Significance

Planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling is crucial for cell–cell communication in health and disease. Thus, understanding molecular regulation mechanism of PCP is of both fundamental and translational importance. Dysregulation of the core PCP component Vangl2 has been associated with PCP disruption, neural tube defects, and cancers. Our study shows that the dynamic and reversible S-stearoylation cycle is an important regulatory mechanism for Vangl2 subcellular localization. Stearoylation-deficiency of Vangl2 reduces its membrane localization which is critical for normal PCP signaling. Our findings reveal an important role of stearoylation in regulating Vangl2 localization, PCP establishment during cell migration, and tumorigenesis, uncovering a potential link between deregulation of fatty acid metabolism and cancers.

Keywords: protein lipidation, planar cell polarity, Vangl2, stearoylation, click chemistry

Abstract

Defects in planar cell polarity (PCP) have been implicated in diverse human pathologies. Vangl2 is one of the core PCP components crucial for PCP signaling. Dysregulation of Vangl2 has been associated with severe neural tube defects and cancers. However, how Vangl2 protein is regulated at the posttranslational level has not been well understood. Using chemical reporters of fatty acylation and biochemical validation, here we present that Vangl2 subcellular localization is regulated by a reversible S-stearoylation cycle. The dynamic process is mainly regulated by acyltransferase ZDHHC9 and deacylase acyl-protein thioesterase 1 (APT1). The stearoylation-deficient mutant of Vangl2 shows decreased plasma membrane localization, resulting in disruption of PCP establishment during cell migration. Genetically or pharmacologically inhibiting ZDHHC9 phenocopies the effects of the stearoylation loss of Vangl2. In addition, loss of Vangl2 stearoylation enhances the activation of oncogenic Yes-associated protein 1 (YAP), serine-threonine kinase AKT, and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) signaling and promotes breast cancer cell growth and HRas G12V mutant (HRasV12)-induced oncogenic transformation. Our results reveal a regulation mechanism of Vangl2, and provide mechanistic insight into how fatty acid metabolism and protein fatty acylation regulate PCP signaling and tumorigenesis by core PCP protein lipidation.

Planar cell polarity (PCP) characterizes the asymmetric distribution of proteins and organelles in the plane of a cell sheet, which is crucial for proper embryogenesis and tissue homeostasis (1). The establishment of PCP relies upon the dynamic trafficking and asymmetric partitioning of core PCP components (2). Dysregulation of PCP proteins has been implicated in multiple human diseases, including birth defects and cancers (2–4). Van Gogh-like 1 and 2 (Vangl1/2) are core PCP components and play critical roles in PCP signaling (2, 5). Vangl proteins are predicted to contain a four-transmembrane domain flanked by N- and C-terminal cytoplasmic domains, but lack the known receptor or enzymatic activity (6). Dynamic localization of Vangl to specific microdomains is crucial for its function, but the underlying mechanism remains largely unknown (7–9). Phosphorylation of N-terminal domain of Vangl2 has been shown to facilitate Vangl2 membrane localization and regulates PCP establishment in the mouse limb bud (10, 11). Besides the plasma membrane, Vangl2 localizes in different intracellular membranous compartments and is associated with diverse activities. For example, Vangl2 forms complex with TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and targets TBK1 for degradation in response to viral infection (12). In addition, Vangl2 targets the lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2A) for lysosomal degradation in mesenchymal stem cells and both N- and C-terminal domains of Vangl2 are required for Vangl2–LAMP2A interaction (13). It has been well documented that the Vangl2 S464N mutant is trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and results in disruption of entire PCP signaling and neural-tube defects (14–18). These studies indicate that proper localization of Vangl2 is critical for its multiple functions.

Vangl2 has been recognized as a tumor suppressor due to attenuating canonical Wnt signaling (19–22). However, accumulating evidence indicated that up-regulation of Vangl2 contributes to tumorigenesis and tumor progression (23–28). Vangl2 is frequently up-regulated and displays dominant punctate cytoplasmic localization in breast, ovarian, and uterine cancers, correlated with poor prognosis and aggressiveness (23, 24, 28). It has been reported that Vangl2 may promote cancer cell growth and migration through interaction with Scribble which is often mislocalized in cancers (29–32). The mislocalized Vangl2 may also promote breast cancer cell growth by activating JNK signaling via interaction with p62/SQSTM1 in endosomes (24). In addition, Vangl2 is highly expressed in human rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) and enhances stem cell self-renew and growth in RMS through RhoA signaling (25). The immunofluorescence data showed that Vangl2 exhibits punctate cytoplasmic localization in the RMS cells (25). These studies suggested that mislocalization of Vangl2 may contribute to tumorigenesis. However, the mechanism of Vangl2 mislocalization in cancers remains poorly understood.

Various types of fatty acids can be covalently attached to proteins, termed protein fatty acylation. Each type of fatty acid has distinct biochemical properties, enabling protein fatty acylation to regulate protein trafficking, subcellular localization, and protein–protein interactions (33, 34). Dysregulation of protein fatty acylation has been associated with multiple human diseases, including neurological disorders and cancers (35, 36). Protein fatty acylation enzymes and their substrates are emerging as attractive drug targets (37). Using chemical reporters of protein fatty acylation, we find that Vangl2 is stearoylated at a conserved cysteine residue within the N-terminal domain. Stearoylation of Vangl2 is a dynamic and reversible process which is mainly regulated by acyltransferase ZDHHC9 and deacylase APT1. Importantly, Vangl2 stearoylation plays a regulatory role in its membrane localization and wound-induced cell polarization. Loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promoted the activation of YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling and increased breast cancer cell growth and HRasV12-induced oncogenic transformation. Overall, our findings indicate that ZDHHC9-APT1-mediated dynamic stearoylation of Vangl2 regulates Vangl2 subcellular localization, PCP establishment during cell migration, and oncogenic signaling and provides mechanistic insight into how fatty acid metabolites regulate PCP and tumorigenesis by stearoylation of core PCP proteins.

Results

Vangl2 Is Stearoylated at an Evolutionarily Conserved Cysteine Residue.

To identify potential fatty acylated proteins, we carried out chemical proteomic profiling of fatty-acylation in HEK293T or HCC1806 cells using chemical reporters (Fig. 1A), followed by copper-catalyzed biotin azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC), streptavidin-based enrichment, and proteomic analysis through liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The MS data revealed that endogenous Vangl1 and Vangl2 could be metabolically labeled by clickable fatty acid probes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), consistent with previous proteomic studies of fatty acylation in which Vangl1 was detected in Jurkat T cells and Hela cells (38, 39), and Vangl2 was detected in neural cells (40, 41). The chemical proteomic profiling data indicate that Vangl1 and Vangl2 might be fatty acylated, but further biochemical studies are required to validate the findings.

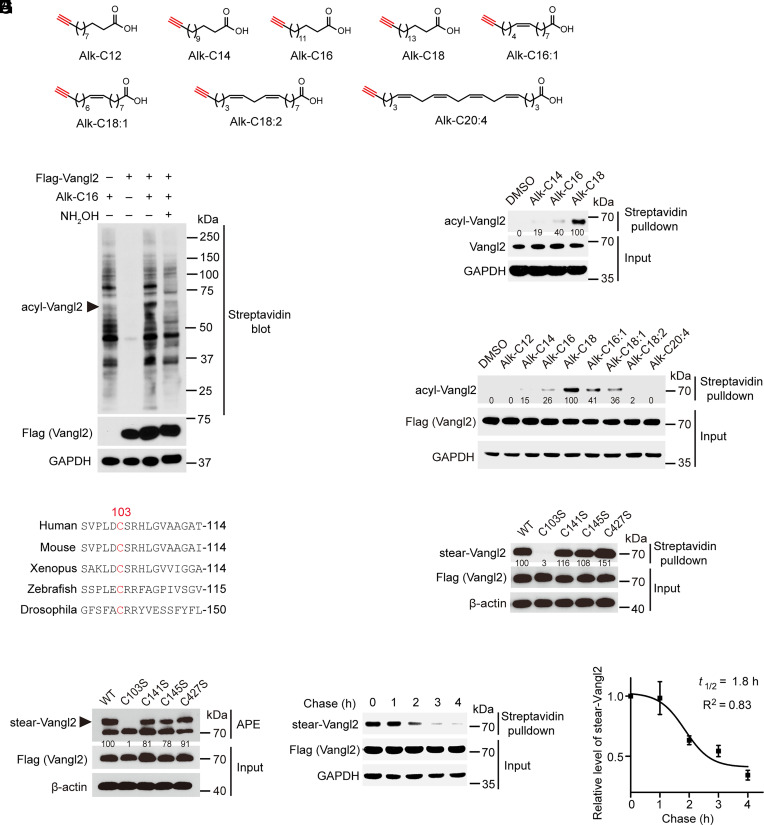

Fig. 1.

Vangl2 is stearoylated at an evolutionarily conserved cysteine residue. (A) Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for monitoring protein fatty acylation in this study. (B) Validation of Vangl2 fatty acylation by metabolic labeling with chemical reporters, hydroxylamine (NH2OH) treatment and streptavidin blot. (C) Confirmation of endogenous Vangl2 fatty acylation in HCC1806 cells by metabolic labeling and streptavidin bead pulldown. Relative fatty acylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (D) Characterization of fatty acid selectivity on exogenous Flag-Vangl2 acylation by metabolic labeling and streptavidin bead pulldown. Relative fatty acylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (E) ClustalW alignment of N-terminal domain sequences of Vangl2 proteins across different species, including human, mouse, Xenopus, zebrafish, and Drosophila. (F) Metabolic labeling followed by streptavidin bead pulldown and western blotting analysis showed that mutation of cysteine 103 to serine completely abolished Vangl2 stearoylation. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (G) Acyl-PEG exchange (APE) assay and mutagenesis analysis confirmed that Vangl2 stearoylation occurred on cysteine 103. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (H) Pulse–chase analysis showed dynamics of Vangl2 stearoylation. (I) Calculation of the half-life of Vangl2 stearoylation turnover from pulse–chase assays. All blots are representatives of at least three independent experiments. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

To characterize fatty acylation of Vangl2, the construct encoding N-terminal Flag-tagged Vangl2 was transfected into HEK293T cells. About 24 h later, the cells were metabolically labeled with 25 µM of probe Alk-C16, followed by click reaction with biotin-azide. The streptavidin blot showed that the Flag-tagged Vangl2 could be labeled by Alk-C16 (Fig. 1B). After treatment with 2.5% (v/v) hydroxylamine (NH2OH), the probe-labeled Vangl2 was substantially reduced, suggesting that Vangl2 is fatty acylated on cysteine residue via thioester bond (Fig. 1B). In addition, Flag-Vangl1 could also be labeled by Alk-C16 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Previous studies indicated that Vangl2 plays an important role in PCP signaling, cilia positioning, neural-tube defects, and cancers (5, 15, 24, 25, 42, 43), and we thus focused our studies on fatty acylation of Vangl2. To test whether endogenous Vangl2 could be fatty acylated, HCC1806 cells were metabolically labeled with three different probes, including Alkynyl myristic acid (Alk-C14), Alkynyl palmitic acid (Alk-C16), and Alkynyl stearic acid (Alk-C18). After click reaction with biotin-azide, the fatty acylated proteins were enriched by streptavidin bead pulldown and then subjected to western blotting using anti-Vangl2 antibody. The results showed that the endogenous Vangl2 was indeed fatty acylated and displayed a strong preference for the 18-carbon stearic acid (Fig. 1C), suggesting that Vangl2 is stearoylated.

To further validate the fatty acylation type of Vangl2, we used a series of clickable fatty acid probes to metabolically label the HEK293T cells expressing Flag-Vangl2. The streptavidin bead pulldown results showed that alkynyl stearic acid (Alk-C18) exhibited the highest labeling efficiency for Flag-tagged Vangl2 (Fig. 1D), confirming the stearoylation of Vangl2. The alkynyl palmitic acid (Alk-C16), alkynyl palmitoleic acid (Alk-C16:1), and alkynyl oleic acid (Alk-C18:1) could also label Vangl2, but the labeling efficiency of the probes was much lower than that of alkynyl stearic acid. The alkynyl lauric acid (Alk-C12), alkynyl myristic acid (Alk-C14), alkynyl linoleic acid (Alk-C18:2), and alkynyl arachidonic acid (Alk-C20:4) displayed lowest labeling efficiency. Together, these results confirmed that Vangl2 is stearoylated.

We next set out to identify potential stearoylation site(s) of Vangl2. After alignment of the Vangl2 protein sequences across multiple species, including human, mouse, Xenopus, zebrafish, and Drosophila, we found one evolutionarily conserved cysteine residue (Cys103) within the N-terminal domain (Fig. 1E). Cys103 is also conserved in human Vangl1 and Vangl2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). To determine the stearoylation site(s), we mutated all the cysteine residues of Vangl2 to serines (C103S, C141S, C145S, and C427S). HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-tagged wild-type (WT) Vangl2 or the mutant constructs, and metabolically labeled with Alk-C18. Streptavidin bead pulldown results showed that C103S mutation completely abolished Vangl2 stearoylation, whereas other cysteine mutations showed little effect (Fig. 1F). To further confirm the stearoylation site, we performed aycl-PEG exchange (APE) assay which induces a mobility-shift on S-acylated proteins by adding maleimide-functionalized polyethylene glycol (PEG) (44). The APE results revealed that there is only one slower migrating PEGylation-induced band corresponded to mono-S-acylated Vangl2 WT, whereas the slower migrating band is abolished by the C103S mutation, but not other mutations (Fig. 1G). In addition, APE results indicated that about 50% of Vangl2 protein is stearoylated in cells. Together, these results indicated that Cys103 is the primary site of Vangl2 stearoylation.

We speculated that Vangl2 may undergo dynamic cycles of stearoylation and destearoylation. Then we carried out pulse–chase assays to calculate the turnover rate of stearic acid on Vangl2. Multiple pulse–chase experiments showed that the half-life of Vangl2 stearoylation is about 1.8 h, while the protein remained stable during the assay (Fig. 1 H and I), suggesting stearoylation of Vangl2 is indeed a dynamic process.

Stearoylation Cycle of Vangl2 Is Regulated by Acyltransferase ZDHHC9 and Deacylase APT1.

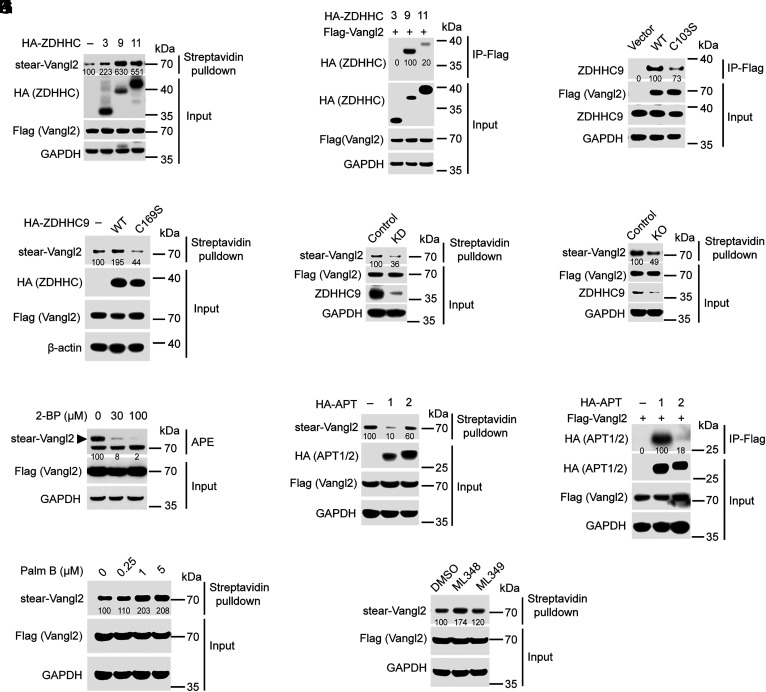

To identify enzymes regulating the dynamic stearoylation cycle of Vangl2, we performed screening of the potential protein acyltransferases (PATs). HA-tagged human ZDHHC family of PATs and Flag-tagged Vangl2 were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, and metabolically labeled with probe Alk-C18. The streptavidin bead pulldown results revealed that overexpression of ZDHHC9 or ZDHHC11 could substantially increase the stearoylation level of Vangl2, with ZDHHC9 as the most potent inducer (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) results showed that exogenous ZDHHC9 could directly interact with Vangl2 (Fig. 2B). When expressed at higher levels, ZDHHC11 could also interact with Vangl2, but the interaction was much weaker than that of ZDHHC9 (Fig. 2B). To further characterize the interaction between ZDHHC9 and Vangl2, we cotransfected Flag-Vangl2 WT and the stearoylation-deficient mutant (C103S) into HEK293A cells. The co-IP results showed that both Vangl2 WT and the C103S mutant could interact with endogenous ZDHHC9, but the interaction between the C103S mutant and ZDHHC9 was much weaker than that of Vangl2 WT and ZDHHC9 (Fig. 2C), indicating that the stearoylation site is required for Vangl2 interaction with ZDHHC9. In addition, overexpression of ZDHHC9 WT, but not the catalytic dead mutant of ZDHHC9 (C169S), substantially increased the Vangl2 stearoylation level (Fig. 2D), suggesting that ZDHHC9 enzymatic activity is required for promoting Vangl2 stearoylation. Furthermore, ZDHHC9 knockdown using shRNA (Fig. 2E) or knockout using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Fig. 2F) substantially decreased Vangl2 stearoylation. Consistently, treatment with the pan-ZDHHC inhibitor 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) reduced the stearoylation level of Vangl2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2G). Together, these results revealed that ZDHHC9 is the primary stearoyl acyltransferase of Vangl2.

Fig. 2.

Stearoylation cycle of Vangl2 is regulated by ZDHHC9 and APT1. (A) Overexpression of HA-ZDHHC9 or ZDHHC11 substantially enhanced stearoylation level of Vangl2 in HEK293T cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (B) Co-IP assay showed the interactions between HA-ZDHHC3/9/11 and Flag-Vangl2 in HEK293T cells. Relative HA-ZDHHC3/9/11 level is indicated from the IP-Flag samples. (C) Co-IP assay showed the interactions between endogenous ZDHHC9 and Flag-Vangl2 in HCC1806 cells. Relative ZDHHC9 protein level is indicated from the IP-Flag samples. (D) The catalytic dead mutant of ZDHHC9 (C169S) failed to promote Vangl2 stearoylation in HEK293T cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (E) ZDHHC9 knockdown (KD) using shRNA substantially decreased Vangl2 stearoylation level in MCF10A cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (F) ZDHHC9 knockout (KO) using CRISPR-Cas9 substantially decreased Vangl2 stearoylation level in MCF10A cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (G) APE assay showed inhibition of Vangl2 stearoylation by the pan-ZDHHC inhibitor 2-BP in HEK293T cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (H) Overexpression of thioesterase APT1, but not APT2, substantially decreased Vangl2 stearoylation in HEK293T cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (I) Co-IP assay showed the direct interactions between APT1 and Vangl2 in HEK293T cells. Relative HA-APT1/2 protein level is indicated from the IP-Flag samples. (J) Streptavidin bead pulldown showed that the pan-APT inhibitor Palmostatin B (Palm B) treatment could increase Vangl2 stearoylation level in HEK293T cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. (K) Streptavidin bead pulldown showed that the APT1 inhibitor ML348, but not APT2 inhibitor ML349, could substantially increase Vangl2 stearoylation in HEK293T cells. Relative stearoylation level of Vangl2 is indicated. All blots are representatives of at least three independent experiments.

Acyl-protein thioesterase 1 and 2 (APT1 and 2) and several α/β-hydrolase domain-containing proteins (ABHDs) have been characterized as potential deacylases (45, 46). To identify the destearoylase of Vangl2, Flag-tagged Vangl2, and APT1/2 or ABHDs were cotransfected into HEK293T cells, followed by metabolic labeling with Alk-C18. Streptavidin bead pulldown results displayed that overexpression of APT1 substantially decreased the stearoylation level of Vangl2, while overexpression of APT2 showed only a modest effect (Fig. 2H and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Consistently, our co-IP results revealed that APT1 could physically interact with Vangl2, whereas the interaction between APT2 and Vangl2 was much weaker (Fig. 2I). In addition, the pan-APT inhibitor Palmostatin B could increase the stearoylation level of Vangl2 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2J). Furthermore, the APT1-specific inhibitor ML348 could substantially increase the stearoylation level of Vangl2, while the APT2-specific inhibitor ML349 exhibited only a minor effect (Fig. 2K), confirming that APT1 is the major destearoylase of Vangl2. Together, these results suggested that Vangl2 stearoylation cycle is mainly regulated by ZDHHC9 and APT1.

To determine where Vangl2 stearoylation cycle takes place, we studied subcellular localization of ZDHHC9 and APT1. Our immunofluorescence (IF) results showed that HA-ZDHHC9 could colocalize with the Golgi marker GM130 and the ER marker Calnexin in HCC1806 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), indicating that ZDHHC9 is mainly localized in the Golgi and ER, consistent with the previous study (47). Our cell fractionation and IF results revealed that APT1 is mainly localized in the cytosol and partially in the plasma membrane and nucleus (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), consistent with the previous study (48). Moreover, we found that APT1 could colocalize with Vangl2 at the plasma membrane in MCF10A cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Together, these results suggested that Vangl2 may be stearoylated in the Golgi and ER and might be destearoylated at the plasma membrane.

Stearoylation of Vangl2 Is Required for Vangl2 Membrane Localization and PCP Establishment During Cell Migration.

Fatty acylation plays an important role in protein trafficking, localization, and protein–protein interactions. Vangl2 S464N mutant has been shown to mislocalize to puncta within the cytoplasm and impair PCP (14–16, 18). Interestingly, our results showed that the stearoylation level of Vangl2 S464N mutant is substantially decreased (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), implying that stearoylation may play a regulatory role in Vangl2 subcellular localization.

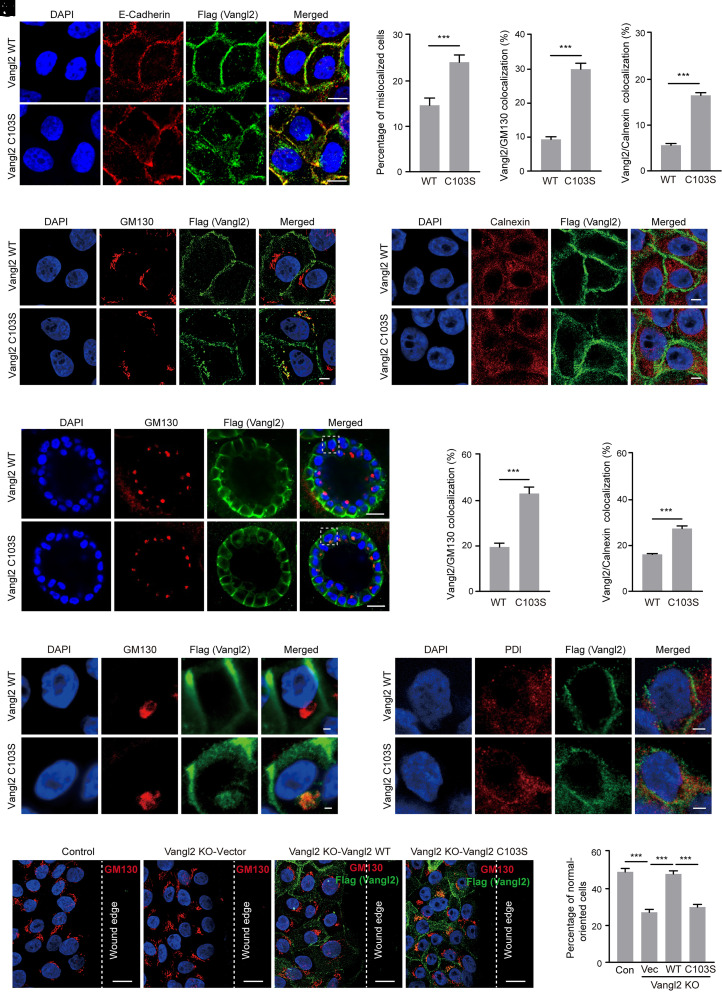

MCF10A is a nontransformed human breast epithelial cell line. To test the role of Vangl2 stearoylation in its subcellular localization, we generated MCF10A stable cell lines expressing Flag-tagged Vangl2 WT and the stearoylation-deficient mutant (C103S). Western blot results showed that the expression levels of Vangl2 WT and the C103S mutant proteins were comparable in the established stable cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Coimmunostaining of Vangl2 and the intercellular junction marker E-Cadherin in MCF10A cells showed that Vangl2 WT is mainly localized at the plasma membrane, whereas Vangl2 C103S showed punctate cytoplasmic localization and accumulation around the nucleus (Fig. 3A). The percentage of cells with Vangl2 mislocalization was quantified in each cell line, confirming that membrane localization of Vangl2 C103S was disrupted (Fig. 3B). To identify the intracellular compartments in which Vangl2 C103S was trapped, we coimmunostained Vangl2 with the Golgi marker GM130 and the ER marker Calnexin in MCF10A stable cells and quantified Vangl2 colocalization with the markers. The IF and quantification results showed that the colocalization level of Vangl2 C103S with GM130 or Calnexin was significantly increased compared with that of Vangl2 WT, suggesting that Vangl2 C103S was trapped in both the Golgi and the ER (Fig. 3 C–F). Sec24b has been shown to sort Vangl2 into COPII vesicles for trafficking from the ER to the Golgi (16). The Vangl2 S464N mutant fails to be sorted into COPII vesicles and is trapped in the ER. Surprisingly, our co-IP results showed that the interaction between Sec24b and Vangl2 C103S was substantially decreased (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), indicating that loss of stearoylation may lead to improper sorting of Vangl2. A recent study showed that Vangl2 targets LAMP2A for degradation in lysosomes (13). Interestingly, our co-IP results showed that the interaction between Vangl2 C103S and LAMP2A was substantially increased (SI Appendix, Fig. S12), indicating that stearoylation may regulate Vangl2 distribution in lysosomes. Taken together, these results revealed that stearoylation of Vangl2 is required for its membrane localization in MCF10A cells under monolayer culture conditions.

Fig. 3.

Stearoylation of Vangl2 regulates Vangl2 membrane localization and PCP establishment during cell migration. (A) Immunofluorescence (IF) assay showed subcellular localization of Vangl2 in MCF10A stable cells under monolayer culture conditions. The C103S mutation disrupted Vangl2 membrane localization in MCF10A cells. Cells were stained with anti-E-Cadherin antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar,10 μm.) (B) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and E-Cadherin was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (C) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant and the Golgi marker GM130 in MCF10A cells. Cells were stained with anti-GM130 antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (D) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and GM130 was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (E) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant and the ER marker Calnexin in MCF10A cells. Cells were stained with anti-Calnexin antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (F) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and Calnexin was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (G) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant and GM130 in MCF10A cells under 3D culture conditions. Cells were stained with anti-GM130 antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar,10 μm.) (H) High-resolution image showed the colocalization of Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant and GM130 in MCF10A cells under 3D culture conditions. Zoomed-in image of the area enclosed by the white dotted line box in (G). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (I) The percentage of acini with Vangl2 and GM130 colocalization was quantified. At least 100 acini were counted for each cell line. (J) High-resolution IF image showed the colocalization of Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant and PDI in MCF10A cells under 3D culture conditions. Cells were stained with anti-PDI antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (K) The percentage of acini with Vangl2 and PDI colocalization was quantified. At least 100 acini were counted for each cell line. (L) IF assay showed GM130 orientation in the wound edge cells using the indicated MCF10A stable cells at 20 h postscratch. Cells were stained with anti-GM130 antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). The dotted line indicates the wound edge. (Scale bar,10 μm.) (M) Quantification of the percentage of the normal-oriented cells at the wound edge. At least 400 cells were counted for each cell line. All data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. P values were determined using two-tailed t-tests. ***, P < 0.001.

Under three-dimensional (3D) culture conditions, MCF10A cells form acini-like spheroids and recapitulate many features of glandular architecture in vivo. We next asked whether stearoylation of Vangl2 regulates its subcellular localization under 3D culture conditions. MCF10A cells stably expressing Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant were cultured on Matrigel for 8 d, followed by indirect IF staining with anti-Flag and anti-GM130 antibody or anti-PDI antibody and confocal microscopy imaging. Vangl2 showed a clear membrane localization in the Vangl2 WT acini, whereas Vangl2 C103S displayed a cytoplasmic punctate pattern and colocalization with GM130 in the acini (Fig. 3 G and H). The percentage of acini with Vangl2 and GM130 colocalization was quantified in each cell line, confirming that Vangl2 C103S significantly increased its accumulation in the Golgi (Fig. 3I). In addition, the colocalization of Vangl2 C103S with the ER marker PDI was also significantly increased compared with that of Vangl2 WT, suggesting that Vangl2 C103S was trapped in the ER (Fig. 3 J and K and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Together, these results suggested that stearoylation of Vangl2 is required for its membrane localization under both monolayer and 3D culture conditions.

Vangl2 is a master regulator of PCP and essential for PCP establishment (8, 49, 50). We then asked whether stearoylation of Vangl2 can regulate PCP establishment. To rule out the effect of endogenous Vangl2, we knocked out Vangl2 using the CRISPR-Cas9 system and reintroduced Flag-tagged Vangl2 WT and the C103S mutant into the MCF10A cells. Western blot confirmed Vangl2 knockout (KO) efficiency (SI Appendix, Fig. S14) and the comparable expression levels of Vangl2 WT and the C103S mutant in the stable cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Using the previously described methods (49–51), we evaluated PCP establishment during cell migration in the stable cells. Briefly, the cells were fixed at 24 h postscratch and immunostained with anti-GM130 antibody to show the Golgi position relative to the nucleus in the wound edge cells. Golgi located within the wound edge-facing 120° sector is classed as normal-oriented cell, and the whole or majority of the Golgi localized outside the 120° sector is classed as misoriented cell (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). Our IF results showed that Golgi appeared randomly localized in the Vangl2 KO cells at the wound edge compared with that of control cells, which displayed a higher proportion of wound edge cells with the Golgi facing the direction of cell migration (Fig. 3L), consistent with the previous study (49). Quantification results revealed that about 50% of the control cells at the wound edge were normal-oriented, whereas only around 27% in the Vangl2 KO cells (Fig. 3M), confirming the crucial role of Vangl2 in PCP establishment during cell migration. Reintroducing of Vangl2 WT into the Vangl2 KO cells significantly increased the normal-oriented cells (about 48%) at the wound edge, whereas only about 30% in the C103S mutant cells (Fig. 3 L and M), suggesting that stearoylation of Vangl2 plays an important regulatory role in PCP establishment during cell migration. In addition, we quantified the Golgi orientation of the wound edge cells in each cell line using circular histograms. The quantification results revealed that expression of Vangl2 WT could mostly rescue the disrupted Golgi orientation in the Vangl2 KO cells, whereas expression of Vangl2 C103S displayed only modest effect (SI Appendix, Fig. S17), confirming that Vangl2 stearoylation could regulate PCP establishment during cell migration. It has been shown that plasma membrane-localized Vangl2 can regulate Golgi reorientation in migrating cells by regulating RhoA-ROCK signaling (52–54). Thus, the reduced plasma membrane localization of Vangl2 C103S may disrupt the RhoA-ROCK signaling and thereby impair Golgi reorientation. Taken together, our results suggested that stearoylation of Vangl2 plays an important regulatory role in Vangl2 membrane localization and PCP establishment during cell migration.

ZDHHC9 Regulates Vangl2 Membrane Localization and PCP Establishment During Cell Migration.

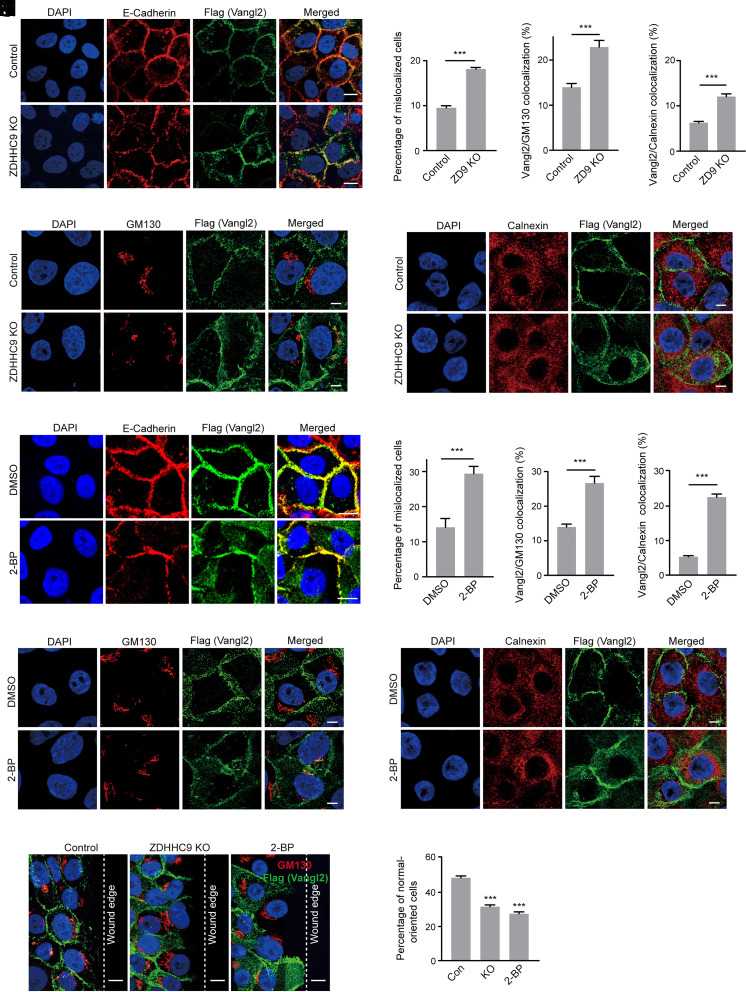

We have demonstrated that ZDHH9 is the major acyltransferase mediating stearoylation of Vangl2, then we asked whether ZDHHC9 could regulate Vangl2 subcellular localization. We performed IF assay to analyze Vangl2 localization using the MCF10A stable cells with ZDHHC9 knockout (KO) based on the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Our IF results revealed that ZDHHC9 was substantially decreased and Vangl2 membrane localization was disrupted in ZDHHC9 knockout MCF10A cells (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Quantification analysis confirmed that loss of ZDHHC9 significantly increased the percentage of cells with mislocalized Vangl2 (Fig. 4B), indicating that ZDHHC9 is important for Vangl2 membrane localization. To determine the intracellular compartments in which Vangl2 was accumulated in ZDHHC9 KO cells, we coimmunostained Vangl2 with the Golgi marker GM130 and the ER marker Calnexin and quantified Vangl2 colocalization with the markers. Our results showed that the colocalization level of Vangl2 with GM130 or Calnexin was significantly increased in ZDHHC9 KO cells compared with that of control cells (Fig. 4 C–F), suggesting that Vangl2 was trapped in both the Golgi and the ER after blocking ZDHHC9. We previously demonstrated that the pan-ZDHHC inhibitor 2-BP could inhibit Vangl2 stearoylation in a concentration-dependent manner. After treatment with 30 µM of 2-BP for 12 h, Vangl2 was mislocalized in MCF10A cells (Fig. 4G). Quantification data confirmed that ZDHHC9 inhibition with 2-BP significantly increased the percentage of MCF10A cells with mislocalized Vangl2 (Fig. 4H), consistent with the effect of ZDHHC9 KO. Colocalization analysis of Vangl2 with GM130 or Calnexin showed that Vangl2 in the Golgi or the ER was significantly increased in the 2-BP treated cells compared with that of control cells (Fig. 4 I–L), consistent with the phenotype in ZDHHC9 KO cells. We speculate that Vangl2 may be stearoylated by ZDHHC9 in the ER and the Golgi and thereby facilitate its trafficking to the plasma membrane, while ZDHHC9 inhibition may lead to Vangl2 accumulation in the ER and the Golgi.

Fig. 4.

ZDHHC9 is required for Vangl2 membrane localization and PCP establishment during cell migration. (A) IF assay showed that ZDHHC9 knockout (KO) substantially decreased Vangl2 membrane localization in MCF10A cells. The cells were stained with anti-E-Cadherin antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) Quantification of the colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and E-Cadherin. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (C) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 and GM130 in the indicated MCF10A cells. Cells were stained with anti-GM130 antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (D) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and GM130 was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (E) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 and Calnexin in the indicated MCF10A cells. Cells were stained with anti-Calnexin antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (F) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and Calnexin was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (G) IF assay showed that blocking Vangl2 stearoylation with 30 µM of 2-BP disrupted Vangl2 membrane localization in MCF10A cells. The cells were stained with anti-E-Cadherin antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (H) Quantification of the colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and E-Cadherin. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (I) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 and GM130 in MCF10A cells with 2-BP treatment. Cells were stained with anti-GM130 antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (J) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and GM130 was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (K) IF assay showed the colocalization of Vangl2 and Calnexin in MCF10A cells with 2-BP treatment. Cells were stained with anti-Calnexin antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) (L) The colocalization ratio between Vangl2 and Calnexin was quantified. At least 200 cells were counted for each cell line. (M) IF assay showed Golgi orientation in the wound edge cells using MCF10A stable cells with ZDHHC9 KO or 2-BP treatment at 20 h postscratch. Cells were stained with anti-GM130 antibody (red), anti-Flag antibody (green), and DAPI (blue). The dotted line indicates the wound edge. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (N) Quantification of the percentage of the normal-oriented cells at the wound edge. At least 400 cells were counted for each cell line. All data are represented as mean ± SEM, n > 3. P values were determined using two-tailed t tests. ***P < 0.001.

We next asked whether ZDHHC9 could regulate PCP establishment during cell migration. In the wound-induced cell polarization assay, our IF results revealed that the Golgi displayed more randomly localized in the ZDHHC9 KO or 2-BP-treated MCF10A cells compared with that of control cells at the wound edge (Fig. 4M). Quantification results showed that about 48% of the control cells at the wound edge were normal-oriented, while the ratio was 31% in the ZDHHC9 KO cells and 28% in the 2-BP treated cells (Fig. 4N). Taken together, these results indicated that ZDHHC9 plays an important role in Vangl2 membrane localization and PCP establishment during cell migration.

Loss of Vangl2 Stearoylation Promotes the Activation of YAP, AKT, and ERK Signaling.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis and previous studies revealed that Vangl2 is frequently up-regulated and mislocalized in breast cancer (SI Appendix, Figs. S19 and S20) (24, 27). However, the mechanism of Vangl2 mislocalization in breast cancer is not clear. The Vangl2 destearoylase APT1 is often amplified in breast cancers (SI Appendix, Figs. S21 and S22), which may lead to destearoylation and mislocalization of Vangl2. In addition, cBioPortal database showed that several Vangl2 missense mutations are close to its stearoylation site, including A92T, V99I, and L101Q. Our mutagenesis and stearoylation analysis showed that these mutations reduced the stearoylation level of Vangl2, with L101Q as the most potent one (SI Appendix, Fig. S23), indicating that missense mutations may result in stearoylation decrease and mislocalization of Vangl2. HCC1806 is a commonly used human triple negative breast cancer cell line, which is a highly heterogeneous and aggressive breast cancer subtype. According to the cancer gene expression database (BioGPS, E-GEOD-15026) and previous studies (24), Vangl2 is highly expressed and mislocalized in HCC1806 cells. To investigate the roles of Vangl2 stearoylation in breast cancer, we have generated HCC1806 stable cell lines expressing vector control, Flag-Vangl2 WT, or the C103S mutant. Western blot showed that the expression levels of Vangl2 WT and the C103S mutant were comparable in the stable cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S24).

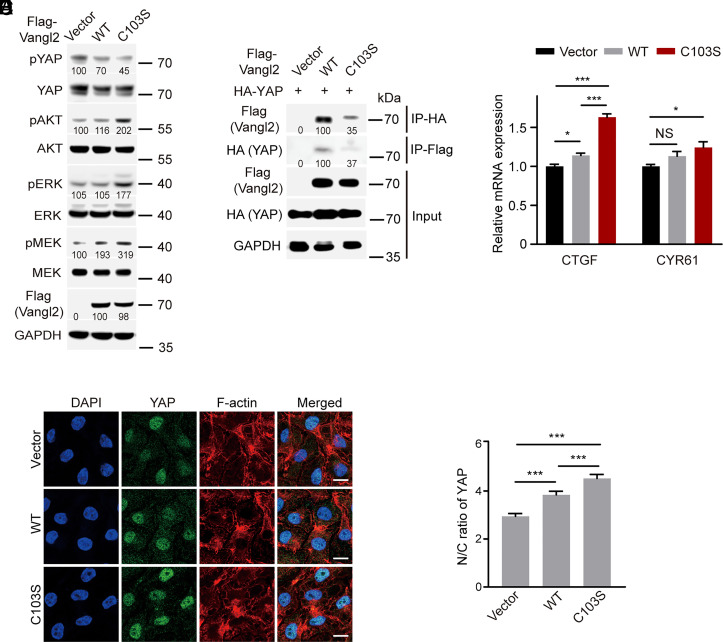

The Hippo pathway effectors YAP/TAZ have been characterized as downstream effectors of PCP signaling in mediating cell migration (55). In addition, the cell polarity protein Scribble functions as a regulator of the YAP pathway and mislocalization of Scribble activates YAP signaling (56–58). Previous studies showed that Vangl2 could interact with Scribble and serve as the docking site for Scribble (5, 29, 30, 59). We speculated that stearoylation of Vangl2 may play a regulatory role in YAP signaling. Indeed, our western blot results showed that YAP (Ser127) phosphorylation (pYAP, inactive form) was substantially decreased in the Vangl2 C103S mutant cells compared with vector control cells, while pYAP was only modestly decreased in Vangl2 WT cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, our co-IP results showed the interaction between Vangl2 C103S and YAP was substantially decreased compared with that of Vangl2 WT (Fig. 5B). To further analyze the role of Vangl2 stearoylation in YAP signaling, we performed RT-PCR assay to evaluate expression of YAP target genes CTGF and CYR61 in the HCC1806 stable cells. The results showed that expression of Vangl2 C103S significantly increased expression of CTGF and CYR61, while Vangl2 WT showed modest effect (Fig. 5C). As YAP nuclear translocation is required for the activation of YAP signaling, we performed IF assay to analyze YAP localization in the HCC1806 stable cells. The results revealed that expression of the Vangl2 C103S increased YAP nuclear localization compared with Vangl2 WT or vector control cells (Fig. 5D). Quantification analysis confirmed the increase of YAP nuclear/cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio in Vangl2 C103S cells (Fig. 5E). Because YAP nuclear localization could be regulated by cell density, we assessed YAP N/C ratio at high and low cell density using HCC1806 stable cells. Our IF results showed that YAP N/C ratio significantly increased in Vangl2 C103S cells compared with Vangl2 WT cells at both high and low cell density (SI Appendix, Fig. S25). Together, our results suggested that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation may decrease YAP phosphorylation and increase YAP nuclear translocation and target gene expression.

Fig. 5.

Loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promotes the activation of YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling. (A) Western blot showed that phosphorylation level of YAP, AKT, ERK, and MEK in the indicated HCC1806 stable cells. Relative Vangl2 protein level and phosphorylation level of YAP, AKT, ERK, and MEK are indicated. (B) Co-IP showed the interaction between Vangl2 and YAP in HCC1806 cells. Relative Vangl2 and YAP protein levels are indicated from the co-IP samples. (C) RT-PCR showed YAP target gene expression in the indicated HCC1806 stable cells. Relative mRNA expression was normalized to vector control. (D) IF assay showed YAP localization in HCC1806 cells. The cells were stained with anti-YAP antibody (green), TRITC phalloidin for F-actin (red), and DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (E) Quantification of YAP nuclear/cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio. At least 100 cells were counted for each cell line. All data are represented as mean ± SEM, n > 3. P values were determined using two-tailed t tests. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

GIPC1 has been identified as a binding partner of Vangl2 and participates in PI3K/AKT signaling activation (60–62). A recent study reported that GIPC1 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation and migration through activating PI3K/AKT (63). We then asked whether stearoylation of Vangl2 could regulate PI3K/AKT signaling. Surprisingly, our western blot showed that expression of Vangl2 C103S, but not Vangl2 WT, substantially increased AKT phosphorylation in HCC1806 cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, co-IP results revealed that the interaction between Vangl2 C103S and GIPC1 was substantially increased compared with that of Vangl2 WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S26). Our results suggested that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation may enhance the activation of PI3K/AKT signaling, possibly due to the increased interaction between Vangl2 and GIPC1.

Vangl2 knockdown has been shown to inhibit phosphorylation of MAPK signaling molecule ERK (64). In addition, Scribble, a binding partner of Vangl2, can modulate MAPK signaling (30, 59, 65–67). Mislocalization of Scribble has been found to activate MAPK signaling and promote tumorigenesis (32, 58). We wondered whether stearoylation of Vangl2 could affect MAPK signaling. Our western blot showed that expression of Vangl2 C103S substantially increased phosphorylation of ERK and MEK in HCC1806 cells, while expression of Vangl2 WT only showed modest effect (Fig. 5A). We speculate that the reduced membrane localization of Vangl2 C103S might induce Scribble mislocalization and thereby ERK activation.

ER stress has been shown to activate AKT and ERK signaling (68). We wondered whether Vangl2 C103S could induce ER stress, thereby activating AKT and ERK. We performed RT-PCR and western blot assays to examine the ER stress markers (BiP, CHOP, XBP1, and phosphorylated eIF2α) in the HCC1806 stable cells with or without the ER stress inducer thapsigargin (Tg) treatment. Our results showed that the overall ER stress markers were not significantly elevated in Vangl2 C103S cells compared with Vangl2 WT or vector control cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S27). However, we observed that the ER stress markers were slightly elevated upon Tg treatment in the RT-PCR results and the protein levels of BiP and CHOP were modestly increased in Vangl2 C103S cells compared with vector control cells. Our colocalization analysis showed that Vangl2 C103S was partially trapped in the ER. Thus, the ER-trapped Vangl2 C103S may induce the modest increase of ER stress, which may partially contribute to the activation of AKT and ERK. Taken together, our results suggested that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promotes the activation of YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling, probably due to Vangl2 mislocalization.

Loss of Vangl2 Stearoylation Enhances Breast Cancer Cell Growth and HRasV12-Induced Oncogenic Transformation.

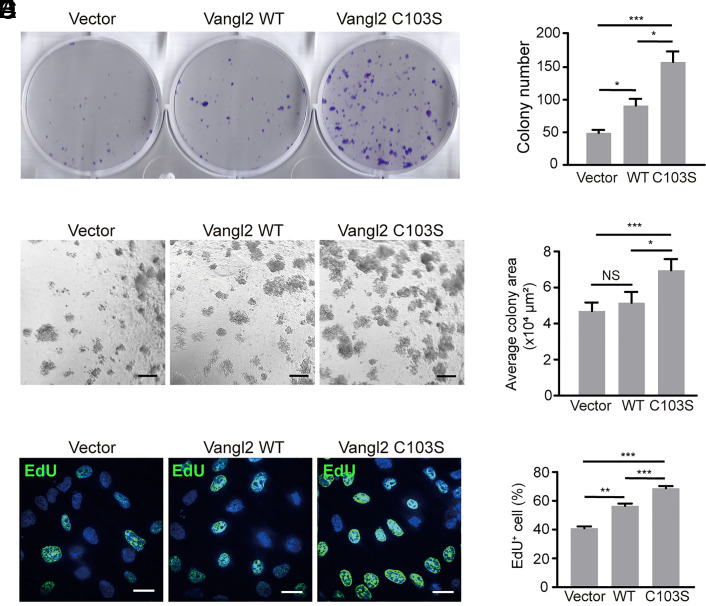

Dysregulation of Vangl2 has been associated with cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (24–28). We found that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation enhances the activation of YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling in breast cancer cells. Then we asked whether stearoylation of Vangl2 could regulate breast cancer cell growth using the HCC1806 stable cells. Colony formation assay is a method to measure the ability of single cells to grow into colonies. Our results showed that expression of Vangl2 C103S significantly increased HCC1806 colony numbers compared with that of Vangl2 WT or vector control (Fig. 6 A and B). Sphere formation assay is commonly used to evaluate the malignant properties and stemness of tumor cells. We found that expression of Vangl2 C103S, but not Vangl2 WT, significantly enhanced sphere formation of HCC1806 cells under 3D culture conditions (Fig. 6 C and D). EdU assay combines EdU (5-ethynyl 2′-deoxyuridine) labeling with click chemistry to detect newly synthesized DNA. Our EdU assay showed that expression of Vangl2 C103S significantly increased EdU-positive cells compared with that of Vangl2 WT or vector control (Fig. 6 E and F). Together, these results suggested that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promotes breast cancer cell growth.

Fig. 6.

Loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promotes breast cancer cell growth. (A) Colony formation assay using the indicated HCC1806 stable cells. (B) Quantification of the colony number in the indicated HCC1806 stable cell lines. (C) Representative images of HCC1806 stable cells cultured under 3D conditions for 6 d. (Scale bar,100 μm.) (D) Quantification of the average area of the acini in the indicated stable cell line. At least 100 acini were analyzed for each cell line in three independent experiments. (E) Representative images of HCC1806 cells in the EdU assay. (F) Quantification of cell proliferation index by calculating the EdU positive (EdU+) cells in the indicated HCC1806 cells. All data are represented as mean ± SEM, n > 3. P values were determined using two-tailed t tests. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

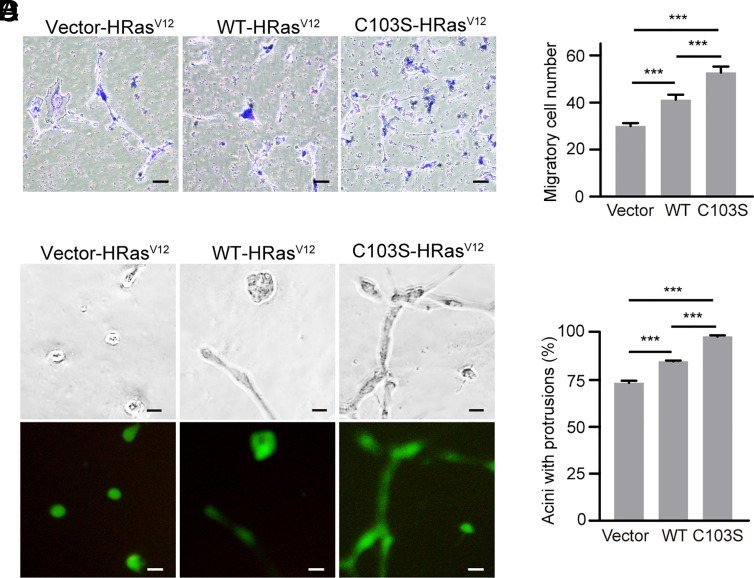

To investigate whether stearoylation of Vangl2 could affect cell migration and invasion, we generated MCF10A stable cells expressing oncogenic HRasV12 and Vangl2 WT or the C103S mutant. Western blot results showed that the expression levels of HRasV12 were comparable in the stable cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S28). The morphology of MCF10A stable cells displayed no obvious change under monolayer culture conditions. Transwell assay is widely used to evaluate cell migration and invasion in vitro. Our transwell assay revealed that expression of Vangl2 C103S significantly enhanced the migration ability of MCF10A cells compared with that of Vangl2 WT or vector control (Fig. 7 A and B). Then we performed Matrigel-based 3D invasion assay to study the roles of Vangl2 stearoylation in cell invasion. A significant increase of invasive protrusions was observed in the acini expressing Vangl2 C103S compared with that of Vangl2 WT or the vector control (Fig. 7 C and D). GFP-positive cells indicated that the HRasV12 is expressed in the acini. Together, our results indicate that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promotes breast cancer cell growth and HRasV12-induced oncogenic transformation, possibly through activation of YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling.

Fig. 7.

Loss of Vangl2 stearoylation enhances HRasV12-induced oncogenic transformation. (A) Transwell migration assay showing the migratory response in the indicated MCF10A stable cell lines. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (B) Quantification of the number of migratory cells in the indicated MCF10A stable cell lines. (C) Representative images of the indicated MCF10A stable cells cultured in Matrigel for 4 d. (Scale bar, 25 μm.) (D) Quantification of the percentage of acini with invasive protrusions in the indicated MCF10A cell lines. At least 100 acini were analyzed for each cell line in three independent experiments. All data are represented as mean ± SEM, n > 3. P values were determined using two-tailed t tests. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Long-chain fatty acylation of protein plays an important role in protein trafficking and subcellular localization (33–36). Using bioorthogonal chemical reporters of protein fatty acylation, we identify that the PCP core component Vangl2 is stearoylated at a highly conserved cysteine residue within the N-terminal domain (Fig. 1). S-fatty acylation has been documented as a reversible and dynamic protein posttranslational modification (33, 69, 70). Indeed, we found that Vangl2 undergoes cycles of stearoylation and destearoylation with a half-life of about 1.8 h (Fig. 1 H and I). Both ZDHHC9 and ZDHHC11 could enhance Vangl2 stearoylation, but the interaction between ZDHHC11 and Vangl2 was much weaker than that of ZDHHC9 and Vangl2 (Fig. 2B), indicating that ZDHHC9 is the primary stearoylase of Vangl2. Our results and the previous study showed that ZDHHC9 is localized in both the Golgi and the ER (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (47), suggesting that Vangl2 stearoylation may take place in the Golgi and the ER. APT1 and APT2 are known thioesterases regulating the protein deacylation (71, 72). APT1 substantially decreased Vangl2 stearoylation, while APT2 had a minor effect (Fig. 2H). In addition, the interaction between APT1 and Vangl2 was much stronger than that of APT2 and Vangl2 (Fig. 2I), indicating that APT1 is the major destearoylase of Vangl2. APT1 could localize to the plasma membrane (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) (48) and colocalize with Vangl2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), suggesting that Vangl2 might be destearoylated at the plasma membrane.

Our results suggested that stearoylation of Vangl2 is required for its membrane localization. The stearoylation-deficient mutant of Vangl2 (C103S) was mislocalized to puncta within the cytoplasm (Fig. 3 A and B), possibly resulted from the disruption of Vangl2 trafficking. Our colocalization analysis revealed that Vangl2 C103S was trapped in the Golgi and the ER under 2D and 3D conditions (Fig. 3 C–J). Sec24b has been shown to selectively sort Vangl2 into the COPII vesicles for trafficking (16). Interestingly, the Vangl2 S464N mutant, failing to be sorted into COPII vesicles, showed lower stearoylation level compared with that of Vangl2 WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). In addition, the interaction between Sec24b and Vangl2 C103S was decreased compared with that of Vangl2 WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), suggesting that stearoylation may be required for Vangl2 sorting into COPII vesicles. Thus, it is possible that the newly synthesized Vangl2 may be stearoylated by ZDHHC9 in the ER and the Golgi and thereby facilitate its delivery to the cell surface through a pathway involving Sec24b, while APT1 might destearoylate membrane-localized Vangl2 and promote its recycling from the plasma membrane. The stearoylation-deficient mutant of Vangl2 may be delivered to the Golgi in a lower efficiency or another pathway, but it may be trapped in the Golgi or sent back to the ER due to stearoylation loss. Besides Golgi and ER, the stearoylation-deficient mutant of Vangl2 might be stuck in other puncta structures, which needs further study. More importantly, Vangl2 stearoylation plays an important regulatory role in PCP establishment during cell migration (Fig. 3 L and M). Genetically or pharmacologically inhibiting ZDHHC9 phenocopied the effects of Vangl2 stearoylation loss (Fig. 4), suggesting that ZDHHC9 may regulate PCP signaling by mediating Vangl2 stearoylation. Dysfunction of ZDHHC9 has been associated with X-linked intellectual disability (XLID) and high epilepsy risk (73), and Vangl2 has been found to be crucial for the formation and maintenance of synapses (74, 75). Therefore, ZDHHC9-mediated stearoylation of Vangl2 may play an important role in neurological disorders.

Vangl2 may act as a tumor suppressor by attenuating canonical Wnt signaling (19, 20, 22). Paradoxically, upregulation of Vangl2 has been shown to promote tumor growth and progression (24–28, 31). Our results revealed that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation enhances the activation of oncogenic YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling (Fig. 5), possibly due to mislocalization of Vangl2. YAP activation has been shown to play a crucial role in breast cancer development (76). We found that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation led to YAP phosphorylation decrease, YAP nuclear translocation, and target gene expression in breast cancer cells. It is possible that the stearoylated Vangl2 localizes to the plasma membrane and facilitates YAP phosphorylation, while the stearoylation-deficient mutant of Vangl2 is mislocalized and leads to YAP phosphorylation decrease and nuclear translocation. The Vangl2 binding partner GIPC1 has been shown to activate AKT signaling and promote tumorigenesis (60–63). We found that the interaction between Vangl2 C103S and GIPC1 was substantially increased compared with that of Vangl2 WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S26), probably due to Vangl2 mislocalization. Therefore, AKT activation induced by Vangl2 C103S may be from the increased interaction between Vangl2 C103S and GIPC1. Membrane-localized Vangl2 has been found to serve as the docking site for Scribble and mislocalization of Scribble activates ERK signaling and drives tumorigenesis (30, 32, 58, 59). The reduced membrane localization of Vangl2 C103S might induce Scribble mislocalization and thereby ERK activation. In addition, ER stress has been shown to activate AKT and ERK signaling (68). Although the overall ER stress was not dramatically elevated in Vangl2 C103S overexpression cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S27), we observed modest increase of ER stress possibly induced by the ER-trapped Vangl2 C103S, which might partially contribute to AKT and ERK activation. Consistent with the activation of YAP, AKT and ERK, our cell proliferation assay showed that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation promotes breast cancer cell growth (Fig. 6). Moreover, loss of Vangl2 stearoylation enhanced oncogenic HRASV12-induced breast cell migration and invasion (Fig. 7). These results suggested that loss of Vangl2 stearoylation may lead to breast cancer growth and progression by inducing Vangl2 mislocalization. Notably, the Vangl2 destearoylase APT1 is often up-regulated in breast cancers (SI Appendix, Figs. S21 and S22), which may decrease Vangl2 stearoylation level and activate YAP, AKT, and ERK signaling, thereby contributing to breast cancer progression. Thus, APT1 could be a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer with Vangl2 mislocalization. In addition, Vangl2 missense mutations may reduce its stearoylation level (SI Appendix, Fig. S23), leading to Vangl2 mislocalization and thereby contributing to tumorigenesis and other disorders.

In summary, our work reveals that ZDHHC9-APT1-mediated stearoylation cycle of Vangl2 plays an important regulatory role in Vangl2 subcellular localization, PCP establishment during cell migration and tumorigenesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S29). Deregulation of fatty acid metabolism might affect stearoylation level of Vangl2 and its localization, thereby resulting in PCP defects, neurological disorders, and cancers.

Materials and Methods

Cell Labeling, Click Reaction and Detection.

Cells were washed once with PBS and cultured in prewarmed fresh medium containing probes or DMSO for overnight. Then the cells were washed three times with cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM TEA-HCl, pH7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, phosphatase inhibitor, and 1x EDTA-free cOmplete protease inhibitor. Click reaction was performed in reaction buffer containing 100 μL protein, 100 μM biotin-azide, 1 mM TCEP, 100 μM tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl) methy-l] amine (TBTA) and 1 mM CuSO4 for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by adding sample-loading buffer. The samples were heated for 5 min at 95 °C before being subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. For hydroxylamine treatment assay, 2.5% (v/v) hydroxylamine was added to the sample before adding the sample-loading buffer. The streptavidin beads were used to enrich the labeled proteins from the click reaction products. The bound-proteins were washed three times with wash buffer (0.2% SDS, Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA) and eluted with sample-loading buffer, boiling for 5 min at 95 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, and subjected to western blotting.

An extended section is provided in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22177101). We thank Dr. Masaki Fukata (National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Japan) for the expression vectors of ABHD proteins. We are grateful to our colleagues at the core facility of the Life Sciences Institute for assistance with proteomic studies, molecular, and cell imaging analysis.

Author contributions

B.C. designed research; J.Y., Y.Y., X.Z., and Z.D. performed research; J.Y., Y.Y., X.Z., Z.D., and B.C. analyzed data; and B.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Zallen J. A., Planar polarity and tissue morphogenesis. Cell 129, 1051–1063 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler M. T., Wallingford J. B., Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 375–388 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torban E., Sokol S. Y., Planar cell polarity pathway in kidney development, function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 17, 369–385 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luga V., et al. , Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell 151, 1542–1556 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montcouquiol M., et al. , Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature 423, 173–177 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iliescu A., Gravel M., Horth C., Apuzzo S., Gros P., Transmembrane topology of mammalian planar cell polarity protein Vangl1. Biochemistry 50, 2274–2282 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strutt H., Warrington S. J., Strutt D., Dynamics of core planar polarity protein turnover and stable assembly into discrete membrane subdomains. Dev. Cell 20, 511–525 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailly E., Walton A., Borg J. P., The planar cell polarity Vangl2 protein: From genetics to cellular and molecular functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 81, 62–70 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell I. J., Horn M. S., Van Raay T. J., Bridging the gap between non-canonical and canonical Wnt signaling through Vangl2. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 125, 37–44 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao B., et al. , Wnt signaling gradients establish planar cell polarity by inducing Vangl2 phosphorylation through Ror2. Dev. Cell 20, 163–176 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng D., et al. , Regulation of Wnt/PCP signaling through p97/VCP-KBTBD7-mediated Vangl ubiquitination and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg2099 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu Z., et al. , VANGL2 inhibits antiviral IFN-I signaling by targeting TBK1 for autophagic degradation. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg2339 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong Y., et al. , Vangl2 limits chaperone-mediated autophagy to balance osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. Dev. Cell 56, 2103–2120.e9 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kibar Z., et al. , Ltap, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila Strabismus/Van Gogh, is altered in the mouse neural tube mutant Loop-tail. Nat. Genet. 28, 251–255 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei Y. P., et al. , VANGL2 mutations in human cranial neural-tube defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 2232–2235 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merte J., et al. , Sec24b selectively sorts Vangl2 to regulate planar cell polarity during neural tube closure. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 41–46; sup pp 1–8 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iliescu A., Gravel M., Horth C., Kibar Z., Gros P., Loss of membrane targeting of Vangl proteins causes neural tube defects. Biochemistry 50, 795–804 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin H., Copley C. O., Goodrich L. V., Deans M. R., Comparison of phenotypes between different vangl2 mutants demonstrates dominant effects of the Looptail mutation during hair cell development. PLoS one 7, e31988 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park M., Moon R. T., The planar cell-polarity gene stbm regulates cell behaviour and cell fate in vertebrate embryos. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 20–25 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piazzi G., et al. , Van-Gogh-like 2 antagonises the canonical WNT pathway and is methylated in colorectal cancers. Br. J. Cancer 108, 1750–1756 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyberg C., et al. , Planar cell polarity gene expression correlates with tumor cell viability and prognostic outcome in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer 16, 259 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Z., Zheng L., Li S., Paclitaxel-induced inhibition of NSCLC invasion and migration via RBFOX3-mediated circIGF1R biogenesis. Sci. Rep. 14, 774 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatakeyama J., Wald J. H., Printsev I., Ho H. Y., Carraway K. L. III, Vangl1 and Vangl2: Planar cell polarity components with a developing role in cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 21, R345–R356 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puvirajesinghe T. M., et al. , Identification of p62/SQSTM1 as a component of non-canonical Wnt VANGL2-JNK signalling in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 7, 10318 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes M. N., et al. , Vangl2/RhoA signaling pathway regulates stem cell self-renewal programs and growth in Rhabdomyosarcoma. Cell Stem. Cell 22, 414–427.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daulat A. M., Borg J. P., Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling: New opportunities for cancer treatment. Trends Cancer 3, 113–125 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderVorst K., Hatakeyama J., Berg A., Lee H., Carraway K. L., 3rd Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying planar cell polarity pathway contributions to cancer malignancy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 81, 78–87 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VanderVorst K., et al. , Vangl-dependent Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling mediates collective breast carcinoma motility and distant metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 25, 52 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anastas J. N., et al. , A protein complex of SCRIB, NOS1AP and VANGL1 regulates cell polarity and migration, and is associated with breast cancer progression. Oncogene 31, 3696–3708 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.How J. Y., Stephens R. K., Lim K. Y. B., Humbert P. O., Kvansakul M., Structural basis of the human Scribble-Vangl2 association in health and disease. Biochem. J. 478, 1321–1332 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voutsadakis I. A., Molecular alterations and putative therapeutic targeting of planar cell polarity proteins in breast cancer. J. Clin. Med. 12, 411 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feigin M. E., et al. , Mislocalization of the cell polarity protein scribble promotes mammary tumorigenesis and is associated with Basal breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 3180–3194 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linder M. E., Deschenes R. J., Palmitoylation: Policing protein stability and traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 74–84 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Resh M. D., Fatty acylation of proteins: The long and the short of it. Progress Lipid Res. 63, 123–131 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang H., et al. , Protein lipidation: Occurrence, mechanisms, biological functions, and enabling technologies. Chem. Rev. 118, 919–988 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen B., Sun Y., Niu J., Jarugumilli G. K., Wu X., Protein lipidation in cell signaling and diseases: Function, regulation, and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 817–831 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z., et al. , Small-molecule modulation of protein lipidation: From chemical probes to therapeutics. Chembiochem 24, e202300071 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin B. R., Cravatt B. F., Large-scale profiling of protein palmitoylation in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods 6, 135–138 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thinon E., Fernandez J. P., Molina H., Hang H. C., Selective enrichment and direct analysis of protein S-palmitoylation sites. J. Proteome Res. 17, 1907–1922 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang R., et al. , Neural palmitoyl-proteomics reveals dynamic synaptic palmitoylation. Nature 456, 904–909 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y., Martin B. R., Cravatt B. F., Hofmann S. L., DHHC5 protein palmitoylates flotillin-2 and is rapidly degraded on induction of neuronal differentiation in cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 523–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciruna B., Jenny A., Lee D., Mlodzik M., Schier A. F., Planar cell polarity signalling couples cell division and morphogenesis during neurulation. Nature 439, 220–224 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borovina A., Superina S., Voskas D., Ciruna B., Vangl2 directs the posterior tilting and asymmetric localization of motile primary cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 407–412 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Percher A., et al. , Mass-tag labeling reveals site-specific and endogenous levels of protein S-fatty acylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 4302–4307 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin D. T., Conibear E., ABHD17 proteins are novel protein depalmitoylases that regulate N-Ras palmitate turnover and subcellular localization. eLife 4, e11306 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yokoi N., et al. , Identification of PSD-95 depalmitoylating enzymes. J. Neurosci. 36, 6431–6444 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohno Y., Kihara A., Sano T., Igarashi Y., Intracellular localization and tissue-specific distribution of human and yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain-containing proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 474–483 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirano T., et al. , Thioesterase activity and subcellular localization of acylprotein thioesterase 1/lysophospholipase 1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 797–805 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poobalasingam T., et al. , Heterozygous Vangl2Looptail mice reveal novel roles for the planar cell polarity pathway in adult lung homeostasis and repair. Dis. Models Mech. 10, 409–423 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheong S. S., et al. , The planar polarity component VANGL2 Is a key regulator of mechanosignaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 577201 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A., Integrin-mediated activation of Cdc42 controls cell polarity in migrating astrocytes through PKCzeta. Cell 106, 489–498 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips H. M., Murdoch J. N., Chaudhry B., Copp A. J., Henderson D. J., Vangl2 acts via RhoA signaling to regulate polarized cell movements during development of the proximal outflow tract. Circ. Res. 96, 292–299 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brasch M. E., et al. , Nuclear position relative to the Golgi body and nuclear orientation are differentially responsive indicators of cell polarized motility. PloS one 14, e0211408 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ravichandran Y., Goud B., Manneville J. B., The Golgi apparatus and cell polarity: Roles of the cytoskeleton, the Golgi matrix, and Golgi membranes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 62, 104–113 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park H. W., et al. , Alternative Wnt signaling activates YAP/TAZ. Cell 162, 780–794 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohseni M., et al. , A genetic screen identifies an LKB1-MARK signalling axis controlling the Hippo-YAP pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 108–117 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen B., et al. , ZDHHC7-mediated S-palmitoylation of Scribble regulates cell polarity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 686–693 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adachi Y., et al. , Scribble mis-localization induces adaptive resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitors through feedback activation of MAPK signaling mediated by YAP-induced MRAS. Nat. Cancer 4, 829–843 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kallay L. M., McNickle A., Brennwald P. J., Hubbard A. L., Braiterman L. T., Scribble associates with two polarity proteins, Lgl2 and Vangl2, via distinct molecular domains. J. Cell. Biochem. 99, 647–664 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giese A. P., et al. , Gipc1 has a dual role in Vangl2 trafficking and hair bundle integrity in the inner ear. Development 139, 3775–3785 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katoh M., Functional proteomics, human genetics and cancer biology of GIPC family members. Exp. Mol. Med. 45, e26 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.La Torre A., Hoshino A., Cavanaugh C., Ware C. B., Reh T. A., The GIPC1-Akt1 pathway is required for the specification of the eye field in mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem. cells 33, 2674–2685 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li T., et al. , GIPC1 promotes tumor growth and migration in gastric cancer via activating PDGFR/PI3K/AKT signaling. Oncol. Res. 32, 361–371 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang K., et al. , Silencing of Vangl2 attenuates the inflammation promoted by Wnt5a via MAPK and NF-kappaB pathway in chondrocytes. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 16, 136 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dow L. E., et al. , Loss of human Scribble cooperates with H-Ras to promote cell invasion through deregulation of MAPK signalling. Oncogene 27, 5988–6001 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elsum I. A., Martin C., Humbert P. O., Scribble regulates an EMT polarity pathway through modulation of MAPK-ERK signaling to mediate junction formation. J. Cell Sci. 126, 3990–3999 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Godde N. J., et al. , Scribble modulates the MAPK/Fra1 pathway to disrupt luminal and ductal integrity and suppress tumour formation in the mammary gland. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004323 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu P., Han Z., Couvillon A. D., Exton J. H., Critical role of endogenous Akt/IAPs and MEK1/ERK pathways in counteracting endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49420–49429 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fukata Y., Fukata M., Protein palmitoylation in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 161–175 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rocks O., et al. , The palmitoylation machinery is a spatially organizing system for peripheral membrane proteins. Cell 141, 458–471 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rocks O., et al. , An acylation cycle regulates localization and activity of palmitoylated Ras isoforms. Science 307, 1746–1752 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dekker F. J., et al. , Small-molecule inhibition of APT1 affects Ras localization and signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 449–456 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shimell J. J., et al. , The X-linked intellectual disability gene Zdhhc9 is essential for dendrite outgrowth and inhibitory synapse formation. Cell Rep. 29, 2422–2437.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thakar S., et al. , Evidence for opposing roles of Celsr3 and Vangl2 in glutamatergic synapse formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E610–E618 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feng B., et al. , Planar cell polarity signaling components are a direct target of beta-amyloid-associated degeneration of glutamatergic synapses. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh2307 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Franklin J. M., Wu Z., Guan K. L., Insights into recent findings and clinical application of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 23, 512–525 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.