Abstract

Introduction: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex condition that can have various symptoms and complications, one of which is infertility. Dysregulation of miRNA has been associated with the pathogenesis of numerous illnesses such as PCOS. In this study, we evaluated the effect of photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) and exosome therapy (EXO) on the regulation of miRNA and nucleus acetylation in a PCOS oocyte.

Methods: In this research, 36 oocytes divided into three groups: control, EXO, and PBM (Wavelength of 640 nm). Subsequently, in-vitro maturation (IVM) was evaluated. Real-time PCR was used to evaluate miRNA-21,16,19,24,30,106,155 and GAPDH. Afterward, oocyte glutathione (GSH) and nucleus acetylation were measured by H4K12.

Results: The expression of the miR-16, miRNA-19, miRNA-24, miRNA-106 and miRNA-155 genes in the EXO and PBMT groups was significantly down-regulated in comparison to the control group, but the expression of miRNA-21 and miR-30 significantly increased in the EXO and PBMT groups in comparison to the control group. The EXO and PBMT significantly increased GSH and nucleus acetylation (P<0.0001).

Conclusion: The results of this study showed that the use of EXO and PBMT can improve GSH and nucleus acetylation in the PCOS oocyte and also change the expression of miRNAs.

Keywords: Photobiomodulation therapy, Exosome therapy, miR-21, miR-155, PCOS

Introduction

Infertility is one of the most important issues related to people’s health, and recently the use of assisted reproduction techniques has increased in different countries. One of the causes of infertility is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS can have a hormonal imbalances contribute to the characteristic symptoms observed in affected individuals, such as irregular menstrual cycles, hirsutism, acne, and infertility.1 Current studies have displayed that miRNAs play an essential role in the progress of PCOS, including inflammation, and ovarian function. miRNAs prevent their translation into proteins.2 The dysregulation of miRNAs has been associated with many diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and metabolic syndromes. In the context of PCOS, studies have shown altered expression patterns of specific miRNAs in ovarian tissues and circulating blood samples from affected individuals. These findings suggest that miRNAs may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of PCOS.3 miRNAs that have been found to be differentially expressed in ovarian tissues or circulating blood samples from women with PCOS compared to healthy controls. Potential functional roles of miRNAs in modulating key pathways are involved in PCOS pathophysiology. Some studies have investigated the utility of specific miRNAs as diagnostic tools for PCOS and evaluated their sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional diagnostic methods.4-6 miRNA-21 is a microRNA that has been found to play a role in the development of PCOS. Studies have shown that miRNA-21 is up-regulated in the ovaries of women with PCOS. This means that there are higher levels of miR-21 present in these women compared to women without PCOS.7,8 miRNA-21 has been found to regulate several genes involved in ovarian function, including those involved in follicle development and steroidogenesis.9 This suggests that targeting miRNA-21 could be a potential therapeutic strategy for treating PCOS.10-12 Furthermore, miRNA-155 may contribute to the development of PCOS by disrupting normal ovarian function.13,14 In addition to its role in ovarian function, miRNA-155 has also been implicated in inflammation and insulin resistance, two other key features of PCOS. miRNA-155 can promote inflammation and insulin resistance in various tissues throughout the body.15 Various treatments have been used to treat infertility caused by PCOS, but none of them has been able to completely cure it. Exosome (EXO) is a relatively new and promising approach in the field of regenerative medicine. EXOs are small vesicles that are naturally released by cells, containing various molecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and growth factors. While there is ongoing research on the potential use of EXO for various conditions, including PCOS, it is important to note that this field is still in its early stages. Some preclinical studies have shown promising results in using EXOs derived from mesenchymal stem cells to improve ovarian function and hormone regulation in animal models of PCOS. These studies suggest that EXO may have the potential to modulate inflammation, promote tissue repair, and restore hormonal balance in PCOS.16 Also, photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) has been studied and used for various medical conditions, and its effectiveness in treating PCOS is still being researched. Although PBMT has shown promise in improving hormonal imbalances and promoting follicular development in some studies, more research is needed to establish its efficacy, particularly for PCOS.17 In this study, we evaluated the effect of PBMT and EXO on the regulation of miRNA and nucleus acetylation in the PCOS oocyte. Additionally, we delved into the molecular mechanisms through which miRNAs regulate gene expression and discussed their potential as diagnostic markers or therapeutic targets for PCOS.

Materials and Methods

The Ethics Committee at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, accepted the in vitro study (IR.SBMU.LASER.REC.1402.027). Donors approved vocally and in writing to donate oocytes to the research. Patients from the Genetics and In Vitro Assisted Reproductive Center at Erfan Niyaish Hospital (Tehran, Iran) gave oocytes for the current study between 2022 and 2023. The present study involved GV oocytes from 20 intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) techniques.16

Ovarian Stimulation

In PCOS cases, a woman receives mild ovarian stimulation (hormones gonadotropin GnRH agonist (Superfact, Aventis Pharma, Germany) and rFSH (Gonal-F, Merck Serono, Germany) for five days) to encourage the growth and development of multiple follicles containing immature oocytes. This step is optional and depends on the individual’s circumstances.

Oocyte Retrieval

Once the follicles have reached an appropriate size (follicles reached > 18 mm, 10 000 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Ovitrelle, Merck Serono Europe; Pregnyl, Organon)), oocyte retrieval is performed under ultrasound guidance. A needle is inserted into each follicle, and the fluid containing the immature oocytes is aspirated. Subsequently, oocytes are collected from the patients 36-40 hours after hCG management via the trans-vaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval technique.

Oocyte Preparation

The retrieved oocytes are then isolated from the surrounding fluid and any cumulus cells (cells that surround and support the oocyte). This step allows for better visualization and manipulation of individual oocytes during maturation.

In Vitro Maturation

The isolated oocytes are placed in a culture medium that contains essential nutrients, growth factors, and hormones necessary for their maturation 40 μL drops in a culture medium (Global R, Life Global) for 60 minutes in the control group. Oocytes from the EXO group are moved to droplets of EXO suspended in mineral oil (Life Global), and in PBMT group oocyte under the continuous He-Ne laser irradiance of 0.032 W/cm2, wavelength of 640 nm, laser beam area of 0.79 cm2, average power output of 9.5 mW, 1.85 J/cm2 and incubated at 37°C in a 6% CO2. The culture medium is carefully controlled to mimic the conditions found inside a woman’s body.16

Monitoring and Evaluation

During the maturation period, which typically lasts around 24-48 hours, the oocytes are monitored closely to assess their development. This may involve checking for the signs of nuclear maturation (changes in chromatin structure) or cytoplasmic maturation (changes in organelle distribution).

EXO Extraction and Conformation

The cord blood plasma extraction and collection protocol involves the following steps:

Collection of cord blood: The process begins with the collection of cord blood from the umbilical cord and placenta immediately after the baby is born. This is typically done by a healthcare professional using a sterile collection kit.

Processing of cord blood: Once collected, the cord blood is processed to separate the plasma from the other components such as red blood cells and white blood cells. This can be done by using a centrifuge, which spins the blood at high speeds to separate the different components.

Extraction of plasma: After processing, the plasma is extracted from the rest of the components and collected in a separate container. This can be done by using specialized equipment designed for plasma extraction.

Storage of cord blood plasma: The collected plasma is then stored in a sterile container or bag, typically at low temperatures to preserve its quality. It may be stored in a cord blood bank for future use.16

After separating the plasma from the umbilical Cord blood, the plasma is ultracentrifuged (4000g, 20 000g, 100 000g sequentially) to separate the EXO. The EXO is confirmed by DLS, EM and flow cytometry (CD9, CD81).

Scanning Electron Microscope

The process of identifying EXO involves the use of a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Initially, EXO are extracted and then fixed with 3.7% glutaraldehyde for 15 minutes. Following fixation, the samples are washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently rinsed with ethanol. They are then placed on a glass substrate and dried at 25 degrees Celsius before being analyzed with an SEM.18

Dynamic Light Scattering

In this study, dynamic light scattering (DLS) is utilized to measure the diameter of EXOs using a ZetaSizer from Malvern Instruments. The analysis is performed in a solvent volume of 166 μL, employing specific radiation and light scattering techniques. The solvent of choice is a phosphate buffer with a refractive index of 1.33 and a viscosity of 1.64 cP. These parameters are essential for the device’s software to analyze the results accurately. DLS is a non-destructive and rapid method for determining particle sizes ranging from several nanometers to microns. To prepare the samples, EXOs are diluted once before being measured and analyzed using the Zetasizer APS (MALVERN https://www.internano.org).

Real-time RT-PCR Analysis

Real-time PCR was used to examine the expression of miRNA-21, miRNA-16, miRNA- 19, miRNA- 24, miRNA-30, miRNA- 106, miRNA-155, and GAPDH genes in different groups. To extract RNA (RNA extraction kit, Fermentas, USA), MII oocytes were first washed in a drop of PBS, and with the help of an oral pipette, the smallest volume removed from PBS (approximately 0.5 µL) was placed into a microtube with a volume of 0.2 mL containing 5.0 µL. This point was considered so that the total volume of oocyte and cell lysis buffer does not exceed 2 µL. After transferring the microtubes to ice, 2 µL of poly N and 5 µL of water were added to it and they were placed in a thermal cycler at 75 °C for 5 minutes. After this time, the microtubes were placed in an ice container, and x5 RT Buffer, 200 IU of Enzyme RT, 10 µM of dNTP, and 10 IU of RNase inhibitor were added to them (total volume 20 µL) and placed in the Thermal Cycler.19

Real-Time PCR Setup

We set up the real-time PCR reaction by combining the extracted cDNA samples with the master mix (Amplicon, Denmark), and forward and reverse primers (Table 1). We included appropriate positive and negative controls. Subsequently, we set up appropriate cycling parameters (for 5 minutes at 94 °C, 30 seconds at 60 °C, 45 seconds at 72 °C, for 40 extension cycles) for the specific real-time PCR instrument, including denaturation temperature, annealing temperature, and extension temperature/time.

Table 1. Primer Sequences .

| ID | Gene Name | 5’-3’ | Annealing Temperature (°C) | PCR Length |

| MIMAT0000069 | miRNA -16 | AGCAGCACGTAAATATTC GAACATGTCTGCGTATCG |

60 | 190 |

| MIMAT0004490 | miRNA -19 | GTTTTGCATAGTTGCACGC ACATGTCTGCGTATCTCAT |

61 | 185 |

| MIMAT0000079 | miRNA -24 | GCCTACTGAGCTGATACG ACATGTCTGCGTATCTCGA |

62 | 190 |

| MIMAT0000244 | miRNA -30 | ACATCCTACACTCTCACG GAACATGTCTGCGTATCG |

58 | 205 |

| MIMAT0000386 | miRNA -106 | AAAGTGCTGACAGTGCG CATGTCTGCGTATCTCG |

59 | 180 |

| NM_001256799.2 | GAPDH | CCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGA TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGC |

60 | 145 |

| NR_029738.1 | miRNA - 21 | TTCGTATCCAGTGCAGC CGCGCACTGGATACGAT |

59 | 150 |

| MIMAT0000646 | miRNA - 155 | TGCTAATCGTGATAGCC GAACATGTCTGCGTATTC |

61 | 210 |

Glutathione Assay

The level of reduced GSH was measured by Elman’s technique. In order to determine the amount of glutathione peroxidase enzyme, ZellBio (ZB-GPX96) kits were used according to the protocol and the hydrogen peroxide substrate included in the kit. In order to measure the amount of glutathione peroxidase, 10 µL of oocyte culture medium were used, and after adding the solutions to the kit, its absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 412 nm.20

H4K12 Assay

The EpiQuikTM Global Acetyl Histone H4-K12 Quantification Kit (Colorimetric) in oocytes is a kit used to study the histone modification of lysine 12 on histone H4 in oocytes. This assay involves isolating oocytes and then analyzing the levels of histone H4 lysine 12 acetylation. The H4K12 assay typically involves such techniques as chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by quantitative PCR or western blotting to quantify the levels of histone H4 lysine 12 acetylation. These techniques can determine how this specific histone modification changes during different stages of oocyte development or in response to various stimuli.21

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by using SPSS version 27 software. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. Group comparisons were conducted by using one-way ANOVA analysis, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Results

EXO Confirmation

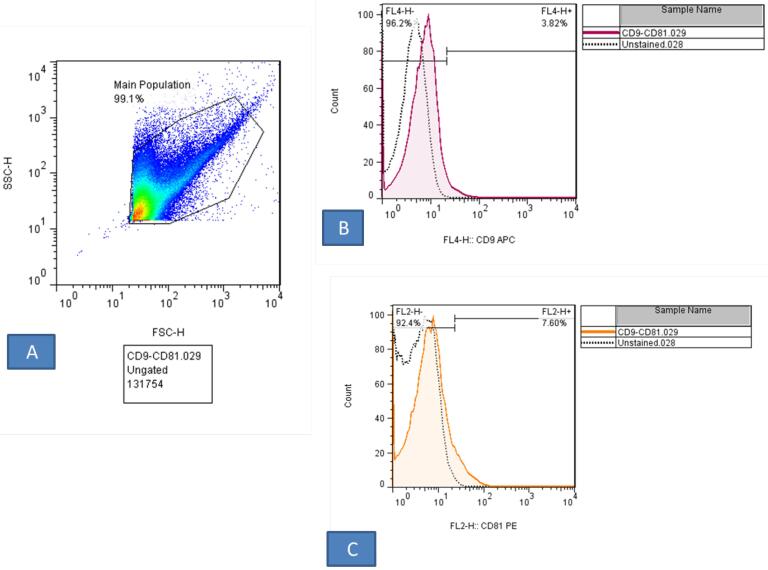

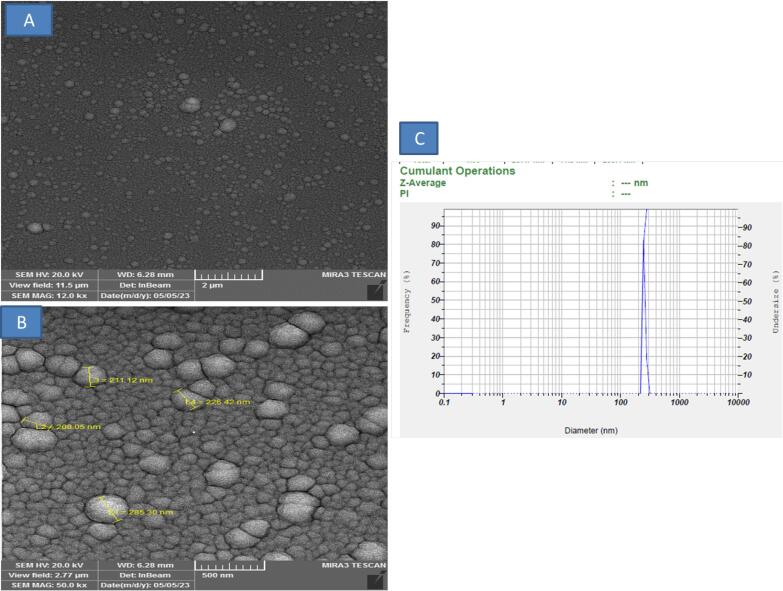

The data of flow cytometry assay can provide evidence about the physical and chemical individualities of CD marker in an EXO. Flow cytometry analysis showed that CD9, and CD81expressed in the EXO (Figure 1). Next, the density and size of the EXO derived and purified were examined by DLS and SEM methods. The results in Figure 2A,B showed that the shape of EXO, we observe the EXO derived cord blood plasma had a spherical appearance in SEM analysis. On the other hand, in the DLS result, it was found that the highest concentration of the EXO was derived from the cord blood plasma, and the average size of the particles was in the range of 200-250 nm (Figure 2C).

Figure 1.

Flow Cytometry Analysis. The result showed that the EXO derived cord blood plasma express the CD marker 9 (96.2%), 81(92.4%)

Figure 2.

DLS and SEM Analysis. We observed the EXO derived cord blood plasma with an SEM, which had a spherical appearance (A, B) and we were also able to obtain the size of the particles using DLS, and the average size of the particles was in the range of 200-250 nm (C)

Effects of PBMT and EXO Treatment in Oocyte Maturation

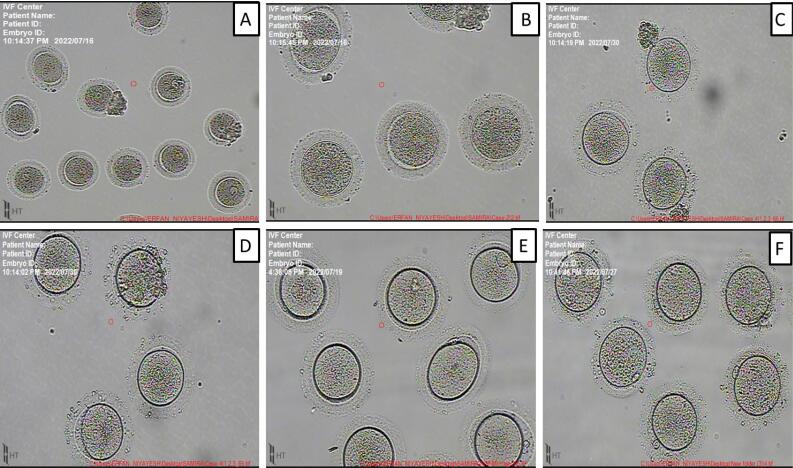

After oocyte retrieval by vaginal surgery, the condition of the oocytes of the studied patients was evaluated. The maturation status of GV oocytes under in-vitro maturation (IVM) was evaluated after 24-28 hours of cultivation. The results showed that the MII oocyte level in the EXO and PBMT groups was higher compared to the control group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Results of the Treatment of the PCOS Oocyte (A, B, C) With Normal Medium, EXO and PBMT, Receptively (D, E, F). The results showed that EXO and PBMT can improve the maturation rate in the oocyte in the in vitro model

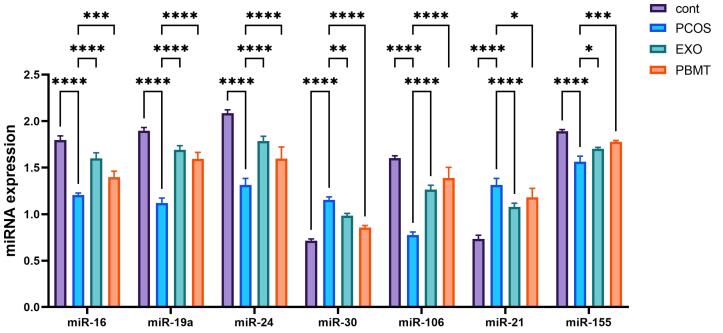

Effects of EXO and PBMT Treatment on miRNA-Related Gene Expression

In the present study, the expression level of genes related to oocyte maturation was evaluated by RT-qPCR. The result of RT-qPCR showed that the expression of miR-16, miR-19, miR-24, miR-30, miR-106, miR-21, miR-155 changed in the PCOS oocyte, and the expression of the miR-16, miR-19, miR-24, miR-106 and miR-155 genes was significantly up-regulated after treatment with EXO and PBMT in comparison with the PCOS group, but the expression of miR-21 and miR-30 significantly down-regulated in the EXO and PBMT groups in comparison with the PCOS group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The Results of the Effect of EXO and PBMT on the Expression of miR-16, miR-19, miR-24, miR-30, miR-106, miR-21, miR-155 Genes. The results showed that EXO and PBMT can have an effect on miR-16, miR-19, miR-24, miR-30, miR-106, miR-21, miR-155 gene expression, and these changes are significant

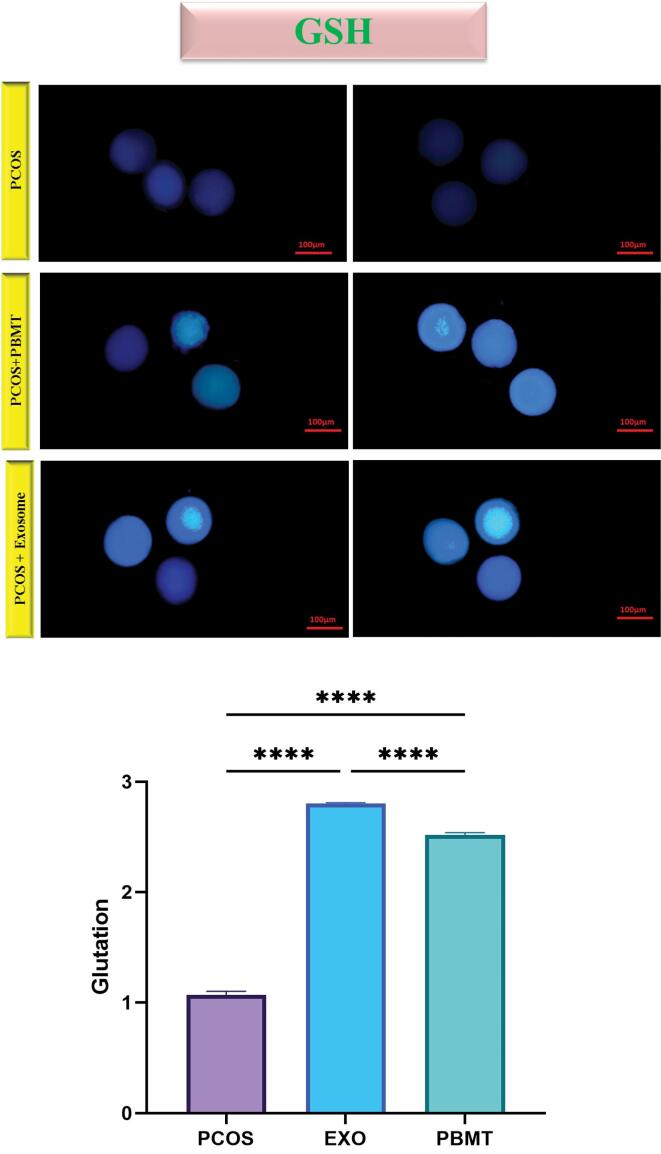

Effects of EXO and PBMT Treatment on GSH Content

The amount of GSH in the cytoplasm was checked in oocytes with fluorescent staining (GSH content). The findings of this research showed that the induction of meiosis by EXO and PBMT causes a significant increase in the amount of cytoplasmic GSH in the PCOS oocyte. The results showed that EXO and PBMT treatment made a significant increase in oocyte GSH concentration (P < 0.0001; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Fluorescent Staining of PCOS Oocytes Matured In Vitro. A statistically significant difference was observed in the amount of glutathione in the cytoplasm in the PCOS and intervention groups. The results showed that EXO and PBMT can cause an increase in GSH. These changes are significant. The data are shown as mean ± SD (**** P < 0.0001)

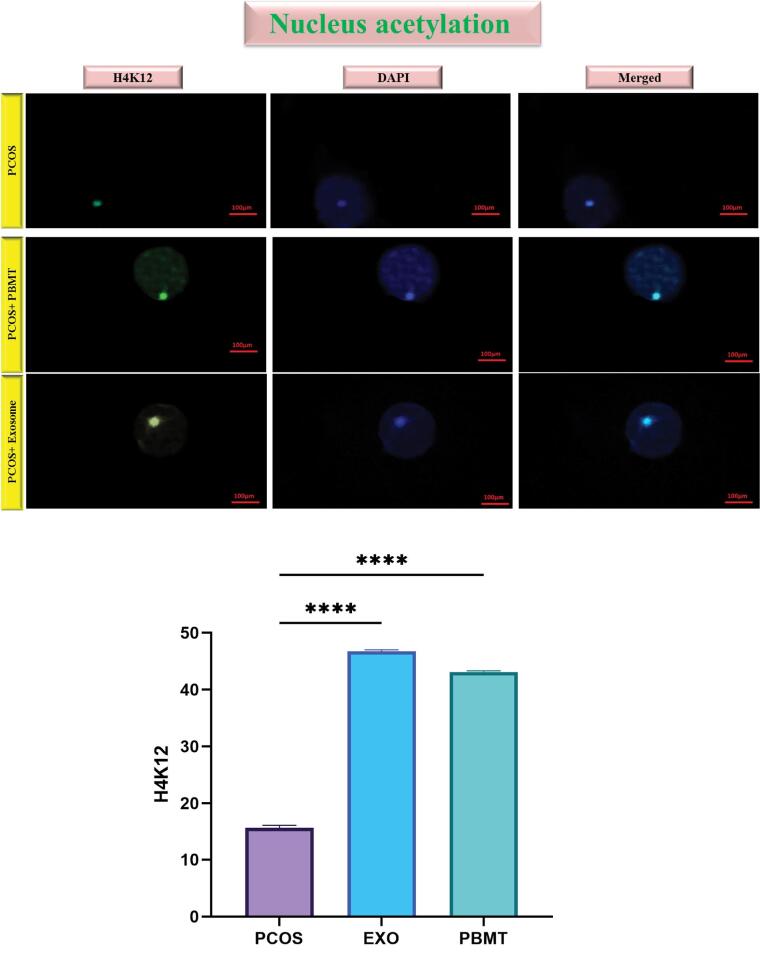

Effects of EXO Treatment in Nucleus Acetylation

The H4K12 was assessed in the EXO, PBMT and PCOS groups. Results showed that EXO and PBMT treatment made a significant increase in nucleus acetylation (P < 0.0001; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The Results of the Effect of EXO and PBMT on Nucleus Acetylation. The results showed that EXO and PBMT can cause an increase in H4K12. These changes are significant. The data are shown as mean ± SD (**** P < 0.0001)

Discussion

The results of this study showed that PBMT and EXO can improve the cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation of the PCOS oocyte and also increase the amount of GSH and acetylation, and they can change the expression level of miRNA. Furthermore, the induction of meiosis by EXO and PBMT during IVM leads to a significant increase in the nuclear maturation rate of the oocyte and the exit of the first polar body compared to the control group. The progression of meiosis in the oocyte involves signaling pathways that are carried out by the phosphorylation of proteins that are regulated by cyclin dependent kinase holoenzyme (CDKs). The level of maturation promoting factor (MPF) activity depends on the availability of cyclin B and the phosphorylation status of CDK1. On the other hand, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signaling pathway plays a role in the oocyte maturation process. Studies have shown that MAPK is inactive in the human oocyte at the GV stage; moreover, it reaches its highest level at MII, and its activity is after the formation of pronuclei. It decreases based on the evidence that the MAPK signaling pathway regulates the level of MPF activity, and studies have shown that MAPK inhibitors lead to the inhibition of germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) in the oocyte.22,23 A study conducted by Zhang et al in 2011 showed that although the inhibition of MAPK activity in pig cumulus-oocyte complexes does not affect oocyte nuclear maturation, the inhibition of MPF activity inhibits oocyte meiosis. It can be concluded that MAPK activity is necessary mainly in the early stages of oocyte maturation, but MPF plays an essential role in maintaining the oocyte in the metaphase II (MII) stage23 MPF activity in the mature oocyte is important for chromosome condensation and the formation of male and female pronuclei, and these MPF activities are carried out by CDK1 catalytic and cyclin B regulatory subunits.24

Oxidative stress in the oocyte is usually determined by the level of ROS and GSH. In the conditions of oxidative stress, ROS causes cell damage through several mechanisms such as lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage to proteins and DNA.25 Free radicals and oxidative stress are important factors in the reproductive system, including oocytes and embryos. Oxidative stress causes a decrease in oocyte calcium reserve, which in turn is associated with a disturbance in oocyte activation.26 The findings of the present study showed that the induction of meiosis with EXO and PBMT leads to an increase in the level of GSH in the oocyte cytoplasm. GSH is a free intracellular thiol that acts as a non-enzymatic antioxidant in the oocyte.27 The synthesis of GSH in the oocyte starts at the time of GVBD and reaches its highest level in the MII stage. In addition, GSH level in oocytes is a good marker for cytoplasmic maturation of the oocyte after IVM.28 GSH protects bovine oocytes against oxidative stress damage by reducing ROS production in mitochondrial metabolism.29 GSH controls many processes in the oocyte, including regulating the intracellular redox balance and defending the oocyte against damage caused by ROS, affecting the decondensation of the sperm nucleus after fertilization and the formation of the male pronucleus, the synthesis of DNA and amino acids, and the transfer of protein to the oocyte.30 The results of our study showed that the level of expression of miRNAs in the PCOS oocyte undergoes many changes. Recent studies have shown that miRNAs play an important role in the development of PCOS, including the regulation of insulin resistance, inflammation, and ovarian function.13 Among these miRNAs, the miR-17-92 cluster and miR-21 have been found to be dysregulated in PCOS patients. miR-17-92 cluster increases in the granulosa cells of PCOS patients, which may contribute to the development of follicular cysts.31 Additionally, the miR-17-92 cluster has been shown to regulate insulin signaling in the liver and adipose tissue, which may contribute to insulin resistance in PCOS patients. miR-21 is another miRNA that has been implicated in the development of PCOS.32 Studies have shown that the expression of miR-21 increases in the serum and granulosa cells of PCOS patients. Additionally, miR-21 has been shown to regulate the expression of genes involved in the insulin signaling pathway, which may contribute to insulin resistance in PCOS patients.31,33 The dysregulation of miR-17-92 and miR-21 in PCOS patients may contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease.34 Recently, there has been a surge in research focusing on the role of miRNAs in cellular senescence. Cellular senescence marked by a halt in cell division is increasingly recognized for its role in addressing various human diseases. The main action of these senescent cells is linked to their senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which can lead to chronic inflammation in tissues and organs due to autocrine and paracrine effects. This inflammation and the factors released by senescent cells can worsen the cellular environment, increasing the risk of cancer and other age-related diseases. These miRNAs, which are crucial in regulating gene expression post-transcription, display unique patterns of expression in senescent cells. They have the ability to influence the SASP by affecting various aspects of the senescence signaling pathway, including the function of telomerase, the production of reactive oxygen species, and mitochondrial damage. Studies have shown that the removal of senescent cells generally does not lead to significant adverse effects, paving the way for new treatments targeting these cells.35 Overall, EXO and PBMT may be an effective intervention for improving oocyte maturation and hormonal parameters associated with PCOS. However, further research is needed to evaluate its efficacy in other clinical outcomes such as metabolic and reproductive parameters as well as its safety profile over longer periods of time before it can be recommended as a standard treatment option for women with PCOS. EXO is a relatively new and promising treatment option for various medical conditions, including PCOS. In the case of PCOS, EXO could potentially help regulate hormone levels and reduce inflammation in the ovaries.16 This could lead to improved ovarian function and fertility for women with PCOS. However, it is important to note that EXO is still in the early stages of research and development. EXO has been associated with significant improvements in hormonal parameters compared to placebo/standard care control groups.36

Conclusion

EXO and PBMT represent an exciting avenue for addressing the underlying mechanisms of PCOS. By targeting hormonal imbalances, inflammation, insulin resistance, and ovarian regeneration, EXO and PBMT have the potential to revolutionize PCOS treatment. With continued advancements in EXO and PBMT research, we may witness a significant breakthrough in the management of PCOS.

Acknowledgments

This study is based on a PhD dissertation by Samira Sahraeian at the Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran. This work was financially supported by Laser Application in Medical Sciences Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Samira Sahraeian.

Data curation: Samira Sahraeian, Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Mohammad Amin Edalatmanesh.

Formal analysis: Mohammad Amin Edalatmanesh, Robabeh Taheripanah, Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh.

Funding acquisition: Samira Sahraeian, Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh.

Investigation: Samira Sahraeian, Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Somayeh Keshavarzi, Alaleh Ghazifard

Methodology: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Mohammad Amin Edalatmanesh, Somayeh Keshavarzi, Alaleh Ghazifard.

Project administration: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh.

Resources: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Robabeh Taheripanah.

Software: Samira Sahraeian, Mohammad Amin Edalatmanesh.

Supervision: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh.

Validation: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Robabeh Taheripanah, Mohammad Amin Edalatmanesh.

Visualization: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh, Robabeh Taheripanah.

Writing–original draft: Samira Sahraeian, Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh.

Writing–review & editing: Hojjat Allah Abbaszadeh.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, under code No (IR.SBMU.LASER.REC.1402.027).

Funding

This work was financially supported by Laser Application in Medical Sciences Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Please cite this article as follows: Sahraeian S, Abbaszadeh HA, Taheripanah R, Edalatmanesh MA, Keshavarzi S, Ghazifard A. Exosome therapy and photobiomodulation therapy regulate mi-RNA 21, 155 expressions, nucleus acetylation and glutathione in a polycystic ovary oocyte: an in vitro study. J Lasers Med Sci. 2024;15:e10. doi:10.34172/jlms.2024.10.

References

- 1.Rodrigues P, Marques M, Manero JA, Marujo MD, Carvalho MJ, Plancha CE. In vitro maturation of oocytes as a laboratory approach to polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS): from oocyte to embryo. WIREs Mech Dis. 2023;15(3):e1600. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Udesen PB, Sørensen AE, Svendsen R, Frisk NLS, Hess AL, Aziz M, et al. Circulating miRNAs in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal cohort study. Cells. 2023;12(7):983. doi: 10.3390/cells12070983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topkaraoğlu S, Hekimoğlu G. Abnormal expression of miRNA in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Med Res Rep. 2023;6(3):183–91. doi: 10.55517/mrr.1324616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan E, Butler AE, Drage DS, Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL. Serum polychlorinated biphenyl levels and circulating miRNAs in non-obese women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023;14:1233484. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1233484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajabi M, Kalantar SM, Mojodi E, Salehi M, Dehghani Firouzabadi R, Etemadifar SM, et al. Assessment of circulating miRNA-218, miRNA-222, and miRNA-146 as biomarkers of polycystic ovary syndrome in epileptic patients receiving valproic acid. Biomed Res Ther. 2023;10(9):5884–95. doi: 10.15419/bmrat.v10i9.833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Tan C, Zhang J, Yi G, Wang B, et al. The long non-coding RNA BBOX1 antisense RNA 1 is upregulated in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and suppresses the role of microRNA-19b in the proliferation of ovarian granulose cells: short title: BBOX1 antisense RNA 1 in cell proliferation. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):508. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02632-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang L, Li W, Wu M, Cao S. Ciculating miRNA-21 as a biomarker predicts polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in patients. Clin Lab. 2015;61(8):1009–15. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.150122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naji M, Aleyasin A, Nekoonam S, Arefian E, Mahdian R, Amidi F. Differential expression of miR-93 and miR-21 in granulosa cells and follicular fluid of polycystic ovary syndrome associating with different phenotypes. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14671. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldakheel FM, Abuderman AA, Alduraywish SA, Xiao Y, Guo WW. MicroRNA-21 inhibits ovarian granulosa cell proliferation by targeting SNHG7 in premature ovarian failure with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Reprod Immunol. 2021;146:103328. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen B, Xu P, Wang J, Zhang C. The role of miRNA in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Gene. 2019;706:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.04.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, He H, Long B, Wei B, Yang P, Huang X, et al. Acupuncture regulates the apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells in polycystic ovarian syndrome-related abnormal follicular development through LncMEG3-mediated inhibition of miR-21-3p. Biol Res. 2023;56(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s40659-023-00441-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Nardo Maffazioli G, Baracat EC, Soares JM, Carvalho KC, Maciel GA. Evaluation of circulating microRNA profiles in Brazilian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a preliminary study. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0275031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huo Y, Ji S, Yang H, Wu W, Yu L, Ren Y, et al. Differential expression of microRNA in the serum of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome with insulin resistance. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10(14):762. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arancio W, Calogero Amato M, Magliozzo M, Pizzolanti G, Vesco R, Giordano C. Serum miRNAs in women affected by hyperandrogenic polycystic ovary syndrome: the potential role of miR-155 as a biomarker for monitoring the estroprogestinic treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(8):704–8. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1428299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia H, Zhao Y. miR-155 is high-expressed in polycystic ovarian syndrome and promotes cell proliferation and migration through targeting PDCD4 in KGN cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2020;48(1):197–205. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1699826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahraeian S, Abbaszadeh HA, Taheripanah R, Edalatmanesh MA. Extracellular vesicle-derived cord blood plasma and photobiomodulation therapy down-regulated caspase 3, LC3 and Beclin 1 markers in the PCOS oocyte: An In Vitro Study. J Lasers Med Sci. 2023;14:e23. doi: 10.34172/jlms.2023.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polat B, Okur DT, Çolak A, Yilmaz K, Özkaraca M, Çomakli S. The effects of low-level laser therapy on polycystic ovarian syndrome in rats: three different dosages. Lasers Med Sci. 2023;38(1):177. doi: 10.1007/s10103-023-03847-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niknazar S, Abbaszadeh HA, Peyvandi H, Rezaei O, Forooghirad H, Khoshsirat S, et al. Protective effect of [Pyr1]-apelin-13 on oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in hair cell-like cells derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;853:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darabi S, Tiraihi T, Ruintan A, Abbaszadeh HA, Delshad A, Taheri T. Polarized neural stem cells derived from adult bone marrow stromal cells develop a rosette-like structure. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2013;49(8):638–52. doi: 10.1007/s11626-013-9628-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moghimi N, Eslami Farsani B, Ghadipasha M, Mahmoudiasl GR, Piryaei A, Aliaghaei A, et al. COVID-19 disrupts spermatogenesis through the oxidative stress pathway following induction of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2021;26(7-8):415–30. doi: 10.1007/s10495-021-01680-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou BO, Wang SS, Zhang Y, Fu XH, Dang W, Lenzmeier BA, et al. Histone H4 lysine 12 acetylation regulates telomeric heterochromatin plasticity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(1):e1001272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt A, Nebreda AR. Signalling pathways in oocyte meiotic maturation. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 12):2457–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.12.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang DX, Park WJ, Sun SC, Xu YN, Li YH, Cui XS, et al. Regulation of maternal gene expression by MEK/MAPK and MPF signaling in porcine oocytes during in vitro meiotic maturation. J Reprod Dev. 2011;57(1):49–56. doi: 10.1262/jrd.10-087h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villa-Diaz LG, Miyano T. Activation of p38 MAPK during porcine oocyte maturation. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(2):691–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.026310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou C, Zhang X, Chen Y, Liu X, Sun Y, Xiong B. Glutathione alleviates the cadmium exposure-caused porcine oocyte meiotic defects via eliminating the excessive ROS. Environ Pollut. 2019;255(Pt 1):113194. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kala M, Shaikh MV, Nivsarkar M. Equilibrium between anti-oxidants and reactive oxygen species: a requisite for oocyte development and maturation. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16(1):28–35. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morado SA, Cetica PD, Beconi MT, Dalvit GC. Reactive oxygen species in bovine oocyte maturation in vitro. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21(4):608–14. doi: 10.1071/rd08198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Matos DG, Gasparrini B, Pasqualini SR, Thompson JG. Effect of glutathione synthesis stimulation during in vitro maturation of ovine oocytes on embryo development and intracellular peroxide content. Theriogenology. 2002;57(5):1443–51. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(02)00643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Q, Zhang X, Yang X. Glutathione mitigates meiotic defects in porcine oocytes exposed to beta-cypermethrin by regulating ROS levels. Toxicology. 2023;494:153592. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2023.153592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahrami M, Morris MB, Day ML. Glutamine, proline, and isoleucine support maturation and fertilisation of bovine oocytes. Theriogenology. 2023;201:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2023.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Konstantinidou F, Placidi M, Di Emidio G, Stuppia L, Tatone C, Gatta V, et al. Maternal microRNA profile changes when LH is added to the ovarian stimulation protocol: a pilot study. Epigenomes 2023;7(4). 10.3390/epigenomes7040025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32. Khoshandam M, Naserpour L, Soltaninejad H, Zare-Zardini H, Hoseiny AA, Golpar Raboki N, et al. The role of microRNAs in female and male human reproduction: a narrative review. Authorea [Preprints]. September 30, 2023. Available from: https://www.authorea.com/doi/full/10.22541/au.169609839.97787658/v1.

- 33.Udesen PB, Sørensen AE, Svendsen R, Frisk NLS, Hess AL, Aziz M, et al. Circulating miRNAs in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal cohort study. Cells. 2023;12(7):983. doi: 10.3390/cells12070983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng X, Ning Z, Li L, Cui Z, Du X, Amevor FK, et al. High expression of miR-22-3p in chicken hierarchical follicles promotes granulosa cell proliferation, steroidogenesis, and lipid metabolism via PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(Pt 7):127415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, Gao J, Xu C. Tackling cellular senescence by targeting miRNAs. Biogerontology. 2022;23(4):387–400. doi: 10.1007/s10522-022-09972-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Y, Tao M, Wei M, Du S, Wang H, Wang X. Mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomal miR-323-3p promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of cumulus cells in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):3804–13. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1669619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]