Abstract

Mounting evidence showed that HER2-Low breast cancer patients could benefit from the novel anti-HER2 antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) treatment, which pointed the way towards better therapy for HER2-Low patients. The purpose of this study was to describe the clinicopathological features, along with chemotherapeutic effects and survival outcomes of HER2-Low and HER2-Zero in TNBC who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT). We retrospectively evaluated 638 triple-negative breast cancer patients who were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy between August 2014 and August 2022. Pathologic complete response (pCR) and survival outcomes were analyzed in HER2-Low cohort, HER2-Zero cohort and the overall patients, respectively. In the entire cohort, 342 (53.6%) patients were HER2-Low and 296 (46.4%) patients were HER2-Zero. No significant difference was found between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients based on all the clinical–pathological characteristics. 143 cases (22.4%) achieved pCR after NACT in the overall TNBC patients. The pCR rate of the HER2-Low patients and the HER2-Zero patients was 21.3% and 23.6%, respectively, exhibiting no statistical difference (p = 0.487). The survival of pCR group after NACT significantly improved compared to non-pCR group either in HER2-Low patients or in HER2-Zero patients. Although we found that patients with HER2-Low had longer DFS than patients with HER2-Zero, there was no considerable difference (p = 0.068). However, HER2-Low patients had a dramatically longer OS than HER2-Zero patients (p = 0.012). The data from present study confirmed the clinical importance of HER2-Low expression in TNBC. Further effort is needed to determine whether HER2-Low could be a more favorable prognostic marker for individual treatment.

Keywords: Triple-negative breast cancer, HER2-Low, Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Pathologic complete response, Disease free survival, Overall survival

Subject terms: Cancer, Oncology

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a heterogeneous disease, it remains as the most frequently diagnosed carcinoma and as the second leading cause of women cancer-related death worldwide1. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is usually defined by the lack of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR), and is associated with the absence of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) overexpression and amplification, represents approximately 15%-20% of all BCs cases2. Although TNBC accounts for a relative smaller proportion of cases, it represents an aggressive subtype with an earlier onset, a distinct clinical course and a poorer survival than the other subtypes3. According to epidemiological studies, TNBC is most prevalent in premenopausal young women that are under the age of 404,5, patients ≤ 40 years have worse prognosis in spite of more aggressive systemic therapy6. For operable TNBC, the five-year recurrence rate is about 30–40%7, however, the median overall survival is usually less than 2 years in metastatic TNBC even with comprehensive systemic therapy8,9.

In addition to the aggressive biological characteristics, lack of effective therapeutic targets is also the cause of TNBC high recurrence rate and the poor prognosis, which make it a challenging issue in the clinical management of TNBC. Cytotoxic chemotherapy continues to be the backbone of mainstay of TNBC treatment, and TNBC is particularly sensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Currently, the frontline standard chemotherapy, consisted of anthracycline, taxane, and platinum regimens is commonly used to treat high-risk early and locally advanced TNBC10. Meanwhile, an improved understanding of the biology of TNBC and appreciation of the potential of personalized therapy strategies have already led to the development of novel targeted agents, including PARP inhibitors, anti-angiogenic inhibitors, immune-checkpoint inhibitors and antibody–drug conjugates, which are revolutionizing the therapeutic area and providing new opportunities both for TNBC treatment11. These inhibitors have been used as single agents or in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens to target specific molecular signaling pathways and key gene mutations that drive malignant progression of tumors.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is often the preferred safe and effective treatment choice for breast cancer patients with larger primary or locally advanced stages, based on the prognostic value of the treatment response and the possibility to treat with novel promising adjuvant therapies. The advantages of the neoadjuvant approach are to downstaging the tumors, potentially reduce the extent of surgery, improve breast-conserving rates and test the efficacy of therapy administered to patients12. Pathologic complete response (pCR) is defined as the absence of residual invasive disease in the breast and in the axillary lymph nodes following NACT13. In the neoadjuvant setting, pCR is associated with better disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), besides a lower risk of recurrence and death. Although TNBC tumors have a more aggressive character, they are more chemosensitive than other tumor subtypes, therefore, also have higher pCR rates14. Further studies confirmed that pCR in TNBC was associated with excellent prognosis, and as a suitable surrogate end point for patients15,16.

According to the HER2 testing guidelines, tumors with an immunohistochemistry(IHC) assay score 3+ or 2+ harboring HER2 amplification by in situ hybridization (ISH) assay are defined as HER2-positive17. Recently, a new classification, characterized by a low level of HER2 expression (IHC score 1 + or 2 + without ISH amplification) is defined as “HER2-Low” category18. Emerging evidence is showing that HER2-Low breast cancer patients could benefit from the anti-HER2 antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) treatment19. This revealed that HER2-Low tumors might represent a separate subset of luminal BCs and TNBCs, with distinct clinical features and thus the potential for new targeted therapies.

The purpose of present study is to utilize the real-world data and evidence derived from our hospital to describe the clinicopathological features, along with chemosensitivity and survival outcomes of HER2-Low and HER2-Zero in TNBC who received NACT followed by curative surgery.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and study design

From August 2014 to August 2022, patients with HER2-negative breast cancer who have received NAC from our hospital were retrospectively enrolled in this study. Clinicopathological data included the age, BMI, menstrual status, clinical stage, pathological type, histological grade, HER2 status, Ki-67 index, operation method, neoadjuvant therapy regimen and treatment efficacy, etc. Patients who selected had to meet the following inclusion criteria: invasive breast cancer confirmed by biopsy pathology; both ER and PR negative; HER2-negative; clinical stage I–III; neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery and with complete clinical data. The exclusion criteria as following: inflammatory breast cancer, bilateral breast cancer; occult breast cancer, lactation breast cancer, concomitant with other malignant tumors, without operation, ER positive BCs, PR positive BCs, HER-2 positive BCs and cases with incomplete follow-up data.

Treatment protocols

NACT regimens received in this study were based on anthracycline (doxorubicin, epirubicin or pirarubicin) and taxane (paclitaxe or docetaxel). The use of platinum was on the discretion of the treating physician. 2–6 cycles concomitant (anthracycline plus taxane with or without cyclophosphamide) regimen or eight cycles sequential (anthracycline plus cyclophosphamide followed by taxane) regimen was used. Of 603 patients (HER-2 Low group: 321 cases, HER-2 Zero group: 282 cases) who underwent anthracycline and taxane based regimen, 538 patients (HER-2 Low group: 285 cases, HER-2 Zero group: 253 cases) received 2–6 cycles concomitant regimen and 65 patients (HER-2 Low group: 36 cases, HER-2 Zero group: 29 cases) received 8 cycles sequential regimen. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 was used for the evaluation of the clinical response. Patients received operation after scheduled neoadjuvant therapy. The surgical options were determined based on the actual condition, operative indication and wishes of patients, including breast-conserving surgery and modified radical mastectomy.

Clinicopathological characteristics and efficacy assessments

Clinical stage was defined according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Commission Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system. IHC for HER2 was performed with the BenchMark XT Automated IHC/ISH slide staining system (VENTANA) using an anti HER2/neu antibody (clone number 4B5, VENTANA). PathVysion HER2 DNA probe kit (Abbott Diagnostics) was used for ISH test according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. HER2-negative breast cancer was divided into HER2-Low group and HER2-Zero group. HER2-Low was defined as HER2 IHC 1+ or HER2 IHC 2+ /ISH-negative and HER2-Zero was defined as IHC 0. 1% was set as the cutoff index between “negative” and “positive” for both ER and PR. Only both ER < 1%(negative) and PR < 1% (negative) patients were enrolled in this study. Ki67 was defined as low when the percentage of stained cells was ≤ 14% and high when > 14%20. Assessment criteria for pCR after NACT included ypTis/0ypN0 (defined as absence of invasive cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ in the breast and axillary lymph nodes).

Follow-up

Enrolled TNBC patients who completed NACT and operations from August 2014 to August 2022 were followed up mainly by telephone inquiry. The follow-up deadline was February, 2023. The adapted survival indicators were DFS and OS. DFS was defined as the interval between the date of diagnosis and the date of locoregional relapse, distant relapse or last follow-up. OS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis and the time of death by any causes.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 27 (Released 2020; IBM Corp., Armonk, USA, https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software) was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square test was used to analyze the relationship of clinicopathological factors between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero groups. Univariate and multivariable analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive factors for pCR according to log-rank test. Survival curves of patients were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test. The prognostic factors in the overall cohort, HER2-Low patients, and HER2-Zero patients were analyzed by cox proportional hazard model. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study design and the protocols for collection and analysis of the samples were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, in accordance with the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, Medical Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics analysis between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients

A total of 638 TNBC patients were analyzed in the present study. Baseline demographics and clinical–pathological characteristics stratified by HER2 status were summarized in Table1. In the entire cohort, 342 (53.6%) patients were HER2-Low and 296 (46.4%) patients were HER2-Zero. The majority of enrolled patients had a body mass index (BMI) < 30 and were premenopausal, irrespective of HER2 status. Meanwhile, more than half of patients were locally advanced breast cancer with T2–4, N1–3 and clinical stage III. Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) was the most dominant pathological type, more than one-third of patients with histological grade III, and most patients with Ki-67 index > 14%. More than 90% of patients received the standard anthracycline and taxane containing regimen, while a small number of patients received platinum treatment. The surgical method of the vast majority of patients was modified radical mastectomy, which was probably related to the majority of patients with locally advanced breast cancer. However, no significant difference was found between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients based on all the clinical–pathological characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinicopathologic characteristics analysis stratified by HER2 status.

| Characteristic | HER2-Low (N = 342) | HER2-Zero (N = 296) | Overall (N = 638) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(%) | 0.763 | |||

| < 50 | 167 (48.8) | 141 (47.6) | 308 (48.3) | |

| ≥ 50 | 175 (51.2) | 155 (52.4) | 330 (51.7) | |

| BMI (%) | 0.448 | |||

| < 30 | 263 (76.9) | 235 (79.4) | 498 (78.1) | |

| ≥ 30 | 79 (23.1) | 61 (20.6) | 140 (21.9) | |

| Menstrual status (%) | 0.230 | |||

| Premenopausal | 193 (56.4) | 153 (51.7) | 346 (54.2) | |

| Postmenopausal | 149 (43.6) | 143 (48.3) | 292 (45.8) | |

| cT (%) | 06.761 | |||

| cT1 | 32 (9.3) | 21 (7.1) | 53 (8.3) | |

| cT2 | 157 (45.9) | 136 (45.9) | 293 (45.9) | |

| cT3 | 122 (35.7) | 110 (37.2) | 232 (36.3) | |

| cT4 | 31 (9.1) | 29 (9.8) | 60 (9.4) | |

| cN | 0.876 | |||

| cN0 | 90 (26.3) | 76 (25.7) | 166 (26.0) | |

| cN1 | 144 (42.1) | 124 (41.9) | 268 (42.0) | |

| cN2 | 86 (25.2) | 72 (24.3) | 158 (24.8) | |

| cN3 | 22 (6.4) | 24 (8.1) | 46 (7.2) | |

| Clinical stage (%) | 0.301 | |||

| I | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | |

| II | 154 (45.0) | 129 (43.6) | 283 (44.4) | |

| III | 188 (55.0) | 165 (55.7) | 353 (55.3) | |

| Histological type (%) | 0.777 | |||

| IDC | 295 (86.3) | 253 (85.5) | 548 (85.9) | |

| Others | 47 (13.7) | 43 (14.5) | 90 (14.1) | |

| Histological grade (%) | 0.682 | |||

| I | 8 (2.3) | 5 (1.7) | 13 (2.0) | |

| II | 205 (59.9) | 186 (62.8) | 391(61.3) | |

| III | 129 (37.7) | 105 (35.5) | 234 (36.7) | |

| Ki67 (%) | 0.337 | |||

| ≤ 14% | 41 (12.0) | 29 (9.8) | 70 (11.0) | |

| > 14% | 301 (88.0) | 267 (90.2) | 568 (89.0) | |

| Chemotherapy regimen (%) | 0.586 | |||

| Anthracycline + Taxane | 321 (93.9) | 282 (95.3) | 603 (94.5) | |

| Platinum | 16 (4.7) | 12 (4.1) | 28 (4.4) | |

| Others | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.6) | 7 (1.1) | |

| Surgery (%) | 0.183 | |||

| Mastectomy | 313 (91.5) | 279 (94.3) | 592 (92.8) | |

| Breast-conserving | 29 (8.5) | 17 (5.7) | 46 (7.2) | |

BMI body mass index, IDC invasive ductal carcinoma.

Efficacy of NACT between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients

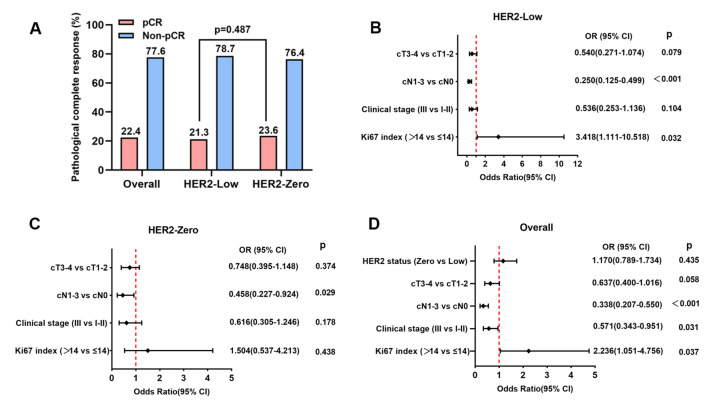

Of all the 638 patients eligible to the study, 143 cases (22.4%) achieved pCR after NACT. The pCR rate of the HER2-Low group and the HER2-Zero group was 21.3% and 23.6%, respectively, showing no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.487, Fig. 1A). A logistic analysis of predictive factors for pCR was carried out to evaluate the predictive value of demographics and clinicopathologic factors for pCR, including age, BMI, menstrual status, clinical tumor size, clinical lymph node involvement, clinical stage, histological type, histological grade, Ki-67, and HER2 status in HER2-Low group, HER2-Zero group and the overall patients (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

PCR rate in overall patients, HER2-Low group and HER2-Zero group (A). Forest plots for multivariable logistic regression analysis of pCR rates for HER2-low group (B), HER2-Zero group (C) and the overall patients (D).

Univariate analysis indicated that clinical tumor size (cT3–4 vs. cT1–2, p = 0.011, OR = 0.492, 95% CI 0.284 to 0.851), clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, p < 0.001, OR = 0.204, 95% CI 0.117 to 0.354) and clinical stage (III vs. I–II, p < 0.001, OR = 0.227, 95% CI 0.128 to 0.401) were predictive factors for pCR in HER2-Low patients. In HER-2 Zero patients, only clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, p < 0.001, OR = 0.371, 95% CI 0.209 to 0.659) and clinical stage (III vs. I–II, p = 0.001, OR = 0.400, 95% CI 0.231 to 0.694) were found to be predictive factors. However, in the overall patients, besides clinical tumor size (cT3–4 vs. cT1–2, p = 0.006, OR = 0.584, 95% CI 0.398 to 0.859), clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, p < 0.001, OR = 0.272, 95% CI 0.183 to 0.404) and clinical stage (III vs. I–II, p < 0.001, OR = 0.302, 95% CI 0.204 to 0.448), Ki67 index (> 14 vs. ≤ 14, p = 0.046, OR = 2.093, 95% CI 1.012 to 4.326) was also a predictive factor for pCR, the HER2 status (Zero vs. Low, p = 0.435, OR = 1.170, 95% CI 0.789 to 1.734) was not associated with pCR (Supplementary Table 1).

Multivariable analysis demonstrated that clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, p < 0.001, OR = 0.250, 95% CI 0.125 to 0.499) and Ki67 index (Zero vs. Low, p = 0.032, OR = 3.418, 95% CI 1.111 to 10.518) were independent predictive factors for pCR in HER2-Low group (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1B). Only clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, p = 0.029, OR = 0.458, 95% CI 0.227 to 0.924) was an independent predictive factor for pCR in HER2-Zero group (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1C). Nevertheless, clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, p < 0.001, OR = 0.338, 95% CI 0.207 to 0.550), clinical stage (III vs. I–II, p = 0.031, OR = 0.571, 95% CI 0.343 to 0.951) and Ki67 index (Zero vs. Low, p = 0.037, OR = 2.236, 95% CI 1.051 to 4.756) were all independent predictive factors for pCR in the overall patients (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1D).

Prognosis between pCR and non-pCR patients after NACT

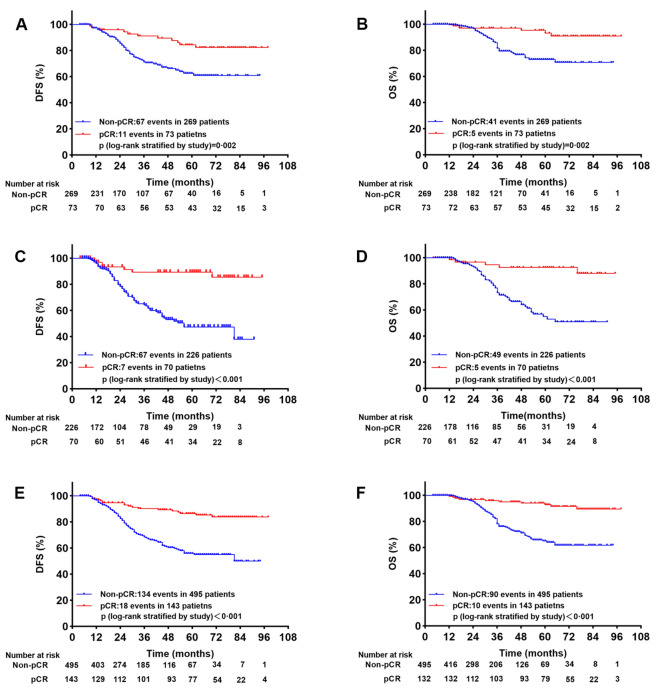

The median follow-up time was 34 months (range from 4 to 98 months). In HER2-Low patients, we detected 78 locoregional and distant relapse (67 cases in non-pCR group and 11 cases in pCR group) and 46 death events (41 cases in non-pCR group and five cases in pCR group). The 5-year DFS and 5-year OS rates for pCR and non-pCR group were 84.3% vs. 62.6% (p = 0.002) and 93.1% vs. 73.0% (p = 0.002), respectively (Fig. 2A, B). Meanwhile, 74 locoregional and distant relapse (67 cases in non-pCR group and 7 cases in pCR group) and 54 death events (49 cases in non-pCR group and 5 cases in pCR group) occurred in HER2-Zero patients. The 5-year DFS and 5-year OS rates for pCR and non-pCR group were 89.3% vs. 47.4% (p < 0.001) and 92.5% vs. 55.0% (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2C, D). In general, in the overall patients, 152 locoregional and distant relapse (134 cases in non-pCR group and 17 cases in pCR group) and 100 death events (90 cases in non-pCR group and ten cases in pCR group) occurred. The 5-year DFS and 5-year OS rates for pCR and non-pCR group were 86.4% vs. 55.9% (p < 0.001) and 92.8% vs. 65.0% (p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2E, F).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for DFS and OS between pCR and non-pCR in HER2-Low group (A,B), HER-2 Zero group (C,D) and overall patients (E,F).

Taken together, the survival of pCR group after NACT significantly improved in comparison to non-pCR group either in HER2-Low or in HER2-Zero patients.

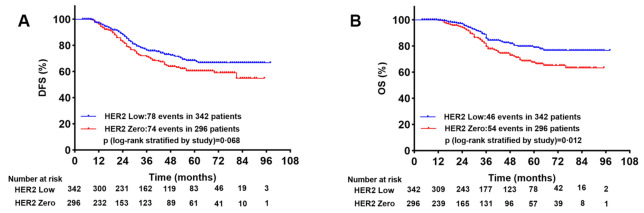

Survival analysis between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients

In order to explore the association between prognosis and HER2 status in TNBCs, we compared the DFS and OS in HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients. In total, we found 78 cases of locoregional and distant relapse in HER2-Low group, and 74 cases in HER2-Zero group. The 5-year DFS rates for HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients were 68.4% and 60.5%, respectively. Although HER2-low patients had a longer DFS than HER2-Zero patients, there was no significant difference (p = 0.068, Fig. 3A). Meanwhile, we detected 46 and 54 death events respectively in HER2-Low group and in HER2-Zero group. The 5-year OS rates for HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients were 78.8% and 66.4%, respectively. Patients with HER2-low had a significantly longer OS than patients with HER2-zero (p = 0.012, Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for DFS (A) and OS (B) between HER2-Low and HER-Zero group.

We further explored the prognostic factors in HER2-Low, HER2-Zero and the overall patients by using univariate and multivariate COX regression analysis. For DFS, clinical tumor size (cT3–4 vs. cT1–2, HR = 1.587, 95% CI 1.017 to 2.476, p = 0.042), clinical lymph node involvement (cN1–3 vs. cN0, HR = 1.829, 95% CI 1.040 to 3.217, p = 0.036), clinical stage (III vs. I–II, HR = 2.361, 95% CI 1.449 to 3.849, p < 0.001) and NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.367, 95% CI 0.193 to 0.700, p = 0.002) were predictive factors in HER-2 Low patients by univariate analysis, however, only NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.462, 95% CI 0.223–0.912, p = 0.026) was the independent predictive factor after adjusting confounding factors by multivariate analysis. In HER2-Zero patients, both clinical stage (III vs. I–II, HR = 2.794, 95% CI 1.443 to 5.409, p = 0.002) and NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.170, 95% CI 0.072 to 0.400, p < 0.001) were independent predictive factors for DFS. In the overall patients, besides clinical stage (III vs. I–II, HR = 2.080, 95% CI 1.327 to 3.262, p = 0.001) and NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.312, 95% CI 0.187 to 0.521, p < 0.001), HER2 status (Zero vs. Low, HR = 1.417, 95% CI 1.029 to 1.953, p = 0.033) status was also a significant predictive factor for DFS after adjusting confounding factors by multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate COX-regression of DSF in HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients.

| DFS | HER2-Low | HER2-Zero | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| HER2 status (Zero vs Low) | 1.349(0.981–1.854) | 0.065 | 1.417(1.029–1.953) | 0.033 | ||||||||

| Age (≥ 50 vs. < 50) | 1.131(0.721–1.773) | 0.593 | 1.240(0.782–1.968) | 0.361 | 1.174(0.851–1.620) | 0.328 | ||||||

| BMI (≥ 30 vs. < 30) | 1.289(0.761–2.186) | 0.345 | 1.162(0.668–2.024) | 0.595 | 1.271(0.870–1.855) | 0.404 | ||||||

| Menstrual status (post. vs. pre.) | 0.891(0.570–1.392) | 0.611 | 1.030(0.653–1.625) | 0.899 | 0.936(0.680–1.287) | 0.682 | ||||||

| cT3–4 vs. cT1–2 | 1.587(1.017–2.476) | 0.042 | 1.093(0.650–1.838) | 0.738 | 1.249(0.791–1.972) | 0.341 | 0.849(0.511–1.410) | 0.527 | 1.401(1.019–1.927) | 0.038 | 0.956(0.666–1.372) | 0.808 |

| cN1–2 vs. cN0 | 1.829(1.040–3.217) | 0.036 | 1.080(0.554–2.107) | 0.820 | 1.644(0.918–2.943) | 0.094 | 0.626(0.301–1.306) | 0.212 | 1.759(1.172–2.638) | 0.006 | 0.884(0.543–1.440) | 0.620 |

| Clinical stage (III vs. I–II) | 2.361(1.449–3.849) | < 0.001 | 1.796(0.946–3.412) | 0.073 | 2.463(1.483–4.091) | < 0.001 | 2.794(1.443–5.409) | 0.002 | 2.344(1.652–3.325) | < 0.001 | 2.080(1.327–3.262) | 0.001 |

| Histological type (others vs. IDC) | 1.707(0.985–2.960) | 0.057 | 1.237(0.666–2.296) | 0.501 | 1.400(0.923–2.122) | 0.113 | ||||||

| Histological grade (III vs. I, II) | 0.837(0.522–1.340) | 0.458 | 1.136(0.705–1.831) | 0.602 | 0.951(0.680–1.330) | 0.769 | ||||||

| Ki67 index (> 14 vs. ≤ 14) | 1.257(0.605–2.612) | 0.540 | 1.350(0.645–2.826) | 0.425 | 0.903(0.414–1.967) | 0.797 | 0.942(0.429–2.066) | 0.881 | 1.120(0.657–1.908) | 0.678 | 1.197(0.701–2.045) | 0.510 |

| pCR vs. non-pCR | 0.367(0.193–0.700) | 0.002 | 0.462(0.223–0.912) | 0.026 | 0.166(0.072–0.385) | < 0.001 | 0.170(0.072–0.400) | < 0.001 | 0.278(0.169–0.456) | < 0.001 | 0.312(0.187–0.521) | < 0.001 |

BMI body mass index, IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, pCR pathologic complete response.

For OS, both clinical stage (III vs. I–II, HR = 2.116, 95% CI 1.140 to 3.930, p = 0.018) and NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.252, 95% CI 0.099 to 0.643, p = 0.004) were predictive factors in HER2-Low patients by univariate analysis. However, after adjusting confounding factors by multivariate analysis, NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.279, 95% CI 0.104 to 0.747, p = 0.011) was the only independent predictive factor. In HER2-Zero patients, both clinical stage (III vs. I-II, HR = 2.189, 95% CI 1.229 to 3.897, p = 0.008) and NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.165, 95% CI 0.064 to 0.427, p < 0.001) were independent predictive factors for OS. Similar to the DFS, in the overall patients, HER2 status (Zero vs. Low, HR = 1.798, 95% CI 1.207 to 2.676, p = 0.004), clinical stage (III vs. I–II, HR = 2.318, 95% CI 1.349 to 3.985, p = 0.002) and NACT effect (pCR vs. non-pCR, HR = 0.219, 95% CI 0.112 to 0.431, p < 0.001) were all independent predictive factors after multivariate analysis for OS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate COX-regression of OS in HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients.

| OS | HER2-Low | HER2-Zero | Overall | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| HER2 status (Zero vs. Low) | 1.646(1.110–2.439) | 0.013 | 1.798(1.207–2.676) | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Age (≥ 50 vs. < 50) | 1.610(0.869–2.985) | 0.130 | 1.256(0.731–2.160) | 0.409 | 1.371(0.915–2.054) | 0.126 | ||||||

| BMI (≥ 30 vs. < 30) | 1333(0.661–2.689) | 0.422 | 1.240(0.652–2.360) | 0.511 | 1.300(0.809–2.088) | 0.279 | ||||||

| Menstrual status (post. vs. pre.) | 1.067(0.598–1.904) | 0.825 | 1.261(0.737–2.159) | 0.397 | 1.175(0.793–1.741) | 0.422 | ||||||

| cT3–4 vs. cT1–2 | 1.128(0.629–2.021) | 0.687 | 0.714(0.366–1.395) | 0.325 | 1.118(0.655–1.907) | 0.682 | 0.714(0.394–1.291) | 0.264 | 1.160(0.783–1.718) | 0.460 | 0.737(0.474–1.147) | 0.177 |

| cN1–3 vs. cN0 | 1.670(0.827–3.371) | 0.153 | 0.847(0.369–1.941) | 0.694 | 1.349(0.709–2.566) | 0.361 | 0.448(0.194–1.038) | 0.061 | 1.529(0.952–2.457) | 0.079 | 0.645(0.361–1.151)) | 0.138 |

| Clinical stage (III vs. I–II) | 2.116(1.140–3.930) | 0.018 | 1.887(0.856–4.160) | 0.115 | 2.189(1.229–3.897) | 0.008 | 3.064(1.418–6.623) | 0.004 | 2.168(1.421–3.306) | < 0.001 | 2.318(1.349–3.985) | 0.002 |

| Histological type (others vs. IDC) | 1.681(0.810–3.492) | 0.163 | 0.935(0.423–2.070) | 0.869 | 1.265(0.741–2.160) | 0.389 | ||||||

| Histological grade (III vs. I, II) | 0.676(0.356–1.285) | 0.232 | 1.063(0.603–1.871) | 0.833 | 0.838 (0.549–1.281) | 0.414 | ||||||

| Ki67 index (> 14 vs. ≤ 14) | 1.487(0.533–4.148) | 0.448 | 1.746(0.622–4.897) | 0.290 | 0.615(0.278–1.362) | 0.231 | 0.616(0.275–1.379) | 0.238 | 0.978(0.523–1.830) | 0.944 | 1.032(0.550–1.938) | 0.921 |

| pCR vs. non-pCR | 0.252(0.099–0.643) | 0.004 | 0.279(0.104–0.747) | 0.011 | 0.176(0.070–0.445) | < 0.001 | 0.165(0.064–0.427) | < 0.001 | 0.210(0.109–0.406) | < 0.001 | 0.219(0.112–0.431) | < 0.001 |

BMI body mass index, IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, pCR pathologic complete response.

Discussion

With the advance in muti-disciplinary care and treatment, the deep understanding of tumor markers and the development of precision therapy, breast cancer recurrence rates and survival have improved dramatically. In the last decade, the treatment algorithm of TNBC has shifted from upfront surgery followed by adjuvant systemic therapy to a preference for implementing preoperative systemic therapy, especially for stage II-III TNBC patients. Recently, neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy was proved to significantly increased the pCR and prolonged the event-free survival (EFS) than neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone in early TNBC patients21,22. Anti-PD1 (pembrolizumab) with chemotherapy has become the standard neoadjuvant treatment for TNBC, regardless of PD-L1 expression or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) number. The goals of NACT administration include providing the opportunity to monitor the individual drug response, rendering unresectable tumors into resectable ones, reducing the surgical extent and improving survival outcomes23. In TNBC patients, the achievement of pCR after NACT is one of the most important metrics of improved outcomes in terms of OS and DFS, nevertheless non-pCR generally implies of early recurrences and mortality7,24.

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest retrospective, real-world study from China to investigate the efficacy and prognosis of the association between neoadjuvant chemotherapy and HER2 expression status in TNBC. Young age (< 50 years), premenopause, T3–4, lymph node positivity, Grade 3 and high Ki-67 were deemed as high risk clinicopathological factors. Nevertheless, of entire 638 cases of TNBC patients included, there was no statistical difference between HER2-Zero group and HER2-Low group in terms of baseline demographics and clinical-pathological characteristics. The results of these baseline comparisons were consistent with a previous research, which conducted a comparison between 49 cases of HER2-Low patients and 264 cases of HER2-Zero patients25.

In the research reported by Spring et al.14, the pCR rate was 32.6% (range 20.3–62.2%) in TNBC. The pCR rate from our center was 22.4% in the entire cohort, which was consistent with our previous data that reported the pCR = 22.1% in TNBC patients26. The low pCR rate in present study perhaps was associated with a greater tumor burden, nearly two thirds of overall patients axillary lymph nodes were positive and more than half patients were clinical stage III. Meanwhile, the great majority (> 90%) women in this analysis received mastectomy ultimately after NACT, to a certain extent, reflecting the fact that most patients had a large tumor size. Although pCR rate in HER2-Low group was slightly lower in comparison with the HER2-Zero group (21.3% vs.23.6%), there was no statistic difference between the two groups (p = 0.487). Previous studies have also explored the predictors for achieving pCR in TNBC and confirmed that high expression of Ki67, the abundance of TILs, an expression of PD-L1, immune gene signatures and platinum-based therapy were most commonly reported biomarkers associated with the pCR16,27. Correspondingly, in present study we found only high Ki67 index (> 14%) was an independent predictive factor for pCR both in HER2-Low and the overall cohort after logistic univariate and multivariate analyses. Moreover, lymph node involvement was a statistically significantly different factor in all three cohorts, and clinical stage was an independent factor only in overall cohort. Our previous study indicated that positive expression of AR was also an independent risk factor for pCR after neoadjuvant therapy in TNBC (p = 0.017, OR = 2.758, 95% CI 1.564 to 4.013)26. In July 2021, pembrolizumab was approved in early-stage, high-risk TNBC neoadjuvant therapy by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based on notable improvement in pCR rate and 3-year EFS compared to NACT alone in TNBC21,22. The approval of pembrolizumab marked a new era of neoadjuvant immunotherapy entering the clinic practice28. However, due to TILs and PDL-1 were not routinely tested in our center in previous years, we have not analyzed the association between PDL-1, TILs expression status and pCR rate.

Consistent with previous research, the pCR patients had a better survival in comparison with non-pCR patients after NCAT in TNBC patients7,24. Our research confirmed the remarkable improved survival (DFS and OS) of patients who obtained pCR after NACT. Particularly, in the overall cohort, patients with pCR had a 5-year DFS of 86.4%, while those non-pCR patients had a 5-year DFS of 55.9%. On the other hand, the 5-year OS in patients with pCR was 92.8% compared to 65% of those non-pCR patients. A recent meta-analysis included 25 neoadjuvant studies with over 4,000 early stage TNBC patients reported that achieving pCR was associated with a 76% lower risk of progression, recurrence, or death. This study also suggested 5-year EFS with and without pCR was 86% vs. 50% respectively for TNBC patients, while 5-year OS with and without pCR was 92% vs. 58% respectively for patients29, which was consist with our findings. Furthermore, as far as we know, this was the first study mainly to compare the pCR rate and survival outcomes between HER2 status in TNBC. we found that survival benefits of patients with pCR also existed in HER2-Low and HER2-Zero cohort. The non-pCR patients in HER2-Zero group had the worst survival outcomes, with the 5-year DFS and 5-year OS was 47.4% and 55.0%, respectively. Therefore, to some extent, achievement of pCR could be an endpoint of neoadjuvant therapy that better predict the survival benefits of HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients.

According to our data, HER2-Low patients had a significantly longer OS than HER2-Zero patients (p = 0.012). Although we found that HER2-low patients had a longer DFS than HER2-Zero patients, there was no statistical difference (p = 0.068). Survival differences between HER2-Low and HER2-Zero tumors varied across recent studies. Both de Moura Leite et al.25 and Domergue et al.30 single center retrospective studies indicated that no statistical survival differences were found between HER2-low patients vs. HER2-Zero patients in early-stage TNBC after NACT. However, a pooled analysis of four prospective neoadjuvant clinical trials demonstrated that hormone receptor-negative patients with HER2-Low tumors had significantly longer survival (3-year DFS and 3-year OS) than those with HER2-Zero tumors31. Furthermore, two recent published meta-analysis also showed that HER2-Low patients were found to be associated with prolonged DFS and OS compared to HER2-Zero patients after NACT in early-stage TNBC patients32,33. To date, the inconsistent evidence was not sufficient to sustain the definition of HER2-low breast cancer as a distinct subtype correlated with prognosis. Therefore, further basic research was warranted to reveal the HER2-Low potential impacts on tumor biological characteristics and clinical features.

Currently, targeting HER2-low expression with traditional anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies has failed to display clinical benefit18. However, the development of novel ADCs had the potential to add critical new therapeutic options for breast cancer patients with low HER2 expression. Multiple anti-HER2 ADCs including trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) exhibited antitumor efficacy in trials enrolling HER2-Low metastatic breast cancer patients34. The DESTINY-Breast 04 clinical trial demonstrated that T-DXd improved progression free survival (PFS) and OS in HER2-Low metastatic breast cancer compared with traditional chemotherapy treatment19. These data have confirmed the clinical importance of HER2-Low expression in TNBC. Therefore, clinical trials to explore systemic therapy efficacy of HER2-Low breast cancer in the non-metastatic setting should be conducted in near future. In addition, there are still some limitations in present study. First, this is a retrospective single-center study, which might lead to certain bias in the results. Second, as our center did not routinely detect TNBC immunology related markers such as TILs and PDL-1 in previous years, no comprehensive analysis of these was conducted. Moreover, due to BRCA1/2 mutation testing is not yet covered by basic medical insurance in China, most of the patients were not tested because of the relative expensive testing costs. Therefore, we did not collect this data. Further multi-center randomized research is needed to determine whether HER2-Low could be a more favorable prognostic marker to make individual treatment decisions in future.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study indicated that there was no statistical difference in pCR rate between HER2-Low patients and HER2-Zero patients in TNBC. However, pCR following NACT was associated with improved DFS and OS in both HER2-Low and HER2-Zero patients. HER2-Low patients had significantly longer OS than HER2-Zero patients. Our data offered certain theoretic basis for future diagnostic concepts, general understanding of the HER2-Low and HER2-Zero tumors, and promoting the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors listed for their contributions to this study.

Abbreviations

- AR

Androgen receptor

- ER

Estrogen receptor

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- HR

Hormone receptor

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- TNBC

Triple negative breast cancer

- BMI

Body mass index

- RECIST

Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- pCR

Pathologic complete response

- NAC

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- DFS

Disease free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression free survival

- EFS

Event free survival

- ADC

Antibody–drug conjugates

Author contributions

Z.S. analyzed the data and wrote the article. Y. L. collected the data, followed up the patients. X. F. and X. L. helped to collect the data. J. M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. J. Z. is the guarantor of this work and is responsible for the completeness of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81502306) and the National Natural Science Foundation Cultivation Project of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (No. 230210).

Data availability

To safeguard patient privacy, the datasets are available only from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-67795-z.

References

- 1.Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin.71(1), 7–33 (2021). 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palma, G. et al. Triple negative breast cancer: Looking for the missing link between biology and treatments. Oncotarget.6(29), 26560–26574 (2015). 10.18632/oncotarget.5306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng, Y. Z., Liu, Y., Deng, Z. H., Liu, G. W. & Xie, N. Determining prognostic factors and optimal surgical intervention for early-onset triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Oncol.12, 910765 (2022). 10.3389/fonc.2022.910765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle, P. Triple-negative breast cancer: Epidemiological considerations and recommendations. Ann. Oncol.23(Suppl 6), 7–12 (2012). 10.1093/annonc/mds187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris, G. J. et al. Differences in breast carcinoma characteristics in newly diagnosed African–American and Caucasian patients: A single-institution compilation compared with the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer.110(4), 876–884 (2007). 10.1002/cncr.22836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liedtke, C. et al. The prognostic impact of age in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.138(2), 591–599 (2013). 10.1007/s10549-013-2461-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liedtke, C. et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.41(10), 1809–1815 (2023). 10.1200/JCO.22.02572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid, P. et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.379(22), 2108–2121 (2018). 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winer, E. P. et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-119): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.22(4), 499–511 (2021). 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30754-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garufi, G. et al. Updated neoadjuvant treatment landscape for early triple negative breast cancer: Immunotherapy, potential predictive biomarkers, and novel agents. Cancers (Basel)14(17), 22 (2022). 10.3390/cancers14174064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bianchini, G., De Angelis, C., Licata, L. & Gianni, L. Treatment landscape of triple-negative breast cancer—Expanded options, evolving needs. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.19(2), 91–113 (2022). 10.1038/s41571-021-00565-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson, A. M. & Moulder-Thompson, S. L. Neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. Ann Oncol.23(Suppl 10), 231–236 (2012). 10.1093/annonc/mds324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tadros, A. B. et al. Identification of patients with documented pathologic complete response in the breast after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for omission of axillary surgery. JAMA Surg.152(7), 665–670 (2017). 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spring, L. M. et al. Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and impact on breast cancer recurrence and survival: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin. Cancer Res.26(12), 2838–2848 (2020). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Minckwitz, G. et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol.30(15), 1796–1804 (2012). 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gass, P. et al. Prediction of pathological complete response and prognosis in patients with neoadjuvant treatment for triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer18(1), 1051 (2018). 10.1186/s12885-018-4925-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff, A. C. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline focused update. J. Clin. Oncol.36(20), 2105–2122 (2018). 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.8738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarantino, P. et al. HER2-Low breast cancer: Pathological and clinical landscape. J. Clin. Oncol.38(17), 1951–1962 (2020). 10.1200/JCO.19.02488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modi, S. et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-Low advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.387(1), 9–20 (2022). 10.1056/NEJMoa2203690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang, Q., Ma, D., Gao, R. F. & Yu, K. D. Effect of Ki-67 expression levels and histological grade on breast cancer early relapse in patients with different immunohistochemical-based subtypes. Sci. Rep.10(1), 7648 (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-64523-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid, P. et al. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.382(9), 810–821 (2020). 10.1056/NEJMoa1910549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmid, P. et al. Event-free survival with Pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.386(6), 556–567 (2022). 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyder, T., Bhattacharya, S., Gade, K., Nasrazadani, A. & Brufsky, A. M. Approaching neoadjuvant therapy in the management of early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press).13, 199–211 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortazar, P. et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet.384(9938), 164–172 (2014). 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Moura, L. L. et al. HER2-low status and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2 negative early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.190(1), 155–163 (2021). 10.1007/s10549-021-06365-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi, Z. et al. Evaluation of predictive and prognostic value of androgen receptor expression in breast cancer subtypes treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Discov. Oncol.14(1), 49 (2023). 10.1007/s12672-023-00660-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Ende, N. S. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer and predictive markers of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24(3), 13 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagegni, N. A., Davis, A. A., Clifton, K. K. & Ademuyiwa, F. O. Targeted treatment for high-risk early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: Spotlight on Pembrolizumab. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press).14, 113–123 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, M. et al. Association of pathologic complete response with long-term survival outcomes in triple-negative breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Res.80(24), 5427–5434 (2020). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domergue, C. et al. Impact of HER2 status on pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in early triple-negative breast cancer. Cancers (Basel)14(10), 2509 (2022). 10.3390/cancers14102509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denkert, C. et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: Pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol.22(8), 1151–1161 (2021). 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00301-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, C. et al. Survival differences between HER2-0 and HER2-low-expressing breast cancer—A meta-analysis of early breast cancer patients. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.185, 103962 (2023). 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.103962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ergun, Y., Akagunduz, B., Karacin, C., Turker, S. & Ucar, G. The effect of HER2-Low status on pathological complete response and survival in triple-negative breast cancer: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer23(6), 567–575 (2023). 10.1016/j.clbc.2023.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarantino, P. et al. ESMO expert consensus statements (ECS) on the definition, diagnosis, and management of HER2-low breast cancer. Ann. Oncol.34(8), 645–659 (2023). 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To safeguard patient privacy, the datasets are available only from the corresponding author on reasonable request.