Abstract

During diabetes progression, β-cell dysfunction due to loss of potassium channels sensitive to ATP, known as KATP channels, occurs, contributing to hyperglycemia. The aim of this study was to investigate if KATP channel expression or activity in the nervous system was altered in a high-fat diet (HFD)–fed mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Expression of two KATP channel subunits, Kcnj11 (Kir6.2) and Abcc8 (SUR1), were decreased in the peripheral and central nervous system of mice fed HFD, which was significantly correlated with mechanical paw-withdrawal thresholds. HFD mice had decreased antinociception to systemic morphine compared with control diet (CON) mice, which was expected because KATP channels are downstream targets of opioid receptors. Mechanical hypersensitivity in HFD mice was exacerbated after systemic treatment with glyburide or nateglinide, KATP channel antagonists clinically used to control blood glucose levels. Upregulation of SUR1 and Kir6.2, through an adenovirus delivered intrathecally, increased morphine antinociception in HFD mice. These data present a potential link between KATP channel function and neuropathy during early stages of diabetes. There is a need for increased knowledge of how diabetes affects structural and molecular changes in the nervous system, including ion channels, to lead to the progression of chronic pain and sensory issues.

Article Highlights

Peripheral and central nervous system expression of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel subunits are decreased in mice fed a high-fat diet compared with control diet mice.

Morphine antinociception is attenuated in mice fed a high-fat diet; this is exacerbated if treated daily with glyburide or nateglinide.

Restoration of KATP channel subunit (Abcc8, Kcnj11) expression by an adenovirus vector increases morphine antinociception.

Loss of potassium channel activity may account for diabetes-induced neuropathy, including in prediabetic stages.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was once considered a disease of elderly people, but the prevalence is increasing among younger people, with increased complications such as neuropathy in adolescents and young adults (1,2). Neuropathy is common in people with prediabetes and diabetes, which affect up to 50% of patients with diabetes in their lifetime (3). Reversing neuropathy before full-blown progression to diabetes and determining the pathogenesis of neuropathy and finding treatment in a prediabetic state would be highly beneficial to thousands of patients.

Several compounds, including sulfonylureas (e.g., glyburide) and meglitinides (e.g., nateglinide), have been clinically available to promote release of insulin and aid achieving normoglycemia. These drugs block ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels to depolarize β-cells in the pancreas. Sulfonylurea drug prescribing has decreased over time, but these drugs are still used in up to 20% of patients in the United States (4). Several subtypes of KATP channels exist because they contain four potassium channel subunits, Kir6.1 or Kir6.2, and four sulfonylurea regulatory subunits, either SUR1 or SUR2, which can exist as multiple combinations depending on tissue type. Kir6.2-SUR1 is the major subunit combination of KATP channels in the pancreas and a major target of sulfonylureas and meglitinides. Kir6.2-SUR1 is also heavily expressed in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons, and mice with loss of Kir6.2 have altered somatosensory thresholds and lose unmyelinated fibers in the peripheral nervous system (5). KATP subunit expression has been found to be altered in several models of chronic pain in rodents, in cellular and rodent in vivo diabetes models (6–8), and in human DRG of individuals with painful diabetic neuropathy (7). Dysregulation of KATP channel function or expression in the nervous system appears to be concurrent with abnormal sensory processing and sensory neuron function.

Treatment options for diabetic neuropathy are limited, and although opioid drugs are not first-line choices, they are still used as treatment options (9). Upon activation by an agonist, opioid receptors couple to G-proteins and interact with various intracellular effector systems, including opening KATP channels (10). Multiple signaling pathways targeting ion channels may work to promote hyperexcitability of sensory neurons during neuropathy (11), and medications blocking KATP channels (e.g., sulfonylureas/meglitinides) would be predicted to promote hyperalgesia and/or decrease efficacy of analgesics, particularly morphine. Coupled with data suggesting that KATP channels are involved in DRG hypersensitivity during hyperglycemia, this would suggest that treatment of diabetes with sulfonylureas/metaglinides with chronic opioid use would be problematic for patients with diabetic neuropathy (12). Because several antidiabetic drugs target KATP channels and opioid medications are still used to treat diabetic neuropathy in the clinic, an important drug-drug interaction could be occurring for thousands of patients.

Our goal was to test the hypothesis that KATP channel expression would be decreased in the spinal cord and DRG of prediabetic mice, based on previous studies showing a loss of KATP channel activity in the brain of diabetic rodents (13,14). We also tested the hypothesis that systemic administration of glyburide or nateglinide would inhibit morphine-induced antinociception in these animals compared with age- and sex-matched controls. A high-fat-diet-fed mouse model of diet-induced obesity was chosen to most closely emulate 1) physiological and metabolic conditions found in humans and 2) the influence of glucose, ATP, and other metabolites affecting KATP channel activity and/or expression during diabetes (15–18). This model also produces increased fasting insulin, glucose intolerance, increased cholesterol, and altered sensory nerve deficits seen in patients with T2DM (19).

Research Design and Methods

Animals

The University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures. Male and female C57BL/6 mice (4 weeks of age; weight, 13–25 g; Charles River), housed in a standard 12-h day/night environment, were placed in randomly assigned groups (n = 110 mice; Fig. 1). Groups received either a control diet (CON) or a high-fat, high-carbohydrate diet (HFD; Open Source Diets catalog nos. 12328 and 12330, respectively; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) starting at week 5, for 17 weeks. Food and water were available ad libitum and monitored weekly. The drug and viral treatments were blinded to the experimenter during all behavioral testing.

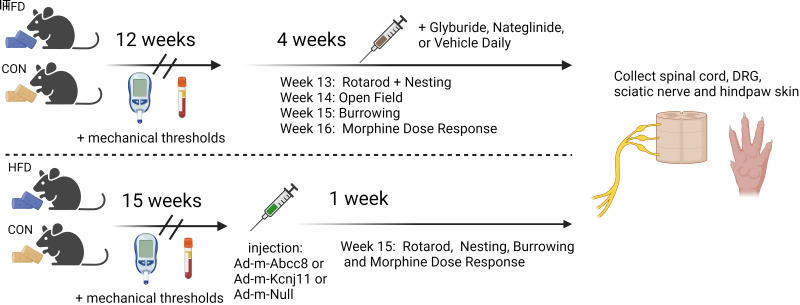

Figure 1.

Overall study design. IT, intrathecal.

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Testing

Animals were fasted for 6 hours prior to lateral tail vein blood collection. The mice were given d-glucose (100 µL, 0.5 g/mL in sterile saline, intraperitoneally), and blood glucose readings were obtained at 10-, 30-, and 60-min after dextrose administration (α Trak2; Zoetis Inc., Kalamazoo, MI).

Blood Assays

Blood was collected from the superficial temporal vein for metabolic assays using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Metabolic Hormone Bead Panel (catalog no. MMHMAG-44k-07; MilliporeSigma). Blood samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C and serum was stored at −80°C per manufacturer’s guidelines for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), C-peptide 2, and insulin.

Mechanical Paw Withdrawal Thresholds

Mice were placed into acrylic animal enclosure cubicles on top of a mesh floor, and mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds were measured using electronic von Frey testing equipment (Almemo 2450; Ahlborn, IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA). A probe was pressed into the plantar surface of the hind paw, and the force required to evoke a nocifensive response was measured. Five measurements from both the right and left hind paw were obtained for baseline measurements with at least a 30-s interstimulus period between each measurement.

Thermal Paw Withdrawal Latency

Mice were placed into clear acrylic cubicles on top of a glass platform heated to 30°C. The Hargreaves method was used to determine thermal withdrawal latency by recording the amount of time a heat-radiant beam of light, focused on the plantar surface of the hind paws, was required to cause a nocifensive response (Model 400; IITC). The maximum time of exposure was 20 s. Five measurements from both the right and left hind paws were obtained with at least 2 min between successive tests.

Rotarod Testing

Motor coordination was assessed with the Rotamex-5 automated rotarod system (Model 0254-2002L; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Starting speed (4 rpm) was increased in 1-rpm increments at 30-s intervals until animals fell off the rod or reached a top speed of 14 rpm (300 s). Two tests per animal were conducted and averaged.

Open-Field Testing

Animals were placed in an open-field arena (40 cm × 40 cm) and activity was recorded with a digital camcorder for offline analysis (HDR-CX405; Sony). Animals were recorded for 15 min of baseline activity, followed by injection of morphine (15 mg/kg subcutaneously [sc]) and recorded for another 30 min. The distance traveled was calculated using Ethowatcher computational software for data analysis (https://ethowatcher.paginas.ufsc.br/).

Nesting Behavior

Animals were placed in individual cages overnight (∼14 h) with an ∼5-cm cotton Nestlet square (Ancare, Bellmore, NY). In the morning, nest building was assessed by applying the nest complexity scoring matrix (20). Nesting scores were based on a 0–5 scale with 0.5 increments.

Burrowing

For 2 h, mice were placed into individual empty cages containing a burrowing tube filled with 500 g of pea gravel. Tubes were constructed from polyvinylchloride conduit tubing sections with a 20 cm × 6 cm interior. The open ends of tubes were raised approximately 4 cm with bolts. Any gravel remaining in the tube was weighed to assess gravel displacement.

Drug Administration

Six groups of animals received daily doses in the morning of either glyburide (50 mg/kg), nateglinide (50 mg/kg), or vehicle (20% DMSO, 0.5% Tween in sterile saline, 100 μL) during the last 5 weeks on either diet (weeks 12–16). Sixteen weeks after starting either a CON or HFD, cumulative antinociception dose-response curves were obtained for morphine (2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg in saline, sc). In four additional groups of mice, pregabalin (12.5, 25, 50 mg/kg in saline, sc) or gabapentin (25, 50,100 mg/kg in saline, sc) was given 30 min after baseline mechanical thresholds were obtained.

qPCR

RNA was extracted from harvested tissues using RNeasy Mini Kit (catalog no. 74104, QIAGEN, Inc., Germantown, MD) with DNase I digestion. A maximum of 30 mg of tissue was macerated in 1 mL of TriReagent using a glass tissue grinder before titration with a 22-gauge blunt needle. Homogenate was incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min with 0.1 mL of bromo 3-chloropropane before centrifugation. Spinal cord RNA was eluted over two washes of 35 µL of RNase free water, whereas DRG RNA was eluted with a single 35-µL wash. RNA was quantified using either Nanodrop (ND-1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and/or a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription was performed using the Omniscript RT kit (catalog no. 205111, QIAGEN, Inc.) and random nonamers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA).

qPCR was performed using a Roche LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master mix (Roche). Temperature-dependent dissociation of the DNA product was examined using a melting curve at the end of each reaction. The primers used in this study were: Abcc8 forward: 5′-GATGGGGTGACAGAATCCCG -3′, reverse: 5′-GGCGTGGTCGTAGAACTTGA-3′; Abcc9 forward: 5′-TGTAGGCCAAGTGGGTTGTG-3′, reverse: 5′-TCTGCTTCGGGTTGCTTCAA-3′; Kcnj11 forward: 5′-CGCCCACAAGAACATTCGAG-3′, reverse: 5′-GCAGAGTGTGTGGCCATTTG-3′; Kcnj8 forward: 5′-GGCACCATGGAGAAGAGTGG-3′, reverse: 5′-CAAAACCGTGATGGCCAGAG-3′; Gapdh forward: 5′-TCAGGAGAGTGTTTCCTCGTC-3′, reverse: 5′-CCGTTGAATTTGCCGTGAGT-3′; and 18s forward: 5′-CGCCGCTAGAGGTGAAATTCTT-3′, reverse: 5′-CAGTCGGCATCGTTTATGGTC-3′.

C-Fiber Compound Action Potentials

Sciatic nerves were dissected from the hind limbs of mice and recordings were performed the day of harvesting in superficial interstitial fluid. Electrical stimulation was delivered by a pulse stimulator (0.3 Hz, 100-μs duration at 100–10,000 μA; model 2100, A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA). Evoked compound action potentials were recorded with electrodes placed 10 mm from the stimulating electrodes. Dapsys software was used for data capture and analysis (Dapsys.net). The stimulus with the lowest voltage producing a detectable response in the nerve was determined as the threshold stimulus. The stimulus voltage where the amplitude of the response no longer increased was determined to be the peak amplitude. The conduction velocity was calculated by dividing the latency period by the stimulus-to-recording electrode distance.

Adenoviral Upregulation of SUR1 and Kir6.2 Subunits

After being fed either a CON or HFD for 15 weeks, six additional groups of mice were inoculated with adenovirus (Ad) carrying constructs for either SUR1 (Ad-m-ABCC8, ADV-251792; 3–5 × 1010 PFU; Vector Biolabs, Malvern, PA), Kir6.2 (Ad-m-KCNJ11, ADV-262651, 3–5 × 1010 PFU, Vector Biolabs), or a control vector (Ad-CMV-Null, ∼2 × 1010 PFU). For intrathecal injections, a 10-μL inoculum was administered to conscious mice as described previously (21).

Immunohistochemistry and Microscopy

Posterior hind paw skin was submerged in Zamboni Fixative overnight, moved to 1× PBS, and held at 4°C. Paw skins were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, sectioned (10 μmol/L; Leica CM3050), and mounted on electrostatically charged slides. Slides from three mice per treatment group were incubated at RT in 50 mmol/L glycine for 45 min and then washed twice in 1× PBST (0.2% Triton X-100). Tissues were then blocked for 1 h in PBST + 10% horse serum (catalog no. 26050-088; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) plus 1% BSA (catalog no. BP1600–100; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then incubated with the primary antibody (ab108986; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.) at 1:500 dilution in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. Tissue was then washed three times in PBST and incubated with the secondary antibody (ab150075; Abcam) at a 1:1,000 dilution in blocking solution for 4 h at RT. Tissues were washed for 5 min in PBST three times and mounted using DAPI Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Slides were imaged using a ×20 objective on a laser scanning confocal microscope (catalog no. LSM710; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Fluorescence Quantification

Confocal microscopy files were analyzed using ImageJ/Fiji. Across all images, ∼300 μmol/L long × ∼50 μmol/L wide regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn to include the epidermal-dermal junction. The ROIs were designed to capture ascending nerve fibers crossing into the epidermis. Initial measurements were taken at this time, including area, minimum and maximum gray value, integrated density, and mean gray value. The corrected total fluorescence was calculated using the following equation: (integrated density − [area of ROI – mean fluorescence of 3 background samples]). A total of 10 images were included for analysis per animal.

Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SE or as median ± 95% CI. For normally distributed data, statistical comparisons were made by unpaired t tests, linear regression, or one-way or two-way ANOVA, with between-group differences using Tukey or Dunnett post hoc tests. Statistical analyses were performed using either GraphPad 10 or SPSS (IBM, version 27). Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Data and Resource Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No applicable resources were generated during this study.

Results

Development of T2DM Phenotype in Mice

Male and female mice were placed on either a CON or HFD for 16 weeks. Mice on the HFD gained weight faster than their CON counterparts starting at 5–7 weeks and were glucose intolerant at 9 weeks (Fig. 2A–F). Progression of obesity and loss of glucose tolerance was comparable across males and females. Nine weeks after diet induction, circulating levels of insulin, C-peptide, and GIP were elevated in male mice, but only insulin and C-peptide were elevated in female mice (Fig. 2G–L). Intraepidermal nerve fiber intensity significantly decreased in HFD mice compared with CON mice (Supplementary Fig. 1). Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds determined a progression of hypersensitivity over time (Fig. 3A) in HFD mice, which fully developed in 10 weeks in male mice (Fig. 3B) and 8 weeks in female mice (Fig. 3C). Mechanical thresholds at 10 weeks were compared with corresponding fasting blood glucose levels taken within the same week. No significant correlation between these two factors was found in either sex (Fig. 3D and B). Paw withdrawal latency to radiant heat or cold also was similar between HFD and CON mice, with no sex differences detected (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C).

Figure 2.

Male and female HFD mice had increased body weight, impaired glucose tolerance, and enhanced levels of serum peptides consistent with physiology similar to T2DM. A–C: Body weights of HFD and CON mice were significantly different in male (B) and female (C) mice at 5 and 7 weeks, respectively, after diet induction (repeated measures [RM] ANOVA, week × diet: males, F(9,702) = 57.2, P < 0.0001; females, F(9,513) = 7.5, P < 0.001; Bonferroni post hoc; n = 29–40/group). D–F: Glucose tolerance was inhibited in HFD mice at 9 weeks after diet induction in male (E) and female (F) mice (RM ANOVA, week × diet: males, F(3,234) = 4.3, P = 0.006; females, F(3,174) = 2.836, P = 0.04; Bonferroni post hoc; n = 30–40/group). Bar charts reflect area under the curve (AUC). Significance shown using unpaired t tests. Serum levels of insulin (G–I) (unpaired t test: male, P = 0.021; female, P = 0.015); C-peptide (J–L) (unpaired t test: male, P < 0.001; female, P = 0.0002); and GIP (M–O) (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) were significantly higher in HFD mice than CON mice. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds decreased over time but were not correlated with blood glucose levels in HFD mice. A: Male and female mice paw withdrawal thresholds remain consistent in CON mice but significantly declined in HFD mice (repeated measures [RM] ANOVA, F(1,88) = 4.982, P = 0.028). A significant effect of diet (F(1,86) = 80.9, P < 0.0001) and sex (F(1,86) = 10.02, P = 0.002) was identified. B: Male HFD mice had significantly decreased paw withdrawal thresholds over time compared with CON mice (RM ANOVA: F(4,232) = 2.51, P = 0.043; n = 30/group). C: Similar decreases in paw withdrawal thresholds were found over time in female HFD mice (RM ANOVA: F(4,112) = 2.75, P = 0.032; n = 15/group). Male (D) or female (E) mice fed an HFD or a CON for up to 10 weeks did not have a significant correlation between mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds and fasting blood glucose levels. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

KATP Channel Subunit Expression in the Peripheral and Central Nervous Systems

The expression of each KATP channel subunit in the lumbar DRG and spinal cords of HFD and CON mice was measured via qPCR. KATP channels exist as octomers, and gene expression for each subunit was measured and compared across diet and animal sex. Expression of the gene for SUR1, Abcc8, was significantly decreased in the DRG of male HFD mice compared with CON mice, and expression of the gene for Kir6.2, Kcnj11, was decreased in both males and females (Fig. 4A–C). Kcnj11 expression was decreased in the spinal cords of male and female HFD mice compared with CON mice (Fig. 4D–F). The expression of Abcc9 and Kcnj8 was unaltered in both male and female mice. Collectively, the data indicate that, in both sexes, HFD mice have similar differences in KATP channel subunit mRNA expression compared with CON mice.

Figure 4.

DRG and spinal cord levels of KATP channel subunit mRNA were decreased in male and female mice fed an HFD for 16 weeks compared with CON mice. A: mRNA levels of the protein products Kir6.2 (Kcnj11) and SUR1 (Abcc8) were significantly decreased in DRG of HFD mice compared with CON mice (unpaired t test: Kcnj11, P = 0.036; Abcc8, P = 0.048). A significant sex effect was found for Abcc8 (F(1,36) = 3.69, P < 0.001); therefore, the data for male and female mice were further analyzed separately. B: Kcnj11 and Abcc8 were decreased in male HFD mice (unpaired t test: Kcnj11, P = 0.045; Abcc8, P = 0.029). C: DRG of female HFD mice had significantly decreased mRNA levels of Kcnj11 (unpaired t test, P = 0.0013) compared with the average of mice on the CON. D: mRNA levels of Abcc8 were significantly decreased in spinal cord of HFD mice compared with CON mice (Abcc8: P = 0.0, unpaired t test). A significant sex effect was found for Kcnj11, Abcc8, and Abcc9 (Kcnj11: F(1,35) = 16.79, P < 0.001; Abcc8: F(1,35) = 95.49, P < 0.001; Abcc9: F(1,35) = 11.44, P = 0.002); therefore, the data were further analyzed with male and female data separated. Spinal cord mRNA levels of Kcnj11 (E) (P = 0.0053) were significantly downregulated in male mice, as were levels of Kcnj11 and Abcc8 (F) in female mice (unpaired t test, Kcnj11: P = 0.0018; Abcc8: P < 0.0001). mRNA levels of SUR2 (Abcc9) or the Kir6.1 gene product (Kcnj8) were not significantly altered for either males or females in the DRG or spinal cord. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Because male and female mice also have comparable time courses of diabetic progression (Fig. 2) and mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 3), it was decided to combine the data sets moving forward. A significant positive correlation was found in the DRG of HFD mice with Kcnj11 and Abcc8 expression and mechanical thresholds (Fig. 5A and B), but not with Abcc9, (Fig. 5C). Expression of Abcc8 and Abcc9 was also positively correlated in the spinal cords of HFD mice (Fig. 5D–G), but not expression of Kcnj11 or Kcnj8. KATP channel subunit expression in CON mice was not significantly correlated in either DRG or spinal cord.

Figure 5.

Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds were positively correlated with Kcnj11 and Abcc8 mRNA expression levels in the DRG (A–C) and spinal cord (D–G) of HFD mice. Mice fed an HFD for 16 weeks had a significant correlation between mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds and number of mRNA copies of Kcnj11 (A) (HFD: Pearson correlation coefficient r(13) = 0.701, P = 0.0036) and Abcc8 (B) (HFD: Pearson correlation coefficient r(13) = 0.675, P = 0.006) in the DRG. There were no significant correlations found between mRNA copies of Abcc9 and mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds in the DRG (C) nor were there significant correlations between Kcnj11 (D) or Kcnj8 (E) mRNA levels in the spinal cord. mRNA levels of Abcc8 (F) (HFD: Pearson correlation coefficient: r(13) = 0.579, P = 0.024) and Abcc9 (G) (HFD: Pearson correlation coefficient r(13) = 0.764, P = 0.0009) were positively correlated with mechanical thresholds in the spinal cord of HFD mice.

Glyburide or Nateglinide Treatment and Behavioral Testing

Male and female HFD and CON mice were separated into one of three treatment groups 12 weeks after the start of their respective diets: glyburide, nateglinide, or a vehicle-treated group. We predicted that treatment with a drug designed to improve insulin release by blocking KATP channels would affect hypersensitivity and alter morphine analgesia. Mechanical thresholds were significantly decreased in HFD mice compared with CON mice treated with vehicle, regardless of systemic treatment (Fig. 6A). A cumulative dose-response curve indicates that treatment with glyburide or nateglinide, in either CON or HFD mice, significantly decreased the antinociceptive effect of morphine (Fig. 6B and C). Nonreflexive behaviors were also tested, including nesting behavior, which was not significantly altered between diet and/or treatment groups (Fig. 6D). HFD mice had significantly decreased burrowing behavior compared with CON mice (Fig. 6E). A similar diet effect was also seen in HFD mice compared with CON mice assessed by time spent on a rotarod apparatus, although no specific post hoc comparisons indicated significance between drug treatments (Fig. 6F). These data suggest that HFD mice may have greater motor deficits than CON mice, which was corroborated by results of an open-field test in which HFD mice traveled less than CON mice (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Although a significant decrease in mechanical paw withdrawals was seen between diet or drug treatment after morphine administration (Fig. 6B), mechanical thresholds after pregabalin or gabapentin administration remained similar (Fig. 2D and E), and differences in hyperlocomotion activity after morphine administration were not seen (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

Figure 6.

Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds were significantly decreased in HFD mice. A: Mice fed an HFD for longer than 3 months had decreased mechanical thresholds compared with CON mice (F(1,57) = 18.723, P < 0.001). B: Dose-response curves for CON and HFD mice indicate that glyburide (Gly) and nateglinide (Nat) treatment decreased the antinociception of morphine, especially in HFD mice. C: Treatment with glyburide or nateglinide, especially in combination with an HFD decreased mechanical thresholds compared with vehicle treatment or CON. The area under the curve (AUC) of mechanical threshold data obtained in A and B indicates a significant effect of diet (F(1,57) = 43.5, P < 0.001) and treatment (F(2,57) = 39.38, P < 0.0001), as well as a significant interaction (diet × treatment, F(2,57) = 5.53, P = 0.006). D: HFD and CON mice both exhibited complex nest building behavior and constructed nests regardless of systemic glycemic drug treatment. E: HFD mice displaced less gravel in a burrowing tube compared with CON mice (F(1,53) = 5.088, P = 0.028). F: The motor coordination, assessed by rotarod test, was significantly decreased in HFD mice compared with CON mice (F(1,53) = 7.384, P = 0.009). Daily injections of Gly or Nat did not significantly affect nesting, burrowing, or motor coordination compared with vehicle (Veh)-treated animals. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Upregulation of SUR1 and Kir6.2 and Morphine Dose Response

Because a loss of KATP channel subunits was correlated with lower mechanical thresholds in HFD mice, a separate cohort of mice was inoculated with an Ad in the intrathecal space to upregulate Abcc8 or Kcnj11 in the lumbar spinal cord and DRGs. Abcc8 expression was significantly elevated in Ad-m-Abcc8–inoculated mice and Kcnj11 was similarly elevated in Ad-m-Kcnj11–inoculated mice compared with controls (Fig. 7A). Mechanical thresholds were higher in CON compared with HFD mice in a cumulative morphine dose-response curve (Fig. 7B) and a significant effect of virus treatment, including Ad-m-Abcc8–and Ad-m-Kcnj11–upregulated mice compared with null virus-treated mice also was seen (Fig. 7C). Expression levels of Abcc8 were significantly correlated with mechanical thresholds in both HFD and CON mice (Fig. 7D), whereas Kcnj11 mRNA expression was not significantly correlated (Fig. 7E). Separate behavioral assays indicated that nesting behaviors were unaltered by either diet or viral treatment (Fig. 7F), but a significant diet effect was found for burrowing behaviors (Fig. 7G). The latency to falling off of a rotating rod was significantly decreased in HFD compared with CON mice but was not mitigated by viral treatment (Fig. 7H).

Figure 7.

Upregulation of Abcc8 and Kcnj11 increase morphine antinociception in mice fed an HFD. A: Upregulation of Abcc8 and Kcnj11 mRNA in the spinal cord was detected after intrathecal administration of Ad-m-Abcc8, Ad-m-Kcnj11 compared with a control vector (Ad-m-Null; two-way ANOVA, F(5,48) = 17.38, P < 0.0001, Dunnett post hoc test). B: Paw withdrawal thresholds are higher in Ad-m-Abcc8 and Ad-m-Kcnj11 mice compared with null controls (repeated measures ANOVA, F(2,24) = 5.861, P = 0.017; Abcc8, P < 0.001; Kcnj11, P = 0.024). C: Area under the curve (AUC) data from A and B. CON mice injected with Ad-m-Abcc8 have higher paw withdrawal thresholds to increasing doses to morphine compared with control vector mice (ANOVA, F(5,24) = 7.86, P < 0.001). A significant effect of diet (ANOVA, F(1,24) = 6.09, P = 0.021) and virus (F(2,24) = 15.74, P < 0.0001), including significance of Abcc8 and Kcnj11 compared with null virus-treated mice, were also seen. Positive correlations exist in mice between the AUC of paw withdrawals and Abcc8 mRNA expression in the spinal cord (D) (Pearson correlation coefficient = r(30) = 0.4461, P = 0.0135), but not with Kcnj11 mRNA expression (E) (Pearson correlation coefficient = r(30) = 0.00407, P = 0.831). F: HFD or CON mice both exhibited complex nest building behavior and constructed nests regardless of virus treatment. Data are presented as medians with 95% CI. G: Mice fed an HFD displaced less gravel in a burrowing tube compared with CON mice (F(1,24) = 57.1, P < 0.001). HFD-null and HFD-Abcc8 mice have less burrowing compared with CON-null mice (F(5,24) = 15.72, P < 0.001). H: The motor coordination, assessed by rotarod test, was significantly decreased in null, Abcc8, and Kcnj11 mice fed an HFD (ANOVA, F(5,24) = 5.741, P = 0.001). A significance effect of diet was also observed on the rotarod (F(1,24) = 26.26, P < 0.001). Data in A–E, G, and H are displayed as means with SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. Adenovirus (Ad) designed to upregulate either Abcc8, Kcnj11, or a scrambled sequence (null) was delivered to the intrathecal space of adult mice (10 μL; Vector Biolabs) 1 week before behavioral testing.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that expression of KATP channel subunits in the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system is correlated with mechanical sensitivity in mice fed a HFD for 4 months. Male and female HFD mice had elevated weight, impaired glucose tolerance, and mechanical hypersensitivity after ∼9 weeks compared with CON mice. Downregulation of Kcnj11 and Abcc8 in the spinal cord and DRG also was comparable in male and female HFD mice related to CON mice. Daily administration of KATP channel antagonists further decreased morphine sensitivity in HFD compared with CON mice. The pharmacological inhibition of KATP channels did not appear to affect locomotor behaviors or antinociception from nonopioid analgesics, including pregabalin. An attempt to reverse this loss of Abcc8 and Kcnj11 expression using a viral vector strategy improved morphine antinociception.

Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia are considered primary drivers of damage to nerve fibers, yet diabetic neuropathy is not always tightly associated with epidermal nerve loss (22) or hyperglycemia (23). In this study, we did not find a significant correlation between mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds and fasting blood glucose in either male or female mice. mRNA levels for KATP channel subunits, including Abcc8 and Kcnj11, were significantly decreased in HFD mice in the DRG and spinal cord, and positively correlated with mechanical thresholds. In vitro, hyperglycemia increases the resting membrane potential of rat DRGs, which is mostly reversed by adding diazoxide, a SUR1-selective agonist (24). Several metabolic and cellular changes during diabetes progression could contribute to loss of KATP channel function and expression. GIP potentiates glucose-induced insulin secretion from the pancreas in a KATP channel–dependent manner (25), and incretin‐bound receptors such as GIPR increase intracellular cAMP levels, activating protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac). Inhibition of adenylyl cyclase or Epac attenuates heat hypersensitivity in db/db mice (26), and increased levels of PKA and/or Epac inhibit KATP channel activity in various cellular models (27,28). T2DM is also characterized by disproportionate production of intermediary metabolites, including methylglyoxal, that cause cellular damage and increase hypersensitivity (29), and inhibit KATP channel expression (30).

At the end of the study, these animals were near the mature adult (human equivalency, ∼30 years old) phase; we used young mice that remained on their respective diets for 16 weeks. Although T2DM affects all age ranges, neuropathy is most prevalent in older cohorts with poor glucose stability, and aging is an important factor to consider when discussing changes in nervous system function. β-Cells in the pancreas lose KATP channel conductance in aged mice, which is consistent with human aging that is accompanied by declining glucose tolerance (31). The function of KATP channel subunits expressed in small vessels involved in brain stem circulation are also decreased in 2-year-old compared with 4–6-month-old rats (32), and transcriptomic data indicate that KATP channel expression is altered in aged mouse brains (33). It is possible the loss of KATP channel function in older people with diabetes may be even further pronounced than described in this study.

Sulfonylureas inhibit antinociception in several animal models, particularly after opioid administration (34). KATP channel agonists reduce hypersensitivity in various rodent models, indicating that activation of KATP channels in peripheral nerves has either antinociceptive and/or analgesic effects (34–37). Interestingly, the opening probability of KATP channels typically increases in DRGs after diazoxide application, but this effect is greatly attenuated in rats after spinal nerve injury. The antinociceptive effect of morphine was significantly decreased in HFD mice compared with CON mice, and this was further exacerbated in mice treated with glyburide or nateglinide. Neither drug affected nerve conduction or other behavioral measures, including morphine-induced hyperlocomotion (38). The antinociceptive effect of pregabalin was similar across CON and HFD mice. Interestingly, gabapentin did not have a significant effect on mechanical paw-withdrawal thresholds, indicating that gabapentin may have limited analgesic efficacy in some pain models (39).

A viral strategy to upregulate Abcc8 and Kcnj11 in the spinal cord of CON and HFD mice was used to determine if restoration of KATP channel expression could improve morphine antinociception. Abcc8 upregulation improved the mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds, particularly in HFD mice, whereas Kcnj11 was less effective. In vitro studies show that SUR1 is more sensitive to changes in ADP/ATP levels than SUR2 when coupled to Kir6.2 (40), indicating that the sulfonylurea units are key players in metabolic coupling to resting membrane potentials. SUR1 and SUR2 are the molecular targets for several diabetes medications, rather than the Kir subunits (41), and are targets for ATP/ADP, a key parameter to regulating cellular metabolism. Changes in metabolites, energy expenditure, and mitochondrial function during diabetes may affect SUR subunits more than Kir subunit functioning, explaining why upregulation of Abcc8 was more beneficial to restore sensory function in HFD animals than was Kcnj11.

The results of these studies suggest drugs targeting KATP channels could also alter sensory perception and lower efficacy of opioid medications to reduce pain. We are unaware of any large-scale, cross-sectional analyses of data to characterize trends in the use of sulfonylurea/metaglinide drug types among patients taking opioids versus nonopioid medication for chronic pain. Early studies have suggested an associated risk between sulfonylurea use and adverse cardiovascular events, but the results are mixed (42,43). These inconsistencies could be due to differences in duration and severity of diabetes, choice of reference group, previous history of cardiovascular events, and length of follow-up. Given the issues previously raised investigating cardiovascular adverse events and sulfonylureas, it could be useful to continue these efforts with neuropathy and opioid use in patients with diabetes, with careful controls for any potential confounding of data mentioned above. Several diabetic medications exist beyond sulfonylureas, including metformin (44) and glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonists. How metformin or GLP-1 agonists directly or indirectly influence ion channel excitability, including KATP channels, during diabetes is up for debate (28,45). Further studies are also needed to verify whether the long-term use of antidiabetic drugs increases the susceptibility of patients to neuropathy and/or loss of analgesic efficacy due to downstream targeting of ion channels.

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.25864330.

Article Information

Funding. This work was supported through a University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Faculty Development Grant to A.H.K. and M.L.G. and the National Institutes of Health (R01DA05187 to A.H.K.).

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. M.L.G. and A.H.K. conceived of and designed the research. C.F., K.J., M.M., A.S., and J.L.J. performed experiments. C.F., K.J., and A.H.K. analyzed the data and interpreted results of experiments. A.H.K. drafted the manuscript and produced the final version of the manuscript, which was approved by all authors. All authors edited and revised the manuscript. A.H.K. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. A non–peer-reviewed version of this article was submitted to the BioRxiv preprint server (https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.06.556526) on 6 September 2023. Some parts of the data reported here were published previously: Klein AH, Johnson K, Fisher C, Moore M, Sadrati A, Janecek JL, Graham ML. KATP channels function in the peripheral and central nervous systems in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. J Pain 2022;23: 16–17 (5, Suppl.).

Funding Statement

This work was supported through a University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Faculty Development Grant to A.H.K. and M.L.G. and the National Institutes of Health (R01DA05187 to A.H.K.).

References

- 1. Jaiswal M, Divers J, Dabelea D, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy in youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1226–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akinci G, Savelieff MG, Gallagher G, Callaghan BC, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy in children and youth: new and emerging risk factors. Pediatr Diabetes 2021;22:132–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hicks CW, Selvin E. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy and lower extremity disease in diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2019;19:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shin JI, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Fang M, Grams ME, Selvin E. Trends in use of sulfonylurea types among US adults with diabetes: NHANES 1999-2020. J Gen Intern Med 2023;38:2009–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakai-Shimoda H, Himeno T, Okawa T, et al. Kir6.2-deficient mice develop somatosensory dysfunction and axonal loss in the peripheral nerves. iScience 2021;25:103609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moritz W, Leech CA, Ferrer J, Habener JF. Regulated expression of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel subunits in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology 2001;142:129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hall BE, Macdonald E, Cassidy M, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of human sensory neurons in painful diabetic neuropathy reveals inflammation and neuronal loss. Sci Rep 2022;12:4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camunas-Soler J, Dai XQ, Hang Y, et al. Patch-Seq links single-cell transcriptomes to human islet dysfunction in diabetes. Cell Metab 2020;31:1017–1031.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJ, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017;40:136–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cunha TM, Roman-Campos D, Lotufo CM, et al. Morphine peripheral analgesia depends on activation of the PI3Kγ/AKT/nNOS/NO/KATP signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:4442–4447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Todorovic SM. Is diabetic nerve pain caused by dysregulated ion channels in sensory neurons? Diabetes 2015;64:3987–3989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khalilzadeh O, Anvari M, Khalilzadeh A, Sahebgharani M, Zarrindast MR. Involvement of amlodipine, diazoxide, and glibenclamide in development of morphine tolerance in mice. Int J Neurosci 2008;118:503–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li D, Huang B, Liu J, Li L, Li X. Decreased brain K(ATP) channel contributes to exacerbating ischemic brain injury and the failure of neuroprotection by sevoflurane post-conditioning in diabetic rats. PLoS One 2013;8:e73334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gyte A, Pritchard LE, Jones HB, Brennand JC, White A. Reduced expression of the KATP channel subunit, Kir6.2, is associated with decreased expression of neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein in the hypothalami of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Neuroendocrinol 2007;19:941–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Purrello F, Vetri M, Vinci C, Gatta C, Buscema M, Vigneri R. Chronic exposure to high glucose and impairment of K(+)-channel function in perifused rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes 1990;39:397–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tokuyama Y, Fan Z, Furuta H, et al. Rat inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir6.2: cloning electrophysiological characterization, and decreased expression in pancreatic islets of male Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;220:532–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doty M, Yun S, Wang Y, et al. Integrative multiomic analyses of dorsal root ganglia in diabetic neuropathic pain using proteomics, phospho-proteomics, and metabolomics. Sci Rep 2022;12:17012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fancher IS, Dick GM, Hollander JM. Diabetes mellitus reduces the function and expression of ATP-dependent K+ channels in cardiac mitochondria. Life Sci 2013;92:664–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Brien PD, Hinder LM, Rumora AE, et al. Juvenile murine models of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes develop neuropathy. Dis Model Mech 2018;11:dmm037374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deacon R. Assessing burrowing, nest construction, and hoarding in mice. J Vis Exp 2012. (59):e2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vulchanova L, Schuster DJ, Belur LR, et al. Differential adeno-associated virus mediated gene transfer to sensory neurons following intrathecal delivery by direct lumbar puncture. Mol Pain 2010;6:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Themistocleous AC, Ramirez JD, Shillo PR, et al. The Pain in Neuropathy Study (PiNS): a cross-sectional observational study determining the somatosensory phenotype of painful and painless diabetic neuropathy. Pain 2016;157:1132–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Obrosova I. Hyperglycemia-initiated mechanisms in diabetic neuropathy. In Diabetic Neuropathy. Clinical Diabetes. Veves A, Malik R, Eds. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Campos Lima T, Santos DO, Lemes JBP, Chiovato LM, Lotufo CMDC. Hyperglycemia induces mechanical hyperalgesia and depolarization of the resting membrane potential of primary nociceptive neurons: role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Neurol Sci 2019;401:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miki T, Minami K, Shinozaki H, et al. Distinct effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 on insulin secretion and gut motility. Diabetes 2005;54:1056–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Griggs RB, Santos DF, Laird DE, et al. Methylglyoxal and a spinal TRPA1-AC1-Epac cascade facilitate pain in the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Neurobiol Dis 2019;127:76–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seino Y, Fukushima M, Yabe D. GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: similarities and differences. J Diabetes Investig 2010;1:8–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Light PE, Manning Fox JE, Riedel MJ, Wheeler MB. Glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channels via a protein kinase A- and ADP-dependent mechanism. Mol Endocrinol 2002;16:2135–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shamsaldeen YA, Mackenzie LS, Lione LA, Benham CD. Methylglyoxal, a metabolite increased in diabetes is associated with insulin resistance, vascular dysfunction and neuropathies. Curr Drug Metab 2016;17:359–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang Y, Li S, Konduru AS, et al. Prolonged exposure to methylglyoxal causes disruption of vascular KATP channel by mRNA instability. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012;303:C1045–C1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gregg T, Poudel C, Schmidt BA, et al. Pancreatic β-cells from mice offset age-associated mitochondrial deficiency with reduced KATP channel activity. Diabetes 2016;65:2700–2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toyoda K, Fujii K, Takata Y, et al. Age-related changes in response of brain stem vessels to opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Stroke 1997;28:171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ximerakis M, Lipnick SL, Innes BT, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of the aging mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 2019;22:1696–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Afify EA, Khedr MM, Omar AG, Nasser SA. The involvement of K(ATP) channels in morphine-induced antinociception and hepatic oxidative stress in acute and inflammatory pain in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2013;27:623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Du X, Wang C, Zhang H. Activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels antagonize nociceptive behavior and hyperexcitability of DRG neurons from rats. Mol Pain 2011;7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niu K, Saloman JL, Zhang Y, Ro JY. Sex differences in the contribution of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in trigeminal ganglia under an acute muscle pain condition. Neuroscience 2011;180:344–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Enders JD, et al. ATP-gated potassium channels contribute to ketogenic diet-mediated analgesia in mice. 24 May 2023 [preprint] bioRxiv, 2023.05.22.541799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. Eid SA, Feldman EL. Advances in diet-induced rodent models of metabolically acquired peripheral neuropathy. Dis Model Mech 2021;14:dmm049337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Waldfogel JM, Nesbit SA, Dy SM, et al. Pharmacotherapy for diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain and quality of life: a systematic review. Neurology 2017;88:1958–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vedovato N, Rorsman O, Hennis K, Ashcroft FM, Proks P. Role of the C-terminus of SUR in the differential regulation of β-cell and cardiac KATP channels by MgADP and metabolism. J Physiol 2018;596:6205–6217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dörschner H, Brekardin E, Uhde I, Schwanstecher C, Schwanstecher M. Stoichiometry of sulfonylurea-induced ATP-sensitive potassium channel closure. Mol Pharmacol 1999;55:1060–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wexler DJ. Sulfonylureas and cardiovascular safety: the final verdict? JAMA 2019;322:1147–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roumie CL, Min JY, D’Agostino McGowan L, et al. Comparative safety of sulfonylurea and metformin monotherapy on the risk of heart failure: a cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e005379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Engler C, Leo M, Pfeifer B, et al. Long-term trends in the prescription of antidiabetic drugs: real-world evidence from the Diabetes Registry Tyrol 2012–2018. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020;8:e001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wei J, Wei Y, Huang M, Wang P, Jia S. Is metformin a possible treatment for diabetic neuropathy? J Diabetes 2022;14:658–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]