Abstract

Purpose:

Topical antihistamines, such as olopatadine hydrochloride, an H1 receptor antagonist, are commonly prescribed for treating allergic conjunctivitis. Drug delivery via eye drops has many deficiencies including a short residence time due to tear drainage via the nasolacrimal duct, which results in a low bioavailability and potential for side effects. These deficiencies could be mitigated by a drug-eluting contact lens such as the recently approved ACUVUE® THERAVISION™ WITH KETOTIFEN which is a daily disposable etafilcon, a drug-eluting contact lens with ketotifen (19 μg per lens). Here, we investigate the feasibility of designing a drug-eluting lens with sustained release of olopatadine for treating allergies using an extended wear lens.

Methods:

Nanobarrier depots composed of vitamin-E (VE) are formed through direct entrapment by ethanol-driven swelling. The drug-loaded lenses are characterized for transparency and water content. In vitro release is measured under sink conditions and fitted to a diffusion control release model to determine diffusivity and partition coefficient.

Results:

In vitro studies indicate that ACUVUE OASYS® and ACUVUE TruEye™ lenses loaded with ∼0.3 g of VE/g of hydrogel effectively prolong olopatadine dynamics by 7-fold and 375-fold, respectively. Incorporation of VE into the lenses retains visible light transmission and other properties.

Conclusion:

The VE incorporation in commercial lenses significantly increases the release duration offering the possibility of antiallergy extended wear lenses.

Keywords: vitamin E, olopatadine hydrochloride, bioavailability, conjunctivitis

Introduction

Allergic Conjunctivitis (AC) or pink eye is an ocular indication which results in conjunctival inflammation from the immunological response to the infiltrated airborne allergens by the mast cells.1,2 The common airborne allergens that initiate an inflammatory response include pollen, animal dander, microscopic dust particulates, and other environmental pollutants.2 These external agents migrate to the conjunctiva via the tear film lake and bind to the IgE antibody- receptor complexes on the conjunctival mast cell surface.1–13 The mast cell-driven inflammation results in allergic reactions including itching, excessive tearing, and conjunctival edema, accompanied by pain. The damage could be more significant in the more severe or undiagnosed cases leading to chronic vasculature damage due to late-stage responses of chemotactic cues/mediators including eosinophil granule proteins.2

According to epidemiologic studies conducted in 2009 by the U.S. Department of Health, ∼1% of all patient visits to primary clinical centers are conjunctivitis-related with estimated annual costs around $377 million to $857 million.14 Most cases of AC are due to seasonal allergies.14 Surveys conducted in 2011 show that AC is prevalent among 15%–20% of the elderly population in the United States with an additional 15% increase in diagnosed cases annually.14 Conjunctivitis among toddlers of age group 4 to 16 is generally accompanied by allergic rhinitis, contributing to wheezing, nasal congestion, and other allergies in addition to the ocular symptoms.15 Currently, AC is commonly treated by ophthalmic drops with a recommended dosage of 1 drop per affected eye, twice a day.16

Therapeutic agents for treating allergy conjunctivitis

The approved treatments for AC are classified into 4 categories, namely antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs), and corticosteroids.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines exert the therapeutic effect by competitive blocking of both H1 and H2 histamine receptors located in the conjunctiva.2,3,12,13,16–20 Topical formulations of H1 blockers that are currently in the market include a pheniramine maleate/naphazoline hydrochloride combination (Opcon A/Naphcon A), olopatadine hydrochloride (Pataday), and levocabastine hydrochloride.18,20–23 These H1 blockers significantly reduce inflammatory symptoms including itching and conjunctival redness.18 Currently, no H2 receptor blockers are approved for ocular use, but experimental trials on cimetidine, an H2 antagonist are underway for ophthalmic use.24

Mast cell stabilizers

Another class of therapeutic ophthalmic agents that effectively treat inflammation is the mast cell stabilizers. The commonly prescribed ones include cromolyn sodium, lodoxamide, and nedocromil. These stabilizers restrain the calcium influx across mast cell membranes thereby preventing degranulation.25–33 Clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of cromolyn sodium assays and noticed the suppression of pollen-induced allergies over 5 weeks. Recent studies have also shown that nedocromil sodium inhibits activation and mediator release from the mast and immune cells, thereby blocking chronic tissue damage in the conjunctiva.23,25 Currently, physicians prescribe a 2% cromolyn sodium ophthalmic formulation for subjects suffering from seasonal AC.

NSAIDs and corticosteroids

NSAIDs offer an alternative to potent steroids and effectively treat AC through inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity, an enzyme ubiquitous for production of inflammatory mediators. Ketorolac, an NSAID from the class of pyrroles is proven to be efficient in suppressing erythema, edema, mucous discharge, and eyelid itching, posttopical application of a 0.25% formulation.34,35 The corticosteroids act through phospholipase A2 inhibition; a primary component is the production of chemical mediators necessary for mast cell degranulation.2,26,36,37

Eye drops are effective in treating AC and other ocular diseases, but the instilled drops are rapidly cleared via drainage through the nasolacrimal duct leading to low bioavailability.38–41 In addition to low bioavailability, the preservatives in eye drops can cause cornea damage, particularly for chronic diseases requiring 1 or more drops each day for a long duration.42–44 The deficiencies of eye drops have led to considerable interest in exploring controlled drug delivery via polymeric systems including conjunctival inserts, punctal plugs,45,46 and contact lenses.47–72 Punctal plugs increase the residence time of the administered drop through tear duct occlusion resulting in increased drug delivery to ocular tissues. These benefits are accompanied by side-effects including excessive tearing, eye irritation, punctal ring rupture, corneal surface abrasion, and suppurative canaliculitis (bacterial infection of the lacrimal gland) limiting their use.46 The conjunctival inserts also have undesirable side effects including blink-driven device expulsion, and eye irritation.

The discomfort and potential for expulsion of the devices can be minimized by using contact lenses, which are safely used by hundreds of millions of wearers. Recently, ACUVUE® THERAVISION™ WITH KETOTIFEN which is a daily disposable etafilcon A drug-eluting contact lens with ketotifen (19 mcg per lens) was approved by the FDA for prevention of ocular itch due to AC. ACUVUE THERAVISION WITH KETOTIFEN is the first and currently only approved drug-eluting contact lens. A downside of commercial lenses including the etafilcon A lens is that the lenses release the drugs rapidly in a few hours owing to their small molecular size. In a recently published study, biomimetic imprinting was utilized to sustain the release of olopatadine from contact lenses.71 In this research study, the feasibility of vitamin-E (VE) barrier integrated contact lens matrices for extended delivery of an H1 blocker antihistamine, namely olopatadine hydrochloride is explored. VE incorporation into the hydrogel matrix leads to formation of nano-sized barriers, retarding drug diffusion through the polymer matrix.51–53,61,64–68 As shown in this and previous studies,51–53,61,64–68 VE can be incorporated into the lens using a simple scalable process involving soaking the lenses in VE-ethanol solution, followed by ethanol extraction by soaking the lens in deionized water.

Experimental Section

Materials

Two commercial contact lenses, namely ACUVUE OASYS® (P = −3.50 diopter, BC = 8.8 mm) and ACUVUE TruEye™ lenses (diopter −3.50, BC = 8.6 mm) were used for this in vitro study. The conjunctivitis medication, olopatadine hydrochloride (≥98%), and the modifier VE (DL-alpha tocopherol, >96%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS 1 × , without calcium and magnesium) was purchased from Mediatech, Inc., (Manassas, VA). Ethanol (200 proof) was purchased from Decon Laboratories, Inc., (King of Prussia, PA). All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Quartz cuvettes used for UV-vis measurements were purchased from Science Outlet.

VE loading into commercial lenses

The commercial ACUVUE OASYS lenses were isolated from the blister packs and immersed in de-ionized water for 30 min to flush out constituents of the packaging solution. The cleansed lenses were isolated PBS medium with a sterile tweezer and blotted with a Kimwipe to remove the residual solution from the lenticular surface. VE was loaded into the hydrogel phase by soaking the lenses in 3 mL of 40 mg/mL VE/ethanol solution for 24 h to achieve 20% (w/w) loading in the OASYS lenses.53,55 The lenses expend significantly in ethanol, which not only allows rapid uptake of VE-ethanol solution but also makes the lenses very soft and fragile. Such processes are commonly used in contact lens industry such as during extraction of unreacted monomer, which suggests that the process can be scaled up despite the fragility of the lens during soaking in ethanol.

After the loading procedure, gels were isolated from the vials, transferred to a 200 mL de-ionized water reservoir, where a soaking duration of 2 h ensured clearance of ethanol contained in the hydrogel phase. The volume of water used in the ethanol extraction can be reduced considerably to minimize the amount of wastewater generated. Additionally, multiple lenses can be processed in the same 200 mL either together or separately. The lenses were isolated again and rinsed with a quick 200-proof ethanol dip of 3–5 s to extract VE deposits adsorbed on the surface of the lenses. The lenses were later rinsed in PBS to shrink the modified lenses to their pre-deformed shape and stored in PBS medium (3 mL) for further experiments. The amount of VE entrapped within the modified lenses were estimated based on difference in dry weights of both VE modified and control lenses. As described in Sekar and Chauhan,65 different loadings of VE were integrated into the control lenses by the same protocol. The diameter of the control lenses upon VE modification increased by 10% with no significant changes induced to the base curvature.

In vitro olopatadine hydrochloride loading into commercial lenses

The commercial ACUVUE lenses were isolated from the PBS medium and blotted with a Kimwipe to remove the residual solution from the surface of the lens. Since olopatadine hydrochloride is hydrophilic, the drug particulate was solubilized in PBS to formulate the uptake medium at drug concentration of 1.5 mg/mL. The drug olopatadine was loaded into control contact lenses (no VE) by soaking them in 3 mL of the uptake medium per lens. The VE modified lenses of different VE loadings were immersed in a batch of 3 mL of drug solution for a prolonged duration up to 50 days to attain equilibration. The drug loading duration must be longer than the release duration to achieve equilibrium during the loading phase. After the loading phase, the lenses were taken out, and the excess drug solution was blotted from the surface of the lens.

In vitro olopatadine release from control and VE modified lenses

The drug-loaded lenses were isolated from the drug solution (uptake medium) and transferred to 3 mL of fresh PBS (release medium) after gentle blotting with a Kimwipe to remove the residual solution on the surface. The dynamic concentration of the drug in the aqueous phase was monitored using UV-Vis absorbance to quantify the partitioned drug.

Transmittance of control, VE, and drug-incorporated commercial lenses

The UV-Vis spectrophotometer (GENESYS™ 10 UV; Thermo Spectronic, Rochester, NY) utilized in this study is equipped with sampling transmittance spectra of the hydrogels in the bandwidth of 190–1100 nm. A three-dimensional (3D) printed construct composed of poly-lactic acid was mounted on to the external cell holder surface. The 3D construct contained a notch to confine the hydrogel lens near the cell holder's aperture. The buffer cleansed soft contact lens (ACUVUE) was carefully mounted beside the aperture without inducing structural damage to the surface. The affixed lens was exposed to a channel normal to the monochromatic UV beam projection axis for spectral recording.

Water content of commercial lenses post-VE and drug incorporation

The percentage of water content in the commercial lenses was determined through differences in mass of hydrated and dried gel samples. The hydrated gels were stored in PBS medium prior measurements and later dried at 60°C in a convection oven to obtain dry gel mass. The equilibrium water content was evaluated as

| (1) |

In vitro model for olopatadine release

To obtain the transport properties of the hydrophilic antihistamine, olopatadine, the in vitro release data was fit a one-dimensional (1D) Fickian diffusion model. Owing to high hydrophilicity of the tested medicament in the aqueous solution and disparity in volume of the reservoir and the lens, perfect sink conditions were assumed to evaluate the distribution coefficient of the drug in the hydrogel phase. The following expression was utilized to evaluate the partition coefficient of olopatadine:

| (2) |

The transport of solute through these polymerized hydrogel materials occur through swelling of the gel, bulk, and surface diffusion. To maintain the model's simplicity, we assume drug diffusion through the hydrogel material to be purely Fickian to facilitate estimation of transport diffusivity of the olopatadine hydrochloride. The drug transport in the lateral direction can be described as

| (3) |

where Cg is the olopatadine concentration in the commercial silicone hydrogel matrix. The boundary and initial conditions for diffusion in the lens matrix are

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where hg is the half-thickness of the lens (∼40 μm for commercial ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses). The boundary condition (4) arises from symmetry of the hydrogel matrix and that in (5) assumes equilibrium between concentration of the olopatadine in the gel matrix and the surrounding formulation present in the aqueous reservoir in the vial (∼3 mL). Owing to low distribution coefficient in the hydrogel phase, drug concentration in the gel's leading edge reduces to zero. To account for the loss of drug concentration in the reservoir due to its influx into the secondary gel phase, a mass balance on the aqueous olopatadine reservoir in the scintillation vial yields the following equation:

| (7) |

where Vw is the volume of olopatadine/PBS solution in the aqueous reservoir whose concentration is negligible during drug transport (perfect sink). An analytical solution is obtained for solute concentration released from the gel matrix by solving equation 3 in conjunction with the boundary conditions (equations 4–6) and the aqueous reservoir mass balance (equation 7). The expression for % mass in the aqueous reservoir is given by

Results and Discussions

Transmittance

The transmittance measurements shown in Fig. 1 were taken at a 1 nm interval in the spectral bandwidth of 190–1100 nm. The spectral bandwidth of 190–1100 nm was chosen to gauge the effect of VE (α-tocopherol) incorporation on the transmittance of the modified lenses. VE incorporation into commercial ACUVUE lenses does not affect the material's ability to transmit visible radiation in the range of 500–700 nm (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Transmittance spectra of an 80 μm thick commercial ACUVUE® OASYS® and ACUVUE TruEye™ control lens and the modified version after VE (α-tocopherol) incorporation. Integration of VE into the lens matrix does not have an impact on transparency of the commercial lenses. VE, vitamin-E.

Water content

Table 1 summarizes the water content of control ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses and the change observed after incorporation of VE in the lens matrix. A 2%–16% reduction in water content of the hydrogels depending on the lens type is observed due to the integration of hydrophobic VE aggregates in the polymer matrix.

Table 1.

Summary of Water Content of Control and Vitamin-E Modified ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye Lenses

| VE loading (aq.phase) (%) | ACUVUE® OASYS® |

ACUVUE TruEye |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 20 | |

| Soaking duration in PBS (hours) | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Hydrated weight (mg) | 31.9 ± 0.5 | 37.6 ± 1.7 | 35.7 ± 0.9 | 38.6 ± 0.1 | 38.4 ± 0.1 | 38.1 ± 0.2 |

| Dry weight (g) | 19.8 ± 0.3 | 25.9 ± 0.4 | 23.5 ± 0.5 | 20.7 ± 0.4 | 20.9 ± 0.3 | 21.7 ± 0.5 |

| Water content (%) | 37.9 ± 0.2 | 34.2 ± 0.9 | 31.8 ± 0.4 | 46.1 ± 0.2 | 45.5 ± 0.9 | 42.8 ± 0.4 |

PBS, phosphate buffered saline; VE, Vitamin-E.

In vitro studies—dynamics of olopatadine release from control lenses

Figure 2 presents the dynamics of olopatadine transport into both commercial ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses, which served as control runs. As described in section 2.3, the control lenses of both compositions were immersed in 1.5 mg/mL olopatadine concentrated PBS solution during the loading phase. The dynamics of drug transport was monitored through concentration measurements of the aqueous reservoir using UV-vis spectrophotometry. It is observed that the unmodified control ACUVUE OASYS lenses release >95% of olopatadine, a dosage of 29 μg in 2–3 h. The 29 μg drug loading is likely adequate for use as daily disposable lens considering that this amount is higher than the ketotifen fumarate loading in the ACUVUE THERAVISION WITH KETOTIFEN and additionally the selectivity of olopatadine hydrochloride is higher than that of ketotifen fumarate or levocabastine hydrochloride for the H1, H2, and H3 receptors.73 However, the loading of 29 μg may not be adequate for extended wear lens with sustained release which is the goal of this work. It is noted though that the mass of drug loaded in the contact lenses can be increased by increasing the drug concentration in the loading solution.

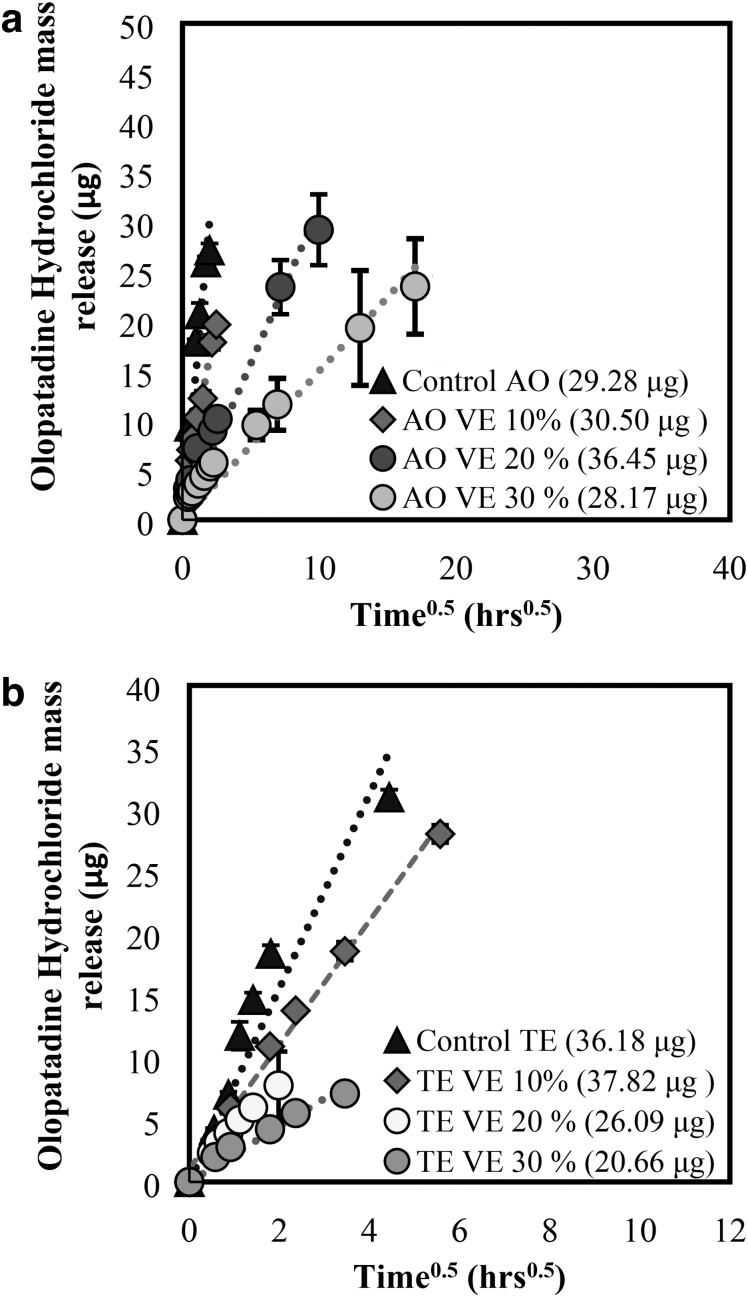

FIG. 2.

Dynamics of olopatadine transport during the release phase in commercial and modified ACUVUE OASYS (a, b) and ACUVUE TruEye (a, c) lenses. Data are presented as mean ± SD with n = 3. SD, standard deviation.

In vitro studies—dynamics of olopatadine transport from VE-loaded SCLs

The dynamics of olopatadine release from VE-loaded commercial ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses are presented in Fig. 2. Figure 2 indicates that ACUVUE OASYS lenses modified with a 10% VE loading/g dry gel shows a 17–20-fold increase in olopatadine release duration with a 6.5% increase in the cumulative mass delivered in comparison to the control lenses.

To explore the existence of olopatadine-VE interaction further, drug transport from the lens with different VE loadings were studied. The extent of sustained olopatadine release duration with an increase in VE loading/g of the hydrogel lens was also recorded. With the increase in VE loadings to 20% and 30%, a 150-fold and 375-fold increase in olopatadine release durations are observed, showing promise of a month-long therapy. In vitro data also indicate that a 20% VE-loaded ACUVUE OASYS lens delivers 36 μg in 17 days, while the modified lens with a 30% release a cumulative mass of 28 μg during a 40-day release duration.

The release duration is considerably longer than what was achieved via molecular imprinting of olopatadine in contact lenses.68 In vitro release shows that incorporation of VE in ACUVUE TruEye lenses results in a 43% decrease in olopatadine partitioned in the matrix. The barrier effect is not substantial and is a case of ACUVUE TruEye lenses with a 2.6-fold and 7.2-fold increase in release durations observed for 20% and 30% VE modified lenses, respectively. Table 2 summarizes the calculated parameters including olopatadine diffusivity in the gel matrix and its distribution coefficient in both control and VE modified lenses for both lens compositions. These results are consistent with prior studies demonstrating effectiveness of VE barriers at prolonging release duration of many drugs.51,53,61,65–68 Prior studies have also shown presence of VE aggregates in the Scanning Electron Microscope images67,68 and measured impact of VE incorporation on transparency, ion, and oxygen permeability,61 and modulus.69 The VE loading led to reduction in oxygen diffusion by about 15% for 20% VE loading and by about 40% for 75% loading.61 VE incorporation had a more significant reduction in the ion permeability (50% reduction for 10% loading), but the reduced ion permeability is still above the critical requirement.61 Additionally, VE loading has a beneficial effect of blocking UV radiation which will reduce the corneal damage due to UV light.61 The tensile strength and elongation at break of silicone hydrogel contact lenses were 0.19 MPa and 32%, respectively. These changed to 0.170 MPa and 56%, respectively, due to incorporation of VE.69

Table 2.

Summary of Olopatadine Partition Coefficients and Effective Diffusivities in Both Control and Vitamin-E Modified ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye Lenses

| Contact lens | Total drug into/from the lens matrix (μg) |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake | Release | Water content (%) | Partition coefficient | Effective diffusivity ( × 10−5 mm2/h) | |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE TruEye® | — | 36.25 ± 2.2 | 46.1 ± 0.2 | 0.78 ± 0.1 | 8.44 |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE TruEye (with 10% VE) | — | 37.86 ± 1.7 | 45.5 ± 0.9 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 2.53 |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE TruEye (with 20% VE) | — | 26.09 ± 0.8 | 42.8 ± 0.4 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 2.31 |

| 1-DAY ACUVUE TruEye (with 30% VE) | — | 20.66 ± 3.1 | 40.1 ± 0.2 | 0.50 ± 0.1 | 0.65 |

| ACUVUE OASYS | — | 29.28 ± 0.9 | 37.9 ± 0.2 | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 48.7 |

| ACUVUE OASYS (with 10% VE) | — | 30.50 ± 1.6 | 34.2 ± 0.1 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 9.65 |

| ACUVUE OASYS (with 20% VE) | — | 36.45 ± 4.3 | 31.8 ± 1.1 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 1.12 |

| ACUVUE OASYS (with 30% VE) | — | 28.17 ± 0.7 | 30.9 ± 0.6 | 0.63 ± 0.1 | 0.37 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD with “N = 3”.

SD, standard deviation.

Release mechanism and solute transport properties

The average thickness of both commercial ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye contact lenses is about 80–100 μm, which is significantly smaller in comparison to the diameter of these lenses (14 mm). Due to the large aspect ratio, olopatadine transport into the hydrogel matrix is assumed to be a 1D diffusion along the transverse direction. To substantiate the assumption of 1D plane diffusion, release profiles are plotted as a function of the square root of time. For a diffusion-controlled transport, the release at short timers is described by the Higuchi model. The mass of olopatadine delivered at short time regime is given by

| (10) |

where Mt is mass of olopatadine accumulated in the aqueous reservoir from the thin hydrogel at a characteristic time t, is mass of olopatadine accumulated in the aqueous reservoir at long time intervals when the flux of drug entering the aqueous reservoir is negligible. Figure 3 shows representative plots indicating mass of olopatadine released as a function of the square root of time with corresponding R2 values of 0.91 in agreement with the suggested transport mechanism. All R2 values of >0.90 for VE-modified lenses indicate that integration of nanobarriers within the lens matrix does not affect the mechanism of drug transport.

FIG. 3.

Dynamics of olopatadine transport during the release phase in commercial and modified ACUVUE OASYS (a) and ACUVUE TruEye (b) lenses plotted as a function of to demonstrate diffusion control mechanism. Data are presented as mean ± SD with n = 3.

In vitro model for olopatadine release—Diffusivity estimates

The in vitro experimental data were fit to the analytical solution (equation 9) using fminsearch module to obtain transport diffusivities of olopatadine in control and VE modified lens matrices, which are listed in Table 2. Reasonable fits between the release data and the model indicate the validity of the proposed model. It is observed that incorporation of VE nanobarriers lowers the effective diffusivity of olopatadine in the gel matrix, which translates to an increase in drug diffusion time scales, thus leading to extended release. The statistical estimate R2 is estimated to be >0.95 irrespective of the mass of VE loaded in the modified lenses suggesting no deviation in the governing transport mechanism.

Effect of VE integration on sustained olopatadine release

The extent of sustained olopatadine payload release can be correlated with different fractions of VE loadings in commercial hydrogels by a scaling model proposed by Peng et al.61 For small hydrophilic antihistamines like olopatadine, the drug–VE barrier interaction is negligible with surface diffusion along polymer chains offering additional resistance to solute transport through the matrix. Since olopatadine transports from a control gel matrix is diffusion-controlled, the release duration scales as  As described in our prior work,61 assuming isotropic expansion of the gel volume upon modification yields an expression for the modified gel thickness as a function of VE volume fraction. The fractional increase in solute transport duration from a VE-modified lens matrix is related to VE loading and the drug diffusivity as

As described in our prior work,61 assuming isotropic expansion of the gel volume upon modification yields an expression for the modified gel thickness as a function of VE volume fraction. The fractional increase in solute transport duration from a VE-modified lens matrix is related to VE loading and the drug diffusivity as

| (11) |

where  represents the extent of increase in olopatadine release durations, is the volume fraction of VE partitioned as nanobarrier depots, is the volume fraction of VE solubilized in the polymer phase, and represents a parameter specific to the lens type and aspect ratio of the partitioned barriers.

represents the extent of increase in olopatadine release durations, is the volume fraction of VE partitioned as nanobarrier depots, is the volume fraction of VE solubilized in the polymer phase, and represents a parameter specific to the lens type and aspect ratio of the partitioned barriers.

It is interesting to observe a stark difference in the parameter between ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses. A 14-fold difference in between the 2 lenses suggests that microstructure of the lenses and interfacial area offered by co-continuous domains in the gel is of paramount importance. This is reflected in significant differences in release durations of olopatadine from a 30% VE lenses of both types with substantial barrier effect observed in the case of ACUVUE OASYS. The effect of olopatadine release extension is not strongly influenced by barrier formation in ACUVUE TruEye lenses suggesting a low density of barriers formed in the matrix as opposed to ACUVUE OASYS. Fits to experimental data of time ratios for different VE loadings (Fig. 4) through error minimization reveal to be 0.04 and 0.016 for ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye, respectively, suggesting that >98% of the partitioned VE phase separate into ellipsoids of high aspect ratio. Parametric estimation also reveals α, the lens parameter to be 56.11 and 4.6 for ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye, respectively, attributing a substantial reduction in release durations to enhance length scales or tortuosity effects imposed by VE nanobarriers. This theoretical scaling model also serves as a tool for predicting the time scale for olopatadine delivery through VE modified lens with specific VE volume fraction and lens thickness, respectively.

FIG. 4.

A scaling model proposed by Chauhan et al. used to predict the ratio of olopatadine release duration increase with respect to volume fraction of VE phase separated into the lens matrix. The solid lines are the best-fit results based on the scaling model presented for both commercial ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses. Data are presented as mean ± SD with “n = 3.” The magnitude of error bars is small in comparison to the marker size.

Conclusions

In this in vitro study, the feasibility of sustained antihistamine delivery, namely olopatadine hydrochloride (H1 antagonist) by VE modified commercial silicone hydrogels was investigated. A commercially viable 1-step procedure is devised for entrapment of ethanol solubilized VE and creation of in situ nanobarrier depots. The modification addresses the drawbacks of time-intensive lens fabrication through molecular imprinting, spin-coating, and drug-rich ring implant placements on lens substrates.

In vitro studies indicate that ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses loaded with ∼0.3 g of VE/g of hydrogel effectively prolong olopatadine dynamics by 7-fold and 375-fold, respectively, delivering therapeutic dosages for 2 weeks. The results agree with the hypothesis that VE nanobarriers with high aspect ratio serve as diffusion attenuators by inducing tortuosity effects to influence olopatadine transport. The issue of burst release from the lens surface is resolved by the inclusion of tortuous solute diffusion pathways in the lens matrix, resulting in a 131-fold and 13-fold decrease in olopatadine diffusivities in ACUVUE OASYS and ACUVUE TruEye lenses respectively. Optical properties are retained after VE aggregate integration in these lenses. The absence of enhanced olopatadine partitioning in ACUVUE TruEye lenses, as opposed to the OASYS, suggests that hydrogel composition and surface area of co-continuous phases in the lens matrix play a critical role. While olopatadine-VE barrier interaction is thought to contribute to enhanced partitioning in 20% VE-modified ACUVUE OASYS lenses, no significant effect is seen with higher loadings. The VE modification of commercial lenses has multipronged benefits including drug delivery at therapeutic dosages and enhanced patient compliance. As drug-eluting ocular devices providing improved conjunctival bioavailability, they could impact millions suffering from conjunctivitis.

Disclaimer

The authors alone are responsible for the content presented in the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

Declaration of Interest A.C. is a coinventor on U.S. 8.404.265 B2 patent titled, “Contact lenses for extended release of bioactive agents containing diffusion attenuators.”

Funding Information

The work was partially supported by the NIH award R01EY034477.

References

- 1. Abelson MB, Chambers WA, Smith LM. Conjunctival allergen challenge: A clinical approach to studying allergic conjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108(1):84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abelson MB, Schaefer K.. Conjunctivitis of allergic origin: Immunologic mechanisms and current approaches to therapy. Surv Ophthalmol 1993;38 Suppl:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allansmith MR, Ross RN. Ocular allergy and mast cell stabilizers. Surv Ophthalmol 1986;30(4):229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: A systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 2013;310(16):1721–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bielory L. Allergic conjunctivitis and the impact of allergic rhinitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2010;10(2):122–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang TW, Shiung YY. Anti-IgE as a mast cell–stabilizing therapeutic agent. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117(6):1203–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friedlaender MH. Conjunctivitis of allergic origin: Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis. Surv Ophthalmol 1993;38:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedlaender MH. A review of the causes and treatment of bacterial and allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Ther 1995;17(5):800–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Friedlaender MH, Okumoto M, Kelley J. Diagnosis of allergic conjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102(8):1198–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. La Rosa M, Lionetti E, Reibaldi M, et al. Allergic conjunctivitis: A comprehensive review of the literature. Ital J Pediatr 2013;39:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buckley R. Allergic eye disease—A clinical challenge. Clin Exp Allergy 1998;28:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ciprandi G, Buscaglia S, Cerqueti PM, et al. Drug treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. A review of the evidence. Drugs 1992;43(2):154–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosario N, Bielory L. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;11(5):471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belfort R, Marbeck P, Hsu CC, et al. Epidemiological study of 134 subjects with allergic conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000;78:38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greiner AN, Hellings PW, Rotiroti G, et al. Allergic rhinitis. Lancet 2011;378(9809):2112–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scoper SV, Berdy GJ, Lichtenstein SJ, et al. Perception and quality of life associated with the use of olopatadine 0.2% (Pataday™) in patients with active allergic conjunctivitis. Adv Ther 2007;24(6):1221–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bielory L, Lien KW, Bigelsen S. Efficacy and tolerability of newer antihistamines in the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. Drugs 2005;65(2):215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ousler III GW, Workman DA, Torkildsen GL. An open-label, investigator-masked, crossover study of the ocular drying effects of two antihistamines, topical epinastine and systemic loratadine, in adult volunteers with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Ther 2007;29(4):611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pipkorn U, Bende M, Hedner J, et al. A double-blind evaluation of topical levocabastine, a new specific H1 antagonist in patients with allergic conjunctivitis. Allergy 1985;40(7):491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simons FER, Simons KJ. Histamine and H1-antihistamines: Celebrating a century of progress. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128(6):1139–1150. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dockhorn RJ, Duckett TG. Comparison of Naphcon-A and its components (naphazoline and pheniramine) in a provocative model of allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Eye Res 1994;13(5):319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greiner JV, Udell IJ. A comparison of the clinical efficacy of pheniramine maleate/naphazoline hydrochloride ophthalmic solution and olopatadine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution in the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Clin Ther 2005;27(5):568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahluwalia P, Anderson DF, Wilson SJ, et al. Nedocromil sodium and levocabastine reduce the symptoms of conjunctival allergen challenge by different mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108(3):449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leon J, Charap A, Duzman E, et al. Efficacy of cimetidine/pyrilamine eyedrops: A dose response study with histamine challenge. Ophthalmology 1986;93(1):120–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blumenthal M, Casale T, Dockhorn R, et al. Efficacy and safety of nedocromil sodium ophthalmic solution in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;113(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bonini S, Schiavone M, Bonini S, et al. Efficacy of lodoxamide eye drops on mast cells and eosinophils after allergen challenge in allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 1997;104(5):849–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eady R. The pharmacology of nedocromil sodium. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl 1986;147:112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fahy G, Easty DL, Collum LM, et al. Randomised double-masked trial of lodoxamide and sodium cromoglycate in allergic eye disease: A multicentre study. Eur J Ophthalmol 1992;2(3):144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gonzalez JP, Brogden RN. Nedocromil sodium. Drugs 1987;34(5):560–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kray KT, Squire Jr EN, Tipton WR, et al. Cromolyn sodium in seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1985;76(4):623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leonardi A, Borghesan F, Avarello A, et al. Effect of lodoxamide and disodium cromoglycate on tear eosinophil cationic protein in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81(1):23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miyake-Kashima M, Takano Y, Tanaka M, et al. Comparison of 0.1% bromfenac sodium and 0.1% pemirolast potassium for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2004;48(6):587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Odelram H, Björkstén B, af Klercker T, et al. Topical levocabastine versus sodium cromoglycate in allergic conjunctivitis. Allergy 1989;44(6):432–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ballas Z, Blumenthal M, Tinkelman DG, et al. Clinical evaluation of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution for the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1993;38:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tinkelman DG, Rupp G, Kaufman H, et al. Double-masked, paired-comparison clinical study of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution compared with placebo eyedrops in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1993;38:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ebihara N, Ohashi Y, Uchio E, et al. A large prospective observational study of novel cyclosporine 0.1% aqueous ophthalmic solution in the treatment of severe allergic conjunctivitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2009;25(4):365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ozcan AA, Ersoz TR, Dulger E. Management of severe allergic conjunctivitis with topical cyclosporin A 0.05% eyedrops. Cornea 2007;26(9):1035–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu H, Chauhan A. A mathematical model for tear drainage through the canaliculi. Curr Eye Res 2005;30(8):621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lux A, Maier S, Dinslage S, et al. A comparative bioavailability study of three conventional eye drops versus a single lyophilisate. Br J Ophthalmol 2003;87(4):436–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ahmed S, Amin MM, Sayed S. Ocular drug delivery: A comprehensive review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023;24(2):66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gause S, Hsu K-H, Shafor C, et al. Mechanistic modeling of ophthalmic drug delivery to the anterior chamber by eye drops and contact lenses. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2016;233:139–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baudouin C, de Lunardo C. Short term comparative study of topical 2% carteolol with and without benzalkonium chloride in healthy volunteers. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82(1):39–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hsu KH, Gupta K, Nayaka H, et al. Multidose preservative free eyedrops by selective removal of benzalkonium chloride from ocular formulations. Pharm Res 2017;34(12):2862–2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ishibashi T, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S. Comparison of the short-term effects on the human corneal surface of topical timolol maleate with and without benzalkonium chloride. J Glaucoma 2003;12(6):486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gupta C, Chauhan A. Drug transport in HEMA conjunctival inserts containing precipitated drug particles. J Colloid Interface Sci 2010;347(1):31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tai MC, Cosar CB, Cohen EJ, et al. The clinical efficacy of silicone punctal plug therapy. Cornea 2002;21(2):135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alvarez-Lorenzo C, Yañez F, Barreiro-Iglesias R, et al. Imprinted soft contact lenses as norfloxacin delivery systems. J Control Release 2006;113(3):236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ciolino JB, Ross AE, Tulsan R, et al. Latanoprost-eluting contact lenses in glaucomatous monkeys. Ophthalmology 2016;123(10):2085–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ciolino JB, Stefanescu CF, Ross AE, et al. In vivo performance of a drug-eluting contact lens to treat glaucoma for a month. Biomaterials 2014;35(1):432–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gulsen D, Chauhan A. Ophthalmic drug delivery through contact lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45(7):2342–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hsu KH, Carbia BE, Plummer C, et al. Dual drug delivery from vitamin E loaded contact lenses for glaucoma therapy. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2015;94:312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim J, Conway A, Chauhan A. Extended delivery of ophthalmic drugs by silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Biomaterials 2008;29(14):2259–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim J, Peng CC, Chauhan A. Extended release of dexamethasone from silicone-hydrogel contact lenses containing vitamin E. J Control Release 2010;148(1):110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li C, Chauhan A. Ocular transport model for ophthalmic delivery of timolol through p-HEMA contact lenses. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2007;17(1):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li CC, Chauhan A. Modeling ophthalmic drug delivery by soaked contact lenses. Ind Eng Chem Res 2006;45(10):3718–3734. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hillman J, Marsters J, Broad A. Pilocarpine delivery by hydrophilic lens in the management of acute glaucoma. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 1975;95(1):79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hillman JS. Management of acute glaucoma with pilocarpine-soaked hydrophilic lens. Br J Ophthalmol 1974;58(7):674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gulsen D, Li C-C, Chauhan A. Dispersion of DMPC liposomes in contact lenses for ophthalmic drug delivery. Curr Eye Res 2005;30(12):1071–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hiratani H, Fujiwara A, Tamiya Y, et al. Ocular release of timolol from molecularly imprinted soft contact lenses. Biomaterials 2005;26(11):1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jung HJ, Abou-Jaoude M, Carbia BE, et al. Glaucoma therapy by extended release of timolol from nanoparticle loaded silicone-hydrogel contact lenses. J Control Release 2013;165(1):82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Peng C-C, Kim J, Chauhan A. Extended delivery of hydrophilic drugs from silicone-hydrogel contact lenses containing vitamin E diffusion barriers. Biomaterials 2010;31(14):4032–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kapoor Y, Dixon P, Sekar P, et al. Incorporation of drug particles for extended release of cyclosporine a from poly-hydroxyethyl methacrylate hydrogels. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2017;120:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peng C-C, Ben-Shlomo A, Mackay EO, et al. Drug delivery by contact lens in spontaneously glaucomatous dogs. Curr Eye Res 2012;37(3):204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Peng C-C, Burke MT, Chauhan A. Transport of topical anesthetics in vitamin E loaded silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Langmuir 2011;28(2):1478–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sekar P, Chauhan A.. Effect of vitamin-E integration on delivery of prostaglandin analogs from therapeutic lenses. J Colloid Interface Sci 2019;539:457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hsu KH, de la Jara PL, Ariyavidana A, et al. Release of betaine and dexpanthenol from vitamin E modified silicone-hydrogel contact lenses. Curr Eye Res 2015;40(3):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liu Z, Overton M, Chauhan A. Transport of vitamin E from ethanol/water solution into contact lenses and impact on drug transport. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2022;38(6):396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dixon P, Ghosh T, Mondal K, Konar, et al. Controlled delivery of pirfenidone through vitamin E-loaded contact lens ameliorates corneal inflammation. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2018;8(5):1114–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang X, Zhao Y, Jing Y, et al. Modification of silicone hydrogel contact lenses with vitamin E for the delivery of ofloxacin. J Nanomater 2023:1500048. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Maulvi FA, Singhania SS, Desai AR, et al. Contact lenses with dual drug delivery for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Int J Pharm 2018;548(1):139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peng C-C, Chauhan A.. Ion transport in silicone hydrogel contact lenses. J Membrane Sci 2012;399:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 72. González-Chomón C, Silva M, Concheiro A, Alvarez-Lorenzo C.. Biomimetic contact lenses eluting olopatadine for allergic conjunctivitis. Acta Biomater 2016;41:302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sharif NA, Xu SX, Yanni JM. Olopatadine (AL-4943A): Ligand binding and functional studies on a novel, long-acting H1-selective histamine antagonist and anti-allergic agent for use in allergic conjunctivitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 1996;12(4):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]