5 × 103 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 WT or rOC43-CoV2 S. Mock-inoculated hACE2 mice were used as control. Weight loss (A) and survival (B) were recorded for 14 d. SARS-CoV-2 infected hACE2 mice displayed significant weight loss compared to rOC43-CoV2 S or mock-inoculated hACE2 mice (n = 8 to 10/group; male and female; two independent experiments). (C and D) Indicated organs were collected at 1, 4, and 7 dpi and infectious virus (C) or viral RNA titers (D) were determined by TCID50 or RT-qPCR, respectively. (n = 8/group at each time point; male and female; two independent experiments; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test was used to determine significance: ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05; asterisks indicate statistical significance as compared with rOC43-CoV2 S infection; symbols represent means ± SD. (E) Histopathology of rOC43-CoV2 S and SARS-CoV-2 infection of K18-hACE2 mouse, lung tissue of mice killed at 4 and 7 dpi after challenge is shown. Micrographs with 100× (or 400× for inserts) magnification of a representative lung section from each group are shown. (F) Survival curves of 7-d-old C57BL/6 mice after 2 × 104 TCID50 hOC43-WT and rOC43-CoV2 S infection (n = 6 to 8/group; male and female; one independent experiment).

We assessed viral burden in the lung, nose, spleen, and brain by measuring infectious virus and viral genomic RNA at 1, 4, and 7 dpi (Fig. 3 C and D). Predominant target organs were lungs at early time points and, variably, brains at later time points. SARS-CoV-2 replicated to high titers in the lung at 1 dpi decreasing at 4 and 7 dpi. In some but not all mice, brain titers gradually increased from 1 to 7 dpi. No infectious virus or viral RNA was detected in the spleen. For rOC43-CoV2 S, we failed to detect infectious virus or viral RNA in any organ for 7/8 mice, with minimal replication in the nose and lung of a single mouse on 1 dpi, possibly a remnant of the initial inoculum.

These data show that rOC43-CoV2 S is highly attenuated in vivo with little evidence of replication in hACE2 transgenic mice. Analysis of hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections from K18-hACE2 mice infected with SARS-CoV-2 showed a progressive inflammatory process (Fig. 3E). In SARS-CoV-2 infected lungs at 4 dpi, we found mild to moderate mononuclear lymphocyte infiltration in both perivascular (identified by luminal erythrocytes) and peribronchial regions. Bronchial epithelial cells showed mild changes. There was mild to moderate alveolar cell damage and limited microscopic hemorrhage. At 7 dpi, SARS-CoV-2 lungs showed moderate to severe mononuclear and lymphocyte infiltration in perivascular and peribronchial regions (Fig. 3E). Moreover, there was massive alveolar damage with hemorrhage and increased numbers of alveolar macrophages and lymphocytes, consistent with severe alveolitis and pneumonia.

In contrast, rOC43-CoV2 S-infected lungs showed no observable pathology at 4 dpi compared to mock-infected lungs. At 7 dpi, rOC43-CoV2 S infected lungs showed sporadic localized moderate pathology, including mild mononuclear cell infiltration in peribronchial and perivascular regions (Fig. 3E). Alveolar cell changes were minimal, and there was no increase in infiltrating alveolar macrophages or lymphocytes. Higher magnification of alveolar regions (lower right corners of the panels) showed that only SARS-CoV-2 infection caused alveolitis with infiltrating cells present in the alveolar lumen. Thus, while SARS-CoV-2 infection caused massive alveolitis/pneumonia, rOC43-CoV2 S caused minimum histopathological changes in lungs of K18-hACE2 mice.

To investigate the pathological characteristics of 7-d-old C57BL/6 mice infected with rOC43-CoV2 S, we infected groups of mice (n = 6 to 8/group) intranasally with 2 × 104 TCID50 rOC43-CoV2 S virus or hOC43-WT and observed mice over 14 d (Fig. 3F). Although the OC43 strain we used to construct rOC43-CoV2 S is attenuated in mice relative to mouse-adapted OC43, all mice receiving hOC43-WT virus (6/6) became moribund or succumbed to infection by 9 dpi. One of eight mice in the PBS group was found dead on day 14, which is likely unrelated to the control inoculation. Notably, none of the mice infected with rOC43-CoV2 S demonstrated morbidity.

Together, these results demonstrate that rOC43-CoV2 S is highly attenuated relative to SARS-CoV-2 and hOC43-WT in relevant mouse models, supporting its use at BSL-2 containment.

rOC43-CoV2 S Is an Optimal Proxy for SARS-CoV-2 in Functional Viral Assays.

How does rOC43-CoV2 S compare to recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S expressing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), the most widely used BSL-2 proxy virus for SARS-CoV-2, in VN experiments? We performed VN assays by infecting Vero E6 cells with, SARS-CoV-2, rOC43-CoV2 S, or recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-CoV2 S (rVSV-CoV2 S) in the presence of different concentrations of five human anti-S mAbs (three specifics for RBD, two non-RBD specific) (Fig. 4 A–C), and sera from five human’s post-mRNA vaccination (three doses) (Fig. 4 E–G).

Fig. 4.

Correlation analysis of SARS-CoV-2 and rOC43-CoV2 S VN. (A–C) SARS-CoV S mAbs were tested for flow-based VN activity against SARS-CoV-2 (A), rOC43-CoV2 S (B), or rVSV-CoV2 S (C), n = 3. (D) IC50 values of mAbs tested for neutralization of SARS-CoV-2, rOC43-CoV2 S, and rVSV-CoV2 S viruses on Vero E6 cells. (E–G) Human immune sera were tested for VN activity against SARS-CoV-2 (E), rOC43-CoV2 S (F), or rVSV-CoV2 S (G) on Vero E6 cells. (H) 50% neutralizing titer (NT50) values of all human immune sera tested for neutralization of SARS-CoV-2, rOC43-CoV2 S, and rVSV-CoV2 S. (I and J) IC50/NT50 values determined in Fig. 3 A–D and E–H were used to determine correlation between neutralization assays. Spearman’s correlation r and P values are indicated.

All mAbs neutralized SARS-CoV-2 and rOC43-CoV2 S (Fig. 4D) with similar 50% inhibitory concentration values (IC50, Log10[mAb] (ng/mL); 3.89 and 4.08 for SARS-CoV-2 and rOC43-CoV2 S, respectively), showing highly similar VN curves and identical rank order in VN activity. By contrast, mAbs demonstrated up to 10-fold lower IC50 values on rVSV-CoV2 S (IC50 = 3.03), with divergent activities relative to SARS-CoV-2. Human sera completely recapitulated this observation (Fig. 4H). The greatly improved ability of rOC43-CoV2 S vs. rVSV-CoV2 S to mimic SARS-CoV-2 in VN assays is clearly shown by the high correlation in VN values between SARS-CoV-2 and rOC43-CoV2 S (r = 0.9365, P < 0.0001) compared to rVSV-CoV2 S (r = 0.7727, P = 0.0088) (Fig. 4 I and J).

These findings demonstrate that rOC43-CoV2 S represents a major improvement over rVSV-CoV2 S as a SARS-CoV-2 surrogate in VN assays, likely due to recapitulating spike organization on the CoV virion surface as opposed to the higher density of S on the VSV surface (22).

rOC43-CoV2 S Is a Promising Live Attenuated Vaccine Vector.

Since rOC43-CoV2 S is highly attenuated in mice following intranasal inoculation, we evaluated its potential as a live attenuated, intranasal COVID vaccine. We immunized 8-wk-old K18-hACE2 transgenic mice intranasally with 5 × 103 TCID50 of rOC43-CoV2 S, SARS-CoV-2, or PBS (Fig. 5A). Four weeks postpriming, we collected sera and determined IgG titers against recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S and RBD protein by ELISA. Since most K18-hACE2 mice succumbed to SARS-CoV-2 infection, fewer animals were in this group.

Fig. 5.

Immunogenicity of rOC43-CoV2 S protects mice against SARS-CoV-2 infection. (A) Scheme depicting vaccination, bleeding, and SARS-CoV-2 challenge. (B–D) IgG serum responses of vaccinated mice were evaluated 4 wk after priming by ELISA for binding to SARS-CoV-2 S (B and D) or RBD (C). Panel D shows IgG heavy chain class of anti-S Abs. n = 3 to 9 per group; Mann–Whitney test: ***P < 0.001. Bars indicate median values. (E) Neutralizing antibody titers were determined by the focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT), n = 3 to 9 per group; Mann–Whitney test: ***P < 0.001. Bars indicate median values. Weights (F) and survival (G) curves of SARS-CoV-2 challenge in vaccinated mice (n = 3 to 9 per group; male and female; two independent experiments).

Despite its highly limited replication in K18-hACE2 mice, intranasal immunization induced levels of anti-S and anti-RBD specific IgG only slightly lower than SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 5 B and C). Ig subclass analysis indicated substantial class-switching with high levels of IgG2a and IgG2b anti-S Abs following infection with either virus, indicative of a robust CD4 T cell response (Fig. 5D). We confirmed anti-S Ab function by VN assays, which revealed nearly identical median titers in sera 28 d postvaccination with SARS-CoV-2 and rOC43-CoV2 S (1/1,148 vs. 1/1,043, respectively) (Fig. 5E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Neutralization of the Delta/B.1.617.2 variant was similarly decreased relative to wild type for all subgroups (neutralization titers decrease of 12 to 15-fold) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and D), with a larger parallel decrease (30 to 41-fold) observed using the Omicron B1.1.529 variant (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D).

At 29 d postpriming with rOC43-CoV2 S, we challenged mice by intranasal infection with 5 × 103 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 (strain 2019n-CoV/USA_WA1/2020) to evaluate vaccine protection (Fig. 5 F and G). Mock-vaccinated mice demonstrated sufficient weight loss to humanely kill all animals by 10 dpi. By contrast, mice receiving only a single dose of rOC43-CoV2 S were completely protected against weight loss, with 100% survival.

Collectively, these data demonstrate that rOC43-CoV2 S is highly immunogenic despite its high attenuation and elicits high titers of neutralizing antibodies that protect mice against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

rOC43-CoV2 S Induces Potent Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Serum and Mucosal Abs in Rhesus Macaques.

We next evaluated the immunogenicity of rOC43-CoV2 S in rhesus macaques (seronegative for both OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 were confirmed by ELISA as described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods), inoculating four rhesus macaques with 106 plaque-forming units (PFU) of rOC43-CoV2 S by intranasal route (IN) (Fig. 6A). Viral RNA levels measured by RT-qPCR in nasal swabs were maximal on day1 pi (postimmunization) (Fig. 6B). Infectious rOC43-CoV2 S was not detectable after day 1pi in either upper and lower airways in 3 of 4 immunized macaques (Fig. 6 C and D), This discrepancy between viral RNA and infectious virus is observed in many viral infections (23, 24), and maybe indicative of abortive replication and/or the generation of defective virions.

Fig. 6.

Timeline of the rhesus macaque study, rOC43-CoV2 S replication following intranasal immunization of rhesus macaques. (A) Experimental timing for the immunization of four macaques with the rOC43-CoV2 S and sampling schedules are shown. (B) Genomic SARS-CoV-2 S total RNA in upper airway was quantified by RT-qPCR (limit of detection: 2.5 log10 copies/mL). (C and D) Replication of rOC43-CoV2 S in Upper (C) and Lower (D) airways of macaques. Four macaques were immunized intranasally with 6.0 log10 PFU of rOC43-CoV2 S. Nasopharyngeal swabs (UA; daily from days 1 to 9 pi and 14 pi, without day 5, 6 pi), and BALs (LA; day 3 and 14 pi) were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Vaccine virus titers were determined by TCID50; expressed as log10 TCID50/mL (limit of detection: 0.7 log10 TCID50/mL).

None of the infected macaques exhibited clinical signs. Thus, as with mice, rOC43-CoV2 S does not detectably replicate in nonhuman primates (NHPs), causes no apparent disease, and is cleared in approximately 2 d. Consistent with these findings, when we infected human nasal (MucilAirTM) airway epithelial cells cultured at the air–liquid interface with rOC43-CoV2 S, we failed to detect viral gene expression via flow cytometry (GFP or cell surface S) 72 hpi, in contrast to SARS-CoV-2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

We then evaluated the kinetics and breadth of the serum antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 in NHPs inoculated with rOC43-CoV2 S (Fig. 7). S-specific and RBD-specific antibody responses were measured by ELISA at days 14, 24, and 42 after immunization (Fig. 7 A–C). We detected serum antiviral IgG, immunoglobulin A (IgA), and IgM Abs as early as 14 pi. Serum S-specific and RBD-specific IgG peaked at a titer of 4.98 to 5.90 log10 and 4.38 to 5.90 log10, at 42 pi (Fig. 7A), comparable in magnitude to sera from SARS-CoV-2 infected nonhuman primates (25, 26). Woolsey et al. reported that anti-spike/RBD IgG titers peaked at 15 to 21 pi (titer of ~3.8 log10) in the SARS-CoV-2 challenged African green monkeys (27). This difference may be due to variables including infection dose, primate species, age, and microbiome. rOC43-CoV2 S vaccinated animals developed S and RBD-specific IgA 14 d following the prime (Fig. 7B). Serum anti-S and anti-RBD IgM titers were also measured and peaked at 24 pi (Fig. 7C). Robust neutralizing titers against SARS-CoV-2 were detected in all rOC43-CoV2 S inoculated NHPs (Fig. 7 D–F), with diminished cross-reactivity with drift Delta and Omicron variants, as observed in mice. As expected, due to the absence of OC43 S, none of the NHPs developed neutralizing serum antibodies against hOC43-WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Fig. 7.

rOC43-CoV2 S induces humoral and mucosal immunity in macaques. (A–C) An ELISA measured anti-S and RBD serum IgG (A), IgA (B), and IgM (C) levels. (D–F) Serum neutralizing titers to SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020 (D), B.1.617.2/Delta (E), or B.1.1.529/Omicron (F). IC50 titers of sera were determined. The detection limit is 1.0 log10. (G and H) S- and RBD-specific mucosal IgA and IgG titers on indicated days pi in the Upper (G) and Lower (H) airways by ELISA. Endpoint ELISA titers of IgG, IgA, and IgM expressed as log10 values.

Vaccine-induced mucosal Ab responses offer the best chance of providing sterilizing or near sterilizing immunity since they have the potential to limit initial infection following a potential transmission event (28, 29). For SARS-CoV-2, it has been reported that antiviral IgA antibodies are produced prior to IgG antibodies and persist in sera and saliva of COVID-19 patients for 40 d post onset of symptoms (30–33). A recent study reports IgA antibodies in nasal secretions of COVID-19 patients (34). To evaluate the changes of mucosal Ab responses, we collected nasal swabs (NS) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) on day -4 before immunization and days 14, 24, and 42 after rOC43-CoV2 S inoculation. Two weeks after the vaccination, mucosal S/RBD-specific Ab responses were elicited in all rOC43-CoV2 S inoculated NHPs (Fig. 7 G and H), though these titers were lower compared to the serum. In the up airways, peaks in nasal swabs anti-IgA and anti-IgG titers could be observed by day 24pi and 42pi (anti-S and anti-RBD IgA geometric mean titers (GMTs) between 1.47 and 2.47 log10; anti-S and anti-RBD IgG GMTs between 1.43 and 2.47 log10). Vaccination also resulted in the induction of mucosal IgA and IgG in the lower airways (Fig. 7H). We assessed the S/RBD-specific antibody responses in BAL fluid from rOC43-CoV2 S vaccinated NHPs, which showed high levels of S and RBD-specific IgA and IgG antibodies at 24pi (anti-S and anti-RBD IgA GMTs between 1.90 and 3.47 log10; anti-S and anti-RBD IgG GMTs between 2.00 and 3.27 log10).

Thus, a single mucosal dose of rOC43-CoV2 S in macaques induced strong S-specific airway mucosal IgA and IgG responses and high levels of S-specific antibodies in serum that efficiently neutralize SARS-CoV-2 extending partially to naturally drifted variants. These findings support further efforts into developing rOC43-CoV2 S as a live attenuated COVID vaccine.

Discussion

Here, we show that rOC43-CoV2 S has enormous value as a reagent for measuring functional anti-SARS-CoV-2 S-specific antibodies in the context of a bona fide CoV that closely mimics VN activity against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, rOC43-CoV2 S is far superior to rVSV-CoV2 S, a standard SARS-CoV-2 proxy agent currently employed in VN assays. We are able to generate rOC43 S viruses for use in VN assays in only 1 to 2 wk, which is several weeks faster than for rVSVs. This enables updating of rOC43-CoV S viruses for VN assays to keep pace with the rapid evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.

Although further research is required, it seems likely that the sparse arrangement of S on CoVs (35, 36) vs. its higher density on rVSV-CoV2 S contributes to the differences we observe in absolute and rank order potency of VN mAb and polyclonal Abs (22). These differences are likely exacerbated in vivo due to the geometry-dependent enhancing effects of the complement component C1q on Ab VN activity (37).

Comparing spike expressing lentivirus pseudoparticles to SARS-CoV-2 in neutralization assays with sera from COVID 19 patients, Hyseni et al. reported a correlation coefficient of 0.84, which is close to the value we obtained using rOC43-CoV2 S (38). This and other spike-expressing nonreplicative pseudoviruses are BSL-2 agents but have limitations compared to rOC43-CoV2 S. These include contamination with particles expressing the orthologous entry glycoprotein, variation between stocks, and unsuitability for studying spike evolution in the context of a viral infection.

Due to its initial high case fatality rate and transmission rate, SARS-CoV-2 is categorized by the CDC as a risk group three (3) agent that should be handled in BSL-3 facilities with workers utilizing respiratory protection. The requirement to handle SARS-CoV-2 in BSL3 facilities has severely restricted its use in basic, translational, and clinical research laboratories. Based on the strong attenuation of rOC43-CoV2 S relative to SARS-CoV-2 and hOC43 that we have documented, we requested and were granted on July 7, 2022, adjustment of the biosafety classification of rOC43-CoV2 S from BSL-3 (which was used for all initial experiments) to BSL-2 by the NIH IBC. This decision was reviewed and affirmed by the NIH Dual Use Research Committee (IRE) and OSP on April 27, 2023. The rhesus experiments we report are enabled by the animal BSL-2 designation of rOC43-CoV2 S.

The decreased pathogenicity of rOC43-CoV2 S relative to OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 is expected based on established principles of viral evolution. Viral genes coevolve to maximize host-to-host transmission, which is based on both the site and magnitude of viral replication and aspects of pathogenicity (e.g., coughing, sneezing, social isolation) that enable viral dissemination. Replacing individual viral genes with paralogs from even closely related viruses is very unlikely to improve transmission in the original host species. This is particularly true when altering the specificity of the viral attachment protein for host receptors, which will alter host cell tropism and impair viral replication by modifying the host factors the virus must co-opt for biogenesis, including evading innate immune defense mechanisms.

Coronaviruses demonstrate remarkably robust genome recombination. Natural recombination between human SARS-CoV-2 strains clearly occurs (39, 40). Two recombination events between feline and canine CoVs generated a novel feline CoV (41). Recombination between SARS-CoV-2 and common cold CoV spike genes may have contributed to the evolution of the omicron lineage (42). Pediatric coinfection with OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in household surveys (43) and in 1% of moderately to severely ill SARS-CoV-2 infected children (44). Thus, it is plausible, perhaps even likely, that rOC43-CoV2 S-like recombinants are continuously generated naturally but cannot compete with either parental virus and rapidly become extinct. Understanding the evolution of CoVs in human and animal reservoirs requires a better understanding of the fitness costs of CoV recombination and mutation.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the unprecedented development of myriad vaccine platforms, from conventional inactivated whole-virion vaccines to novel mRNA vaccines, recombinant protein subunit vaccines, and viral vector vaccines (45) (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines). While current vaccines reduce COVID-19-associated hospitalization, they do not induce sufficiently high titers of long-lasting mucosal antibodies to prevent mild to moderate COVID-19. rOC43-CoV2 S may induce longer-lasting mucosal antibodies, warranting subsequent studies.

Indeed, we show that rOC43-CoV2 S has potential as a live attenuated vaccine based on a single dose protecting mice against lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection despite undetectable replication in the respiratory tract. This is similar to robust protection against mpox, and other poxviruses following vaccination with modified vaccinia Ankara (46, 47), despite its inability to replicate in vivo. How are immunogen levels sufficient to elicit such robust Ab responses? The extent to which rOC43-CoV2 S immunogenicity is dependent on infection of lung cells vs. resident or itinerant cells in the draining lymph node (48) is an important question to be addressed in future studies.

Respiratory tract immunization in macaques induces S-specific systemic and local mucosal responses that likely protect against disease. Based on using a common viral receptor, the entry-based tropism of rOC43-CoV2 S should be highly similar to SARS-CoV-2. By infecting similar respiratory cells, the local immune response to rOC43-CoV2 S should mimic the SARS-CoV-2 response, optimizing protection. This may provide a significant advantage over competitor vaccines whose proinflammatory properties limit their mucosal delivery.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, viral stock preparation, generation of stable RD cells with inducible expression of human ACE2 receptor, viral growth kinetics, neutralization assay, standard plaque assays, histopathology, RNA extraction, and RT-qPCR, detection of SARS-CoV-2 S by immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry, ELISA, and statistical analysis are described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Biosafety.

Following initial review and approval by the NIH IBC, we generated rOC43-CoV2 S virus under BSL-3 containment conditions. On July 7, 2022, after providing comprehensive evidence demonstrating the attenuation of rOC43-CoV2 S compared to parental OC43 and SARS-CoV-2 viruses in cultured cells and animal models, the IBC authorized using rOC43-CoV2 S under BSL-2 containment conditions. Following this approval, NIH created the Dual Use Research of Concern Institutional Review Entity (DURC-IRE), and the proposal was re-reviewed and approved by the DURC-IRE on April 27, 2023. A mitigation plan was not requested.

Generation of rOC43-CoV2 S.

For rOC43-CoV2 S, 140 μL of supernatant from hOC43-WT or SARS-CoV-2 infected cells was used for viral RNA extraction with a Qiagen RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, #52904) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Viral RNA was used to prepare cDNA with the AccuScript High-Fidelity 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Agilent, #200820) and random primer mix containing a mixture of hexamers and an anchored-dT primer per the manufacturer’s protocol. All primers used in this study are shown in SI Appendix, Table S2 with individual primer names referred to throughout the text. Five hOC43-WT fragments (F1-4, F6) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) were amplified from hOC43-WT viral cDNA using high-fidelity Prime Star GXL DNA polymerase (Takara Bio, #R050A) and corresponding pairs of primers. SARS-CoV-2 S gene (F5) was amplified from SARS-CoV-2 hCoV-19/USA_WA1/2020 strain or variants viral cDNA. Full-length rOC43-CoV2 S cDNA was assembled from the six viral cDNA fragments and one linker fragment into a circular DNA in a single CPER using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (14). Purified Five hOC43-WT fragments (F1-4, F6), SARS-CoV-2 S (F5) fragment, and hOC43-WT linker fragment were mixed in equimolar amounts (0.1 pM each) in a 50 µL reaction volume containing 200 µM of each dNTP, 1x PS GXL reaction buffer, and 2 μL of Prime Star GXL DNA polymerase. The following cycling conditions were used: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 12 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55 °C for 20 s, and extension at 68 °C for 10 min, followed by a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. Seed 106 cells HEK293-FT in 6-well plates O/N. The next day, we transfected cells with 5 μg of an pUC19-IRES-OC43-N and T7-polymerase plasmid using TransIT®-LT1 (Mirus Bio, #MIR 2300) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. 24 h posttransfection (hpt), 50 μL of CPERs without purification were transfected into hOC43 N-expressing HEK293-FT cells using Lipofectamine LTX Reagent with PLUS Reagent (Invitrogen, #15338030). 36 h post-CPER transfection, HEK293-FT cells were trypsinized and transferred to a confluent monolayer of Vero_hTMPRSS2 cells (30% HEK293-FT with 70% Vero_hTMPRSS2 cell) in a six-well plate. Supernatants containing viruses were harvested when eGFP was pronounced (3 to 6 d post-CPER transfection). For rOC43-eGFP, six overlapping fragments were from hOC43-WT. After CPER transfection, HEK293-FT cells were trypsinized and transferred to a confluent monolayer of RD cells (30% HEK293-FT with 70% RD cell) in a six-well plate. Supernatants containing viruses were harvested when cytopathic effect (CPE) was pronounced (3 d post-CPER transfection). Generation of rOC43-CoV2 S was performed in the NIAID SARS-CoV-2 Virology Core BSL-3 laboratory, strictly adhering to its standard operative procedures.

Mouse Experiments.

For mouse experiments, specific-pathogen-free, 8-wk-old male and female K18-hACE2 mice [B6. Cg-Tg (K18-ACE2) 2Prlmn/J, The Jackson Laboratory] strain were used. After intraperitoneal injection of 2.5% avertin with 0.016 mL/g body weight, mice were inoculated intranasally with 5 × 103 TCID50 SARS-CoV-2 or rOC43-CoV2 S or an equal volume of PBS as a mock-infection control in 50 µL (25 µL per nares). Body weight was monitored daily. Mice were humanely killed if their body weight dropped below 30% of their starting weight. Mice were killed at 1, 4, and 7 dpi for the following analyses: 1) viral burden in lungs, nasal wash, spleen, and brain (1, 4, and 7 dpi, infectious virus quantitation was performed by TCID50 assay and RT-qPCR assay), and 2) histopathological analysis (4 and 7 dpi). Sera were collected 4 wk postinoculated for titration of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. 29 d postinoculated, hACE2 transgenic mice were anesthetized, challenged intranasal with 5 × 103 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2, and monitored for 14 additional days. 7-d-old C57BL/6 mice were inoculated intranasally with 2 × 104 TCID50 hOC43-WT or rOC43-CoV2 S, or an equal volume of PBS as a mock-infection control in 10 µL. Survival was monitored. All animal experiments involving SARS-CoV-2 were conducted in a BSL-3 facility in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH under the NIAID DIR Animal Care and Use Committee approved animal study protocol LVD6E.

Macaque Experiments.

Adult rhesus macaques were inoculated by intranasal route with rOC43-CoV2 S. Plasma was collected prior to and following inoculation. BALs, nasopharyngeal swabs, and clinical data such as temperature, mass, respiratory rate, etc., were collected at baseline and throughout the study from animals housed at the NIH campus. Animal husbandry and experiments were conducted in accordance with appropriate Animal Care and Use Committee protocol approvals (NIH LVD26E).

The timeline of the experiment and sampling is summarized in Fig. 6A. Four juveniles to young adult male rhesus macaques, 6 to 10 y of age, confirmed to be seronegative for hOC43-WT and SARS-CoV-2, followed by adjustments for similar average weight of the animals, and immunized intranasally (0.5 mL per nostril) and intratracheally (0.5 mL) with a total does of 6.0 log10 PFU of rOC43-CoV2 S. Animals were observed daily from day -4 until the end of the study. Each time they were sedated, animals were weighed, their rectal temperature was taken, as well as the pulse in beats per minute and the respiratory rate in breaths per minute. In addition, the blood oxygen levels were determined by pulse oximetry.

Blood for analysis of serum antibodies was collected on day -4, 14, 24, and 42 pi. Nasopharyngeal swabs for vaccine virus quantification in the upper airways (UA) were performed on day -4 and daily from day 1 to day 9 pi (without day 5 and 6 pi) and 14 pi using cotton-tipped applicators. Swabs were placed in 1 mL medium with added antibiotic and antifungal, and vortexed for 10 s. Aliquots were then snap-frozen in dry ice and stored at −80 °C. BALs for analysis of mucosal IgA and IgG from the lower airways (LA) were done on day -4, 14, 24, and 42pi using 30 mL PBS (3 times 10 mL). For analysis of mononuclear cells, BAL was filtered through a 100 μm filter, and centrifuged at 500 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. The cell-free BAL was aliquoted, snap frozen in dry ice and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. We thank James S. Gibbs for outstanding scientific and technical assistance. We are grateful to Nicole Lackemeyer for BSL-3 training and support. We thank Alberto A. Amarilla and Alexander A. Khromykh for providing the linker sequence.

Author contributions

Z.H., J.M.B., J.W.Y., and J.M.F. designed research; Z.H., V.C., K.B., D.S.Y., J.H., J.J.S.S., A.C.B., R.F.J., K.T., and Z.-M.Z. performed research; I.K. and T.L. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Z.H., A.D.L.-M., and J.M.F. analyzed data; and J.W.Y. and Z.H. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

rOC43-CoV2 S from Vero CCL81 passage viral stock sequence data have been deposited in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) [PRJNA1064152 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1064152?reviewer=v428put86d4kb61hhpt600kpp3)] (49). All other data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Yewdell J. W., Individuals cannot rely on COVID-19 herd immunity: Durable immunity to viral disease is limited to viruses with obligate viremic spread. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009509 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yewdell J. W., Antigenic drift: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 54, 2681–2687 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du L., et al. , The spike protein of SARS-CoV—A target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 226–236 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keeton R., et al. , T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike cross-recognize Omicron. Nature 603, 488–492 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Premkumar L., et al. , The receptor binding domain of the viral spike protein is an immunodominant and highly specific target of antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabc8413 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y., et al. , A noncompeting pair of human neutralizing antibodies block COVID-19 virus binding to its receptor ACE2. Science 368, 1274–1278 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y., et al. , Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients’ B cells. Cell 182, 73–84.e16 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson C. B., Farzan M., Chen B., Choe H., Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3–20 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dieterle M. E., et al. , A replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus for studies of SARS-CoV-2 spike-mediated cell entry and its inhibition. Cell Host Microbe 28, 486–496.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong H. L., et al. , Robust neutralization assay based on SARS-CoV-2 S-protein-bearing vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudovirus and ACE2-overexpressing BHK21 cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 2105–2113 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Case J. B., et al. , Neutralizing antibody and soluble ACE2 inhibition of a replication-competent VSV-SARS-CoV-2 and a clinical isolate of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 28, 475–485.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vabret A., Mourez T., Gouarin S., Petitjean J., Freymuth F., An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36, 985–989 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaunt E. R., Hardie A., Claas E. C., Simmonds P., Templeton K. E., Epidemiology and clinical presentations of the four human coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 detected over 3 years using a novel multiplex real-time PCR method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 2940–2947 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amarilla A. A., et al. , A versatile reverse genetics platform for SARS-CoV-2 and other positive-strand RNA viruses. Nat. Commun. 12, 3431 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Muñoz A. D., Santos J. J. S., Yewdell J. W., Cell surface nucleocapsid protein expression: A betacoronavirus immunomodulatory strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2304087120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki M., et al. , SARS-CoV-2 variants with mutations at the S1/S2 cleavage site are generated in vitro during propagation in TMPRSS2-deficient cells. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009233 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riddell S., Goldie S., Hill A., Eagles D., Drew T. W., The effect of temperature on persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on common surfaces. Virol. J. 17, 145 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkler E. S., et al. , SARS-CoV-2 infection of human ACE2-transgenic mice causes severe lung inflammation and impaired function. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1327–1335 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng J., et al. , COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature 589, 603–607 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie P., et al. , A mouse-adapted model of HCoV-OC43 and its usage to the evaluation of antiviral drugs. Front. Microbiol. 13, 845269 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keyaerts E., et al. , Antiviral activity of chloroquine against human coronavirus OC43 infection in newborn mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3416–3421 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yahalom-Ronen Y., et al. , A single dose of recombinant VSV-∆G-spike vaccine provides protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Nat. Commun. 11, 6402 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin D. E., Why does viral RNA sometimes persist after recovery from acute infections? PLoS Biol. 20, e3001687 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen B., Julg B., Mohandas S., Bradfute S. B., Viral persistence, reactivation, and mechanisms of long COVID. Elife 12, e86015 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartman A. L., et al. , SARS-CoV-2 infection of African green monkeys results in mild respiratory disease discernible by PET/CT imaging and shedding of infectious virus from both respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008903 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urano E., et al. , COVID-19 cynomolgus macaque model reflecting human COVID-19 pathological conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2104847118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolsey C., et al. , Establishment of an African green monkey model for COVID-19 and protection against re-infection. Nat. Immunol. 22, 86–98 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell M. W., Moldoveanu Z., Ogra P. L., Mestecky J., Mucosal immunity in COVID-19: A neglected but critical aspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 11, 611337 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Nouën C., et al. , Intranasal pediatric parainfluenza virus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is protective in monkeys. Cell 185, 4811–4825.e17 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterlin D., et al. , IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabd2223 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu H. Q., et al. , Distinct features of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA response in COVID-19 patients. Eur. Respir. J. 56, 2001526 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma H., et al. , Serum IgA, IgM, and IgG responses in COVID-19. Cell Mol. Immunol. 17, 773–775 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seow J., et al. , Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1598–1607 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright P. F., et al. , Longitudinal systemic and mucosal immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 226, 1204–1214 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke Z., et al. , Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature 588, 498–502 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tai L., et al. , Nanometer-resolution in situ structure of the SARS-CoV-2 postfusion spike protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2112703118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosik I., et al. , C1q enables influenza hemagglutinin stem binding antibodies to block viral attachment and broadens the antibody escape repertoire. Sci. Immunol. 9, eadj9534 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyseni I., et al. , Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 lentiviral pseudotypes and correlation between pseudotype-based neutralisation assays and live virus-based micro neutralisation assays. Viruses 12, 1011 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells H. L., et al. , The coronavirus recombination pathway. Cell Host Microbe 31, 874–889 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Focosi D., Maggi F., Recombination in coronaviruses, with a focus on SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 14, 1239 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herrewegh A. A., Smeenk I., Horzinek M. C., Rottier P. J., de Groot R. J., Feline coronavirus type II strains 79–1683 and 79–1146 originate from a double recombination between feline coronavirus type I and canine coronavirus. J. Virol. 72, 4508–4514 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venkatakrishnan A. J., et al. , On the origins of Omicron’s unique spike gene insertion. Vaccines (Basel) 10, 1509 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Temte J. L., et al. , Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) codetection with influenza A and other respiratory viruses among school-aged children and their household members—12 March 2020 to 22 February 2022, Dane County, Wisconsin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, S205–S215 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keshavarz Valian N., Pourakbari B., Asna Ashari K., Hosseinpour Sadeghi R., Mahmoudi S., Evaluation of human coronavirus OC43 and SARS-COV-2 in children with respiratory tract infection during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 94, 1450–1456 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krammer F., SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 586, 516–527 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Earl P. L., et al. , Immunogenicity of a highly attenuated MVA smallpox vaccine and protection against monkeypox. Nature 428, 182–185 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolff Sagy Y., et al. , Real-world effectiveness of a single dose of mpox vaccine in males. Nat. Med. 29, 748–752 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynoso G. V., et al. , Lymph node conduits transport virions for rapid T cell activation. Nat. Immunol. 20, 602–612 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu Z., Recombinant OC43 SARS-CoV-2 Spike Replacement Virus: An Improved BSL-2 Proxy Virus for SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Assays. NCBI SRA. https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1064152?reviewer=v428put86d4kb61hhpt600kpp3. Deposited 12 January 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

rOC43-CoV2 S from Vero CCL81 passage viral stock sequence data have been deposited in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) [PRJNA1064152 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1064152?reviewer=v428put86d4kb61hhpt600kpp3)] (49). All other data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.