Abstract

In this work, we aim to discuss about the evolution of rotating black holes (RBHs) within the context of loop quantum cosmology. Here, the main part of our research work focuses on the impacts of angular momentum based rotating parameter and accretion efficiency on the lifetime of RBHs. Our study reveals that accretion of dark energy would not significantly affect the evolution of RBHs, however higher value of rotating parameter could slightly delay the evaporation times of RBHs. Our analysis also depicts that the maximum value of rotating parameter for evolution of any RBH is , where is the formation mass of RBH. Moreover, from our calculation we found that the maximum mass of a presently existing supermassive black hole would be , if it undergoes rotation. Also from astrophysical constraint analysis, we found that there is a greater tendency for formation of black holes in loop quantum cosmology than standard model of cosmology.

Keywords: Dark energy, Rotating black holes, Loop quantum cosmology

Subject terms: Cosmology, Dark energy and dark matter, General relativity and gravity

Introduction

Black Hole is a large compact fascinating object, where the existence of gravity in the region of space-time is so strong that nothing can escape out of it. The most general solution for black hole was first successfully given by Karl Schwarzschild in 19161,2. In this solution, Schwarzschild had focused on the space-time of black holes which were spherically symmetric and electrically neutral in nature, and could be explained only in terms of their masses. Later, Hans Reissner (1916) and Gunnar Nordstr (1918) had provided a solution for those black holes, which can be explained in terms of spherically symmetric property of black hole having some mass and finite amount of electric charge3–5. In general, most astronomical bodies are rotating in nature. During the process of rotating body collapse, the rate of rotation would increase by maintaining its constant angular momentum. In nature, the existence of rotating black hole6,7 played a prominent role in different astrophysical processes. Actually, the rotating black hole is an exceptional astronomical object which provides various features and properties that differs from a static black hole. In 1963, Roy Kerr (A famous New Zealand Mathematician) had discovered a solution for black holes whose space-times are rotating and electrically uncharged in nature8,9. On the basis of classical features, the resulting space-times can be explained by Kerr solution. For the rotating and charged black holes, Ezra Newman in 1965 provided a solution that explained the behavior of such class of black holes and commonly known as Kerr-Newman solution. According to the no-hair theorem10, black holes are completely explained by the three physical quantities i.e. mass (M), charge (q) and angular momentum (J). Basing on this no-hair theorem, the black holes having only two physical parameters, mass and angular momentum, are called Kerr black holes. From a geometrical point of view, when we deviate from the spherical symmetry, a new metric comes into picture known as Kerr metric, that can describe the black hole in terms of their angular momentum and mass. This metric was developed 48 years after the Einstein field equations came into existence8. The equation for Kerr metric8,11,12 is generally defined in terms of Boyer-Lindquist co-ordinates. The Kerr metric is only useful, when you take uncharged spinning black hole into consideration. A Kerr black hole is constituted of several structural terms such as spin axis, horizon, ergo sphere, static limit etc. The existence of angular momentum not only shows the space-time around Kerr black hole13 is non-static but also matter can move very close to the orbit of the respective black holes. The study of such kind of black holes which contain an asymptotic notion of angular momentum in the dark energy submerged environment can provide an interesting result.

On the other hand, the quantization of gravity14 is yet an unsettled issue and it requires a wide range of techniques to provide any kind of relevant solution. As we know, one of the greatest success of general relativity15–19 is its geometrical techniques and it will be more suitable when we combine with the quantum mechanical techniques20. General theory of relativity and quantum theory cannot individually explain all the questions relate with the origin of the universe. Quantum gravity is the theory whose main objective is to combine both these theory into a unified theory. Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG)21–25 is one of the characteristic features of quantum gravity theories which are completely non-perturbative and explicit background independent in nature26. The implication of LQG framework on cosmology to examine our whole universe is generally known as loop quantum cosmology (LQC)27–30. LQC is based on the theory which replaces the classical big bang singularity31 by quantum big bounce32. This remarkable theory can resolve the theory of singularity and explain various unknown character that our universe would possess, by analyzing the evolution of various astronomical bodies. Furthermore, our observable universe is mainly filled with dark energy, dark matter and ordinary matter in different proportion33,34 and recent observation shows that the present universe is largely dominated by dark energy35–37. By considering this dark energy domination16,38–41 in LQC, the study of the RBHs dynamics may provide a captivating result than in the case of standard cosmology42and other theories of gravity43,44.

In 1974, Hawking found that black holes emit thermal radiation as a result of quantum phenomena45. Generally the black hole evaporation depends upon its initial mass. This signifies that lesser is the initial mass, more quickly the black hole will evaporate. Again, the evolution of evaporating black holes was successfully examined by Page in his work by taking Schwarzschild and Kerr metric into consideration46,47. Especially, the evolution of rotating Kerr black hole was studied numerically by Page where he had considered Hawking evaporation process only47. But during the early evolution of black hole, the background environment was very hot and highly dense. So a very substantial amount of absorption of energy-matter, called accretion, from the surrounding goes into the black holes. In literature many works have been studied on the effect of accretion that is responsible for the enhancement of life time of black holes48. The effect of dark energy accretion on black holes has been studied by several researchers49,50. Similarly, the impact of radiation accretion on evolution of black holes was explained in the context of different theories like Brans-Dicke theory51, standard cosmology17 and brane world cosmology52.

In this work, we study the evolution of rotating black holes (RBHs) within the context of loop quantum cosmology (LQC) by taking interacting dark energy into account. Here, actually we have examined the impact of dark energy accretion on evolution of RBHs and investigated the impact of rotating parameter on RBHs dynamics. In this article, we have also tried to impose constraints on the formation of RBHs from present astrophysical observations.

Basic framework

For a spatially flat FRW universe () having scale factor a(t) and energy density (), the Friedmann equation, Raychaudhuri’s equation and energy conservation equation in loop quantum cosmology53–55 take the form

| 1 |

| 2 |

and

| 3 |

respectively. Here is the Hubble parameter, p is the pressure of the perfect fluid filling the universe and symbolizes the critical value of energy density of the universe given by with is the dimensionless Barbero-Immirzi parameter56–58 and is the energy density of the universe in Planck time. We can also construct braneworld cosmology independently from Eq. (1) like Loop Quantum Gravity. Basically when the general relativity reaches its high curvature limits, we expect that Freidmann dynamics have to change. This modification is naturally possible by taking quantum gravity into consideration. We want to explain that how braneworld cosmology59–61 can be formulated from the standard Freidmann equation and how can be it different from loop quantum gravity. Freidmann equation in standard cosmology gives . But the modified Friedmann equation in loop quantum cosmology is represented as . This change in the Friedmann equation represents the discrete quantum nature of space time as predicted by loop quantum cosmology. The way the Friedmann equation is modified corresponds to a bouncing cosmology without singularities. But for braneworld cosmology case, the modified Friedmann equation in the Randall-Sundrum braneworld scenario (most widely studied) can be expressed as , where is the brane tension and rests have their usual meaning. This variation in this effective Friedmann equation shows the existence of extra dimensions to this model. Also these theories are different from each other in different aspects, for example superinflation in the early universe and a nonsingular bounce in a contracting universe is the main features of LQC but it is absent in case of R-S braneworld scenario.

From the energy conservation equation, we can find the energy density of the universe for both radiation-dominated era and matter-dominated era as;

| 4 |

where is the radiation-matter equality.

By using the solution of Friedmann equation, one can get the scale factor a(t) for different cosmic eras. For the radiation-dominated era (), the scale factor varies as26

| 5 |

where subscript represents the present value of the corresponding parameter and .

Similarly, for the matter-dominated era (), the scale factor varies as

| 6 |

By using the Eqs. (4), (5) and (6), the expression for energy density in radiation-dominated era and matter-dominated era can be written as26

| 7 |

and

| 8 |

Therefore, redshift (z) can be calculated for radiation-dominated era and matter-dominated era as

| 9 |

where

| 10 |

and

| 11 |

respectively.

Assuming that the early universe is filled with radiation & matter and latter dark energy appeared due to their decay and using the present observational data36 that 68.3% of the universe is filled with dark energy and present age of the universe is years. one can find the decay rate as , i.e. we can write with and . Here is the radiation-matter density and is the dark energy density having pressure . Again, the equation of state parameter for an interacting dark energy in loop quantum cosmology was found to be62

| 12 |

But as per principle, the equation of state parameter of interacting dark energy should be always negative: This demands that interaction will continue upto .

The spacetime around a rotating black hole with mass M and angular momentum J can be explained by the line element as11,63

| 13 |

Where , , . The (t,r,,) co-ordinates used here are called Boyer-Lindquist co-ordinates and are analogous to the Schwarzschild coordinates for a non rotating black hole.

Rotating black holes and accretion of dark energy

Basically, Einstein-Maxwell theory deals with the black hole solutions whose charge and angular momentum are non zero commonly called as Kerr-Newman space time. Here we consider an uncharged rotating black hole i.e. Kerr black hole within the context of loop quantum cosmology. In this work, we study the effect of accretion of dark energy on the lifetime of the black holes17,64–66. The accretion rate of a black hole in the presence of interacting dark energy is given by16,67

| 14 |

Here, for radiation-dominated era and for matter-dominated era , f is the accretion efficiency, and is the radius of the outer horizon of the rotating black hole with the mass M. Mathematically can be represented by

| 15 |

where rotation parameter (with angular momentum J). In order to avoid naked singularity, the rotating black hole solution must obeys the inequality . Again, the exact value of f is not fixed as it depends upon the mean free paths of the surroundings particles of RBHs. Moreover, the accretion of dark energy will continue as long as the interaction becomes effective i.e. upto . Now by using the expression of Eqs. (7), (12) and (15) in Eq. (14), we find the modified accretion rate for radiation-dominated era as

| 16 |

Solving the above Eq. (16), we get

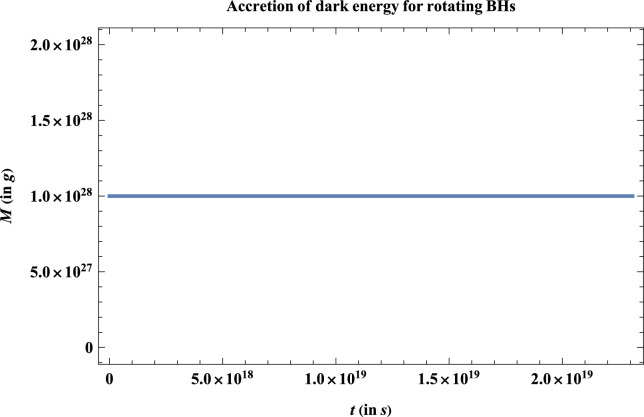

Above equation shows that when you vary the time in a certain range, the change in mass is quite negligible. So we cannot say that mass change is always giving a constant value throughout the whole evolution. We can only say that the mass variation is negligibly small, as we move in cosmic time, for different formation mass of the RBH in radiation-dominated era, which is depicted on Figure 1. Similarly, we can calculate the modified accretion rate for matter-dominated era by using Eqs. (8), (12) and (15) in Eq. (14) as

| 17 |

Solving the above Eq. (17), we get

The solution of Eqs. (16) and (17) can be obtained by integrating the equations w.r.t time; which further exactly match with the results of non-rotating case at the limit . In Figure 1, we plot the variation of mass of a particular RBH, which is formed at having rotating parameter for a single value of accretion efficiency . This graph shows that accretion of dark energy does not affect significantly the evolution of RBH in loop quantum cosmology. One of the reason behind this result is the absence of big bang in loop quantum cosmology. We know that energy formed during the big bang is the main cause for the rapid expansion of this universe. As the big bang is absent in LQC, the rate of expansion of this universe is slower than the standard cosmology and hence absorption of energy-matter from the surroundings become ineffective. The other factors like the symmetry of the black hole, the type of accretion rates and the type of the background fluids affect the accretion phenomena of Kerr black holes. Basically the existence of axial symmetry and stationarity of the Kerr black hole leads to slows down the accretion process68. In Kerr black hole, strong relativistic effects (mainly frame dragging effects) can influence the stability and dynamics of Kerr black hole environment which can reduce the steady accretion rate69. Several additional factors: angular momentum efficiency and radiative cooling process70 affect significantly to the accretion of Kerr black hole. Higher radiation efficiency in Kerr black hole move matter-energy away, as it spirals inward that reduces the mass which goes into the black hole and hence reduces the growth of the black hole.

Figure 1.

Variation of the RBH mass with time.

Evolution of rotating black holes

The interplay between accretion and evaporation of rotating black holes represents the whole evolution of RBHs. The rate of change of mass due to Hawking evaporation is given by42,48

| 18 |

where is the Stefan’s constant and is the Hawking temperature. The mathematical expression of for rotating uncharged black hole is42,45,71

| 19 |

Now by using the above expression, Eq. (18) modifies to

| 20 |

In order to understand the whole evolution of RBH, one should know the total rate of change of mass of RBHs by considering both accretion and evaporation. Now the complete evolution equation becomes

| 21 |

Since above Eq. (21) is not analytically solvable, we use numerical methods to solve it. Those RBHs are formed and evaporated in the radiation-dominated era, they all will follow this evolution Eq. (21). But for those RBHs which are lived in matter-dominated era, they are not affected by the accretion beyond time during their evolution. Because during that era due to absence of interaction between dust and dark energy, the environment is not suitable enough for energy and matter absorption. So, during that time black hole evolution is only influenced by the evaporation term in the evolution equation. But, all the black holes obey evolution Eq. (21) during the time period to in matter-dominated era.

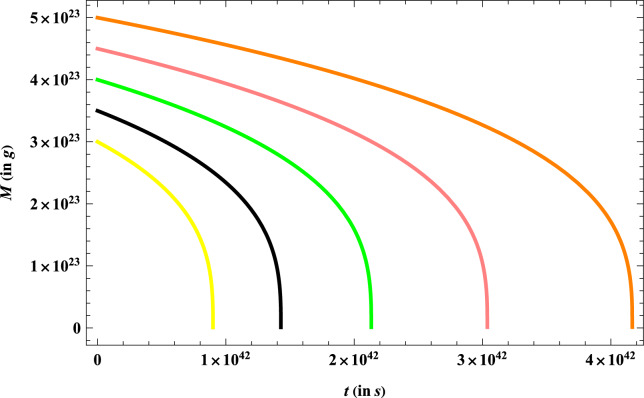

Now we construct Table 1 by using the accretion and evaporation equations, which shows the variation of evaporation time for different values of formation time and mass of RBHs.

Table 1.

Calculation of evaporation time () and maximum value of rotating parameter for different RBH mass and time at fixed accretion efficiency f.

| (in s) | (in g) | (in s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Table 1 shows that how evaporation time changes, when we consider different formation masses of RBHs. We can see that when we increase the formation mass of RBHs, the evaporation time increases. It shows that early forming RBHs evaporate more quickly than the latter one. This fact is also verified in Figure 2. From Table 1, we also found that the maximum limit of rotating parameter restrict to a certain value which is , where is the formation mass. Moreover, from Table 1, we concluded that the rotating black holes having initial mass greater than would be completely evaporated by present time. As we know the accretion efficiency f relies on some complex physical processes, however the precise value of f is not confirmed. But, here we found that f value becomes ineffective when RBH is investigated in the theory of LQC. Again we make Table 2 by using the accretion and evaporation equation, which shows the variation of evaporation time for different values of formation time and mass of RBHs at particular rotating parameter value.

Figure 2.

Variation of the RBH mass with evaporation time for a constant value of rotating parameter .

Table 2.

Calculation of evaporation time () for different value of RBH mass and time at fixed rotating parameter .

| (in s) | (in g) | (in s) | (in s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.9000 | 0.9000 |

| 0.35 | 0.35 | 1.4292 | 1.4292 |

| 0.40 | 0.40 | 2.1333 | 2.1333 |

| 0.45 | 0.45 | 3.0375 | 3.0375 |

| 0.50 | 0.50 | 4.1667 | 4.1667 |

One can see from Table 2 that the evaporation time is different for different initial mass for a particular rotating parameter value, and independent of accretion of dark energy. But the variation of rotating parameter slightly increases the life time of the RBHs in the theory of LQC. To optimize our results, we construct the Table 3 which shows the variation of the evaporation time with rotating parameter for RBH having formation mass . It explains that the evaporation time is slightly increases by increasing the value of rotating parameter . However the life span of RBHs significantly increases with increase in rotation parameter in standard cosmology42. The main reason behind this discrepancy is due to the absence of big bang within the theory of LQC. The presence of insufficient energy in LQC directly indicates that RBHs, which are formed in radiation dominated era, could not accumulate more energy by its rotation. This may be the cause why evaporation time of RBHs comes earlier in LQC than in case of standard cosmology. The other possible factors behind this discrepancy are the symmetry of the black hole, the type of accretion rates and the type of the background fluids.

Table 3.

Variation of the evaporation time with rotating parameter for fixed value of RBH mass and time.

| s, g | |

|---|---|

| s) | |

| 3333.32123 | |

| 3333.32123 | |

| 3333.32124 | |

| 3333.32125 | |

| 3333.32138 | |

| 3333.32273 | |

Here, we also shed some light on the evolution of supermassive rotating black holes in the framework of LQC. As we know supermassive rotating black holes (SMRBHs) are highly dense object and gigantic celestial structure existed at the center of galaxies. Recently large number of observations indicate the existence of early SMRBHs in different quasars. As per the recent data72, a luminous quasar named J0313-1806 having luminosity existed at a red shift of 2 just after the big bang happens. After a long spectroscopic survey, researchers identify the presence of huge SMRBH having mass () at a distance of 670 million years that provides many puzzles in different theoretical models. In our work, we examine successfully that SMRBHs having mass greater than equal to , would have all been evaporated by present time. So in near future, if astrophysicists will observe RBHs having mass more than equal to in any galaxy, then it will put challenges to theoretical cosmologists to encounter the mystery behind such type of gigantic supermassive black holes.

Astrophysical constraints on the RBH mass fraction

Black holes formation in different cosmological eras must be supported by the matter density of the universe in that respective eras. Several cosmological observations can be taken as a suitable candidate to enforce constraints on the number density of the RBHs in different cosmic time. These constraints behave as the responsible candidates for the RBHs formation mass spectrum in different models of cosmology. Various constraints such as present matter density of the universe, present photon spectrum, Distortion of the cosmic microwave background spectrum, Nucleosynthesis constraints and Deuterium photodisintegration constraint73 were studied in standard cosmology. Also one can study important constraints from various limits of -ray background74,75and observed galactic antiprotons and antideuterons76,77. In our work, we calculate the initial mass spectrum of RBHs by taking -ray background limit into consideration within the theory of loop quantum cosmology.

The mass fraction of the universe is going into RBHs at any time t is represented by26,78,79

| 22 |

where shows the present density parameter interconnected with RBHs forming at time t having value , z is the redshift linked with time t and represent the present microwave background density with value . Here we consider that RBHs are formed in the radiation-dominated era. So in this environment, the redshift equation becomes

| 23 |

By inserting the scale factor expression in above Eq. (23) in terms of , we can get the modified redshift equation as

| 24 |

where . By using Eq. (24) in Eq. (22) and taking the values of and , one can find the bound on the mass fraction for presently evaporating RBHs as

| 25 |

Here our result is much greater than the values found in case of standard cosmology and scalar-tensor theory42,80, which implies there is a greater tendency for formation of black holes in loop quantum cosmology than any other cosmological models.

Conclusion

In this work, we have successfully explained the evolution of rotating black holes (RBHs) by introducing the concept of interacting dark energy within the context of loop quantum cosmology. First, we have evaluated the accretion rate of RBHs by using the expressions of energy density (), equation of state parameter () and radius of RBHs. Subsequently, we have calculated the evaporation rate of RBHs by applying the Hawking evaporation mechanism. From our analysis, we found that the effect of accretion of dark energy would be insignificant in influencing the evolution of RBHs. Again, we have analyzed the impact of rotation on evolution of black holes. This study made us to put a constraint on the maximum value of rotating parameter. The allowed values of this parameter was found to be within the range of 0 and , where is the formation mass of RBH. Further, we have found that the life span of a black hole having rotation would be slightly greater than that of its non-rotating counterpart. By taking accretion of dark energy and Hawking evaporation into account, we have shown the complete evolution of RBHs in different cosmic eras. Finally, our study predicted that the supermassive RBHs having mass greater than equal to , would have been all evaporated by present time. Also from astrophysical constraint analysis, we concluded that there is a greater tendency for formation of black holes in loop quantum cosmology than standard cosmology and scalar-tensor theory.

Ethics declaration

The research and analysis conducted by the authors are fully and accurately reflected in the paper. Nowhere is this work being considered for publication.

Acknowledgements

One of the authors S. Swain is thankful to Department of Physics, Fakir Mohan University, Balasore, Odisha for providing good research environment and computational facility.

Author contributions

S. S. and B. N. wrote the main manuscript text and performed all the analysis. G. S. contributed to the idea, figures, tables and results. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Suryakanta Swain, Gourishankar Sahoo, Bibekananda Nayak

References

- 1.Schwarzschild, K. On the gravitational field of a mass point according to Einstein’s theory. Sitz. Preuss. Akad. Wiss.1916, 189–196 (1916). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarzschild, K. On the gravitational field of a sphere of incompressible fluid according to Einstein’s theory. Sitz. Preuss. Akad. Wiss.1916, 424–434 (1916). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooperstock, F. I. & de la Cruz, V. Sources for the reissner-nordström metric. Gen. Relativ. Gravit.9, 835–843 (1978). 10.1007/BF00760872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukhari, S. M. A. S., Pourhassan, B., Aounallah, H. & Wang, L. G. On the microstructure of higher-dimensional reissner-nordström black holes in quantum regime. Class. Quant. Grav.40, 225007 (2023). 10.1088/1361-6382/acffa0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blagojević, M. & Cvetković, B. Entropy of reissner-nordström-like black holes. Phys. Lett. B824, 136815 (2022). 10.1016/j.physletb.2021.136815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babichev, E., Charmousis, C. & Lecoeur, N. Rotating black holes embedded in a cosmological background for scalar-tensor theories. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys.08, 022 (2023). 10.1088/1475-7516/2023/08/022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandes, P. G. S. Rotating black holes in semiclassical gravity. Phys. Rev. D108, L061502 (2023). 10.1103/PhysRevD.108.L061502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr, R. P. Gravitational field of a spinning mass as an example of algebraically special metrics. Phys. Rev. Lett.11, 237 (1963). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.11.237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bambi, C. Astrophysical black holes: A review. Multifrequency Behav. High Energy Cosmic Sour.- XIII362, 028 (2020). 10.22323/1.362.0028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu, R. R. The no hair theorem?. Chin. J. Phys.30, 569–577 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teukolsky, S. A. The kerr metric. Class. Quant. Grav.32, 124006 (2015). 10.1088/0264-9381/32/12/124006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman, E. T. & Janis, A. I. Note on the kerr spinning-particle metric. J. Math. Phys.6, 915–917 (1965). 10.1063/1.1704350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momennia, M., Herrera-Aguilar, A. & Nucamendi, U. Kerr black hole in de sitter spacetime and observational redshift: Toward a new method to measure the hubble constant. Phys. Rev. D107, 104041 (2023). 10.1103/PhysRevD.107.104041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domagała, M., Giesel, K., Kamiński, W. & Lewandowski, J. Gravity quantized: Loop quantum gravity with a scalar field. Phys. Rev. D82, 104038 (2010). 10.1103/PhysRevD.82.104038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll, S. M. Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity (Cambridge University Press, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayak, B. & Singh, L. P. Phantom energy accretion and primordial black holes evolution in brans-dicke theory. Eur. Phys. J. C71, 1837 (2011). 10.1140/epjc/s10052-011-1837-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nayak, B. & Singh, L. P. Accretion, primordial black holes and standard cosmology. Pramana - J. Phys.76, 173–181 (2011). 10.1007/s12043-011-0002-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui, Y. et al. Precessing jet nozzle connecting to a spinning black hole in m87. Nature621, 711–715 (2023). 10.1038/s41586-023-06479-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishnendu, N. V. & Ohme, F. Testing general relativity with gravitational waves: An overview. Universe7, 497 (2021). 10.3390/universe7120497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caravelli, F. & Modesto, L. Spinning loop black holes. Class. Quant. Grav.27, 245022 (2010). 10.1088/0264-9381/27/24/245022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashtekar, A. & Lewandowski, J. Background independent quantum gravity: a status report. Class. Quant. Grav.21, R53 (2004). 10.1088/0264-9381/21/15/R01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiemann, T. Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity (Cambridge University Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity (Cambridge University Press, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiou, D. W. Loop quantum gravity. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D24, 1530005 (2015). 10.1142/S0218271815300050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bojowald, M. & Brahma, S. Loop quantum gravity, signature change, and the no-boundary proposal. Phys. Rev. D102, 106023 (2020). 10.1103/PhysRevD.102.106023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dwivedee, D., Nayak, B., Jamil, M., Singh, L. P. & Myrzakulov, R. Evolution of primordial black holes in loop quantum cosmology. J. Astrophys. Astron.35, 97–106 (2014). 10.1007/s12036-014-9276-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bojowald, M. Loop quantum cosmology. Living Rev. Relativ.11, 4 (2008). 10.12942/lrr-2008-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashtekar, A., Pawlowski, T. & Singh, P. Quantum nature of the big bang: Improved dynamics. Phys. Rev. D74, 084003 (2006). 10.1103/PhysRevD.74.084003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashtekar, A. & Singh, P. Loop quantum cosmology: A status report. Class. Quant. Grav.28, 213001 (2011). 10.1088/0264-9381/28/21/213001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao, K. & Zhu, J. Y. Dynamical behavior of interacting dark energy in loop quantum cosmology. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A25, 4993–5007 (2010). 10.1142/S0217751X10050585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thébault, K. P. Y. Big bang singularity resolution in quantum cosmology. Class. Quant. Grav.40, 055007 (2023). 10.1088/1361-6382/acb752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashtekar, A. The big bang and the quantum. In AIP Conf. Proc.1241, 109–121 (2010). 10.1063/1.3462605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazumdar, A., Mohanty, S. & Parashari, P. Evidence of dark energy in different cosmological observations. Eur. Phys. J. ST230, 2055–2066 (2021). 10.1140/epjs/s11734-021-00212-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farnes, J. S. A unifying theory of dark energy and dark matter: Negative masses and matter creation within a modified lambda-cdm framework. Astron. Astrophys.620, 20 (2018). 10.1051/0004-6361/201832898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ade, P. A. R. et al. Planck 2013 results. xvi. cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys.571, 66 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ade, P. A. R. et al. Planck 2015 results. xiii. cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys.594, 63 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ade, P. A. R. et al. Planck 2015 results xiv. dark energy and modified gravity. Astron. Astrophys.594, 31 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dwivedee, D., Nayak, B. & Singh, L. P. Vacuum energy and primordial black holes in brans-dicke theory. Int. J. Theor. Phys.54, 2321–2333 (2015). 10.1007/s10773-014-2454-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odinstov, S. D., Oikonomou, V. K. & Tretyakov, P. V. Phase space analysis of the accelerating multifluid universe. Phys. Rev. D96, 044022 (2017). 10.1103/PhysRevD.96.044022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odinstov, S. D., Oikonomou, V. K. & Tretyakov, P. V. Dynamical systems perspective of cosmological finite-time singularities in f(r) gravity and interacting multifluid cosmology. Phys. Rev. D98, 024013 (2018). 10.1103/PhysRevD.98.024013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahu, D. & Nayak, B. Interacting quintessence model and accelerated expansion of the universe. In Workshop on Frontiers in High Energy Physics 2019: FHEP 2019, vol. 248, 93–97 (2020).

- 42.Mohapatra, S. & Nayak, B. Accretion of radiation and rotating primordial black holes. J. Exp. Theor. Phys.122, 243–247 (2016). 10.1134/S1063776116020096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nashed, G. G. L. & Nojiri, S. Rotating black hole in f(r) theory. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys.11, 007 (2021). 10.1088/1475-7516/2021/11/007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walia, R. K., Maharaj, S. D. & Ghosh, S. G. Rotating black holes in horndeski gravity: Thermodynamic and gravitational lensing. Eur. Phys. J. C82, 547 (2022). 10.1140/epjc/s10052-022-10451-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Commun. Math. Phys.43, 199–220 (1975). 10.1007/BF02345020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Page, D. N. Particle emission rates from a black hole: Massless particles from an uncharged, nonrotating hole. Phys. Rev. D13, 198 (1976). 10.1103/PhysRevD.13.198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Page, D. N. Particle emission rates from a black hole. ii. massless particles from a rotating hole. Phys. Rev. D14, 3260 (1976). 10.1103/PhysRevD.14.3260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Majumdar, A. S., Gangopadhyay, D. & Singh, L. P. Evolution of primordial black holes in jordan-brans-dicke cosmology. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.385, 1467–1470 (2008). 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.12925.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pugliese, D. & Stuchlík, Z. On dark energy effects on the accretion physics around a kiselev spinning black hole. Eur. Phys. J. C84, 486 (2024). 10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-12705-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babichev, E. O., Dokuchaev, V. I. & Eroshenko, Y. N. The accretion of dark energy onto a black hole. Exp. Theor. Phys.100, 528–538 (2005). 10.1134/1.1901765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guedens, R., Clancy, D. & Liddle, A. R. Primordial black holes in braneworld cosmologies: Accretion after formation. Phys. Rev. D66, 083509 (2002). 10.1103/PhysRevD.66.083509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Majumdar, A. S. Domination of black hole accretion in brane cosmology. Phys. Rev. Lett.90, 031303 (2003). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.031303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen, S., Wang, B. & Jing, J. Dynamics of an interacting dark energy model in Einstein and loop quantum cosmology. Phys. Rev. D78, 123503 (2008). 10.1103/PhysRevD.78.123503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jamil, M., Momeni, D. & Rashid, A. M. Notes on dark energy interacting with dark matter and unparticle in loop quantum cosmology. Eur. Phys. J. C71, 1711 (2011). 10.1140/epjc/s10052-011-1711-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dwivedee, D., Nayak, B. & Singh, L. P. Evolution of primordial black hole mass spectrum in brans-dicke theory. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D22, 1350022 (2013). 10.1142/S0218271813500223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashtekar, A., Baez, J., Corichi, A. & Krasnov, K. Quantum geometry and black hole entropy. Phys. Rev. Lett.80, 904 (1998). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Domagala, M. & Lewandowski, J. Black-hole entropy from quantum geometry. Class. Quant. Grav.21, 5233 (2004). 10.1088/0264-9381/21/22/014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meissner, A. K. Black-hole entropy in loop quantum gravity. Class. Quant. Grav.21, 5245 (2004). 10.1088/0264-9381/21/22/015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maartens, R. Cosmological dynamics on the brane. Phys. Rev. D62, 084023 (2000). 10.1103/PhysRevD.62.084023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maartens, R. & Koyama, K. Brane-world cosmology. Living Rev. Relativ.13, 5 (2010). 10.12942/lrr-2010-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh, P. Loop cosmological dynamics and dualities with randall-sundrum braneworlds. Phys. Rev. D73, 063508 (2006). 10.1103/PhysRevD.73.063508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swain, S., Sahu, D., Dwivedee, D., Sahoo, G. & Nayak, B. Generalized interacting dark energy model and loop quantum cosmology. Astrophys. Space Sci.367, 57 (2022). 10.1007/s10509-022-04084-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foster, J. & Nightingale, J. D. A Short Course in General Relativity. (SP SPRINGER, 2006).

- 64.Nayak, B. & Singh, L. P. Note on nonstationarity and accretion by primordial black holes in brans-dicke theory. Phys. Rev. D82, 127301 (2010). 10.1103/PhysRevD.82.127301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pati, S. K., Nayak, B. & Singh, L. P. Black hole dynamics in power-law based metric f(r) gravity. Gen. Relativ. Gravit.52, 78 (2020). 10.1007/s10714-020-02727-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nayak, B. & Jamil, M. Effect of vacuum energy on evolution of primordial black holes in Einstein gravity. Phys. Lett. B709, 118–122 (2012). 10.1016/j.physletb.2012.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Babichev, E., Dokuchaev, V. & Eroshenko, Y. Black hole mass decreasing due to phantom energy accretion. Phys. Rev. Lett.92, 021102 (2004). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.021102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hughston, L. P. & Sommers, P. The symmetries of kerr black holes. Commun. Math. Phys.33, 129–133 (1973). 10.1007/BF01645624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang, Y. & Li, X.-D. Strong field effects on emission line profiles: Kerr black holes and warped accretion disks. ApJ744, 186 (2012). 10.1088/0004-637X/744/2/186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dihingia, I. K., Mizuno, Y., Fromm, C. M. & Younsi, Z. Impact of radiative cooling on the magnetised geometrically thin accretion disk around kerr black hole. arXiv:2305.09696 (2023).

- 71.Frolov, V. P. & Zelnikov, A. Introduction to black hole physics (Oxford University Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang, F. et al. A luminous quasar at redshift 7.642. Astrophys. J. Lett.907, 7 (2021). 10.3847/2041-8213/abd8c6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nayak, B., Majumdar, A. S. & Singh, L. P. Astrophysical constraints on primordial black holes in brans-dicke theory. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys.08, 039 (2010). 10.1088/1475-7516/2010/08/039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacGibbon, J. H. & Carr, B. J. Cosmic rays from primordial black holes. Astrophys. J.371, 447–469 (1991). 10.1086/169909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sendouda, Y., Nagataki, S. & Sato, K. Constraints on the mass spectrum of primordial black holes and braneworld parameters from the high-energy diffuse photon background. Phys. Rev. D68, 103510 (2003). 10.1103/PhysRevD.68.103510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Donato, F. et al. Antiprotons from spallations of cosmic rays on interstellar matter. Astrophys. J.563, 172 (2001). 10.1086/323684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barrau, A. et al. Antiprotons from primordial black holes. Astron. Astrophys.388, 676–687 (2002). 10.1051/0004-6361:20020313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carr, B. J. The primordial black hole mass spectrum. Astrophys. J.201, 1–19 (1975). 10.1086/153853 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barrow, J. D. & Carr, B. J. Formation and evaporation of primordial black holes in scalar-tensor gravity theories. Phys. Rev. D54, 3920 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevD.54.3920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nayak, B., Singh, L. P. & Majumdar, A. S. Effect of accretion on primordial black holes in brans-dicke theory. Phys. Rev. D80, 023529 (2009). 10.1103/PhysRevD.80.023529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.