ABSTRACT

Tattooing and use of permanent makeup (PMU) have dramatically increased over the last decade, with a concomitant increase in ink-related infections. Studies have shown evidence that commercial tattoo and PMU inks are frequently contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms. Considering that tattoo inks are placed into the dermal layer of the skin where anaerobic bacteria can thrive and cause infections in low-oxygen environments, the prevalence of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria should be assessed in tattoo and PMU inks. In this study, we tested 75 tattoo and PMU inks using the analytical methods described in the FDA Bacteriological Analytical Manual Chapter 23 for the detection of both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial contamination, followed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing for microbial identification. Of 75 ink samples, we found 26 contaminated samples with 34 bacterial isolates taxonomically classified into 14 genera and 22 species. Among the 34 bacterial isolates, 19 were identified as possibly pathogenic bacterial strains. Two species, namely Cutibacterium acnes (four strains) and Staphylococcus epidermidis (two strains) were isolated under anaerobic conditions. Two possibly pathogenic bacterial strains, Staphylococcus saprophyticus and C. acnes, were isolated together from the same ink samples (n = 2), indicating that tattoo and PMU inks can contain both aerobic (S. saprophyticus) and anaerobic bacteria (C. acnes). No significant association was found between sterility claims on the ink label and the absence of bacterial contamination. The results indicate that tattoo and PMU inks can also contain anaerobic bacteria.

IMPORTANCE

The rising popularity of tattooing and permanent makeup (PMU) has led to increased reports of ink-related infections. This study is the first to investigate the presence of both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in commercial tattoo and PMU inks under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Our findings reveal that unopened and sealed tattoo inks can harbor anaerobic bacteria, known to thrive in low-oxygen environments, such as the dermal layer of the skin, alongside aerobic bacteria. This suggests that contaminated tattoo inks could be a source of infection from both types of bacteria. The results emphasize the importance of monitoring these products for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including possibly pathogenic microorganisms.

KEYWORDS: tattoo ink, permanent makeup ink, microbial contamination, anaerobic bacteria, aerobic bacteria

INTRODUCTION

Tattooing, along with the use of permanent makeup (PMU), has dramatically increased over the last two decades (1). Approximately 32% of the population in the United States is estimated to have at least one tattoo (https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/08/15/32-of-americans-have-a-tattoo-including-22-who-have-more-than-one). As tattooing has become increasingly common, tattoo-related human health risks and adverse events have also increased (2–4). Although the most common types of tattoo-associated human complications are often known to be immunologic reactions, including inflammatory reactions and allergic hypersensitivity (5, 6), infectious complications have also been commonly associated with tattoos (5, 7, 8).

Studies showed that approximately 0.5%–6% of tattooed people experienced microbial infectious complications as a result of receiving a tattoo (7, 9, 10). Previously, the sources of infection were mainly associated with issues related to insufficient hygiene practices at the time of tattoo application as well as lack of proper aftercare while healing (7, 9, 10). However, recent findings suggest that tattoo inks themselves have been identified as a potential source of infections (5, 8, 11).

Infectious complications from tattoos can range from mild skin infections to systemic infections, such as life-threatening bacteremia and septic shock (7). Tattooing, which breaches the skin barrier during application, can increase the risk of infection transmission if the tattoo inks used are contaminated with pathogenic bacteria that are embedded deep into the skin throughout the procedure. The low-oxygen environment of the dermal layer of the skin further allows a possibility of infection by anaerobic bacteria. Studies have shown infections related to tattoos caused by anaerobic microorganisms, such as Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus (12, 13).

In our prior studies, we showed that overall, 68 of 197 (35%) unopened and sealed tattoo and PMU inks and diluents from 17 of 26 manufacturers in the U.S. were contaminated with microorganisms (14–16). Some of these products had total bacterial counts as high as 108 CFU/g of ink, despite being labeled as sterile (14–16). These results were in line with previous studies reported in multiple European countries, where as much as 80% of tattoo inks were shown to be contaminated with microorganisms, including pathogenic bacteria (17–20). Considering the high portion of tattoo inks contaminated with a variety of bacteria, it is reasonable to question whether tattoo inks are also contaminated with anaerobic bacteria. Currently, little is known about the contamination of tattoo inks with anaerobic bacteria. In this study, we assessed the prevalence of anaerobic and aerobic microbial contaminants in 75 tattoo and PMU inks available on the U.S. market.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and storage of tattoo and PMU inks

A total of 75 tattoo and PMU inks were purchased from 14 tattoo ink manufacturers (Table 1). Six bottles of each individual ink, having the same lot number, were purchased. All ink samples were confirmed to be intact with sealed packaging and were photographed, stored in the storage cabinets, and recorded on the chain-of-custody log. The information from the samples, such as brand and product (color) name, safety data sheets, ingredients, sterility claims, expiration dates, and locations of the manufacturer, was recorded.

TABLE 1.

Summary of ink samples used in this study

| Tattoo ink | PMUa ink | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of samples | 40 | 35 | 75 |

| No. of brands | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Sterility claim | |||

| Yes | 35 | 14 | 49 |

| NAb | 5 | 21 | 26 |

| Country of origin | |||

| Domestic (USA) | 40 | 13 | 53 |

| Imported | 0 | 22 | 22 |

PMU, permanent makeup.

NA, sterility information not available.

Bacteriological analysis of tattoo and PMU ink samples

The prevalence of anaerobes (including facultative anaerobes) and aerobes were analyzed based on the methods of the FDA Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM) Chapter 23 (https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-methods-cosmetics). Briefly, pre-reduced Anaerobe Agar (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS, USA), 5% defibrinated sheep Blood Agar (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS, USA), and Modified Letheen Agar (MLA, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS, USA) were used as growth media. Sample dilution and plating were performed as described for aerobic plate counts. Briefly, samples were decimally diluted in MLB from 10−1 to 10−3. Using a new sterile pipet to transfer, 1.0 mL of the current dilution was transferred into 9 mL of fresh MLB to make the next decimal dilution. Dilutions were mixed thoroughly, and all plating was performed in duplicate. An aliquot of 1 mL of 10−1 dilution (0.5 mL on each of the two plates) was plated on MLA, Blood Agar, and Anaerobe Agar to yield a final dilution of 10−1. In addition, from each diluted (10−1 to 10−3) solution, 0.1 mL was transferred onto MLA, Blood Agar, and Anaerobe Agar plates to yield final dilutions 10−2 to 10−4. Anaerobe Agar plates were incubated in anaerobic chamber AS-580 (Anaerobe systems, Morgan Hill, CA, USA), and Blood Agar plates were incubated in a 5% carbon dioxide microaerophilic atmosphere. The plates were incubated for 48 h before counting and continuously incubated for 2 more days if no colonies appeared at 48 h. Anaerobic Agar plates were pre-reduced in an anaerobic atmosphere overnight before plating experiments. Inoculated Anaerobe Agar plates were initially incubated in an anaerobic atmosphere for 2 days at 35±2°C, then the plates were incubated for up to 10 days for the detection of slow-growing bacteria. MLA plates were aerobically incubated for 2 days at 35±2°C. Isolates recovered from the anaerobic agar plates were sub-cultured under both microaerophilic conditions with 5% CO2 and anaerobic conditions to confirm their strict anaerobic nature. Positive controls with bacterial species, Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Bacillus cereus (ATCC 11778), and Clostridium sporogenes (ATCC 3584), were used for aerobic and anaerobic conditions, respectively. Negative controls without bacterial cultures (air plates) were used with each medium and anaerobic and aerobic conditions.

Identification of bacterial isolates

The taxonomy of the colonies from agar plates was identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing as previously described (21). Briefly, a colony was used for the PCR amplification with the 16S rRNA gene primers 27F and 1492R. The amplified PCR product was purified with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) as suggested by the manufacturer. DNA samples were sequenced at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, AR (https://medicine.uams.edu/mbim/research-cores/dna-sequencing-core-facility/). The DNA sequences of 16S rRNA genes were analyzed for the identification of bacterial species using NCBI BLASTN and the rRNA/ITS database.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

The analysis of the co-occurrence network was performed as previously described (15, 16, 22). Briefly, using in-house Python scripts, a species-sample matrix (SSM) was generated. Next, a co-occurrence matrix was generated from the SSM. The co-occurrence relationship was presented when two bacterial species were identified from one tattoo and PMU sample. In a species-centric co-occurrence network (SCN), the bacterial species were presented as nodes and their relationships between bacterial species were presented as edges (i.e., connection degree) weighted by their occurrence counts and frequency of co-occurrence. Network analysis and visualization were performed using Gephi 0.9.2 (https://gephi.org/).

The chi-square test and Fisher exact test were used to explore the statistical significance of the relationship between two categorical variables in this study. In all tests of significance, P < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant relationship between the two variables. The basic format for reporting a chi-square test result was used: χ2 (degrees of freedom, N = sample size) = χ2 statistic value, P = P value.

RESULTS

Bacterial isolation

Of the 75 ink samples, 34 bacterial isolates were recovered from 26 ink samples. As shown in Table 2, the 34 bacterial isolates were clustered into three groups based on their growth patterns under the three different growth conditions (i.e., no oxygen, low oxygen, and atmospheric oxygen). Group 1, consisting of obligate anaerobes (i.e., bacteria growing only on oxygen-free anaerobic agar in the anaerobic chamber) contained six isolates. Group 2 has seven isolates showing a common growth pattern of some facultative anaerobes and aerobes. By contrast, Group 3, with a typical growth pattern of obligate aerobic bacteria (i.e., growing only on aerobic medium MLA), contained 21 isolates.

TABLE 2.

Classification of 34 bacterial isolates from 26 ink samples based on their growth under three different conditions (growth media and oxygen levels)

| Group | Bacterial growth based on medium and growth conditiona | No. of isolatesb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobe agar (no oxygen) | Blood agar (low oxygen) | MLA (atmospheric oxygen) |

||

| 1 | + | – | – | 6 |

| 2 | – | + | + | 7 (1) |

| 3 | – | – | + | 21 (15) |

MLA, modified letheen agar; +, bacterial growth; –, no bacterial growth.

Number in parentheses indicates growth observed after broth enrichment step.

Bacterial identification

The 34 bacterial isolates were taxonomically identified using their 16S rRNA gene sequences. They belonged to a phylogenetically diverse group of 14 genera and 22 species (Tables 3 and 4). The six isolates showing anaerobic growth patterns (Group 1) were the obligate anaerobic Cutibacterium acnes (four isolates) and the facultative anaerobic Staphylococcus epidermidis (two isolates). None of the six isolates grew in MLA agar in aerobic conditions (Table 3). By contrast, the isolates of both Group 2 and 3 were identified as aerobes based on oxygen requirement though the seven isolates, such as Pseudomonas putida, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, were isolated in the facultative anaerobic and aerobic culture conditions (Tables 3 and 4). The 16S rRNA gene sequence-based taxonomical identification of the isolates agrees with their phenotypic growth patterns.

TABLE 3.

Identification and phenotypic features of 34 bacterial isolates

| Group | Identification | No. of strains | Oxygen requirementa | Potential pathogenicityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cutibacterium acnes | 4 | Anaerobe | + |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2 | Facultative anaerobe | + | |

| 2 | Pseudomonas putida | 1 | Aerobe | + |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 3 | Facultative anaerobe | + | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 | Aerobe | + | |

| Streptomyces thermoviolaceus | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| 3 | Bacillus aerius | 1 | Aerobe | – |

| Bacillus firmus | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Bacillus siralis | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Brevibacillus agri | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Chryseobacterium nepalense | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Dermacoccus nishinomiyaensis | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Massilia sp. | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Micrococcus luteus | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Nocardiopsis dassonvillei | 2 | Aerobe | + | |

| Pseudomonas putida | 1 | Aerobe | + | |

| Sphingomonas olei | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Sphingomonas spp. | 2 | Aerobe | – | |

| Sphingomonas yanoikuyae | 1 | Aerobe | – | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 1 | Facultative anaerobe | + | |

| Staphylococcus warneri | 1 | Aerobe | + | |

| Staphylococcus xylosus | 1 | Aerobe | + | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1 | Aerobe | + | |

| Streptomyces virginiae | 1 | Aerobe | – |

The oxygen requirements of the isolates in this study were determined based on the oxygen requirements of known reference species. The oxygen requirements of three bacterial isolates belonging to genera Massilia and Sphingomonas, but not assigned to a specific species, are based on their respective genera.

+, potential pathogen; -, no potential pathogen. The potential pathogenicity of the isolates was derived from reference species known to be pathogenic within their respective genera (23, 24). The potential pathogenicity of three bacterial isolates belonging to the genera Massilia and Sphingomonas, but not assigned to a specific species, is based on their respective genera.

TABLE 4.

Detection and identification of bacteria in tattoo or PMU inksa

| Ink # |

Mfr | Sample # | Country of origin | Ink type | Sterility claimb | CFU/g | Bacterial identification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic | CO2 (5%) | Aerobic | |||||||

| 1 | A | A-01 | Germany | PMU | Y | <250 | – | – | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| 2 | A-02 | PMU | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 3 | A-03 | PMU | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 4 | B | B-01 | USA | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |

| 5 | B-02 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 6 | B-03 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 7 | B-04 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 8 | B-05 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 9 | C | C-01 | France | PMU | Y | – | – | 5.0 × 103 | Pseudomonas putida |

| – | 2.5 × 10d | –e | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | ||||||

| 10 | C-02 | PMU | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 11 | C-03 | PMU | Y | – | – | –e | Bacillus aerius | ||

| 12 | C-04 | PMU | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 13 | C-05 | PMU | Y | – | <250 | <250 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | ||

| <250c | – | – | Cutibacterium acnes | ||||||

| 14 | C-06 | PMU | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 15 | C-07 | PMU | Y | – | 2.5 × 10d | 2.5 × 103 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus | ||

| <250c | – | – | Cutibacterium acnes | ||||||

| 16 | C-08 | PMU | Y | – | – | –e | Staphylococcus xylosus | ||

| 17 | D | D-01 | China | PMU | NA | – | – | –e | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia |

| 18 | D-02 | PMU | NA | <250c | – | – | Cutibacterium acnes | ||

| – | – | 2.5 × 103 | Sphingomonas yanoikuyae | ||||||

| 19 | D-03 | PMU | NA | – | – | 3.0 × 103 | Sphingomonas olei | ||

| – | – | –e | Chryseobacterium nepalense | ||||||

| 20 | D-04 | PMU | NA | – | – | –e | Sphingomonas spp. | ||

| – | – | –e | Massilia spp. | ||||||

| 21 | D-05 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 22 | D-06 | PMU | NA | – | – | –e | Sphingomonas spp. | ||

| – | <250 | –e | Pseudomonas putida | ||||||

| 23 | E | E-01 | China | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |

| 24 | E-02 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 25 | E-03 | PMU | NA | – | 2.5 × 105d | 2.5 × 105d | Streptomyces thermoviolaceus | ||

| 26 | E-04 | PMU | NA | <250c | – | – | Cutibacterium acnes | ||

| 27 | E-05 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 28 | F | F-01 | USA | PMU | Y | – | – | – | |

| 29 | F-02 | PMU | Y | – | – | –e | Streptomyces virginiae | ||

| 30 | F-03 | PMU | Y | – | – | <250 | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei | ||

| 31 | G | G-01 | USA | Tattoo | NA | – | – | – | |

| 32 | G-02 | Tattoo | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 33 | G-03 | Tattoo | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 34 | G-04 | Tattoo | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 35 | G-05 | Tattoo | NA | – | – | –e | Staphylococcus warneri | ||

| 36 | H | H-01 | USA | Tattoo | Y | – | – | –e | Staphylococcus saprophyticus |

| 37 | –e | –e | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ||||||

| H-02 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | ||||

| 38 | H-03 | Tattoo | Y | – | 800 | 800 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | ||

| 39 | H-04 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 40 | H-05 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 41 | I | I-01 | USA | PMU | NA | – | – | –e | Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum |

| 42 | I-02 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 43 | I-03 | PMU | NA | <250 | – | – | Staphylococcus epidermidis | ||

| 44 | I-04 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 45 | I-05 | PMU | NA | – | – | – | |||

| 46 | J | J-01 | USA | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |

| 47 | J-02 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 48 | J-03 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 49 | J-04 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 50 | K | K-01 | USA | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |

| 51 | K-02 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 52 | K-03 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | –e | Brevibacillus agri | ||

| 53 | K-04 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 54 | K-05 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 55 | K-06 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 56 | K-07 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 57 | K-08 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 58 | K-09 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 59 | K-10 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 60 | K-11 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 61 | K-2 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 62 | L | L-01 | USA | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |

| 63 | L-02 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 64 | M | M-01 | USA | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |

| 65 | M-02 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 66 | N | N-01 | USA | Tattoo | Y | – | – | <250 | Micrococcus luteus |

| 67 | N-02 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | 4.5×104 | Pseudomonas putida | ||

| 68 | N-03 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 69 | N-04 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | <250 | Bacillus firmus | ||

| 70 | N-05 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 71 | N-06 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | 1.2 × 103 | Dermacoccus nishinomiyaensis | ||

| 72 | N-07 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 73 | N-08 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

| 74 | N-09 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | –e | Bacillus siralis | ||

| 75 | N-10 | Tattoo | Y | – | – | – | |||

PMU, permanent makeup; Mfr, manufacturer; CFU, colony-forming unit.

Y, sterility claimed in labeling; NA, sterility information not available.

Growth was observed after extended time of incubation (7 to 14 days).

Growth was observed from 1:1,000 dilution.

Growth was observed after broth enrichment step.

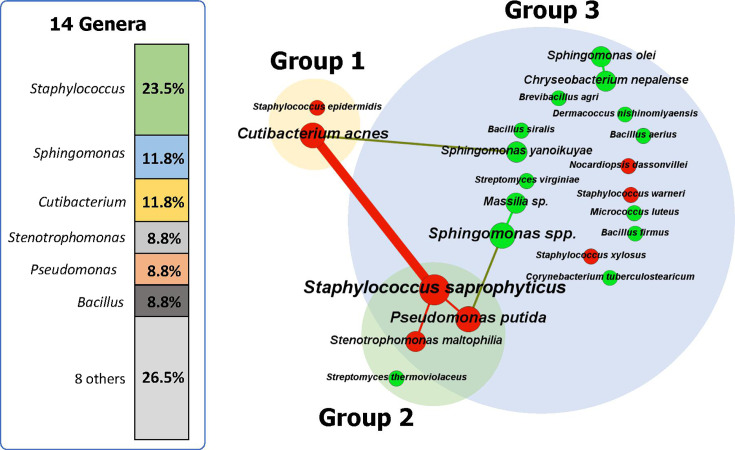

Overall, Staphylococcus spp. (eight isolates) were the most prevalent taxa identified in the samples, followed by C. acnes (four isolates), Sphingomonas spp. (four isolates), Bacillus spp. (three isolates), P. putida (three isolates), S. maltophilia (three isolates), and Streptomyces spp. (two isolates) (Fig. 1). Among the 22 bacterial species, eight species are possibly pathogenic (Tables 3 and 4 and Fig. 1). They included strains of S. saprophyticus, Staphylococcus xylosus, S. epidermidis, Staphylococcus warneri, C. acnes, S. maltophilia, Nocardiopsis dassonvillei, and P. putida (25–32).

Fig 1.

A species-centric co-occurrence network (SCN) of 34 isolates from 26 contaminated ink samples. In the SCN, the bacterial species are presented as nodes, and their co-occurrence relationships were presented as edges (i.e., connection degree). Node size and edge width were weighted by their occurrence counts and frequency of co-occurrence, respectively. The possibly pathogenic species (n=8) and non-pathogenic species (n=14) are colored in red and green, respectively.

Occurrence and co-occurrence of bacterial contaminants

Figure 1 shows an SCN describing the occurrence and co-existence patterns of 34 bacterial isolates at the species level. The 34 bacterial isolates were mapped to produce the SCN with 22 nodes (bacterial species) and seven edges (co-occurrence relationship). Among the 22 bacterial species, two possibly pathogenic bacteria, C. acnes and S. saprophyticus, showed a relatively high occurrence and strong co-occurrence (Fig. 1). In the SCN, S. saprophyticus is a hub species with the highest degree of connection (three connections with three potential pathogenic bacteria, P. putida, S. maltophilia, and C. acnes). The obligate anaerobe, C. acnes (Group 1), showed co-occurrences with both obligate aerobe, Sphingomonas yanoikuyae (Group 3), and facultative anaerobe, S. saprophyticus (Group 2 growing in both aerobic and facultatively anaerobic conditions). Such co-occurrences among the isolates of the three groups indicate that PMU inks can be contaminated with both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria together. The average degree (the average number of edges, or connections, that each node in a network has) of the SCN is 0.63, indicating that most bacterial contaminants have few connections (i.e., the majority of contaminated ink samples exhibited the presence of a bacterial strain).

Bacterial contamination prevalence among tattoo and PMU inks

Overall, 26 of 75 tattoo and PMU inks (35%) from 10 of 14 manufacturers were contaminated (Table 4). Based on the occurrence and co-occurrence of bacterial contaminants with different oxygen dependencies, the 26 contaminated ink samples were categorized into five categories (Table 5). Only one PMU ink sample (E-04) was contaminated by obligate anaerobic C. acnes (category 1). While two PMU ink samples (C-05 and C-07) were contaminated by both obligate anaerobic and facultative anaerobic bacterial strains (category 2), one PMU ink sample (D-02) was contaminated by both obligate anaerobic and aerobic bacterial strains (category 3) (Tables 4 and 5). Two PMU ink samples (A-01 and I-03) were contaminated by facultative anaerobic S. epidermidis (category 4), and the rest (20 ink samples) belong to category 5, contaminated by aerobic bacteria (Tables 4 and 5). All nine contaminated tattoo ink samples fall into category 5, where all bacteria are aerobic.

TABLE 5.

Classification of the 26 contaminated ink samples based on the ability to recover bacterial isolates under different oxygen concentrationsa

| Sample category | Anaerobe | Facultative anaerobe | Aerobe | No. of inks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tattoo ink | PMUb ink | ||||

| 1 | + | – | – | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | + | + | – | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | + | – | + | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | – | + | – | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | – | – | + | 9 | 11 |

Please refer to Table 3 for the oxygen requirements of bacterial contaminants in the products, some of which had multiple bacterial contaminants; +, bacterial growth; -, no bacterial growth.

PMU, permanent makeup.

All contaminated ink samples showed <250 CFU/g, except for eight ink samples, including five PMU inks (C-01, C-07, D-02, D-03, and E-03) and three tattoo inks (H-03, N-02, and N-06), which showed >800 CFU/g (Table 4). An obligate anaerobic C. acnes and a facultative anaerobic S. epidermidis showed <250 CFU/g in the PMU ink samples. By contrast, the facultative anaerobic S. saprophyticus and aerobic S. yanoikuyae in the PMU ink samples belonging to categories 2 and 3 showed 2.5 × 103 CFU/g (Table 4).

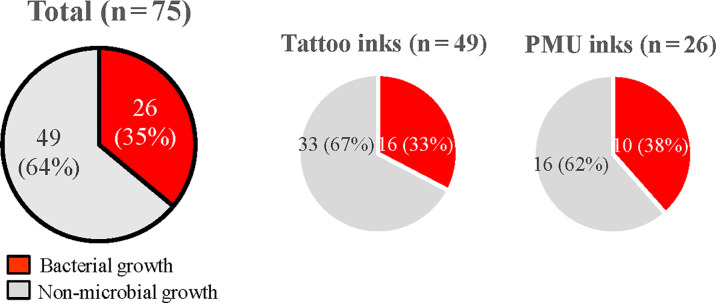

Comparison of microbial contamination of tattoo and PMU inks

PMU inks showed a higher rate of microbial contamination (17 of 35 PMU inks, 49%) than tattoo inks (9 of 40 tattoo inks, 18%) (χ2 [(1, N = 75]) =5.6, P < 0.05)] (Tables 4 and 5 and Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Comparison of the detection of microbial contamination in different tattoo and permanent makeup (PMU) ink samples.

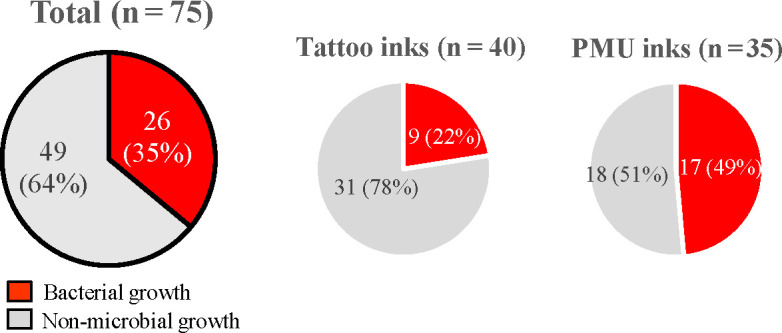

Sterility claims and microbial contamination

Nine manufacturers labeled their ink products (49 inks) as sterile, whereas the other five manufacturer labels did not contain such claims (26 inks, Tables 1 and 4). Among the nine manufacturers with claims of sterility, only products from three manufacturers, J, L, and M, did not have any microbial growth (Table 4). Of 49 inks with sterility claims on the product label, 16 inks (32.7%) contained bacterial contaminants, whereas 10 of 26 inks (38.5%) without sterility claims on the labels were contaminated with bacteria (Fig. 3). No significant association was found between a claim of sterility and absence of bacterial contamination (χ2 [(1, N = 75]) =0.2, P = 0.61)].

Fig 3.

Comparison between inks with and without sterility claims in terms of microbial contamination.

Bacterial contamination of domestic and imported PMU inks

A total of 35 PMU inks (22 imported and 13 domestic inks) were surveyed in this study. Of the imported inks, 13 of 22 (59%) were contaminated with microorganisms compared with 4 of 13 (31%) domestic inks. Among the imported inks, six (from four imported manufacturers) were contaminated with anaerobes, including facultative anaerobes, whereas nine (from three imported manufacturers) were contaminated with aerobes. Conversely, among the domestic inks, one ink was contaminated with anaerobes, and three inks (from two manufacturers) were contaminated with aerobes. However, the difference in microbial contamination between imported and domestic inks was not statistically significant (Fisher exact test, P = 0.72).

DISCUSSION

This is the first microbiological survey of commercial tattoo and PMU inks that examined bacterial contamination under anaerobic conditions. The results of this study showed that unopened and sealed bottles of tattoo and PMU inks were contaminated with anaerobic and aerobic bacteria, indicating that contaminated tattoo inks can be a source of infection not only with aerobic but also anaerobic bacteria. In addition, from a methodological standpoint, this study confirmed that the current BAM Chapter 23 methods can detect anaerobic bacterial contaminants in tattoo and PMU ink products.

Anaerobic plate count for tattoo and PMU inks

The anaerobic plate count (BAM Chapter 23 section H.3) method adopts three different bacterial growth media and conditions to detect anaerobes and aerobes. As shown in this study, the different growth media and conditions led to the successful cultivation of a variety of bacterial contaminants, including some obligate anaerobes, from the tattoo and PMU inks. In addition, the cultivation approach provided another opportunity to compare and verify each cultivation’s results. In this study, six strains capable of obligate anaerobic growth were isolated. The sensitivity of the anaerobically cultured strains to oxygen was tested by inoculation on aerobic agar plates and cultivation under aerobic conditions. None of the six isolates grew on the MLA agar under aerobic conditions. The 16S rRNA gene sequence-based taxonomical identification of the six isolates further supports their phenotypic growth patterns. This study adopted phenotype-based (culture-based) bacterial isolation and genotype-based identification.

In this study, we used the anaerobic plate count methods from BAM Chapter 23 to recover and identify both anaerobes and aerobes. However, these techniques may not efficiently recover endospores and therefore our enumeration and detection may not have accounted for all endospores present in tattoo inks.

Potential inhibition effect of some ingredients

The PMU sample E-03 showed microbiological growth in 1:1,000 dilution but no growth in 1:10 or 1:100 dilution. The isolate was identified as a thermophilic Streptomyces thermoviolaceus. The growth pattern of the bacterial contaminant suggests a possible inhibition effect of the ingredient(s) of the PMU ink sample on microbial growth. In BAM Chapter 23, dilution and plating media that partially inactivate preservative systems commonly found in tattoo inks are utilized to minimize the inhibition of microbial contaminants. Previously, multiple potential antimicrobial ingredients have been identified in the tattoo and PMU ink matrices, including formaldehyde, methanol, denatured alcohols, aldehydes, titanium oxide, carbon, iron oxide, turmeric, copper, cadmium red, and tannins (33–35). We did not analyze or confirm the ingredient composition of the E-03 ink sample, but based on its ingredients list on the label, the PMU ink matrix (ink sample E-03) has propylene glycol (PG), a compound that can have bactericidal activity at certain concentrations.

Anaerobic and aerobic bacterial contamination

The six strains growing under anaerobic culture conditions were identified as an obligate anaerobic bacterium, C. acnes, and a facultative anaerobic bacterium, S. epidermidis (28, 36). To our knowledge, this is the first report regarding the isolation of obligate anaerobic C. acnes from PMU inks (Table 1). Strains of S. epidermidis, known to be a facultative anaerobe, were isolated from an obligate anaerobic condition but not from blood agar plates incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, which is more favorable for facultative anaerobic bacteria (32). By contrast, six strains capable of growing in both facultative and aerobic conditions were identified as aerobes.

C. acnes, S. saprophyticus, and S. epidermidis

C. acnes is a slow-growing anaerobic bacterium responsible for human diseases, such as acne and implant-associated infection (28). C. acnes is also known to contribute to the pathogenesis of staphylococcal skin infection via biofilm formation and break of homeostasis of the skin’s microbiome (28). The co-occurrence of C. acnes and S. saprophyticus was found in a patient with inflammatory cutaneous and osteoarticular conditions (37). In our study, S. saprophyticus showed the highest connection degree to other organisms (i.e., a strong co-occurrence pattern). S. saprophyticus is a Gram-positive, coagulase-negative, non-hemolytic coccus that is a common cause of uncomplicated urinary tract infections, particularly in young sexually active females (38). By contrast, the facultative anaerobic S. epidermidis strains showed no co-occurrence pattern, even with other anaerobic isolates. A systematic analysis of the occurrence and co-occurrence of microbial contaminants could be useful to address fundamental and practical questions (e.g., microbial contamination sources, degree of microbial complexity, and origins of microbial infection) in terms of microbial contamination and the corresponding infectious complications of tattoo and PMU inks (15, 16).

Sterility claims and microbial contamination

Of 49 inks (33%) labeled “sterile,” 16 were still found to be contaminated with microorganisms, a smaller percentage compared with the previous survey (10 of 23 inks, 49%) (14–16). As confirmed in this study, no significant association was found between sterility claims and lack of bacterial contamination. These findings indicated that the actual sterilization process may not be effective to remove all microorganisms, or the label claims may not be accurate. Thus, the effectiveness of the current sterilization methods used in the tattoo ink manufacturing process needs to be evaluated.

Difference in bacterial contamination of tattoo and PMU inks

In this study, PMU inks showed a higher statistically significant percentage of contamination than tattoo inks. All of the tattoo inks surveyed in this study were from manufacturers whose products were previously evaluated by the FDA. By contrast, as revealed in a comparison of the abundance and diversity of the bacterial contaminants, PMU ink samples showed more diverse contamination profiles (14–16). It is worth noting that some PMU inks were imported to the U.S., whereas all tattoo inks were domestically produced. Further work is needed to assess pathogenic bacteria and bioburden, and the effects of microbial contamination on tattoo and PMU inks.

Bacterial contamination of domestic and imported inks

In this study, we have surveyed 75 ink samples from 14 manufacturers, consisting of 10 USA manufacturers and four foreign manufacturers. Although the ink samples of four USA manufacturers showed no microbial contamination, one USA (F) and two foreign manufacturers (C, France, and D, China) had the highest rate of bacterial contamination. Despite all the ink samples from manufacturer C (France) being labeled “sterile,” 5 of 8 samples were contaminated with several bacterial strains, including an anaerobic pathogen, C. acnes, and an aerobic pathogen, S. saprophyticus. The ink samples from the top three manufacturers with the highest bacterial contamination rate were all PMU inks.

In conclusion, the results indicate that commercial tattoo and PMU inks contain both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and highlight the importance of monitoring these products for the occurrence of pathogenic microorganisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Kidon Sung and Miseon Park for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by an appointment to the Postgraduate Research Fellowship Program at the National Center for Toxicological Research, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

This article reflects the views of the authors and does not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Any mention of commercial products is for clarification only and is not intended as approval, endorsement, or recommendation.

Contributor Information

Seong-Jae Kim, Email: seong-jae.kim@fda.hhs.gov.

Ohgew Kweon, Email: oh-gew.kweon@fda.hhs.gov.

Nicole R. Buan, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Kluger N, Seité S, Taieb C. 2019. The prevalence of tattooing and motivations in five major countries over the world. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 33:e484–e486. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, Generali E, Huntley A, Teuber SS, Gershwin ME. 2016. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 50:273–286. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8532-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laux P, Tralau T, Tentschert J, Blume A, Dahouk SA, Bäumler W, Bernstein E, Bocca B, Alimonti A, Colebrook H, et al. 2016. A medical-toxicological view of tattooing. Lancet 387:395–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60215-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, Bäumler W. 2013. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology 226:138–147. doi: 10.1159/000346943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. 2015. Tattoo complaints and complications:diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol 48:48–60. doi: 10.1159/000369645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Serup J, Sepehri M, Hutton Carlsen K. 2016. Classification of tattoo complications in a hospital material of 493 adverse events. Dermatology 232:668–678. doi: 10.1159/000452148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dieckmann R, Boone I, Brockmann SO, Hammerl JA, Kolb-Mäurer A, Goebeler M, Luch A, Al Dahouk S. 2016. The risk of bacterial infection after tattooing. Dtsch Arztebl Int 113:665–671. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LeBlanc PM, Hollinger KA, Klontz KC. 2012. Tattoo ink--related infections-awareness, diagnosis, reporting, and prevention. N Engl J Med 367:985–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1206063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. 2007. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol 25:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, Cavigli A, Lavin BC, Murina A. 2015. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg 41:1283–1289. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ortiz AE, Alster TS. 2012. Rising concern over cosmetic tattoos. Dermatol Surg 38:424–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serup J. 2017. Tattoo infections, personal resistance, and contagious exposure through tattooing. Curr Probl Dermatol 52:30–41. doi: 10.1159/000450777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Serup J. 2017. Medical treatment of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol 52:74–81. doi: 10.1159/000450804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nho SW, Kim SJ, Kweon O, Howard PC, Moon MS, Sadrieh NK, Cerniglia CE. 2018. Microbiological survey of commercial tattoo and permanent makeup inks available in the United States. J Appl Microbiol 124:1294–1302. doi: 10.1111/jam.13713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nho SW, Kim M, Kweon O, Kim S-J, Moon MS, Periz G, Huang M-C, Dewan K, Sadrieh NK, Cerniglia CE. 2020. Microbial contamination of tattoo and permanent makeup inks marketed in the US: a follow-up study. Lett Appl Microbiol 71:351–358. doi: 10.1111/lam.13353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoon S, Kondakala S, Nho SW, Moon MS, Huang MCJ, Periz G, Kweon O, Kim S. 2022. Microbiological survey of 47 permanent makeup inks available in the United States. Microorganisms 10:820. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baumgartner A, Gautsch S. 2011. Hygienic-microbiological quality of tattoo- and permanent make-up colours. J Verbr Lebensm 6:319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00003-010-0636-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bonadonna L. 2015. Survey of studies on microbial contamination of marketed tattoo inks. Curr Probl Dermatol 48:190–195. doi: 10.1159/000369226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Charnock C. 2004. Tattooing dyes and pigments contaminated with bacteria. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 124:933–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Høgsberg T, Saunte DM, Frimodt-Møller N, Serup J. 2013. Microbial status and product labelling of 58 original tattoo inks. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 27:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol 173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kweon O, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Nho SW, Bae D, Chon J, Hart M, Baek DH, Kim YC, Wang W, Kim SK, Sutherland JB, Cerniglia CE. 2020. CYPminer: an automated cytochrome P450 identification, classification, and data analysis tool for genome data sets across kingdoms. BMC Bioinformatics 21:160. doi: 10.1186/s12859-020-3473-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bartlett A, Padfield D, Lear L, Bendall R, Vos M. 2022. A comprehensive list of bacterial pathogens infecting humans. Microbiology (Reading) 168. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Whitman WB, Rainey F, Kämpfer P, Trujillo M. 2015. Bergey's manual of systematics of archaea and bacteria. Vol. 410. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adegoke AA, Stenström TA, Okoh AI. 2017. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as an emerging ubiquitous pathogen: looking beyond contemporary antibiotic therapy. Front Microbiol 8:2276. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Paiva-Santos W, de Sousa VS, Giambiagi-deMarval M. 2018. Occurrence of virulence-associated genes among Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolated from different sources. Microb Pathog 119:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oh WT, Jun JW, Giri SS, Yun S, Kim HJ, Kim SG, Kim SW, Han SJ, Kwon J, Park SC. 2019. Staphylococcus xylosus infection in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) as a primary pathogenic cause of eye protrusion and mortality. Microorganisms 7:330. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel PM, Camps NS, Rivera CI, Gomez I, Tuda CD. 2022. Cutibacterium acnes: an emerging pathogen in culture negative bacterial prosthetic valve infective endocarditis (IE). IDCases 29:e01555. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2022.e01555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scussel R, Lotte R, Gillon J, Chassang M, Boudoumi D, Ruimy R. 2020. Fatal pulmonary infection related to Nocardiopsis dassonvillei in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New Microbes New Infect 35:100654. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Szczuka E, Krzymińska S, Kaznowski A. 2016. Clonality, virulence and the occurrence of genes encoding antibiotic resistance among Staphylococcus warneri isolates from bloodstream infections. J Med Microbiol 65:828–836. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tan G, Xi Y, Yuan P, Sun Z, Yang D. 2019. Risk factors and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Pseudomonas putida infection in central China, 2010-2017. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e17812. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uribe-Alvarez C, Chiquete-Félix N, Contreras-Zentella M, Guerrero-Castillo S, Peña A, Uribe-Carvajal S. 2016. Staphylococcus epidermidis: metabolic adaptation and biofilm formation in response to different oxygen concentrations. Pathog Dis 74:ftv111. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Minghetti P, Musazzi UM, Dorati R, Rocco P. 2019. The safety of tattoo inks: possible options for a common regulatory framework. Sci Total Environ 651:634–637. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schubert S, Dirks M, Dickel H, Lang C, Geier J, IVDK . 2021. Allergens in permanent tattoo ink - first results of the information network of departments of dermatology (IVDK). J Deutsche Derma Gesell 19:1337–1340. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weiß KT, Schreiver I, Siewert K, Luch A, Haslböck B, Berneburg M, Bäumler W. 2021. Tattoos - more than just colored skin? searching for tattoo allergens. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 19:657–669. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Otto M. 2009. “Staphylococcus epidermidis--the 'accidental' pathogen”. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:555–567. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Waters M, Krajden S, Stein J, Elmaraghy A, Eisen A, Aziz Z. 2020. A case of SAPHO syndrome with Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Cutibacterium acnes osteitis. Rheumatol Adv Pract 4:rkz051. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkz051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ehlers S, Merrill SA.. 2022. Staphylococcus saprophyticus Infection, StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]