Abstract

The RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) consists of conserved heptapeptide repeats that can be phosphorylated to influence distinct stages of the transcription cycle, including RNA processing. Although CTD-associated proteins have been identified, phospho-dependent CTD interactions have remained elusive. Proximity-dependent biotinylation (PDB) has recently emerged as an alternative approach to identify protein-protein associations in the native cellular environment. In this study, we present a PDB-based map of the fission yeast RNAPII CTD interactome in living cells and identify phospho-dependent CTD interactions by using a mutant in which Ser2 was replaced by alanine in every repeat of the fission yeast CTD. This approach revealed that CTD Ser2 phosphorylation is critical for the association between RNAPII and the histone methyltransferase Set2 during transcription elongation, but is not required for 3′ end processing and transcription termination. Accordingly, loss of CTD Ser2 phosphorylation causes a global increase in antisense transcription, correlating with elevated histone acetylation in gene bodies. Our findings reveal that the fundamental role of CTD Ser2 phosphorylation is to establish a chromatin-based repressive state that prevents cryptic intragenic transcription initiation.

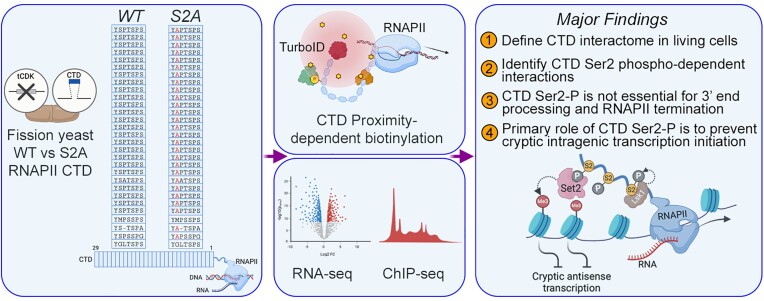

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Eukaryotic species use at least three specialized RNA Polymerases (RNAPI, II and III) that generally transcribe ribosomal, messenger, and transfer RNA genes, respectively. RNAPII is responsible for the transcription of the broadest and most diverse group of genes, including messenger RNAs (mRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), as well as a variety of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). RNAPII is also unique among the eukaryotic RNA polymerases in that its largest catalytic subunit contains a low-complexity and disordered C-terminal domain (CTD), consisting of repetitions of a conserved heptapeptide consensus sequence, Y1-S2-P3-T4-S5-P6-S7 (1,2). Interestingly, the total number of heptad repeats generally increases in species with increasing levels of evolutionary complexity, such that S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, Arabidopsis, Drosophila and humans have 26, 29, 39, 42 and 52 repeats, respectively (1,2). Although the complete absence of CTD heptad repeats results in cell inviability, most organisms can survive with truncated versions of their CTD. For instance, 8 (out of 26) repeats are essential in S. cerevisiae (3), 10 (out of 29) in S. pombe (4) and 22–26 (out of 52) in human cells (5,6).

Of the seven residues of the CTD consensus sequence, five (Y1, S2, T4, S5 and S7) have been shown to be phosphorylated in a variety of model organisms (1,2). The most extensively studied CTD post-translational modifications have been the phosphorylation of S2 and S5 (S2P and S5P), which are the most prevalent CTD modifications in yeast and human cells (7,8). While the CTD can be modified in many additional ways on other residues, an anticorrelated gradient of S5 and S2 phosphorylation events is the most conserved and best characterized mark during the RNAPII transcription cycle: levels of S5P peak during the transition from initiation to early elongation, whereas S2P increases during productive elongation and reaches maximum levels near the polyadenylation signal (PAS) (1,2,9). Several kinases have been implicated in S2 phosphorylation during elongation of RNAPII transcription, including the budding yeast cyclin-dependent kinases Ctk1 (10) and its orthologs Lsk1 and CDK12, which are responsible for the bulk of S2P in S. pombe and metazoans, respectively (11,12).

The progressive accumulation of CTD S2P during transcription elongation led to the postulation that S2P could play a role in co-transcriptional 3′ end processing of nascent transcript. Evidence indeed support the view that S2P promotes the co-transcriptional recruitment of factors involved in mRNA 3′ end processing. First, the 3′ end processing factor Pcf11, which is highly concentrated at the 3′ end of genes, contains a CTD-interaction domain (CID) (13–15) that preferentially associates with S2-phosphorylated CTD peptides in vitro (16) and that is essential for viability (17). A deficiency of the CTD S2 kinase also impairs co-transcriptional recruitment of specific 3′ end processing factors at the 3′ end of specific genes (18,19). The ectopic expression of Rpb1 variants in which S2 was replaced by a non-phosphorylable residue in CTD heptad repeats results in the production of read-through transcripts expressed from model genes as well as show reduced co-transcriptional recruitment of 3′ end processing factors at the 3′ end of genes (20–22).

Yet, despite evidence linking S2 phosphorylation with mRNA 3′ end processing, data also support the notion that S2P is not required for cleavage and polyadenylation of pre-mRNAs. First, the function of the mRNA 3′ end processing machinery does not require RNAPII-dependent transcription. Specifically, PAS-dependent cleavage and polyadenylation of a nascent transcript by the 3′ end processing machinery occurs in yeast when a gene is transcribed by the phage T7 RNA polymerase, which lacks a CTD (23). Second, deletion of the major CTD S2 kinase in S. cerevisiae (Ctk1) results in read-through transcripts for only 3% of protein-coding genes (24). Third, structural analysis of the Pcf11-CID indicates that it does not make direct contact with the S2-phosphate group (14,15). Finally, whereas most 3′ end processing factors are essential for cell viability, full length phospho-deficient Rpb1 derivatives in which S2 was replaced by alanine (S2A) in every repeat of the CTD confer full viability in both fission and budding yeasts (12,20,24,25); this suggests that the S2P mark, but not 3′ end processing factors, is dispensable for growth.

The phosphorylation state of the RNAPII CTD also contributes to the recruitment and regulation of chromatin remodelling factors, including histone modifiers. The SET domain-containing protein 2 (Set2) is an evolutionarily conserved lysine methyltransferase (MTase) that copurifies with RNAPII and catalyzes mono-, di- and tri-methylation (me, me2 and me3) of lysine 36 on histone H3 (H3K36) (26–29). Set2-dependent H3K36me2/me3 is primarily found in gene bodies where it prevents cryptic transcription initiation via the activation of the conserved Rpd3S/Clr6(II) histone deacetylase complex (30–33), thereby maintaining the coding regions of genes in a hypoacetylated state. Accordingly, inactivation of Set2 or components of the Rpd3S/Clr6(II) complex leads to the accumulation of antisense noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) that initiate within protein-coding genes (33,34). The C-terminal end of Set2 includes a Set2–Rpb1 interaction (SRI) domain that is necessary and sufficient for binding the CTD (35). Structural analysis of the yeast and human Set2 SRI domain revealed that it preferentially recognizes CTD di-heptad repeats that are phosphorylated on S2 and S5 residues (36,37). Interestingly, although the SRI is required for the copurification of Set2 with RNAPII, the SRI domain is dispensable for crosslinking of Set2 to chromatin (38–40). Furthermore, the expression of the SET catalytic domain alone, which lacks the CTD-interacting SRI domain, is sufficient to promote H3K36me2 and suppress the use of cryptic promoters in a S. cerevisiae mutant of SET2 (38,41–43). Thus, the significance of the Set2-CTD interaction in Set2-dependent repression of cryptic intragenic transcription remains elusive.

Given the importance of understanding the significance underlying the transcriptional dynamics of RNAPII CTD phosphorylation, several studies have investigated for phospho-specific CTD interactions using a variety of approaches, including genetic screens (44), the yeast two-hybrid system (45), pull-down assays using recombinant CTD or CTD peptides (13,46–49), as well as affinity purifications approaches (50–52). However, purification assays primarily detect strong and stable protein-protein interactions, such that relevant transient/weak interactions may be missed. Furthermore, mixing of compartments during cell lysis can lead to the recovery of false positives interactors, because of associations that would not normally occur in living cells. Proximity-dependent biotinylation-coupled mass spectrometry (PDB-MS) has emerged as a highly sensitive assay that allows the labeling of proximal proteins in living cells in their native environment (53). Here we used PBD-MS to perform a comprehensive analysis of CTD proximal proteins, which allowed the identification of more than 150 proteins involved in chromatin remodelling, histone modifications, transcription-related processes, RNA processing, and nucleotide excision repair. By combining our PDB-MS approach with yeast genetics, we searched for phosphorylation-dependent CTD interactions using an endogenously expressed phospho-deficient Rpb1 mutant in which S2 was replaced by alanine (S2A) in every repeat of the fission yeast CTD. Notably, CTD-dependent biotinylation of most mRNA 3′ end processing factors was not affected in S2A and lsk1Δ mutants, indicating that CTD S2 phosphorylation is not a prerequisite for the recruitment of the cleavage and polyadenylation machinery. Accordingly, RNA-seq and RNAPII ChIP-seq analyses using the S2A mutant did not demonstrate global defects in mRNA 3′ end processing and transcription termination. In contrast, our results revealed that CTD S2 phosphorylation is critical for the association between RNAPII and the histone MTase Set2, as well as for the co-transcriptional activation of Set2 on chromatin. Consequently, the S2A mutant showed widespread accumulation of antisense ncRNAs because of defective intragenic histone deacetylation by the Set2-Clr6(II) axis. Our findings thus reveal that the primary function of the dynamic and conserved pattern of CTD S2 phosphorylation during RNAPII transcription is to introduce a repressive chromatin state in coding regions of genes, preventing the aberrant use of spurious cryptic promoters.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and media

A list of all S. pombe strains used in this study is provided in Supplementary Table S8. Fission yeast cells were routinely grown at 30°C in Edinburg minimal media (EMM2, US biological, E2205) or yeast extract medium (YES) supplemented with adenine, uracil, histidine, and leucine. For analysis of nmt-pcf11 and nmt-seb1 conditional strains, cells were grown in EMM supplemented with amino acids and treated with 60 μM of thiamine for 12–14h to repress nmt-dependent transcription. For TurboID assays, cells were grown in YES medium supplemented with amino acids and 50 μM biotin (Aldrich, B4501). The addition of C-terminal tags (TurboID, myc, Flag, HA) was performed by PCR-mediated gene targeting using the lithium acetate method for yeast transformation, as previously described (54). Gene deletions and tagging were confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively.

Proximity-dependent biotinylation using TurboID

TurboID assays of Rpb1 were performed as described previously (55). 50 ml of yeast cultures were grown to reach OD600 nm of 0.5–0.6 in YES medium supplemented with required amino acids and 50 μM biotin. Cell pellets were resuspended in 250 μl of cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, supplemented with 0.4% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1× PLAAC and 1× complete) prior to lysis with glass beads using a FastPrep-24™ (MP biomedical) with 3 cycle of 30s at 6.5 m/s. Sample volume was increased to 500 μl using the same buffer before sonication for three cycles of 10 s at 20% intensity using a Branson Sonifier 250. DNA and RNA were then digested with 250 units of benzonase (Sigma-Aldrich; E1014) for 1 h at 4°C. Clarified lysates were normalized for total protein concentration by performing a Bradford protein assay. Then, 5–6 mg of total proteins were subjected to affinity purification for 3 h at 4°C with 50 μl of Streptavidin–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare; 17-5113-01) in 1 ml of cold RIPA buffer with the exception that the SDS concentration was increased from 0.1% to 0.4%. All biotin-based purifications were performed using Protein LoBind tubes (Eppendorf). Beads were then washed once with wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 2% SDS), three times with RIPA buffer containing DTT (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP40, 1 mM DTT), and five times with 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate. All washes were done for 5 min at room temperature with rotation. Streptavidin-bound proteins were reduced in 10 mM DTT before being alkylated with 15 mM of iodoacetamide (IAA). Protein-bound beads were subjected to trypsin digestion at 37°C overnight and stopped by the addition of formic acid (final concentration of 1%). Peptides were then extracted using acetonitrile, lyophilized, and resuspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to desalt on ZipTips. ZipTips (EMD Millipore) cleanup of peptide samples was performed as described previously (56).

LC–MS/MS analysis

Trypsin digested samples were analyzed by LC–MS/MS as described previously (56). Briefly, 250 ng of each sample was injected into an HPLC (nanoElute system Bruker Daltonics) and loaded onto a trap column with a constant flow of 4 ml/min (Acclaim PepMap100 C18 column, 0.3 mm id × 5 mm, Dionex Corporation, catalog # 164567), and then eluted onto an analytical C18 Column (1.9 mm beads size, 75 mm 3 25 cm, PepSep). Peptides were eluted over 2 hours in a gradient of acetonitrile (5–37%) in 0.1% FA at 500 nl/min while being injected into a TimsTOF Pro ion mobility mass spectrometer equipped with a Captive Spray nano electrospray source (Bruker Daltonics). Data was acquired using data-dependent auto-MS/MS with a 100–1700 m/z mass range, with PASEF enabled, number of PASEF scans set at 10 (1.27 s duty cycle), a dynamic exclusion of 0.4-min, m/z dependent isolation window and collision energy of 42.0 eV. The target intensity was set to 20 000, with an intensity threshold of 2500. Data acquisition has been done using the Xcalibur software version 4.1. Raw data files were analyzed using MaxQuant version 1.6.17.0 and using the S. pombe proteome from Uniprot database.

RT-qPCR and northern blot assays

Total RNA was extracted by the hot-phenol method, as previously described (56). Briefly, yeast cells were first resuspended in 600 μl of TES solution (10 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM EDTA [pH8.0] and 0.5% SDS) and then treated with 600 μl of phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (125:24:1 [pH 4.5]) at 65°C for 60 min with vortexing every 10 min. RNA was extracted once with 550 μl of phenol-chloroform-Isoamyl alcohol (125:24:1 [pH 4.5]), once with 450 μl of chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (24:1), and ethanol precipitated.

For RT-qPCR analysis, 1 μg of total RNA was treated with 1 unit of RNase-free DNase RQ1 (Promega, M6101) for 30 min at 37°C and inactivated with 1 μl of 25 mM EDTA for 10 min at 65°C. Reverse transcription reactions were in a volume of 20 μl using 200 ng of total DNase-treated RNA, 0.1 μM of each strand-specific primer, and 2 units of M-MLV (RT) for 60 min at 42°C. RT reactions were inactivated for 20 min at 65°C. qPCR assays were performed in triplicates on a LightCycler 96 system (Roche) in a final volume of 15 μl using 6 μl from a 1:20 dilution of each cDNA, 0.15 μM of forward and reverse primers, and 7.5 μl of the 2× SYBR Green (QuantaBio). Analysis of gene expression changes were calculated relative to the appropriate control S. pombe strain and were measured with the ΔΔCT method using the nda2 gene as internal reference. The oligonucleotides used in the RT-qPCR experiments are listed in Supplementary Table S9.

For northern analysis, 20 μg of total RNA was mixed with 0.6 volume of loading buffer and separated on a 0.8% agarose gel containing formaldehyde for 4 h at 200V. RNAs were transferred onto a nylon membrane (Amersham hybond-XL), crosslinked twice, and then pre-hybridized in Church buffer at 42°C for 30 min. RNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription using T7 or SP6 polymerases (NEB) to make RNA probes complementary to transcripts of interest. The probes were then hybridized to membranes overnight at 65°C. The next day, unbound riboprobes were washed away by two washes with 2× SSC/0.1% SDS for 5 min and once with 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS for 15 min. The radioactive filters were exposed overnight using phosphor screen and scanned on a Typhoon Trio instrument.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-seq experiments were performed as described previously (57). For each condition (IP), 50 ml of cell cultures were grown to an OD600 of ∼0.5 at 30 °C in YES and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature with manual shaking every 5 min. After quenching the solution with glycine (final concentration of 360 mM), cells were washed twice with cold Tris-buffer saline (20 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.5] and 150 mM NaCl) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cell pellets from 50 ml cultures were thawed and resuspended in 500 μl of cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% Na-deoxycholate) that was supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (1X PMSF and 1X PLAAC) and disrupted vigorously with glass beads in a FastPrep-24™ (MP biomedical) for 3 cycles of 30 s at 6.5 m/s. Then, 150 μl of cold lysis buffer with proteases was added to increase the volume and samples were sonicated for 12 cycles of 10 s at 20% amplitude with a Branson digital sonifier. Sonicated chromatin was then incubated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of magnetic beads IgG Dynabeads (Life Technologies, 11041) in the case of TAP tagged proteins, or Dynabeads M-280 Sheep Anti-Rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, 11203D) beads coupled with 2 ug of rabbit anti-Histone H3 total (ab1791, abcam), H3K36me2 (ab9049, Abcam), H3K36me3 (ab9050, abcam) or H3K9ac (06–942, Millipore Sigma). ChIP analysis of Rbp3-HA and Rpb3-Flag occupancy used anti-HA (Sigma #H6908) and anti-Flag (Sigma #F3165), respectively. Beads were then washed twice for 4 min at 4°C with 1 ml of cold lysis buffer, twice with 1 ml of cold lysis buffer with 500 mM NaCl, twice with 1 ml of cold wash buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 1 mM EDTA), and once with 1 ml of cold Tris-EDTA (TE: 10 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0] and 1 mM EDTA [pH8.0]). Bound material was eluted by resuspending the beads in 50 μl elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA and 1% SDS) at 65 °C for 15 min at 1200 rpm in an Eppendorf Thermomixer. After a short centrifugation, reverse-crosslinking was performed by incubating eluted chromatin with 120 μl of TE and 1% SDS or 5 μl of WCE in 165 μl of TE with 1% SDS at 65 °C overnight. For ChIP-Seq experiments, reverse-crosslinking was performed by incubating eluted chromatin with 20 μl of WCE in 150 μl of TE and 1% SDS. Samples were treated with a proteinase K mix (150 mg proteinase K, 60 mg glycogen in TE) and DNA was extracted twice with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, [pH8.0], Invitrogen) and once with chloroform (Bioshop). Following ethanol precipitation, pellets were resuspended in 30 μl of TE plus 10 μg of RNAse A and incubated 1 h at 37 °C. RNase-treated DNA was then purified with a QIAGEN PCR purification kit. For ChIP-qPCR, the input DNA was diluted 100 times while the coimmunoprecipitated DNA (IP) was diluted 20 times in water. For ChIP-Seq, the input DNA was diluted 400 times while the coimmunoprecipitated DNA was diluted 100 times in water. DNA were analyzed on a LightCycler 96 Instrument system (Roche) with the addition of the 2× SYBR Green in the presence of 0.15 μM of gene-specific oligonucleotide. Protein occupancy was calculated using the percent input method (57). ChIP-sequencing libraries were prepared using the SPARQ DNA Sample Prep Kit Illumina Platform (Quantabio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. ChIP-seq experiments of histone modifications were performed with a spike-in (5% S. cerevisiae) adjustment procedure that allows a quantitative comparison between independent strains.

RNA-seq library preparation

rRNA-depleted RNA-seq libraries were prepared following manufacturer's instructions using the Illumina Truseq Stranded Total RNA-sequencing kit after ribodeletion with the RiboZero Yeast ribodepletion (Epicentre). RNA-seq libraries were sequenced in paired-end (2 × 100nt) using Illumina technologies (HiSeq 4000) at Genome Québec.

Analysis of proteomic data (TurboID)

Peptide identification was performed with MaxQuant version 1.6.17.0 using the S. pombe proteome downloaded from Uniprot. To define the CTD-proximal interactome, the protein-level spectral counts from at least three independent biological replicates of control (untagged) and Rpb1 CTD-TurboID strains were analyzed using SAINTexpress (58) and imported into R. Differential association of CTD-proximal proteins in the wild-type Rpb1 CTD compared to mutant strains (S2A, lsk1Δ) was analyzed using the DEqMS package (59). Network analysis was performed with Cytoscape (60).

ChIP-seq data analysis

Reads were mapped using HISAT2 (61) with option –no-splice-alignment on a concatenate genome containing the S. pombe (build ASM294v2.26) and S. cerevisiae chromosomes. Normalization factors were computed based on the proportion of reads mapped to the S. cerevisiae genome as previously described (62) while the average fragment size was estimated using MACS2 predicted function (63). Based on the normalization factors and averaged fragment size, we used deepTools (64) to generate normalized read density files (.bigwig) with options bamCoverage –smoothlength 20 –centerReads -e [average_fragment_size] –scaleFactor [size_factor] -bs 1 -of bigwig. If no spike-in was available (as it is the case for the Pcf11-myc and Set2-TAP ChIP data), the option –normalizeUsing RPKM was used instead of –scale factor.

For metagene analysis, the read density files were further normalized by input subtraction or, in the cases H3K36me and H3K9ac, by division by total H3 using deeptools bigwigCompare function. Replicates were merged and read density values on protein-coding genes were computed using deeptools computeMatrix with either options scale-regions -a 1000 -b1000 -bs 10 to calculate it on 2 kb windows centered on TES, or options reference-point –referencePoint TES -a 1000 -b1000 -bs 10 to consider windows spanning 1 kb before TSS and 1 kb after TES with the gene body of each gene scaled to 1 kb. The R software was used to draw the obtained read density matrix as position-averaged profiles.

To compute a termination index from the RNAPII (Rpb3-HA) ChIP-seq read density files, we implemented a method almost identical to the previously described readthrough index (20). It relies on the estimation of the termination window by computing the distance between the position of maximum RNAPII occupancy on protein coding genes and a downstream coordinate with RNAPII occupancy corresponding to 25% of gene maximum. The difference in the estimated termination window distance in mutant strains compared to the WT is the termination index. To limit the contribution of neighboring genes into local RNAPII occupancy, only non-convergent protein coding genes longer than 500 bp, with robust RNAPII ChIP signal (max density peak >40 for the S2A dataset and >5 for the other datasets), and a termination index smaller than 1000 were considered in this analysis.

RNA-seq data analysis

Reads were mapped to the S. pombe genome (build ASM294v2.26) with HISAT2 with default parameters (61). Gene-level read quantification was made with FeatureCounts (65) with options -p -B -s 2 -P -d 0 -D 5000 -C -T 4. De novo transcript discovery was performed with Stringtie (66) using stringent options (-t -f 0.1 -c 5 –rf -s 5) that are better suited to the dense yeast genome than the default. The new transcript discovered in the S2A mutant were merged in the annotation if they did not overlap other transcripts on the same strand. Differential gene expression of mutant against WT was made with DESeq2 (67). Based on DESeq2 scaling factors, we used deepTools to generate normalized read density files (.bigwig) with options bamCoverage –samFlagExclude 256 –maxFragmentLength 5000 –scaleFactor [1/size_factor] -bs 1 -of –filterRNAstrand [fwd/rev] bigwig. Raw reads and strand-specific read density files in bigWig format are provided for each sample and available on GEO (GSE249236). The read per gene count table is also available on GEO in tabular format. The results of the de novo transcript discovery are available in Supplementary Table S6.

For metagene analysis (position-average profiles), the strand-specific read density from replicate conditions were merged and read density values on protein-coding genes were computed using deeptools computeMatrix as described in the ChIP-seq data analysis section. To limit the contribution of extremely highly and lowly expressed genes, we chose to use a 5% trimmed mean (the 2.5% most extreme values from each end of the distribution were ignored) to draw the position-averaged profiles.

Microarray data re-analysis

To remap ancient dual-color tiling micro-array (lsk1Δ versus WT) data (12) to the current S. pombe genome annotation, we used GEOquery (68) to import the series (GSE16498) and platform (GPL8679) data from GEO into R. The genomic range covered by the probes was mapped on the current S. pombe annotation using the BiomaRt (69) and GenomicFeatures (70) packages. Differential gene expression due the deletion of lsk1 was then recalculated using the Limma package (71). The dye effect (it was a dye-swap experiment) was added into the statistical model as a covariate.

Results

Proximity-dependent biotinylation map of the RNAPII CTD

To define the diversity of factors connecting the RNAPII CTD, we adapted a proximity-dependent biotinylation assay coupled to mass spectrometry (PDB-MS) developed for yeast based on protein biotinylation by the TurboID biotin ligase (55). A fission yeast strain was therefore generated in which the endogenous rpb1 allele was fused with DNA sequences encoding TurboID. Growth assays using the Rpb1-TurboID strain showed growth rates comparable to a control untagged strain in both rich and minimal media (Supplementary Figure S1A and B), suggesting that the fusion of TurboID to the CTD did not impair Rpb1 function. In this strain, CTD-proximal proteins are expected to be biotinylated in their native cellular environment (Figure 1A), including phospho-specific CTD interactions.

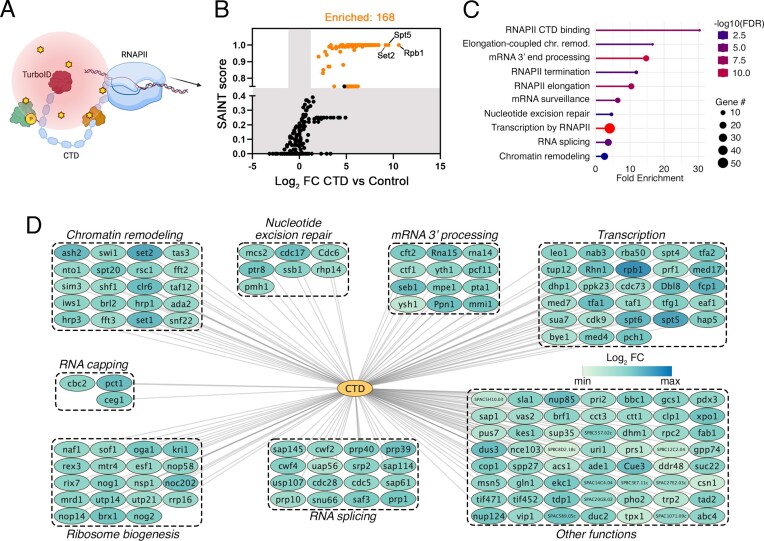

Figure 1.

Proximity interactome of the Rpb1 CTD in living cells. (A) Schematic representation of the proteomics approach used (TurboID, proximity-dependent biotinylation) to identify CTD-proximal proteins in living cells in the native cellular environment of the RNAPII complex. The cloud of activated biotin molecules (yellow stars) is represented by the red spheric gradient estimated to have a labelling radius of approximately 10 nm. (B) Global CTD proximity interactors identified by TurboID. Shaded areas represent cut-off range of SAINT score and log2 Fold Change (CTD versus Control). N = 4 independent biological replicates. (C) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis from the list of 168 significant CTD-proximal proteins depicted as a lollipop graph. The biological processes and number of proteins (genes) associated with each GO categories are indicated. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) was set to 0.05. (D) Network of the CTD proximal interactome organized by biological processes found to be significantly enriched.

To identify a list of CTD-proximal proteins, samples from the Rpb1-TurboID and control strains were analyzed by MS from four independent biological replicates. Significantly enriched factors were determined using SAINT (Significance Analysis of INTeractome), which is a statistical method for probabilistically scoring protein-protein interactions from MS data (58). In total, our analysis (SAINT score ≥ 0.75; Bayesian False Discovery Rate (BFDR) ≤ 0.05; Log2 fold-change ≥ 1.0) identified 168 high-confidence CTD-proximal proteins (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table S1). Gratifyingly, our PDB-MS analysis of the S. pombe CTD successfully identified factors previously shown to copurify with phosphorylated versions of the CTD in budding yeast (Supplementary Figure S1C and Supplementary Table S2) (50). The top-3 biotinylated proteins based on peptide spectral counts in the CTD tagged-TurboID strain were the RNAPII catalytic subunit Rpb1, the transcription elongation factor Spt5, and the histone MTase Set2 (Figure 1B). Gene ontology (GO) analysis using g:Profiler (72) of all significantly enriched CTD-proximal proteins revealed that our PDB-MS approach identified known CTD-binding proteins (Pct1, Ceg1, Pcf11, Seb1, Leo1 and Rhn1) as well as factors enriched in transcription-related categories, including the preinitiation complex, transcription elongation and termination (Figure 1C, D and Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, GO and protein–protein interaction database (STRING) analyses identified functional clusters involved in RNA processing, such as in RNA capping, RNA splicing, and 3′ end processing among the CTD-proximal proteins (Figure 1C, D). CTD-proximal protein biotinylation also identified a set of factors enriched in chromatin remodeling functions (Figure 1C, D), including components of the SAGA, DSIF, SWI/SNF, Set1C and HULC complexes (Supplementary Figure S1D). Our PDB-MS analysis of the CTD also showed significant enrichment for ribosome biogenesis factors as well as proteins involved in nucleotide excision repair (Figure 1D). In sum, our PBD approach in living cells provides a comprehensive profile of CTD-proximal proteins during the RNAPII transcription cycle.

CTD S2 phosphorylation is not required for mRNA 3′ end processing and transcription termination

Our PDB approach using the TurboID-tagged Rbp1-CTD allows for the identification of protein factors that are differentially associated with phospho-specific CTD modifications in living cells. To assess the capability of using PDB-MS for the S2 phosphorylation, which is best characterized for its connection with RNA 3′ end processing and termination of RNAPII transcription (1,2), a phospho-deficient rpb1 allele in which S2 was replaced by alanine (S2A) in every repeat of the fission yeast CTD (Figure 2A) (25) was tagged with TurboID at the endogenous rpb1 chromosomal locus. To identify proteins showing differential enrichment following TurboID analysis of wild-type and S2A versions of the CTD, we used a statistical method (DEqMS) specifically developed for differential protein expression analysis using label-free quantification of MS data (59) (Supplementary Table S4). As shown in Figure 2B, eleven proteins demonstrated significantly decreased CTD-proximal biotinylation in the S2A mutant relative to the wild-type. Pcf11 and Rhn1 (S. cerevisiae Rtt103 homolog), two proteins with CID domains that show cooperative and preferential binding to phosphorylated CTD peptides (14,15), were among factors demonstrating significantly reduced proximity with the S2A CTD (Figure 2B). Notably, the protein showing the most significantly reduced levels of CTD-proximal biotinylation in the S2A mutant was the lysine MTase Set2 (Figure 2B). Set2 has been shown to interact with phosphorylated versions of the CTD via its Set2 Rpb1-interacting (SRI) domain (35,37,48). TurboID analyses using the CTD S2A mutant also demonstrated reduced association with the transcription elongation regulators Bye1 and Spt4 as well as the Mediator complex subunit Med7 (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the S2A version of the CTD showed significantly increased association with six proteins, including three nucleoporins, Nup124, Nup61, and Nup60, as well as the 3′ end processing factor Rna14 (Figure 2B). Together, our PDB-MS approach identified phospho-dependent CTD associations in living cells, including previously described S2P-dependent CTD interactors (Pcf11 and Rtt103) as well as novel factors not previously known to be influenced by CTD S2 phosphorylation.

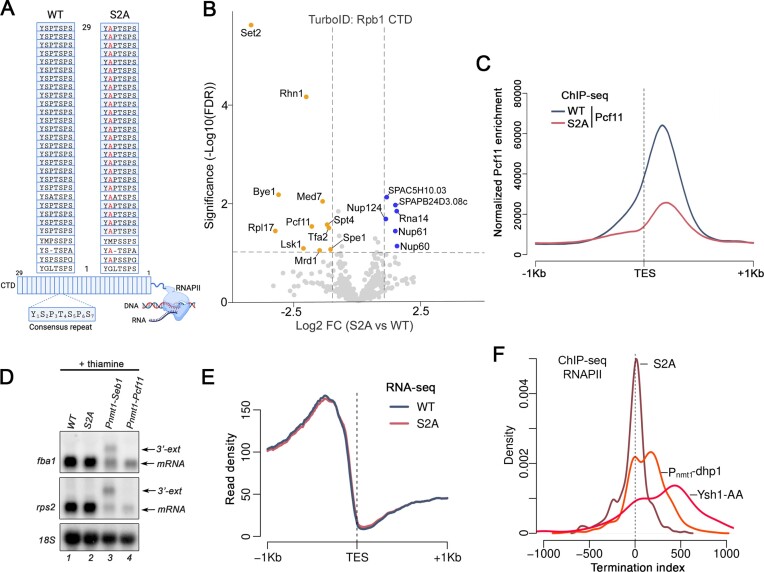

Figure 2.

Serine 2 CTD phosphorylation is not required for mRNA 3′ end processing and transcription termination. (A) Schematic of the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of wild-type and S2A versions of the fission yeast RNAPII complex. Each rectangle represents one CTD heptad repeat, and the consensus sequence is shown below. (B) Volcano plot of statistical significance (FDR, False Discovery Rate) against fold change (in log2) of CTD-proximal proteins in the S2A mutant relative to the wild-type CTD (N = 7 biological replicates). The dashed lines represent the thresholds for calling significant differential CTD association: FDR ≤ 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change ≥1.0. Proteins showing significantly decreased and increased CTD-proximal biotinylation in the S2A mutant are shown in orange and blue, respectively. (C) Pcf11 average occupancy (N = 1 biological replicate) around transcription end site (TES) of expressed protein-coding genes (n = 500) in the wild-type and S2A mutant. (D) Northern blot analysis of fba1 and rps2 mRNAs prepared from the indicated strains grown in minimal media supplemented with thiamine. 3′-extended transcripts accumulating in Seb1-deficient strains (73) are shown (3′-ext). (E) Curves show the average normalized RNA-seq signal for two replicates over the TES of 5132 genes. (F) Distribution of the termination index of expressed non-convergent protein-coding genes in the indicated strains. n = 340, 483 and 237 genes for the S2A, Pnmt-dhp1 and Ysh1-Anchor Away (AA) datasets, respectively.

Our unbiased proteomics approach revealed that the association between Rpb1 and (i) the mRNA 3′ end processing factor Pcf11 and (ii) the transcription termination protein Rhn1 were decreased in the S2A mutant (Figure 2B). Consistent with the TurboID data, ChIP-seq analysis of Pcf11 revealed decreased occupancy at the 3′ end of genes in the S2A mutant, although the peak of Pcf11 crosslinking was positioned approximately at the same distance relative to TES (Transcription End Sites) between WT and S2A strain (Figure 2C). Yet, given that only two proteins involved in 3′ end processing/transcription termination showed decreased CTD proximity in the S2A mutant, we tested whether CTD S2 phosphorylation is important for cleavage and polyadenylation and/or termination of RNAPII transcription. We therefore used the full-length S2A mutant expressed from the endogenous rpb1 locus (Figure 2A) to assess the consequence of lacking CTD S2 phosphorylation on RNA 3′ end processing and transcription termination. We first used northern blotting to examine for expression and/or RNA processing defects in the CTD S2A mutant. As shown in Figure 2D, the expression and maturation of fba1 and rps2 mRNAs were unaffected in the CTD S2A mutant (compare lanes 1–2). In contrast, depletion of essential 3′ end processing factors Seb1 and Pcf11 led to decreased mRNA levels (Figure 2D, lanes 3–4) and 3′-extended transcripts in the case of Seb1 (Figure 2D, lanes 3). We also analyzed the rRNA-depleted transcriptome of WT and S2A mutant cells by strand-specific RNA-seq. Defects in mRNA 3′ end processing as analyzed by RNA-seq can be visualized by plotting cumulative transcript level on the same strand before and after annotated TES (Figure 2E). Whereas cells deficient for Pcf11 and Seb1 significantly impact mRNA 3′ end processing events genome-wide (73–75), transcript signal at the TES dropped similarly in WT and S2A strains (Figure 2E), consistent with the absence of 3′-extended read-through transcripts in the S2A mutant. We also examined RNAPII density genome-wide by ChIP-seq using a HA-tagged version of Rpb3, another RNAPII core subunit, in wild-type and S2A mutant cells. To analyze transcription termination efficiency at the genome-wide level, we computed a Termination index for all genes (see Methods), which measured the distance required for Rpb3 to reach 25% of its maximum density. As shown in Figure 2F, the peak of termination index distribution for the S2A mutant was near 0 and neither positively nor negatively skewed, indicating the absence of global transcription termination defects in the S2A mutant. As control for transcription termination defects, we computed termination indexes using RNAPII ChIP-seq datasets from cells deficient for the 5′-3′ exonuclease Dhp1 and the pre-mRNA endonuclease Ysh1 (62). The results demonstrated significant genome-wide transcription termination defects, as shown by the right-skewed distribution of termination indexes in Dhp1- and Ysh1-deficient cells (Figure 2F). Taken together, our results indicate that CTD Ser2 phosphorylation is not essential for mRNA 3′ end processing and RNAPII termination.

Widespread accumulation of antisense noncoding RNAs in the CTD S2A mutant

Given the absence of global defects in mRNA 3′ end processing in the S2A phospho-deficient CTD mutant, we next assessed the impact on gene expression using our strand-specific RNA-seq datasets (Supplementary Table S5). In total, 142 genes were down-regulated in the S2A mutant, including ste11, which encodes the master transcriptional regulator of the mating pathway in fission yeast (12), as well as the gene encoding the meiosis-specific RNA-binding protein, Mei2. Conversely, 392 genes were significantly up-regulated in the S2A mutant, of which 244 (62%) are annotated antisense noncoding (nc) RNAs (Figure 3A). The accumulation of antisense transcripts was specific to the CTD S2A mutant, as phospho-deficient rpb1 allele in which Tyr1 and Ser7 were substituted by phenylalanine (Y1F) and alanine (S7A) residues, respectively, in every repeat of the fission yeast CTD did not significantly alter the expression of antisense ncRNAs (Figure 3B).

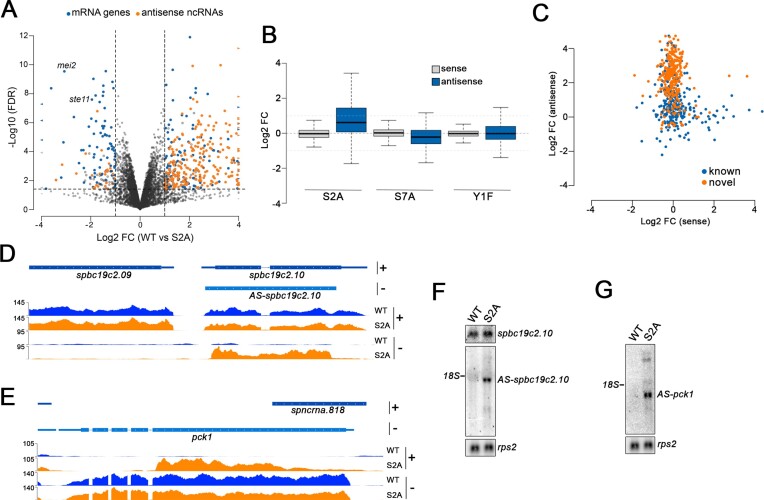

Figure 3.

Widespread derepression of antisense noncoding expression in the CTD S2A mutant. (A) Volcano plot of statistical significance against fold change (in log2) of gene expression in the CTD S2A mutant relative to the wild-type control (n = 7000 genes). Dashed lines represent the thresholds for calling significant differential expression: false discovery rate (FDR) <0.01 and absolute log2 fold change >1. To ease viewing, genes with values beyond axes limits are represented by arrowheads. Differentially expressed protein-coding genes and antisense ncRNAs are shown in blue and orange, respectively. (B) Box plot of fold change (in Log2) in expression of mRNA/antisense ncRNA genes (n = 558 pairs) in the sense (grey) and antisense (blue) orientation in the CTD S2A, S7A, and Y1F mutants relative to the wild-type control. (C) Scatter plot showing the fold change (in log2) in sense mRNA accumulation versus the fold change (in log2) in antisense transcript accumulation in the CTD S2A mutant relative to the wild-type control. Annotated (blue) and novel (orange) ncRNAs detected are shown. (D, E) Normalized strand-specific RNA-seq read density average over two replicates for the spbc19c2.10 gene locus with an annotated antisense (AS) transcript (D) and pck1 gene locus with a novel AS ncRNA (E) in wild-type (blue) and S2A (orange) strains. The + and – signs represent the strand from which signal is shown. (F, G) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from wild-type and S2A strains. Strand-specific riboprobes were used to detect the spbc19c2.10 mRNA and antisense (AS) transcript (F) as well as AS transcripts expressed from the pck1 locus (G). The rps2 mRNA was used as loading control.

The PomBase annotation (76) currently includes 695 antisense ncRNA genes, of which 244 (35%) are up-regulated in the CTD S2A mutant. As the number of annotated antisense ncRNAs is likely an underestimate, we used StringTie (66) to identify novel antisense transcripts from RNA-seq reads in the S2A mutant, leading to the identification of 282 novel antisense ncRNAs (size from 200-nt up to 8-kb). Notably, 236 (84%) of those newly-identified antisense ncRNAs were significantly up-regulated in the S2A mutant (Supplementary Table S6). Globally, we therefore found a total of 480 (244 previously annotated + 236 novel) antisense ncRNAs up-regulated in the CTD S2A mutant (Figure 3C), thereby involving nearly 10% of fission yeast protein-coding genes. GO term analysis of protein-coding genes with up-regulated antisense ncRNAs revealed an enrichment in stress response genes (p= 0.002). Surprisingly, most of the 480 up-regulated antisense ncRNAs in the S2A mutant did not affect the expression of their complementary protein-coding gene (Figure 3B, C). Several observations could account for the fact that mRNA abundance is largely unaffected in the set of genes showing up-regulated antisense transcription in the S2A mutant. First, the predicted end sites for the set of antisense ncRNAs tend to be located downstream of the transcription start sites of mRNA genes (Figure 3D, E and Supplementary Figure S2A), thereby reducing the likelihood of interfering with promoter activity of mRNA genes. Second, mRNA genes with up-regulated antisense transcripts tend to be expressed at lower levels compared to other genes, such that highly expressed genes are depleted from this set (Supplementary Figure S2B). Accordingly, reduced transcription frequency likely decreases the possibility of head-to-head collisions between RNAPII molecules elongating in opposite directions. Although we found no bias for intron number and position in the set of mRNA genes with up-regulated antisense transcription in the S2A mutant, we found that S2A-sensitive antisense transcripts are preferentially associated with longer genes (Supplementary Figure S2C).

We next used strand-specific northern blotting to validate some of the antisense transcripts found to be up-regulated in the S2A mutant as determined by RNA-seq. As shown in Figure 3F, a major transcript was detected in the S2A mutant using a riboprobe complementary to the antisense ncRNA expressed from the spbc19c2.10 gene (AS-spbc19c2.10); this transcript was not detected in wild-type cells. The AS-spbc19c2.10 migrated slightly under the 1842 nt-long 18S rRNA (Figure 3F), which is consistent with the ≈ 1700 nt-long coverage detected by RNA-seq (Figure 3D). Also consistent with our RNA-seq data (Figure 3D), the levels of the spbc19c2.10 mRNA were similar between wild-type and S2A mutant (Figure 3F). Northern blot analysis also confirmed the accumulation of antisense transcripts expressed from the pck1 gene in the S2A mutant: a major ≈1500 nt-long transcript as well as weaker slower migrating transcript (Figure 3G). In conclusion, our results have identified a group of previously annotated and novel antisense transcripts that are derepressed in the absence of CTD S2 phosphorylation.

CTD S2 phosphorylation by Lsk1 represses antisense transcription via Set2-dependent H3K36 trimethylation

The aforementioned results revealed widespread derepression of antisense ncRNAs in the S2A mutant, suggesting a key role for CTD S2 phosphorylation in the suppression of cryptic antisense transcription. To confirm that the accumulation of antisense transcripts observed in the CTD S2A mutant is associated with the lack of phosphorylation (rather than the absence of Ser2), we investigated the contribution of CTD S2 kinases. In fission yeast, Lsk1 and Cdk9 have been associated with phosphorylation of the Rpb1 CTD on S2; yet, Lsk1 appears to be the major S2 kinase (12,77). Consistent with these previous studies, we also found that inactivation of Lsk1 had a more profound effect on Ser2 phosphorylation compared to Cdk9 (Supplementary Figure S3A). If Lsk1-mediated phosphorylation of the Rpb1 CTD on S2 is required for the suppression of antisense transcription, the set of antisense transcripts accumulating in the S2A mutant (Figure 3) should also be up-regulated in a strain deleted for lsk1. We therefore re-analyzed previously published microarray experiments using lsk1-null cells (12). As shown in Figure 4A, the changes in RNA expression in the lsk1Δ mutant generally correlate with the changes in the S2A mutant (R2 = 0.226, Pearson correlation coefficient) with a striking 86% of the annotated antisense ncRNAs significantly up-regulated in the S2A mutant being also up-regulated in the lsk1Δ mutant. The significant overlap of up-regulated antisense transcripts between the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants is consistent with the view that the derepression of antisense transcription in the S2A mutant is attributed to the loss of CTD S2 phosphorylation.

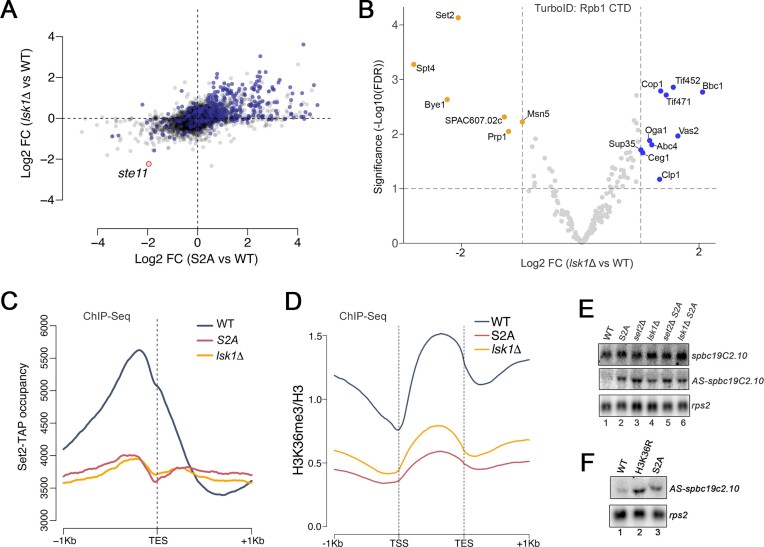

Figure 4.

Lsk1-mediated phosphorylation of CTD Ser2 represses pervasive antisense transcription via Set2-dependent H3K36 trimethylation. (A) Comparison of fold changes (log2 FC) between microarray and RNA-seq data obtained from lsk1Δ (y-axis) and S2A (x-axis) mutants, respectively. Blue and grey dots represent annotated antisense ncRNAs and protein-coding genes, respectively. (B) Volcano plot of statistical significance (False Discovery Rate) against fold change (in log2) of CTD-proximal proteins in the lsk1Δ mutant relative to wild-type control cells (N = 3 biological replicates). The dashed lines represent the thresholds for calling significant differential CTD association: FDR ≤ 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change ≥1.0. Proteins showing significantly decreased and increased CTD-proximal biotinylation in the lsk1Δ mutant are shown in orange and blue, respectively. (C) Gene metaplot of average ChIP-seq profiles of Set2 occupancy (N = 2 biological replicates) relative to annotated 3′ end of protein-coding genes (n = 5132) in WT (blue), S2A (red) and lsk1Δ (yellow) strains (n = 2 biological replicates per strain). (D) Gene metaplot of the average H3-normalized H3K36me3 signal (N = 2 biological replicates per strain) over gene bodies ±1 kb for WT (blue), S2A (red) and lsk1Δ (yellow) strains. (E) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from the indicated stains using strand-specific riboprobes to detect the spbc19c2.10 mRNA and antisense (AS) transcript. (F) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from control cells (lane 1) as well as from H3K36R (lane 2) and S2A (lane 3) mutants. A strand-specific riboprobe was used to detect the spbc19c2.10 AS transcript. The rps2 mRNA was used as loading control.

Next, we used TurboID to analyze the proximal CTD interactome in a wild-type strain and the lsk1Δ mutant. The analysis of differential CTD proximal proteins between the lsk1Δ mutant and the control strain is shown in Figure 4B (Supplementary Table S7). Among the proteins showing a significant change in CTD interaction between the lsk1Δ mutant and the wild-type strain, three were also significantly reduced in the CTD S2A mutant: Set2, Spt4 and Bye1 (Figure 4B). Notably, Set2 was the most significantly reduced CTD-proximal protein in the lsk1Δ mutant, consistent with the data obtained using the S2A mutant (Figure 2A). Given the marked reduction in Set2-CTD association in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants as determined by TurboID assays, we next analyzed the association of Set2 with chromatin at the genome-wide level in both mutant strains. Consistent with previous ChIP-seq analyses of Set2 in fission yeast (39,78), our metagene analysis in wild-type cells revealed increasing levels of Set2 occupancy along gene bodies, peaking at the 3′ end of genes (Figure 4C; blue profile). The distribution of Set2 occupancy differed substantially in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants: Set2 levels slightly increased downstream of transcription start sites (Supplementary Figure S3B), but rapidly plateaued along gene bodies and was therefore significantly decreased in the 3′ half of genes (Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure S3B). Importantly, Set2 protein levels were not reduced in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants (Supplementary Figure S3C). Consistent with reduced Set2 occupancy at the chromatin in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants, we found that the levels of H3K36 trimethylation were strongly decreased in cells deficient for CTD S2 phosphorylation (Figure 4D and Supplementary Figure S3D–G). Interestingly, H3K36me2 levels were not reduced in the S2A mutant; they were in fact greater than in the wild-type control strain (Supplementary Figure S3H, I). We thus conclude that the main consequence of defective CTD S2 phosphorylation is a reduction in Set2-dependent H3K36 trimethylation during the elongation phase of RNAPII transcription.

Set2-mediated H3K36 methylation is known to suppress antisense transcription in both budding and fission yeasts (30,34,78,79). To test whether the derepression of antisense transcription in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants is the direct consequence of reduced Set2 occupancy, we compared antisense RNA accumulation between single S2A, set2Δ, and lsk1Δ mutants to set2Δ S2A and lsk1Δ S2A double mutants. As shown in Figure 4E, antisense transcript levels expressed from the spbc19c2.10 locus were similar between the S2A and set2Δ single mutants compared to the set2Δ S2A double mutant (middle panel; compare lanes 2–3 to lane 5). Similarly, antisense RNA levels were similar between lsk1Δ and S2A single mutants compared to the lsk1Δ S2A double mutant (middle panel; compare lanes 2, 4 and 6). These data indicate that Lsk1-mediated CTD S2 phosphorylation functions in the same pathway as Set2 in the suppression of antisense transcription. To examine if the Set2-dependent suppression of antisense transcription is mediated through the methylation of H3K36, we used an histone mutant strain in which K36 in the hht2 gene was mutated to arginine (80), thereby generating a non-methylatable form of H3 (H3K36R). The H3K36R mutant exhibited increased expression of the antisense spbc19c2.10 transcript compared to isogenic control cells (hht1Δ hht3Δ) that retained an intact wild-type copy of the hht2 (H3.2) gene (Figure 4F). Taken together, our data indicate that the widespread accumulation of antisense ncRNAs in the absence of CTD S2 phosphorylation is caused by reduced H3K36 trimethylation in gene bodies, a consequence of defective Set2-RNAPII association during transcription elongation.

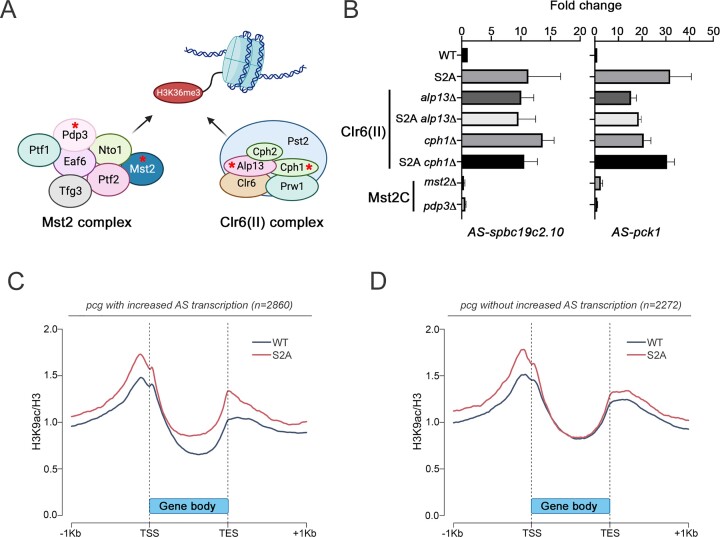

Clr6 complex II (Clr6(II))-dependent deacetylation of H3K9 suppresses cryptic antisense transcription via a pathway mediated by CTD S2 phosphorylation

In budding and fission yeasts, H3K36 methylation promotes chromatin restoration in the wake of transcription elongation by activating the evolutionarily conserved Rpd3S and Clr6(II) histone deacetylase complexes (HDAC) on transcribed genes (30–33). Rpd3S/Clr6(II)-mediated deacetylation of histone H3K9 tails compacts chromatin during transcription elongation and prevents cryptic transcription (30,32,33). Another conserved chromatin remodeling complex directed to active genes by H3K36 methylation is the NuA3b and Mst2 complex in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, respectively (81,82). In fission yeast, the Mst2 complex appears to prevent ectopic heterochromatin formation at transcriptionally active chromatin (81,83,84). To assess the contribution of the Clr6(II) and/or Mst2 complexes to the Lsk1-CTDS2P-Set2 axis in the suppression of cryptic antisense transcription, we deleted genes encoding subunits of each complex (Figure 5A) and measured antisense transcript levels by strand-specific RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure 5B, deletion of alp13 and cph1, which encode Clr6(II) subunits, resulted in increased antisense transcription. In contrast, deletion of pdp3 and mst2 genes, which code for subunits of the Mst2 complex, had no impact on antisense transcript levels (Figure 5B). Combining alp13 and cph1 deletions with the CTD S2A mutant did not results in an additive increase in antisense transcripts compared to single mutants (Figure 5B). Northern blot analysis confirmed the RT-qPCR results (Supplementary Figure S4A). These data indicate that the Clr6(II) complex and the Lsk1-CTDS2P-Set2 axis function in the same pathway. Accordingly, a pathway dependent on CTD S2 phosphorylation that suppresses cryptic antisense transcription via co-transcriptional H3K9 deacetylation predicts greater levels of H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac) at genes that showed derepression of antisense transcription in the S2A mutant. To test this model, we analyzed genome-wide levels of H3K9ac by ChIP-seq in wild-type and S2A mutant cells. Notably, protein-coding genes that showed increased antisense transcription in the S2A mutant revealed a clear increase in H3K9ac signal in gene bodies of the S2A mutant relative to the wild-type control strain (Figure 5C). Consistent with the ChIP-seq analysis, ChIP-qPCR validations on independent biological replicates confirmed increased level of H3K9 acetylation in the 3′ halves of S2A-sensitive genes in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants (Supplementary Figure S4B, C). Conversely, protein-coding genes that did not display accumulation of antisense transcripts in the S2A mutant showed no difference in H3K9ac signal in gene bodies between the two strains (Figure 5D). The lack of CTD S2 phosphorylation and the reduction in H3K36 trimethylation in the S2A mutant (Figure 4) did not impair the recruitment of Clr6(II) components Cph1 and Alp13 to chromatin (Supplementary Figure S4D, E), suggesting that H3K36 trimethylation is critical to stimulate the deacetylation activity of the Clr6(II) complex, but not its recruitment. Together, these data indicate that the primary role of CTD S2 phosphorylation is to stimulate co-transcriptional histone deacetylation behind elongating RNAPII via the Set2-Clr6(II) axis.

Figure 5.

Ser2 phosphorylation of the RNAPII CTD represses cryptic antisense transcription by stimulating co-transcriptional H3K9 deacetylation in gene bodies. (A) Schematic overview of Mst2 and Clr6(II) chromatin remodeling complexes known to be sensitive to Set2-dependent H3K36 methylation. Subunits highlighted by a red star were targeted by gene deletion for functional assays. (B) Strand-specific RT-qPCR analysis of spbc19c2.10 (left) and pck1 (right) antisense (AS) transcripts using total RNA from the indicated strains. The data and error bars represent the average and standard deviation from at least three independent experiments. (C, D) Gene metaplots of the average H3-normalized H3K9ac signal over gene bodies ±1 kb from WT (blue) and S2A (red) strains (N = 1) of protein-coding genes (pcg) that showed (C) or did not show (D) increased (>1.5-fold relative to WT) AS transcription in the S2A mutant.

Discussion

Using proximity biotinylation to define the CTD interactome in living cells, we disclose a comprehensive inventory of factors that associate with the RNAPII CTD throughout the transcription cycle. Furthermore, by characterizing an endogenously expressed, full length Rpb1 derivative in which S2 was replaced by alanine (S2A) in every repeat of the CTD, we show that (i) the association between the 3′ end processing machinery and the CTD, (ii) the cleavage and polyadenylation and (iii) transcription termination do not generally rely on CTD Ser2 phosphorylation. Conversely, our findings unveiled the critical role of CTD S2 phosphorylation in the establishment of a repressive chromatin state that prevents cryptic antisense transcription in coding regions via the phospho-dependent association between RNAPII and the histone methyltransferase Set2.

Our proximity map of the RNAPII CTD allowed for the isolation of CTD-proximal factors in the native cellular environment, independently of antibody-related biases and cell lysis conditions. In total, we identified 168 high-confidence CTD proximal proteins that will serve as a useful resource for future studies on the regulation of transcription and co-transcriptional processes. The identification of several factors involved in RNA capping, splicing, and 3′ end processing (Figure 1) is consistent with the CTD acting as a binding platform for the coupling between RNAPII transcription and RNA processing (1,2,85). The identification of factors that promote transcription activation (Med17, Med4, and Med7), elongation (e.g. Cdk9, Spt4, Spt5 and Spt6), RNAPII termination (e.g. Dhp1/Rat1 and Rhn1/Rtt103), and chromatin remodelling (e.g. Set2, Set1, Clr6/Rpd3 and Ash2/Bre2) is also consistent with the strong link between the CTD and these transcription-related steps. It is interesting that, except for Rpb1, additional subunits of the core RNAPII complex were not identified in the Rpb1-TurboID assays. Given the estimated 10 nm range of BirA-derived proximity labeling assays (86), the lack of biotinylation of additional RNAPII core subunits could be explained if the most C-terminal heptad repeats of the Rpb1 CTD are positioned/oriented distantly from the RNAPII core. Indeed, the last heptad repeat can be as distant as 90 nm from the core RNAPII in a fully extended CTD in S. cerevisiae (87). Alternatively, it is likely that RNAPII-associated proteins (Supplementary Table S1), including general transcription factors, Spt4/Spt5, Spt6, and PAF complex subunits (Leo1, Cdc73, Prf1) protected core RNAPII subunits from CTD-dependent biotinylation.

We then combined proximity labeling with yeast genetics to determine the role of phosphorylation in regulating CTD interactions, starting with CTD S2 phosphorylation in the current study. A genuine S2P-dependent CTD interaction is expected to be affected in both the full-length CTD S2A mutant and the lsk1 deletion. As such, our results (Figures 2 and 4) identified Set2, Spt4, and Bye1 as proteins that associate with the RNAPII CTD in a phosphoserine 2-dependent manner in vivo. In contrast, whereas Pcf11 and Rhn1 showed reduced CTD-proximal biotinylation in the S2A mutant (Figure 2B), their association with the CTD was not significantly altered in the lsk1Δ mutant (Figure 4B). This argues that serine 2 itself, rather than its phosphorylation, is important for the association of Pcf11 and Rhn1 with the RNAPII CTD. This conclusion is consistent with findings that the Pcf11 CID does not make direct contact with the S2 phosphate group in the CTD (14,15). For Rhn1, although the CID of its S. cerevisiae homolog, Rtt103, shows salt-bridge interaction with the S2-phosphate on CTD peptides (14), the Rtt103 CID also directly contacts the T4 phosphate group (88), which could explain the maintenance of Rhn1-CTD interaction in the lsk1Δ mutant (Figure 4B). Our proximity labeling analysis of phospho-dependent CTD associations also revealed that S2 phosphorylation is crucial to maintain Spt4-RNAPII contacts (Figures 2 and 4). This is intriguing, as Spt4 forms a dimer with Spt5 (89); yet, CTD-proximal Spt5 biotinylation was not significantly reduced in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants. The formation of a Spt4–Spt5 complex may not be critical for transcription, since spt4 is not essential for viability in budding and fission yeasts, whereas spt5 is an essential gene in both species. Future studies should reveal whether the S2P-sensitive Spt4-RNAPII association is global or gene-specific.

This work, together with previous findings, negate the premise that CTD S2 phosphorylation is required to recruit essential components involved in co-transcriptional RNA processing. Several arguments reinforce the conclusion that CTD S2 phosphorylation is not required to support mRNA 3′ end processing: (i) full length S2A mutants (as well as CTD S2 kinase deletion mutants) are viable in budding and fission yeasts, whereas most 3′ end processing factors are essential, (ii) our CTD interactome analysis using the lsk1Δ mutant did not reveal phospho-dependent changes in CTD associations for 3′ end processing factors (Figure 4), (iii) our northern blot and RNA-seq analyses showed normal mRNA splicing and 3′ end processing in the S2A mutant (Figure 2), (iv) transcription termination efficacy was similar between WT and S2A mutant strains, as demonstrated by RNAPII ChIP-seq assays (Figure 2). Although this conclusion may appear surprising considering previous work linking CTD S2P to mRNA 3′ end processing, many of the experimental systems previously used in the literature must be carefully evaluated. For instance, whereas other studies have also used CTD S2A mutations, most have relied on truncated versions of the CTD harboring only a fraction of the repeats (3,21,22,90). As CTD length is a key parameter of CTD function (3,6,91–93), it may be difficult to distinguish the effects resulting from the truncation versus those from the targeted mutations if they are exacerbated in the context of a truncated CTD. Hence, a full length authentic CTD S2A phosphorylation mutant expressed from the endogenous rpb1 locus was used in this study. Using this mutant, our Rpb3 ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analyses did not show global transcription termination defects in the S2A mutant (Figure 2). These observations are totally consistent with tiling array analyses of a ctk1 deletion and a full length rpb1-S2A mutant in S. cerevisiae (24), arguing that CTD Ser2 phosphorylation is not essential for CPF-dependent transcription termination. Yet, these data contrast with a previous ChIP-chip analysis of Rpb1-Flag using a full length CTD S2A mutant ectopically expressed in S. cerevisiae, which resulted in mild average readthrough of 50-bp for a subset of 300 genes (20). The underlying reasons for this apparent discrepancy remain unclear but may be related to differences in the methods used to measure RNAPII occupancy (ChIP-chip versus ChIP-seq) and/or the gene filtering strategies used for metagene analyses. In any event, our RNA analyses by northern blotting and RNA-seq provide strong evidence that splicing and 3′ end processing take place normally in the absence of CTD S2 phosphorylation. Our findings therefore favor a model whereby co-transcriptional recruitment of mRNA 3′ end processing factors may rely on the redundant use of different CTD modifications (94), phosphorylation-independent interactions with the CTD (95), and/or the presence of cis-acting sequences (e.g. poly(A) signal) in nascent transcripts (96,97).

A functional link between the RNAPII CTD and Set2-dependent H3K36 methylation was previously established (26,35–37). Specifically, Set2 harbors a C-terminal SRI domain that can recognize CTD heptad repeats that are di-phosphorylated on S2 and S5 residues in vitro (36,37). Yet, the interaction between Set2 and the phospho-CTD is not essential for Set2 recruitment to chromatin, since versions of Set2 lacking the SRI domain still localize to chromatin and ectopic expression of the Set2 catalytic domain (SET) alone is sufficient to promote H3K36 dimethylation (H3K36me2) (38–40). The importance of RNAPII CTD phosphorylation for Set2 function has therefore remained elusive. Notably, we now provide unambiguous evidence that Lsk1-mediated CTD S2 phosphorylation is critical to bolster Set2-RNAPII associations during transcription elongation and high levels of Set2-mediated H3K36 trimethylation (H3K36me3) in gene bodies. This conclusion is supported by results obtained in both S2A and lsk1Δ mutants that revealed significant reductions in (i) Set2-Rpb1 association (Figures 2 and 4), (ii) genome-wide Set2 occupancy on the chromatin (Figure 4C) and (iii) H3K36me3 levels on chromatin (Figure 4D), as well as by previous western blot analysis in fission yeast using truncated CTD S2A mutants that showed reduced total H3K36me3 levels (39,98). Importantly, we show that these defects in H3K36me3 are not the indirect consequence of Set2 destabilization (Supplementary Figure S3C), as observed in the budding yeast ctk1Δ mutant (38,40,41). The crucial role of CTD S2 phosphorylation to increase Set2 occupancy during transcription elongation at active genes (Figure 4C) is concordant with the coinciding genome-wide profiles of S2P and Set2, which both gradually increase with distance from the promoter and peak at the 3′ end of genes (39,62,78). How does CTD S2 phosphorylation bolster Set2 occupancy during RNAPII elongation? Although SRI-CTD interactions are not required for Set2 recruitment to active genes, reduced levels of Set2 are found on chromatin using an SRI deletion mutant of Set2 (39,40). Therefore, it is possible that the increasing concentration of S2P during elongation stimulates SRI-CTD associations that trigger changes in Set2 conformation, which would reinforce interactions between Set2 and histones (99–101). This S2P-dependent conformational change would also trigger trimethylation of H3K36 from H3K36me2, an activity that depends on the Set2 SRI domain (38–40) and that was strongly reduced genome-wide in the S2A and lsk1Δ mutants (Figure 4D). In addition to this allosteric model, it is probable that untethered Set2 can make transient interactions with nucleosomes to support H3K36me2, but a more stable interaction of Set2 with the S2-phosphorylated RNAPII CTD extends its residence time on chromatin, thereby allowing the enzyme to promote H3K36 trimethylation.

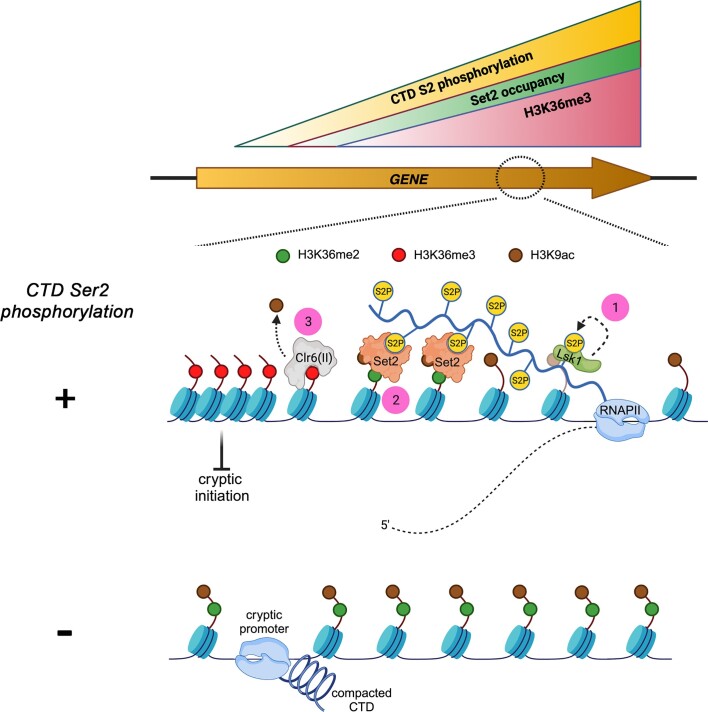

Our findings unveil a critical role for CTD S2 phosphorylation in the establishment of a repressive chromatin state that prevents cryptic transcription. While the accumulation of antisense transcription was previously noted using a similar CTD S2A mutant (102), the underlying mechanism had not been determined. We now show that CTD S2 phosphorylation is required for the activation of the Set2-Clr6(II) axis, which maintains the coding regions of genes in a hypoacetylated state and thereby represses initiation from cryptic intragenic promoters. Accordingly, we found that S2A-sensitive genes exhibiting increase antisense transcriptional activity had hyperacetylated chromatin in gene bodies (Figure 5C). Moreover, our genetic data indicated that S2 phosphorylation and the Clr6(II) complex function in the same pathway to repress cryptic transcription (Figure 5B). Collectively, our data support a model (Figure 6) in which the increased local concentration of CTD S2 phosphorylation during RNAPII elongation induces a conformational change in Set2 that stabilizes its association with RNAPII and triggers H3K36 trimethylation from H3K36me2. The ensuing increase in H3K36me3 levels stimulate the deacetylation activity of the Clr6(II) complex, consistent with the stimulatory role of the homologous Rpd3S complex in budding yeast by H3K36 methylation (103). Although our data support a role for the Clr6(II)/Rpd3S complex in S2P-dependent H3K9 deacetylation (Figure 5), other deacetylases could be involved as H3K9ac may not be a direct substrate of Rpd3S (104). The resulting deacetylation of H3K9 compacts chromatin behind the transcribing RNAPII and prevents pervasive initiation of transcription from cryptic promoters. Conversely, in the absence of Ser2 phosphorylation of the RNAPII CTD, acetylated histones accumulate on coding regions of genes leading to antisense transcription initiation from internal, cryptic promoters (Figure 6). Genes that depend on CTD S2 phosphorylation to prevent antisense transcription are less frequently transcribed and have longer transcription units (Supplementary Figure S2). Similarly, genes that depend on Set2-mediated H3K36 methylation to repress cryptic transcription in budding yeast are also infrequently transcribed long genes (34,105), consistent with the key role of CTD S2 phosphorylation in the activation of the Set2-Clr6(II) axis. Highly transcribed genes are likely to be less reliant on histone deacetylation to repress antisense transcription because the greater frequency of transcribing RNAPII may limit the assembly of preinitiation complexes at cryptic promoters. Interestingly, data presented in this study as well as results from others (39) indicate that H3K36me3, but not H3K36me2, is required to establish a repressive chromatin state in fission yeast. The repression of cryptic transcription by mammalian SETD2 (106,107) also appears to require H3K36me3, as chromatin from SETD2-deficient cells loose H3K36me3, but not H3K36me2 (108). The requirement for H3K36me3 may not be universal, however, as H3K36me2 appears to be sufficient to repress cryptic transcription in S. cerevisiae (40,42).

Figure 6.

Model of how CTD Ser2 phosphorylation represses cryptic antisense transcription by controlling histone modifications. (1) CTD S2 Phosphorylation (S2P) is mediated by the conserved cyclin-dependent kinase Lsk1. S2P levels gradually increases during the elongation phase of transcription and reaches a peak at the 3′ end of genes. (2) The interaction between Set2 and the RNAPII CTD is not necessary for Set2-mediated dimethylation of H3K36 (H3K36me2): yet, S2P is required for optimal interaction between Set2 and RNAPII as well as to promote H3K36me3. (3) H3K36me3 activates the Clr6(II) deacetylase complex, resulting in H3K9 deacetylation and a repressive chromatin state for transcription initiation at intragenic cryptic promoters. In the absence of Ser2 phosphorylation (bottom), the CTD adopts a more compact conformation and the interaction between Set2 and RNAPII is impaired. This results in gene bodies with increased H3K9 acetylation, facilitating pervasive initiation of transcription from cryptic promoters.

Why is it important to repress cryptic antisense transcription? Although our RNA-seq data indicated that genes showing increase antisense transcription in the S2A mutant did not generally have reduced mRNA levels (Figure 3), cryptic noncoding transcription has been shown to impair the kinetics of transcriptional responses during environmental stress conditions (34,79,109). Accordingly, cells deficient in CTD S2 phosphorylation are sensitive to several stress conditions (12). In sum, our S2P-dependent proximity map of the RNAPII CTD revealed that the prime function of Ser2 phosphorylation is not to instigate co-transcriptional mRNA 3′ end processing, but rather to repress noncoding cryptic transcription. Future studies using proximity-dependent biotinylation to identify phospho-dependent CTD interactions on Y1, T4, S5 and S7 should be instrumental to unravel the complex network of interactions regulated by CTD phosphorylation and provide a better understanding of critical co-transcriptional gene regulatory mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Beate Schwer and Jason Tanny for critical reading of the manuscript; Marie-Pier Lalumière for the generation of wild-type and S2A Rpb1-TurboID strains; Jason Tanny for the analog-sensitive Cdk9- and Lsk1 strains; the sequencing analysis from the RNomics platform of the Université de Sherbrooke and Génome Québec.

Author contributions: F.B., D.H. and C.Y.S. conceived the original study. C.B., N.H. and C.Y.S prepared strains and performed TurboID assays. M.L., N.H. and C.B. prepared chromatin extracts for ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-seq analyses, including QCs and library preparations. C.B. and N.H. performed most of the RNA analyses. C.Y.S. and P-É.J. planned and designed the pipelines for processing the genomics and proteomics data. C.B., N.H., C.Y.S. and F.B. prepared and finalized the figure panels. F.B. wrote the manuscript, which was reviewed by all authors.

Contributor Information

Cédric Boulanger, RNA Group, Dept of Biochemistry & Functional Genomics, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec J1E 4K8, Canada.

Nouhou Haidara, RNA Group, Dept of Biochemistry & Functional Genomics, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec J1E 4K8, Canada.

Carlo Yague-Sanz, URPHYM-GEMO, The University of Namur, rue de Bruxelles, 61, Namur 5000, Belgium.

Marc Larochelle, RNA Group, Dept of Biochemistry & Functional Genomics, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec J1E 4K8, Canada.

Pierre-Étienne Jacques, Dept of Biology, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec J1K 2X9, Canada.

Damien Hermand, URPHYM-GEMO, The University of Namur, rue de Bruxelles, 61, Namur 5000, Belgium; The Francis Crick Institute, 1 Midland Road London NW1 1AT, UK.

Francois Bachand, RNA Group, Dept of Biochemistry & Functional Genomics, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec J1E 4K8, Canada.

Data availability

All the proteomic data have been deposited to the PRIDE ProteomeXchange consortium under the accession PXD047023. The raw and processed sequencing data (ChIP-seq and RNA-seq) generated for this study have been submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession number GSE249236. The data of our previously published RNAPII ChIP-seq analysis in Ysh1- and Dhp1-deficient strains (62) is available on GEO under the accession number GSE115595.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Funding

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) [RGPIN-2017-05482 to F.B.]; Programme bilatéral de recherche collaborative Québec – Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS) (to F.B. and P-É.J.); Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS) [PDR T.0012.14, CDR J.0066.16, PDR T.0112.21 to D.H.]; C.Y.-S. is a FNRS Postdoctoral Researcher. D.H. is an honorary FNRS Director of research and was affiliated with the University of Namur until 23 November 2023. Funding for open access charge: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Conflicts of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Harlen K.M., Churchman L.S. The code and beyond: transcription regulation by the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017; 18:263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zaborowska J., Egloff S., Murphy S. The pol II CTD: new twists in the tail. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016; 23:771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. West M.L., Corden J.L. Construction and analysis of yeast RNA polymerase II CTD deletion and substitution mutations. Genetics. 1995; 140:1223–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schneider S., Pei Y., Shuman S., Schwer B. Separable functions of the fission yeast Spt5 carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) in capping enzyme binding and transcription elongation overlap with those of the RNA polymerase II CTD. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010; 30:2353–2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fong N., Bentley D.L. Capping, splicing, and 3' processing are independently stimulated by RNA polymerase II: different functions for different segments of the CTD. Genes Dev. 2001; 15:1783–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosonina E., Blencowe B.J. Analysis of the requirement for RNA polymerase II CTD heptapeptide repeats in pre-mRNA splicing and 3'-end cleavage. RNA. 2004; 10:581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schuller R., Forne I., Straub T., Schreieck A., Texier Y., Shah N., Decker T.M., Cramer P., Imhof A., Eick D Heptad-specific phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II CTD. Mol. Cell. 2016; 61:305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suh H., Ficarro S.B., Kang U.B., Chun Y., Marto J.A., Buratowski S. Direct analysis of phosphorylation sites on the Rpb1 C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. 2016; 61:297–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Komarnitsky P., Cho E.J., Buratowski S. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 2000; 14:2452–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee J.M., Greenleaf A.L. CTD kinase large subunit is encoded by CTK1, a gene required for normal growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene Expr. 1991; 1:149–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bartkowiak B., Liu P., Phatnani H.P., Fuda N.J., Cooper J.J., Price D.H., Adelman K., Lis J.T., Greenleaf A.L. CDK12 is a transcription elongation-associated CTD kinase, the metazoan ortholog of yeast Ctk1. Genes Dev. 2010; 24:2303–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coudreuse D., van Bakel H., Dewez M., Soutourina J., Parnell T., Vandenhaute J., Cairns B., Werner M., Hermand D A gene-specific requirement of RNA polymerase II CTD phosphorylation for sexual differentiation in S. pombe. Curr. Biol. 2010; 20:1053–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barilla D., Lee B.A., Proudfoot N.J. Cleavage/polyadenylation factor IA associates with the carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001; 98:445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lunde B.M., Reichow S.L., Kim M., Suh H., Leeper T.C., Yang F., Mutschler H., Buratowski S., Meinhart A., Varani G. Cooperative interaction of transcription termination factors with the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010; 17:1195–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meinhart A., Cramer P. Recognition of RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain by 3'-RNA-processing factors. Nature. 2004; 430:223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Licatalosi D.D., Geiger G., Minet M., Schroeder S., Cilli K., McNeil J.B., Bentley D.L. Functional interaction of yeast pre-mRNA 3' end processing factors with RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. 2002; 9:1101–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sadowski M., Dichtl B., Hubner W., Keller W. Independent functions of yeast Pcf11p in pre-mRNA 3' end processing and in transcription termination. EMBO J. 2003; 22:2167–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahn S.H., Kim M., Buratowski S. Phosphorylation of serine 2 within the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain couples transcription and 3' end processing. Mol. Cell. 2004; 13:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davidson L., Muniz L., West S. 3' end formation of pre-mRNA and phosphorylation of Ser2 on the RNA polymerase II CTD are reciprocally coupled in human cells. Genes Dev. 2014; 28:342–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Collin P., Jeronimo C., Poitras C., Robert F. RNA polymerase II CTD tyrosine 1 is required for efficient termination by the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 pathway. Mol. Cell. 2019; 73:655–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gu B., Eick D., Bensaude O. CTD serine-2 plays a critical role in splicing and termination factor recruitment to RNA polymerase II in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:1591–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsin J.P., Xiang K., Manley J.L. Function and control of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphorylation in vertebrate transcription and RNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014; 34:2488–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dower K., Rosbash M. T7 RNA polymerase-directed transcripts are processed in yeast and link 3' end formation to mRNA nuclear export. RNA. 2002; 8:686–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lenstra T.L., Tudek A., Clauder S., Xu Z., Pachis S.T., van Leenen D., Kemmeren P., Steinmetz L.M., Libri D., Holstege F.C. The role of Ctk1 kinase in termination of small non-coding RNAs. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e80495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cassart C., Drogat J., Migeot V., Hermand D Distinct requirement of RNA polymerase II CTD phosphorylations in budding and fission yeast. Transcription. 2012; 3:231–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]