Abstract

Telomerase, the enzyme that maintains telomeres at natural chromosome ends, should be repressed at double-strand breaks (DSBs), where neotelomere formation can cause terminal truncations. We developed an assay to detect neotelomere formation at Cas9- or I-SceI-induced DSBs in human cells. Telomerase added telomeric repeats to DSBs, leading to interstitial telomeric repeat insertions or formation of functional neotelomeres accompanied by terminal deletions. The threat telomerase poses to genome integrity was minimized by ATR kinase signaling, which inhibited telomerase at resected DSBs. In addition to acting at resected DSBs, telomerase used the extruded strand in the Cas9 enzyme-product complex as a primer for neotelomere formation. We propose that while neotelomere formation is detrimental in normal human cells, it may allow cancer cells to escape from breakage-fusion-bridge cycles.

One-Sentence Summary:

Human telomerase threatens genome integrity by adding telomeres to broken chromosomes and is held in check by ATR signaling.

Telomeres define and protect the ends of linear chromosomes. Genome stability requires that telomeres evade recognition as double-strand breaks (DSBs), which is accomplished by the protective shelterin complex (1). Telomeric DNA is maintained by telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein complex whose reverse transcriptase component (human telomerase reverse transcriptase, hTERT) uses a short template region in its RNA component (human telomerase RNA, hTR) to add TTAGGG repeats to the telomeric single-stranded (ss) 3’ overhang (2). Just as telomeres must not be recognized as sites of DNA damage, telomerase must not convert DSBs into telomeres. If telomerase creates a functional telomere at a DSB, genes distal to the break may be lost. Human telomerase is expected to preferentially act at telomeres, to which it is recruited by the TPP1 subunit of shelterin and where its hTR template can base-pair with the 3’ telomeric overhang ((3), reviewed in (4)).

However, hints that telomerase might act at DSBs came initially from Barbara McClintock’s work on dicentric chromosomes in maize (5, 6), which undergo breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) cycles in somatic cells until the broken chromosomes gain functional telomeres in the embryo. Writing to Elizabeth Blackburn, McClintock described a maize mutant in which this healing never occurred, prophetically surmising that “this mutant affects the production or the action of an enzyme required for formation of new telomeres” (7). In humans, the first case of apparent neotelomere formation was identified in an α-thalassemia patient with a truncation of chromosome 16p, where telomeric repeats were added directly to a non-telomeric breakpoint sequence (referred to here as telomerase substrate, TS) (8). Additional putative germline neotelomere formation events did not reveal sequence motifs common to the breakpoints (fig. S1), and the role of telomerase in neotelomere formation has not been established.

Results

Telomerase-mediated TTAGGG repeat addition at Cas9-induced DSBs

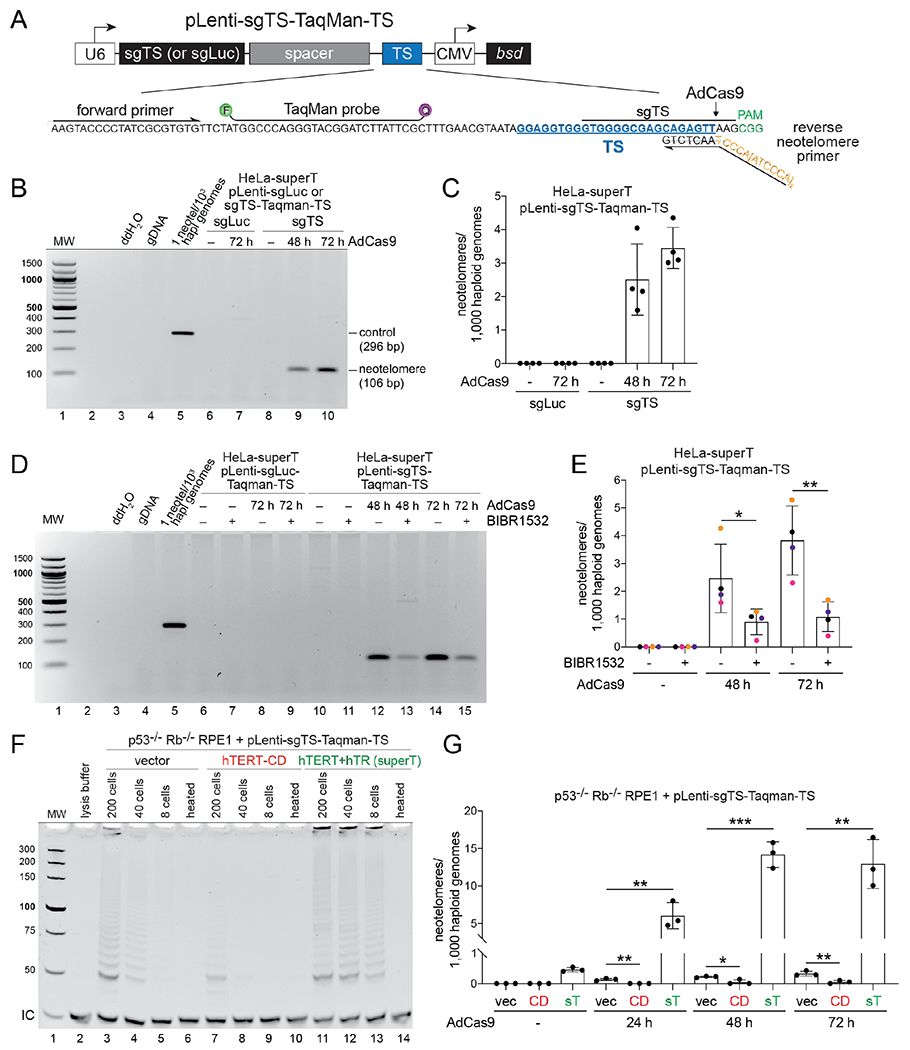

As TS is a proficient primer for telomerase in vitro (9), we used it to determine whether human telomerase adds telomeric DNA to Cas9-induced DSBs. We generated a lentiviral vector (pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS) containing TS flanked by a PAM and expressing a TS sgRNA that directs Cas9 to cut at the 3’ end of TS (Fig. 1A and fig. S2A). TTAGGG repeat addition at TS was detected by PCR using a reverse primer designed to span the 3’ end of TS and the added TTAGGG repeats, assuming that repeat addition occurred in the frame observed in the α-thalassemia patient (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). Based on qPCR with a TaqMan probe, infected HeLa cells contained ~1.7 copies of pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS per haploid genome (fig. S2B). Infection with Cas9 adenovirus (AdCas9, fig. S2C) resulted in cleavage of a subset of the TS sites, as evidenced by the T7 endonuclease I detection assay, which monitors indels resulting from DSB repair (fig. S2D). The TaqMan qPCR assay was linear over a range of 10−4 to 10 neotelomere formation events per haploid genome (fig. S2E). In “super-telomerase” (superT) HeLa cells, in which overexpression of both hTR and hTERT increases telomerase activity by ~20-fold (10), neotelomere products were detected within 48 h of AdCas9 infection, but not in luciferase sgRNA control cells (Fig. 1B). At 72 h after AdCas9 infection, the cells contained 3 to 4 neotelomeres per 1,000 haploid genomes (Fig. 1C). By contrast, TTAGGG repeat addition events at TS were 10-fold less frequent when Cas9 cutting was directed ~60 bp 3’ to TS (fig. S2F–H).

Fig. 1. Telomerase adds telomeric repeats to Cas9-induced DSBs.

(A) Schematic of pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS. U6, human U6 promoter; sgLuc or sgTS, singleguide RNA (sgRNA) cassette; TS, PCR cassette containing the truncation sequence (TS); CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter; bsd, blasticidin S deaminase gene. The inset shows the sequence of TS PCR cassette, with the primers, TaqMan binding site, the patient-derived TS sequence, the Cas9 cleavage site, the sgRNA binding site, and the PAM highlighted. (B) Ethidium bromide (EthBr)–stained agarose gel showing endpoint PCR products obtained with DNA from HeLa-superT cells expressing TS or luciferase sgRNA harvested at the indicated times after AdCas9 infection. A plasmid template simulating neotelomere addition in the expected frame of addition was spiked into human DNA as a positive control (lane 5). (C) TaqMan-qPCR quantification of neotelomeres in (B). (D) EthBr-stained agarose gel showing endpoint PCR products obtained with DNA from HeLa-superT cells treated with BIBR1532 (20 μM) or DMSO (vehicle). Sample labeling and controls as in (B). (E) TaqMan PCR quantification of neotelomeres in cells in (D). Data points bearing the same color belong to the same biological replicate. (F) EthBr-stained polyacrylamide gel showing TRAP assay products obtained with extracts from p53−/− Rb−/− RPE1 cells infected with pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS and then infected with a retroviral vector (vec), a retrovirus expressing catalytically dead (CD) hTERT, or a retrovirus expressing wild-type hTERT plus hTR (superT). As a control, extracts were heat inactivated (heated). IC, internal PCR control. (G) Quantification of neotelomeres formed in the RPE1 cells shown in (F) at the indicated times after infection with AdCas9. sT, superT. Mean ± SD of at least 3 biological replicates. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, two-tailed ratio-paired t-test in (E) and two-tailed unpaired t-test in (G).

The telomerase inhibitor BIBR1532 (11) reduced neotelomere formation by ~4-fold in HeLa-superT cells (Fig. 1D and E). To confirm the role of telomerase, we manipulated the telomerase activity of pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS-infected p53−/− Rb−/− RPE1 cells (12). These cells’ low telomerase activity was further reduced by expression of catalytically dead hTERT (hTERT-CD; D712A/V713I (13)) and increased with a vector encoding both wild-type hTERT and hTR that confers super-telomerase activity (14). Telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) assays showed that hTERT-CD reduced telomerase activity compared to the empty vector control (vec), whereas overexpression of hTERT and hTR increased it by at least 5-fold (Fig. 1F; compare lanes 4 and 13). Compared to the vector control, neotelomere formation was increased by ~40-fold in the super-telomerase cells (hereafter RPE1-superT cells) and reduced by expression of hTERT-CD (Fig. 1G). These results establish that the neotelomere products are generated by telomerase and indicate that telomerase levels are limiting in the TTAGGG repeat addition events detected by this assay.

In yeast, HO endonuclease cuts have been used to monitor neotelomere formation at DSBs (15, 16). In those experiments, neotelomere formation required tracts of yeast telomeric repeats at or near the DNA end, whereas human neotelomere formation at Cas9-induced breaks occurs in absence of such telomeric repeat tracts (referred to as telomere seeds). Whether telomere seeds enhance neotelomere formation in human cells remains to be tested. Given the lack of motifs in neotelomere formation breakpoint sequences (fig. S1), it is also unclear how many sites in the human genome are vulnerable to neotelomere formation.

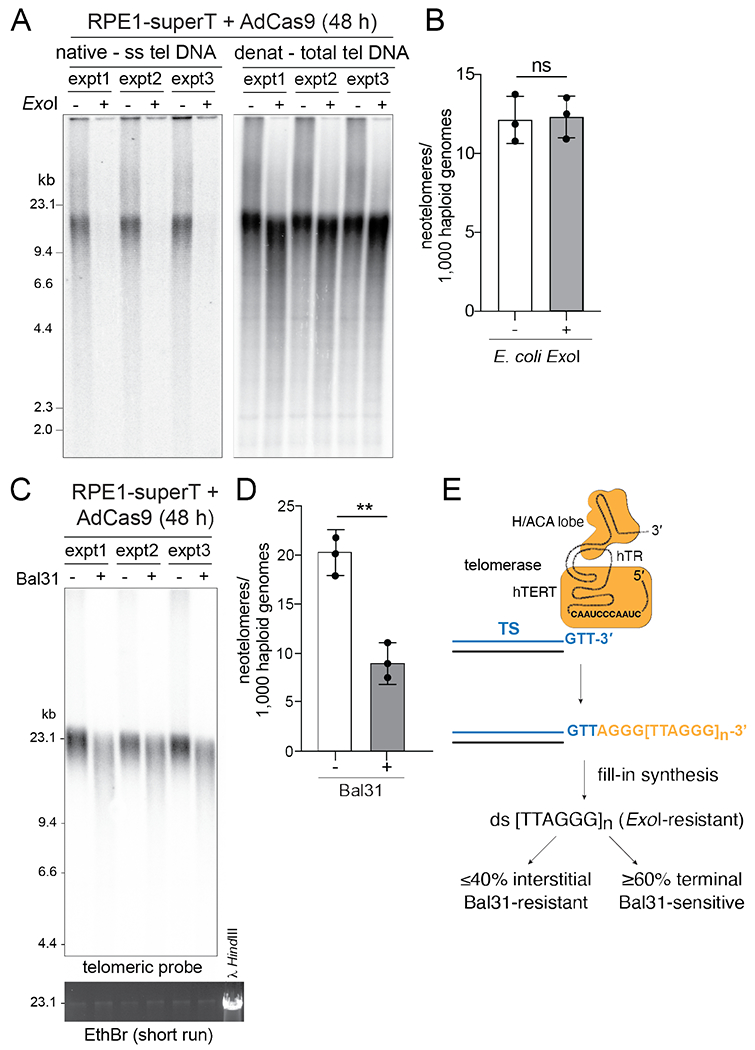

Telomerase products give rise to interstitial and terminal dsTTAGGG repeats

To determine whether the ss TTAGGG repeats synthesized by telomerase are converted into duplex DNA, we determined whether the detection of neotelomere formation was reduced by treating genomic DNA with E. coli 3’ exonuclease ExoI prior to the TaqMan qPCR. The efficacy of the ExoI treatment was confirmed based on removal of the telomeric 3’ overhang, detected by in-gel hybridization of a telomeric C-strand probe to native DNA (Fig. 2A). Nonetheless, ExoI did not affect the detection of neotelomere formation events in RPE1-superT cells (Fig. 2B), indicating that the TTAGGG repeats synthesized by telomerase are converted into duplex DNA.

Fig. 2. Telomerase generates interstitial and terminal telomeric repeat arrays.

(A) Telomeric overhang assay to monitor the effect of E. coli ExoI treatment. DNAs from RPE1-superT cells at 48 h after infection with AdCas9 with or without ExoI treatment were digested with MboI/AluI and analyzed by in-gel hybridization to a telomeric C-strand probe (left). The gel denatured, and the total telomeric DNA was detected by rehybridization with the same probe (right). (B) Quantification of neotelomeres by TaqMan qPCR on the DNA samples shown in (A). (C) Southern blot for telomeric DNA showing the expected shortening effect of telomeric restriction fragments by Bal31 treatment of intact genomic DNA. DNAs were from three independent AdCas9 infections of RPE1-superT cells. EthBr staining of large-MW DNA fragments shows that Bal31 has not degraded bulk genomic DNA. (D) Quantification of neotelomeres by TaqMan qPCR on the DNA samples in (C). (E) Summary of the fate of the TTAGGG repeats added by telomerase. Mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates. ns, not significant; p > 0.05, ** p < 0.01, based on two-tailed ratio-paired t-test in (A), (D), and (F).

We next asked whether the detected neotelomere formation events corresponded to TTAGGG repeats at interstitial or terminal sites. Terminal TTAGGG repeats should be sensitive to digestion of intact genomic DNA with Bal31 nuclease (17), which digests both strands at telomeric DNA ends in otherwise intact genomic DNA, whereas interstitial TTAGGG repeats should not be affected. DNA from Cas9-infected RPE1-superT cells was treated with Bal31 and subsequently digested with MboI/AluI to allow detection of the telomeric fragments in Southern blots, which showed the expected shortening of the telomeric fragments by Bal31 (Fig. 2C). TaqMan qPCR on these samples showed that Bal31 removed 60% of the neotelomere formation events, indicating that the majority of neotelomeres were terminal (Fig. 2D and E). Presumably, binding of shelterin to long duplex telomeric repeat arrays protects the ends from ligation to the other DNA end created by Cas9. The interstitial TTAGGG repeats could reflect the fate of short duplex arrays that lacked sufficient shelterin.

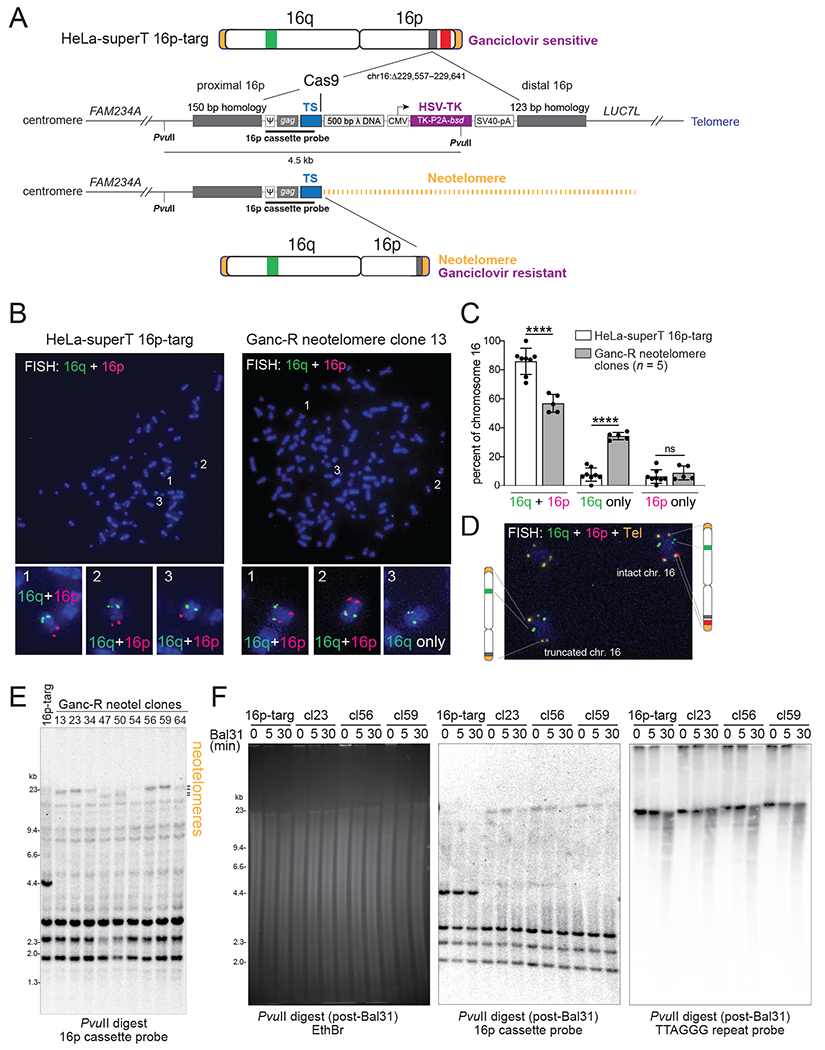

Telomerase generates functional neotelomeres and terminal chromosome truncations

To determine whether the neotelomeres generated by telomerase are functional, we inserted a modified TS cassette into the LUC7L locus on the distal part of chromosome 16p of HeLa-superT cells (Fig. 3A). The Cas9-cleavable TS site was positioned centromeric to HSV thymidine kinase (TK) so that neotelomere formation at TS would remove TK and render cells ganciclovir resistant. A HeLa-superT clone with the correct insertion (HeLa-superT 16p-targ; fig. S3A and B) was infected with an sgTS-expressing lentivirus and AdCas9. PCR screening of 67 ganciclovir-resistant clones showed that 20 (30%) had telomeric repeat addition at TS (fig. S3C and D).

Fig. 3. Telomerase forms functional neotelomeres.

(A) Experimental strategy to select for cells in which telomerase has formed a functional telomere at a DSB. A schematic of the CRISPR/Cas12a-edited chromosome 16 in the HeLa-superT 16p targeted clone (16p-targ) is shown, indicating the position of the knock-in cassette (grey) between FAM234A and LUC7L and the approximate locations of the 16q (green) and 16p (red) FISH probes. The knock-in cassette contains two homology arms and a Cas9-cleavable TS site separated by 500 bp bacteriophage λ DNA from the herpes simplex virus (HSV) thymidine kinase (TK) gene, which sensitizes cells to ganciclovir (Ganc). Positions of PvuII restriction sites and the 904-bp Southern blotting probe are indicated. Functional neotelomere formation at TS is predicted to result in loss of TK expression, ganciclovir resistance, loss of the 16p FISH signal, and a change in the size of the PvuII restriction fragment. ψ, MMLV packaging signal; CMV, cytomegalovirus promoter; P2A, 2A peptide from porcine teschovirus-1; bsd, blasticidin S deaminase gene; SV40-pA, simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal. The inset shows the sequence of TS PCR cassette, with the primer and TaqMan binding sites and patient-derived TS sequence indicated. (B) Representative examples of metaphase FISH (see (A)) performed on the parental HeLa-superT 16p-targ and one of the Ganc-R daughter clones (clone 13). The three copies of chromosome 16 are numbered and shown at higher magnification below. (C) Quantification of metaphase FISH in (B). Copies of chromosome 16 were identified by hybridization with either the p or q arm probe and scored as hybridizing with both the p and q arm probes, only the p arm probe, or only the q arm probe. Mean ± SD from eight technical replicates of 23 metaphases for the HeLa-superT 16p-targ and pooled data from clones 13, 34, 50, 54, and 64 (1-3 replicates per clone with 18-27 metaphases per replicate). ns p > 0.05, **** p < 0.0001, two-tailed unpaired t-test. (D) FISH on clone 13 with the two chromosome 16 probes in combination with a telomere probe (yellow). The partial metaphase shows one intact chr. 16, an irrelevant autosome, and the truncated chr. 16. (E) Southern blot of PvuII-digested DNA from the parental HeLa-superT 16p-targ and nine Ganc-R neotelomere clones probed with the 16p cassette probe indicated in (A). The position of the neotelomeres is indicated. (F) Southern blot of DNA from the indicated clones treated with Bal31 exonuclease as indicated, followed by digestion with PvuII. Left: EthBr-stained gel; middle: blot hybridized as in (E); right: same blot reprobed with a radio-labelled telomeric C-strand oligonucleotide.

Metaphases of six clones with PCR evidence for neotelomere formation were queried by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for loss of the distal segment of 16p (Fig. 3A–C and fig. S3E). FISH to a subtelomeric 16q segment and part of 16q showed that the parental cell line had three copies of chromosome 16 (Fig. 3B), consistent with the near-triploid karyotype of HeLa cells. Five of the six neotelomere clones carried a chromosome 16 lacking the distal p arm segment (Fig. 3B and C). In the neotelomere clones, the percentage of chromosome 16 copies staining for both the q and p FISH probes decreased, whereas the percentage of chromosomes staining for only 16p increased (Fig. 3C). A sixth neotelomere clone had one wild-type chromosome 16 and a derivative chromosome 16 with only the 16q signal, again consistent with neotelomere formation (fig. S3E). However, in this clone, the subtelomeric segments of 16p appeared to have been attached to another chromosome (fig. S3E). Analysis of one of the neotelomere clones with a combination of FISH probes for 16q, 16p, and TTAGGG repeats showed one copy of chromosome 16 with a telomere at the truncated p arm (Fig. 3D).

In an orthogonal approach, Southern blots of PvuII-digested genomic DNA were probed with a 904-bp radio-labelled fragment from the TS cassette that should detect a 4.5-kb fragment if the TS cassette is intact and larger fragments if a neotelomere is added (Fig. 3A). Each of nine clones, including the cytogenetically unusual clone 23 (fig. S3E), showed a large fragment (~20 kb), instead of the 4.5-kb PvuII fragment of the parental cells (Fig. 3E). The lengths of the telomeric PvuII fragments matched the lengths of the endogenous telomeres (Fig. 3F), consistent with telomerase adding ~600 bp of TTAGGG repeats per population doubling in HeLa-superT cells (10) over the ~45 days before DNA isolation. To determine whether the large fragments were terminal, as expected for neotelomeres, the genomic DNAs were treated with Bal31 before PvuII digestion. The neotelomeric PvuII fragments showed Bal31 sensitivity that mirrored that of the native telomeres (Fig. 3F). Therefore, telomeric repeat addition at TS can yield functional neotelomeres.

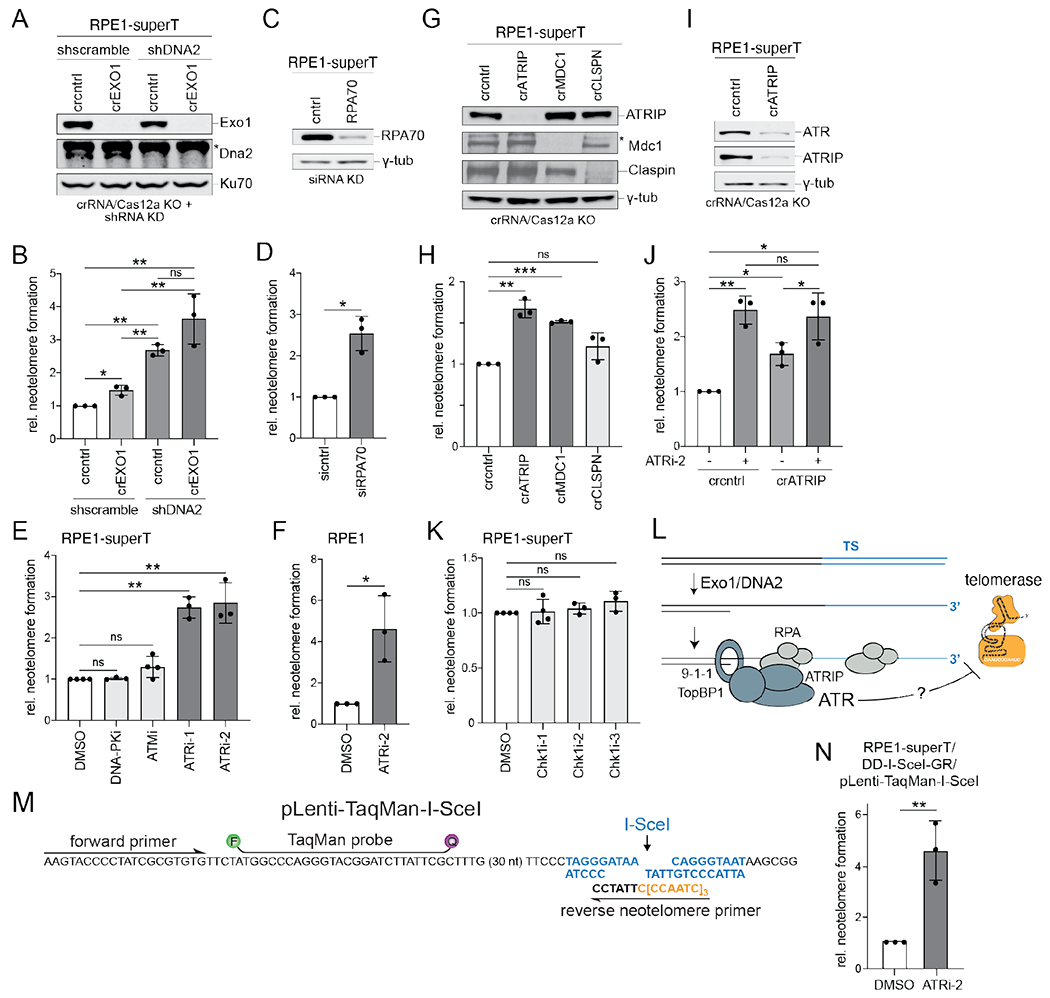

Repression of neotelomere formation by ATR signaling at resected DSBs

Although neotelomere formation is rare, even under the optimized conditions used here, we anticipated that neotelomere formation is repressed to prevent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of genes distal to the break. Neotelomere formation could be averted if DSB repair pathways compete with telomerase at DSBs. However, inhibition of classical non-homologous end joining by CRISPR targeting Lig4 and Ku70/80, homology-directed repair by targeting BRCA2, alternative end joining by targeting Lig3 and PARP1, or single-strand annealing by targeting Rad52 (fig. S4A) had little effect on neotelomere formation (fig. S4B), suggesting that no single DSB repair pathway competes substantially with telomerase. Similarly, there was no effect of targeting the Pif1 helicase, the main inhibitor of telomerase at DSBs in yeast (18), in either RPE1-superT cells or in RPE1 cells, nor was there an effect of targeting two other candidate negative regulators of telomerase at DSBs, MLH1 and PINX1 (19, 20) (fig. S4C–G).

We next asked whether neotelomere formation was affected by disrupting long-range resection by Exo1 and DNA2 (21), which affects telomerase action at DSBs in budding yeast (22).

Neotelomere formation was increased by targeting of Exo1 (1.5-fold), shRNA knockdown of DNA2 (2.7-fold), and combined depletion of Exo1 and DNA2 (3.6-fold) (Fig. 4A and B). We therefore tested whether neotelomere formation was inhibited by RPA, which binds to resected DSBs and mediates ATR kinase activation (23). RPA depletion with siRNA elicited a 2.5-fold increase in neotelomere formation (Fig. 4C and D), and treatment with two ATR inhibitors (VE-821 and gartisertib/M4344) nearly tripled the frequency of the events, whereas inhibitors of DNA-PKcs or ATM had no effect (Fig. 4E). ATRi only slightly increased the S-phase index of the cells (fig. S5A). ATR inhibition also markedly increased neotelomere formation in RPE1 cells with low telomerase activity levels (Fig. 4F). Consistent with ATR suppressing telomerase at DSBs, CRISPR targeting of its partner, ATRIP, increased neotelomere formation modestly (Fig. 4G and H). The removal of ATRIP was probably inefficient since ATRi treatment of ATRIP-targeted cells further increased neotelomere formation (Fig. 4I and J). These data are consistent with ATR-dependent repression of telomerase at DSBs that have undergone 5’ resection (Fig. 4L).

Fig. 4. Repression of telomerase by long-range resection, RPA, and ATR signaling.

(A) Immunoblots for the indicated proteins performed on RPE1-superT cells treated with CRISPR/Cas12 crRNA targeting EXO1 or a non-targeting control (cntrl) followed by shRNAs targeting DNA2 or a scramble shRNA control. Ku70, loading control; * non-specific band. (B) Quantification of relative neotelomere formation by TaqMan qPCR in cells in (A) normalized to cells treated with the control crRNA and scramble shRNA. (C) Immunoblot for RPA70 in RPE1-superT cells treated with a control (cntrl) siRNA or two siRNAs targeting RPA70. γ-tub, loading control. (D) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in cells in (C) normalized to cells treated with control siRNA. (E) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR 48 h after AdCas9 infection of RPE1-superT cells treated with DMSO or the indicated inhibitors. (F) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR 48 h after AdCas9 infection of pLenti-sgTSTaqMan-TS RPE1 cells treated with DMSO or ATRi-2. (G) Immunoblots for the indicated proteins in RPE1-superT cells after CRISPR/Cas12a targeting. γ-tub, loading control; * non-specific band. (H) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in cells in (G) normalized to cells treated with the control crRNA. (I) Immunoblots for the indicated proteins from RPE1-ST cells after targeting with ATRIP crRNA or a control (cntrl) crRNA. γ-tub, loading control. (J) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in cells in (I). (K) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in RPE1-superT cells treated with the indicated Chk1 inhibitors normalized to cells treated with DMSO. (L) Schematic illustrating the inhibitory effect of ATR on neotelomere formation at resected DSBs. (M) Schematic of the lentiviral vector to test neotelomere formation at I-SceI-induced DSBs, showing the primers for neotelomere formation detection, the I-SceI site, and the TaqMan probe. (N) Effect of ATRi-2 on neotelomere formation at I-SceI-induced DSBs. Mean ± SD of at least 3 biological replicates. ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, two-tailed ratio-paired t-test in (B), (D), (E), (F), (H), (J), (K), and (N). DNA-PKcsi, AZD-6748, 10 μM; ATMi, KU55933, 10 μM; ATRi-1, VE-821, 10 μM; ATRi-2, Gartisertib/M4344, 0.3 μM in (E) and (F) and 1 μM in (J) and (N); Chk1i-1, CHIR124, 0.25 μM; Chk1i-2, MK-8776, 1 μM; Chk1i-3, CCT245737, 1 μM.

To verify that ATR represses neotelomere formation, we designed a lentiviral vector to detect neotelomere formation at I-SceI-induced DSBs (Fig. 4M). Neotelomere formation has previously been documented at a subtelomeric I-SceI site in mouse embryonic stem cells (24). When I-SceI was induced (25) (fig. S5B) in RPE1-superT cells that had been infected with the TaqMan-I-SceI lentivirus, TaqMan qPCR (Fig. 4M; fig. S5C and D) showed neotelomere formation at ~3 events per 1,000 haploid genomes, and, as was the case for the Cas9-induced DSBs, ATRi increased the frequency by 4–5-fold (Fig. 4N).

Inhibition of Chk1 or targeting claspin had no effect on neotelomere formation, arguing against downstream signaling by ATR (Fig. 4G, H and K). By contrast, neotelomere formation was increased upon targeting of MDC1 (Fig. 4G and H), suggesting that ATR is acting locally, perhaps by phosphorylating a component of the DNA damage foci established by MDC1. One such component, 53BP1, did not affect neotelomere formation (fig. S5E and F). Nonetheless, 53BP1 removal diminished the effect of ATRi (fig. S5F) for reasons that remain to be determined. Several other potential ATR targets also had no effect on neotelomere formation, including hSSB1, RadX, BLM, WRN, SLX4, and XPF (fig. S5G–M), although targeting of FANCJ and Rad51 led to modest increases in the events (fig. S5H and J). Further work will be required to determine how ATR antagonizes telomerase at DSBs.

Telomerase can add telomeric repeats to the Cas9 enzyme-product complex

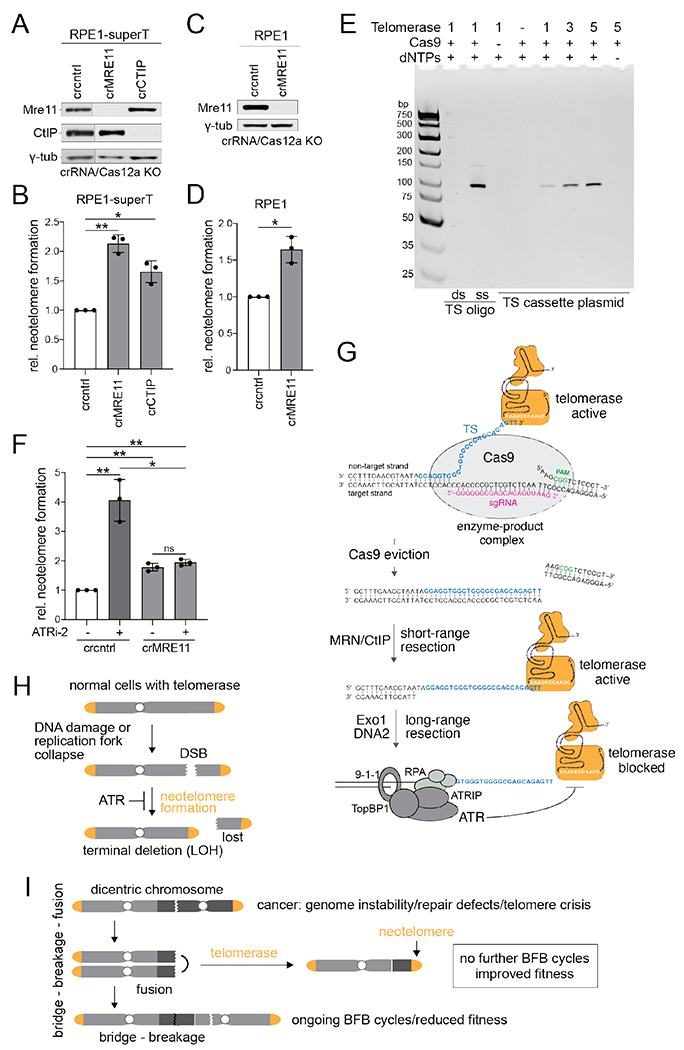

Since telomerase requires a 3’ overhang in vitro (26), we anticipated that neotelomere formation would require the MRN (Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1)/CtIP-mediated endonucleolytic cleavage that creates short 3’ overhangs at DSBs (21). However, CRISPR targeting of Mre11 or CtIP increased neotelomere formation (Fig. 5A–D) whereas MRN deficiency had a minimal effect on the cell cycle profile (fig. S5A). Consistent with the lack of requirement for MRN/CtIP, G1-arrested cells showed robust neotelomere formation (fig. S6A–C).

Fig. 5. Neotelomere formation at Cas9 enzyme-product complexes.

(A) Immunoblot for the indicated proteins from RPE1-superT cells treated with Cas12a and crRNAs targeting MRE11 or CtIP or a control crRNA. γ-tub, loading control. The blot was cut between lanes 1 and 2 to remove lanes corresponding to irrelevant samples. (B) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in cells in (A). (C) Immunoblot for the indicated proteins 5 in pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS RPE1 cells treated with Cas12a and crRNAs targeting MRE11 or a control (cntrl) crRNA. γ-tub, loading control. (D) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in cells in (C). (E) In vitro assay for telomerase acting at the Cas9 enzyme-product complex. In vitro telomeric repeat addition by telomerase at the TS cut site after incubating the TS cassette plasmid with Cas9 and sgTS (Fig. 1A) was detected by EthBr staining of the generated PCR products, as in Fig. 1B. Control oligonucleotides represent the Cas9 cut at TS in ss and ds form. (F) Relative neotelomere formation based on qPCR in pLenti-sgTS-TaqMan-TS RPE1 cells targeted for MRE11 with or without ATRi. Mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates. ns p > 0.05, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, two-tailed ratio-paired t-test. ATRi-2, gartisertib/M4344, 0.3 μM. (G) Model for neotelomere formation at Cas9-induced DSBs in the presence and absence of MRN/CtIP, highlighting two priming sites for telomerase. When Cas9 persists, the extruded non-target strand is the substrate, and MRN/CtIP is not required. When Cas9 is evicted, short-range resection by MRN/CtIP is required to generate the free 3’ end for telomerase priming. Long-range resection activates ATR, which inhibits telomerase at the resected DSB. (H) Neotelomere formation in normal human cells is limited by the low (or no) telomerase expression and/or by ATR signaling at resected DSBs or regressed replication forks. Neotelomere formation induces terminal deletions and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for distal genes. (I) Potential role for neotelomere formation in cancer. Neotelomere formation may enhance cancer genome evolution by enforcing LOH (as in (H)) and end ongoing BFB cycles in genomically unstable cancer clones, thereby enhancing their fitness.

The lack of requirement for MRN/CtIP suggested that, in the Cas9 assay, a ss telomerase primer is generated without the aid of resection. Cas9 can form a stable enzyme-product complex with its DNA target (27) in which the cleaved non-target strand protrudes (28). Therefore, the Cas9 enzyme-product complex might present ss TS to telomerase, obviating the need for MRN/CtIP. We tested this idea in vitro by incubating Cas9 with TS cassette DNA and the TS sgRNA in the presence of purified human telomerase (Fig. 5E). PCR for neotelomere formation showed that telomerase generated the expected product in a Cas9- and dNTP-dependent manner. Incubation of telomerase with the duplex product formed by Cas9 cleavage verified that telomerase cannot use a dsDNA end as a primer (Fig. 5E).

The protruding strand in the Cas9 enzyme-product complex (Fig. 5G) is too short for RPA loading and there is no 5’ end for the loading of 9-1-1/RFC17, which are both required for ATR activation (23). Therefore, in Mre11-deficient cells, where this substrate may be the predominant telomerase primer, ATR should not inhibit neotelomere formation. Consistent with this prediction, treatment of Mre11-deficient cells with an ATR inhibitor had no effect on neotelomere formation (Fig. 5F). Thus, in the Cas9 assay system, neotelomere formation occurs at DSBs where Cas9-sgRNA binding has displaced the 3’ end as well as at evacuated DSBs that have been resected and where ATR can inhibit telomerase (Fig. 5G).

Discussion

These results establish that human telomerase can add telomeric DNA to DSBs, promoting the synthesis of functional telomeres and thereby creating terminal deletions (Fig. 5H). In addition, the action of telomerase at DSBs can lead to potentially mutagenic interstitial TTAGGG repeat insertions. These threats are minimized by the low telomerase activity in most human cells and further diminished by ATR signaling at resected DNA ends (Fig. 5H).

The formation of functional neotelomeres requires that newly synthesized telomeric DNA binds shelterin, which blocks end-joining reactions that lead to interstitial insertions. Once shelterin protects the nascent telomere, its TPP1 subunit can recruit telomerase to allow further extension. The neotelomeres reached the same lengths as the cells’ other telomeres, consistent with prior observations on telomere formation using transfected telomere seeds (29).

Sites of neotelomere formation

Our assay used Cas9 cleavage at TS, which is one of many suspected neotelomere formation events. Given the diverse nature of these sequences (fig. S1), neotelomere formation is likely not restricted to TS and may imperil many DSBs. Indeed, neotelomere formation also occurred at an I-SceI site, a sequence unrelated to TS.

The neotelomere formation assay monitors telomeric repeat addition to two types of DNA ends (Fig. 5G). First, since ATR inhibits neotelomere formation at both Cas9- and I-SceI-induced DSBs, many of the detected events occur at DNA ends that have undergone 5’ resection (Fig. 5G). Such resected DNA ends also occur at regressed or broken replication forks, creating the potential for terminal deletions during replication stress (Fig. 5H). The second type of DNA end used by telomerase is the extruded non-target strand in the Cas9 enzyme-product complex (Fig. 5G). In the context of therapeutic CRISPR-based genome editing, it may be prudent to avoid potential base-pairing between the 3’ end of the non-target strand and the template sequence in hTR.

Neotelomere formation in cancer

Most human cancer genomes contain numerous structural variations (30), indicating that most cancers experience DSBs during tumorigenesis (31). The extent to which such breaks are converted into neotelomeres may depend on the expression level of telomerase and the selective advantage afforded by LOH. Notably, long-read sequencing suggested neotelomere formation in ~25% of lung cancers (32). Neotelomere formation may also provide an advantage in the context of ongoing BFB cycles (Fig. 5I), which can result from telomere crisis and DNA repair deficiencies ((33); reviewed in (34)). Many human cancers bear the genomic scars of past BFB cycles, including >40% of esophageal, stomach, bladder, and non-small-cell lung cancer (35). While repeated BFB cycles can accelerate tumor evolution, they also could compromise cellular fitness through loss of essential genes, detrimental effects during mitosis, and cGAS-STING activation by cytoplasmic DNA (36–38). We propose that by terminating BFB cycles, neotelomere formation by telomerase may enable fledgling cancer cells to cope with genome instability (Fig. 5I).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

HeLa-superT cells and purified telomerase were kind gifts from Dr. Joachim Lingner. We thank Drs. John Maciejowski, Marcin Imieliński, Dirk Hockemeyer, David Cortez, Tom Cech, and members of the de Lange lab for helpful discussion of this work. We thank the members of the Rockefeller University Genomics Resource Center, especially Bin Zhang, for their assistance with qPCR.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health R35 CA210036 (TdL)

Breast Cancer Research Foundation BCRF-22-036 (TdL)

STARR Cancer Consortium I13-0019 (TdL)

National Institutes of Health F30CA257419 (CGK)

National Institutes of Health T32GM007739 (CGK, GZ)

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

Unique cell lines, plasmids, and antibodies generated in this study are available upon request. All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes

- 1.de Lange T, Shelterin-Mediated Telomere Protection. Annu Rev Genet 52, 223–247 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu RA, Upton HE, Vogan JM, Collins K, Telomerase Mechanism of Telomere Synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem 86, 439–460 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abreu E, Aritonovska E, Reichenbach P, Cristofari G, Culp B, Terns RM, Lingner J, Terns MP, TIN2-tethered TPP1 recruits human telomerase to telomeres in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 30, 2971–2982 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hockemeyer D, Collins K, Control of telomerase action at human telomeres. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22, 848–852 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClintock B, The Production of Homozygous Deficient Tissues with Mutant Characteristics by Means of the Aberrant Mitotic Behavior of Ring-Shaped Chromosomes. Genetics 23, 315 376 (1938). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClintock B, The Stability of Broken Ends of Chromosomes in Zea Mays. Genetics 26, 234–282 (1941). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClintock B, Letter from Barbara McClintock to Elizabeth H. Blackburn. (1983). https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/101584613X60 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkie AO, Lamb J, Harris PC, Finney RD, Higgs DR, A truncated human chromosome 16 associated with alpha thalassaemia is stabilized by addition of telomeric repeat (TTAGGG)n. Nature 346, 868–871 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morin GB, Recognition of a chromosome truncation site associated with alpha-thalassaemia by human telomerase. Nature 353, 454–456 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cristofari G, Lingner J, Telomere length homeostasis requires that telomerase levels are limiting. EMBO J 25, 565–574 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascolo E, Wenz C, Lingner J, Hauel N, Priepke H, Kauffmann I, Garin-Chesa P, Rettig WJ, Damm K, Schnapp A, Mechanism of human telomerase inhibition by BIBR1532, a synthetic, non-nucleosidic drug candidate. J Biol Chem 277, 15566–15572 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Z, Maciejowski J, de Lange T, Nuclear Envelope Rupture Is Enhanced by Loss of p53 or Rb. Mol Cancer Res 15, 1579–1586 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn WC, Stewart SA, Brooks MW, York SG, Eaton E, Kurachi A, Beijersbergen RL, Knoll JH, Meyerson M, Weinberg RA, Inhibition of telomerase limits the growth of human cancer cells. Nat Med 5, 1164–1170 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong JM, Collins K, Telomerase RNA level limits telomere maintenance in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Genes Dev 20, 2848–2858 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diede SJ, Gottschling DE, Telomerase-mediated telomere addition in vivo requires DNA primase and DNA polymerases alpha and delta. Cell 99, 723–733 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer KM, Haber JE, New telomeres in yeast are initiated with a highly selected subset of TG1-3 repeats. Genes Dev 7, 2345–2356 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Lange T, Borst P, Genomic environment of the expression-linked extra copies of genes for surface antigens of Trypanosoma brucei resembles the end of a chromosome. Nature 299, 451–453 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz VP, Zakian VA, The saccharomyces PIF1 DNA helicase inhibits telomere elongation and de novo telomere formation. Cell 76, 145–155 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia P, Chastain M, Zou Y, Her C, Chai W, Human MLH1 suppresses the insertion of telomeric sequences at intra-chromosomal sites in telomerase-expressing cells. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 1219–1232 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou XZ, Lu KP, The Pin2/TRF1-interacting protein PinX1 is a potent telomerase inhibitor. Cell 107, 347–359 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cejka P, Symington LS, DNA End Resection: Mechanism and Control. Annu Rev Genet 55, 285–307 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeyre C, Shore D, Regulation of telomere addition at DNA double-strand breaks. Chromosoma 122, 159–173 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saldivar JC, Cortez D, Cimprich KA, The essential kinase ATR: ensuring faithful duplication of a challenging genome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 622–636 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sprung CN, Reynolds GE, Jasin M, Murnane JP, Chromosome healing in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 6781–6786 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bindra RS, Goglia AG, Jasin M, Powell SN, Development of an assay to measure mutagenic non-homologous end-joining repair activity in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res 41, e115 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingner J, Cech TR, Purification of telomerase from Euplotes aediculatus: requirement of a primer 3’ overhang. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 10712–10717 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sternberg SH, Redding S, Jinek M, Greene EC, Doudna JA, DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu X, Clarke R, Puppala AK, Chittori S, Merk A, Merrill BJ, Simonović M, Subramaniam S, Cryo-EM structures reveal coordinated domain motions that govern DNA cleavage by Cas9. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26, 679–685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanish JP, Yanowitz JL, de Lange T, Stringent sequence requirements for the formation of human telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 8861–8865 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, Huang MN, Tian Ng AW, Wu Y, Boot A, Covington KR, Gordenin DA, Bergstrom EN, Islam SMA, Lopez-Bigas N, Klimczak LJ, McPherson JR, Morganella S, Sabarinathan R, Wheeler DA, Mustonen V, PCAWG MSWG, Getz G, Rozen SG, Stratton MR, PCAWG C, The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 578, 94–101 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerstung M, Jolly C, Leshchiner I, Dentro SC, Gonzalez S, Rosebrock D, Mitchell TJ, Rubanova Y, Anur P, Yu K, Tarabichi M, Deshwar A, Wintersinger J, Kleinheinz K, Vázquez-García I, Haase K, Jerman L, Sengupta S, Macintyre G, Malikic S, Donmez N, Livitz DG, Cmero M, Demeulemeester J, Schumacher S, Fan Y, Yao X, Lee J, Schlesner M, Boutros PC, Bowtell DD, Zhu H, Getz G, Imielinski M, Beroukhim R, Sahinalp SC, Ji Y, Peifer M, Markowetz F, Mustonen V, Yuan K, Wang W, Morris QD, PCAWG EHWG, Spellman PT, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, PCAWG C, The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Nature 578, 122–128 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan K-T, Slevin MK, Leibowitz ML, Garrity-Janger M, Li H, Meyerson M, Neotelomeres and Telomere-Spanning Chromosomal Arm Fusions in Cancer Genomes Revealed by Long-Read Sequencing. bioRxiv 2023.11.30.569101 [Preprint] (2023). https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.11.30.569101v1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dewhurst SM, Yao X, Rosiene J, Tian H, Behr J, Bosco N, Takai KK, de Lange T, Imieliński M, Structural variant evolution after telomere crisis. Nat Commun 12, 2093 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maciejowski J, de Lange T, Telomeres in cancer: tumour suppression and genome instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 175–186 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadi K, Yao X, Behr JM, Deshpande A, Xanthopoulakis C, Tian H, Kudman S, Rosiene J, Darmofal M, DeRose J, Mortensen R, Adney EM, Shaiber A, Gajic Z, Sigouros M, Eng K, Wala JA, Wrzeszczyński KO, Arora K, Shah M, Emde AK, Felice V, Frank MO, Darnell RB, Ghandi M, Huang F, Dewhurst S, Maciejowski J, de Lange T, Setton J, Riaz N, Reis-Filho JS, Powell S, Knowles DA, Reznik E, Mishra B, Beroukhim R, Zody MC, Robine N, Oman KM, Sanchez CA, Kuhner MK, Smith LP, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Reid BJ, Li X, Wilkes D, Sboner A, Mosquera JM, Elemento O, Imielinski M, Distinct Classes of Complex Structural Variation Uncovered across Thousands of Cancer Genome Graphs. Cell 183, 197–210.e32 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ablasser A, Chen ZJ, cGAS in action: Expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science 363, eaat8657 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li T, Chen ZJ, The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J Exp Med 215, 1287–1299 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motwani M, Pesiridis S, Fitzgerald KA, DNA sensing by the cGAS-STING pathway in health and disease. Nat Rev Genet 20, 657–674 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T, Telomeric 3’ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell 150, 39–52 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zetsche B, Heidenreich M, Mohanraju P, Fedorova I, Kneppers J, DeGennaro EM, Winblad N, Choudhury SR, Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Wu WY, Scott DA, Severinov K, van der Oost J, Zhang F, Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat Biotechnol 35, 31–34 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamb J, Harris PC, Wilkie AO, Wood WG, Dauwerse JG, Higgs DR, De novo truncation of chromosome 16p and healing with (TTAGGG)n in the alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome (ATR-16). Am J Hum Genet 52, 668–676 (1993). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flint J, Craddock CF, Villegas A, Bentley DP, Williams HJ, Galanello R, Cao A, Wood WG, Ayyub H, Higgs DR, Healing of broken human chromosomes by the addition of telomeric repeats. Am J Hum Genet 55, 505–512 (1994). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong AC, Ning Y, Flint J, Clark K, Dumanski JP, Ledbetter DH, McDermid HE, Molecular characterization of a 130-kb terminal microdeletion at 22q in a child with mild mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 60, 113–120 (1997). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varley H, Di S, Scherer SW, Royle NJ, Characterization of terminal deletions at 7q32 and 22q13.3 healed by De novo telomere addition. Am J Hum Genet 67, 610–622 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horsley SW, Daniels RJ, Anguita E, Raynham HA, Peden JF, Villegas A, Vickers MA, Green S, Waye JS, Chui DH, Ayyub H, MacCarthy AB, Buckle VJ, Gibbons RJ, Kearney L, Higgs DR, Monosomy for the most telomeric, gene-rich region of the short arm of human chromosome 16 causes minimal phenotypic effects. Eur J Hum Genet 9, 217–225 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballif BC, Yu W, Shaw CA, Kashork CD, Shaffer LG, Monosomy 1p36 breakpoint junctions suggest pre-meiotic breakage-fusion-bridge cycles are involved in generating terminal deletions. Hum Mol Genet 12, 2153–2165 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yatsenko SA, Brundage EK, Roney EK, Cheung SW, Chinault AC, Lupski JR, Molecular mechanisms for subtelomeric rearrangements associated with the 9q34.3 microdeletion syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 18, 1924–1936 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hannes F, Van Houdt J, Quarrell OW, Poot M, Hochstenbach R, Fryns JP, Vermeesch JR, Telomere healing following DNA polymerase arrest-induced breakages is likely the main mechanism generating chromosome 4p terminal deletions. Hum Mutat 31, 1343–1351 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Beri S, De Agostini C, Novara F, Fichera M, Grillo L, Galesi O, Vetro A, Ciccone R, Bonati MT, Giglio S, Guerrini R, Osimani S, Marelli S, Zucca C, Grasso R, Borgatti R, Mani E, Motta C, Molteni M, Romano C, Greco D, Reitano S, Baroncini A, Lapi E, Cecconi A, Arrigo G, Patricelli MG, Pantaleoni C, D’Arrigo S, Riva D, Sciacca F, Dalla Bernardina B, Zoccante L, Darra F, Termine C, Maserati E, Bigoni S, Priolo E, Bottani A, Gimelli S, Bena F, Brusco A, di Gregorio E, Bagnasco I, Giussani U, Nitsch L, Politi P, Martinez-Frias ML, Martínez-Fernández ML, Martínez Guardia N, Bremer A, Anderlid BM, Zuffardi O, Molecular mechanisms generating and stabilizing terminal 22q13 deletions in 44 subjects with Phelan/McDermid syndrome. PLoS Genet 7, e1002173 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guilherme RS, Hermetz KE, Varela PT, Perez AB, Meloni VA, Rudd MK, Kulikowski LD, Melaragno MI, Terminal 18q deletions are stabilized by neotelomeres. Mol Cytogenet 8, 32 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Unique cell lines, plasmids, and antibodies generated in this study are available upon request. All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.