Abstract

Advances in the treatment of older women with early-stage breast cancer, par ticularly oppor tunities for de-escalation of therapy, have afforded patients and providers opportunity to individualize care. As the majority of women ≥65 have estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative disease, locoregional therapy (surgery and/or radiation) may be tailored based on a patient’s physiologic age to avoid either over- or undertreatment. To determine who would derive benefit from more or less intensive therapy, an accurate assessment of an older patient’s physiologic age and incorporation of patient-specific values are paramount. While there now exist well-validated ger iatr ic assessment tools whose use is encouraged by the American Society of Clinical Oncology when considering systemic therapy, these instruments have not been widely integrated into the locoregional breast cancer care model. This review aims to highlight the importance of assessing frailty and the concepts of and over- and undertreatment, in the context of trial data supporting opportunities for safe deescalation of locoregional therapy, when treating older women with early-stage breast cancer.

Keywords: Frailty, Geriatric assessment, Life expectancy, Overtreatment, Undertreatment

Introduction

The disproportionate rise in geriatric breast cancer cases has inspired a focus on optimizing treatment for women 65 years and older. In 2023, of the over 297,790 estimated new breast cancer cases, more than 45% will be in women in this age cohort.1 Fortunately, older women tend to have more favorable tumors as approximately 60% of these patients are diagnosed with stage I disease, and about 75% have estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) and HER2-negative (HER2-) disease.1–4

In this specific population of patients for whom locoregional therapy (surgery and/or radiation therapy (RT)) is the mainstay of treatment, there is the opportunity to consider de-escalation in cases where patients may derive greater benefit from less invasive therapy. For example, in postmenopausal women with ER+/HER2-cancer, oncotype score, rather than nodal status, generally dictates chemotherapy decisions, eliminating the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for many women.5 Additionally, a high burden of comorbidities may dissuade older women and their providers from pursuing more intense adjuvant systemic therapy options, in which cases axillary surgery serves no role in guiding further treatment. Similarly, although RT may reduce locoregional recurrence (LRR), it has not been shown to prolong overall survival in women with early-stage, low-risk breast cancer and thus can be considered for omission in select patients.6–8

Despite advances in de-escalation of locoregional treatment in these women, safely tailoring therapy remains an individualized and shared decision between patient and provider. To avoid locoregional over- or undertreatment treatment, an accurate assessment of an older patient’s physiologic age is necessary as is incorporation of patient-specific values. While there now exist well-validated geriatric assessment tools to measure frailty, they have not been widely integrated into the breast cancer care model, particularly for locoregional treatment decision-making. An understanding of physiologic age and over- and undertreatment, in the context of trial data supporting opportunities for safe de-escalation of locoregional therapy, will highlight the importance of—and provide a framework for—tailored care in this population.

Defining Frailty, Life Expectancy, and over and Undertreatment

The identification and quantification of frailty and life expectancy has been recognized as a critical component of the care of older patients with cancer. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2023 guidelines stress the importance of these metrics, along with a geriatric assessment, in patients ≥ 65 years old undergoing systemic therapy to identify vulnerabilities not routinely captured in oncologic assessments.9 The role of these tools in guiding locoregional therapy, however, is less well-prescribed. In the treatment of early-stage breast cancer, where a patient’s competing mortality risks often outweighs breast cancer-specific mortality risk, defining frailty and life expectancy will not only help inform the intensity of locoregional treatment offered, but also dictate the survivorship experience.

Frailty

Frailty, which predominantly affects the older adult population, is defined as decreased physiologic reserve, loss of adaptive capacity and increased vulnerability to stressors.10 In conjunction with existing chronic diseases and disabilities, these factors place the geriatric population at increased risk of adverse treatment outcomes, including postoperative morbidity and worse breast cancer-specific and overall survival.11 In a study of women ≥ 70 with cancer, the majority of whom had a diagnosis of breast cancer, approximately half of patients at the time of referral did not have an independent functional status, with 42% requiring assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) and 54% requiring assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (iADLs).12

These baseline limitations, compounded with additional medical and psychosocial considerations, often mean that a frail patient’s limited life expectancy can be attributed to comorbidities other than her breast cancer. A study of Medicare claims data from female nursing home residents yielded 30-day mortality rates up to 8.4% based on surgery type (lumpectomy, mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)), with the highest rates in those that underwent the least invasive surgery (lumpectomy alone), performed in the sickest patients.13 These data suggest that even in patients undergoing low-risk surgery, baseline frailty significantly increases mortality risk, as 30-day mortality rates in the general population after lumpectomy have been reported up to 1%.14 Significant functional disability was also associated with death at one year. When compared to patients capable of performing ADLs, those who were dependent on others had a greater hazard of death across all procedure types (lumpectomy HR 1.92 (1.23–3.00, P = .004); mastectomy HR 1.80 (1.35–2.39, P < .001); ALND HR 1.77 (1.46–2.15, P < .001)).

While women with preexisting frailty prior to diagnosis have a high chance of clinical decline throughout treatment course, all women over the age of 65 are prone to developing frailty during or after treatment. In a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Medicare study of women ≥ 70 with early-stage hormone receptor positive (HR+) breast cancer, even women who had robustness, ie the ability to withstand internal and external stressors,15 prior to treatment had significantly higher odds of decline (OR, 6.12; 95%CI, 2.80–13.35) throughout the care of their breast cancer when compared to those with moderate to severe frailty at baseline. Overall, only 4.1% of women 65 years or older with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or stage I breast cancer were frail at the time of diagnosis, yet 21.4% experienced clinically significant decline over the course of treatment,16 as measured by Kim et al.’s claims based frailty index.17

In the procedural setting, depleted resilience and homeostatic reserve, when compounded with substantial stressors, will lead to poor surgical outcomes.18 Frailty has been shown to predict 30-day mortality rates even after low to moderate-stress procedures. In a study of over 400,000 Veterans Affairs patients undergoing low to moderate stress procedures including lumpectomy, mastectomy, and modified radical mastectomy among other cancer and non-cancer related procedures, frail and very frail patients had a significantly higher mortality rate than non-frail patients. At 30 days, mortality rates in frail patients were 1.5% after low-stress procedures and over 5% in moderate stress procedures, including mastectomy and modified radical mastectomy; 180-day mortality after moderate stress procedures reached up to 43% in very frail patients.19 A limited number of additional small-scale, heterogeneous studies have demonstrated impaired survival in older women with breast cancer who are characterized as frail.20–23 Of note, these studies focus on survival and mortality, leaving the effects of frailty on quality of life (QoL) and survivorship unclear.

While the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and ASCO both recommend that older adults undergo evaluation using a comprehensive geriatric assessment prior to induction of systemic therapy to both prognosticate and predict toxicity,24,25 how these tools affect locoregional decision-making and outcomes is not yet well-studied.

Life Expectancy

The benefit derived from locoregional therapies depends on a patient’s life expectancy, which is informed by her frailty status. Five, ten and 14-year mortality may be estimated using the Lee26 or Schonberg27 indices, which include patient factors such as age, sex, comorbidities, but also functional status, activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, health behaviors and lifestyle factors and self-reported health. Gathering objective life expectancy data is paramount, as numerous studies have demonstrated that clinicians at all stages of training are poor subjective predictors of this metric.28,29 For example, a Canadian study surveyed 19 clinicians including medical students, residents and attending physicians using case-vignettes of prostate cancer patients. Age, Charleson Comorbidity Index (including a list of specific comorbidities) were provided to participants, who were asked to conclude whether each patient survived 10 years after definitive therapy in the absence of disease relapse. The mean area under the curve of all participants was 0.68 (range 0.52–0.78, where 0.5 equals prediction no better than chance and 1.0 equals perfect prediction). There was no significant difference among training levels, highlighting the need for objective models to improve accuracy.29

Quantifying life expectancy becomes particularly important in early-stage breast cancer treatment, where outcomes, and differences in outcomes, are realized over the course of many years. Accurately determining a patient’s life expectancy, while only one component of the treatment decision-making algorithm, may guide providers and patients away from therapies from which patients are unlikely to derive benefit due to shortened life expectancy (ie avoiding overtreatment). In contrast, were a patient to have a longer estimated life expectancy, providers and patients may be inclined to offer additional therapies to treat their disease without increasing the risk of significant morbidity over the patient’s remaining lifetime (ie avoiding undertreatment).

Overtreatment and Undertreatment

Until recently, the concept of undertreatment and overtreatment of older adults with cancer was poorly-defined. DuMontier et al. refined these terms in a scoping review of geriatric patients with a variety of cancers, with breast cancer well-represented at 29%. In evaluation of over 200 articles, only 5.5% provided clear definitions of overtreatment and undertreatment, suggesting that there is not a standardized understanding of these concepts among providers. Overtreatment, the authors concluded, indicates an overly intensive therapy course in an older adult for whom the harms of treatment outweigh the benefits and/or did not expect to meaningfully prolong life expectancy. The definition of undertreatment denotes using less than recommended therapy in a fit older adult who would derive greater net benefit from more intensive treatment with or without worse outcomes. Moreover, it implies deprivation of non-oncologic interventions for deficits in geriatric domains, regardless of therapy choice.

In the review, approximately half (52.8%) of all included articles risk-stratified older adults with the use of a geriatric assessment; fewer (26.2%) advocated for use of a geriatric assessment to detect age-related vulnerabilities such as cognitive impairment or functional debilitation.30 These data expose a valuable opportunity to improve identification of geriatric-specific domains that may be targets for intervention to improve treatment in the frail and nonfrail older population where appropriate as dictated by recent trial data.

Trial Data Supporting De-escalation of Locoregional Therapy

While guidelines now offer opportunity for de-escalation of locoregional therapy in these patients, there is a gap in knowledge regarding the best way to integrate these recommendations to guide treatment in this cohort.

Management of the Breast

The extent of surgical intervention in breast cancer patients has evolved considerably since Halsted’s era of mastectomy with complete axillary clearance. Randomized controlled trial (RCT) data originating in the 1980s has unequivocally demonstrated survival equivalency between mastectomy versus breast conserving surgery (BCS) in all patients7,31–33 inviting opportunity for individualized treatment. With elderly women under-represented in these trials, less is known about age-specific factors that favor one approach over the other. Recent data demonstrate higher rates of morbidity and decreased quality of life domains in older women undergoing mastectomy,34,35 suggesting that minimizing surgery to the breast should be considered when appropriate.

The decision to pursue mastectomy versus lumpectomy is multi-factorial based on criteria such as anatomic considerations, ability to tolerate RT, and patient preference, among others. When either option is available to a frail patient, however, there is data to suggest that de-escalation reduces morbidity. In the Bridging the Age Gap UK study of women age 70 and older with operable breast cancer, major systemic complications including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, or other cardiorespiratory problems were more common with major than minor surgery, albeit low overall (2.9% vs 1.4%; P = .005). While there was no association between complications and age or frailty with respect to major complications, frailty status was associated with a higher rate of local wound complications excluding seroma but including hematoma, infection and wound dehiscence (22.7% versus 17.7% in frail versus non-frail groups; P = .006).34 These findings were reproduced in an American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program study of patients ≥ 65 undergoing mastectomy. A Five-Factor Frailty Index Score greater than two was an independent risk factor for wound complications and overall complications.36

The risks associated with mastectomy extend to QoL metrics, too. While few studies address specific QoL factors in women ≥ 65, in the Bridging the Age Gap UK study, mastectomy was significantly associated with worse QoL score at 6 weeks on the QLQ-C30 global health status questionnaire, though there was no difference at 6 months. Scores on the functional domain of the QLQ-ELD15 questionnaire decreased in both groups immediately after surgery yet remained persistently low in the mastectomy group at the two-year timepoint (65.58% in the mastectomy group versus 71.13% in the BCS group, 95%CI 2.34–8.75; P = .001).34

SEER-Medicare data has also demonstrated severe financial toxicity in older patients undergoing mastectomy with or without reconstruction. Mastectomy with reconstruction was associated with a nearly two-fold increased complication risk when compared with lumpectomy plus whole breast RT with a $2092 higher complication-related cost. Interestingly, the authors found that lumpectomy alone was a high-value intervention in older patients when guideline-concordant, yet associated with higher costs in younger patients due to a high prevalence of mastectomy in the subsequent year after diagnosis.37

Management of the Axilla

More recent trial data has aimed to reduce treatment of the axilla when able to avoid unnecessary morbidity, as axillary surgery is now well-understood to only provide local control and prognostic information without curative potential.31,38 In postmenopausal HR+ women with limited nodal disease in particular, genomic information is more likely to influence systemic therapy decisions as demonstrated in the TAILORx and RxPONDER trials.5,39 In this postmenopausal cohort of patients with HR+/HER2- disease and up to three positive lymph nodes, the Oncotype DX 21-gene recurrence score (Exact Sciences, Redwood City, CA, USA) determined chemotherapy benefit, not nodal status.

A handful of additional trials ushered the development of national recommendations for treatment of the axilla in older adults. In 2006, the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) 10–93 performed an RCT for 473 women ≥ 60 years old with cT1-T3N0 disease randomized to receive breast surgery—either mastectomy or breast conserving therapy (BCT)—and ALND plus tamoxifen versus breast surgery plus tamoxifen only for 5 years. Both arms received RT if surgery was breast-conserving. With a median 6-year follow-up, there was no difference in disease free survival or overall survival and axillary recurrence rates were 3% in the no-ALND and 1% in the ALND arm, suggesting that women 60 years or older with early-stage disease and clinically negative lymph nodes may safely avoid ALND.33

Martelli et al., in a 2012 RCT of 219 women ages 65 to 80 years old with smaller disease (T1N0), randomized patients to lumpectomy with RT and ALND versus lumpectomy plus RT and found no difference in overall or breast cancer specific survival at a mean 15-year follow-up. Axillary recurrence rates were similarly low at 6% in the no ALND arm and 0% in the ALND arm.40

The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9343, a study designed to evaluate RT versus no RT in women ≥ 70 with clinical T1N0, ER+ disease, randomized patients to lumpectomy plus radiation plus tamoxifen versus lumpectomy plus tamoxifen alone with axillary surgery discouraged. The trial design ultimately produced a large population of older women (greater than 60%) who did not undergo axillary staging. Even in the absence of radiotherapy, at a median follow up of approximately 12 years, the LRR rate was 10% in the in the non-RT group, with a nodal recurrence rate of 3% in women who did not receive axillary surgery or RT. There was no difference in overall survival or distant metastases. Importantly, the authors state that the impact of comorbid conditions in their study population outweighed the impact of breast cancer. Of the more than 600 patients in the study, only 3% died of breast cancer with 49% dying from other causes.7

The recently published Sentinel Node versus Observation after Axillary Ultrasound (SOUND) trial ushers the next wave of trials exploring opportunity for omission of axillary surgery. The study enrolled women of any age with tumors ≤ 2 cm and a clinically negative axilla by exam and ultrasound or up to one positive lymph node that was biopsy-negative. All women underwent axillary ultrasound and were treated with BCS. At a median 5.7 years, there was no significant difference in distant disease-free survival with a cumulative incidence of nodal recurrence of 0.4% at 5 years despite a 13.7% nodal involvement rate in the group that underwent axillary surgery. Despite the lack of age restrictions in the inclusion criteria, approximately 80% of patients were >50, and almost 90% were HR+/HER2-.38 These data thus bolster existing evidence of the safety of omission axillary surgery in an older population with HR+/HER2- disease.

Radiation Therapy

Similarly, randomized controlled trial data has demonstrated safety in eliminating radiotherapy in selected older women including those ≥ 70 years with ER+, clinically node negative tumors ≤ 2 cm who will receive endocrine therapy. The recently published PRIME II study addressed the need for radiation in women ≥ 65 years with ER+, node-negative tumors < 3 cm (excluding grade 3 tumors and those with lymphovascular invasion) treated with BCS and adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET). While there was an increased risk of local recurrence (LR) in women in whom RT was omitted (0.9% rate of LR in the RT group vs 9.5% in non-RT group at 10 years; P < .001), there was no difference in overall survival, regional recurrence, breast cancer specific survival or distant metastases.41 The ABCCSG 09 trial similarly randomized postmenopausal patients, the majority of whom were > 60 years old, with ER+, cN0 tumors less than 3 cm to ET plus RT or ET alone. At a median follow-up of 54 months there was a decrease in local recurrence with RT (5.1% vs 0.4%) though no differences in distant metastases or overall survival.42

The CALGB 9343 trial, mentioned above, also demonstrated only a modest improvement in LRR in patients undergoing RT, and no survival benefit or effect on rate of breast conservation. At 10 years, the risk of LRR was 8% lower and the risk of ipsilateral breast recurrence was 7% lower in the group that received RT versus tamoxifen alone. There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival (67% in RT group and 55% in group receiving tamoxifen alone). Additionally, there was no significant difference in time to mastectomy with a 10-year probability of avoiding mastectomy in 98% of those that received RT versus 96% of those who received tamoxifen alone (P = .17).7

Smaller studies have reinforced the potential safety of RT avoidance in patients with a low risk for LRR. In a large retrospective analysis of patients ≥ 70 years enrolled in the German BRENDA collective (n = 2384), there was no significant difference in recurrence free survival for low-risk patients stratified by RT (P = .651). In women with higher risk cancers, there was a significant difference in recurrence free survival (P < .001) and breast cancer specific survival (P = .026). The results did not change after adjusting for adjuvant systemic therapy. Overall, they report rates of relapse of less than 3% in 5 years in patients with low-risk disease versus up to 9% higher in the higher-risk cohort.6

As the importance of tumor biology in dictating response to treatment has become clear, the next generation of radiation therapy omission trials include genomic and molecular subtyping in their selection criteria. The prospective Canadian LUMINA trial has enrolled approximately 500 women ≥ 55 years with luminal A breast cancer ≤ 2 cm to receive 5 years of adjuvant ET without RT after BCS. Median age was 67 though all patients were < 75 years old with median tumor size 1.1 cm; margins were considered negative if ≥1 mm. Initial data presented at the 2022 ASCO meeting demonstrated overall local recurrence rates of 2.3% (90%CI 1.3%−3.8%) at five years with overall survival of 97.2% (90%CI 95.9%−98.4%), though variables including tumor size, margin status and patient age were not delineated.43

In addition, the Individualized Decisions for Endocrine therapy Alone (IDEA) trial followed women postmenopausal women 50–69 years of age, with pT1N0 unifocal HR+/HER2- breast cancers, with ≥2 mm margins and an Oncotype score ≤ 18 who agreed to omit adjuvant RT while taking at least 5 years of ET. The 5-year crude rates of overall recurrence were 5% in patients 50–59 and 3.6% in patients 60–69.44 While these rates are quite low, longer-term follow-up is necessary given the slow but steady increase for risk of recurrence out to 20 years.45,46

Overall, trial data demonstrates that in older patients with low-risk, HR+ disease, omission of radiation is acceptable given lack of impact on survival, though women in the included prospective studies were assumed to be adherent to hormonal therapy. These results, however, do not undermine the value of RT in improving local control, and indeed there are some data suggesting that for certain older adults, exclusive RT without surgery may be a viable treatment option. A retrospective, single-institution study identified 66 patients (6.6%) in an approximately 10 year span who were > 70 and treated with exclusive RT for newly diagnosed breast cancer (surgery omitted for various reasons, including patient refusal). Forty-seven percent of patients had T1–2N0 disease and 31.8% T4N0–3M0 disease. Most patients who were ER+ received hormonal therapy. Compared to patients who underwent BCT, patients in whom surgery was omitted tended to be older than 80 years with a higher Charleson Comorbidity Index. At a median follow up of 6.8 years, the authors reported a breast-cancer specific survival of 86.3%; 43.8% of patients died of their breast cancer. Radiation-associated toxicities were reported in 25 patients, the majority of which were low grade radiodermatitis (59%). While exclusive RT was well-tolerated, prognosis was strongly affected by age and comorbidities in addition to their breast cancer, highlighting the importance of a geriatric assessment when making individualized treatment decisions.47

Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that the majority of existing trials that guide current practice were performed prior to advances in image guidance techniques, the adoption of accelerated partial breast irradiation, breath-hold technique, and ultrahypofractionation, all of which are strategies that increase the tolerability of RT. Overall, these studies do show RT’s modest benefit in improving breast cancers specific and overall survival, particularly in a population burdened with other comorbidities and for whom the morbidity of RT may outweigh its benefit. Importantly, these benefits do not improve with time as demonstrated by long-term follow up in CALGB 9343, where the number of events in both groups remain low at 5 and 10 years.

Endocrine Therapy

Given the predominance of estrogen receptor-positivity in older women with breast cancer, there is particular interest in the role of endocrine therapy alone in frail women at risk for morbidity with surgery. This area is less well-studied given that all de-escalation trials to date include hormonal therapy. In the limited trials of tamoxifen therapy in lieu of surgery in women greater than 70 years old, the majority demonstrate no change in overall survival.48–51

Two trials did demonstrate a modest benefit to the addition of surgery to ET. The Cancer Research Campaign (CRC) UK study of 455 patients ≥ 70 undergoing surgery plus tamoxifen (40 mg/d) versus tamoxifen alone did show slight improvement in overall survival in the surgery plus tamoxifen arm (HR 0.78, 95%CI 0.63–0.96) and a lower hazard of LRR (HR = 0.25, 95%CI 0.19–0.32).52 The Group for Research on Endocrine Therapy in the Elderly (GRETA) trial in Italy with similar inclusion criteria (though tamoxifen was dosed at 20 mg/d) also showed modest improvement in LRR (HR = 0.38, 95%CI 0.25–0.57) with no change in overall survival in the arm that underwent surgery (HR = 0.98, 95%CI 0.77–1.25).53 Nonetheless, a Cochrane review of all available trials demonstrated the inferiority of endocrine therapy alone for local control in medically fit older women, with noninferiority with respect to overall survival.54 Of note, none of these trials include geriatric-specific assessments, and only one (CRC group) included minimal data on quality of life.

The Bridging the Age Gap in Breast Cancer UK study, which marks the most recent prospective work in this arena, did incorporate geriatric-specific metrics. The authors examined primary endocrine therapy (PET) versus surgery plus ET in women with a median age of 77 years (range 69–102). Overall survival was inferior in the PET group (HR 0.27, 95%CI 0.23–0.33, P < .001), as was breast cancer specific survival (HR 0.41, 95%CI 0.29–0.58, P < .001) in unmatched analyses. When matched, overall survival remained inferior in the PET group, though the differential in breast cancer specific survival was no longer significant. Given that patients in the surgery plus ET arm were generally younger and fitter with superior functional status to those undergoing PET (older women with worse baseline quality of life scores which corresponded with greater number of comorbidities and reduced physical function), the authors concluded that for fit older women with early-stage ER+ breast cancer, surgery is superior to ET. However, for less fit women with ER+ tumors and a median age of 81, higher comorbidity status and functional impairments, and limited life-expectancy, individualized treatment courses with primary endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy plus surgery may be appropriate.55 These data suggest that in a carefully selected group of patients with favorable tumors, ET omission may be discussed.

Guidelines and Adherence

The release of trial data supporting safe omission of axillary surgery and RT in older women with HR+/HER2- disease rapidly inspired the publication of the 2016 Society for Surgical Oncology Choosing Wisely Campaign and the NCCN guidelines. The SSO governing body advises the avoidance of SLNB in clinically node negative women 70 years or older with early-stage, HR+, HER2- breast cancer. While their assertions are definitive (“Don’t routinely use sentinel node biopsy in clinically node negative women ≥70 years of age with early-stage hormone receptor positive, HER2 negative invasive breast cancer”),56 they do acknowledge that axillary staging can be considered in cases in which the results will impact radiation or systemic therapy decisions. In contrast, the NCCN is less prescriptive, deeming axillary staging as “optional” in patients with favorable tumors or in whom the decision to pursue adjuvant systemic or RT is unlikely to be affected by nodal status either due to disease biology or existing comorbidities.57

The language employed in these guidelines leaves room for individual practitioner and patient interpretation, which is reflected in current practice patterns of high rates of axillary intervention, mastectomy,58–60and radiotherapy.61,62 Prior to the publication of the Choosing Wisely Campaign yet during the publication of trial data (2004–2015), Louie et al. performed a National Cancer Database (NCDB) analysis of women ≥ 70 with cT1-T2 HR+ invasive ductal carcinoma after partial or total mastectomy (n = 99,940). Over time, rates of axillary surgery increased from 78% to 88% (P< .001) across region and care setting though flattened as age increased. Interestingly, omission of axillary surgery was more common in the New England region (RR 0.88, 95%CI 0.86–0.89) and in patients ≥ 85 (RR 0.66, 95%CI 0.65–0.67).63

To determine whether there was a meaningful shift in practice during guideline publication, Minami et al. again interrogated the NCDB using a similar population. In patients ≥ 70 with early-stage, HR+ breast cancer (n = 44,779) there was again little de-escalation in practice. Approximately 83% of women eligible for omission of SLNB underwent nodal sampling and 20% of 7216 patients eligible for omission of ALND underwent ALND. While SLNB rates did not meaningfully change over time between 2013 and 2016, they did significantly decrease between age groups (70–74 years: 93.5%; 75–79 years: 89.7%, 80–84 years: 76.7%, ≥ 85 years: 48.9%; P < .05). Only patients ≥ 85 had rates of SLNB < 50%. Rates of ALND did globally decrease despite age from 22.5% to 16.9% (P < .001).64

With respect to RT, Chu et al. performed an NCDB analysis to assess practice trends following the initial publication of CALGB 9343, between 2005 and 2012. The authors report that in patients ≥70 years with stage I, ER+ breast cancer who underwent lumpectomy, use of radiation decreased by 4.1% (on average 71.6% pre-CALGB vs 67.5% post-CALGB; P < .0001). Moreover, nearly one-third of women ≥ 85 years received RT after the publication of the trial data. Variables associated with a significantly high likelihood of RT omission included low income level, Medicaid, rural residence, African-American race and lack of receipt of chemotherapy or endocrine therapy.58 As noted by Pak et al., these discrepancies more likely highlight disparities in care rather than evidence-based efforts to de-escalate intervention.65

At present, the decision to safely omit axillary surgery and RT accordingly to guidelines is contingent upon endocrine therapy adherence, yet ET adherence remains variable. Data have demonstrated that ET adherence worsens with time and impacts survival in older adults. A recently published SEER-Medicare study of women ≥ 66 years with stage I-III breast cancer taking hormonal therapy after primary surgery sought to assess these rates over 5 years. Starting annual and cumulative adherence rates were 78.1% at one year, and starting persistence, defined as not taking a break in endocrine therapy of at least 180 days, was 87.5%. All rates steadily declined by approximately 10% over 5 years.66 Furthermore, data from Hershman et. al’s study on early discontinuation and non-adherence to ET convey that the less adherent patients are to their therapy, the greater the hazard ratio of death from breast cancer.67 On a locoregional scale, the PRIME II trial revealed that nonadherence to endocrine therapy was associated with higher incidence of local recurrence in the group that did not receive radiotherapy.41

These findings have propelled investigation into short course radiation monotherapy as an alternative to endocrine therapy,68,69 reflecting efforts to afford patients individualized therapy options. The NSABP B-21 trial provided a framework for this question though was not limited to older adults. The study randomized 1009 patients to tamoxifen alone, radiation plus placebo and radiation plus tamoxifen to determine whether tamoxifen was as effective as radiation in controlling ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR). At 8 years, IBTR was highest among women receiving tamoxifen alone (16.5%) versus RT alone (9.3%) or combination therapy (2.8%) with no significant difference in overall survival or distant recurrence.70

Ongoing trials dedicated to older women seek to further understand whether radiation alone can provide a safe alternative for patients who may decline or be ineligible for combination RT plus ET adjuvant therapy. Among them, the Exclusive Endocrine Therapy or Partial Breast Irradiation for Women Aged ≥ 70 Years Early Stage Breast Cancer (EUROPA) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04134598) evaluates accelerated partial breast irradiation as compared with endocrine therapy in women ≥ 70 with early-stage, HR+ disease. The phase-II Comparison of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy and Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation following Lumpectomy for the Treatment of Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients Over 65 (CAMERAN) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT054722782) plans to recruit 90 patients with a primary endpoint of QoL. The number of potentially safe options with respect to different combinations of therapies for older patients with early-stage low-risk breast cancers underscores the need for tools to assist clinicians and patients alike in the therapeutic decision-making process.

The Geriatric Assessment

Current Tools and Implementation

With a growing body of data to suggest safe de-escalation of locoregional treatment, the challenge then becomes identifying which older patients that may benefit from omission of therapy. The comprehensive geriatric assessment (GA) can identify comorbidities or deficits that may affect treatment eligibility while also highlighting quality of life considerations that may help prioritize certain treatment paths in the face of multiple options. The comprehensiveGA is a multidimensional evaluation tool to assess factors that contribute to a patient’s physiologic age. Domains on the assessment include cognitive status, functional status, comorbidities, nutritional status, mood, medications, environment and social support system.25

Importantly, these tools have demonstrated both prognostic and predictive value. In the breast cancer arena, specifically, Clough-Gorr et al conducted a number of studies of women ≥ 65 years old with stage I-IIIa tumors who underwent surgery and a cancer-specific GA (CSGA). First, they found that domains on the CSGA were associated with poor treatment tolerance and predictive of mortality at seven year follow-up, regardless of age and disease stage.21 With respect to survival, women in the same cohort with ≥ 3 CSGA-identified deficits had poorer 5 and 10 year overall survival (HR 1.87 and 1.74, respectively) and breast-cancer specific survival (HR 1.95 and 1.99, respectively).20

Comprehensive assessments are often time-consuming, however, and thus can be prohibitive in a busy clinic. Though self-administered versions have proven to be feasible with median time to completion of 22 minutes,71 more efficient screening tools may be employed initially to identify vulnerable patients who would benefit from a more thorough comprehensive assessment. Several screening tools exist including the Geriatric 8, which takes an average of 4 minutes,72 in addition to Vulnerable Elders Score 13, Clinical Frailty Scale, and single-item tests including gate speed, grip strength, timed up and go. To streamline clinic workflow, providers can then proceed to a comprehensive GA tool to further delineate patient-specific vulnerabilities when indicated. The preferred comprehensive GA is the Practical Geriatric Assessment, developed by the Older Adults Task Force of ASCO’s Health Equity and Outcomes Committee in collaboration with the Cancer and Aging Research Group in response to a 2019 ASCO survey indicating provider discordance with guidelines. The tool was created to streamline adoption and increase feasibility of completion either in clinic or outside of clinic in a timely fashion.9

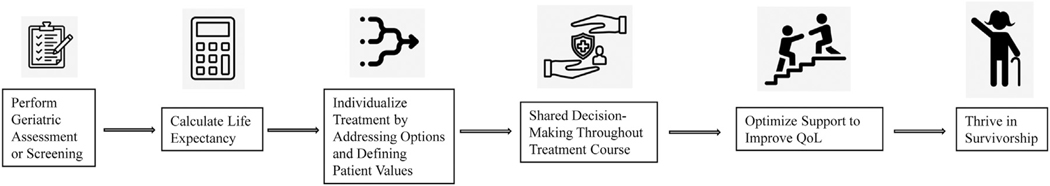

Once the geriatric assessment or screening has been performed, life expectancy should be calculated using the Lee or Schonberg indices.26,27 Together, these data may inform shared decision-making during which patient and provider align options and alternatives to therapy with patient values and preferences (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed geriatric-focused treatment algorithm for older women with early-stage breast cancer eligible for locoregional therapy.

Future Directions

While these tools tend to be good predictors of morbidity and mortality in older women with cancer, they also highlight possible targets for intervention and future trials addressing QoL throughout treatment and survivorship. Improving upfront patient-provider shared decision-making (SDM) has been one early target. The key to SDM is equal participation between patient and provider to identify patient preferences and integrate these with available treatment options.

Tools such as decision aids and language guides have been created to facilitate this process in clinic. One such model, The SHARE (Seek, Help, Assess, Reach, Evaluate) Approach, was developed by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2015.73 It provides language for engaging patients (ie a clinician may say to a patient: “As you think about your options, what’s important to you?”). A Cochrane review of 17 surgical studies of found that up to 20% of patients who participated in SDM chose less invasive surgery than patients who did not use a decision aid with their provider (RR 0.84; 95%CI 0.73–0.97). Yet the aforementioned poor adherence to guidelines thus far highlights the ongoing need for future work targeting multidisciplinary education to maximize incorporation of guidelines into practice, specifically patient and provider level barriers to communication.

From a systems perspective, the results of GAs may identify certain geriatric domains amenable to, and potentially modifiable by, healthcare intervention. For example, functional status may be improved by physical or occupational therapy referral pre-treatment, or comorbidities may be safely addressed with the aid of a primary care physician to reduce polypharmacy and monitor for other disease progression. Identification of vulnerable domains may inspire pre-habilitation programs, team-based care via dedicated integration of geriatricians, and post-treatment care initiatives to better support older adults and their caregivers.74,75

Furthermore, GAs and screening GAs highlight an opportunity to focus on patient-reported outcomes and geriatric-specific needs that may improve the survivorship experience and adherence to guidelines that discourage overtreatment. Previous large-scale data has highlighted that older women prioritize quality of life and independence over length of life,76,77 but little work has been done to identify specific outcomes of importance in this population. As these key patient-reported outcomes are studied, special care must be dedicated to the recruitment of a frail, diverse population into future trials to ensure that this demographic is well-represented.

Conclusions

As a better understanding of tumor biology propels the individualization of breast cancer care, particularly the opportunity to deescalate invasive therapy in select populations, it is imperative that the care of older patients adapts at the same rate. Strong trial data for safe omission of axillary surgery and RT in select patients offers hope that in the majority of cases morbidity may be avoided in older women. Yet the lack of specificity of language in current guidelines allows for disparities in practice and the potential for over and under treatment. Thus, objective data from geriatric assessments become all the more important in defining in whom omission may be appropriate.

The care of the older adult population therefore remains complex and multifactorial, requiring the integration of oncologic priorities with geriatric-specific concerns. While a specialized geriatrics team is undoubtedly best equipped to care for these patients in concert with medical, surgical and radiation oncology providers, there is a growing scarcity of geriatricians in the U.S. Whereas the country boasted 10,270 geriatricians in 2000, only 7413 board-certified geriatricians remained in 2022.78 The advent and accessibility of comprehensive geriatric assessments and screening geriatric assessments, however, afford all practitioners the opportunity to address, study, and tailor therapy to the unique needs of the older adult breast cancer population in daily practice.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Eliza H. Lorentzen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Christina A. Minami: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

References

- 1.Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed February 22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daidone MG, Coradini D, Martelli G, Veneroni S. Primary breast cancer in elderly women: biological profile and relation with clinical outcome. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;45(3):313–325. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(02)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sierink JC, de Castro SM, Russell NS, Geenen MM, Steller EP, Vrouenraets BC. Treatment strategies in elderly breast cancer patients: Is there a need for surgery? Breast. 2014;23(6):793–798. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mamtani A, Gonzalez JJ, Neo D, et al. Early-stage breast cancer in the octogenarian: tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3371–3378. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2005–2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stueber TN, Diessner J, Bartmann C, et al. Effect of adjuvant radiotherapy in elderly patients with breast cancer. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0229518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2382–2387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Boer AZ, Bastiaannet E, de Glas NA, et al. Effectiveness of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in older patients with T1–2N0 breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(3):637–645. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dale W, Klepin HD, Williams GR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving systemic cancer therapy: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(26):JCO2300933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minami CA, Cooper Z. The frailty syndrome: a critical issue in geriatric oncology. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(1):151–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandelblatt JS, Cai L, Luta G, et al. Frailty and long-term mortality of older breast cancer patients: CALGB 369901 (Alliance). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4222-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girre V, Falcou MC, Gisselbrecht M, et al. Does a geriatric oncology consultation modify the cancer treatment plan for elderly patients? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(7):724–730. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.7.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang V, Zhao S, Boscardin J, et al. Functional status and survival after breast cancer surgery in nursing home residents. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(12):1090–1096. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Tamer MB, Ward BM, Schifftner T, Neumayer L, Khuri S, Henderson W. Morbidity and mortality following breast cancer surgery in women: national benchmarks for standards of care. Ann Surg.. 2007;245(5):665–671. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000245833.48399.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varadhan R, Walston JD, Bandeen-Roche K. Can a link be found between physical resilience and frailty in older adults by studying dynamical systems? J Am Geriatr Soc.. 2018;66(8):1455–1458. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minami CA, Jin G, Freedman RA, Schonberg MA, King TA, Mittendorf EA. Association of surgery with frailty status in older women with early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(6):664–666. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Lipsitz LA, Rockwood K, Avorn J. Measuring frailty in medicare data: development and validation of a claims-based frailty index. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(7):980–987. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson TN, Walston JD, Brummel NE, et al. Frailty for surgeons: review of a national institute on aging conference on frailty for specialists. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(6):1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.08.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinall MC, Arya S, Youk A, et al. Association of preoperative patient frailty and operative stress with postoperative mortality. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(1):e194620. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clough-Gorr KM, Thwin SS, Stuck AE, Silliman RA. Examining five- and ten-year survival in older women with breast cancer using cancer-specific geriatric assessment. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(6):805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clough-Gorr KM, Stuck AE, Thwin SS, Silliman RA. Older breast cancer survivors: geriatric assessment domains are associated with poor tolerance of treatment adverse effects and predict mortality over 7 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):380–386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stotter A, Reed MW, Gray LJ, Moore N, Robinson TG. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and predicted 3-year survival in treatment planning for frail patients with early breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102(5):525–533 discussion 533. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parks RM, Hall L, Tang SW, et al. The potential value of comprehensive geriatric assessment in evaluating older women with primary operable breast cancer undergoing surgery or non-operative treatment–a pilot study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2014.09.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dotan E, Walter LC, Browner IS, et al. NCCN guidelines(R) insights: older adult oncology, version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.. 2021;19(9):1006–1019. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, Hurria A. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology summary. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(7):442–446. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295(7):801–808. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. Index to predict 5-year mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older using data from the National Health Interview Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1115–1122. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow E, Davis L, Panzarella T, et al. Accuracy of survival prediction by palliative radiation oncologists. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(3):870–873. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walz J, Gallina A, Perrotte P, et al. Clinicians are poor raters of life-expectancy before radical prostatectomy or definitive radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100(6):1254–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuMontier C, Loh KP, Bain PA, et al. Defining undertreatment and overtreatment in older adults with cancer: a scoping literature review. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(22):2558–2569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher B, Jeong JH, Anderson S, Bryant J, Fisher ER, Wolmark N. Twenty-five-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, and total mastectomy followed by irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):567–575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martelli G, Boracchi P, Orenti A, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in older T1N0 breast cancer patients: 15-year results of trial and out-trial patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(7):805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.International Breast Cancer Study G, Rudenstam CM, Zahrieh D, et al. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):337–344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan JL, George J, Holmes G, et al. Breast cancer surgery in older women: outcomes of the Bridging Age Gap in Breast Cancer study. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):1468–1479. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mogal HD, Clark C, Dodson R, Fino NF, Howard-McNatt M. Outcomes after mastectomy and lumpectomy in elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol.. 2017;24(1):100–107. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5582-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dammeyer K, Alfonso AR, Diep GK, et al. Predicting postoperative complications following mastectomy in the elderly: evidence for the 5-factor frailty index. Breast J. 2021;27(6):509–513. doi: 10.1111/tbj.14208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith BD, Jiang J, Shih YC, et al. Cost and complications of local therapies for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109(1):djw178. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gentilini OD, Botteri E, Sangalli C, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy vs no axillary surgery in patients with small breast cancer and negative results on ultrasonography of axillary lymph nodes: the sound randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(11):1557–1564. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalinsky K, Barlow WE, Gralow JR, et al. 21-gene assay to inform chemotherapy benefit in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(25):2336–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martelli G, Boracchi P, Ardoino I, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in older patients with T1N0 breast cancer: 15-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):920–924. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827660a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunkler IH, Williams LJ, Jack WJL, Cameron DA, Dixon JM. Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(7):585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potter R, Gnant M, Kwasny W, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen or anastrozole with or without whole breast irradiation in women with favorable early breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68(2):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whelan TJ, Smith S, Nielsen TO, et al. LUMINA: A prospective trial omitting radiotherapy (RT) following breast conserving surgery (BCS) in T1N0 luminal A breast cancer (BC). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(17_suppl):LBA501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.17_suppl.LBA501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Harris EE, et al. Omission of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for women with breast cancer with low clinical and genomic risk: 5-year outcomes of IDEA. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(4):390–398. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.02270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1836–1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pedersen RN, Esen BO, Mellemkjaer L, et al. The incidence of breast cancer recurrence 10–32 years after primary diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(3):391–399. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao KI, Waechter L, Carton M, Kirova YM. Outcomes of exclusive radiation therapy for older women with breast cancer according to age and comorbidity status: an observational retrospective study. Breast J. 2020;26(5):976–980. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fentiman IS, Christiaens MR, Paridaens R, et al. Treatment of operable breast cancer in the elderly: a randomised clinical trial EORTC 10851 comparing tamoxifen alone with modified radical mastectomy. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(3):309–316. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kenny FS, Robertson JFR, Ellis IO, Elston CW, Blarney RW. Long-term follow-up of elderly patients randomized to primary tamoxifen or wedge mastectomy as initial therapy for operable breast cancer. The Breast. 1998;7(6):335–339. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(98)90077-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capasso INF, Labonia V, Land G, Rossi E, de Matteis A. Surgery + tamoxifen versus tamoxifen as treatment of stage I and II breast cancer in over to 70 years old women: ten years follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2000;4(11):20. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gazet JC, Ford HT, Coombes RC, et al. Prospective randomized trial of tamoxifen vs surgery in elderly patients with breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1994;20(3):207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bates T, Riley DL, Houghton J, Fallowfield L, Baum M. Breast cancer in elderly women: a Cancer Research Campaign trial comparing treatment with tamoxifen and optimal surgery with tamoxifen alone. The Elderly Breast Cancer Working Party. Br J Surg. 1991;78(5):591–594. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mustacchi G, Ceccherini R, Milani S, et al. Tamoxifen alone versus adjuvant tamoxifen for operable breast cancer of the elderly: long-term results of the phase III randomized controlled multicenter GRETA trial. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(3):414–420. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hind D, Wyld L, Beverley CB, Reed MW. Surgery versus primary endocrine therapy for operable primary breast cancer in elderly women (70 years plus). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(1):CD004272. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004272.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wyld L, Reed MWR, Morgan J, et al. Bridging the age gap in breast cancer. Impacts of omission of breast cancer surgery in older women with oestrogen receptor positive early breast cancer. A risk stratified analysis of survival outcomes and quality of life. Eur J Cancer. 2021;142:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. 2016. Available at: https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/society-of-surgical-oncology/. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 57.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, et al. Breast cancer, version 4.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(3):310–320. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chu QD, Hsieh MC, Yi Y, Lyons JM, Wu XC. Outcomes of breast-conserving surgery plus radiation vs mastectomy for all subtypes of early-stage breast cancer: analysis of more than 200,000 women. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234(4):450–464. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patrick JL, Hasse ME, Feinglass J, Khan SA. Trends in adherence to NCCN guidelines for breast conserving therapy in women with Stage I and II breast cancer: analysis of the 1998–2008 National Cancer Data Base. Surg Oncol. 2017;26(4):359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kummerow KL, Du L, Penson DF, Shyr Y, Hooks MA. Nationwide trends in mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg.. 2015;150(1):9–16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palta M, Palta P, Bhavsar NA, Horton JK, Blitzblau RC. The use of adjuvant radiotherapy in elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer: changes in practice patterns after publication of Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9343. Cancer. 2015;121(2):188–193. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Squeo G, Malpass JK, Meneveau M, et al. Long-term Impact of CALGB 9343 on Radiation Utilization. J Surg Res. 2020;256:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Louie RJ, Gaber CE, Strassle PD, Gallagher KK, Downs-Canner SM, Ollila DW. Trends in surgical axillary management in early stage breast cancer in elderly women: continued over-treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(9):3426–3433. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08388-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minami CA, Jin G, Schonberg MA, Freedman RA, King TA, Mittendorf EA. Variation in deescalated axillary surgical practices in older women with early-stage breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-11677-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pak LM, Morrow M. Addressing the problem of overtreatment in breast cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2022;22(5):535–548. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2022.2064277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng D, Thomas 3rd J. Survival benefits associated with being adherent and having longer persistence to adjuvant hormone therapy across up to five years among U.S. Medicare population with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023;201(1):89–104. doi: 10.1007/s10549-023-06992-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat.. 2011;126(2):529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McDuff SGR, Blitzblau RC. Optimizing adjuvant treatment recommendations for older women with biologically favorable breast cancer: short-course radiation or long-course endocrine therapy? Curr Oncol. 2022;30(1):392–400. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Naoum GE, Taghian AG. Endocrine treatment for 5 years or radiation for 5 days for patients with early breast cancer older than 65 years: can we do it right? J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(13):2331–2336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fisher B, Bryant J, Dignam JJ, et al. Tamoxifen, radiation therapy, or both for prevention of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after lumpectomy in women with invasive breast cancers of one centimeter or less. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(20):4141–4149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1290–1296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soubeyran P, Bellera C, Goyard J, et al. Screening for vulnerability in older cancer patients: the ONCODAGE prospective multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quality AfHRa. The SHARE Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Magnuson A, Dale W, Mohile S. Models of Care in Geriatric Oncology. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2014;3(3):182–189. doi: 10.1007/s13670-014-0095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, et al. Communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment: a cluster-randomized clinical trial from the national cancer institute community oncology research program. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(2):196–204. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Husain LS, Collins K, Reed M, Wyld L. Choices in cancer treatment: a qualitative study of the older women’s (>70 years) perspective. Psychooncology. 2008;17(4):410–416. doi: 10.1002/pon.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shrestha A, Martin C, Burton M, Walters S, Collins K, Wyld L. Quality of life versus length of life considerations in cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Psychooncology. 2019;28(7):1367–1380. doi: 10.1002/pon.5054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gurwitz JH. The paradoxical decline of geriatric medicine as a profession. JAMA. 2023;330(8):693–694. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.11110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]