Abstract

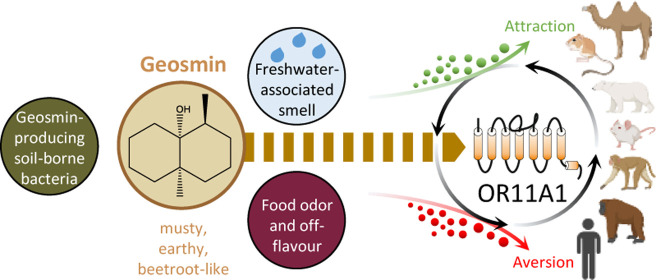

Geosmin, a ubiquitous volatile sesquiterpenoid of microbiological origin, is causative for deteriorating the quality of many foods, beverages, and drinking water, by eliciting an undesirable “earthy/musty” off-flavor. Moreover, and across species from worm to human, geosmin is a volatile, chemosensory trigger of both avoidance and attraction behaviors, suggesting its role as semiochemical. Volatiles typically are detected by chemosensory receptors of the nose, which have evolved to best detect ecologically relevant food-related odorants and semiochemicals. An insect receptor for geosmin was recently identified in flies. A human geosmin-selective receptor, however, has been elusive. Here, we report on the identification and characterization of a human odorant receptor for geosmin, with its function being conserved in orthologs across six mammalian species. Notably, the receptor from the desert-dwelling kangaroo rat showed a more than 100-fold higher sensitivity compared to its human ortholog and detected geosmin at low nmol/L concentrations in extracts from geosmin-producing actinomycetes.

Keywords: olfaction, GPCR, high-throughput screening, sensor

Introduction

Geosmin ((4S,4aS,8aR)-4,8a-dimethyloctahydronaphthalen-4a(2H)-ol) is a bicyclic, natural, volatile sesquiterpenoid1 that is associated with an “earthy/musty” odor. Isolated for the first time in 1965,2 it is prominently responsible for adversely affecting the quality of foods and beverages, such as fish,3−5 beans,6 cocoa,7 grape juice,8,9 wine,10,11 and drinking water,12−16 with its undesirable “earthy/musty” off-flavor, thereby causing extensive commercial losses.

The gross production of geosmin is attributed to microorganisms found primarily in terrestrial environments such as soil-borne Actinomycetes, e.g., Nocardia fluminea, Streptomyces albus, or Streptomyces albidoflavus.16−20 In addition, certain species of cyano- and myxobacteria,21−25 and fungi8,26,27 are known producers of geosmin, as well as some vascular plants like cactus flowers28 and red beet.29 Indeed, a geosmin production was reported to be phylogenetically conserved in genera from both bacteria and fungi.30 At least the microbial geosmin synthesis involves the conversion of farnesyl diphosphate to germacradienol, and further to geosmin31 by a sesquiterpene synthase that is encoded by a geosmin synthase gene (geoA) found in a variety of cyanobacteria and bacteria in both the aquatic and terrestrial environments.17,32−35 While production of geosmin is widespread, especially in the abovementioned bacterial groups, which are found in many soils, its biological function is only partially solved and perhaps indeed diverse due to its ubiquity.

Geosmin is a volatile, chemosensory trigger of both avoidance and attraction behaviors across species.36 In arid or semiarid environments, species such as camels or elephants37 may associate the smell of geosmin with water sources over long distances. Geosmin attracts Aedes aegypti mosquitos to potential oviposition sites.38 In contrast, microbial geosmin acts as an aposematic signal for the bacteriophagous worm Caenorhabditis elegans, indicating the presence of potentially toxic metabolites, thus reducing the worm’s predation on bacteria.39 Zaroubi et al. suggested that, here, geosmin acts as a warning signal for nematodes (and other predators), quite similar to brightly colored animals warning about their poison.39 Likewise, geosmin creates aversion in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster not to feed on fermented/decaying fruit, to avoid toxic compounds of microbial origin.40 Previously, a functionally segregated olfactory circuit has been identified in flies, which is activated exclusively by geosmin via the olfactory receptor Or56a.40

Humans can react significantly to the smell of geosmin as well and show this by either attraction or repulsion behaviors. A rather low human odor detection threshold (OT) (orthonasally in water) for geosmin has been determined between 4 and 10 ng/L, which is about one teaspoon in 200 Olympic swimming pools.36,41−43 While geosmin’s “earthy” note may add a fresh scent to perfumes and fragrances, at least at low concentrations,44,45 the food sector, however, is more concerned with preventing or reducing geosmin as a quality control measure for food products and drinking water, since here it is noted to be unpleasant with a “musty” connotation.46,47

In vertebrates, the detection of volatiles typically is associated with the chemoreception of odorants by odorant receptors (ORs),48 which are seven transmembrane domain G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).49 In humans, ORs are encoded by about 400 genes50,51 and are typically situated in the cilia of olfactory sensory neurons of the nose. They have evolved to best recognize ecologically relevant groups of volatiles, for example, key food odorants (KFOs) or semiochemicals.52−54 So far, a geosmin-selective or even geosmin-specific human OR has been elusive. Human ORs, however, have no sequence similarity with insect ORs, which have an inverted membrane topology compared to GPCRs,55 and have been shown to function as heteromeric, ligand-gated ion channels.56,57 The highly sensitive chemosensory detection of geosmin has been observed across animal phyla,36 thus suggesting convergent evolution of different geosmin-specific receptors.

Here, we set out to identify the best-responding human OR for geosmin. Using a bidirectional screening approach, we first screened geosmin against our IL-6-HaloTag-OR cDNA library, comprising 616 human allelic variants,58 utilizing the GloSensor technology.59 We then screened the identified receptor against a comprehensive collection of known KFOs53 to elucidate its KFO agonist profile. Moreover, we compared the OR’s responses to geosmin from orthologs across six species. Finally, we demonstrate an OR11A1 receptor being capable of detecting minute amounts of geosmin, verified by exact quantitation, in extracts obtained from the geosmin-producing strains of Streptomyces albus and Streptomyces albidoflavus.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

The following chemicals were used: FBS superior (#FBS. S 0615), l-glutamine (#BS. K 0282), penicillin/streptomycin (each 10,000 U/mL; #BS. A 2212), and trypsin/EDTA solution (#BS. L 2143; Bio&Sell, Feucht, Germany); calcium chloride dihydrate (#22322.295), d-glucose (#101174Y), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (#83673.230), HEPES (#441476L), potassium chloride (#26764.230), and sodium hydroxide (#28244.295; VWR International GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany); sodium chloride (#1064041000; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); d-luciferin (beetle) monosodium salt (#E464X; Promega, Madison, USA); Pluronic PE 10500 (#50053867; BASF, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany); and Dulbecco′s MEM (#D1145), geosmin (#UC18), 2-ethylfenchol (#W349100), and (−)-fenchone (#92101; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Compounds used in the KFO screen were as previously published60,61 (Table S1). (4S,4aS,8aR)-4,8a-Dimethyl(3,3,4-2H3)octahydronaphthalen-4a(2H)-ol was synthesized as detailed in ref (62). Dichloromethane (#CLN-7053.2500; CLN; Freising, Germany) was freshly distilled before use.

Molecular Cloning of Human OR11A1 and Mammalian Orthologs

Mammalian orthologs of human OR11A1 have been identified via NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/kis/info/how-are-orthologs-calculated/) and OrthoDB v11 (https://www.OrthoDB.org/). Genomic DNA was purified from a saliva sample from a female Sumatran orangutan, born to the Borås zoo in Sweden before 2014. The protein-coding regions of OR11A1 from human (NP_001381757.1), mouse (Mus musculus; NP_666725.1), and Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii; XP_009239850.1) were amplified from genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using gene-specific primers (Table S2). Amplicons were EcoRI/NotI-digested (#R6017/#R6435; Promega, Madison, USA), ligated with T4-DNA ligase (#M1804; Promega, Madison, USA) into the expression plasmid IL-6-HaloTag-pFN210A,58 and verified by Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany) using vector internal primers (Table S3). The predicted protein-coding regions of the OR11A1 equiv of camel (Camelus ferus; XP_014423806.2), kangaroo rat (Dipodomys ordii; XP_012886577.1), rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta; XP_014991151.2), and polar bear (Ursus maritimus; XP_008707080.1) were synthesized and cloned into the expression plasmid IL-6-HaloTag-pFN210A58 by BioCat GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany). In the same way, all human ORs used in the present study (Table S4) were cloned and ligated into the expression plasmid IL-6-HaloTag-pFN210A and were purified using the PureYield Plasmid Midiprep System (no. A2495; Promega, Madison, USA).

The evolutionary history of the OR11A1 orthologs was inferred by employing the Maximum Likelihood method and JTT matrix-based model, using a ClustalW alignment of their deduced amino acid sequences.63 The tree with the highest log likelihood (−1951.60) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa cluster together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the JTT model and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. This analysis involved seven amino acid sequences (Figure S1). There were a total of 318 positions in the final data set. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X.64

Cell Culture

HEK-293 cells,65 a human embryonic kidney cell line, authenticated in 2021 (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany), were used as a test cell system for the functional expression of recombinant ORs.58,66 Cells were cultivated in 4.5 g/L d-glucose containing DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 units/mL streptomycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity.

cAMP Luminescence Assay

Luminescence-based functional expression experiments were performed in HEK-293 cells using the pGloSensor-22F (Promega, Madison, USA), coding for a genetically engineered, cAMP-dependent luciferase,59 and ViaFect (#E4982; Promega, Madison, USA), as described previously.58,66 For receptor screening experiments, a cDNA expression plasmid library, comprising 616 cDNAs, coding for 386 human OR types (NCBI reference sequences) and 230 of their most frequent variants (Table S4), was used.

Data Analysis of the cAMP Luminescence Measurements

The raw luminescence data obtained from the GloMax Discover microplate reader was analyzed by averaging the data points of basal levels and the data points after odorant application. For concentration–response relations, the respective basal level was subtracted from each corresponding luminescence signal, and the baseline-corrected data set was normalized to the maximum amplitude of the odorant–receptor pair. The data set for the mock control was subtracted, and EC50 values (effective concentration at 50% of maximum) and curves were derived from fitting the function:67

to the data by nonlinear regression (SigmaPlot 14.0, Systat Software).

For measuring the receptor activation by bacterial extracts, the data set was baseline-corrected as described above and normalized to the amplitude of the luminescence buffer. All data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three independent transfection experiments. The data presented in this article was published with Mendeley (DOI: 10.17632/z2934cw7yy.1).

Cultivation of Actinomycetes

To obtain naturally occurring geosmin extracts, we cultivated Actinomycetes on agar plates and washed the plates using luminescence assay buffer. Streptomyces albidoflavus FBUA 521 (formerly S. coelicolor A3(2), acquired from DSMZ as DSM 41007, stored in the Weihenstephan Strain Collection as WS 4613) and Streptomyces albus subsp. albus ATCC 25426 (acquired from ATCC, stored as WS 5155) were grown on BHI agar (#X915.1; Carl Roth, Germany). Fifteen plates of each strain had been confluently inoculated and incubated for 2 days at 30 °C. Each plate was washed with approximately 15 mL luminescence assay buffer for 10 min. The liquid of all plates was combined, briefly centrifuged to pellet bacterial remains, and sterile-filtered (0.22 μm pore size). Extracts were used for testing the activation of OR11A1 and doOR11A1 in luminescence assays (Table 1). Of note, both Streptomyces only produced measurable amounts of geosmin on agar plates but not in liquid culture (not shown).

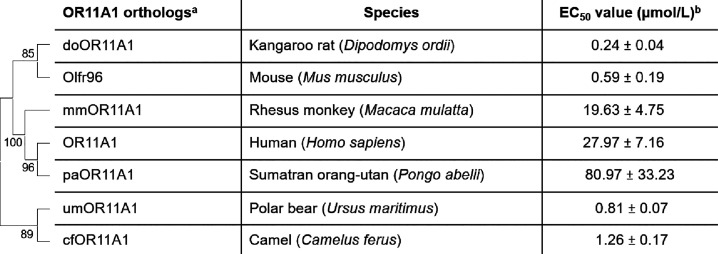

Table 1. Evolutionary Relationships of OR11A1 Orthologs and Their Sensitivities for Geosmin.

Maximum likelihood tree with 500 bootstrap values.

EC50 values are given as mean ± SD (n = 3–5).

Automated Solvent-Assisted Flavor Evaporation (aSAFE) and Heart-Cut GC–GC–HRMS

For the quantitation of geosmin, dichloromethane (30 mL) and (2H3)geosmin (0.111 μg) were added to the sample (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 30 min. The volatiles were extracted in a separate funnel with two further portions of dichloromethane (2 × 30 mL). The organic phases were combined and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate.

After filtration, nonvolatiles were removed by aSAFE68 at 40 °C using an open/closed time combination of the pneumatic valve of 0.2 s/10 s. The distillate was concentrated to a final volume of 200 μL using a Vigreux column (50 × 1 cm) and a Bemelmans microdistillation device.69 The concentrate was analyzed by heart-cut GC–GC–HRMS. All quantitations were carried out in triplicates.

Peak areas of the geosmin peak and the (2H3)geosmin peak were extracted using ions m/z 165 for geosmin and m/z 168 for (2H3)geosmin. The concentration of geosmin in the samples was then calculated from the area counts of the geosmin peak, the area counts of the (2H3)geosmin peak, the amount of sample used, and the amount of (2H3)geosmin added by employing a calibration line equation. To obtain the calibration line equation, geosmin and (2H3)geosmin mixtures of different concentration ratios were analyzed under the same conditions, followed by linear regression. The resulting calibration line equation was y = 1.5161x – 0.1506, with y = [concentration of (2H3)geosmin]/[concentration of geosmin] and x = [peak area of (2H3)geosmin]/[peak area of geosmin].

Heart-cut GC–GC–HRMS instrument: A TRACE 1310 gas chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) was equipped with a TriPlus RSH autosampler and a programmed temperature vaporizing (PTV) injector. The oven was provided with an FID (250 °C base temperature) and a custom-made sniffing port70 (230 °C base temperature). The column was a DB-FFAP, 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). The carrier gas was helium at a 1 mL/min constant flow. The injection volume was 1 μL. The initial oven temperature of 40 °C was held for 2 min, followed by a gradient of 6 °C/min until a final temperature of 230 °C, which was held for 5 min. The end of the column was connected to a Deans Switch (S+H Analytik, Mönchengladbach), which transferred the column effluent time-programmed via deactivated fused silica capillaries (0.1 mm i.d.) either simultaneously to the FID and the sniffing port or to a liquid-nitrogen-cooled cold trap. The cold trap was connected to another TRACE 1310 gas chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which was also equipped with an FID (250 °C base temperature) and a custom-made sniffing port (230 °C base temperature). The GC column in this second oven was a DB-1701, 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness (Agilent) The initial oven temperature of 40 °C was held for 2 min, followed by a gradient of 6 °C/min until a final temperature of 240 °C, which was held for 5 min. The end of the column in the second oven was coupled to a Q Exactive GC Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated in the chemical ionization (CI) and high-resolution mode using isobutane as reagent gas and a scan range of m/z 160–187. Data were analyzed with Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Results and Discussion

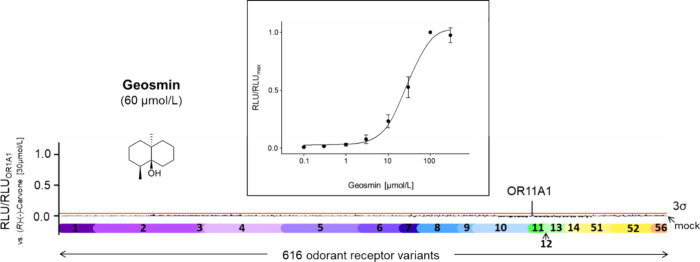

OR11A1 Solely Responded to Geosmin

The prominent odor quality of geosmin for humans suggested at least one OR that reacts selectively or specifically with this odorant. So far, however, no such receptor has been identified. Therefore, we screened 60 μmol/L geosmin against our human OR library comprising in total 616 cDNAs, coding for 386 human OR types, and 230 frequent variants, and identified OR11A1 as the sole responder, with signals above a 3σ-threshold (Figure 1). To verify these results, we established a concentration–response relationship of geosmin with human OR11A1. Indeed, geosmin activated OR11A1 in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 value of 27.97 ± 7.16 μmol/L.

Figure 1.

OR11A1 solely responded to geosmin. OR11A1 was exclusively activated in a screen of 616 OR variants against 60 μmol/L geosmin. Data were normalized to the response of OR1A1 to (R)-(−)-carvone (30 μmol/L; n = 1, measured in duplicates). The different OR families are color-coded; the red line indicates the 3σ-threshold. RLU = relative luminescence units. Inset: concentration–response relation of geosmin on OR11A1. Values are normalized to the highest signal of the receptor’s concentration/response relation (RLU/RLUmax). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4).

A cautionary note: We may have missed other geosmin-responsive ORs or responsive genetic variants, since (i) our receptor screening experiments did not include all known genetic human OR variants and (ii) some OR library receptors may not work with the assay used in our study. Some negative-deflecting RLU signals (Figure 1) might be an indication for the inhibition of a constitutive activity71 of some ORs. Thus, geosmin cannot be excluded as an inverse agonist for other receptors than OR11A1. However, despite largely identical measurement schemes, slight decreases and fluctuations of the luminescence signals within complex screening experiments may not be completely prevented.

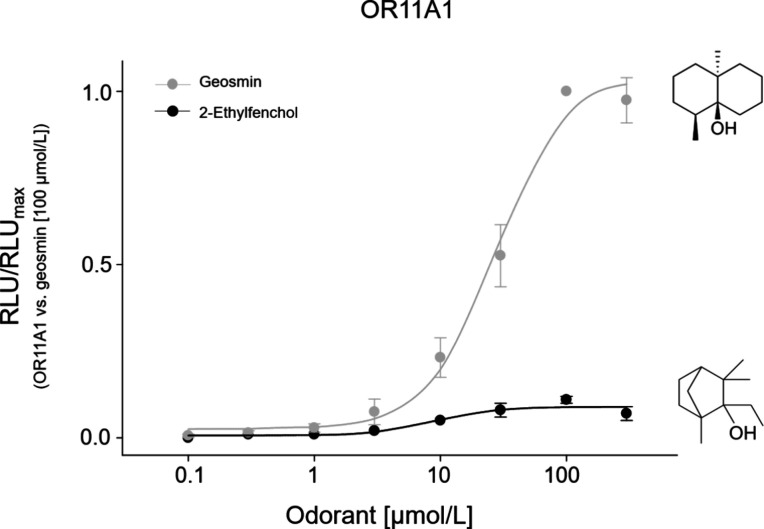

OR11A1 Is Tuned to Bicyclic Terpenoid Alcohols with Similar Odor Properties

For the majority of ORs, KFOs have been suggested as natural agonists.53,54,72,73 We therefore characterized the KFO agonist scope of human OR11A1 by screening the receptor against 177 chemically diverse, food aroma-relevant odorants published by Dunkel et al.53 Each KFO was tested in triplicate at a concentration of 300 μmol/L, and the corresponding receptor response amplitudes were normalized to the response of OR11A1 to geosmin. Figure S2 shows the activation pattern for OR11A1. Although ethyl pentanoate (FP1) and 4-ethenylphenol (FP3) exposed signals above the 3σ-threshold, and the signals of 1,8-cineol (FP2) and methionol (FP4) reached the 3σ-threshold (Figure S2A), we could not verify these KFOs as agonists since a concentration-dependent activation of OR11A1 by these compounds could not be validated in subsequent experiments (Figure S2B–E), suggesting false-positive (FP) signals.

The KFO screen did not reveal any further agonists for human OR11A1. Previous olfactory screening experiments have shown that OR11A1 appeared to be selective for both 2-ethylfenchol74−76 and fenchone;76 however, we could neither identify the latter as an agonist in our KFO screening nor establish concentration–response relations (Figure S3). So far, we have validated both compounds, geosmin and 2-ethylfenchol, as agonists for OR11A1 (Figure 2). In our hands, 2-ethylfenchol appeared to be a partial agonist of OR11A1, with a ninefold lower efficacy compared to geosmin, but with an EC50 value of 10.12 ± 1.25 μmol/L, that differed significantly from the EC50 value for geosmin (27.97 ± 7.16 μmol/L) (two sided t-test, p < 0.05), suggesting a slightly higher potency of 2-ethylfenchol in activating OR11A1 compared to geosmin.

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent activation of OR11A1 by bicyclic terpenoid alcohols of similar odor quality. Data were mock-subtracted and normalized to the highest response of OR11A1 to geosmin (100 μmol/L). Shown are the mean ± SD (n = 4). To facilitate a comparison with 2-ethylfenchol, the concentration–response relation of geosmin on OR11A1 was taken from Figure 1 (here in gray). RLU = relative luminescence units.

Both agonists for OR11A1, 2-ethylfenchol and geosmin, share common features in their structures and odor properties. Both substances are bicyclic terpenoid alcohols, with the hydroxy group in axial position and alpha methyl groups on both sides,77 and for both substances, similar “earthy/musty”, “muddy”, or “moldy” odor characteristics have been reported.2,77 2-Ethylfenchol and geosmin are both formed by soil-borne microorganisms17,78 that can contaminate food and cause “musty” off-flavors.47,78

For the perception of ecologically relevant odorants, such as semiochemicals, ORs have evolved as most sensitive, peripheral, molecular sensors.52,53 A previous study by Saraiva et al.52 suggested that a higher abundance of OR expression correlates with a higher sensitivity to detect ecologically relevant odorants. Indeed, OR11A1 appears to be one of the most highly expressed ORs in the human olfactory mucosa in terms of its transcript level,79 supporting the notion that a receptor, which is tuned to few structurally related substances, may have an eminent biological relevance. Thus, we hypothesize that OR11A1 has evolved to detect geosmin’s “musty” off-odor to warn humans against the consumption of spoiled food or drinking water.

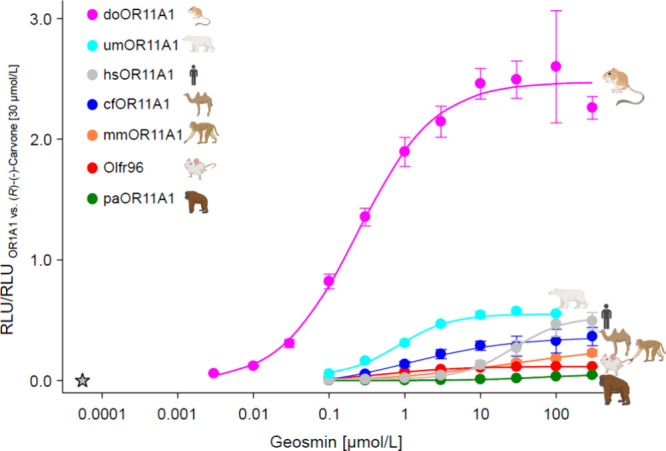

OR11A1 Orthologs Largely Differ in Their Sensitivities and Response Magnitudes toward Geosmin

Geosmin appears to be an important semiochemical across species. It has been reported that this compound seems to be of substantial relevance for a wide range of species and can trigger both repulsive and aversive behavior.38,40,80 We, therefore, analyzed and compared the respective receptor responses of OR11A1 from six different mammalian species toward geosmin by establishing concentration–response relationships (Figure 3, Table 1, and Figure S4).

Figure 3.

OR11A1 orthologs differ in sensitivity and efficacy toward geosmin. Concentration–response relationships of geosmin on OR11A1 orthologs. Data were mock-subtracted and normalized to the response of OR1A1 to (R)-(−)-carvone (30 μmol/L). Shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3–6). To facilitate comparisons, the concentration–response relation of geosmin on hsOR11A1 was taken from Figure 1 (here in gray). RLU = relative luminescence units. Star, human odor threshold. Icons were created with BioRender.com.

Indeed, geosmin concentration-dependently activated all six of our tested orthologs (kangaroo rat (Dipodomys ordii), mouse (Mus musculus), rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii), polar bear (Ursus maritimus), and camel (Camelus ferus)), with the kangaroo rat receptor being the most sensitive (EC50 = 0.24 ± 0.04 μmol/L). Interestingly, the human OR11A1 seems to be among the least potent receptors, with an EC50 of 27.97 ± 7.16 μmol/L, as compared to its heterospecic, functional homologues investigated in the present study (Figure 3 and Table 1). For the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii), a concentration-dependent activation of OR11A1 could be detected with an EC50 of 80.97 ± 33.23 μmol/L (Figure S4).

Altogether, OR11A1 orthologs from the two hominidae and the rhesus monkey displayed higher EC50 values for geosmin as compared to OR11A1 from the other species investigated (Table 1 and Figure S4). Do the receptors from human, orangutan, and rhesus monkey share amino acids or motifs that may confer a lower sensitivity? A sequence alignment revealed several positions where the hominidae and rhesus monkey OR11A1 receptors deviate from the other receptors investigated (Figure S1). These deviations include, for example, a charged amino acid within an N-terminal glycosylation consensus site, an isoleucine at position F 2.41,81 an isoleucine at a highly conserved, C-terminal, double leucine motif,82 and several deviations from amino acids that have been proposed to be important for the structural stability of ORs83 (Figure S1). Whether these deviations indeed are causative for the lower EC50 values of the hominidae and rhesus monkey OR11A1 receptors will have to be investigated in future experiments.

In addition, we assessed the different efficacies of all orthologs in responding to geosmin and identified the kangaroo rat receptor as the most effective responder (Figure 3). The largely different signaling efficacies of OR11A1 orthologs, however, revealed no correlation with their cell surface expression (Figure S5). Although the kangaroo rat receptor displayed a better surface expression than those of the camel or mouse receptors, OR11A1 from orangutan or rhesus monkey, however, showed a similarly good cell surface expression, despite markedly lower geosmin-induced signaling efficacies. Thus, other factors are likely responsible for the individual signaling efficacies of OR11A1 orthologs. What may be the reason for the large variation in potency and efficacy of geosmin on OR11A1 across species? We hypothesize that there might be an interplay of several factors, such as lifestyle, water accessibility, and diet. As the smell of geosmin is associated with rain, and, thus, freshwater, geosmin-rich locations provide a potential source of water. Moreover, the bicyclic alcohol seems to make an important contribution in the food foraging of insects as well as larger animals: geosmin is produced by soil-borne, spore-forming bacteria whose odor is known to attract animals such as soil-dwelling arthropods (e.g., springtails), which consume these bacteria and, thus, ensure the spread of their spores.84 Springtails, in turn, attract larger arthropods such as spiders, which feed on springtails,85 or queen ants, which prefer to choose their nesting site in soil rich in actinomycetota and geosmin.86 The resulting accumulation of a wide variety of arthropods could subsequently help larger animals, like mice, that feed on these larger arthropods,87 to recognize and detect food. This might also be true for the omnivorous rhesus monkey, found in both tropical and temperate climates, where it lives in forested, semidesert, and swampy habitats. It has adapted its diet to the respective conditions, including plants, insects, fish, and crabs.88

Chemically mediated interactions with, and adaptation to different ecosystems, thus, may be causative for the vastly different potencies and signaling efficiencies of geosmin on OR11A1 orthologs from the two hominidae as compared to those of the other species (Figure 3 and Table 1). For example, due to its arid habitat on sandy soils or sand dunes,89,90 the kangaroo rat seems to be able to feed on plant material without access to drinking water91 and is therefore ideally adapted to its environment. Studies have shown that kangaroo rats feed on prickly pear and cactus seeds,92,93 which are known producers of geosmin,28 as well as on arthropods,89 containing ∼75% water by mass,94 which are found in increased abundance and diversity in the burrows of kangaroo rats.95 Our finding that doOR11A1 showed both the lowest EC50 value and the best efficacy toward geosmin led us to hypothesize that geosmin’s chemosensory perception is eminently involved in the kangaroo rat’s search for food as well as in meeting its water requirements, thus helping to ensure its survival in the desert.

In contrast, orangutans spend most of their time in trees, where they feed mainly on leaves, fruits, and only rarely on insects.96 Their water needs are mainly met by their plant food and water from tree holes,97 suggesting their independence from geosmin-associated environments, which likely also applies to humans. This is in line with the observed rather low chemoreceptive sensitivity toward geosmin of OR11A1 from the two hominidae (orangutan and human), as compared to a several orders of magnitude higher sensitivity toward geosmin of the other OR11A1 orthologs in our in vitro assay (Figure 3 and Table 1).

How sensitive toward geosmin is our GloSensor-based in vitro assay as compared to the human nose? The human OT for geosmin is in the picomolar range, which is several orders of magnitude lower than the response threshold for geosmin of human OR11A1 in our cell-based in vitro assay. Considerable discrepancies between modest sensitivities of isolated single olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs), often determined electrophysiologically,98,99 and much lower behavioral odorant detection thresholds100,101 are long known. To what degree a behavioral detection threshold is determined by certain factors,102 such as receptor sensitivity,103 OR surface expression,82,83 number of ORNs expressing the same OR,104 axonal convergence in the olfactory bulb,105 and processing at higher olfactory brain regions, particularly in mammals, remains to be investigated. However, the detection threshold for geosmin of the supersensitive OR11A1 ortholog from kangaroo rat (doOR11A1) in our in vitro assay indeed overlaps with the dynamic detection range of the human nose at low nanomolar geosmin concentrations, advocating doOR11A1 as a putative sensor tool for, e.g., the detection of geosmin-like malodors.

Mice have been shown to detect mold-associated (nongeosmin) odorants in the ng/L range,106 presumably to avoid potential toxic compounds in putrefying food. This goes along with our findings of mouse OR11A1 (Or11a1/Olfr96) being able to detect geosmin at comparatively low micromolar concentrations in our in vitro assay (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Surprisingly, the polar bear’s OR11A1 receptor showed a sensitivity for geosmin similar to the sensitivities of the receptor orthologs from mouse and camel (Figure 3 and Table 1). The OR family of genes has been identified as a common target of selection during polar bear evolution.107 In particular, a decrease in copy numbers among OR genes from polar bears, as compared to, e.g., brown bears, was recently identified as a potential source of rapid ecological adaptation of polar bears.108 Rinker et al. suggested that polar bear olfaction has evolved to become more specific, displaying a less diverse OR repertoire,108 maybe as an adaptation to the less complex chemical ecology of arctic environments.109 On the other hand, the polar bear has the largest known surface area of the olfactory epithelium among canid and arctoid carnivorans.110 Moreover, its olfactory bulb size has been reported to correlate with home range size among carnivores.111 An assumed polar bear’s higher olfactory specificity and sensitivity may, thus, reflect the ecological adaptation toward a hypercarnivorous phenotype and the detection of prey or mates over greater distances. Indeed, polar bears may travel or swim long distances.112 In this context, a gradient of soil-borne geosmin, washed out by rain, surface waters, and rivers at μg/L concentrations16,113−115 into the ocean, may serve as a well-detectable homing signal toward land for polar bears, as has been suggested also for glass eel migration toward freshwater.116

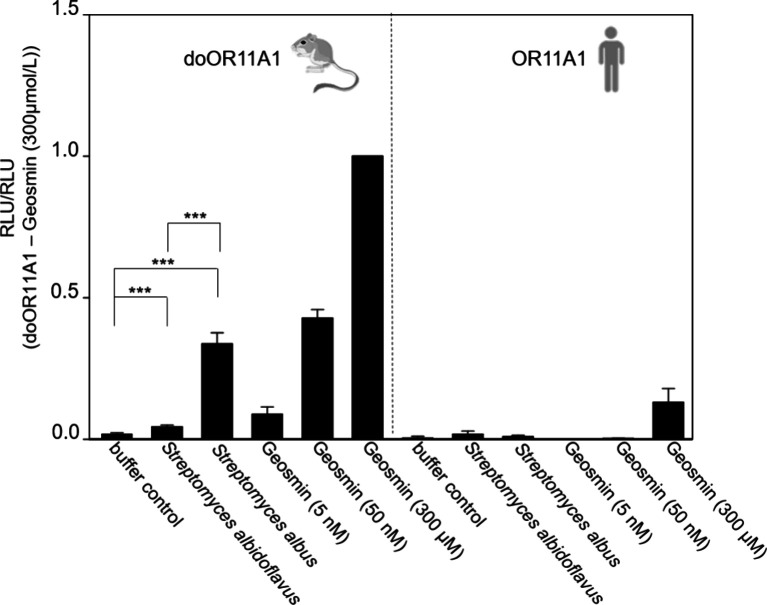

doOR11A1 Is Capable of Detecting Geosmin in Bacterial Extracts at Low Nanomolar Concentrations

Typical geosmin-producing bacteria include Streptomyces species, such as S. albus and S. albidoflavus.17,18 To investigate whether the OR11A1 receptor can detect geosmin produced by these bacteria in combination with other substances produced at the same time, we cultured both bacterial strains on BHI agar plates. After washing off the plates with luminescence assay buffer and centrifugation of the harvested volume, we quantitated geosmin in both strands’ sterile-filtered extracts by heart-cut GC–GC–HRMS after solvent-assisted flavor evaporation (aSAFE), using (2H3)geosmin as an internal standard. The S. albus extract had an about 10-fold higher geosmin concentration as compared to the extract from S. albidoflavus (Table 2).

Table 2. Concentrations of Geosmin in Individual Bacterial Extracts and the Buffer Control.

| concentration (μg/L) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample | exp. 1a | exp. 2a | exp. 3a | mean ± SD (CV)b | concentration (nmol/L) |

| S. albidoflavus | 0.945 | 0.878 | 0.855 | 0.893 ± 0.047 (5%) | 4.9 |

| S. albus | 9.91 | 8.98 | 9.71 | 9.53 ± 0.49 (5%) | 52.3 |

| buffer control | ≤0.23c | ≤0.35c | ≤0.28c | ≤1.9 | |

Individual concentrations were rounded.

Mean values were calculated from the unrounded concentrations of the individual experiments and finally rounded to three digits; SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation.

No analyte peak was observed; values were derived from the integration of the background noise.

We applied both sterile-filtered extracts to cells transfected with either human OR11A1, or its ortholog from the kangaroo rat, doOR11A1. Notably, only doOR11A1 was activated by the extracts from both S. albidoflavus and S. albus, proportionally to the respective extract’s geosmin concentration in our in vitro assay (Figure 4). Both extracts contained geosmin at low nanomolar concentrations (Table 2), which are within the detection range of doOR11A1 but are far below the detection range of the human OR11A1 in our in vitro assay (Figure 4, compare Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Extracts from geosmin-producing bacterial strains significantly activate the doOR11A1 receptor. doOR11A1-transfected cells were stimulated with sterile-filtered extracts of S. albus and S. albidoflavus. Data were mock-subtracted and normalized to the response of doOR11A1 against 300 μmol/L geosmin. ***p ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t test). Shown are the mean ± SD (n = 11). RLU = relative luminescence units.

In summary, our results suggest human OR11A1 as our best sensor for the food- and water-deteriorating malodor compound geosmin, serving as an olfactory chemoreceptor warning system in the context of food choice. Our discovery of OR11A1 receptor isofunctional homologues across species, with up to 100-fold higher sensitivities for geosmin as compared to the human receptor, points to geosmin’s biological relevance as semiochemical. Beyond, the discovery of supersensitive receptors for geosmin promises their application in receptor-based sensors,117,118 e.g., for quality control purposes in food production and storage processes or as a tool to monitor the water quality in freshwater reservoirs.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Therese Hård for her help in obtaining an orangutan saliva sample. We thank Christine Fritsch for preparing the Streptomyces extracts, and Julia Bock and Monika Riedmaier for their skillful technical assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- KFO

key food odorant

- OR

odorant receptor

- ORN

olfactory receptor neuron

- OT

odor detection threshold

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jafc.4c01515.

Experimental details on investigated odorants, oligonucleotides for molecular cloning, the cDNA expression plasmid OR library, and the validation of false-positive screening signals (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Coca-Ruíz V.; Suárez I.; Aleu J.; Collado I. G. Structures, Occurrences and Biosynthesis of 11,12,13-Tri-nor-Sesquiterpenes, an Intriguing Class of Bioactive Metabolites. Plants 2022, 11 (6), 769. 10.3390/plants11060769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber N. N.; Lechevalier H. A. geosmin, an earthly-smelling substance isolated from actinomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. 1965, 13 (6), 935–8. 10.1128/am.13.6.935-938.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm-Lehto P. C.; Vielma J. Controlling of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol induced off-flavours in recirculating aquaculture system farmed fish—A review. Aquaculture Research 2019, 50 (1), 9–28. 10.1111/are.13881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L. l.; Han F.; Fodjo E. K.; Zhai W.; Huang X. Y.; Kong C.; Shi Y. F.; Cai Y. Q.; Samanidou V. F. An Effective and Efficient Sample Preparation Method for 2-Methyl-Isoborneol and geosmin in Fish and Their Analysis by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Anal Chem. 2021, 2021, 1. 10.1155/2021/9980212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hack M. E.; El-Saadony M. T.; Elbestawy A. R.; Ellakany H. F.; Abaza S. S.; Geneedy A. M.; Salem H. M.; Taha A. E.; Swelum A. A.; Omer F. A.; AbuQamar S. F.; El-Tarabily K. A. Undesirable odour substances (geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol) in water environment: Sources, impacts and removal strategies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 178, 113579 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttery R. G.; Guadagni D. G.; Ling L. C. geosmin, a Musty Off-Flavor of Dry Beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1976, 24 (2), 419–420. 10.1021/jf60204a050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli C.; Neiens S. D.; Steinhaus M. Molecular Background of a Moldy-Musty Off-Flavor in Cocoa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69 (15), 4501–4508. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c00564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Guerche S.; Chamont S.; Blancard D.; Dubourdieu D.; Darriet P. Origin of (−)-geosmin on grapes: on the complementary action of two fungi, botrytis cinerea and penicillium expansum. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2005, 88 (2), 131–9. 10.1007/s10482-005-3872-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Valle H.; Silva L. C.; Paterson R. R.; Oliveira J. M.; Venancio A.; Lima N. Microextraction and Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry for improved analysis of geosmin and other fungal ″off″ Volatiles in grape juice. J. Microbiol Methods 2010, 83 (1), 48–52. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr M.; Cocco E.; Lenouvel A.; Guignard C.; Evers D. Earthy and Fresh Mushroom Off-Flavors in Wine: Optimized Remedial Treatments. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 64 (4), 545–549. 10.5344/ajev.2013.13061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darriet P.; Pons M.; Lamy S.; Dubourdieu D. Identification and quantification of geosmin, an earthy odorant contaminating wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48 (10), 4835–8. 10.1021/jf0007683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson S. B.; Brownlee B.; Satchwill T.; Hargesheimer E. E. Quantitative analysis of trace levels of geosmin and MIB in source and drinking water using headspace SPME. Water Res. 2000, 34 (10), 2818–2828. 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00027-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jüttner F.; Watson S. B. Biochemical and ecological control of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in source waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73 (14), 4395–406. 10.1128/AEM.02250-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap C. R.; Sklenar K. S.; Blake L. J. A Costly Endeavor: Addressing Algae Problems in a Water Supply. J. Am. Water Works Ass 2015, 107 (5), E255–E262. 10.5942/jawwa.2015.107.0055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha S.; Tijani J. O.; Ndamitso M. M.; Abdulkareem A. S.; Shuaib D. T.; Mohammed A. K. A critical review on geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in water: sources, effects, detection, and removal techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193 (4), 204. 10.1007/s10661-021-08980-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asquith E.; Evans C.; Dunstan R. H.; Geary P.; Cole B. Distribution, abundance and activity of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol-producing Streptomyces in drinking water reservoirs. Water Res. 2018, 145, 30–38. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churro C.; Semedo-Aguiar A. P.; Silva A. D.; Pereira-Leal J. B.; Leite R. B. A novel cyanobacterial geosmin producer, revising GeoA distribution and dispersion patterns in Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10 (1), 8679. 10.1038/s41598-020-64774-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader K. K.; Summerfelt S. T. Distribution of Off-Flavor Compounds and Isolation of geosmin-Producing Bacteria in a Series of Water Recirculating Systems for Rainbow Trout Culture. North American Journal of Aquaculture 2010, 72 (1), 1–9. 10.1577/A09-009.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gust B.; Challis G. L.; Fowler K.; Kieser T.; Chater K. F. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100 (4), 1541–6. 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitlin B.; Watson S. B. Actinomycetes in relation to taste and odour in drinking water: myths, tenets and truths. Water Res. 2006, 40 (9), 1741–53. 10.1016/j.watres.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre G.; Hwang C. J.; Krasner S. W.; McGuire M. J. geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol from cyanobacteria in three water supply systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1982, 43 (3), 708–14. 10.1128/aem.43.3.708-714.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik B.; Lindberg P. Terpenoids and their biosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Life (Basel) 2015, 5 (1), 269–93. 10.3390/life5010269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickschat J. S.; Bode H. B.; Mahmud T.; Müller R.; Schulz S. A novel type of geosmin biosynthesis in myxobacteria. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70 (13), 5174–82. 10.1021/jo050449g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaget V.; Almuhtaram H.; Kibuye F.; Hobson P.; Zamyadi A.; Wert E.; Brookes J. D. Benthic cyanobacteria: A utility-centred field study. Harmful Algae 2022, 113, 102185 10.1016/j.hal.2022.102185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J.; Sparks N.; Sydney N.; Livingstone P. G.; Cookson A. R.; Whitworth D. E. Comparative Genomics and Pan-Genomics of the Myxococcaceae, including a Description of Five Novel Species: Myxococcus eversor sp. nov., Myxococcus llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogochensis sp. nov., Myxococcus vastator sp. nov., Pyxidicoccus caerfyrddinensis sp. nov., and Pyxidicoccus trucidator sp. nov. Genome Biol. Evol 2020, 12 (12), 2289–2302. 10.1093/gbe/evaa212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattheis J. P.; Roberts R. G. Identification of geosmin as a volatile metabolite of Penicillium expansum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58 (9), 3170–2. 10.1128/aem.58.9.3170-3172.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacha N.; Echarki Z.; Mathieu F.; Lebrihi A. Development of a novel quantitative PCR assay as a measurement for the presence of geosmin-producing fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 118 (5), 1144–51. 10.1111/jam.12747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpberger B. O.; Jux A.; Kunert M.; Boland W.; Wittmann D. Musty-earthy scent in cactus flowers: Characteristics of floral scent production in dehydrogeosmin-producing cacti. International Journal of Plant Sciences 2004, 165 (6), 1007–1015. 10.1086/423878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G.; Edwards C. G.; Fellman J. K.; Mattinson D. S.; Navazio J. Biosynthetic origin of geosmin in red beets (Beta vulgaris L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51 (4), 1026–9. 10.1021/jf020905r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmassry M. M.; Farag M. A.; Preissner R.; Gohlke B. O.; Piechulla B.; Lemfack M. C. Sixty-One Volatiles Have Phylogenetic Signals Across Bacterial Domain and Fungal Kingdom. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 557253 10.3389/fmicb.2020.557253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.; He X.; Cane D. E. Biosynthesis of the earthy odorant geosmin by a bifunctional Streptomyces coelicolor enzyme. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3 (11), 711–5. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S.; Ohtani S.; Godo T.; Nojiri Y.; Saki Y.; Esumi T.; Kamiya H. Identification of geosmin biosynthetic gene in geosmin-producing colonial cyanobacteria Coelosphaerium sp.. and isolation of geosmin non-producing Coelosphaerium sp. from brackish Lake Shinji in Japan. Harmful Algae 2019, 84, 19–26. 10.1016/j.hal.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Sanchez L.; Singh K. S.; Avalos M.; van Wezel G. P.; Dickschat J. S.; Garbeva P. Phylogenomic analyses and distribution of terpene synthases among Streptomyces. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 1181–1193. 10.3762/bjoc.15.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Song G.; Li Y.; Yu G.; Hou X.; Gan Z.; Li R. The diversity, origin, and evolutionary analysis of geosmin synthase gene in cyanobacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 789–796. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Dickschat J. S. A Detailed View on geosmin Biosynthesis. Chembiochem 2023, 24 (12), e202300101 10.1002/cbic.202300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbeva P.; Avalos M.; Ulanova D.; van Wezel G. P.; Dickschat J. S. Volatile sensation: The chemical ecology of the earthy odorant geosmin. Environ. Microbiol 2023, 25 (9), 1565–1574. 10.1111/1462-2920.16381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M.; Chamaille-Jammes S.; Hammerbacher A.; Shrader A. M. African elephants can detect water from natural and artificial sources via olfactory cues. Anim Cogn 2022, 25 (1), 53–61. 10.1007/s10071-021-01531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo N.; Wolff G. H.; Costa-da-Silva A. L.; Arribas R.; Triana M. F.; Gugger M.; Riffell J. A.; DeGennaro M.; Stensmyr M. C. geosmin Attracts Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes to oviposition Sites. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30 (1), 127–134. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaroubi L.; Ozugergin I.; Mastronardi K.; Imfeld A.; Law C.; Gélinas Y.; Piekny A.; Findlay B. L.; Nojiri H. The Ubiquitous Soil Terpene geosmin Acts as a Warning Chemical. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88 (7), e0009322 10.1128/aem.00093-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensmyr M. C.; Dweck H. K.; Farhan A.; Ibba I.; Strutz A.; Mukunda L.; Linz J.; Grabe V.; Steck K.; Lavista-Llanos S.; Wicher D.; Sachse S.; Knaden M.; Becher P. G.; Seki Y.; Hansson B. S. A conserved dedicated olfactory circuit for detecting harmful microbes in Drosophila. Cell 2012, 151 (6), 1345–57. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W. F.; Horth H.; Crane R.; Ogden T.; Arnott M. Taste and odour threshold concentrations of potential potable water contaminants. Water Res. 1996, 30 (2), 331–340. 10.1016/0043-1354(95)00173-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krasner S. W.; Hwang C. J.; McGuire M. J. A Standard Method for Quantification of Earthy-Musty odorants in Water, Sediments, and Algal Cultures. Water Sci. Technol. 1983, 15 (6–7), 127–138. 10.2166/wst.1983.0137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omur-Ozbek P.; Little J. C.; Dietrich A. M. Ability of humans to smell geosmin, 2-MIB and nonadienal in indoor air when using contaminated drinking water. Water science and technology: a journal of the International Association on Water Pollution Research 2007, 55 (5), 249–56. 10.2166/wst.2007.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley R. The nose as a stereochemist. Enantiomers and odor. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106 (9), 4099–112. 10.1021/cr050049t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta C.; Prakash D.; Gupta S. A Biotechnological Approach to Microbial Based Perfumes and Flavours. J. Microbiol. Exp. 2015, 2 (1), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha S.; Tijani J. O.; Ndamitso M. M.; Abdulkareem A. S.; Shuaib D. T.; Mohammed A. K. A critical review on geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in water: sources, effects, detection, and removal techniques. Environ. Monit Assess 2021, 193 (4), 204. 10.1007/s10661-021-08980-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liato V.; Aider M. geosmin as a source of the earthy-musty smell in fruits, vegetables and water: Origins, impact on foods and water, and review of the removing techniques. Chemosphere 2017, 181, 9–18. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck L.; Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell 1991, 65 (1), 175–87. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimura Y. Evolutionary dynamics of olfactory receptor genes in chordates: interaction between environments and genomic contents. Hum Genomics 2009, 4 (2), 107–18. 10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malnic B.; Godfrey P. A.; Buck L. B. The human olfactory receptor gene family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101 (8), 2584–9. 10.1073/pnas.0307882100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olender T.; Lancet D.; Nebert D. W. Update on the olfactory receptor (OR) gene superfamily. Human genomics 2008, 3 (1), 87–97. 10.1186/1479-7364-3-1-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva L. R.; Riveros-McKay F.; Mezzavilla M.; Abou-Moussa E. H.; Arayata C. J.; Makhlouf M.; Trimmer C.; Ibarra-Soria X.; Khan M.; Van Gerven L.; Jorissen M.; Gibbs M.; O’Flynn C.; McGrane S.; Mombaerts P.; Marioni J. C.; Mainland J. D.; Logan D. W. A transcriptomic atlas of mammalian olfactory mucosae reveals an evolutionary influence on food odor detection in humans. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5 (7), eaax0396 10.1126/sciadv.aax0396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel A.; Steinhaus M.; Kotthoff M.; Nowak B.; Krautwurst D.; Schieberle P.; Hofmann T. Nature’s chemical signatures in human olfaction: a foodborne perspective for future biotechnology. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53 (28), 7124–43. 10.1002/anie.201309508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag F.; Frey T.; Hoffmann S.; Kreissl J.; Stein J.; Kobal G.; Hauner H.; Krautwurst D. The multi-faceted food odorant 4-methylphenol selectively activates evolutionary conserved receptor OR9Q2. Food Chem. 2023, 426, 136492 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.136492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp U. B. Olfactory signalling in vertebrates and insects: differences and commonalities. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2010, 11 (3), 188–200. 10.1038/nrn2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Pellegrino M.; Nakagawa T.; Nakagawa T.; Vosshall L. B.; Touhara K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature 2008, 13, 1002. 10.1038/nature06850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicher D.; Schäfer R.; Bauernfeind R.; Stensmyr M. C.; Heller R.; Heinemann S. H.; Hansson B. S. Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature 2008, 13, 1007. 10.1038/nature06861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe F.; Geithe C.; Fiedler J.; Krautwurst D. A bi-functional IL-6-HaloTag® as a tool to measure the cell-surface expression of recombinant odorant receptors and to facilitate their activity quantification. J. Biol. Methods 2017, 4 (4), e82 10.14440/jbm.2017.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkowski B.; Fan F.; Wood K. Engineered luciferases for molecular sensing in living cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009, 20 (1), 14–18. 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe F.; Polster J.; Geithe C.; Kotthoff M.; Schieberle P.; Krautwurst D. OR2M3: A Highly Specific and Narrowly Tuned Human Odorant Receptor for the Sensitive Detection of Onion Key Food Odorant 3-Mercapto-2-methylpentan-1-ol. Chemical Senses 2017, 42 (3), 195–210. 10.1093/chemse/bjw118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geithe C.; Noe F.; Kreissl J.; Krautwurst D. The Broadly Tuned Odorant Receptor OR1A1 is Highly Selective for 3-Methyl-2,4-nonanedione, a Key Food Odorant in Aged Wines, Tea, and Other Foods. Chemical Senses 2017, 42 (3), 181–193. 10.1093/chemse/bjw117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli C.; Kreissl J.; Steinhaus M. Enantioselective synthesis of tri-deuterated (−)-geosmin to be used as internal standard in quantitation assays. J. Labelled Comp Radiopharm 2020, 63 (11), 476–481. 10.1002/jlcr.3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. T.; Taylor W. R.; Thornton J. M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci 1992, 8 (3), 275–82. 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Stecher G.; Li M.; Knyaz C.; Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35 (6), 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham F. L.; Smiley J.; Russell W. C.; Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen Virol 1977, 36 (1), 59–74. 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geithe C.; Andersen G.; Malki A.; Krautwurst D. A Butter Aroma Recombinate Activates Human Class-I Odorant Receptors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63 (43), 9410–9420. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLean A.; Munson P. J.; Rodbard D. Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 1978, 235 (2), E97. 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpberger P.; Stübner C. A.; Steinhaus M. Development and evaluation of an automated solvent-assisted flavour evaporation (aSAFE). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248 (10), 2591–2602. 10.1007/s00217-022-04072-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bemelmans J. M. H., Review of isolation and concentration techniques. In Progress in Flavour Research, Land G. G.; Nursten H. E., Eds. Applied Science Publishers: London, U.K., 1979; pp 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhaus M.; Sinuco D.; Polster J.; Osorio C.; Schieberle P. Characterization of the aroma-active compounds in pink guava (Psidium guajava, L.) by application of the aroma extract dilution analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56 (11), 4120–7. 10.1021/jf8005245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisert J. Origin of basal activity in mammalian olfactory receptor neurons. J. Gen Physiol 2010, 136 (5), 529–40. 10.1085/jgp.201010528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautwurst D.; Kotthoff M. A hit map-based statistical method to predict best ligands for orphan olfactory receptors: natural key odorants versus ″lock picks″. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1003, 85–97. 10.1007/978-1-62703-377-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinek P.; Haag F.; Geithe C.; Krautwurst D. An evolutionary conserved olfactory receptor for foodborne and semiochemical alkylpyrazines. Faseb J. 2021, 35 (6), e21638 10.1096/fj.202100224R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adipietro K. A.; Mainland J. D.; Matsunami H. Functional evolution of mammalian odorant receptors. PLoS Genet 2012, 8 (7), e1002821 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainland J. D.; Keller A.; Li Y. R.; Zhou T.; Trimmer C.; Snyder L. L.; Moberly A. H.; Adipietro K. A.; Liu W. L.; Zhuang H.; Zhan S.; Lee S. S.; Lin A.; Matsunami H. The missense of smell: functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire. Nat. Neurosci 2014, 17 (1), 114–20. 10.1038/nn.3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimmer C.; Keller A.; Murphy N. R.; Snyder L. L.; Willer J. R.; Nagai M. H.; Katsanis N.; Vosshall L. B.; Matsunami H.; Mainland J. D. Genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire alters odor perception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116 (19), 9475–9480. 10.1073/pnas.1804106115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak E.; Trotier D.; Baliguet E. Odor similarities in structurally related odorants. Chemical Senses 1978, 3 (4), 369–380. 10.1093/chemse/3.4.369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Callejon R. M.; Ubeda C.; Rios-Reina R.; Morales M. L.; Troncoso A. M. Recent developments in the analysis of musty odour compounds in water and wine: A review. J. Chromatogr A 2016, 1428, 72–85. 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeurgt C.; Wilkin F.; Tarabichi M.; Gregoire F.; Dumont J. E.; Chatelain P. Profiling of olfactory receptor gene expression in whole human olfactory mucosa. PLoS One 2014, 9 (5), e96333 10.1371/journal.pone.0096333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro-Morrison T.; Diamandis E. P.; Rifai N.; Weetjens B. J.; Pennazza G.; de Boer N. K.; Bomers M. K. Animal olfactory detection of disease: promises and pitfalls. Clin Chem. 2014, 60 (12), 1473–9. 10.1373/clinchem.2014.231282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros J. A.; Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995, 25, 366–428. 10.1016/S1043-9471(05)80049-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kotthoff M.; Bauer J.; Haag F.; Krautwurst D. Conserved C-terminal motifs in odorant receptors instruct their cell surface expression and cAMP signaling. Faseb J. 2021, 35 (2), e21274 10.1096/fj.202000182RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami K.; de March C. A.; Nagai M. H.; Ghosh S.; Do M.; Sharma R.; Bruguera E. S.; Lu Y. E.; Fukutani Y.; Vaidehi N.; Yohda M.; Matsunami H. Structural instability and divergence from conserved residues underlie intracellular retention of mammalian odorant receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (6), 2957–2967. 10.1073/pnas.1915520117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher P. G.; Verschut V.; Bibb M. J.; Bush M. J.; Molnár B. P.; Barane E.; Al-Bassam M. M.; Chandra G.; Song L.; Challis G. L.; Buttner M. J.; Flärdh K. Developmentally regulated Volatiles geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol attract a soil arthropod to Streptomyces bacteria promoting spore dispersal. Nat. Microbiol 2020, 5 (6), 821–829. 10.1038/s41564-020-0697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toju H.; Baba Y. G. DNA metabarcoding of spiders, insects, and springtails for exploring potential linkage between above- and below-ground food webs. Zoological Lett. 2018, 4, 4. 10.1186/s40851-018-0088-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Ren L.; Li H.; Schmidt A.; Gershenzon J.; Lu Y.; Cheng D. The nesting preference of an invasive ant is associated with the cues produced by actinobacteria in soil. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16 (9), e1008800 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald B.; Daniel M.; Fitzgerald A.; Karl B.; Meads M.; Notman P. Factors affecting the numbers of house mice (Mus musculus) in hard beech (Nothofagus truncata) forest. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1996, 26 (2), 237–249. 10.1080/03014223.1996.9517512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E. B.; Brent L. J. N.; Snyder-Mackler N.; Singh M.; Sengupta A.; Khatiwada S.; Malaivijitnond S.; Qi Hai Z.; Higham J. P. The rhesus macaque as a success story of the Anthropocene. Elife 2022, 11, e78169 10.7554/eLife.78169.sa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison T. E.; Best T. L. Dipodomys ordii. Mammalian Species 1990, 353. [Google Scholar]

- Sipos M. P.; Andersen M. C.; Whitford W. G.; Gould W. R. Graminivory by Dipodomys ordii and Dipodomys merriami on Four Species of Perennial Grasses. Southwestern Naturalist 2002, 47 (2), 276–281. 10.2307/3672915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Nielsen K.; Schmidt-Nielsen B. Water metabolism of desert mammals. Physiol Rev. 1952, 32 (2), 135–66. 10.1152/physrev.1952.32.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass R. J. Demographic monitoring of Wright fishhook cactus. Proc. RMRS. 1998, 23, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Orr T. J.; Newsome S. D.; Wolf B. O. Cacti supply limited nutrients to a desert rodent community. Oecologia 2015, 178 (4), 1045–62. 10.1007/s00442-015-3304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. P.Birds and mammals on an insect diet: a primer on diet composition analysis in relation to ecological energetics. Studies Avian Biol. 199013. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson A. D.; Lightfoot D. C. Interactive effects of keystone rodents on the structure of desert grassland arthropod communities. Ecography 2007, 30 (4), 515–525. 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.05032.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rijksen H. D.; Meijaard E., Ecology and Natural History. In Our Vanishing Relative: The Status of Wild Orang-Utans at the Close of the Twentieth Century; Springer Dordrecht: 1999; pp 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schaik C. P.; Ancrenaz M.; Djojoasmoro R.; Knott C. D.; Morrogh-Bernard H. C.; Kisar N. O.; Utami Atmoko S. S.; Van Noordwijk M. A.. Orangutan cultures revisited. In Orangutans: Geographic Variation in Behavioral Ecology and Conservation, Oxford University Press: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grosmaitre X.; Vassalli A.; Mombaerts P.; Shepherd G. M.; Ma M. Odorant responses of olfactory sensory neurons expressing the odorant receptor MOR23: a patch clamp analysis in gene-targeted mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103 (6), 1970–5. 10.1073/pnas.0508491103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein S.; Picco C.; Menini A. The relation between stimulus and response in olfactory receptor cells of the tiger salamander. J. Physiol 1993, 468, 1–10. 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L.; Laska M. Ultra-high olfactory sensitivity for the human sperm-attractant aromatic aldehyde bourgeonal in CD-1 mice. Neurosci Res. 2011, 71 (4), 355–60. 10.1016/j.neures.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodyak N.; Slotnick B. Performance of mice in an automated olfactometer: odor detection, discrimination and odor memory. Chem. Senses 1999, 24 (6), 637–45. 10.1093/chemse/24.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin M. D.; Cain W. S. Determinants of measured olfactory sensitivity. Percept Psychophys 1986, 39 (4), 281–6. 10.3758/BF03204936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan A.; Cichy A.; Zhang J.; Miguel K.; Feinstein P.; Rinberg D.; Bozza T. Single olfactory receptors set odor detection thresholds. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 2887. 10.1038/s41467-018-05129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandawat V.; Reisert J.; Yau K. W. Signaling by olfactory receptor neurons near threshold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107 (43), 18682–7. 10.1073/pnas.1004571107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisami E. A proposed relationship between increases in the number of olfactory receptor neurons, convergence ratio and sensitivity in the developing rat. Brain Res. Dev Brain Res. 1989, 46 (1), 9–19. 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto L.; Salazar L. T. H.; Laska M. Olfactory sensitivity for mold-associated odorants in CD-1 mice and spider monkeys. J. Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 2018, 204 (9–10), 821–833. 10.1007/s00359-018-1285-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Lorenzen E. D.; Fumagalli M.; Li B.; Harris K.; Xiong Z.; Zhou L.; Korneliussen T. S.; Somel M.; Babbitt C.; Wray G.; Li J.; He W.; Wang Z.; Fu W.; Xiang X.; Morgan C. C.; Doherty A.; O’Connell M. J.; McInerney J. O.; Born E. W.; Dalen L.; Dietz R.; Orlando L.; Sonne C.; Zhang G.; Nielsen R.; Willerslev E.; Wang J. Population genomics reveal recent speciation and rapid evolutionary adaptation in polar bears. Cell 2014, 157 (4), 785–94. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker D. C.; Specian N. K.; Zhao S.; Gibbons J. G. Polar bear evolution is marked by rapid changes in gene copy number in response to dietary shift. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116 (27), 13446–13451. 10.1073/pnas.1901093116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig M. L.Species Diversity in Space and Time; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Green P. A.; Van Valkenburgh B.; Pang B.; Bird D.; Rowe T.; Curtis A. Respiratory and olfactory turbinal size in canid and arctoid carnivorans. J. Anat 2012, 221 (6), 609–21. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittleman J. L. Carnivore Olfactory-Bulb Size - Allometry, Phylogeny and Ecology. Journal of Zoology 1991, 225 (2), 253–272. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1991.tb03815.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pilfold N. W.; McCall A.; Derocher A. E.; Lunn N. J.; Richardson E. Migratory response of polar bears to sea ice loss: to swim or not to swim. Ecography 2017, 40 (1), 189–199. 10.1111/ecog.02109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J.-K.; Park Y.; Kim N.-Y.; Hwang S.-J. Downstream Transport of geosmin Based on Harmful Cyanobacterial Outbreak Upstream in a Reservoir Cascade. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19 (15), 9294. 10.3390/ijerph19159294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwan B. J.; Kim N.; Kang T. G.; Kim B.-H.; Byeon M.-S. Study of the cause of the generation of odor compounds (geosmin and 2- methylisoborneol) in the Han River system, the drinking water source, Republic of Korea. Water Supply 2023, 23 (3), 1081–1093. 10.2166/ws.2023.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa C.; Abril M.; Bretxa È.; Jutglar M.; Ponsá S.; Sellarès N.; Vendrell-Puigmitjà L.; Llenas L.; Ordeix M.; Proia L. Driving Factors of geosmin Appearance in a Mediterranean River Basin: The Ter River Case. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 741750 10.3389/fmicb.2021.741750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi L.; Sola C. Role of geosmin, a Typical Inland Water Odour, in Guiding Glass Eel Anguilla anguilla (L.) Migration. Ethology 1993, 95, 177–185. 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1993.tb00468.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon O. S.; Song H. S.; Park T. H.; Jang J. Conducting Nanomaterial Sensor Using Natural Receptors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (1), 36–93. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son M.; Cho D. G.; Lim J. H.; Park J.; Hong S.; Ko H. J.; Park T. H. Real-time monitoring of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol, representative odor compounds in water pollution using bioelectronic nose with human-like performance. Biosens Bioelectron 2015, 74, 199–206. 10.1016/j.bios.2015.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.