Abstract

Background:

Palliative care affords numerous benefits, including improvements in symptom management, mental health, and quality of life, financial savings, and decreased mortality. Yet palliative care is poorly understood and often erroneously viewed as end-of-life care and hospice. Barriers for better education of the public about palliative care and its benefits include shortage of healthcare providers specializing in palliative care and generalist clinicians’ lack of knowledge and confidence to discuss this topic and time constraints in busy clinical settings.

Objectives:

Explore and compare the knowledge, values, and practices of community-dwelling adults 19 years and older from Nebraska about serious illness and end-of-life healthcare options.

Design:

Secondary analysis of cross-sectional data collected in 2022 of 635 adults. We examined the fifth wave (2022) of a multiyear survey focusing on exploring Nebraskans’ understanding of and preferences related to end-of-life care planning.

Methods:

Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests to compare results between groups. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses examine associations of variables as to knowledge of hospice and palliative care.

Results:

While 50% of respondents had heard a little or a lot about palliative care, 64% either did not know or were not sure of the difference between palliative care and hospice. Those who reported being in poor health were not more likely to know the difference between palliative care and hospice compared to those reporting being in fair, good, or excellent health.

Conclusion:

This study offers insight into the knowledge and attitudes about palliative care among community-dwelling adults, 19 years and older living in Nebraska. More effort is needed to communicate what palliative care is, who can receive help from it, and why it is not only for people at end of life. Advance care planning discussions can be useful in offering clarity.

Keywords: advance care planning, hospice care, palliative care, serious illness, supportive

The concept and practice of palliative care has served as a source of support for patients and families facing serious illness since the mid-to-late 20th century. 1 While oftentimes associated with hospice care, 2 the benefits of palliative care for those with chronic, serious conditions can be far-reaching. These benefits include financial savings, quality of life improvements, increased survivability, improved mental health, and better symptom management.3–9 These outcomes are a result of earlier goals of care conversations that promote patient-centered care by aligning patients’ values with the care they receive.

Yet understanding the support palliative care offers is often lost for those with serious illness when it is believed to be limited to end-of-life care. Palliative care is based on a diagnosis of a serious illness, while hospice care is focused on both the diagnosis along with a 6 months or less benefit requirement. Palliative care is an umbrella term with a focus on supportive care that addresses sources of suffering to provide relief and promote quality of life but not intended as a cure. 10

Earlier studies illuminate a lack of awareness and understanding of palliative care,11–13 which has contributed to low use by those most in need and when it could offer the greatest benefit for addressing serious symptoms. 14 Likewise, research has demonstrated that even when individuals identify as having knowledge of what palliative care is it is often full of inaccuracies and misperceptions.15,16 Additionally, a gap in awareness and discomfort of practitioners in recommending palliative care or end-of-life care 17 suggests a need for greater efforts directed toward communicating the purpose and value of palliative care to and for patients with serious illness whose prognosis is years compared to the months required for hospice care.14,18 Moreover, as reflected in both local and national surveys, 11 the confusion between palliative care and hospice care underscores the value and importance of finding ways to educate patients, families, and the professional community of the benefits of palliative care, regardless of prognosis and beyond end-of-life care.

Current practice

Given the shortage of healthcare providers specializing in palliative care, communication about treatment options during serious illness and at the end of life, including palliative and hospice care, is increasingly the responsibility of generalist clinicians. 19 However, many generalist healthcare providers feel challenged by limited time or lack of training in having difficult conversations involving mortality, treatment options, and end-of-life preferences.10,20,21 Despite significant efforts to increase awareness and communication training about palliative care, gaps in palliative care competence remain. Misperceptions of palliative care exist in the healthcare provider and patient realms of understanding. On the provider side, barriers such as a lack of confidence, skills, and education have been identified as significant hurdles to palliative care use.22,23 Research suggests that delay in conducting these important discussions is compounded by divergent views on the healthcare team about whose responsibility it is to initiate palliative (serious illness) care conversations, resulting in one healthcare professional waiting on another to take the initiative. 24

Ultimately, this void in communication leaves patients and their families confused, dissatisfied, and uninformed as to the benefits that palliative care, and when needed, hospice care can provide. Taber et al. 25 found that relatively few individuals understand what palliative care is or are even aware of it. Likewise, in this study, the authors note that even when individuals indicated having increased levels of awareness, it did not necessarily translate into actual knowledge about the topic. 25 Further supporting the idea that misperceptions still exist within healthcare professionals and patients and families. More work is needed to increase awareness of palliative care and hospice care among interdisciplinary providers and the general population.21,26 In the absence of trained professionals who are comfortable explaining patients’ options for palliative and hospice care, the promotion of personal goal-aligned care will likely remain in a liminal state.10,20,23,26

Study purpose

Masters et al. 27 reviewed statewide data from an end-of-life survey in Nebraska over four survey waves in 2003, 2006, 2011, and 2017. They found family and nonhealthcare providers are more often consulted about discussions about serious illness and end-of-life care than healthcare providers. While the level of knowledge of nonhealthcare professionals was unknown, respondents viewed them as reliable sources of information. These professionals, including attorneys, financial planners, and even clergy were selected for their perceived expertise in the discussion of wishes as well as the execution of necessary healthcare directive forms. 27 Knowing of this reliance on nonhealthcare professionals remains important when charting a strategy for discussing the benefits of palliative care among those with serious illness and the persons with whom they look to in decision-making. Nonhealthcare professionals’ awareness of what palliative care offers those with serious illnesses and those working in the healthcare field is vital.

The purpose of this secondary analysis is to explore and compare the knowledge, values, and practices of community-dwelling adults nineteen years and older about serious illness and end-of-life healthcare options. We explore the results of a fifth wave of a statewide survey examining Nebraskans’ comprehension and engagement around end-of-life planning and how these results can inform ways to best communicate and market the benefits of palliative care and clarify its distinction from hospice care.

Methods

Survey overview

In 2022, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Bureau of Sociological Research 28 contracted with the Nebraska Hospice and Palliative Care Association 29 to prepare, and distribute a survey, and enter the survey data for a random sample of Nebraskans ⩾19 years of age (19 is the age of majority in Nebraska). The data from this survey are the fifth in a series of five survey waves (2003, 2006, 2011, 2017, and 2022) that have been administered to explore Nebraskans’ knowledge, beliefs, and behavior surrounding their end-of-life wishes. Survey items are a continuation of the initial survey distributed in 2003 with some modifications to reflect current events such as COVID-19 and the use of terms such as POLST (Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment). Examples of survey questions were ‘Have you heard of hospice services?’, ‘Do you know the difference between hospice and palliative care?’ Some questions tested the respondents’ knowledge, such as ‘Does Medicare pay for palliative care/hospice services?’ Responses to questions were ‘yes/no’, multiple choice, and some free text responses (comments, not reported in this quantitative results paper). The Nebraska Hospice and Palliative Care Association 29 made the data available to us in a de-identified format for our secondary analysis.

Data were collected between July and September 2022 with invitations sent to a sample of Nebraskans 19 years of age and older in each of the six behavioral health regions of Nebraska to ensure adequate representation across the state. No weighting was used for oversampling for race or ethnicity. A total of 3000 households were sampled. A total of 635 people completed the survey for a response rate of 21%.

To ensure a probability sample, in each sampled household, the adult with the next closest birthday was asked to complete the survey. Respondents were provided with two options for completing the survey: online Qualtrics survey or on paper. As a secondary analysis, this study was determined to be exempt by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The data source for the survey was treated as an evaluation and did not require IRB approval. The reporting of this study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement 30 (Supplemental File).

Data analysis

All survey measures were initially summarized using means, standard deviations, and ranges for continuous measures and frequencies and percentages for categorical measures. Comparisons of continuous measures over levels of a two-level categorical variable were made using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. In most cases, comparisons of categorical measures over levels of another categorical measure were evaluated using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as necessary. To test trends in proportions of a dichotomous measure across ordered levels of another categorical measure, we used Cochran–Armitage trend tests. A primary outcome was defined as respondents’ answers to ‘Do you know the difference between hospice and palliative care?’ Responses were dichotomized into ‘Yes’ versus ‘No’ or ‘Not sure’. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify respondent characteristics associated with thinking that they knew the difference.

The univariable models allowed for assessment of the association between each independent variable and the outcome measure individually while the multivariable models evaluated these associations while adjusting for (or controlling for) possible effects of other independent variables. These models were run with the assumptions common to linear models of this sort, namely that all observations are independent, the set of independent variables in multivariable models were not substantially multicollinear, and there exists a linear association between each independent variable and the log odds of the outcome measure. Each model was run using the PROC LOGISTIC procedure in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Additional similar models were used to examine who was most likely to have completed an advanced directive. As a person was counted as having completed a directive if they responded that they had completed either ‘A Health Care Power of Attorney (HCPA) in which you name someone to make decisions about your health care in the event you become incapacitated’ or ‘A living will in which you state the kind of health care you want or don’t want under certain circumstances’. All analysis was completed using SAS 9.4 and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

There were 635 community-dwelling people who provided usable responses to the survey but varying levels of item nonresponse and skip patterns lead to differing numbers of responses for each question. Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of those who answered a question about knowing the difference between hospice and palliative care by whether they claimed to know the difference. Focusing on only nonmissing responses to individual items (number missing for each item is found in Table 1), the sample had a mean age of 60.9 years (SD 16.7 years), was 66% female, and 94% non-Hispanic white. Over half (60%) were married or in a domestic partnership and most (78%) lived alone or with just one other person. About a quarter (27%) had household incomes between $40,000 and $74,999, while almost half (47%) had incomes above that range. Most (79%) had attended at least some college or technical training.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Demographic Questions/Characteristics | Total (N = 618) | Know the difference between hospice and palliative care | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 224) | No (N = 394) | |||

| What was your age at your last birthday? | ||||

| N (missing) | 580 (38) | 205 (19) | 375 (19) | 0.46 a |

| Mean (SD) | 60.9 (16.7) | 60.4 (15.9) | 61.2 (17.1) | |

| Five-level age groups, n (%) | 0.466 b | |||

| 19–35 | 68 (11.7) | 25 (36.8) | 43 (63.2) | |

| 36–49 | 69 (11.9) | 22 (31.9) | 47 (68.1) | |

| 50–64 | 167 (28.8) | 63 (37.7) | 104 (62.3) | |

| 65–79 | 209 (36.0) | 79 (37.8) | 130 (62.2) | |

| 80–99 | 67 (11.6) | 16 (23.9) | 51 (76.1) | |

| Missing | 38 | 19 | 19 | |

| Age 65 or older? n (%) | 0.657 c | |||

| Yes | 276 (47.6) | 95 (34.4) | 181 (65.6) | |

| No | 304 (52.4) | 110 (36.2) | 194 (63.8) | |

| Missing | 38 | 19 | 19 | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.003 c | |||

| Male | 195 (33.7) | 54 (27.7) | 141 (72.3) | |

| Female | 384 (66.3) | 154 (40.1) | 230 (59.9) | |

| Missing | 39 | 16 | 23 | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.679 d | |||

| NH White | 544 (93.8) | 197 (36.2) | 347 (63.8) | |

| NH Black | 6 (1.0) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Hispanic | 19 (3.3) | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | |

| Other | 11 (1.9) | 4 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) | |

| Missing | 38 | 17 | 21 | |

| Race condensed, n (%) | 0.306 c | |||

| NH White | 544 (93.8) | 197 (36.2) | 347 (63.8) | |

| Other | 36 (6.2) | 10 (27.8) | 26 (72.2) | |

| Missing | 38 | 17 | 21 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.042 c | |||

| Single/never married | 66 (11.3) | 14 (21.2) | 52 (78.8) | |

| Married/domestic partnership | 350 (60.0) | 136 (38.9) | 214 (61.1) | |

| Widowed | 94 (16.1) | 35 (37.2) | 59 (62.8) | |

| Divorced/separated | 73 (12.5) | 23 (31.5) | 50 (68.5) | |

| Missing | 35 | 16 | 19 | |

| Household income, n (%) | <0.001 c | |||

| Less than $10,000 | 18 (3.3) | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 48 (8.9) | 9 (18.8) | 39 (81.3) | |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 96 (17.8) | 35 (36.5) | 61 (63.5) | |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 147 (27.3) | 38 (25.9) | 109 (74.1) | |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 89 (16.5) | 39 (43.8) | 50 (56.2) | |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 87 (16.1) | 40 (46) | 47 (54) | |

| $150,000+ | 54 (10) | 27 (50) | 27 (50) | |

| Missing | 79 | 31 | 48 | |

| Household size is 1 or 2, n (%) | 0.039 b | |||

| Yes | 450 (77.7) | 151 (33.6) | 299 (66.4) | |

| No | 129 (22.3) | 56 (43.4) | 73 (56.6) | |

| Missing | 39 | 17 | 22 | |

| What is the highest level of education that you completed? n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| Less than high school | 10 (1.7) | 3 (30) | 7 (70) | |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 111 (19.1) | 24 (21.6) | 87 (78.4) | |

| Some college or technical training | 192 (33) | 67 (34.9) | 125 (65.1) | |

| College graduate (4 years) | 161 (27.7) | 62 (38.5) | 99 (61.5) | |

| Postgraduate or professional degree | 108 (18.6) | 52 (48.1) | 56 (51.9) | |

| Missing | 36 | 16 | 20 | |

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Cochran–Armitage trend test.

Chi-square test.

Fisher’s exact test.

NH, non-Hispanic; SD, standard deviation.

Asking about knowing the difference between hospice care and palliative care reveals a lack of understanding among respondents. Of the 618 who responded to this question, only 224 (36%) said that they knew the difference between hospice and palliative care, with the remaining 64% either not knowing the difference or being unsure of the difference. While 97% (n = 616/633) had heard a little or a lot about hospice care, only 50% (309/616) of respondents had heard a little or a lot about palliative care. When asked how interested they would be to hear more about hospice care or palliative care, 40% were very or somewhat interested in learning more about hospice care and 42% were very or somewhat interested in learning more about palliative care. When asked where people would prefer to receive care, 91% preferred to receive hospice care at home and 88% of respondents preferred to receive palliative care at home.

Several characteristics defined those who knew the difference between hospice and palliative care. Those who were female, married, in a domestic partnership, or widowed, with higher incomes, higher education, or living in larger households, were more likely to say that they knew the difference between palliative care and hospice care, compared to their counterparts with other characteristics.

When examining the logistic regression models in Table 2, sex, marital status, household income, household size, and education level were all significant in univariable models of claiming to know the difference. Those who self-identified (subjective) in poor health, who arguably would benefit most from palliative care, did not report knowing the difference more frequently than those who identified themselves as in fair, good, or excellent health. When these measures were all evaluated in a single multivariable model, only sex and household income remained significant.

Table 2.

Logistic regressions for knowing the difference between hospice and palliative care.

| Odds of knowing the difference between hospice and palliative care versus not | Univariable OR (95% CI) | p Value | Multivariable OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What was your age at your last birthday? | 0.997 (0.987, 1.007) | 0.585 | ||

| Five-level age groups | 0.274 | |||

| 19–35 | 0.957 (0.543, 1.686) | 0.878 | ||

| 36–49 | 0.77 (0.432, 1.373) | 0.376 | ||

| 50–64 | 0.997 (0.655, 1.517) | 0.988 | ||

| 65–79 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 80–99 | 0.516 (0.276, 0.967) | 0.039 | ||

| Age 65 or older? | ||||

| Yes | 0.926 (0.658, 1.302) | 0.657 | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.572 (0.393, 0.832) | 0.003 | 0.589 (0.389, 0.892) | 0.013 |

| Female | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Race | 0.648 | |||

| NH White | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| NH Black | 0.352 (0.041, 3.037) | 0.343 | ||

| Hispanic | 0.629 (0.223, 1.773) | 0.381 | ||

| Other | 1.007 (0.291, 3.481) | 0.992 | ||

| Race condensed | ||||

| NH White | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Other | 0.678 (0.32, 1.434) | 0.309 | ||

| Marital status | 0.001 | 0.318 | ||

| Single/never married | 0.424 (0.226, 0.794) | 0.007 | 0.715 (0.352, 1.45) | 0.352 |

| Married/domestic partnership | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Widowed | 0.933 (.583, 1.494) | 0.774 | 1.528 (0.817, 2.859) | 0.185 |

| Divorced/separated | 0.724 (.422, 1.24) | 0.24 | 0.989 (0.532, 1.838) | 0.972 |

| Household income | 0.001 | 0.02 | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 1.103 (0.369, 3.299) | 0.861 | 1.84 (0.556, 6.089) | 0.318 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 0.662 (0.293, 1.493) | 0.32 | 0.802 (0.332, 1.935) | 0.623 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 1.646 (0.944, 2.87) | 0.079 | 1.831 (0.981, 3.42) | 0.058 |

| $40,000–$74,999 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 2.237 (1.28, 3.91) | 0.005 | 2.279 (1.265, 4.107) | 0.006 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 2.441 (1.392, 4.276) | 0.002 | 2.395 (1.303, 4.4) | 0.005 |

| $150,000+ | 2.868 (1.499, 5.488) | 0.002 | 2.393 (1.179, 4.856) | 0.016 |

| Household size is 1 or 2 | ||||

| Yes | 0.658 (0.442, 0.981) | 0.04 | 0.587 | |

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| What is the highest level of education that you completed? | 0.002 | 0.107 | ||

| Less than high school | 0.684 (0.171, 2.745) | 0.593 | 0.380 (0.04, 3.654) | 0.402 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 0.44 (0.254, 0.765) | 0.004 | 0.496 (0.257, 0.954) | 0.036 |

| Some college or technical training | 0.856 (0.554, 1.322) | 0.483 | 0.840 (0.513, 1.378) | 0.49 |

| College graduate (4 years) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Postgraduate or professional degree | 1.483 (0.905, 2.428) | 0.118 | 1.29 (0.749, 2.221) | 0.358 |

| In general, how would you rate your health right now? | 0.32 | |||

| Very good health | 1.455 (0.979, 2.163) | 0.064 | ||

| Good health | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fair health | 1.106 (0.699, 1.75) | 0.668 | ||

| Poor health | 1.276 (0.407, 4.003) | 0.676 | ||

CI, confidence interval; NH, non-Hispanic; OR, odds ratio.

A breakdown of which individuals are most likely to be trusted and preferred sources for information and conveying wishes are found in Table 3(a, c). When asked who a respondent would trust and prefer to initiate, discuss, and/or provide information about end-of-life issues, respondents were more likely to select family members and then a primary care physician as noted in Table 3(a, b). When asked who they had discussed their wishes for end-of-life care, respondents indicated talking with family (spouse/partner, children, other family) or a lawyer more often than discussing wishes with a primary care physician as noted in Table 3(c). The mean age of the respondents implies most children are adults.

Table 3.

Preferred sources of information regarding end-of-life issues (N = 635).

| Sources | N (%) |

|---|---|

| (a) Who would you want to initiate conversation with you about end-of-life issues? (mark all that apply) | |

| Children | 355 (56) |

| Spouse or partner | 346 (55) |

| Other family | 194 (31) |

| Primary care physician | 187 (29) |

| Lawyer | 139 (22) |

| Specialty physician | 123 (19) |

| Clergy or other religious | 120 (19) |

| Financial planner/insurance agent | 84 (13) |

| Friends | 76 (12) |

| No one | 44 (7) |

| Other | 7 (1) |

| (b) Who would you trust to provide information on end-of-life issues? (mark all that apply) | |

| Children | 346 (55) |

| Spouse or partner | 328 (52) |

| Primary care physician | 268 (42) |

| Lawyer | 229 (36) |

| Other family | 193 (30) |

| Specialty physician | 192 (30) |

| Clergy or other religious leader | 145 (23) |

| Financial planner/insurance agent | 110 (17) |

| Friends | 82 (13) |

| No one | 15 (2) |

| Other | 8 (1) |

| (c) With whom have you talked about your wishes for care at the end of your life? (mark all that apply). | |

| Spouse or partner | 338 (53) |

| Children | 285 (45) |

| Other family | 188 (30) |

| Lawyer | 125 (20) |

| No one | 95 (15) |

| Friends | 64 (10) |

| Primary care physician | 48 (8) |

| Financial planner/insurance agent | 33 (5) |

| Clergy or other religious leader | 24 (4) |

| Other | 11 (2) |

Finally, respondents reported on whether they had completed a healthcare directive, with 322 (53%) indicating they had completed some type of directive. Table 4 shows that those least likely to complete a healthcare directive are younger, single, and/or identify themselves as having poor health. Additionally, 95 (15%) of respondents had spoken to no one about the sort of care they would like to receive at the end.

Table 4.

Persons most and least likely to complete a healthcare directive.

| Persons most likely to complete a healthcare directive (living will/durable power of attorney for healthcare) | Persons least likely to complete a healthcare directive (living will/durable power of attorney for healthcare) |

|---|---|

| Older (80+ year of age) | Younger (19–35 years of age) |

| Widowed | Single or never married |

| Very good health | Poor health |

| Living in a one- or two-person household | Living in a multi-person household |

| College education or higher | High school education or less |

Discussion

An aging population, along with a concomitant increase in the prevalence of chronic conditions underscores the need and value of discussing care options with people with serious illnesses who would benefit from comforting and supportive measures. A call by national stakeholders identifies early and universal palliative care access among seriously ill and at-risk groups10,26,31 as a crucial next step. However, the field of palliative care currently faces two significant barriers, namely a lack of general awareness, and commonly held misconceptions about palliative care services.23,32 In our secondary analysis, while half of respondents said they had heard a little or a lot about palliative care, a majority (64%) either did not know the difference or were not sure of the difference between palliative care and hospice care. Comparatively, one study found as little as 29% of US adults indicated that they knew what palliative care was, and of those only 13% had knowledge that did not include some type of misconceptions. 16 Thus, even when a person says they have a general awareness of what palliative care is, there is a significant risk that awareness contains misconceptions about actual services.

Our study highlights the importance of educating people who are at-risk of suffering due to lack of knowledge about and documentation of their wishes for palliative care. Characteristics of those at greatest risk for deficient palliative care understanding include being male, not married, lower education, limited income, and living in a small household. Notably, these characteristics are similar to people who reported not having a documented advance directive. It is without question that those in poor health, low income, and lacking social support would benefit greatly from palliative care and having documented healthcare decisions. However, these may also be barriers to seeking out or accessing services.10,26,31 This is an important discovery as it highlights indicators and vulnerabilities of uninformed persons with respect to current and future healthcare needs including access to palliative care beyond end-of-life care.

Notably, those who rated their own health as poor did not report knowing the difference between palliative care and hospice more frequently than those who rated their own health as fair, good, or excellent. Arguably, clinicians should pay particular attention to persons in poor health, explaining to them the difference between palliative care and hospice. This was not the case. Attention to self-rated health is essential: self-rated health is an independent predictor of mortality, regardless more specific health status parameters and covariates that predict mortality. 33 Self-rated health also predicts morbidity. 34 Potentially, not only physical health problems contribute to poor self-rated health but also socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, and psychosocial factors, such as social isolation and loneliness. Positive but small association between income and self-rated health has been found. 35 Similarly, individuals who perceive themselves as lonely are less likely to rate their health as good, very good, or excellent, and they report a greater number of chronic conditions. 36 Clinicians may use self-rated health questionnaires to offer advance care planning discussions, focusing especially on those who rate their health as poor.

Additionally, our findings reveal people are interested in learning more about palliative care and hospice care. Given respondents tendency to look to spouses/partners or children to be sources of support, finding a way to provide palliative care education/information to all persons in each patient’s support network is critical as they are seen as go-to sources to start, discuss, and/or provide information related to healthcare options. We also note that educating healthcare professionals is equally important, as 42% of respondents would trust a primary care physician to provide information about serious illness and end-of-life care options. People are also interested in receiving palliative care and/or hospice care in the home. Yet, if their wishes are not made known, the possibility of this happening is left to chance. Advance care planning discussions are an opportune time to address both the need for palliative care education and documentation of patients’ values and wishes.

Advance care planning

Advance care planning discussions support personal goal-aligned end-of-life care through education of aging adults about and documentation of their wishes for life-sustaining treatments and other decisions surrounding death.10,20 Advance care planning initiation promotes earlier use of palliative care when documented early or prior to a serious diagnosis.10,21,24 These advance directives are often made in the interest of prioritizing one’s quality of life over quantity of life through palliation and in support of loved ones who must make decisions when a patient is no longer able.21,24

The value of having these discussions is an area noted by the American Geriatrics Society in their 2020 position statement. 37 And it is an area that is gaining more attention as findings from other global health events such as the 1918 influenza pandemic have revealed the vulnerability of persons of all ages with chronic conditions to be more susceptible to fast moving disease states and infection. 37 While the 1918 influenza pandemic occurred over a century ago, historical perspective informs current healthcare. Wissler and DeWitte 38 discovered that frail individuals – specifically those with the evidence of the most prior environmental, social, and nutritional stress – had the highest mortality risk. Thus, frailty, used as a proxy of prior accumulated stress, rather than age alone, was associated with the highest mortality risk. 38 This finding, placed in the context of advance directives, indicates that clinicians should discuss advance care planning with persons of all ages, rather especially those who are frail and with evidence of severe environmental, social, and nutritional stress. Furthermore, accumulating chronic stress and resultant frailty in younger adults should prompt not only discussions about advance care planning but also about improving these younger adults’ health.

Thus, recognition of an individual as in need of an advance care planning discussion serves as dual purpose: to educate about end-of-life care and also to make a care plan to reduce frailty and improve health status. Such use of advance care planning conversation may mitigate younger adults’ fear and reluctance to speak about end of life and instead use the advance care planning discussion as a teachable moment to speak about the ways to promote health. Potentially, younger adults with accumulating environmental, social, and nutritional stress may not see themselves as frail and may be surprised when advance care planning is introduced. This situation may prompt clinicians to both discuss advance care planning and also illuminate ways in which accumulating chronic stress and frailty endanger this younger person’s health. Younger adults, in fact, wish to have more information on advance care planning. 39 Potentially, illuminating younger adults’ risks, such as chronic stress, may serve as a conversation starter targeting both advance care planning and initiating a care plan for reducing health risks, mitigating chronic stress, and decreasing frailty.

The considerable number of COVID-19 infections and deaths continues to focus attention on the need for many adults to make decisions about the future life-saving measures they want for themselves or their loved ones. 20 When an adult is hospitalized with a serious or terminal illness like COVID-19, the absence of advance care planning documentation places distressed and potentially uninformed family members in the position of making decisions about life-saving treatments that may be incongruent with the patient’s wishes. Instead of dying at home near family under the specialized care of hospice services, many adults are dying on ventilators or suffering from the consequences of futile and brutal resuscitation efforts. 20 Though respondents indicated a preference to receive care and die in their home, the pandemic limited this option for many who remained in the confines of hospital care for the protection of others. That most 2022 respondents (53%) had initiated healthcare advance directives represented an increase in comparison to previous surveys 27 and the previously reported national average of 37%. 40 It is possible that this increase was a result of the widespread and highly publicized futility of care witnessed during the pandemic. Nebraska was like other states faced with high mortality among its older population and those from marginal communities. Those with multiple health problems going into the pandemic were also those most at risk and in a position to think about care plans.

It was detected that older adults (80 years old), widowed, in good health, and college educated were more likely to have completed a health directive. Those who have lost a spouse or who are older adults and have likely witnessed the death of a loved one are more likely to recognize the importance of advance care planning. Experiencing the loss of someone close may have served as an educator and motivator in ensuring documentation of their own wishes for end-of-life decision-making. In contrast, demographic data indicates that those who are younger, less educated, with lower income, and in poorer health are more likely to have encountered barriers to advance care planning. The cost of services and limited awareness of the importance of planning behavior may impede health directive completion among these individuals and those in underrepresented groups. The proposed ‘Improving Access to Advance Care Planning Act’ (H.R. 8840/S. 4873) will remove cost-sharing for these services, increase the types of professionals that can bill for advance care planning conversations, and evaluate advance care planning under the Medicare program. Such an incentive may prompt providers to think about these conversations more intentionally and to bring awareness about and normalize these conversations for those who are of limited means and those who have the resources but have not acted on or engaged in such discussions.

While funding is available through such avenues as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid to support and bill for conversations about preferred care for serious illness or end of life, researchers note the low use of this option due to confusion, discomfort, and pessimism about the benefits of such discussions. 31 However, when healthcare providers are trained on the value and method for how to have healthcare discussions, advance care planning encounters, and subsequent billing for this effort increases. 41 They are also more likely to engage in conversations with patients about their wishes because they have taken the time and effort to think intentionally about serious illness and end-of-life care. 17

As noted in our study and other research, the public and healthcare professionals lack understanding of what palliative care offers.22,23,25 There is value in having a coordinated effort in communicating care options for serious illness and end-of-life care. If we continue to educate in silos, different professionals along with members of the public will fail to come together in providing and receiving coherent care. A community-based approach is necessary to show how and when to communicate about the differences and commonalities of palliative care and hospice care. It is important for healthcare professionals and non-healthcare professionals such as lawyers, financial planners, and clergy to understand and communicate these differences when having advance care planning discussions.

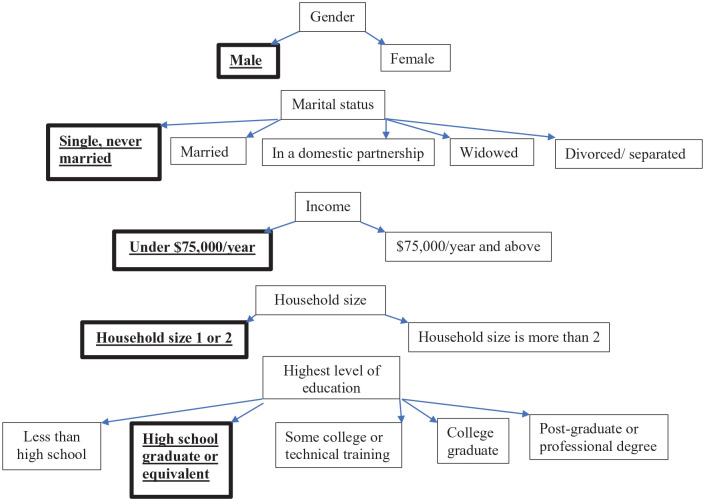

In this study, we found several demographic characteristics where there was a statistically significant lower likelihood of not knowing the difference between palliative care and hospice care and of not having documented advance directives. While healthcare providers need to educate all patients who may need palliative care about the difference between palliative care and hospice care, the categories identified in Figure 1 may serve as a marker for individuals in need of extra attention. Considering time and resource constraints in busy primary care practices, clinicians may plan dedicated time and leverage interprofessional care teams (e.g. social workers, registered nurses, case managers, and chaplains) to educate these persons.

Figure 1.

Individuals who were statistically significantly less likely to know the difference between palliative care and hospice (highlighted).

Limitations

This secondary data analysis is limited to Nebraska residents 19 years of age and older and may not be generalizable beyond those persons completing the survey. A low survey response rate (21%) and variable response rate on some items throughout the survey are also limitations. Whether completing on paper (n = 490) or electronically (n = 145), respondents were not forced to complete all survey items. Reasons for noncompletion of some items is unknown, but may be related to survey fatigue, overlooking questions, or skipping items due to uncertainty or personal reasons. Also, given respondents were mainly white and only English-speaking, the results are limited by this group’s homogeneity. Further surveys with purposive sampling methods are warranted to provide insight from a more diverse and global sample. Likewise, the response rate was 21%, indicating that most people targeted did not respond. Likely, their knowledge of palliative care and hospice may be worse for various reasons (e.g. no interest in research participation, potential apprehension of survey completion among immigrants, mistrust of research, not understanding the purpose of research, low health literacy).

The survey results reflect mostly self-reports and not solely knowledge assessment (with the exception of a few questions, such as about Medicare payment for palliative care and hospice). Future surveys would benefit from a knowledge component as this may reveal further misunderstandings of what palliative care can offer. Analysis of those who know the difference between hospice and palliative care relied on self-report items of participant knowledge. Future studies should include more objective assessment of participant knowledge and compare it to self-report data. Additionally, the 2022 survey contained some new items and response options when compared to previous survey iterations. This limited the possibility of conducting comparative analysis and assessing change over time.

Next steps

Clarifying terminology is paramount to encouraging people (patients, families, and clinicians) to see the value of palliative care as distinct yet available when needed within or outside of hospice care services. The introduction of new terminology such as nonhospice palliative care 18 may be one such step. While this terminology was not used for this survey, future surveys would benefit from a revision in terminology. Additionally, understanding that palliative care is a basic human right is also vital, especially for those who may be less familiar with what this form of healthcare has to offer. 31 A federal initiative, the Palliative Care and Hospice Training Education Act (S. 4260), has been proposed to improve access to quality palliative care. Such legislation offers the potential for improving universal access to palliative care through workforce development and increased awareness. In response to noted palliative care barriers, some academics and professionals in the field have also suggested that a rebranding effort may be necessary to move beyond these barriers.42,43 Such recommendations focus on breaking the stigmas that tangle palliative care with end of life. In doing so, the hope is that palliative care could be rebranded to represent services that are integrated early in the chronic disease process leading to best care outcomes. They may also encourage the use of hospice care earlier when end-of-life care is needed.

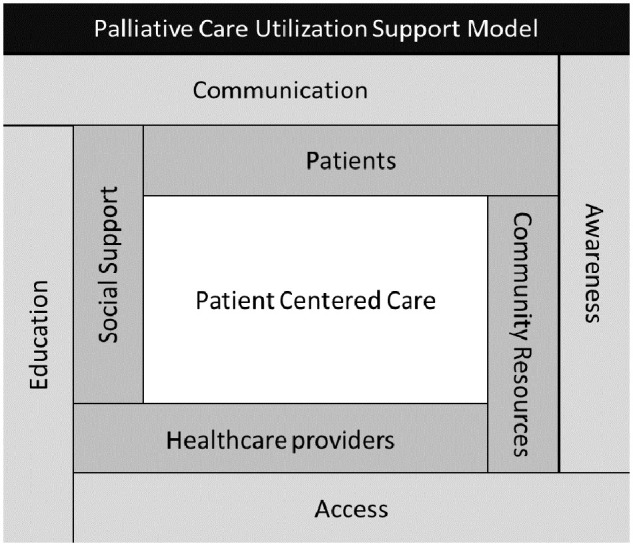

Additionally, a more intentional approach to incorporating palliative care into the overall planning for a patient with serious illness may be of value. As newer palliative care models continue to holistically address individual patient needs, comprehensive approaches to better understand what influences a patient are vital. Such approaches may allow for a more robust discussion around patient disease trajectory and management goals keeping patient-centered care at the forefront of these efforts. Figure 2 is an example of a possible integrated approach to communication about palliative care. This considers both where the communication is coming from and what supports are in place to ensure effectiveness. For example, patients, healthcare providers, social support sources, and community resources may play an integral role in the messaging around palliative care services. These message sources are affected by their own education, awareness, communication method, and access to said services, which influences the patient’s decision-making process. Viewing the communication process from this lens could allow a more comprehensive approach to a complex and vital messaging care opportunity.

Figure 2.

A model of support for persons with serious illness.

Normalizing the process is also a crucial next step. Normalizing the process refers to finding ways to engage persons outside the healthcare arena to start conversations about end-of-life care. 27 This can also include incorporating discussions about care for persons with serious illness into advance care planning conversations. Our study continues to highlight a reliance on persons other than healthcare providers for guidance with healthcare options and decision-making. Input and support are often sought from family members, including spouses and adult children. Respondents also look to lawyers, financial planners/insurance agents, and members of clergy or religious groups for direction. This is in addition to a physician or healthcare provider for guidance and insight. Our research continues to highlight that there are more people involved in discussions than first thought.

Conclusion

The findings from this analysis focus on surveys completed during the time of a global pandemic (2022) and offer unique insight into who is planning for end-of-life care and who may be missed living in the central part of the United States. In 2021, COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death in Nebraska, behind only heart disease and cancer. 44 With this survey offered in 2022, there is a historical bias of a likely unprecedented (in the lifetime of survey respondents’) pandemic possibly increasing respondents’ awareness about hospice and palliative care. Potentially, exposure to end-of-life care – through respondents’ own or their relatives’ or acquaintances’ healthcare experiences near the end of life – increased respondents’ knowledge about palliative care and hospice. For example, in a study conducted in the Netherlands, researchers discovered that the pandemic illuminated the importance of high-quality end-of-life care and what end-of-life care entails.45,46 Thus, potentially, this survey respondents were ‘sensitized’ by the pandemic in a unique and unprecedented way: the job of clinicians who are supposed to educate patients and families about end-of-life care was done by the global pandemic and possibly the media. Still, the majority of respondents did not know or were unsure about the difference between palliative care and hospice, indicating that education must be done by healthcare professionals rather than happen due to global events.

Another unique characteristic in Nebraska is the state’s rurality, with nearly 35% of the state’s population residing in rural areas. 47 Rural areas face shortage of healthcare professionals 48 and are marked by residents’ lower educational attainment 48 and lower socioeconomic status. 49 These factors may make Nebraskans less knowledgeable about palliative care and hospice, indicating the need for healthcare professionals to target rural residents with their education.

In our study, we found that younger single men, those in poor health, those with lower income, and/or lower level of education may be less likely to know about palliative care or have planned for end-of-life healthcare decisions. Thus, this target demographic would especially benefit from information sharing and clarification about palliative care and hospice. Finding ways to encourage them to think about and act on healthcare directives is important, especially when health status can change dramatically in serious illness and affect one’s ability to express their wishes.

Regardless of age or income, we found 15% of respondents had spoken to no one about their wishes for care. Events such as the global pandemic from 2020 to 2022 highlight the dramatic turn a person’s health can take and the need to have someone or something guide the decision-making process with a clear understanding of palliative care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pcr-10.1177_26323524241263109 for Providing clarity: communicating the benefits of palliative care beyond end-of-life support by Julie L. Masters, Patrick W. Josh, Amanda J. Kirkpatrick, Mariya A. Kovaleva and Harlan R. Sayles in Palliative Care and Social Practice

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marilee Malcom and the Nebraska Hospice and Palliative Care Association for providing us access to data from the 2022 Nebraska End-of-Life Survey along with the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Bureau of Sociological Research (BoSR).

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Julie L. Masters  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4247-0540

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4247-0540

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Julie L. Masters, Department of Gerontology, University of Nebraska Omaha, 312 Nebraska Hall, 901 North 17 Street, Lincoln, NE 68588-0562, USA.

Patrick W. Josh, Department of Gerontology, University of Nebraska Omaha, Omaha, NE, USA

Amanda J. Kirkpatrick, Creighton University College of Nursing, Omaha, NE, USA

Mariya A. Kovaleva, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Nursing, Omaha, NE, USA

Harlan R. Sayles, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health, Omaha, NE, USA

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable as this was a secondary data analysis and was waived for approval by the Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication: Not applicable as this was a secondary data analysis.

Author contributions: Julie L. Masters: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Patrick W. Josh: Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing – original draft.

Amanda J. Kirkpatrick: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Mariya A. Kovaleva: Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Harlan R. Sayles: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Nebraska Hospice and Palliative Care Association and the Terry Haney Chair of Gerontology provided funding for this project

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The data for this project is available through the Nebraska Hospice and Palliative Care Association.

References

- 1. Graham F, Clark D. The changing model of palliative care. Medicine 2008; 36: 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hugar LA, Geiss C, Chavez MN, et al. Exploring knowledge, perspectives, and misperceptions of palliative care: a mixed methods analysis. Urol Oncol 2023; 41: 329.e19–327.e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferrell B, Sun V, Hurria A, et al. Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 50: 758–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baumann AJ, Wheeler DS, James M, et al. Benefit of early palliative care intervention in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting liver transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015; 50: 882–886.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quinn KL, Shurrab M, Gitau K, et al. Association of receipt of palliative care interventions with health care use, quality of life, and symptom burden among adults with chronic noncancer illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2020; 324: 1439–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yadav S, Heller IW, Schaefer N, et al. The health care cost of palliative care for cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28: 4561–4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathew C, Hsu AT, Prentice M, et al. Economic evaluations of palliative care models: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaufman BG, Granger BB, Sun JL, et al. The cost-effectiveness of palliative care: insights from the PAL-HF trial. J Card Fail 2021; 27: 662–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Center to Advance Palliative Care. About palliative care, https://www.capc.org/about/palliative-care/ (n.d., accessed 27 April 2024).

- 11. Dionne-Odom JN, Ornstein KA, Kent EE. What do family caregivers know about palliative care? Results from a national survey. Palliat Support Care 2019; 17: 643–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patel P, Lyons L. Examining the knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of palliative care in the general public over time: a scoping literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020; 37: 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trivedi N, Peterson EB, Ellis EM, et al. Awareness of palliative care among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. J Palliat Med 2019; 22: 1578–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaminski A. Let’s talk about dying: an educational pilot program to improve providers’ competency in end-of-life discussions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2023; 40: 688–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cardenas V, Rahman A, Zhu Y, et al. Reluctance to accept palliative care and recommendations for improvement: findings from semi-structured interviews with patients and caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2022; 39: 189–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flieger SP, Chui K, Koch-Weser S. Lack of awareness and common misconceptions about palliative care among adults: insights from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35: 2059–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams JL, Doolittle B. Holy simplicity: the physician’s role in end-of-life conversations. Yale J Biol Med 2022; 95: 399–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beasley AM, Bakitas MA, Ivankova N, et al. Evolution and conceptual foundations of nonhospice palliative care. West J Nurs 2019; 41: 1347–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brighton LJ, Koffman J, Hawkins A, et al. A systematic review of end-of-life care communication skills training for generalist palliative care providers: research quality and reporting guidance. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54: 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McAfee CA, Jordan TR, Cegelka D, et al. COVID-19 brings a new urgency for advance care planning: implications of death education. Death Stud 2020; 46: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. Palliative care council, https://dhhs.ne.gov/Pages/About-Palliative-Care.aspx (2024, accessed 27 April 2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. Carey ML, Zucca AC, Freund MAG, et al. Systematic review of barriers and enablers to the delivery of palliative care by primary care practitioners. Palliat Med 2019; 33: 1131–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crimmins RM, Elliott L, Absher DT. Palliative care in a death-denying culture: exploring barriers to timely palliative efforts for heart failure patients in the primary care setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021; 38: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwak J, Jamal A, Jones B, et al. An interprofessional approach to advance care planning. Am J Hospice Palliat Care 2022; 39: 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taber JM, Ellis EM, Reblin M, et al. Knowledge of and beliefs about palliative care in a nationally-representative U.S. sample. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0219074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, et al. National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines. J Palliat Med 2018; 21: 1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Masters JL, Wylie LE, Hubner SB. End-of-life planning: normalizing the process. J Aging Soc Policy 2022; 34: 641–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. 2023 at a glance. Bureau of Sociological Research, https://bosr.unl.edu/ (n.d., accessed 27 April, 2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nebraska Hospice and Palliative Care Association. Nebraska End-of-Life Survey Report. https://www.nehospice.org/ (n.d., accessed 27 April 2024).

- 30. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observation studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosa WE, Ferrell BR, Mason DJ. Integration of palliative care into all serious illness care as a human right. JAMA Health Forum 2021; 2: e211099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schallmo MK, Dudley-Brown S, Davidson PM. Healthcare providers’ perceived communication barriers to offering palliative care to patients with heart failure: an integrative review. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2019; 34: E9–E18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997; 38: 21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Latham K, Peek CW. Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife U.S. adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2013; 68: 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reche E, König H-H, Hajek A. Income, self-rated health, and morbidity. A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16: 2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Farrell TW, Ferrante LE, Brown T, et al. AGS position statement: resource allocation strategies and age-related considerations in the COVID-19 era and beyond. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68: 1136–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wissler A, DeWitte SN. Frailty and survival in the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2023; 120: e2304545120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kavalieratos D, Ernecoff NC, Keim-Malpass J, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and preferences of healthy young adults regarding advance care planning: a focus group study of university students in Pittsburgh, PA. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yadav K, Gabler N, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults complete any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Affairs 2017; 36: 1244–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Henage CB, McBride JM, Pino J, et al. Educational interventions to improve advance care planning discussions, documentation and billing. Am J Hospice Palliat Care 2021; 38: 355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patra L, Ghoshal A, Damani A, et al. Cancer palliative care referral: patients’ and family caregivers’ perspectives – a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print November 2022. DOI: 10.1136/spcare-2022-003990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hawley P. Barriers to access to palliative care. Palliat Care 2017; 10: 1178224216688887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Key Health Indicators. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/states/nebraska/ne.htm (2023, accessed 2 May 2024). [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zee M, Baghus L, Becqué YN, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on care at the end of life during the first months of the pandemic from the perspective of healthcare professionals from different settings: a qualitative interview study (the CO-LIVE study). BMJ Open 2023; 13: e063267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rural Health Information Hub. Nebraska, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/states/nebraska (2023, accessed 2 May 2024).

- 47. Rural Health Information Hub. Rural healthcare workforce, https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/health-care-workforce (2024, accessed 2 May 2024).

- 48. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural education, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-education/ (2021, accessed 2 May 2024).

- 49. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Medicaid and rural health, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Medicaid-and-Rural-Health.pdf (2021, accessed 20 June 2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pcr-10.1177_26323524241263109 for Providing clarity: communicating the benefits of palliative care beyond end-of-life support by Julie L. Masters, Patrick W. Josh, Amanda J. Kirkpatrick, Mariya A. Kovaleva and Harlan R. Sayles in Palliative Care and Social Practice