ABSTRACT

Airway microbiota are known to contribute to lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis (CF), but their contributions to pathogenesis are still unclear. To improve our understanding of host-microbe interactions, we have developed an integrated analytical and bioinformatic mass spectrometry (MS)-based metaproteomics workflow to analyze clinical bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from people with airway disease. Proteins from BAL cellular pellets were processed and pooled together in groups categorized by disease status (CF vs. non-CF) and bacterial diversity, based on previously performed small subunit rRNA sequencing data. Proteins from each pooled sample group were digested and subjected to liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). MS/MS spectra were matched to human and bacterial peptide sequences leveraging a bioinformatic workflow using a metagenomics-guided protein sequence database and rigorous evaluation. Label-free quantification revealed differentially abundant human peptides from proteins with known roles in CF, like neutrophil elastase and collagenase, and proteins with lesser-known roles in CF, including apolipoproteins. Differentially abundant bacterial peptides were identified from known CF pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas), as well as other taxa with potentially novel roles in CF. We used this host-microbe peptide panel for targeted parallel-reaction monitoring validation, demonstrating for the first time an MS-based assay effective for quantifying host-microbe protein dynamics within BAL cells from individual CF patients. Our integrated bioinformatic and analytical workflow combining discovery, verification, and validation should prove useful for diverse studies to characterize microbial contributors in airway diseases. Furthermore, we describe a promising preliminary panel of differentially abundant microbe and host peptide sequences for further study as potential markers of host-microbe relationships in CF disease pathogenesis.

IMPORTANCE

Identifying microbial pathogenic contributors and dysregulated human responses in airway disease, such as CF, is critical to understanding disease progression and developing more effective treatments. To this end, characterizing the proteins expressed from bacterial microbes and human host cells during disease progression can provide valuable new insights. We describe here a new method to confidently detect and monitor abundance changes of both microbe and host proteins from challenging BAL samples commonly collected from CF patients. Our method uses both state-of-the art mass spectrometry-based instrumentation to detect proteins present in these samples and customized bioinformatic software tools to analyze the data and characterize detected proteins and their association with CF. We demonstrate the use of this method to characterize microbe and host proteins from individual BAL samples, paving the way for a new approach to understand molecular contributors to CF and other diseases of the airway.

KEYWORDS: microbiome, cystic fibrosis, host-pathogen interactions, metaproteomics, metagenomics, bioinformatics, mass spectrometry, bronchoalveolar lavage, airway, lung infection

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis pathogenesis and microbial contributions

Cystic fibrosis (CF) disease is characterized by airway obstruction, microbial infection, and inflammation (1). These factors contribute to morbidity and early mortality in those afflicted with this disease. As a consequence of impaired mucus clearance in the lower airway, bacterial infection by organisms is prominent in CF. Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Fusobacteria constitute the majority of the CF airway microbiota (2). Within these bacterial classes, genera such as Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, and Burkholderia, as well as others, comprise the CF airway microbiome (1, 3–8). The composition of the microbiome is known to change with age and disease progression (9–12). Molecular analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), a sample collected using flexible bronchoscopy in a sedated individual from the lower airway, has provided new clues into the dynamics of microbial infections, their interactions with host cells contributing to CF lung disease pathogenesis, and potential targets for therapeutics (3).

Understanding the role of microbiota in airway conditions such as CF

In order to characterize the microorganisms from samples such as BAL that might play a role in diseases such as CF, metagenomic approaches have been commonly used (13), including small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU-rRNA) gene sequencing for classifying the bacterial taxa present in the sample (14–16). Although metagenomics provides highly valuable information on the bacterial composition of clinical samples (17–19), even the most advanced metagenome sequencing methods (20) only provide predictions of the potential functional molecules (proteins) expressed by the microbiota (21). Mass spectrometry (MS)-based metaproteomics offers a means to detect and quantify the proteins expressed by complex microbiota, thereby revealing functional markers of translationally active microbes present in the samples while simultaneously connecting their expression to specific bacterial taxa (22, 23). As such, when coupled with metagenomic information to define the organisms (and expressed proteomes) present, metaproteomics offers a powerful, complementary approach to fully characterizing bacterial communities within complex clinical samples (24–26). MS-based proteomic analysis of clinical samples such as BAL also offers the possibility of characterizing the response of the human proteins in parallel to those expressed by the microbiota, providing unique information on potential mechanisms of microbe-host interactions (27, 28).

Challenges of metaproteomics in BAL

Despite its value, MS-based metaproteomics faces challenges to its effectiveness when analyzing complex biological samples, particularly those derived from human clinical specimens such as BAL. A main challenge is the low biomass of microorganisms relative to the human host, which leads to challenges detecting microbial peptides compared to the more prominent human peptides when analyzing tryptic peptide mixtures by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (29, 30). Adding to this challenge, generation of peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) to microbial sequences necessitates matching MS/MS spectra to extremely large databases comprising all proteomes of microbiota present in the sample, which increases potential for false positives and decreases sensitivity (31–33). Finally, assigning function and taxonomy to the identified peptide sequences can be a challenge due to conservation of protein sequences across taxa and lack of confident annotation of encoded proteins (34). Many of these challenges can be addressed using specialized metaproteomic bioinformatic tools (35–38). The upshot of successful metaproteomic analysis is the generation of unique information on proteins expressed by translationally active bacteria, along with a profile of human host proteins, within clinically important samples. Not surprisingly, metaproteomics has shown value in studying the role of microorganisms in CF airways in recent years (3, 39).

Applying an advanced MS-metaproteomics workflow to BAL samples to study microbe-host dynamics in CF

We describe a novel workflow utilizing metaproteomics in BAL CF samples and demonstrate its effectiveness in characterizing microbial and human proteins compared between CF and disease control (DC) patients with non-CF airway conditions. This advanced workflow is composed of these steps: (i) deep quantitative MS-based metaproteomics analysis of pooled BAL protein samples classified by disease status and SSU-rRNA-derived bacterial diversity; (ii) customized metaproteomic bioinformatic analysis to identify, verify, and quantify peptides from microbial proteins across pooled samples, as well as identify differentially abundant human proteins corresponding to disease status; (iii) prioritization of microbial and human peptide candidates to develop a panel for targeted MS-based assays using parallel-reaction monitoring (PRM) in individual patient BAL samples; and (iv) PRM analysis to quantify and determine differential abundance of microbial and host peptides between CF and DC samples, generating a promising and unique microbe-host peptide panel for future investigation in larger patient cohorts.

We demonstrate the effectiveness of this workflow and, in doing so, highlight a number of novel aspects: (i) demonstrating for the first time an end-to-end analytical and bioinformatic workflow for the joint analysis of microbial and human peptides in challenging BAL samples; (ii) a first-of-its-kind demonstration of PRM analysis to validate differential abundance of microbe-host peptide targets in individual CF or DC BAL samples; and (iii) a promising preliminary panel of microbe-host peptides, derived from some bacteria and human proteins with known associations to CF, as well as a number of novel proteins with new possible roles in pathogenesis. We provide all necessary information for others to utilize this peptide panel in their work studying progression and/or treatment of CF in clinical BAL samples, as well as an in-depth description of the workflow to enable its application to other clinical studies of microbe-host relationships in airway disease.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Samples and initial taxonomic profiling

Clinical BAL sample cohort

The clinical BAL sample cohort included 67 samples from individuals with CF and 115 from people without CF but having other non-CF respiratory diseases and serving as DC samples. All BAL samples were collected for clinical purposes, and additional BAL available after all clinically indicated tests had been run was saved for research purposes. BAL samples were stored at −80°C until shipment to the University of Minnesota for analysis. See Data S1 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s1) for details on all relevant information about these samples, which were collected using institutional review board-approved protocols for the protection of human subjects.

SSU-rRNA data generation

The SSU-rRNA data acquired from the sample cohort were previously published (40) and utilized in this experiment. Briefly, an approximately 315-nucleotide sequence encompassing the V1/V2 region of the rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using indexed primers (40). Unique sequences were assigned taxonomic identification using SILVA Incremental Aligner (41, 42). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were generated by adding all counts with the same taxonomic identity. Based on the OTUs identified, the Shannon Diversity Index, a measure of microbiome diversity (43, 44), was calculated for each of the 116 samples with sufficient bacterial load and used as a criterion for selection of samples used in this experiment (see Fig. S1).

Mass spectrometry-based metaproteomics discovery analysis

Materials

Urea lysis buffer was made using LC-MS grade materials by combining 7-M urea (Invitrogen, cat. # 15505035), 2-M thiourea (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # T8656), 400-mM tris at pH 8 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. # 17926), 10-mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (Stem, cat. # 5090110492), 40-mM 2-chloroacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # 22790), and 20% acetonitrile (AcN) (OmniSolv, cat. # AX0156). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Lonza BioWhittaker, cat. # 17517Q) was diluted to 1× with H2O (OmniSolv, cat. # WX0001). Trypsin (Promega, cat. # V5280) was resuspended to 0.025 μg/μL using 10-mM CaCl2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. # AA3568504) in H2O.

Preparation of BAL cell pellets from individual samples

BAL samples were thawed and spun at 4,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatants were removed. The pellets were rinsed twice with cold PBS, centrifuging and removing the supernatant each time. Freshly made urea-based lysis buffer was added to the pellets, which were vortexed, and set on ice for 5 min. The pellets were probe sonicated for 7 s to break up DNA and subjected to 60 repetitions of 35,000 PSI for 20 s then 0 psi at 37°C. Protein amounts for each sample were quantified with Precision Red Advanced Protein Assay reagent (Cytoskeleton Inc., cat. # ADV02).

Selection of patient samples for pooling

With the goal of generating an initial, deep profile of detectable proteins from BAL samples, pooled patient samples were generated in order to increase the amount of starting protein available for in-depth analysis. Samples were selected for pooling by first grouping by clinical diagnosis (CF or DC), further sorting based on their Shannon diversity index values and assigned ranks of high or low overall relative biodiversity. Microbial diversity ranking information was applied in the generation of pooled samples to reflect possible protein profile differences in disease progression influenced by the microbiome present. Using a total of 64 individual samples, samples from each of the CF and DC groups were selected to represent both the highest and lowest Shannon index values for four unique and separate pooled groups: cystic fibrosis-high diversity (CF-HD, n = 16), cystic fibrosis-low diversity (CF-LD, n = 16), disease control-high diversity (DC-HD, n = 16), disease control-low diversity (DC-LD, n = 16). For the purposes of this study, categorizing the sample pools based on their Shannon index was done with the objective of obtaining a deep profile of proteins present in either the CF or DC patient groups, rather than drawing conclusions about differences corresponding to bacterial diversity between these groups. The sample selection process can be seen in Fig. S1. Data S1 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s1) shows all clinical information related to the samples selected for pooling, and a summary of the details can be found in Table S1.

Pooling of samples

Each pooled sample group (CF-HD, CF-LD, DC-HD, and DC-LD) was composed of 2.5 μg of total protein from each of the 16 samples within the group mixed together. Each pooled mixture was brought to equal volume of urea lysis buffer and diluted by 4× volumes of H2O. The samples were digested with a 1:40 trypsin-to-sample mass ratio at 37°C overnight. The samples were cleaned with mixed-mode cation exchange (MCX) stage tips packed with styrenedivinylbenzene-reverse phase sulfonate (Empore, cat. # 2241) extraction disks. Using centrifugation at 500 × g after each step, the tips were conditioned and equilibrated with AcN and H2O with 0.2% formic acid (FA) (at pH 2–3), respectively, and the samples reconstituted with H2O with 0.2% FA were dispensed onto the tip assembly. The samples, now bound within the stage tips, were washed with 95.0/5.0/0.2 H2O/AcN/FA, washed with 100% AcN, and eluted for collection using 40:55:5 AcN:H2O:NH4OH. Peptide amounts were measured with a Pierce Quantitative Colorimetric Peptide Assay kit (cat. # 23275).

High pH offline reverse-phase liquid chromatography

Each pooled sample was reconstituted in 50 μL of 50 mM ammonium formate and injected separately for fractionation by high-pH Shimadzu offline reverse-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) using a 90-min gradient, 200 μL/min, with a fraction collected every 2 min (45). Thirty-two fractions were collected for each pooled sample, and 15-mAU-equivalent aliquots were concatenated into 10 tubes to mix early, middle, and late timepoints of the gradient fractionation. The concatenated samples were cleaned with MCX stage tips and dried with a speed vacuum.

LC-MS/MS analysis

The concatenated fractions were reconstituted in 97.9:2.0:0.1, H2O:ACN:FA load solvent, and direct injections of ~400 ng of each fraction were analyzed by nanocapillary LC-MS with a Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano system online with an Orbitrap Eclipse mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility (FAIMS) separation. Gradient separation on a self-packed C18 column (Dr. Maisch GmbH ReproSil-PUR 1.9-μm 120-Å C18aq, 100-μm ID × 40-cm length) at 55°C with the following profile using 0.1% FA in H2O (A) and 0.1% FA in ACN (B): 5% B solvent from 0 to 2 min, 8% B at 2.5 min, 21% B at 135 min, 34% B at 180 min and 90% B at 182 min with a flow rate of 325 nL/min from 0 to 2 min and 315 nL/min from 2.5 to 180 min. The FAIMS nitrogen cooling gas setting was 5.0 L/min; the carrier gas was 4.6 L/min; and the inner and outer electrodes were set to 100°C. Compensation voltages (CVs) were scanned at −45, −60, and −75 for 1 s each with a data-dependent acquisition method. The following MS parameters were used: electrospray ionization (ESI) voltage +2.1 kV, ion transfer tube 275°C; no internal calibration; Orbitrap MS1 scan 120K resolution in profile mode from 400 to 1,400 mass-to-charge (m/z) with 50-ms injection time; 100% (4 × 10E5) automatic gain control (AGC); higher-energy collisional dissociation MS2 activation was triggered on precursors with two to six charges above 2.5E4 counts; monoisotopic peak determination was set to peptide; MS2 settings (all CVs) were 1.6-Da quadrupole isolation window, 30% fixed collision energy, Orbitrap detection with 30K resolution at 200 m/z, first mass fixed at 110 m/z, 54-ms maximum injection time, 100% (5 × 10E4) AGC, 45-s dynamic exclusion duration with ±10-ppm mass tolerance; and exclusion lists were shared among CVs. See details in “Data Availability” for accessing raw MS files within the ProteomeXchange PRIDE repository.

Custom protein sequence database generation

To create a customized protein sequence database, microbial genera determined by SSU-rRNA sequencing data were used, only considering the top 99% relatively abundant in each of the samples used to create the pooled samples. Using software tools available in the Galaxy for Proteomics (Galaxy-P) tool suite (46), the tabular files were used as input for importing corresponding proteome sequences and merging these together with the human UniProt proteome sequence (2021–12-10, 101,014 protein sequences) along with common contaminants (116 sequences). This created a sequence database for each of the pooled samples containing these numbers of distinct sequences: CF-HD, 18,474,828; CF-LD, 7,219,650; DC-HD, 26,029,550; and DC-LD, 16,067,437. The MS raw files were first searched against this large protein sequence database using MetaNovo (47) (Galaxy v.0.1.1). PSMs generated were used to extract the parent protein sequences from the original database and generate a reduced database containing 238,382 total human and bacterial protein sequences. Files used throughout the process to generate the reduced database can be found in this link: https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-discoveryreduceddatabasegeneration.

Sequence database searching, peptide verification, and quantification

PSMs and inferred proteins were generated using complementary sequence database searching programs to maximize the number of confident matches to microbial sequences. The Fragpipe suite of tools (48–50) (v. 17.1) including IonQuant (51) (v.1.8.10) for label-free quantification (LFQ) of peptides, MSBooster (52) with Percolator (53) to improve peptide identification, MaxQuant (54) (v.2.0.3.0) and the MaxLFQ (55), and SearchGUI/PeptideShaker (56, 57) coupled with FlashLFQ (58). SearchGUI utilized three separate sequence database searching algorithms (MS-GF+ v.1.1.0, Comet v.2018.01 rev. 3, and X!Tandem v.2015.12.145.1) with the outputs from these algorithms serving as input to PeptideShaker for aggregation, scoring, and statistical filtering. In all cases, scoring thresholds for PSMs from all different algorithms used were set to 1% false discovery rate. Outputs for FragPipe and MaxQuant can be found in the Galaxy-P histories (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-discovery-fragpipe and https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-discovery-maxquant, respectively, and https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-discovery-searchgui--peptideshaker and https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-flashlfq-quantification for SearchGUI/PeptideShaker/FlashLFQ). A summary of parameters used is noted in Table S3.

Verification of candidate microbial peptide sequences

Matches to microbial sequences across the three programs were combined together for further verification using the PepQuery tool (59), which further evaluates the quality of PSMs to putative microbial proteins by testing these against sequences in the reference human proteome, considering possibilities such as PTMs and single amino acid substitutions to reference sequences as potential better matches to MS/MS compared to the initial microbial sequence match. Those MS/MS spectra that do not show a better match to the reference sequences were also reevaluated against their original microbial sequence and assigned a score, P value, and given a “yes” or “no” for overall confidence based on these criteria. The usage of the PepQuery tool, including input and output files, can be viewed at https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-pepquery-validation. Those microbial peptide sequences passing this verification step and assigned a yes for confidence were quantified between the four pooled sample groups using the MaxQuant, IonQuant, and FlashLFQ (Galaxy v.1.0.3.1) programs for intensity-based label-free quantification to determine those showing differential abundance between DC and CF sample pools. Based on the consistency of fold changes among CF and DC samples and PepQuery verification results, we selected 87 microbial peptides for further interrogation. Microbial peptides and their parent proteins were further annotated for taxonomy and function (if known) using BLAST-P to confirm their mapping to bacterial proteins and the Unipept (60) (Galaxy v.4.5.1) and MetaTryp tools (61). Quantification and detailed characterization of microbial peptides can be found in Data S3 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s3).

For analysis of human proteins, PSMs and inferred proteins from the FragPipe pipeline were quantified by normalized spectral counting in order to determine proteins showing potential differential abundance between sample groups (Data S2, https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cfdata-file-s2). Total spectral counts for each protein were divided by the total PSMs within the sample and multiplied by 106 to generate a quantitative value for each protein in each of the four pooled samples. Values from the high or low diversity pools were combined for the CF and DC pools, respectively. Fold changes for CF:DC were calculated for each protein; those proteins with a normalized quantitative value of at least 100 in either the CF or DC samples and a fold change of at least twofold in either direction were further considered for analysis. These proteins were inputted into the STRING-database (db) resource (62) to characterize enriched functional networks. Networks were visualized within STRING using the built-in network visualization functions. From this analysis, proteins belonging to enriched functional networks, along with the 10 proteins with the highest fold changes measured between the CF and DC groups, were further considered for targeted validation in individual patient samples.

Targeted parallel-reaction monitoring mass spectrometry

Selection of peptide targets

From the microbial peptides and human proteins quantified in the discovery workflow described above, peptide targets were selected for validation using targeted parallel-reaction monitoring (63, 64). Quantified microbial peptides were manually curated, selecting those with strong signal-to-noise for MS1 and MS/MS signals, visually confirmed quality MS/MS matches to the verified peptide sequences, and fold-change differences between CF and DC pools of at least twofold. For human proteins, peptides were manually selected from proteins spanning the enriched functional networks determined by STRING, based on MS/MS signal strength, with no trypsin miscleavage, and minimizing amino acid sequences that might become modified (oxidation of methionines and alkylation of cysteines).

Targeted analysis of peptide targets in individual BAL samples

BAL samples from five individual people with CF and five DC were selected for demonstrating targeted validation of the selected microbial and human peptides. These individual samples were selected from the samples used to create the pooled samples in the discovery analysis. A summary of the individuals’ clinical details can be found in Table S2 and extra information at https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s1. A total of 87 microbial peptides and 106 human peptides, selected as described above, were initially used to create an inclusion list for an initial analysis of a pool of peptides created from combining the CF and DC individual samples (10 total pooled together). Using this inclusion list, we analyzed the pooled sample by LC-MS/MS in order to first confirm identification of these peptides within the sample pool and to establish retention times for the detected peptides.

For this inclusion list-based analysis, we performed analytical separation and detection on an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) interfaced to an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Dried peptide samples were reconstituted using a load solvent mixture of 97.9:2:0.1, H2O:AcN:FA. Peptide mixture (400 ng) in 4 µL was injected on the analytical platform equipped with a 10-µL injection loop. Chromatographic separation was performed using a self-packed C18 column (Dr. Maisch GmbH ReproSil-PUR 1.9-µm 120-Å C18aq, 100-µm ID × 45-cm length) maintained at 55°C for the duration of the experiment. The liquid chromatography (LC) solvents were 0.1% FA in H2O (A) and 0.1% FA in AcN (B) solutions. Chromatographic separation was performed using a linear gradient as follows: 5% B solvent from 0 to 2 min, 8% B at 2.5 min, 21% B at 30 min, 35% B at 45 min, and 90% B from 47 to 55 min followed by a return to starting conditions. The flow rate was operated at 400 nL/min for 0–2 min, 315 nL/min for 2.5–45.0 min, and 400 nL/min for 47–55 min. A Nanospray Flex ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used with a source voltage of 2.1 kV and ion transfer tube temperature of 250°C. Results from this analysis were manually reviewed using Skyline (65), selecting only peptides with at least three co-eluting transition peaks with no interfering, non-aligned transition signals; a Skyline dot product of at least 0.2 was required as an additional metric. Ultimately, a total of 133 peptides from both microbial and human proteins were confirmed using the inclusion list analysis in pooled samples and passed on for PRM analysis in individual samples.

After confirming the detection and relative LC retention time of microbial and human peptides, targeted LC-MS/MS analyses were performed by PRM analysis on the same Orbitrap Fusion system. Retention time-based scheduling of MS/MS generation by PRM was accomplished using Orbitrap MS1 detection at a resolution of 120,000, AGC targeted setting of 4 × 10E5, and a maximum ion injection time of 50 ms. Scan ranges of 380–1,580 m/z were used for full-scan detection. A total of 133 peptide targets were simultaneously monitored via LC-PRM-MS/MS using a 3-min LC retention time scheduling window in a single experiment. MS/MS spectra were acquired with quadrupole isolation of 1.6 m/z, Orbitrap detection at a resolution of 30K and an MS2 AGC of 5 × 10E4, and a 54-ms maximum injection time. The analysis of peptides utilized collision induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation at a constant collision energy of 30%.

Evaluation and curation of PRM results and statistical analysis of relative peptide abundance

Peptides were quantified in Skyline (65), and specificity of MS/MS matches to expected sequences was accomplished by matching PRM-acquired MS/MS to predicted peptide sequence spectral libraries using the Prosit tool (66). PRM results were manually inspected for quality, taking into account dot product values assigned by Prosit within Skyline and only considering those results with at least three co-eluting peptide fragments detected with high-quality signal-to-noise in the reconstructed LC chromatograms at expected retention times and Prosit dot products of at least 0.5. Using standard functions available in Skyline, area under the curve values were calculated for detected fragments and normalized to the total ion current (TIC) corresponding to the sample to generate abundance values for each PRM-detected peptide. For analysis of relative abundance levels between DC and CF groups, statistical calculations using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-tests and data visualization using box-plot graphs were performed within the GraphPad Prism (v.9.5.0) software.

RESULTS

Integrated analytical and bioinformatic workflow for host-microbe protein discovery, verification, and validation

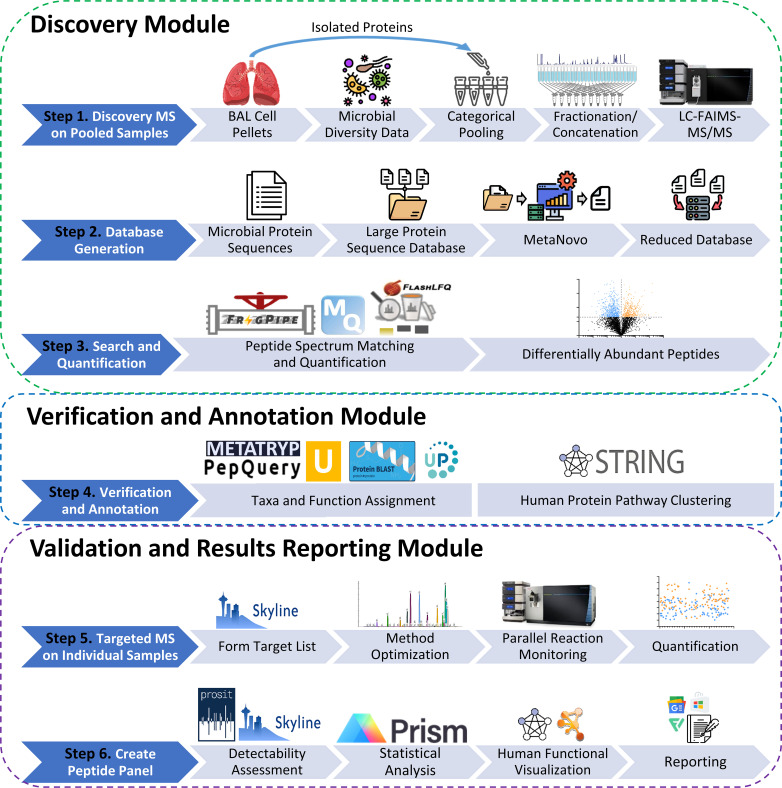

This work is built on a foundational, customized workflow combining instrumental-based analytical methods with bioinformatic tools developed to address challenges of metaproteomic analysis in clinical BAL samples. These challenges include (i) detection and quantification of microbe-expressed proteins, which are relatively low in abundance compared to the human host proteins in BAL; (ii) verification of the accuracy of putative PSMs identifying microbial peptides; and (iii) validation of peptides of highest interest in individual CF BAL samples, ultimately offering a quantitative assay for investigating host-microbe protein dynamics across larger patient cohorts. Our integrated workflow is composed of three main modules (Fig. 1): (i) discovery, (ii) verification and annotation, and (iii) validation and results reporting.

Fig 1.

Overview of the analytical and bioinformatic workflow for discovery (steps 1–3), verification (step 4), and validation (steps 5 and 6) of host-microbe peptide targets from the clinical BAL cellular samples.

Discovery module

The relatively low abundance of bacterial proteins compared to host proteins generally found when working with clinical human samples (67, 68) challenges their detection via MS-based methods. The clinical samples available for this work (Data S1; https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s1) had previously been analyzed by SSU-rRNA sequencing and categorized by bacterial diversity based on assigned Shannon diversity index values. These samples were either derived from CF patients or DC patients, who were diagnosed with non-CF diseases that impact respiratory health, such as interstitial lung disease, asthma/reactive airway disease, and various immunosuppressive disorders. In order to maximize the detection of proteins from BAL samples, four pooled samples were generated, combining equal amounts of proteins from 16 patient samples with either CF or DC diagnoses, and high diversity or low diversity of bacteria as determined by SSU-rRNA data. See Data S1 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s1), for information on samples used for pooling. Our ultimate goal was to demonstrate the effectiveness of our workflow to determine differentially abundant peptides between CF and DC samples, therefore the separation of pooled samples based on bacterial diversity was only done to increase our depth of identification of peptides across CF and DC pools. Each separate pooled sample (CF-HD, CF-LD, DC-HD, DC-LD) was fractionated via semi-preparative high pH RPLC, and these fractions were analyzed by LC-FAIMS-MS/MS, offering acquisition of high-quality peptide MS/MS spectra for sensitive generation of confident PSMs offered by ion filtering from FAIMS.

In order to identify proteins from microbes and host, as well as provide some initial quantitative information on peptide abundance differences between the CF and DC sample pools, the MS/MS data were analyzed using a suite of tools developed for metaproteomic analysis. The taxonomic composition from the SSU-rRNA data was used to generate an initial, large protein sequence database of potentially expressed proteins for each of the pooled samples (average of about 17M sequences, Table 1). The MetaNovo (47) software was used to initially match MS/MS to the corresponding database for each pooled sample. PSMs generated by MetaNovo from each pool were used to build a reduced, composite database composed of 238,382 bacterial protein sequences containing the identified peptides.

TABLE 1.

Summary of results generated by discovery and verification modulesa

| Metaproteomic sequence database generation | Database | Number of protein sequences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSU-rRNA-guided initial databases | CF-HD | 18,474,828 | ||

| CF-LD | 7,219,650 | |||

| DC-HD | 26,029,550 | |||

| DC-LD | 16,067,437 | |||

| Reduced, combined database after MetaNovo | 238,382 | |||

CF-HD, cystic fibrosis-high diversity; CF-LD, cystic fibrosis-low diversity; DC-HD, disease control-high diversity; DC-LD, disease control-low diversity.

To maximize PSMs from bacterial sequences, we utilized several sequence database-searching platforms (SearchGUI/PeptideShaker, MaxQuant, and Fragpipe), matching MS/MS data against the sequence database of the bacterial protein sequences appended to UniProt human protein sequences. These three algorithms produced complementary results (Table S4; Fig. S2) identifying 2,292 unique bacterial peptide sequences of high quality based on the database searching scoring assignments from the different algorithms and controlling for PSM false discovery rate (estimated at 1% using target-decoy methods (69). For label-free quantification of microbial peptides, the FlashLFQ tool (58, 70) was used for SeachGUI/PeptideShaker results; MaxLFQ (55) was used for MaxQuant results and IonQuant (51) within FragPipe, as seen in Data S3 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s3). For human proteins, the results from Fragpipe were used, along with normalized spectral counting to quantify proteins showing abundance differences between the CF and DC samples analyzed.

Verification and annotation module

This module focused on verifying identified bacterial peptides from the discovery module and prioritizing their value as candidates for further validation based on abundance comparisons between CF and DC sample pools. The PepQuery software (59) was used as a means to independently verify the most confident PSMs to bacterial sequences, using its well-described routine for testing the quality of putative PSMs against other possible alternatives, such as matches to human sequences, including those carrying post-translational modifications. Those peptides passing the stringent PepQuery verification were further annotated by taxonomy using the Unipept tool (71) and BLAST-P to confirm their matching to bacterial proteins. Finally, those bacterial peptides showing potential differential abundance based on intensity-based LFQ values compared between the pooled CF and DC samples were further considered, resulting in 87 bacterial peptides of highest interest for advancement to the third analysis module (Data S3, https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s3).

The human proteins quantified via normalized spectral counting were also further annotated functionally, with an aim of prioritizing potential pathways or functional networks enriched in abundance between the pooled DC and CF samples. For this, only proteins identified with at least 100 normalized spectral counts in at least one of the pooled samples were considered, and only those with twofold or greater abundance differences between combined CF and DC sample pools. Proteins passing these criteria were inputted into the STRING-db bioinformatics resource (62), which provided an analysis of enriched subnetworks of functionally or physically interacting proteins. The interacting proteins composing these subnetworks, along with the top 10 most differentially abundant proteins in CF or DC, which did not fall into these networks, were retained as candidates for further validation in the next module. The Galaxy-P history (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cfdata-file-s2) provides information on these prioritized human proteins.

Validation and results reporting module

The verified and quantified bacterial and human peptides of highest interest were advanced on to a final analysis module, focused on developing PRM methods targeting these peptides. The goal of this analysis was primarily to demonstrate the effectiveness of PRM to validate abundance levels of bacterial and human peptides of interest in individual patient BAL samples. This work would also deliver a preliminary panel of host-microbe peptides, validated in a small number of individual samples, useful for future studies of CF. To demonstrate this technology validation approach, five individual CF samples and five individual DC samples were selected from the samples used for the discovery module, digesting these proteins with trypsin and preparing them for PRM analysis. A pool of peptides from these 10 samples was initially analyzed by LC-MS/MS using an inclusion list of m/z values of bacterial and human peptides to verify the detection of these peptides and establish LC retention times for developing a scheduled PRM analysis. These data provided the necessary information to develop a scheduled PRM method for analysis of the individual CF or DC samples.

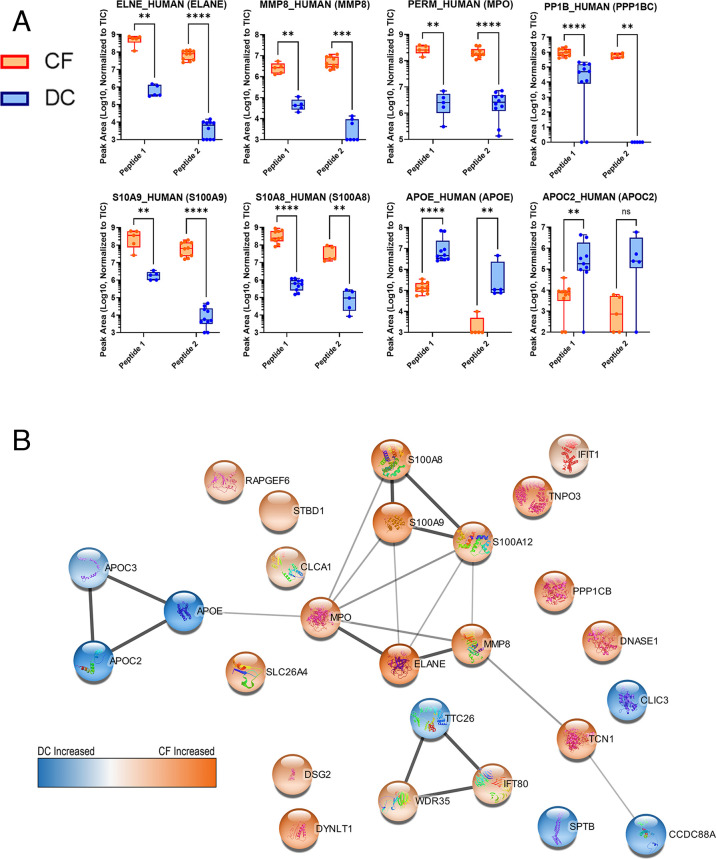

The PRM results were analyzed via the Skyline software. We utilized the Prosit resource (66) for predicting MS/MS fragmentation patterns of our bacterial or human peptides of interest, using this as a spectral library to evaluate the quality of detection of peptides using Skyline (65). Skyline mapped PRM data to expected fragmentation patterns, assigning Prosit-calculated dot product confidence scores and offering a means for visualizing the quality of results in individual samples. The abundance of detected peptides was measured using area under the curve calculations and normalization to the TIC for each run through Skyline. The TIC values can be found in Table S5, and chromatograms for CF and DC samples are displayed in Fig. S3 and S4, respectively. Differential abundance between CF and DC patients of quantified peptides was determined via statistical analysis. Human and microbial peptides passing quality criteria thresholds from Skyline analysis, along with normalized abundance values and associated details, are viewable in Data S4 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s4-1) and Data S5 (https://usegalaxy.eu/u/galaxyp/h/cf-data-file-s5-2), respectively. Detected peaks used for quantitation and associated numerical data for each detected peptide can be viewed using the information in our ProteomeXchange PRIDE repository (see “Data Availability”), which includes a comparison of detected microbial and human peptides and proteins in 10 individual samples analyzed with PRM (Table S6). Figure 2A shows a selection of differentially abundant peptides derived from human proteins measured between CF and DC samples, as well as functional networks corresponding to these proteins as determined by STRING-db (Fig. 2B). Figure 3 shows a selection of differentially abundant peptides derived from bacterial proteins measured between CF and DC samples. In both Fig. 2A and 3, the quantified PRM-detected peptides had passed our stringent manual quality curation and had maximum dot products of at least 0.5 in the patient sample group (CF or DC), where they were detected with increased abundance, consistent with other studies using PRM for peptide validation (72). Figure. S5 and S6 show human and microbial peptides, respectively, that either were not differentially abundant, did not pass quality assessment, or both.

Fig 2.

Human peptides detected in individual cystic fibrosis lung disease (n = 5) or disease control (n = 5) BAL samples with a targeted PRM method using a Fusion Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Some peptides were analyzed in a second technical PRM replicate analysis which included a modified list of target peptides. (a) Differentially abundant human proteins each represented by two unique peptides quantified using abundances normalized to the TIC of the corresponding sample. Results analyzed using Mann-Whitney U-tests. ns = P > 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. (b) Enriched functional networks of proteins with differentially abundant peptides. Thicker lines indicate higher confidence in network connectivity determined by STRING-db. The color scale visualizes the relative abundances. ns, not significant.

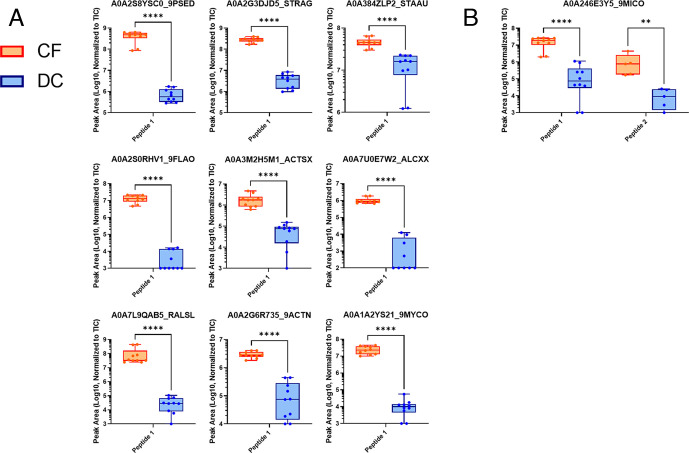

Fig 3.

Differentially abundant microbial peptides detected in individual cystic fibrosis lung disease (n = 5) or disease control (n = 5) BAL samples with a targeted PRM method using a Fusion Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Some peptides were analyzed in a second technical PRM replicate analysis which included a modified list of target peptides. Abundance values of (a) one or (b) two peptides were normalized to the TIC of the corresponding sample. Results were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U-tests. **P ≤ 0.01, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

The bacterial and human peptides validated by PRM analysis provide a unique panel of rigorously characterized peptides. Table 2 provides a summary of all of the peptide targets shown in the plots in Fig. 2 and 3. The table shows the necessary information to develop targeted methods quantifying these peptides in MS-based assays seeking to understand host and microbe dynamics in clinical samples. In addition to those results shown in Fig. 2A and 3, we also quantified a number of microbial and human peptides with strong PRM signals but lower dot products. These are shown in Table S7.

TABLE 2.

Summary of host-microbe peptide panel verified and quantified using PRM analysisd

| Peptide sequence | UniProt protein accession number (gene name) | Taxonomy assignmenta | Functional assignmentb | m/z | RT | dotPc | PRM-detected transitions | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NWIDSIIQR | P08246 (ELANE) | Homo sapiens | Neutrophil elastase | 572.809 (2+) |

46.7 | 0.874 | 15 | 0.00794 |

| NANVQVAQLPAQGR | P08246 (ELANE) | Homo sapiens | Neutrophil elastase | 733.397 (2+) | 28.5 | 0.688 | 25 | 0.00001 |

| FQQEHFFHVFSGPR | P22894 (MMP8) | Homo sapiens | Neutrophil collagenase | 441.467 (4+) | 35.8 | 0.603 | 25 | 0.00794 |

| YYAFDLIAQR | P22894 (MMP8) | Homo sapiens | Neutrophil collagenase | 630.325 (2+) | 45.8 | 0.804 | 15 | 0.00010 |

| IANVFTNAFR | P05164-2 (MPO) | Homo sapiens | Myeloperoxidase | 576.812 (2+) | 43.0 | 0.755 | 21 | 0.00794 |

| VVLEGGIDPILR | P05164-2 (MPO) | Homo sapiens | Myeloperoxidase | 640.882 (2+) | 45.3 | 0.692 | 23 | 0.00001 |

| NIETIINTFHQYSVK | P06702 (S100A9) | Homo sapiens | Protein S100-A9 | 602.984 (3+) | 46.2 | 0.650 | 26 | 0.00794 |

| INTFHQYSVK | P06702 (S100A9) | Homo sapiens | Protein S100-A9 | 618.822 (2+) | 23.6 | 0.750 | 19 | 0.00001 |

| ALNSIIDVYHK | P05109 (S100A8) | Homo sapiens | Protein S100-A8 | 424.903 (3+) | 36.0 | 0.647 | 23 | 0.00001 |

| GNFHAVYR | P05109 (S100A8) | Homo sapiens | Protein S100-A8 | 482.243 (2+) | 19.5 | 0.880 | 15 | 0.00794 |

| AHQVVEDGYEFFAKR | P62140 (PPP1CB) | Homo sapiens | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-beta catalytic subunit | 599.297 (3+) |

32.1 | 0.609 | 14 | 0.00001 |

| KYPENFFLLR | P62140 (PPP1CB) | Homo sapiens | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-beta catalytic subunit | 442.912 (3+) |

44.1 | 0.585 | 9 | 0.00794 |

| LAVYQAGAR | P02649 (APOE) | Homo sapiens | Apolipoprotein E | 474.767 (2+) | 24.7 | 0.780 | 15 | 0.00001 |

| QQTEWQSGQR | P02649 (APOE) | Homo sapiens | Apolipoprotein E | 624.292 (2+) | 17.9 | 0.793 | 19 | 0.00794 |

| TAAQNLYEK | P02655 (APOC2) | Homo sapiens | Apolipoprotein C-II | 519.267 (2+) | 20.2 | 0.808 | 12 | 0.00209 |

| TYLPAVDEK | P02655 (APOC2) | Homo sapiens | Apolipoprotein C-II | 518.272 (2+) | 29.9 | 0.760 | 13 | 0.09524 |

| MKIGNLGGAYR | A0A2G3DJD5 (NCTC8181_02460) | Streptococcus agalactiae (a, b) | Plasmid recombination enzyme (d, e) | 598.316 (2+) |

39.4 | 0.631 | 13 | 0.00001 |

| DGFLLDGFPR | A0A2G6R735 (adk) | Unclear | Adenylate kinase (b, c, d, e) | 568.790 (2+) |

49.8 | 0.705 | 15 | 0.00001 |

| AALGAYDLR | A0A1A2YS21 (A5707_08250) | Probable Mycobacterium (a) | Uncharacterized | 475.259 (2+) | 46.8 | 0.670 | 14 | 0.00001 |

| FIVPTDPAK | A0A2S0RHV1 (HYN48_15045) | Flavobacteriaceae (a) | Uncharacterized (e) | 494.279 (2+) |

34.0 | 0.815 | 8 | 0.00001 |

| QAVAGWGGADK | A0A3M2H5M1 (ruvC) | Actinobacteria (a, b) | Crossover junction endodeoxyribonuclease (c, d, e) | 530.265 (2+) |

36.0 | 0.532 | 7 | 0.00001 |

| AYLTTIAK | A0A7U0E7W2 (I6I48_30820) | Proteobacteria (a) | Sigma-70 family RNA polymerase sigma factor (b, e) | 440.761 (2+) |

39.1 | 0.777 | 5 | 0.00002 |

| DWLDSLLQR | A0A2S8YSC0 (CQ065_20345) | Pseudomonas (a, b) | Type II secretion system protein GspF (b, e) | 573.301 (2+) | 46.4 | 0.640 | 14 | 0.00001 |

| LIPNNQGK | A0A7L9QAB5 (HF909_19775) | Proteobacteria (a)/Ralstonia (b) | Glycoside hydrolase family six protein (b, c, d, e) | 442.253 (2+) |

18.6 | 0.870 | 11 | 0.00001 |

| VIPEIDGK | A0A384ZLP2 (gap) | Unclear | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (b, c , d, e) | 435.750 (2+) | 29.4 | 0.760 | 10 | 0.00001 |

| LESGGGLVQPGGSLR | A0A246E3Y5 (CBF90_16015) | Homo sapiens (b) | Immunoglobulin variable region (b) | 713.886 (2+) | 31.3 | 0.628 | 18 | 0.00794 |

| SSASTKGPSVFPLAPSSK | A0A246E3Y5 (CBF90_16015) | Homo sapiens (b) | Immunoglobulin variable region (b, e) | 583.312 (3+) | 33.3 | 0.790 | 25 | 0.00001 |

Taxonomy was assigned using the (a) Unipept and (b) BLAST-P tools.

Functions were assigned using (c) GO, (d) EC number, and (e) InterPro annotations.

PRM chromatograms were manually verified to ensure acceptable signal-to-noise and intensity of detected transitions for each peptide, with special focus on those peptides shown with a maximum dot product (dotP) value above 0.5 as described in the text.

m/z, mass-to-charge; GspF, general secretion pathway protein F.

The PRM-verified human proteins displaying differential abundance between CF and DC samples fell into several categories. A number of these were part of a network of neutrophil-associated proteins (Fig. 2B; Table 2). Some of these have been well-described proteins related to inflammatory response, known to be increased in abundance in CF (e.g., neutrophil elastase, ELANE; the S100 proteins, neutrophil collagenase, MMP8, and myeloperoxidase [MPO]) (73–75). Some others within this network, such as tyrosine protein kinase (FGR) (76) and serine protease 57 (PRSS57) (77) (see Fig. S5; Table S7), are less well described as markers of CF, although known to be inflammation regulators abundant in neutrophils.

The association of other differentially abundant proteins with CF has not been as well described. Among these, two proteins involved in cell motility and cilia regulation (WD35 and IFT80) showed increased abundances in CF patients, along with the kinase and phosphatase proteins PHKB and PPP1B. A subnetwork of three apolipoproteins (APOE, APOC3, and APOC2) showed decreased abundance in CF compared to DC patients. A number of other proteins were verified as differentially abundant but did not show known interactions with each other when analyzed via the STRING-db knowledge base.

In total, 11 PRM-verified peptides from microbial proteins showed significant differential abundance in CF samples as compared to DC samples (Fig. 3; Table 2). Nine of these microbial peptides mapped to a distinct protein accession number (Fig. 3A), while one protein accession contained two verified peptides mapping to their sequence (Fig. 3B). For taxonomic and functional characterization, we subjected the peptides to BLAST-P analysis, Unipept analysis, and Metatryp analysis. For taxonomy (see Table 2), one peptide was assigned at the species level: Streptococcus agalactiae (A0A2G3DJD5_STRAG); two peptides were assigned at the genus level: Pseudomonas (A0A2S8YSC0_9PSED) and Mycobacterium (A0A1A2YS21_9MYCO). Four peptides were assigned to higher taxonomic levels, while four peptides were uncharacterized at the taxonomic level (see Table 2).

Interestingly, one of the differentially abundant microbial proteins identified by two distinct peptides each (Fig. 3B; Table 2) had ambiguous taxonomic assignment. For these proteins, the PSMs were initially matched to microbial sequences in the FASTA database; however, subsequent taxonomic analysis indicated these sequences also can be found in eukaryotes. For example, peptides initially matched to A0A246E3Y5_9MICO in the sequence database search were assigned to human immunoglobulin after further taxonomic characterization (Table 2).

Functional analysis of the proteins containing the PRM-verified microbial peptide sequences (see Table 2) assigned distinct functions to seven of these proteins. Proteins for two of the detected peptide sequences could not be assigned any function (denoted as “uncharacterized” for the function column in Table 2). This highlights the lack of functional characterization for many proteins of microbial origin commonly encountered in microbiology research (78).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to develop a modular, integrated analytical and bioinformatic workflow to study the dynamic microbe-host relationships in BAL samples, offering a means for new discoveries into this increasingly important aspect of CF pathogenesis (79). Direct detection of the microorganisms via metaproteomics can provide unique insights into the identity of biologically active, co-infecting organisms, as well as their functional state that may be indicative of their interactions with the human host cells. However, in samples commonly collected in the clinic for studying airway disease, such as BAL, characterizing the relatively low abundance of microbial proteins, along with the more prominent human proteins, presents a challenge. Here, we have shown how our modular workflow (80) can overcome these challenges.

The discovery module analyzed proteins extracted from pooled cellular BAL samples, grouped based on SSU-rRNA information for determining bacterial diversity within each patient sample. Our focus on the insoluble cellular pellet fraction of BAL helped overcome the challenge of dynamic range suppression due to high abundance proteins found in BAL fluid (45). The pooled samples were also collected from patients with either clinically diagnosed CF or other respiratory tract conditions which acted as unique DC samples and separated into pools based on bacterial diversity in order to more deeply detect peptides by LC-MS/MS analysis. The taxonomic data from the SSU-rRNA data also provided the construction of an aggregated protein sequence database for each sample pool, albeit very large containing millions of sequences, of potential bacteria-expressed proteins in the samples. Our deep analysis via high resolution MS and customized metaproteomic informatic tools of these four separate pooled samples provided a sensitive profile of the detectable bacterial proteins and human proteins, along with initial measures of their relative abundance levels between the different patient groups.

Notably, our analysis of pooled samples amplified protein signals, such that we were able to select proteins and peptides of interest that were reliably detected across the pooled samples, obviating the need for more complicated quantitative analyses such as imputation of missing values, that is more commonly observed in discovery studies analyzing single patient samples. We also utilized multiple sequence database searching algorithms, which generated complementary results (Fig. S2) and maximized the number of bacterial peptide candidates identified in the discovery module. For the human proteins, our relatively simple design analyzing pooled samples also lent itself to the use of the FragPipe tool suite to infer proteins and quantify using spectral counting. We note that other more sophisticated algorithms for quantifying bottom-up proteomics data, such as linear mixed models (81), could be used in this discovery step. We also utilized customized tools such as Unipept (60, 71) and also BLASTP to annotate the taxonomy and functions of microbe-expressed peptide sequences. Other options for such annotation do exist (82) and could be used for this analysis.

The verification and annotation module provided the next essential steps to ensure confident matches of MS/MS spectra to bacterial peptide sequences. This analysis included a rigorous verification of PSMs to bacterial sequences using the PepQuery tool (59), as well as assignment of these sequences to bacterial taxa and biochemical function, if known. This module also measured relative abundance levels of identified bacterial peptides and human proteins, as a means to further prioritize those features of highest interest for final validation.

The validation and results reporting module utilized PRM analysis, which leveraged the information on detected peptides generated in the discovery phase of the work. The PRM-based detection, coupled with data analysis using the popular Skyline tool (65) and Prosit (66), offered a means to confirm the presence of bacterial and host peptides in individual patient samples and more confidently to quantify their abundance. Although we used a predicted spectral library, use of an empirically generated library from the samples of interest may further increase the quality of the peptide identification and scoring (83, 84). It should be noted that our workflow is amenable to the use of spectral libraries generated using either approach, or even a combination of the two.

Our results demonstrate the effectiveness of our modular workflow for metaproteomic characterization of clinical CF samples, with several notable accomplishments.

First, we were able to confidently identify hundreds of potential bacterial peptides from within BAL cellular samples using our discovery module. The most confident of these peptides were further confirmed via the verification and annotation module, along with measures of their abundance between pooled samples using label-free quantification methods (51, 55, 58, 70).

Notably, we demonstrated, for the first time, the ability of PRM analysis to detect and quantify bacterial and human peptides in individual patient samples. This is a significant finding, opening the way to high-throughput, quantitative assays using targeted MS-based methods to dynamics of microbial protein markers in larger patient cohorts. Moreover, the workflow also provided a deep characterization of human proteins and their relative abundance between sample pools, as well as detection and quantification within individual samples.

Although previous studies have described MS-based proteomic analysis of human (85, 86) or microbial (87, 88) proteins from clinically relevant CF samples, ours is the first to simultaneously characterize microbe and host proteins underlying disease pathogenesis. This should open up new possibilities for studying dynamic interactions between microbes and host that may contribute to pathogenesis. This may include combinatorial statistical methods using a composite panel of microbe and host peptide abundance values to better discriminate clinically distinct patient samples (89), or intentional focus on peptides from proteins derived from pathogenic markers from microbes along with host proteins with immune-response functions to understand dynamics of infection and host defense in disease progression.

Lastly, all of the bioinformatic tools supporting this workflow are publicly available, with many of the workflows used available, complete with analysis settings and parameters, via the Galaxy ecosystem (46, 80). It is our hope that this workflow can be used by others seeking to study CF or other respiratory diseases.

The rigorously characterized panel of peptides from both bacterial and human proteins (Table 2) is also a key deliverable from our study. The information provided on these sequences, as well as demonstration of their detection by PRM in individual samples, should enable their use as markers for targeted MS studies in larger cohorts of samples. Given the focus of our work was to demonstrate the effectiveness of PRM in individual BAL specimens, this panel was technologically validated in a relatively small number of samples and should be seen as a preliminary panel needing further study. It is our hope that these promising peptides can serve as molecular markers for studying diverse questions related to CF, such as disease progression or response to potential therapies.

Utilizing our workflow, we were able to deliver results on human protein abundance differences in both the pooled and individual samples when comparing CF and DC patients. Acknowledging that these findings were validated in a relatively small number of individual patient samples, nevertheless, our results profiling these targets offer some interesting potential. Some of these peptides were derived from proteins with known associations in CF, with others having more novel associations to CF lung disease pathogenesis. A number of neutrophil-expressed proteins were observed with large relative abundance in CF samples, which is unsurprising based on the established enrichment of neutrophils in the inflamed CF airway (90). Accordingly, the neutrophil proteases elastase (ELANE) and collagenase (MMP8) showed highly increased abundance in CF vs. DC patients, consistent with well-established evidence of their prominence in the CF airway (91, 92). PRSS57 (also known as neutrophil protease 4) was also detected with high abundance (albeit with a single peptide; see Fig. S5; Table S7) and enrichment in CF samples in discovery experiments. PRSS57 is a more recently characterized neutrophil protease that recognizes arginines as cleavage sites (93). Our results provide the first evidence that this protease may also contribute to CF.

In addition, other markers of inflammation associated with CF showed expected differential abundance in our studies, including MPO (94) and multiple S100 proteins (95). The heterodimer of the S100A8/A9 proteins, calprotectin, is involved in host response to infection through activation of neutrophils (96). The S100A12 protein and peptides are thought to reduce colonization of Pseudomonas by inhibiting their growth and pathogenicity (97).Two other proteins with ties to inflammatory lung disease were CLCA1, a regulator of mucus production in inflammatory airway disease that may be a target for CF intervention (98), and pendrin, which interacts with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (99) and is a proposed therapeutic target of airway inflammation (100).

Our findings also point to a number of proteins with potential roles in CF that have not been studied in this disease context previously. The phosphatase PPP1CB (101) and the interacting kinase PHKB (102) have metabolic signaling roles. Although not linked with CF, regulation of phosphorylation of CFTR has been proposed as a mediator of therapeutic efficacy (103). Additionally, a network of apolipoproteins had lowered abundance in CF compared to DC samples. This novel finding may be connected to dyslipidemia that has been associated with CF (104) but will require further study.

In our current study, we detected differentially abundant peptides from a number of bacteria with known associations in CF, as well as others with potentially more novel roles. For example, a differentially abundant peptide came from Streptococcus agalactiae, which has been previously reported in respiratory secretions in slightly older patients (105) and is a “Group B” Streptococcus that has been found in sputum of CF patients (106). S. agalactiae has also been suggested as a biomarker for squamous cell lung carcinoma (107) but does not have a known association with CF.

The detection of a differentially abundant peptide from Pseudomonas (Fig. 3B; Table 2) was not a surprise since it is a prevalent pathogen in advanced CF disease (108) with increased abundance in CF adults (109). Interestingly, the detected peptide from the Pseudomonas general secretion pathway protein F, a component of the extracellular type II secretion system (T2SS), involved in the transport of virulence factors thought to be mobilized with a rotary mechanism within the pilus (110, 111). It has been postulated (112) that the T2SS has potential as a target for inhibitory therapeutics of this pathogen. We also detected a mycobacterial peptide in our analysis. An antibiotic-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus has been reported as an opportunistic pathogen in some CF infections (113). A peptide from Actinobacteria was detected (Fig. 3B; Table 2), which is known to be overrepresented in the CF pulmonary microbiome (114) with a significant increase with CF as compared to DC samples (115). A differentially abundant peptide was detected from Ralstonia, whose prevalence in CF patients has been increasingly demonstrated in studies over the years (116–118). Among other peptides detected, specific taxonomy was difficult to ascertain, as these could only be assigned to higher taxonomic classes.

Although most bacterial proteins were detected with one high-confidence peptide, we did identify and quantify one bacterial protein with increased abundance in CF with two peptides matching their sequences (Fig. 3B; Table 2). The protein (A0A246E3Y5_9MICO), although initially annotated as bacterial in origin from the discovery module sequence database, has a human IgG domain, thus making it difficult to assign to the bacterial kingdom. In fact, BLAST-P and Unipept analysis indicated that this peptide could be of human origin and with an immunoglobulin variable region. Given these discrepancies, we decided to describe this protein (along with A0A228ZSI6_ECOLX; see Fig. S6; Table S7) of ambiguous taxonomy. Nevertheless, it is important to note that these proteins are differentially expressed in CF, and further characterization will shed light on their origin.

Despite the achievements demonstrated by our results, both in terms of the novel methodological approach and a promising panel of human and microbial peptide markers, there are some limitations to note. For one, adding new peptides of interest to our panel would most likely require again following the discovery and verification steps of our workflow. Although effective, this would take time and dedicated effort. A potential solution would be to incorporate emerging methods for data independent acquisition (119, 120), which collects a deep, quantitative digital archive of all detectable peptides within complex samples. Such a data archive could be mined for the presence of peptide candidates revealed from ongoing research studies and may offer a more efficient means for verifying the presence of proteins of interest in patient samples and developing targeted methods for their analysis. Additionally, although rigorously characterized in our discovery module, the differential abundance results from our peptide panel were validated in a small number of individual samples. Thus, although promising, these should be viewed as preliminary biomarker candidates for CF. Consequently, we could not make conclusions on differences by samples with high or low microbial diversity within our study or correlate with other clinical variables. A study assaying these peptides in a larger cohort of patient samples is necessary to make such conclusions and should make it possible to correlate differential abundance measurements with clinical variables or other metagenomic information, such as microbial diversity. The information we provide on this peptide panel (Table 2) should make such studies readily achievable for anyone with appropriate clinical samples and access to contemporary MS-based proteomics technologies.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a powerful and novel workflow for discovery, verification, and validation of host and microbe peptide markers in cells collected from BAL samples of CF patients. Our well-characterized panel of peptides should provide an important starting point for larger studies profiling dynamic changes to the proteome and metaproteome in clinical samples, as a response to various experimental variables (e.g., disease progression and therapeutic treatments). As such, the work presented here should contribute significantly to the ongoing progress toward alleviating the burdens of CF lung disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Center for Metabolomics and Proteomics at the University of Minnesota for providing instrumental MS-based analysis of samples for the data generated in this study. We especially thank Jacob Wragge for initial assistance with sample preparation protocols. We also thank the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute at the University of Minnesota for the maintenance and support of Galaxy-based software tools and workflows. Some icon images used in figure creation were designed by artists Freepik, Ultimatearm, Pixel Perfect, and Good Ware from Flaticon.com.

T.J.G., P.D.J., and T.A.L.: Conceptualization; P.D.J., T.J.G., M.E.K., S.M., J.K.H., J.B.O., K.M., and L.H.: Design and methodology; M.E.K., K.M., L.H., P.D.J., S.M., K.D., J.E.J., and R.W.: Data acquisition and analysis; P.D.J.,T.J.G.,J.K.H.,T.A.L.,C.W., and M.E.K.: Data interpretation; T.J.G., P.D.J., M.E.K., S.M., J.K.H., and T.A.L.: Manuscript drafting and editing;T.J.G. and T.A.L.: Funding.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01HL136499. The Orbitrap Eclipse instrumentation platform used in this work was purchased through NIH High-end Instrumentation Grant S10OD028717.

Contributor Information

Pratik D. Jagtap, Email: pjagtap@umn.edu.

Timothy J. Griffin, Email: tgriffin@umn.edu.

Jack A. Gilbert, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA

ETHICS APPROVAL

All human samples were collected using an institutional review board-approved clinical protocol, and samples were de-identified prior to analysis for this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Our raw mass spectrometry data and associated files have been uploaded to the ProteomeXchange PRIDE repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/) and assigned accession PXD041457. Files generated in the discovery module or validation and results reporting module are distinguished by “Pool_” or “Individual,” respectively.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00929-23.

Supplemental tables and figures.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Turcios NL. 2020. Cystic fibrosis lung disease: an overview. Respir Care 65:233–251. doi: 10.4187/respcare.06697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moran Losada P, Chouvarine P, Dorda M, Hedtfeld S, Mielke S, Schulz A, Wiehlmann L, Tümmler B. 2016. The cystic fibrosis lower airways microbial metagenome. ERJ Open Res 2:00096–02015. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00096-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laguna TA, Wagner BD, Williams CB, Stevens MJ, Robertson CE, Welchlin CW, Moen CE, Zemanick ET, Harris JK. 2016. Airway microbiota in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from clinically well infants with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 11:e0167649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greenwald MA, Wolfgang MC. 2022. The changing landscape of the cystic fibrosis lung environment: from the perspective of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Opin Pharmacol 65:102262. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Gast CJ, Walker AW, Stressmann FA, Rogers GB, Scott P, Daniels TW, Carroll MP, Parkhill J, Bruce KD. 2011. Partitioning core and satellite taxa from within cystic fibrosis lung bacterial communities. ISME J 5:780–791. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernarde C, Keravec M, Mounier J, Gouriou S, Rault G, Férec C, Barbier G, Héry-Arnaud G. 2015. Impact of the CFTR-potentiator Ivacaftor on airway microbiota in cystic fibrosis patients carrying a G551D mutation. PLoS One 10:e0124124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lamoureux C, Guilloux CA, Beauruelle C, Jolivet-Gougeon A, Héry-Arnaud G. 2019. Anaerobes in cystic fibrosis patients’ airways. Crit Rev Microbiol 45:103–117. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2018.1549019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frayman KB, Armstrong DS, Carzino R, Ferkol TW, Grimwood K, Storch GA, Teo SM, Wylie KM, Ranganathan SC. 2017. The lower airway microbiota in early cystic fibrosis lung disease: a longitudinal analysis. Thorax 72:1104–1112. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cuthbertson L, Walker AW, Oliver AE, Rogers GB, Rivett DW, Hampton TH, Ashare A, Elborn JS, De Soyza A, Carroll MP, Hoffman LR, Lanyon C, Moskowitz SM, O’Toole GA, Parkhill J, Planet PJ, Teneback CC, Tunney MM, Zuckerman JB, Bruce KD, van der Gast CJ. 2020. Lung function and microbiota diversity in cystic fibrosis. Microbiome 8:45. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00810-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhao J, Schloss PD, Kalikin LM, Carmody LA, Foster BK, Petrosino JF, Cavalcoli JD, VanDevanter DR, Murray S, Li JZ, Young VB, LiPuma JJ. 2012. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:5809–5814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120577109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boutin S, Graeber SY, Weitnauer M, Panitz J, Stahl M, Clausznitzer D, Kaderali L, Einarsson G, Tunney MM, Elborn JS, Mall MA, Dalpke AH. 2015. Comparison of microbiomes from different niches of upper and lower airways in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 10:e0116029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Koff EM, de Winter – de Groot KM, Bogaert D. 2016. Development of the respiratory tract microbiota in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 22:623–628. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michel C, Raimo M, Lazarevic V, Gaïa N, Leduc N, Knoop C, Hallin M, Vandenberg O, Schrenzel J, Grimaldi D, Hites M. 2021. Case report: about a case of hyperammonemia syndrome following lung transplantation: could metagenomic next-generation sequencing improve the clinical management? Front Med (Lausanne) 8:684040. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.684040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Connor JB, Mottlowitz M, Kruk ME, Mickelson A, Wagner BD, Harris JK, Wendt CH, Laguna TA. 2022. Network analysis to identify multi-omic correlations in the lower airways of children with cystic fibrosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:805170. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.805170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Connor JB, Mottlowitz MM, Wagner BD, Boyne KL, Stevens MJ, Robertson CE, Harris JK, Laguna TA. 2021. Divergence of bacterial communities in the lower airways of CF patients in early childhood. PLoS One 16:e0257838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pallenberg ST, Pust M-M, Rosenboom I, Hansen G, Wiehlmann L, Dittrich A-M, Tümmler B. 2022. Impact of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor therapy on the cystic fibrosis airway microbial metagenome. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0145422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01454-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zheng Y, Qiu X, Wang T, Zhang J. 2021. The diagnostic value of metagenomic next–generation sequencing in lower respiratory tract infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.694756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duan H, Li X, Mei A, Li P, Liu Y, Li X, Li W, Wang C, Xie S. 2021. The diagnostic value of metagenomic next⁃generation sequencing in infectious diseases. BMC Infect Dis 21:62. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05746-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nagata N, Nishijima S, Kojima Y, Hisada Y, Imbe K, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Suda W, Kimura M, Aoki R, Sekine K, et al. 2022. Metagenomic identification of microbial signatures predicting pancreatic cancer from a multinational study. Gastroenterology 163:222–238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eyre DW. 2022. Infection prevention and control insights from a decade of pathogen whole-genome sequencing. J Hosp Infect 122:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2022.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Douglas GM, Beiko RG, Langille MGI. 2018. Predicting the functional potential of the microbiome from marker genes using PICRUStMethodss in molecular biology. Methods Mol Biol 1849:169–177. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8728-3_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Y, Zhou Y, Xiao X, Zheng J, Zhou H. 2020. Metaproteomics: a strategy to study the taxonomy and functionality of the gut microbiota. J Proteomics 219:103737. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2020.103737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petriz BA, Franco OL. 2017. Metaproteomics as a complementary approach to gut microbiota in health and disease. Front Chem 5:4. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kolmeder CA, de Vos WM. 2021. Roadmap to functional characterization of the human intestinal microbiota in its interaction with the host. J Pharm Biomed Anal 194:113751. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Issa Isaac N, Philippe D, Nicholas A, Raoult D, Eric C. 2019. Metaproteomics of the human gut microbiota: challenges and contributions to other OMICS. Clin Mass Spectrom 14 Pt A:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clinms.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang X, Li L, Butcher J, Stintzi A, Figeys D. 2019. Advancing functional and translational microbiome research using meta-omics approaches. Microbiome 7. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0767-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hardouin P, Chiron R, Marchandin H, Armengaud J, Grenga L. 2021. Metaproteomics to decipher cf host-microbiota interactions: overview, challenges and future perspectives. Genes (Basel) 12:892. doi: 10.3390/genes12060892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kamath KS, Kumar SS, Kaur J, Venkatakrishnan V, Paulsen IT, Nevalainen H, Molloy MP. 2015. Proteomics of hosts and pathogens in cystic fibrosis. Proteom Clin Appl 9:134–146. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma G, Pan J, Han J, Gao L, Zhang S, Li R. 2017. Identification of M. tuberculosis antigens in the sera of tuberculosis patients using biomimetic affinity chromatography in conjunction with ESI-CID-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1061–1062:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rechenberger J, Samaras P, Jarzab A, Behr J, Frejno M, Djukovic A, Sanz J, González-Barberá EM, Salavert M, López-Hontangas JL, Xavier KB, Debrauwer L, Rolain JM, Sanz M, Garcia-Garcera M, Wilhelm M, Ubeda C, Kuster B. 2019. Challenges in clinical metaproteomics highlighted by the analysis of acute leukemia patients with gut colonization by multidrug-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Proteomes 7:2. doi: 10.3390/proteomes7010002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blakeley-Ruiz JA, Kleiner M. 2022. Considerations for constructing a protein sequence database for metaproteomics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 20:937–952. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jagtap P, Goslinga J, Kooren JA, McGowan T, Wroblewski MS, Seymour SL, Griffin TJ. 2013. A two-step database search method improves sensitivity in peptide sequence matches for metaproteomics and proteogenomics studies. Proteomics 13:1352–1357. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kumar P, Johnson JE, Easterly C, Mehta S, Sajulga R, Nunn B, Jagtap PD, Griffin TJ. 2020. A sectioning and database enrichment approach for improved peptide spectrum matching in large, genome-guided protein sequence databases. J Proteome Res 19:2772–2785. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muth T, Benndorf D, Reichl U, Rapp E, Martens L. 2013. Searching for a needle in a stack of needles: challenges in metaproteomics data analysis. Mol Biosyst 9:578–585. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25415h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liao B, Ning Z, Cheng K, Zhang X, Li L, Mayne J, Figeys D. 2018. IMetaLab 1.0: a web platform for metaproteomics data analysis. Bioinformatics 34:3954–3956. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muth T, Kohrs F, Heyer R, Benndorf D, Rapp E, Reichl U, Martens L, Renard BY. 2018. MPA portable: a stand-alone software package for analyzing metaproteome samples on the go. Anal Chem 90:685–689. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blank C, Easterly C, Gruening B, Johnson J, Kolmeder CA, Kumar P, May D, Mehta S, Mesuere B, Brown Z, Elias JE, Hervey WJ, McGowan T, Muth T, Nunn BL, Rudney J, Tanca A, Griffin TJ, Jagtap PD. 2018. Disseminating metaproteomic informatics capabilities and knowledge using the galaxy-P framework. Proteomes 6:7. doi: 10.3390/proteomes6010007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Easterly CW, Sajulga R, Mehta S, Johnson J, Kumar P, Hubler S, Mesuere B, Rudney J, Griffin TJ, Jagtap PD. 2019. MetaQuantome: an integrated, quantitative metaproteomics approach reveals connections between taxonomy and protein function in complex microbiomes. Mol Cell Proteomics 18:S82–S91. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA118.001240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hardouin P, Pible O, Marchandin H, Culotta K, Armengaud J, Chiron R, Grenga L. 2022. Quick and wide-range taxonomical repertoire establishment of the cystic fibrosis lung microbiota by tandem mass spectrometry on sputum samples. Front Microbiol 13:975883. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.975883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]