Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system (PCNSL) is challenging and often delayed. MRI imaging, CSF cytology and flow cytometry have a low sensitivity and even brain biopsies can be misleading. We report three cases of PCNSL with various clinical presentation and radiological findings where the diagnosis was suggested by novel CSF biomarkers and subsequently confirmed by brain biopsy or autopsy.

Case presentations.

The first case is a 79-year-old man with severe neurocognitive dysfunction and static ataxia evolving over 5 months. Brain MRI revealed a nodular ventriculitis. An open brain biopsy was inconclusive. The second case is a 60-year-old woman with progressive sensory symptoms in all four limbs, evolving over 1 year. Brain and spinal MRI revealed asymmetric T2 hyperintensities of the corpus callosum, corona radiata and corticospinal tracts. The third case is a 72-year-old man recently diagnosed with primary vitreoretinal lymphoma of the right eye. A follow-up brain MRI performed 4 months after symptom onset revealed a T2 hyperintense fronto-sagittal lesion, with gadolinium uptake and perilesional edema. In all three cases, CSF flow cytometry and cytology were negative. Mutation analysis on the CSF (either by digital PCR or by next generation sequencing) identified the MYD88 L265P hotspot mutation in all three cases. A B-cell clonality study, performed in case 1 and 2, identified a monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin light chain lambda (IGL) and kappa (IGK) gene. CSF CXCL-13 and IL-10 levels were high in all three cases, and IL-10/IL-6 ratio was high in two. Diagnosis of PCNSL was later confirmed by autopsy in case 1, and by brain biopsy in case 2 and 3.

Conclusions

Taken together, 5 CSF biomarkers (IL-10, IL-10/IL-6 ratio, CXCL13, MYD88 mutation and monoclonal IG gene rearrangements) were strongly indicative of a PCNSL. Using innovative CSF biomarkers can be sensitive and complementary to traditional CSF analysis and brain biopsy in the diagnosis of PCNSL, potentially allowing for earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: PCNSL, Lymphoma, Cerebrospinal fluid, Biomarker

Background

Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of central nervous system (PCNSL), also called primary large B-cell lymphoma of immune-privileged sites [1, 2], is a highly aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that is confined to the CNS, without any evidence of systemic lymphoma, and accounts for about 3–4% of all CNS tumors [3]. Diagnosis of PCNSL requires a high level of suspicion, as clinical and radiological presentation may be unusual. Definitive diagnosis is typically established by histopathological analysis of stereotactic or open brain biopsy (gold standard). When brain biopsy is not feasible or not contributory, the diagnosis becomes challenging. Several indirect ways may assist to establish the diagnosis: cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology is the gold standard for diagnosing meningeal dissemination of PCNSL, but the sensitivity remains probably less than 16% [4]. CSF flow cytometry has been proposed to improve diagnosis accuracy in CNS localizations of hematologic malignancies [5], but its sensitivity in detecting PCNSL is between 3 and 23% [6–8]. To improve sensitivity with CSF cytology and flow cytometry, it is recommended to collect large CSF volume and perform multiple lumbar punctures. We report three cases of PCNSL with various clinical presentation and radiological findings where the diagnosis was suggested by novel CSF biomarkers and subsequently confirmed by brain biopsy or autopsy.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 79-year-old man presented with behavior disturbance, gait problems and anorexia with a loss of weight (10 kg), evolving over about 5 months. Neuropsychological examination revealed a multimodal disorientation, severe anterograde and retrograde amnesia, executive dysfunction, and non-lateralized attentional deficit. Neurological examination showed static ataxia with a tendency to retropulsion, and no other abnormalities.

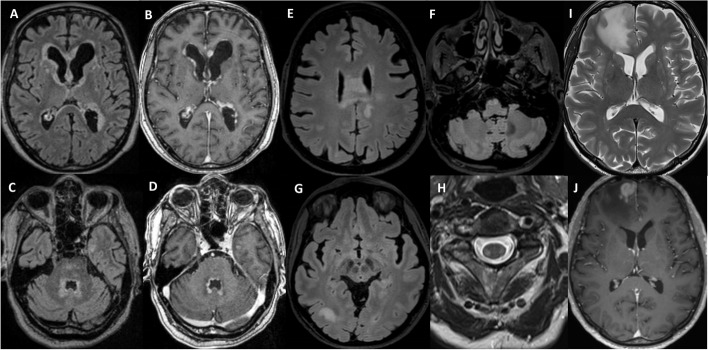

A brain MRI 5 months after symptoms onset showed periventricular (adjacent to the lateral, third and fourth ventricles) T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity, with partially nodular gadolinium enhancement (Fig. 1A-D). CSF analysis showed lymphocytic pleocytosis (194 cells/mm3, 98% lymphocytes), hyperproteinorachia (3881 mg/l), normal glucose and lactate and absence of intrathecal IgG synthesis.

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI of the three cases. Case 1: Initial MRI with periventricular T2/FLAIR hyperintensities (A, C) and nodular gadolinium enhancement (B, D). Case 2: Brain MRI with T2/FLAIR hyperintensities of the corpus callosum extending to the corona radiata (E), of the right parieto-occipital subcortical white matter (G) and of the bilateral pyramids (F). Spinal MRI with bilateral lateral columns T2 hyperintensities (H). Case 3: Brain MRI with T2 hyperintense fronto-sagittal lesion and perilesional edema (I) and strong gadolinium enhancement (J)

Infectious causes were reasonably excluded. An extensive immunological workup was within normal limits, providing no evidence for a systemic disease, particularly a granulomatous vasculitis, sarcoidosis, nor IgG4-related disease. A salivary gland biopsy revealed a lympho-plasmocytic infiltrate without any granuloma or evidence of Sjögren disease. Whole-body CT scan and 18F-FDG PET were normal, and 3 CSF cytology and 4 CSF flow cytometry analyses were unremarkable. Slit-lamp ophthalmologic examination was normal. An open brain biopsy of a nodule adjacent to the left frontal horn, performed without prior glucocorticoid therapy, was not conclusive and only revealed a reactive astrogliosis and a slight lympho-histiocytic infiltrate.

At this point, the main suspicions were of an oncological disease of the CNS (particularly lymphoma), or an inflammatory granulomatous disease. As the neurological evolution was unfavorable, empiric treatment with IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day was introduced. After transient improvement, the patient’s neurological condition subsequently worsened with the onset of a focal status epilepticus requiring three lines of antiseizure medication, and a severe pneumonia. A second brain biopsy was considered, but because of the lesions being too deep, the risk–benefit ratio was judged unfavorable.

Targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) (using a custom capture-based panel covering 142 genes relevant for hematological neoplasms) was performed on DNA extracted from 4 pooled CSF samples and identified the MYD88 L265P hotspot mutation at a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 6%, in addition to several other mutations. A B-cell clonality study identified a monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin light chain lambda (IGL) gene. An extensive CSF cytokine and chemokine panel analysis was performed. CSF CXCL-13 was 10′826 pg/ml, IL-10 level was 34 pg/ml and IL-10/IL-6 ratio was 0.48 (Table 1). Taken together, those results were strongly suggestive of a B-cell lymphoma. Unfortunately, the patient developed a pulmonary sepsis and passed away before treatment could be initiated.

Table 1.

CSF diagnostic biomarkers in the 3 cases

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | IL-10/IL-6 ratio | CXCL-13 (pg/ml) | MYD88 mutation analysisb | B-cell clonality assays | Cytology | Flow cytometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 34a | 0.48 | 10′826a | L265Pa | Monoclonal IGL gene rearrangementa | Neg (3x) | Neg (4x) |

| Case 2 | 52a | 7.5a | 3′053a | L265Pa | Monoclonal IGK gene rearrangementa | Neg (1x) | Neg (1x) |

| Case 3 | 68a | 16.2a | 239a | L265Pa | Not performed | Neg (1x) | Neg (1x) |

| Published cut-offs for PCNSL diagnosis | > 2.7–16.15 pg/ml (12) | > 0.72–1.6 (19–21) | > 80–90 pg/ml (9,10,13,14) | ||||

IL-10 Interleukin-10, IL-6 Interleukin-6, CXCL-13 Chemokine ligand 13, MYD88 Myeloid differentiation primary response 88, IGL Immunoglobulin light chain lambda, PCNSL Primary central nervous system lymphoma, Neg Negative

aValues/test results suggestive of PCNSL

bIdentification of the MYD88 hotspot mutation, c.794 T > C p.(Leu265Pro) – most commonly referred to as L265P – according to reference transcript NM_002468.4. According to other reference transcripts this same mutation may be referred to as c.755 T > C p.(Leu252Pro) (NM_002468.5, corresponding to the currently approved MANE transcript), or as c.818 T > C p.(Leu273Pro) (NM_001172567.1 or LRG_157t1)

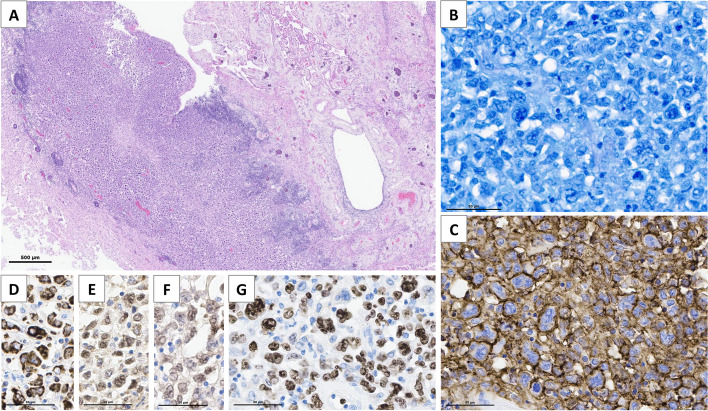

Histological analysis of autopsied central nervous system tissue revealed a large B-cell lymphoma restricted to the CNS, CD5 + , lambda + , of non-germinal center-like phenotype, BCL2 + , MYC-, with strong proliferation (80%), EBV negative (Fig. 2). MYD88 mutation detection was not performed on autopsy tissue.

Fig. 2.

Brain autopsy findings in patient 1. Thickening of periventricular areas that are infiltrated by a diffuse population of large tumor cells without glandular or squamous differentiation (A, Hematoxylin–Eosin staining). The tumor is composed of a diffuse proliferation of large cells with a high nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio, mono- and multilobated nuclei, numerous mitoses (B, Giemsa staining) and high proliferation index Ki67/MIB1 near 80% (G). Tumor cells express CD20 (C), with coexpression of Bcl2 (D), Bcl6 (E) and MUM1 (F), and are monotypic for immunoglobulin light chain lambda, consistent with the diagnosis of primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of CNS (EBV negative, not shown)

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman presented with slowly progressive ascending sensory symptoms involving both feet, hands and trunk, associated with urinary symptoms, slight imbalance and dysarthria, evolving over about a year. A first brain and spinal MRI, performed 8 months after symptoms onset, was unremarkable. Neurological examination showed slight dysarthria, lower limbs tactile hypoesthesia with a T6 sensory level, increased reflexes in four limbs with a bilateral positive Hoffmann sign and toe flexor responses, and a sensory ataxia. A cervical or thoracic myelopathy was suspected.

Brain and spinal MRI performed 1 year after symptoms onset showed asymmetric T2-FLAIR hyperintensity lesions of the splenium of the corpus callosum, extending to the corona radiata, of the right subcortical parieto-occipital region and of the bilateral corticospinal tracts, starting from the pyramids, down to the lateral corticospinal bundles of the cervicothoracic medulla (Fig. 1E-H). There was no gadolinium enhancement. An MRI spectroscopy of the corpus callosum lesion was normal. CSF analysis showed no pleocytosis (2 cells/mm3), normal protein levels (386 mg/l), normal glucose and lactate and no intrathecal IgG synthesis.

Based on the MRI lesions, a leukodystrophy was initially suspected. A broad metabolic and genetic workup remained negative. However, the asymmetry of the brain lesions, the extent of the spinal cord involvement and the rapid onset of the lesions (within 3 months) strongly argued against a metabolic process. An extensive immunological workup was within normal limits, providing no evidence for a systemic disease. Whole-body CT scan was normal and 18F-FDG PET only showed a 18F-FDG hypermetabolism of the spinal cord lesions. One CSF cytology and flow cytometry analyses were within normal limits. Slit-lamp ophthalmologic examination was normal.

Targeted NGS on the CSF identified the MYD88 L265P mutation at a VAF of 1.94%. A B-cell clonality study identified a monoclonal rearrangement of the immunoglobulin light chain kappa (IGK) gene. CSF CXCL-13 was 3053 pg/ml, IL-10 level was 52 pg/ml, and IL-10/IL-6 ratio was 7.5 (Table 1). Taken together, these findings were strongly suggestive of a B-cell lymphoma. An open brain biopsy of the right parieto-occipital lesion showed infiltration by a large B-cell lymphoma, CD5 + , kappa + , of non-germinal center-like phenotype, BCL2 + , MYC-, with strong proliferation (60%), EBV negative. Targeted NGS on tissue identified the MYD88 L265P mutation at a VAF of 36%.

The patient was treated with MATRix chemotherapy (high-dose methotrexate, high-dose cytarabine, thiotepa and rituximab), followed by an intensification chemotherapy with carmustine-thiotepa and an autologous stem cell transplantation. The clinical and radiological response was initially favorable. Unfortunately, a radiological recurrence, confined to the CNS, occurred 4 months after the transplantation. A second-line chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) -T cell therapy with lisocabtagene maraleucel was started in April 2024.

Case 3

A 72-year-old man was recently diagnosed with primary vitreoretinal lymphoma of the right eye, treated with intraocular dexamethasone and methotrexate. Diagnosis was made by vitreous humor cytopathology, which confirmed a CD20 + large B cell lymphoma. The first brain MRI performed at the time of the diagnosis was described as normal. The MYD88 L265P mutation had already been demonstrated on that ocular sample, by pyrosequencing.

A follow-up MRI performed 4 months after diagnosis demonstrated a T2 hyperintense fronto-sagittal lesion, with strong gadolinium uptake and a surrounding perilesional edema (Fig. 1I-J). The patient showed no neurological symptoms at this stage, and neurological examination was normal. CSF analysis showed no pleocytosis (0 cells/mm3), normal protein levels (475 mg/l), normal glucose and lactate. One CSF cytology and flow cytometry were unremarkable.

DdPCR on the CSF identified the MYD88 L265P mutation at a VAF of 0.56%. CSF CXCL-13 was 239 pg/ml, IL-10 level was 68 pg/ml, and IL-10/IL-6 ratio was 16.2 (Table 1). An open brain biopsy and surgical exeresis of the right frontal lesion confirmed a large B-cell lymphoma restricted to the CNS, CD5-, IgM kappa + , of non-germinal center-like phenotype, BCL2 + , MYC + , with strong proliferation (> 90%), EBV negative. Targeted NGS on tissue identified the MYD88 L265P mutation at a VAF of 55%.

The patient was treated with PRIMAIN protocol chemotherapy (high-dose methotrexate, procarbazine and rituximab), followed by maintenance therapy with procarbazine. Six months later, he presented with a clinical and radiological recurrence, prompting second-line chemotherapy with TEDDi-R (ibrutinib, rituximab, temozolomide, etoposide, doxorubicine and dexamethasone). Two months later, a new recurrence occurred, prompting a third line of treatment with CAR-T cells (tisagenlecleucel) and stereotactic radiotherapy. Unfortunately, the patient rapidly developed a severe disorder of consciousness due to obstructive hydrocephalus and subsequently died in a palliative care institution.

Discussion and conclusions

Those clinical cases illustrate the diagnostic challenges associated with PCNSL. Clinical presentation can be highly variable, the first case presenting as a nodular ventriculitis, mimicking a CNS neuro-inflammatory disease, the second one presenting clinically as a chronic myelopathy, with MRI lesions suggestive of leukodystrophy, and the third case presenting as a solitary brain nodule with perilesional edema and contrast enhancement. CSF cytology and flow cytometry yielded negative results. However, CSF IL-10 and CXCL13 level were above published cut-offs, which was strongly suggestive of PCNSL according to studies by Rubenstein et al. and Maeyama et al. [9, 10]. CSF IL-10/IL-6 ratio was negative in case 1 and positive in cases 2 and 3. Furthermore, the MYD88 L265P hotspot mutation was found in all cases. Monoclonal rearrangement of the IGL gene was detected in case 1, and of the IGK gene was detected in case 2, while no B-cell clonality assay was performed in case 3. Final diagnosis was made on brain biopsy in case 2 and 3, but unfortunately was made only with autopsy in case 1.

CSF cytokines/chemokines

CSF cytokines and chemokines are promising biomarkers of PCNSL but need to be validated [11, 12]. CXCL-13, IL-10 and IL-10/IL-6 ratio have been proposed to best correlate with PCNSL.

CXCL-13 is a B lymphocyte chemo attractant that binds to CXCR5 receptor and could contribute to lymphoma genesis [12]. Four recent studies demonstrated that an increase of CSF CXCL13 level had a sensitivity of 70–91% and specificity of 87–93% for CNS lymphoma diagnosis, with cutoffs between 80 and 90 pg/ml [9, 10, 13, 14]. According to a recent review from Li et al., CSF CXCL13 may also be a promising biomarker for prognosis assessment and disease monitoring in PCNSL [15]. However, CSF CXCL13 is not specific as it is known to be increased in other neurological diseases, such as neuroborreliosis or inflammatory disease of the CNS.

One of the most studied CSF cytokine biomarker is IL-10, a cytokine produced by type 2 T helper lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages and B lymphocytes, whose immunosuppressive and growth factor functions may favor lymphoma genesis [16]. Its elevation was correlated with CNS lymphoma in at least nine studies, summarized in Nguyen-Them et al. paper, with a sensitivity of 59–96% and a specificity of 83–100% [12]. No clear cutoff value was admitted, varying from 2.7 to 16.15 pg/ml [12]. Concurrent elevation of CSF CXCL13 and IL-10 increased the diagnostic sensitivity to 97% and specificity to 97–99% according to two recent studies [9, 10]. As CSF IL-10 level may reflect tumor burden, it could also be a useful prognosis marker at diagnosis and in posttreatment evaluation [17, 18].

In addition, the elevation of CSF IL-10/IL-6 ratio was also correlated with PCNSL in three studies, with cut-offs above 0.72–1.6 harboring a sensitivity of 66–95.5% and a specificity of 91–100% [19–21].

B-cell clonality assays and MYD88 mutation

PCR-based analysis of immunoglobulin heavy and light chain gene rearrangements (B-cell clonality assays) can identify monoclonal B-cell populations in the CSF, with variable sensitivity according to studies [4, 22–24]. The rather low sensitivity may be due in part to the absence or the small number of circulating tumor cells in the CSF.

MYD88 mutations, particularly the L265P hotspot mutation, are encountered in approximately half of PCNSL and, although not completely specific, are strongly suggestive of the diagnosis. The L265P mutation can be detected by various PCR or sequencing approaches, including ddPCR and targeted NGS panels. DdPCR is known for its superior sensitivity compared with other PCR techniques (such as real-time quantitative PCR) and NGS, as it requires only minimal amount of DNA. DdPCR has been shown to be an ideal technique for MYD88 L265P molecular analysis in CSF sample [25]. MYD88 L265P mutations were detected from CSF in 63.5–92% of PCNSL cases, with a specificity close to 100% [26–31]. Sporadic cases of MYD88 L265P mutations in the CSF have been reported in other neurological diseases, such as multiple sclerosis [27]. Combined with an elevated CSF IL-10, sensitivity increased to 94% and specificity was 98% [27]. Combining MYD88 L265P mutation detection and B-cell clonality assay on CSF cellular and cell-free DNA also improved the diagnosis of PCNSL [32].

Taken together, the combination of 5 CSF biomarkers (IL-10, IL-10/IL-6 ratio, CXCL13, MYD88 mutation and monoclonal IG gene rearrangements) are strongly indicative of a PCNSL. Those cases illustrate that CSF analysis using innovative biomarkers can be a sensitive and complementary method to traditional CSF analysis (cytology and flow cytometry) and brain biopsy in the diagnosis of PCNSL. Moreover, the simultaneous use of multiple CSF biomarkers may enhance diagnostic performance, especially in patients that have an atypical clinical or radiological presentation. Multi-marker diagnostic algorithms, such as the one published by Maeyama et al., need to be further developed for patient with CNS lymphoma [10].

CSF biomarkers analysis has the advantage of being a minimally invasive and fast diagnostic method. It can be very useful for diagnosis in the absence of brain parenchymal lesion, when brain biopsy cannot be safely performed (e.g. in elderly/frail patients or when lesions are located in deep brain structures) and to overcome the challenge of sampling error with brain biopsy, especially due to prior glucocorticoid treatment [33]. Recently, it has been shown that targeted genotyping of CSF, especially for MYD88 mutation detection, enables rapid diagnosis of CNS lymphoma and can accelerate the initiation of disease-directed treatment [34]. Methylation-based CSF liquid biopsies have also been shown to accurately classify the major three brain tumors (CNS lymphoma, glioblastoma and brain metastasis) [35]. Reviews on clinical application of liquid biopsy in CNS lymphoma was recently published by the RANO (Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology) group [36]. However, histopathology provides additional information concerning the lymphoma “cell of origin” subtype (germinal center versus activated B-cell), the presence of rearrangements (MYC, BCL2 and BCL6) and the molecular subtype, informations that cannot currently be provided by non-invasive diagnostic method. Those informations can be of prognostic value, and molecular characteristics may lead, in the future, to the introduction of targeted treatment approaches.

Conclusion

Diagnosis of PCNSL is laborious and is typically established by pathological evaluation of a brain biopsy. In cases where brain biopsy is infeasible or inconclusive, CSF analysis becomes a valuable diagnostic tool. Detection of neoplastic cells in the CSF by cytology and flow cytometry is a diagnostic alternative, but its sensitivity is very low. Innovative CSF diagnostic biomarkers exists, such as IL-10 and CXCL13 concentrations, IL-10/IL-6 ratio, B-cell clonality studies and MYD88 mutation analysis, but they need to be validated in larger clinical studies and their use need to be better standardized, in order to improve the diagnosis and management of patient with PCNSL.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for their cooperation and participation in this study.

Abbreviations

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- ddPCR

Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction

- FLAIR

Fluid attenuation inversion recovery

- IG

Immunoglobulin gene

- IGK

Immunoglobulin light chain kappa gene

- IGL

Immunoglobulin light chain lambda gene

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- PCNSL

Primary central nervous system lymphoma

Authors’ contributions

VL: investigations (leading), writing—original draft preparation (equal). AS: writing—review and editing (equal). LDL: writing-review and editing (equal), performed cytopathologic and/or histopathologic diagnoses. BB: writing-review and editing (equal), performed molecular analysis. JPB: writing-review and editing (equal), performed cytopathologic and/or histopathologic diagnoses. EH: writing-review and editing (equal), performed cytopathologic and/or histopathologic diagnoses. CB: writing-review and editing (equal), performed cytopathologic and/or histopathologic diagnoses. AH: writing-review and editing (equal). CP: investigations (leading), writing—original draft preparation (equal). All authors wrote, edited, and significantly contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. The study being a case-based study, with a limited number of subjects, there was no need for ethics commission approval.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s son (the patient was unable to provide consent due to severe cognitive impairment) for personal and clinical data to be published in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Valentin Loser, Email: valentin.loser@chuv.ch.

Caroline Pot, Email: caroline.pot-kreis@chuv.ch.

References

- 1.Alaggio R, Amador C, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1720–48. 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo E, Jaffe ES, Cook JR, et al. The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood. 2022;140(11):1229–53 Blood. 2023;141(4):437. 10.1182/blood.2022015851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoang-Xuan K, Bessell E, Bromberg J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary CNS lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: guidelines from the European Association for Neuro-Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e322–32. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00076-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baraniskin A, Schroers R. Modern cerebrospinal fluid analyses for the diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the CNS. CNS Oncol. 2014;3:77–85. 10.2217/cns.13.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromberg JE, Breems DA, Kraan J, et al. CSF flow cytometry greatly improves diagnostic accuracy in CNS hematologic malignancies. Neurology. 2007;68:1674–9. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261909.28915.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Au KLK, Latonas S, Shameli A, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow Cytometry: Utility in Central Nervous System Lymphoma Diagnosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020;47:382–8. 10.1017/cjn.2020.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiewe P, Fischer L, Martus P, Thiel E, Korfel A. Meningeal dissemination in primary CNS lymphoma: diagnosis, treatment, and survival in a large monocenter cohort. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:409–17. 10.1093/neuonc/nop053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroers R, Baraniskin A, Heute C, et al. Detection of free immunoglobulin light chains in cerebrospinal fluids of patients with central nervous system lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2010;85:236–42. 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein JL, Wong VS, Kadoch C, et al. CXCL13 plus interleukin 10 is highly specific for the diagnosis of CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(23):4740–8 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeyama M, Sasayama T, Tanaka K, et al. Multi-marker algorithms based on CXCL13, IL-10, sIL-2 receptor, and β2-microglobulin in cerebrospinal fluid to diagnose CNS lymphoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9(12):4114–25. 10.1002/cam4.3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Westrhenen A, Smidt LCA, Seute T, et al. Diagnostic markers for CNS lymphoma in blood and cerebrospinal fluid: a systematic review. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(3):384–403. 10.1111/bjh.15410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen-Them L, Alentorn A, Ahle G, et al. CSF biomarkers in primary CNS lymphoma. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2022;S0035–3787(22):00784–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mabray MC, Barajas RF, Villanueva-Meyer JE, et al. The Combined Performance of ADC, CSF CXC Chemokine Ligand 13, and CSF Interleukin 10 in the Diagnosis of Central Nervous System Lymphoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(1):74–9. 10.3174/ajnr.A4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masouris I, Manz K, Pfirrmann M, et al. CXCL13 and CXCL9 CSF Levels in Central Nervous System Lymphoma-Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Prognostic Relevance. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 654543. 10.3389/fneur.2021.654543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, Zhang L, Jin Q, Jiang H, Wu C. Role and application of chemokine CXCL13 in central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Hematol. Published online November 27, 2023. 10.1007/s00277-023-05560-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Voorzanger N, Touitou R, Garcia E, et al. Interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-6 are produced in vivo by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells and act as cooperative growth factors. Cancer Res. 1996;56(23):5499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen-Them L, Costopoulos M, Tanguy ML, et al. The CSF IL-10 concentration is an effective diagnostic marker in immunocompetent primary CNS lymphoma and a potential prognostic biomarker in treatment-responsive patients. Eur J Cancer. 2016;61:69–76. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasayama T, Nakamizo S, Nishihara M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-10 is a potentially useful biomarker in immunocompetent primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:368–80. 10.1093/neuonc/nor203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Y, Zhang W, Zhang L, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid IL-10 and IL-10/IL-6 as Accurate Diagnostic Biomarkers for Primary Central Nervous System Large B-cell Lymphoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38671. 10.1038/srep38671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao J, Chen K, Li Q, et al. High Level of IL-10 in Cerebrospinal Fluid is Specific for Diagnosis of Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:6261–8 Published 2020 Jul 24. 10.2147/CMAR.S255482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ungureanu A, Le Garff-Tavernier M, Costopoulos M, et al. CSF interleukin 6 is a useful marker to distinguish pseudotumoral CNS inflammatory diseases from primary CNS lymphoma. J Neurol. 2021;268(8):2890–4. 10.1007/s00415-021-10453-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armand M, Costopoulos M, Osman J, et al. Optimization of CSF biological investigations for CNS lymphoma diagnosis. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(10):1123–31. 10.1002/ajh.25578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Cao F, Wang S, Zhou J, et al. Detection of malignant B lymphocytes by PCR clonality assay using direct lysis of cerebrospinal fluid and low volume specimens. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(2):165–73. 10.1111/ijlh.12255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nachmias B, Sandler V, Slyusarevsky E, Pogrebijski G, Kritchevsky S, Ben-Yehuda D, et al. Evaluation of cerebrospinal clonal gene rearrangement in newly diagnosed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(11):2561–7. 10.1007/s00277-019-03798-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiemcke-Jiwa LS, Minnema MC, Radersma-van Loon JH, et al. The use of droplet digital PCR in liquid biopsies: A highly sensitive technique for MYD88 p.(L265P) detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Hematol Oncol. 2018;36(2):429–35. 10.1002/hon.2489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe J, Natsumeda M, Okada M, et al. High Detection Rate of MYD88 Mutations in Cerebrospinal Fluid From Patients With CNS Lymphomas. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3:1–13. 10.1200/PO.18.00308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreri AJM, Calimeri T, Lopedote P, et al. MYD88 L265P mutation and interleukin-10 detection in cerebrospinal fluid are highly specific discriminating markers in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: results from a prospective study. Br J Haematol. 2021;193(3):497–505. 10.1111/bjh.17357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimelen V, Ahle G, Pencreach E, et al. Tumor cell-free DNA detection in CSF for primary CNS lymphoma diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):43. 10.1186/s40478-019-0692-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta M, Burns EJ, Georgantas NZ, et al. A rapid genotyping panel for detection of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Blood. 2021;138(5):382–6. 10.1182/blood.2020010137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamagishi Y, Sasaki N, Nakano Y, et al. Liquid biopsy of cerebrospinal fluid for MYD88 L265P mutation is useful for diagnosis of central nervous system lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(11):4702–10. 10.1111/cas.15133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen F, Pang D, Guo H, et al. Clinical outcomes of newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma treated with ibrutinib-based combination therapy: a real-world experience of off-label ibrutinib use. Cancer Med. 2020;9(22):8676–84. 10.1002/cam4.3499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bravetti C, Degaud M, Armand M, et al. Combining MYD88 L265P mutation detection and clonality determination on CSF cellular and cell-free DNA improves diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2023;201(6):1088–96. 10.1111/bjh.18758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikolajewicz N, Yee PP, Bhanja D, et al. Systematic Review of Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Discovery in Neuro-Oncology: A Roadmap to Standardization and Clinical Application. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16):1961–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Gupta M, Bradley J, Massaad E, et al. Rapid Tumor DNA Analysis of Cerebrospinal Fluid Accelerates Treatment of Central Nervous System Lymphoma. Blood. 2024. 10.1182/blood.2024023832. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Zuccato JA, Patil V, Mansouri S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid methylome-based liquid biopsies for accurate malignant brain neoplasm classification. Neuro Oncol. 2023;25(8):1452–60. 10.1093/neuonc/noac264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nayak L, Bettegowda C, Scherer F, et al. Liquid biopsy for improving diagnosis and monitoring of CNS lymphomas: A RANO review. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26(6):993–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.