Short abstract

Interactions between doctors and drug companies can lead to ethical dilemmas. This article gives an overview of the guidance and codes of practice that aim to regulate the relationship

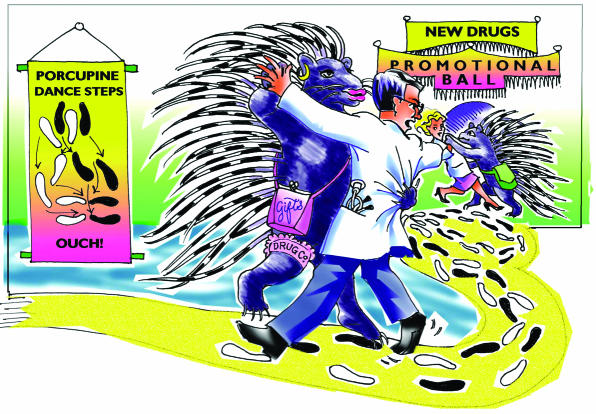

Like the porcupine's quills, drug companies' interactions with doctors are numerous and can be harmful if approached the wrong way. (Lewis and colleagues used the analogy of dancing with porcupines to describe university-industry relations,1 and I liked it so much I have appropriated it.) I have aimed to highlight the major rules and guidelines relating to interactions between doctors and drug companies, but this is not an exhaustive survey.

Figure 1.

SUE SHARPLES

Drug company codes of practice

Codes of conduct for pharmaceutical companies developed by industry organisations tend to be voluntary but are often backed up by complaints procedures. Many countries with major pharmaceutical sectors have national codes, such as those of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI),2 Medicines Australia,3 and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.4 These usually concentrate on drug companies' marketing activities—most prohibit companies from giving doctors inducements to prescribe their products in the form of payments, lavish gifts, or extravagant hospitality.

The ABPI code stipulates that gifts from companies must cost less than £6 (about $9 or €8) and be relevant to the doctor's work.2 The accompanying guidance helpfully explains that pens, diaries, and surgical gloves “have been held to be acceptable,” whereas table mats, plant seeds, and music CDs are not. The level of hospitality for meetings must be “appropriate and not out of proportion to the occasion,” and costs “must not exceed that level which the recipients would normally adopt when paying for themselves.” The Australian guidelines state that hospitality should be “simple, modest [and] secondary to the educational content” of a meeting.3 The venue for such meetings “must not be chosen for its leisure and recreational facilities,” and travel for journeys of under four hours “should be economy class.” In the United States, guidelines on gifts to physicians were strengthened in 2002.4 As in the United Kingdom, pens and calendars are permissible, but golf balls and DVD players are not.

Summary points

Codes of conduct for pharmaceutical companies developed by industry organisations tend to be voluntary but are often backed up by complaints procedures

Most such codes prohibit companies from giving doctors inducements to prescribe their products

Many doctors' organisations offer guidance about commercially funded research

Journal editors have issued a statement aimed at preventing suppression of unfavourable findings

Guidance on good publication practice for pharmaceutical companies was lacking until recently

Dialogue between the interested parties is needed before further guidance on the doctor-industry relationship is issued

For countries without national codes, two sets of international guidelines apply. These are the World Health Organization's Criteria for Medicinal Drug Promotion and the Code of Pharmaceutical Marketing Practice from the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations.5,6 Like the national guidelines, these codes cover promotional materials, which must, according to WHO, be “reliable, accurate, truthful, informative, balanced, up-to-date, capable of substantiation and in good taste.” The WHO guidelines also cover the activities of representatives and the supply of drug samples.

In France, doctors' relations with commercial companies are covered by the legal Code de la Santé Publique (article L.4113-6).7 This prohibits doctors from receiving benefits worth more than about €30 (£22; $34). Infringement of article 24 of the “code de déontologie” of the Conseil National de l'Ordre des Médecins, which relates to illegal payments to doctors, carries a fine of up to €75 000 (£55 000; $84 000) and a two year prison sentence.

In the United Kingdom, self policing of the ABPI Code of Practice seems to work quite well, judging by the proportion of complaints submitted by competitor companies.8 Complaints are reviewed by the Prescription Medicines Code of Practice Authority, which acts independently of the ABPI and comprises 12 members from pharmaceutical companies, six independent members, and a legally qualified chairman. Results are published in the Code of Practice Review.

Unlike many other industry organisations, the ABPI also offers guidance on research. It has developed a model clinical trial agreement for industry sponsored research in the NHS and guidance notes for NHS R&D managers.9,10 However, in many other countries industry guidelines relate solely to promotional activities.

Guidance from other organisations

In contrast, many doctors' organisations offer guidance about commercially funded research. The Association of American Medical Colleges has issued two documents entitled Protecting subjects, preserving trust, promoting progress, one aimed at academic institutions and the other at individual clinicians.11,12 These were developed in response to “deepening public concern over researchers' perceived conflicts of interest,” and they aim to set out principles “for the oversight of financial interests in research involving human subjects.”

The American College of Physicians has its own guidelines, first issued in 1990 and extended in 2002, which cover both marketing and research collaboration.13–15 Like the Association of American Medical Colleges, the college offers guidance to both individuals and institutions, including medical societies and institutions involved in medical education. The 1990 American College of Physicians guidelines state that “a useful criterion in determining acceptable activities and relationships is: Would you be willing to have these arrangements generally known?”13

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors strengthened its requirements on declaring conflicts of interest in 2001.16 Since 1999 the US Food and Drug Administration has required companies to supply information about investigators' financial interests when submitting a licensing application.17

Academic institutions have been slow to provide helpful policies on conflict of interest to assist investigators. Cho and colleagues surveyed 100 US institutions and concluded that most policies “lack specificity about the kinds of relationships with industry that are permitted or prohibited” and that such ambiguous policies were likely to cause “unnecessary confusion.”18 Academic institutions have also been criticised for their failure to prevent employees from signing restrictive contracts with companies and their failure to support employees when industrial sponsors threaten legal action to enforce such agreements.19,20

Journal editors, concerned by some well publicised cases of companies attempting to veto publications and suppress unfavourable findings, have tried to strengthen the position of investigators by encouraging greater transparency.16 In September 2001 several members of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors issued a statement entitled Sponsorship, Authorship, and Accountability.16 Although the aim of protecting doctors against unethical and restrictive contracts is laudable, I believe that some of the proposed solutions go too far (and they have also been criticised by others).21 In particular, the demand for “independent” analysis of trials disregards the considerable statistical expertise to be found within the industry.22 The statement also seems confused about the role of contract research organisations in developing protocols. Not all members of the international committee endorsed the statement, and the BMJ published its own, more measured, editorial.23 Despite my reservations, many parts of the statement are helpful, and the greater transparency about company involvement may increase understanding of the complex collaboration that often occurs during trials and also discourage unacceptable practices.

Some organisations for doctors who work directly for pharmaceutical companies (perhaps we could call them professional porcupine dancers) have also produced guidelines. The American Academy of Pharmaceutical Physicians has a Code of Ethics, but it is brief and rather general.24 However, the ethics subcommittee of the Royal College of Physicians Faculty of Pharmaceutical Medicine has issued helpful and detailed guidance on “ethics and pharmaceutical medicine,” which also contains a useful list of other relevant guidelines.25

Most guidelines and regulations reviewed so far cover interactions that arise as a result of marketing or clinical trials. Although journal editors have published their views about company involvement in studies, until very recently no specific guidelines existed to encourage responsible practice for producing publications from trials sponsored by drug companies. However, guidelines on Good Publication Practice for Pharmaceutical Companies have recently been published.26 These encourage companies to publish the results of all clinical trials of licensed products, set out measures designed to prevent publication bias, and, uniquely, address the role of professional medical writers employed by companies to work with doctors to develop publications. The Committee on Publication Ethics has also published guidelines on good publication practice, but these are more general and are designed to assist editors and authors.27

Useful websites

Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry: www.abpi.org.uk

American Academy of Pharmaceutical Physicians: www.aapp.org

American College of Physicians: www.acponline.org

American Medical Association: www.ama-assn.org

Association of American Medical Colleges: www.aamc.org

Australian Medical Association: www.ama.com.au

British Association of Pharmaceutical Physicians: www.brapp.org.uk

Conseil National de l'Ordre des Médecins: www.conseil-national.medecin.fr

Committee on Publication Ethics: www.publicationethics.org.uk

Good Publication Practice for Pharmaceutical Companies: www.gpp-guidelines.org

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors: www.icmje.org

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations: www.ifpma.org

International Federation of Associations of Pharmaceutical Physicians: www.ifapp.org

Medicines Australia: www.medicinesaustralia.com.au

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America: www.phrma.org

World Health Organization: www.who.int

The Office of the Inspector General of the US Department of Health and Human Services has issued guidance to American pharmaceutical manufacturers for developing programmes to ensure that they comply with all the relevant legislation.28 Companies' interactions with doctors may also be influenced by international regulations governing clinical research and local measures to prevent research misconduct.

Conclusions

What can we conclude about regulations designed to choreograph the porcupine dance? Most were developed only recently, and many are still evolving. They come from many organisations with different aims and are therefore scattered and occasionally conflicting, although consensus seems to exist on the broad principles. From my own experience of more than a decade of working closely with the industry and with doctors, misapprehensions and misunderstandings persist on both sides. I would therefore urge proper dialogue between the parties before any more guidelines or regulations are drawn up or revised. Guidelines developed jointly by doctors working both inside and outside the industry might be more widely accepted than those from a single constituency.

Drug companies, like porcupines, come in a range of shapes and sizes; some are fiercer than others, and this diversity must be recognised. The relationships between doctors, academic institutions, pharmaceutical companies, and medical journals will always be complex and interdependent, but we should not forget that the dance has produced some remarkable collaborations that have enabled the discovery and development of the medicines we all rely on.

Competing interests: EW has been an employee of JanssenCilag and GlaxoWellcome. She is now self employed but still works mainly for pharmaceutical companies. She has done one project for the ABPI and also advised on its publication policy. She is a member of the working group that has produced Good Publication Practice for Pharmaceutical Companies and is involved in promoting these guidelines.

References

- 1.Lewis S, Baird P, Evans RG, Ghali WA, Wright CJ, Gibson E, et al. Dancing with the porcupine: rules for governing the university-industry relationship. CMAJ 2001;165: 783-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. ABPI code of practice for the pharmaceutical industry 2001. www.abpi.org.uk/publications/pdfs/CodeOfPractice2001.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 3.Understanding the new Medicines Australia code provisions for healthcare professionals. www.medicinesaustralia.com.au (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 4.Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA code on interactions with healthcare professionals. www.phrma.org/publications/policy//2002-04-19.391.pdf (accessed 26 Apr 2003).

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO criteria for medicinal drug promotion. www.who.int/medicines/library/dap/ethical-criteria/criteriamedicinal.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 6.International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Associations. IFPMA code of pharmaceutical marketing practices. www.ifpma.org/index2.jsp (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 7.Conseil National de l'Ordre des Médecins. Procédures générales d'application de l'article L.4113-6 du code de la santé publique (ex article L.365-1). www.conseil-national.medecin.fr (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 8.Simmonds H. Complaints about advertising of medicines are encouraged. BMJ 2002;324: 850-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Clinical trial agreement for pharmaceutical industry sponsored research in NHS trusts. www.abpi.org.uk/publications/pdfs/Model_Clinical_Trial_Agreement_Final.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 10.Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Guidance for R&D managers in NHS trusts and clinical research departments in the pharmaceutical industry. www.abpi.org.uk/publications/pdfs/GuidanceModelCTA_final_.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2003).

- 11.AAMC Task Force on Financial Conflicts of Interest in Clinical Research. Protecting subjects, preserving trust, promoting progress—policy and guidelines for the oversight of individual financial interests in human subjects research. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2001. www.aamc.org/members/coitf/firstreport.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2003). [PubMed]

- 12.AAMC Task Force on Financial Conflicts of Interest in Clinical Research. Protecting subjects, preserving trust, promoting progress II—policy and guidelines for the oversight of an institution's financial interests in human subjects research. Association of American Medical Colleges, 2002. www.aamc.org/members/coitf/2002coireport.pdf (accessed 25 Apr 2003). [PubMed]

- 13.American College of Physicians. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry. Ann Intern Med 1990;112: 624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyle SL. Physician-industry relations: part 2: organizational issues. Ann Intern Med 2002;136: 403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coyle SL. Physician-industry relations: part 1: individual physicians. Ann Intern Med 2002;136: 396-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidoff F, DeAngelis CD, Drazen JM, Hoey J, Højgaard L, Horton R, et al. Sponsorship, authorship, and accountability. Ann Intern Med 2001;135: 463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josefson D. FDA rules that researchers will have to disclose financial interest. BMJ 1998;316: 493.9501703 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho M, Shohara R, Schissel A, Rennie D. Policies on faculty conflicts of interest at US universities. JAMA 2000;284: 2203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spurgeon D. Report clears researcher who broke drug company agreement. BMJ 2001;323: 1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rennie D. Thyroid storm. JAMA 1997;277: 1238-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korenman SG. The role of journal editors in the responsible conduct of industry-sponsored biomedical research and publication: a view from the other side of the editor's desk. Science Editor 2003;26: 42-3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senn S. Researchers can learn from industry-based reporting standards. BMJ 2000;321: 1016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith R. Maintaining the integrity of the scientific record. BMJ 2001;323: 588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Academy of Pharmaceutical Physicians. Code of ethics. www.aapp.org/ethics.php (accessed 26 Apr 2003).

- 25.Ethical Subcommittee of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Medicine. Guiding principles: ethics and pharmaceutical medicine. Int J Pharm Med 2000;14: 163-71. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wager E, Field EA, Grossman L. Good publication practice for pharmaceutical companies. Curr Med Res Opin 2003;19: 149-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Committee on Publication Ethics. The COPE report 1999. Guidelines on good publication practice. www.publicationethics.org.uk/cope1999/gpp/gpp.phtml#gpp (accessed 10 Aug 2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Office of Inspector General. Compliance program guidance for pharmaceutical manufacturers. oig.hhs.gov/fraud/complianceguidance.html (accessed 8 May 2003).