ABSTRACT

Microbial community adaptability to pH stress plays a crucial role in biofilm formation. This study aims to investigate the regulatory mechanisms of exogenous putrescine on pH stress, as well as enhance understanding and application for the technical measures and molecular mechanisms of biofilm regulation. Findings demonstrated that exogenous putrescine acted as a switch-like distributor affecting microorganism pH stress, thus promoting biofilm formation under acid conditions while inhibiting it under alkaline conditions. As pH decreases, the protonation degree of putrescine increases, making putrescine more readily adsorbed. Protonated exogenous putrescine could increase cell membrane permeability, facilitating its entry into the cell. Subsequently, putrescine consumed intracellular H+ by enhancing the glutamate-based acid resistance strategy and the γ-aminobutyric acid metabolic pathway to reduce acid stress on cells. Furthermore, putrescine stimulated ATPase expression, allowing for better utilization of energy in H+ transmembrane transport and enhancing oxidative phosphorylation activity. However, putrescine protonation was limited under alkaline conditions, and the intracellular H+ consumption further exacerbated alkali stress and inhibits cellular metabolic activity. Exogenous putrescine promoted the proportion of fungi and acidophilic bacteria under acidic stress and alkaliphilic bacteria under alkali stress while having a limited impact on fungi in alkaline biofilms. Increasing Bdellovibrio under alkali conditions with putrescine further aggravated the biofilm decomposition. This research shed light on the unclear relationship between exogenous putrescine, environmental pH, and pH stress adaptability of biofilm. By judiciously employing putrescine, biofilm formation could be controlled to meet the needs of engineering applications with different characteristics.

IMPORTANCE

The objective of this study is to unravel the regulatory mechanism by which exogenous putrescine influences biofilm pH stress adaptability and understand the role of environmental pH in this intricate process. Our findings revealed that exogenous putrescine functioned as a switch-like distributor affecting the pH stress adaptability of biofilm-based activated sludge, which promoted energy utilization for growth and reproduction processes under acidic conditions while limiting biofilm development to conserve energy under alkaline conditions. This study not only clarified the previously ambiguous relationship between exogenous putrescine, environmental pH, and biofilm pH stress adaptability but also offered fresh insights into enhancing biofilm stability within extreme environments. Through the modulation of energy utilization, exerting control over biofilm growth and achieving more effective engineering goals could be possible.

KEYWORDS: biofilm formation, pH stress adaptability, exogenous putrescine, tolerance response, resistance mechanism

INTRODUCTION

In a hybrid system, biofilms serve as a nursery in which dispersed planktonic cells can attach to the substratum to initiate biofilm formation, where pH plays a critical role, affecting not only biofilm spatial structure but also bacterial activity (1). The optimal pH for different biofilm systems varies and depends on the available compounds and microbial characteristics (2). In practical bioreactor operation, pH fluctuations are a common phenomenon caused by changes in operating conditions or the accumulation of metabolic products, which lead to adverse effects on biofilm growth (3). These effects include damage to biofilm stability and structure, inhibition of substrate capture and transmembrane transport, interference with intracellular electron transfer and protease activity, and alteration of microbial energy metabolism (4, 5).

Biofilm pH fluctuation is a common issue that affects the microorganism community and can be influenced by various factors. For one thing, processes in industries, such as metallurgical, electroplating, chemical pharmaceutical, and biological fermentation can generate large amounts of acidic/alkaline wastes, which negatively impact subsequent biological treatment inevitably (6). For another, pollutant biotreatment processes can lead to acid accumulation, resulting in reactor acidification. For example, the HCl/H2SO4 release in the biofiltration process of chlorinated/sulfur-containing volatile organic compounds, as well as the organic acid accumulation in the organic compound hydrolytic acidification process both significantly reduced microorganism activities (7, 8). Currently, pH regulation is achieved by adding limestone, plant ash, dolomite, etc. However, these methods need to strictly control the ratio and dosage according to the actual situation; otherwise, it will produce various disadvantages, including poor economic returns, causing secondary pollution and impairment of functional microbial activity (9, 10). In contrast, to enhance the resistance to pH changes, increasing the pH stress adaptability of microorganisms in biofilm may be a more effective method.

To counteract the adverse effects of environment acidification or alkalinization, microorganisms have evolved multiple tolerance response strategies. Bacteria could transform unsaturated fatty acids into saturated fatty acids, thus limiting the proton diffusion to enhance acid or alkaline tolerance (11). For acid stress, acid resistance (AR) strategies enable cells to maintain growth and metabolic activity in acidic environments while preserving biofilm integrity and function. These strategies involve specific amino acid transporters on the cell membrane and corresponding intracellular amino acid dehydratase/deaminase metabolism to consume H+ (12). Conversely, microbes respond to alkali stress primarily by limiting proton outflow and promoting proton influx. Alkaliphiles employ ion transport-based mechanisms to maintain cellular pH homeostasis, with monovalent antiporters facilitating proton entry by exchanging sodium or potassium ions outside the cell (13). Furthermore, microorganisms form biofilms through chemotactic gene expression, extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) secretion, and intracellular/intercellular signaling (14). Biofilm has the characteristics of “protective clothing,” which makes the microorganisms in the biofilm more resistant to pH stress than in sludge flocs (15). These strategies offer crucial protection for cell survival in pH-stress environments.

In recent years, putrescine has been shown to benefit microorganisms (16). Putrescine could improve microbial growth and metabolic activity, benefiting from its involvement in a variety of cellular processes, including cell growth and division, gene regulation, and stress responses (17). Some studies have highlighted the distinct influence of exogenous putrescine on pure biofilm growth (promoting or inhibiting or unobvious effecting) (18–20). Most basic growth pathways are generally universal and conserved for many microorganisms (21). Therefore, it has more practical value to explore putrescine conservative functions in a hybrid system. In addition, microbial substrate metabolism processes (such as solution capture, transmembrane transport, and metabolic reactions) can be significantly affected by pH to change substrate charge state, transmembrane proton dynamics, and intracellular metabolic pathways (22, 23). Therefore, pH condition is a crucial factor that influences the biofilm response to exogenous putrescine. However, reports are lacking on pH effects on the uptake, metabolism, and utilization of exogenous putrescine in complex community systems. Clarifying the mechanism of exogenous putrescine in different pH is the precursor condition for rational utilization of putrescine to achieve better engineering goals.

This study aims to provide a theoretical basis for the rational use of putrescine in complex biofilm-based systems. Therefore, the regulatory mechanism of exogenous putrescine on pH stress adaptability and the role of environmental pH in this process have been clarified. In this study, we characterized the exogenous putrescine effects on the formation and metabolic activity of mixed biofilm at different pHs. Then, we evaluated the effect of pH on the exogenous putrescine transmembrane transport by EPS, membrane permeability, and intracellular putrescine levels. To reveal the conserved role of putrescine on microorganisms, we examined the intracellular pH and key metabolic pathways of putrescine metabolism. Furthermore, the oxidative phosphorylation activity was measured to indicate the effect of putrescine on energy utilization. In addition, metagenomic analysis revealed key response genes during exogenous putrescine absorption and metabolism. Experimental results identified the regulatory effects of exogenous putrescine on key processes, such as growth and reproduction, microbial pH adaptation, and oxidative phosphorylation, as well as their dependence on pH. This research revealed the essential mechanism of exogenous putrescine adjusting on pH stress adaptability. It would enhance our understanding and application of the technical measures and molecular mechanisms of biofilm regulation. By employing putrescine judiciously, the adverse effects of pH stress on biofilms could be reduced, thereby improving their performance in extreme acid–base environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biofilm formation test

The dynamic biofilm formation assay was based on shaking flask culture with constant vortexing. The activated sludge (AS) was taken from the secondary sedimentation tank of the Tianjin Jinnan Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP), whose core process was the anaerobic–anoxic–oxic treatment (detailed information about this WWTP and AS characteristics were shown in Text S1). The biofilm formation experiment was set up as described in our previous studies (24, 25). Wooden boards (length, width, and height are 10, 2, and 1 cm, respectively) were used to measure the biofilm formation as a packing material. The accumulation and formation rates of biofilm were measured by removing the board and weighing it at intervals (Text S2). Experiments were divided into three pairs of groups, and each group was cultured in an incubator with or without putrescine (Acid group: Acid-Con Vs Acid-Put, Isoelectric point group: pl-Con Vs pl-Put, and Alkali group: Alkali-Con Vs Alkali-Put). The pH was adjusted by NaOH and H2SO4 solution every 4–8 h to keep it stable in a certain range (Acid group: pH 3–4; Isoelectric point group: pH 5–6; Alkali group: pH 8–9). The rotating speed of the shaking table was set to 120 rpm, 28°C. Each experiment was repeated thrice. The static biofilm formation assay was based on a 96-well plate method described elsewhere with slight modifications (26). The detailed information was shown in Text S3.

Microbial characteristic analysis

Microbial viability, microbial size, membrane permeability, metabolism difference, and EPS secretion were detected to determine the influence of exogenous putrescine. The methods of extracting cells and EPS from biofilm were shown in Text S4. Both were quantified by the CytoFLEX flow cytometer at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm (27). All measurements were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and in triplicates. The test details were shown in Text S5. The metabolism analysis was determined using a Biolog-EcoPlate, which was shown in Text S5. Protein (PN) and polysaccharide (PS) as the principal components of EPS secreted by microorganisms were determined by the Lowry method and phenol sulfuric acid method, respectively (28). Bovine serum albumin (Solarbio Co.Ltd., China) and glucose (Yuanli Co.Ltd., China) were used as standards. Each experiment was repeated thrice.

Intracellular key content analysis

Microbial intracellular total nitrogen (TN), H+ and OH- relative concentration, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), guanosine triphosphate (GTP), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentrations were detected to determine the influence of exogenous putrescine. The method of extracting intracellular contents from cells was shown in Text S6. Due to metabolic transformations that occur upon putrescine entry, it was necessary to incorporate putrescine into preformed biofilms to investigate its uptake. Initially, biofilms were cultured for 48 h without putrescine addition. Then, putrescine was added into biofilms and further incubated for 4 h (29). Taking into account putrescine metabolism, we characterized putrescine uptake by intracellular TN levels. TN was tested by a total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu Co.Ltd., Japan). Filtered cells were centrifuged and transferred to 5-mL ultrapure water for ultrasonic dispersion to release intracellular H+. The pH was measured by a pH detector, and the concentration of H+ was calculated. The H+ ratio of putrescine treatment to the control group could indicate the relative content of intracellular H+. BBcellProbe P01 Kit (BestBio Co.Ltd., China) was used to qualitatively analyze intracellular OH- signal (Text S7). The indicators of oxidative phosphorylation activity (ATP and ADP levels), tricarboxylic acid cycle activity (GTP level), AR strategy, and putrescine metabolism activity (GABA level) were measured using ELISA kit (Jingmei Biotechnology Co.Ltd., China). The details were shown in Text S8.

DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA was extracted from biofilm samples using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Text S9). DNA degradation degree, potential contamination, and DNA concentration were measured using Agilent 5400 (Agilent Technologies Co.Ltd., USA). The DNA sample was fragmented by sonication to a size of 350 bp, then DNA fragments were end-polished, A-tailed, and ligated with the full-length adaptor for Illumina sequencing with further polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. Finally, PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system), and libraries were analyzed for size distribution by using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Co.Ltd., USA) and quantified using real-time PCR. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform, and paired-end reads were generated.

Bioinformatics and data analysis

The raw data of bacteria and fungi in biofilm samples were obtained by metagenomic sequencing using the Illumina Novaseq high-throughput sequencing platform. The details to ensure the data reliability was shown in Text S10. FastQC was used to detect the rationality and effect of quality control (30). Kraken2 and the self-build microbial database (sequences belonging to bacteria, fungi, and archaea were screened from the NT nucleic acid database and RefSeq whole genome database of NCBI) were used to identify the species contained in the samples, and then Bracken was used to predict the actual relative abundance of species in the samples. The clean reads after quality control and de-host were used to be blasted to the database (Uniref90) using Humann2 software (based on Diamond), and the annotation information and relative abundance table from each functional database were obtained according to the corresponding relationship between Uniref90 ID and each database. Specific annotated information for gene numbers in the KEGG database covered in this article was shown in Table S1. Based on the species and functional abundance tables, abundance clustering analysis and sample differences analysis could be performed (31).

Statistical analysis

The statistic differences test in each group was analyzed using Student’s t-test using SPSS (version 19.0; SPSS Co.Ltd., USA), and P < 0.05 was considered to be the threshold of statistical significance. The standard deviations (presented by error bars), curve fittings, and confidence intervals (CIs) were completed in Origin (version 10.0; OriginLab Co.Ltd., USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Putrescine affects biofilm formation and microbial activity

Figure 1a and Fig. S1 show the pH-dependent effect of putrescine on biofilm formation. When the pH solution was <5.5, the promoting effect on biofilm formation became more pronounced with increasing putrescine concentration (P < 0.05). However, at around pH 5.5, the biofilm did not exhibit a significant response to putrescine (P > 0.05). Interestingly, when the pH exceeded 5.5, putrescine inhibited biofilm formation (P < 0.05). This observation might be attributed to the isoelectric point (pl) of most bacteria, which occurs at pH 5.5, resulting in surface charge equilibrium with the surrounding ion concentration (32). To investigate the effects of exogenous putrescine, we categorized the pH ranges into three groups: acid, pl, and alkali. Additionally, to eliminate the influence of putrescine as a carbon source, we added an equal carbon concentration of glucose under the same experimental conditions, and no significant difference was found (P > 0.05) (Fig. S2). Figure S3 explored the response of biofilm formation to exogenous putrescine during static cultivation. The results indicated that putrescine had a non-significant effect at the pl under static conditions (P > 0.05). However, under acid conditions, biofilm production increased by 102%, whereas under alkali conditions, it decreased by 37%, and the results were significant (P < 0.05). Moreover, we monitored the growth curve of biofilms, which revealed no significant impact of exogenous putrescine on biofilm formation when the solution pH was maintained around the pl (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1d). Compared with the control group, the treatment group exhibited higher maximum biofilm biomass and formation rates under acidic conditions (P < 0.01) but a lower maximum biofilm biomass under alkali conditions significantly (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1c and e). Biofilm formation is a complex and dynamic process. Many factors, including EPS content, growth and reproduction of microorganisms, and adhesion strength to the carrier, can influence biomass accumulation in a stressful environment (15). In addition, the tendency of biofilm biomass is the same as that of abilities to resist environmental stresses (33). Therefore, the adaptability of exogenous putrescine to pH stress shows a variation tendency following pH change.

Fig 1.

Biomass and microbial activity response to exogenous putrescine. (a) The dynamic biomass density at 48 h under various putrescine concentrations. Data of the y-axis represent the difference in biofilm mass calculated by subtracting the control group biofilm mass from the treatment group under the same operating pH. (b) The life cycles of microorganisms in the biofilm at 48 h (Alive cells: Intact and Early apoptosis; Dead cells: Late apoptosis and Broken). (c)–(e) The dynamic biofilm growth curve. Acid: pH 3–4. pl: pH 5–6. Alkali: pH 8–9. Ribbons around fitting curves represent the 95% confidence intervals. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the data set. P-value is calculated using t test, significance level, P < 0.05(*), P < 0.01(**), P < 0.001(***).

Adaptation of microorganisms to pH stress is closely linked to its viability (34). Therefore, we evaluated the life cycles of cells within the biofilms. Figure 1b and Fig. S4 show that the proportion of intact cells increased by 125% under acidic conditions after putrescine addition compared with the control group. Conversely, the proportion of intact cells decreased by 36% under alkali conditions. Consistent with previous reports, a high percentage of dead cells (50%-80%) has been detected in biofilms (35). It might be due to dead cells and their releases involved in the formation of conditioning (down-layer) film, which played great significance for biofilm skeleton construction and provided sites for up-layer alive cells (20%-50%) colonization (36). Therefore, exogenous putrescine promoted biofilm development under acidic conditions (up-layer percentage increases 105%, P < 0.01) and inhibited it under alkaline conditions (up-layer percentage decreases 48%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1b).

The metabolic utilization percentages of seven types of carbon sources at different pHs were shown in Fig. S5, indicating that exogenous putrescine might affect the composition of microbial energy metabolism (37). We mainly analyzed the metabolic differences in which the utilization rate of carbon sources tended to be stable after 24 h (Fig. S5). When putrescine was added, aliphatic substance (alcohols and esters) metabolism was enhanced (P < 0.05) (Fig. S5). It might be due to putrescine as a small molecular aliphatic compound stimulating non-specific interrelated enzyme secretion (38). Amino acids and amines play an important role in inhibiting cell acidification (39, 40), and we found that exogenous putrescine promoted amino acids metabolism in the acid group (P < 0.05) but had little effect in alkaline conditions (P > 0.05) (Fig. S5). Glycolysis as the ATP main source is closely related to sugar consumption and adjusted by exogenous putrescine (41). Figure S5 showed sugar compound utilization changed from enhancement to inhibition with the increase of pH after adding putrescine (both acid and alkali groups, P < 0.05), which would directly affect energy utilization efficiency.

These results showed a phenomenon that exogenous putrescine presented switch-like effects on the pH stress adaptability process at different pH conditions, which had been rarely reported previously. This finding provided a new perspective to explain the conflicting findings regarding the impact of exogenous putrescine on biofilms.

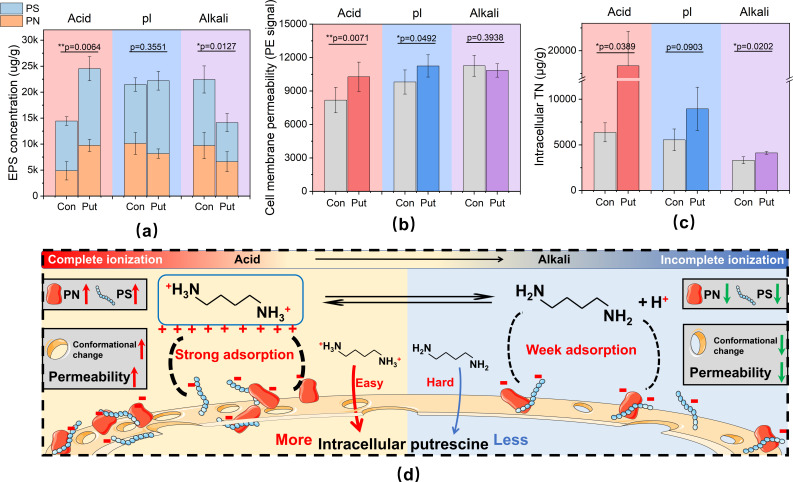

Exogenous putrescine transmembrane transport

The adhesive polymeric matrix attached to the microbial surface is primarily composed of negatively charged PN and hydrophilic PS (42). EPS is continuously synthesized and secreted during cell growth, forming a stable structure that plays crucial roles in environmental stress protection, nutrient absorption, and storage (43, 44). In this regard, we observed that the concentrations of PN and PS in the biofilm increased by 99% and 54%, respectively under acidic conditions compared with the control group, whereas these indicators decreased under alkaline conditions (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, putrescine can act as a proton acceptor due to its two amino groups containing lone pair electrons. The protonation degree of putrescine decreases with increasing pH (45). The negatively charged nucleic acids and PN within the EPS strongly adsorb to protonated putrescine through electrostatic forces, facilitating their entry into the biofilm (46). Additionally, hydrophilic protonated putrescine can form hydrogen bonds with PS and water molecules, leading to the formation of a hydrogen bond network that promotes the aggregation of hydrophilic putrescine (47). The tight binding between putrescine and EPS in acidic environments benefits the absorption of exogenous putrescine.

Fig 2.

Biofilm attachment and absorption exogenous putrescine. (a) EPS concentration consists of PN and PS at 24-h cultivation. (b) Cell membrane permeability level at 24-h cultivation. (c) Intracellular total nitrogen concentration at 4-h absorption. (d) Schematic diagram of adsorption and absorption differential mechanisms of exogenous putrescine at different pHs. Acid: pH 3–4. pl: pH 5–6. Alkali: pH 8–9. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the data set. P-value is calculated using t test, significance level, P < 0.05(*), P < 0.01(**), P < 0.001(***).

Our findings indicated that cell membrane permeability significantly increased under acid and pl conditions compared with the control group (P < 0.05), whereas no significant difference was observed under alkaline conditions (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2b). The phospholipid bilayer forms the basic framework of the cell membrane, and the phospholipid molecules on the cell membrane surface carry negative charges, making them prone to electrostatic interactions with protonated putrescine (48). Moreover, the oxygen atoms within the phospholipid molecules can act as hydrogen bond acceptors, facilitating their interaction with hydrophilic protonated putrescine (49). The morphological changes of microbial cell membranes further enhance the absorption of polyamines in acidic conditions.

Considering the metabolic transformation of putrescine in cells, we examined the intracellular TN levels to indicate exogenous putrescine absorption. As shown in Fig. 2c, intracellular TN increased across a wide pH range. Notably, the increase in intracellular TN became more intense as the pH decreased (no significance was found in the pl group, P > 0.05). Overall, the differential interaction of exogenous putrescine with the biofilm in different pH conditions is illustrated in Fig. 2d. In acidic solutions, exogenous putrescine promoted EPS production, and the accumulated EPS, in turn, captured protonated putrescine. The interaction between protonated putrescine and microbial cell membranes further enhanced putrescine absorption. Microorganisms prefer direct absorption of putrescine from the environment over energy-consuming endogenous synthesis, which is advantageous for conserving energy in nutrient-limited environments (50).

Putrescine decreases microbial intracellular H+ concentration

Microorganisms possess the capability to maintain internal homeostasis, resulting in a relatively stable intracellular pH (pHi) despite harsh external environments (51). The uptake of exogenous putrescine can induce changes in intracellular H+ concentration through processes, such as ionization, hydrolysis, metabolism, or regulation, as shown in Fig. 3a through c. The left histograms demonstrated a significant right shift in the positive data curve, indicating a higher number of cells with stronger OH- signal intensity across a wide pH range compared with the control groups. The right bar charted depict the average signal intensity of intracellular OH- in the biofilms. Additionally, we measured the relative content of intracellular H+ in putrescine-stimulated biofilms (Fig. S6 and S7). Compared with the control group, the intracellular H+ concentration decreased by 74%, 68%, and 32% under the influence of putrescine in acid, pl, and alkali conditions, respectively. This suggested that putrescine could increase the pHi of microorganisms over a broader pH range (both acid and alkali groups, P < 0.05).

Fig 3.

Exogenous putrescine decreased microorganism intracellular H+ concentration in biofilm. (a–c) Intracellular OH- concentration histogram of microorganisms at 48-h cultivation (left). Average intracellular OH- concentration signal strength of microorganisms (right). (d) Intracellular GABA concentration. (e) Glutamate metabolism capacity. (f) Intracellular GTP concentration. (g) Major pHi increasing mechanisms of microorganisms affected by exogenous putrescine at different pHs. Acid: pH 3–4. pl: pH 5–6. Alkali: pH 8–9. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the data set. P-value is calculated using t test, significance level, P < 0.05(*), P < 0.01(**), P < 0.001(***).

Putrescine undergoes oxidative metabolism through a series of diamine oxidases (DAOs). GABA as a key intermediate in putrescine metabolism, plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular acid tolerance through proton exchange (52). Figure. 3d demonstrates a significant increase in intracellular GABA content upon the putrescine addition (P < 0.05). Notably, the elevation of GABA content was more pronounced in acidic conditions compared with alkaline conditions, suggesting that acidic environments might be more conducive to endogenous GABA synthesis (53). Studies have shown that putrescine could enhance the expression of glutamate decarboxylase by inhibiting cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) synthesis, leading to increased GABA production and improved acid tolerance (54, 55). We observed that exogenous putrescine enhanced the utilization of glutamate under acidic conditions (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3e). Therefore, putrescine and GABA, as intermediates of the decarboxylase system, exhibited close functional and metabolic relationships. Furthermore, GABA could serve as a nutrient and enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle under the catalysis of 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase, promoting microbial growth and reproduction and directly generating GTP (56). We measured the GTP content under the exogenous putrescine influence (Fig. 3f). Compared with the control group, the GTP content increased by 15% under acidic conditions. Thus, the GABA potential metabolism for the tricarboxylic acid cycle was enhanced in synergy with putrescine and low pH (P < 0.01). It was worth noting that GTP content decreased under alkaline conditions (P < 0.01), which further confirmed the inhibitory effect of putrescine on pH stress adaptability compared with acidic conditions.

Mechanisms by which exogenous putrescine affected intracellular processes vary under different pH conditions (Fig. 3g). In acidic conditions, during the metabolic process of putrescine, the generated NH3 bind with intracellular free H+ to form NH4+, thereby consuming intracellular H+. Moreover, putrescine enhanced the synthesis of GABA through the glutamine pathway and the glutamate cycle under acidic conditions (56). This process not only promoted GABA production but also helped alleviate intracellular H+ pressure. In alkaline conditions, partially ionized putrescine sequestered cytoplasmic H+ through further ionization, leading to an increase in cytoplasmic OH- concentration. Intracellular H+ concentration was closely related to microbial growth and metabolism, directly influencing their ability to grow, metabolize, and adapt to the environment. Therefore, exogenous putrescine alleviated cytoplasmic acidification by consuming intracellular protons in acidic environments, while causing cytoplasmic alkalinization by accumulating OH-, resulting in profound differences in microbial growth and metabolism.

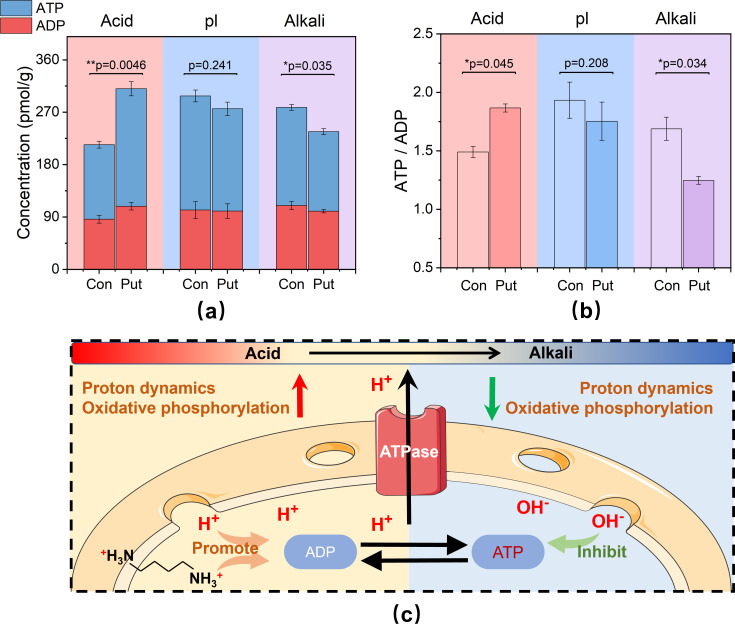

Putrescine affects oxidative phosphorylation activity

Microbial growth and reproduction are driven by oxidative phosphorylation, which significantly impacts biofilm pH stress adaptability. ATP serves as the direct energy currency of microbial metabolism, and its dynamic balance directly influences microbial metabolic activity (57). Figure 4a shows that under acidic conditions, both intracellular ATP and ADP concentrations are significantly increased by 58% and 26%, respectively, while they decrease under alkaline conditions. Oxidative phosphorylation is the primary mechanism for microbial ATP production, and the conversion between ATP and ADP occurs rapidly, maintaining a dynamic equilibrium. The ratio of ATP to ADP is often used to indicate the activity of oxidative phosphorylation (58). As shown in Fig. 4b, the level of oxidative phosphorylation activity increased under acidic conditions, suggesting sufficient energy availability inside the cell, and cells tended to consume ATP for growth and assimilatory metabolism (P < 0.05). Conversely, the decreased level under alkali conditions indicated that intracellular energy availability was inhibited, and cells tended to prioritize ATP synthesis and energy accumulation over metabolic growth (P < 0.05).

Fig 4.

Exogenous putrescine affects microorganism oxidative phosphorylation activity. (a) Biofilm ATP and ADP dynamic equilibrium concentrations at 48-h cultivation. (b) Average oxidative phosphorylation activity of biofilms at 48-h cultivation. (c) Mechanism of exogenous putrescine effects on oxidative phosphorylation activity at different pHs. Acid: pH 3–4. pl: pH 5–6. Alkali: pH 8–9. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the data set. P-value is calculated using t test, significance level, P < 0.05(*), P < 0.01(**), P < 0.001(***).

Exogenous putrescine might regulate microbial oxidative phosphorylation by influencing pHi and H+ transport activity (Fig. 4c). Putrescine can interact with ion channels or transport proteins on the cell membrane, altering their conformation or activity and increasing the H+ transport rate (59). Researches have shown that in acidic environments, putrescine could stimulate the expression of ATPase, enabling efficient utilization of the electron potential generated by H+ transmembrane transport to convert ADP and inorganic phosphate into ATP (60, 61). However, in alkaline conditions, the increasing pHi might inhibit ATPase activity and proton concentration difference, thereby reducing the proton gradient across the membrane and decreasing the rate of oxidative phosphorylation (62). Pérez-Rodríguez et al. (63) demonstrated that low pH induced a bistable transition in Ustilago maydis, and the addition of exogenous putrescine under acidic conditions promoted the expression of cell cycle and oxidative phosphorylation-related genes, ensuring hyphal growth. Conversely, Li and Liu (64) found that excessive putrescine inhibited the oxidative phosphorylation activity of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Our study suggested that this differential impact might be attributed to environmental pH. Similarly, Rutherford et al. (65) observed a synergistic upregulation of putrescine and oxidative phosphorylation activity in Escherichia coli under acidic stress induced by n-butanol.

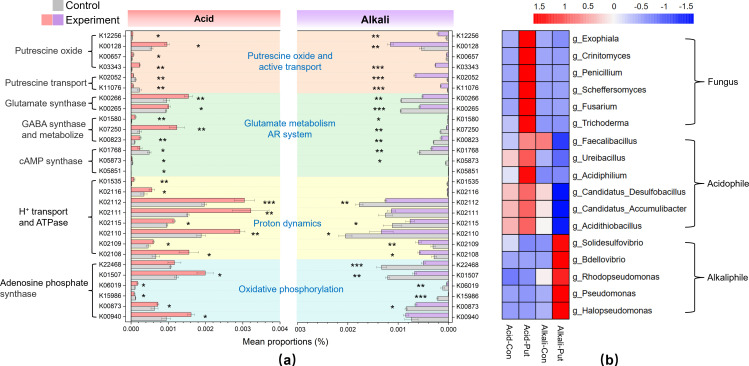

Putrescine affects functional genes, acidophilic, and alkalophilic abundance

We discovered that exogenous putrescine, in conjunction with pH, synergistically influenced the abundance of genes related to putrescine metabolism, AR strategy, proton transport, and oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 5a; Table S1). Differences in the gene abundance of putrescine transport ATPases suggested that more energy was required to absorb putrescine in alkaline conditions (e.g., K02052 and K11076) (P < 0.001). The glutamine–glutamate–GABA metabolic pathway as an important AR strategy ensured stable proton conditions within the microbial intracellular environment (66, 67). We found that exogenous putrescine significantly upregulated genes associated with the glutamine–glutamate–GABA metabolic pathway under acidic stress, but downregulated them under alkaline stress (e.g., K00265, K00266, K01580, K07250, and K00823) (P < 0.05). Additionally, genes related to cAMP synthesis were significantly downregulated (e.g., K01768, K05873, and K05851) (P < 0.05). The enhanced downstream metabolism of GABA promotes ATP production and enhanced microbial metabolic activity.

Fig 5.

Functional genes and microbial diversity analysis. (a) Effects of exogenous putrescine on genes relative abundance about putrescine oxide and active transport, glutamate metabolism AR system, proton dynamics, and oxidative phosphorylation. (b) Changes of fungus, acidophile, and alkaliphile under exogenous putrescine and pH influence. Acid: pH 3 ~ 4. Alkali: pH 8 ~ 9. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the data set. P-value is calculated by t.test, significance level P < 0.05(*), P < 0.01(**), P < 0.001(***).

Compared with alkaline stress, the significant upregulation of proton pump-related genes under acid stress suggested enhanced intracellular proton transfer and transmembrane transport (e.g., K02108, K02109, K02110, and K02115) (P < 0.05). ATP synthase proteins utilize the electron potential generated by H+ translocation to catalyze ATP synthesis (68, 69). Genes involved in this process (e.g., H+ channel gene K01535, ATP synthesis genes K02111, K02112, and K02116) were upregulated under acidic conditions and downregulated under alkaline conditions. Additionally, genes associated with ADP syntheses, such as polyphosphate kinase, inorganic pyrophosphatase, and pyrophosphatase, which serve as precursors for ATP synthesis, were significantly upregulated under acid conditions (e.g., K22468, K01507, K06019, and K15986) (P < 0.05). Furthermore, we observed synchronized upregulation of the pyrimidine metabolism genes K00873 and K00940, which catalyzed the interconversion of ATP and ADP (P < 0.05). This further enhanced the energy utilization efficiency of biofilm, ensuring that cells could flexibly regulate energy supply according to change in energy demand.

Moreover, we observed an increase in microbial size when treated with exogenous putrescine under acidic conditions (Fig. S8). The proportion of cells with forward scatter signals greater than 105 increased by 120% under acidic conditions, whereas no changes were observed under pl and alkali conditions. This might suggest that exogenous putrescine could enhance fungus proportion in the acidic biofilm, whereas the impact on fungi was limited in alkaline biofilms (Fig. 5b). Extensive researches have demonstrated that most Ascomycota fungi possess strong acidic adaptation abilities (70). Genera belonging to Ascomycota, such as Exophiala, Penicillium, Scheffersomyces, Fusarium, and Trichoderma, have conserved GABA metabolic pathways and can utilize glutamate metabolism to cope with extremely acidic environments (71–73). Moreover, these Ascomycota fungi have mitochondria in their cytoplasm, making them more susceptible to accelerated proton transport and electron transfer caused by putrescine, thereby increasing the rate of oxidative phosphorylation (70).

Cluster analysis also revealed that exogenous putrescine might enhance the survival capacity of acidophilic bacteria under acid stress (Fig. 5b). Members of Acidiphilum, Candidatus Desulfobacillus, and Acidithiobacillus, which are extracted from acidic mining sites and possess a strong potential for sulfide removal under acid conditions, exhibit a highly conserved AR system dependent on glutamate. These bacteria demonstrate high metabolic activity when the pH is <4 (14, 74). However, the abundance of acidophilic bacteria and fungi decreased under alkaline stress with putrescine addition, which might be attributed to the high sensitivity of acidophilic enzymes to H+. Interestingly, the increased intracellular OH- stimulated the proliferation of alkaliphilic bacteria (Fig. 5b). Genera, such as Bdellovibrio, Rhodopseudomonas, and Pseudomonas, exhibit higher activity under alkaline conditions (75, 76). Notably, members of Bdellovibrio as small predatory alkaliphilic bacteria can prevent the formation of biofilms and disrupt established biofilms, which is harmful to pH stress resistance (77).

Engineering application prospect of exogenous putrescine

Maintaining the activity of functional microorganisms plays a critical role in realizing biofilm-based reactor operation stably. However, keeping optimal conditions continuously requires complex manipulation and tends to enable the growth of undesired function microorganisms (78). Biofilm-based reactors have the advantage of dense functional areas, and techniques to control their properties by adding exogenous substances have been widely reported. For example, exogenous hydrolase increased the methane production of anaerobic membrane bioreactor (79). Iversen et al. improved activated sludge respiration and nutrient removal in membrane bioreactor by adding membrane flux enhancers (80). Similarly, Jia et al. enhanced the removal efficiency of H2S by adding organic matter in an extremely acidic bio-trickling filter (78). In addition, exogenous signal molecules have been widely used to control biofilm fouling (81). Our study provided an approach to enhance microbial metabolic activity under acidic conditions to resist acid stress, which showed the potential applications in many biofilm-based acidification fields, such as resisting the damage of biofilm self-acidification during dechlorination or desulfurization and growing biofilms for the pretreatment of acidic wastes. Exogenous putrescine could promote biofilm growth under acidic stress, resulting in less damage to the biofilm, a wide range of applications, and no secondary pollution compared with traditional acid stress mitigation methods. In addition, this study also showed that exogenous putrescine inhibited microbial energy metabolism and restricted biofilm growth in an alkaline environment. As a result, it had the potential to limit biofilm formation and diffusion in alkalization situations (such as alkali sewage pipelines). Although pure chemicals were used in this study, the positive effect of low-dose putrescine suggested the economic benefits of its application. Furthermore, putrescine synthesis and secretion genes are conserved in microorganisms, and stimulating putrescine production or co-culturing the biofilm with putrescine-producing bacteria may be a more effective method for future applications (82). However, practical applications still require consideration of potential issues, such as the possible blockage caused by excessive accumulation of biofilm under acidic stress.

Conclusion

Overall, exogenous putrescine functions as a switch-like distributor affecting the pH stress adaptability of biofilm-based activated sludge, which promoted energy utilization for growth and reproduction processes under acidic conditions, while limiting biofilm development to conserve energy under alkaline conditions. This was achieved through several mechanisms, including enhanced protonation degree for easier biofilm adsorption, transmembrane transport of putrescine, microbial glutamate-based adaptive AR strategy, GABA metabolic pathway, and oxidative phosphorylation activity. These effects were more pronounced when putrescine was added under acidic conditions, whereas they were limited in alkaline conditions. Additionally, exogenous putrescine stimulated the proportion of fungi and acidophilic bacteria under acidic stress and alkaliphile bacteria under alkali stress conditions, whereas the impact on fungi in alkaline biofilms was limited. Increasing Bdellovibrio under alkaline conditions with putrescine further aggravated biofilm decomposition. The findings of our study shed light on the previously unclear relationship between exogenous putrescine, environmental pH, and pH stress adaptability of biofilm. Moreover, it provided new insights into enhancing biofilm stability in extreme environments. By modulating energy utilization, it became feasible to control biofilm pH stress adaptability and meet engineering application needs with different characteristics. For example, it could be applied to biofilm rapid formation under acid stress, but limited at alkaline stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52170114 and 21961160743), Projects of Science and Technology, Tianjin (21JCJQJC00080), and Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province-Key Project (B2021208033).

Contributor Information

Can Wang, Email: wangcan@tju.edu.cn.

Arpita Bose, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The raw reads can be obtained in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank (accession number PRJNA992974).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00569-24.

Text S1 to S10, Fig. S1 to S8, and Table S1.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aqeel H, Weissbrodt DG, Cerruti M, Wolfaardt GM, Wilén B-M, Liss SN. 2019. Drivers of bioaggregation from flocs to biofilms and granular sludge. Environ Sci Water Res Technol 5:2072–2089. doi: 10.1039/C9EW00450E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lowe SE, Jain MK, Zeikus JG. 1993. Biology, ecology, and biotechnological applications of anaerobic bacteria adapted to environmental stresses in temperature, pH, salinity, or substrates. Microbiol Rev 57:451–509. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.451-509.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garnett JA, Matthews S. 2012. Interactions in bacterial biofilm development: a structural perspective. Curr Protein Pept Sci 13:739–755. doi: 10.2174/138920312804871166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang Y, Li M, Zheng X, Ma H, Nerenberg R, Chai H. 2022. Extracellular DNA plays a key role in the structural stability of sulfide-based denitrifying biofilms. Sci Total Environ 838:155822. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cotter PD, Hill C. 2003. Surviving the acid test: responses of gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:429–453. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.3.429-453.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vijayaraghavan K, Yun Y-S. 2008. Bacterial biosorbents and biosorption. Biotechnol Adv 26:266–291. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Han M-F, Wang C, Yang N-Y, Hu X-R, Wang Y-C, Duan E-H, Ren H-W, Hsi H-C, Deng J-G. 2020. Performance enhancement of a biofilter with pH buffering and filter bed supporting material in removal of chlorobenzene. Chemosphere 251:126358. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Zang B, Gong X, Liu Y, Li G. 2017. Effects of pH buffering agents on the anaerobic hydrolysis acidification stage of kitchen waste. Waste Manag 68:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daraz U, Li Y, Ahmad I, Iqbal R, Ditta A. 2023. Remediation technologies for acid mine drainage: recent trends and future perspectives. Chemosphere 311:137089. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong J. 2000. Effects of lime addition on sewage sludge composting process. Water Res 34:3691–3698. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00116-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu Y, Zhao Z, Tong W, Ding Y, Liu B, Shi Y, Wang J, Sun S, Liu M, Wang Y, Qi Q, Xian M, Zhao G. 2020. An acid-tolerance response system protecting exponentially growing Escherichia coli. Nat Commun 11:1496. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15350-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lund P, Tramonti A, De Biase D. 2014. Coping with low pH: molecular strategies in neutralophilic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:1091–1125. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krulwich TA, Sachs G, Padan E. 2011. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:330–343. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hu W, Feng S, Tong Y, Zhang H, Yang H. 2020. Adaptive defensive mechanism of bioleaching microorganisms under extremely environmental acid stress: advances and perspectives. Biotechnol Adv 42:107580. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yin W, Wang Y, Liu L, He J. 2019. Biofilms: the microbial “protective clothing” in extreme environments. Int J Mol Sci 20:3423. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller-Fleming L, Olin-Sandoval V, Campbell K, Ralser M. 2015. Remaining mysteries of molecular biology: the role of polyamines in the cell. J Mol Biol 427:3389–3406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. González-Hernández AI, Scalschi L, Vicedo B, Marcos-Barbero EL, Morcuende R, Camañes G. 2022. Putrescine: a key metabolite involved in plant development, tolerance and resistance responses to stress. Int J Mol Sci 23:2971. doi: 10.3390/ijms23062971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu Z, Hossain SS, Morales Moreira Z, Haney CH. 2022. Putrescine and its metabolic precursor arginine promote biofilm and c-di-GMP synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 204:e0029721. doi: 10.1128/JB.00297-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Kim SH, Natarajan R, Heindl JE, Bruger EL, Waters CM, Michael AJ, Fuqua C. 2016. Spermidine inversely influences surface interactions and planktonic growth in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol 198:2682–2691. doi: 10.1128/JB.00265-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramón-Peréz ML, Díaz-Cedillo F, Contreras-Rodríguez A, Betanzos-Cabrera G, Peralta H, Rodríguez-Martínez S, Cancino-Diaz ME, Jan-Roblero J, Cancino Diaz JC. 2015. Different sensitivity levels to norspermidine on biofilm formation in clinical and commensal staphylococcus epidermidis strains. Microb Pathog 79:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chubukov V, Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Sauer U. 2014. Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu M, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Dong L, Liu C, Chen Y. 2022. Propionibacterium freudenreichii -assisted approach reduces N 2 O emission and improves denitrification via promoting substrate uptake and metabolism. Environ Sci Technol 56:16895–16906. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c05674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo Y, Li D, Liao H, Xia X. 2023. Patterns of biogenic amine during broad bean paste fermentation: microbial diversity and functionality via bacillus bioaugmentation. J Sci Food Agric 103:1315–1325. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang Y-C, Wang C, Han M-F, Tong Z, Lin Y-T, Hu X-R, Deng J-G, Hsi H-C. 2022. Inhibiting effect of quorum quenching on biomass accumulation: a clogging control strategy in gas biofilters. Chem Eng J 432:134313. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.134313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Y-C, Lin Y-T, Wang C, Tong Z, Hu X-R, Lv Y-H, Jiang G-Y, Han M-F, Deng J-G, Hsi H-C, Lee C-H. 2022. Microbial community regulation and performance enhancement in gas biofilters by interrupting bacterial communication. Microbiome 10:150. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01345-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Merritt JH, Kadouri DE, O’Toole GA. 2005. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr Protoc Microbiol Chapter 1:1. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang C, Zhao X, Wang C, Hakizimana I, Crittenden JC, Laghari AAli. 2022. Electrochemical flow-through disinfection reduces antibiotic resistance genes and horizontal transfer risk across bacterial species. Water Res 212:118090. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Y-C, Wang C, Han M-F, Tong Z, Hu X-R, Lin Y-T, Zhao X. 2022. Reduction of biofilm adhesion strength by adjusting the characteristics of biofilms through enzymatic quorum quenching. Chemosphere 288:132465. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Theiss C, Bohley P, Bisswanger H, Voigt J. 2004. Uptake of polyamines by the unicellular green alga chlamydomonas reinhardtii and their effect on ornithine decarboxylase activity. J Plant Physiol 161:3–14. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet j 17:10. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brum JR, Ignacio-Espinoza JC, Roux S, Doulcier G, Acinas SG, Alberti A, Chaffron S, Cruaud C, de Vargas C, Gasol JM, et al. 2015. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities. Science 348:1261498. doi: 10.1126/science.1261498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lawton SA, Anthony C. 1985. The role of blue copper proteins in the oxidation of methylamine by an obligate methylotroph. Biochem J 228:719–726. doi: 10.1042/bj2280719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen M, Cai Y, Li G, Zhao H, An T. 2022. The stress response mechanisms of biofilm formation under sub-lethal photocatalysis. Appl Catal B Environ 307:121200. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Penesyan A, Paulsen IT, Kjelleberg S, Gillings MR. 2021. Three faces of biofilms: a microbial lifestyle, a nascent multicellular organism, and an incubator for diversity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7:80. doi: 10.1038/s41522-021-00251-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miwa T, Takimoto Y, Hatamoto M, Kuratate D, Watari T, Yamaguchi T. 2021. Role of live cell colonization in the biofilm formation process in membrane bioreactors treating actual sewage under low organic loading rate conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105:1721–1729. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11119-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guzmán-Soto I, McTiernan C, Gonzalez-Gomez M, Ross A, Gupta K, Suuronen EJ, Mah T-F, Griffith M, Alarcon EI. 2021. Mimicking biofilm formation and development: recent progress in in vitro and in vivo biofilm models. iScience 24:102443. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yan Y, Tang J, Yuan Q, Liu H, Huang J, Hsiang T, Bao C, Zheng L. 2022. Ornithine decarboxylase of the fungal pathogen colletotrichum higginsianum plays an important role in regulating global metabolic pathways and virulence. Environ Microbiol 24:1093–1116. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Foster A, Barnes N, Speight R, Keane MA. 2013. Genomic organisation, activity and distribution analysis of the microbial putrescine oxidase degradation pathway. Syst Appl Microbiol 36:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xu J, Zhao N, Meng X, Zhang T, Li J, Dong H, Wei X, Fan M. 2023. Contribution of amino acids to alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris DSM 3922t resistance towards acid stress. Food Microbiol 113:104273. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2023.104273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dean RT, Jessup W, Roberts CR. 1984. Effects of exogenous amines on mammalian cells, with particular reference to membrane flow. Biochem J 217:27–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2170027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhong M, Yuan Y, Shu S, Sun J, Guo S, Yuan R, Tang Y. 2016. Effects of exogenous putrescine on glycolysis and krebs cycle metabolism in cucumber leaves subjected to salt stress. Plant Growth Regul 79:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10725-015-0136-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li W-M, Liao X-W, Guo J-S, Zhang Y-X, Chen Y-P, Fang F, Yan P. 2020. New insights into filamentous sludge bulking: the potential role of extracellular polymeric substances in sludge bulking in the activated sludge process. Chemosphere 248:126012. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. More TT, Yadav JSS, Yan S, Tyagi RD, Surampalli RY. 2014. Extracellular polymeric substances of bacteria and their potential environmental applications. J Environ Manage 144:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Poli A, Anzelmo G, Nicolaus B. 2010. Bacterial exopolysaccharides from extreme marine habitats: production, characterization and biological activities. Mar Drugs 8:1779–1802. doi: 10.3390/md8061779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. De Robertis A, De Stefano C, Gianguzza A, Sammartano S. 1998. Binding of polyanions by biogenic amines. I. Formation and stability of protonated putrescine and cadaverine complexes with inorganic anions. Talanta 46:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(97)00388-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lin D, Story SD, Walker SL, Huang Q, Liang W, Cai P. 2017. Role of pH and ionic strength in the aggregation of TiO2 nanoparticles in the presence of extracellular polymeric substances from Bacillus subtilis. Environ Pollut 228:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Biglione C, Neumann‐Tran TMP, Kanwal S, Klinger D. 2021. Amphiphilic micro- and nanogels: combining properties from internal hydrogel networks, solid particles, and micellar aggregates. J Polym Sci 59:2665–2703. doi: 10.1002/pol.20210508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hamill OP, Martinac B. 2001. Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol Rev 81:685–740. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. García-Caparrós P, De Filippis L, Gul A, Hasanuzzaman M, Ozturk M, Altay V, Lao MT. 2021. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: a review. Bot Rev 87:421–466. doi: 10.1007/s12229-020-09231-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Naufal M, Wu J-H, Shao Y-H. 2022. Glutamate enhances osmoadaptation of anammox bacteria under high salinity: genomic analysis and experimental evidence. Environ Sci Technol 56:11310–11322. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c01104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dhakar K, Pandey A. 2016. Wide pH range tolerance in extremophiles: towards understanding an important phenomenon for future biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:2499–2510. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7285-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jorge JMP, Leggewie C, Wendisch VF. 2016. A new metabolic route for the production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Corynebacterium glutamicum from glucose. Amino Acids 48:2519–2531. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2272-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gu X, Zhang R, Zhao J, Li C, Guo T, Yang S, Han T, Kong J. 2022. Fast-acidification promotes GABA synthesis in response to acid stress in streptococcus thermophilus. LWT 164:113671. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lin Q, Wang H, Huang J, Liu Z, Chen Q, Yu G, Xu Z, Cheng P, Liang Z, Zhang L-H. 2022. Spermidine is an Intercellular signal modulating T3SS expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0064422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00644-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ma Z, Richard H, Foster JW. 2003. pH-dependent modulation of cyclic AMP levels and GadW-dependent repression of RpoS affect synthesis of the GadX regulator and Escherichia coli acid resistance. J Bacteriol 185:6852–6859. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.23.6852-6859.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Walls AB, Waagepetersen HS, Bak LK, Schousboe A, Sonnewald U. 2015. The glutamine–glutamate/GABA cycle: function, regional differences in glutamate and GABA production and effects of interference with GABA metabolism. Neurochem Res 40:402–409. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1473-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bergkessel M, Basta DW, Newman DK. 2016. The physiology of growth arrest: uniting molecular and environmental microbiology. 9. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:549–562. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Küster U, Bohnensack R, Kunz W. 1976. Control of oxidative phosphorylation by the extramitochondrial ATP/ADP ratio. Biochim Biophys Acta 440:391–402. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(76)90073-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pottosin I, Olivas-Aguirre M, Dobrovinskaya O, Zepeda-Jazo I, Shabala S. 2020. Modulation of ion transport across plant membranes by polyamines: understanding specific modes of action under stress. Front Plant Sci 11:616077. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.616077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ioannidis NE, Sfichi L, Kotzabasis K. 2006. Putrescine stimulates chemiosmotic ATP synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757:821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu X, Shu S, Wang Y, Yuan R, Guo S. 2019. Exogenous putrescine alleviates photoinhibition caused by salt stress through cooperation with cyclic electron flow in cucumber. Photosynth Res 141:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s11120-019-00631-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu KY, Zweier JL, Becker LC. 1997. Hydroxyl radical inhibits sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase function by direct attack on the ATP binding site. Circ Res 80:76–81. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pérez-Rodríguez F, Valdés-Santiago L, García-Chávez JN, Castro-Guillén JL, Ruiz-Herrera J. 2023. Analysis of gene expression related to polyamine concentration and dimorphism induced in ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and spermidine synthase (SPD) ustilago maydis mutants. Fungal Genet Biol 166:103792. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2023.103792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li Z, Liu J-Z. 2017. Transcriptomic changes in response to putrescine production in metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum Front Microbiol 8:1987. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rutherford BJ, Dahl RH, Price RE, Szmidt HL, Benke PI, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD. 2010. Functional genomic study of exogenous N-butanol stress in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:1935–1945. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02323-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Han T-L, Cannon RD, Gallo SM, Villas-Bôas SG. 2019. A metabolomic study of the effect of Candida albicans glutamate dehydrogenase deletion on growth and morphogenesis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 5:13. doi: 10.1038/s41522-019-0086-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nissim I. 1999. Newer aspects of glutamine/glutamate metabolism: the role of acute pH changes. Am J Physiol-Ren Physiol 277:F493–F497. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.4.F493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. O’Sullivan E, Condon S. 1999. Relationship between acid tolerance, cytoplasmic pH, and ATP and H+-ATPase levels in chemostat cultures of lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:2287–2293. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.6.2287-2293.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schlegel K, Leone V, Faraldo-Gómez JD, Müller V. 2012. Promiscuous archaeal ATP synthase concurrently coupled to Na+ and H+ translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:947–952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115796109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Segal-Kischinevzky C, Romero-Aguilar L, Alcaraz LD, López-Ortiz G, Martínez-Castillo B, Torres-Ramírez N, Sandoval G, González J. 2022. Yeasts inhabiting extreme environments and their biotechnological applications. Microorganisms 10:794. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Michael AP, Grace EJ, Kotiw M, Barrow RA. 2003. Isochromophilone IX, a novel GABA-containing metabolite isolated from a cultured fungus, Penicillium sp. Aust J Chem 56:13. doi: 10.1071/CH02021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nižnanský Ľ, Varečka Ľ, Kryštofová S. 2016. Disruption of GABA shunt affects response to nutritional and environmental stimuli. Acta Chim Slovaca 9:109–113. doi: 10.1515/acs-2016-0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang Q, Chen D, Wu M, Zhu J, Jiang C, Xu J-R, Liu H. 2018. MFS transporters and GABA metabolism are involved in the self-defense against DON in fusarium graminearum. Front Plant Sci 9:438. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sánchez-Andrea I, van der Graaf CM, Hornung B, Bale NJ, Jarzembowska M, Sousa DZ, Rijpstra WIC, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Stams AJM. 2022. Acetate degradation at low pH by the moderately acidophilic sulfate reducer acididesulfobacillus acetoxydans gen. nov. sp. nov. Front Microbiol 13:816605. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.816605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kanekar PP, Kanekar SP. 2022. Alkaliphilic, alkalitolerant microorganisms, p 71–116. In Kanekar PP, Kanekar SP (ed), Diversity and biotechnology of extremophilic microorganisms from India. Springer Nature, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lee J, Mahandra H, Hein GA, Ramsay J, Ghahreman A. 2021. Toward sustainable solution for biooxidation of waste and refractory materials using neutrophilic and alkaliphilic microorganisms—A review. ACS Appl Bio Mater 4:2274–2292. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c01582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Inaba T, Hori T, Aizawa H, Ogata A, Habe H. 2017. Architecture, component, and microbiome of biofilm involved in the fouling of membrane bioreactors. 1. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 3:5. doi: 10.1038/s41522-016-0010-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jia T, Zhang L, Sun S, Zhao Q, Peng Y. 2023. Adding organics to enrich mixotrophic sulfur-oxidizing bacteria under extremely acidic conditions—a novel strategy to enhance hydrogen sulfide removal. Sci Total Environ 854:158768. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Teo CW, Wong PCY. 2014. Enzyme augmentation of an anaerobic membrane bioreactor treating sewage containing organic particulates. Water Res 48:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Iversen V, Koseoglu H, Yigit NO, Drews A, Kitis M, Lesjean B, Kraume M. 2009. Impacts of membrane flux enhancers on activated sludge respiration and nutrient removal in MBRs. Water Res 43:822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mpongwana N, Rathilal S. 2022. Exploiting biofilm characteristics to enhance biological nutrient removal in wastewater treatment plants. Appl Sci 12:7561. doi: 10.3390/app12157561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sakanaka A, Kuboniwa M, Shimma S, Alghamdi SA, Mayumi S, Lamont RJ, Fukusaki E, Amano A. 2022. Fusobacterium nucleatum metabolically integrates commensals and pathogens in oral biofilms. mSystems 7:e0017022. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00170-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Text S1 to S10, Fig. S1 to S8, and Table S1.

Data Availability Statement

The raw reads can be obtained in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank (accession number PRJNA992974).