Whether repeated concussive or subconcussive blows cause permanent or cumulative brain injury is a complex and controversial question. Press coverage highlighted the case of Jeff Astle, a former England international football player, where the coroner ruled the cause of his death as an “industrial disease”—suggesting that repeated heading of balls during his professional career was the cause of his subsequent neurological decline.1 This case was at odds with that of Billy MacPhail, a former Glasgow Celtic player, who in 1998 lost a legal battle to claim benefits for dementia that he said was due to heading the old style leather footballs. Concern has been raised over whether heading in soccer may be the basis for injury and cognitive impairment, and in the United States this has led to calls advocating the use of protective headgear for soccer players.

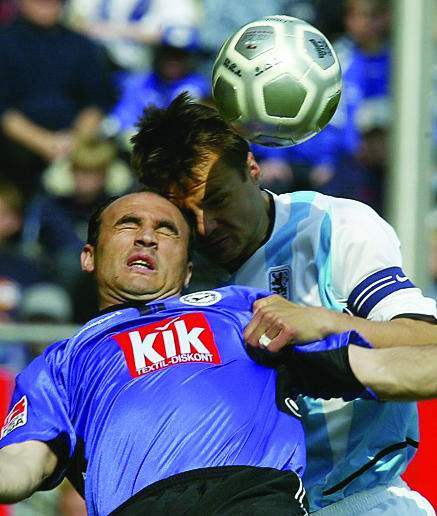

Figure 1.

Credit: TOBIAS HEYER/DPA/EMPICS

Soccer players don't just head the ball; their heads can collide with each other, and players in positions where heading is common are also more likely to have head to head collisions more often. Although uncommon, most concussive injuries seen in soccer derive from such head to head rather than ball to head contact.2

Heading a soccer ball results in head accelerations of less than 10 g (or less than 1000 rad/s2) whereas the minimum values for the development of sport related concussion are 40-60 g (or 3500-5000 rad/s2).3,4 In contrast, head to head contact can generate enough of the forces required to cause brain injury as in any conventional head injury. Recent biomechanical research has found that commercially available soft helmets fail to reduce even this degree of head trauma to a safe level, which implies that these helmets have only a limited protective role in this setting.5

There is no evidence that sustaining several concussions over a sporting career will necessarily result in permanent damage.6 Research on experimental animals provides some supporting evidence against the concept that recurrent concussive injuries alone cause permanent damage. In studies of experimental concussion, animals have been subjected to repeated concussion 20-35 times in a two hour period. Despite the unusually high number of injuries no residual or cumulative effect was shown.7

Can repeated subconcussive trauma such as might be seen in heading the ball cause a cumulative neurological injury in this setting? Although this was indicated by early retrospective studies, more recent studies have not supported this idea.8-10

In a series of retrospective studies including retired Scandinavian soccer players, cognitive deficits were noted.11,12 The results of these studies are flawed, with appreciable methodological problems. These problems include the lack of pre-injury data, selection bias, failure to control for acute head injuries, lack of blinding of observers, and inadequate controls. The authors conclude that the deficits noted in these former soccer players were explained by repetitive trauma such as heading the ball. However, the pattern of deficits seen is equally consistent with alcohol related brain impairment—a confounding variable that was not controlled for.

Matser et al from the Netherlands have also implicated both concussive injury and heading as a cause of neuropsychological impairment in both amateur and professional soccer players.2,13 Reanalysis of the data from these papers, however, indicates that purposeful heading may not be a risk factor for cognitive impairment.14

Prospective controlled studies using clinical examination, neuroimaging, or neuropsychological testing have failed to find any evidence of cognitive impairment in soccer players.8-10

We do not know for certain whether heading the ball in soccer may result in chronic cognitive impairment. It seems unlikely that subconcussive impacts such as seen in head to ball contact will cause chronic neurological injury. Although head to head contact may cause concussive injury, it is both uncommon and unlikely to result in cumulative brain injury. It has been speculated from other sports that particular genotypes may place athletes at heightened risk in association with head trauma, although this is yet to be validated in other studies.15

For football players the avoidance of exposure to brain injury is important, although currently there are few means by which this may be achieved. Most head to head contact is inadvertent, and coaching techniques and visual perception training may help in a few cases but are unlikely to eliminate this problem entirely. Soft shell helmets or head protectors currently do not have the biomechanical capability to prevent concussive trauma and hence cannot be recommended.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Shaw P. Heading the ball killed England striker Jeff Astle. Independent 2002. Nov 12.

- 2.Matser J, Kessels A, Jordan B, Lezak M, Troost J. Chronic traumatic brain injury in professional soccer players. Neurology 1998;51: 791-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naunheim RS, Standeven J, Richter C, Lewis LM. Comparison of impact data in hockey, football, and soccer. J Trauma 2000;48: 938-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntosh A, McCrory P. The dynamics of concussive head impacts in rugby and Australian rules football. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32: 1980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntosh A, McCrory P. Impact energy attenuation performance of football headgear. Br J Sports Med 2000;34: 337-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston K, McCrory P, Mohtadi N, Meeuwisse W. Evidence based review of sport-related concussion—clinical science. Clin J Sport Med 2001;11: 150-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson D. Concussion is completely reversible; an hypothesis. Med Hypotheses 1992;37: 37-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan BD. Acute and chronic brain injury in United States national team soccer players. Am J Sports Med 1996;24: 704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putukian M, Echemendia R, Mackin S. The acute neuropsychological effects of heading in soccer. Clin J Sports Med 2000;10: 104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guskiewicz K, Maskell S, Broglio S, Cantu R, Kirkendall D. No evidence of impaired neurological performance in collegiate soccer players. Am J Sports Med 2002;30: 157-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tysvaer A, Storli O, Bachen N. Soccer injuries to the brain: a neurologic and encephalographic study of former players. Acta Neurol Scand 1989;80: 151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tysvaer AT. Head and neck injuries in soccer. Impact of minor head trauma. Sports Med 1992;14: 200-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matser J, Kessels A, Lezak M, Troost J. A dose-response relation of headers and concussions with cognitive impairment in professional soccer players. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2001;23: 770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkendall D, Garrett W. Heading in soccer: Integral skill or grounds for cognitive dysfunction. J Athletic Training 2001;36: 328-33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan BD, Relkin NR, Ravdin LD, Jacobs AR, Bennett A, Gandy S. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 associated with chronic traumatic brain injury in boxing. J Am Med Assoc 1997;278: 136-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]