Abstract

One hallmark of murine leukemia virus (MuLV) leukemogenesis in mice is the appearance of env gene recombinants known as mink cell focus-inducing (MCF) viruses. The site(s) of MCF recombinant generation in the animal during Moloney MuLV (M-MuLV) infection is unknown, and the exact roles of MCF viruses in disease induction remain unclear. Previous comparative studies between M-MuLV and an enhancer variant, Mo+PyF101 MuLV, suggested that MCF generation or early propagation might take place in the bone marrow under conditions of efficient leukemogenesis. Moreover, M-MuLV induces disease efficiently following both intraperitoneal (i.p.) and subcutaneous (s.c.) inoculation but leukemogenicity by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV is efficient following i.p. inoculation but attenuated upon s.c. inoculation. Time course studies of MCF recombinant appearance in the bone marrow, spleen, and thymus of wild-type and Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.- and s.c.-inoculated mice were carried out by performing focal immunofluorescence assays. Both the route of inoculation and the presence of the PyF101 enhancer sequences affected the patterns of MCF generation or early propagation. The bone marrow was a likely site of MCF recombinant generation and/or early propagation following i.p. inoculation of M-MuLV. On the other hand, when the same virus was inoculated s.c., the primary site of MCF generation appeared to be the thymus. Also, when Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV was inoculated i.p., MCF generation appeared to occur primarily in the thymus. The time course studies indicated that MCF recombinants are not involved in preleukemic changes such as splenic hyperplasia. On the other hand, MCFs were detected in tumors from Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice even though they were largely undetectable at preleukemic times. These results support a role for MCF recombinants late in disease induction.

Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) is a simple nonacute retrovirus that induces T-lymphoblastic lymphoma in NIH Swiss mice. A frequent event during the development of MuLV-induced leukemias is the formation of mink cell focus-inducing (MCF) recombinant viruses (18). MCF viruses arise by recombination in vivo between the env gene of an infecting MuLV and endogenous polytropic or modified polytropic MuLV proviruses present in virtually all mice (33). MCF envelope protein binds to cells via a different receptor from that used by the original ecotropic MuLVs (25). Several lines of evidence suggest that MCF recombinants play important roles in MuLV-induced leukemogenesis in mice, but the exact role(s) remains unclear (15). For example, MCF recombinants may carry out late functions, including long terminal repeat (LTR) activation of proto-oncogenes (19), activation of cytokine receptors (21), and additional rounds of superinfection of cells already infected with ecotropic MuLV (20).

MCF recombinants may also be important early during leukemogenesis by M-MuLV, as suggested by comparative studies of M-MuLV and an enhancer variant of M-MuLV, Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV (15). Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV contains enhancer sequences from the F101 strain of polyomavirus inserted downstream from the M-MuLV enhancers (23). Leukemogenicity of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV is dependent on the route of inoculation: Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) is poorly leukemogenic, while Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) results in disease kinetics comparable to those induced by wild-type M-MuLV (1, 6, 10). In contrast, M-MuLV induces leukemia efficiently with the same kinetics regardless of the route of inoculation (1). Experiments with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV indicated that early high-level infection of the thymus (the ultimate site of tumor formation) apparently was not required for efficient disease induction by M-MuLV. Instead, efficient disease induction was correlated with efficient early infection of the bone marrow and the appearance of MCF recombinants (1, 2). Since early bone marrow infection was well correlated with the development of MCF recombinants, this suggested that infection of bone marrow might be required for recombinant MCF virus formation. The association also suggested that MCF recombinant formation and/or initial propagation may take place in the bone marrow. In addition, studies with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV suggested that MCF recombinants might be involved in the establishment of preleukemic changes such as generalized hematopoietic hyperplasia in the spleen, defects in bone marrow hematopoiesis, and accelerated thymic atrophy (11, 12, 22).

The goals of this study were to characterize the initial sites of MCF recombinant appearance in mice following M-MuLV and Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV infection. Such a survey might suggest the sites of MCF recombinant formation and propagation; it might also address the relevance of MCF recombinant generation and propagation to leukemogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and viruses.

NIH Swiss mice (Hsd:NIHSThe mice) were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, Ind.) and maintained as an outbred colony. Viral stocks were clarified cell culture supernatants derived from NIH 3T3 fibroblasts productively infected with either wild-type M-MuLV (22) or the Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV enhancer variant (23); portions of viral stocks were individually frozen at −70°C and were thawed and used only once (17).

Virus and inoculation of NIH Swiss mice.

Virus infectivity titer determinations were performed by both the UV-XC syncytial assay (26) and the focal immunofluorescence assay (FIA) (31) on NIH 3T3 cells. Neonatal NIH Swiss mice were inoculated either intraperitoneally (i.p.) or subcutaneously (s.c.) with 0.20 ml of virus stock (1.5 × 105 XC PFU, 3 × 105 FIU) within 48 h of birth.

MAbs.

The monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) used in this study were MAb 514 and MAb 538. MAb 514 is specifically reactive with the SU proteins of polytropic (and modified polytropic) MuLVs, including the two antigenic subclasses of M-MCF (7, 13). MAb 538 is specifically reactive with the SU protein of M-MuLV. MAb 514 and MAb 538 hybridoma cells were cultured in RPMI (28) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cultures were grown to 106 cells/ml, and Ab-containing supernatants were collected 5 to 7 days thereafter and used for infectious-center assays (see below).

MAb 538 was derived from the spleen of a (B10.A × A)F1 mouse immunized by intravenous inoculation with tissue culture supernatant containing the M-MuLV–spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) complex. At 75 days after infection, this mouse was given an intravenous booster immunization with 3 × 107 spleen cells from the enlarged leukemic spleen of a (BALB/c × A)F1 mouse previously infected with the M-MuLV–SFFV complex. At 16 days later, the spleen cells of the immunized mouse were fused to NS1 cells to generate hybridomas as described previously (7). Positive hybridoma wells were identified by indirect membrane immunofluorescence on live trypsinized NIH 3T3 cells chronically infected with M-MuLV. Ethanol-fixed cells gave negative results. Hybridoma cells were cloned by limiting dilution, and supernatant fluid was characterized for Ab specificity and immunoglobulin (Ig) class. MAb 538 was an IgM antibody with reactivity for only M-MuLV, and molecular clones 8.2 and 1387 were both positive. Over 30 other MuLVs were negative with this MAb, including ecotropic Friend, Rauscher and AKV MuLVs and numerous MuLVs in the amphotropic, xenotropic, and polytropic host range groups. Although MAb 538 was unable to immunoprecipitate viral proteins efficiently or react in Western blots, it was specific for viral envelope protein based on its reactivity with the FMF chimeric MuLV, which has only the SphI-ClaI env gene fragment derived from M-MuLV (29).

Assays for infectious virus.

The presence of infectious virus in hematopoietic organs was determined by infectious-center (IC) assays on NIH 3T3 cells by the focal-immunofluorescence assay (FIA) (31). Infected mice and uninfected control mice were sacrificed at the times indicated, and single-cell suspensions were prepared from their bone marrow, spleens, and thymuses. Bone marrow cells were obtained by using a 1-ml syringe fitted with a 25G5/8 or 23G1 needle to flush each femur and tibia with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Spleen and thymus tissue was removed and rinsed gently with sterile PBS. Cells were recovered by passing tissue through a 94-mm 150-mesh screen (Bellco). The cells were washed with PBS, and their viability and concentration were determined by trypan blue exclusion. Tenfold serial dilutions of cell suspensions were cocultivated for 24 h with NIH 3T3 cells (7 × 104 to 8 × 104 cells per 60-mm dish seeded 1 day previously) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% calf serum (CS) and 2 μg of Polybrene per ml. Following cocultivation, the nonadherent hematopoietic cells were aspirated, the NIH 3T3 monolayers were washed, the growth medium was replaced with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium–10% CS, and the cells were allowed to grow to confluency (4 to 5 days). The cultures were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 0.25 ml of undiluted MAb 538- or MAb 514-containing hybridoma supernatant, washed twice with PBS–2% CS, and then treated for 30 min and room temperature with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG, IgA, and IgM [ICN Pharmaceuticals]) diluted 1:200 in PBS–2% CS. The cultures were then washed twice, and infectious centers were visualized by fluorescence microscopy and counted.

DNA isolation and Southern blot hybridization.

DNA was extracted from single-cell suspensions or cell lines by a modification of standard methods (8) and suspended in 10 mM Tris–0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8). Restriction endonuclease digestion of high-molecular-weight DNA, gel electrophoresis, transfer, and hybridization were performed as previously described (2, 4, 6). DNA fragments used as radioactive probes for Southern blot analyses included the 199-bp PyF101 enhancer-containing PvuII-4 fragment inserted at the XbaI site of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV as previously described (23); the 620-bp BamHI-EcoRI fragment from the 5′ env region of the M-MCF recombinant that is reactive with the M-MCF recombinant and endogenous polytropic and modified polytropic viruses (6), and the 1.1-kb BamHI-ClaI fragment from the 3′ env region of M-MuLV that is reactive with both ecotropic M-MuLV and polytropic M-MCF recombinants (4). Random primer [32P]dATP- (or [32P]dCTP)-labeled probes were prepared by using the DECAprime II DNA labeling kit (Ambion, Austin, Tex.) as specified by the manufacturer. When indicated, the probes were stripped from the membranes by incubation at 95 to 100°C in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 40 to 60 min with gentle agitation and the membranes were rehybridized as described above.

RESULTS

MCF recombinant appearance and propagation in M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice.

The site(s) of MCF recombinant generation during M-MuLV infection is unknown. Our previous studies suggested that the bone marrow might be involved in MCF virus formation or propagation (2, 6), but other candidate hematopoietic compartments included the spleen and thymus. High levels of ecotropic virus infection are established in all three tissue compartments at early times postinfection (<14 days) (1), and MCF recombinants have been detected in the spleen and thymus of M-MuLV-infected mice as early as 3–4 weeks, although the bone marrow was not examined (14, 20). Our initial strategy to identify the site(s) of MCF recombinant generation was to search different tissues for the earliest appearance of MCF recombinants.

Immediately after MCF recombinant formation and initial propagation, it is likely that only a small fraction of cells will express MCF virus. However, at later times, MCF recombinants will have amplified in vivo by several orders of magnitude. We evaluated the sensitivity, range of detection, and reproducibility of several different methods of MCF recombinant detection including Southern blot hybridization (32), PCR amplification (24, 27, 28), and IC assays (FIAs) (31). FIA proved to be the most sensitive and reliable technique, allowing measurements of MCF virus ICs over a range of 6 to 7 orders of magnitude (0.00002 to 100% of cells infected). Another advantage of the FIA was that it measured infectious MCF recombinants.

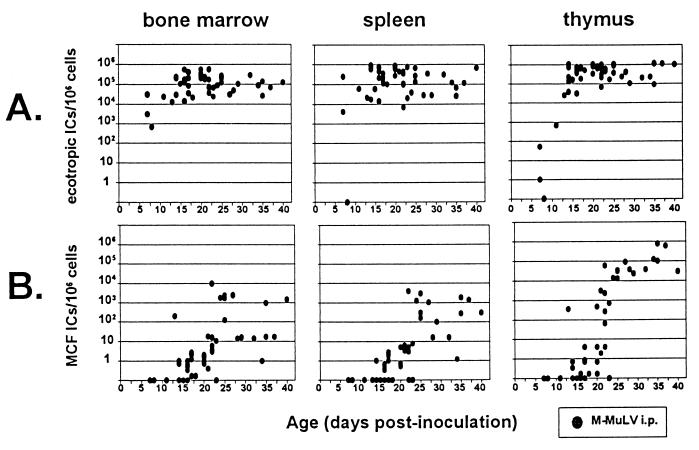

We infected neonatal mice i.p. with M-MuLV and quantified the appearance of MCF virus-infected cells in the bone marrow, spleens, and thymuses of infected mice during the preleukemic period by measuring MAb 514-reactive ICs by FIA of cells from these hematopoietic compartments. MAb 514 is specifically reactive with the SU proteins of polytropic (and modified polytropic) MuLVs, including the two antigenic subclasses of recombinant MCFs that appear during M-MuLV infection (7, 13). We also measured the appearance of ecotropic M-MuLV-infected cells in the same tissues by FIA with MAb 538. MAb 538 is specifically reactive with the ecotropic SU protein of M-MuLV. As shown in Fig. 1A, mice inoculated i.p. with M-MuLV showed a rapid appearance of ecotropic ICs in the bone marrow, spleen, and thymus. The appearance of M-MuLV ecotropic ICs in the thymus was slightly delayed compared to that in bone marrow and spleen: maximum numbers of ecotropic ICs were detected in the bone marrow and spleen by 7 to 10 days, in contrast to 13 to 15 days for the thymus. At later times, the numbers of ecotropic ICs in the thymus were somewhat higher (approximately 5- to 10-fold) than in the bone marrow and spleen. These results were consistent with previous reports on M-MuLV-infected mice (1, 14).

FIG. 1.

Numbers of ecotropic and MCF recombinant ICs in preleukemic mice inoculated i.p. with M-MuLV. Neonatal mice were inoculated i.p. with 1.5 × 105 XC PFU (3 × 105 FIU) of M-MuLV; bone marrow cells, splenocytes, and thymocytes were plated onto NIH 3T3 fibroblasts; and the ICs were quantified by FIA as described in Materials and Methods. The results are plotted as the number of MAb 538 (ecotropic) or MAb 514 (MCF recombinant)-reactive ICs per 106 cells as a function of age. MAb 538-reactive (ecotropic) IC numbers (A) and MAb 514-reactive (MCF recombinant) IC numbers (B) from bone marrow cells, splenocytes, and thymocytes are shown. All datum points represent the IC number from an individual mouse. Datum points resting on the x axis indicate animals with an undetectable IC number (<0.2 IC per 106 cells plated).

Figure 1B displays the appearance of MCF virus ICs in M-MuLV i.p.-infected mice. MCF virus ICs were detected beginning 13 to 22 days postinoculation. At very early times, the fractions of cells scoring positive for polytropic ICs in each tissue were generally very low (0.2 to 10 per million). By 24 days postinfection, MCF virus ICs were detected in all three hematopoietic compartments in all animals. Thus, they had been generated and disseminated by that time. If MCF virus generation took place in only one tissue, propagation to the other two compartments occurred rapidly.

In mice infected i.p. with M-MuLV, the numbers of MCF virus ICs reached plateau levels by 4 to 5 weeks, most probably reflecting a rapid amplification of MCF virus infection between 3 and 5 weeks. It was noteworthy that the maximal numbers of polytropic ICs were substantially larger (10- to 100-fold) in the thymus than in the bone marrow and spleen. Thus, MCF recombinant amplification was most efficient in the thymus.

Sites of the earliest appearance of MCF recombinants following i.p. inoculation.

The patterns of ecotropic and polytropic ICs shown in Fig. 1 did not readily suggest a site for MCF recombinant generation, since high-level ecotropic infection was established in all tissues before MCF recombinant ICs were detected in any of them. Furthermore, MCF recombinants were amplified in the bone marrow, spleen, and thymus with similar rapid kinetics. In most animals tested at 1 to 4 weeks, MCF recombinants were either absent from all three hematopoietic compartments or present in all of them. However, in a subset of animals, MCF recombinants were detected in one or two but not all three compartments. Thus, MCF recombinants apparently had not spread completely in these animals. The MCF recombinant IC profiles in these animals might suggest where MCF recombinant were generated.

Table 1 summarizes the polytropic IC data from the animals that were “discordant” for detectable MCF recombinants, i.e., those that showed MCF recombinant ICs in at least one but not all tissues. MCF recombinant ICs were detected in the bone marrow in 14 of 15 discordant animals. In three animals, only the bone marrow sample showed detectable ICs. In contrast, only 4 of 15 discordant animals showed ICs in the spleen, although in 1 animal they were detected in only the spleen. An intermediate fraction of discordant animals (8 of 15) showed detectable ICs in the thymus; however, none of these 8 animals showed ICs only in the thymus. These findings were consistent with the possibility that the bone marrow was the primary site of MCF recombinant generation.

TABLE 1.

MCF recombinant IC counts from M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice discordant for MCF virus infectiona

| Mouse no. | Time (days) postinoculation | No. of MCF recombinant ICs/106 cells platedb in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | Spleen | Thymusf | ||

| 1 | 13 | 198 | bdlc | 347 |

| 2 | 14 | 0.7 | bdl | 0.7 |

| 3 | 14 | 0.7 | bdl | 0.3 |

| 4 | 14 | 0.7 | bdl | 0.3 |

| 5 | 14 | 1 | 1 | bdl |

| 6 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.7 | bdl |

| 7e | 16 | bdl | 0.5 | bdl |

| 8 | 16 | 0.3 | 0.3 | bdl |

| 9d | 16 | 1 | bdl | bdl |

| 10d | 16 | 0.5 | bdl | bdl |

| 11 | 16 | 0.7 | bdl | 0.2 |

| 12d | 17 | 0.2 | bdl | bdl |

| 13 | 18 | 0.2 | bdl | 0.2 |

| 14 | 22 | 3 | bdl | 65 |

| 15 | 22 | 4 | bdl | 260 |

| Fraction with detectable MCF ICs | 14/15 | 4/15 | 8/15 | |

Of 40 mice inoculated i.p. with M-MuLV that were examined at times between 7 and 27 days postinoculation, 15 had detectable levels of MCF recombinant ICs in one or two but not all three hematopoietic compartments tested.

MAb 514-reactive ICs were counted as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 1.

bdl, below the detection limit (<0.2 MAb 514-reactive ICs/106 cells).

An animal with MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the bone marrow.

An animal with MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the spleen.

None of the animals examined had MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the thymus.

MCF recombinant appearance and propagation in M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice.

Previous studies of wild-type and Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV indicated that the route of inoculation (i.p. versus s.c.) affected the efficiency of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV-induced leukemogenesis but not that of M-MuLV-induced leukemogenesis (1). Since leukemogenesis by M-MuLV is not dependent on the route of inoculation, studying MCF appearance in mice infected either i.p. or s.c. with M-MuLV might reveal common features important for efficient leukemogenesis.

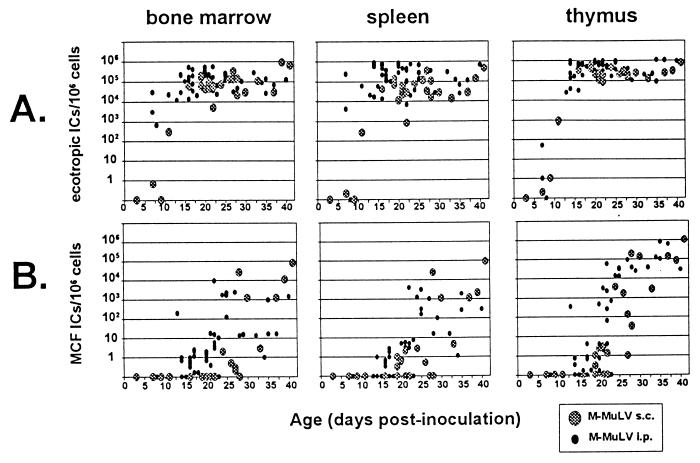

We infected neonatal mice with M-MuLV s.c. and measured the appearance of polytropic and ecotropic reactive ICs. Relative to i.p. inoculation, s.c. inoculation resulted in a slight delay in establishment of ecotropic-virus infection in the bone marrow and spleen but had little effect on establishment of infection in the thymus (Fig. 2A). We first detected MCF ICs at 19 to 28 days postinoculation, 1 week later than for i.p.-inoculated mice (Fig. 2B). Polytropic ICs were first detected in bone marrow cells after 24 days, versus 19 days in splenocytes and thymocytes. As in M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated animals, the numbers of polytropic ICs in each tissue at very early times were generally very small (0.2 to 10 per million cells plated). By 30 days postinfection, MCF recombinant ICs were detected in all three tissues in all animals, indicating general dissemination by that time. MCF recombinant ICs were detected 1 to 2 weeks later than when ecotropic M-MuLV IC numbers plateaued, and they amplified rapidly regardless of the inoculation route.

FIG. 2.

s.c. inoculation of M-MuLV. Neonatal mice were inoculated s.c. with M-MuLV, and the numbers of ecotropic and polytropic ICs were measured as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The data for s.c.-infected mice are shown in the large shaded circles. For comparison, data from Fig. 1 (i.p.-infected animals) are shown in the small solid circles.

The apparent 3- to 5-day delay in the appearance of MCF recombinants in the bone marrow with respect to the splenocytes and thymocytes of s.c.-inoculated mice suggested that they might form in some tissue other than bone marrow. Results for s.c.-inoculated animals discordant for MCF virus appearance are shown in Table 2. MCF recombinant ICs were detected in the bone marrow in only two of eight discordant animals; furthermore, none of the discordant animals tested showed MCF recombinants only in bone marrow cells. Four of eight discordant animals showed detectable MCF recombinant ICs in the spleen, and none showed infection only in the spleen. In contrast, all eight discordant animals showed MCF recombinant ICs in the thymus and two of these animals showed MCF recombinant ICs only in the thymus. In mouse 8 (Table 2), a substantial number of MCF recombinant ICs was measured in the thymus but none were detected in the bone marrow or spleen. These results suggested that a site other than the bone marrow (perhaps the thymus) might function as an MCF recombinant generation site following s.c. inoculation.

TABLE 2.

MCF recombinant IC counts from M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice discordant for MCF infectiona

| Mouse no. | Time (days) postinoculation | No. of MCF recombinant ICs/106 cells platedb in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrowd | Spleene | Thymus | ||

| 1 | 19 | bdlc | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 19 | bdl | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 20 | bdl | 0.7 | 2 |

| 4 | 21 | bdl | 0.2 | 3 |

| 5f | 22 | bdl | bdl | 1 |

| 6 | 27 | 0.3 | bdl | 1 |

| 7 | 27 | 0.2 | bdl | 133 |

| 8f | 28 | bdl | bdl | 34 |

| Fraction with detectable MCF ICs | 2/8 | 4/8 | 8/8 | |

Of 20 mice inoculated s.c. with M-MuLV that were examined at times between 7 and 37 days postinoculation, 8 had detectable numbers of MAb 514-reactive ICs in one or two but not all three hematopoietic compartments tested.

MAb 514-reactive ICs were counted as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 2.

bdl, below the detection limit (<0.2 MAb 514-reactive ICs/106 cells).

None of the animals examined had MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the bone marrow.

None of the animals examined had MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the spleen.

An animal with MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the thymus.

MCF virus appearance in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice.

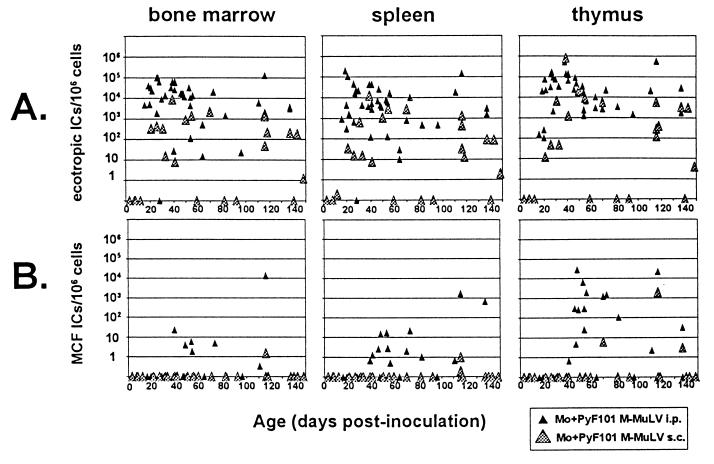

Since wild-type and Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV induce disease with similar efficiencies following i.p. inoculation (1), comparison of MCF recombinant appearance in mice infected i.p. by these two viruses was of interest. As shown in Fig. 3A, i.p. inoculation of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV resulted in a slight delay relative to M-MuLV i.p. inoculation in the establishment of ecotropic virus infection in each tissue, but the delay was more evident in the thymus, consistent with results of previous studies (1). At later times, the numbers of ecotropic ICs in the thymus were somewhat larger than in the bone marrow and spleen, but the difference was not as great as in M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice.

FIG. 3.

Inoculation of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV. Neonatal mice were inoculated i.p. with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV, and the numbers of ecotropic and polytropic ICs were measured as described in the legend to Fig. 1 (solid triangles). Data from mice inoculated s.c. by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV are shown in shaded triangles. Note that the timescale in this figure is different than in Fig. 1 and 2. Any animals that developed leukemia were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 3B shows the appearance of MCF recombinant ICs in cells of Mo+PyF101 i.p.-infected mice. Polytropic ICs were first detected after 40 days on average (compared to 13 days for M-MuLV i.p.-infected mice), and the time of appearance was also more variable than that for M-MuLV-infected mice. In addition, not all animals showed MCF recombinant ICs: only two-thirds of the animals tested between 39 and 96 days postinoculation showed detectable MCF recombinant ICs, and only one-fourth of the animals at these times showed MCF recombinant ICs in all three tissues. Finally, MCF recombinant IC titers measured in the bone marrow and spleen were 100- to 1,000-fold lower than in M-MuLV i.p.-infected mice. Thus, either MCF virus generation occurred much later or propagation of MCF recombinants to detectable levels was less efficient. As in M-MuLV-infected animals, however, MCF recombinant amplification was most efficient in the thymus in Mo+PyF101 i.p.-infected mice (generally 100-fold higher levels than in the bone marrow and spleen). The delay in appearance of MCF recombinants was noteworthy, since previous experiments had suggested an early role for MCF recombinants in efficient leukemogenesis by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV (2, 6, 22).

We also studied animals discordant for MCF virus appearance following i.p. inoculation with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV (Table 3). Only one discordant animal showed detectable MCF recombinant ICs in bone marrow. MCF recombinant ICs were detected in the spleens in six of nine and in the thymuses in eight of nine discordant animals. In three mice, appreciable MCF recombinant IC numbers were detected only in the thymus.

TABLE 3.

MCF recombinant IC counts from Mo+PyF101 i.p.-inoculated mice discordant for MCF infectiona

| Mouse no. | Time (days) postinoculation | No. of MCF recombinant ICs/106 cells platedb in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrowd | Spleene | Thymus | ||

| 1 | 39 | 23 | 0.7 | bdlc |

| 2 | 41 | bdl | 1 | 0.7 |

| 3 | 46 | bdl | 3 | 292 |

| 4f | 47 | bdl | bdl | 5 |

| 5f | 49 | bdl | bdl | 246 |

| 6f | 54 | bdl | bdl | 25 |

| 7 | 56 | bdl | 0.5 | 1,834 |

| 8 | 70 | bdl | 2 | 1,188 |

| 9 | 83 | bdl | 1 | 106 |

| Fraction with detectable MCF ICs | 1/9 | 6/9 | 8/9 | |

Of 34 mice inoculated i.p. with Mo+PyF101 that were examined at times between 16 and 96 days postinoculation, 9 had detectable levels of MCF recombinant ICs in one or two but not all three hematopoietic compartments tested.

MAb 514-reactive ICs were counted as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 3.

bdl, below the detection limit (<0.2 MAb 514-reactive ICs/106 cells).

None of the animals examined had MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the bone marrow.

None of the animals examined had MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the spleen.

An animal with MCF recombinant ICs exclusively in the thymus.

MCF recombinant proviruses in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice.

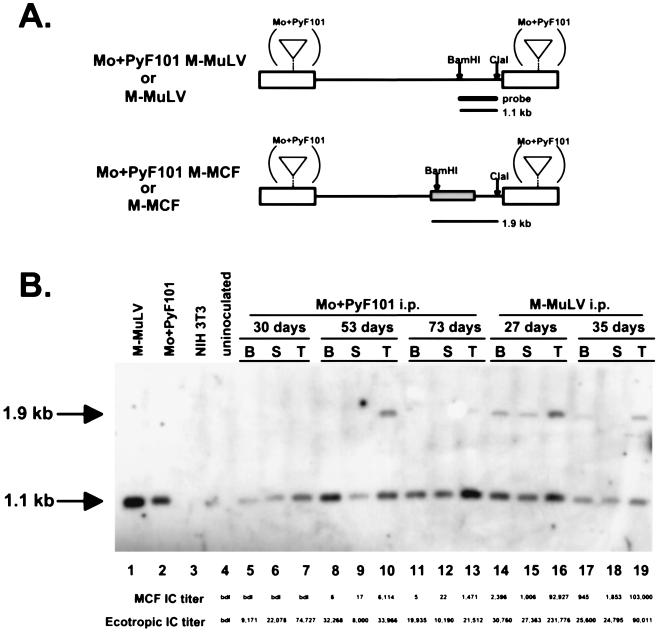

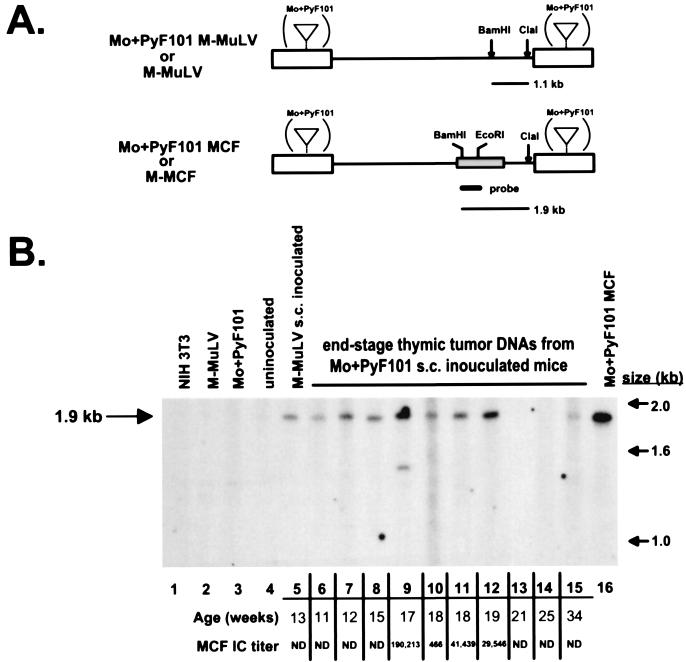

The delay in appearance and the inefficient amplification of MCF recombinants in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice was unexpected from our previous experiments (2, 6). Although unlikely, it was possible that Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV-infected mice developed significant levels of polytropic viruses that did not score as MAb 514-reactive ICs by FIA. To rule out this possibility, we tested DNAs from six Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-infected preleukemic mice for recombinant MCF proviruses by Southern blot analysis (2, 4). As shown in Fig. 4, digestion of the DNA with BamHI and ClaI and hybridization with a 3′ env probe yielded a 1.1-kb fragment diagnostic for ecotropic provirus and a 1.9-kb fragment diagnostic for MCF provirus (Fig. 4A). The 1.9-kb MCF recombinant-specific band could be detected in DNAs from Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV- and M-MuLV-infected tissue that showed MCF recombinant IC titers of >103 per million cells in most cases (Fig. 4B). Three additional preleukemic Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-infected animals (28, 56, and 70 days postinoculation) were tested, and similar results were observed: ecotropic but not polytropic provirus-specific bands were detected, and the numbers of MCF recombinant ICs were less than 1,000/106 cells.

FIG. 4.

Southern blot hybridization for ecotropic and polytropic proviruses. (A) Restriction endonuclease cleavage site maps of M-MuLV and Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV (top) and M-MCF and Mo+PyF101 M-MCF recombinant (bottom) proviruses. Only the BamHI and ClaI sites pertinent to the analysis are shown. The heavy bar indicates the probe. The box in the env gene shows the portion involved in the recombination. Digestion of proviral DNA with BamHI-ClaI yields a 1.1-kb fragment from the ecotropic M-MuLV provirus and a 1.9-kb fragment from the polytropic MCF recombinant provirus; both fragments hybridize with an ecotropic 3′ env probe. (B) High-molecular-weight DNA was prepared from bone marrow cells (lanes B), splenocytes (lanes S), and thymocytes (lanes T) from three mice inoculated with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p. and two mice inoculated with M-MuLV. The ages of the animals are indicated. A 10-μg sample of each DNA was digested with BamHI-ClaI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and subjected to Southern blot hybridization with the 3′ env probe shown in panel A. Lanes: 1, M-MuLV producer cell line DNA; 2, Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV producer cell line DNA; 3, NIH 3T3 cell line DNA; 4, uninoculated control thymus DNA; 5 to 13, DNAs from Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV-infected tissue; 14 to 19, DNAs from M-MuLV-infected tissue. Continuous lines above the lanes indicate tissues from the same animal. The tissue samples were also tested by FIA, and the numbers of ecotropic and MCF recombinant ICs per 106 cells plated are indicated below lanes 4 to 19. bdl: below the detection limit of the assay (<0.2 MCF recombinant ICs/106 cells).

MCF recombinants in tumors of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice.

In previous studies we did not detect MCF recombinants by Southern blot analysis in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-infected mice at preleukemic times or in end-stage tumors if they developed (6). We infected neonatal mice with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c. and tested them for MCF recombinant and ecotropic ICs at late preleukemic times and in animals that developed tumors (Fig. 3). Of 20 animals tested at times from 39 to 148 days, 4 had developed large thymic tumors and other characteristic signs of Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV-induced disease. Of the remaining 16 animals, 12 showed undetectable numbers of MCF recombinant ICs in all tissues. However, three showed very small but detectable numbers of MCF recombinant ICs in one or two tissue compartments (0.2 × 106 to 3/106 cells) and one showed substantial numbers of MCF recombinant ICs in the thymus (2 × 103/106 cells). The MCF recombinant IC results on the preleukemic animals were generally consistent with our previous studies (2) in that the percentage of animals that showed detectable MCF recombinant ICs was much lower following s.c. than i.p. inoculation.

Somewhat unexpectedly, we detected large numbers of MCF ICs in the thymic tumors (5 × 102 to 2 × 105/106 thymocytes) and in some instances significant numbers in the bone marrow and spleens (7 × 104/106 cells) of the four leukemic Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice. If MCF recombinant IC numbers and the MCF proviral content in these animals obeyed the same correlation as observed in Fig. 4, Southern blot analysis would be sensitive enough to detect MCF recombinant proviruses in these tumor DNAs. These four tumors and six additional Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-induced tumors from previous experiments were tested for MCF proviruses by Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 5). The 1.9-kbMCF recombinant-specific BamHI-ClaI fragment was readily detected in 7 of 10 tumor DNAs from mice inoculated s.c. with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV. A faint 1.9-kb hybridizing band was evident in one additional DNA (Fig. 5, lane 15), and no MCF provirus-specific band was visualized in two tumor DNAs. However, one of these DNAs (lane 13) was partially degraded in this experiment and was judged MCF recombinant positive in two additional Southern blot assays. In sum, 9 of the 10 tumor DNAs contained MCF proviruses at levels detectable by Southern blot hybridization. Thus, the experiments on Mo+PyF101 s.c.-inoculated animals indicated that MCF recombinant formation and propagation at preleukemic times was substantially reduced or undetectable. Nevertheless, the majority of the animals that developed tumors showed infection by MCF recombinants. For these animals, MCF recombinant formation was correlated with a late step in leukemogenesis.

FIG. 5.

M-MCF proviruses in tumor DNAs from Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice. (A) Restriction endonuclease cleavage site maps of the M-MuLV (top) and env gene MCF recombinant (bottom) proviruses. Only the 1.9-kb MCF recombinant-specific fragment hybridizes with the polytropic 5′ env probe. (A large hybridizing fragment from the ecotropic M-MuLV provirus was not in the region of the gel shown.) (B) A 10-μg sample of high-molecular-weight DNA obtained from end-stage tumors in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice was digested with BamHI-ClaI and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with the polytropic 5′ env probe shown in panel A. Lanes: 1, NIH 3T3 cell line DNA; 2, M-MuLV producer cell line DNA; 3, Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV producer cell line DNA; 4, uninoculated control thymus DNA; 5, tumor DNA from an M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated animal; 6 to 15, tumor DNAs from Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-inoculated mice; 16, cell line infected with a Mo+PyF101 MCF recombinant molecular clone. The ages of the animals are indicated below the lanes. Thymocytes from four tumor samples (lanes 9 to 12) were also tested by FIA (see Materials and Methods). The MAb 514 (polytropic)-reactive IC titers were calculated as ICs per 106 cells plated and are indicated below the lane numbers. ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated MCF recombinant appearance during infection by M-MuLV. MCF recombinant formation in vivo most probably requires two infection events: (i) ecotropic M-MuLV infection of a cell expressing an endogenous replication-defective polytropic MuLV, resulting in the production of heterozygous virions; and (ii) infection of a second cell, in which template switching during reverse transcription leads to formation an integrated replication-competent MCF provirus (5, 9). The latter cell would produce MCF recombinant virions (or ecotropic-pseudotyped MCF recombinants if it was also infected by M-MuLV). Cells that score as MCF recombinant ICs reflect the second cells involved in MCF recombinant generation or cells that subsequently propagate MCF recombinants. While MCF recombinant IC data cannot distinguish between “generator” and “propagator” cells, in animals where MCF recombinant have not disseminated to all tissues, MCF recombinant ICs will most probably reflect those involved in generation or the earliest stages of propagation.

For mice infected i.p. by M-MuLV, the fact that ecotropic M-MuLV infection established in the bone marrow and spleen more rapidly than in the thymus suggested that MCF recombinant generation might be more likely to occur in these tissues. MCF recombinant ICs first appeared at approximately the same time in all three tissues, i.e., beginning at 13 to 15 days. However, as shown in Table 1, in discordant animals the bone marrow was included as a site of first appearance of MCF recombinants in virtually every case. This supported the hypothesis that the bone marrow is a likely site of MCF recombinant generation in M-MuLV-infected mice (2). At the same time, these experiments did not rule out the possibility that MCFs were generated in multiple tissues in the same or different animals. Another conclusion from the M-MuLV i.p.-inoculated mice was that once formed, MCF recombinants propagate to higher levels in the thymus, i.e., 1 to 2 log units higher than in bone marrow or spleen. This was consistent with results of previous studies (20).

It was interesting and somewhat surprising that the patterns of initial appearance of MCF recombinants were different for mice inoculated with M-MuLV s.c. vs. i.p. While the plateau levels of MCF recombinant infection were similar for s.c.- and i.p.-infected mice, s.c.-inoculated animals discordant for MCF recombinant infection did not show patterns consistent with generation in the bone marrow. Only 25% of discordant mice showed MCF recombinant ICs in the bone marrow, while 100% showed MCF virus infection in the thymus (Table 2). Thus, it seems more likely that MCF recombinant generation occurs predominantly in the thymus after s.c. inoculation by M-MuLV.

Studies with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV provided additional insights into MCF recombinant generation and early propagation. When this virus was injected by the i.p. route, MCF recombinants formed, although with a substantial delay relative to that in wild-type–M-MuLV-infected mice (Fig. 3). The delay might reflect the fact that in general the viral loads in animals infected i.p. by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV were somewhat lower than in those infected by wild-type M-MuLV. Amplification of MCF recombinants in the Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-infected animals occurred in the thymus at later times, the same as for wild-type–M-MuLV-infected mice. When animals discordant for MCF virus infection were analyzed, the patterns favored generation and initial propagation primarily in the thymus, not in the bone marrow (Table 3). Thus, the nature of the M-MuLV enhancer sequences appeared to affect the site(s) of MCF recombinant generation, even when the same route of inoculation was used. When mice were inoculated with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV by the s.c. route (where they show attenuated leukemogenicity), very few preleukemic animals showed MCF recombinants even by the sensitive FIA, consistent with results of our previous studies (6).

Another goal of these experiments was to test the hypothesis that MCF recombinants are important for early (preleukemic) events in M-MuLV leukemogenesis. We previously suggested that MCF recombinants are involved in preleukemic M-MuLV-induced events such as splenic hyperplasia, bone marrow hematopoietic defects, and accelerated thymic atrophy (15). The detailed analyses carried out here indicate that this hypothesis is unlikely to be correct. While MCF recombinants first appeared in M-MuLV-infected mice well before the preleukemic events (13 to 15 days), the levels of infection were low, i.e., plateau levels of 103 to 104 ICs per 106 cells (0.1 to 1% MCF recombinant infection) in the bone marrow and spleen. Thus, in these tissues that were undergoing substantial preleukemic changes, most of the cells were not infected by MCF recombinants.

The lack of a role for MCF recombinants in M-MuLV-induced preleukemic changes was further substantiated by the studies on mice infected by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV. Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-infected animals develop leukemia with the same efficiency as wild-type–M-MuLV-infected mice and show the same preleukemic changes (1). The substantial delay in the appearance of MCF recombinants in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV i.p.-infected mice was not reflected in a delay of preleukemic events. Moreover, several individual animals that showed clear evidence of preleukemic splenomegaly had no detectable MCF recombinants. Similarly, several mice infected by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV that showed preleukemic thymic atrophy showed no detectable MCF recombinants in the thymus (3). A similar lack of correlation between MCF recombinants and induction of splenomegaly (erythroid hyperplasia) induced by Friend MuLV has been reported (30). However, in the experiments described here, only the nonadherent cells from the spleen and thymus were analyzed. If MCF recombinant infection of adherent (stromal) elements led to preleukemic changes, this might have escaped detection. On the other hand, for the bone marrow, all of the cells (including stromal cells) were analyzed, but it is still possible that MCF virus infection of a minority subset of cells in the bone marrow is important.

At the same time, these experiments provide strong support for a role of MCF recombinants in later steps in leukemogenesis. In particular, in mice inoculated with Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV by the s.c. route, the great majority that did not have tumors had undetectable or extremely small numbers of MCF recombinant ICs. Nevertheless, most of the tumors in the individuals that developed leukemia were MCF virus infected. Thus, for these animals, there was a strong selection for MCF recombinants in the tumors. The appearance of MCFs may have been the final rate-limiting event for disease development. The overall reduced rate of leukemogenesis by Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV after s.c. inoculation may have resulted from both the low levels of MCF recombinants formed and a lower level of ecotropic virus load (compare Fig. 3 with Fig. 2).

As mentioned in Results, we previously did not detect MCF recombinants in Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-infected tumors by Southern blot analysis (6), whereas in the present experiments we did. This was probably due to the restriction endonucleases used. Previously, a BamHI-XbaI digest was used to test for a 2.3-kb MCF virus-diagnostic fragment that hybridized to an MCF virus env-specific probe (6). The diagnostic fragment was only slightly smaller than restriction fragments corresponding to endogenous MuLV proviruses in NIH Swiss mice. In retrospect, two classes of LTR changes could have resulted in failure to detect the MCF virus-diagnostic BamHI-XbaI fragment. Multimerization of M-MuLV enhancer sequences in the Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV LTR could result in comigration of the diagnostic MCF virus fragment with an endogenous MuLV-related fragment. Alternatively, deletion of polyomavirus enhancer sequences and the adjacent XbaI site could have converted the MCF virus-diagnostic fragment to viral-cellular junction fragments of indeterminate size. In subsequent studies, we observed both classes of LTR alterations (2, 4). The BamHI-ClaI restriction digestion used in these experiments is not influenced by alterations in the Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV LTR. Indeed, several of the previously isolated tumor samples illustrated in Fig. 5 that showed the MCF virus-diagnostic 1.9-kb BamHI-ClaI fragment had been previously classified as MCF virus negative on the basis of the BamHI-XbaI digest (6). Additional Southern blot digestions confirmed that the Mo+PyF101 M-MuLV s.c.-induced tumors had LTR rearrangements consisting of either or deletions or expansions of the enhancer sequences (results not shown).

In summary, several conclusions resulted from these studies. First, both the route of inoculation and the nature of the enhancers appeared to affect the sites of MCF recombinant generation and/or early propagation in M-MuLV-infected mice. Second, the initial site(s) of MCF recombinant appearance does not appear to affect the efficiency of leukemogenesis. Third, MCF recombinants do not appear to be involved in establishing M-MuLV-induced preleukemic changes. Finally, MCF recombinants are more likely to be involved in late steps in leukemogenesis such as activation of proto-oncogenes, induction of cytokine autocrine loops, and activation of tumor progression genes (15, 16).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christine Lee, Tina Pham, Jeremy Shaw, and Grace Lee for technical assistance.

J.K.L. was supported by NIH training grants T32 GM 07134 and T32 CA09054. This work was supported by grant RO1 CA-32455 from the National Cancer Institute. Support by the UCI Cancer Research Institute and the UCI Cancer Center is acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belli B, Fan H. The leukemogenic potential of an enhancer variant of Moloney murine leukemia virus varies with the route of inoculation. J Virol. 1994;68:6883–6889. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6883-6889.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belli B, Patel A, Fan H. Recombinant mink cell focus-inducing virus and long terminal repeat alterations accompany the increased leukemogenicity of the Mo+PyF101 variant of Moloney murine leukemia virus after intraperitoneal inoculation. J Virol. 1995;69:1037–1043. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1037-1043.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonzon C, Fan H. Moloney murine leukemia virus-induced preleukemic thymic atrophy and enhanced thymocyte apoptosis correlate with disease pathogenicity. J Virol. 1999;73:2434–2441. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2434-2441.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brightman B K, Farmer C, Fan H. Escape from the in vivo restriction of Moloney mink cell focus-inducing (MCF) viruses driven by the Mo+PyF101 LTR by LTR alterations. J Virol. 1993;67:7140–7148. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7140-7148.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brightman B K, Li Q X, Trepp D J, Fan H. Differential disease restriction of Moloney and Friend murine leukemia viruses by the mouse Rmcf gene is governed by the viral long terminal repeat. J Exp Med. 1991;174:389–396. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brightman B K, Rein A, Trepp D J, Fan H. An enhancer variant of Moloney murine leukemia virus defective in leukemogenesis does not generate detectable mink cell focus-inducing virus in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2264–2268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2264. . (Erratum, 88:5066.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chesebro B, Britt W, Evans L, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Cloyd M. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies reactive with murine leukemia viruses: use in analysis of strains of friend MCF and Friend ecotropic murine leukemia virus. Virology. 1983;127:134–148. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coen D. Quantitation of rare DNAs by PCR. In: Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1988. pp. 15.3.1–15.3.2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffin J M. Retroviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 745–843. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis B, Linney E, Fan H. Suppression of leukaemia virus pathogenicity by polyoma virus enhancers. Nature. 1985;314:550–553. doi: 10.1038/314550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis B R, Brightman B K, Chandy K G, Fan H. Characterization of a preleukemic state induced by Moloney murine leukemia virus: evidence for two infection events during leukemogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4875–4879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis B R, Chandy K G, Brightman B K, Gupta S, Fan H. Effects of nonleukemogenic and wild-type Moloney murine leukemia virus on lymphoid cells in vivo: identification of a preleukemic shift in thymocyte subpopulations. J Virol. 1986;60:423–430. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.423-430.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans L H, Cloyd M W. Friend and Moloney murine leukemia viruses specifically recombine with different endogenous retroviral sequences to generate mink cell focus-forming viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:459–463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans L H, Morrey J D. Tissue-specific replication of Friend and Moloney murine leukemia viruses in infected mice. J Virol. 1987;61:1350–1357. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1350-1357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan H. Leukemogenesis by Moloney murine leukemia virus: a multistep process. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:74–82. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(96)10076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan H. Retroviruses and their role in cancer. In: Levy J A, editor. The Retroviridae. III. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 313–362. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan H, Chute H, Chao E, Pattengale P K. Leukemogenicity of Moloney murine leukemia viruses carrying polyoma enhancer sequences in the long terminal repeat is dependent on the nature of the inserted polyoma sequences. Virology. 1988;166:58–65. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartley J W, Wolford N K, Old L J, Rowe W P. A new class of murine leukemia virus associated with development of spontaneous lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:789–792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herr W, Gilbert W. Somatically acquired recombinant murine leukemia proviruses in thymic leukemias of AKR/J mice. J Virol. 1983;46:70–82. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.1.70-82.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavignon M, Evans L. A multistep process of leukemogenesis in Moloney murine leukemia virus-infected mice that is modulated by retroviral pseudotyping and interference. J Virol. 1996;70:3852–3862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3852-3862.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J P, Baltimore D. Mechanism of leukemogenesis induced by mink cell focus-forming murine leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1991;65:2408–2414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2408-2414.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q X, Fan H. Combined infection by Moloney murine leukemia virus and a mink cell focus-forming virus recombinant induces cytopathic effects in fibroblasts or in long-term bone marrow cultures from preleukemic mice. J Virol. 1990;64:3701–3711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3701-3711.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linney E, Davis B, Overhauser J, Chao E, Fan H. Non-function of a Moloney murine leukaemia virus regulatory sequence in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. Nature. 1984;308:470–472. doi: 10.1038/308470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullis K, Faloona F, Scharf S, Saiki R, Horn G, Erlich H. Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: the polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1986;51:263–273. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rein A. Interference grouping of murine leukemia viruses: a distinct receptor for the MCF-recombinant viruses in mouse cells. Virology. 1982;120:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowe W P, Pugh W E, Hartley J W. Plaque assay techniques for murine leukemia viruses. Virology. 1970;42:1136–1139. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saiki R K, Scharf S, Faloona F, Mullis K B, Horn G T, Erlich H A, Arnheim N. Enzymatic amplification of beta-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science. 1985;230:1350–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.2999980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sitbon M, Ellerbrok H, Pozo F, Nishio J, Hayes S F, Evans L H, Chesebro B. Sequences in the U5-gag-pol region influence early and late pathogenic effects of Friend and Moloney murine leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1990;64:2135–2140. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2135-2140.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sitbon M, Evans L, Nishio J, Wehrly K, Chesebro B. Analysis of two strains of Friend murine leukemia viruses differing in ability to induce early splenomegaly: lack of relationship with generation of recombinant mink cell focus-forming viruses. J Virol. 1986;57:389–393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.1.389-393.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sitbon M, Nishio J, Wehrly K, Lodmell D, Chesebro B. Use of a focal immunofluorescence assay on live cells for quantitation of retroviruses: distinction of host range classes in virus mixtures and biological cloning of dual-tropic murine leukemia viruses. Virology. 1985;141:110–118. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoye J P, Moroni C, Coffin J M. Virological events leading to spontaneous AKR thymomas. J Virol. 1991;65:1273–1285. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1273-1285.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]