Abstract

The optimization of hydration temperature and duration were determined in six basmati and non-basmati paddy cultivars varying in grain size, shape, and amylose content based on kinetic parameters and effect of hydration temperature on physical, milling, textural and color attributes. Based on higher R2, lower Chi square and RMSE values, Peleg model fitted more suitably compared to Singh and Kulshrestha model. Hydration process significantly altered geometric, gravimetric and mechanical properties as evident by regression analysis. Physical properties except length and L/B ratio positively correlated with increasing hydration temperature. Head rice yield significantly improved in the hydrated treatments and showed a linear increase with the increase in hydration temperature. Head rice yield significantly correlated with hardness of grain (r = 0.684, p ≤ 0.01). Variable physico-chemical properties of cultivars led to establishment of cultivar specific optimum hydration temperature. Based on improvement in hardness, milling efficiency, head rice yield, color and textural attributes, the optimized temperature emerged as 75 °C for long slender grained cultivars (PB1509, PB1718, PS17) and 80 °C for medium grained cultivars (PD18, KJ, AL). The results revealed that optimum hydration temperature should be cultivar specific to get better output of parboiling process.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13197-024-05925-1.

Keywords: Hardness, Head rice, Hydration, Kinetics, Paddy, Physical properties, Water absorption

Introduction

Paddy, the harvestable form of rice (Oryza sativa L.) crop, undergoes several stages of processing (cleaning, tempering, dehulling, parboiling, milling, etc.) before it reaches consumers in edible (brown/white rice) form. Of these, parboiling is most popular and applied to approximately half of Indian and about one–fourth of the world paddy (Kar et al. 1999). Parboiling, a hydrothermal treatment, involves hydration (or soaking), steaming and drying processes. Parboiling affects the physical, nutritional, textural, rheological and cooking properties of rice (Dutta and Mahanta 2012; Kale et al. 2015); and causes differences in milling quality (Buggenhout et al. 2013; Mihretu et al. 2023), geometrical and density properties of paddy (Ji-u and Inprasit 2019). The physico-chemical attributes of rice grain are known to affect processing, handling, marketability and end- product quality of milled rice (Sharma et al. 2023).

Multiple phases of rice parboiling contributed to physico-chemical changes (Priya et al. 2019). Hydration is a critical step in parboiling wherein moisture content of paddy is increased to attain gelatinization during subsequent steaming step. The importance of hydration during parboiling processing, led researchers to evaluate water absorption characteristics of paddy. Water absorption, during hydration, is a temperature dependent process as lower temperature hydration caused microbial growth, affected aroma and color of kernels, while very high temperature caused splitting of husk, and increased amounts of leached solids (Kale et al. 2017). Therefore, optimizing the hydration temperature can improve parboiling outturn in desired direction.

Due to variable physical and chemical attributes of different rice cultivars (Aruva et al. 2020), each cultivar requires specific hydration processing. Therefore, hydration process needs to be optimized for different paddy cultivars.

A lot of work has been done on parboilization of non-aromatic rice cultivars; however, comparative studies on the effect of hydration treatment on quality characteristics of different cultivars varying in physico-chemical properties have not been explored much so far. Therefore, present study includes widely used basmati as well as non-basmati cultivars of major rice growing zones of India, which differs in various physico-chemical properties such as amylose content, grain shape, size and aroma. The objective of present study was (i) to analyze impact of hydration temperature and duration on hydration kinetics, (ii) investigate the effects of different hydration temperatures on physical, milling, textural and color attributes of paddy and rice, (iii) to understand how the differences among cultivars affect the hydration process, and (iv) optimize hydration conditions for different paddy cultivars based on improvement in milling efficiency and quality characteristics.

Materials and methods

Materials

Six paddy cultivars were chosen to study the impact of hydration temperature on rice quality. Pusa Basmati 1509 (PB1509) and Pusa Basmati 1718 (PB1718) were procured from ICAR (Indian Council of Agricultural Research)- IARI (Indian Agricultural Research Institute), New Delhi, and Pant Sugandh 17 (PS17) and Pant Dhan 18 (PD18) were procured from Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Pantnagar. Keteki Joha (KJ) and Assam Local (AL) were procured from local farmers of Odisha, and Assam.

Hydration of paddy

Paddy samples of 500 g for each cultivar were hydrated (paddy and water ratio of 1:4) at three soaking temperatures (70, 75 and 80 °C) using thermostatic water bath (Equitron Concentric Ring Bath, Medica Instrument Mfg. Co.) and one control (unsoaked) was kept. Hydration was continued till paddy achieved critical moisture content (CMC) which was measured by preliminary water absorption studies (Kale et al. 2013). After removing surface moisture by blotting paper, samples were evaluated for physical, milling, textural and color properties.

Hydration kinetics

Two empirical models viz., PM [Peleg model (Peleg 1988)], and SKM [Singh and Kulshrestha model (Singh and Kulshrestha 1987)] were used to determine the hydration kinetics.

The moisture uptake kinetics data were fitted to PM:

| 1 |

SKM involves a single rate constant:

| 2 |

Linearized form of Eq. 2 is described as:

| 3 |

where M, m represents transient moisture content (% db); Mo and m represent, initial moisture content (% db); t represents time (min) for PM and SKM, respectively. k represents rate constant [SKM] and k1 and k2 represent Peleg rate constant, Peleg capacity constant [PM].

Moisture content of paddy

The moisture content of paddy grains was determined by hot air oven method of AOAC (2005).

Physical properties

Physical properties such as geometrical, gravimetric and mechanical properties of paddy were evaluated.

Axial dimensions (length (L), breadth (B) and thickness (T)), L/B ratio and AR (or Ra) were measured using Vernier caliper (least count: 0.02 mm, Aerospace Ltd, China).

The equivalent diameter (De), geometric mean diameter (Dg), arithmetic average diameter (Da), square mean diameter (Ds), volume (V), surface area (S), Sphericity (Φ or SPH), and swelling index (SI) were calculated according to equations proposed (Azuka et al. 2021; El Fawal et al. 2009; Panda and Shrivastava 2019; Varnamkhasti et al. 2008).

Bulk density (BD), tapped density (TD), true density (TrD), Carr’s Index (CI), Hausner Ratio (HR), and Porosity were estimated by method of Meera et al (2019).

For measuring thousand kernel weight (TKW), randomly selected 1000 paddy grains were weighed using precision electronic balance (accuracy 0.001 g, M/s. Precisa, XB 220A, Precisa Instrument) (Varnamkhasti et al. 2008).

Angle of Repose (AOR or Ar) was measured as described by Meera et al (2019).

Coefficient of Friction (COF) of paddy was determined on plywood (COF-PW), stainless steel (COF-SS) and glass (COF-G) surface as suggested by Jadhav et al (2020).

Milling properties

Paddy dried to below 13% moisture was dehusked (Satake Rubber Roll Sheller) followed by polishing (Satake Grain Testing Mill) to obtain hulling, milling, head rice yield (HRY) and broken percentage (Alizadeh 2011).

Grain hardness

Grain hardness (GH) of white rice was measured using Texture Analyzer (TA-XT2i, Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, UK) as described by Sharma et al (2022).

Color

Color of milled grains were measured using Tri- stimulus Hunter Colorimeter (M/s Miniscan XE Plus, Model No. 45/O-S, Hunter Associates Laboratory, Inc. Reston, VA, USA) as described by Sharma et al (2023).

Statistical analysis

ANOVA was carried out using SPSS, 2002. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were estimated using OPSTAT (Sheoran et al. 1998). Regression analysis was carried out using standard method and regression equations were established. Coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and Chi square (χ2) values for goodness of fit were calculated using standard methods to compare observed and predicted values for empirical models for hydration kinetics.

Results and discussion

Hydration characteristics

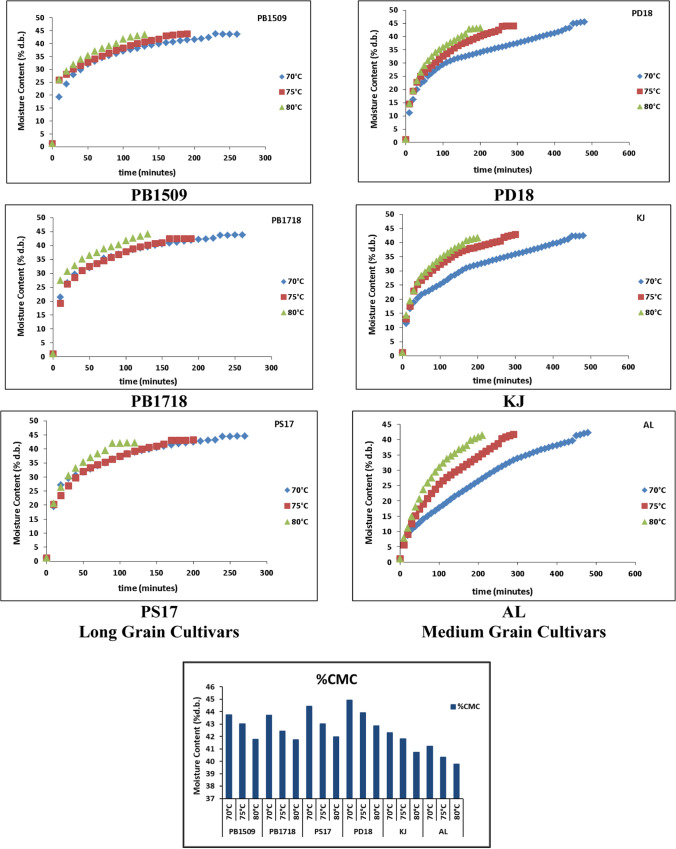

Water absorption behavior during hydration (Fig. 1) revealed that with increase in hydration temperature, hydration rate increased. It may be due to reduction in water viscosity and increase in agitation of water molecules at high temperatures of hydration medium (Balbinoti et al. 2018).

Fig. 1.

Hydration behavior of different paddy cutivars at variable hydration temperature

Water absorption during hydration was observed to be temperature dependent process. Higher water uptake was observed at higher temperature, and found to be highest at 80 °C which could be due to instigation of gelatinization of starch or softening of the grain. At higher temperature, more energy was generated that disrupted hydrogen bonds and weakened the structure of starch granules, in turn, increased the rate of water diffusion (Kale et al. 2013).

Estimation of % CMC is important not only to identify termination of the hydration step but also to ensure the energy efficiency of process. As continuation of hydration beyond % CMC will lead to gelatinization of rice, undesirable higher leaching losses and reduce process efficiency. Results indicated that % CMC decreased with increase in hydration temperature (Fig. 1). Average % CMC varied from cultivar to cultivar and was dependent upon amylose content. Highest (43.90% d.b.) and lowest (40.44% d.b.) average % CMC were observed in high (PD18) and low (AL) amylose cultivars.

The hydration duration varied greatly amongst cultivars studied. As evident, higher hydration temperature reduced hydration duration by increasing hydration rate in achieving CMC by paddy at all temperatures. Consequently, overall process completed in lesser time, besides, retention of higher nutrient by grains due to lower leaching of soluble solids.

Long slender grain cultivars (PB1509, PB1718 and PS17) because of their higher hydration rate achieved CMC much earlier than medium grain cultivars (PD18, KJ and AL). At 70 °C, KJ, PD18 and AL achieved desired CMC after 450 min of continuous hydration, while, PB1509, PB1718 and PS17 achieved desired CMC in 230 min. Hydration duration was observed to be 160 and 240 min at 75 °C, 100 and 170 min at 80 °C, for long slender and medium grained cultivars, respectively.

Although, both PD18 (high amylose) and AL (low amylose) had similar hydration duration, but, water absorption, hydration rate and % CMC varied significantly for both cultivars. PD18 showed higher (43.90%) total water absorption (% CMC) due to high amylose as compared to AL (40.44%). Average CMC (% d.b.) for other cultivars was 41.62% for KJ, 42.63% for PB1718, 42.84% for PB1509, and 43.15% for PS17. Significant positive correlation (r = 0.980, p ≤ 0.01) was found between amylose and total water absorbed (average % CMC). The variation in water absorption characteristics among different cultivars could be attributed to physico-chemical characteristics of cultivars, soil type, cultivation method and other environmental factors.

Hydration kinetics

PM and SKM were used to determine moisture uptake kinetics during hydration process for studied paddy cultivars. Linear regression was employed to determine all the model parameters (k1 and k2 for PM, and k and me for SKM) as shown in Table 1. PM depicted that k1 is the initial hydration value, and k2 is linked to the maximum water absorption capacity or the equilibrium moisture content. Peleg’s rate constant (k1) is related with diffusion coefficient or mass transfer and decreased with increasing hydration temperature for all cultivars, indicating higher water absorption rate at higher temperatures of hydration. With increase in hydration temperature, k2 values decreased for all the cultivars, indicating higher water absorption capacity at higher hydration temperature. The lowest k2 values was observed for cultivar AL while highest values were depicted by PB1718 and PB1509. Lower k1 values were observed for long slender cultivars (PB1509, PB1718 and PS17) whereas medium cultivars (PD18, KJ and AL) depicted higher k1 values. The k1 and k2 values obtained from Eq. 1 were used to estimate moisture content at any time. The comparison of experimentally obtained values and predicted values depicted a good agreement as witnessed by the high R2 (0.946–0.998) (Table 1). The difference between the experimental and the predicted values was not significantly different based on lower Chi-square and RMSE values at p ≤ 0.05.

Table 1.

Parameters of hydration kinetics of paddy by Peleg model and Singh and Kulshrestha model

| Cultivar | Peleg model | Singh and Kulshrestha model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | k1 | k2 | R2 | χ2 | RMSE | k | me | R2 | χ2 | RMSE | |

| PB1509 | 70 | 0.544 | 0.022 | 0.985 | 1.997 | 1.310 | 0.069 | 433.174 | 0.974 | 1.790 | 1.570 |

| 75 | 0.436 | 0.022 | 0.945 | 4.560 | 2.497 | 0.129 | 41.317 | 0.933 | 4.017 | 2.733 | |

| 80 | 0.318 | 0.022 | 0.972 | 2.282 | 1.910 | 0.131 | 42.652 | 0.970 | 1.351 | 1.863 | |

| PS1718 | 70 | 0.480 | 0.022 | 0.978 | 3.276 | 1.518 | 0.085 | 42.969 | 0.968 | 2.013 | 1.673 |

| 75 | 0.478 | 0.022 | 0.985 | 1.643 | 1.333 | 0.072 | 43.322 | 0.979 | 1.134 | 1.456 | |

| 80 | 0.285 | 0.022 | 0.971 | 2.276 | 1.954 | 0.150 | 42.795 | 0.973 | 1.152 | 1.766 | |

| PS17 | 70 | 0.545 | 0.021 | 0.973 | 4.094 | 1.719 | 0.073 | 43.667 | 0.963 | 2.402 | 1.817 |

| 75 | 0.545 | 0.021 | 0.980 | 2.871 | 1.535 | 0.074 | 42.610 | 0.960 | 2.575 | 2.078 | |

| 80 | 0.374 | 0.021 | 0.994 | 0.418 | 0.889 | 0.073 | 45.758 | 0.984 | 1.149 | 1.621 | |

| PD18 | 70 | 1.520 | 0.021 | 0.959 | 10.969 | 2.080 | 0.032 | 40.957 | 0.917 | 10.253 | 2.770 |

| 75 | 0.967 | 0.021 | 0.980 | 4.849 | 1.578 | 0.043 | 42.439 | 0.942 | 5.464 | 2.603 | |

| 80 | 0.760 | 0.020 | 0.992 | 1.285 | 1.052 | 0.042 | 44.594 | 0.976 | 2.056 | 1.907 | |

| KJ | 70 | 1.777 | 0.022 | 0.958 | 14.650 | 2.031 | 0.036 | 37.354 | 0.870 | 17.737 | 3.454 |

| 75 | 0.922 | 0.022 | 0.988 | 2.088 | 1.128 | 0.038 | 42.451 | 0.974 | 2.429 | 3.830 | |

| 80 | 0.774 | 0.021 | 0.991 | 1.344 | 1.077 | 0.044 | 42.615 | 0.975 | 1.864 | 1.781 | |

| AL | 70 | 3.804 | 0.018 | 0.982 | 7.779 | 1.421 | 0.017 | 34.436 | 0.859 | 53.913 | 5.593 |

| 75 | 2.317 | 0.018 | 0.994 | 0.787 | 0.874 | 0.010 | 51.102 | 0.988 | 1.753 | 1.453 | |

| 80 | 1.608 | 0.017 | 0.999 | 0.286 | 0.402 | 0.015 | 49.646 | 0.991 | 0.787 | 0.874 | |

k: Rate constant, k1: Peleg rate constant, k2: Peleg capacity constant, me: Equilibrium moisture constant, R2: Coefficient of determination, RMSE: Root mean square error, χ 2: Chi square

SKM is useful for estimation of equilibrium moisture content without extended investigations. The rate constant k and me calculated from Eq. 2 was used to estimate moisture content at any time (Table 1). The comparison of experimental and predicted values depicted a good agreement as indicated by R2 (0.859–0.991) in SKM (Table 1). The difference between the predicted and experimentally obtained values was not significantly different based on lower Chi-square and RMSE values at p ≤ 0.05. The results are in agreement with the findings of Aruva et al (2020) and Singh and Vishwanathan (2010). Between the two models, PM fitted more adequately for moisture uptake during hydration than the SKM, as depicted by higher R2, and lower Chi-square and RMSE values.

Effect of hydration on physical (geometrical, gravimetric and mechanical) properties of paddy

Physical properties of rice are important for designing equipment for processing operations. Lower SPH value of PB1509 (0.30 mm) indicated towards cylindrical shape of the grain and it would likely be difficult for kernels to roll (Table 2). Lower AR among raw grains indicates easiness of grains to slide, which could be due to smoother outer surface and shape of the grain (El Fawal et al. 2009). Based on variation in grain shape and size, PB1509, PB1718 and PS17 can be classified as long slender, while PD18 as long bold, KJ as medium slender and AL as medium bold grained cultivars. Axial dimensions were significantly altered after the hydration treatment. Ahromrit et al. (2006) reported that moisture gain and filling, and subsequent widening of cracks might be the possible causes for dimensional changes.

Table 2.

Effect of hydration treatment on Axial dimensions, L/B ratio, sphericity and aspect ratio of paddy

| Cultivar | Hyd. Tret. | L (mm) | B (mm) | T (mm) | L/B | SPH (mm) | AR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1509 | Con | 13.96 ± 0.01 | 2.40 ± 0.01 | 2.20 ± 0.01 | 5.82 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| 70 °C | 13.86 ± 0.02 | 2.42 ± 0.01 | 2.40 ± 0.01 | 5.73 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 13.82 ± 0.01 | 2.46 ± 0.02 | 2.42 ± 0.01 | 5.62 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 13.76 ± 0.01 | 2.50 ± 0.01 | 2.46 ± 0.01 | 5.50 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | |

| PB1718 | Con | 13.36 ± 0.02 | 2.60 ± 0.01 | 2.40 ± 0.01 | 5.14 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 70 °C | 13.22 ± 0.02 | 2.80 ± 0.01 | 2.40 ± 0.01 | 4.72 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 13.19 ± 0.01 | 2.83 ± 0.02 | 2.48 ± 0.02 | 4.66 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 13.15 ± 0.01 | 2.86 ± 0.02 | 2.54 ± 0.01 | 4.60 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | |

| PS17 | Con | 13.39 ± 0.02 | 2.76 ± 0.01 | 2.10 ± 0.02 | 4.85 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| 70 °C | 13.15 ± 0.01 | 2.81 ± 0.01 | 2.32 ± 0.01 | 4.68 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 13.09 ± 0.02 | 2.86 ± 0.02 | 2.34 ± 0.01 | 4.58 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 13.08 ± 0.01 | 2.90 ± 0.01 | 2.38 ± 0.01 | 4.51 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | |

| PD18 | Con | 10.95 ± 0.01 | 2.50 ± 0.01 | 2.20 ± 0.01 | 4.38 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| 70 °C | 10.76 ± 0.01 | 2.67 ± 0.01 | 2.42 ± 0.02 | 4.03 ± 0.01 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 10.70 ± 0.01 | 2.72 ± 0.01 | 2.46 ± 0.01 | 3.93 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 10.72 ± 0.01 | 2.74 ± 0.02 | 2.52 ± 0.02 | 3.91 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | |

| KJ | Con | 8.97 ± 0.01 | 2.61 ± 0.01 | 2.22 ± 0.01 | 3.43 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 |

| 70 °C | 8.80 ± 0.01 | 2.82 ± 0.01 | 2.23 ± 0.01 | 3.12 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 8.76 ± 0.02 | 2.84 ± 0.02 | 2.28 ± 0.01 | 3.08 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 8.71 ± 0.01 | 2.85 ± 0.01 | 2.30 ± 0.01 | 3.05 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | |

| AL | Con | 8.00 ± 0.06 | 3.60 ± 0.01 | 2.80 ± 0.01 | 2.22 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| 70 °C | 7.80 ± 0.12 | 3.75 ± 0.01 | 2.98 ± 0.01 | 2.08 ± 0.02 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 7.72 ± 0.01 | 3.82 ± 0.01 | 3.20 ± 0.01 | 2.02 ± 0.01 | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 7.71 ± 0.01 | 3.90 ± 0.01 | 3.26 ± 0.02 | 1.98 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | |

| C.D.* | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |

| SE (m) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.021 | 0.01 | |

| SE (d) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| C.V. | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1.92 | |

L: Length, B: Breadth, T: Thickness, L/B: Length/ breadth, SPH: Sphericity, AR: Aspect ratio, Con: Control. Mean ± SE. *5% level of probability

There was decrease in L and L/B ratio after the hydration treatment, however, B, T and AR increased. Paddy T (0.086%) showed maximum average gain followed by B (0.05%), while, L showed negative gain (− 0.019%). This alteration could be attributed to the arrangements of the cells in rice kernel that is variable in both longitudinal as well as transverse directions. This causes preferential breakdown of endosperm cell walls in the lengthwise direction. Thus, it could be inferred that paddy husk provides hindrance to the grain for swelling to expand in lengthwise while white rice is free to expand in lengthwise direction. This could be the probable reason for higher increase in T and B as compared to L (Kale et al. 2017). Both grain B and L were the deciding components of the AR, therefore, changes in these parameters due to hydration led to change in AR too. Positive correlations were observed amongst B, T, SPH and AR after hydration temperature, whereas, negative correlation existed amongst L and L/B ratio after hydration temperature as evident from regression equations (Supplementary). Length depicted positive correlation with L/B (r = 0.963, p ≤ 0.01), while negative correlation with B, T, AR, SPH (r = -0.702, -0.533, -0.909, -0.918 p ≤ 0.01), respectively. T and B depicted positive correlation with each other (r = 0.877, p ≤ 0.01). T depicted positive correlations with SPH and AR (r = 0.802 and 0.790, p ≤ 0.01), respectively.

In comparison to control, the maximum % decrease in L (− 0.007%) and L/B ratio (− 0.15%) were observed in PB1509 at 70 °C. The maximum % increase for B (0.10%) and AR (0.158%) were exhibited by PB1718 at 80 °C. Similarly, maximum % increase for T (0.164%) and SPH (0.011%) was observed in cultivar AL at 80 °C.

There is increasing trends for SA and V values with increase in hydration temperature as depicted by regression equations (Supplementary) in comparison of control treatment. Increase in SA and V might be attributed to absorption of water by grain and thus, increasing the thickness of paddy, thereby, increasing SA and V.

L depicted positive correlation with SA (r = 0.682, p ≤ 0.01). T and SA depicted positive correlation with V (r = 0.480, p ≤ 0.05, r = 0.920, p ≤ 0.01), respectively. Similar results were reported by Kale et al (2017).

SI increased for paddy after hydration and the increase was linear with the increase in hydration temperature, indicative of occurrence of some degree of gelatinization during hydration at higher temperatures. The maximum % increase for SI (0.131%) was observed in cultivar AL at 80 °C.

The average performance of soaked samples revealed upward trend for De, Dg, Da, SPH and Ds with increase in hydration temperature in comparison to control (Table 3). This positive relation can be well established by the regression equations (Supplementary). At 80 °C, AL recorded maximum % increase for SA (0.131%), Da (0.331%) and Ds (0.053%), while, PD18 recorded maximum % increase for V (0.226%), De (0.069%) and Dg (0.071%). Variation in these properties could be attributed to moisture gain during hydration as starch granules swell after absorption of water, in addition to, filling and consequent widening of cracks present in grain during hydration (Ahromrit et al. 2006).

Table 3.

Effect of hydration treatment on geometrical properties of paddy

| Cultivar | Hyd. Tret. | SA (mm2) | V (mm3) | De (mm) | Dg (mm) | Da (mm) | Ds (mm) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1509 | Con | 54.88 ± 0.31 | 38.65 ± 0.39 | 4.20 ± 0.01 | 4.19 ± 0.02 | 6.19 ± 0.01 | 4.81 ± 0.02 | – |

| 70 °C | 57.46 ± 0.06 | 41.64 ± 0.18 | 4.32 ± 0.01 | 4.32 ± 0.01 | 6.23 ± 0.01 | 4.89 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 58.07 ± 0.43 | 43.06 ± 0.59 | 4.35 ± 0.02 | 4.35 ± 0.02 | 6.23 ± 0.01 | 4.95 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | |

| 80 °C | 58.88 ± 0.02 | 43.84 ± 0.40 | 4.39 ± 0.01 | 4.39 ± 0.01 | 6.24 ± 0.01 | 4.98 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |

| PB1718 | Con | 57.80 ± 0.35 | 43.70 ± 0.45 | 4.37 ± 0.02 | 4.37 ± 0.02 | 6.12 ± 0.01 | 4.93 ± 0.02 | – |

| 70 °C | 59.65 ± 0.07 | 46.77 ± 0.06 | 4.47 ± 0.01 | 4.46 ± 0.00 | 6.14 ± 0.01 | 5.02 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 60.98 ± 0.08 | 48.66 ± 0.07 | 4.53 ± 0.01 | 4.52 ± 0.00 | 6.17 ± 0.00 | 5.07 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | |

| 80 °C | 61.99 ± 0.40 | 50.17 ± 0.59 | 4.58 ± 0.02 | 4.57 ± 0.02 | 6.18 ± 0.01 | 5.11 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |

| PS17 | Con | 55.61 ± 0.40 | 41.38 ± 0.48 | 4.29 ± 0.02 | 4.27 ± 0.02 | 6.08 ± 0.01 | 4.86 ± 0.02 | – |

| 70 °C | 58.38 ± 0.25 | 45.28 ± 0.33 | 4.42 ± 0.02 | 4.41 ± 0.01 | 6.09 ± 0.01 | 4.97 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 58.99 ± 0.24 | 46.31 ± 0.33 | 4.46 ± 0.01 | 4.44 ± 0.01 | 6.10 ± 0.01 | 4.99 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 59.97 ± 0.24 | 47.71 ± 0.34 | 4.50 ± 0.02 | 4.48 ± 0.01 | 6.12 ± 0.01 | 5.03 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |

| PD18 | Con | 45.15 ± 0.22 | 31.65 ± 0.27 | 3.93 ± 0.01 | 3.92 ± 0.01 | 5.22 ± 0.01 | 4.36 ± 0.01 | – |

| 70 °C | 48.69 ± 0.26 | 36.47 ± 0.33 | 4.11 ± 0.01 | 4.11 ± 0.01 | 5.28 ± 0.01 | 4.52 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | |

| 75 °C | 49.43 ± 0.26 | 37.56 ± 0.32 | 4.16 ± 0.02 | 4.15 ± 0.01 | 5.29 ± 0.01 | 4.55 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | |

| 80 °C | 50.40 ± 0.48 | 38.81 ± 0.63 | 4.20 ± 0.02 | 4.20 ± 0.02 | 5.33 ± 0.02 | 4.59 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | |

| KJ | Con | 39.15 ± 0.14 | 27.38 ± 0.15 | 3.74 ± 0.00 | 3.73 ± 0.01 | 4.60 ± 0.01 | 4.05 ± 0.01 | – |

| 70 °C | 40.40 ± 0.24 | 29.36 ± 0.29 | 3.83 ± 0.01 | 3.81 ± 0.01 | 4.62 ± 0.01 | 4.11 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | |

| 75 °C | 40.94 ± 0.30 | 30.05 ± 0.36 | 3.86 ± 0.02 | 3.84 ± 0.02 | 4.63 ± 0.01 | 4.14 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 41.04 ± 0.17 | 30.24 ± 0.18 | 3.87 ± 0.01 | 3.85 ± 0.01 | 4.62 ± 0.01 | 4.14 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | |

| AL | Con | 49.75 ± 0.11 | 42.87 ± 0.08 | 4.34 ± 0.01 | 4.32 ± 0.00 | 4.80 ± 0.01 | 4.52 ± 0.01 | – |

| 70 °C | 52.11 ± 0.73 | 46.23 ± 0.92 | 4.44 ± 0.02 | 4.43 ± 0.03 | 4.84 ± 0.04 | 4.61 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | |

| 75 °C | 54.78 ± 0.21 | 49.78 ± 0.28 | 4.56 ± 0.01 | 4.55 ± 0.01 | 4.91 ± 0.01 | 4.71 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | |

| 80 °C | 56.17 ± 0.26 | 43.28 ± 0.56 | 4.62 ± 0.02 | 4.61 ± 0.01 | 4.95 ± 0.01 | 4.95 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | |

| C.D.* | 0.86 | 1.17 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| SE (m) | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| SE (d) | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| C.V. | 0.99 | 1.73 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 12.78 | |

SA: Surface area, V: Volume, EMD: Equivalent mean diameter, GMD: Geometric mean diameter, AAD: Arithmetic mean diameter, SMD: Square mean diameter, SI: Swelling index, Con: Control. Mean ± SE. *5% level of probability

Due to hydration treatment, BD, TD, TrD and porosity increased, which might be attributed to lesser increase in volume to the corresponding increase in grain weight because of moisture increase (Kale et al. 2015). HR and CI decreased after the hydration treatment (Table 4). The maximum % increase was recorded for BD (0.137%), TD (0.101%), and TrD (0.144%) in KJ; and for porosity (0.071%) in PB1509 at 75 °C. Minimum % decrease for CI (-0.092) was observed in PS17 at 70 °C.

Table 4.

Effect of hydration treatment on gravimetric properties of paddy

| Cultivar | Hyd. Tret. | BD (kg/m3) | TD (kg/m3) | TrD (kg/m3) | CI | HR | Porosity (%) | TKW (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1509 | Con | 447.97 ± 13.86 | 520.84 ± 10.32 | 1116.49 ± 9.44 | 14.03 ± 0.97 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 53.36 ± 0.58 | 31.25 ± 0.32 |

| 70 °C | 467.92 ± 10.37 | 528.90 ± 9.41 | 1225.09 ± 14.83 | 11.54 ± 0.39 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 56.83 ± 0.31 | 32.85 ± 0.11 | |

| 75 °C | 485.89 ± 9.73 | 536.72 ± 7.38 | 1251.98 ± 17.25 | 9.49 ± 0.59 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 57.13 ± 0.20 | 32.89 ± 0.12 | |

| 80 °C | 501.40 ± 7.57 | 545.40 ± 14.04 | 1262.12 ± 11.54 | 8.01 ± 1.16 | 1.09 ± 0.01 | 57.13 ± 0.71 | 32.98 ± 0.14 | |

| PB1718 | Con | 458.55 ± 9.71 | 528.73 ± 14.45 | 1123.77 ± 11.00 | 13.24 ± 0.82 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 52.97 ± 0.85 | 29.84 ± 0.34 |

| 70 °C | 472.11 ± 8.10 | 539.72 ± 11.40 | 1162.17 ± 11.84 | 12.50 ± 0.97 | 1.14 ± 0.01 | 53.57 ± 0.52 | 30.22 ± 0.26 | |

| 75 °C | 491.33 ± 11.92 | 548.92 ± 9.21 | 1210.11 ± 9.32 | 10.51 ± 0.92 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | 54.65 ± 0.42 | 30.46 ± 0.15 | |

| 80 °C | 515.22 ± 17.88 | 575.87 ± 11.96 | 1270.36 ± 15.36 | 10.58 ± 1.53 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | 54.68 ± 0.45 | 30.85 ± 0.09 | |

| PS17 | Con | 470.57 ± 13.88 | 554.55 ± 11.65 | 1205.80 ± 8.75 | 15.17 ± 0.79 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 54.02 ± 0.68 | 24.38 ± 0.13 |

| 70 °C | 489.13 ± 14.36 | 575.41 ± 10.66 | 1284.09 ± 4.64 | 15.03 ± 0.96 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 55.19 ± 0.76 | 25.82 ± 0.15 | |

| 75 °C | 502.17 ± 11.06 | 590.03 ± 11.85 | 1319.98 ± 7.66 | 14.89 ± 0.41 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 55.31 ± 0.68 | 26.51 ± 0.12 | |

| 80 °C | 522.94 ± 11.32 | 607.84 ± 12.04 | 1369.00 ± 14.27 | 13.97 ± 0.27 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 55.61 ± 0.50 | 27.88 ± 0.14 | |

| PD18 | Con | 518.71 ± 9.16 | 606.82 ± 13.33 | 1253.03 ± 9.82 | 14.50 ± 0.46 | 1.17 ± 0.01 | 51.57 ± 0.70 | 28.10 ± 0.08 |

| 70 °C | 531.35 ± 11.26 | 610.02 ± 7.07 | 1259.60 ± 13.29 | 12.92 ± 0.84 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 51.69 ± 0.05 | 29.38 ± 0.10 | |

| 75 °C | 537.27 ± 9.50 | 615.80 ± 8.90 | 1266.84 ± 12.36 | 12.73 ± 1.64 | 1.15 ± 0.02 | 51.78 ± 0.52 | 30.22 ± 0.24 | |

| 80 °C | 550.07 ± 11.58 | 620.44 ± 11.84 | 1272.58 ± 11.44 | 11.35 ± 0.37 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 52.01 ± 0.53 | 30.44 ± 0.21 | |

| KJ | Con | 518.11 ± 14.54 | 592.72 ± 11.70 | 1187.30 ± 7.29 | 12.62 ± 0.77 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 50.08 ± 0.69 | 16.70 ± 0.17 |

| 70 °C | 535.78 ± 14.99 | 612.10 ± 11.92 | 1263.06 ± 11.57 | 12.49 ± 0.96 | 1.14 ± 0.01 | 51.54 ± 0.57 | 16.96 ± 0.13 | |

| 75 °C | 561.97 ± 11.85 | 633.92 ± 10.71 | 1311.82 ± 11.00 | 11.36 ± 0.40 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 51.68 ± 0.41 | 17.18 ± 0.14 | |

| 80 °C | 589.01 ± 9.24 | 652.34 ± 10.78 | 1358.34 ± 8.66 | 9.71 ± 0.28 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 51.98 ± 0.50 | 17.24 ± 0.19 | |

| AL | Con | 558.80 ± 14.75 | 629.90 ± 13.35 | 1284.22 ± 9.04 | 11.31 ± 0.47 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 50.95 ± 0.72 | 22.27 ± 0.11 |

| 70 °C | 582.90 ± 6.27 | 645.50 ± 11.62 | 1372.12 ± 11.54 | 9.67 ± 0.77 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 52.25 ± 0.03 | 22.76 ± 0.13 | |

| 75 °C | 593.26 ± 11.18 | 651.10 ± 11.53 | 1380.24 ± 6.86 | 8.89 ± 0.13 | 1.10 ± 0.01 | 52.66 ± 0.57 | 23.10 ± 0.15 | |

| 80 °C | 609.13 ± 10.02 | 666.00 ± 9.45 | 1391.20 ± 11.50 | 8.52 ± 1.55 | 1.10 ± 0.02 | 52.81 ± 0.50 | 23.30 ± 0.16 | |

| C.D.* | 33.45 | 32.10 | 31.98 | 2.48 | 0.04 | 1.59 | 0.31 | |

| SE (m) | 11.73 | 11.26 | 11.21 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.11 | |

| SE (d) | 16.59 | 15.92 | 15.86 | 1.23 | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.15 | |

| C.V. | 3.90 | 3.30 | 1.53 | 12.67 | 1.96 | 1.80 | 0.70 | |

BD: Bulk density, TD: tapped density, TrD: true density, CI: Carr’s index, HR: Hausner ratio, TKW: thousand kernel weight, Con: control. Mean ± SE. *5% level of probability

BD, TD, TrD depicted linear relationship with hydration temperature (Supplementary). BD depicted positive correlation with TD, TrD (r = 0.958 and 0.840, p ≤ 0.01), respectively, and TD and TrD showed positive correlation (r = 0.814, p ≤ 0.05). BD, TD and TrD were positively correlated among themselves and thus, increase in one was linked with increase in other. The results are consistent with the findings of Kale et al (2017).

BD, TD and TrD depicted positive correlation with B (r = 0.751, 0.700 and 0.662, p ≤ 0.01), T (r = 0.654, 0.520 and 0.587, p ≤ 0.01), SPH (r = 0.884, 0.836 and 0.644, p ≤ 0.01), AR (r = 0.875, 0.833 and 0.651, p ≤ 0.01), while negative correlation with L (r = − 0.895, − 0.897 and − 0.569, p ≤ 0.01) and L/B (r = − 0.913, − 0.911 and − 0.654, p ≤ 0.01), respectively. Negative correlation of BD with L/B ratio is indicative that long slender grains exhibited lower density characteristics. This was also earlier reported (Sharma et al. 2022, 2023). BD and TD depicted negative correlation with SA (r = − 0.453, p ≤ 0.05 and r = − 0.543, p ≤ 0.01), respectively. Porosity exhibited positive correlation with L, L/B, SA and V (r = 0.761, 0.677, 0.779 and 0.598 respectively, p ≤ 0.01) and negative correlation with SPH and AR (r = − 0.553 and − 0.538, p ≤ 0.01), respectively.

TKW increased linearly with increase in hydration temperature. Increase in TKW might be because of the fact that air voids in rice kernels have been filled with water. Maximum % increase was observed for TKW (0.144%) in cultivar PS17 at 80 °C. TKW exhibited positive correlation with L, L/B, SA, V and porosity (r = 0.768, 0.734, 0.735, 0.544 and 0.637, p ≤ 0.01) while negative correlation with B, SPH, AR, BD and TD (r = − 0.422, − 0.603, − 0.619, − 0.587 and − 0.659, p ≤ 0.01), respectively.

After hydration, linear increase in AOR with increasing hydration temperature was observed and supported by regression analysis (Supplementary). The increasing hydration temperature affected AOR positively and the maximum increase was observed in KJ (0.204%) at 80 °C.

Higher COF was observed for hydrated samples in comparison to control (Supplementary). In general, COF-G had highest value followed by COF-PW and COF-SS. The COF was affected positively with the increase in the hydration temperature. The increase in COF may be due to the increase in adhesion forces between grains and material surface, and also between grains with increase in the moisture content. Due to increase in moisture content grains may have rough surface so there is increase in COF.

Effect of hydration on milling properties

Economically, the milled rice quality is of chief significance given that grain size and shape, intensity of color and cleanliness are strongly associated with transaction price of the rice, while the presence of broken grains reduce the market value of rice. The efficient milling industries generally produce better quality rice, whereas inefficient milling industries waste energy resulting in losses. In these conditions, the higher HRY and lower broken proportion are of significance. Among the control, different cultivars exhibited wide range of values for these attributes. Hulling % varied from 74.40 (AL) to 81.40% (KJ), milling % ranged from 62.00 (PB1509) to 73.36% (KJ), HRY % ranged from 41.75 (PB1509) to 55.75% (KJ), and broken % varied from 12.13 (PS17) to 20.25% (KJ). Hull % and bran % varied from 18.00–23.58% to 5.14–13.45%, respectively, in control.

Substantial increase in hulling and milling yield were observed after the hydration treatment. Hydration treatment improved hulling % and made dehusking process easier. HRY increased effectively after hydration treatment which might be attributed to loosening of the husk and hardening of the rice kernel (Mohapatra and Bal 2006) or because of partial gelatinization of starch at high hydration temperatures, thus, increasing the grain hardness which led to higher HRY values (Kale et al. 2017). Gelatinization brought about stronger structures together and denaturation of protein occurred by defusing into the inter-granular space of starch. This increased the binding effect and proved to be beneficial for the milling process. Increasing the grain moisture content more than 30% w.b. during hydration leads to proper starch gelatinization, besides healing the cracks and fissures present in rice grains. This increases HRY during milling (Kale et al. 2017). In our study, optimum hydration was achieved by hydration of grains until it achieved CMC. However, increasing beyond this CMC could have led to rupturing of husk, severe deformation of grain, grain gets cooked and leaching out of contents took place. After the drying operation, such hollow grains become shorter and easily break during milling (Ayamdoo et al. 2013), which was prevented by determination of optimum moisture content, i.e., CMC for termination of hydration.

HRY varied from 41.75 to 55.75% among control, and this increase varied from 50.75 to 65.86% after the hydration treatment. Among the control treatment, maximum HRY was observed in KJ (55.75%) while minimum in PB1509 (41.75%). After the hydration treatment, maximum improvement in HRY was observed in cultivar PS17 (25.88%), followed by PB1509 (20.39%) and KJ (19.53%).

Among control treatments, maximum and minimum broken % was observed in PB1509 and KJ, respectively. Broken % followed the reverse trend after hydration treatment. Control treatments showed higher % broken grains, which decreased after hydration treatment. Hydration treatment proved to be most effective in improving the HRY in case of long grain cultivars PB1509 and PS17, which were having very low HRY in unsoaked or control samples. The improvement in HRY % varied from 1.79 to 32.93%, while, reduction in broken % ranged from − 51.13 to − 4.85%. Maximum improvement for HRY and maximum reduction in broken % were found at 80 °C for all the cultivars. HRY exhibited positive correlation with V (r = 0.419, p ≤ 0.05) and TrD (r = 0.583, p ≤ 0.01). The susceptibility of rice grain breakage during milling operation is majorly affected by rice kernel fissures, chalkiness, immaturity and dimensions, which are dependent on cultivar. It has also been reported that the parboiling treatment to each cultivar of rice was different and hence difference in their milling properties (Buggenhout et al. 2013).

A wide variation among cultivars could be observed in the milling property; as cultivars behaved differently, uniform hydration temperature was not established in our study. Although, KJ depicted highest HRY and PB1509 depicted lowest HRY amongst control samples, it is significant to note the increased HRY of PB1509 over KJ (Table 5). A linear relationship between HRY and hydration temperature was observed as supported by regression equation (Supplementary), and the increase in hydration temperature increased the HRY.

Table 5.

Effect of Hydration on milling quality, grain hardness and color properties of rice

| Cultivar | Hyd. Tret. | Hulling % | Milling % | HRY % | Broken % | Hardness (N) | L* | a* | b* | WI | Delta E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1509 | Con | 76.63 ± 0.30 | 62.00 ± 0.49 | 41.75 ± 0.51 | 20.25 ± 0.17 | 6.62 ± 0.24 | 58.61 ± 0.08 | − 0.44 ± 0.15 | 7.71 ± 0.01 | 57.90 ± 0.08 | |

| 70 °C | 79.75 ± 0.24 | 65.75 ± 0.41 | 50.75 ± 0.58 | 15.00 ± 0.91 | 18.02 ± 0.13 | 50.45 ± 0.13 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 12.77 ± 0.01 | 48.83 ± 0.12 | 9.65 ± 0.04 | |

| 75 °C | 80.15 ± 0.17 | 65.50 ± 1.48 | 55.50 ± 0.47 | 10.00 ± 0.49 | 20.91 ± 0.20 | 50.31 ± 0.17 | 0.52 ± 0.08 | 12.85 ± 0.08 | 48.67 ± 0.14 | 9.81 ± 0.06 | |

| 80 °C | 76.65 ± 0.22 | 64.50 ± 0.21 | 50.94 ± 0.54 | 7.56 ± 0.31 | 26.15 ± 0.13 | 50.23 ± 0.12 | 0.57 ± 0.18 | 13.58 ± 0.34 | 48.41 ± 0.03 | 10.29 ± 0.15 | |

| PB1718 | Con | 74.90 ± 0.26 | 67.28 ± 0.66 | 55.00 ± 0.49 | 14.28 ± 0.26 | 12.37 ± 0.17 | 52.55 ± 0.17 | 0.51 ± 0.15 | 13.41 ± 0.14 | 50.69 ± 0.13 | |

| 70 °C | 78.80 ± 0.11 | 71.33 ± 0.66 | 58.33 ± 0.44 | 13.00 ± 0.29 | 16.21 ± 0.10 | 49.30 ± 0.10 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 13.58 ± 0.17 | 47.51 ± 0.05 | 3.26 ± 0.08 | |

| 75 °C | 79.09 ± 0.12 | 71.93 ± 0.54 | 63.66 ± 0.55 | 8.27 ± 0.36 | 18.95 ± 0.07 | 48.39 ± 0.13 | 0.59 ± 0.08 | 14.03 ± 0.09 | 46.51 ± 0.14 | 4.22 ± 0.04 | |

| 80 °C | 77.55 ± 0.35 | 71.28 ± 0.40 | 60.06 ± 0.28 | 6.83 ± 0.13 | 24.48 ± 0.17 | 48.13 ± 0.13 | 0.61 ± 0.18 | 14.36 ± 0.13 | 46.18 ± 0.09 | 4.52 ± 0.07 | |

| PS17 | Con | 77.66 ± 0.30 | 67.95 ± 0.58 | 55.95 ± 0.34 | 12.13 ± 0.26 | 8.73 ± 0.11 | 57.66 ± 0.14 | − 0.24 ± 0.15 | 10.37 ± 0.21 | 56.41 ± 0.13 | |

| 70 °C | 77.67 ± 0.16 | 68.59 ± 0.67 | 62.00 ± 0.20 | 6.59 ± 0.45 | 18.29 ± 0.13 | 50.18 ± 0.16 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 13.15 ± 0.07 | 48.46 ± 0.14 | 8.08 ± 0.08 | |

| 75 °C | 79.73 ± 0.35 | 71.81 ± 0.12 | 65.86 ± 1.06 | 5.95 ± 0.49 | 23.12 ± 0.13 | 49.86 ± 0.18 | 1.12 ± 0.08 | 13.78 ± 0.21 | 47.99 ± 0.13 | 8.62 ± 0.04 | |

| 80 °C | 78.67 ± 0.36 | 71.62 ± 0.21 | 62.80 ± 0.35 | 5.65 ± 0.20 | 24.47 ± 0.17 | 49.21 ± 0.08 | 1.30 ± 0.18 | 14.01 ± 0.10 | 47.30 ± 0.05 | 9.33 ± 0.12 | |

| PD18 | Con | 77.00 ± 0.26 | 63.50 ± 0.29 | 41.75 ± 0.31 | 16.25 ± 0.43 | 10.10 ± 0.12 | 56.42 ± 0.11 | − 0.64 ± 0.15 | 9.41 ± 0.14 | 55.41 ± 0.08 | |

| 70 °C | 77.70 ± 0.39 | 67.15 ± 0.43 | 55.04 ± 0.62 | 11.75 ± 0.58 | 18.46 ± 0.12 | 53.29 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 11.15 ± 0.08 | 51.97 ± 0.05 | 3.82 ± 0.03 | |

| 75 °C | 78.00 ± 0.14 | 66.35 ± 0.59 | 56.55 ± 0.77 | 9.80 ± 0.10 | 23.16 ± 0.11 | 53.40 ± 0.10 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 11.66 ± 0.15 | 51.96 ± 0.08 | 4.00 ± 0.07 | |

| 80 °C | 78.40 ± 0.16 | 67.75 ± 0.69 | 56.75 ± 0.61 | 9.00 ± 0.50 | 27.04 ± 0.10 | 53.16 ± 0.16 | 0.78 ± 0.18 | 12.17 ± 0.10 | 51.60 ± 0.13 | 4.50 ± 0.06 | |

| KJ | Con | 81.40 ± 0.15 | 73.36 ± 0.35 | 55.75 ± 0.14 | 22.50 ± 1.32 | 8.76 ± 0.16 | 58.92 ± 0.20 | − 0.67 ± 0.15 | 9.40 ± 0.08 | 57.85 ± 0.18 | |

| 70 °C | 81.50 ± 0.15 | 76.36 ± 0.32 | 56.75 ± 0.11 | 20.21 ± 0.26 | 19.30 ± 0.13 | 56.94 ± 0.27 | 0.76 ± 0.05 | 10.18 ± 0.09 | 55.75 ± 0.24 | 2.57 ± 0.05 | |

| 75 °C | 85.66 ± 0.37 | 74.33 ± 0.48 | 57.33 ± 0.28 | 17.64 ± 0.64 | 24.57 ± 0.19 | 55.21 ± 0.21 | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 11.32 ± 0.18 | 53.79 ± 0.16 | 4.44 ± 0.04 | |

| 80 °C | 81.50 ± 0.25 | 76.36 ± 0.62 | 61.75 ± 0.06 | 15.82 ± 0.61 | 29.57 ± 0.20 | 54.80 ± 0.09 | 0.87 ± 0.18 | 11.41 ± 0.23 | 53.37 ± 0.04 | 4.84 ± 0.16 | |

| AL | Con | 74.40 ± 0.23 | 66.86 ± 0.59 | 51.13 ± 0.04 | 14.84 ± 0.49 | 6.47 ± 0.16 | 50.19 ± 0.14 | 1.98 ± 0.15 | 14.25 ± 0.11 | 48.15 ± 0.12 | |

| 70 °C | 74.86 ± 0.27 | 68.00 ± 0.52 | 60.00 ± 0.66 | 10.43 ± 2.30 | 19.12 ± 0.11 | 46.75 ± 0.22 | 2.09 ± 0.05 | 17.150.15 | 44.02 ± 0.17 | 4.50 ± 0.12 | |

| 75 °C | 74.65 ± 0.18 | 68.14 ± 0.58 | 60.07 ± 0.03 | 8.07 ± 0.19 | 26.87 ± 0.17 | 45.18 ± 0.16 | 2.62 ± 0.08 | 18.09 ± 0.14 | 42.21 ± 0.11 | 6.35 ± 0.05 | |

| 80 °C | 75.50 ± 0.19 | 69.31 ± 0.28 | 62.16 ± 0.49 | 7.56 ± 0.07 | 30.97 ± 0.13 | 45.02 ± 0.11 | 2.87 ± 0.18 | 18.20 ± 0.18 | 42.01 ± 0.05 | 6.57 ± 0.11 | |

| C.D.* | 0.72 | 1.62 | 1.37 | 1.93 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.25 | |

| SE (m) | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.09 | |

| SE (d) | 0.36 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.96 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.12 | |

| C.V | 0.56 | 1.43 | 1.47 | 9.72 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 2.02 | 1.25 | 1.33 | 2.42 | |

HRY: Head rice yield; L*: Lightness; a*: Redness-greenness; b*: Yellowness-blueness; WI: Whiteness, Con: Control. Mean ± SE. *5% level of probability

Buggenhout et al. (2013) pointed out that parboiling conditions could result in either increased or decreased HRY. In addition, during hydration, moisture content gradient can exist inside the rice grain. Without equilibration, moisture content at the center may be too low for the starch in the center of rice grain to gelatinize at the processing temperatures. This can lead to creation of white bellies, which are breakage susceptible. Therefore, it was ensured that each cultivar achieved desired CMC before termination of the hydration process.

Effect of hydration on color characteristics of rice

Among control samples, AL depicted lowest L* (50.19) and highest a* (1.98) and b* (14.25) values. Highest L* values were observed for KJ (58.92), and lowest a* and b* values were observed for PS17 (− 0.24) and PB1509 (7.71). WI varied from 48.15 for AL to 57.90 for PB1509. For consumers, grain color is an important consideration, as they prefer white colored rice more. Grain color was significantly affected by hydration treatment. L* values decreased after hydration treatment, however, a* and b* values increased. In general, higher hydration temperatures imparted darker color to grain. Lower L* were observed at 80 °C. a* increased with hydration temperature which could be attributed to non- enzymatic browning triggered by the hydrothermal treatment (Bello et al. 2007). Grey color rice falls in grade three quality category while rice with white, yellow or light cream color are of premium quality. The color of rice that is parboiled may vary from white to yellow on the basis of processing variables such as hydration water temperature, duration of hydration, heating temperature, etc. (Sivakamasundari et al. 2020). Minimum decrease was observed at 70 °C for L* (1.742%) in PB1509 and for WI (− 0.036%) in KJ. The cultivar AL showed maximum % increase at 80 °C for a*.

Change in total color (ΔE) value varied from 2.57 to 10.29. ΔE increased with increase in hydration temperature. This might be attributed to the non-enzymatic browning of rice and diffusion of color pigments from hull and bran layers to the rice kernel (Dutta and Mahanta 2012). The maximum value for ΔE was observed in PB1509 at 80 °C.

Effect of hydration on grain hardness

GH, an important quality parameter, is found to be associated with HRY and cooking quality of the milled rice. Amongst control, lowest (6.47 N) and highest (12.37 N) GH were observed in cultivars AL and PB1718, respectively. Hydrated rice showed higher hardness as compared to control. GH increased linearly with increase in hydration temperature, regardless of cultivar. Higher temperature of hydration treatment imparted more hardness to rice grains, which can also be observed from regression equations (Supplementary). This increase could be attributed to the partial gelatinization of starch (Kale et al. 2017) or swelling of starch, which led to healing of the cracks, reducing the chalkiness, thereby improving the hardness of the rice grain (Mir and Bosco 2013). Amongst cultivars, AL recorded maximum average % increase (3.787%) at 80 °C. Hardness is known to be negatively associated with kernel breakage during milling. GH depicted positive significant correlation with HRY (r = 0.684, p ≤ 0.01) and negative significant correlation with broken % (r = − 0.580, p ≤ 0.01), thus, more the hardness more will be HRY and lesser will be proportion of broken grains.

Optimum hydration treatment

A hydration treatment, which brings about minimal changes to grain color and improves HRY, should be the optimum treatment (Kale et al. 2017). From the results, it can be established that all the cultivars had high hardness values and thus high HRY at higher temperatures. However, higher temperature (80 °C) affected other quality characteristics of rice negatively. Moreover, at lower temperatures (70 °C), lesser than desired improvement in HRY was observed. Assessing the behavior of cultivars on the hydration process gives interesting differences. The long slender cultivars are aromatic cultivars; PB1509 and PB1718 (basmati) while, PS17 (non-basmati) cultivar. Subjecting these cultivars to high temperatures causes adverse effects on the flavor characteristics because of which these cultivars hold a unique status in the commercial market. Earlier, researchers (Kale et al. 2015; Chavan et al. 2017) who have worked on basmati rice parboiling have stated that the increment in the HRY and nutritional values compensated such losses. However, severity of process utilized for parboiling can be optimized in such a way, which resulted into minimal losses in quality profile with maximum improvement in milling efficiency and HRY. Keeping these objectives in mind, a lower hydration temperature of 75 °C emerged as optimum for hydration treatment of cultivars PB1509, PB1718 and PS17. Among medium grained cultivars, although both KJ and AL are aromatic (non-basmati), however, they are generally consumed in the eastern and north- eastern states (Pillaiyar 1990) wherein most of the cultivars are subjected to parboiling treatment. In these cultivars, higher hydration temperature of 80 °C emerged as optimum temperature for hydration. Besides, in our study, medium cultivars (PD18, KJ, AL) took longer hydration duration at lower temperatures, which itself is undesirable on a commercial scale. Therefore, hydration at higher temperature suits well for these cultivars on a larger scale.

Conclusion

In the present study, optimization of hydration process variables like hydration temperature and duration was carried out based on kinetic studies and their effect on the quality characteristic of rice. Both PM and SKM fitted well to the hydration process, however, PM was found more suited in our studies because of higher R2 and lower Chi-square and RMSE values. Hydration treatment significantly affected the quality characteristics of rice. Effect of hydration treatment on axial dimensions, geometric, gravimetric and mechanical properties was well established in our studies. Milling efficiency significantly improved after hydration treatment as compared to control, and a linear increase was observed among each cultivar with increase in hydration temperature. Variation among cultivars led to differences in selection of optimized hydration treatment. For long slender aromatic (basmati and non- basmati) cultivars, a low hydration temperature was found suitable that brought about higher HRY with minimal negative alterations to quality characteristics of rice. For medium grains, higher temperature was found suitable because of their long hydration duration, which in turn causes decrease in the process efficiency in terms of energy consumption. In conclusion, optimized treatment for long slender grains (PB1509, PB1718 and KJ) was observed as 75 °C, while for medium grained cultivars (PD18, KJ and AL), it was observed as 80 °C, based on improvement in hardness, milling efficiency, HRY, color and textural attributes. Further analysis of rice quality characteristics such as cooking qualities, nutritional properties, pasting properties, etc. are required to establish optimized hydration process variables.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table 1 Physico-chemical variation in the cultivars understudy. Table 2 Regression equation and coefficient of determination as a function of temperature. Figure 1 Effect of hydration treatment on Angle of Repose (AOR) and Coefficient of Friction for plywood (COF-PW), stainless steel (SS) and glass (COF-G) for all paddy cultivars (DOCX 93 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Director, Defence Food Research Laboratory (DFRL), Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO), Mysore, India for providing us with all facilities and financial assistance to carry out the research work.

Author contributions

SS conceived, carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript; ADS provided guidance, supervised the work, and edited the manuscript; TGR assisted during the experimentation; DDW provided the resources and facilities.

Funding

Defence Food Research Laboratory, DRDO, Mysore.

Data availability

Supplementary material.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The research has been conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. The submitted work is original and has not been published elsewhere. The manuscript shall not be submitted to any other Journal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahromrit A, Ledward DA, Niranjan K (2006) High pressure induced water uptake characteristics of Thai glutinous rice. J Food Eng 72(3):225–233 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.11.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh MR (2011) Effect of paddy husked ratio on rice breakage and whiteness during milling process. Aust J Crop Sci 5(5):562–565 [Google Scholar]

- AOAC Official Method 930.15 (2005) Official methods of analysis of AOAC international, 18th edn. AOAC International, Gaithersburg

- Aruva S, Dutta S, Moses JA (2020) Empirical characterization of hydration behavior of Indian paddy varieties by physicochemical characterization and kinetic studies. J Food Sci 85(10):3303–3312 10.1111/1750-3841.15441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayamdoo JA, Demuyakor B, Dogbe W, Owusu R (2013) Parboiling of paddy rice, the science and perceptions of it as practiced in Northern Ghana. Int J Sci Technol Res 2(4):13–18 [Google Scholar]

- Azuka CE, Nkama I, Asoiro FU (2021) Physical properties of parboiled milled local rice varieties marketed in South-East Nigeria. J Food Sci Technol 58:1788–1796 10.1007/s13197-020-04690-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbinoti TCV, de Matos Jorge LM, Jorge RMM (2018) Modeling the hydration step of the rice (Oryza sativa) parboiling process. J Food Eng 216:81–89 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bello MO, Tolaba MP, Suarez C (2007) Water absorption and starch gelatinization in whole rice grain during soaking. LWT-Food Sci Technol 40(2):313–318 10.1016/j.lwt.2005.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buggenhout J, Brijs K, Celus I, Delcour JA (2013) The breakage susceptibility of raw and parboiled rice: a review. J Food Eng 117(3):304–315 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan P, Sharma SR, Mittal TC, Mahajan G, Gupta SK (2017) Optimization of parboiling parameters to improve the quality characteristics of Pusa Basmati 1509. J Food Process Eng 40(3):e12454 10.1111/jfpe.12454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta H, Mahanta CL (2012) Effect of hydrothermal treatment varying in time and pressure on the properties of parboiled rices with different amylose content. Food Res Int 49(2):655–663 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.09.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Fawal YA, Tawfik MA, El Shal AM (2009) Study on physical and engineering properties for grains of some field crops. Misr J Agric Eng 26(4):1933–1951 10.21608/mjae.2009.107579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav ML, Din M, Nandede BM, Kumar M (2020) Engineering properties of paddy and wheat seeds in context to design of pneumatic metering devices. J Inst Eng India Ser A 101:281–292 10.1007/s40030-019-00430-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji-u P, Inprasit C (2019) Effect of soaking conditions on properties of Khao Dawk Mali 105. Agric Nat Resour 53(4):378–385 [Google Scholar]

- Kale SJ, Jha SK, Jha GK, Samuel DVK (2013) Evaluation and modeling of water absorption characteristics of paddy. J Agric Eng 50(3):29–38 [Google Scholar]

- Kale SJ, Jha SK, Jha GK, Sinha JP, Lal SB (2015) Soaking induced changes in chemical composition, glycemic index and starch characteristics of basmati rice. Rice Sci 22(5):227–236 10.1016/j.rsci.2015.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kale SJ, Jha SK, Nath P (2017) Soaking effects on physical characteristics of basmati (Pusa Basmati 1121) rice. Agric Eng Int 19(4):114–123 [Google Scholar]

- Kar N, Jain RK, Srivastav PP (1999) Parboiling of dehusked rice. J Food Eng 39(1):17–22 10.1016/S0260-8774(98)00138-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meera K, Smita M, Haripriya S (2019) Varietal distinctness in physical and engineering properties of paddy and brown rice from southern India. J Food Sci Technol 56(3):1473–1483 10.1007/s13197-019-03631-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihretu MA, Tolesa GN, Abera S (2023) Parboiling to improve milling quality of Selam rice variety, grown in Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric 9(1):2258775. 10.1080/23311932.2023.2258775 10.1080/23311932.2023.2258775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mir SA, Bosco SJD (2013) Effect of soaking temperature on physical and functional properties of parboiled rice cultivars grown in temperate region of India. Food Nutr Sci 4(03):282–288 [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra D, Bal S (2006) Cooking quality and instrumental textural attributes of cooked rice for different milling fractions. J Food Eng 73(3):253–259 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.01.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panda BK, Shrivastava SL (2019) Microwave assisted rapid hydration in starch matrix of paddy (Oryza sativa L.): process development, characterization, and comparison with conventional practice. Food Hydrocoll 92:240–249 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.01.066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg M (1988) An empirical model for the description of moisture sorption curves. J Food Sci 53:1216–1217 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1988.tb13565.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar P (1990) Rice parboiling research in India. Cereal Foods World (USA) 35(2):225–227 [Google Scholar]

- Priya KS, Dharani A, Kumar NG, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C (2019) Computational modelling of hydration kinetics of paddy. J Agric Eng 56(4):269–275 [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Semwal AD, Srihari SP, Govindraj T, Wadikar DD (2022) Impact of physico-chemical variation in different rice cultivars and freezing pretreatment for retaining better rehydration characteristics of instant rice. Int J Trop Agric 40(1–2):71–84 [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Semwal AD, Srihari SP, Govind Raj T, Wadikar D (2023) Effect of salt pretreatments on physico-chemical, cooking and rehydration kinetics of instant rice. J Food Sci Technol. 10.1007/s13197-023-05877-y 10.1007/s13197-023-05877-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran OP, Tonk DS, Kaushik LS, Hasija RC, Pannu RS (1998) Statistical software package for agricultural research workers. In: Hooda DS, Hasija RC (eds) Recent advances in information theory, statistics and computer applications. Department of Mathematics Statistics, CCS HAU, Hisar, pp 139–143 [Google Scholar]

- Singh BPN, Kulshrestha SP (1987) Kinetics of water adsorption by soybean and pigeonpea grains. J Food Sci 52(6):1538–1541 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1987.tb05874.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, Vishwanathan KH (2010) Hydration behaviour of food grains and modelling their moisture pick up as per Peleg’s equation: Part II. Legumes. J Food Sci Technol 47:42–46 10.1007/s13197-010-0013-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakamasundari SK, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C (2020) Effect of parboiling methods on the physicochemical characteristics and glycemic index of rice varieties. J Food Meas Charact 14:3122–3137 10.1007/s11694-020-00551-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varnamkhasti MG, Mobli H, Jafari A, Keyhani AR, Soltanabadi MH, Rafiee S, Kheiralipour K (2008) Some physical properties of rough rice (Oryza sativa L.) grain. J Cereal Sci 47(3):496–501 10.1016/j.jcs.2007.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1 Physico-chemical variation in the cultivars understudy. Table 2 Regression equation and coefficient of determination as a function of temperature. Figure 1 Effect of hydration treatment on Angle of Repose (AOR) and Coefficient of Friction for plywood (COF-PW), stainless steel (SS) and glass (COF-G) for all paddy cultivars (DOCX 93 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary material.