Abstract

Unprofessional behaviours (UBs) between healthcare staff are widespread and have negative impacts on patient safety, staff well-being and organisational efficiency. However, knowledge of how to address UBs is lacking. Our recent realist review analysed 148 sources including 42 reports of interventions drawing on different behaviour change strategies and found that interventions insufficiently explain their rationale for using particular strategies. We also explored the drivers of UBs and how these may interact. In our analysis, we elucidated both common mechanisms underlying both how drivers increase UB and how strategies address UB, enabling the mapping of strategies against drivers they address. For example, social norm-setting strategies work by fostering a more professional social norm, which can help tackle the driver 'reduced social cohesion'. Our novel programme theory, presented here, provides an increased understanding of what strategies might be effective to adddress specific drivers of UB. This can inform logic model design for those seeking to develop interventions addressing UB in healthcare settings.

Keywords: Professional Role, Safety culture, Patient safety, Quality improvement, Implementation science

Introduction

Unprofessional behaviours (UBs) between staff can include, but are not limited to, microaggressions, incivility, bullying and harassment.1 These behaviours have negative impacts on staff well-being, patient safety, organisational reputation and organisational costs2 and are unfortunately prevalent in healthcare systems worldwide.1 3 4 We recently published two papers from our recent realist review. One reported a programme theory (PT) explaining five types of key driver of UBs in acute care settings and how these work5. The other reported a PT drawing on 42 reports of interventions using 13 types of behaviour change strategies to reduce UB.6 To improve the effectiveness of interventions to reduce UB, we found that it is essential to directly target drivers of UB with strategies that address them.6 However, which strategies best address particular drivers of UB have not yet been articulated.7 8 This report sets out which behaviour change strategies address specific drivers of UB based on common underlying mechanisms of action.

Methods

Realist reviews seek to understand why an intervention may work (or not), for whom, in which contexts and why, through the generation of PTs using retroductive logic.9 These are generally depicted as context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations.10 These mechanisms, in realist terms, can be defined as ‘changes in recipient reasoning that occur in response to resources introduced by an intervention’.11

In line with RAMESES guidelines,9 10 our first step was to build initial PTs by analysing 38 reports from organisations such as National Health Service (NHS) England, the King’s Fund and NHS Employers using NVivo V.12 for data organisation.12 13 We then tested and refined these theories against 110 additional studies (to December 2022) identified with systematic searches of Embase, CINAHL and MEDLINE databases, and grey literature repositories. Article selection involved screening records for inclusion, rigour and relevance. Full methodology including inclusion/exclusion criteria is reported elsewhere.5 6 12

This resulted in theories to explain how and why 13 types of behaviour change techniques or ‘strategies’ work to reduce or mitigate UB and what drives UB and how—reported separately elsewhere.5 6 Uniquely, this short report combines these two aspects of our analysis, whereby we mapped mechanisms underpinning drivers of UB5 against strategies which address these drivers6 to develop this overall explanatory PT.

Results

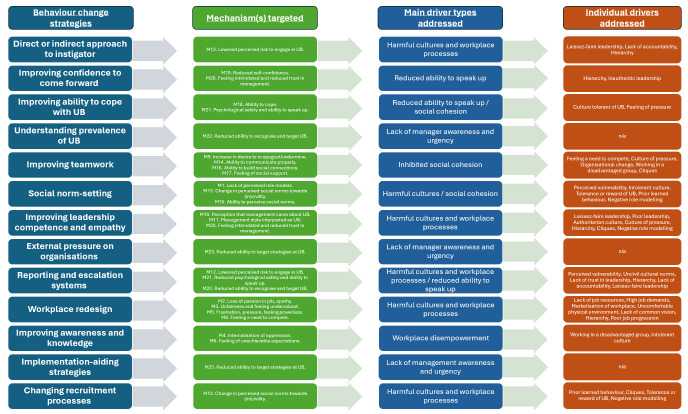

Our review encompassed 42 reports of interventions to address UB,14–55 29 of which have been evaluated through various study designs. Figure 1 presents a PT diagram depicting which behaviour strategies target various mechanisms underlying drivers of UB, which driver categories are impacted by these strategies, and which individual drivers within these categories are targeted. This PT includes five major drivers of UB: (1) workplace disempowerment; (2) harmful workplace processes and cultures; (3) inhibited social cohesion; (4) a reduced ability to speak up and (5) lack of manager awareness and urgency.5 In table 1, we provide more details of these behaviour change strategies and how they target specific drivers of UB as well as how frequently each strategy type was used by the 29 included evaluated interventions. Online supplemental file 1 presents an alternative version of figure 1 designed specifically to map onto our PT published elsewhere and provides a further detailed version of table 1.5

Figure 1.

Diagram to depict which different behaviour change strategies target particular drivers of unprofessional behaviour (UB).

Table 1.

Matching the 13 types of strategy (and individual strategies within these) against types of drivers of UB

| Primary driver addressed | Behaviour change strategies |

| Single incidents of UB (individual-level/does not address drivers) | Direct or indirect approach to instigator (target, bystander or managers)—used in 14 out of 29 evaluated interventions |

| Informal resolution | |

| Disciplinary action | |

| Peer messengers | |

| Mediation | |

| Speaking up | |

| Workplace disempowerment and staff ability to speak up | Improving confidence to come forward (target, bystander)—used in 22 out of 29 evaluated interventions |

| Assertiveness training | |

| Role playing | |

| Cognitive rehearsal | |

| Keeping records | |

| Improving awareness and knowledge (all)—used in 12 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Education, awareness and general group discussions | |

| Improving social cohesion | Improving ability to cope with UB (target, bystander)—used in 0 out of 29 evaluated interventions |

| Seeking help externally | |

| Journalling | |

| Moving targets | |

| Individual coping strategies | |

| Reflection | |

| Improving teamwork (all)—used in 16 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Teambuilding exercises | |

| Conflict management training | |

| Communication training | |

| Journal club/group writing | |

| Problem-based learning | |

| Staff networks | |

| Addressing harmful cultures and workplace processes | Social norm-setting (all)—used in 16 out of 29 evaluated interventions |

| Championing | |

| Code of conduct | |

| Role modelling | |

| Environmental modification | |

| Allyship | |

| Improving leadership competence and empathy (managers/leaders)—used in 2 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Leadership training | |

| Reverse mentoring | |

| Reporting and escalation systems (all)—used in 7 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Reporting system | |

| Changing recruitment processes (all)—used in 0 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Changing recruitment criteria | |

| Dismissal | |

| Workplace redesign (all)—used in 1 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Democratisation of workplace | |

| Improving manager awareness and urgency to address UB | External accreditation or pressure on organisations (managers/leaders)—used in 2 out of 29 evaluated interventions |

| Seeking hospital Magnet status | |

| Regulator action | |

| Laws and regulations | |

| Understanding prevalence of UB (managers/leaders)—used in 3 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Survey | |

| Multisource feedback | |

| Implementation-aiding strategies (managers/leaders)—used in 11 out of 29 evaluated interventions | |

| Action planning or goal setting | |

| Building a repertoire of strategies |

UB, unprofessional behaviour.

bmjoq-2024-002830supp001.pdf (293.8KB, pdf)

Figure 1 highlights that many drivers of workplace disempowerment and harmful workplace processes are only addressed by workplace redesign strategies. Such workplace redesign strategies seek to facilitate staff autonomy, control and ownership of work; however, workplace redesign must occur at an organisational level and has only been used once in an evaluated intervention.16 Our work also shows that the most frequently used (often individual-focused) strategies, such as improving awareness and knowledge of UB, address few actual drivers of UB and therefore may not be as effective as other strategies.

Discussion and conclusions

Existing interventions have made little use of logic models and behavioural science principles in their design, meaning that the rationale behind choice of behaviour change strategies has been poorly articulated and not evidence-based.6 Our PT, presented in figure 1, is a starting point to inform logic model design for those seeking to design evidence-based interventions that address particular drivers of UB.56 To improve reporting, future research should align and operationalise these strategies against existing Behaviour Change Technique (BCT) frameworks.57

Our PT has also highlighted that many systemic drivers remain under-addressed. Predominantly, existing interventions have focused on individual or team strategies to address UB with less focus on more systemic, potentially difficult-to-implement strategies such as redesigning the workplace to reduce frustrations and increase staff ownership over work.6

We have produced a free evidence-based guide for addressing UB in healthcare, available at https://workforceresearchsurrey.health/projects-resources/addressing-unprofessional-behaviours-between-healthcare-staff/.58

Footnotes

@J_Aunger

Contributors: JAA drafted this article with input from all authors. This article was based on analysis performed by JAA, JM and RA, with input from all authors. RA, RM, JIW, AJ, JMW, MP and JM attained funding to support this research. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project was supported by the NIHR HS&DR programme with grant number NIHR131606. JA was also supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Midlands Patient Safety Research Collaboration (PSRC) with grant number NIHR204294.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Westbrook J, Sunderland N, Li L, et al. The prevalence and impact of unprofessional behaviour among hospital workers: a survey in seven Australian hospitals. Med J Aust 2021;214:31–7. 10.5694/mja2.50849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Westbrook J, Sunderland N, Atkinson V, et al. Endemic unprofessional behaviour in health care: the mandate for a change in approach. Med J Aust 2018;209:380–1. 10.5694/mja17.01261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Layne DM, Nemeth LS, Mueller M, et al. Negative behaviours in health care: prevalence and strategies. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:154–60. 10.1111/jonm.12660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carter M, Thompson N, Crampton P, et al. Workplace bullying in the UK NHS: a questionnaire and interview study on prevalence, impact and barriers to reporting. BMJ Open 2013;3. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aunger JA, Maben J, Abrams R, et al. Drivers of unprofessional behaviour between staff in acute care hospitals: a realist review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023;23:1326. 10.1186/s12913-023-10291-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maben J, Aunger JA, Abrams R, et al. Interventions to address unprofessional behaviours between staff in acute care: what works for whom and why? A realist review. BMC Med 2023;21:403. 10.1186/s12916-023-03102-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Illing J, Carter M, Thompson NJ, et al. Evidence synthesis on the occurrence, causes, management of bullying and harassing behaviours to inform decision making in the NHS. 2013;44:54–168. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maben J, Aunger JA, Abrams R, et al. Why do acute healthcare staff behave unprofessionally towards each other and how can these behaviours be reduced? A realist review. BMJ Open 2022;12:e061771. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11:1–14. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pawson R, Matutes E, Brito-Babapulle V, et al. Sezary cell leukaemia: a distinct T cell disorder or a variant form of T Prolymphocytic leukaemia? Leukemia 1997;11:1009–13. 10.1038/sj.leu.2400710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong G, Westhorp G, Pawson R, et al. Realist synthesis: RAMESES training materials. In: RAMESES Proj. 2013: 55. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maben J, Aunger JA, Abrams R, et al. Why do acute healthcare staff engage in unprofessional behaviours towards each other and how can these behaviours be reduced? A realist review protocol. BMJ Open 2022;12:e061771. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aunger JA, Millar R, Greenhalgh J, et al. Building an initial realist theory of partnering across national health service providers. JICA 2020;29:111–25. 10.1108/JICA-05-2020-0026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter MP, Day A, et al. Building empowering work environments that foster civility and organizational trust: testing an intervention. Nurs Res 2012;61:316–25. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318265a58d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osatuke K, Moore SC, Ward C, et al. Civility, respect, engagement in the workforce (CREW). J Appl Behav Sci 2009;45:384–410. 10.1177/0021886309335067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stevens S. Nursing workforce retention: challenging a bullying culture. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:189–93. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang J, Kim JI, Yun S. Effects of a cognitive rehearsal program on interpersonal relationships, workplace bullying, symptom experience, and turnover intention among nurses: a randomized controlled trial. J Korean Acad Nurs 2017;47:689–99. 10.4040/jkan.2017.47.5.689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Warrner J, Sommers K, Zappa M, et al. Decreasing work place incivility. Nurs Manage 2016;47:22–30. 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000475622.91398.c3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dahlby MA, Herrick LM. Evaluating an educational intervention on lateral violence. J Contin Educ Nurs 2014;45:344–50. 10.3928/00220124-20140724-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Speck RM, Foster JJ, Mulhern VA, et al. Development of a professionalism committee approach to address unprofessional medical staff behavior at an academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2014;40:161–7. 10.1016/s1553-7250(14)40021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Asi Karakaş S, Okanli A e. The effect of assertiveness training on the mobbing that nurses experience. Workplace Health Saf 2015;63:446–51. 10.1177/2165079915591708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chipps EM, McRury M. The development of an educational intervention to address workplace bullying: a pilot study. J Nurses Staff Dev 2012;28:94–8. 10.1097/NND.0b013e31825514bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kang J, Jeong YJ. Effects of a smartphone application for cognitive rehearsal intervention on workplace bullying and turnover intention among nurses. Int J Nurs Pract 2019;25:e12786. 10.1111/ijn.12786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parker KM, Harrington A, Smith CM, et al. Creating a nurse-led culture to minimize horizontal violence in the acute care setting: a multi-interventional approach. J Nurses Prof Dev 2016;32:56–63. 10.1097/NND.0000000000000224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dimarino TJ. Eliminating lateral violence in the ambulatory setting: one center’s strategies. AORN J 2011;93:583–8. 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Griffith M, Clery MJ, Humbert B, et al. Exploring action items to address resident mistreatment through an educational workshop. West J Emerg Med 2019;21:42–6. 10.5811/westjem.2019.9.44253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O’Connell KM, Garbark RL, Nader KC. Cognitive rehearsal training to prevent lateral violence in a military medical facility. J Perianesth Nurs 2019;34:645–53. 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lasater K, Mood L, Buchwach D, et al. Reducing incivility in the workplace: results of a three-part educational intervention. J Contin Educ Nurs 2015;46:15–24. 10.3928/00220124-20141224-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Armstrong NE. A quality improvement project measuring the effect of an evidence-based civility training program on nursing workplace incivility in a rural hospital using quantitative methods. OJRNHC 2017;17:100–37. 10.14574/ojrnhc.v17i1.438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dixon-Woods M, Campbell A, Martin G, et al. Improving employee voice about transgressive or disruptive behavior: a case study. Acad Med 2019;94:579–85. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baldwin CA, Hanrahan K, Edmonds SW, et al. Implementation of peer messengers to deliver feedback: an observational study to promote professionalism in nursing. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2023;49:14–25. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2022.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stagg SJ, Sheridan DJ, Jones RA, et al. Workplace bullying: the effectiveness of a workplace program. Aust Nurs Midwifery J 2017;24:34–6. 10.1177/216507991306100803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Banerjee D, Nassikas NJ, Singh P, et al. Feasibility of an antiracism curriculum in an academic pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine division. ATS Sch 2022;3:433–48. 10.34197/ats-scholar.2022-0015OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stagg SJ, Sheridan D, Jones RA, et al. Evaluation of a workplace bullying cognitive rehearsal program in a hospital setting. J Contin Educ Nurs 2011;42:395–401. 10.3928/00220124-20110823-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nicotera AM, Mahon MM, Wright KB. Communication that builds teams: assessing a nursing conflict intervention. Nurs Adm Q 2014;38:248–60. 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nikstaitis T, Simko LC. Incivility among intensive care nurses: the effects of an educational intervention. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2014;33:293–301. 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Webb LE, Dmochowski RR, Moore IN, et al. Using coworker observations to promote accountability for disrespectful and unsafe behaviors by physicians and advanced practice professionals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2016;42:149–64. 10.1016/s1553-7250(16)42019-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thorsness R, Sayers B. Systems approach to resolving conduct issues among staff members. AORN J 1995;61:197–202, . 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)63859-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Keeffe DA, Brennan SR, Doherty EM. Resident training for successful professional interactions. J Surg Educ 2022;79:107–11. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Westbrook JI, Urwin R, McMullan R, et al. Changes in the prevalence of unprofessional behaviours by co-workers following a professional accountability culture change program across five Australian hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barrett A, Piatek C, Korber S, et al. Lessons learned from a lateral violence and team-building intervention. Nurs Adm Q 2009;33:342–51. 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3181b9de0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kousha S, Shahrami A, Forouzanfar MM, et al. Effectiveness of educational intervention and cognitive rehearsal on perceived incivility among emergency nurses: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs 2022;21:153. 10.1186/s12912-022-00930-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Churruca K, Pavithra A, McMullan R, et al. Creating a culture of safety and respect through professional accountability: case study of the ethos program across eight Australian hospitals. Aust Health Rev 2022;46:319–24. 10.1071/AH21308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hickson GB, Pichert JW, Webb LE, et al. A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Acad Med 2007;82:1040–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815761ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Griffin M. Teaching cognitive rehearsal as a shield for lateral violence: an intervention for newly licensed nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs 2004;35:257–63. 10.3928/0022-0124-20041101-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leiter MP, Laschinger HKS, Day A, et al. The impact of civility interventions on employee social behavior, distress, and attitudes. J Appl Psychol 2011;96:1258–74. 10.1037/a0024442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kile D, Eaton M, deValpine M, et al. The effectiveness of education and cognitive rehearsal in managing nurse-to-nurse incivility: a pilot study. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:543–52. 10.1111/jonm.12709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saxton R. Communication skills training to address disruptive physician behavior. AORN J 2012;95:602–11. 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McKenzie L, Shaw L, Jordan JE, et al. Factors influencing the implementation of a hospitalwide intervention to promote professionalism and build a safety culture: a qualitative study. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2019;45:694–705. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jenkins S, Woith W, Kerber C, et al. Why can’t we all just get along? A civility Journal club intervention. Nurse Educ 2011;36:140–1. 10.1097/NNE.0b013e31821fd9b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. DeMarco RF, Roberts SJ, Chandler GE. The use of a writing group to enhance voice and connection among staff nurses. J Nurs Staff Dev 2005;21:85–90. 10.1097/00124645-200505000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Embree JL, Bruner DA, White A. Raising the level of awareness of nurse-to-nurse lateral violence in a critical access hospital. Nurs Res Pract 2013;2013:207306. 10.1155/2013/207306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ceravolo DJ, Schwartz DG, Foltz-Ramos KM, et al. Strengthening communication to overcome lateral violence. J Nurs Manag 2012;20:599–606. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hawkins N, Jeong SY-S, Smith T, et al. Creating respectful workplaces for nurses in regional acute care settings: a quasi-experimental design. Nurs Open 2023;10:78–89. 10.1002/nop2.1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Clark CM, Ahten SM, Macy R. Using problem-based learning scenarios to prepare nursing students to address incivility. Clin Simul Nurs 2013;9:e75–83. 10.1016/j.ecns.2011.10.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Funnell SC, Rogers PJ. Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Marques MM, Wright AJ, Corker E, et al. The behaviour change technique ontology: transforming the behaviour change technique Taxonomy V1 [version 1; peer review: 4 approved]. Wellcome Open Res 2023;8:308. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.19363.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maben J, Aunger J, Abrams R, et al. Addressing unprofessional behaviours between healthcare staff: a guide. 2023:1–38. Available: https://workforceresearchsurrey.health/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2024-002830supp001.pdf (293.8KB, pdf)