Short abstract

Medically assisted death is legal in a few countries, and discussion about legalisation is ongoing in many others. But legalisation may be premature when we still do not know why patients want euthanasia and whether better end of life care would change their views

Countless debates have been held on euthanasia, but little research has been done into the experiences of patients who request it. Proponents portray an undignified death and opponents fear the potential dangers of legalising euthanasia, but the fundamental question is why patients want euthanasia. Current debates have been based on perspectives of medical professionals, academics, lawyers, politicians, and the public. Qualitative, experiential, and patient based research is needed to help capture the complexity of patients' subjective experiences and elucidate the influences and meanings that underpin their desire for death.

The euthanasia debate

Justifications for legalisation of euthanasia have pivoted on unbearable suffering, respect for autonomy, and dignified death. Proponents argue, from the principles of compassion and self determination, that mentally competent patients with an incurable illness and intolerable suffering should be able to choose the manner and timing of their death. This view is gaining support within an increasingly secular society with an individualistic and utilitarian ethos.

Opponents highlight the potential dangers for patients, healthcare professionals, and society.1 Doctors should strive to relieve suffering, not end the life of the sufferer; the authority to terminate life would undermine their trustworthiness. Euthanasia is irreversible, yet the will to live often fluctuates widely over the course of a terminal illness.2

Some opponents fear patients might feel obliged to request euthanasia to avoid being a burden, particularly as acts to end life already occur without the patients' explicit requests.3 Regulation of euthanasia cannot be securely enforced, which creates potential for abuse.4 Moral disintegration could occur when society views euthanasia as a cheaper and preferable option to providing care.5 Others believe that excellent palliative care obviates the need for euthanasia.6

Before ethical debates

A central controversy in euthanasia debates is the difficulty in defining and proving unbearable suffering. What are the dimensions of suffering experienced by patients who desire death? Are we paying adequate attention to diagnosing and relieving suffering, when the customary biomedical model of care has focused more on the disease than the patient? Are we comfortable and competent in communicating with people who are dying? Do we understand the genuine meaning of euthanasia requests? Is the topic of suffering emphasised in medical education and research? In effect, have we overlooked our patients' experience of suffering?

Figure 1.

Euthanasia with Death by John Spooner, 1997

Credit: JOHN SPOONER/THE AGE/CHRYSALIS/NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA

Research data on euthanasia

Most studies of euthanasia have been quantitative, focusing primarily on attitudes of healthcare professionals, relatives, and the public.7,8 The patients included in these studies were neither terminally ill nor currently desiring death7,9,10; their attitudes in response to hypothetical scenarios might not indicate what they actually will want or do in the future.11 Nevertheless, these studies are important. Pain was cited as a major reason for requesting euthanasia; other influences included functional impairment, dependency, burden, social isolation, depression, hopelessness, and issues of control and autonomy 7-10,12,13

A few recent qualitative studies have provided evidence about the perspectives of patients who desired death. Lavery and colleagues used a grounded theory approach to explore the origins of medically assisted death in HIV positive patients.14 Two factors emerged: firstly, disintegration from symptoms and functional loss and, secondly, loss of community, which they defined as diminishing opportunities to initiate and maintain close personal relationships, leading to a perceived loss of self. Johansen and colleagues interviewed patients in a palliative care unit about their future wishes for euthanasia. Their views were hypothetical, ambivalent, and fluctuating, influenced by fears of future pain or a painful death, lack of quality of life, and lack of hope.15

Two of us (YYWM and GE) conducted a hermeneutic study with unstructured interviews to explore the meaning of desire for euthanasia in six patients with advanced cancer who had expressed a wish for euthanasia while receiving palliative care.16 We found five main themes: the reality of disease progression, perception of suffering, anticipation of a future worse than death, desires for good quality end of life care, and presence of care and connectedness. Thus the meaning of desire for euthanasia was not confined to physical and functional concerns but revealed hidden psychosocial and existential issues, understood within the context of the patients' whole life experiences.

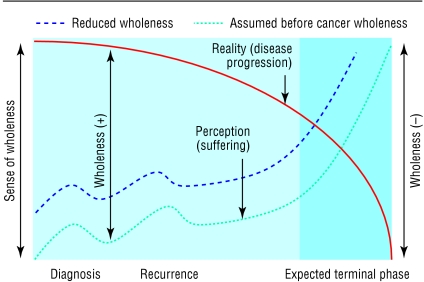

The combination of disease progression and increasing suffering perceived along the illness journey gave rise to a sense of progressive disintegration of self or wholeness (figure). This wholeness gradually diminished to the extent that patients could predict a negative future worse than death itself. Disintegration was likely to occur earlier if patients had unresolved life events, personality problems, or poor social support that threatened their sense of wholeness before they had cancer. The prospect of good quality end of life care and fulfilled needs helped alter their perceived reality and led to re-evaluation of their desire for death.

Figure 2.

Patients' perceived reality of their past, present, and future for those who felt whole before diagnosis and those with reduced sense of wholeness because of unresolved life events, personality problems, or poor social support

Summary points

Euthanasia debates have focused on suffering, respect for patent autonomy, and dignified death

Little evidence is available from patients who desire euthanasia

More qualitative, experiential, and patient based studies are needed to capture their voices

Patients' reasons for desiring euthanasia are not confined to the effects of disease, but relate to their whole life experiences

Good end of life care can influence patients' perception of hope and personal worth

These studies emphasise the importance of understanding the patients as a whole person in order to interpret the true meaning of requests for euthanasia. This includes their life experiences, perception and fears about their future, and yearnings for care and social connection to their community.

Reorientation of focus

Legalising euthanasia is premature when research evidence from the perspectives of those who desire euthanasia is scant. More qualitative patient based studies are needed to broaden our understanding of patients.17 Inclusion of medical humanities, experiential learning, and reflective practice into medical education should help ensure doctors have better communication skills and attitudes.18,19 We must examine ways to improve care at all levels before we can eliminate the side effects of poor end of life care. The government should consider allocating adequate resources to reduce the burden of care as well as promoting education on death, and palliative care services should develop imaginative outreach services.

Rather than focusing on assessing the mental competence of patients requesting euthanasia or determining clear legal guidelines, doctors must acquire the skills for providing good end of life care. These include the ability to “connect” with patients, diagnose suffering, and understand patients' hidden agendas through in-depth exploration. This is especially important as the tenor of care influences patients' perception of hope and personal worth. There is much to ponder over the meaning of a euthanasia request before we have to consider its justification. The desire for euthanasia must not be taken at face value.

We thank colleagues in the European Association of Palliative Care for discussions that informed this debate.

Contributors and sources: This is a summary of a dissertation written by YYWM as part of a MSc in palliative medicine at the University of Wales College of Medicine. GE and IGF helped draft the article

Competing interests: IGF is a member of the House of Lords and gave evidence on behalf of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland to the Select Committee in Medical Ethics in 1992.

References

- 1.Woodruff R. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide—are they clinically necessary? Houston, TX: International Hospice Institute and College, 1999.

- 2.Chochinov H, Tataryn D, Clinch J, Dudgean D. Will to live in the terminally ill. Lancet 1999;354: 816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pijnenborg L, van der Maas P, van Delden J, Johannes J, Looman C. Life-terminating acts without explicit request of patient. Lancet 1993;341: 1196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.House of Lords Select Committee. Report on medical ethics. London: Stationary Office, 2003. (HL67; 1992/3).

- 5.Roy D, Macdonald N. Ethical issues in palliative care. In: Doyle D, Hanks G, Macdonald N, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998: 120-33.

- 6.Foley K. Competent care for the dying instead of physician-assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 1997;336: 54-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emanuel E, Fairclough D, Daniels E, Clarridge B. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: attitudes and experiences of oncology patients, oncologists, and the public. Lancet 1996;347: 1805-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seale C, Addington-Hall J. Euthanasia: why people want to die earlier. Soc Sci Med 1994;39: 647-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Passik S. Interest in physician-assisted suicide among ambulatory HIV-infected patients. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153: 238-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan M, Rapp S, Fitzgibbon D, Chapman C. Pain and the choice to hasten death in patients with painful metastatic cancer. J Palliat Care 1997;13: 18-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishara B. Synthesis of research and evidence on factors affecting the desire of terminally ill or seriously chronically ill persons to hasten death. Omega 1999;39: ii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Back A, Wallace J, Starks H, Pearlman R. Physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia in Washington State. JAMA 1996;275: 919-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chochinov H. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152: 1185-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavery J, Boyle J, Dickens B, Maclean H, Singer P. Origins of the desire for euthanasia and assisted suicide in people with HIV-1 or AIDS: a qualitative study. Lancet 2001;358: 362-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen S, Holen J, Kaasa S, Loge J, Materstvedt L. Attitudes towards and wishes for euthanasia in advanced cancer patients at a palliative care unit. Palliat Med (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mak Y, Elwyn G. Use of hermeneutic research in understanding the meaning of desire for euthanasia. Palliat Med 2003;17: 395-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malterud K. The art of science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001;358: 397-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vass A. What's a good doctor, and how can we make one? BMJ 2002;325: 667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolton G. Reflective practice writing for professional development. London: Sage, 2001.