Summary

Following tissue damage, epithelial stem cells (SCs) are mobilized to enter the wound, where they confront harsh inflammatory environments that can impede their ability to repair the injury. Here, we investigated the mechanisms that protect skin SCs within this inflammatory environment. Characterization of gene expression profiles of skin SCs that migrated into the wound site revealed activation of an immune-modulatory program, including expression of CD80, MHCII and CXCL5. Deletion of CD80 in HFSCs impaired re-epithelialization, reduced accumulation of peripherally generated Treg (pTreg) cells, and increased infiltration of neutrophils in wounded skin. Importantly, similar wound healing defects were also observed in mice lacking pTreg cells, and the re-epithelization deficiency can be ameliorated by CXCL5 neutralization. Our findings suggest that upon skin injury, HFSCs establish a temporary protective network by promoting local expansion of Treg cells, thereby enabling re-epithelialization while still kindling inflammation outside this niche until the barrier is restored.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

In skin injury, the inflammatory environment can impact repair mediated by skin stem cells. Luan, Truong, Vuchkovska et al. show that hair follicle stem cells migrate into the wound, activate immune modulatory molecules, and expand extrathymic regulatory T cells to facilitate the resolution of neutrophil responses and initiation of wound repair.

Introduction

Adult stem cells (SCs) are responsible for maintaining and regenerating body tissues.1 Indispensable and long-lived, tissue stem cells are challenged by frequent exposure to inflammation caused by a myriad of infections and injuries over a plant or animal’s lifetime.2–4 Facing such challenges, stem cells must be protected from repeated bouts of inflammation to ensure rapid tissue regeneration while also maintaining the stem cell pool for tissue homeostasis and for confronting future injuries. Despite this vital necessity, it is unclear how adult stem cells survive and drive tissue regeneration within the inflammatory environment that ensues following injury.

Mammalian skin offers an excellent system to tackle this question. During homeostasis, epithelial stem cells of the skin reside within specialized niches that receive inputs from their local microenvironments to instruct them what to do and when.5 Epidermal stem cells (EpdSCs) reside within the innermost (basal) layer of the skin epithelium, where they are responsible for making and replenishing the surface barrier that retains body fluids and excludes harmful microbes. Additional skin epithelial stem cells reside within local niches of epidermal appendages, including sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and hair follicles (HFs). These epithelial stem cells share a common embryonic precursor. In the adult, they are typified by keratins 5 (K5) and 14 (K14) and reside along a contiguous basement membrane, which demarcates the epithelium from the dermis and is rich in extracellular matrix and growth factors. Along the basement membrane are distinct niches that are uniquely tailored to suit the specialized tasks of each stem cell population, enabling them to regenerate and rejuvenate the epithelium within their particular domain.6

Upon injury, skin epithelial stem cells become mobilized to leave the confines of their native niches. Whether it is the stem cells of the epidermis or an epidermal appendage, once they are called into action and exit the confines of their native niches, they are unleashed to perform a new task, namely re-epithelialization of damaged tissue.7–12 An excellent example of this phenomenon takes place in frequently occurring shallow skin wounds, where the skin has been denuded of the epidermis and the upper non-cycling portion of the HF. This forces the underlying HF stem cells (HFSCs) residing in an anatomical structure called the bulge to be repurposed from their normal hair regeneration role to instead migrate upward and repair the damaged epithelial tissue.13 The newly repaired epidermis is thus composed of former HFSCs that now act as epidermal stem cells, maintaining the skin barrier and guarding against infections.6

Under homeostasis, stem cells are often thought to reside within an immune-privileged environment.14,15 Although the field is still evolving, it has been postulated that the stem cell niche of the HF bulge maintains immune privilege by producing immunosuppressive molecules such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) or transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) to dampen inflammation around the stem cells if homeostasis is perturbed.16,17 It has been further suggested that suppressive immune cells such as tissue-resident regulatory T cells (Tregs) may even play an active role during normal skin homeostasis, where they have been implicated in stimulating self-renewal and promoting hair regeneration in the normal hair cycle.18,19

A major unaddressed question is how stem cells are protected following injury when they leave their niche and migrate into the wound bed to restore the barrier.6 After wounding, damaged tissue is exposed to pathogens and dead cells, triggering a cascade of responses that includes the recruitment of inflammatory immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, which secrete not only anti-microbial molecules but also pro-inflammatory cytokines. These factors are critical for fending off pathogens and clearing dead cells, but if left unchecked, can cause immense stress for the stem cells. Caught in the crosshairs of such robust inflammation outside of their immune-privileged niche, adult stem cells must be poised to evade collateral damage from infiltrating inflammatory immune cells so they can successfully re-epithelialize the wound.

Here, we explored this possibility and interrogated the behavior of skin stem cells in a mouse model of partial-thickness skin wounding in which injury-activated HFSCs migrated out of their bulge niche and entered the highly inflammatory wound bed to regenerate the damaged epidermis and upper HF.

Results

Hair follicle stem cells activate immune-modulatory programs during wound repair.

Partial-thickness wounding mechanically removes the superficial epidermis and upper HF, leaving intact the dermal components, including the epithelial stem cell niche of the HF (Figure 1A).2,13 To broadly examine how skin epithelium reacts to wound-induced inflammation, we began by using Krt14CreER; Rosa26-LSL-tdTomato mice to trace the progeny of basal keratinocytes in the mouse skin, which contain both interfollicular EpdSCs and HFSCs. Following tamoxifen administration to activate tdTomato expression, we administered a shallow wound with a calibrated Dremel tool at day 0, then waited 3 days until the migrating HFSCs had entered the wound bed (Figure 1A). We then prepared single-cell suspensions of the skins and used fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate tdTomato+ epithelial cells. After excluding immune cells (CD45+), endothelial cells (CD31+), fibroblasts/adipocytes (CD140a+), and melanocytes (CD117+), we further screened for integrin α5, a marker of wound-activated, migrating epithelial cells (Figure S1A).2

Figure 1: Skin epithelium activates an immune-modulatory program during wound healing.

A) Schematic showing the lineage tracing of basal skin epithelium, followed by partial thickness wounding.

B) Gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes in basal skin keratinocytes from wounded skin (day3 wound) compared to cells from unwounded skin.

C) Heat map and representative genes that are differentially expressed in basal skin keratinocytes from wounded skin (day3 wound) compared to cells from unwounded skin.

D) UMAP plots showing expression of various markers, including Cd80 and MHCII genes, activated in the basal epithelial skin cells during wound repair.

E) Flow cytometry plots and MFI quantification of CD80 and MHCII on various cell populations in unwounded (UD) or wounded (WD) skin. Each symbol represents an independent animal. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. Unpaired t test, * p<0.05; ** p<0.01. See also Figure S1.

F) ImageStream analysis to visualize co-expression of CD80 and MHCII in the Tomato+ basal epithelial stem cells that have acquired Integrin α5+ and migrated into the wounded skin (day3 wound).

When we subjected the pool of FACS-isolated integrin α5+tdTomato+ epithelial cells to RNA sequencing, we observed good concordance between replicates (Figure S1B). As reflected in the gene ontology (GO) analysis, transcripts encoding keratinization and differentiation characteristics were among the most downregulated, while upregulated transcripts encoded putative extracellular matrix and migration-associated proteins as well as secreted cytokines (Figure 1B).

Of particular interest were transcripts involved in antigen presentation and immune co-stimulation (e.g. Cd74, H2-Aa, H2-Ab1, and Cd80), which were induced in the injury-activated epithelial stem cells that had migrated into the wound bed (Figure 1C). Although MHCII molecules and CD80 are classical features of dendritic cells and macrophages, MHCII has recently been found on the surface of neural progenitors, intestinal epithelial stem cells, ductal cells and some tumor cells, while CD80, a member of the B7 family molecules, has been reported in the tumor-initiating stem cells of various epithelial cancers.20–25 In immune cells, these proteins are known to modulate immune responses by activating T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and providing co-stimulatory signals to T lymphocytes. This leads to the tantalizing hypothesis that tissue stem cells that move into the wound bed have the capacity to modulate T cells.

Probing deeper into this possibility, we analyzed the single-cell transcriptome of cells isolated from full-thickness skin wounds, and confirmed the immune modulatory feature of our CD45negK14+ epithelial cells.26 We showed that the transcripts for Cd80 and MHCII components were exclusive to a subset of skin keratinocytes that emerged after wounding and exhibited classical features of having undergone a partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition and activated migration (Itga5, Vim, and Snail), accompanied by dampened epithelial features (Krt14, Krt5, and Cdh1) (Figure 1D; Figure S1C). Even within this migratory epithelial population, the transcriptional activation status of Cd80 was heterogeneous, with only a small subset (less than 10%) of total Krt14+Itga5+ cells expressing appreciable levels of the mRNA encoding this immune-modulatory factor.

Based upon these observations, we compared the gene signatures of Cd80+Itga5+ and Cd80negItga5+ epithelial cells and found that compared to the Cd80neg cells, the Cd80+ migratory epithelial cells expressed a higher level of additional immune-modulatory factors or cytokines, such as CD74, H2-Aa, Il1b, Ccl3 (Figure S1D). As these features are typically ones of immune cells, rather than epithelial cells, we further confirmed these findings at the protein level by performing flow cytometry analysis on migratory epithelial skin stem cells isolated on day3 post-wounding from Krt14CreER; Rosa26-LSL-tdTomato mice, which had been activated for lineage-tracing during the telogen-phase of the hair cycle (see Figure 1A). These data showed that individual migratory epithelial skin stem cells in the wound bed which were marked by K14 (Krt14CreER-induced tdTomato) and α5 integrin concomitantly displayed surface CD80 and MHCII (Figure 1E). Their selective coactivation in wound-induced skin stem cells was further exemplified by image stream analyses of individual stem cells (Figure 1F). Notably, these markers were not detected in unwounded epithelial skin stem cells, nor were they found in other non-immune cell populations within the wounded skin (Figure 1E).

Previous lineage tracing experiments have demonstrated that, when the epidermis and upper HF segments are removed in a partial-thickness wound, the underlying bulge HFSCs are the major stem cell population that migrate out of their niches and into the wound bed to repair the missing epithelial tissue.2,13 These HFSCs are the critical basal epithelial cells that undergo a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and acquire the migratory integrin α5 to initiate re-epithelization. By using Sox9CreER; Rosa26-LSL-tdTomato mice to specifically lineage trace HFSCs and not EpdSCs, we confirmed their contribution and kinetics in repairing the partial thickness wound [Figure 2A; see also2].

Figure 2: CD80 is activated in a subset of HFSCs that enter the wound bed during wound repair.

A) IF images of sagittal sections of partial thickness wounds showing the healing dynamics of Sox9+ HFSCs that were lineage-traced in Sox9-CreER; Rosa26-tdTomato mice. Scale bars: 100 μm

B) IF images of sagittal sections of unwounded or wounded (day 3) skin showing that Tomato+ HFSC cells that acquire a5 are also positive for CD80. Scale bars: 100 μm

C) Flow cytometry analysis and MFI quantification of CD80 and MHCII on on various cell populations in unwounded (UD) or wounded (WD) skin. Each symbol represents an independent animal. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. Unpaired t test, ** p<0.01.

D) ImageStream analysis to visualize CD80 and MHCII on migratory Tomato+α5+ HFSCs from wounded skin (day3 wound) on Sox9CreER traced mice.

E) ATAC-sequencing peaks showing the accessibility status of the Cd80 and MHCII (H2-Aa and H2-Ab1) genomic loci within the chromatin of FACS-purified, Sox9CreER-lineage traced HFSCs from unwounded or wounded skin (day3 wound).

Importantly, when lineage tracing of the Sox9+ HF cells was activated prior to wounding and then analyzed on day3 post-wounding, it was clear that the migrating α5+tdTomato+ epithelial stem cells in the wound bed were positive for CD80 (Figure 2B). Again, flow cytometry and image stream analyses of wound-induced epithelial stem cells confirmed that like the Krt14CreER lineage traced cells, Sox9CreER traced cells co-expressed markers of migrating HF-derived, and epithelial stem cells and immunomodulatory cells were negative for the pan-immune cell marker CD45 (Figures 2C and 2D).

Using Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with Sequencing (ATAC-seq), we analyzed the chromatin accessibility of HFSCs isolated from unwounded and wounded skin on day3 post-wounding. Our data confirmed that the promoter region of both Cd80 and MHCII genes in HFSCs, while present in an open chromatin state in normal skin homeostasis, gained prominent new open chromatin peaks upon wounding (Figure 2E). These data further bolstered the activation of immune modulatory genes in wound-induced migratory HFSCs.

CD80 expressed by wound-activated skin stem cells is essential to repair cutaneous wounds

To test the functional significance of the immune-modulatory program for skin epithelial stem cells during wound repair, we took advantage of our finding that the migrating HFSCs are the major non-hematopoietic cells expressing CD80 in wounded skin (Figure 2C). We therefore reconstituted lethally irradiated Cd80 null mice with wild-type bone marrow and generated bone marrow chimeras (Cd80−/− mice with WT bone marrow). In these mice, CD80 was expressed in the bone marrow-derived immune cells but remained ablated in non-hematopoietic cells, notably HFSCs. To account for possible effects arising from the manipulations, WT control mice were also irradiated and reconstituted with the same WT bone marrow (WT mice with WT bone marrow).

One day post-wounding, the skins of both cohorts displayed the eschar (scab) but remained denuded of its underlying epidermis. By day3 post-wounding, the re-epithelization process had been initiated in both WT and Cd80 null mice harboring WT bone marrows (Figure 3A). By day5 post-wounding, the wounds in the control group (WT mice with WT BM) were completely re-epithelialized with new hyperproliferative and differentiating K14+ epithelial cells covering the wound bed. In striking contrast, the Cd80 null mice reconstituted with a WT hematopoietic system displayed only discrete portions of re-epithelialization, with large areas consisting of only granulated tissue (see quantifications in Figure 3A). Additionally, and again in contrast to the control mice, Cd80 null mice with WT bone marrow exhibited signs of a markedly delayed epidermal differentiation program with fewer newly generated K10+ barrier epidermal cells at day 5 of the repair process (Figure 3A).

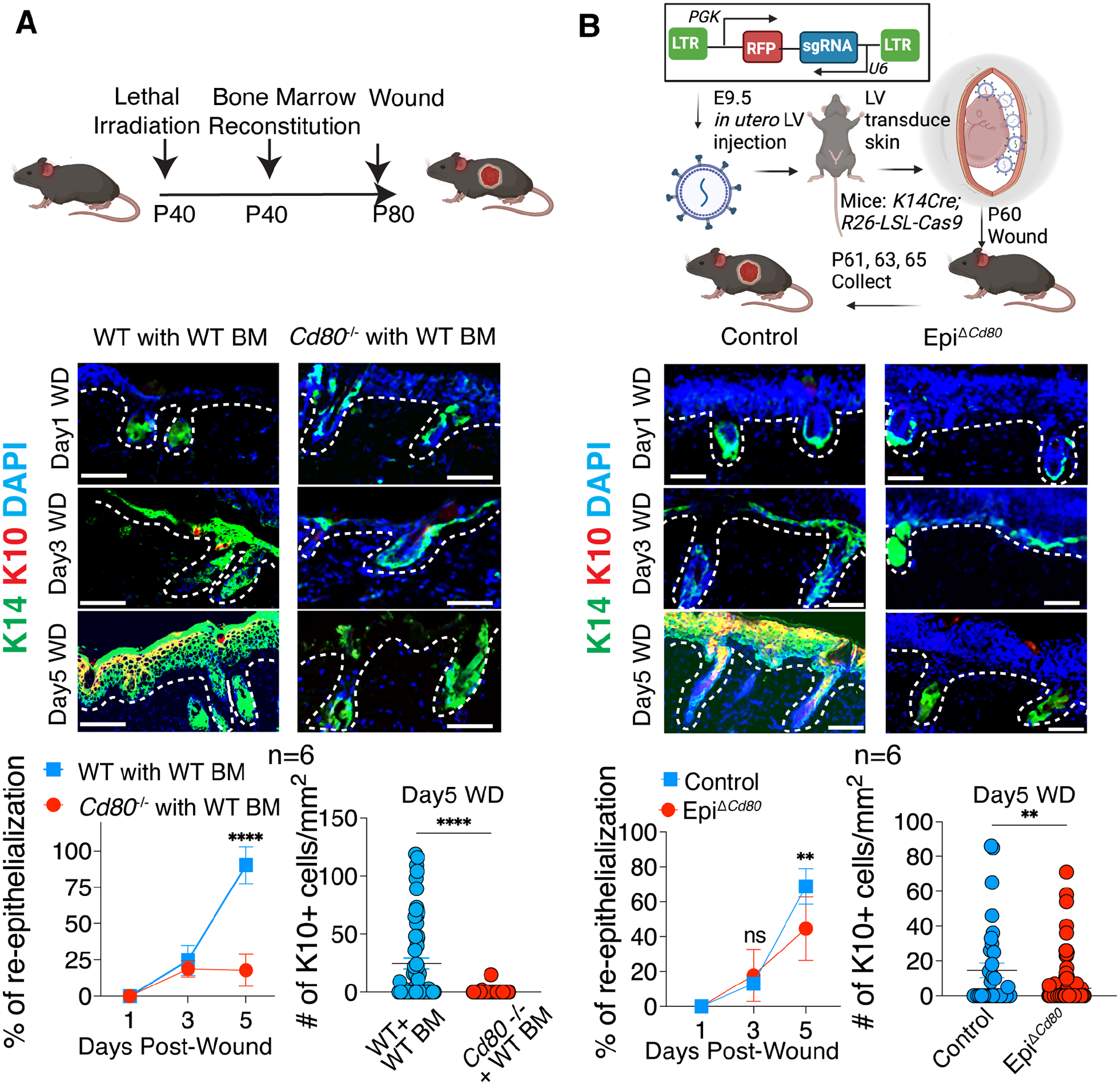

Figure 3: Specific ablation of CD80 in HFSCs results in wound healing delays.

A) Schematic is of wounding in irradiated Cd80−/− or WT control mice and reconstituted with WT bone marrow (BM). Shown below are IF images and quantifications of the percentage of wound re-epithelialization (K14+) and the number of differentiated suprabasal cells (K10+) in the skins at times indicated after partial thickness wounding.

B) Schematic is of lentivirus injected into the amniotic sac of E9.5 embryos of Krt14-Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice to specifically transduce surface epithelial skin progenitors, here with Cd80-targeting sgRNAs (EpiΔCd80) or use Cre negative mice as controls. Shown below are IF images and quantifications of the percentage of wound re-epithelialization (K14+) and the number of differentiated suprabasal cells (K10+) in the skins at times indicated after partial thickness wounding.

Each symbol represents a technical replicate. Results pooled from two independent experiments are shown (n=3 animals for each time point in each experiment). Unpaired t test, ** p<0.01; **** p<0.0001. Scale bars: 100 μm. See also Figure S2.

To further interrogate the functional relevance to wound repair of CD80’s expression by skin stem cells and rule out possible contributions to the phenotype by resident Cd80 null immune cells or other stromal populations remaining in the tissue after irradiation, we sought to design models to explicitly silence CD80 in the skin epithelium of otherwise WT mice. For this purpose, we employed a powerful ultrasound-guided in utero delivery strategy to achieve skin epithelium-specific CRISPR gene editing. In this approach, lentiviral (LV) particles are injected into the amniotic fluid of embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) living mouse embryos to stably and selectively transduce the single-layered surface progenitors that later develop into the skin epithelium.27 Using this method, we delivered a LV containing a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting Cd80 in utero into Krt14Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mouse embryos to generate skin epithelial-specific Cd80 knockout mice (EpiΔCd80) (Figure 3B). As K14Cre is activated by ~E14.5 and specific to the basal skin progenitors where the nascent HFSCs reside at this time, this ensured that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing and silencing of CD80 was activated only in the skin epithelium, leaving the CD80 in immune cells or any other stromal cells intact.

Given that the injected LV also carries a red fluorescent protein (RFP), we first imaged the transduced skin and confirmed good coverage (Figure S2A). Using qPCR and flow cytometry, we observed that at both RNA and protein levels, epithelial CD80 expression was diminished by >80% (Figure S2B and S2C). In order to control for potential impacts of skin microbiota affecting wound healing, we used littermates transduced with the same sgRNA targeting Cd80, but without Cre (needed to activate Cas9 expression). Because Cre has toxicity in mammalian cells, we confirmed that Cre alone and without Cd80 sgRNA LV did not affect re-epithelization or differentiation (Figure S2D and S2E).

With this approach, when we wounded mice that had received in utero Cd80 sgRNA as described above and were conditionally ablated for Cd80 in their skin epithelium (EpiΔCd80) pronounced delays were evident in both the re-epithelization and differentiation phases of the repair process (Figure 3B). Similar to wounds of Cd80 null mice reconstituted with a WT hematopoietic system, which closed by D9, wounds of Krt14 Cre-driven EpiΔCd80 mice closed by D7, i.e. approximately 4 and 2 days, respectively, after control mice. The somewhat faster rate seen in EpiΔCd80 mice versus our bone marrow reconstituted mice was likely because of a small percentage of imperfect gene editing (escapers) within Krt14 Cre-driven skin stem cells.

Taken together, the consistent and pronounced 2–4-day delay in the re-epithelization and differentiation process seen when HFSCs entering the wound bed failed to induce CD80, provided compelling evidence that the immune-modulatory capacity of epithelial stem cells plays a vital role in cutaneous wound repair. Moreover, since the defect was observed when CD80 induction was missing in HFSCs but still present in immune cells, these data further indicated that CD80 is an intrinsic and essential feature of wound-activated HFSCs.

CD80 in HFSCs orchestrates Treg responses at the wound bed to drive re-epithelialization

It was surprising that CD80, typically viewed as a protein exclusive to antigen-presenting immune cells, was found to be both induced in and essential for wound-mobilized epithelial stem cells to efficiently heal skin wounds. The importance of epithelial stem cell-specific CD80 expression was all the more intriguing given that CD80 was only detected in a subset of wound-activated Integrin α5+ migrating HFSCs. Upon antigen presentation by CD80-expressing dendritic cells, CD80 engages its receptor CD28 to provide co-stimulatory signals to T lymphocytes.28 We therefore turned to address the tantalizing possibility that HFSC CD80 might function to modulate the immune microenvironment surrounding the epithelial stem cells in the wound bed to be conducive for the re-epithelialization process.

At five days post-wounding, CD4+ T cells were significantly increased in WT but not in EpiΔCd80 wounds (Figure 4A). In particular, the Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) population, not the Foxp3neg conventional T (Tconv) cells, displayed a striking expansion in WT wounds but not in EpiΔCd80 wounds (Figures 4B and 4C). By contrast, no significant differences in Treg numbers or other features of the immune landscape were observed between the unwounded, homeostatic skin of EpiΔCd80 and control mice (Figure S3A and S3C), indicating that skin stem cell-induced CD80 is particularly important for the wound repair process.

Figure 4: Wound-induced migrating stem cells express CD80 to stimulate local Treg expansion and create a protective niche around the re-epithelializing tissue.

(A to C) Total CD4 T cells (A), Foxp3+ Treg cells (B) and Foxp3- Tconv cells (C) are quantified by flow cytometry in unwounded (UD) or wounded (WD) skin at day5 following injury. n=9 pooled from three independent experiments. Each symbol represents an individual animal. Pooled quantifications from three independent experiments are shown.

D) Schematic and flow cytometry quantification below shows the efficient Treg depletion. IF and quantification shows re-epithelialization (K14+) and differentiation (K10+) in mice with or without Treg depletion.

E) IF images of total GFP+CD3+ Tregs (quantified at right) that infiltrate the skin wounds of WT or Cd80−/− mice reconstituted with bone marrow from Foxp3-GFP Treg reporter mice. Each symbol represents a technical replicate. Representative images and pooled quantifications from two independent experiments are shown.

F) Quantification of the distance between GFP+ Treg cells that enter/expand within the wound bed in (E), from the migrating epithelial stem cells. Each symbol represents a technical replicate.

Unpaired t test, ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001. Scale bars: 100 μm. See also Figure S3.

Tregs are a group of suppressive immune cells that prevent deleterious autoimmunity and dampen inflammation.29,30 Treg depletion has been reported to attenuate the closure of skin wounds after injury,31,32 and hence we were not surprised to see that upon administering diphtheria toxin (DT), re-epithelization and differentiation were defective in Foxp3-promoter-driven diphtheria toxin receptor mice (Figure 4D). However, our new data now pointed to the idea that following injury, wound-mobilized stem cells may function critically in mounting the robust Treg response necessary to facilitate the re-epithelialization process. Moreover, this powerful attribute appeared to be rooted in their ability to induce the expression of CD80 during wound repair.

To further bolster this conclusion, we constructed bone marrow chimeras, reconstituting either irradiated WT or Cd80−/− mice with the bone marrow from Foxp3-GFP reporter mice as a reliable way to visualize the dynamics of Treg responses during wound repair. Immunofluorescence and quantifications of the distance between CD3+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells and K14+ stem cells in de novo regenerating epithelium revealed that strikingly, Tregs accumulate just beneath the epithelium in WT wounds (Figure 4E and 4F). Moreover, this Treg barrier was lost when HFSCs were targeted for Cd80 ablation, underscoring the importance of stem cell-specific CD80 induction in generating and/or maintaining this protective web.

Taken together, these data underscored the importance of not merely Tregs but also CD80-expressing epithelial stem cells in wound repair. Moreover, our data further unearthed an intricate coordination between Tregs and CD80-expressing wound-mobilized epithelial stem cells in governing the immunomodulatory action required for the re-epithelialization process.

Epithelial stem cells prevent neutrophil accumulation near the wound site.

Probing for other changes in the immune response of our wound-induced, epithelial-specific Cd80 ablation (EpiΔCd80), we observed significantly more immune cells (CD45+) compared to control mice (Figure S3B and S3C). In particular, neutrophils accumulated at much higher levels, as evidenced by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 5A) and ultrastructural analyses (Figure 5B). The increase of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in the wounds of EpiΔCd80 mice compared to control mice was also confirmed by flow cytometry quantification (Figure 5C). Immunofluorescence microscopy staining of the wounds at 5 days post-wounding further substantiated the persistence of elevated neutrophils within the wound bed of Cd80 null mice at a time when neutrophils in control wounds had waned concomitant with re-epithelialization (Figure 5D). Interestingly, a recent study reported that Treg cells in the wound are responsible for stopping the neutrophil accumulation and that loss of Treg cells can cause extensive inflammation induced by neutrophils.32 Our data here showed that if epithelial stem cells cannot induce CD80 following injury, they are incapable of orchestrating the immune cell dynamics needed to suppress inflammation and facilitate re-epithelialization at the wound bed.

Figure 5: CD80 is important for skin stem cells to suppress neutrophil infiltration into the re-epithelializing wound bed.

A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the wounded skin from WT or Cd80−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow. Representative images from two independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 100 μm.

B) Ultrastructural images of the wounded skin from WT or Cd80−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow. Arrows point to polymorphonuclear cells. Neutrophils are color-coded in green. The re-epithelialized skin is color-coded in yellow. Representative images from two independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 10 μm.

C) Flow cytometry quantification of the number of Ly6GHi neutrophils within the CD11b+MHCIILow immune population in Day5 wounds on control or EpiΔCd80 mice. Each symbol represents an individual animal. Pooled quantifications from three independent experiments are shown.

D) IF images and quantifications of Ly6G+ neutrophils per mm2 in wounded skin from WT or Cd80−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow. Representative images and pooled quantifications from two independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Unpaired t test, * p<0.05; ** p<0.01.

HFSCs facilitate the expansion of extrathymic Treg cells in the wound.

Treg cells can develop both in the thymus (tTreg) and in the peripheral lymphoid tissues (pTreg).29,30 Therefore, we sought to distinguish whether CD80 molecules presented by HFSCs at the re-epithelialization front act by recruiting more tTreg cells from circulation or alternatively by stimulating the expansion of extrathymic pTreg cells induced during wound repair. To do so, we first designed a Treg fate-mapping assay in which preexisting Treg cells could be distinguished from the extrathymic pTreg cells induced during wound repair.

To this end, we sought to design a series of bone marrow chimeras to perform lineage tracing. First, as a control experiment, we grafted the lethally irradiated Cd80 null and WT mice with congenic marker CD45.1+ bone marrows (Figure S4A). Our data from these mice confirmed that more than 70% of Foxp3+ Treg cells in the wound are CD45.1+ (Figure S4B) and CD80 deficiency mostly cause reductions in donor derived CD45.1+ Treg cells (Figure S4C and S4D). By contrast, the CD45.1neg tissue resident Treg cells remaining in the tissue after irradiation were not obviously affected by the absence of CD80 in HFSCs (Figure S4C and S4D).

Based on this premise, we next reconstituted the hematopoietic system of the WT or Cd80 null mice by transplanting extracted bone marrow from Foxp3-GFP-CreER; Rosa26-LSL-tdTomato mice. In these chimeric mice, tamoxifen treatment before wounding induced the expression of the fate-mapping marker, tdTomato, and labeled all pre-existing Foxp3+GFP+ Treg cells with tdTomato (double-positive, DP). Thus, following tamoxifen exposure and subsequent wounding, those pre-existing Treg cells that entered the skin from the circulation were double-positive, while those induced after skin injury were marked by GFP alone (single-positive, SP) (Figure 6A). Interestingly, five days after wounding, the percentage and numbers of GFP single-positive Treg cells increased significantly in WT wounds, but not in the wounds where HFSCs cannot activate CD80 (Figure 6A). These results provided compelling evidence that the CD80 expressed by wound-mobilized HFSCs is critical for stimulating the expansion of peripherally induced Treg cells after they arrived in the skin.

Figure 6. CD80 expression by migrating epithelial stem cells promotes the expansion of extrathymically-induced Treg cells during wound healing.

A) Schematic of experimental design and flow cytometry quantification of the frequency and number of preexisting (double positive: Tomato+GFP+) and newly induced (single positive: GFP+Tomato−) Treg cells in day 5 wounds (n=3 in each experiment). Representative flow cytometry plots and pooled quantifications from two independent experiments are shown.

B to D) IF images and quantification of re-epithelization (B), flow cytometry quantifications of the Treg cells (C) and neutrophils (D) in the Day5 wounds from skins of Rag2−/− mice that were reconstituted with Foxp3GFP control or Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP bone marrow. Scale bar: 100 μm. Representative images and pooled quantifications from two independent experiments are shown.

E to G) Image quantification of re-epithelization (E) and flow cytometry quantifications of the Treg cells (F) and neutrophils (G) in the Day5 wounds from skins of WT or Cd80−/− mice that were reconstituted with Foxp3GFP control or Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP bone marrow. Each symbol is an individual animal. Pooled data from two independent experiments are shown.

H) Flow cytometry quantifications of Ki67+ Treg cells in Day5 wounds from skins of control or EpiΔCd80 mice (in vivo) or after co-culturing the GFP+ Treg cells with WT or Cd80−/− HFSCs for three days.

I to K) Flow cytometry quantification of Foxp3 induction in CD4 T cell after: I) naïve CD4 T cells from OT II mice are co-cultured with WT, Cd80−/−, or MHCII −/− HFSCs that are pre-loaded with OVA protein or OVA peptides in the presence of IL2 and TGFβ; J) CD4+ GFPneg CD44Hi CD62LLow T cells are isolated from wound draining lymph nodes in Foxp3-GFP mice and co-cultured with WT or Cd80−/− HFSCs in the presence of IL2 and TGFβ; K) naïve CD4 T cells are activated with anti-CD3/CD28 for three days, followed by co-culturing with WT or Cd80−/− HFSCs and TGFβ is only added together with HFSCs. Representative data from one of the three independent experiments are shown.

two-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction for A-G, unpaired t test for H to K. **** p<0.0001 *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. See also Figure S4 and S5.

Extrathymic induction of Treg cells from CD4+ T cells depends upon a TGFβ responsive element within the Foxp3 enhancer referred to as CNS1 (conserved non-coding sequence 1), but this element is dispensable for the tTreg cell maturation that occurs within the thymus.33 To further challenge a model in which wound-activated CD80-expressing HFSCs stimulate the local expansion of newly induced pTreg cells, we irradiated B and T cell deficient Rag2−/− mice and reconstituted them with bone marrow from strain-matched Foxp3GFP(Foxp3tm2Ayr) control or Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP mice.33 Upon wounding, the mice reconstituted with Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP bone marrow displayed defects in re-epithelialization and differentiation that resembled those of EpiΔCd80 mice (Figure 6B). Additionally, immune profiling showed that in contrast to the wounds of mice reconstituted with Foxp3GFP control bone marrow, these wounds were marked by a paucity of Treg cells (Figure 6C) and failed to dampen neutrophil infiltration into the wound bed (Figure 6D). Finally, irradiated Cd80−/− mice that had been reconstituted with bone marrow harboring the genomic CNS1 deletion showed a similar degree of Treg deficiency following wounding. As expected, reconstitution of irradiated Cd80−/− mice with bone marrow harboring the genomic CNS1 deletion did not result in any additional defects in reepithelization, Treg induction, and neutrophil reduction (Figure 6E, 6F and 6G).

HFSCs trigger Treg induction from pre-activated CD4 T cells in a CD80 dependent, but MHCII-independent manner.

So far, our data pointed to the view that extrathymic pTregs expand as a consequence of CD80+ HFSC stimulation, and are the main population responsible for protecting HFSCs during wound healing. Next, we sought to dissect the underlying basis of this close interaction between HFSCs and Treg cells. The simplest possibility was that the pTregs had originated from the peripheral lymphoid organs, and once recruited into the wound, CD80 on HFSCs provided co-stimulatory signals that enhanced their proliferation. Interestingly, however, among the Treg cells that infiltrated the wounded skin, Ki67 levels were similar between control and EpiΔCd80 mice (Figure 6H). This was also the case when we wounded the Foxp3-GFP reporter mice, isolated GFP+ Treg cells from the wound-draining lymph nodes, and co-cultured them with HFSCs purified from either WT or Cd80−/− mice (Figure 6H).

In the peripheral lymphoid organs, generation of pTregs from naïve CD4 T cells is dependent on tolerogenic CD80+MHCII+ dendritic cells providing antigen presentation and co-stimulation. Given that a subset of HFSCs that migrate into the wound also express both MHCII and CD80, we asked whether HFSCs might be able to directly induce naïve CD4 T cells to differentiate into Tregs. To test this possibility, we isolated naïve CD4 T cells from OTII mice, and co-cultured them with the HFSCs in the presence of IL2 and TGFβ. Importantly, the HFSCs were preloaded with either the OVA protein or the OVA-derived peptide (323–339) which is recognized by T cell receptors of OTII mice when presented on MHCII complex. However, no Treg induction was seen in these co-cultures (Figure 6I). We also ablated class II MHCs first in the basal skin epithelium using Krt14-Cre; MHCIIflox/flox mice or specifically in HFSCs using Sox9CreER; MHCIIflox/flox mice (EpiΔMHCII). Whether we targeted MHCII ablation during embryonic development or just before wounding, we observed no overt phenotypic differences in re-epithelialization, Treg induction or neutrophil accumulations in both models (Figure S5). From these data, we concluded that although MHCII is expressed by HFSCs, it is dispensable for stem cell-mediated Treg induction and wound repair, and in this way differed from CD80. Taken together, our MHCII results were in agreement with our co-culture result that HFSCs cannot induce naïve CD4 T cells to differentiate into Tregs.

Most CD4 T cells encountered by HFSCs in the wound bed should have already been activated in the lymph nodes immediately after injury. We therefore turned to the notion that activated T cells might be able to respond to CD80+ HFSCs in the wound bed and elevate Foxp3 expression. To test this hypothesis, we isolated Foxp3-GFPnegCD62LLowCD44Hi CD4 T cells from the draining lymph nodes of wounded Treg reporter mice and co-cultured them with HFSCs isolated from WT or CD80 null mice. Interestingly, compared to the CD80 null HFSCs, WT HFSCs induce higher Foxp3 expression in CD4 T cells (Figure 6J). To further test our hypothesis, we isolated naïve CD4 T cells, pre-activated these CD4 T cells with CD3/CD28 antibody, and only exposed these newly activated T cells to TGFβ after they were activated (Figure 6K). Interestingly, when we added WT HFSCs to this culture, the activated CD4 T cells can re-gain their capacity to respond to TGFβ and maintain Foxp3 expression in a manner dependent upon sustained presence of HFSC CD80 (Figure 6K).

Overall, these results suggest that CD80 presented by wound-activated epithelial stem cells can alter the differentiation potential of activated CD4 T cells and trigger TGFβ-sensitive (CNS1) enhancer activity within the Foxp3 locus. In doing so, the stem cells weave a protective Treg web that specifically envelopes them at the wound bed until they have repaired the skin’s barrier.

HFSCs balance inflammation and immune tolerance during wound repair

Recently, it was observed that Treg depletion, followed by mechanical abrasion of the skin, leads to a raging inflammatory neutrophil response in the wound bed. The increased neutrophil accumulation in these wounds seemed to be fueled, at least in part, by epithelial cell production of the neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL5.32 Advancing this knowledge further, we traced the source of epithelial Cxcl5 to the integrin α5+ HFSCs that mark the re-epithelializing wound front (Figure 1C) and that ironically displays CD80 to modulate Treg cells (Figure 7A). ATAC-seq of the isolated HFSCs further revealed marked changes in the accessibility of the Cxcl5 locus following injury (Figure 7B). As shown by qPCR analysis, Cxcl5 transcripts were rapidly and transiently elevated by >300 fold in HFSCs within a single day after wounding (Figure 7C).

Figure 7: Skin stem cells balance inflammation and Treg-mediated immune tolerance during wound repair.

A) UMAP plot showing that Cxcl5 is specifically activated in the Integrin α5+ epithelial stem cells (see Figure 1D) that have migrated into the wound.

B) ATAC-seq peak showing the accessibility status of the Cxcl5 locus in lineage traced epithelial stem cells sorted from unwounded or D3 post-wounded Sox9-lineage traced epithelial stem cells.

C) qPCR quantifications of Cxcl5 expression in mobilized HFSCs, macrophages (MAC)/dendritic cells (DC), and neutrophils (Neu)/monocytes (Mo) isolated from Day1 wounds.

D) qPCR quantifications of Cxcl5 expression in Integrin α5+ epithelial stem cells isolated from Day4 wounds of WT or EpiΔCd80 mice.

E) Images and quantification of K14+ epithelium (green) and RNAScope probing the transcript of Cxcl5 (red) in wounds from skins of Rag2−/− mice reconstituted with Foxp3GFP control or Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP bone marrow. Each symbol represents a technical replicate. Representative images and pooled quantification from two independent experiments are shown. Scale bar: 100 μm.

F and G) Flow cytometry quantifications of IL17 production in (F) TCRβ+CD4+ T cells or (G) TCRβ-TCRγδ+ T cells in Day 4 wounds from skin of WT or Cd80−/− mice receiving WT bone marrow. Each symbol represents an individual animal. Pooled quantifications from two independent experiments are shown.

H and I) Schematic, IF images and quantification showing re-epithelization process and differentiation after control or CXCL5 Ab treatment of Cd80−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow. Each symbol represents a technical replicate. Representative images and pooled quantifications from one of the two independent experiments are shown.

Unpaired t-test, **** p<0.0001 *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Collectively, our results suggested that paradoxically, wound-activated skin stem cells are the major population that induces CXCL5 to stimulate neutrophil recruitment and inflammation. Interestingly, while Cxcl5 mRNA levels waned in control animals by day 4 post-wounding, Cxcl5 remained higher in mice whose HFSCs were ablated for Cd80 (Figure 7D). Higher levels of Cxcl5 transcripts were also observed in the wounds of Rag2 null mice reconstituted with Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP compared to control bone marrow. This was corroborated by RNAScope used to analyze Cxcl5 levels in situ showing that Cxcl5 transcripts accumulated mainly in K14+ skin epithelial cells that had migrated into the wound bed (Figure 7E). This result suggests that the increased CXCL5 seen in CD80-deficient migratory HFSCs might be triggered by the corresponding paucity of pTregs in the wound bed (Figure 7E). These observations further bolstered the conclusion that the migratory HFSCs are the orchestrators balancing inflammation and tolerance during the wound repair.

Our findings were intriguing in light of a recent study which suggested that Treg cells reduce neutrophil accumulation in cutaneous wounds by blocking IL17 production in T cells.32 As our wounded EpiΔCd80 mice showed a decrease in Tregs and increase in neutrophils, we wondered if IL17 production might be elevated in these lymphocytes. Although we did not observe increased IL17 in CD4 T cells (Figure 7F), we did find that loss of CD80 in HFSCs resulted in enhanced IL17 production in γδT cells (Figure 7G). Our results are consistent with recent reports that γδT cells are the main source of IL-17 after tissue injury.9,34,35 Together, our results suggest that CD80 presentation by epithelial cells is required to stimulate Tregs, which in turn may suppress neutrophil-mediated inflammation in the wound by dampening down γδT cell-mediated IL17 production and keeping CXCL5 secretion by wound-edge epithelial cells in check.

Finally, to test whether persistence of excess neutrophil accumulation in the wound bed was the root cause of impaired re-epithelialization and differentiation upon CD80 loss within HFSCs, we administered anti-CXCL5 antibody intraperitoneally to Cd80 null mice on day three and day four post-wounding.32 Notably, this suppressed the neutrophil influx (Figure 7H) and significantly rescued the re-epithelialization and differentiation defects in these mutant mice (Figure 7I).

Cumulatively, these data placed the epithelial stem cells at the center stage of immune modulation and balancing inflammation and tolerance. Our new findings provided compelling evidence that as epithelial stem cells are activated and begin migrating into the wound bed, they express CXCL5 to funnel neutrophils into the wound bed to efficiently guard against infection until a new barrier is formed. By activating CD80, these mobilized stem cells also generate a web of surrounding Treg cells which in turn provides a buffer zone between the neutrophils and the epithelial stem cells to protect them from the collateral damage otherwise inflicted by the inflammatory neutrophils which allows re-epithelialization to occur.

Discussion

HFSCs comprise a vital cellular reservoir for regenerating the skin.2,36 Under normal skin homeostasis, HFSCs reside in each follicle within a protective, niche replete with an inner layer of protective barrier cells that guards against pathogen entry from the HF orifice to the skin’s surface. The skin is also subjected to frequent shallow wounds, compromising the skin’s surface barrier and mobilizing nearby HFSCs to exit their niches and migrate into the wound bed to participate in epidermal repair. There, they encounter a highly inflammatory environment that is essential to contain pathogen infections.2,32,36

It has long been appreciated that inflammation and epithelial repair are incompatible. The traditional view is that these events happen sequentially, although if true, this would generate a window of vulnerability where inflammation would be curbed and healing incomplete. Here, we show that not only can these two incompatible processes co-exist in harmony during a wound response, but in addition, they do so through a dynamic molecular feature of these tissue stem cells. Interestingly, when the skin stem cells migrate into the wound bed, they sense the damaged tissue environment and respond by weaving a protective niche of regulatory T cells around them. By suppressing inflammation locally, the Tregs shield the skin stem cells inside this temporary web, enabling the stem cells to repair the wound and restore the skin barrier. Outside these confines, the neutrophils and macrophages can continue clearing debris and guarding against pathogens until the wound is healed. By expanding the local Treg population to build a Treg barrier against neutrophils, the stem cells at the migrating front of the wound bed can protect themselves from attack even as they secrete the neutrophil attractant CXCL5 to clear out invading microbes.

We discovered that to perform these extraordinary feats, wound-mobilized skin epithelial stem cells upregulate co-stimulatory cell-surface immunomodulatory proteins like CD80, which until recently, was thought to be exclusive to classic antigen-presenting immune cells. We stumbled upon CD80 while searching for how cancer stem cells of skin squamous cell carcinomas become resistant to cytotoxic T cell attack. In that study, we showed that CD80 was induced in the cancer stem cells in response to the enhanced TGFβ within the tumor microenvironment. There, CD80 acted to dampen the potency of cytotoxic T cells, thereby protecting the cancer stem cells against immunotherapy-driven attacks.20

Here, we found that in a different setting, namely the TGFβ-enriched environment of damaged tissue, CD80 was again induced, this time within the normal epithelial stem cells that enter the wound bed to repair the injury. In this situation, CD8 T cells were a minimal constituent of the normal and wounded skin (Figure S3). In contrast to the cancerous state, expression of CD80 by the stem cells in a wound instead played a crucial role in orchestrating the expansion of newly induced extrathymic pTreg cells (Figure 6). This interaction between HFSCs and T cells appeared to buffer the infiltration and accumulation of pro-inflammatory immune cells, such as neutrophils, thereby allowing the HFSCs to generate new epidermis and restore the skin barrier. It has long been postulated that adult tissue stem cells are vulnerable and need to be protected by immune-privileged niches. Our study finds that adult epithelial stem cells are an integral part of the immune-modulatory network in the skin. This represents a significant paradigm shift in our understanding of how stem cells can drive immune responses and tissue regeneration.

Although the expansion of pTreg cells has previously been attributed to signals derived from antigen-presenting immune cells, our study refocuses the attention to epithelial stem cells, which as we show here can co-opt the canonical immune-modulatory machinery in response to inflammation. For barrier tissues like epidermis, re-epithelialization must begin quickly, as keeping microbes out cannot be accomplished until the skin barrier is restored. However, the concomitant generation of an inflammatory environment poised to fight infections is diametrically opposed to barrier restoration. By involving injury-activated stem cells in the conversion of infiltrating effector T cells to pTreg cells, Tregs can be specified and expanded at the right time and place to form a transient immunosuppressive web to protect the stem cells within the wound bed and allow them to repair the barrier.

In closing, the intimate interaction between the wound-activated stem cells and their ability to stimulate pTregs expansion naturally focuses wound-induced pTregs towards creating a local neutrophil-suppressive, repair-conducive microenvironment at the site of re-epithelialization. This web protects the stem cells from the harsh inflammatory surroundings of the broader wound site. This intricate, stem cell-driven orchestration of immunity during wound repair has significant implications for how we think about pathogenic immune responses.

Limitations of the study.

Imaging analysis also highlighted the significant distance between HFSCs and Treg cells in the wound bed. Thus, future studies should investigate whether HFSCs only briefly or transiently interact with T cells in the wound. Additionally, It has been recently reported that intestinal and epidermal stem cells, and some other tissue cells express class II MHC and that presence of MHCII can increase cytokine production from tissue resident CD4 T cells, which, in turn, promotes stem cell functions under normal homeostatic conditions.22,23,37 Here, we learned that during a wound response, when HFSCs migrate out of their natural niche and face the robust inflammation of the wound bed, they also express MHCII. However, during wound repair, MHCII appeared to be dispensable for HFSCs to modulate Treg cells, leaving only the CD80-mediated signal to actively sculpt a temporary protective niche comprised of newly generated Treg cells. That said, it remains possible that MHCII molecules may have other important functions during wound repair and future studies are necessary to further explore their roles in epithelial stem cells.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for reagents and resources should be directed to the lead contact, Yuxuan Miao (miaoy@uchicago.edu)

Materials availability

This study did not generate unique new reagents.

Data and code availability

Bulk RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the Key Resource Table.

Microscopy data and flow cytometry data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code and any additional information or data in this paper will be available from the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| APC anti-mouse CD4, rat monoclonal (clone GK1.5) | Biolegend | Cat# 100412; RRID: AB_312697 |

| PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD4, rat monoclonal (clone GK1.5) | Biolegend | Cat# 100422; RRID: AB_312707 |

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD8b, rat monoclonal (clone YTS156.7.7) | Biolegend | Cat# 126620; RRID: AB_2563951 |

| AF700 anti-mouse CD45, rat monoclonal (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat# 103128; RRID: AB_493715 |

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD45, rat monoclonal (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat# 103116; RRID: AB_312981 |

| PE anti-mouse CD45, rat monoclonal (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat# 103106; RRID: AB_312971 |

| FITC anti-mouse CD45, rat monoclonal (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat# 103108; RRID: AB_312973 |

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD44, rat monoclonal (clone IM7) | Biolegend | Cat# 103028; RRID: AB_830785 |

| BV711 anti-mouse CD62L, rat monoclonal (clone MEL-14) | Biolegend | Cat# 104445; RRID: AB_2564215 |

| PE anti-mouse CD45.1, mouse monoclonal (clone A20) | Biolegend | Cat# 110707; RRID: AB_313496 |

| PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD45.1, mouse monoclonal (clone A20) | Biolegend | Cat# 110730; RRID: AB_1134168 |

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD45.2, mouse monoclonal (clone 104) | Biolegend | Cat# 109824; RRID: AB_830789 |

| Pacific Blue anti-mouse CD11b, rat monoclonal (clone M1/70) | Biolegend | Cat# 101224; RRID: AB_755986 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD11b, rat monoclonal (clone M1/70) | Biolegend | Cat# 101228; RRID: AB_893232 |

| PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD11c, armenian hamster monoclonal (clone N418) | Biolegend | Cat# 117318; RRID: AB_493568 |

| APC anti-mouse CD80, Armenian hamster monoclonal (clone 16-10A1) | Biolegend | Cat# 104714; RRID: AB_313135 |

| AF700 anti-mouse I-A/I-E, rat monoclonal (clone M5/114.15.2) | Biolegend | Cat# 107622; RRID: AB_493727 |

| PE/Cy7 anti-mouse integrin α5, rat monoclonal (clone 5H10-27 (MFR5) | Biolegend | Cat# 103816; RRID: AB_2734165 |

| BV711 anti-mouse TCR β Chain, armenian hamster monoclonal (clone H57–597) | Biolegend | Cat# 109243; RRID: AB_2629564 |

| PE anti-mouse TCR γ/δ, armenian hamster monoclonal (clone GL3) | Biolegend | Cat# 118108; RRID: AB_313832 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse Ki67, rat monoclonal (clone 16A8) | Biolegend | Cat# 652424; RRID: AB_2629531 |

| PE anti-mouse IL-2, rat monoclonal (clone JES6-5H4) | Biolegend | Cat# 503808; RRID: AB_315302 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse IL17A, rat monoclonal (clone TC11–18H10.1) | Biolegend | Cat# 506920; RRID: AB_961384 |

| FITC anti-mouse IFN-γ, rat monoclonal (clone XMG1.2) | Biolegend | Cat# 505806; RRID: AB_315400 |

| FITC anti-mouse Ly-6C, rat monoclonal (clone HK1.4) | Biolegend | Cat# 128006; RRID: AB_1186135 |

| PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse Ly-6C, rat monoclonal (clone HK1.4) | Biolegend | Cat# 128011; RRID: AB_1659242 |

| PE anti-mouse Ly-6G, rat monoclonal (clone 1A8) | Biolegend | Cat# 127608; RRID: AB_1186099 |

| BV711 anti-mouse CD64, mouse monoclonal (clone X54-5/7.1) | Biolegend | Cat# 139311; RRID: AB_2563846 |

| APC anti-mouse Foxp3, rat monoclonal (clone FJK-16s) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 17-1577-82; RRID: AB_469457 |

| Biotin conjugated anti-CD11b, rat monoclonal (clone M1/70) | Biolegend | Cat# 101204; RRID: AB_312787 |

| Biotin conjugated anti-CD45, rat monoclonal (clone 30-F11) | Biolegend | Cat# 103104; RRID: AB_312969 |

| Biotin conjugated anti-CD31, rat monoclonal (clone MEC13.3) | Biolegend | Cat# 102504; RRID: AB_312911 |

| Biotin conjugated anti-CD117, rat monoclonal (clone 2B8) | Biolegend | Cat# 105804; RRID: AB_313213 |

| Biotin conjugated anti-CD140a, rat monoclonal (clone APA5) | Biolegend | Cat# 135910; RRID: AB_2043974 |

| APC armenian Hamster IgG Isotype Control (clone: HTK888) | Biolegend | Cat# 400911; RRID: AB_2905474 |

| AF700 rat IgG2b κ Isotype Control (clone: RTK4530) | Biolegend | Cat# 400628; RRID: AB_493783 |

| Purified anti-mouse CD3, rat monoclonal (clone 17A2) | Biolegend | Cat# 100202; RRID: AB_312659 |

| Anti-GFP, rabbit polyclonal | Abcam | Cat# ab290; RRID: AB_2313768 |

| Purified anti-Keratin 14, chicken polyclonal (clone Poly9060) | Biolegend | Cat# 906004; RRID: AB_2616962 |

| Purified anti-Keratin 10, rabbit polyclonal (clone Poly19054) | Biolegend | Cat# 905404; RRID: AB_2616955 |

| Purified anti-integrin α5, rat monoclonal (clone 5H10–27 (MFR5)) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 553319; RRID: AB_394779 |

| Purified anti-Ly6G, rat monoclonal (clone 1A8) | Biolegend | Cat# 127602; RRID: AB_1089180 |

| Anti-mouse CD80, goat polyclonal | R&D systems | Cat# AF740, RRID: AB_2075997 |

| AF488 anti-rabbit IgG, donkey polyclonal | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat# 711-545-152; RRID: AB_2313584 |

| AF488 anti-chicken IgG, donkey polyclonal | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat# 703-545-155; RRID: AB_2340375 |

| AF488 anti-goat IgG, donkey polyclonal | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat# 705-545-147; RRID: AB_2336933 |

| AF647 anti-rabbit IgG, donkey polyclonal | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat# 711-605-152; RRID: AB_2492288 |

| AF647 anti-chicken IgG, donkey polyclonal | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat# 703-605-155; RRID: AB_2340379 |

| RRX anti-rat IgG, donkey polyclonal | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | Cat# 712-295-150; RRID: AB_2340675 |

| CD3e monoclonal antibody (clone 145-2C11) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 14-0031-82; RRID: AB_467049 |

| CD28 monoclonal antibody (clone 37.51) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 16-0281-82; RRID: AB_468921 |

| Mouse CXCL5 antibody, rat monoclonal (clone 61905) | R&D Systems | Cat# MAB433; RRID: AB_2086587 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Tamoxifen | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T5648 |

| Diptheria toxin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D0654 |

| TRIzol | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 15596026 |

| Liberase | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 5401020001 |

| Deoxyribonuclease I from bovine pancreas | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D4263 |

| Zombie Aqua viability dye | Biolegend | Cat# 423101 |

| Cell stimulation cocktail | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 00-4970-03 |

| Brefeldin A | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 00-4506-51 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 21985-023 |

| HEPES buffer | Corning | Cat# 25-060-C1 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 15140122 |

| MEM | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 11140–050 |

| Sodium pyruvate | Corning | Cat# 25-000-C1 |

| Gentamicin | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 15710-064 |

| Mitomycin C | Fisher Bioreagents | Cat# BP25312 |

| OVA 323–339 | InvivoGen | Cat# vac-isq |

| DQ Ovalbumin | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# D12053 |

| Recombinant Mouse IL-2 | R&D Systems | Cat# 402-ML-020 |

| Mouse TGFβ | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5231LF |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| MojoSort mouse CD4 naive T cell isolation kit | Biolegend | Cat# 480040 |

| Foxp3/Transcriptional factor staining buffer set | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 00-5521-00 |

| RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat# 323100 |

| RNAscope Probe-Mm-Cxcl5-C1 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat# 467441 |

| Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kit | Zymo Research | Cat# 11-331 |

| NEBNext Single Cell/Low input RNA library prep kit for Illumina | New England Biolabs | Cat# E6420S |

| Illumina Tagment DNA Enzyme and Buffer kits | Illumina | Cat# 15027866 |

| MiniElute PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 28004 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-sequencing data | This paper | GEO: GSE220241 |

| ATAC-sequencing data | This paper | GEO: GSE220241 |

| Single cell RNA-sequencing data | Haensel et al.26 | GEO: GSE142471 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: K14CreER | Fuchs lab | N/A |

| Mouse: K14cre | Fuchs lab | N/A |

| Mouse: Sox9CreER | Fuchs lab | N/A |

| Mouse: Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP | Rudensky lab | N/A |

| Mouse: Foxp3tm2Ayr | Rudensky lab | N/A |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 000664 |

| Mouse: B6;129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 007905 |

| Mouse: B6.129S4-Cd80tm1Shr/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 003611 |

| Mouse: B6;129-Gt(ROSA) 26Sortm1(CAG-cas9*,-EGFP)Fezh/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 248857 |

| Mouse: B6.129(Cg)-FOXP3tm3(DTR/GFP)Ayr/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 016958 |

| Mouse: Foxp3CreER-GFP | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 016961 |

| Mouse: B6(Cf)-Rag2tm1.1Gn/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 008449 |

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 004194 |

| Mouse: B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/Boyd | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 002014 |

| Mouse: B6.129X1-H2-Ab1 tm1Koni/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 013181 |

| Mouse: B6.129S2-H2dlAb1-Ea/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 003584 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Mouse Cd80 sgRNA1: CATCAATACGACAATTTCCC | Miao et al.20 | N/A |

| Mouse Cd80 sgRNA2: CGTGTCAGAGGACTTCACCT | Miao et al.20 | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLKO-H2BGFP-CD80 sgRNA | Miao et al.20 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fuji (Image J) | Fuji (Image J) | https://fiji.sc/ |

| FlowJo | FlowJo | https://www.flowjo.com |

| Biorender | Biorender | www.biorender.com |

| Cutadapt (v3.2) | Martin et al.39 | https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/v3.4/ |

| Pseudo-aligner Kallisto (v0.44.0) | Bray et al.40 | https://github.com/pachterlab/kallisto |

| DESeq2 R package (v1.30.0) | Love et al.41 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| clusterProfiler package | Yu et al.42 | https://guangchuangyu.github.io/software/clusterProfiler/ |

| MSigDB (Molecular signature database, v7.4) | Broad Institute | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb |

| Bowtie2 (v2.3.4.3) | Langmead and Salzberg.43 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/owtie2/index.shtml |

| Picard (v2.18.7) | Broad Institute | http://github.com/broadinstitute/picard/releases/tag/2.7.1 |

| DeepTools | Ramirez et al.44 | https://pypi.org/project/deepTools/ |

| Gviz package | Hahne et al.45 | https://github.com/ivanek/Gviz |

| MACS2 (v2.2.7.1) | Zhang et al.46 | https://pypi.org/project/MACS2/ |

| Bedtools (v2.30.0) | Quinlan et al.47 | https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ |

| FeatureCounts (v1.5.3) | Liao et al.48 | https://subread.sourceforge.net |

| Seurat (v.4.1.0) | Hao et al.49 | https://github.com/satijalab/seurat |

| R | R Project | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| RStudio | Posit | https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/ |

| Other | ||

| BD FACSAria II Cell Sorter | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| BD LSR II Analyzer | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| BD LSR-Fortessa analyzer | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| Axio Observer Z1 | Zeiss | N/A |

| Leica Stellaris 8 Confocal microscope | Leica | N/A |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANTS DETAILS

Mice

Sox9CreER, K14CreER and K14Cre (Fuchs Lab) mice have been previously described and were backcrossed to C57/BL6J background for ten generations. Foxp3GFP(Foxp3tm2Ayr) and Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP mice were obtained from the Rudensky Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Wild-type C57BL/6J, B6;129S6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (R26-LSL-tdTomato), B6.129S4-Cd80tm1Shr/J (CD80−/−), B6;129-Gt(ROSA) 26Sortm1(CAG-cas9*,-EGFP)Fezh/J (R26-LSL-Cas9), B6.129(Cg)-FOXP3tm3(DTR/GFP)Ayr/J (Foxp3-DTR), FOXP3tm9(EGFP/cre/ERT2)Ayr/J (Foxp3-CreER-GFP), B6(Cf)-Rag2tm1.1Gn/J (RAG2−/−), B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/Boyd (CD45.1), B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb) 425Cbn/J (OTII), MHCIIfl/fl (B6.129X1-H2-Ab1 tm1Koni/J) and MHCII- (B6.129S2-H2dlAb1-Ea/J) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Tregs were depleted in Foxp3-DTR mice using a modified protocol.20 Briefly, diphtheria toxin (DT, Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted to 2.5 μg/ml, and 200 μl (0.5 μg) was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into WT or Foxp3-DTR mice at Day −3, 0 and 3. On day 0, mice were wounded. Neutrophils were depleted via i.p. injection with 50 μg CXCL5 monoclonal neutralizing antibody (R&D systems; mAb 433) at days 3 and 4 post-wounding. To treat mice with tamoxifen, a daily i.p. injection of 100 μg for three consecutive days was performed. All mice were maintained in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-an accredited animal facility. Procedures were performed using IACUC-approved protocols that adhere to NIH standards. The animals were maintained and bred under specific-pathogen free conditions at the University of Chicago and the Comparative Bioscience Center at Rockefeller University. All the procedures follow the Guide of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Cell Lines

HEK293T cells were used for packaging lentivirus and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL streptomycin/penicillin, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate.

METHOD DETAILS

In utero lentiviral transduction

Cd80 was specifically edited in the skin of K14Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice via the ultrasound-guided in utero injection of the lentivirus carrying Cd80 sgRNA and PGK-H2B-RFP reporter. Briefly, pregnant females will be anesthetized using isoflurane gas, and placed onto a heated platform, the female’s abdomen will be cleaned of hair using Nair (a common hair removal product for humans, and commonly used on mice to remove hair), and a ventral midline abdominal incision will be made to expose a small part of the uterine horn; a 10cm tissue culture dish, with a hole in the center, will be placed over the incision, and the exposed part of the uterine horn will be gently pulled into the dish, through a slit in the membrane covering the hole; the dish will be filled with PBS to prevent dehydration of the exposed tissue and embryo; the ultrasound transducer will be placed over the embryo and upon identification of the amniotic cavity, a guided microinjection glass capillary loaded with the lentivirus (109 CFU), will be inserted into the amniotic cavity, and the lentivirus injected into the amniotic fluid at a volume of 1 μl to transduce the skin progenitors; four to six embryos will be injected on each side of the uterine horn, and the incision will be closed with catgut suture and wound clips. The pregnant female will be allowed to recover and give birth to lentivirus-transduced pups.27 Once the virus is integrated (~24 hours post-infection), the DNA carried by the lentivirus is stably propagated to the progeny of the epithelial progenitors.27

Bone marrow chimera construction

Recipient mice were lethally irradiated (900 rads), which ensures the depletion of endogenous hematopoietic stem cells. Radiation was delivered in two equal doses (450 rads each), 4 hours apart, to minimize damage to gastrointestinal and pulmonary cells. Bone marrow cells were isolated from donor femurs, and 0.5~1 × 107 bone marrow cells in 100 μl PBS were adoptively transferred through the tail vein or retroorbital injection into irradiated recipient mice. Six to eight weeks post-transplantation, recipient mice were used for experiments.

Partial thickness wound

Mice were wounded in telogen. Briefly, mice were shaved, hair was removed using depilatory cream, and a Dremel drill head was used to gently scrape the back skin of anesthetized mice. To standardize the wound depth, the number of touches performed with the Dremel drill was determined by inspecting the wounded skin for the first signs of erythema and pinpoint bleeding. This method removes the epidermis and upper HF, including most infundibulum and isthmus cells, but leaves the HF bulge intact.

Flow Cytometry

To isolate single cell suspensions from wounded skin for analysis or sorting, the wound was placed in cold PBS for 15 minutes to remove the scab. The remainder of the wounded tissue was minced in digestion media: RPMI (Thermo Fisher) with HEPES (1:40, Thermo Fisher), MEM 100X (1:100, Thermo Fisher), sodium pyruvate (1:100, Thermo Fisher), penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml), gentamicin (1:500, Thermo Fisher), ß-mercaptoethanol (1:1000). The tissue was digested with Liberase (25 μg/ml) (Roche) for 120 minutes at 37 °C with an adapted protocol.4 Single-cell suspensions were obtained, and cells were stained using an antibody cocktail prepared at predetermined concentrations in a staining buffer (PBS with 5% FBS and 1% HEPES). For immune profiling of the wound, fixable Live/Dead Cell Stain Kit was used to exclude dead cells. Stained cells were analyzed with BD Fortessa and LSR II Analyzer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed by FlowJo software and the number of various immune populations were calculated and normalized as “immune cell number per wound” for quantifying immune cells only in wounds or “immune cell number per cm2” for comparing immune cell numbers between unwounded and wounded skin. For RNA-seq and ATAC-seq, the single-cell suspensions were sorted after adding DAPI on BD FACSAriaII SORP running BD FACSDiva software.

To isolate HFSCs for in vitro co-culture assay, the back skins of WT C57/BL6J, Cd80−/− and MHCII- mice were dissected and scraped with a blunt scalpel to remove excess fat. Skin was placed with the dermal side down in 0.25% trypsin/EDTA for 30 minutes. A single cell suspension was prepared and stained with antibody cocktail and HFSCs were sorted after adding DAPI. To FACS analysis of the CD80 expression levels on HFSCs post in utero injection, the single cell suspensions were isolated from the back skins of Krt14Cre; Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 or Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 mice whose skin epithelium had been specifically transduced with sgRNA. To obtain CD4+GFP−CD44HiCD62LLow T cells for in vitro co-culture, the skin draining lymph nodes were collected from Foxp3-GFP/DTR mice on day2 post-wounding.

Immunofluorescence and RNA scope staining

Wounded and unwounded skin were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde immediately after dissection for 1 hour at 4 °C and washed thrice in PBS. The tissue was incubated in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4 °C overnight. Tissue was then embedded in OCT (Tissue Tek), frozen, and sectioned (12–20um). Cryosections were permeabilized, blocked, and stained with the following primary antibodies: K10 (Rabbit, 1:1000, Biolegend), K14 (Chicken, 1:1000, Biolegend), mCD80 (Goat, 1:50, R&D), GFP (Rabbit, 1:1000, Abcam), Ly6G (Rat, 1:500, Biolegend), integrin a5 (Rat, 1:100, BD). The slides were then stained with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 647 and Rhodamine Red-X (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and imaged on Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 equipped with ApoTome.2 or Leica Stellaris 8 Laser Scanning Confocal microscope. For the RNA scope staining, cyrosections were dehydrated, performed with hydrogen peroxide and Protease III, hybridized with AMPs and developed the HRP-C1 channel with the cxcl5 probe according to the RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit Assay (ACDbio). Immediately after RNA labeling, the cytosections were stained with the primary antibody against K14 and the related secondary antibody. The images were collected by Leica Stellaris 8 Confocal microscope and analyzed using Fiji/ImageJ software.

Electron Microscopy

Skin samples were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde, 4% PFA, and 2 mM CaCl2 in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for over1 hour at room temperature, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, and processed for Eponate 12 embedding. Ulltrathin sections (60–65 nm) were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images were taken with a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai G2–12; FEI) equipped with a digital camera (BioSprint29, Advanced Microscopy Techniques).

In vitro co-culture

FACS-sorted WT, Cd80−/−, and MHCII- HFSCs were cultured on mitomycin C-treated feeders in Y medium with 650μM calcium. Naïve CD4 T cells were isolated from the spleen of WT C57/BL6J mice using MojoSort Mouse CD4 Naïve T cell Isolation Kit (Biolegend). The purified naïve CD4 T cells were activated with 5 μg/mL pre-coated anti-CD3 and 5 μg/mL soluble anti-CD28 antibody (Thermo Fisher) for 72 hours in the presence of 10 ng/mL IL2. GFPnegCD62LLowCD44Hi CD4 T cells or Treg cells were sorted from the lymph nodes of wounded Foxp3-GFP/DTR mice on day 2 post-wounding. 5 × 104 CD3/CD28 pre-activated T cells, GFPnegCD62LLowCD44Hi CD4 T cells or Treg cells were co-cultured with 5×104 HFSCs in T cell media supplemented with 10 ng/mL IL2 and 10 ng/mL TGFβ for 3 days or 5 days. To co-culture HFSCs with OTII T cells, HFSCs were cultured in Y media with 650μM calcium containing 15 μg/mL DQ-ovalbumin (Thermo Fisher, DQ-OVA) or 15 μg/mL ovalbumin peptide (InvivoGen, OVA323–339) at 37°C for 72 hours. FACS-sorted CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells were cultured in T cell media with DQ-OVA or OVA323–339 at 37°C for 24 hours as controls. 5×104 OVA-loaded HFSCs and 5×103 OVA-loaded dendritic cells were harvested by washing with PBS for three times, followed by co-culture with 5×104 Naïve CD4 T cells isolated from OTII mice in T cell media with 10 ng/mL IL2 and 10 ng/mL TGFβ for 5 days. Following the co-culture, Foxp3+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

RNA isolation and sequencing library preparation

Total RNAs from FACS-sorted epithelial cells were extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) followed by DNase I treatment and cleanup using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer protocol. RNA-seq libraries were prepared with the NEBNext Single Cell/Low input RNA library prep kit for Illumina (NEB) following the manufacturer protocol. For sequencing, the Illumina Novaseq platform was used.

ATAC-Seq library preparation

ATAC-Seq libraries were generated from FACS-sorted tdtomato+ HFSCs using a previously described protocol with minor modifications.38 Briefly, sorted cells were washed in 1xPBS, pelleted, and resuspended in an ice-cold lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 0.1% IGEPAL). Following centrifugation and removal of lysis buffer, samples were subjected to the transposase reaction for 30min at 37C using 10ul of transposase enzyme (Illumina Tagment DNA Enzyme and Buffer kits). Transposed DNA was cleaned up using a Qiagen MiniElute PCR Purification Kit and amplified using 10–15 cycles. Libraries were sequenced using Illumina Novaseq sequencing platform.

Next generation sequencing data analysis

RNA-Seq Alignment and Differential Expression Analysis

Raw sequenced reads were first trimmed and filtered by cutadapt (v3.2).39 Estimated transcript counts for the mouse genome assembly GRCm38 (mm10, GENCODE vM24) were obtained using the pseudo-aligner Kallisto (v0.44.0).40 Transcript-level abundance was summarized into gene level and differential gene expression was performed using the DESeq2 R package (v1.30.0) in R (v4.0.1).41 Genes with absolute log2 fold change > 2 and Benjamini-Hochberg method adjusted P values < 0.05 were regarded as significantly differentially expressed.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was performed by clusterProfiler package (https://guangchuangyu.github.io/software/clusterProfiler) to calculate the overlap between a gene list and pathways in MSigDB (Molecular signature database, v7.4) gene set collections (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp).42 Genes were ranked by the fold change value obtained from DESeq2. Pathways enriched with Benjamini-Hochberg method adjusted P values < 0.25 were considered to be significant.

ATAC-seq

Raw sequenced reads were first trimmed and filtered by cutadapt (v3.2). We then used Bowtie2 (v2.3.4.3) to map the clean reads to the mm10 reference genome and duplicates were removed using Picard (v2.18.7) (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). ATAC-seq signal tracks were generated using deepTools and presented by Gviz package.43–45 Peaks were called using MACS2 (v2.2.7.1).46 Peaks were then combined and merged in bedtools (v2.30.0).47 Read counts were summed for each genomic region by featureCounts (v1.5.3).48 DESeq2 was applied to identify the differentially accessible regions from ATAC-seq data.

Single cell RNA-seq

Gene–cell count matrices from different samples were downloaded from GSE142471.26 Replicates for unwounded and wounded samples were merged using Seurat (v.4.1.0).49 Cells with <200 detected genes or >5000 detected genes or > 7.5% mitochondrial genes were filtered-out from the dataset. Then data were column-normalized and log-transformed. All replicates were integrated using reciprocal PCA method. To identify cell clusters, principal component analysis (PCA) was first performed and the top 30 PCs with a resolution = 0.4 were applied. Non-immune cells were subset based on the expression of CD45 (Ptprc) and re-clustered using the same parameters.

Statistics

Statistical analysis for microscopy quantifications was performed in Prism 9 (GraphPad). Column data were first analyzed using D’Agostino and Pearson normality testing. The two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was performed for data not normally distributed with a 95% confidence interval. The unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test was performed for normally distributed data with a 95% confidence interval. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between groups were noted by asterisks (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001). The group size was determined by power analysis based on preliminary experimental results. Experiments were performed unblinded.

Data and Software Availability

Raw and analyzed data is available at NCBI and the accession number for the RNA sequencing and ATAC-seq data reported in this paper are NCBI GEO: GSE220241.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Migrating HFSCs activate CD80 during cutaneous wound repair

CD80 deficiency in HFSCs causes delayed wound healing

HFSCs acquire CD80 to expand extrathymic regulatory T cells

HFSC and Treg cell interactions prevent accumulation of neutrophils

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Woodside and J. Stanisavic in the Miao lab and M. Nikolova, E. Wong and J. Racelis in the Fuchs’ lab for technical assistance; R. Niec, S. Naik and S. Liu (Fuchs’ lab) for discussions; J. Levorse for performing lentiviral injections; S. Dikiy for help with Foxp3ΔCNS1-GFP and control mice. B. Ladd, Semova, S. Han and S. Tadesse (Flow Cytometry Core at the University of Chicago and Rockefeller University) for conducting FACS sorting; and P. Faber and C. Lai (Genomics Core at the University of Chicago or Rockefeller University) for sequencing and raw data processing, Animal Resources Center at UChicago and Comparative Bioscience Center at Rockefeller for mouse care. E.F. is a Howard Hughes Medical Investigator. This study was supported by Y.M.’s Start-up fund and seed grants from The University of Chicago, grants to Y. M. from NIH (R00CA237859, R01CA285786 and R35GM150610), V Foundation, American Association for Cancer Research, and The Cancer Research Foundation, as well as grants to E.F. from the NIH (R01-AR31737, R01-AR050452 and R37-AR27883), Star Foundation, New York State(C32585GG). C. T. was supported by HHMI Medical Scholar fellowship. N.I. was the recipient of a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases National Research Service Award (NRSA; F31AR073110). K.S. was a recipient of a Canadian Institute of Health Research Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes