Abstract

Objective

To investigate the therapeutic and prophylactic use of antibiotics in dentistry in two countries.

Methods

This study used questionnaires to examine the prescribing habits of dentists in Italy (9th country in Europe for systemic antibiotic administration) and Albania an Extra European Union Country. A total of 1300 questionnaires were sent to Italian and Albanian dentists.

Results

In total, 180 Italian and 180 Albanian dentists completed the questionnaire. Penicillin use was higher in Italy (96.6 %) than Albania (82.8 %). Only 26.1 % of Italian dentists and 32 % of Albanian dentists followed the national guidelines for antibiotic administration.

Conclusions

Dentists tend to overprescribe antibiotics for treating existing conditions or as prophylaxis. They also highlighted a lack of adherence to established guidelines for antibiotic use. In addition, factors such as age, nationality, and sex appeared to influence the choice of antibiotics.

Clinical significance

Recently, the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has become a global concern. The authors of this article highlight how dentists often prescribe antibiotics without a real need. Limiting the use of antibiotics in this category may help mitigate antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, Dentistry, Therapeutic antibiotics, Prophylactic antibiotics, Oral infections, Dental antibiotics guideline

1. Introduction

Dentists frequently prescribe antibiotics for preventive and curative purposes. Approximately 10 % of all antibiotic prescriptions were associated with dental infections and these drugs are considered universal solutions for many infectious diseases [1]. Preventive use involves prescribing antibiotics to avoid diseases caused by the transmission of oral flora to distant or locally compromised sites in a vulnerable host [2]. Dentists prescribe medications to manage various oral conditions, particularly orofacial infections, which often originate from odontogenic infections. Furthermore, in 70.6 % of cases, antibiotics were prescribed without surgery [3].

Consequently, prescribing antibiotics has become a significant aspect of dental practice, and antibiotics account for the majority of medicines prescribed by dentists. The prophylactic use of antibiotics is a cause for concern because the practice of using antibiotics for surgical prophylaxis developed before the era of antimicrobial resistance [4]. Italy has among the highest levels of antimicrobial resistance in several bacterial species [5] and ranked ninth in Europe for systemic antibiotic administration in 2017 [6]. The irrational and excessive use of antibiotics is a growing global public health issue. It is widely recognised that overuse or misuse of antibiotics eventually leads to antimicrobial resistance [7,8]. Despite being a normal evolutionary process in microorganisms, resistance is accelerated by the widespread use of antibiotics [9]. This phenomenon has emerged as a grave concern for global health and food security, according to the World Health Organization [10], which recommends the development and implementation of national plans to combat antimicrobial resistance [11]. This phenomenon claimed the lives of approximately 1.27 million individuals worldwide in 2019 and kill still 700.000 people every year [6]. However, this prospect is alarming, with predictions indicating that antimicrobial resistance may cause more than 10 million deaths annually by 2050. This situation is further aggravated by the sluggish pace of developing new antibiotics that cannot match the rapid evolution of antibiotic resistance [12]. According to a systematic review, there is significant misuse of antibiotics for dental diseases in India, both in prophylactic and therapeutic settings, along with a prevalent trend of self-medication by the general population [9]. It is important for dentists, as healthcare professionals responsible for prescribing antibiotics, to recognise the potential role of antibiotics in the development of antibiotic resistance. Alarming data reveals that up to 66 % of antibiotics prescribed in dental settings are not clinically indicated [13]. The use of antibiotics in dentistry is often empirical, leading to the misuse of prophylaxis and antibiotic therapy [7,14].

In view of these considerations, this study aimed to assess, through a questionnaire, the clinical situations in which dentists in Italy and Albania prescribe antibiotics, both for prophylactic and therapeutic purposes, to highlight if clinicians follow the guideline and if there is a overprescription.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and sample selection

This questionnaire was administered in Italy and Albania between February 2023 and June 2023 through an anonymous Google Form platform survey.

To achieve good sample stratification, stricter control, and perhaps a greater responsiveness rate, the subjects were chosen from particular categories. The requirement for inclusion was membership of category associations. The following groups were specifically examined in the present study:

-

•

Dentists working in public and private offices located in Abruzzo (Italy), and members of the “National Association of Italian Dentists” (ANDI- Associazione Nazionale Dentisti Italiani);

-

•

Dentist working in public and private offices located in Tirana (Albania), and members of the “Order of the Albanian Dentist” (USSH- Urdhri I Stomatologut Shqipetar)

Native speakers prepared the same questionnaires in different languages (Italian and Albanian). These two populations were chosen because the numbers of dentists in the Abruzzo and Albanian regions were similar.

The pre-test was conducted with ten subjects, representative of the situation being investigated: The Regional President of ANDI Abruzzo, two associate professors from the faculty of dentistry in Albania, one full professor and six volunteer dentists belonging to the Dental Clinic in Italy University. Early reviews were useful for reducing potential biases and ensuring accurate statistical analyses. The authors made essential changes to the question formulation in response to important feedback obtained from the participants during the pre-test phase. This resulted in greater specificity and the elimination of certain queries. Subsequently, the amended questions were distributed to the same individuals through the ANDI Abruzzo association and the order of the Albanian Dentist. Finally, the questionnaire was also made to be completed by those who performed the pretest.

A sample size calculation was conducted for a power of 80 %, with a sampling error set at 5 %, using a probability proportional to the population size method, resulting in 292 participants (146 per group). Questionnaires were sent to 1300 Italian and 1300 Albanian dentists.

2.2. Questionnaires

Questionnaires were created using Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, California, United States) (Table 6), which allows the construction of customised questionnaires that can later be extrapolated to a spreadsheet. All questionnaires were anonymous.

Table 6.

Antibiotic resistance, climate and diet.

| Antibiotic resistance | Italian | Albanian | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are you aware of antibiotic resistance? | Yes | 100 % | 96.7 % | 0.0135 |

| No | – | 3.3 % | ||

| In your opinion, can climate change be related to antibiotic resistance and overuse? | Yes | 56.9 % | 41.1 % | 0.0051 |

| No | 13.8 % | 23.9 % | ||

| I don't know | 29.3 % | 35 % | ||

| In your opinion, can diet affect antibiotic resistance? | Yes | 70 % | 42.2 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 7.8 % | 22.2 % | ||

| I don't know | 22.2 % | 35.6 % |

Significance for chi-square test, p < 0.05.

The questionnaire (Table 1) consisted of five sections. The first contained a privacy notice in which the dentist must consent to the processing of personal data. The second section investigates independent variables, such as age, gender, nationality, place of work, specialisation, and years of work. The third section deals with the prescription of antibiotics in conjunction with dental diseases, and the frequency and type of antibiotics administered. The fourth section deals with antibiotic prophylaxis, which antibiotics and at what dosage are administered before a particular procedure. The final section contained questions concerning drug resistance.

Table 1.

Questionnaire.

| 1. General aspects | |

| 1. Age | |

| 2. Sex | Male |

| Female | |

| 3. Country | Italy |

| Albania | |

| 4. Degree | Medicine and Surgery, Dentistry |

| Dentistry | |

| 5. Specialisation | Yes |

| No | |

| 6. Which specialisation | Oral surgery |

| Orthodontics | |

| Pedodontics | |

| Clinical Dentistry | |

| Maxillo-facial surgery | |

| 7. Workplace | Private Practice |

| University dental clinic | |

| Hospital | |

| Company | |

| 8. Years of work | <5 |

| 5–10 | |

| 11–20 | |

| 21–30 | |

| >30 | |

| 2. Antibiotic therapy | |

| 1. Which of these classes of antibiotics is your first choice for antibiotic therapy? | Penicillins |

| Macrolides | |

| Cephalosporins | |

| Fluoroquinolones | |

| 2. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for an acute apical abscess? | Yes |

| No | |

| 3. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for a chronic apical abscess? | Yes |

| No | |

| 4. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for pericoronitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 5. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for necrotising periodontal disease? | Yes |

| No | |

| 6. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for symptomatic irreversible pulpitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 7. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic periapical periodontitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 8. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for dry alveolitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 9. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for chronic periodontal disease? | Yes |

| No | |

| 10. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for a periodontal abscess? | Yes |

| No | |

| 11. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for necrotising ulcerative stomatitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 12. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for gingivitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 13. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for reversible pulpitis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 14. Do you assess plaque control before the antibiotic is prescribed? | Yes |

| No | |

| 15. Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy in patients with peri-implantitis? | Yes No |

| 16. Do you follow any national guidelines for antibiotic prescription in dentistry? | Yes |

| No | |

| I am not aware of any guidelines regarding antibiotic therapy in dentistry | |

| 3. Prophylaxis prescription | |

| 1. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients at risk of bacterial endocarditis? | Yes |

| No | |

| 1a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 2. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo extraction of the third non-impacted molar? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 2a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 3. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo semi-impacted third molar extraction? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 3a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 4. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo third molar extraction inclusive? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 4a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 5. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo single dental implant placement (n = 1) ? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 5a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 6. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo dental implant placement (n > 1) ? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 6a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 7. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing hard tissue augmentation (GBR) ? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 7a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 8. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who have to undergo mucogingival surgery? | Yes |

| No | |

| I do not perform this surgery | |

| 8a. If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose |

|

| 4. Antibiotic resistance | |

| 1. Are you aware of antibiotic resistance? | Yes |

| No | |

| I don't know | |

| 2. In your opinion, can climate change be related to antibiotic resistance and overuse? | Yes |

| No | |

| I don't know | |

| 3. In your opinion, can diet affect antibiotic resistance? | Yes |

| No | |

| I don't know | |

2.3. Variables and their definitions

The primary dependent variable in this study was the overall prescription quality, which was determined based on responses to 14 different clinical scenarios of antibiotic administration in the third part of the questionnaire. In each scenario, participants were asked whether they would prescribe antibiotics. The appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions was assessed according to the WHO Access, Watch, Reserve Antibiotic Book” (AWaRe) [15], a globally recognised reference guide at the time of the study.

The second dependent variable was the prophylactic administration of antibiotics. Dentists were asked whether they would administer antibiotics before different surgical procedures.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data processing and analysis included statistical methodologies focusing on frequency distribution within the unaltered data analysis. Given the nature of our survey, we calculated descriptive statistics for most of the questions. Each question involved determining the percentage of respondents who provided a specific answer by considering the total number of responses to that question. Along with descriptive statistics, we used the chi-square test to assess the association between dichotomous variables. The data were organised in a 2 × 2 contingency table, and the chi-square value was calculated by comparison at a significance level of p < 0.05. Multiple logistic regression was used to assess the effects of several independent variables on categorical dependent variables. All statistical comparisons were conducted at a significance level of p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were executed using GraphPad version 8 (GraphPad Software, 2365 Northsides Dr. Suite 560, San Diego, CA 92108, USA), a software package specifically designed for statistical analysis and Microsoft Excell (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, United States) for descriptive statistic.

2.5. Ethical consideration

Prior to the survey, all participants completed the first section of the survey to provide informed consent in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the EU General Data Protection Regulation GDPR (UE) n. 2016/679 for Italy and the Data Protection Act 9887/2008 for Albania. On January 20, 2023, the Ethical committee of the University in Albania approved the study protocol. To ensure complete anonymity, the survey was designed such that the identification of respondents based on their responses was impossible. Furthermore, the participants were fully informed about the nature of the study and voluntarily chose to participate.

3. Results

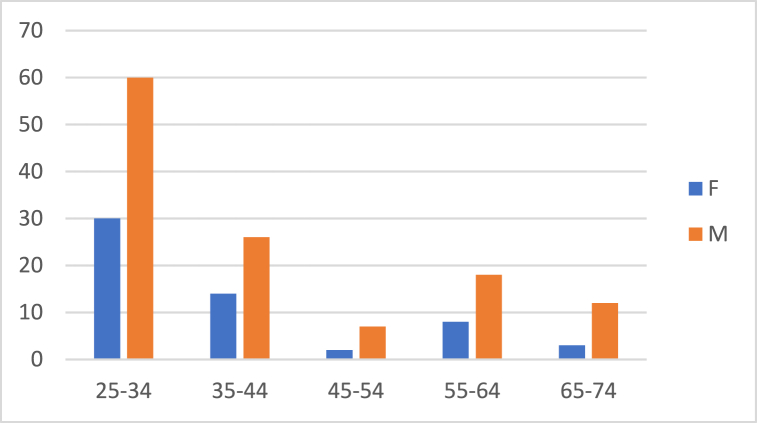

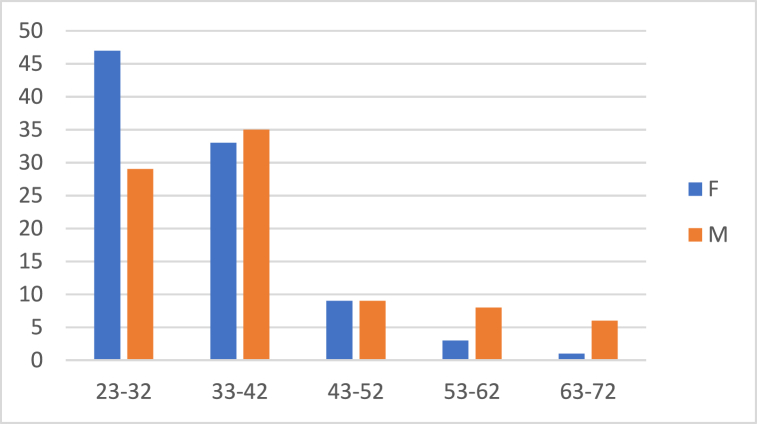

A total of 180 Italian and 180 Albanian dentists completed the questionnaires. Table 2 shows the demographic data obtained from the questionnaires administered to dentists. In Italy, 123 participants (68.3 %) were male and 57 (31.7 %) were female aged between 25 and 68 years. In Albania, 87 (48.3 %) dentists were male and 93 (51.7 %) were female and aged 23–68 years. Fig. 1, Fig. 2 show the sex distributions according to age group of Italian and Albanian dentists (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic data distribution.

| Demographic Data | N | Italian | N | Albanian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age | 39.53 | 36.08 | |||

| Sex | Male | 124 | 68.3 % | 89 | 48.3 % |

| Female | 57 | 31.7 % | 91 | 51.7 % | |

| Bachelor | Medicine and Dentistry | 20 | 10 % | 8 | 5 % |

| Dentistry | 160 | 90 % | 172 | 95 % | |

| Specialisation | Yes | 88 | 48.9 % | 68 | 37.8 % |

| No | 92 | 51.1 % | 112 | 62.2 % | |

| If yes, please state which one | Oral surgery | 52 | 60 % | 34 | 50 % |

| Orthodontics | 25 | 27.8 % | 17 | 25.5 % | |

| Paediatric Dentistry | 11 | 12.2 % | 16 | 24.5 % | |

| Workplace | Private practice | 174 | 69 % | 135 | 75 % |

| University dental clinic | 37 | 27 % | 36 | 20 % | |

| Hospital | 5 | 3 % | 5 | 3 % | |

| Health insurance | 2 | 1 % | 4 | 2 % | |

| Years of practice | <5 | 55 | 30.6 % | 58 | 30 % |

| 5–10 | 61 | 33.9 % | 53 | 29.4 % | |

| 11–20 | 24 | 13.3 % | 48 | 26.7 % | |

| 21–30 | 22 | 12.2 % | 15 | 9.4 % | |

| >30 | 18 | 10 % | 6 | 4.4 % |

Fig. 1.

Gender distribution according to age groups in Italian dentists.

Fig. 2.

Gender distribution according to age groups in Albanian dentists.

Table 3 shows the responses of Italian and Albanian dentists to the therapeutic administration of antibiotics to patients with different pathologies. Interestingly, for all answers, there was a statistically significant difference in the administration of antibiotics between the Italian and Albanian dentists. Furthermore, the results show that in Italy, there is still a predominant use of penicillin (96.6 %), whereas in Albania, there is greater diversification of antibiotics. Furthermore, we can see that rightly for gingivitis (Italian: 0.6 %, Albanian: 10 %) and reversible pulpitis (Italian: 11 %, Albanian: 27.2 %) there is a low rate of antibiotic administration, clinical situations where antibiotic administration is not required. However, it can be seen that in Albania there is a higher antibiotic uptake in gingivitis and reversible pulpitis. Regarding periodontal abscesses, 80 % of dentists in Albania tended to administer antibiotic therapy compared with 47.5 % of Italian dentists (Table 3).

Table 3.

Responses to the administration of antibiotics for therapeutic use.

| Therapy administration | Italian | Albanian | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Which of these classes of antibiotics is your first choice for antibiotic therapy? | Penicillins | 96.6 % | 82.8 % | 0.0003a |

| Macrolides | 4.4 % | 6.7 % | ||

| Cephalosporins | – | 8.3 % | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | – | 2.2 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for an acute apical abscess? | Yes | 96.7 % | 84.4 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 3.3 % | 15.6 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for a chronic apical abscess? | Yes | 33.5 % | 61.5 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 66.5 % | 38.5 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for pericoronitis? | Yes | 84 % | 65 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 16 % | 35 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for necrotising periodontal disease? | Yes | 90.6 % | 72.2 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 9.4 % | 27.8 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for symptomatic irreversible pulpitis? | Yes | 44.2 % | 32.2 % | 0.0298a |

| No | 55.8 % | 67.8 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for asymptomatic periapical periodontitis? | Yes | 19.9 % | 35 % | 0.0013a |

| No | 80.1 % | 65 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for dry alveolitis? | Yes | 85.1 % | 68.9 % | 0.0004a |

| No | 14.9 % | 31.1 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for chronic periodontal disease? | Yes | 6.1 % | 22.8 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 93.9 % | 77.2 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for a periodontal abscess? | Yes | 47.5 % | 80 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 52.5 % | 20 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for necrotising ulcerative stomatitis? | Yes | 89.5 % | 69.4 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 10.5 % | 30.6 % | ||

| .Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for gingivitis? | Yes | 0.6 % 99.4 % |

10 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 90 % | |||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy for reversible pulpitis? | Yes | 11 % | 27.2 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 89 % | 72.8 % | ||

| Do you assess plaque control before the antibiotic is prescribed? | Yes | 25.4 % | 58.9 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 74.6 % | 41.1 % | ||

| Do you prescribe antibiotic therapy in patients with peri-implantitis? | Yes | 84.1 % | 73.1 % | 0.0129a |

| No | 15.9 % | 26.9 % | ||

| Do you follow any national guidelines for antibiotic prescription in dentistry | Yes | 26.1 % | 32 % | 0.0008a |

| No | 38.1 % | 21.3 % | ||

| I am not aware of any guidelines regarding antibiotic therapy in dentistry | 35.8 % | 46.6 % |

Significance for chi-square test, p < 0.05.

Table 4 shows the results of the multiple logistic regression assessing the relationship between various dental diseases and dentists' antibiotic prescription patterns, considering parameters such as nationality, sex, specialty, and age. It is noteworthy that the age of the dentist affects the choice of antibiotic administration according to pathology, as an Odds Ratio (OR) > 1 can be observed, except for some diseases where there seems to be no correlation (apical acute abscess and necrotising ulcerative stomatitis). Nationality seemed to influence the choice of antibiotic administration for diseases such as acute apical abscess (OR: 5.424; CI: 2.147–16.30), pericoronitis (OR: 2.205; CI: 1.293–3.819), dry alveolitis (OR: 2.111; CI: 1.213–3.740) and necrotising ulcerative stomatitis (OR: 4.079; CI: 2.179–8.034). Sex is also significant for antibiotic administration; it does not seem to be crucial for chronic periodontitis alone (OR: 0.6838; CI: 0.351–1.323) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression of antibiotic therapeutic administration: odds ratio (95 % CI); In bold statistical significance p value < 0.001.

| Country | Gender | No Specialisation | Oral Surgery | Pedodontics | Orthodontics | Age in years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95 % CI) | |||||||

| Apical Acute Abscess | 5.424 (2.147–16.30) | 1.713 (0.7789–3.846) | 1.531 (0.2795–10.38) | 1.467 (0.2693–10.43) | 0.7087 (0.1063–5.984) | 2.181 (0.3660–17.05) | 0.9939 (0.9617–1.030) |

| Chronic apical abscess | 0.273 (0.1666–0.443) | 1.654 (1.024–2.699) | 2.044 (0.6764–6.517) | 1.408 (0.4614–4.535) | 1.361 (0.4435–4.151) | 1.740 (0.5846–5.410) | 1.016 (0.9972–1.036) |

| Pericoronitis | 2.205 (1.293–3.819) | 1.088 (0.6331–1.857) | 1.653 (0.4431–7.131) | 1.639 (0.440–7.169) | 4.673 (1.116–25.85) | 1.424 (0.3265–6.738) | 1.027 (1.003–1.053) |

| Necrotising periodontal disease | 3.355 (1.728–6.880) | 1877 (1.032–3.443) | 0.3246 (0.081–1.240) | 0.4484 (0.1152–1.726) | 0.7028 (0.1858–2.810) | 0.2554 (0.057–1.013) | 1.023 (0.9954–1.055) |

| Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis | 1.395 (0.8676–2.247) | 1.578 (0.9746–2.573) | 1.213 (0.3924–3.771) | 1.216 (0.3881–3.797) | 0.8488 (0.2752–2.645) | 1.690 (0.5662–5.248) | 1.031 (1.013–1.051) |

| Asymptomatic periapical periodontitis | 0.2678 (0.147–0.471) | 2.168 (1.256–3.808) | 2.824 (0.819–10.04) | 1.404 (0.4041–4.927) | 2.211 (0.6006–8.248) | 1.872 (0.5241–7.039) | 1.049 (1.028–1.072) |

| Dry alveolitis | 2.111 (1.213–3.740) | 1.391 (0.8078–2.391) | 1.776 (0.4919–7.337) | 2.456 (0.6720–10.50) | 1.470 (0.3965–6.013) | 2.165 (0.6030–8.486) | 1.009 (0.9862–1.033) |

| Chronic periodontal disease | 0.1907 (0.080–0.409) | 0.6838 (0.351–1.323) | 1.817 (0.425–7.327) | 1.334 (0.3046–5.263) | 2.566 (0.5442–11.59) | 1.361 (0.3089–5.896) | 1.015 (0.986–1.043) |

| Periodontal abscess | 0.2051 (0.119–0.343) | 1.054 (0.628–1.771) | 6.030 (1.583–26.38) | 3.770 (0.975–16.94) | 1.512 (0.4113–5.352) | 4.640 (1.439–16.52) | 1.019 (0.9985–1.040) |

| Necrotising ulcerative stomatitis | 4.079 (2.179–8.034) | 1.412 (0.793–2.518) | 0.6073 (0.172–2.107) | 0.4562 (0.1294–1.608) | 0.6133 (0.1722–2.262) | 0.4151 (0.1097–1.482) | 0.9959 (0.972–1.021) |

| Reversible pulpitis | 0.257 (0.1325–0.479) | 2.586 (1.369–5.066) | 0.845 (0.1501–3.998) | 0.5067 (0.088–2.345) | 0.5067 (0.008–1.252) | 0.844 (0.115–5.438) | 1.030 (1.006–1.054) |

Table 5 summarises antibiotic prophylaxis in different surgical procedures. Italian dentists tended to prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients at risk of bacterial endocarditis. (100 %), whereas 88.8 % of patients were administered antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the evening before), unlike Albanian dentists, where 94.4 % tended to administer antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with risk of bacterial endocarditis and 21 % of dentists preferred short therapy.

Table 5.

Antibiotic prophylaxis by Italian and Albanian dentists.

| Antibiotic Prophylaxis | Italian | Albanian | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients at risk of bacterial endocarditis? | Yes | 100 % | 94.4 % | <0,0017a |

| No | – | 5.6 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 10 % | 21 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 1.5 % | 11 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 88.5 % | 68 % | ||

| 2. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo extraction of the third non-impacted molar? | Yes | 81.2 % | 42.8 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 14.9 % | 40 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 3.9 % | 17.2 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 15 % | 12.5 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 50 % | 7.5 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 35 % | 80 % | ||

| 3. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo semi-impacted third molar extraction? | Yes | 87.8 % | 55 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 6.1 % | 30 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 6.1 % | 15 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 22.8 % | 15 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 39.9 % | 5 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 37.3 % | 80 % | ||

| 4. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo third molar extraction impacted? | Yes | 87.8 % | 69.4 % | <0.0001a |

| No | 3.3 % | 16.1 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 8.8 % | 14.4 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 21 % | 13 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 4.5 % | 27 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 74.5 % | 60 % | ||

| 5. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo single dental implant placement (n = 1) ? | Yes | 75.7 % | 66.1 % | 0,0585 |

| No | 5 % | 10.6 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 19.3 | 23.3 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 24.1 % | 17 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 5.1 % | 3 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 70.8 % | 80 % | ||

| 6. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who are to undergo dental implant placement (n > 1) ? | Yes | 75.1 % | 69.4 % | 0.1513 |

| No | 3.3 % | 7.8 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 21.5 % | 22.8 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 5.8 % | 10 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 2.2 % | 5 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 92 % | 85 % | ||

| 7. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing hard tissue augmentation (GBR) ? | Yes | 66.9 % | 58.3 % | 0.0789 |

| No | 2.2 % | 6.1 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 30.9 % | 35.6 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 5.8 % | 9 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | – | 1 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 94.2 % | 90 % | ||

| 8. Do you prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis in patients who have to undergo mucogingival surgery? | Yes | 63 % | 49.4 % | 0.0079a |

| No | 5 % | 12.3 % | ||

| I do not perform this surgery | 32 % | 38.3 % | ||

| If yes, please indicate which therapy you choose | Short: 1 h before surgery and every 8 h after surgery until the first 24 h are covered | 0.9 % | 16.1 % | |

| Ultrashort: administration 1 h before surgery | 3.5 % | 2.2 % | ||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before | 95.6 % | 81.7 % |

Significance for chi-square test, p < 0.05.

There was no statistically significant difference with regard to more complex surgical interventions such as hard tissue augmentation (p < 0.0789). There was a significant difference with regard to less invasive interventions, such as extraction of the third molar, which was not impacted (p < 0.0001), semi-impacted (p < 0.0001), and totally impacted (p < 0.0001). Regarding implant placement, Italian and Albanian dentists tended to administer antibiotics prophylactically for both single and multiple implants. There were no statistically significant differences between the two populations for antibiotic administration in single (p < 0.0585) and multiple (p < 0.1513) implants. In addition, there was a preference for the administration of amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before) for both single (Italian: 70.8 %, Albanian: 80 %) and multiple implants (Italian: 92 %, Albanian: 85 %) (Table 5).

Table 6 shows the responses of Italian and Albanian dentists to antibiotic resistance. There were no significant differences in antibiotic resistance (p < 0.0135) or climate change (p < 0.0051). However, there was a significant difference in nutritional status (p < 0.0001) (Table 6).

4. Discussion

To date, millions of lives have been saved thanks to the use of antibiotics, although in recent years their inappropriate and reckless use has fuelled the emergence of antibiotic resistance [16]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, dental care was severely restricted leading to an increase in antibiotic prescriptions by dentists [17]. In fact, it is estimated that dentists prescribe between 7 % and 11 % of all antibiotics for therapeutic and prophylactic reasons [18]. Our questionnaire revealed that both Italian and Albanian dentists tended to abuse antibiotics for both therapeutic and prophylactic purposes. The appropriateness of prescribing antibiotic therapy was assessed according to the “WHO Access, Watch, Reserve Antibiotic Book [15], a globally recognised reference guide at the time of the study that states that only certain conditions require antibiotic therapy. Patients with gingivitis, periodontitis, dry alveolitis, or reversible pulpitis did not require antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, the questionnaire showed that antibiotic therapy is also used for these conditions (Table 3), except in Italy for gingivitis, where only 0.6 % of dentists prescribed antibiotics (Table 3). The questionnaire shows that dentists in Italy and Albania prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis for patients at risk of bacterial endocarditis. However, a Cochrane review pointed out that to date there is still no evidence on the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the risk of bacterial endocarditis following invasive dental procedures [19]. A periodontal abscess is also a condition that does not require antibiotic therapy as it can be drained by cleaning the periodontal pocket or eradicated by extraction of the tooth, although some studies suggest the use of antibiotic therapy if systemic problems occur [20]. This shows how, unfortunately, antibiotics are still abused for conditions that do not require them. However, the AWaRe mentions the conditions in which antibiotic therapy is indicated. Conditions such as abscesses, pericoronitis, necrotising ulcerative stomatitis, and necrotising periodontal disease require antibiotic therapy to prevent systemic complications. Antibiotics are indicated for the treatment of acute dental abscesses [21] as they can spread the infection throughout the body. Our data showed that 96.7 % of Italian and 84.4 % of Albanian dentists prescribed antibiotic therapy for abscesses. These data are in agreement with a study by Loume et al. where an 89.1 % administration rate was observed for acute abscesses [22]. Pericoronitis affects 4.92 % of people, and 95 % of cases involve the lower third molar [23]. Our results show that 84 % of Italian dentists and 65 % of Albanian dentists prescribe antibiotic therapy, in agreement with a review in which 74 % of dentists prescribed it, although the authors state that it should only be used in cases of severe pericoronitis with systemic involvement [24]. No specific drug prescription protocol exists [25]. In our questionnaire, 84.1 % of Italian and 73.1 % of Albanian dentists administered antibiotics for periimplantitis. However, AWaRe's book provides no indication for antibiotic treatment for this clinical condition. A recent review states that there is still no specific antibiotic protocol for the treatment of periimplantitis, but the systemic use of metronidazole plus ultrasonic debridement may improve non-surgical treatment [26]. However, De Waal et al. affirm that amoxicillin + metronidazole systemic antibiotic therapy does not improve clinical or microbiological outcomes of non-surgical peri-implantitis treatment and should not be used frequently [27].

The results of our questionnaire showed that both Italian and Albanian dentists often prescribed amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for wisdom tooth extractions. These results are consistent with those of a literature review that revealed that penicillin, with or without the addition of clavulanic acid, are the most commonly used class of antibiotics for the extraction of wisdom teeth. However, the authors concluded that the administration of penicillin as a preventive measure to avoid infections during wisdom tooth extraction may be more harmful than beneficial to patients [28]. In fact, even a Cochrane review points out that there is low evidence on the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing dry alveoloitis or infection after third molar removal when compared with a placebo, stating that treating 19 patients with antibiotic therapy could prevent a single person from becoming infected. However, the authors caution clinicians, stating that antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered by carefully assessing the general health status of patients [29]. Some studies have demonstrated the non-superiority of antibiotic administration for implant placement, where 2 g of amoxicillin before implant placement is of limited benefit and should be avoided in most cases [30]. On the other hand, the results of a meta-analysis show how a single dose of pre-operative antibiotic can reduce the occurrence of implant failure [31]. There is no contemporary evidence to support routine prescription of antibiotics to healthy patients for surgical procedures carried out on healthy tissues, such as placement of dental implants or removal of unerupted third molars, as the available double-blind randomised controlled trials do not demonstrate any improvement in clinical outcomes [32]. Our questionnaire also showed that the more invasive the interventions, the more likely there was a tendency to prescribe antibiotics at a higher dose. In fact, in guided bone regeneration, both Italian and Albanian dentists administer antibiotic prophylaxis with “Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid:1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before” (Italian: 94.2 %, Albanian: 90 %). However, a recent review has shown that 2–3 g of amoxicillin before surgery is sufficient to both reduce implant failure and decrease the bacterial load in grafted bone particles [33]. The same applies to mucogingival surgery, with both Italian (63 %) and Albanian (43.4 %) dentists prescribing antibiotics, mostly “amoxicillin + clavulanic acid: 1 g every 12 h for 6 days starting the night before” (Italian: 95.6 %, Albanian: 81.7 %). It can also be seen from the questionnaire that most dentists tend to prescribe amoxicillin + clavulanic acid. In fact, it was seen that this is more widely used in many countries although it has more side effects, especially gastrointestinal, than amoxicillin alone [34]. A review of the most frequently used antibiotics by dentists states that the combination of amoxicillin + clavulanic acid should be used in severe cases of odontogenic infection such as abscesses and pulpitis, however considering the side effects such as hepatotoxicity and alteration of the normal gastrointestinal microbiota [21].

Another important aspect to note from the questionnaire was that only a limited percentage of dentists followed the guidelines for antibiotic administration in dentistry. Similar results have also been reported by other authors [[35], [36], [37]]. Hence, there is a need to disseminate national guidelines widely. Other factors, such as experience and working environment, may worsen the quality of the prescription. These results may be useful in implementing dental education [38] Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are increasing and threaten public health. Therefore, prescribers are responsible for limiting antibiotic use of antibiotics [39,40]. Moreover, it should be emphasized that there is a lack of clear and specific guidelines for each dental condition. In fact, a study revealed that out of 6 antibiotic prescriptions, 5 did not follow the guidelines [41]. Furthermore, it is highlighted that not only in Italy and Albania is there an overdose of antibiotics. In fact, a study revealed how dentists in Turkey also overprescribe antibiotics. The authors emphasise the importance of continuous education on the rational use of antibiotics to educate the dentist in their administration [42].

4.1. Strenghts

The major strength of our article was to highlight an alarming situation regarding prophylactic and therapeutic antibiotic prescription for dental conditions. Clinicians do not follow guidelines and prescribe antibiotics even for conditions where they are not needed. 38.1 % of the clinicians in italy and 21.3 % in albania do not follow the guidelines, even 35.8 % in italy and 46.6 % in albania are not aware of the existence of guidelines concerning the administration of antibiotics in dentistry. it is necessary for all clinicians to be educated on the use of antibiotics in order to decrease the occurrence of antibiotic resistance and there is a need for greater visibility of the guidelines so that they are easily available and consultable, both for the clinician and the patient.

4.2. Limits

Certainly, the low response rate from clinicians in both Italy and Albania is a limitation of our study. Unfortunately, although 1300 questionnaires were sent out in both Italy and Albania, only 180 clinicians per country had time to answer the questionnaire. Perhaps a higher response rate would have given more emphasis to this important topic. A second limitation is also the different continuing education that exists between the two countries. In Italy, clinicians, in order to practise, are obliged to attend refresher courses in order to obtain training credits that guarantee constant updating. This obligation does not exist in Albania.

5. Conclusions

From our perspective, dentists, as professionals, often tend to prescribe more antibiotics than necessary for therapeutic purposes. This inclination has the potential to contribute to the spread of drug resistance which is an urgent concern for the medical community. To address this issue, healthcare providers must exercise caution when administering antibiotics to prevent the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. Evaluating each patient's needs and considering alternative treatments when appropriate, dentists play a vital role in addressing this problem and promoting appropriate antibiotic usage.

Therefore, dentists should exercise caution in prescription practices. Antibiotics should be prescribed only when there was a medical need. Following national guidelines, exercising judgment, and limiting the use of antibiotics to cases where they are truly essential, dentists can help mitigate the growing threat of antibiotic resistance.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Union-NextGeneration EU under the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) National Innovation Ecosystem grant ECS00000041 -VITALITY -CUP D73C22000840006.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Bruna Sinjari], upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Eugenio Manciocchi: Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Edit Xhajanka: Conceptualization. Gianmaria D'Addazio: Formal analysis, Data curation. Giuseppe Tafuri: Visualization, Software. Manlio Santilli: Visualization, Software, Investigation. Imena Rexhepi: Investigation. Sergio Caputi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Bruna Sinjari: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Bruna Sinjari reports financial support was provided by European Union-NextGeneration EU. Bruna Sinjari reports a relationship with European Union-NextGeneration EU that includes: funding grants. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Eugenio Manciocchi, Email: eugenio.manciocchi@unich.it.

Edit Xhajanka, Email: edit.xhajanka@umed.edu.al.

Gianmaria D'Addazio, Email: gianmariadaddazio@unich.it.

Giuseppe Tafuri, Email: giuseppe.tafuri@unich.it.

Manlio Santilli, Email: manlio.santilli@unich.it.

Imena Rexhepi, Email: imena.rexhepi@unich.it.

Sergio Caputi, Email: scaputi@unich.it.

Bruna Sinjari, Email: b.sinjari@unich.it.

References

- 1.Jenny A., Nagar P., Raghunath V.N., Lakhotia R.K.F.N., Ninawe N. Prescription pattern of antibiotics among general dental practitioners in Karnataka—a cross-sectional survey. Dental Journal of Advance Studies. 2022;10:9–14. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1748164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberoi S.S., Dhingra C., Sharma G., Sardana D. Antibiotics in dental practice: how justified are we. Int. Dent. J. 2015;65:4–10. doi: 10.1111/idj.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cope A.L., Francis N.A., Wood F., Chestnutt I.G. Antibiotic prescribing in UK general dental practice: a cross-sectional study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:145–153. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh L., Ford P., McGuire T., Driel M., Hollingworth S. Trends in Australian dental prescribing of antibiotics: 2005–2016. Aust. Dent. J. 2021;66 doi: 10.1111/adj.12846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prigitano A., Romanò L., Auxilia F., Castaldi S., Tortorano A.M. Antibiotic resistance: Italian awareness survey 2016. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Home | AMR Review Available online: https://amr-review.org/(accessed on 22 August 2023). 1 (2016) 1-2.

- 7.Koyuncuoglu C.Z., Aydin M., Kirmizi N.I., Aydin V., Aksoy M., Isli F., Akici A. Rational use of medicine in dentistry: do dentists prescribe antibiotics in appropriate indications? Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017;73:1027–1032. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padovani M., Bertelli A., Corbellini S., Piccinelli G., Gurrieri F., De Francesco M.A. In vitro activity of cefiderocol on multiresistant bacterial strains and genomic analysis of two cefiderocol resistant strains. Antibiotics. 2023;12:785. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12040785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhuvaraghan A., King R., Larvin H., Aggarwal V.R. Antibiotic use and misuse in dentistry in India—a systematic review. Antibiotics. 2021;10:1459. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10121459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. ISBN 978-92-4-150976-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally Final report and recommendations/the review on antimicrobial resistance chaired by jim O'neill. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/thvwsuba Available online:

- 12.Ahmed I., King R., Akter S., Akter R., Aggarwal V.R. Determinants of antibiotic self-medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukumar S., Martin F., Hughes T., Adler C. Think before you prescribe: how dentistry contributes to antibiotic resistance. Aust. Dent. J. 2020;65:21–29. doi: 10.1111/adj.12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bianco A., Cautela V., Napolitano F., Licata F., Pavia M. Appropriateness of antibiotic prescription for prophylactic purposes among Italian dental practitioners: results from a cross-sectional study. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;10:547. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The WHO AWaRe (access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240062382 Available online:

- 16.Vardhan Th, Lakhshmi Nv, Haritha B. Exploring the pattern of antibiotic prescription by dentists: a questionnaire-based study. J NTR Univ Health Sci. 2017;6:149. doi: 10.4103/JDRNTRUHS.JDRNTRUHS_30_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah S., Wordley V., Thompson W. How did COVID-19 impact on dental antibiotic prescribing across england? Br. Dent. J. 2020;229:601–604. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-2336-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badran A.S., Keraa K., Farghaly M.M. Applying the kirkpatrick model to evaluate dental students' experience of learning about antibiotics use and resistance. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022;26:756–766. doi: 10.1111/eje.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutherford S.J., Glenny A.-M., Roberts G., Hooper L., Worthington H.V. Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing bacterial endocarditis following dental procedures. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd003813.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slots J. Research, science and therapy committee systemic antibiotics in periodontics. J. Periodontol. 2004;75:1553–1565. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.11.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmadi H., Ebrahimi A., Ahmadi F. Antibiotic therapy in dentistry. Int J Dent. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6667624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loume A., Gardelis P., Zekeridou A., Giannopoulou C. Vol. 133. Swiss Dent J; 2023. (A Survey on Systemic Antibiotic Prescription Among Dentists in Romandy). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katsarou T., Kapsalas A., Souliou C., Stefaniotis T., Kalyvas D. Pericoronitis: a clinical and epidemiological study in Greek military recruits. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11:e133–e137. doi: 10.4317/jced.55383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt J., Kunderova M., Pilbauerova N., Kapitan M. A review of evidence-based recommendations for pericoronitis management and a systematic review of antibiotic prescribing for pericoronitis among dentists: inappropriate pericoronitis treatment is a critical factor of antibiotic overuse in dentistry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18:6796. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roccuzzo M., Layton D.M., Roccuzzo A., Heitz-Mayfield L.J. Clinical outcomes of peri-implantitis treatment and supportive care: a systematic review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(Suppl 16):331–350. doi: 10.1111/clr.13287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feres M., Martins R., Souza J.G.S., Bertolini M., Barão V.A.R., Shibli J.A. Unraveling the effectiveness of antibiotics for peri-implantitis treatment: a scoping review. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2023;25:767–781. doi: 10.1111/cid.13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Waal Y.C.M., Vangsted T.E., Van Winkelhoff A.J. Systemic antibiotic therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical peri-implantitis treatment: a single-blind rct. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021;48:996–1006. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sologova D., Diachkova E., Gor I., Sologova S., Grigorevskikh E., Arazashvili L., Petruk P., Tarasenko S. Antibiotics efficiency in the infection complications prevention after third molar extraction: a systematic review. Dent. J. 2022;10:72. doi: 10.3390/dj10040072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodi G., Azzi L., Varoni E.M., Pentenero M., Fabbro M.D., Carrassi A., Sardella A., Manfredi M. Antibiotics to prevent complications following tooth extractions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003811.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Momand P., Becktor J.P., Naimi‐Akbar A., Tobin G., Götrick B. Effect of antibiotic prophylaxis in dental implant surgery: a multicenter placebo‐controlled double‐blinded randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2022;24:116–124. doi: 10.1111/cid.13068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim A., Abdelhay N., Levin L., Walters J.D., Gibson M.P. Antibiotic prophylaxis for implant placement: a systematic review of effects on reduction of implant failure. Br. Dent. J. 2020;228:943–951. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1649-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J., Tennant M., Walsh L., Kruger E. Is there a consensus on antibiotic usage for dental implant placement in healthy patients? Aust. Dent. J. 2018;63:25–33. doi: 10.1111/adj.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salgado-Peralvo A.-O., Mateos-Moreno M.-V., Velasco-Ortega E., Peña-Cardelles J.-F., Kewalramani N. Preventive antibiotic therapy in bone augmentation procedures in oral implantology: a systematic review. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2022;123:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huttner A., Bielicki J., Clements M.N., Frimodt-Møller N., Muller A.E., Paccaud J.-P., Mouton J.W. Oral amoxicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid: properties, indications and usage. Clin. Microbiol. Infection. 2020;26:871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford P.J., Saladine C., Zhang K., Hollingworth S.A. Prescribing patterns of dental practitioners in Australia from 2001 to 2012. Antimicrobials. Aust. Dent. J. 2017;62:52–57. doi: 10.1111/adj.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teoh L., Stewart K., Marino R.J., McCullough M.J. Part 2. Current prescribing trends of dental non-antibacterial medicines in Australia from 2013 to 2016. Aust. Dent. J. 2018 doi: 10.1111/adj.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollingworth S.A., Chan R., Pham J., Shi S., Ford P.J. Prescribing patterns of analgesics and other medicines by dental practitioners in Australia from 2001 to 2012. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45:303–309. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodríguez-Fernández A., Vázquez-Cancela O., Piñeiro-Lamas M., Herdeiro M.T., Figueiras A., Zapata-Cachafeiro M. Magnitude and determinants of inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in dentistry: a nation-wide study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2023;12:20. doi: 10.1186/s13756-023-01225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teoh L., Marino R.J., Stewart K., McCullough M.J. A survey of prescribing practices by general dentists in Australia. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:193. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelfusa M., Murari A., Ludovici G.M., Franchi C., Gelfusa C., Malizia A., Gaudio P., Farinelli G., Panella G., Gargiulo C., et al. On the potential of relational databases for the detection of clusters of infection and antibiotic resistance patterns. Antibiotics. 2023;12:784. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12040784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suda, K.J.; Fitzpatrick, M.A.; Gibson, G.; Jurasic, M.M.; Poggensee, L.; Echevarria, K.; Hubbard, C.C.; McGregor, J.C.; Evans, C.T Antibiotic prophylaxis prescriptions prior to dental visits in the veterans' health administration (VHA), 2015–2019. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 43, 1565–1574, doi:10.1017/ice.2021.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Aydin M., Koyuncuoglu C.Z., Kirmizi I., Isli F., Aksoy M., Alkan A., Akici A. Pattern of antibiotic prescriptions in dentistry in Turkey: population based data from the prescription information system. Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology. 2019;1:62–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Bruna Sinjari], upon reasonable request.