Abstract

Study design

A prospective study.

Objective

To investigate the incidence of vertebral artery (VA) occlusion and whether anterior spinal artery (ASA) is occluded in cervical facet dislocation.

Setting

University hospital, China.

Methods

During a 2-year period, 21 conventional patients with cervical facet dislocation were prospectively enrolled. All patients received computed tomography angiography (CTA) to assess the patency of the VA, anterior radiculomedullary arteries (ARAs), and ASA at the time of injury. Clinical data were documented, including demographics, symptomatic vertebrobasilar ischemia, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (ASIA) grades, and ASA and VA radiological characteristics.

Results

VA unilateral occlusion occurred in 5 of 21 patients (24%), including 2 with unilateral facet dislocation and 3 with bilateral facet dislocation. No ASA occlusion was found in all 21 patients, including 5 with VA unilateral occlusion. No patients had symptomatic vertebrobasilar ischemia.

Conclusions

VA occlusion occurs in approximately one-fourth of cervical facet dislocations, with infrequent symptomatic vertebrobasilar ischemia. ASA is not occluded following cervical facet dislocation, even with unilateral VA occlusion.

Subject terms: Spinal cord diseases, Epidemiology, Trauma

Introduction

Traumatic cervical facet dislocations represent 6.7% of substantial cervical spine injuries. Vertebral artery (VA) occlusion has been found to occur in roughly 18% of all blunt cervical spine traumas [1, 2]. The incidence of VA occlusion varies by injury types, including distractive flexion, compressive flexion, and compressive extension. The distractive flexion injury, which is closely related to cervical facet dislocation, has the highest incidence. The reported incidence of VA occlusion in facet dislocation was 75% by Louw et al. [3], 46% by Willis et al. [4], 28% by Giacobetti et al. [1], 29% by Taneichi et al. [2], and 21% by Zhang et al. [5]. This difference is likely due to the approach used to determine VA occlusion. It presents the higher incidence of VA occlusion using digital subtraction angiography (DSA) [3, 4] than magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) [1, 2]. However, no prospective analysis with computed tomography angiography (CTA) has been described.

The anterior spinal artery (ASA) runs along the entire length of the anterior surface of the spinal cord and distributes blood to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. ASA receives anterior radiculomedullary arteries (ARAs) at cervical regions. ARA originates from the VA in cervical level. So, it is easily hypothesized that ASA may be occluded by anterior compression or deprivation of blood supplies from ARA and VA during cervical facet dislocation. We have previously shown that ASA occlusion is not seen in acute blunt cervical fractures or spinal cord injury [6]. However, whether ASA is occluded has yet to be confirmed in cervical facet dislocation. To further elucidate the incidence of VA occlusion and the occurrence of ASA occlusion as indicated by CTA, a prospective study of consecutive patients with subaxial cervical facet dislocations was initiated.

Patients and methods

Patients

The Medical Ethics Committee of Xinqiao Hospital of Army Medical University approved this study, and all participants provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. During a 2-year period from January 2009 to December 2010, 21 consecutive patients with subaxial cervical facet dislocations were admitted or transferred to and treated surgically in the investigator’s group. In these 21 patients (18 male and 3 female), the distribution of spine level was from C3/4 to C7/T1; the etiologic diagnosis included 6 unilateral and 15 bilateral facet dislocations; the neurologic status was comprised in 9 patients with American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Classification A, 4 with B, 3 with D, and 5 with E; the surgical spinal decompression, reduction and fusion was performed in all 21 patients; the follow-ups were conducted for more than 12 months.

CTA of the ASA and VA

CTA allows visualization of both spinal cord and bone anatomy, which is beneficial for the identification of the ASA and VA in cervical levels after cervical facet dislocation. CTA of the ASA and identification of the ASA was followed the protocol described previously [6]. Briefly, patients underwent imaging with 64-slice MDCT scanners (LightSpeed 64, GE Medical System, Milwaukee, WI, USA). All CT scan images were obtained with a rotation of 0.5 s, nominal detector widths of 0.625 mm, and pitches of 0.984, 120 kV and 480 mA. Transverse sections were reconstructed with 50% overlap relative to the effective section thickness of 0.6 mm. Lohexol (Amersham Health Princeton, NJ, USA) was administered through an antecubital vein at a dose of 120–150 ml (350 mg/ml−1) and a rate of 5 m/s−1. The scan delay was determined by a preliminary 20 ml test injection at the level of the basilar artery. To examine the ASA transverse sections, multiplanar reformations, curved planar reformation and thin-slab (2–4 mm) maximum intensity projections were generated and displayed on a workstation (Advantage Workstation 4.3, GE Medical Systems) with window and level settings selected to maximize arterial to background discrimination.

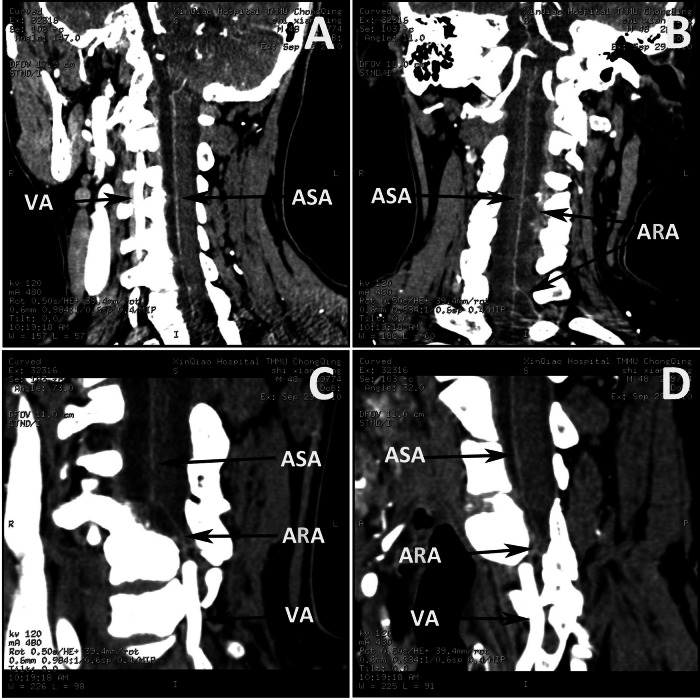

Identification of the ASA

The ASA was identified by maintaining the maximum intensity projection slab parallel to the anterior surface of the spinal cord at each vertebral level assessed from C1 to C7. An enhanced artery on the midline ventral surface of the spinal cord was interpreted as the ASA (Fig. 1A). At the same time, an artery originating from the VA and coursing through the intervertebral foramen to join the ASA in a hairpin configuration was interpreted as the ARA. Covisualization of the ASA and the ARA was used to identify the ASA (Fig. 1B); the covisualization of veins was not a criterion for identifying the ASA. Another criterion was that the ASA originated from the VA in the skull base (Fig. 1C, D). Interrater reliability, in the form of the consensual identification of the ASA by two radiologists, was required.

Fig. 1. Identification of the ASA, ARA and VA.

Coronal (A), sagittal (B), and oblique-sagittal (C, D) CTA views showing the ASA, and ARA and VA (arrows) as the suppliers of the ASA.

Identification of the VA

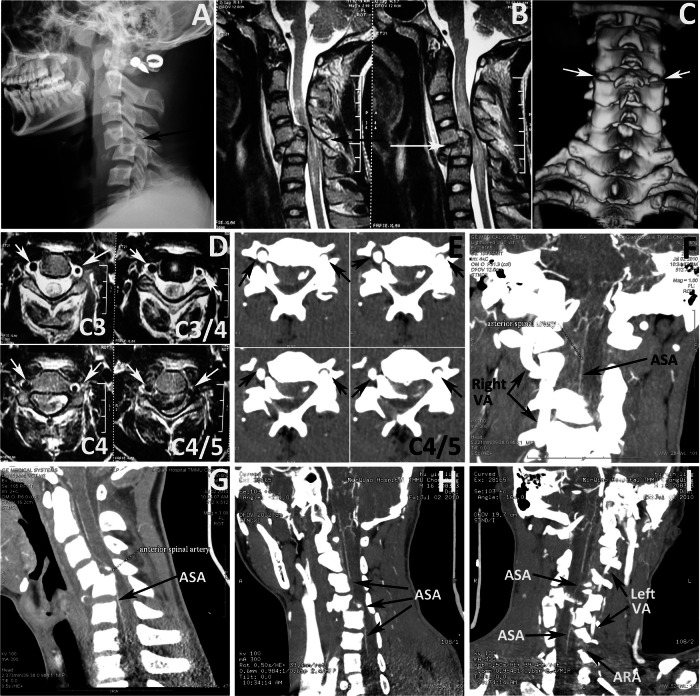

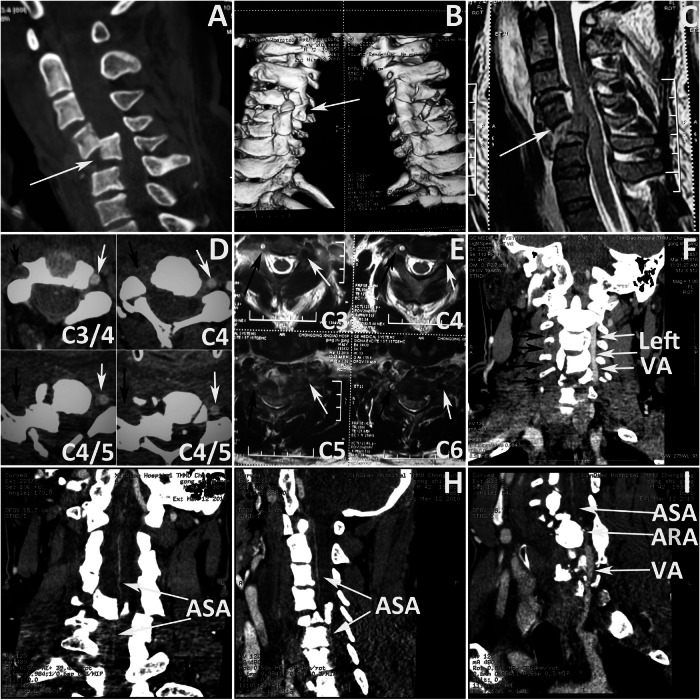

The VA was identified by axial MRI, axial CTA, coronal CTA, and oblique CTA images. VA occlusion was diagnosed on axial MRIs with asymmetrical flow void and/or absence of flow void in either of both Vas [2, 7]. The absence of VA images in axial CTA, coronal CTA, and oblique CTA was also identified as VA occlusion (Figs. 2D–I and 3D–I). The diagnosis of VA occlusion was achieved by consensus between 2 neuroradiologists to avoid clinical subjectivity.

Fig. 2. Illustrative case of ASA visualization without VA occlusion (16 years old case).

A Lateral radiograph showing C5 fracture and dislocation. B Sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing cord hyperintensity at C3–C6 and C5 fracture (arrow). C Three-dimension CT reconstruction image showing the bilateral C4/5 facet dislocation (arrows). D T2 axial MRI showing bilateral intact VA at C3 to C4/5 (arrows). E Axial CTA showing bilateral intact VA at C4/5 (black arrows). F coronal view of CTA showing no ASA occlusion (black arrow) and right intact VA (black arrows). Sagittal (G) and oblique (H) views of CTA showing no ASA occlusion (black arrows). I oblique views of CTA showing no ASA occlusion (black arrows), intact VA (black arrows) and ARA (black arrow).

Fig. 3. Illustrative case of ASA visualization with VA unilateral occlusion (case 3).

A Sagittal CT image showing C4/5 dislocation (arrow). B Three-dimension CT reconstruction images showing right C4/5 facet dislocation (arrow). C Sagittal T2-weighted MRI showing cord hyperintensity at C3–C6 and C4/5 dislocation. D Axial CTA showing left intact VA (white arrows) and right occluded VA (black arrows) at C3/4 to C4/5. E Axial T2- weighted MRI showing left intact VA (white arrows) and right occluded VA (black arrows) at C3–C6. F Coronal view of CTA showing left intact VA (white arrows) and right occluded VA (black arrows). Coronal (G) and sagittal (H) views of CTA showing no ASA occlusion (arrows). I Oblique views of CTA showing no ASA occlusion (arrows), intact VA (arrows) and ARA (arrow).

Results

VA, ARA and ASA visualization

In all 21 patients with cervical facet dislocation, both the VA and ASA were successfully visualized. The course of the ASA, extending from C1 to C7, was clearly visualized in sagittal, coronal, and transverse views. The ASA ran along the entire length of the anterior surface of the spinal cord. The ARA was also visualized in CTA for all cases. The VA and its occlusion were visualized in axial MRI, axial CTA, coronal CTA, and oblique CTA images (Figs. 2D–I and 3D–I).

The incidence of VA occlusion

VA occlusion was identified on CTA in 5 of the 21 patients (24%) (Table 1). There were 4 male and 1 female patients, with an average age of 48.4 years (range 42–56 years). Unilateral occlusion of the right VA occurred in 3 patients, and of the left in 2. No patients occurred bilateral VA occlusions. Levels of cervical facet dislocations were identified in C3/4 segment in 1 patient, C4/5 in 1, and C5/6 in 3. Among the 5 patients with VA occlusion, 3 had bilateral facet dislocation, and 2 had unilateral facet dislocation. VA occlusion was located in cephalic or dislocated vertebras (Fig. 3A–I). The length of VA occlusion extended cephalad from 2 to 5 levels, but had not reached C1.

Table 1.

Clinical summary of five VA occlusion patients.

| Case no. | Sex / Age | Level | Dislocation | VA occlusion | Length of VA Occlusion/Levels | ASA occlusion | ASIA on admission/ 12 moth follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M/47 | C3/4 | Unilateral | Left | C3-C4/2 | None | B/C |

| 2 | F/56 | C5/6 | Bilateral | Left | C3-C5/3 | None | A/A |

| 3 | M/42 | C4/5 | Bilateral | Right | C2-C6/5 | None | A/A |

| 4 | M/52 | C5/6 | Bilateral | Right | C3-C5/3 | None | A/A |

| 5 | M/45 | C5/6 | Unilateral | Right | C3-C5/3 | None | B/D |

C Cervical, F Female, M Male.

The occurrence of ASA occlusion

In all 21 patients with cervical dislocation, no ASA occlusion was found in the absence of VA occlusion (16 patients) (Fig. 2A–I), nor was it found in cases with VA unilateral occlusion (5 patients) (Fig. 3A–I).

Neurological status

All 5 patients with VA occlusion had spinal cord injury (Table 1). Among them, 3 were classified as ASIA grade A, and 2 as grade B. None of 5 patients with VA occlusion had radiographic evidence of brain trauma at the time of injury. Regarding clinical manifestations related to vertebrobasilar ischemia, none of 5 patients with unilateral VA occlusion presented symptoms, so no patient underwent systemic anticoagulation therapy. No neurologic impairments due to vertebrobasilar ischemia were observed during the follow-up period. None of the 21 patients experienced surgical complications or neurological deterioration after surgical reduction, decompression, and spinal fusion.

Discussion

In the current prospective study, the incidence of VA occlusion in patients with cervical facet dislocation was 5 out of 21 (24%). This rate is comparable to previously reported incidences: 7 out of 25 (28%) by Giacobetti et al. [1], and 6 out of 21 (29%) by Taneichi et al. [2], as determined by MRA studies. Higher incidences were reported in DSA studies: 9 out of 12 (75%) by Louw et al. [3], and 12 out of 26 (46%) by Willis et al. [4]. Traumatic VA occlusion typically begins with intimal disruption, followed by thrombus formation [4, 8]. The timing of the initial angiography could likely reason for the higher incidence rates observed in DSA studies.

Another finding in this study is that no ASA occlusion occurred in cases of cervical facet dislocation, even when there was unilateral VA occlusion. These negative findings aligned with our previous reports, which noted that rupture or occlusion of ASA is not observed in instances of acute blunt cervical spinal cord injury [6], nor in patients with cervical compressive myelopathy patients with spinal canal sagittal diameter compression exceeding 80% [9], nor in those with cervical spondylotic amyotrophy and cervical compressive myelopathy patients exhibiting “snake-eye” MRI sign [10]. In cases of cervical facet dislocation, spinal cord injury encompasses damages to both neural tissue and vascular damage at the site of contusion. Yet, in our study of 21 patients, no ASA occlusion was detected, including among the 5 with ASIA Grade A and B who presented with unilateral VA occlusion. This suggests that the spinal cord is more susceptible to injury and compression than the ASA on its anterior surface.

ASA receives its supply from ARAs, which, like the radicular arteries, enter the spinal canal alongside the nerve roots. The ASA extends from the level of C1 until T3, and is supplied at the C3 level by the VAs and at the level C6/C7 by the cervical ascending arteries [11, 12]. In other words, there are at least 4 ARAs supply ASA on each side within the cervical spine. VA unilateral occlusion in cervical facet dislocation only reduced the blood supply from ARA at the C3 level and/or C6/C7 level. The present findings suggest when there is unilateral VA occlusion, the contralateral VA and cervical ascending artery can still supply the ASA via the ARAs. This explains why no occlusion of the ASA was observed in patients with unilateral VA occlusion.

Acute traumatic spinal cord injury encompasses both primary and secondary cord injuries, which are related to ischemia, axonal damage, swelling, edema, and hemorrhaging. These pathological changes are characterized by irregular T2 hyperintensity signals on MRI [13]. Among them, ischemia is a pivotal element and contributor to the secondary pathogenesis of spinal cord injury. However, the extent to which artery ischemia contributes to these secondary pathologies remains indeterminate. In this series, no ASA occlusion was observed in any of 21 patients, including the 5 with VA unilateral occlusions. This finding suggests that spinal cord ischemia can occur despite an intact ASA blood supply. Spinal cord ischemia may correlate with primary spinal cord and a reduction in spinal intramedullary blood supply, potentially caused by the swelling of tissues surrounding the spinal intramedullary vessels. The advancement of imaging techniques is expected to enhance our ability to non-invasively visualize the spinal intramedullary arteries and veins in patients with spinal cord injury.

Neurological recovery is, to some extent, related to the severity of the original spinal cord injuries and the degree of ischemic neuronal damage, which is the original cascade of what is so called secondary spinal cord injury [14, 15]. In this study, all 21 patients were followed up for over 12 months. The neurological deficit, as classified by the ASIA impairment scale, showed improvement in only 2 ASIA B patients. In contrast, no neurological recovery was observed in 3 ASIA A patients. These findings suggest that the severity of the initial neurological injury is a determinant factor in the prognosis of neurological improvement in server spinal cord injury, even when there is blood supply to the ASA.

Although this is the first study to elucidate the incidence of VA occlusion and the occurrence of ASA occlusion in cervical facet dislocation, the main limitations of present study include the scope of the patient population and the absence of CTA and MRI performed during follow-up. Current and future advances in spinal imaging techniques for spinal intramedullary vessels are expected to exponentially increase our understanding of spinal cord ischemia.

Conclusion

The incidence of VA occlusion in cases of cervical facet dislocation was 24%. Despite this, no ASA occlusion was observed after cervical facet dislocation, even with unilateral VA occlusion. The results indicate that the ASA can maintain blood supply through ARAs from the contralateral VA and cervical ascending artery. Consequently, an occlusion affecting only one VA appears to be inadequate to disrupt the blood flow within the ASA. Furthermore, spinal cord ischemia may be correlated with the primary spinal cord injury and a reduction in spinal intramedullary blood supply, which can occur even in the absence of ASA occlusion.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Mei-Mei Yan, Jing-Jie Li, San-Rong Qiao and Li-Rong Yu for their contributions in data collection and validation. Thanks are also owed to Nan-Jun Mei, Ting-Ping Qian, and Hong-Wei Yan for their generous assistance.

Author contributions

ZZ: research design, data collection, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xinqiao Hospital of Army Medical University. The informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Giacobetti FB, Vaccaro AR, Bos-Giacobetti MA, Deeley DM, Albert TJ, Farmer JC, et al. Vertebral artery occlusion associated with cervical spine trauma. A prospective analysis. Spine. 1997;22:188–92. 10.1097/00007632-199701150-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taneichi H, Suda K, Kajino T, Kaneda K. Traumatically induced vertebral artery occlusion associated with cervical spine injuries: prospective study using magnetic resonance angiography. Spine. 2005;30:1955–62. 10.1097/01.brs.0000176186.64276.d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louw L, Steyl J, Loggenberg E. Imaging of Unilateral Meningo-ophthalmic Artery Anomaly in a Patient with Bilateral Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2014;4:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willis BK, Greiner F, Orrison WW, Benzel EC. The incidence of vertebral artery injury after midcervical spine fracture or subluxation. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:435–41. 10.1227/00006123-199403000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Wang H, Mu Z. Vertebral artery occlusion and recanalization after cervical facet dislocation. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:190–6. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Wang H, Zhou Y, Wang J. Computed tomographic angiography of anterior spinal artery in acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:442–7. 10.1038/sc.2012.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Even J, McCullough K, Braly B, Hohl J, Song Y, Lee J. et al. Clinical indications for arterial imaging in cervical trauma. Spine. 2012;37:286–91. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821b37b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaccaro AR, Klein GR, Flanders AE, Albert TJ, Balderston RA, Cotler JM. Long-term evaluation of vertebral artery injuries following cervical spine trauma using magnetic resonance angiography. Spine. 1998;23:789–94. 10.1097/00007632-199804010-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong M, Zhang Z. Is anterior spinal artery occluded in severe cervical spondylotic myelopathy? J Spinal Cord Med. 2021;44:765–69. 10.1080/10790268.2019.1693193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Wang H. Is the “snake-eye” MRI sign correlated to anterior spinal artery occlusion on CT angiography in cervical spondylotic myelopathy and amyotrophy? Eur Spine J. 2014;23:1541–7. 10.1007/s00586-014-3348-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turnbull IM, Brieg A, Hassler O. Blood supply of cervical spinal cord in man: a microangiographic cadaver study. J Neurosurg. 1966;24:951–65. 10.3171/jns.1966.24.6.0951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazorthes G, Gouaze´ A, Bastide G, Santini JJ, Zadeh O, Burdin P. Cervical spinal cord arterial vascularization: study of substitutions anastomoses [in French]. Rev Neurol. 1966;115:1055–68. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagi M, Ninomiya K, Kihara M, Horiuchi Y. Long-term surgical outcome and risk factors in patients with cervical myelopathy and a change in signal intensity of intramedullary spinal cord on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12:59–65. 10.3171/2009.5.SPINE08940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iseli E, Cavigelli A, Dietz V, Curt A. Prognosis and recovery in ischaemic and traumatic spinal cord injury: clinical and electrophysiological evaluation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:567–71. 10.1136/jnnp.67.5.567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waters RI. Functional prognosis of spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 1996;19:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.